Abstract

Congenital viral infections can have severe consequences for pregnancy and fetal outcomes. Remarkably, the fetal-derived placenta serves as a robust barrier to infection through meticulous regulation by immune effectors and cytokines. Yet, the regulatory roles of many cytokines remain undefined at the maternal-fetal interface, including Interleukin-27 (IL-27). Here, we show that trophoblast organoids derived from human placentas constitutively express both IL-27 and its receptor, and restrict Zika virus infection through IL-27 signaling. Through bulk RNA-sequencing of trophoblast organoids in the absence and presence of IL-27 signaling, we demonstrate IL-27-mediated upregulation of antiviral genes. Finally, we show that IL-27 signaling is critical to restricting placental viral burdens and protecting against pathologic fetal outcomes during murine congenital Zika virus infection. In this work, we demonstrate a novel role for IL-27 in the placenta and establish IL-27 as an innate antiviral defense at the maternal-fetal interface during congenital viral infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the critical developmental period of pregnancy, there are substantial consequences to infection. Despite complex immune regulation at the maternal-fetal interface, a subset of pathogens can evade host immune responses, cross the placental barrier, and establish congenital infection in the fetus1. Zika virus (ZIKV), a mosquito-borne, positive-sense RNA flavivirus, is one example of a congenital viral pathogen2. Depending on the time of infection, vertical transmission of ZIKV can cause adverse pregnancy outcomes such as microcephaly, preterm birth, and even fetal demise3,4,5. As congenital ZIKV can have a detrimental impact on fetal health, there is a critical need to identify antiviral effectors at the maternal-fetal interface.

The fetal-derived placenta serves as an effective barrier to congenital viral infections through its constitutive expression of antimicrobial cytokines6. For example, Type I interferons (IFNs) are a family of innate antiviral cytokines that are known to restrict viral replication through the rapid induction of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs)7. However, while type I IFN (IFNα, IFNβ) signaling is essential for healthy gestation, the classical antiviral state driven by type I IFNs can also disrupt placental development and mediate fetal pathology during congenital ZIKV infection8,9. Yet, the closely related type III IFNs (IFNλ) are constitutively produced by the placenta and have been shown to restrict ZIKV infection without causing fetal pathology10,11,12. While the role of type III IFNs in placental immunity is well established, it is unknown whether other cytokines perform similar antiviral functions at the maternal-fetal interface.

Interleukin 27 (IL-27) is a heterodimeric cytokine that is produced by extravillous trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts in the placenta throughout gestation; yet, the functional consequence of IL-27 signaling during pregnancy is unknown13. In other contexts, IL-27 is a potent modulator of both innate and adaptive immune responses and has direct antiviral activities14,15. Interestingly, a study by Kwock et al. found that IL-27 induces antiviral gene expression in a STAT1-dependent manner to confer protection against ZIKV infection in human keratinocytes16. Together, these findings led us to ask whether IL-27 contributes to antiviral immunity at the maternal-fetal interface.

In this work, we reveal that IL-27 signaling is antiviral in fetal cells of the placenta using a primary human trophoblast organoid model. We then define the transcriptional profile of IL-27-stimulated trophoblast organoids through bulk RNA-sequencing and demonstrate IL-27-mediated antiviral gene expression in fetal trophoblasts, thus uncovering possible mechanisms of viral restriction by IL-27 at the maternal-fetal interface. We compare IL-27 to known IFNλ responses in the placenta, and identify a joint role of IL-27 and IFNλ signaling in regulating ZIKV infection of trophoblasts. Finally, we show that IL-27 signaling is critical within the context of congenital murine ZIKV infection, as IL-27 restricts placental ZIKV burdens and is protective against pathologic fetal outcomes. Together, these findings establish IL-27 as an innate antiviral defense at the maternal-fetal interface and highlight its potential for combating congenital ZIKV infections and supporting healthy fetal outcomes.

Results

Human trophoblast organoids constitutively express IL-27 and IL27RA

Prior studies indicate that IL-27 and its receptor, IL27RA, are expressed in the placenta throughout gestation13. We generated primary trophoblast (TO) and decidual (DO) organoid lines from first trimester (6-12 post-conception weeks) human placental tissues according to previously established methods and initially sought to confirm IL-27 and IL27RA expression in these models (Supplementary Table 1)17,18,19. Prior to experimentation, TOs and DOs were grown in Matrigel to support self-organization of 3D structures and were routinely passaged every 6-8 days, with media changes every 2-3 days. We observed that our first trimester TO and DO cultures recapitulated the morphology of previously established TO and DO lines and exhibited distinct TO and DO structures that could be visualized via brightfield microscopy (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Fig. 1A)17,18,19. Additionally, purity of TO and DO cultures was validated prior to experimentation via over-the-counter pregnancy test strips, which detected a presence or absence of secreted trophoblast-specific hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in TO- and DO-conditioned media, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1,AB).

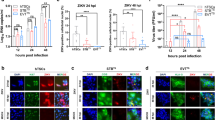

A Representative brightfield images of single trophoblast organoid (TO) culture at 1-, 3-, and 6-days post-passage. 5X magnification, scale bar 1000 μm (top). Insets denote area captured at 10X magnification, scale bar 200μm (bottom). For all 4 biological TO donors, experiment was repeated independently >4 times with similar results. B Expression of IL-27 cytokine (p28, EBI3) and receptor (WSX1, gp130) subunit genes by decidual organoids (DOs) and TOs at day 6 post-passage as determined by quantitative RT-PCR, relative to housekeeping gene HPRT1. Graphs represent 3 experimental replicates from 4 biological donors of TOs (circles, squares, triangles, and diamonds) and 3 biological donors of DOs (circles, squares, and triangles). Data presented as mean values ± SEM. C Conditioned media were collected from TO cultures from 3 biological donors at 1-, 24-, 48-, and 72-h post-passage and secreted IL-27 was measured via human IL-27 ELISA. Graph represents 5 experimental replicates per timepoint for donor 1 TOs (circles); Graph represents 3 experimental replicates per timepoint for donor 2 and 3 TOs (squares, triangles). Data presented as mean values ± SD. D Representative immunofluorescent images of TOs at day 6 post-passage. 10 μm TO cross-sections were stained for DAPI (blue), Ki67 for cytotrophoblasts (white), SDC1 for syncytiotrophoblasts (green), and IL27RA (magenta). White box indicates zoom inset and white dashed line demarcates regions of cytotrophoblasts (CTB) and syncytiotrophoblasts (STB). 20X magnification, Z-stack, merged. Scale bar, 100μm. Images representative experiments independently repeated in 4 biological TO donors with similar results. E. TOs from 2 biological donors (circles, diamonds) were pre-treated with neutralizing antibodies prior to infection with ZIKV-CAM, as described in Supplementary Fig. 2,A. TO cultures were then collected at 1-, 24-, or 48-h post-infection (hpi) for RNA analysis. Graph displays ZIKV viral RNA expression in TOs as determined by quantitative RT-PCR relative to housekeeping gene HPRT1, normalized to isotype control-treated organoids. Graph represents 4 independent infections preformed in first TO donor (circles) and 3 independent infections preformed in second TO donor (diamonds). Data presented as mean values ± SEM.

We first assessed the expression of IL-27 subunits (p28, EBI3) and IL27RA subunits (WSX1, gp130) in unstimulated TO and DO cultures via quantitative RT-PCR. We found that both TOs and DOs expressed high levels of transcripts for the shared cytokine and receptor subunits EBI3 and gp130; however, mRNA expression of unique IL-27 and IL27RA subunits p28 and WSX1 was only observed in TOs (Fig. 1B). To corroborate this finding, we measured secreted IL-27 protein in conditioned media from unstimulated TO cultures at various timepoints via enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). We show that IL-27 is constitutively produced by TO cultures beginning as early as 24 h post-passage, with increasing production as TOs grew in culture (Fig. 1C).

To determine which cells within the multicellular TO are capable of responding to IL-27, we performed immunofluorescence microscopy for specific trophoblast markers and IL27RA. Ki67 staining identified highly proliferative cytotrophoblasts (CTB) at the periphery of TOs, while SDC1 staining identified multinuclear syncytiotrophoblasts (STB) at the center of TOs, thus demonstrating the inward-facing apical surface and “inside-out” orientation that is characteristic of TOs and other three-dimensional organoid models (Fig. 1D)18,20. We observed strong IL27RA expression within CTB regions of TOs, with only some STB regions expressing IL27RA (Fig. 1D; magenta). Together these findings indicate that IL-27 and IL27RA signaling machinery is intact in the TO model, thus validating TOs as an appropriate model to study IL-27 and IL27RA signaling in the human placenta.

We next sought to determine whether IL-27 signaling regulates congenital ZIKV infection in trophoblasts. Briefly, TO cultures derived from two independent donors were pretreated with either isotype control or IL-27-neutralizing antibodies prior to infection with Cambodian ZIKV. At 1-, 24-, or 48-h post-infection, TOs and culture supernatants were then collected for viral burden analyses (Supplementary Fig. 2A). By measuring viral RNA via quantitative RT-PCR, we showed that TO cultures were susceptible to ZIKV infection, and that neutralization of IL-27 led to significantly increased TO viral RNA levels relative to control organoids at both 24- and 48 h post-infection (Fig. 1E). Additionally, we quantified virus production in TO culture supernatants via plaque assays and found a modest increase in infectious viral particles for IL-27-neutralized TOs relative to control organoids at 24 and 48-h post-infection (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Together these data indicate that IL-27 signaling restricts ZIKV infection of fetal trophoblasts and thus is an important contributor to antiviral immunity in the placenta.

IL-27 induces antiviral gene expression in trophoblast organoids

Given the functional IL-27 signaling circuit in TOs and its known capacity to restrict viral infection in other contexts, we next sought to define IL-27-mediated gene expression changes in TOs. Although we show in Fig. 1B-C that TO cultures are constitutively producing and responding to IL-27, TOs have also been shown to constitutively produce and respond to other antiviral cytokines such as IFNλ21 Due to this robust antiviral cytokine production, we first aimed to quantify basal antiviral gene expression levels in TO cultures. To capture the basal TO state, TO cultures were treated with vehicle (PBS) and isotype control antibody (Fig. 2A; “Isotype”). To broadly mitigate signaling downstream of cytokine receptors and capture an “unstimulated” TO state, additional TO cultures were treated with Janus-kinase inhibitor Ruxolitinib (Rux) and isotype control antibody (Fig. 2A; “Rux”). We then measured the expression of common antiviral genes previously shown to be associated with IL-27 signaling (MX1, OAS2 and IFIT1) in Isotype- and Rux-treated TOs via quantitative RT-PCR16,22. As expected, we observed a strong basal expression of MX1, OAS2, and IFIT1 in Isotype-treated TOs, with antiviral gene expression largely inhibited following Rux treatment (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the antiviral gene expression observed in Isotype-treated TOs is reflective of all cytokines expressed by TOs in their basal state, including IL-27 and IFNλ. We next sought to delineate IFNλ-specific and IL-27-specific changes in antiviral gene expression in TOs. To corroborate that IFNλ can induce antiviral gene expression independently of IL-27, TO cultures were pretreated with IL-27 neutralizing antibody followed by stimulation with recombinant human IFNλ-1 and 3 (Fig. 2A; “IFNλ”). Conversely, to demonstrate that IL-27 can induce antiviral gene expression independently of IFNλ, TO cultures were pretreated with IFNλ-1 and IFNλ-3 neutralizing antibodies followed by stimulation with recombinant human IL-27 (Fig. 2A; “IL-27”). Isotype- and Rux-treated TO cultures were also included as positive and negative controls, respectively (Fig. 2A). We found that IL-27 stimulation of TOs in the absence of IFNλ significantly upregulated the expression of antiviral genes MX1, OAS2 and IFIT1, relative to Rux-treated TOs (Fig. 2C). These findings were corroborated using TOs from a second biological donor, providing support that IL-27-mediated antiviral gene expression is a representative response of human trophoblasts (Supplementary Fig. 3-B). In both donors, though we observed no significant difference in the relative antiviral gene expression levels of IL-27-stimulated TOs and Isotype-treated TOs, this was expected given that Isotype-treated TOs reflect gene expression changes downstream of all constitutively expressed cytokines. These results suggest that IL-27 has the capacity to induce antiviral gene expression in TOs independently of IFNλ, and that constitutive IL-27 signaling contributes to the robust basal antiviral state of TOs.

A Table of experimental conditions for antiviral gene expression analyses in (B, C). B TO antiviral gene expression as determined by quantitative RT-PCR, relative to housekeeping gene HPRT1. Graphs display 5 experimental replicates from 1 TO donor. Statistical analysis performed with multiple unpaired t-tests (two-sided Mann-Whitney), *p < 0.05 (adjusted p values = 0.023621). Data presented as mean values ± SEM. C TO antiviral gene expression as determined by quantitative RT-PCR, relative to Rux. Graphs display 5 experimental replicates from 1 TO donor. Statistical analysis performed with ordinary one-way Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns=not significant (MX1 from left, p = 0.0125, <0.0001, 0.0003, 0.2709; IFIT1 from left, p = 0.0031, <0.0001, 0.0001, 0.3945; OAS2 from left, p = 0.0141, <0.0001, 0.0012, 0.6252). Data presented as mean values ± SEM. D Left: Volcano plots depicting differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in IL-27-stimulated TOs and IFNλ-stimulated TOs. Statistical analysis performed via two-sided t-test with Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate correction. Vertical dashed lines: 0.5 log fold-change cutoffs; Horizontal dashed line: 0.05 adjusted p-value cutoff. Right: Venn diagram depicts total upregulated DEGs in IL-27- and IFNλ-stimulated conditions, with the 5 shared genes highlighted in red text on volcano plots. E Select upregulated pathways from gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). Figure displays top 8 pathways by order of normalized enrichment score (NES). Numbers at end of bars indicate total number of genes associated with each term. Red asterisks indicate pathways that were enriched in both IL-27- and IFNλ-stimulated TOs. F ZIKV viral RNA expression in TOs at 24-h post-infection, as determined by quantitative RT-PCR relative to housekeeping gene HPRT1, normalized to isotype control-treated organoids. Graph represents 6 independent infections in single TO donor. Statistical analysis performed with Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 (From left, p = 0.0383, 0.0480, 0.0003). Data presented as mean values ± SD. G Antiviral gene expression in ZIKV-infected TOs as determined by quantitative RT-PCR, relative to Isotype. Graphs display 5 experimental replicates from single TO donor. Statistical analysis performed with Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (IFIT1 from left, p = 0.0119, 0.0039; MX1 from left, p = 0.0484, 0.0019; PARP9 from left, p = 0.0033, 0.0163). Data presented as mean values ± SEM.

We next aimed to further define the transcriptional impact of IL-27 signaling in TOs and identify possible mechanisms of viral control in an unbiased manner. TO cultures were pretreated with either IL-27-neutralizing, IFNλ-neutralizing, or isotype control antibodies for 72 h prior to collection. Simultaneously, additional TO cultures were stimulated with either recombinant human IL-27, recombinant human IFNλ, or vehicle control (PBS) for 24 h prior to collection. RNA was then isolated from all TOs and bulk RNA-sequencing was performed. We confirmed that TO cultures transcriptionally recapitulate the placental tissue of origin and express various placental markers (ERVW−1, HSD3B1, XAGE2, GATA3), including those specifically associated with STBs (CGA) and CTBs (TP63) (Supplementary Fig. 4)18. As expected, we observed little-to-no expression of decidual markers MUC1, MUC5A/B, and SOX17 in the TO cultures17. Importantly, the bulk RNA-sequencing analysis recapitulated our initial findings that the IL-27 cytokine (p28, EBI3) and receptor (IL27RA, WSX-1) subunits are constitutively expressed by TOs (Supplementary Fig. 4). Our bulk RNA-sequencing analysis also revealed distinct transcriptional signatures of TOs cultured in the absence/presence of IL-27 and IFNλ (Supplementary Fig. 5A, B, Supplementary Data 1). Given the IL-27-mediated changes in gene expression observed in the basal state for vehicle and isotype controls, we instead sought to compare the transcriptional profile of IL-27-stimulated TOs to IL-27-neutralized TOs. This analysis revealed 10 genes that were significantly upregulated in IL-27-stimulated TOs relative to IL-27-neutralized TOs (Fig. 2D). Of these 10 genes, we identified 5 common antiviral genes that were also significantly upregulated in IFNλ-stimulated TOs relative to IFNλ-neutralized TOs (IFIT1, DTX3L, PARP9, PARP14, PSME1; Supplementary Table 2)23,24,25,26. Finally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed an upregulation of viral regulatory pathways in both IL-27- and IFNλ-stimulated TOs (Fig. 2E), with similar antiviral genes driving the enriched gene set networks (Supplementary Fig. 5C, D, Supplementary Data 2, 3).

In previous studies, IFNλ has been shown to regulate ZIKV infection of fetal trophoblasts through autocrine signaling10,11,12. Given that IL-27 and IFNλ modulate similar antiviral genes in TOs, we next wanted to explore the possibility of IL-27 and IFNλ signaling interplay in regulating ZIKV infection of TOs. Briefly, TO cultures were pretreated with either isotype control, α-IL-27, αIFNλ, or a combination of both α-IL-27 and α-IFNλ antibodies. TO cultures were then infected with ZIKV-CAM for 24 h and collected for viral burden analysis via quantitative RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Interestingly, we demonstrate in 2 TO donors that neutralization of both IFNλ and IL-27 resulted in increased ZIKV RNA levels relative to neutralization of IFNλ or IL-27 alone (Fig. 2F, Supplementary Fig. 3C). This suggests that while IL-27 and IFNλ have independent antiviral activities at the maternal-fetal interface, together they play a joint role in regulating ZIKV infection of trophoblasts.

We next sought to determine whether the shared DEGs identified through bulk RNA-sequencing of IL-27 and IFNλ-stimulated TOs were critical effectors in the restriction of ZIKV infection in TOs. We measured the expression of our top 2 shared DEGs (IFIT1, PARP9), as well as antiviral gene MX1, in ZIKV-infected TO samples via quantitative RT-PCR. Here we observed that infected, IL-27-neutralized TOs had significantly lower expression of IFIT1 relative to infected, Isotype-treated TOs, thus identifying IFIT1 as a possible candidate for IL-27-mediated restriction of ZIKV in TOs (Fig. 2G). Additionally, we observed the lowest expression of IFIT1, PARP9, and MX1 in IFNλ + IL-27-neutralized TOs, which exhibited the greatest ZIKV burdens (Fig. 2F, G). These analyses support that the antiviral genes identified through RNA-sequencing are likely important effectors in restricting ZIKV infection of trophoblasts.

Taken together, these data suggest that while IL-27 and IFNλ have independent antiviral activities at the maternal-fetal interface, and together they play a joint role in maintaining the basal antiviral state of the placenta and regulating ZIKV infection of trophoblasts.

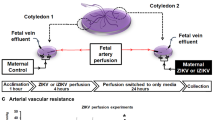

IL-27 is primarily produced within the decidua in the murine placenta

Previous studies have demonstrated constitutive production of IL-27 subunit p28 in human placental tissues throughout gestation, therefore we sought to characterize IL-27 production and kinetics in healthy murine placental tissues13. First, we obtained lysates from whole murine placentas including maternal decidua at various gestational timepoints and measured IL-27 protein levels via ELISA. We observed that IL-27 is constitutively produced in the murine placenta throughout gestation (Fig. 3A). To visualize cellular production of IL-27 by maternal and fetal cells in the murine placenta, we next utilized p28-GFP reporter mice27. We mated p28-GFP−/− dams and p28-GFP+/− sires to generate a litter of fetuses that either lacked (p28-GFPNull) or expressed fetal-derived p28-GFP (p28-GFPF). In parallel, we mated p28-GFP+/− dams and p28-GFP−/− sires to generate litters of fetuses that retained maternal p28-GFP expression only (p28-GFPM) or expressed both maternal- and fetal-derived p28-GFP (p28-GFPFM) (Fig. 3B). Placentas were collected at embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) for immunofluorescence microscopy, and the maternal decidua (Dc) and fetal labyrinth (Lb) regions were defined according to endothelial cell (CD31) architecture (Fig. 3C). We observed robust p28-GFP signal within the decidua of p28-GFPF, p28-GFPM, and p28-GFPFM mice (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, we observed significantly more fetal-derived p28-GFP than maternal-derived p28-GFP within the decidua (Fig. 3D, E). Although we hypothesized that p28 would be expressed within the fetal labyrinth, as this region contains murine trophoblast lineages analogous to the human trophoblasts shown to constitutively express IL-27, we observed minimal p28-GFP signal within the labyrinth region of p28-GFPF, p28-GFPM, and p28-GFPFM mice (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Fig. 6A, B)6,28. Together these findings indicate that IL-27 is primarily produced at the murine maternal-fetal interface within the decidua, largely by cells of fetal origin.

A Whole placental lysates (placenta and decidua) were collected from uninfected C57BL/6 mice at E9.5, E13.5, and E17.5 of gestation, and IL-27 protein levels were measured via ELISA. Each data point represents IL-27 concentration of an individual placenta. For E9.5 and E13.5, graph represents placentas obtained from 2 independent litters; For E17.5, graph represents placentas obtained from one independent litter. Data presented as mean values ± SD. B Schematic represents breeding schemes used to delineate maternal and fetal p28 production in uninfected murine placentas and deciduas. Left: p28-GFP−/− dam x p28-GFP+/− sire crosses were used to generate placental tissues that lacked (I., p28-GFPNull) or expressed fetal-derived p28-GFP (II., p28-GFPF). Right: p28-GFP+/− dam x p28-GFP−/− sire crosses were used to generate placental tissues that retained maternal p28-GFP expression only (III., p28-GFPM) or expressed both maternal- and fetal-derived p28-GFP (IV., p28-GFPFM). Created in BioRender. Jurado, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/lkflcs6. C Representative immunofluorescent image of an uninfected p28-GFPF placenta at E13.5 of gestation. Yolk sac (Ys), labyrinth (Lb), junctional zone (Jz), and maternal decidua (Dc) regions were determined via immunofluorescence staining of endothelial cells (CD31; white) and nuclei (DAPI; blue). 20X magnification, stitched. Scale bar, 1000 μm. Image shown is representative of experiments repeated independently in >4 p28-GFPF placentas from separate litters. D Representative immunofluorescent images of p28-GFP within uninfected murine deciduas at E13.5. 10 μm placental cross-sections were obtained for all conditions in Fig. 3B and stained with anti-GFP (green) and DAPI (blue). Images representative of 4 placentas per condition. 20X magnification, zoomed. Scale bar 100 μm. E Quantification of total p28-GFP signal area (microns2) in decidua and labyrinth regions of uninfected placentas, as determined by ImageJ software. Graph represents measurements from 2-4 independent placentas per group, with 3-4 cross-sections obtained per placenta, and 4-8 images acquired per cross-section (Decidua: p28-GFPnull n = 42, p28-GFPF n = 59, p28-GFPM n = 53, p28-GFPFM n = 69; Labyrinth: p28-GFPnull n = 45, p28-GFPF n = 66, p28-GFPM n = 53, p28-GFPFM n = 68). Statistical analysis performed with Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (Decidua from left, p = <0.0001, <0.0001, <0.0001, 0.0136, >0.9999, <0.0001; Labyrinth from left, p = <0.0001, 0.0006, 0.0342, >0.9999, 0.3100, 0.8862). Data presented as mean values ± SD.

IL-27 limits pathologic fetal outcomes during congenital infection

We observed that IL-27 regulates ZIKV infection in human trophoblasts in vitro, therefore we next sought to determine how placental IL-27 signaling influences pregnancy outcomes during broad inflammation and viral infection in vivo. To test this, we utilized immunocompetent human STAT2 knock-in (hSTAT2 KI) mice, and hSTAT2 KI*IL27RA−/− (IL27RA−/−) mice as a genetic disruption of IL-27 signaling29. First, to test how IL-27 signaling influences outcomes to broad maternal inflammation, we challenged pregnant dams with high molecular weight polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (HMW poly(I:C)), a synthetic double-stranded RNA and viral mimetic to trigger nonspecific antiviral immune responses in the absence of active viral replication30. We administered 20 mg/kg HMW poly(I:C) or PBS to pregnant hSTAT2 KI and IL27RA−/− dams via intraperitoneal injection at E6.5. All dams were then euthanized at E13.5, a timepoint equivalent to the second trimester in humans, and fetal and placental tissues were collected for gross morphological analysis (Fig. 4A). Importantly, we detected increased serum IL-6 levels in the HMW poly(I:C)-treated dams at 6 h post-injection, indicating robust maternal immune activation as expected (Fig. 4B). We then assessed fetal outcomes at the time of harvest, determining “healthy”, “early resorption”, or “total resorption” phenotypes for each fetus based on gross morphology and integrity of tissues, and quantified the proportion of fetal outcomes for each condition (Fig. 4C-D). We observed that HWM poly(I:C)-stimulation of pregnant hSTAT2 KI mice resulted in some pathologic fetal outcomes (10.7% total resorption), however, this incidence was not significantly different in the absence of IL-27 signaling (3.6% early resorption, 10.7% total resorption), suggesting that IL-27 signaling does not protect against fetal pathology during broad maternal immune activation in pregnancy (Fig. 4C).

A Timeline for mating and treatment of human STAT2 knock-in (hSTAT2 KI) mice with high molecular weight polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (HMW poly(I:C)). Created in BioRender. Jurado, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/eegilr9. B Serum IL-6 levels in PBS- and HMW Poly(I:C)-treated dams at 6 h post-injection as determined via ELISA. n = 3 dams per group. Statistical analysis performed via ordinary two-way ANOVA, **p < 0.01, ns= not significant (From left, p = >0.9999, 0.0013, 0.0011, 0.9896). Data presented as mean values ± SD. C Proportion of fetuses exhibiting healthy, early resorption, or total resorption phenotypes at E13.5 in PBS- and HMW Poly(I:C)-treated dams. Graph displays total number of fetuses from 3-4 litters per condition. D Representative images depicting fetal outcomes at E13.5. Phenotypes were determined for each fetus based on gross morphology and tissue integrity, as described in methods. E Timeline for mating and infection of hSTAT2 KI mice, as described in methods. Created in BioRender. Jurado, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/m1xcoc2. F Proportion of fetuses exhibiting healthy, early resorption, or total resorption phenotypes at E13.5 in PBS- and ZIKV-infected dams. Fetal outcomes were evaluated in 3 independent litters for all conditions except ZIKV-infected IL27RA−/− dams, for which 4 independent litters were evaluated. Graph displays total number of fetuses per condition. G–I ZIKV burdens at E13.5 as determined via quantitative RT-PCR. G Combined ZIKV burden of one matching fetus and placenta, normalized to combined tissue weight. Shape of data point represents observed fetal phenotype. Total number of fetal/placental units per condition plotted (see 4 F). Statistical analysis performed via Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, ***p < 0.001, ns=not significant (From left, p = >0.9999, 0.0006). H Left: Fetal ZIKV burdens, normalized to fetus weights. Viral burdens for subset of fetuses exhibiting “healthy” phenotypes plotted (Isotype n = 24, α-IL-27 n = 16, IL27RA−/− n = 28). Right: Placental ZIKV burdens, normalized to placental weights. Viral burdens of placentas matched to fetuses with “healthy” phenotypes plotted (Isotype n = 24, α-IL-27 n = 16, IL27RA−/− n = 28). Statistical analysis performed via Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns=not significant (Fetal from left, p = >0.9999, 0.0374; Placental from left, p = 0.0378, <0.0001). I Maternal serum ZIKV burdens, normalized to serum weight. n = 3 dams for Isotype and α-IL-27-treated groups, n = 4 IL27RA−/− dams. Not significant via Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA.

We next aimed to define how placental IL-27 signaling influences congenital viral infection. We obtained IL-27-deficient mice via antibody neutralization or genetic disruption of IL-27 signaling. For antibody neutralization, pregnant hSTAT2 KI dams were administered α-IL-27 or isotype control antibody via intraperitoneal injection beginning early in gestation and infected with mouse-adapted DAKAR ZIKV at E6.5 via footpad injection29. As a genetic disruption of IL-27 signaling, pregnant IL27RA−/− dams were also infected with mouse-adapted ZIKV at E6.5. Dams were euthanized at E13.5 and maternal serum, placentas, and fetuses were collected for further analysis (Fig. 4E). In the absence of infection, the fetuses of IL-27-neutralized and IL27RA−/− dams exhibited healthy outcomes and no observable pathology at E13.5 (Fig. 4F). During congenital ZIKV infection, a small proportion of early resorption phenotypes were observed in the fetuses of isotype control-treated dams at E13.5 (7.7%; Fig. 4F). However, there was a significantly greater incidence of resorption in the fetuses of IL-27-neutralized (28% total resorption; 8% early resorption) and IL27RA−/− (23.1% total resorption; 5.1% early resorption) dams during congenital ZIKV infection (Fig. 4F, Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 3).

We next measured ZIKV RNA levels in the fetuses, placentas, and maternal serum via quantitative RT-PCR. To include all fetuses in our analysis of viral burden, including those exhibiting the “total resorption” phenotype that prevents accurate separation of the placenta and fetus, we first evaluated the combined fetal and placental ZIKV burdens for each conceptus. We observed significantly higher ZIKV burdens in the combined fetal/placental tissues from IL27RA−/− dams, suggesting that IL-27 may play a role in limiting ZIKV infection at the maternal-fetal interface (Fig. 4G). When considering the intact fetuses alone, we found no significant difference in ZIKV burdens in the fetuses of control, IL-27-neutralized, and IL27RA−/− dams, suggesting that fetal pathology is independent of ZIKV burden (Fig. 4H). Interestingly, we observed significantly higher ZIKV burdens in the placentas of IL-27-neutralized and IL27RA−/− dams relative to control placentas (Fig. 4H). Finally, we found that the fetal pathology phenotypes were not driven by maternal ZIKV burdens, as the viral RNA was effectively cleared in the maternal serum as expected (Fig. 4I). Collectively, these data indicate that IL-27 signaling is required to prevent fetal pathology and can restrict viral RNA replication in placental tissues during congenital ZIKV infection.

Discussion

With this study, we sought to dive into the complex cytokine signaling mechanisms that facilitate immunological crosstalk between mother and fetus in the placenta and explore the previously uncharacterized role of placental IL-27 signaling. Using a primary human trophoblast organoid model, we found that IL-27 signaling machinery is expressed by fetal trophoblasts, and that IL-27 is capable of restricting ZIKV infection of trophoblasts (Fig. 1). Type III IFNs are a known family of antiviral cytokines produced by the placenta that have been shown to limit ZIKV infection of trophoblasts through antiviral gene expression mediated by autocrine signaling10,11,12. Notably, our GSEA analysis of bulk RNA-sequencing data revealed similar transcriptional profiles of IL-27- and IFNλ-stimulated trophoblast organoids, with overlapping changes in antiviral gene expression, albeit to differing degrees (Fig. 2). These findings underscore the numerous lines of defense that contribute to the robust antiviral state of the placenta during gestation.

IL-27 and IFNλ signaling interplay has been previously described in other contexts, with one study finding that IL-27 can drive IFNλ activation in virus-infected liver cells31. To directly investigate cytokine signaling interplay in trophoblasts during congenital infection, we infected TOs with ZIKV in the absence of both IL-27 and IFNλ. In the absence of both cytokines, we observed higher viral burdens and lower expression of antiviral genes IFIT1, MX1, and PARP9 compared to in the absence of IFNλ or IL-27 alone (Fig. 2). These findings support the paradigm of IL-27 and IFNλ crosstalk at the maternal-fetal interface during congenital viral infection, which we hypothesize could be due to either differential effector activity of IL-27 and IFNλ, or due to one cytokine regulating the other. One current limitation of our studies comes from the ability to capture an unstimulated TO state, due to constitutive cytokine production in primary trophoblast organoids (Fig. 1). Genetic manipulation of TO lines has been a technical challenge due to their derivation from primary human tissues; however, ongoing studies are pioneering methods for the genetic modification of TO lines which would allow for further dissection of the antiviral signaling interplay of these two cytokine families in trophoblasts in vitro.

In both humans and experimental mouse models, there are reports of twin discordance during congenital ZIKV infection32,33. Consistent with this, we observed differential ZIKV burdens and magnitudes of change following cytokine neutralization across TOs isolated from two separate donor placentas (Figs. 1, 2, Supplementary Fig. 3). Similarly, we observed significant variability in both the range of fetal viral burdens and infection outcomes in our murine model of congenital ZIKV infection (Fig. 4). We speculate that the variability observed in our TO and murine models is due to host background and differences at the genetic and epigenetic level that could influence basal immune responses in the placenta. This concept is supported by our data showing that TOs isolated from two independent donors exhibited differential expression of antiviral genes IFIT1 and OAS2 in the basal state (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3). Given the potential consequences of basal cytokine dynamics in the placenta to congenital viral infections, this variability should be further explored in future studies.

In our murine model of congenital ZIKV infection, we observed that IL-27 signaling restricted placental ZIKV burdens and was protective against pathologic fetal outcomes indicating that IL-27 was critical to infection at gestational day E6.5 (Fig. 4). Curiously, one study suggests that placental IFNλ signaling has both protective and pathogenic effects during murine congenital ZIKV infection, depending on the gestational timepoint34. When pregnant dams were challenged with infection early in pregnancy (E7) IFNλ was pathogenic, whereas IFNλ was protective against infection later in pregnancy (E.9)34. Future studies are needed to explore the possibility of gestational-age dependent effects of IL-27 signaling during congenital murine ZIKV infection. Additionally, it is possible that IFNλ and IL-27 are functioning with varying mechanisms at the maternal-fetal interface during different timepoints of gestation. Future studies could elucidate the interplay of IL-27 and IFNλ signaling at mid-gestation, and their distinct and shared contributions to protective antiviral immunity.

Though our study primarily explores the consequences of IL-27 signaling in placental trophoblasts, the placenta and decidua are both comprised of diverse cellular immune components, with many IL-27-responsive immune cells present in these tissues. For example, T cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, B cells and dendritic cells are all present at the maternal-fetal interface beginning early in gestation and play a key role in mediating a healthy pregnancy6,35. IL-27 is known to potently regulate each of these subsets beyond the context of pregnancy, and prior studies show that IL-27 broadly restricts CD4 + T cells and dampens Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell-mediated pathology during acute respiratory viral infections36,37,38,39. Yet, it remains unclear how IL-27 signaling contributes to immune cell regulation at the maternal-fetal interface. We observed increased tissue pathology in the fetuses of IL-27 deficient dams during congenital ZIKV infection, but not in the fetuses of IL-27-deficient dams treated with HMW poly(I:C) (Fig. 4); however, these experiments did not explore the possibility of IL-27 regulating immune cell-mediated pathology. Thus, the role of IL-27 in regulating immune cell activity specifically during congenital ZIKV infection warrants further investigation.

Collectively, our work provides new insight into the functional role of IL-27 at the maternal-fetal interface and identifies IL-27 as a protective antiviral cytokine in the placenta. IL-27 has distinct protective roles in the context of other viral and microbial infections such as HIV−1, Influenza A virus (IAV), and Toxoplasma gondii, however this study is the first to demonstrate protective IL-27 activity at the maternal-fetal interface22,38,40,41,42,43. Given our use of ZIKV as a model of congenital infection, future studies are needed to evaluate whether placental IL-27 signaling broadly contributes to protective immunity against other congenital pathogens such as Cytomegalovirus, Toxoplasma gondii, and Listeria monocytogenes. In addition to ZIKV, there are many other emerging and re-emerging viruses that pose a major threat to global health and to highly susceptible populations such as pregnant individuals and developing fetuses. We show that IL-27 signaling basally induces antiviral gene (IFIT1, MX1, OAS2) expression and viral regulation pathways in fetal trophoblasts (Fig. 2), thus suggesting possible mechanisms through which IL-27 signaling could restrict other viruses known to infect fetal trophoblasts such as Rift Valley Fever virus, and recently emerging viruses with the capacitary for congenital infection, such as Oropouche virus44,45,46,47,48. Finally, our study highlights therapeutic potential for IL-27 in the context of pregnancy and congenital infection. Recent studies have demonstrated the ability to specifically deliver mRNA to the placenta through ionizable lipid nanoparticle (LNP) technology to treat placental disorders such as pre-eclampsia49. Future investigations could focus on applying the cutting-edge mRNA-LNP platform to effectively deliver IL-27 to the placenta and enhance antiviral responses in vivo.

Methods

Human placental tissue samples

Placental villi and decidua were obtained from first trimester (6-12 post-conception weeks) pregnancy terminations performed at the University of Pennsylvania Family and Pregnancy Loss Center (IRB#827072). All subjects were counseled appropriately and provided written informed consent. Patients with preexisting medical conditions, pregnancy complications, or maternal infection were excluded from the study. Collected tissues were stored on ice and organoid derivation was carried out within 1 h of procurement. Information about donor tissues is detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Derivation and culture of trophoblast and decidual organoids

Primary trophoblast organoid (TO) and decidual organoid (DO) cultures were derived from first trimester placental tissues following methods previously established by Turco et al.17,18,19. Briefly, placental villi and decidual tissues were separated and washed in Ham’s/F12 media (Corning, MT10-080-CV) supplemented with 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (ThermoFisher, 15140122) to remove blood. Villous tissues were scraped with a scalpel and enzymatically digested to isolate villous trophoblast stem/progenitor cells, while decidual tissues were minced with a scalpel and enzymatically digested to isolate endometrial gland stem/progenitor cells. TO progenitor cells were seeded in 25 µl Matrigel domes, and plated with 250 µl trophoblast organoid media (TOM) consisting of Advanced DMEM/F12 (ThermoFisher, 12634-010) supplemented with 1x B27 (ThermoFisher, 17504-044), 1x N2 (ThermoFisher, 17502-048), 2 mM GlutaMAX (ThermoFisher, 35050-061), 100 µg/mL Primocin (InvivoGen, ant-pm-1), 1.25mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, A9165), 5 µM Y-27632 (Sigma-Aldrich, Y0503), 50 ng/mL recombinant human EGF (Peprotech, AF-100-15), 100 ng/mL recombinant human FGF2 (Peprotech, 100-18B), 80 ng/mL recombinant human R-spondin 1 (R&D Systems, 4645-RS-01M/CF), 50 ng/mL recombinant human HGF (Peprotech, 100−39), 1.5 µM CHIR99021 (Tocris, 4423), 500 nM A83-01 (Tocris, 2939), and 2.5 µM Prostaglandin E2 (Tocris, 2296). DO progenitor cells were seeded in 25 µl Matrigel domes, and plated with 250 µl expansion media (ExM) consisting of Advanced DMEM/F12 (ThermoFisher, 12634-010) supplemented with 1x B27 (ThermoFisher, 17504-044), 1x N2 (ThermoFisher, 17502-048), 2 mM GlutaMAX (ThermoFisher, 35050-061), 100 µg/mL Primocin (InvivoGen, ant-pm-1), 1.25 mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, A9165), 50 ng/mL recombinant human EGF (Peprotech, AF-100-15), 100 ng/mL recombinant human FGF2 (Peprotech, 100-18B), 80 ng/mL recombinant human R-spondin 1 (R&D Systems, 4645-RS-01M/CF), 50 ng/mL recombinant human HGF (Peprotech, 100-39), 500 nM A83-01 (Tocris, 2939), 10 mM Nicotinamide (Sigma-Aldrich, N0636), and recombinant human NOGGIN (Peprotech, 120-10 C). TO and DO cultures were routinely passaged every 6-8 days, with full media changes every 2-3 days, and were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. TOs and DOs used in this study were derived from 4 independent placentas (Supplementary Table 1). Sex of placentas and resulting TO lines were determined via quantitative RT-PCR using primers for RPS4Y1 (Taqman, Hs00606158_m1; male placentas) and Xist (Taqman, Hs01079824_m1; female placentas).

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA)

Conditioned media (CM) was collected from TO and DO cultures at 1-, 24-, 48-, and 72-h post-passage. Secreted hCG was detected in organoid CM using One Step Pregnancy Test strips (Accumed, HCG25-PP). CM hCG levels were also measured via hCG ELISA (R&D Systems, DY9034) to validate TO and DO lines prior to experimentation. IL-27 ELISA (R&D Systems, DY2526) was performed according to manufacturer’s protocol using CM from 3-5 replicate TO wells for 3 independent TO donors, and a 2-fold serial dilution standard curve of recombinant human IL-27 plated in technical duplicate. For mouse IL-27 ELISAs, pregnant hSTAT2 KI mice were euthanized at gestational days E9.5, E13.5, and E17.5. Whole placental tissues, including maternal decidua, were collected and homogenized, and a mouse IL-27 p28 ELISA (R&D Systems, M2728) was then performed according to manufacturer’s protocol. Individual placental lysates and a 2-fold serial dilution standard curve of recombinant mouse IL-27 p28 were plated in technical duplicate. To validate maternal immune activation by HMW poly (I:C), an in-house IL-6 ELISA (Biolegend, 504501/504601) was performed on mouse serum samples. Blood was collected from HMW poly(I:C)- and control-treated dams via submandibular (cheek) bleed at 6 h post-treatment, centrifuged to remove cells, and the remaining serum was collected (Sarstedt, 41.1378.005). IL-6 ELISAs were performed using serum from 3-4 dams per group, plated in technical duplicate. A standard curve of recombinant mouse IL-6 (Biolegend, 575702) was prepared according to manufacturer’s instructions and plated in duplicate. All TO and mouse ELISA absorbance readings were determined via plate reader at 450 nm and converted to concentration using Microsoft Excel software.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Murine placentas and TOs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C prior to embedding in OCT (Sakura, 4583) and sectioning (8-10 μm) with a Leica Cryostat. For all immunofluorescence experiments, slides were washed three times with 1x PBS prior to membrane disruption with PBS supplemented with 0.4% Triton X-100 (PBST; Sigma-Aldrich, T8787). All slides were blocked with 2% normal goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich, G9023-5ML) in PBST for one hour at room temperature prior to overnight incubation with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution at 4 °C. Mouse placenta sections were incubated in primary antibodies against GFP (1:200, Invitrogen, A-21311) and PECAM-1/CD31 (1:10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 2H8s), while TO sections were incubated in primary antibodies against IL27RA (1:100, Bioss Antibodies, bs-2711R), SDC1 (1:200, Abcam, ab34164, clone B-A38), and Ki67 (1:50, Invitrogen, 50-5698-82, clone SolA15). Slides were subsequently washed three times with PBST. After washing, slides were incubated with secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and 1x DAPI (ThermoFisher, AC20271010) diluted in PBST for 2 h at room temperature. Following incubation, mouse placenta slides were incubated in TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher (Biotium, 23007) for three minutes at room temperature to reduce background signal intensity. All slides were washed with PBST and covered with mounting media (ThermoFisher, P36961) and a coverslip prior to imaging (Eclipse Ti2, Nikon). Immunofluorescence images were processed using NIS-Elements and ImageJ software. Total area of p28-GFP signal in murine placenta images was quantified using the ImageJ particle count application.

Virus

For TO infections, ZIKV Cambodian FSS13025 strain (ZIKV-CAM) was obtained from the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses at University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. For in vivo infections, mouse-adapted ZIKV DAKAR was obtained from Michael Diamond’s laboratory at Washington University in St. Louis. ZIKV-CAM stocks were propagated in C6/36 mosquito cells (Aedes albopictus) (ATCC, CRL-1660), while ZIKV DAKAR stocks were grown in Vero cells (ATCC, CCL-81). C6/36 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (ThermoFisher, 11965092) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (ThermoFisher, A5670701), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (ThermoFisher, 15140122) and 1% tryptose phosphate broth (Sigma-Aldrich, T8159) at 30 °C. Vero cells were maintained at 37 °C in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cell lines were authenticated by morphology and were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination. For high-titer doses, ZIKV was concentrated by ultrafiltration (Centricon Plus-70; MWCO: 30,000).

Trophoblast organoid infection and stimulation

Prior to all TO experiments, TOs were routinely passaged and plated in Matrigel. For TO infections, TOs were treated with either isotype control (10ug/mL AB-108-C, R&D; 8ug/mL MAB003, clone 20102, R&D), 10μg/mL α-IL-27 (R&D, AF2526) or 4μg/mL α-IFNλ1 (R&D, MAB15981, clone 247801) and 4μg/mL α-IFNλ3 (R&D, MAB5259, clone 567143) antibodies in fresh TOM at days 3 and 5 post-passage. At day 5 post-passage, TOs were removed from Matrigel domes and infected with 105 PFU ZIKV-CAM or PBS in fresh TOM at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 2 h. After 2 h, virus was washed from TO cultures and replaced with fresh TOM and antibodies. At 24 h post-infection, RNA was isolated from organoids and ZIKV burdens were determined via quantitative RT-PCR. Schematic of TO infection timeline included in Supplementary Fig. 2. For Fig. 2B, C, Isotype-treated TOs were administered PBS and isotype control antibody (10ug/mL AB-108-C, R&D; 8 ug/mL MAB003, clone 20102, R&D) in fresh TOM at days 3 and 5 post-passage. Rux-treated TOs were administered 20 μM Ruxolitinib (Stem cell, 73404) and isotype control antibody in fresh TOM at days 3 and 5 post-passage. IFNλ and IL-27-treated TOs were treated with 10 μg/mL α-IL-27 (R&D, AF2526) or 4 μg/mL α-IFNλ1 (R&D, MAB15981, clone 247801) and 4μg/mL α-IFNλ3 (R&D, MAB5259, clone 567143) antibodies in fresh TOM at days 3 and 5 post-passage. At day 5 post-passage, IFNλ and IL-27-treated TO cultures were then stimulated with 100 ng/mL each of recombinant human IFNλ1 (R&D, 1598-IL-025/CF) and recombinant human IFNλ3 (R&D, 5259-IL-025/CF), or 500 ng/mL recombinant human IL-27 (Peprotech, 200-38) in fresh TOM, respectively. At 24 h post-stimulation, all organoids were collected for RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR. For bulk RNA sequencing experiments, TOs were treated with either isotype control 10 μg/mL α-IL-27 or 4μg/mL α-IFNλ1 and 4 μg/mL α-IFNλ3 antibodies in fresh TOM at days 3 and 5 post-passage. At day 5 post-passage, additional TO cultures were stimulated with either vehicle control (PBS), 100 ng/mL each of recombinant human IFNλ1 and IFNλ3, or 500 ng/mL recombinant human IL-27 in fresh TOM. At day 6 post-passage, all organoids were collected for RNA isolation and sequencing.

RNA extraction, cDNA generation, and quantitative RT-PCR

TOs and DOs were collected at 6-8 days post-passage for RNA analysis, depending on their size and density. To ensure RNA yield, 2-4 Matrigel domes containing organoids from a single donor were pooled in 400 µl TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596026) for RNA analysis. Organoid RNA was purified via phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, using Phase Lock Gel Heavy tubes (QuantaBio, 2302830) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality and concentration were determined using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Nanodrop One spectrophotometer. Total RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A25742) and human gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 4). All samples were run in technical duplicate on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System. Gene expression of p28, EBI3, WSX1, and gp130 were determined based relative to housekeeping gene HPRT1 expression (ΔCT method). For TO infections, ZIKV E expression was normalized to the isotype internal reference via the ΔΔCT method.

For RNA extraction and quantification of murine viral loads, tissues were collected in 600μl TRIzol reagent and homogenized (MP Biomedical, 116004500). Homogenates were then centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 × g, and 100 μl of the clarified homogenate was then diluted with 300 μl TRIzol. An equal volume of 100% ethanol was then added to the diluted sample for RNA extraction. Viral RNA was extracted using a Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research, R2050) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription and quantitative RT-PCR were performed as described above using mouse gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 4). ZIKV genome equivalents were determined via a 100-fold serially diluted standard curve of ZIKV RNA extracted from viral stock. Total ZIKV genome equivalents per tissue were then standardized to the tissue weight in mg.

Plaque assay

Supernatant was collected from infected TO cultures at 1-, 24-, and 48-h post-infection (hpi), followed by serial dilution in DMEM (Corning, 10-013-CV) supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (Sigma-Aldrich, F2442) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (ThermoFisher, 15140122). For plaque assays, Vero cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well in a 6-well plate overnight. After 24 h, seeded Vero cells were treated with 250 μL of diluted TO supernatants and incubated for 1-h, with rotations every 15 min. Following incubation, inoculum was aspirated and replaced with MEM (Sigma-Aldrich, 11430030) supplemented with 5% FBS, 1% GlutaMAX, 1% Non-essential amino acids, and 0.65% agarose (Lonza, 50111). ZIKV-infected cells were fixed at 6 days post-infection with 2 mL 10% NBF (ThermoFisher, 22050105) and visualized using 0.1% crystal violet (ThermoFisher, C581-25). Plaques were manually counted, and virus titer was calculated.

Bulk RNA-sequencing

RNA was isolated from TOs for bulk RNA-sequencing using the Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research, R2050) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was then processed for bulk RNA-sequencing at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia High Throughput Sequencing Core. Sequencing libraries were prepared using Illumina’s stranded total RNA Prep kit with Ribo-Zero and the NovaSeq 6000 SP Reagent Kit v1.5 (200 cycles) (Illumina, #20040719). All data were analyzed using an adapted form of the open-source DIY transcriptomics lecture materials50. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of bulk RNA sequencing data was performed for IL-27- and IFNλ-stimulated TOs. Log fold-change values were calculated by comparing IL-27-stimulated vs. α-IL-27 TOs and IFNλ-stimulated vs. α-IFNλ TOs. All GSEA analyses were then evaluated using a log fold-change cutoff value > 0.5. GSEA significance was determined via permutation testing with two-sided p-values, and Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction. GSEA analysis described in Supplementary Data.

Mice

Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Strain #000664). Human STAT2 knock-in (hSTAT2 KI) mice (Gorman et. al. 2018) were obtained from Michael Diamond’s laboratory at Washington University in St. Louis. p28-GFP mice were obtained from Ross Kedl’s laboratory at the University of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus. All mice were maintained at the University of Pennsylvania under specific pathogen free conditions, on a 12-h light/dark cycle, at 21 °C (±1 °C) and 50% (±10%) humidity. All experiments were performed in adherence to the University of Pennsylvania’s approved IACUC protocol (#806749). All timed mating experiments utilized adult (8–15 week) male and female mice. Mouse genotypes were determined using DNA extracted from maternal tail samples or fetal yolk sacs and previously described primers (Supplementary Table 4)27,29.

In vivo infections

Beginning at embryonic day 3.5 (E3.5), pregnant hSTAT2 KI dams were administered 500μg of α-IL-27 (BioXCell, BE0326, clone MM27.7B1) or isotype control (BioXCell, BE0085, clone C1.18.4) antibody via intraperitoneal injection, with subsequent treatments every three days (E6.5, E9.5, and E12.5). At E6.5, the control and IL-27-neutralized dams were then infected with 6.75 × 105 PFUs mouse-adapted DAKAR ZIKV diluted in PBS via footpad injection. To mimic immune activation during viral infection, High Molecular Weight (HMW) Vaccigrade Poly(I:C) (Invivogen, vac-pic) was delivered to pregnant mice at E6.5 via intraperitoneal injection at 20 mg/kg. All infected and HMW poly(I:C)-stimulated dams were euthanized at E13.5 and fetal, placental, and maternal tissues were collected for further analyses. Gross morphology of fetal and placental tissues were assessed upon collection. Intact embryos lacking any visible signs of pathology were characterized as “healthy.” Embryos with a distinguishable fetus and placenta but some loss in tissue integrity were characterized as “early resorption.” Visibly smaller embryos that lacked a clearly defined fetus and placenta due to hemorrhage and tissue necrosis were characterized as “total resorption.” All mouse infection and stimulation data are representative of 3-4 litters per treatment group.

Statistical analysis

Bulk RNA-sequencing data were analyzed in R studio using DIY transcriptomics lecture materials50. All graphs were plotted and statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism software. Horizontal dashed lines are used on graphs to denote limits of detection (LOD) for the given assay. All data are expressed as mean+/− standard deviation (SD) or error of mean (SEM). Exact statistical test and number of biological samples (n) are detailed in the figure legends. A one-way ANOVA was used to determine significance when determining significance between multiple groups (>3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns= not significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Primary RNA-sequencing data generated in this study are deposited and available under GEO accession number (GSE298278). Source data are included with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All original code for this study is publicly available via GitHub at https://github.com/amsesk/Merlino2025_IL27_ZIKV/tree/revision1 and has been deposited in Zenodo Repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17701386)51.

References

Megli, C. J. & Coyne, C. B. Infections at the maternal–fetal interface: an overview of pathogenesis and defence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 67–82 (2021).

Coyne, C. B. & Lazear, H. M. Zika virus—reigniting the TORCH. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 707–715 (2016).

França, G. V. A. et al. Congenital Zika virus syndrome in Brazil: a case series of the first 1501 livebirths with complete investigation. Lancet 388, 891–897 (2016).

Bhatnagar, J. et al. Zika virus RNA replication and persistence in brain and placental tissue. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 405–414 (2017).

Hoen, B. et al. Pregnancy outcomes after ZIKV infection in French territories in the Americas. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 985–994 (2018).

Ander, S. E., Diamond, M. S. & Coyne, C. B. Immune responses at the maternal-fetal interface. Sci. Immunol. 4, eaat6114 (2019).

Sadler, A. J. & Williams, B. R. G. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 559–568 (2008).

Yockey, L. J. et al. Type I interferons instigate fetal demise after Zika virus infection. Sci. Immunol. 3, eaao1680 (2018).

Casazza, R. L., Lazear, H. M. & Miner, J. J. Protective and pathogenic effects of interferon signaling during pregnancy. Viral Immunol. 33, 3–11 (2020).

Bayer, A. et al. Type III interferons produced by human placental trophoblasts confer protection against Zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 19, 705–712 (2016).

Corry, J., Arora, N., Good, C. A., Sadovsky, Y. & Coyne, C. B. Organotypic models of type III interferon-mediated protection from Zika virus infections at the maternal–fetal interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9433–9438 (2017).

Jagger, B. W. et al. Gestational stage and IFN-λ signaling regulate ZIKV infection In Utero. Cell Host Microbe 22, 366–376.e3 (2017).

Coulomb-L’Herminé, A. et al. Expression of interleukin-27 by human trophoblast cells. Placenta 28, 1133–1140 (2007).

Hunter, C. A. & Kastelein, R. Interleukin-27: balancing protective and pathological immunity. Immunity 37, 960–969 (2012).

Yoshida, H. & Hunter, C. A. The immunobiology of interleukin-27. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 33, 417–443 (2015).

Kwock, J. T. et al. IL-27 signaling activates skin cells to induce innate antiviral proteins and protects against Zika virus infection. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay3245 (2020).

Turco, M. Y. et al. Long-term, hormone-responsive organoid cultures of human endometrium in a chemically-defined medium. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 568–577 (2017).

Turco, M. Y. et al. Trophoblast organoids as a model for maternal–fetal interactions during human placentation. Nature 564, 263–267 (2018).

Sheridan, M. A. et al. Establishment and differentiation of long-term trophoblast organoid cultures from the human placenta. Nat. Protoc. 15, 3441–3463 (2020).

Co, J. Y. et al. Controlling epithelial polarity: a human enteroid model for host-pathogen interactions. Cell Rep. 26, 2509–2520.e4 (2019).

Yang, L. et al. Innate immune signaling in trophoblast and decidua organoids defines differential antiviral defenses at the maternal-fetal interface. eLife 11, e79794 (2022).

Valdés-López, J. F. et al. Interleukin 27, like interferons, activates JAK-STAT signaling and promotes pro-inflammatory and antiviral states that interfere with dengue and chikungunya viruses replication in human macrophages. Front. Immunol. 15, 1385473 (2024).

Diamond, M. & Farzan, M. The broad-spectrum antiviral functions of IFIT and IFITM proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 46–57 (2013).

Strange, D. P. et al. Paracrine IFN response limits ZIKV infection in human sertoli cells. Front. Microbiol. 12, 667146 (2021).

Xing, J. et al. Identification of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 9 (PARP9) as a noncanonical sensor for RNA virus in dendritic cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 2681 (2021).

Parthasarathy, S. et al. PARP14 is an interferon-induced host factor that promotes IFN production and affects the replication of multiple viruses. mBio 16, e02299-25 (2025).

Kilgore, A. M. et al. IL-27p28 Production by XCR1+ Dendritic Cells and Monocytes Effectively Predicts Adjuvant-Elicited CD8+ T Cell Responses. ImmunoHorizons 2, 1–11 (2018).

Soncin, F., Natale, D. & Parast, M. M. Signaling pathways in mouse and human trophoblast differentiation: a comparative review. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 72, 1291–1302 (2014).

Gorman, M. J. et al. An immunocompetent mouse model of zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 23, 672–685.e6 (2018).

Hameete, B. C. et al. The poly(I:C)-induced maternal immune activation model; a systematic review and meta-analysis of cytokine levels in the offspring. Brain Behav. Immun. - Health 11, 100192 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. IL-27, a cytokine, and IFN-λ1, a Type III IFN, are coordinated to regulate virus replication through type I IFN. J. Immunol. 192, 691–703 (2014).

Cugola, F. et al. The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature 534, 267–271 (2016).

Caires-Júnior, L. C. et al. Discordant congenital Zika syndrome twins show differential in vitro viral susceptibility of neural progenitor cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 475 (2018).

Casazza, R. L., Philip, D. T. & Lazear, H. M. Interferon lambda signals in maternal tissues to exert protective and pathogenic effects in a gestational stage-dependent manner. mBio 13, e03857–21 (2022).

Vento-Tormo, R. et al. Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal–fetal interface in humans. Nature 563, 347–353 (2018).

Villarino, A. V. et al. Positive and negative regulation of the IL-27 receptor during lymphoid cell activation. J. Immunol. 174, 7684–7691 (2005).

Findlay, E. G. et al. Essential Role for IL-27 receptor signaling in prevention of Th1-mediated immunopathology during malaria infection. J. Immunol. 185, 2482–2492 (2010).

Liu, F. D. M. et al. Timed action of IL-27 protects from immunopathology while preserving defense in influenza. PLOS Pathog. 10, e1004110 (2014).

Muallem, G. et al. IL-27 Limits Type 2 immunopathology following parainfluenza virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006173 (2017).

Dai, L. et al. IL-27 inhibits HIV-1 infection in human macrophages by down-regulating host factor SPTBN1 during monocyte to macrophage differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 210, 517–534 (2013).

Swaminathan, S., Dai, L., Lane, H. C. & Imamichi, T. Evaluating the potential of IL-27 as a novel therapeutic agent in HIV-1 infection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 24, 571–577 (2013).

Villarino, A. et al. The IL-27R (WSX-1) is required to suppress T cell hyperactivity during infection. Immunity 19, 645–655 (2003).

Aldridge, D. L. et al. Endogenous IL-27 during toxoplasmosis limits early monocyte responses and their inflammatory activation by pathological T cells. mBio 15, e00083-24.

McMillen, C. M. et al. Rift Valley fever virus induces fetal demise in Sprague-Dawley rats through direct placental infection. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau9812 (2018).

Oymans, J., Wichgers Schreur, P. J., van Keulen, L., Kant, J. & Kortekaas, J. Rift Valley fever virus targets the maternal-foetal interface in ovine and human placentas. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0007898 (2020).

McMillen, C. M. & Hartman, A. L. Rift valley fever: a threat to pregnant women hiding in plain sight? J. Virol. 95, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01394-19 (2021).

Megli, C. et al. Oropouche virus infects human trophoblasts and placenta explants. Nat. Commun. 16, 6040 (2025).

Schwartz, D. A., Dashraath, P. & Baud, D. Oropouche virus (OROV) in pregnancy: an emerging cause of placental and fetal infection associated with stillbirth and microcephaly following vertical transmission. Viruses 16, 1435 (2024).

Swingle, K. L. et al. Placenta-tropic VEGF mRNA lipid nanoparticles ameliorate murine pre-eclampsia. Nature 637, 412–421 (2025).

Berry, A. S. F. et al. An open-source toolkit to expand bioinformatics training in infectious diseases. mBio 12, e0121421 (2021).

Amses, K. amsesk/Merlino2025_IL27_ZIKV: revision 1 (Version revision1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17701386 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Michael Diamond from Washington University in St. Louis, MO, USA for providing the mouse adapted Zika DAKAR virus; Dr. Daniel Beiting at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA for assistance with bulk RNA sequencing analyses; Dr. Kevin R. Amses at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA for assistance with biostatistical analyses; the High Throughput Sequencing (HTS) Core at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), PA, USA for assistance with bulk RNA sequencing experiments. This work was in part supported by the National Institutes of Health 1R01AI180138-01 (KAJ), National Institutes of Health R01 AI157247 (CAH), the University of Pennsylvania Cell and Molecular Biology Training Grant T32 GM-07229 (MSM), and the National Institutes of Health IRACDA fellowship K12GM081259 (RLC). Additional funding provided by the Linda Pechenik Montague Investigator Award and the Pew Charitable Trusts Biomedical Scholars Program (KAJ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.M.: study conceptualization, study design, methodology, experimental work, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. B.B.: study design, experimental work and data interpretation. S.G.N.: methodology, RNA-sequencing data and bioinformatic analysis, manuscript review and editing. D.T.P.: study design, experimental work and data interpretation. R.L.C.: methodology, manuscript review and editing. T.M-E.: methodology, manuscript review and editing. A.H.L.: methodology. S.M.: methodology. M.N.M.: study design, resources, and manuscript review. C.A.H.: study design, manuscript review and editing. K.A.J.: funding acquisition, study conceptualization, study design, methodology, manuscript writing, resources and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Cheng-Feng Qin, Michael Gale, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Merlino, M.S., Barksdale, B., Negatu, S.G. et al. Interleukin-27 is antiviral against Zika virus at the maternal-fetal interface. Nat Commun 17, 652 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67378-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67378-0