Abstract

The global shift toward solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind power is crucial to climate mitigation, yet climate change may intensify extreme low-production (ELP) events and affect power reliability. Here, we assess future ELP changes under low (SSP1-2.6), intermediate (SSP2-4.5), and high (SSP3-7.0) greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions scenarios. Even under SSP1-2.6, rising ELP risks are projected to affect more than one-third of global regions, expanding to nearly two-thirds under SSP3-7.0, regardless of whether systems rely on PV, wind, or both. Increases in ELP for wind power are nearly inevitable, with over 75% of currently installed areas experiencing 14.0–24.5% greater production anomalies by the late century. PV power diverges strongly across scenarios, shifting from a 14.8% decrease in anomaly under SSP1-2.6 to a 26.4% increase under SSP3-7.0, particularly in East Asia. Additionally, climate-induced risks disproportionately narrow the benefits of PV development in low- and lower-middle-income economies, where ELP risks rise at 1.8 times the global rate under SSP3-7.0. Our results underscore the need for coordinated mitigation and adaptation to secure power reliability in a changing climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renewable energy is supporting ambitious global warming mitigation targets1, with solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind expected to become dominant power sources in the coming decades2. According to projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA), the share of electricity generation from wind and PV power could reach 68% in the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario (NZE)3. Such growing dependence on wind and solar PV power introduces exposure to climate-induced underproduction4,5,6, leading to both frequent minor shortages and rare but severe events7,8,9,10. While most shortages can often be managed through multi-energy scheduling and energy storage11, severe events may quickly exhaust available reserves and impose substantial social and economic costs12,13,14.

High temperatures15,16, aerosols17,18, and cloud conditions19,20 have been shown to depress PV power production, while high-pressure systems induce very low wind speeds by weakening pressure gradients5,21. These meteorological drivers—already influenced by anthropogenic climate change22,23,24,25,26,27—are likely to increase the occurrence of extreme low-production (ELP) events in the future28. Although previous studies have advanced the understanding of how climate change affects solar PV and wind power, one or more of the following limitations remain. First, most work has focused on general trends in resource variability8,9,22,23,26, whereas only a few examine the ELP risks for solar PV29,30, often overlooking key drivers such as air pollutant emissions. This limits insight into how climate change affects ELP risks for both technologies—an increasingly important issue as more countries adopt integrated wind–solar strategies. Second, many studies assume idealized siting or optimal deployment, overlooking the spatially uneven and often non-optimal deployment of real-world installations31. Finally, studies based on power system planning models propose ways to design resilient wind-solar energy systems that can adapt to future extreme weather10,32,33,34, but these efforts are usually region-specific and tend to focus on high-income economies.

Here, we systematically assess the global climate-induced impact on the ELP events for solar PV and wind power in a warmer future. Using a percentile-based approach, we define an ELP event as one or more consecutive days with power production below the 10th percentile (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 11 for details). Under baseline climate conditions, this corresponds to approximately 10% of days exhibiting extreme low production. The threshold is derived from power production anomalies for each calendar day during the historical baseline period (1985–2014), where anomalies are defined as deviations from the climatological mean. By applying the threshold consistently across all future scenarios, we track how the production anomalies evolve along different climate pathways. These changes reflect the combined effects of climate-induced shifts in both the mean and variability of power generation. For instance, decreases in mean output, increases in variability, or both can result in more frequent ELP occurrences.

We characterize ELP events using frequency, duration, intensity, and production anomalies to capture climate change impact on their severity. The power production anomalies during ELP events are then aggregated to the annual level as a proxy for system-level risks, providing an integrated measure of extreme shortfalls. Using a spatially explicit approach that integrates high-resolution installation data, we quantify the climate-induced production losses and spatial patterns of the risk for PV and wind power—individually and in combination. Potentially exploitable areas are also included in our analysis to show future changes in the available areas, providing a more comprehensive view of regional vulnerabilities. By applying contrasting climate pathways, we quantify the potential outcomes under three scenarios: optimistic (SSP1-2.6), intermediate (SSP2-4.5), and high (SSP3-7.0) emission35. Notably, unlike other high-warming scenarios, SSP3-7.0 has a distinctive design characterized by high aerosol emissions to explore the diversity of impacts36. The findings contribute insights and knowledge on how climate change will impact the ELP events for solar PV and wind power, with particular emphasis on real-world production regions.

Results

Climate change causes widespread and pronounced ELP change globally

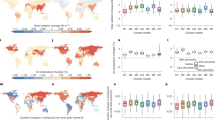

As global warming intensifies, the significant and robust upward trend in ELP is projected to occur across solar PV power, onshore wind power, and offshore wind power (Fig. 1). Under the SSP3-7.0 scenario, the power production anomaly during ELP events is rising globally at an average rate of 3.8 kWh per kW (p < 0.01) per decade for solar PV power, 2.7 kWh per kW (p < 0.01) for onshore wind power, and 1.3 kWh per kW (p < 0.01) for offshore wind power, respectively. Given the current installed capacity of solar PV power and wind power, this trend translates to an additional 116.4 GWh and 942.4 GWh anomalies per year, respectively. By the mid-21st and late-21st century, the anomalies during ELP events for solar PV are projected to increase 15.8% and 26.4% compared to the historical period, respectively, reaching 35.9 TWh and 39.3 TWh annually. Wind power is expected to exhibit even larger gaps, with anomalies increasing by 10.1% and 22.3%, reaching 245.9 TWh and 273.2 TWh per year. Notably, these additional anomalies will scale further with the continued expansion of installed capacity.

a–c global trends in the anomalies during ELP events for solar PV power (a), onshore wind power (b), and offshore wind power (c). d–f global trends in the number of ELP days for solar PV power (d), onshore wind power (e), and offshore wind power (f). g–i global trends in the ELP event intensity for solar PV power (g), onshore wind power (h), and offshore wind power (i). The solid line represents the multi-model mean projection, and the shadow represents the range projected by the multi-model 10th–90th percentile.

Change in the number of ELP days — the product of frequency and duration — dominates the anomalies change in solar PV power, while changes in event intensity are little (Fig. 1d–i). The increase in ELP days is largely due to the increase in event frequency, followed by a modest increase in event duration (Supplementary Figs. 12–19). The global average of ELP days is expected to increase from 37 to 56 days by the late-21st century, while the intensity remains at 32–34%. In contrast, the ELP days for wind power only show a modest increase. However, its inherently high variability maintains the event intensity at a consistently high level (86% on average) (Fig. 1h, i) —meaning even a small extension in event duration can introduce substantial additional anomalies.

Beyond the increasing global risk, the severity of events is also becoming increasingly pronounced (Supplementary Figs. 20–23). For solar PV, prolonged downturns may occur, yet the extreme anomaly is relatively mild. We observe that the longest event durations in current installed areas exhibit a threefold prolongation (96 days) compared to the historical period (27 days), while the daily peak anomaly rises from 37 to 104 kWh per kW. In contrast, wind power is projected to experience much more intense anomalies due to its high event intensity, making it particularly susceptible to severe supply disruptions. The peak anomaly for onshore wind power increases from 239 to 337 kWh per kW, which is equivalent to at least seven additional days of complete power disruptions. Offshore wind power is comparatively less vulnerable, with its largest event anomaly increasing from 77 to 93 kWh per kW. The longest event duration doubles from 19 to 45 days for onshore wind power, while for offshore wind power, it increases from 12 to 32 days.

The discernible difference in global trends of ELP change between contrasting scenarios is particularly pronounced for PV power (Fig. 1). Moving from the SSP3-7.0 to the SSP1-2.6 scenario, the projected anomaly in solar PV power decreases by 34% on average by the late-21st century, accompanied by a significant downward trend. In contrast, the difference for wind power is projected to be only 5% on average. Projected trends in solar PV power are robust against climate models spread, with signal-to-noise ratios (SNR, see “Methods”) exceeding 1 in all scenarios. The inter-model spread largely originates from differences in response to surface shortwave radiation, particularly those associated with aerosol and cloud-related processes29. Projections for wind power exhibit greater inter-model variability, with SNR exceeding 1 only under the SSP3-7.0 scenario. This divergence is partly driven by differences in response to atmospheric circulation and associated anomalies27,37.

Future pathways shape solar PV power production more than wind power

Spatial analyses reveal the pronounced regional disparities. For solar PV in currently installed regions, scenario sensitivity is particularly notable, with pathway choices potentially leading to markedly divergent outcomes. In comparison, wind power exhibits near-inevitable ELP increases across all scenarios, persistently affecting both operational wind farms and potentially exploitable areas (Figs. 2, 3).

a, b Spatial distribution of change in anomalies during ELP events under different scenarios and periods. The map is based on the multi-model mean projection. The slash indicates regions with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) greater than 1, suggesting robust multi-model projections. c Spatial distribution and average power production potential of installed areas and potentially exploitable areas. Installed areas refer to regions with detected PV panel installations, while potentially exploitable areas are those without installations but with development potential based on land use and topographic suitability (see “Methods” for details). d Histogram of change in anomalies during ELP events in installed and potentially exploitable areas. Histogram distribution is plotted based on the multi-model mean projection under different periods and scenarios. Colors in panel (d) correspond to panel (c), with purple denoting currently installed areas and pink indicating potentially exploitable areas.

a, b Spatial distribution of change in anomalies during ELP events under different scenarios and periods. The map is based on the multi-model mean projection. The slash indicates regions with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) greater than 1, suggesting robust multi-model projections. c Spatial distribution and average power production potential of installed areas and potentially exploitable areas. Installed areas refer to regions with detected wind turbines, while potentially exploitable areas are those without installations but with development potential based on land use and topographic suitability (see “Methods” for details). d Histogram of change in anomalies during ELP events. Histogram distribution is plotted based on the multi-model mean projection under different periods and scenarios. Colors in panel (d) correspond to panel (c), with purple denoting currently installed areas and pink indicating potentially exploitable areas.

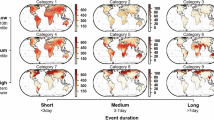

According to multi-model mean projection under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, approximately 70% of global land is expected to experience the increased ELP of solar PV power, respectively (Fig. 2a, b). The change in anomalies during ELP events exhibits a wide variation globally, ranging from – 32.6% to + 239.6%, with a prominent and robust increase in Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, South Asia, Central Asia, and western North America. Although most of the global land is affected by increased ELP, 69.2% and 71.9% of PV-installed areas are expected to experience decreased ELP by the mid-21st century and the late-21st century, respectively, which is mainly distributed in East Asia, Europe, and North America (Fig. 2c, d).

The SSP3-7.0 pathway — characterized by both higher rates of global warming and weak air-quality controls36— substantially exacerbates the ELP risk of solar PV power. By the mid-21st century, areas experiencing an increase in ELP events expand to 82.8% globally, reaching 87.6% by the late-21st century. In PV-installed areas, the affected proportion rises to 57.1% and 61.2%, respectively. In the SSP1-2.6 scenario, 82.3% and 93.2% of the PV-installed areas are expected to experience decreased ELP by the mid-21st and late-21st century due to strong climate mitigation and air pollution control, respectively. Correspondingly, the anomalies during ELP events are projected to decrease by 21.2% and 32.8%, reaching 7.6 TWh and 12.9 TWh annually. East Asia is particularly sensitive, showing one of the largest ELP declines under the SSP1-2.6 scenario and the strongest increases under the SSP3-7.0 scenario (Fig. 2a, b).

Obvious divergences are shown in PV-installed areas even under similar warming levels (Supplementary Fig. 24). For instance, at + 3 °C global surface air temperature (GSAT) warming, PV anomalies range from – 23.6% in the SSP1-2.6 scenario to + 13.2% in the SSP3-7.0 scenario. This contrast aligns with recent evidence that strict air quality regulations under SSP1-2.6 enhance surface solar radiation, while lax policies in SSP3-7.0 amplify aerosol- and cloud-induced losses38,39. Critically, these differences are tied to socioeconomic pathways and regional development disparities—such as legislative rigor and technological adoption40, placing existing PV installations at disproportionate risk from socioeconomic-driven uncertainties. As the largest PV-installed region, changes in anomalies during ELP events in East Asia could reach + 28.6% under the SSP3-7.0 scenario, compared to – 16.2% under the SSP1-2.6 scenario.

For wind power, a counterbalance leads to a weak global trend—growth in the Northern Hemisphere is roughly offset by a decline in the Southern Hemisphere (Fig. 3a, b). Spatially, approximately 66.2%–73.4% of the global land is expected to experience the increased ELP of onshore wind power, with small differences between scenarios and periods. For offshore wind power, 53.5%–63.8% of global offshore areas are projected to see an increase in ELP. Change in the anomalies during ELP events ranges from – 79.6% to + 150.3% for onshore wind power, and – 46.7% to + 197.4% for offshore wind power. Areas affected by increased ELP of onshore wind power over 90% in the northern part of 30°N, while areas widely affected by increased ELP of offshore wind power include the European coastal region (99.0%) and the American coastal region (over 80.1%). Hotspots for prominent ELP growth of wind power include the United States, western China, the east-central seas of Japan, the western seas of India, and the Somali Peninsula of Africa. However, it is worth noting that projections exhibit great inter-model uncertainty under SSP1-2.6 and SSP2-4.5 scenarios, whereas more robust signals emerge under the SSP3-7.0 scenario, particularly north of 30°N.

Approximately 92% of areas hosting wind turbines are distributed in the Northern Hemisphere – primarily in the central United States, Europe, and East and South Asia – leading to inevitable impact (Fig. 3c). Across scenarios and periods, 78.8–91.4% and 75.8–93.9% of onshore- and offshore-installed areas are projected to experience increased ELP, respectively (Fig. 3d). On average, anomalies during ELP events are expected to increase by 7.8–25.6%, approximately three times the global average. For potentially exploitable areas, while 29.8–37.7% show a decrease in ELP, a substantial portion is located in regions near the equator with very low wind power production potential, limiting the practical benefits (Fig. 3a–c).

The dual ELP risk of solar PV and onshore wind power grows unevenly

By the mid-21st century, 40.6%, 53.2%, and 63.6% of onshore areas — including installed and exploitable areas — are projected to encounter increases in ELP risk for both solar PV and wind power under the SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP3-7.0 scenarios, respectively (Fig. 4a). This suggests a dual risk if PV panels and wind turbines are co-located in these areas. According to the SSP2-4.5 scenario, South Asia, Central Asia, East Asia, Eastern Europe, and North America emerge as the top five regions most affected by such dual risk (Fig. 4b). In South Asia, nearly all of the onshore areas are expected to face dual risk of increased ELP across all three scenarios. In East Asia, Central Asia, North America, and Eastern Europe, the proportion of affected areas ranges from 65.8% to 75.7%.

a Spatial distribution of combinations of future changes in ELP of solar PV and onshore wind power under different scenarios. b the regional risk structure under different scenarios. The ranking is based on the total proportion of onshore areas showing dual increased ELP risk (purple) under the SSP2-4.5 scenario. c The distribution of currently mixed-installed areas (where PV panels and wind turbines coexist) and their risk structure under different scenarios, along with the net changes in production anomalies during ELP events across major regions. All results are presented based on the multi-model mean projection. Only installed and potentially exploitable areas are considered.

Western Europe, Southern Europe, South Africa, Central America, and Australia/New Zealand emerge as the five regions least affected by dual risk. In Western Europe and Southern Europe, nearly all areas experience an increase in ELP for wind power but a decrease in ELP for solar PV power, potentially offsetting the overall impact on combined wind–solar systems. In South Africa, Central America, and Australia/New Zealand, 33.7% to 85.4% of regions show a decrease in dual ELP for solar PV and wind power, while another 60.9% to 11.0% show a decrease in ELP for either wind power or solar PV alone.

Co-location of PV panels and wind turbines is most prevalent in East Asia and Europe. As shown in Fig. 4c, 42.5% of current mixed-installed areas are concentrated in Western, Southern, and Northern Europe, followed by East Asia (32.4%) and North America (8.4%). Although the projected decrease in ELP risk of solar PV could offset the increase in ELP risk of wind power, the extent of this compensatory effect depends strongly on the installed capacity structure. Based on current global installations, the net increase in anomalies during ELP events is estimated at 11.2–23.3 TWh. Regionally, a clear imbalance exists. In Europe and North America, decreases in PV-related risk are more substantial, leading to moderate net increases (0.11–3.55 TWh). East Asia remains the most vulnerable region, exhibiting the largest net increase due to high installed capacity, high wind-related risks, and limited solar PV compensation potential, together with uncertainty in future socioeconomic pathways. Under different scenarios, the proportion of mixed-installed areas exposed to dual ELP risks ranges from 6.3% to 92.8%, with net increases of 7.42–18.5 TWh.

Notable divergence is also observed across income groups. As shown in Fig. 5, low- and lower-middle-income economies are more likely to be impacted by increased ELP for solar PV power, whereas high-income economies are more impacted by increased ELP for wind power. Interestingly, it’s the converse for resource endowments—low- and lower-middle-income economies have better solar resources and high-income economies have better wind resources. Specifically, 65% of low-income economies and 51% of lower-middle-income economies have higher solar PV production potential than the global average. However, 88–98% of land in low-income economies and 66–88% in lower-middle-income economies are projected to experience increased ELP for solar PV across three scenarios by the mid-21st century. For wind power, 74% of high-income economies have higher potential than the global average, compared to only 24–32% for the other three income groups. Nevertheless, 79–83% of areas are affected by increased ELP in high-income economies. While natural advantages and risks exist across income groups, low- and lower-middle-income economies face greater challenges in realizing their solar PV potential due to rising adaptation costs. In high-income economies, reductions in air pollution enhance irradiance, which can partially offset warming-induced losses in PV output. Such compensatory effects are limited in lower- and lower-middle-income economies, where weak pollution controls and intense warming homogenize risks (Supplementary Fig. 24).

a Average potential of power production of solar PV and onshore wind power between 1985–2014. b the risk structure classified by income group under different scenarios. All results are presented based on the multi-model mean projection. Only installed and potentially exploitable areas are considered.

Discussion

Based on multiple downscaled climate model simulations and high-resolution installation data, this study provides a spatially explicit and globally comparable assessment of climate change impacts on ELP events for solar PV and wind power. We use annual production anomalies to represent ELP risk and characterize ELP events by their frequency, duration, intensity, and cumulative anomalies. Our results show that growing ELP risks for wind power are nearly unavoidable, while those for PV can be substantially reduced through strengthened air quality control and climate mitigation, enhancing the potential to offset wind power shortfalls. As ELP risk increases, events become significantly more frequent and prolonged—PV power is more prone to long-time downturns, while wind power is more susceptible to severe supply disruptions. Regional disparities and vulnerabilities are projected to widen across socioeconomic pathways.

Notably, we find that the SSP3-7.0 scenario—characterized by high global warming and weak air pollution control—leads to widespread and substantial impacts on solar PV globally. These differences are especially pronounced in Asia, which has the largest installed capacity and is undergoing rapid development. Under the SSP3-7.0 scenario, South, Central, and East Asia face significantly increased ELP risks, primarily driven by limited pollution control and strong warming. In contrast, under SSP1-2.6, trends are reversed in East Asia, where strict air pollution control enhances irradiance and partially offsets warming-induced losses. Compared to earlier estimates based on RCPs29, the SSP–RCP framework reveals greater inter-scenario and inter-regional divergence. This stems not only from the broader range of air pollutant emissions coupled in SSP-based narratives but also from socioeconomic disparities in pollution control capacity. High-income economies are more likely to benefit from improved air quality and reduced ELP risks, while many lower- and lower-middle-income economies remain vulnerable due to persistent air pollutant burdens, stronger warming, and uncertain trajectories of environmental and technological development. These findings highlight the need for integrated and synergistic policy approaches that simultaneously tackle heat adaptation and air quality challenges—especially in lower- and lower-middle-income economies that either rely on solar PV power or offer significant potential for high-quality solar energy. For wind power, previous studies have shown that the impacts of climate change on long-term resource potential and variability are generally modest25,37,41. However, such average-based assessments may mask substantial increases in ELP events. Using an approach based on the detection of extreme events, we show a pronounced intensification of ELP conditions under a warming climate, particularly in event severity. Notably, the strong asymmetry between hemispheres of change in ELP closely mirrors that of mean wind power density25.

We highlight the necessity for planning and investments in risk adaptation. Although the extent of the impact is still uncertain due to a highly uncertain future pathway, most areas, particularly some resource-rich or densely populated regions, are expected to experience an unavoidable increased risk. Improving module efficiency is an effective way to increase generation and reduce costs, yet its mitigating effect during ELP events is limited (Supplementary Note 1). Some preparedness, such as capacity reserves and battery storage, is expected to become increasingly cost-effective in the future. This will help address more frequent ELP events with longer duration. In some regions, optimizing the mix of wind and PV capacities is a promising approach to offsetting the increased ELP risk for wind power with the decreased ELP risk for solar PV power. However, our findings should not be interpreted as evidence of real-time operational balancing, as the use of annual aggregates inherently limits the representation of temporal co-occurrence events. Further research is needed to assess the ability of climate models to reproduce the temporal co-occurrence of ELP events. In addition, the complexity of real-world development should be acknowledged. Even if some areas show positive change, it may not be sufficient to support the economics of electricity generation. The cost brought by the increased ELP versus the benefits of reducing ELP is also not yet fully clear. Examining these issues could provide more informed guidance for future energy policies.

Our estimates are subject to several potential limitations and uncertainties. While the downscaled climate data used in this study offers improved spatial resolution compared to raw outputs, its daily temporal resolution limits the ability to capture sub-daily variability in solar radiation and wind speed. This may lead to biases in regions with frequent cloud cover or pollution changes. Wind speed fluctuates more on hourly and even minute scales, which may introduce more biases using daily-scale input data. Our comparison shows that the main limitation arises from biases in estimating sub-daily wind speed distributions from daily means (Supplementary Note 2, 3). The assumed statistical distribution tends to overestimate the probability of both very low and very high wind speeds, which leads to an overestimation of event intensity. These biases are more pronounced in regions with low wind energy potential, where near-cut-in conditions are frequent, and in some mountainous areas where extreme winds inflate the climatological mean. Despite its limitations, the overall consistency in most regions with deployment potential supports the use of daily-resolution data as a reasonable approximation in this study (Supplementary Figs. 5, 6). Future work could improve accuracy by incorporating higher-resolution data.

To conclude, we emphasize the uncertainties and systemic risks associated with the transition to renewable energy under climate change. This study identifies global hotspots of change in ELP events for solar PV and wind power, and quantifies the divergent impact across different pathways and geographic regions. As the related risks vary widely across regions, the transition to renewable energy requires enhanced international cooperation. By pooling resources, expertise, and technological advances, countries can address these challenges more effectively and accelerate the adoption of renewable energy globally while ensuring that emissions are reduced sufficiently to avoid the worst scenarios.

Methods

Global climate model

We use the daily outputs from multiple climate models at a spatial resolution of 0.25 degrees, which are obtained from the NASA Earth Exchange (NEX) Global Daily Downscaled Projections (GDDP) dataset (NEX-GDDP)42,43. The NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset provides globally downscaled climate projections derived from the General Circulation Model (GCM) or Earth System Model (ESM) runs based on the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). It is designed to support research on climate change impacts at local to regional scales, particularly for processes sensitive to fine-scale climate gradients and local topographic effects. Through the Bias-Correction Spatial Disaggregation (BCSD) method, these outputs are more consistent with the historical record and potentially more realistic in the spatial domains of interest. Utilizing observationally derived datasets also provides more spatial detail44. This improvement over previous GCM-based assessments has been used to evaluate the characteristics of climate extremes45,46.

The NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset includes both historical simulations (1950–2014) and future projections (2015–2100), based on four scenario combinations of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) and Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs). In this study, we define 1985–2014 as the baseline period to provide a 30-year climatological reference and define 2015–2100 as the future projection period, focusing on SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP3-7.0 scenarios. This definition aligns with the CMIP6 scenario design, which provides internally consistent trajectories of socioeconomic drivers and emissions for assessing long-term climate risks. Specifically, the scenarios characterize, respectively, an optimistic pathway with strict climate mitigation measures and air pollution controls, aligning with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 2.0 °C (SSP1-2.6), an intermediate pathway that continues current trends in greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution control level (SSP2-4.5), a high-warming pathway with limited mitigation of climate warming and distinctive weak air pollution controls resulting in high aerosol emissions (SSP3-7.0)35. To facilitate the reporting and comparison of results, two future periods are defined: the mid-21st century (2031–2060) and the late-21st century (2071–2100).

Surface Downwelling Shortwave Radiation (rsds), Daily Maximum Near-Surface Air Temperature (tasmax), Daily Mean Near-Surface Air Temperature (tas), Daily Minimum Near-Surface Air Temperature (tasmin), and Daily Mean Near-Surface Wind Speed (sfcWind) were used to calculate PV power production. Tas and sfcWind were used to calculate wind power production. To address similarity issues within the results from the same institutions in the multi-model mean projection process, only one model was retained for each institution8, provided that all required variables and scenarios were available. Since the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset provides daily climate projections only over land, native-resolution outputs from CMIP6 ESMs/GCMs were employed for offshore regions. Models available for both were retained to ensure consistency in model selection between onshore and offshore regions. Overall, we used 17 GCMs/ESMs for solar PV power, and 14 GCMs/ESMs for wind power. The specific models used in this study are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), measured as the ratio of multi-model mean change to inter-model standard deviation, was used to assess robustness. SNR > 1 was considered a robust change relative to inter-model uncertainty47.

Calculation of PV power production

Our estimates of solar PV power production are based on the PVLIB model developed by Sandia National Laboratories48, which simulates the total power output from a solar PV system at a given time and location. Using surface downwelling shortwave radiation data and the given inclination and azimuth of PV panels, the effective irradiance received by the PV panel is first calculated. Then, the effective irradiance is converted to direct current power using the California Energy Commission (CEC) module performance model, which also takes the input of temperature and wind speed data to consider the PV cell efficiency.

Considering that the estimation of sun-related parameters depends on specific times of day, we disaggregate daily solar radiation and temperature data into hourly values. For solar radiation, we apply the Global Solar Radiation on Horizontal Surface (GSRHS) model49, which builds upon extraterrestrial radiation and incorporates an empirical correction function to improve the hourly distribution. Further details on the disaggregation method and its validation can be found in Supplementary Note 2, and Supplementary Figs. 2–4. Hourly temperature is reconstructed from daily mean, minimum, and maximum temperatures using Erbs’s model50,51.

For tilt, we use a third-order polynomial fitting dependent on latitude52, which has relatively high accuracy but lower computational cost. For azimuth, we adopted a south/north-facing configuration in the Northern/Southern Hemisphere9,53. To estimate the effective irradiance on a panel at a particular tilt angle, we calculate the diffuse fraction using the Boland-Ridley-Lauret (BRL) model54 to distinguish between direct horizontal and diffuse radiation from surface downwelling solar radiation. The BRL model is a multivariate logistic model that takes into account the clearness index, solar elevation, persistence index, and apparent solar time. The parameters are estimated by Lauret et al.55 using a Bayesian parameter estimation method based on nine sites with different environmental conditions in Europe, Africa, Australia, and Asia. Compared to other local modes, the BRL mode is more suitable for global applications.

The “Jinko Solar JKM410M-72HL-V” monocrystalline silicon PV module from the CEC database is used to convert the effective irradiance. Utilizing the test module area, all results are consistently converted into PV power generation per unit area.

Calculation of wind power production

To estimate wind power generation from daily mean wind speed, we reconstructed sub-daily variability assuming that instantaneous wind speeds at hub height follow a two-parameter Weibull distribution as defined in Eq. (1), with a fixed shape parameter (k = 2) and the scale parameter (λ) determined from the daily mean wind speed as described in Eq. (2). This approach provides a physically reasonable and widely validated means to approximate the intraday variability required for wind power generation8,27,56.

where \(f\left(U\right)\) is the probability density function, and \(U\) is the instantaneous wind speed at the hub height.

where \(\overline{U}\) is the daily mean wind speed at the hub height, and \(\varGamma ()\) is the gamma function.

Then, the daily mean power output (\(\bar{P}\)) is calculated by integrating the product of the turbine power curve and the Weibull probability density function over the operational wind speed range:

where \({U}_{\rho }\) is the air density–adjusted wind speed that is calculated as Eq. (4). \(P\left({U}_{\rho }\right)\) represents the turbine power curve obtained from manufacturer data, and interpolation is applied to obtain power output at continuous wind speeds. We apply this method to two representative utility-scale wind turbines: the Vestas V112-3.075 MW onshore turbine57 and the Vestas V164-9.5 MW offshore turbine58.

where \({\rho }_{0}\) is the standard air density (1.225 kg m−3), and \(\rho\) is the air density at the hub height derived from the ideal gas law59,60:

where \(T\) is the air temperature at the hub height, \({R}_{d}\) is the specific gas constant of dry air, and \(p\) is the pressure at the hub height estimated as a function of elevation (\(h\)):

where \({p}_{0}\) is the standard atmospheric pressure at sea level; \(M\) is the molar mass of dry air; \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration; and \(R\) is the universal gas constant. The temperature at hub height (\(z\)) is adjusted from near-surface air temperature (\({T}_{{surface}}\)) using a linear gradient60:

The wind speed at hub height is estimated from the 10 m wind speed using the power law61:

where U(z) is the wind speed at the hub height \(z\); the \(U(10)\) is the wind speed at the 10 m height; and the exponent \(a\) is an empirically derived coefficient that varies depending on the surface roughness, terrain type, and the stability of the atmosphere27. Considering the spatial variability, we derive α at each grid point based on ERA5 reanalysis wind speed data at 10 m and 100 m heights62,63. The estimated α values mainly range from 0.12 to 0.29, with higher values occurring in mountainous or heterogeneous regions, while lower values (0.12–0.16) are found in oceans and smoother terrains (Supplementary Fig. 25). Given the large spatial and seasonal differences but small annual variations, we use the multi-year seasonal means for each grid cell to represent spatial heterogeneity.

Definition and analysis of extreme low-production events

We identify ELP events using a percentile-based thresholding method. For each geographical grid, we first compute daily power production anomalies over the historical baseline period, which is defined as the deviation from the multi-year mean of each calendar day. To ensure sufficient sampling while reducing seasonal biases, the 10th percentile is calculated within a 15-day rolling window centered on each calendar day, aggregating all corresponding days across the 30-year baseline period29,64,65. The choice of window length reflects a trade-off between sampling size and seasonal bias. Shorter windows provide better seasonal alignment but suffer from limited sample size, while longer windows improve statistical robustness but may incorporate seasonal gradients66. Our sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplement Figs. 7–10) shows that a 15-day window, combined with the removal of the mean seasonal cycle in regions with strong seasonality, achieves a good balance between these factors. Specifically, we remove the mean seasonal cycle—globally for solar PV due to its strong seasonality, and only over the Somali Peninsula for wind power. To avoid artificial discontinuities and ensure comparability across baseline and future periods, we estimate thresholds using a cross-validation approach for the baseline period (see ref. 67. for details).

A day is classified as an ELP day if its production falls below the corresponding percentile threshold. Consecutive ELP days are grouped into a single ELP event. For each event, we record its duration, intensity, and cumulative anomaly (i.e., the sum of deviations from the climatological mean). Intensity is defined as the ratio of the cumulative anomaly to the corresponding cumulative climatological mean over the event duration, reflecting the relative severity of power shortfalls compared to the expected generation. At the annual scale, we further report the frequency of ELP events and the total power production anomaly during ELP events. This provides a direct measure of the risk of power supply shortfalls attributable to ELP events and enables consistent comparison of climate-induced risks to power supply reliability across periods and regions.

Distinguishing installed and potentially exploitable areas

Installed areas are defined as 0.25° grid cells that contain power-generating units. Solar PV facilities were obtained from the TZ-SAM dataset (Q4 2024)68, which identifies utility-scale assets across 190 countries using satellite imagery, combining machine learning and manual validation. The dataset covers a total estimated capacity of 922 GW. For wind power, we used wind-farm-level data from The Wind Power database (accessed March 2025)69, which provides global coverage of both onshore and offshore projects, with large farms subdivided into multiple sub-sites where applicable. Our analysis includes both operational and under-construction wind farms across 132 countries, with a total installed capacity of 1136 GW—comprising 1038 GW onshore and 98 GW offshore facilities.

To identify potentially exploitable areas, we considered several constraints and excluded regions already hosting installations. The stringency of the imposed constraints varied widely across different studies70,71,72,73. Here, we used a relaxed constraint to include more possible areas in the assessment. Specifically, areas were excluded if they matched any of the following conditions: nature reserves, forests, water bodies, areas within a 150 m buffer of roads and railways, and slopes greater than 30°. Urban areas were further excluded from wind-exploitable areas. The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) was used to identify the distribution of nature reserves74. The spatial location of forests, water bodies, and urban areas was identified based on the 2022 MODIS Land Cover Type Product (MCD12Q1) dataset at 500 m spatial resolution75. Land Cover Type 2, i.e., University of Maryland classification, was used in this study. Railway and road data were obtained from the OSM database76. Slope angle was developed from a global elevation model called the Global Multi-resolution Terrain Elevation Data (GMTED2010) at 500 m spatial resolution, developed by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA)77. We initially performed all filters at 500 m spatial resolution and then calculated the proportion of non-exploitable elements at a spatial resolution of 0.25°. Areas were considered exploitable if the proportion was less than 50%.

Administrative and subregional boundaries

We used the geographic boundaries obtained from the World Bank as the national and subregional boundaries78, which exclusively define boundaries on global land extent. To define national marine boundaries, we used geographic data obtained from Flanders Marine Institute79, which provides a standard map coupled with a territory list. Offshore areas within 200 km of the coast were considered. Country income groupings follow the standard World Bank definitions80.

Data availability

All data supporting the study have been sourced from freely and publicly available sources, which are cited within the main text or Supplementary Information. Source data underlying figures is provided on Zenodo81.

Code availability

The PVLIB code is available at https://github.com/pvlib. The code used to produce the results in this study is available at https://github.com/Vapson/ci_pv_wind-main.git82.

References

Davis, S. J. et al. Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science 360, eaas9793 (2018).

Bistline, J. E. Roadmaps to net-zero emissions systems: emerging insights and modeling challenges. Joule 5, 2551–2563 (2021).

IEA. World Energy outlook (2021).

Patt, A., Pfenninger, S. & Lilliestam, J. Vulnerability of solar energy infrastructure and output to climate change. Clim. Change 121, 93–102 (2013).

van der Wiel, K. et al. Meteorological conditions leading to extreme low variable renewable energy production and extreme high energy shortfall. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 111, 261–275 (2019).

Anvari, M. et al. Short term fluctuations of wind and solar power systems. New J. Phys. 18, 063027 (2016).

Morris, C. Germany’s worse-cases scenario in the power sector. Energy Transit. Glob. Energiewende (2017).

Liu, L. et al. Climate change impacts on planned supply–demand match in global wind and solar energy systems. Nat. Energy 8, 870–880 (2023).

Tong, D. et al. Geophysical constraints on the reliability of solar and wind power worldwide. Nat. Commun. 12, 6146 (2021).

Perera, A. et al. Quantifying the impacts of climate change and extreme climate events on energy systems. Nat. Energy 5, 150–159 (2020).

Dowling, J. A. et al. Role of long-duration energy storage in variable renewable electricity systems. Joule 4, 1907–1928 (2020).

What Europe’s exceptionally low winds mean for the future energy grid. https://theconversation.com/what-europes-exceptionally-low-winds-mean-for-the-future-energy-grid-170135 (2021).

Jackson, N. D. & Gunda, T. Evaluation of extreme weather impacts on utility-scale photovoltaic plant performance in the United States. Appl. Energy 302, 117508 (2021).

Hao, Z. et al. The 2022 Sichuan-Chongqing spatio-temporally compound extremes: a bitter taste of novel hazards. Sci. Bull. 68, 1337–1339 (2023).

Ibrahim, N. A. et al. Impact of extreme temperature on solar power plant in Malaysia. Chemical Engineering Transactions 94, 343–348 (2022).

Baras, A. et al. Opportunities and challenges of solar energy in Saudi Arabia. World Renew. Energy Forum 1, 4721 (2012).

Li, X., Mauzerall, D. L. & Bergin, M. H. Global reduction of solar power generation efficiency due to aerosols and panel soiling. Nat. Sustain. 3, 720–727 (2020).

Gutiérrez, C. et al. Future evolution of surface solar radiation and photovoltaic potential in Europe: investigating the role of aerosols. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 034035 (2020).

Gandoman, F. H. et al. Short-term solar power forecasting considering cloud coverage and ambient temperature variation effects. Renew. Energy 123, 793–805 (2018).

Raza, M. Q., Nadarajah, M. & Ekanayake, C. On recent advances in PV output power forecast. Sol. Energy 136, 125–144 (2016).

Ho-Tran, L. & Fiedler, S. A climatology of weather-driven anomalies in European photovoltaic and wind power production. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 63 (2024).

Yin, J., Molini, A. & Porporato, A. Impacts of solar intermittency on future photovoltaic reliability. Nat. Commun. 11, 4781 (2020).

Dutta, R., Chanda, K. & Maity, R. Future of solar energy potential in a changing climate across the world: A CMIP6 multi-model ensemble analysis. Renew. Energy 188, 819–829 (2022).

Hou, X. et al. Climate change impacts on solar power generation and its spatial variability in Europe based on CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 1099–1113 (2021).

Lei, Y. et al. Co-benefits of carbon neutrality in enhancing and stabilizing solar and wind energy. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 693–700 (2023).

Gernaat, D. E. et al. Climate change impacts on renewable energy supply. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 119–125 (2021).

Pryor, S. C. et al. Climate change impacts on wind power generation. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1, 627–643 (2020).

Zheng, D. et al. Climate change impacts on the extreme power shortage events of wind-solar supply systems worldwide during 1980–2022. Nat. Commun. 15, 5225 (2024).

Feron, S., Cordero, R. R., Damiani, A. & Jackson, R. B. Climate change extremes and photovoltaic power output. Nat. Sustain. 4, 270–276 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Climate change impacts on global photovoltaic variability. Appl. Energy 374, 124087 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Photovoltaic installations are extensively deployed in areas at risk of extremely low production. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–8 (2024).

Bennett, J. A. et al. Extending energy system modelling to include extreme weather risks and application to hurricane events in Puerto Rico. Nat. Energy 6, 240–249 (2021).

Davidson, M. R. et al. Modelling the potential for wind energy integration on China’s coal-heavy electricity grid. Nat. Energy 1, 1–7 (2016).

Turner, S. W. et al. Compound climate events transform electrical power shortfall risk in the Pacific Northwest. Nat. Commun. 10, 8 (2019).

IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021).

Shiogama, H. et al. Important distinctiveness of SSP3–7.0 for use in impact assessments. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1276–1278 (2023).

Deng, K. et al. Global near-surface wind speed changes over the last decades revealed by reanalyses and CMIP6 model simulations. J. Clim. 34, 2219–2234 (2021).

Niu, J. et al. Climate change impact on photovoltaic power potential in China based on CMIP6 models. Sci. Total Environ. 858, 159776 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Improved air quality in China can enhance solar-power performance and accelerate carbon-neutrality targets. One Earth 5, 550–562 (2022).

Rao, S. et al. Future air pollution in the Shared Socio-economic Pathways. Global Environ. Change 42, 346–358 (2017).

Larsen, M. A. D. et al. Renewable energy planning in Africa: robustness of mean and extreme multi-model climate change patterns in solar PV and wind energy potentials. Environ. Res. Commun. 6, 015001 (2024).

Thrasher, B. et al. NASA global daily downscaled projections, CMIP6. Sci. Data 9, 262 (2022).

Thrasher, B., Wang, W., Michaelis, A., Nemani, R. NEX-GDDP-CMIP6. NASA Center for Climate Simulation. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01393-4 (2021).

Thrasher, B., Maurer, E. P., McKellar, C. & Duffy, P. B. Bias correcting climate model simulated daily temperature extremes with quantile mapping. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 16, 3309–3314 (2012).

He, T. et al. Anthropogenic activities change population heat exposure much more than natural factors and land use change: An analysis of 2020-2100 under SSP-RCP scenarios in Chinese cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 96, 104699 (2023).

Murali, G., Iwamura, T., Meiri, S. & Roll, U. Future temperature extremes threaten land vertebrates. Nature 615, 461–467 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Reduced exposure to extreme precipitation from 0.5 °C less warming in global land monsoon regions. Nat. Commun. 9, 3153 (2018).

Holmgren, W. F., Hansen, C. W. & Mikofski, M. A. pvlib python: A python package for modeling solar energy systems. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 884 (2018).

Pandey, P. K. & Soupir, M. L. A new method to estimate average hourly global solar radiation on the horizontal surface. Atmos. Res. 114, 83–90 (2012).

Bilbao, J., De Miguel, A. H. & Kambezidis, H. D. Air temperature model evaluation in the north Mediterranean belt area. J. Appl. Meteorol. 41, 872–884 (2002).

Erbs, D. G. Models and applications for weather statistics related to building heating and cooling loads. Solar Energy Laboratory, University of Wisconsin-Madison (1985).

Jacobson, M. Z. & Jadhav, V. World estimates of PV optimal tilt angles and ratios of sunlight incident upon tilted and tracked PV panels relative to horizontal panels. Sol. Energy 169, 55–66 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. Optimizing wind/solar combinations at finer scales to mitigate renewable energy variability in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 132, 110151 (2020).

Ridley, B., Boland, J. & Lauret, P. Modelling of diffuse solar fraction with multiple predictors. Renew. Energy 35, 478–483 (2010).

Lauret, P., Boland, J. & Ridley, B. Bayesian statistical analysis applied to solar radiation modelling. Renew. Energy 49, 124–127 (2013).

Pryor, S., Nielsen, M., Barthelmie, R. & Mann, J. Can satellite sampling of offshore wind speeds realistically represent wind speed distributions? Part II: Quantifying uncertainties associated with distribution fitting methods. J. Appl. Meteorol. 43, 739–750 (2004). Climatol.

Vestas V112-3.075 MW onshore turbine. https://www.thewindpower.net/turbine_en_1076_vestas_v112-3075.php (2024).

Vestas V164-9.5 MW offshore turbine. https://www.thewindpower.net/turbine_en_1476_vestas_v164-9500.php (2024).

Ahrendts, J., Kabelac, S. Das Ingenieurwissen: Technische Thermodynamik. (Springer, 2014).

Haas, S. et al. wind-python/windpowerlib: Silent Improvements. Zenodo, https://github.com/wind-python/windpowerlib/tree/v0.2.1 (2021).

Irwin, J. S. A theoretical variation of the wind profile power-law exponent as a function of surface roughness and stability. Atmos. Environ. 13, 191–194 (1979).

Copernicus Climate Change Service, Climate Data Store. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47 (2023).

Jung, C. & Schindler, D. The role of the power law exponent in wind energy assessment: A global analysis. Int. J. Energy Res. 45, 8484–8496 (2021).

Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. & Lewis, S. Increasing trends in regional heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 11, 3357 (2020).

Cowan, T. et al. More frequent, longer, and hotter heat waves for Australia in the twenty-first century. J. Clim. 27, 5851–5871 (2014).

Brunner, L. & Voigt, A. Pitfalls in diagnosing temperature extremes. Nat. Commun. 15, 2087 (2024).

Zhang, X., Hegerl, G., Zwiers, F. W. & Kenyon, J. Avoiding inhomogeneity in percentile-based indices of temperature extremes. J. Clim. 18, 1641–1651 (2005).

TransitionZero. TZ-SAM. https://www.transitionzero.org/products/solar-asset-mapper (2024).

The Wind Power. Worldwide wind farms. https://www.thewindpower.net/windfarms_list_en.php (2024).

Lopez, A. et al. Impact of siting ordinances on land availability for wind and solar development. Nat. Energy 8, 1034–1043 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. Potential contributions of wind and solar power to China’s carbon neutrality. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 180, 106155 (2022).

McElroy, M. B., Lu, X., Nielsen, C. P. & Wang, Y. Potential for wind-generated electricity in China. Science 325, 1378–1380 (2009).

Lu, X. et al. Combined solar power and storage as cost-competitive and grid-compatible supply for China’s future carbon-neutral electricity system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2103471118 (2021).

UNEP-WCMC, IUCN. Protected planet: the world database on protected areas (WDPA). www.protectedplanet.net. (2023).

Friedl, M., Sulla-Menashe, D. MODIS/Terra+ Aqua land cover type yearly L3 global 500 m SIN grid V061. https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD12Q1.061 (2022).

OpenStreetMap contributors. Geofabrik dump. https://download.geofabrik.de/ (2023).

Danielson, J. J., Gesch, D. B. Global multi-resolution terrain elevation data 2010 (GMTED2010). https://topotools.cr.usgs.gov/gmted_viewer/gmted2010_global_grids.php (2011).

World Bank. World Bank Official Boundaries. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0038272/World-Bank-Official-Boundaries (2023).

Flanders Marine Institute. Maritime Boundaries Geodatabase, version 11. https://www.marineregions.org/ (2019).

World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (2022).

Wang, Q. Rising worldwide challenges to climate-induced extreme low-production events of photovoltaic and wind power (2025.11.19). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17652401 (2025).

Wang, Q. Rising worldwide challenges to climate-induced extreme low-production events of photovoltaic and wind power (2025.11.19). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17652144 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFC3808601, K.L.), General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42377467, K.L.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2243300007, K.L.). Climate scenarios used were from the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset, prepared by the Climate Analytics Group and NASA Ames Research Center using the NASA Earth Exchange and distributed by the NASA Center for Climate Simulation (NCCS). We acknowledge the World Climate Research Program, which, through its Working Group on Coupled Modeling, coordinated and promoted CMIP6. We thank the climate modeling groups for producing and making available their model output, the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) for archiving the data and providing access, and the multiple funding agencies that support CMIP6 and ESGF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L. and Q.W. developed the original idea and designed the study. Q.W. performed the data processing. K.L., Q.W., and Z.Z. conducted the analysis. Q.W., K.L., M.W., J.W., and H.Z. contributed to scientific interpretations of the results. Q.W. wrote the original manuscript. K.L., M.W., Z.Z., H.C., L.L., and H.Z. worked on the review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Luo Xu, N. Girgibo and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Liu, K., Wang, M. et al. Rising worldwide challenges to climate-induced extreme low-production events of photovoltaic and wind power. Nat Commun 17, 734 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67428-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67428-7