Abstract

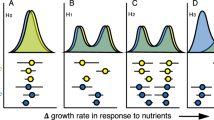

Acid stress is a central environmental factor shaping the structure and function of microbial communities worldwide. However, there is a lack of predictive understanding of how microbial communities respond physiologically and metabolically to acid stress. Here, we find that higher acid stress favors slower-growing species, promoting population growth and coexistence. Our experiments show that acid stress influences the spatial structure of communities, wherein coexistence is ordered over centimeter-length scales and determined by growth-tolerance trade-offs. We find that interspecific interactions are highly dynamic during acid stress changes, with shifts from competition to cooperation, enhancing resilience under high-stress intensities. Slower-growing species may bolster interspecific coexistence through stress-dependent excretion and cross-feeding of public goods. We construct a resource-consumer-based mathematical model to unravel the processes experienced by species in stress-induced coexistence and their distinct physiological states. Finally, our pairwise bacterial-fungal interaction experiments elucidate universalities in stress-induced coexistence between closely related and phylogenetically distant species with complementary phenotypic profiles. Overall, our work provides insights into how acid stress affects physiological and metabolic responses, as well as overall fitness, resilience, and coexistence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbial communities are ubiquitous in nature, shaped by intricate interactions among cohabitating species and their environments1,2,3. Synergistic interactions between different species perform advanced functions that surpass the capabilities of individual species alone4,5,6, such as food fermentation7,8, pollutant degradation9,10, and element cycling11. Understanding these interactions will help us decode the operating principles that support and sustain the stability and sustainability of microbial communities. Acid stress is a key environmental variable, shaping microbial community composition7,12. However, aside from the direct effects of acid stress itself, scant attention has been paid to how acid stress changes affect microbial dynamics, including colonization, growth, metabolism, and interactions, especially in complex communities. As global acidification intensifies, altering microbial community structure and stability13,14, it is of paramount importance to untangle the physiological and metabolic responses of microbial communities to environmental acidification and to determine whether there are general principles that can be used to explain these changes.

Although the specific effects of acid stress on microbial communities’ physiological and metabolic processes remain unclear, many investigations of culture-independent omics data in recent years can be used to characterize communities affected by acid stress. In the oceans, for example, profound cyclic variations in community structure are associated with seasonal and long-term acidity changes15,16. Variation in acid stress also drives the quality dynamics of microbially fermented foods, as both microbial diversity and metabolic function shift with varying acid stress7,17. Changes in bacterial community structure and function have also been observed in soils subject to acid stress changes12,18, with potentially important implications for biochemical cycling in a globally acidified environment. Moreover, in the animal gut, acid stress changes can lead to alterations in the structure and function of the gut/host microbiome, thereby affecting health and mood19,20. Thus, acid stress significantly influences ecological processes that control community structure and function.

One mechanism by which environmental change affects community structure and function is through regulating the types of interactions between microorganisms (e.g., competition, cooperation, etc.)21,22. These changes can alter the spatial arrangement of species in the community23,24,25,26. Importantly, these arrangements are determinants of community-level properties and specific behaviors, such as the metabolic processes of the microbial community, the resistance of the microbial community to invasive strains, its resilience to environmental stresses, and the evolution of microbial interactions27,28,29,30. Nevertheless, competitive interactions remain the dominant interaction type observed in studies27,28,29,30. Without a broad understanding of the physiological and metabolic responses of species within the community, it is impossible to determine whether species and communities can be favored in the face of environmental change, especially increasing environmental stress. In particular, few reports have specifically examined the effects of acid stress changes on the outcome of cooperation between microbial species. A small number of studies of synthetic communities and mathematical modeling have shown that microbial communities may cooperate and co-exist when enhanced environmental stress causes another species’ decline23,29. However, the universality of these findings is limited without taking into consideration dynamic feedbacks23,30, making it difficult to assess the natural behaviors of microbial communities. Little is known about how acid stress changes affect colonization, growth, metabolism, and interactions of free-living microbial communities and whether increased stress promotes microbial cooperation.

In this study, we investigate how lactate, produced by lactic acid bacteria (LAB), serves as a prevalent, natural acid stressor31,32. We simulate acid stress changes in many environments, ranging from gut and fermented substrates to soil and oceans, by lactate diffusion over time on multi-microwell agar plates, thus constructing dynamic feedbacks involving interactions within and between species, and with the environment. Specifically, this study systematically examines the growth dynamics, interaction, and stress-tolerant mechanisms of free-living co-cultured communities in response to acid stress using physiology, metabolomics, phenotypic analysis, and mathematical modeling. Our results reveal how the ecological outcomes of LAB communities with different growth rates are affected by acid stress changes, demonstrating that species with slower growth rates are favored under increased acid stress. We also explore lactate stress as a significant driver for interaction variability and metabolic excretion, elucidating that cross-feeding public goods promotes interspecies cooperation and coexistence. Finally, we report experimental results on the interactions between LAB and yeast, confirming the generality of this synergistic stress-tolerant mechanism. In summary, our study demonstrates that free-living microbial communities can respond to changing acid stress by altering physiology and metabolism to promote community-level cooperation and stress tolerance.

Results

A system to study the spatial effects of acid stress on the colonization, growth, and interactions of LAB clones

To determine how complex environments affect the behavior and dynamics of free-living microbiota, we simulated a porous micromodel through solid agar media, including complex physical structures similar to those commonly found in fermentation substrates, intestines, soils, and sediments24,33. Using this porous micromodel as a basis, we constructed a system of acid stress changes where lactate diffuses through the physical structure, leading to dynamic changes in acid stress (Fig. 1A). To further simulate natural acid stress changes, we inoculated 2 μL of the lactate producer at the center of chemically defined medium agar plates containing 2% glucose (CDMG) and an acidic chromogenic agent (see Methods, Fig. 1B). The results revealed that coloration commenced 10 hours post-inoculation, marking the onset of lactate spatial diffusion. Subsequent assessments at 14, 24, 32, and 40 h indicated diffusion distances of 0.63 ± 0.03, 1.67 ± 0.04, 2.64 ± 0.02, and 4.58 ± 0.05 cm, respectively (Fig. 1B). Therefore, based on the spatial-temporal diffusion of lactate in agar plates, we could use this system to investigate microbial colonization, growth, and interactions during acid stress changes.

A–B Representative images of the spatial and temporal diffusion characteristics of lactate were monitored by inoculating lactate (A) and lactate producer LM (B) in CDMG agar plates containing bromocresol purple as an indicator. The diffusion distance of lactate over time was monitored by changing from purple to yellow (yellow circles) and quantified using a ruler. The experiment was repeated three times. C Three isolated LAB clones (LM, LC4, and LC2) were inoculated on CDMG agar plates. After 1.5–2 days of incubation at 30 °C, differences in growth were observed between the edge and center populations, indicating spatial position dependence. The images are representative images from three biological replicates. Differences in camera angle and time resulted in color differences in the three images. D Schematic diagram of inoculating clones from CDMG agar plates into liquid medium (inoculation ratio: OD600 = 0.6, 1% v/v) based on center and edge populations, followed by incubation at 30 °C for 16 h to assess biomass and lactate production. E Comparison of growth rates and lactate yields of three LAB clones inoculated from CDMG agar plates into liquid CDMG medium based on center and edge positions. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates. F Morphological characteristics of isolated LAB clones on CDMG agar plates supplemented with 100 mM MOPS, with smooth colony surfaces and no difference in growth were observed between edge and center populations. The images are representative images from three biological replicates. G Morphological features of the non-lactate-producing engineered strain LMΔldh with smooth colony surfaces and no difference in growth were observed between edge and center populations. RP stands for repeat. H Growth rates and lactate yields of the three LAB clones supplemented with 100 mM MOPS according to center and edge positions. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates. I Growth rates and lactate yields of LMΔldh clones according to center and edge positions. RP stands for repeat; GR: growth rate; LPR: Lactate production rate. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates.

This study started with the colonization characterization of individual LAB clones, Leuconostoc mesenteroides C7M43 (LM), Leuconostoc citreum 4367 (LC4), and Leuconostoc citreum 200443 (LC2), isolated from fermented foods, in a stress-changed system containing CDMG agar (Fig. 1C and Table S2). After 1.5-2 days of growth at 30.0 °C, all three naturally cultured LAB clones exhibited distinct spatial position dependencies, with higher local densities observed at the edges (Fig. 1C), contrasting sharply with the uniform distribution observed in other characterized strains34. We assessed the growth and acid-producing properties of populations located at the edges and center of the LAB clones (Fig. 1D). When inoculated in a CDMG liquid medium, populations were characterized by growth and acid-producing rates with distinct dependencies on the selection position, with the edge populations of all LAB clones exhibiting ~1.2-fold faster growth rates, but produced acid at a rate ~ 0.7-fold lower than the central populations (Fig. 1D, E).

To validate the impact of lactate stress on position-dependent colonization, we supplemented the medium with 100 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) to stabilize the acidity of agar. The results showed that upon removal of lactate stress, colonies exhibited a uniform distribution, abolishing position dependence (Fig. 1F). To eliminate the effects of other metabolites, we engineered a stress-silenced LAB strain, LMΔldh, incapable of lactate production (Fig. S1), and observed a similar absence of position dependence (Fig. 1G). The growth and acid production rates of clone populations at different spatial positions were analogous when the lactate stress was eliminated (Fig. 1H, I), starkly contrasting with the phenotypic variations where lactate stress persisted (Fig. 1E). These findings suggested that acid stress underlay position-dependent colonization, influencing the population response to chemical signals from the abiotic environment and regulating their growth and metabolic activities accordingly. In particular, these stress changes may influence the spatial-temporal dynamics of microbial interactions at the community level.

Spatial effects of acid stress on biomass

To elucidate the impact of lactate stress at the community level, we established microbial consortia containing producer LM and competitors using lactate diffusion-induced stress changes as a key factor (Fig. 2A). When other competitor strains (Table S2) were drop-plated at different distances from the lactate producer LM (See Table S1 for the definition of monoculture, Fig. 2B), we observed that all strains were inhibited by LM, exhibiting spatial-distance dependent responses in biomass (Fig. 2C, Comparison of colony growth). Specifically, the relative biomass of competitor strains increased with distance because when lactate was released, it diffused and suppressed nearby growth (Fig. 2D), which has been termed “lactate stress” or more generally “acid stress”. At a distance of 4.5 cm, biomass levels resembled those of plates inoculated with stress-silenced LMΔldh, with a relative biomass of 1 (Fig. 2D), revealing an interaction range from 0.0 to 4.5 cm (Fig. 2C, D).

A Schematic diagram for the construction of microbial consortia based on lactate diffusion. B Cartoon diagram of interactions between producer LM and other competitor strains. C Representative images of producer LM interacting with different competitors at different distances. The inoculation method is shown in Fig. 2B. Strain information is shown in Table S2. The experiment was repeated three times. D Relative biomass (OD600) of competitors inoculated at different positions after 33 h of cultivation in C. The biomass (OD600) of individual strains in agar plates was assayed as shown in Fig. S2. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates. The error bars are not shown because they are too small to be visible. E Flowchart to construct a relationship curve of biomass (CFU/mL) versus fluorescence intensity. Detailed steps are described in the method section. F Fluorescence images of mixed inoculated binary consortia in equal proportions. On the left was a cartoon diagram of the inoculation. The upper part on the right was the fluorescence images inoculated at different distances and incubated at 30 °C for 33 h. The lower part on the right was the fluorescence image when the fluorescent protein was swapped. The green color indicates that the strain carries a green fluorescent protein (eGFP), while the red color indicates a red fluorescent protein (mCherry). Scale bar = 2 mm. The images are representative images from three biological replicates. G, H Fluorescence images of separated inoculated binary consortia in equal proportions. The other meanings are the same as in the legend of (F). The images are representative images from three biological replicates. Se-inoculation means separated inoculation. I Relative biomass of mixed inoculated binary consortia in equal proportions. The biomass of the strain in pure culture was used as a control with a value of 1. The data represent the values of three biological replicates. J, K Relative biomass of separated inoculation in equal proportions. The data represent the values of three biological replicates.

To further investigate this phenomenon, we labeled the strains using fluorescent proteins, including eGFP, YFP, and mCherry (see “Methods”, Figs. S3A and S3B), and then plotted the transformation curve of the relationship between the obtained colony-forming unit (CFU) and fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2E, Fig. S4, and Table S6). Based on this quantitative relationship, we first evaluated the growth dynamics of binary consortia (See Table S1 for definitions), including a producer LM and Lactococcus lactis CCFM 1092 (A01) from the same sample source (Fig. 2F, G). Fluorescence microscopy results revealed that in mixed co-inoculation (LM: A01 = 1:1) incubated for 33 h (Cartoon diagram of Fig. 2F), A01 competitively suppressed the producer LM (Fig. 2F upper panel and 2I) owing to its rapid growth rate (Fig. S5). However, the competitive hierarchy of the consortia reversed in diffusion-based separated inoculations (See Table S1 for the definition of co-culture, Cartoon diagram of Fig. 2G), with LM prevailing over A01 due to lactate stress, yet this stress effect weakened with increasing diffusion distance (Fig. 2G upper panel and 2 J). Similarly, fluorescent protein exchange yielded consistent results (Bottom panel of Fig. 2F, G). We further investigated this stress effect by utilizing the co-isolated strain L. lactis CCFM 1032 (B01), which shares the same sample origin as A01, to construct different binary consortia (Fig. 2H). The results confirmed that the relative biomass of B01 increased with distance in diffusion-based separated inoculations, whereas the opposite was true for LM, as the stress effect decayed with distance (Fig. 2K). Furthermore, competitors A01 and B01 did not alter the lactate production level of producer LM (Fig. S6), suggesting that only unidirectional interference occurs in the binary consortia.

To confirm that these position-dependent findings in the consortia were also caused by lactate stress, we replicated the monoculture experiments on CDMG agar plates by adding 100 mM MOPS and employing stress-silenced engineered strain LMΔldh to focus on non-lactate stress (Fig. S7A–B). The results indicated that when lactate stress was eliminated, the growth of all strains was not inhibited, with relative biomass approaching 1, regardless of their spatial positions (Fig. S7C). Conversely, to focus on lactate stress, we replicated the inhibition effect of in vitro lactate stress on diffusion-based consortia by replacing lactate producer LM with lactate (Fig. S7D), and the results showed that the growth of competitors was inhibited (Figs. S7E and S7F). Thus, the observed position dependence in the monocultures was also predominantly derived from lactate diffusion-induced stress changes that determine biomass accumulation and distribution. However, the fluorescence images of A01 and B01 were significantly different in monocultures and co-cultures (Figs. S8, S9, and S10), indicating that the observed differences are indeed because of the interactions between the two co-cultured strains, and not merely the result of lactate stress-driven growth dynamics between LM and the other strains.

Growth-tolerance trade-offs induced by acid stress drive community succession and interaction dynamics

To investigate microbial interaction dynamics during acid stress changes, we employed a 2 µL mixed suspension (A01: B01 = 1:1, OD600 = 0.2–0.3) with distinct growth rates and tolerance abilities (Figs. S11 and S12) and co-cultivated at different distances from the LM to evaluate multispecies microbial colonization in extensively acidified habitats (Fig. 3A). The biomass ratio of the population (fold change R = B01 biomass / A01 biomass) in ternary microbial consortia was calculated by the biomass ratio of B01 to A01 (see Fig. 3A for biomass detection). With an initial strain ratio of 1:1, we found a spatial inflection (λx) at 2.5 cm, which was the spatial distance from the community to producer LM, where the behavior of spatial range expansion flipped (Fig. 3B, C, and Figure S13A left panel). Specifically, the fitness of A01 and B01 at λx was approximately equal, with fold change R approaching 1, while A01 and B01 dominated different spatial regions in both ends of λx, slower-growing A01 (green) dominated in the short-range (<2.5 cm) with its tolerance advantage, while low-tolerance B01 (red) dominated in the long-range (>2.5 cm) with its growth advantage (Fig. 3B–D), revealing the growth-tolerance trade-off pattern of microbial consortia at λx. Lactate stress-based changes in growth rate between two phenotypically different species appeared to explain this pattern (Fig. S12). However, performing biomass comparisons between monocultures and co-cultures revealed not only the lactate stress effect, but also lactate stress-induced interspecific interactions in the spatial domains that manifested as cooperation close to λx and competition away from λx (Fig. 3B, C). To gain insight into this pattern, we manipulated the initial strain ratio of the A01 and B01 from 1:5 to 5:1 (Fig. S13A right panel). Although this change affected the relative abundance at a given time, it did not alter the growth distribution of A01 and B01 across spatial ranges, while spatial inflexion λx consistently fluctuated around 2.5 cm (Fig. S13A right panel and Fig. 3D), which highlighted that a strain’s fitness at a specific position depends on the presence of interactions and the state of the environment during the colonization of natural communities3,35.

A Schematic of the biomass in the microbial consortia calculated by fluorescence intensity. The cartoon diagram on the left shows an inoculated culture of the ternary microbial consortia. The colonies at different distances were placed on separate agar plates. Specific steps for calculating biomass based on fluorescence intensity are described in the method section. Biomass comparison of A01 (B) and B01 (C) in monoculture and co-culture at different distances. Mono- represents monoculture. Co- represents co-culture. Schematic of monoculture is shown in Fig. 2B. The red dashed box indicates the distance at the spatial inflection point λx, where the fitness of A01 and B01 was similar. D Biomass ratios (fold change R = B01/A01) at different distances when A01 and B01 were inoculated with different initial inoculation ratios and incubated for 33 h. The red frame indicated the spatial distance at which the fold change R was maintained between 0.5 and 1.5 for different initial inoculation ratios. The data represent the values of three biological replicates. E The curve of biomass ratios (fold change R = B01/A01) at different distances when A01, B01, and EH1 were inoculated with different initial inoculation ratios and incubated for 33 h. The meaning of the red frame is the same as in D. The ratio at the top indicates the initial inoculation ratio, and the color of the circle in front of the ratio corresponds to the color of the curve in the figure. F Lactate stress-induced colonization ecology of quaternary microbial communities based on biomass ratios (fold change \(\bar{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\)), revealing niche occupancy (left), coexistence (middle), and invasion (right). Invaders were considered invasive when their biomass ratio (fold change \(\bar{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\) = Ai/N) was greater than 50%. The initial inoculation ratio was 1:1:1. N represents the maximum biomass, which is the sum of the biomass of A01, B01, and EH1 at 4.5 cm. Ai represents the biomass of individual strains in quaternary co-culture. The data in (B), (C), (E), and (F) represent the average of three biological replicates; see source data for SD.

The study on the lactate stress-induced community dynamics revealed unexpected colonization strategies under growth-tolerance trade-offs. To test the ecological significance of growth-tolerance trade-offs in habitat colonization, we employed the co-isolated invasive strain Enterobacter hormaechei 42D12 (EH1, Table S2), a prevalent spoilage bacterium in fermented foods36, to construct quaternary consortia (A01: B01: EH1 = 1:1:1, OD600 = 0.2–0.3, see Fig. S14). When still analyzing the fold change R (B01/A01), the consortia also exhibited a spatial inflection λx, and the behavior of range extension still flipped at λx of 2.5 cm, thereby exhibiting a growth-tolerance trade-off (Fig. S13B left panel and S15), as observed in ternary microbial consortia (Figs. 3B, C, and S13A left panel). Furthermore, the inoculation results for both equal and varying initial strain ratios indicated that maintaining the fold change R within 1.0 ± 0.5 was critical for population coexistence, since when deviating from this range, one population in the consortia was rapidly outcompeted and eliminated at all initial frequencies (5:1–1:5), as was the case for B01 below 0.5 or A01 above 1.5 (Fig. S13B right panel and 3E). Importantly, the spatial distances favoring the coexistence of quaternary consortia were also around the relatively stable value of 2.5 cm from the producer LM clone (Fig. 3E, Red frame). Microbial colonization habitats are intuitively perceived as complex and difficult to quantify3,37. Our results indicated that lactate stress-induced spatially structured communities follow a structural paradigm of ordered and stable coexistence over centimeter-long ranges.

To further reveal lactate stress-induced ecological succession in quaternary consortia, the biomass ratio of the population was modified (fold change \(\bar{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\) = Ai/N). The result showed that lactate-induced growth-tolerance trade-offs drove range expansion and stable coexistence (Fig. 3F). Specifically, both competitors (A01 and B01) exhibited superior performance over the invader (EH1) when exposed to enhanced lactate stress near the producer, and one competitor was selected to occupy the habitat (Fig. 3F left). The consortia were then driven to a stable spatial distance (λx ~ 2.5 cm) at which both coexist (Fig. 3F center). However, diminishing lactate stress compromised the suppression of the faster-growing invasive strain EH1 (Fig. S12), leading to the elimination of A01 and B01 at all initial frequencies and subsequent invasion (Fig. 3F right). Interestingly, a comparison of biomass in monoculture and co-culture of quaternary consortia revealed that in addition to the lactate stress effect, A01 and B01 also exhibited competitive interactions at short range (<λx), while their cooperative interactions close to λx enabled them to coexist and resist EH1 invasion (Figs. S15 and S16). Furthermore, lactate supplementation and invasion experiments also demonstrated the existence of not only lactate stress effects but also cooperative interactions (Fig. S17). While previous studies have typically focused on lactate stress-based growth inhibition and one-way interactions3,37,38, our investigation highlighted that lactate diffusion-induced stress not only drove growth-based ecological succession but also influenced interaction dynamics, including competition and cooperation (Figs. 3, S13, and S15). These interaction dynamics were generally related to the intensity of lactate stress, as the intensity of acid stress varies with diffusion distance and time. However, the results observed above were all at a single time point (33 h of incubation), which may lead to differences in the interactions observed at different distances (Figs. 3, S13, and S15). Therefore, these interaction dynamics may be the result of a time series of interaction strengths.

Stress intensity drives microbial communities to shift from competition to cooperation

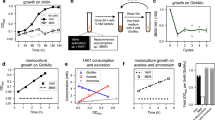

To test whether the interaction dynamics that emerge depend on acid stress changes and thus on the stress intensity, we hypothesized that this dynamic might be caused by stress-resource-mediated interactions between species and proposed a time-series model of interactions between lactate stress intensity and cross-feeding of public goods (See Table S1 for the definition): the producer LM consumes resources to produce lactate, leading to stress, and based on the stress degree, subsequently stressed species alter the excretion of beneficial metabolic by-products (defined as public goods see Table S1), which contribute to growth and stress tolerance among species (Fig. 4A). The interaction results at different spatial distances indicated that competitive and cooperative interaction variation in pluralistic microbial consortia typically occurred at 2.5 cm (Figs. 3B, C, and S15). Therefore, this distance was chosen to incubate microbial consortia to test the stress-resource-mediated physiological and metabolic responses in the above hypotheses. Firstly, ternary co-cultured microbial consortia 2.5 cm apart on CDMG agar plates were used as test subjects (see Fig. 3A for inoculation method), and quantitative methods for growth at different times and uptake/excretion characteristics extracted from different regions were constructed (see “Methods”, Figs. 4B and S18). The plates were then divided into three square regions (a, b, and c) based on the extraction region (Cartoon diagram of Figs. 4B and S18). The concentrations of lactate and glucose detected by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) showed statistically significant differences across regions (lactate at 24 h: region a vs. region b, df =16, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 2.4, 95% CI of diff. =[98.8, 104.8]; region a vs. region c, df =16, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 7.9, 95% CI of diff. =[84.4, 110.1]; region b vs. region c, df =16, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 5.7, 95% CI of diff. =[86.0, 105.7]; glucose at 24 h: region a vs. region b, df =16, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 2.1, 95% CI of diff. =[22.8, 26.4]; region a vs. region c, df =16, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 7.6, 95% CI of diff. =[19.1, 39.5]; region b vs. region c, df =16, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 7.1, 95% CI of diff. =[21.6, 38.5]; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test; Fig. S19). To better understand the dynamics of the constituents, we used the measurements from the central region (region b) as the reference values to characterize the final concentrations.

A Schematic of putative stress-resource-mediated interspecific interactions. Blue gradient circles indicate lactate diffusion, and different diffusion distances indicate different stress intensities. The magnification above is a visual interpretation of the excretion and cross-input of public goods in different competitors inoculated at the same location on the right side of the producer LM. B Flowchart of the method for the detection of resource and metabolite content on agar plates. Detailed steps are described in the method section. C Schematic of mono-cultures and co-cultures, wherein the mono-culture schematic is the same as Fig. 2B and the co-culture schematic is the same as Fig. 3A. D Biomass of A01 and B01 in mono- and co-culture on CDMG agar plates. Inoculation was shown in the cartoon diagram of Fig. 4C. The gray shaded area indicates the stage of B01 regrowth (indicated by RG). The red arrow indicates when regrowth started. E HPLC-detected glucose and lactate concentrations in extracts from co-culture regions of A01 and B01, with glucose concentration shown on the right vertical axis. The gray-shaded areas indicate glucose and lactate concentrations at regrowth of B01 in C. Arrows have the same meaning as in D. F HPLC-detected pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate concentrations in extracts from co-culture regions of A01 and B01. The gray-shaded area indicates the trend of these metabolites during the regrowth of B01 in Figure C. Arrows have the same meaning as in D. The data in (D) to (F) represent the average of three biological replicates; see source data for SD. G B01 cells were counted during the regrowth phase in co-culture (orange circles), lactate alone (blue triangles), and the mixed supplements of lactate, pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate (purple boxes), respectively. In. Ph. represents the increasing phase of co-culture with A01. La. Al. represents the lactate alone. La. Pg.Supp. represents the mixed supplements of lactate, pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate. The data represent the average of two biological replicates, as shown in the source data.

In this way, we subsequently monitored each pure culture’s biomass and uptake/excretion characteristics on CDMG agar plates (See Table S1 for the definition of pure culture). LM, A01, and B01 experienced logarithmic growth reaching a stabilization period within 24–27 h (Fig. S20A). Carbon-sourced metabolites such as amino acids can be used as public goods to promote cross-feeding between communities29,37,38, and these public goods were selected for potential analysis. Examination of excretion data using HPLC showed only small accumulations of pyruvate, aspartate, and glutamate in pure cultures LM, A01, and B01 (Figs. S20B–S20D). In LM pure culture, glucose was depleted at 27 h (Fig. S21A, Orange square) and lactate reached a maximum of 121.7 mM (Fig. S21A, Red circle), significantly lower than 193.4 mM (df = 4, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 43.7, 95% CI of diff. =[89.6, 232.9]; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test) in well-mixed liquid culture (Fig. S21B), indicating that the lactate released during rapid growth on glucose diffuses directly into the medium leading to habitat acidification (Figs. S21 and 1B). As another test, we monocultured A01 and B01 separately at 2.5 cm to the right of the LM (Left panel of Fig. 4C), and found that slower-growing A01 underwent a logarithmic phase, reached maximum biomass at 30–33 h, and then remained stable (Fig. 4D, Blue triangle), metabolically showing an increase in pyruvate, aspartate, and glutamate (Comparing Fig. S22A with S20C); faster-growing B01 also underwent a logarithmic period, reached maximum biomass at 27 h, stabilized at 27–30 h, and then began to decay (Fig. 4D, Purple triangle), metabolically exhibiting several key metabolites that did not increase (Comparing Fig. S22B with S20D). Moreover, 24 h in monoculture was the inflection point of biomass dominance for both species, where biomass dominance flipped at this time (Fig. 4D). Specifically, the faster-growing B01 dominated within the initial 24 h, while the slower-growing A01 outcompeted B01 at 24 h (Fig. 4D, Blue and purple triangle), a shift attributed to increased stress intensity that inhibited the growth of the faster-growing, less stress-tolerant B01 (Fig. S12).

To determine the dynamic interactions of microbial consortia under lactate stress, a 2 µL mixed suspension (OD600 = 0.2–0.3) containing equal amounts of A01 and B01 was co-cultured at 2.5 cm to the right of the producer LM to analyze the biomass of the two species at different times (Right panel of Fig. 4C). We first monitored the lactate content in agar plates to elucidate lactate stress. The results showed a gradual increase in 0–33 h, reaching 68.8 mM at 24 h and a maximum of 98.2 mM at 33 h (Fig. 4E, Red open circle), and the inconsistency with the time of sugar exhaustion and maximum lactate level in the producer LM at 27 h was due to the lag in diffusion time (Fig. S21A and Fig. 4E). When subsequently monitoring the growth dynamics of co-cultures under lactate stress, we found that 24 h in co-culture remained the inflection point of biomass dominance for both species (Fig. 4D, Red and orange circles). However, the biomass of both species A01 and B01 in the co-culture was less than that of the monoculture in 0-24 h (Fig. 4D), revealing that species also occupy niches through competitive interactions in addition to lactate stress. With increasing lactate stress, A01 and B01 reached maximum biomass at 30 h and 24 h, respectively, and then entered growth arrest (stable period), which was similar to the trend in the monocultures (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, within 30–33 h of further increased lactate stress, there were significant differences in growth kinetics between monocultures and co-cultures, where the biomass of B01 increased significantly in co-cultures but decayed in monocultures (Comparison of biomass in Fig. 4D). Moreover, the biomass of both species A01 and B01 in the co-culture was higher than that of the monoculture in 30–33 h (A01: df =4, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 2.4, 95% CI of diff. =[592534084.7, 636534084.7]; B01: df =4, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 12.3, 95% CI of diff. =[370897222.8, 656897222.8]; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test), suggesting that cooperative interactions were present under high lactate stress (Fig. 4D). These results suggested that stress intensity drove interaction dynamics that shifted microbial communities from competition to cooperation.

The rapid decline in the biomass of faster-growing, low-tolerance B01 after 30 h of monoculture was due to rapid cell death in strong lactate stress (Fig. 4Dʹs purple triangle and Fig. S12). Death originating from rapidly proliferating species may promote community coexistence in stressful environments39,40,41. Therefore, the preferential mortality of B01 might be expected to facilitate the coexistence of co-cultured A01 and B01 under high lactate stress. Typically, B01 death-mediated coexistence can strongly bias species proportions in favor of A01 and leave large amounts of unconsumed nutrients remaining39,40,41. However, our data showed a different result: the biomass of B01 instead increased in 30–33 h, with the biomass ratio (fold change R = B01/A01) approaching 1 at 33 h (Fig. 4D, Gray shaded region), consistent with the results of biomass ratio observed by single-cell fluorescence microscopy for coexistence at 33 h (Fig. 3D, Green open circle). Moreover, the low amount of residual glucose (22.8 mM) at 30 h and consumption was significantly reduced over the next 6 h to 8.66 mM (Fig. 4E, Blue open square), yet it prompted regeneration of B01 and the coexistence of both A01 and B01 (Fig. 4D), suggesting that there are other mechanisms underlying coexistence in co-culture that are not caused by the preferential death of the rapidly proliferating B01.

Metabolic excretion by the slower-growing A01 favors regrowth of B01 and interspecies coexistence

To determine the reasons behind the B01 regrowth and the mechanistic basis of coexistence during the late growth phase, we further analyzed the co-culture consortia’s uptake/excretion properties. HPLC detection of the medium showed that other pivotal metabolites, including pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate, also accumulated to high concentrations (Fig. 4F, Gray shaded area) when the lactate content was near maximum at 30 h (Fig. 4E, Red open circle). The subsequent disappearance of these metabolites coincided with the recovery phase of B01 growth (Fig. 4D, F, Red arrow), while the density of A01 remained constant (Fig. 4D, Red circles). During its increase, the growth rate of B01 was significantly higher than when using lactate alone (Fig. 4G, Orange circles and blue triangles), slightly higher than that of B01 in a mixture of equal amounts of lactate, pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate (Fig. 4G, Purple boxes), indicating that these additional metabolic by-products, namely public goods, may contribute to the B01 regrowth in lactate stress. The consumption of these public goods also explained the differences in their concentrations in B01 pure and monocultures (Figs. S20D and S22B), as well as in A01 monocultures and their co-culture with B01 (Figs. S22A and 4F). Despite being short-lived (approximately 3 h), the increase of B01 was a key phase in co-culture dynamics, with its density increase of 1.16 × 108 for 126.19% of the 30-h biomass (Fig. 4F, Orange circles).

To understand how B01 successfully regrew at high lactate concentrations, we first prepared spent media from the agar plate of A01 monoculture and performed re-culturing of B01 (Schematic of Fig. S23). The results showed that B01 could grow in the spent medium (Fig. S23B, Blue circle), accompanied by a reduction of these public goods in the spent medium (Fig. S23C). B01 was subsequently monocultured in 100 mM and 140 mM lactate-acidified CDMG medium without and with supplements, including 6.0 mM pyruvate, 2.7 mM glutamate, and 2.0 mM aspartate (see “Methods” and Fig. 5A), the public goods which depleted significantly during the regrowth period (Fig. 4F). B01 grew only in the presence of supplements, which was attributed to the uptake of these public goods (Fig. 5B, C). The growth dynamics of B01 were monitored again using supplemental experiments in which different concentrations of public goods were added to 100 mM lactate-acidified CDMG medium. In this case, B01 biomass increased with increasing concentrations of the supplements (Fig. 5D). However, when these public goods productions were inhibited using the inhibitor 3-bromopyruvate (Fig. S24), a significant reduction in biomass was observed, and B01 regrowth was absent in co-culture growth dynamics (Comparing Figs. 5E with 4D), despite a small consumption of public goods (Fig. 5F). In addition, when the spent medium was prepared using A01 monocultured medium supplemented with inhibitor and then re-cultured with B01, B01 growth was reduced in the spent medium supplemented with the inhibitor compared to the spent medium not supplemented with the inhibitor (Fig. S25, Orange squares and red circles), which stemmed from the lack of these public goods in this spent medium, as supplementing public goods restored B01 growth to levels similar to those in spent medium without inhibitors (Fig. S25, Blue triangles and red circles). Thus, the accumulation and feeding of these public goods promoted the growth of B01 in high acid stress.

A Schematic diagram to verify that B01 can successfully grow again in public goods and A01 excretes public goods. Detailed steps are described in the method section. B OD values of B01 monocultures in the acidified CDMG liquid medium with (w/Pg.Supp., filled symbols) or without public goods (wo/Pg.Supp., open symbols). C Changes in the content of public goods over time were detected by HPLC when B01 was monocultured in 100 mM lactate-acidified CDMG liquid medium supplemented with public goods, including 6.0 mM pyruvate (right vertical axis), 2.7 mM glutamate, and 2.0 mM aspartate. D OD values of B01 monocultures in 100 mM lactate-acidified CDMG liquid medium supplemented with different concentrations of public goods (PG). The black-filled square in D was a reuse of the gray open square in B. Specific concentrations supplemented are shown in Table S4. E Biomass of mono- and co-cultured A01 and B01 in CDMG agar plates supplemented with the inhibitor 3-bromopyruvate. F HPLC-detected pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate concentrations in extracts from co-culture regions of A01 and B01 in CDMG agar plates supplemented with 3-bromopyruvate. G Changes in biomass and glucose concentration (right vertical axis) over time when A01 was mono-cultured in 100 mM lactate-acidified CDMG liquid medium containing 25.0 mM glucose without adding public goods. H Content of public goods excreted by A01 into the medium was detected by HPLC over time when A01 was mono-cultured in 100 mM lactate-acidified CDMG medium without added public goods. The data in (B–H) represent the average of three biological replicates; see source data for SD. I Untargeted metabolomics to detect the relative intensity of cocultured metabolites in CDMG medium, as detailed in “Methods”. The color lines indicate the change curves for the pivotal metabolites (those with relative intensities <0.5), whereas the gray lines indicate the change curves for the other metabolites. Specific metabolites are listed in Table S5.

To elucidate the sources of these public goods, we maintained slower-growing A01 monocultures under lactate inhibition with a 100 mM lactate concentration to capture conditions during the lactate peak in a co-culture stable distance. Under these high lactate conditions, A01 could absorb glucose (Fig. 5G, Purple circles) and grow slowly (Fig. 5G, Orange circles), while aspartate, pyruvate, and glutamate accumulated (Fig. 5H), contrasting sharply with A01 monoculture without added lactate (Fig. S20C). The additional public goods were not mainly from dead/lysed cells, as A01 viability did not decrease during their accumulation (Fig. 5G, Orange circles). Importantly, the amount of carbon released (~18.5 mM C atoms in total within 6, including 1.2 mM aspartate, 4.3 mM pyruvate, and 2.2 mM glutamate) accounted for 60% of glucose consumption (5.2 mM) (Fig. 5H). Thus, under high lactate stress, A01 cells actively converted glucose into these public goods and excreted them, which B01 could then uptake to support its growth. Untargeted metabolomics analysis of the spent medium from A01 monoculture during self-acidification revealed an increase in other metabolite profiles besides those already mentioned (Table S5 and Fig. S26), explaining why the total C-atoms of the public goods accounted for only 60% of the glucose consumption (Fig. 5H). To determine if these metabolites could also be cross-fed in co-culture, we performed untargeted metabolomics analysis42,43 on spent medium collected during the lactate peak. Several metabolite profiles were found, exhibiting dynamics similar to those of aspartate, pyruvate, and glutamate (Table S5 and Fig. S26). In summary, these data suggested that various metabolites were excreted by slower-growing A01 and cross-fed into B01, with pyruvate, aspartate, and glutamate being the most predominant metabolites quantitatively (Table S5, Figs. S26 and 5I). Thus, the stress-tolerant, slower-growing species secreted public goods, and cross-feeding of these public goods promoted the persistence of the stress-sensitive species by enhancing interspecific cooperation.

Physiological processes and mechanisms underlying lactate stress-induced cross-feeding and coexistence

Next, we explored the process and the mechanisms by which the slower-growing species A01 secretes public goods to cross-feed B01 and promote their coexistence under lactate stress. Based on acid-tolerant mechanisms such as ATP energy synthesis, amino acid conversion, and TCA intermediates12,31,44, we hypothesized the following process and mechanism: for the slower-growing A01, it increased glycolytic flux for energy biosynthesis intracellularly in lactate stress and TCA intermediates (which amino acids are linked reversibly) were excreted to the extracellular as public goods (pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate) to alleviate the increased intracellular glycolytic flux, thus favoring the growth and maintenance of A01 in acid stress; for the low-tolerant B01, it can utilize the excretory public goods of A01 to grow, which in turn promoted an increase in intracellular glycolytic flux of A01, and this bi-directional interaction led to coexistence of A01 and B01. The increase in glycolytic flux during lactate stress was supported by the fact that A01 under lactate stress excreted higher levels of public goods than A01 without lactate stress (Figs. S20C and S22A), and that, during the stabilization phase with high stress, A01 took up glucose and excreted 60% of its C-atoms as public goods (Fig. 5H). The experiments with spent media and supplementation of public goods also verified that public goods excreted by A01 in co-culture promoted the growth of B01, which hardly excreted public goods (Figs. 5D and S23B).

To further test this hypothesis, we monitored the intracellular ATP content of A01 in monocultures exposed to lactate stress. It was found that for the same biomass, the content of intracellular ATP in A01 at 60 mM and 100 mM lactate concentrations was 1.65 and 3.84-fold higher than that without lactate (Fig. S27A). Moreover, we also monitored the intracellular ATP content of A01 in co-cultures exposed to 100 mM lactate stress, as well as the level of public goods in the medium. At 8 h, ATP content in A01 in co-cultures was 2.32-fold higher than in monocultures (Fig. S27B), while the concentration of public goods in the co-culture was lower than in the monoculture, although they both reached their maximum at this time (Figs. 5H and S27C). As the incubation continued, A01 in the monoculture showed a decline over the next 6 h (Fig. S27D), accompanied by a slight decrease in public goods (Fig. S27E), and glucose levels below 16 mM (Fig. 5G). However, A01 biomass in the co-culture remained stable, and the public goods decreased significantly (Fig. S27D and S27F). At this time, the intracellular ATP content of A01 in co-culture was 3.56-fold higher than that of A01 in mono-culture, and 1.24-fold higher than that at 8 h (Figs. S27G and S27B), revealing that the biomass-stabilized A01 in co-culture remained metabolically active. These results suggested that consumption of public goods by B01 does promote an increase in glycolytic flux, excretion of TCA intermediates, and vitality maintenance of A01. Thus, although B01 did not excrete public goods beneficial to A01 growth, this bidirectional interaction nonetheless enhanced A01’s cellular activity and supported a slightly higher biomass in the co-culture versus the monoculture (Fig. 4D).

To investigate the reasons for the decrease in public goods in A01 monocultures, we exposed A01 to a 100 mM lactate-acidified medium supplemented with the same public goods concentration and different glucose concentrations (see”Methods”). The results showed that A01 can also consume public goods to maintain activity, but only at glucose concentrations below 15 mM (Fig. S28), suggesting that A01 exhibited substrate preference and priority. However, despite this, in the later stages of the monoculture, the rate of cell decay was higher than the rate of growth, leading to a reduction in overall growth (Fig. S27D). The physiological processes described above revealed a synergistic mechanism between the two phenotypes, slower-growing, tolerant A01 and faster-growing, intolerant B01. This interspecific cooperation and coexistence under acid stress may be widespread among multiple species with complementary growth rates.

A mathematical model of lactate stress-induced cross-feeding and coexistence captures dynamic physiological processes

To further understand why lactate stress-induced cross-feeding can rescue co-cultures, enabling their stable coexistence, we constructed a dynamic model of growth and cross-feeding to provide a quantitative account of the dynamic features observed (Supplementary Notes 1 and 2). The model was first parameterized using measurements on individual strains. The growth rate of A01 (RA) depended on glucose concentrations (G) and lactate concentration (Cs), and the growth rate of B01 (RB) depended on G, Cs, and M (lactate-induced metabolites) in the co-culture (Fig. 6A). Further, B01 was more sensitive to lactate, and hence to increased lactate (Fig. S10). To illustrate intuitively, we believe that the change from growth to growth arrest is a difficult transition. Thus, for Cs below some threshold concentrations, Cs-A01 = 140 mM and Cs-B01 = 100 mM for A01 and B01, respectively, we consider the growth rates (RA and RB) to be of the Monod form, and if the lactate concentration (Cs) is above the thresholds (Supplemetanry Notes 1 and 2).

A Growth dynamics of acid-induced cross-feeding based on consumer-resource modeling. Rate functions in the four processes corresponding to A01 (Ai, Aii, Aiii, and Aiiii) all depend on the internal state of A01 (σA), resource (G), and lactate (Cs), whereas the four processes in B01 (Bi, Bii, Biii, and Biiii) depend on G, Cs, and metabolite (M). These processes were separated by vertical or horizontal red solid lines and distinguished by varying shading of gray. Effective and ineffective interactions were marked by black solid and black dashed lines, respectively. Facilitatory interactions were marked with arrows, while inhibitory interactions were marked with horizontal T’s, and labels were placed at the top. Blue thin arrows represent changes in lactate levels, represented by gradient arrows at the top and bottom of the figure, where a change in color from lighter to darker represents an increase in lactate level. Yellow thin arrows indicate changes in σA. Green thick arrows represent lactate stress-induced cross-feeding that allows B01 to regrow during lactate stress. B Cartoon diagram of lactate stress-induced cross-feeding resulting in interspecific cooperation. The left panel summarizes the cross-feeding mechanism shown in Figure A (black frame). A01, with the tolerance advantage, took up carbon sources and excreted public goods that B01 can utilize, allowing B01 to regrow under acid stress and promoting stress tolerance in the population (right panel, red and purple frames). The arrows and variables have the same meaning as in Fig. A. C The growth of A01 (solid line) and B01 (dashed line) was described according to the model. The variation in growth of co-cultures A01 and B01 of Fig. 6A, B is composed of multiple physiological states, indicated by the color bands. Both A01 (characters) and B01 (numbers) undergo periods of lag and exponential growth. A01 was followed by periods of stabilization and decay, while B01 was followed by periods of stagnant growth (Orange band), regrowth (Purple band), and decay. Additional details can be found in the supplementary Notes.

Subsequently, we explored the entire physiological process by constructing a dynamic model of acid-induced metabolic cross-feeding between A01 and B01 (Fig. 6A). This process not only integrates strain characteristics obtained in monoculture, containing the excretion/uptake properties of public goods, but also considers the stable period of A01 and the growth of B01 6 h after the stable period (Fig. 6B, C). Additional experiments using A01 monoculture were conducted to reconstruct this stable period, demonstrating that A01 continues to metabolize nearly 60% of glucose into glutamate, aspartate, and pyruvate, secreting them, possibly providing growth for B01 in the stable period (Figs. 4F and 5E). Therefore, the emergence of the stable period stems from the secretion of these metabolites, along with potentially other compounds, in response to acid stress. This phenomenon has been elucidated as a memory effect exhibited by cells under conditions of elevated acid stress45. Our model was set up in the general framework of a consumer-resource model: LM takes up glucose with rate \({\mu }_{{{{\rm{M}}}},{{{\rm{G}}}}}\), excretes lactate with rate \({\mu }_{{{{\rm{M}}}},{{{\rm{E}}}}}\), respectively, and grows (or dies) at rate \({\lambda }_{{{{\rm{M}}}}}\); A01 excretes acid-induced metabolites at rates \({\mu }_{{{{\rm{A}}}},{{{\rm{M}}}}}\) and grows with rate \({\lambda }_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\); B01 grows with rate λB,A detailed explanation of population dynamics can be found in the Supplementary Notes 3-6. Depending on the intensity of acid stress and nutrient supplementation, our model demonstrated four generic physiological processes in co-culture resulting from growth and cross-feeding, as we describe below (Fig. 6C):

-

1.

Logarithmic growth: at low lactate concentrations, B01 grows exponentially despite the presence of competitive interactions of A01, and these dependencies are characterized by the Monod growth functions; see Supplementary Note 3 for a full description.

$${R}_{B}={R}_{B,\,G}f\left(\frac{G}{{K}_{B,G}}\right)-{R}_{B,{Cs}}f\left(\frac{{Cs}}{{K}_{B,{Cs}}}\right)$$(1)Where \({K}_{i.{n}}\) is the Monod constant, and \(f(x)\) describes the Michaelis dependence on the substrate concentration.

-

2.

Acidification-induced stable stage (growth arrest): at the initial stage of high lactate concentration and limited metabolite availability, B01 experiences a constant rate of decline without nutrient consumption; see Supplementary Note 4 for a full description.

$${R}_{B}={\mu }_{B,G}={\mu }_{B,M}=0$$(2) -

3.

Synergistic antacid tolerance: At the intermediate stage of high lactate concentration, crucial for cooperative stress tolerance, A01 exhibits a cooperative mechanism where it produces public goods such as pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate, which are excreted. B01 can utilize these metabolites to maintain viability, accompanied by low glucose consumption. There is a lag period in the production and utilization of these metabolites, with a low rate of metabolite consumption during this stage; see Supplementary Note 5 for a full description.

$${R}_{B}=0$$(3) -

4.

Regrowth: at the later stage of high lactate concentration, B01 can grow but requires public goods. This simultaneous coexistence of lactate and cross-fed metabolites is modeled by the Monod functions; see Supplementary Note 6 for a full description.

Where \({{R}_{B,{Cs}}}^{+}\) is the growth rate in this stage. \({K}_{B.{i}}\) is the Monod constant.

The model quantitatively captured the processes and dynamics of co-culture consortia, showing distinct species dominance at different stages in the co-culture (Fig. 6C). These phases of differential dominance served as a pivotal factor in sustaining the coexistence of the two species, aligning with earlier investigations into growth dynamics (Figs. 3C, E, and 4D). Given that these phases arose from interactions between diverse physiological and metabolic states of the two species, encompassing factors such as the timing and quantity of major public goods proximal to the lactate peak and the population density of each species (Fig. 6B, C), their significance was likely amplified in more intricate communities. The observation of coexistence may depend on species abundance, interactions, nutrient levels, and environmental conditions during the process, which generates different species dominances at different time windows (Figs. 4D and 6C), facilitating stable coexistence across the community—a dynamic process that differs from the steady-state models commonly used in microbial ecology studies46,47.

The similarity of acid stress-induced cross-feeding and coexistence between bacteria and fungi

To verify the generality of the stress-induced cross-feeding scheme, we selected LABs and yeasts from the microbial consortium of the gut, another typical habitat for acid stress48, from different environmental sources than the previous experimental strains (Table S2). A species from the LAB was paired with a species from the Saccharomycetaceae family, with the former favoring growth on sugars and amino acids, while the latter thrives on sugars and acids49. When Lactococcus lactis JGB19 (LJ9), from the Lactococcaceae family, was grown in CDMG liquid medium with and without 100 mM lactate (see “Methods”), LJ9 monocultures grew at high ODs in lactate-free medium and ceased at low ODs in lactate-containing medium (Fig. S29A). Analysis of the spent medium from the monoculture of LJ9 revealed no accumulation of pyruvate acid, aspartate, and glutamate (Fig. S29B). Similarly, we cultured Saccharomyces cerevisiae Y2-7 (SY2-7) in CDMG liquid media with and without 100 mM lactate; the biomass of SY2-7 monoculture in the lactate-free medium was higher than that in the lactate-containing medium (Fig. S29C). Analysis of the spent medium from SY2-7 monoculture containing lactate revealed an accumulation of pyruvate acid, aspartate, and glutamate (Fig. S29D). Importantly, LJ9 had a growth rate higher than SY2-7 and a tolerance lower than SY2-7, characterized by complementary growth rates (Figs. S29A and S29C). Furthermore, co-culturing SY2-7 with LJ9 in CDMG liquid medium containing 100 mM lactate prolonged saturation OD by 1.1–1.4-fold and 2.3–2.6-fold, respectively, compared to monocultures of LJ9 and SY2-7. These results suggested the probability of lactate stress-induced cross-feeding in co-cultures (Fig. S30A).

To verify the occurrence of cross-feeding, a 2 µL mixed suspension (OD600 = 0.2–0.3) containing equal amounts of LJ9 and SY2-7 was co-cultured at 2.5 cm to the right of the producer LM to analyze the growth and metabolic dynamics (see Fig. 3A for inoculation method). In marked contrast to the results of cooperative interactions in liquid cultures, competitive interactions were observed within 24 h of co-cultivation on agar plates, with the biomass of the mixed co-cultures of LJ9 and SY2-7 being lower than that of their respective co-cultures with LM (Comparing Figs. 7A with S30B), consistent with the previous results of spatial structure environment promoting the interaction evolution25. The biomass dominance of the two species flipped at 24 h of co-cultivation with a corresponding lactate content of 68.8 mM (Figs. 7A and 4E). Specifically, faster-growing, intolerant LJ9 dominated for the first 24 h and slightly decayed in the following 6 h (Fig. 7A, Orange circle), while slower-growing, tolerant SY2-7 surpassed LJ9 at 24 h, then continued to rise and reached its maximum biomass at 30 h (Fig. 7A, Red circle), at which time lactate was also close to its maximum content, 98.2 mM (Fig. 4E). Importantly, LJ9 still exhibited regrowth within 27–33 h, with its density increasing by 1.54 × 108 for 132% of the 24-h biomass (Fig. 7A, Gray shaded area). HPLC analysis of the medium showed that several public goods, including pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate, accumulated to high concentrations at 27 h of co-culture (Fig. 7B). The subsequent disappearance of these public goods coincided with the recovery phase of LJ9 growth, while the density of SY2-7 remained unchanged (Fig. 7A, B, Gray shaded area). These observations closely resembled the dynamics observed in A01-B01 co-culture (Fig. 4D, F, Gray shaded area), despite the vastly different properties of these strains. To verify that these public goods produced by SY2-7 restored the growth of the LJ9 stalled by acid stress, we re-inoculated LJ9 using the spent medium from a 27-hour co-culture to monitor its growth and uptake characteristics (see “Methods”). The results showed that the spent medium was able to promote the growth of LJ9 (Fig. S30C), while the concentration of these public goods decreased (Fig. S30D). Moreover, we cultured monocultures of LJ9 in 100 mM lactate-acidified CDMG liquid medium with and without the addition of pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate (see “Methods” and Fig. 5A). The results again followed that LJ9 can only grow under high lactate stress in the presence of public goods, which stems from uptake originating from public goods (Fig. 7C, D). Consistent with predicted universality, stress-induced cross-feeding of public goods facilitated interspecific cooperation and stress tolerance, leading to the coexistence of consortia under stress within 33–39 h of co-culture, with a biomass ratio (fold change R = LJ9/SY2-7) close to 0.8 (Fig. 7A, Yellow shaded area).

A Counts of SY2-7 and LJ9 cells at different times when equal proportions of SY2-7 and LJ9 were inoculated 2.5 cm to the right of the producer LM and co-cultured on CDMG agar plates. Inoculation was shown in the cartoon diagram of Fig. 4A. The gray shaded area indicates the phase where LJ9 biomass increases again. The red arrow indicates when regrowth started. B HPLC-detected pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate concentrations in extracts from co-culture regions of SY2-7 and LJ9. Based on the growth process of LJ9, it was classified into several physiological processes (Red numerical markers), including logarithmic growth (1. LG in Fig. 7A), growth arrest (2. GA in Fig. 7A), synergistic antacid tolerance (3. SAR in Fig. 7B), and regrowth (4. RG in Fig. 7A). The gray-shaded area indicates the trend of these metabolites during the regrowth of LJ9 in Figure A. Arrows have the same meaning as in Figure A. C OD values of LJ9 monocultures in 100 mM lactate-acidified CDMG liquid medium supplemented with different concentrations of public goods (PG). To ensure that the species could grow in this high lactate medium, the inoculum amount was increased to achieve a final OD600 of 0.32. The value of biomass (OD600) was expressed as the assay value minus 0.32. The detailed method is shown in Fig. 5A. Specific concentrations supplemented are shown in Table S4. D Changes in the content of public goods were detected by HPLC when LJ9 was monocultured in the 100 mM lactate-acidified CDMG medium with the addition of public goods, including 4.2 mM pyruvate, 2.6 mM glutamate, and 2.2 mM aspartate. The detailed method is shown in Fig. 5A. The methods and meanings in E–H were the same as those in Figure (A–D) except that the glucose-containing medium (CDMG) in Figure (A–D) was replaced with a sucrose-containing CDM medium (CDMS) in Figure (E–H). Data represent the average of three biological replicates; see source data for SD.

Glucose is the most commonly used monosaccharide in glycolysis31, and its metabolism results in the stable secretion of organic acids during the growth of the acid-producing strain LM (Fig. 4E). To determine whether the acid-induced cross-feeding established between the paired growth species here applied to lactate accumulation in other ways, we monitored the growth curves and uptake/excretion properties of co-cultivated strains in CDM medium containing 2% sucrose (CDMS), a widely available disaccharide50. Here, LM was selected as the sugar-consuming acid excretor (Fig. S31A), while LJ9 and SY2-7 were chosen as the stressed species (Fig. S31B). When LJ9 was monocultured in the CDMS liquid medium with 100 mM lactate, growth again ceased, and there was no excretion of public goods (Figs. S31C and S31D). The results of SY2-7 monoculture in CDMS liquid medium with 100 mM lactate showed that sugar resources affected the growth of SY2-7 (Comparing Figs. S29C and S32A) as well as the levels of public goods (Comparing Figs. S29D and S32B). Furthermore, HPLC analysis of the spent culture medium showed the accumulation of these public goods (Fig. S32B). When we again focused on the growth and metabolic dynamics of ternary co-cultures, the growth of LJ9 also followed the pattern of logarithmic growth, growth arrest, synergistic antacid tolerance, and regrowth (Fig. 7E, F, Red numerical markers), although the sugar types differed (Fig. 7A, E). Furthermore, the increased biomass of LJ9 benefited from the uptake of public goods (Fig. 7G, H). To further confirm that the observed acid-induced cross-feeding commonly occurs between unrelated species in acid-stressed environments, we repeated the experiments of ternary consortia using S. cerevisiae JGF28 (SJ28) and S. cerevisiae XZFM13-1 (SX131) from the same source as SY2-7 on CDMS agar plates: the pattern of logarithmic growth, growth arrest, synergistic antacid tolerance, and regrowth of LJ9 reappeared in this case (Fig. S33, Red numerical markers), matching the dynamics of stress-induced cross-feeding (Figs. 4, 7, and S33). Thus, these results demonstrated the predictive generality of the stress-induced cross-feeding phenomenon, facilitating interspecific cooperation and coexistence.

Discussion

Acid stress is a major challenge for microbes and is prevalent in natural habitats (soils and sediments), engineered systems (fermented substrates and bioreactors), and the intestines28,29,51,52. Typically, acid stress is dynamic, changing over both short and long timescales with the fluid dynamics within habitats and increasing global acidification1,7,12,24,33,53. A large number of microbial species form interacting communities in acid-stressed environments. Predicting and regulating microbial colonization and coexistence in host-associated communities or engineering industrial communities remains challenging, as how microbial species respond physiologically and metabolically to changes in acid stress to enhance population survival, fitness, and resilience remains largely unknown. We systematically investigated the colonization, growth, metabolism, and interactions of free-living microbiota in response to acid stress changes, revealing that acid stress changes dynamically regulated competitive and cooperative interactions. Slower-growing species were favored under increased acid stress, and their excretion of public goods led to cross-feeding, interspecific cooperation, and coexistence.

Recent studies have shown that microbial colonization follows simple and quantifiable structural paradigms3,35. Our research also supports this view. Acid stress-induced coexistence was shown to be spatiotemporally ordered in the interactions of ternary and quaternary microbial consortia with different initial strain ratios, always around a stable distance of 2.5 cm (λx) (Fig. 3D, E). Moreover, range expansion and stable coexistence of natural microbial communities are ecological processes that reveal the interactions that drive colonization behavior54,55. To understand habitat colonization based on interactions, one first needs to disentangle the range and intensity of inter-individual interactions as a function of their spatial position. Then, one needs to disentangle how these interactions scale up to give rise to ecological outcomes at the community level35,56. Our results show that binary microbial consortia can respond to lactate stress over a centimeter-length range of 0–4.5 cm (Fig. 2D). Interactions within this range were not limited to classical competition or cooperation, but they exhibit a shift from competition to cooperation (Fig. 3F), leading to the interaction dynamics of ternary and quaternary microbial consortia in spatially structured environments. However, natural microbial communities typically face multiple and overlapping stresses and interact with a wider range of species, whereas we have focused on single-stress conditions and a few species. Therefore, the construction of multi-species and higher-order microbial consortia is necessary to capture the complexity of natural microbial communities and to further validate their colonization and coexistence under multiple stresses.

A strong phenotype-based description of microbial communities would need to take into consideration both the growth rates and tolerances of the species in the community29,57. We observed that acid-tolerant strains exhibited lower growth rates, whereas fast-growing strains showed reduced tolerance (Figs. S11 and S12), revealing a fundamental trade-off between stress tolerance and reproductive efficiency. This trade-off is a classic premise in game theory, where the ‘tolerant’ strain incurs a cost for protection, while the ‘sensitive’ strain relies on rapid growth under permissive conditions58,59, which can lead to complex dynamics as observed in co-culture consortia. When high stress was obtained close to the producer LM, the more tolerant A01 occupied nearby spatial niches, and the faster-growing B01 occupied distant spatial niches where stress was low (Fig. 3B–D). Thus, the trade-off between growth rates and acid stress tolerance enables alternative strategies that promote population growth, leading to greater population gains in overall fitness. Intuitively, there is a unidirectional ecological filter along the stress gradient that makes it easier for tolerant species to successfully colonize the habitat12,40. However, ecological communities in habitats are often diverse, with species differing widely in their phenotypes60. How these phenotypically distinct species coexist in habitats has been an attractive question. Stress-based changes in growth rates among different species explain coexistence, but the coexistence also depends on their dynamic interactions and niche differentiation21. Our results suggest that microbial species can adjust their plasticity or evolve to enhance survival in response to environmental conditions. They exhibited competitive interactions to occupy niches under low stress, while also resisting invasion through cooperative interactions under high stress, while also resisting invasion through cooperative interactions under high stress (Figs. 3 and S15-S17).

Tracking the temporal dynamics of communities over coexistence distances revealed that the level of stress influences the magnitude and direction of microbial interactions. When the community was exposed to non-high stress (lactate <68.8 mM), interactions were dominated by competition (Fig. 4D); whereas, when the community was exposed to high stress (lactate > 98.2 mM), cooperation shifted to a dominant role (Fig. 4D, F). The shift from competition to cooperation increased community resilience under stress. This is consistent with the stress gradient hypothesis (SGH), which suggests that the relative frequency of synergistic and competitive interactions in a community varies inversely with the abiotic stress gradient61,62. However, the SGH focuses on systems where all species can survive across a range of a defined ‘focal’ environmental stress61,62. Acid stress rise (lactate of 68.8–98.2 mM) in the spatially structured environment, in contrast, constituted an selective event that acted as a selection stress on the microbial community, thereby eliminating the non-tolerant and low-tolerance species. In this scenario, A01 maintained viability while B01 started to decay (Fig. 4D). The regenerative and coexistence behavior of B01 in high-stress environments is due to the interspecific cooperation resulting from the cross-feeding of public goods (Figs. 4D, F, 5B, C), and the excretion of these public goods may be due to the physiological and metabolic responses of the microbial consortia to stress.

Acid stress-induced cross-feeding of public goods appears to be mechanistically collaborative. Acidifying environments in natural and industrial habitats place microbial communities under stress when acid producers excrete more acid than the habitat’s buffering capacity30. Since low-tolerant strains cannot grow in high-stress environments, the key issue is how co-cultures such as A01 and B01 in CDMG can stably coexist under acid stress. The most likely mechanism is that certain species within the community can secrete public goods, which other species then utilize to increase their biomass. The metabolic collaboration that occurs between A01 and B01 cocultures in acid stress was revealed by detailed quantitative results, where A01 regenerated B01 under stress by excreting public goods, including pyruvate, glutamate, and aspartate, and cross-feeding them to B01 (Figs. 4 and 5). We tested whether the presence of public goods affects stress intensity through public goods supplementation, spent medium, and inhibitor experiments (Figs. 5, S23, and S25). The results showed that the presence of public goods influenced the stress intensity, mitigating its effect and enabling low-tolerant species to survive under the same intensity. Moreover, stress is a key factor in the changes observed in microorganisms with different growth rates. High stress induces slower-growing, stress-tolerant species to produce beneficial metabolic by-products for faster-growing, stress-intolerant species, thereby promoting interspecific cooperation and coexistence. This finding aligns with previous results demonstrated in soil and marine environments29,38,63. Despite the complexity of metabolic interactions, the main observed dynamics can be captured by parametrically constraining the kinetic model (Fig. 6). Based on the resource-consumer model, we quantitatively captured the different physiological states occurring at different stages of acid stress-induced cross-feeding between A01 and B01 co-cultures (Fig. 6A). As acid stress and its intensity gradient occurred, co-cultivation resulted from the interaction of these different physiological states, and niches of the community members at different stages remained generated by homeostatic growth (Fig. 6C).

Cross-feeding public goods is a predicted universal protocol for coping with stress and occurs in co-cultures (Fig. 8). Co-culture experiments in the closely related A01 and B01 from fermented food isolates and the phylogenetically distant LJ9 and SY2-7, SJ28, and SX131 from gut isolates demonstrated that acid stress-induced cross-feeding has similarities in unrelated environments (Figs. 4, 5, and 7). Recent studies have shown similar phenotypic complementarity in ocean isolates53, and stress-induced cross-feeding promotes cooperation and coexistence of these co-cultures. Selection for carbon source and metabolic direction may have facilitated cross-feeding between species64, but such results have not been demonstrated for the most common monosaccharides (glucose) and disaccharides (sucrose). Both of these sugars could be converted into valuable metabolic by-products (public goods) that exhibited cross-feeding in acid-stressed co-cultures (Fig. 7). Our results provided a physiological foundation for the general concept of microbial stability facilitated by cross-feeding among free-living microorganisms. As respiration becomes limited in acid-stressed species, leading to an increase in glycolytic flux, this results in the accumulation of metabolites that are reversibly linked to the TCA65,66,67. The excretion of these metabolites to release flux and thus sustained energy allows the slower-growing, tolerant A01 or SY2-7 to maintain viability even under high stress (Figs. 4 and 7). The excretion of these metabolites was not a minor response to stress; instead, A01 or SY2-7 actively took up carbon sources from the medium and excreted them with 50-70% C-atoms, enabling faster-growing, intolerant B01 or LJ9 to take them up and grow again under high stress, thereby promoting community stability and coexistence (Figs. 4C and 5E). In all studies, stress was a prerequisite for metabolite excretion. Other stressful environments, such as temperature or salinity, are also present in the gut, compost, soils, and oceans23,29,53,68. Due to similar stresses, slower-growing and stress-tolerant species may also be selected to provide public goods to other community members, thus promoting colonization, adaptation, and coexistence of populations in these stressful environments.

The left panel shows growth-based competitive inhibition of two phenotypes under low lactate stress. The right panel shows mechanisms for interspecific cooperation to promote stress-resistant coexistence under high lactate stress: slower-growing, tolerant species increase glycolytic fluxes and ATP synthesis to resist high acid stress, while secreting public goods to release fluxes. The faster-growing, intolerant species use these public goods to promote their growth and resist high acid stress. In turn, consumption of these public goods further promotes increased glycolytic fluxes and ATP synthesis for slower-growing, tolerant species. This interspecific cooperation promotes stress tolerance and the coexistence of the two phenotypes. Black arrows indicate the processes by which metabolism or reactions occur. Blue arrows indicate increased metabolism or responses in high acid stress compared to low acid stress. Purple colors indicate cross-feeding from slower-growing, tolerant species to faster-growing, intolerant species. Red T’s represent inhibitory interactions, and red bidirectional arrows indicate cooperative facilitation. Although only metabolic interactions are emphasized in the models, gene regulation may also play an important role.