Abstract

The developmental shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing GABA responses is a pivotal step in the maturation of GABAergic transmission and cortical circuits; classically documented in principal neurons during the first postnatal week in the mouse cortex. Surprisingly, whether maturation of GABA-mediated responses follows the same temporal pattern in cortical interneurons (INs) remains unresolved. Leveraging an array of methods, a high-resolution cortical development mouse atlas and single-cell RNA sequencing, we identify and comprehensively characterize a population of early-maturing cortical INs in mice, distinguished by KCC2 expression at embryonic stages and concomitant hyperpolarizing GABAA responses at birth. These early KCC2-expressing INs exhibit precocious intrinsic excitability, synaptic integration, and dendritic complexity at birth, contrasting delayed maturation in principal neurons and other INs. Spatial transcriptomics and differential gene expression (DGE) analyses reveal early KCC2-expressing INs localize predominantly to layer 5, express somatostatin, and show upregulation of synaptogenic genes, consistent with the recorded elevated synaptic activity. Crucially, evolutionary conservation of early KCC2-expressing INs in humans was demonstrated with analogous genetic profiles enriched for signaling and synaptic maturation pathways. This work resolves a critical gap in developmental neurobiology, demonstrating heterogenous GABAergic functional maturation within IN subpopulations and establishing KCC2 as a marker of early-maturing INs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

GABAergic INs are pivotal orchestrators of a myriad of phenomena in the central nervous system (CNS), including signal modulation, network dynamics, cortical rhythms, information processing, and excitation-inhibition balance. They hold salient roles in shaping the circuit edifice of the developing brain1,2,3,4,5. Specifically in the cortex, INs guide functional development of cortico-stratal connectivity, long range projections, and specialized micro-circuits2,6,7. While their significance and dysfunction implicated in disease states are being comprehended in the recent decades8,9,10,11,12,13,14, numerous aspects with respect to their maturation remain nebulous15. For example, while pioneering work in the recent years has illumined early genetic programs in nascent INs and deduction of their final fates16,17,18,19, genetic programs involved in the developmental maturation of the diversity of INs with respect to morphology, electrophysiology, and biomarker expression20 are still relatively uncharted. Identifying reliable markers that distinguish IN populations at varying maturation stages of embryonic and perinatal (postnatal day 0–2) stages is essential, as it allows untangling of heterogenous neuronal entities and subsequently comprehend their morpho-physiological features and distinct developmental trajectories.

The postnatal developmental shift of GABAergic function and polarity of GABAA receptor responses from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing is a well-documented phenomenon in principal neurons of various brain regions21,22,23,24,25,26,27. This developmental shift, induced by an upregulation of the cation chloride co-transporter KCC2, is a crucial step in the maturation process of principal neurons. Though examined in principal neurons, where it typically occurs after post-natal day 522,28, the shift is less explored in the context of INs. Interestingly, whether the development of hyperpolarizing inhibition occurs simultaneously in INs and principal cells is not known. Furthermore, there is a lacuna in the characterization of KCC2 expression in healthy human encephalic tissue, with a sparse number of existing studies29,30. Specifically in prenatal stages, cell-type specific expression patterns of KCC2 are uncharted, which is exigent for elucidating discrete neuronal maturation trajectories and comprehending human neurodevelopment.

Utilizing a high-resolution cortical development bioinformatic atlas31, and complementary single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data sets18,19, we capture the expression pattern of Kcc2 in INs across developmental stages and extricate subpopulations that have embryonic Kcc2 expression in the mouse somatosensory cortex. Our electrophysiological investigation demonstrates functional KCC2 in a subset of layer 5 interneurons at birth, where the developmental shift in GABAergic signalling occurs earlier than in principal neurons and other interneurons. This early KCC2 expression associates with precocious morpho-physiologies, gene expression profiles linked to synaptogenesis, and their demonstrated functional synaptic activity and network integration.

Extending these findings, analysis of a human prenatal single-nucleus RNA-seq atlas32, reveals evolutionarily conserved subpopulation of KCC2-expressing interneurons co-expressing lineage markers consistent with MGE origin. This population shows a unique gene expression profile enriched in synaptic and signaling genes, reflecting early functional maturation. Overall, our study establishes KCC2 as a reliable marker for a subpopulation of early-maturing interneurons in the mouse and human cortex, characterized by advanced morphophysiological features, exclusive upregulation of synaptic and signaling genes, and elevated synaptic activity. Importantly, we show evidence for the heterogeneity of GABAergic function in the developing brain and identify the first neuronal population with hyperpolarizing GABAergic actions in the perinatal mouse cortex. This holds crucial implications for dissecting functional cortical development and in the advent of novel neuro-therapeutic and iatric interventions.

Results

KCC2 expression in interneurons at E18 precedes the expression in glutamatergic neurons

Most studies on KCC2 expression have focused on late postnatal stages, particularly around the second postnatal week. By contrast, its role and expression patterns during prenatal development, especially in interneurons (INs), remain poorly defined. Although a limited number of studies have examined KCC2 expression during embryonic development25,33,34,35, none have systematically addressed interneuronal populations in this context.

To fill this gap, we first examined embryonic cortices to determine the earliest onset of KCC2 expression in INs, propelled by existing literature on KCC2 function in interneuronal migration36,37. As expected for a neuron-specific cation-chloride cotransporter30,38,39,40, immunohistochemical analyses of neocortices of GAD2Cre-GCamp mice on embryonic day 18 (E18) (Fig. 1a) revealed KCC2 expression restricted to neuronal populations (Supplementary Fig. 1a, KCC2 TuJ1 co-staining) with exclusive prominence in the INs (Fig. 1a–c). Expression was evident in a subset of INs within the cortical plate (CP), more abundantly in the subplate (SP) and intermediate zone (IZ), but absent in the marginal zone (MZ) (Fig. 1b, c). In some interneurons, KCC2 expression at confocal microscopy resolution appeared localized to the membrane, while others showed more diffuse cytoplasmic expression (Fig. 1b). GFP-negative cells (GAD2-negative, majority being putative principal cells) were devoid of KCC2 expression (Fig. 1c). INs were present in the Marginal zone (MZ) Cortical plate (CP), Subplate (SP), and Intermediate zone (IZ) (Fig. 1c) as seen by the GFP-positive GAD2-expressing IN populations in these regions at E18.

a Schematic of E18 mouse neocortical strata: marginal zone (MZ), cortical plate (CP), subplate (SP), intermediate zone (IZ), subventricular zone (SZ), ventricle (V). Middle: DAPI-stained E18 brain slice showing area for panel b. Right: Co-staining of GAD2+ INs (green) and KCC2 (red). b Immunohistochemistry shows KCC2 expression (red) in MZ, CP, SP, and IZ. Scale bars 100 µm, 20 µm, 10 µm, 10 µm, for panels from left to right. c Higher magnification of KCC2 in GAD2+ INs within CP and SP layers, scale bars 100 µm, 25 µm, 15 µm, 15 µm from left to right. d EM images reveal KCC2 immunogold puncta in IN perikarya and dendrites, mainly cytoplasmic. Scale bars 3 µm, 1.5 µm, 1 µm, 0.1 µm, left to right. For a–d, the immunostainings and immunogold EM stainings were each repeated in 4 animals and 10 slices independently, with similar results. e Schematic of newborn (P0) mouse and neocortical zones. f Immunostaining for KCC2 (red), GAD2 (green), and layer 5 marker CTIP2 (blue) at P0 shows KCC2 strong expression in layer 5, co-localizing with GAD2+ INs but absent from CTIP2+ GAD2-negative PNs. Scale bars 100 and 30 µm. g Quantification of laminar distribution of KCC2+ INs and GAD2-KCC2 co-localization at P0 (n = 3 animals, 6 slices; **p = 0.0022, *p = 0,0282 two-tailed Mann–Whitney, One-way ANOVA). h High-resolution confocal images confirm KCC2 membrane localization on GAD2+ GFP+ INs. KCC2-GAD2 colocalization seen in white and interneurons, (GAD2-GFP) in green. Scale bars 20 and 10 µm. i Quantification of membranal vs intracellular KCC2 in INs at P0 via high resolution deconvolved confocal laser scanning microscopy (n = 4 animals, 10 cells). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM in all plots. Source data are provided as a Source data file. See Supplementary data 10 for detailed statistics. Panel a and e insets were created in BioRender. Srinivasan, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/j3ptv77.

To further define subcellular localization, we complemented light microscopy with immunogold electron microscopy (EM). Consistent with prior studies in early postnatal neocortex and P2 neocortical cells41, KCC2 particles at E18 were primarily found in perikarya and dendrites, with enrichment in transport vesicles within the cytoplasm, suggesting immature trafficking to the membrane (Fig. 1d). These findings demonstrate early, interneuron-specific expression of KCC2 in the embryonic neocortex. The differences in the spatiotemporal patterns of KCC2 expression36 in different embryonic interneuronal populations allude to the varying maturation trajectories of interneurons, in line with divergent migration programs within discrete cortical strata.

To probe whether a temporal disparity in KCC2 expression and upregulation persists between interneurons (INs) and glutamatergic principal neurons, and to further understand the laminar distribution of KCC2 INs, we extended our immunohistochemical analysis to the somatosensory cortex at birth. Previous research, focusing on principal neurons, identified KCC2 upregulation in hippocampal principal neurons by postnatal day 5, with expression reaching adult levels by postnatal day 928 To test whether INs acquire KCC2 earlier, we analyzed the somatosensory barrel field cortex (S1BF) at postnatal day 0 (P0) (Fig. 1e). Using GAD2Cre-GCamp (expressing GFP in GAD2 positive INs) mice, we analyzed KCC2 expression across layers 1–6 of the somatosensory barrel field cortex (SIBF) and examined laminar expression of KCC2 (Fig. 1f, g), subsequently focusing on layer 5 due to its distinct connectivity and pivotal role in regulating cortical output42,43,44. KCC2 was strongly expressed in INs, particularly in layer 5, but was undetectable in CTIP2-positive, GAD2-GFP-negative putative principal neurons. Nearly all KCC2-positive cells were interneurons, underscoring the cell-type specificity of expression at birth (Fig. 1f–h).

To resolve intracellular localization, we applied high-resolution deconvolved confocal laser scanning microscopy and quantified membrane versus cytoplasmic distribution of KCC2 in INs. At P0, only 7.5 ± 0.7% of KCC2 signal was membrane-associated (Fig. 1i), consistent with prior observations of both intracellular and perisynaptic pools proximal to the membrane45,46,47,48 during early development, though at lower membrane ratios than in adults. The expression seen in INs at birth (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 1b) was of equal prominence to that seen at postnatal day 4 (P4) (Supplementary Fig 1c). EM analysis at P4 confirmed that the majority of KCC2 particles 87 ± 0.4% remained cytoplasmic, with 13 ± 0.4% associated with the plasma membrane, based on analysis of 19 neurons (Supplementary Fig. 1c). This propelled further investigations into the functionality of KCC2 at these perinatal stages using electrophysiological methods.

Together, these results reveal robust embryonic and perinatal expression of KCC2 in interneurons but not in principal neurons, highlighting a developmental asynchrony between these populations. This disparity suggests distinct maturation trajectories and may contribute to differential GABAergic functionality at birth.

Functional KCC2 in perinatal interneurons drives an early developmental shift in GABAergic signaling polarity

Immunohistochemical analyses revealed an early expression of KCC2 in INs during embryonic and postnatal stages. However, these methods do not clarify whether KCC2 is functional in perinatal IN populations. Hence, we aimed to investigate this, as no studies thus far have examined GABAergic polarity or KCC2 function in GABAergic INs at birth or perinatal stages. Additionally, we set out to inspect whether the disparity of KCC2 expression between glutamatergic principal neurons and GABAergic INs translates to a functional difference between the two populations at birth and perinatal stages. Utilizing the method of gramicidin perforated patch-clamp recordings (Fig. 2a), we scrutinized KCC2 function in GAD2-expressing INs and glutamatergic principal neurons of layer 5 in the SIBF. The cell cytoplasms were collected for post-hoc single-cell transcriptomics for confirming cell identities.

a Illustration of electrode placement in somatosensory barrel-field cortex (SIBF) layer 5 interneurons in perinatal mice, and gramicidin perforated-patch recording configuration. b I–V plots and example traces from gramicidin recordings of interneurons (INs) and principal neurons (PNs) of layer 5 c Quantification of GABAergic reversal potential (EGABA), GABAergic driving force (DFGABA), resting membrane potential (RMP), intracellular chloride (Cl−) calculated using the GHK equation, and an RMP vs EGABA plot; from PNs and INs. n = 56 INs from 10 animals and 21 PNs from 6 animals. ****p ≤ 0.0001: unpaired two-tailed t-test and two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. d Population-level slice recordings demonstrate the overall impact of the drug VU0463271 on KCC2 inhibition. Quantification of EGABA, DFGABA, and RMP from INs with and without application of VU. n = 15 INs with and without VU application from 3 animals. *p = 0.02, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test ****p ≤ 0.0001: unpaired two-tailed t-test and two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. e Same quantifications as in D, in PNs with and without application of VU0463271. n = 8 PNs without VU application and 8 PNs with VU application from 3 animals. Unpaired two-tailed t-test. f Quantification of pairwise recordings of INs and PNs showing cell-specific responses to VU in a KCC2-expression dependent manner, from a subset of INS and PNs in E. INs show heterogeneous sensitivity to VU, while all PNs are insensitive to VU application. *p = 0.0382, paired two-tailed t test. n = 6 INs, n = 5 PNs. g Quantification of EGABA, DFGABA, RMP, and Cli; from KCC2+ and KCC2- interneurons. n = 29 KCC2+ INs and 19 KCC2- INs, 7 animals. **p = 0.0049, ****p = <0.0001, **p = 0.0030; unpaired two-tailed t-tests. h Quantification of EGABA, DFGABA, RMP across P0-P2 reveals no significant variance. n = 4, 3, and 3 animals and 25, 17, and 14 INs at P0, P1, and P2, respectively. One-way ANOVA, unpaired two-tailed t-test. Data presented as mean values ± SEM. Source data provided as a Source data file. Panel a created in BioRender. Srinivasan, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/a5jwigh. Supplementary data 10 for detailed statistics.

Gramicidin recordings revealed that perinatal GAD2-expressing INs, taken as a whole, without separating subtypes, had significantly negative GABA reversal potentials (EGABA) compared to glutamatergic principal neurons (Fig. 2b, c). Furthermore, there was a positive GABAergic driving force (DFGABA), indicating hyperpolarizing GABA function49 in INs, which was significantly higher than in principal cells. Corresponding to EGABA values, estimated intracellular chloride (calculated using the GHK equation) was significantly lower in INs (Fig. 2c). The resting membrane potentials (RMPs) of both these neuronal populations were also significantly different, as INs had a less negative RMP than PNs (Fig. 2c), in line with what is typically observed in INs across development50,51.

We confirmed that the hyperpolarized EGABA, and positive driving force (DFGABA) seen in INs was indeed caused by KCC2-dependent chloride extrusion by using a selective KCC2-antagonist, VU0463271, and examining its effects on EGABA and RMP at the IN and PN population level. The application of the KCC2 antagonist resulted in significant depolarization of EGABA in INs, clarifying that their hyperpolarized EGABA is elicited by KCC2 extrusion (Fig. 2d). The antagonist also had a depolarizing effect on the RMP of INs and a significant effect on the DFGABA of INs, shifting positive driving forces into the negative direction (Fig. 2d). VU0463271 application had no effect on PNs (Fig. 2e), confirming the lack of KCC2 expression in these cells. Within the IN group, pairwise recordings revealed heterogeneity of sensitivity to VU046327, in a KCC2-expression-dependent manner. All PNs showed consistent insensitivity to the drug, due to lack of KCC2 expression (Fig. 2f).

These results revealed that GABA is hyperpolarizing in layer 5 INs already at birth and perinatal stages (P0-P2), and that the developmental shift of GABAergic function is much earlier in INs due to early KCC2 expression and function, where principal neurons show the earliest shift only between p5-722,28. This confirmed the disparity of KCC2 expression between perinatal glutamatergic principal neurons and INs and reflects a fundamental functional difference between the two groups. As indicated in previous research, the gramicidin perforated patch recordings in our study revealed that GABA is still depolarizing in the principal neurons, congruent with the lack of KCC2 expression in this population.

Next, we examined KCC2 expression from single-cell patch-transcriptomics and concomitant gramicidin recordings (Fig. 2g). Notably, KCC2-positive INs had significantly lower GABAergic reversal potentials (EGABA) and significantly higher GABAergic driving forces (DFGABA) than KCC2-negative INs. Consequent to GABAergic reversal potentials, KCC2-positive INs had significantly lower intracellular chloride levels. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in RMP between the two groups (Fig. 2g). We also examined whether there was variance in EGABA, RMP, and DFGABA between postnatal day 0, 1, and 2; and no significant differences were found between INs during these days of what is defined as the perinatal stage52,53,54,55,56,57 (Fig. 2h).

Taken together, these results suggest that a major subpopulation of cortical L5 GABAergic INs mature appreciably faster than principal neurons. These INs, marked by the expression of KCC2, display an earlier functional maturation than others, reflected in hyperpolarizing GABAergic function at birth.

Early KCC2-expressing perinatal interneurons display precocious intrinsic properties

With the observations of remarkably early KCC2 expression and KCC2-driven hyperpolarizing GABAergic function in layer 5 INs, we set out to examine the intrinsic properties and electrophysiological phenotypes of these perinatal INs. While very few studies have examined electrophysiological features of INs in neonates58,59,60, their intrinsic properties at and around birth are unclear.

We conducted whole-cell current-clamp recordings, probing their firing phenotypes and membrane properties, and then collected their somas for post-hoc single-cell transcriptomic analysis, including KCC2 expression (Fig. 3a). The current-clamp recordings revealed significantly higher firing frequencies in KCC2-positive INs in response to depolarizing current steps, at each stimulation intensity than KCC2-negative INs. The maximal firing frequency and rheobase of KCC2-positive INs was significantly higher than KCC2-negative INs (Fig. 3b). We examined whether there was variance in maximal firing frequency between postnatal day 0, 1 and 2, in all INs and KCC2-positive INs, and no significant differences were found in INs between these days of what is defined as the perinatal stage (Supplementary Fig 1d). These data indicate that KCC2-expressing INs exhibit precocious high-firing phenotypes.

a Illustration of protocol for whole-cell current clamp recordings and post-hoc single cell transcriptomics b Left: Example traces of responses to depolarizing step (40 pA) in KCC2+ and KCC2- INs. Quantification of the firing frequency of INs in response to depolarizing current steps, maximal firing frequencies, and rheobase (KCC2+: n = 36 cells, 6 animals, KCC2−: n = 25 cells, 6 animals) ****p < 0.0001 *p = 0.0335. Mixed effects model, unpaired two-tailed t-test, and Mann–Whitney tests. c Left: Action potential phase plots of first four APs from both traces in A. Right: Example traces of action potentials in KCC2+ and KCC2- INs d. Quantification of AP half-width and fast after-hyperpolarization (AHP) current amplitudes input resistance (Rin), and resting membrane potentials (RMP), in both groups. AHP and AP halfwidth: KCC2+: n = 29 cells, KCC2−: n = 16 cells, 6 animals. IR and RMP: KCC2+: n = 36 cells, 5 animals, KCC2−: n = 25 cells, 6 animals. ***p = 0.0004; *p = 0.0210; *p = 0.0146; two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, two-tailed unpaired t-test and two tailed Mann–Whitney test. e Illustration of protocol for biocytin-patch morphology reconstruction. f Immunohistochemistry of biocytin filled INs co-stained for KCC2. Left: KCC2+ IN and inset current clamp trace of response at 40pA step. Right KCC2- IN with corresponding current clamp trace. Inset images depict KCC2 staining. g Above: Scholl analyses graphs of KCC2+ and KCC2− INs. Below: Examples of FITJ -SNT reconstructions of KCC2+ and KCC2− INs, depicting dendritic arborization and morphologies. h Quantification of branch length, total dendritic length, excitability, and correlation of maximal firing frequency with total dendritic length, of KCC2+ and KCC2− INs. Current clamp: n = KCC2+ 18 cells, 3 animals, KCC2- 19 cells, 3 animals. Morphology reconstruction: n = KCC2+ 11, 3 animals and KCC2- 19 cells, 3 animals. ****p < 0.0001; ***p = 0.0003; two-tailed t-test, two-tailed Mann–Whitney tests. Data presented as mean values ± SEM. Source data provided as a Source data file. Panels a, e created in BioRender. Srinivasan, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/1midmp8. Supplementary-data10 for detailed statistics.

Additionally, action potential analyses further accentuated the relatively mature phenotypes of KCC2-positive INs (Fig. 3c). It is well known that AP half-width decreases in INs through the course of development and accompanies their augmented maximal firing frequencies61,62,63. Correspondingly, KCC2-positive INs had a significantly smaller AP half-width than KCC2-negative INs (Fig. 3c, d).

The After-Hyperpolarization (AHP) current is another key electrophysiological signature of several subpopulations of INs, which increases in amplitude as a result of a maturing phenotype1,62,64. This parameter was also significantly different between the two groups, where KCC2-positive INs had a larger AHP amplitude than KCC2-negative INs (Fig. 3d), further evincing their relative electrophysiological maturity.

The input resistance of neurons and INs decreases through the course of development and is lower in mature neuronal populations65,66. Reflective of this, KCC2-expressing INs had a lower input resistance than KCC2-negative INs, substantiating their relatively mature phenotype. Resting membrane potentials were the same across both groups of INs (Fig. 3d). These data indicate at the functional level that KCC2-expressing INs display precocious intrinsic properties and are further ahead in the phenotypical development trajectory compared to KCC2-negative INs.

Early KCC2-expressing perinatal interneurons display markedly mature dendritic morphology

Cortical IN morphologies at birth and early postnatal stages are poorly characterized, despite research that has extensively anatomized interneuron morphologies67, at later developmental stages. After confirming the distinct and mature electrophysiological profiles of KCC2-expressing INs at birth, we ventured into inspecting the morphological features of these unique interneuronal entities of SIBF layer 5. A subset of INs used for electrophysiological investigation was filled with biocytin and processed for morphological characterization (30 INs filled from a total of 98 INs whose intrinsic properties were investigated, Fig. 3e). These cells were also scrutinized for KCC2 expression, utilizing combined immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 3f). Consonant with their electrophysiologically mature properties and hyperpolarizing GABAergic function, KCC2-positive INs also displayed mature morphological facets such as more complex dendritic arborization, than KCC2-negative INs. Scholl analysis revealed that KCC2-expressing INs had greater number of intersections at every distance from the soma. KCC2-positive INs displayed variations in their morphologies, including multipolar, local arbor, and bitufted dendrons. (Fig. 3g).

Despite arbor variations, KCC2-positive INs had significantly larger branch lengths and significantly higher total dendritic lengths, with an average total dendritic length of 2000μm. The dendritic lengths strongly correlated with maximal firing frequencies (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Fig 1d). These results confirm that KCC2 positive interneurons have a markedly mature profile that reflects in various features of their morpho-physiology.

Early KCC2 expression is a reliable marker of mature phenotypes in perinatal INs

Having confirmed the precocious morpho-electrophysiological characteristics of KCC2-expressing interneurons in SIBF layer 5, we then set out to investigate expression of IN markers in our electrophysiologically recorded INs. To further characterize the IN populations expressing Kcc2 at birth, we first analyzed a scNRA-seq dataset at P019. The highest expression of the Kcc2 (Slc12A5) was seen in the interneuronal cluster 2, in IN cluster 3, and in IN cluster 1. Sst (somatostatin), Npy (neuropeptide Y), and Calb1 (calbindin 1) were expressed by the same IN populations expressing Kcc2, while there was little or no expression of Kcc2 in Calb2 (calbindin 2) expressing cell populations (Supplementary Fig 2a, b). These data provided us with directions for our consequent single cell patch-transcriptomic analysis.

Utilizing cytoplasmic mRNAs that were collected during electrophysiological recordings, we conducted post-hoc single-cell qPCR (Fig. 4a), selecting the genes that were highly co-expressed in the data set from Loo et al.19 (Sst, Npy, Calb1, Gad1, Supplementary Fig. 2). All cells were GAD2-positive INs from layer 5 of the SIBF. Each of the cells was obtained in concert with gramicidin or whole-cell recordings (Fig. 4b).

a Graphical illustration of electrode placement and protocols for brain slice electrophysiological recordings and post hoc single cell transcriptomics in layer 5 INs of SIBF (b). Quantification of normalized relative expression of interneuron (IN) markers (Npy, Calb1, Gad1,Sst and Kcc2) in single cells obtained along with perforated patch recordings of GABA reversal and whole cell current clamp recordings; n = 110 GAD2+ INs. Expression levels of markers were normalized to house-keeping gene Tuba1. c Quantification of percentages of cells expressing the markers and divided into Kcc2+ and Kcc2- cells. d Quantification of positive and negative expression of markers in all cells, divided into Kcc2+ and Kcc2− groups (n = 66 Kcc2+ and n = 44 Kcc2-). e Pie chart quantifications showing percentage of Kcc2-positive cells within each IN-marker subgroup f Quantification of firing frequencies across IN groups and with Kcc2+ and Kcc2− subpopulations in each group. n = 57 INs, 6 animals. n = 33, 23, 15 for Sst+, Npy+ and Calb1+ INs respectively. **p = 0.0014 and ****p < 0.0001. One-way ANOVA, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, unpaired two-tailed t-test, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, respectively. g Quantification of GABAergic driving force across IN groups and with Kcc2+ and Kcc2− subpopulations in each group. n = 48 INs, 7 animals. n = 29,24,19 for Sst+, Npy+ and Calb1+ INs, respectively. ****p < 0.0001, ***p = 0.0002, **p = 0,0089,*p = 0.0498; two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, and unpaired two-tailed t tests, respectively. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM in all plots. Source data are provided as a Source data file. Panel a created in BioRender. Srinivasan, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ltjsbei See Supplementary data 10 for detailed statistics.

The single-cell qPCR analysis of electrophysiologically recorded GAD2-expressing INs revealed that Sst-expressing INs were the largest population. We noted that 57.2%, 51.8%, 43.6% and 30.9% expressed Sst, Gad1, Npy, and Calb1, respectively (Fig. 4b, c). Interestingly, two or more of the markers were co-expressed in many of the INs (38.1%, 18.1%, and 5.4% expressed 2, 3, and 4 markers, respectively) (Fig. 4d).

From the whole recorded population, 60% of the recorded neurons of layer 5 Gad2-positive INs had Kcc2 expression (Fig. 4d, e), and 72.7% of the recorded cells that were Kcc2-positive also expressed Sst. Sst-positive cells had the largest proportion of Kcc2-positive cells. (Fig. 4c–e). Sst-positive cells also formed only a small population of Kcc2-negative INs (34.09%, Fig. 4c). While 77.04% of Sst-positive cells were Kcc2-positive, 62.5% of Npy-positive cells and 58.8% of Calb1-positive cells had Kcc2 expression (Fig. 4e). These results ratify Sst as a pivotal marker expressed in the IN population with early maturation trajectories. Moreover, they also point to Npy and Calb1 as important markers expressed in these precocious populations.

Kcc2 expression was closely associated with higher firing frequencies and more mature electrophysiological properties in our dataset. Kcc2 expression robustly distinguished interneurons with significantly higher maximal firing frequencies within each IN-marker group (Fig. 4f), whereas no significant differences were observed between the IN-marker groups themselves.

Gramicidin recordings further revealed that GABAergic driving forces were significantly higher in Sst-expressing INs compared to Calb1-positive INs. Moreover, within each IN-marker group, Kcc2 expression defined a subpopulation with significantly higher GABAergic driving forces (Fig. 4g). These results highlight Kcc2 as a robust molecular correlate of advanced electrophysiological maturation, including both firing propensity and GABAergic polarity. Hence, Kcc2 expression in this context serves as a reliable marker of functional maturation, identifying interneuron subtypes that are primed for earlier electrophysiological development.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomic analyses reveal discrete interneuronal populations with high-level Kcc2 (Slc12a5) expression at birth

Having observed early KCC2 expression in interneurons at embryonic stages, functional KCC2 expression at birth, and co-expression patterns with IN markers, we set out to investigate Kcc2-expressing neuronal populations in greater detail through scRNA-seq data analyses. Utilizing a high-resolution cortical development bioinformatic atlas of somatosensory cortex development31, we tracked expression patterns of Kcc2 in discrete neuronal populations through the course of development from embryonic day 11.5 to adulthood.

We scrutinized absolute Kcc2 expression across the 27 main neuronal populations of the cortex (Fig. 5a) and through 12 time points encompassing the course of neurodevelopment from embryonic stages to adulthood: E11.5, E12.5, E13.5, E14.5, E15.5, E16.5, E17.5, E18.5, P0, P2, P5, and adult (P60+). The analysis with this bioinformatic atlas clarified the classes and families of the cells expressing Kcc2, in a developmental stage-wise manner. Clarifying morphologies and stratal locations (Fig. 5a), we examined Kcc2 expression. Notably, Kcc2 was highly expressed at birth, in several distinct interneuronal populations, paralleling expression levels seen during adulthood (Fig. 5b). Harmonizing with our immunohistochemical experiments, high-level Kcc2 expression was seen in INs of the somatosensory cortex, including INs of layer 5 and 6 of the cortex at birth (P0). Four subtypes of somatostatin-expressing (Sst) INs had the highest Kcc2 expression. This included prospective layer 5 T-Martinotti and layer 2–5 fanning Martinotti, Sst-positive non-Martinotti cells, and Sst layer 4 innervating cells (Fig. 5b). This also corroborated our preceding single cell patch-transcriptomic results, where a major population of Kcc2+ INs co-expressed Sst.

a Above: Sankey plot depicting scheme of neuronal families of Glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons comprised in the single cell analyses. 27 sub types of neurons and INs were present in the data set. Below: Cortico-stratal positions and schematic morphologies of discrete Glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons comprised in the single cell analyses. b Above: Graphical illustration of mice in embryonic, postnatal, adolescent, and late adult stages, depicting the whole course of development. Below: Heatmap quantifying absolute expression levels of Kcc2 gene Slc12a5 across 27 cortical neuronal populations, including glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons. The expression of Kcc2 gene Slc12a5 is tracked through 12 time points from embryogenesis to adulthood: E11.5, E12.5, E13.5, E14.5, E15.5, E16.5, E17.5, E18.5, P0, P2, P5, and adult (P60+). Prominent expression of Slc12a5, matching adult levels, is seen in four-layer 5/6 SST positive IN populations at birth on postnatal day 0 (T-Martinotti, Fanning Martinotti, Non-Martinotti, and Innervating cell) derived from single cell sequencing analysis utilizing a powerful bioinformatic atlas. Panel b inset created in BioRender. Srinivasan, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ac2n1el.

Prospective deeper-layer fast-spiking (FS)-like Sst INs and Sst Chodl also had high Kcc2 expression at P0. Moreover, one subtype of future Parvalbumin (Pv)- positive fast-spiking cells of layers 5 and 6 had appreciable Kcc2 expression at birth (P0) (Fig. 5b). Thus, these bioinformatic analyses provide crucial information defining classes, stratal positions, and prospective morphologies of the cell population expressing Kcc2 at embryonic and perinatal stages. These data corroborate all our preceding immunohistochemical, morphological, spatial, and single-cell transcriptomic data analyses, using independent and external datasets in the bioinformatic atlas.

Focusing on a single data set, we next conducted a detailed scRNA-seq data analysis of embryonic and perinatal (P0-P1) INs (Fig. 6a), from the dataset18 of Di Bella and colleagues. Unsupervised clustering of the gene expression profiles of INs formed 9 clusters based on dimensionality reduction with the most variable genes in the data (see methods). Cells were clustered by sample (which is confounded with age) and cell type, based on the gene expression levels (Fig. 6b). Kcc2 was expressed in a subset of E18 and P1 INs in clusters 0, 3, and 5. (Fig. 6c, d). Particularly, interneurons of cluster 0 had the largest fraction of INs that showed high expression of Kcc2, and were predominantly Sst positive (Fig. 6c–e). This was consistent with the early expression of KCC2 in a sub population of interneurons indicated by the immunohistochemical experiments in E18 embryonic cortices, and furthermore with our preceding analyses using the bioinformatic atlas.

a UMAP plot depicting the time points of sample origin in the analyzed data set. We utilized data sets of embryonic day 13–18 and post-natal day 1. b UMAP plot of IN clusters found in the data set (c). Dot plot quantifications of enrichment of Kcc2 (Slc12a5), Sst, Npy, Calb, Gad1, Gad2, Dlx2, Htr3a, Lhx6, Nxph1, Nxph2, Pax6, Sp8, Cxcl14, and Meis2. d UMAP plot depicting Kcc2 gene Slc12a5 enrichment in IN populations. e Similar UMAP plots depicting gene enrichments of Sst, Npy, Calb1, Gad1, Gad2, and Htr3a in IN populations. Total INs in UMAPs: n = 4785. DEG analysis was done in Kcc2 expressing IN clusters, n = 4 animals, with 2579 cells (see “methods” and Supplementary Data for details), of which 242 were Kcc2 positive and 2337 Kcc2 negative. f Upset plot illustrating the intersection sizes among Kcc2-positive cells expressing canonical interneuron marker genes (Gad1, Gad2, Sst, Npy, Calb1, and Htr3a) in the perinatal cortex. Horizontal bars (right) show the total number of Kcc2-positive cells expressing each marker gene (set size). Vertical bars (top) indicate the size of each intersection, i.e., the number of Kcc2-positive cells co-expressing the indicated combination(s) of marker genes (highlighted by filled dots below each bar). The largest intersection corresponds to Kcc2-positive cells co-expressing Gad1 and Gad2, with additional subsets defined by co-expression with Sst, Npy, Calb1, and Htr3a. Table below plot showing the fold difference (observed/expected) and Bonferroni-adjusted p values (P.adj bonferroni) for the enrichment of canonical interneuron marker genes (Sst, Npy, Calb1, Gad1, Gad2, and Htr3a) among Kcc2-positive cells. Positive values indicate over-representation, while negative values indicate under-representation relative to expectation. Statistically significant enrichment or depletion (P.adj < 0.05) is observed for Sst, Npy, Calb1, Gad1, and Htr3a, highlighting distinct molecular profiles within the early-maturing Kcc2-positive interneuron population. g Quantification of percentages of co-expression of Kcc2 in INs expressing discrete markers. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Furthermore, this analysis also confirmed that Sst, Npy, and Calb1 (Fig. 6c–e) to be the pivotal IN markers that are co-expressed in Kcc2-expressing INs, validating our preceding single-cell-patch-transcriptomic results, through a completely independent scRNA-seq data set. We examined the correlated expression of these markers and found that Sst and Npy were co-expressed in several subsets of Kcc2-positive INs (Fig. 6f) and showed the highest level of co-expression in comparison to other markers that were co-expressed. The smallest populations of Kcc2-positive INs showed co-expression of Htr3a +Npy, and Sst + Npy (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig 5a, correlation coefficient statistics in table below Fig. 6f).

Of the Kcc2-positive perinatal INs 50.5% were also Sst-positive in these early stages, and 53.3% and 16.1% of Kcc2-positive INs were Npy- and Calb1-positive, respectively. Of Kcc2-expressing perinatal INs, 54.1% and 51.7% were Gad1- and Gad2-positive. Only 1.7% of the cells expressing Kcc2 had Htr3a expression, confirming that these cells were predominantly not Htr3a INs (Fig. 6c, e–g).

The identities, maturation trajectories, and future fates of cortical INs are linked to their origin, and they arise either from the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE), caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE), or preoptic areas (POA)68,69,70. Most early-rising interneuronal populations originate in the MGE, including SST-positive interneurons59,71,72,73,74,75. To elucidate the origin of INs that express Kcc2 perinatally, we examined the expression of canonical marker genes characteristic of MGE and CGE derived INs. The Majority of Kcc2-positive perinatal INs also expressed genes typical of MGE INs, including Lhx6 (72.7%), Nxph1 (79.8%), and a third expressed Nxph2 (29.8%), suggesting that Kcc2-positive INs primarily arise from the MGE. Along with Gad1 and Gad2, 59.1% Kcc2-positive perinatal INs also expressed Dlx2, suggesting that they are ventrally generated MGE-INs (Supplementary Fig 3a). By contrast, only 0.4%, 0.8%, and 0.4% of Kcc2-positive INs expressed Pax6, Sp8, and Cxcl14, typical of CGE-derived INs. A small population of 5.8% and 6.6% of Kcc2-positive INs expressed Etv1 and Meis2, suggesting that Kcc2 is expressed in the minor subpopulation arising from CGE (Supplementary Fig 3b, c). We examined the correlated expression of these MGE and CGE genes in Kcc2-positive INs, revealing that Nxph1 and Lhx6 were co-expressed in several subpopulations of Kcc2-positive cells and showed the highest level of co-expression in comparison to other markers that were co-expressed (Supplementary Fig 3d). These results point to MGE being the major origin of Kcc2-positive perinatal INs, and consequently, that they are early-generated.

To further corroborate these findings in a layer specific manner, we conducted RNA-scope in situ hybridization. Since other interneuron markers such as PV and VIP emerge only at later postnatal stages, we focused on examining the co-expression of Gad1, Gad2, and Sst with Kcc2, using this method to track their mRNA expression. Using cortical slices of P0 animals, we examined the expression of these markers in the somatosensory barrel field cortex (SIBF) (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Here we set out to clarify the laminar distribution of Kcc2-positive interneurons, and Kcc2-expressing Sst subpopulation of these interneurons.

We confirmed, also through mRNA expression, that Kcc2 was predominantly expressed only in interneurons, across all layers. (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c). We found that layer 5 had the highest density of Gad1/2-expressing INs, and furthermore, the highest density and percentage of Kcc2-expressing INs, and Sst INs (Supplementary Fig. 4b-d). This layer also had the highest percentage of Sst-expressing Kcc2-positive INs, noted by Sst-Kcc2 colocalization. (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

Early Kcc2/Slc12a5-expressing INs display upregulation of a multitude of genes promoting synaptogenesis, synaptic signaling and maturation

After identifying the markers most significantly co-expressed in Kcc2-positive INs through single cell patch-transcriptomics and scRNA-seq data analysis, we set forth to have a deeper understanding of the genetic profile of this population and the mechanisms linked to their distinct trajectories. To this end, we proceeded with anatomizing the IN population that we identified in the scRNA-seq dataset from Bella et al.18 that expresses Kcc2 in late embryonic and perinatal stages (E18-P1).

To further genetically distinguish Kcc2-positive INs from those that do not express Kcc2 in perinatal stages, we performed differential gene expression (DGE) analysis in the INs belonging to the same subclusters, as depicted earlier (Fig. 6a). Intriguingly, 99.48% of differentially expressed genes (DEGs, 385 out of 387 genes) were upregulated in Kcc2-positive INs compared to Kcc2-negative INs (adjusted P < 0.05, absolute fold change >1.5, Fig. 7a and Supplementary data 1). We tracked the expression patterns of the 50 most significantly expressed genes across pre- and perinatal stages E13, E14, E15, E16, E18, and P1, revealing a steady increase in their expression through the course of embryonic to perinatal development. Expression of these genes plateaued between E18-P1 (Supplementary Fig 5a).

a Volcano plot showing significance (\(-{\log }_{10}\) adjusted P-value) and fold change (\({\log }_{2}\) Fold Change) of gene expression between Kcc2-positive and Kcc2-negative cells. Differentially expressed genes (adjusted P value < 0.05, \({{{\rm{| }}}}{{{\rm{FC}}}}{{{\rm{| }}}} > 1.5\)) are colored in red; the most highly upregulated synaptic genes and the downregulated Sox4 gene are labelled. DEGs between clusters were detected using Seurat::FindMarkers() (two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test) with Benjamini–Hochberg correction. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment shows significant over-representation of DEGs in key Biological Processes (b) and Cellular Components (c) in Kcc2+ perinatal INs, consistent with high connectivity and synaptic maturity. X-axes show Gene Ratio (DEGs annotated to a term divided by all genes annotated to term). The first 15 terms from clusterProfiler output plotted. Overrepresentation of DEGs was assessed with one-sided hypergeometric test and Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment of p values for multiple comparisons. d SynGO sunburst plots show significant enrichment of synaptic processes and components. The plot is hierarchical: central tile is “Synapse”; surrounding tiles are daughter terms following GO hierarchy. Colored tiles are significant, grey tiles indicate terms with no or too few genes to reach significance. For b–d, over-representation of DEGs in GO or SynGO terms was tested with one-sided hypergeometric tests with Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment for multiple comparisons. e Protocol for voltage-clamp recordings combined with single patch-transcriptomics. Quantification of miniature and spontaneous excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic current (mEPSC, mIPSC, sEPSC, sIPSC) frequencies and amplitudes in KCC2+ and KCC2− INs (minis: n = 9 KCC2+ and n = 11 KCC2− INs from 3 animals; spontaneous: n = 14 KCC2+ and n = 18 KCC2− INs from 3 animals). *p < 0.05, **p = 0.0076, ****p < 0.0001, two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, and unpaired two-tailed t-tests. Please see Supplementary Data 1–3 for DGE, GO, and SynGO gene lists. Data are presented as mean ± SEM in plots in (e). Source data are provided as a Source data file. Panel e inset created with BioRender (Srinivasan, R., 2025) https://BioRender.com/9568ubu.

The DGE analysis revealed only two genes downregulated (Sox4 and Gm17750) in Kcc2-positive INs (Fig. 7a and Supplementary data 1). Of these Sox4 was most significantly downregulated, negatively correlating with Kcc2 in a “dose-dependent” manner (Supplementary Fig 4c). These findings suggest that the pro-maturation signal associated with Kcc2 may be regulated by Sox4 expression, providing further insight into the genetic mechanisms molding fates of this distinct IN population.

Consequently, to investigate whether the differentially expressed genes highlighted any specific biological functions, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis. The analyses revealed enrichment to terms associated with synaptic functions related to synaptic signaling and synapse organization (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Data 2) in the Kcc2-positive IN population. In line with our morphology analyses, Kcc2-expressing INs had upregulated genes with functions in neuron connectivity (Fig. 7c, d and Supplementary Data 2). Furthermore, Kcc2-positive INs had an upregulation of genes corresponding to synaptic cellular components and cellular apparatuses aiding signaling functions, in comparison to Kcc2-negative peers. (Fig. 7c).

To elucidate if any specific synaptic processes were associated with Kcc2-positive INs, we analyzed overrepresentation for the synaptic GO (SynGO) terms76 (Fig. 7d; Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Fig 5b). Conjointly, these analyses emphasize that Kcc2-positive INs are a unique subpopulation underpinned by pronounced synaptic functions, cell-cell contact, maturity, and concomitant genetic programs.

Early KCC2-expressing perinatal interneurons display markedly higher synaptic input dynamics

Having confirmed profound upregulation of synaptic-function-related genes in Kcc2/Slc12a5-expressing INs, we next set out to examine whether this was functionally reflected in synaptic inputs to KCC2-expressing INs. Synaptic inputs to interneurons at birth and early post-natal stages are not well characterized; while very few studies examine interneuron-specific synaptic input dynamics only after p5-p758,59. Therefore, we systematically examined both excitatory and inhibitory inputs to KCC2-expressing INs in action-potential-independent and dependent contexts, to clarify synaptic connectivity and network implications of these INs at birth, and till postnatal day 2.

Conducting whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings, we investigated excitatory glutamatergic and inhibitory GABAergic inputs and then collected their somas for post-hoc single-cell transcriptomic analysis of KCC2 expression (Fig. 7e). We first examined action potential-independent synaptic activity by recording miniature excitatory and inhibitory post synaptic currents (mEPSCs and mIPSCs), in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX). KCC2-expressing INs displayed markedly higher frequencies of both mEPSCs and mIPSCs than KCC2-negative INs, suggesting an increase in the number of synaptic contacts and elevated probability of spontaneous vesicle release at individual synapses. Furthermore, KCC2-positive INs also displayed significantly higher mEPSC and mIPSC amplitudes than KCC2-negative INs, indicating possibly an increased number/faster postsynaptic receptors, and larger quantal sizes (Fig. 7e).

Voltage-clamp recordings of action-potential-dependent spontaneous excitatory and inhibitory post synaptic currents (sEPSCs and sIPSCs) revealed that KCC2-positive INs had significantly higher frequencies of both sEPSCs and sIPSCs than KCC2-negative INs, and furthermore higher sEPSC and sIPSC amplitudes (Fig. 7e). This indicates that they are highly engaged within their network, acting as major integrators of synaptic input. Conjointly, these reveal that KCC2-positive INs receive significantly higher number of synaptic contacts and have a mature, highly connected state capable of robust synaptic signaling already at these very early stages.

Early KCC2/ SLC12A5-expressing INs are identifiable in human embryonic brains and display analogous upregulation of a host of genes promoting synaptogenesis and maturation

While several studies have documented pathological downregulation of KCC2 in human disorders such as epilepsy and neurodevelopmental conditions77,78,79,80,81,82,83, investigations into its physiological expression patterns in healthy human brains remain very sparse29,30. This gap highlights the need for systematic mapping of KCC2 distribution across developmental stages in non-pathological human tissue, and more specifically, identifying expression patterns across discrete neuronal populations to understand varying maturation trajectories. Furthermore, insight into the induction of KCC2 expression, resolving cell-type-specific patterns in early and prenatal human cortico-development, is crucial to understanding neurodevelopmental etiologies.

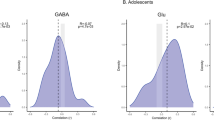

To examine interneuronal KCC2 expression in early human cortical development, we utilized a comprehensive single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (sn-RNA-seq) atlas based on prenatal, non-pathological human encephalic samples of gestational weeks (GW) 17 to 41 from Ramos et al.32. We investigated if an identical population of early KCC2-expressing INs, identified in the mouse cortex, is present in the human prenatal cortex. We analyzed stages GW 17–38 using this human sn-RNA-seq atlas to provide a comprehensive overview of KCC2 expression during fetal cortical development. Notably, the GW 17–24 window corresponds to the mouse developmental stage from E18 to P38, facilitating cross-species comparison84,85,86. A non-supervised clustering of gene expression resulted in 19 clusters of INs, and INs were defined from cell annotations in the metadata of Ramos et al.32 KCC2 expression commenced as early as GW 17 in a small number of INs and marked KCC2 expression in INs began after GW 20, and the number of clusters (cell type complexity) increased over GWs (Fig. 8a). The expression of KCC2 progressively increased from GW 17 to 38 without plateauing, exhibiting a statistically significant positive correlation (correlation = 0.1650, p = 3.80 × 10⁻⁹), indicative of a prolonged developmental trajectory (Fig. 8b).

a UMAP plots depict prenatal human interneuron (IN) clusters from single-nucleus RNA-seq data across gestational weeks (GW) 17–38, sample origin and KCC2 (SLC12A5) enrichment (INs in UMAPs: n = 16,625). b. Quantification reveals a progressive, significant increase in KCC2 expression across GW 17–38 (correlation = 0.1650, p = 3.80 × 10⁻⁹). Box plots show 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile; whiskers extend to ≥ 1st quartile − 1.5× IQR and ≤3rd quartile +1.5 × IQR. The red line indicates linear regression. KCC2+ INs: n = 1259 (19.6% of 6426 INs). Per-GW IN counts: GW17 n = 7, GW18 n = 14, GW19 n = 5, GW20 n = 46, GW21 n = 204, GW22 n = 52, GW23 n = 37, GW24 n = 45, GW25 n = 113, GW26 n = 104, GW33 n = 464, GW38 n = 168. Human embryonic brains per GW: N = 1, except GW20, 26, 33 (N = 2). c Dot plots quantify enrichment of KCC2, SST, NPY, CALB1, GAD1, GAD2, DLX2, HTR3A, LHX6, NXPH1, NXPH2, PAX6, SP8, CXCL14 and MEIS2. d UMAP plots show SST, NPY, CALB1, GAD1, GAD2 and HTR3A enrichment in INs and the fraction of KCC2+ INs co-expressing each marker. e UMAP plot marks clusters selected for differential gene expression (DGE), Gene Ontology (GO), and SynGO analyses, with a Venn diagram of conserved DEGs. f Left: Volcano plot compares KCC2+ and KCC2− cells, highlighting significant DEGs (adjusted p < 0.05, |fold change| > 1.5), including upregulated synaptic genes and downregulated Sox4. Right: SynGO sunburst plot shows hierarchical enrichment of synaptic components; only colored tiles are significant. DEGs were identified with a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Benjamini–Hochberg correction. g GO analysis shows DEGs enriched in biological processes and cellular components linked to connectivity and synaptic maturity in KCC2+ INs; Gene Ratio indicates the proportion of annotated DEGs. The top 15 terms are shown. Supplementary Data 4–8 provide detailed results.

Next, to further dissect the identities of early KCC2-expressing human INs, we examined co-expression of IN markers SST, NPY, CALB1, GAD1, GAD2, and HTR3, as scrutinized previously in mice RNA-seq data (Fig. 8c, d). We identified that a small subpopulation of the KCC2-positive INs showed significant co-expression of SST (17.03%) and was relatively bigger than subpopulations expressing other markers, including NPY (4.00%) and CALB1(5.25%) (Fig. 8a, c, d). Notably, marker co-expression was less pronounced than in mouse perinatal INs, suggesting greater heterogeneity in human prenatal KCC2+ INs.

Complementary lineage analysis revealed that, like mice Kcc2-positive INs, the human KCC2 positive cells expressed marker genes characteristic of MGE INs (NXPH1 [79.5%], NXPH2 [34.6%], and LHX6 [52.9%]) (Fig. 8c, d). We examined correlated expressions of all these genes in KCC2+ INs and KCC2- INs and found only GAD1 & GAD2 to be heavily co-expressed with KCC2, followed by SST and CALB1 in a small subset of cells (Supplementary Fig 6b, c and Supplementary data 9 for correlation coefficients).

To better understand how KCC2-positive INs differed from the rest of INs, we performed differential gene expression analysis. We compared the KCC2-positive cells from week 25 to 38, with the most robust KCC2 expression, and KCC2-negative INs from the same time points (clusters 7, 11, 9, 2, 19, 0, 14, 5 and 18) (Fig. 8e). Remarkably, and consistent with patterns in perinatal mice cortices, 492 DEGs from the total 496 DEGs showed a positive fold change, corresponding to 99.19% of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that were upregulated in KCC2-positive prenatal human INs compared to KCC2-negative INs. (Fig. 8f and Supplementary Data 4). Twenty-five genes were common in the DEGs of human and mouse analyses from a total of 883 genes of both species (Fig. 8e, genes listed in Supplementary Data 5), and this overlap was not significant (p = 0.487, Odds ratio: 0.838, Fisher’s Exact Test).

Subsequently, to inspect whether the DEGs highlighted any specific biological processes, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis. Similar to mouse data analysis, to clarify if any specific synaptic processes were associated with KCC2-positive INs, we analyzed overrepresentation for the synaptic GO (SynGO) terms76 (Fig. 8f and Supplementary Data 6), revealing higher gene counts for several synaptic functions and components. Analogous to previous mice data analyses, the analyses revealed enrichment of an array of terms associated with signaling and synaptic functions (Fig. 8f, g and Supplementary Data 7) in the KCC2-positive IN population. Furthermore, genes related to cellular components were upregulated and GO term enrichment analyses revealed enrichment of an array of terms associated with cell projection and synaptic components (Fig. 8g and Supplementary Data 8). In concert, these data indicated that KCC2-positive INs have highly upregulated signaling, intercellular communication, and synaptic functions in comparison to KCC2-negative IN peers. Furthermore, they possess more synaptic cellular components and cellular apparatuses that aid signaling functions.

We tracked expression patterns of the 50 most significantly expressed genes across GWs 17–38 (Supplementary Fig. 7). Unlike the mouse DEGs, which showed plateauing expression, human DEGs exhibited dynamic temporal patterns. Together with the sustained increase in KCC2 expression, these findings suggest a prolonged neurodevelopmental trajectory in humans87,88,89,90,91.

The prenatal human DGE analysis revealed that Sox-4, interestingly, was one of the downregulated genes in KCC2-positive human prenatal INs, confirming the relevance of the repression of this gene as the pro-maturation signal associated with KCC2, consistent with mice data (Fig. 8f). Collectively, these data indicate that this population of early KCC2-expressing INs are identifiable in human prenatal cortices, and hence, remarkably, that this population is evolutionarily conserved across mice and human embryonic cortices. The combined analyses highlight that this population of INs is early maturing; underpinned by prominent signaling functions, cell-cell contact, and concomitant cellular apparatuses regulated by specialized genetic programs noted specifically in these INs.

Discussion

Untangling early circuit dynamics and neurodevelopment requires accurate distinguishment of neuronal populations at embryonic and perinatal stages, and knowledge of their maturation trajectories. The distinct features of cortical interneuronal populations are poorly characterized at the perinatal phase, despite the colossal work done to classify neuronal populations further in development. Consequently, there is a chasm in the knowledge about how rudimentary integration is possible in perinatal circuitry, and how complex activity then begins to emerge.

The GABAergic interneuronal population in its entirety has been revealed to pioneer cortical development, arising days before that of their glutamatergic principal neurons, in the subpallium, from the ephemeral structures of the medial and caudal ganglionic eminences (MGE, CGE), and from the pre-optic area73,74,92,93,94,95,96,97. INs have been postulated to be collectively more mature than principal neurons, in any given network and developmental milestone97. Early-rising and maturing populations arise from the MGE, while late-rising populations emerge from CGE59,98,99,100,101,102,103. In our work, using a combination of data sets and paradigms, we show that KCC2 is expressed prominently as early as embryonic day 18 in a unique neocortical subpopulation, mainly in the deeper cortical strata and subplate-proximal populations. This constitutes the earliest-rising IN populations, while late-rising INs occupy the marginal zone and outermost cortical strata104,105,106,107,108,109. Our findings align with existing literature on the role of KCC2 in the termination of migration37.

Furthermore, by clarifying the expression of MGE genes (Lhx6, Nxph1, and Nxph2) and CGE genes (Pax6, Sp8, and Cxcl14), we confirm that this population is MGE-derived. Additionally, previous literature has shown that early-rising INs predominantly express SST73,110,111,112,113,114. Our study’s sc-RNA-seq analyses from atlases, data sets, and analyses of our spatial and sc-transcriptomics confirm that Kcc2-positive perinatal INs are largely SST-positive. Thus, though we do not have birth dating experiments for these INs, the cortico-stratal location and gene expression profiles of KCC2-expressing perinatal INs indicate that they constitute an early-rising IN population.

Apart from being among the earliest-rising population, SST-positive INs mature faster other interneuronal populations103,115,116 and regulate cortical circuit development and dynamics at early postnatal stages59,102,117,118,119. Through scRNA-seq data and sc-transcriptomics analyses we further characterized the markers associated with Kcc2 expressing perinatal IN population. We identify a vast majority of them to be Sst-expressing INs, while some of them additionally or exclusively express Npy or Calb1. Via analysis with the mouse cortex bioinformatic atlas, we further deconstructed the Sst populations, revealing four subtypes of somatostatin-expressing INs (L5 T-Martinotti, L 2-5 fanning Martinotti, non-Martinotti cells, and Sst L4 Innervating cells) with high Kcc2 expression at birth.

GABAergic polarity is known to be depolarizing in early postnatal stages22,23,24,25,26,27,28,31. Though there have been studies highlighting variations in KCC2 expression and GABAergic polarity shift timing in different brain regions28,120,121,122,123, KCC2 function-dependent timing of the shift in perinatal INs has not been explored. Previous research has noted a disparity between GABAergic reversal potentials between INs and principal neurons later in development124,125,126,127,128; yet whether the timing of the developmental shift in polarity of GABAergic responses varies between glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons has thus far been unknown. Furthermore, there have only been speculations on the GABAergic polarity of perinatal early-rising INs that are network integrators, based on observations later in development97.

Here, we show KCC2 function-dependent hyperpolarizing GABAergic responses in perinatal cortical INs. Our investigations on the polarity of GABAergic responses at birth and perinatal stages accentuate the marked difference in KCC2 expression-dependent GABAergic function between INs and principal neurons. The KCC2-positive IN population has a median estimated intracellular chloride of 12 mM at and around birth, while principal cells have an estimated intracellular Cl- concentration of 32 mM, indicative of an immature state as shown in previous research, ranging from 25 to 40 mM120,129,130,131,132.

After verifying their hyperpolarizing GABAergic function, we further revealed a host of their precocious morpho-physiological features, from high intrinsic excitability, relatively mature firing phenotypes, and action potential kinetics, to extensive dendritic arborization. In comparison to KCC2-negative INs, KCC2-expressing INs have lower input resistance, lower rheobases, smaller AP half-widths, much higher firing frequencies, and larger AHP amplitudes. All of these are previously established hallmarks of interneuronal maturity65,66 and, furthermore, noted in also in early-maturing INs59,97. Morphologically, KCC2-positive INs showed large, complex dendritic arbors and diverse morphologies, including multipolar, local arbor, and bitufted dendrons, whereas KCC2-negative INs had sparse dendritic development at birth. KCC2’s role in cytoskeletal regulation likely contributes to the morphological maturity of KCC2-positive interneurons38,133.

Our DGE, GO, and SynGO analyses reveal that these early rising and maturing perinatal Kcc2-positive INs have a multitude of upregulated genes that are implicated in synaptogenesis, synaptic function, cell-cell contact, and maturity. Firstly, strikingly, there are almost exclusively 385 upregulated genes in Kcc2-positive INs vs Kcc2-negative INs at E18-P1, as revealed by the DGE analysis. This is highly unlikely by chance alone, suggesting that Kcc2 expression is associated with the induction of an array of gene programs in these INs. The upregulated genes (including Grin3, Synp3, Snca, and Map1b) are implicated in a myriad of synaptic functions, signaling, system processes, synapse organization, and associative learning134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142. Genes associated with cellular components, including those determining neuronal and cellular projection, were also upregulated in Kcc2 INs, corroborating our morphological investigation.

Consistent with this gene expression, we report functional evidence for their high connectivity. KCC2-expressing interneurons (INs) exhibit significantly elevated frequencies and amplitudes of both miniature and spontaneous excitatory (mEPSCs, sEPSCs) and inhibitory (mIPSCs, sIPSCs) postsynaptic currents compared to KCC2-negative INs, indicating a higher number of synaptic contacts and greater postsynaptic responsiveness. Intriguingly, the mEPSC and sEPSC frequencies of KCC2+ INs were 2–5-fold higher than what is documented of other postnatal INs in the first week59,143,144,145. These results suggest that KCC2-positive INs are highly connected and integrated within their local circuits, possibly aiding information processing at perinatal stages, when other INs show rudimentary synaptic functions. KCC2 is a crucial orchestrator of maturation and function of glutamatergic synapses, including the regulation of AMPA receptor trafficking and long-term synaptic plasticity38,146. KCC2 has veritable roles in both GABAergic and glutamatergic signaling; in supporting robust signaling and integration, and its ablation diminishes the efficacy of excitatory synaptic transmission38,146,147,148. Thus, KCC2 expression could play a crucial role in the marked synaptogenic properties of this population of INs, as noted in other studies133.

From the two genes that were downregulated in the Kcc2-positive INs, Sox4 was significantly downregulated, suggesting that Sox4 may be silenced in Kcc2-positive INs. This is noteworthy, given that Sox4 is highly expressed in early cortical development, and its previously elucidated roles include regulation of maturation of oligodendrocytes149,150,151,152,153. Based on our analyses, it may be hypothesized that Sox4 downregulation could be essential for the maturation of Kcc2+ INs and could provide a mechanistic insight into what elicits Kcc2 expression in this population. However, further studies are necessary to verify this.

Most crucially, leveraging a human prenatal cortical atlas, we identified a population of early KCC2-expressing interneurons (INs) as early as gestational weeks (GW) 17–20. Consistent with findings from mouse studies, these early human KCC2+ INs displayed robust expression of medial ganglionic eminence (MGE)–associated genes, indicating that they early-born.

Remarkably, and analogous to mouse Kcc2+ INs, human KCC2+ INs displayed exclusive upregulation of 492 DEGs. 25 of the genes were commonly upregulated in both mice and humans, including SDC3, TSPAN7, PCDH17, NPAS4, SPON1, EFNA3, SYNGR3, RAB3B, and DOC2A; and these play a host of roles in synaptic functions such as synaptogenesis, spine formation, synaptic plasticity, specificity, vesicle trafficking, and neurotransmitter release154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163. Our GO and SynGO analyses confirmed that a host of upregulated genes are implicated in cell-cell signaling, synaptic functions, cell-cell contact, and morphophysiological maturity. Genes implicated in neuronal survival, migration, differentiation, neurite growth, and axon guidance were also upregulated in both mice and human KCC2+ INs, including TMEM132C, TPPP3, IGFBP3, and RBMS1164,165,166,167. Human prenatal KCC2+ INs also displayed downregulation of SOX4, emphasizing the possible regulatory role of this gene in eliciting KCC2 expression induction. Hence, the early KCC2-expressing interneuron population is evidently evolutionarily conserved, sharing analogous genetic, molecular, and synaptogenic features that underscore a conserved functional role across species.

Given the precocious morpho-physiological properties, distinct GABAergic function, synaptogenic gene expression profiles, and elevated synaptic activity and integration, we propose that early KCC2-expressing INs are in the front line of interneuronal maturation trajectories. With their robust synaptic signaling they possibly hold the propensity for aiding computational demands of the somatosensory cortex, which is among the first, if not the first, to receive sensory stimuli168,169,170.

Previous reports have identified similar interneuron populations at later postnatal stages that play roles in transient cortico-circuit structures and dynamics prevalent during the first weeks59,171. However, perinatal circuit formation remains poorly understood, and the mature neuronal features observed in our study have not been previously documented. Additionally, our spatial transcriptomics localize their majority to layer 5, further alluding to a distinctive role, given the layer’s distinctive roles in cortical output and input control42. We postulate that they would be viable etiological targets in neurodevelopment conditions with aberrant early connectivity172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179; while their genetic signature may be leveraged for diagnostic biomarkers. While interneurons are cardinal in network synchronization180,181,182, those with complex dendritic morphologies, high intrinsic excitability, and connectivity are known to be nodes in information flow in circuits102, and neuronal synchronizers59,97,99,100,102,183,184. Hence, the gene expression profile and markedly higher synaptic signaling of KCC2+ INs, along with their mature morpho-physiology may imply a role in emergence of neuronal synchrony. Hyperpolarizing GABA, noted in our population, is also known to hold a role in the emergence of synchronous activity185. Our current work opens a future avenue for investigating the role of this population in the emergence of synchrony.

Reliable markers of distinct perinatal populations are a dire necessity, given that many IN markers that distinguish adult INs are either co-expressed or absent75,186,187,188,189,190 in perinatal stages. Past studies show that INs participating in postnatal transient cortico-circuit structures express heterogeneous markers59,102,171. Here, we demonstrate that the cation chloride co-transporter KCC2 is reliable as a marker to selectively and precisely capture an early-rising and maturing population that plays a pivotal role in early synaptic dynamics during the perinatal period. The cation-chloride transporter KCC2 is no new player in the context of neuronal maturation, with decades of research attesting its myriad roles in this milieu. As an orchestrator of various phenomena, including GABAergic inhibition, neuronal migration, apoptosis, electrophysiological phenotype, synaptic plasticity, and spine genesis, KCC2 plays an indubitable role in the development of neuronal entities38,191. Our data reveal a previously unrecognized role for KCC2 in orchestrating perinatal interneuron maturation: paving the way to comprehending early cortico-development and concomitant aberrations.

Methods

Animal models

All mice were Mus musculus on a C57BL/6J-based background and were bred and maintained in-house. Experiments were conducted using embryonic or postnatal mice of embryonic day 18 or between postnatal day (P) 0–2 from mouse lines with fluorescent reporters in GAD2 expressing INs. GAD2-Cre line (JAX 010802) mice were crossed with Ai14 (JAX 007914) to produce GAD2-TdTomato mice; GAD2-Cre mice were crossed with GCamp6flox line mice (JAX 028865) to produce GAD2-GCamp mice. In this study, all mice used were of C57BL/6J background, and the experiments were done in accordance with University of Helsinki Animal Welfare Guidelines and were approved by the Animal Experiment Board in Finland, and the following animal licenses were used: KEK23-009, ESAVI/3183/2022.

Sex

Sex steroid hormone levels are minimal and largely equivalent in male and female rodents during the embryonic day 18 (E18) to postnatal day 2 (P2) timeframe examined in this study. At these early developmental stages, the gonads are largely inactive or produce only very low levels of sex steroids, significantly limiting the potential for sex hormone-driven biological differences to influence interneuron development56,192,193. Key cortical developmental processes such as interneuron migration, specification, and synaptogenesis are predominantly regulated by intrinsic genetic programs and environmental factors rather than by sex steroids within this narrow embryonic to early postnatal window56,192,194,195,196,197. Importantly, we did take measures to consider sex in this study in the major experiments examining GABAergic polarity and function (n = 5 animals per sex) and neuronal excitability (n = 3 animals per sex). These experiments included both male and female rodents with adequate sample sizes, which revealed no significant sex differences (reported in Source data file, and statistics in Supplementary Data 10). Consequently, succeeding experiments (such as pharmacological manipulations, morphological investigation) with smaller sample sizes included only males to reduce animal use while maintaining scientific rigor.

Mice lines used/crossed

Ai95D, RCL-GCaMP6f (JAX 028865), Gad2-IRES-Cre (JAX 010802), Ai14 (JAX 007914).

Immunohistochemistry at light and electron microscopic levels

Immunohistochemistry was performed at light microscopic level (LM) and pre-embedding immunogold electron microscopy (EM) on brains fixed by immersion (E18) for 48 h or by intracardiac perfusion starting at P0. Mice were deeply anaesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane and intracardially perfused with a mixture of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% of glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. Brains were dissected out, postfixed for 4 h in the same fixative solution, and stored in PBS. They were coronally cut with a Vibratome in two different thicknesses: 50 mm, for LM, or 120 mm, for EM. Selected sections were processed for floating immunocytochemistry. Sections were first treated for quenching with NH4Cl 0,05 M in PBS for 20 min, then incubated for 2 h, at room temperature, with a mixture of 2.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) with 2.5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS. They were incubated for 12 h–72 h (for LM) or 48 h (for EM) at 4 °C with the anti-KCC2 antibody (rabbit; dilution 1/1000; US Biological, Euromedex, France) and layer 5 principal neuron marker CTIP2 (1:2000) diluted in PBS with BSA 0.5% and NGS 0.5%. For light immunohistochemistry, the sections, after rinsing in PBS, were incubated with the fluorescent-labeled secondary antibody for 1–2 h at room temperature. Controls were performed by omitting the first antibody. Sections were finally analyzed using a Zeiss (Wetzlar, Germany) confocal microscope and the complementary software package.

For immunogold electron microscopy, after the primary KCC2 antibody (produced by us, and previously published198), sections were post-fixed for 5 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with the secondary 0.8 nm gold antibody (goat anti-rabbit, Aurion, France), diluted 1/30 in PBS with 1% BSA. The next day, after a PBS-positive BSA rinse, sections were post-fixed 5 min with 1% glutaraldehyde before a silver enhancement (Aurion) for 1 h 30. Then, they were osmicated in OsO4, dehydrated in graded alcohol, and flat-embedded in Epon resin. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) of the selected areas were dissected with an Ultracut microtome and visualized with a Zeiss electron microscope.

Immunohistochemistry for CTIP2-KCC2 stainings at P0

GAD2-Gcamp mice from postnatal day 0 (p0) were deeply anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital and lidocaine, and transcardially perfused with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Brains were dissected out, postfixed for 5h in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS, and immersed in 30% sucrose solution until the brains floated to the surface. Brains were embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound and frozen on dry ice. Fifty micrometer free-floating coronal cryosections were prepared with Leica CM3050 S cryostat. Sections were washed in 0.1 M PBS for 5 min and 2 * 10 min, quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 20 min, blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin, 3% goat serum, 0.4% Tx-100 in PBS, and incubated with anti-KCC2 (rabbit; dilution 1:2000; Millipore 07-432), anti-CTIP2 (rat; dilution 1:2000; Abcam ab18465), anti-GFP (chicken; 1:2000; Aveslabs GFP-1010) in 1% bovine serum albumin, 1% goat serum, 0.4% Tx-100 in PBS for three consecutive nights (60–72 h) at +4 °C. The sections were washed in 0.3% Tx-100 in PBS for 2 * 5 min, 4 * 10min, 8 * 15 min, incubated with Cy5 (goat-anti-rabbit; dilution 1:400, Molecular Probes A10523), Alexa Fluor 555 (goat-anti-rat; dilution 1:400; Molecular Probes A21434), Alexa Fluor 488 (goat-anti-chicken; dilution 1:400; Invitrogen A11039) in 1% bovine serum albumin, 1% goat serum, 0.4% Tx-100 in PBS for 2h at room temperature, washed in 0.3% Tx-100 in PBS for 2 * 5 min, 4 * 10 min, 4 * 15 min and counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (concentration 1 µg/ml; Cell Signaling #4082) in 0.3% Tx-100 in PBS for 20 min. The sections were mounted on glass slides and coverslipped with Fluoromount G mounting medium. The sections were imaged with Zeiss LSM980 confocal microscope (C-Apochromat 40×/1.20 W Korr objective) and Zen Blue (version 3.5.093.00010).

List of antibodies

-

Ctip2 Abcam ab18465

-

KCC2 Millipore 07-432

-

GFP Aveslabs GFP-1010

-

Cy5 Molecular Probes A10523

-

Alexa Fluor 488 Invitrogen A11039

-

Alexa Fluor 555 Molecular Probes A21434

Workflow for analysis of membrane-like expression of KCC2

Tissue collection and processing

On the day of birth mouse pups (Gad2-Cre (+/-); GCaMP6f-flox (+/-)) were deeply anaesthetized with pentobarbital and lidocain, and transcardially perfused with room temperature PBS. Brains were extracted and fixed by immersing them in 4% PFA for 3–5 h, after which they were placed in 30% sucrose solution at +4 °C for a couple of days until they sank to the bottom of the tube. Brains were embedded in O.C.T. compound, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C until cryosectioning. Fifty-micrometer-thick free-floating coronal cryosections were prepared and stored at −20 °C in a cryoprotectant solution until proceeding with the immunostaining.

Immunostaining