Abstract

Itinerant antiferromagnets with broken time-reversal symmetry have recently attracted attention, since their spin-split bands enable large magnetotransport responses comparable to ferromagnets despite the negligible spontaneous magnetisation. When the inversion symmetry is further broken by the antiferromagnetic order, the emerging odd-parity multipole order renders the bands spin-degenerate but asymmetric in the momentum space. For such parity-time-symmetric antiferromagnets, it has been predicted that electronic nematicity is induced by current, allowing unconventional nonlinear transport phenomena. However, their experimental evidence has been lacking. Here, we report two-fold nonreciprocal angular magnetoresistance in the tetragonal layered Dirac material SrMnBi2 with parity-time-symmetric antiferromagnetic order in its Mn-Bi layers. By quantitatively modelling the angular and field dependencies using a phenomenological framework, we reveal that the observed nonreciprocal interlayer resistivity arises from the current-induced breaking of four-fold rotoinversion symmetry of the Dirac valleys in the Bi square net adjacent to the Mn-Bi layer. Furthermore, we demonstrate the alignment of parity-time-symmetric antiferromagnetic domains via current-field cooling, achieving electric-magnetic control of the f-wave polarity in momentum space. The observed switchable nonreciprocal transport associated with current-tuneable valley nematicity paves the way for novel antiferromagnetic spintronic and valleytronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

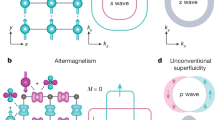

Antiferromagnets have many advantages for spintronic applications1,2, such as resistance to perturbing magnetic fields and the absence of stray fields. For device operation, it is necessary that antiferromagnets exhibit clear magnetotransport responses like ferromagnets (e.g. magnetoresistance and Hall effects), although they do not in principle have spontaneous magnetisation3. Recently, large anomalous Hall and Nernst effects comparable to ferromagnets were discovered in several antiferromagnets in spite of the negligibly small spontaneous magnetisation4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Their electrically switchable properties have garnered significant attention, both for their potential applications and for their relevance to fundamental physics12,13,14. Notable examples include non-collinear magnets hosting cluster multipoles4,5,6,7,8,9, as well as the so-called altermagnets10,11. A defining characteristic of these antiferromagnets is that their time-reversal (\({{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}\)) symmetry is intrinsically broken due to their unique magnetic and crystal structures. This causes spin splitting in the band structure, which is the source of their distinct magnetotransport phenomena.

In those antiferromagnets, the parity (\({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}\)) symmetry associated with the spatial inversion is usually preserved. However, when the \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}\)-symmetry is also broken by the magnetic order, the band structure undergoes significant changes. In such cases, both the \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}\)- and \({{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}\)-symmetries are broken, while the product \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetry is preserved. The impact of \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetry on band structure was initially discussed for insulating magnetoelectric materials, such as Cr2O3, and has recently been extended to metallic magnets15. Based on the electric/magnetic multipole theory, the \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric magnetic order is characterised by the odd-parity magnetic multipole order16,17, resulting in a spin-degenerate band structure that is asymmetric in the momentum space18,19. This unique band structure was theoretically predicted to give rise to various intriguing transport and optical phenomena, including nonlinear electrical conductivity and photocurrent generation20,21,22,23,24,25,26. While a few related experimental observations, such as nonlinear Hall effects27,28,29 and bulk photogalvanic effects30, have been reported, more direct manifestations of the asymmetric band structure have yet to be fully investigated. One such phenomenon is the current-induced shift of asymmetric bands, which breaks the original symmetry and results in nematic distortion of the Fermi surface31. This electronic deformation can generate the lattice deformation via the electron-phonon coupling, which is a magnetic and metallic counterpart of piezoelectricity (called magnetopiezoelectric effect)31,32,33. In fact, it was experimentally observed that a very small change in sample length was caused by current in several \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnets34,35,36. However, intrinsic electronic responses (e.g. transport or optical changes) directly linked to the nematic deformation of the Fermi surface remain experimentally unexplored.

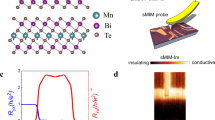

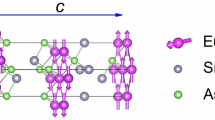

In this study, we have investigated transport phenomena associated with current-induced nematic deformation in the layered \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnet SrMnBi237,38,39. In this material, the local Mn spin surrounded by the Bi tetrahedron exhibits a staggered antiferromagnetic order40. Therefore, the spin-up Mn is located at the centre of the red-coloured Bi tetrahedron, while the spin-down Mn is located at the centre of the blue-coloured Bi tetrahedron (Fig. 1a). This leads to the simultaneous breaking of the \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}\)- and \({{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}\)-symmetries in a nonpolar manner, as the up-spin state in the red tetrahedron and the down-spin state in the blue tetrahedron are not related by either \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}\)- or \({{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}\)-operations (Fig. 1a, c). Although this Mn-Bi layer is a Mott insulator, SrMnBi2 also has a highly-conductive Bi square net layer sandwiched between the Mn-Bi layers, forming quasi-2D (gapped) Dirac bands41,42,43,44. Since a small amount of hole-type carriers are naturally doped, these bands allow the metallic conduction not only in the in-plane direction, but also in the out-of-plane direction by forming coherent cylindrical Fermi surfaces at low temperatures (see the metallic interlayer resistivity below ~150 K in Fig. 1b)45,46. Therefore, SrMnBi2 provides an ideal arena to study the current effects on a \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnet34,36. Furthermore, the Dirac bands in this material possess valley degrees of freedom (see below), enabling unconventional valley symmetry breaking in conjunction with \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnetic order.

a Lattice and magnetic structure of SrMnBi2. b Temperature dependence of interlayer resistivity (ρzz) for a micro-fabricated device of SrMnBi2. c Parity (\({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}\)) violation of antiferromagnetic order of the Mn sublattice. d Four-fold elliptic Dirac valleys at kz = 0. Valley A is elongated along [110], while valley B along \([\overline{1}10]\). e Three-dimensional schematic Fermi surfaces of SrMnBi2 with spin-orbit coupling for Iz = 0 (Iz is current along the z direction) (left) and corresponding cross-sectional cuts for kz > 0 and kz < 0 (right). The asymmetry in kz dispersion is opposite for valleys A and B, preserving the four-fold rotoinversion symmetry of the total Fermi surfaces. f Fermi surfaces for Iz ≠ 0. The current-induced modulation of asymmetric kz dispersion differs for each valley, breaking the original four-fold rotoinversion symmetry across the entire kz-space.

We here concretely explain the asymmetric nature of the quasi-2D Dirac bands in SrMnBi2. On the kz = 0 plane, these bands form exactly four-fold elliptic valleys (Fig. 1d)41,42,43. However, the kz dispersion, namely the warping of the cylindrical Fermi surface, is asymmetric with respect to kz = 0 due to the antisymmetric spin-orbit coupling arising from the odd-parity multipole order in the Mn-Bi layer. First-principles calculations show that the cylindrical Fermi surface in the kz > 0 (kz < 0) regime contracts (expands) for the valley A elongated along [110] direction, while the opposite kz dispersion occurs for the valley B elongated along the \([\overline{1}10]\) direction, as schematically shown in Fig. 1e (For the quantitative kz dispersion, see Fig. S1). As a result, the total Fermi surfaces composed of both valleys preserve four-fold rotoinversion (combination of 90° rotation and spatial inversion) symmetry.

When an electric current Iz is applied along the z direction, such asymmetrically warped cylindrical Fermi surfaces are shifted along the z direction. This shift breaks the four-fold rotoinversion symmetry of the total Fermi surfaces, resulting in two-fold symmetry (left panel of Fig. 1f). More specifically, the valleys A and B are non-equivalent in terms of size and anisotropy over the entire kz range for nonzero Iz (right panels of Fig. 1f). Note that the electronic (valley) nematicity is induced not by an electric field but by an electric current, as proven by analysing the magnetic point group of \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric systems21.

For revealing the impact of such current-induced nematic deformation of Dirac valleys on transport phenomena, angular magnetoresistance (AMR) measured along the c axis by rotating the field within the ab plane is promising. Owing to the strong anisotropy of each Dirac valley in this material, the interlayer resistivity exhibits large four-fold AMR with sharp angle dependence (Fig. 2b)45,46, which is of great advantage to detect broken four-fold symmetry. Considering that the deformation of valleys is induced by current, the change in AMR should be proportional to current density, which results in a nonreciprocal (i.e. diode-like) effect on the interlayer resistivity. To detect this, we measured the second-harmonic component of voltage drop between the terminals as well as the conventional first-harmonic component.

a SEM image of the micro-fabricated device of SrMnBi2. b Schematic illustration of the measurement of angular magnetoresistance effects of interlayer resistivity for the field rotating within the ab plane. c Azimuth-angle φ dependence of the first-harmonic interlayer resistivity \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }\) (upper) and the second-harmonic one \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) (lower) at 1.5 K at 12 T, measured between the terminals 2–3. The magnitude and frequency of the applied current Iz were 200 μA and 23 Hz, respectively. The inset shows the relation between the field direction and Dirac valleys. d \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) versus φ at 1.4 K at 12 T for various Iz. The dotted horizontal line is the baseline for each curve, which is determined as the average of the peak and dip values. Each curve is shifted for clarity. e Peak height of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) (\(\Delta {\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) defined in panel d) versus Iz.

Results and discussion

To achieve high current density without significant current heating effects, we fabricated micro-devices (Fig. 2a) capable of reaching a current density of jz ~5 × 107 A/m2 with an applied current of Iz = 200 μA. Fig. 2c shows the AMR profile (i.e. azimuth angle φ dependence) of the first-harmonic component of interlayer resistivity \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }\) at 1.5 K at 12 T. As a result of precise alignment of the field perpendicular to the c axis using a two-axis rotation probe, we observed the four-fold φ dependence of \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }\). There, \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\) shows narrow dips for B|| [110] and \([\overline{1}10]\) (φ = 0°, 90°, ⋯) while it shows broad peaks for B|| [100] and [010] (φ = 45°, 135°, ⋯), as reported previously45,46. The observed four-fold symmetry of \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\) is consistent with the four-fold rotoinversion symmetry of the Fermi surfaces at jz = 0, since \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\) involves integration over the full kz range (see Methods for a theoretical expression of the first-harmonic component of conductivity). Intuitively, the direction of the current-induced nematic deformation switches by 90° depending on the sign of jz, and its overall effect on \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\) averages out, yielding four-fold symmetry in the linear transport. In contrast, the second-harmonic component of interlayer resistivity \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) exhibits distinct two-fold symmetry: sharp dips are located at φ = 0°, 180° (B||[110], \([\overline{1}\overline{1}0]\)), while sharp peaks are located at φ = 90°, 270° (\({{{{\bf{B}}}}}\parallel [\overline{1}10]\), \([1\overline{1}0]\)). This clearly indicates that the valleys A and B are non-equivalent when nonzero jz is applied, breaking the four-fold symmetry in the nonlinear transport. Reflecting that the deformation of each valley is driven by current, the peak height of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) (denoted by \(\Delta {\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) in Fig. 2d) is almost proportional to jz (Fig. 2e). It should be noted here that essentially the same two-fold symmetric \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) was observed in a microfabricated device with a different surface orientation (Fig. S3), indicating that the present results are independent of the crystal cutting geometry.

The profile of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) strongly depends on magnetic field (Fig. 3b). At 2 T, it exhibits a sine-like curve with two-fold symmetry. However, with increasing field, the dip (peak) structures located at φ = 0°, 180° (φ = 90°, 270°) progressively evolve, accompanied by the gradual change in the weak background component. As discussed below, the observed variation in \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) is explained by the field dependence of \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\); the dips of \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\) (at φ = 0°, 90°, 180°, ⋯) become deeper and narrower with increasing field (Fig. 3a).

a, b φ dependences of \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }\) (a) and \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) (b) for SrMnBi2 at 1.5 K for Iz=200 μA for various magnetic fields. The solid curves are the fitted results of the experimental data on the basis of the empirical equation (see the main text). c, d Magnetic-field (B) dependence of the fitted parameters. σ2D (c) and r (c) represent the parameters of AMR, determined by fitting \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }\) [Eq. (1)]. ε2D (d) and εr (d) represent the current-induced variations of σ2D and r, respectively, determined by fitting \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) [Eq. (5)]. The error bars indicate the uncertainties arising from the fitting.

To formulate the relation between \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) and \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\), we here employ a phenomenological model of interlayer magnetoconductivity \({\sigma }_{zz}\,(=1/{\rho }_{zz}^{\omega })\) taking account of the in-plane anisotropy of quasi-2D Dirac valley (Fig. 1d)45,46,47:

where σ2D (σ3D) is the relative contribution of each quasi-2D Dirac valley (all 3D Fermi surfaces from the parabolic bands)45,46. r is the anisotropic factor of magnetoconductivity, resulting in the maximum (minimum) conductivity for the field along the shorter (longer) axis of the elliptic Dirac valley. Note here that the first (second) term corresponds to the contribution from the valley A (B), which gives σzz peaks, i.e. \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }\) dips at φ = 90°, 270° (φ = 0°, 180°). The experimental profiles of \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\) at various magnetic fields are nicely fitted by Eq. (1), as denoted by solid curves in Fig. 3a. The fitted values of r and σ2D are summarised in Fig. 3c. Reflecting the deeper and narrower dips in \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\) at higher fields, the r value monotonically increases with increasing field, whereas the σ2D is almost independent of field (the same is true for σ3D, see Fig. S2). These fitted results are consistent with those reported in the literatures45,46.

We now take account of the impact of the current-induced nematicity on Eq. (1). Considering that the valleys A and B are non-equivalent in the presence of jz, the nematicity can be incorporated as current-induced changes in r and σ2D as follows

where ϵr(∝jz) and ϵ2D(∝jz) are dimensionless variations in r and σ2D, respectively. Note here that the + sign corresponds to the first term (valley A) in Eq. (1), while the − sign corresponds to the second term (valley B) in Eq. (1). The resultant variation in σzz is given to the first order of ϵr and ϵ2D by (see “Methods”)

where

Since ϵr and ϵ2D are proportional to jz, δσzz is also proportional to jz, corresponding to the nonreciprocal component of the interlayer conductivity. By converting the nonreciprocal conductivity to resistivity using the relation \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }=-\frac{\delta {\sigma }_{zz}}{{({\sigma }_{zz})}^{2}}\) (see “Methods”), we fit the experimental \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) profiles at various fields, as shown in Fig. 3b. For this fitting, ϵ2D and ϵr were treated as adjustable parameters, while σ2D and r were fixed to the values obtained from fitting \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\) at each field (Fig. 3c). The experimental \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) profiles are well reproduced by Eq. (5) regardless of field, as indicated by the solid curves in Fig. 3b. This demonstrates that the field dependence of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) arises solely from the field dependence of \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\varphi )\). The extracted values of ϵ2D and ϵr are nearly field-independent and are of the order of 10−5 (Fig. 3d). Consequently, the magnitude of current-induced nematicity is estimated to be of the order of 10−5 for jz ~5 × 107 A/m2 (Iz = 200 μA). In the previous study, current-induced lattice displacement was measured in EuMnBi2, where the largest strain was ~1.4 × 10−8 at jz ~4 × 104 A/m2 at the lowest temperature36. This corresponds to the strain of ~2 × 10−5 at jz ~5 × 107 A/m2 (the same jz used in this study). Thus, the nematicity estimated from the AMR profile is of the same order of magnitude as that revealed by the lattice displacement measurements.

Here, we discuss the temperature dependence of ρ2ω(ϕ). The amplitude of the ρ2ω(ϕ) peaks and dips decreases with increasing temperature and nearly vanishes above 30 K (Fig. S4d), which is well below the Néel temperature TN = 295 K40. This arises primarily from the suppression of the AMR \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\phi )\) at elevated temperatures (Fig. S4c), since \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\phi )\) originates from the current-induced modulation of \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\phi )\). Additionally, a decrease in the current-induced nematicity (i.e. ϵ2D and ϵr) with increasing temperature, as was previously reported in the lattice displacement measurements in EuMnBi236, may further contribute to the more rapid suppression of ρ2ω(ϕ) compared to \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }(\phi )\). These results suggest that the temperature dependence of ρ2ω(ϕ) involves multiple underlying mechanisms.

Finally, we demonstrate the detection and control of magnetic domains in the present \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnet. Fig. 4c, d show the profiles of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) for the two adjacent devices #1 and #2, respectively, after cooling from room temperature without applying any field or current. Notably, the positions of the sharp peaks and dips of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) are reversed between #1 and #2, apart from the relatively large background component in #2. This clearly indicates that the sign of ϵr and ϵ2D, i.e. the domain of antiferromagnetic order, differs between the two devices, even within the same micro-fabricated crystal (inset to Fig. 4c, d).

a SEM image of the neighbouring devices. The interlayer resistivity in device #1 was measured between terminals 2–3, while in device #2, it was measured between terminals 1–2. b Schematic showing the direction of the electric current (I) along [001] and the magnetic field (B) along [110] for domain poling. c, d φ dependence of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\phi )\) in devices #1 (c) and #2 (d) at 1.5 K and 12 T for Iz = 200 μA before domain poling. e, f Corresponding \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\phi )\) profiles for devices #1 (e) and #2 (f) after domain poling by current-field cooling, showing an inversion of the peak and dip positions in device #1. The insets illustrate the domain of antiferromagnetic order in the Mn-Bi layers of each device.

To align the domains, we employed a poling procedure conducted above TN. Symmetry analysis predicts that the domains of \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnetic order in this nonpolar system can be aligned by applying an electric current and a magnetic field orthogonal to each other, as illustrated in Fig. 4b (see discussions below)48. To achieve this experimentally, we applied a current of 1 mA (jz ~3 × 108A/m2) along [001] and a field of 18 T along [110] at 305 K (>TN), and then cooled the sample to 4.2 K. After poling, we repeated the AMR measurements at 1.5 K and 12 T. In device #1, the peak and dip of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) are inverted compared to the previous measurement without poling (Fig. 4e). On the other hand, in device #2, the magnitude of the peak and dip of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }(\varphi )\) is enhanced while keeping their positions (Fig. 4f). These results indicate that the antiferromagnetic domains in both devices were aligned to the original domain in device #2 through the poling procedure, thereby demonstrating electric-magnetic manipulation of the nonpolar \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnetic order. We note that the gradual background component in device #2 does not change before and after the poling, suggesting that it may arise from pinned domains and/or other extrinsic effects.

We next discuss the mechanisms underlying this control of antiferromagnetic domains in the present material. Recently, several current-driven domain control methods have been developed for metallic antiferromagnets, although their variety remains limited49,50. For \({{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}\) odd antiferromagnets with spin-split bands3, conventional control mechanisms, similar to those in ferromagnets, can be employed. Examples include spin-orbit torque switching at the interfaces of artificial heterostructures12,13,14. In contrast, the control mechanisms for \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\) -symmetric antiferromagnets with spin-degenerate bands are significantly more intricate. In the polar systems, such as CuMnAs15,27 and Mn2Au51, current-induced switching was achieved via the sublattice-dependent spin-momentum locking52,53. However, in nonpolar systems like SrMnBi2, the absence of polarity (p-wave) in momentum space prevents the domain switching using current alone. Instead, the higher-order f-wave polarity in momentum space can be utilised. To this end, we have applied an in-plane field, effectively rendering the system polar and enabling current-induced switching. This combined electric and magnetic manipulation of \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\) -symmetric antiferromagnetic domains provides a novel protocol distinct from those employed for \({{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}\) -odd or polar antiferromagnets currently under active investigation.

For \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnets, a variety of nonlinear conduction phenomena, classified by the dependence on the relaxation time, were theoretically predicted23. In this context, our study focuses on the Drude component to provide direct evidence of current-induced electronic nematicity, manifested as nonlinear interlayer conduction along the high-symmetry c−axis under a magnetic field. In addition, SrMnBi2 is also predicted to exhibit other types of nonlinear in-plane conduction along the ab plane, such as the (zero-field) nonlinear Hall effect arising from the quantum geometric component27,28,29. Exploring in-plane nonlinear responses may thus represent an important direction for future research in nonpolar \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnets.

To conclude, we report the observation of current-induced electronic nematicity in the nonpolar \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnet SrMnBi2 by measuring the nonreciprocal angular magnetoresistance (AMR) effect. The breaking of the original four-fold rotoinversion symmetry is detectable via the valley degrees of freedom of Dirac fermions in the Bi square net, which is adjacent to the Mn-Bi tetrahedral layer exhibiting \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnetic order. By employing a phenomenological model of the AMR effect attributed to elliptic Dirac valleys, we quantitatively reproduce the two-fold nonreciprocal AMR signal, demonstrating the current-induced lifting of the valley degeneracy. The layered structure incorporating a Dirac fermion layer in this material offers a novel platform for the electrical control of valleys by the \({{{{\mathcal{PT}}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnetic order. Our findings may pave the way for developing unconventional spintronic and valleytronic devices, thereby broadening the scope of antiferromagnetic spintronics.

Methods

Sample preparation and device fabrication

Single crystals of SrMnBi2 were grown by a Bi self-flux method37,46,54. The alumina crucible filled with Sr, Mn, and Bi metal ingots (Sr:Mn:Bi = 1:1:9) was sealed in an evacuated quartz tube. The ampoule was heated at 1050 °C and then cooled to 400 °C at the rate of 2 °C/h, where excess Bi flux was decanted by centrifuge.

To measure the interlayer resistivity with a high current density, we fabricated microstructured devices using a focused ion beam with 30 kV of the acceleration voltage for the Ga ion beam at VERSA-3D (FEI Company). The typical dimension of the fabricated device is 2μm × 2μm × 12 μm with 8 voltage terminals and 2 current terminals.

Transport measurement

\({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }\) and \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) were measured by the conventional AC-lockin measurement with a typical frequency of 23 Hz. \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\) was obtained as \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }=({V}_{zz}^{2\omega }/{I}_{z})/(l/S)\), where \({V}_{zz}^{2\omega }\) is the imaginary part of the second-harmonic voltage drop, Iz is the RMS value of AC current, l is the length of voltage terminals, and S is the cross section of current path. To obtain the B dependence, we symmetrise \({V}_{zz}^{2\omega }\) with respect to B. The measurements were performed using commercial superconducting magnets, where the direction of magnetic field was controlled using a probe equipped with a two-axis rotating stage in Institute for Materials Research, Tohoku University.

Theoretical expression of first-harmonic conductivity along the c-axis for in-plane magnetic fields

From the Boltzmann equation, the conductivity along the c∣∣z-axis under the magnetic field B in the present material is given by55,56,57,58:

where f is the Fermi distribution function, τ is the constant scattering time. vz(k) is the z component of Fermi velocity, which is nonzero due to kz dispersion E(k) of quasi 2D Fermi surfaces. In the semiclassical picture, electron motion in a magnetic field is described by the equation of motion:

which determines the time evolution of k(t). The term 〈vz(k, t)〉 represents the time-averaged z component of the velocity within the relaxation time τ.

Formulation of the fitting function of \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\)

Considering the current-induced nematicity described by Eq. (2), the variation of the first term (associated with valley A) in Eq. (1) can be expressed, to the first order of ϵr and ϵ2D, as:

The second and third terms in the above equation originate from the current-proportional variations in r and σ2D, respectively. Similarly, the variation of the second term in Eq. (1) can be derived to the first order of ϵr and ϵ2D, resulting in the total variation given by δσzz(φ) in Eq. (5).

The relation between the current density jz and the applied electric field Ez is expressed as:

From this, we obtain

where \(\frac{1}{{\sigma }_{zz}}\) and \(-\frac{\delta {\sigma }_{zz}}{{\sigma }_{zz}^{2}}\) in the final equation correspond to \({\rho }_{zz}^{\omega }\) and \({\rho }_{zz}^{2\omega }\), respectively.

First-principles calculation

We performed first-principles band structure calculations based on the density functional theory with the generalised gradient approximation with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof parametrization59 and the projector augmented wave (PAW) method as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package60,61,62,63,64. We used the experimental crystal structure65 with the antiferromagnetic ordering shown in Fig. 1a. Core-electron states in PAW potentials were [Ar]3d10, [Ar], and [Xe]5d10 for Sr, Mn, and Bi, respectively. We used a plane-wave cutoff energy of 400 eV for Kohn-Sham orbitals with including the spin-orbit coupling. A 16 × 16 × 16 k-mesh was used. After first-principles band calculation, we extracted Mn-d + Bi-p Wannier orbitals using Wannier90 software66,67,68. Fermi surfaces were depicted using the tight-binding model consisting of these Wannier orbitals.

Data availability

All data needed to support the conclusions are presented in the paper and the Supplementary Information. Raw data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Baltz, V. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018).

Jungwirth, T. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231–241 (2016).

Smejkal, L. et al. Anomalous Hall antiferromagnets. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 482–496 (2022).

Nakatsuji, S., Kiyohara, N. & Higo, T. Large anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet at room temperature. Nature 527, 212–215 (2015).

Nayak, A. K. et al. Large anomalous Hall effect driven by a nonvanishing Berry curvature in the noncolinear antiferromagnet Mn3Ge. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501870 (2016).

Ikhlas, M. et al. Large anomalous Nernst effect at room temperature in a chiral antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 13, 1085–1090 (2017).

Ghimire, N. J. et al. Large anomalous Hall effect in the chiral-lattice antiferromagnet CoNb3S6. Nat. Commun. 9, 3280 (2018).

Park, P. et al. Field-tunable toroidal moment and anomalous Hall effect in noncollinear antiferromagnetic Weyl semimetal Co1/3TaS2. Npj Quantum Mater. 7, 42 (2022).

Takagi, H. et al. Spontaneous topological Hall effect induced by non-coplanar antiferromagnetic order in intercalated van der Waals materials. Nat. Phys. 19, 961–968 (2023).

Feng, Z. et al. An anomalous Hall effect in altermagnetic ruthenium dioxide. Nat. Electron. 5, 735–743 (2022).

Reichlova, H. et al. Observation of a spontaneous anomalous Hall response in the Mn5Si3 d-wave altermagnet candidate. Nat. Commun. 15, 4961 (2024).

Higo, T. et al. Perpendicular full switching of chiral antiferromagnetic order by current. Nature 607, 474–479 (2022).

Yoon, J. Y. et al. Handedness anomaly in a non-collinear antiferromagnet under spin-orbit torque. Nat. Mater. 22, 1106–1113 (2023).

Han, J. et al. Room-temperature flexible manipulation of the quantum-metric structure in a topological chiral antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 20, 1110–1117 (2024).

Wadley, P. et al. Electrical switching of an antiferromagnet. Science 351, 587–590 (2016).

Watanabe, H. & Yanase, Y. Magnetic parity violation and parity-time-reversal-symmetric magnets. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 36, 373001 (2024).

Hayami, S. & Kusunose, H. Unified description of electronic orderings and cross correlations by complete multipole representation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 93, 072001 (2024).

Fedchenko, O. et al. Direct observation of antiferromagnetic parity violation in the electronic structure of Mn2Au. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 425501 (2022).

Lytvynenko, Y. et al. Control of the asymmetric band structure in Mn2Au by a ferromagnetic driver layer. Phys. Rev. B 108, 104413 (2023).

Gao, Y., Yang, S. A. & Niu, Q. Field-induced positional shift of Bloch electrons and its dynamical implications. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 166601 (2014).

Watanabe, H. & Yanase, Y. Group-theoretical classification of multipole order: emergent responses and candidate materials. Phys. Rev. B 98, 245129 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Switchable magnetic bulk photovoltaic effect in the two-dimensional magnet CrI3. Nat. Commun. 10, 3783 (2019).

Watanabe, H. & Yanase, Y. Nonlinear electric transport in odd-parity magnetic multipole systems: application to Mn-based compounds. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043081 (2020).

Holder, T., Kaplan, D. & Yan, B. Consequences of time-reversal-symmetry breaking in the light-matter interaction: Berry curvature, quantum metric, and adiabatic motion. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033100 (2020).

Fei, R., Song, W. & Yang, L. Giant photogalvanic effect and second-harmonic generation in magnetic axion insulators. Phys. Rev. B 102, 035440 (2020).

Ahn, J., Guo, G.-Y. & Nagaosa, N. Low-frequency divergence and quantum geometry of the bulk photovoltaic effect in topological semimetals. Phys. Rev. X 10, 041041 (2020).

Godinho, J. et al. Electrically induced and detected Néel vector reversal in a collinear antiferromagnet. Nat. Commun. 9, 4686 (2018).

Gao, A. et al. Quantum metric nonlinear Hall effect in a topological antiferromagnetic heterostructure. Science 381, 181–186 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. Quantum-metric-induced nonlinear transport in a topological antiferromagnet. Nature 621, 487–492 (2023).

Takagi, T. et al. Photogalvanic spectroscopy on MnBi2Te4 topological insulator thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 163102 (2024).

Watanabe, H. & Yanase, Y. Magnetic hexadecapole order and magnetopiezoelectric metal in Ba1−xKxMn2As2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 064432 (2017).

Chazono, M., Watanabe, H. & Yanase, Y. Superconducting piezoelectric effect. Phys. Rev. B 105, 024509 (2022).

Varjas, D., Grushin, A. G., Ilan, R. & Moore, J. E. Dynamical piezoelectric and magnetopiezoelectric effects in polar metals from Berry phases and orbital moments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 257601 (2016).

Shiomi, Y. et al. Observation of a magnetopiezoelectric effect in the antiferromagnetic metal EuMnBi2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 127207 (2018).

Shiomi, Y., Koike, Y., Abe, N., Watanabe, H. & Arima, T. Enhanced magnetopiezoelectric effect at the Néel temperature in CaMn2Bi2. Phys. Rev. B 100, 054424 (2019).

Shiomi, Y. et al. Large magnetopiezoelectric effect in EuMnBi2 single crystal at low temperatures. Sci. Rep. 10, 7574 (2020).

Park, J. et al. Anisotropic Dirac fermions in a Bi square net of SrMnBi2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 126402 (2011).

Wang, J. K. et al. Layered transition-metal pnictide SrMnBi2 with metallic blocking layer. Phys. Rev. B 84, 064428 (2011).

Wang, K. et al. Quantum transport of two-dimensional Dirac fermions in SrMnBi2. Phys. Rev. B 84, 220401(R) (2011).

Guo, Y. F. et al. Coupling of magnetic order to planar Bi electrons in the anisotropic Dirac metals AMnBi2 (A = Sr, Ca). Phys. Rev. B 90, 075120 (2014).

Lee, G. et al. An anisotropic Dirac dispersion in the layered Bi square net system AMnBi2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 245104 (2013).

Feng, Y. et al. Strong anisotropy of Dirac cones in SrMnBi2 and CaMnBi2. Sci. Rep. 2, 590 (2014).

Jia, L.-L. et al. Observation of well-defined quasiparticles at a wide energy range in a quasi-two-dimensional system. Phys. Rev. B 90, 035133 (2014).

Sakai, H. High-field studies on layered magnetic and polar Dirac metals: novel quantum transport phenomena coupled with spin-valley degrees of freedom. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 91, 101001 (2022).

Jo, Y. J. et al. Valley-polarized interlayer conduction of anisotropic Dirac fermions in SrMnBi2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 156602 (2014).

Kondo, M. et al. Angular dependence of interlayer magnetoresistance for layered Dirac antiferromagnets. JPS Conf. Proc. 30, 011016 (2020).

Zhu, Z. et al. Field-induced polarization of Dirac valleys in bismuth. Nat. Phys. 8, 89–94 (2012).

Watanabe, H. & Yanase, Y. Symmetry analysis of current-induced switching of antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 98, 220412 (2018).

Jiang, N. et al. Electric current control of spin helicity in an itinerant helimagnet. Nat. Commun. 11, 1601 (2020).

Masuda, H. et al. Room-temperature chirality switching and detection in a helimagnetic MnAu2 thin film. Nat. Commun. 15, 1999 (2024).

Bodnar, S. Y. et al. Writing and reading antiferromagnetic Mn2Au by Néel spin-orbit torques and large anisotropic magnetoresistance. Nat. Commun. 9, 348 (2018).

Železný, J. et al. Relativistic néel-order fields induced by electrical current in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 157201 (2014).

Yanase, Y. Magneto-electric effect in three-dimensional coupled zigzag chains. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 83, 014703 (2014).

Masuda, H. et al. Quantum Hall effect in a bulk antiferromagnet EuMnBi2 with magnetically confined two-dimensional Dirac fermions. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501117 (2016).

Osada, T., Kagoshima, S. & Miura, N. Third angular effect of magnetoresistance in quasi-one-dimensional conductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 5261–5264 (1996).

Lee, I. J. & Naughton, M. J. Effective electrons and angular oscillations in quasi-one-dimensional conductors. Phys. Rev. B 57, 7423–7426 (1998).

Hanasaki, N., Kagoshima, S., Hasegawa, T., Osada, T. & Miura, N. Contribution of small closed orbits to magnetoresistance in quasi-two-dimensional conductors. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1336–1339 (1998).

Takatsu, H. et al. Extremely large magnetoresistance in the nonmagnetic metal PdCoO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 056601 (2013).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab initio total-energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Cordier, G. & Schäfer, H. Preparation and crystal structure of BaMnSb2, SrMnBi2 and BaMnBi2. Z. Naturforsch. B 32, 383 (1977).

Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized generalized Wannier functions for composite energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 56, 12847 (1997).

Souza, I., Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized Wannier functions for entangled energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 65, 035109 (2001).

Pizzi, G. et al. Wannier90 as a community code: new features and applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 165902 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Y. Onose and A.P. Mackenzie for helpful discussions. This work was partly supported by the JSPS KAKENHI Grants no. 22H00109 (H.S.), 22K18689 (H.S.), 23H00268 (H.S.), 23H04862 (H.S.), 23H04014 (M. Kimata), 23H04868 (M. Kimata), 23KK0052 (M. Kimata), 22H04933 (M. Kimata), 23K22447 (M. Kimata), 21H05470 (M. Kimata), and 24H01622 (N.H.), the Asahi Glass Foundation (H.S.) and the Spintronics Research Network of Japan (Spin-RNJ) (N.H.). A part of this work was carried out under the Visiting Researcher’s Program (H.S.) and the GIMRT Program (H.S.) of the Institute for Materials Research, Tohoku University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S. conceived the project and designed the experiments. Y.M., H.S., M. Kondo, H.M., and N.H. grew the single crystals and performed the fundamental characterisations. M. Kimata fabricated the devices. Y.M., M. Kimata, and H.S. measured the transport properties under rotating magnetic fields. Y.M. and H.S. analysed the data with theoretical input from H.W. and Y.Y. M.O. performed the first-principles calculations. H.S. wrote the manuscript with input from Y.M., H.W. and Y.Y. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakai, H., Miyamoto, Y., Kimata, M. et al. Transport evidence of current-induced nematic Dirac valleys in a parity-time-symmetric antiferromagnet. Nat Commun 16, 11112 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67229-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67229-y