Abstract

The superconducting symmetry of Sr2RuO4 has been intensely debated for many years. A crucial controversy recently emerged between shear-mode ultrasound experiments, which suggest a two-component order parameter, and some uniaxial pressure experiments that suggest a one-component order parameter. To resolve this controversy, we use a new approach to directly apply three different kinds of shear strain to single crystals of Sr2RuO4 and investigate the coupling to superconductivity. After characterising the strain by optical imaging, we observe variations of the transition temperature Tc smaller than 10 mK%−1 as measured by low-frequency magnetic susceptibility, indicating that shear strain has little to no coupling to superconductivity. Our results are consistent with a one-component order parameter model, but such a model cannot consistently explain other experimental evidence such as time-reversal symmetry breaking, superconducting domains, and horizontal line nodes, thus calling for alternative interpretations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Strains in a crystal have well-defined irreducible representations (irreps) under the symmetry of a lattice. Strains are precisely coupled to the superconducting (SC) order parameter (OP) according to their symmetries, and induce changes in Tc. Thus, the application of strains to a superconductor and the observation of the changes in Tc is a precise method of gaining information on the SC OP. In addition to isotropic hydrostatic pressure, it has recently become clear that uniaxial strains are a powerful tool to investigate superconducting symmetry, since they can profoundly alter crystal symmetry1,2,3.

The OP of unconventional superconductivity in Sr2RuO44 is still unresolved despite 30 years of extensive research efforts5,6. Spin-singlet-like behaviour was newly established from spin susceptibility measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)7,8,9 and polarised neutrons10. Time-reversal symmetry breaking (TRSB), evidenced by an emerging internal magnetic field below Tc11, has been reported by several groups12,13,14. Magneto-optic Kerr effect (MOKE) also supports the presence of TRSB in the superconducting state15. Anomalous switching behaviour in superconducting junctions16 points to the presence of SC domains characterised by a multi-component OP with one-dimensional (1D) or 2D irreducible representations (irreps).

Uniaxial compression in Sr2RuO4 enhances Tc from 1.5 to 3.5 K, and it is associated with changes in the Fermi surface topology (Lifshitz transition)2,17. A splitting between Tc and appearance of the TRSB phase was observed by muon spin relaxation (μSR) under uniaxial strain14, pointing to a chiral superconducting OP. However, the splitting is not observed in specific heat and elastocaloric-effect measurements under uniaxial strain18,19, leaving the issue of TRSB unsettled at present.

Another peculiar behaviour of Sr2RuO4 is the jump at Tc of the shear-mode ultrasound velocity related to the elastic modulus c6620,21. This unusual coupling between SC OP and shear strain implies that the OP has two components: either chiral with 2D irreps (e.g., dyz ± idzx), nematic with 2D irreps (e.g., dyz only, dzx only, or dyz ± dzx), or a combination of 1D irreps (e.g., d + ig, s + id). Results of uniaxial stress and hydrostatic pressure experiments can be combined to compare with results from ultrasound experiments22, but such comparison leads to both qualitative and quantitative discrepancies6. Specifically, a V-shaped kink in Tc as a function of uniaxial strain along the [110] direction was not observed, in contrast with the expectations from the observed jump in the ultrasound c66. It is crucial to resolve this discrepancy in order to reach a conclusion about the superconducting state of Sr2RuO4.

In this study, we investigate the direct effect of shear strain on the Tc of Sr2RuO4. The magnitude of sample strains at low temperatures is measured with optical imaging down to 30 K. Kinks, linear slopes, and quadratic changes in Tc are evaluated by applying three different kinds of shear strain and comparing the results with the estimates of the Ehrenfest relations from the jumps and slope changes of the elastic-moduli at Tc. We find that Tc does not change within the experimental precision of ∂Tc/∂εxy = ± 6 mK%−1. This result seriously challenges the interpretation of SC in Sr2RuO4 in terms of a two-component OP.

Results

Direct shear-strain quantification at low temperature

To apply shear strain, we construct piezo-sample assemblies by rigidly gluing thinly polished Sr2RuO4 crystals directly onto the surface of piezoelectric devices, as shown in Fig. 1a (see “Methods” for construction details). Deformation of a piezo-sample assembly is monitored by an optical microscope, which allows us to calculate the point-by-point in-plane displacements (ux, uy) and the in-plane shear strain εxy = (∂ux/∂y + ∂uy/∂x)/2. We note that this definition is symmetric (εxy = εyx) and that εxy = γxy/2 = ε6/2, where γxy is the engineering strain and ε6 is the xy shear strain in Voigt notation. We show in Fig. 1b a typical optical image taken at room temperature with a voltage applied to the shear piezo Vpiezo = + 200 V. By means of digital image correlation23,24, we extract the point-by-point displacements that are represented by the coloured dots. As indicated by the arrows, the bottom of the piezo-sample assembly is moving to the right (red) while the top is moving to the left (blue) due to the applied shear strain. We note that the piezoelectric device we use predominantly generates a shear displacement component ∂ux/∂y, while the complementary component ∂uy/∂x is small due to the device’s geometry and boundary constraints (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information). We comment on the importance of measuring both components because relaxation of shear strain could lead to insurgence of a negative ∂uy/∂x at the sample surface, which corresponds to an overall sample rotation (Fig. S2).

a Photo of a thin Sr2RuO4 crystal (dimensions 0.8 × 0.5 × 0.03 mm3, sample S4) attached onto the active side surface of a shear piezo device (dimensions 2.2 × 0.5 × 2.2 mm3) and corresponding schematics. b Optical microscope image of the Sr2RuO4 sample (black) on the shear piezo surface with 200 V applied at room temperature. The point-by-point horizontal displacement ux is represented by the coloured dots, while the arrows schematically indicate the in-plane shear strain. c Direct optical measurement of shear strain on the piezo device (crosses) and Sr2RuO4 (circles) at two selected temperatures. d Magnitude of shear at 100 V and e amount of shear transferred to the Sr2RuO4 sample as a function of temperature. The dashed lines are polynomial guides to the eye.

We calculate the average shear strain over the surface of the piezo device and the Sr2RuO4 sample as a function of Vpiezo in Fig. 1c. At room temperature, the piezo device can apply a maximum of about εxy = ± 0.05% at Vpiezo = ± 200 V, corresponding to a shear strain transferred to the Sr2RuO4 of about εxy = ± 0.04%. We emphasize the advantage of this optical technique, which enables non-contact measurement of the effective shear strain directly on the sample surface, allowing us to estimate the shear strain transferred to the bulk of the sample and to neglect the uncertainty due to glue-mediated strain transfer from the piezoelectric device. The shear–voltage characteristics in Fig. 1c are nearly linear, with a small hysteresis that is typical of piezoelectric actuators25. While this hysteresis is generally negligible for the purposes of this study, it introduces an uncertainty in the shear strain that is most significant around zero applied voltage, where the upper bound estimated from the vertical width of the hysteresis is δεxy ≈ 0.02%. Importantly, this uncertainty is minimal at the largest applied voltages, where the strain response is well defined and reproducible. As shown in Fig. 1d, the shear applied at a certain voltage becomes gradually smaller at lower temperature due to the decreasing capacitance of the piezoelectric device (Fig. S3). We compensate for this effect by applying a larger voltage to the piezo device at low temperature, thus achieving similar values of maximum shear strain at all temperatures.

We show in Fig. 1e that the strain transferred from the piezoelectric device to the Sr2RuO4 sample is as large as 75% at lower temperature, where a weak enhancement is possibly caused by a stiffening of the glue used to attach the sample to the piezo surface. This strain transfer is consistent with the value predicted by our finite element simulations (Fig. S2) for samples of 30 μm thickness. A direct correlation between the travel distance of the piezoelectric device and its capacitance (Fig. S3) allows us to calculate a conversion factor εxy/Vpiezo = 0.007%/100V at 2 K. Because the samples investigated in this study have similar thicknesses, we found this conversion factor to be approximately constant.

Response of T c to shear strain

We now consider changes in Tc by shear strain. To detect the superconducting transition, we insert the piezo-sample assembly of Fig. 1a into the mutual-inductance coil set shown in Fig. 2a. The mutual-inductance technique allows us to measure the imaginary χ′′ and real \({\chi }^{{\prime} }\) parts of the alternating current (AC) susceptibility extracted from the in-phase and out-of-phase lock-in voltages Vx, Vy, respectively. These are measured as a function of temperature for different applied voltages Vpiezo in Fig. 2b, c. We use Sr2RuO4 samples with a sharp superconducting transition that appears as a dissipation peak in χ′′, with full width at half maximum of about 20 mK, and as a drop in \({\chi }^{{\prime} }\) that indicates the onset of diamagnetic susceptibility, with a transition width smaller than 40 mK. We compare in Fig. 2d two possible criteria for defining Tc: from the position of the peak in χ′′ (squares), and from the mid-point of the drop in \({\chi }^{{\prime} }\) (dots). We comment that both criteria allow us to overcome time-dependent changes in the electronic signal, which suffers from small voltage offsets over time. The values of Tc resulting from the two criteria show consistent trends, with a minor difference in absolute value. Since the peak in χ′′ is about an order of magnitude smaller than the drop in \({\chi }^{{\prime} }\), the latter provides a more reliable criterion across different samples and will be used to determine Tc throughout this work.

a Assembly of shear piezo and Sr2RuO4 sample, attached on a bamboo holder with copper wires, to be inserted into a mutual-inductance coil set for measuring AC susceptibility. (b) Imaginary and (c) real parts of the AC susceptibility measured by the mutual-inductance method (sample S5, shear [110]). The colours represent the chronological order in which the measurements were taken, as indicated by the colourscale in (d). The Tc is detected by two different criteria: fitting a Lorentzian peak (dotted vertical line in (b)) or a sigmoid function (dashed vertical line in (c)). d Resulting changes in Tc as a function of voltage applied to the shear piezo: from the peak maximum in χ′′ (squares) and from the mid-point of the drop in \({\chi }^{{\prime} }\) (circles). We use filled (open) symbols to indicate points taken with increasing (decreasing) voltage. e Changes in Tc with shear strain applied along the [100], f [110], and g [001] crystalline directions of Sr2RuO4 using several piezo-sample assemblies. The schematics above each panel indicate the corresponding shear deformation of the Sr2RuO4 lattice. A linear regression is performed on each data set to illustrate the variation of the small slopes. The grey shaded regions, marked by the black arrows, indicate confidence intervals chosen to represent the scattering of the data of ± 0.6, ± 0.9, and ± 0.6 mK, respectively.

Using several piezo-sample assemblies with Sr2RuO4 glued along different crystalline axes, we apply continuous shear strains along the three directions shown in Fig. 2e to g: a pure εxy shear along the [100], a diagonal shear \({\varepsilon }_{{x}^{{\prime} }{y}^{{\prime} }}^{110}={\varepsilon }_{xx}-{\varepsilon }_{yy}\) along the [110], and a c-axis shear εzx along the [001]. As shown in the insets above the panels, these correspond to B2g, B1g, and Eg strain modes, respectively. We use several samples from at least two different batches of crystals for the measurements. In contrast to ultrasound experiments where the response of Sr2RuO4 to shear modes was measured with strains oscillating at high frequencies, our technique allows us to apply static shear strains across the whole dynamic range of the piezoelectric device. Due to the C4z rotational symmetry of the lattice, a positive and a negative shear are expected to yield identical results [i.e., ΔTc(εxy) = ΔTc( − εxy)], hence a symmetric trend is expected around εxy = 0. The data in Fig. 2e to g show no change of Tc within our experimental resolution for all three kinds of applied shear strain, with neither a kink nor a quadratic trend. We estimate upper limits of a purely linear slope of the kind ∂Tc/∂ε by drawing grey shaded regions that correspond to Tc variations smaller than ± 6, ± 9, and ± 6 mK%−1, respectively. Based on the same shaded regions, upper limits for purely quadratic slopes ∂2Tc/∂ε2 are estimated to be ± 60, ± 90, and ± 60 mK%−2. These values will be further discussed in the following and compared with thermodynamic predictions from ultrasound experiments in Table 1.

We now consider the possible effect of thermally-induced pre-strains in Sr2RuO4 due to the difference in thermal contraction with the piezoelectric device. As we show in Fig. S4, an Sr2RuO4 sample glued along the ab plane is affected by a biaxial tensile pre-strain up to about + 0.1 to + 0.3%. For a [100] piezo-sample assembly, this pre-strain can be seen as a combination of compressive A1g and shear B1g strain modes. In such configuration, the voltage-driven shear-piezo device applies a pure B2g strain, a shear mode that is not present in the pre-strain. Therefore, the Tc variations that we investigated provide direct information of the SC coupling to a specific shear mode.

Tensile control experiment

To validate our technique of detecting small Tc changes with strain, we perform a similar experiment with a uniaxial tensile piezo. As shown in Fig. 3, tensile strain applied to Sr2RuO4 induces a clear Tc change in the range of several mK (see Fig. S5 for a voltage-to-strain conversion and Fig. S6 for extended data). As indicated by the fitted curve (black dashed line), the strain-dependence of Tc follows a quadratic behaviour. This quadratic trend is consistent with that reported by Watson et al.26, although our minimum is not at Δεxx = 0. A likely cause of this shift is the presence of pre-strains caused by the differential thermal contraction of Sr2RuO4 and the piezoelectric device27. We discuss in Fig. S4 that for an assembly of Sr2RuO4 glued over the active surface of a tensile piezo there is a biaxial pre-strain up to about + 0.1 to + 0.3%, which is reasonably consistent with the value of + 0.1% extracted from the fit in Fig. 3. Although it is difficult to extract quantitative results from this control experiment with tensile strain, it proves that the technique used in this work is suitable to capture the smallest variations of Tc.

Variations of Tc measured by mutual inductance with an assembly of a tensile piezoelectric device and an Sr2RuO4 sample. A quadratic dependence on uniaxial strain is observed, with a minimum at Δεxx ~ + 0.1% that indicates presence of pre-strains. To compare the Tc resolution with the shear data, the grey shaded region indicates an interval of ± 0.6 mK.

Discussion

Our results show that the Tc of Sr2RuO4 does not change under the direct application of shear strains εxy, \({\varepsilon }_{{x}^{{\prime} }{y}^{{\prime} }}^{110}\), and εzx. This is different from the Tc variations that occur under compressive strains. In the following, we compare our results with the prediction of shear-strain response estimated by combining the results of uniaxial compressions and hydrostatic pressure. We also examine the limit of compatibility with the jumps in ultrasound velocities at Tc and with the change in their slope. Finally, we compare with the jumps in thermal expansion at Tc.

Comparison with uniaxial stress and ultrasound experiments

In Table 1 (left columns), we give some of the irreducible representations (irrep) of the D4h point group that apply to space group I4/mmm of Sr2RuO4 crystal structure. The couplings between different strains and superconductivity are dictated by symmetry. Due to the C4z rotational symmetry, the Tc variation under shear is expected to be symmetric and show either a linear kink for a two-component SC or a quadratic dependence for a one-component SC. For the two-component order parameter η = (ηx, ηy) that belongs to Eg irrep with components {dxz, dyz}, the Ginzburg-Landau (GL) free energy density that describes the coupling to lattice strain is given by (more details in the Supplementary Information)

up to second order in ηx, ηy and first order in strain, with constant coupling parameters ri28. The D4h symmetry does not allow linear coupling to strains εyz and εzx of irrep Eg and modulus c44, so to lowest order these strains should not affect Tc. For a nematic or chiral OP, we have

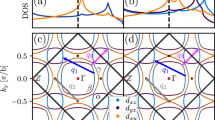

indicating that application of pure shear strains B2g or B1g is expected to lead to a kink in Tc around ε = 0. We show again with a grey confidence interval in Fig. 4 that our experiment proves little to no coupling to εxy.

Our experimental data from Fig. 2e are shown as circles, while the grey shaded region marked by the black arrows indicates our confidence interval for the lack of a kink or a quadratic strain dependence. The green solid line shows the kink required by the symmetry, with the slope estimated combining stress experiments from refs. 22,29,30 via Eq. (3). The V-shaped kinks shown by the blue and red dashed lines are estimated from the c66 ultrasound jump at Tc20,21 via the 1st order Ehrenfest relation. The dotted red line shows the quadratic slope calculated via the 2nd order Ehrenfest relation from the c66 slope change at Tc21.

We now compare our direct measurement of shear strain with estimates from other techniques where shear strain was indirectly applied along other strains. By combining the results of other stress–strain experiments (details in the Supplementary Information and Table S1) as

where \({\sigma }_{{x}^{{\prime} }{x}^{{\prime} }}^{110}\) is the uniaxial compression along the [110] direction, σzz is uniaxial compression along the z axis, and the hydrostatic pressure phydro is positive for compression (opposite sign compared to the σi). By using c66 = 65.5 GPa21 and values of the three slopes + 71 mk GPa−122, − 210 mk GPa−1 29, and + 76 mk GPa−1 30, respectively, we obtain ∂Tc/∂εxy ~ 10.5 mK%−1, which is shown by the green V-shaped line in Fig. 4. This estimate is consistent with the one provided by Jerzembeck et al. \(| \partial {T}_{c}/\partial {\varepsilon }_{xy}| < 13\,mK{\%}^{-1}\)[ 22.

Interestingly, we observe no measurable change in Tc under \({\varepsilon }_{{x}^{{\prime} }{y}^{{\prime} }}^{110}\), which corresponds to pure B1g shear strain (Fig. 2f). This seems in contrast to previous uniaxial stress studies along [100], where an increase in Tc was reported and attributed to the B1g symmetry channel31. In those works, the strain state includes a combination of symmetry components due to the Poisson effect, with variation of both B1g and A1g strains. By contrast, our setup applies a pure B1g shear strain, with constant A1g strain. Furthermore, the strain magnitude in our experiment is smaller, such that the Fermi surface remains far from the van Hove singularity. At present, the absence of a Tc response under pure B1g strain remains an open question, but it highlights the complexity of how different strain symmetries couple to the superconducting state.

In addition, we compare our results with estimates from the thermodynamic Ehrenfest relations

where Δcij is the jump in elastic moduli at Tc and ΔC ~ 570 J m−3K−1 21 is the jump in specific heat, with f(βk) a function of the 4th order GL free energy coefficients βk28. Here, the coefficients f(βk) are parameters that can be estimated in the weak-coupling limit under the isotropic-band approximation28, yielding the equations and estimates presented in the central columns of Table 1. As shown in Fig. 4, the V-shaped kinks estimated from Ehrenfest relations have a much larger slope than our direct measurement. It should be noted that discrepancies are also serious for the A1g compressional modes (c11 + c12)/2 and c33: the Tc variations under constant stress are both about a factor five smaller than the expectation from the compressional-mode ultrasound jumps6. Thus, we find here an inconsistency with the Ehrenfest relations, which has to be resolved.

Finally, we consider the upper limit for quadratic variation in Tc found in this study (grey regions of Fig. 2e to g) and compare it with estimates from second order Ehrenfest relations that depend on the slope jump of elastic moduli at Tc (right columns of Table 1)28. While the quadratic term estimated from c66 is rather small, the one from (c11 − c12)/2 is very large. It is rather puzzling that a second-order coupling is so large in the absence of the first-order coupling. Such discrepancy in both shear and compressional modes suggests that the ultrasound response may contain additional contributions not given by the coupling to the SC OP. In the normal state of Sr2RuO4, the elastic moduli c11 and (c11 − c12)/2 are known to exhibit a peculiar temperature dependence compared to the other modes32. These modes involve stretching and shrinking of the in-plane Ru-O bond lengths that may cause additional coupling to the quasiparticles, although it is not clear how such coupling changes below Tc.

Comparison with thermal expansion

Another thermodynamic comparison can be made with jumps in thermal expansion coefficient αi = ∂εii/∂T using the different Ehrenfest relation

where C is the specific heat, and Δ refers to the jumps at Tc. Note that, unlike Eq. (4) for elastic moduli, which involves elastic couplings to the superconducting order-parameter in the free energy, this Ehrenfest relation is a more direct thermodynamic requirement. From the negative jumps Δαa = − 0.42 × 10−7 K−1 and Δαc = − 0.52 × 10−7 K−1 observed by Grube et al.33, we obtain ∂Tc/∂phydro = − 360 mk GPa−1 and ∂Tc/∂σzz = + 140 mk GPa−1. These estimates are within a factor two in agreement with the results of hydrostatic pressure − 210 mk GPa−1 29 and c-axis uniaxial-stress + 76 mk GPa−1 30. Thus, the strong disagreements of ultrasound jumps in both shear and compression modes suggest that the ultrasound jumps may contain additional contributions which are not properly included in the Ehrenfest relation of Eq. (4).

To conclude, we investigated the coupling of Sr2RuO4 superconductivity to shear strain. For this purpose, we developed a technique where thin sample crystals were glued on shear-strain piezoelectric devices that allowed us to directly apply static shear strains along three symmetry channels. The magnitudes of strains were evaluated from optical imaging down to 30 K. We found no detectable change of Tc, with a resolution limit smaller than 10 mK%−1. This poses strict limits on the possible nature of the superconducting order parameter, pointing at ruling out a two-component order parameter. We note, however, that there remains an unresolved discrepancy between the results of ultrasound and static deformation (stress/strain) experiments, which requires further investigation. Our analysis indicates that Sr2RuO4 has a one-component OP, or it is a host of more exotic OPs that are required to fully explain its superconducting state. The new method developed in this study can be readily applied to other superconductors for which a two-component OP is suggested, such as UPt3, or to other materials showing different kinds of phase transitions where a two-component order parameter may emerge.

Methods

Piezo-sample assemblies and sample crystals

In order to apply various shear strains to Sr2RuO4 samples, we used a shear piezoelectric device (Thorlabs, PL5FB) consisting of a single piezoelectric ceramic layer of PbZrxTi1−xO3 (PZT) with gold-plated electrodes on the top and bottom surfaces. The device provides a free-stroke displacement of 1.3 μm with the application of ± 200 V at room temperature. We cut the commercial 5 × 5 × 0.5 mm3 shear devices into four pieces of about 2 × 2 × 0.5 mm3 with a diamond-disc cutter, and polished the cut planes using a polishing machine (Musashino Denshi, MA-200) with a diamond slurry of 3 μm. We left a suitable surface roughness to secure strong adhesion to the sample crystal and to provide a clear optical contrast for measuring actual strain. For the control experiment, we used a tensile strain device (Thorlabs, PA3CE, dimension 2 × 2 × 2 mm3) consisting of piezoelectric layers stacked in series. The device provides a free-stroke expansion displacement of 2 μm with the application of + 100 V at room temperature.

The Sr2RuO4 single crystals used in this study were grown by a floating-zone method using an image furnace (Canon Machinery, SC-E15HD)34. The cystal orientation was determined by X-ray Laue patterns (Rigaku, RASCO BL-II with a CCD camera). We selected Sr2RuO4 crystals with a sharp superconducting transition at Tc = 1.5 K, ensuring the absence of metallic-Ru inclusions that would induce broad enhancement of Tc up to 3.5 K35. The Sr2RuO4 crystals were cut into a typical size of 0.4 × 1 mm2 and polished down to a thickness of 30 ± 5 μm with a diamond slurry of 3 μm. Each thin crystalline sample was glued to the active side surface of a piezo device with epoxy (EPO-TEK, 353ND) cured at 110–120 °C for 20 min. The lap shear of EPO-TEK 353ND (13.5 MPa) is much larger than the typical lap shear of other low-temperature epoxy, such as Stycast 2850FT (3 MPa, with catalyst 24LV), ensuring good adhesion between the Sr2RuO4 and the piezo element.

High-voltage electrodes for the piezo elements were provided by copper wires (diameter 0.14 mm) attached using silver paste (EPO-TEK, H20E) cured at 120 °C for 2 h. For SC measurements, each piezo-sample assembly was mounted on a bamboo holder on which ten insulated copper wires (diameter 0.1 mm) were used for thermal anchoring, glued with varnish (GE, 8530) as shown in Fig. 2a.

Image correlation to optically measure the strains

We employed an optical-imaging technique to quantify the shear and tensile strain applied by the piezoelectric devices to Sr2RuO4 samples. Digital photographs were taken with different Vpiezo using an optical microscope (MicroSupport, SS306) with 10–40 × zoom. Digital image correlation (DIC) with DICe software was employed to compute in-plane displacements in the x and y directions23,24. The average strain over the sample and piezo surfaces was calculated line-by-line averaging the displacement data, while the error was estimated from the standard deviation of the data.

Calibration of strain

The conversion factor from Vpiezo to shear εxy and uniaxial εxx was measured at different temperatures between 30 and 295 K in an optical cryostat (Thermalblock, custom design). Since the piezo displacement per unit volt depends on temperature, the capacitance of the piezo was used to bridge between the measurements at 30 K, lowest temperature accessible by our optical cryostat, and the measurements of Tc, which were performed at and below 2 K. The strain transfer ratio discussed in Fig. 1e was estimated on different samples and found to be rather constant among the several samples due to their comparable thicknesses.

Determination of T c

Evaluation of Tc with exceptionally high precision and accuracy was crucial in this study. We adopted alternating-current (AC) susceptibility measurements using a mutual-inductance coil set36 and a lock-in amplifier (Stanford Research Systems, SR830) to probe both the imaginary χ′′ and real \({\chi }^{{\prime} }\) parts of the AC susceptibility defined as \(\chi=\partial M/\partial H=-i{\chi }^{{\prime\prime} }+{\chi }^{{\prime} }\). By driving an alternating current of the form \({I}_{AC}(t)={I}_{0}\cos (2\pi ft)\) in the excitation coil, the resulting voltage in the pickup coil is \({V}_{AC}(t)=(1/\alpha ){V}_{sample}{I}_{0}f(-{\chi }^{{\prime\prime} }\cos (2\pi ft)+{\chi }^{{\prime} }\sin (2\pi ft))\), with α a constant related to the geometry of the coils, Vsample the sample volume, I0 the amplitude of the excitation current, and f its frequency37. The coil set consisted of a pair of in-series pick-up/reference coils (400 turns each, internal diameter 5 mm, length 5.5 mm, copper wires diameter 50 μm) wound in opposite directions, and an excitation coil (2400 turns, internal diameter 6.0 mm, length 36 mm, copper wires diameter 100 μm), producing a magnetic field of 84 μT mA−1. An alternating current (frequency 17.7 kHz, root mean squared amplitude of 1 mA) was sourced to the excitation coil using the voltage output of the lock-in amplifier and a series resistance of 10 kΩ. In-phase (Vx) and out-of-phase (Vy) lock-in components were calibrated at 2 K by considering the phase delay of the circuit involving only the excitation coil. Several values of current were tested to ensure that the effect of heating was below 1 mK near Tc. The sample temperature was measured with a thermometer (Lake Shore, Cernox CX-1030-SD-HT) mounted on the copper plate to which each piezo-sample assembly and mutual-inductance coil set were thermally anchored.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Hicks, C. W. et al. Strong increase of Tc of Sr2RuO4 under both tensile and compressive strain. Science 344, 283–285 (2014).

Steppke, A. et al. Strong peak in Tc of Sr2RuO4 under uniaxial pressure. Science 355, eaaf9398 (2017).

Hicks, C. W., Jerzembeck, F., Noad, H. M., Barber, M. E. & Mackenzie, A. P. Probing quantum materials with uniaxial stress. Ann. Rev. Condensed Matter Phys. 16, 417–442 (2025).

Maeno, Y. et al. Superconductivity in a layered perovskite without copper. Nature 372, 532 (1994).

Maeno, Y., Yonezawa, S. & Ramires, A. Still mystery after all these years—unconventional superconductivity of Sr2RuO4—. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 93, 062001 (2024).

Maeno, Y., Ikeda, A. & Mattoni, G. Thirty years of puzzling superconductivity in Sr2RuO4. Nat. Phys. 20, 1712–1718 (2024).

Pustogow, A. et al. Constraints on the superconducting order parameter in Sr2RuO4 from oxygen-17 nuclear magnetic resonance. Nature 574, 72–75 (2019).

Ishida, K., Manago, M., Kinjo, K. & Maeno, Y. Reduction of the 17O Knight shift in the superconducting state and the heat-up effect by NMR pulses on Sr2RuO4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 89, 034712 (2020).

Chronister, A. et al. Evidence for even parity unconventional superconductivity in Sr2RuO4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2025313118 (2021).

Petsch, A. et al. Reduction of the spin susceptibility in the superconducting state of Sr2RuO4 observed by polarized neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 217004 (2020).

Luke, G. M. et al. Time-reversal symmetry-breaking superconductivity in Sr2RuO4. Nature 394, 558–561 (1998).

Shiroka, T. et al. μSR studies of superconductivity in eutectically grown mixed ruthenates. Phys. Rev. B 85, 134527 (2012).

Higemoto, W., Koda, A., Kadono, R., Yoshida, Y. & Ōnuki, Y. Investigation of spontaneous magnetic field in spin-triplet superconductor Sr2RuO4. In Proc. International Symposium on Science Explored by Ultra Slow Muon (USM2013), 010202 https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSCP.2.010202 (2014).

Grinenko, V. et al. Split superconducting and time-reversal symmetry-breaking transitions in Sr2RuO4 under stress. Nat. Phys. 17, 748–754 (2021).

Xia, J., Maeno, Y., Beyersdorf, P. T., Fejer, M. & Kapitulnik, A. High resolution polar Kerr effect measurements of Sr2RuO4: evidence for broken time-reversal symmetry in the superconducting state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 167002 (2006).

Anwar, M. S. & Robinson, J. W. A review of electronic transport in superconducting Sr2RuO4 junctions. Coatings 11, 1110 (2021).

Sunko, V. et al. Direct observation of a uniaxial stress-driven Lifshitz transition in Sr2RuO4. npj Quantum Mater. 4, 46 (2019).

Li, Y.-S. et al. High-sensitivity heat-capacity measurements on Sr2RuO4 under uniaxial pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2020492118 (2021).

Li, Y.-S. et al. Elastocaloric determination of the phase diagram of Sr2RuO4. Nature 607, 276–280 (2022).

Benhabib, S. et al. Ultrasound evidence for a two-component superconducting order parameter in Sr2RuO4. Nat. Phys. 17, 194–198 (2021).

Ghosh, S. et al. Thermodynamic evidence for a two-component superconducting order parameter in Sr2RuO4. Nat. Phys. 17, 199–204 (2021).

Jerzembeck, F. et al. Tc and the elastocaloric effect of Sr2RuO4 under 〈110〉 uniaxial stress: No indications of transition splitting. Phys. Rev. B 110, 064514 (2024).

Schreier, H., Orteu, J.-J. & Sutton, M. A. Image correlation for shape, motion and deformation measurements: basic concepts, theory and applications. Image Correlation for Shape, Motion and Deformation Measurements https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-78747-3 (Springer, 2009).

McCormick, N. & Lord, J. Digital image correlation. Mater. Today 13, 52–54 (2010).

Damjanovic, D. Chapter 4 - Hysteresis in piezoelectric and ferroelectric materials. Sci. Hysteresis 3, 337–465 (2006).

Watson, C. A., Gibbs, A. S., Mackenzie, A. P., Hicks, C. W. & Moler, K. A. Micron-scale measurements of low anisotropic strain response of local Tc in Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. B 98, 094521 (2018).

Shapiro, M., Hristov, A., Palmstrom, J., Chu, J.-H. & Fisher, I. Measurement of the B1g and B2g components of the elastoresistivity tensor for tetragonal materials via transverse resistivity configurations. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 87 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4953334 (2016).

Sigrist, M. Ehrenfest relations for ultrasound absorption in Sr2RuO4. Prog. Theor. Phys. 107, 917–925 (2002).

Forsythe, D. et al. Evolution of Fermi-liquid interactions in Sr2RuO4 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 166402 (2002).

Jerzembeck, F. et al. The superconductivity of Sr2RuO4 under c-axis uniaxial stress. Nat. Commun. 13, 4596 (2022).

Barber, M. E. et al. Role of correlations in determining the Van Hove strain in Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. B 100, 245139 (2019).

Okuda, N., Suzuki, T., Mao, Z., Maeno, Y. & Fujita, T. Unconventional strain dependence of superconductivity in spin-triplet superconductor Sr2RuO4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 71, 1134–1139 (2002).

Grube, K. et al. The anomalous stress dependence of multiband superconductors: Sr2RuO4 compared with AFe2As2 (A= K, Rb, Cs). In Proc. 22nd International Conference on Magnetism (ICM 2024) https://publikationen.bibliothek.kit.edu/1000168112 (2024).

Bobowski, J. S. et al. Improved single-crystal growth of Sr2RuO4. Condens. Matter 4, 6 (2019).

Maeno, Y. et al. Enhancement of superconductivity of Sr2RuO4 to 3 K by embedded metallic microdomains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 3765 (1998).

Yonezawa, S., Higuchi, T., Sugimoto, Y., Sow, C. & Maeno, Y. Compact AC susceptometer for fast sample characterization down to 0.1 K. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 86 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4929871 (2015).

Nikolo, M. Superconductivity: a guide to alternating current susceptibility. Am. J. Phys. 63, 1 (1995).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank K. Grube, S. Kittaka, H. v. Löhneysen, and A. Ramires for useful information, H. Matsuki for his technical contribution, and N. Manca for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by JSPS Grant-in-Aids KAKENHI Nos. 22H01168, 23K22439, JP24H01659, JP24K17011, and 25K17346. G.M. acknowledges support from the Kyoto University Foundation, and Toyota Riken Scholar. T.J. acknowledges support as JSPS International Research Fellow (PE24047). S.P. and Y.M. acknowledge supported from the JST Sakura Science Exchange Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M. developed the imaging apparatus, performed the low-temperature measurements, and analysed the data; Y.M. conceived and supervised the project, and prepared the sample-piezo assemblies; T.J., S.P., J.B., and Y.M. prepared the Sr2RuO4 crystals; T.J., G.M., M.S., and A.I. discussed the theoretical modelling and comparison with the ultrasound data. G.M., T.J., and Y.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Sayak Ghosh, Olivier Gingras, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mattoni, G., Johnson, T., Ikeda, A. et al. Direct evidence for the absence of coupling between shear strain and superconductivity in Sr2RuO4. Nat Commun 17, 700 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67307-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67307-1