Abstract

An important yet often overlooked catalyst design consideration for electrochemical hydrogenation reactions is the hydrogen transfer route. This can occur either through the Eley-Rideal (ER) mechanism involving proton-coupled electron transfer from solvent water or the Langmuir-Hinshelwood (LH) mechanism using surface-adsorbed *H. Although this can significantly influence catalyst performance, there is a lack of clear guiding principles on how to control the relative contribution of each mechanism. Here we show how catalyst alloying can shift the balance between hydrogenation via the LH vs. ER mechanism. Specifically, we demonstrate this with a model system involving acetylene reduction to ethylene on a series of CuAu alloys of varying composition. Using H2O-D2O mixtures as the electrolyte, we elucidate how varying the Au content can steer hydrogenation towards the LH mechanism. This consumes *H, which lowers hydrogen evolution activity and boosts ethylene selectivity. Using this strategy, the optimal CuAu catalyst achieved an ethylene Faradaic efficiency of 90.90% at 400 mA cm−2 with a production rate of 22.61 mmol h−1 mgcat−1. Our findings illustrate how the hydrogenation pathway can be rationally tuned to control catalytic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The canonical guiding principle of electrocatalyst design often revolves around tuning adsorbate binding energies to minimize reaction energy barriers. This is best illustrated with the ‘textbook’ example of acidic hydrogen evolution, whereby the highest activity is achieved with a surface that binds *H neither too strongly nor too weakly1. This concept is known as the Sabatier principle and is often illustrated in the form of a ‘volcanic plot’ of activity versus binding energy2,3. Further expanding on this, seminal work by Norskov and co-workers demonstrated that the adsorption energies of related intermediates scale linearly with each other4,5,6. This scaling relationship represents a fundamental constraint that limits catalyst performance for more complicated reactions involving multiple intermediates.

There is, however, growing evidence that electrocatalytic reactions are much more complex and cannot be fully described by these concepts. For instance, interfacial electric fields affect adsorbate binding energies based on their individual polarizability and dipole moment, hence operate independently of scaling relations7,8,9. The adsorbate surface coverage can also be a crucial parameter, particularly for the oxygen reduction reaction, where *OH has been proposed to have a considerable impact on kinetics10,11,12. Hence, there is a need for a more complete understanding of the important factors that can dictate the activity of electrocatalytic reactions. This would significantly benefit the typically highly iterative process of electrocatalyst design and optimization.

An important but often overlooked consideration for electrocatalyst design is the hydrogen transfer route. This is relevant to a plethora of reactions such as CO2 reduction, biomass to fuel conversion and nitrogen reduction to ammonia13,14,15,16. Hydrogen transfer can occur through the Eley–Rideal (ER) mechanism, which involves proton-coupled electron transfer directly from solvent water: *CxHyOz + H2O + e− → *CxHy+1Oz + OH−. Alternatively, hydrogenation can also take place using surface-adsorbed *H via the Langmuir-Hinshelwood (LH) mechanism: *CxHyOz + *H → *CxHy+1Oz + *. Before this can occur, *H is first generated through the Volmer step: H2O + e− → *H + OH−. Although this can have a substantial impact on catalyst performance, in most cases, the contribution of each individual mechanism is completely unknown.

Our previous work shed light on the hydrogen transfer pathway in electrochemical CO2 reduction (CO2R) on Cu. By using H2O-D2O mixtures as the electrolyte, we found evidence that the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of the LH mechanism was considerably higher than the ER mechanism17. Specifically, the KIE of the ER mechanism was deduced using acetylene reduction to ethylene as a probe reaction. For the LH mechanism, we found that its KIE is largely due to the Volmer step, which we rationalized using classical collision theory. Through this framework, we estimated the H vs D transfer probabilities of each pathway and found that the predominant hydrogenation route in CO2R is through the LH mechanism.

With these insights, we were motivated to investigate how electrocatalysts can be rationally designed to control the balance between each hydrogenation pathway. In this work, we study this with a model system involving acetylene reduction to ethylene over a series of CuAu alloys. Specifically, by using H2O-D2O mixtures as the electrolyte, we find that increasing the Au content leads to an increased hydrogenation contribution via the LH mechanism. This was supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which showed that Au alloying substantially lowers the activation energy barrier of the LH mechanism. As a result, we propose that consumption of surface-adsorbed *H via the LH mechanism leads to a suppression of hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity and hence improved ethylene selectivity. Through this strategy, the optimal CuAu electrocatalyst achieved a high Faradaic efficiency (FE) > 90% towards ethylene over a wide operating current density window.

Results and discussion

In our previous work, DFT calculations showed that acetylene adsorbs onto the Cu surface in a bridge configuration, aligning parallel to the catalytic surface18,19. As a result, this exposes both carbon sites, resulting in preferential hydrogenation via the ER mechanism17. A prior report by Wang et al. also found that the ER mechanism is the dominant pathway due to a low *H coverage on Cu in the presence of acetylene, which impedes the LH mechanism16. Typically, a high ethylene FE of >90% can be achieved at lower current densities. However, the challenge is that the ethylene FE often drops below 70%20 at the higher current densities (>200 mA cm−2). We reasoned that this issue likely arises from a high *H coverage at these higher current densities. Since the hydrogenation of acetylene occurs primarily through the ER mechanism, any *H present can only be consumed by the competitive HER process, which then leads to a lowered ethylene FE.

Considering this, we hypothesized that steering the acetylene hydrogenation pathway towards the LH mechanism could offer a means to utilize any *H, which would otherwise be contributing towards hydrogen evolution. This could potentially allow for a high ethylene FE to be maintained, even at the higher current densities. To implement this, we took that view that alloying Cu with another element could alter hydrogenation pathway energetics and present a plausible means for shifting the balance between the LH vs. ER mechanism. For this purpose, we selected Au due to its inherently low HER activity and ability to form highly miscible alloys with Cu21.

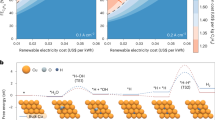

We thus began by employing DFT calculations to examine the activation energy barriers for hydrogenation of acetylene (*CHCH) and the intermediate (*CHCH2) via both the LH and ER mechanisms on Au, CuAu3, Cu3Au and Cu (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Figs. 1–6, and Supplementary Tables 1–3). From the results, we find that hydrogenation of *CHCH on Cu has a strong preference to occur via the ER mechanism (0.39 eV) as compared to the LH mechanism (1.11 eV). The ER mechanism also dominates for the hydrogenation of *CHCH2 on Cu, and we note that both these observations are consistent with our prior work17. The adsorption energies and activation energy barriers were also investigated on exposed step and defect sites (Supplementary Figs. 7–9). For these cases, we find that the ER mechanism is still preferable over the LH mechanism. However, for CuAu3 and Cu3Au we find that differences in activation energy barriers between the LH vs. ER mechanism becomes considerably reduced (Fig. 1a). For instance, with CuAu3 the activation energy barrier via the LH mechanism (0.39 eV) is actually lower than that of the ER mechanism (0.50 eV).

a Activation energy barriers for the conversion of C2H2* to C2H3* (left) and *C2H3 to *C2H4 (right) via the ER and LH mechanisms at −0.5 V vs RHE. b Comparison of the activation barriers for the LH mechanism converting *C2H3 to *C2H4 with the Tafel steps for *H-*H coupling on Au3Cu, AuCu3, and Cu at −0.5 V vs RHE. c Adsorption configurations of *CHCH adsorbed onto a Au, Au3Cu, AuCu3 and Cu slab. The yellow color represents Au atoms, and the red color represents Cu atoms. d Adsorption configurations of *CHCH2 adsorbed onto a Au, Au3Cu, AuCu3 and Cu slab. The yellow color represents Au atoms, and the red color represents Cu atoms.

Further examining this case, we find that adsorption of the *CHCH2 intermediate is substantially different on Cu as compared to CuAu3. On Cu, *CHCH2 adopts a bridge configuration with both C atoms bound to the surface, while on CuAu3 it has an atop configuration with only one C atom bound to the surface (Fig. 1c, d, and Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). As such, the bound C atom on *CHCH2 likely has a higher steric hindrance when adsorbed onto CuAu3. Based on our prior work17,22, this higher steric hindrance inhibits hydrogenation via the ER mechanism, which provides an explanation why the LH mechanism becomes more favorable for hydrogenation of *CHCH2 on CuAu3.

Furthermore, we find that both CuAu3 and Cu3Au exhibit overall lower activation energy barriers for hydrogenation via both the LH and ER mechanism (Fig. 1a, and Supplementary Table 2). As such, our DFT calculations predict that CuAu alloys should have higher acetylene reduction activity as compared to pure Cu. In addition, we examined the activation energy barrier for two *H to couple on these catalyst surfaces (Fig. 1b, and Supplementary Table 3). With Cu, we find that *H coupling (0.63 eV) is more facile compared to *H addition to *CHCH2 via the LH mechanism. As a result, any *H on Cu would be preferentially directed towards hydrogen evolution. However, for Cu3Au and CuAu3, the activation energy barriers become lower for *H addition to *CHCH2. A similar trend is observed by comparing the activation energy barriers of the Heyrovsky pathway in HER with the LH pathway in acetylene hydrogenation (Supplementary Fig. 10). This could suggest that on CuAu alloys, *H can be more readily utilized towards the hydrogenation of acetylene.

Next, we also calculated the adsorption energy of *H on Cu and CuAu alloys as a function of applied potential. From the results, we found that the *H adsorption energy only decreases slightly with increasing cathodic potentials (Supplementary Fig. 11). The LH hydrogenation barriers of *C2H2 on various surfaces (Cu, Cu3Au, CuAu3, and Au) were also evaluated under different hydrogen coverages, specifically at 6/9 monolayer (ML) and 1/9 ML (Supplementary Fig. 12). These results show that the activation energy barriers on Cu, Cu3Au, and CuAu3 remain largely unchanged with increasing *H coverage. In contrast, a noticeable increase in the activation energy barrier is observed with the Au surface. This increase may be attributed to the weakened adsorption of *C2H2 at higher hydrogen coverages, which makes it more difficult to effectively activate the molecule for hydrogenation.

Taken together, our DFT calculations show that alloying Cu with Au could lower reaction pathway energy barriers, steer hydrogenation towards the LH mechanism and suppresses HER activity. It should be noted that the DFT results may not fully represent the catalyst structure and environment under reaction conditions. Hence, the theoretical analysis in this work serves mostly as a qualitative guide for our experimental efforts. In sum, our DFT calculation results therefore predict that CuAu alloys probably have enhanced selectivity and activity towards acetylene reduction to ethylene.

Encouraged by these findings, we prepared gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs) through sputter deposition of a 300 nm thick layer of Cu, Au and a series of CuAu alloys onto porous hydrophobic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) substrates with 0.45 µm pore size23,24 (Supplementary Fig. 13). CuAu alloys of varying composition were synthesized by adjusting the power applied on the Cu and Au targets. The composition of each sample was analyzed using both X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). This yielded Cu:Au ratios of 100:0, 94:6, 85:15, 56:44, 50:50, 37:63 and 0:100. In this work, we will refer to the alloy samples as (X)CuAu, where ‘X’ is the Cu composition. ‘Cu’ and ‘Au’ will refer to 100% Cu and 100% Au, respectively.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with selected area electron diffraction (SAED) was carried out to investigate the structure and morphology of Cu, 94CuAu, 85CuAu, 56CuAu, 50CuAu, 37CuAu and Au. For instance, 85CuAu appears as particles attached to the PTFE substrate (Fig. 2a, b), with the predominant exposed crystalline facet being the (111) plane. Scanning transmission electron microscope High-angle annular dark-field (STEM-HAADF) images and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (STEM-EDS) elemental mapping show that Cu and Au are uniformly dispersed (Fig. 2c–f). Overall, we find that Cu, 94CuAu, 56CuAu, 50CuAu, 37CuAu and Au all exhibit similar morphology and structure (Supplementary Figs. 14–19).

From X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments (Supplementary Fig. 20), we find gradual shifts in the (111) peak which indicate alloy formation and arise from the difference in lattice parameter values between Cu and Au. Furthermore, the single peak in the XRD data confirms the formation of a well-mixed CuAu alloy rather than phase-separated domains. Similarly, X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and XPS data are all consistent with alloying between Cu and Au (Supplementary Figs. 21–23). In addition, the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra indicate that all catalysts exhibit minimal Cu-O and Au-O bonding, which means that Cu and Au exist predominantly in the metallic state.

Next, we sought to evaluate the acetylene reduction performance of Cu, Au and the CuAu alloys using a three-electrode GDE flow cell. We first obtained linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves for each of the samples using 1 M KOH as the electrolyte and acetylene continuously flowing through the gas diffusion chamber. From the results (Supplementary Fig. 24a), we find that Cu, 94CuAu, 85CuAu, 56CuAu all provide similar current response. However, further increasing the Au content results in an obvious current density decrease with 50CuAu, 37CuAu and Au. This is likely because Au sites are inherently poorer for both acetylene reduction and hydrogen evolution.

Consistent with this, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements show that the Au rich samples all exhibit considerably higher charge transfer resistance values (Supplementary Fig. 24b). Furthermore, we performed cyclic voltammetry in a potential window where Faradaic reactions do not occur to provide a qualitative assessment of each of their electrochemical active surface areas (ECSAs). We found these double-layer capacitance values obtained are quite comparable (Supplementary Fig. 25), which preclude surface area effects as a possible explanation for the selectivity differences.

Following this, we performed acetylene reduction bulk electrolysis experiments with product analysis and quantification at cathodic current densities of 50, 100, 200, 300 and 400 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 26, and Supplementary Tables 4–9). We find that Au is almost inactive towards acetylene reduction, with a maximum FE to ethylene of only 8.08% at 50 mA cm−2. At the lower current densities of 50 and 100 mA cm−2, we find no considerable differences in selectivity between Cu and the CuAu alloys, with all samples exhibiting >80% FE to ethylene. However, with Cu the FE to ethylene appears to decline considerably with a concomitant increase in the FE to HER as the current density is increased (Fig. 3a). For instance, at the highest current density of 400 mA cm−2 the FE to ethylene was only 49.15% while the FE to HER was rather considerable at 42.56%.

The FE of acetylene reduction on a Cu and b 85CuAu. c The ethylene FE as a function of current density and Cu composition. d The hydrogen FE as a function of current density and Cu composition. e The stability test on 85CuAu at 100 mA cm−2. All the error bars represent standard deviation based on three independent samples.

Interestingly, for the catalysts with lower Au content, we observed a substantial improvement in the ethylene FE with values of 64.79% and 90.90% for 94CuAu and 85CuAu, respectively at 400 mA cm−2. With 85CuAu, a high ethylene FE is maintained throughout the entire tested current density range, with values of 95.80% at 200 mA cm−2, 96.53% at 300 mA cm−2 and 90.90% at 400 mA cm−2 (Fig. 3b). Notably, the maximum attained ethylene production rate is 22.61 mmol h−1 mg−1, which is competitive with most prior literature reports (Supplementary Fig. 27 and Supplementary Table 10). As for the other catalysts, we find that the ethylene FE declines with increasing Au content, with values of 67.61%, 48.90% and 25.95% with 56CuAu, 50CuAu and 37CuAu, respectively.

These results indicate that there is an optimal Au composition (85CuAu) for maximizing the ethylene FE over a large current density window. This can be visualized in the form of a contour plot (Fig. 3c, d), which depicts ethylene FE as a function of Cu composition and current density. Furthermore, we find that 85CuAu has the lowest onset potential for acetylene reduction along with the highest ethylene partial current density (Supplementary Fig. 26f). Hence, Au alloying was found to boost acetylene reduction activity and selectivity, consistent with our predictions from DFT.

After continuous operation at 100 mA cm−2 for 12 h, the 85CuAu catalyst exhibited only slight performance degradation (Fig. 3e). Considering both Faradaic efficiency and ethylene production rate, our catalyst is comparable to electrocatalysts reported to date (Supplementary Table 11). We also characterized the catalysts after the reaction. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 28, the XRD patterns indicate that both Cu and the CuAu alloys remain (111) dominant after reaction. From XPS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 29, and Supplementary Table 12), we also did not find evidence for the surface enrichment of either Au or Cu with the CuAu alloy samples.

Another prediction of the DFT calculations was that Au alloying would result in an increased contribution of the LH mechanism for hydrogenation. To study the hydrogenation pathway experimentally, we performed isotopic labelling studies with H2O-D2O mixtures with a similar methodology used in our prior work17. Specifically, we began by performing hydrogen and deuterium evolution experiments using 1 M KOH with 50% D2O + 50% H2O (50D2O) as the electrolyte. The H/D isotopic composition of the gas generated can then be determined using mass spectrometry. This is then fitted to evaluate the *H vs *D coverage and hence the probability of H vs D transfer through the LH mechanism. This procedure is repeated for each catalyst, since the *H vs *D coverage is expected to be different in each case.

HDER experiments were carried out at 50 mA cm−2 and we find that as the Cu composition decreases, the H composition of the gas generated increases (Fig. 4a, and Supplementary Table 13). This qualitatively indicates that Au has a higher *H vs *D coverage ratio as compared to Cu. By fitting these results, we obtained H transfer probability values via the LH mechanism to be 91.29%, 92.48%, 91.89%, 93.76%, 94.68%, and 96.09% for Cu, 94CuAu, 85CuAu, 56CuAu, 50AuCu and 37CuAu, respectively (Supplementary Table 14).

a The isotopic composition of HDER as a function of catalyst composition at 50 mA cm−2. b The isotopic composition of ethylene as a function of catalyst composition at 50 mA cm−2 in a 50% H2O-50% D2O mixture with 1 M KOH. c The hydrogenation pathway contributions at 50 mA cm−2. d Correlation between the ethylene FE and hydrogenation pathway. All the error bars represent standard deviation based on three independent samples.

Following this, we evaluated the H transfer probability of the ER mechanism by determining the isotopic composition of the ethylene product from acetylene reduction. This was performed using 50D2O electrolyte with Cu at a current density of 50 mA cm−2. From the results (Fig. 4b), we found that the H composition of the ethylene product is 60.50%, which is calculated excluding the two original H on acetylene. Since the ER mechanism strongly dominates over the LH mechanism for acetylene reduction on Cu, we took this value of 60.50% to be the H transfer probability value of the ER mechanism. Because the ER mechanism involves proton-coupled electron transfer from solvent water directly to the reactant molecule, we further assume that its H transfer probability is independent of the catalyst surface used.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 30, we can find that the variations in the applied current densities do not significantly impact the H/D isotopic composition of the ethylene product on Cu. It is important to note that different applied current densities—corresponding to different applied potentials—can lead to significant variations in electrode surface polarization and the resulting electric field. Hence, we find that differences in the electric field at the electrode surface do not appear to have a significant impact on the probability of H vs. D transfer via the ER pathway.

We then proceeded to perform acetylene reduction on the CuAu alloy catalysts using the same 50D2O electrolyte at 50 mA cm−2. From the results (Fig. 4b, and Supplementary Table 15), we find that with Au alloying, the H composition rises from 60.50% with Cu to 65.90% on 94CuAu and 69.83% on 85CuAu. However, with a further decrease in Cu composition, the H composition begins to decrease, with values of 68.84% on 56CuAu, 65.45% on 50CuAu and 63.52% on 37CuAu.

We also performed experiments to understand if the acetylene partial pressure has an impact on our results. For this, acetylene reduction was carried out in the 50D2O electrolyte using 85CuAu across a range of different acetylene feed concentrations (10%, 20%, 50% and 80%) at a current density of 50 mA cm−2. From the results (Supplementary Fig. 31), we find that the acetylene feed concentration does not have a substantial impact on the H/D isotopic compositions of the ethylene product.

The H/D composition of ethylene generated under higher current densities of 300 and 400 mA cm−2 was also investigated. The results for 300 mA cm−2 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 32 and Supplementary Table 16, where we find that with Au alloying, the H composition rises from 59.50% with Cu to 63.76% on 94CuAu and 69.57% on 85CuAu. However, with a further decrease in Cu composition, the H ratio in ethylene begins to decrease, with values of 66.56% on 56CuAu, 63.02% on 50CuAu and 58.40% on 37CuAu at 300 mA cm−2. The results at 400 mA cm−2 show similar trends (Supplementary Fig. 33a and Supplementary Table 17) and more importantly, these trends are consistent with those at 50 mA cm−2. Hence, these trends in isotopic composition strongly hint that there are gradual changes in the relative contributions of the LH vs. ER mechanism as the alloy composition is varied.

Using the H transfer probability values that we derived, we fitted these isotopic composition results to estimate the individual contributions of the LH vs. ER mechanism to acetylene hydrogenation (see Supplementary Note 1 for details on the calculation method). From this (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Figs. 32–33, and Supplementary Tables 18–20), we found that Au alloying does indeed increase the contribution of the LH mechanism with values of 16.91% with 94CuAu and 29.73% with 85CuAu at 50 mA cm−2. However, with an increase in Au composition, the LH mechanism contribution began to decline with values of 25.10%, 14.49%, and 8.52% for 56CuAu, 50CuAu and 37CuAu at 50 mA cm−2, respectively. Similarly, at 300 mA cm−2, the contribution of LH hydrogenation has values of 12.91% with 94CuAu, which increases to 31.09% with 85CuAu. With further increases in the Au composition, the contribution of LH hydrogenation was observed to decrease to values of 20.60% and 10.01% for 56CuAu and 50CuAu, respectively. We note that the results obtained at 400 mA cm−2 exhibit similar trends as well (Supplementary Fig. 33b). Interestingly, the results show a positive correlation where a higher contribution of the LH mechanism increases the FE towards ethylene (Fig. 4d).

Next, we then evaluated the Tafel slopes of these catalysts towards ethylene production. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 34, the Tafel slope for Cu is 128 mV/dec, which is close to 118 mV/dec and indicates that the rate-determining step involves an electron transfer. This is consistent with hydrogenation occurring via the ER pathway. Comparatively, assuming a rate-determining step involving addition of *H via the LH mechanism, the Tafel slope should have a value close to 59 mV/dec25. Upon alloying with Au, the Tafel slope was observed to decrease. Specifically, the Tafel slopes for 94CuAu and 85CuAu are 92 mV/dec and 89 mV/dec, respectively. Since these values were observed to fall between 60 and 120 mV/dec, this suggests that hydrogenation of acetylene could be a contribution from both the LH and ER mechanism. Interestingly, as the Au content continues to increase, the Tafel slope rises again from 97 mV/dec for 56CuAu to 127 mV/dec for 50CuAu, and finally to 153 mV/dec for 37CuAu. This hints that excessive Au incorporation causes the hydrogenation pathway to shift back towards the ER mechanism, which is notably consistent with the results from our H/D isotopic labelling experiments.

To shed further light into the reaction mechanism, we employed in-situ Raman spectroscopy to detect surface adsorbates on Cu and CuAu alloys (Supplementary Figs. 35–37). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 37, the peak at ~1502 cm−1 corresponds to the C=C bonds of surface conjugated acetylene18. The notably broad width of this band (~50 cm−1) indicates a broad distribution of conjugation lengths, with a parallel adsorption configuration on the Cu surface. As the Au composition increases, this peak is observed to gradually weaken and disappears with 37CuAu. This could be due to poor acetylene adsorption on Au sites, which disrupts surface conjugation.

The peak at ~1535 cm−1 is attributed to the C=C stretching modes of π-bonded *CHCH2 intermediates19. With increasing Au content, this peak shifts from 1535 cm−1 to 1556 cm−1, indicating a transition of *C2H3 adsorption from π/di–σ bonding to σ bonding18. We also observed that as the Au composition increased, the adsorption peak of acetylene at ~1700 cm−1 gradually broadened and shifted toward higher Raman shift values (Supplementary Figs. 36 and 37). This is supported by our DFT calculations which indicate a weaker adsorption energy of acetylene with increasing Au content (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Hence, taken together, our in-situ Raman spectroscopy experiments indicate that Au alloying has a major impact on the adsorption of acetylene. Hence, we postulate that this results in changes reaction activation energy barriers and also shifts the balance between the LH vs. ER hydrogenation pathways.

Based on our combined experimental and computational efforts, here we summarize how Au alloying influences the acetylene hydrogenation pathway (Fig. 5). (1) On pure Cu, acetylene hydrogenation follows the ER pathway, which relies on solvent water. Hence, any *H generated preferentially couples to form H2 and is thus not utilized for acetylene hydrogenation. (2) Upon alloying a small amount of Au into Cu, the activation energy barrier for the LH mechanism is substantially reduced. Although the ER mechanism is still predominant, increasing the contribution of the LH mechanism results in *H consumption, which suppresses HER activity and boosts ethylene selectivity. (3) For catalysts with high Au content, the weak adsorption of acetylene on Au reduces the overall acetylene reduction activity and selectivity. Furthermore, we speculate that the reduction in contribution of the LH mechanism could likely be due to a low coverage of *H on Au sites.

Finally, we evaluated the performance of 85CuAu under dilute acetylene feed conditions and successfully achieved high conversion efficiencies (Supplementary Figs. 38 and 39, and Supplementary Tables 21 and 22). Specifically, in a 10% acetylene feed, the catalyst exhibited an ethylene FE exceeding 95% with an acetylene conversion of ~40%. Under a 2% acetylene feed, the catalyst maintained an ethylene FE of ~40%, with the acetylene conversion exceeding 80%.

Discussion

In this study, we show a model system for acetylene reduction to ethylene using a series of CuAu alloy catalysts. Combining DFT calculations, isotope-labeling experiments in H2O-D2O mixed electrolytes, and in-situ spectroscopy, we demonstrate that increasing the Au content promotes the LH hydrogenation pathway. This pathway utilizes adsorbed *H, thereby suppressing the HER and enhancing ethylene selectivity. Leveraging this approach, the optimized CuAu catalyst achieved a high ethylene Faradaic efficiency of 90.90% at a current density of 400 mA cm−2, with a ethylene production rate of 22.61 mmol h−1 mgcat−1. These results demonstrate a rational strategy to steer hydrogenation pathways for tailored catalytic behavior.

Methods

Materials

Potassium hydroxide (≥90% metal basis), deuterium oxide (99.96%), and iridium(III) chloride hydrate (99.9%) were sourced from Sigma Aldrich. Copper and gold sputtering targets (>99.99%) were acquired from Kurt J. Lesker Company. High-purity gases, including nitrogen (99.99%), helium (99.999%), argon (99.9995%), acetylene (99.5%), and hydrogen (99.9995%), were supplied by Air Liquide Singapore Pte. Ltd. The Fumasep FAA-3-PK-130 anion exchange membrane and titanium mesh were obtained from Fuel Cell Store. Hydrophobic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) substrates with a 0.45 µm pore size were purchased from Beijing Zhongxingweiye Instrument Co., Ltd. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ), used in all experiments, was supplied by an OmniaPure UltraPure Water System. The custom-designed electrochemical flow cell and Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) reference electrodes were procured from Tianjin Aida Hengsheng Technology Development Co. Standard calibration gas mixtures for gas chromatography system calibration were provided by Air Liquide Singapore Pte. Ltd. All materials were used as received without additional purification or processing.

Preparation of electrodes, membrane and electrolyte

CuAu/PTFE electrodes were prepared using magnetron sputtering. The sputtering power was controlled so that the total deposition rate was fixed at 2 Å/s. For 94CuAu, the RF power for Cu target is 250 W while the RF power for Au is 50 W. For 85CuAu, the RF power for Cu and Au are 230 W and 50 W, respectively. For 56CuAu, the RF power for Cu and Au are 50 W and 50 W, respectively. For 50CuAu, the RF power for Cu and Au are 50 W and 120 W, respectively. For 37CuAu, the RF power for Cu and Au are 50 W and 200 W, respectively. The deposition time should be longer when applying low RF power. The IrOx coated Ti mesh electrode was prepared using a thermal decomposition method, following the methodology as described by Luc et al.26. The loading of catalysts on working electrode is ~0.3 mg cm−2, and the working area is 1 cm2. The acetylene reduction performance was evaluated in freshly prepared 1 M KOH solution with a pH of ~13.6. For isotopic labeling experiments, to prepare 100 ml of the 50% H2O and 50% D2O (50D2O) electrolyte, we mixed 48.89 ml of H2O with 50 ml of D2O and subsequently added 5.55 g of KOH. The Fumasep FAA-3-PK-130 anion exchange membrane is treated and stored in 1 M KOH solution.

Materials characterization

SEM images and EDX measurements were obtained using a JSM-7610FPlus. X-ray diffraction was performed using a Bruker D8 Discover X-ray diffractometer. XPS measurements were carried out using a Kratos AXIS Supra+. TEM images were acquired using a Titan 80–300 keV and Tecnai G2 80–200 keV (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). Ex-situ XAS experiments were performed at BL-01C1, TLS and BL-32A, TPS, NSRRC (Taiwan). X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy and EXAFS at the Cu K-edge and Au L3-edge, was conducted in total fluorescence yield mode at BL-32A of the TPS and BL-01C1 of NSRRC, respectively.

Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical measurements carried out in this work were using an Autolab PGSTAT204 potentiostat. Acetylene reduction was performed using the same custom-made electrochemical flow cell. An anion exchange membrane (2 cm × 2 cm) was used to separate the cathode and anode chambers. The volume of each chamber is 1.5 mL. The acetylene reduction experiments were performed under galvanostatic conditions at cathodic current densities of 50, 100, 200, 300 and 400 mA cm−2. The gas products were determined using a gas chromatograph with a thermal conductivity detector and a flame ionization detector (Agilent 8860 GC). For quantification of the gaseous products, 1 mL of the outlet gas from the electrochemical cell was sampled using a gas-tight syringe and injected into the gas chromatograph. Gas samples were injected every 15 min. The Faradaic efficiency (FE) of each gaseous product was determined using the following equation:

where N denotes the number of electrons transferred, F is the Faraday constant, v represents the gas flow rate, c is the concentration of the detected gaseous product (in ppm), i is the total current, and Vm is the molar volume of the gas. The gas flow rate at the outlet of the electrochemical cell was determined using a bubble flow meter.

Ag/AgCl electrode was employed as the reference electrode. To convert potentials to the RHE scale, the following equation was applied:

LSV tests were conducted at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1. The solution resistance was determined using potentiostatic EIS, scanning through a frequency range of 100,000 Hz to 0.1 Hz. The value of solution resistance in this work is ~6.37 Ω. To provide a qualitative assessment of each of ECSAs, we performed cyclic voltammetry in a potential window where Faradaic reactions do not occur. The double-layer capacitance (Cdl) was determined from the slope of the linear fit of half the current density difference, Δj = (ja−jc)/2, plotted against the scan rate. CV measurements were conducted within a 0.1 V potential range at scan rates of 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mV s−1.

In-situ Raman spectroscopy

A Horiba LabRam Odyssey Nano Raman Spectrometer system was used for conducting in-situ Raman spectroscopy. To facilitate the measurements, a custom-designed flow cell was employed, featuring a gas chamber at the rear end to facilitate a continuous flow of acetylene (Supplementary Fig. 40). Raman spectra were collected by immersing an Olympus N2667700 water immersion objective into the electrolyte.

Isotopic composition analysis of gas products

The isotope experiments were conducted in a 1 M KOH mixed electrolyte containing 50% H2O and 50% D2O. During the acetylene reduction tests, the gas flow rate was set to 10 sccm. Each sample was tested for 15 min under each applied current density. The gaseous products from acetylene reduction were collected using gas bags. Subsequently, samples from the gas bags were extracted for GC-MS analysis. The Agilent 8890A GC with a 5977C inert XL MSD (triple axis detector) was employed for determining the isotopic compositions of ethylene. An Agilent PoraBOND Q capillary column (50 m) with an internal diameter of 0.32 mm and film thickness of 5 µm (part number CP7352) was used. Helium (99.999%) served as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 1.2 ml min–1 through the column. The analysis of the HDER isotopic compositions based on the mass spectrometry. The method (Supplementary Note 2, and Supplementary Tables 23–25) in this work is similar to our previous work17.

Density functional theory calculations

In this study, we employed DFT calculations which were executed using the ab initio simulation program VASP27,28, incorporating the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional29,30. Electron-ion interactions were modeled using the Projector-Augmented Wave method, and the plane-wave basis set was defined with a cut-off energy of 450 Ev31,32. To accurately represent long-range dispersion interactions between the adsorbates and catalysts, the D3 correction method by Grimme et al. was utilized33. Brillouin zone integration was performed using a 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh. All the adsorption geometries were optimized using a force-based conjugate gradient algorithm, while transition states (TSs) were located with a constrained minimization technique34,35,36 (available in Supplementary Data Set). For Electrochemical barrier calculations, we utilized the computational hydrogen electrode model to calculate reaction energies as a function of potential37. At a potential of U = 0 V versus RHE, protons and electrons are in equilibrium with hydrogen gas (H2) under standard conditions of 101,325 Pa and 298 K, applicable across all pH levels:

At a given U ≠ 0 V versus RHE,

GC-DFT calculations

GC-DFT calculations were performed in JDFTx using geometries pre-optimized with VASP38. Single-point energies were evaluated at different applied potentials to assess the robustness of the solvation model (Supplementary Fig. 41). The Brillouin zone was sampled with a 3 × 3 × 1 Gamma-centered k-point mesh suitable for slab calculations. Ultrasoft pseudopotentials from the GBRV library were employed, and exchange–correlation effects were treated using the PBE generalized gradient approximation. A plane-wave kinetic-energy cutoff of 20 Hartree was used. Electronic minimization proceeded to a convergence threshold of 1 × 10−5 Hartree with a maximum of 1000 iterations. Finite-temperature Fermi smearing of 0.1 eV was applied. Implicit solvation was modeled using CANDLE within LinearPCM, with water as the solvent and ionic concentrations of 0.1 M K⁺ and F⁻. A target electron chemical potential was imposed, van der Waals interactions were included, and all calculations were performed with spin polarization along the z-axis.

Geometry optimizations were carried out using a conjugate-gradient algorithm with a 0.2 fs time step and a force convergence threshold of 0.05 eV/Å. The stress tensor was computed, but only atomic positions were relaxed, keeping the cell shape and volume fixed. Implicit solvation during geometry optimization was described using VASPSOL, with the surface-tension cavity parameter set to 80 to represent the aqueous environment39,40. For explicit water structures, the water density was chosen to match that of the Pt (111) bilayer observed in UHV experiments for the corresponding cell dimensions41. Water configurations were generated using a minima-hopping protocol that alternates molecular-dynamics steps with local geometry relaxations to sample low-energy structures42. To emulate a charged electrochemical double layer, a single H atom was added to the water layer; in the ground state, its electron transfers to the metal, thereby establishing a charge-separated interface43. All reported energies include zero-point energy corrections derived from vibrational analyses, ensuring accurate comparisons of relative stabilities and reaction barriers across systems.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Universality in heterogeneous catalysis. J. Catal. 209, 275–278 (2002).

Calle-Vallejo, F., Loffreda, D., Koper, M. T. M. & Sautet, P. Introducing structural sensitivity into adsorption–energy scaling relations by means of coordination numbers. Nat. Chem. 7, 403–410 (2015).

Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science 355, eaad4998 (2017).

Medford, A. J. et al. From the Sabatier principle to a predictive theory of transition-metal heterogeneous catalysis. J. Catal. 328, 36–42 (2015).

Nørskov, J. K., Bligaard, T., Rossmeisl, J. & Christensen, C. H. Towards the computational design of solid catalysts. Nat. Chem. 1, 37–46 (2009).

Nørskov J. K. et al. Origin of the Overpotential for Oxygen Reduction at a Fuel-Cell Cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Liu, M. et al. Enhanced electrocatalytic CO2 reduction via field-induced reagent concentration. Nature 537, 382–386 (2016).

Chen, L. D., Urushihara, M., Chan K. & Nørskov J. K. Electric Field Effects in Electrochemical CO2Reduction. ACS Catalysis 6, 7133–7139 (2016).

Bingqing, W. et al. Nanocurvature-induced field effects enable control over the activity of single-atom electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 15, 1719 (2024).

Liu, Z., Zhao, Z., Peng, B., Duan, X. & Huang, Y. Beyond extended surfaces: understanding the oxygen reduction reaction on nanocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17812–17827 (2020).

Yao, Y. et al. Inverse kinetic isotope effects in the oxygen reduction reaction at platinum single crystals. Nat. Chem. 15, 271–277 (2023).

Marković, N., Gasteiger, H. & Ross, P. N. Kinetics of Oxygen Reduction on Pt(hkl) Electrodes: Implications for the Crystallite Size Effect with Supported Pt Electrocatalysts. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 1591–1597 (1997).

Deng, W., Zhang, P., Seger, B. & Gong, J. Unraveling the rate-limiting step of two-electron transfer electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. Nat. Commun. 13, 803 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Evidence for distinct active sites on oxide-derived Cu for electrochemical nitrate reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 30708–30714 (2024).

Feng, J. et al. Modulating adsorbed hydrogen drives electrochemical CO2-to-C2 products. Nat. Commun. 14, 4615 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Highly efficient ethylene production via electrocatalytic hydrogenation of acetylene under mild conditions. Nat. Commun. 12, 7072 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Isotopic labelling of water reveals the hydrogen transfer route in electrochemical CO2 reduction. Nat. Chem. 17, 334–343 (2025).

Liu, G. et al. Electrochemical polymerization of acetylene on Rh electrodes probed by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Electroanal. Chem. 594, 73–79 (2006).

Bu, J. et al. Selective electrocatalytic semihydrogenation of acetylene impurities for the production of polymer-grade ethylene. Nat. Catal. 4, 557–564 (2021).

Bai, L. et al. Efficient industrial-current-density acetylene to polymer-grade ethylene via hydrogen-localization transfer over fluorine-modified copper. Nat. Commun. 14, 8384 (2023).

Sheng, W., Myint, M., Chen, J. G. & Yan, Y. Correlating the hydrogen evolution reaction activity in alkaline electrolytes with the hydrogen binding energy on monometallic surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 1509 (2013).

Zhang, J. et al. Elucidating the electrochemical hydrogenation route by spatially isolating competing pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 26040–26048 (2025).

Dinh, C.-T. et al. CO2 electroreduction to ethylene via hydroxide-mediated copper catalysis at an abrupt interface. Science 360, 783–787 (2018).

Dolmanan, S. B. et al. Local microenvironment tuning induces switching between electrochemical CO2 reduction pathways. J. Mater. Chem. A. 11, 13493–13501 (2023).

Fletcher, S. Tafel slopes from first principles. J. Solid State Electrochem. 13, 537–549 (2009).

Luc, W., Rosen, J. & Jiao, F. An Ir-based anode for a practical CO2 electrolyzer. Catal. Today 288, 79–84 (2017).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7413–7421 (1999).

Blöchl, P. E., Jepsen, O. & Andersen, O. K. Improved tetrahedron method for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B. 49, 16223–16233 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Michaelides, A. et al. Identification of general linear relationships between activation energies and enthalpy changes for dissociation reactions at surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 3704–3705 (2003).

Liu, Z.-P. & Hu, P. General rules for predicting where a catalytic reaction should occur on metal surfaces: a density functional theory study of C−H and C−O bond breaking/making on flat, stepped, and kinked metal surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 1958–1967 (2003).

Alavi, A., Hu, P., Deutsch, T., Silvestrelli, P. L. & Hutter, J. CO oxidation on Pt(111): an ab initio density functional theory study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 3650–3653 (1998).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Zhang, C. & Wang, Z. Voltage- and pH-driven evolution of multi-pathway C–C coupling in CO2 electroreduction on copper. Chem. Sci. 16, 20978–20989 (2025).

Mathew, K., Kolluru, V. S. C., Mula, S., Steinmann, S. N. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit self-consistent electrolyte model in plane-wave density-functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 234101 (2019).

Mathew, K., Sundararaman, R., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Arias, T. A. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit solvation model for density-functional study of nanocrystal surfaces and reaction pathways. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 084106 (2014).

Ogasawara, H. et al. Structure and bonding of water on Pt(111). Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 276102 (2002).

Goedecker, S. Minima hopping: an efficient search method for the global minimum of the potential energy surface of complex molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 9911–9917 (2004).

Rossmeisl, J., Skúlason, E., Björketun, M. E., Tripkovic, V. & Nørskov, J. K. Modeling the electrified solid–liquid interface. Chem. Phys. Lett. 466, 68–71 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Y.L. acknowledges support and funding from the A*STAR (Agency for Science, Technology and Research) under its LCERFI program (Award No: U2102d2002) and NRF Fellowship (Award No: NRF-NRFF14-2022-0003) and the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme (AxCIS Lab – AI xploration of Catalysis with Inorganics and Surfaces, Development of Advanced Catalysts for Electrochemical Carbon Abatement, project code 370184872). The computational study is supported by the Marsden Fund Council from Government funding (21-UOA-237) and Catalyst: Seeding General Grant (24-UOA-048-CSG), managed by Royal Society Te Apārangi. All DFT calculations were carried out on the New Zealand eScience Infrastructure (NeSI) high-performance computing facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and Z.W. supervised the project. Y.L. and J.Z. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. J.Z. carried out all the experimental work. C.Z. performed all the computational work. T.F. and M.W. performed the in-situ Raman spectroscopy experiments. S. Wang carried out the mass spectrometry analysis. W.T. and Z.A. obtained TEM images of the catalyst. Y.Z. and Z-P.W. assisted in electrocatalytic analysis. Q.Y. conducted XRD measurement. R.Y., Y-C.C., Y-T.C. and S.H. assisted in XAS measurements and analysis. Y.L. and J.Z. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and assisted during the manuscript preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zhiqin Liang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Zhang, C., Tjiu, W.W. et al. Catalyst alloying enables control over the electrochemical hydrogen transfer route. Nat Commun 17, 671 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67317-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67317-z