Abstract

Ultrafast radiation detection is crucial for advancing medical imaging, high-energy physics, astronomy, and industrial applications, offering high spatiotemporal resolution and reduced radiation exposure. However, the bottleneck lies in the formidable challenge of achieving scintillators with both ultrafast response and high efficiency. Contrasting with previous approaches that focused on molecular-level confinement, here we propose the strategy of pushing exciton confinement to the limit of atomic scale. Using 2D perovskites as a model, we design organic A-site cations to selectively enhance in-plane distortion to localize excitons, while suppressing out-of-plane and intra-octahedral distortions to minimize the formation of inefficient, long-lived self-trapped excitons. Specifically, (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 exhibits a rare combination of fast response (0.62 ns) and high light yield (19,700 photons MeV−1), surpassing leading commercial and research scintillators. These properties enable breakthroughs in advanced imaging, including fast positron emission tomography with timing precision of 43.3 ps and high-resolution X-ray imaging (32 lp mm−1).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scintillators, as a fundamental technology, are widely applied in medicine, high-energy physics, astronomy, and industry, where fast response and high efficiency are universally pursued goals1,2,3. Ideal scintillators with these properties enable high spatiotemporal resolution while minimizing radiation doses for medical X-ray computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, as well as aid in registering intense events for vertex localization in high-energy physics, astronomy, and nuclear reaction4,5. Nevertheless, achieving scintillators with both ultrafast response and high efficiency remains a formidable challenge6,7. According to Fermi’s Golden Rule, response speed is proportional to the transition moment between initial and final states, whereas efficiency corresponds to the density of emission states8,9. Conventional inorganic scintillators (e.g., LaBr3: Ce, LYSO: Ce) exhibit long response times on the order of tens of nanoseconds due to the limited dipole moment of rare earth d-f transitions7,10,11. While core-valence and intra-band luminescence (e.g., BaF2) can enhance transition matrix and achieve sub-nanosecond response, charge migration within bands seriously reduces the density of emission states, leading to poor efficiencies ( < 3000 photons MeV−1)12.

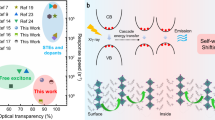

Exciton-based scintillators have emerged as promising alternatives13. Stronger exciton confinement enhances both the transition dipole moment and the emission state density, offering the potential for both ultrafast response and high efficiency. As a result, materials like nanocrystals14,15,16, organic materials17,18,19,20,21, and 2D perovskites22,23 have achieved response speeds below 10 ns. However, the sub-nanosecond barrier has rarely been broken. The fundamental limitation lies in the insufficient degree of exciton confinement in current schemes, which only allow for molecular-level confinement, typically involving hundreds to thousands of atoms (Fig. 1a). For example, nanocrystals comprise >1000 atoms, while organic molecules contain >100 atoms. In 2D perovskites, although excitons are confined in the out-of-plane direction within a single lattice (three atoms), they still extend across tens or more atoms in the in-plane direction, resulting in either unsatisfactory light yield or slow response speed.

a Schematic of exciton confinement in various scintillators and the corresponding response time range. b Design concept of atomic-level exciton confinement in 2D perovskites by regulated in-plane tilting. c The summary of light yield and radioluminescence lifetime of commercial, state-of-the-art scintillators and our atomic-level confined excitonic 2D perovskite.

To overcome this dilemma, we propose the strategy of pushing exciton confinement to the limit of atomic scale. Using 2D perovskites as a model system, we apply in-plane lattice distortion along with out-of-plane dielectric screening to achieve atomic-level exciton confinement (Fig. 1b). The key lies in the synergistic regulation of steric hindrance and polarity of organic A-site cations to selectively enhance in-plane distortion while suppressing out-of-plane and intra-octahedral distortions. The latter two distortions, if not properly controlled, can lead to inefficient, long-lived self-trapped exciton (STE) states (Supplementary Fig. 1)24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31.

Following these rules, we design a series of 2D perovskites with tailored A-site cations, including cyclohexanemethylamine (CMA), 4-aminomethyl-1-cyclohexanecarboxylate (CMA-COOH), and cyclohexane-1,4-diyldimethanamine (1,4-CMA) (Supplementary Fig. 2). All three compounds fall into the rare category of high light yield and fast response (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Table 1). Among them, (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 achieves a remarkable level of exciton confinement by combining strong in-plane tilting with intense out-of-plane dielectric confinement. This effective confinement in all dimensions endows (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 with a rare combination of sub-nanosecond radioluminescence lifetime (0.62 ns) and high light yield (19,700 photons MeV−1). These properties enable breakthroughs in advanced imaging applications. We demonstrate PET detection with a coincidence timing resolution (CTR) of 43.3 ps, allowing for reconstruction-free PET imaging with significantly reduced radiation dose and acquisition time. Additionally, its fast response ensures minimal afterglow, enabling dynamic X-ray imaging with high resolution (32 lp mm−1).

Results

Structural distortions influenced by A-site cations

First, we investigate the exciton confinement behavior in 2D perovskites. While their layered structure inherently isolates adjacent layers and the low dielectric constant of A-site cations ensures well-established out-of-plane quantum and dielectric confinement, the in-plane exciton behavior and the influence of lattice distortions remains less understood.

Structural distortions in 2D perovskites primarily fall into three categories: intra-octahedral distortions, where Pb2+ deviates from the octahedral center, altering the Br-Pb-Br bond angles; out-of-plane octahedral tilting, which changes the Pb-Br-Pb bond angles along the stacking direction; and in-plane octahedral tilting, which affects Pb-Br-Pb bond angles within the inorganic plane (Fig. 2a). By analyzing our synthesized 2D perovskite materials alongside previously reported results, we identify a common trend—both intra-octahedral distortions and out-of-plane tilting tend to induce STE states, leading to slow and inefficient emission (Supplementary Fig. 3). Consequently, in-plane tilting emerges as a rare but effective strategy to achieve exciton confinement without triggering STE formation.

a Schematic of in-plane tilting (Din), out-of-plane tilting (Dout) and intra-octahedral distortion (θ2). b The influence of A-site cations on intra-octahedral distortion. c The influence of A-site cations on out-of-plane tilting. d The influence of A-site cations on in-plane tilting. Red balls represent Pb atoms, blue balls represent Br atoms, hollow ball represents the electropositive region of organic cations, and purple ball represents the electronegative region.

We further examine the structural origins of these three types of distortions and their correlation with A-site molecular properties (Fig. 2b–d). The intra-octahedral distortion is influenced by the symmetric environment created by the nearest eight A-site cations, which exert electrostatic attraction and repulsion on the central Pb2+32 In a highly symmetric arrangement, Pb2+ remains at the octahedral center, whereas asymmetric polarization induces its displacement (Fig. 2b). Thus, intra-octahedral distortion value (θ2) is primarily affected by the C-N symmetry of the nearest A-site molecules, as well as the spatial arrangement of their outer carbon skeletons. For example, in [S-N]2PbBr4 (S-N represents S-( − )−1-(1-naphthyl)ethylammonium), the highly asymmetric C-N configuration induces significant polarity, resulting in pronounced intra-octahedral distortion (Supplementary Fig. 4)33. Meanwhile, out-of-plane tilting (Dout) is more significantly affected by the centrosymmetry of the four organic molecules in the adjacent upper and lower layers (Fig. 2c). In (1,3-PDA)PbBr4 (1,3-PDA represents 1,3-phenylenediammonium), the asymmetric arrangement of both the C-N ends and phenylamine across the upper and lower octahedral layers leads to substantial out-of-plane distortion (Supplementary Fig. 5)34. On the other hand, the steric hindrance of the functional ammonium group, which fits in the gap between Pb-Br octahedra, determines the in-plane tilting (Fig. 2d). Smaller functional groups induce more contraction and in-plane tilting (Supplementary Fig. 6)35,36.

Based on these findings, we identify key design principles for ideal A-site cations: 1) Strong symmetry in both the C-N configuration and the outer molecular skeleton to minimize intra-octahedral distortions. 2) Centrosymmetric arrangement across layers, eliminating polarity-driven out-of-plane tilting. 3) Small functional ammonium groups to facilitate in-plane tilting.

Structure-property relationship

To implement these principles, we design non-conjugated molecular additives (CMA) and their derivatives as A-site cations to create a highly symmetric environment (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 7). Unlike previously reported materials, three compounds—(CMA)2PbBr4, (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4 and (1,4-CMA)PbBr4—exhibit pronounced in-plane tilting while maintaining minimal intra-octahedral and out-of-plane distortions ( < 2°) (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Tables 2–6). Their photoluminescence spectra feature remarkably narrow emission peaks (FWHM of ~30 nm), and temperature-dependent measurements reveal minimal linewidth broadening, providing strong evidence against STE formation (Fig. 3c). To further validate our design rationale, we introduce an asymmetric A-site cation, 1,3-CMA, as a control to induce an asymmetric polarization environment around Pb-Br octahedron. As expected, (1,3-CMA)PbBr4 exhibits significant out-of-plane tilting and intra-octahedral distortion, accompanied by a broad STE emission peak (Inset of Fig. 3c).

a Crystal structures of (1,4-CMA)PbBr4, (CMA)2PbBr4, (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4 and (1,3-CMA)PbBr4. b The summary of in-plane tilting (Din) and out-of-plane tilting (Dout) of representative 2D perovskites. c Temperature-dependent full width at half maximum (FWHM) of PL spectra for the synthesized 2D perovskites. The inset is the PL spectra at room temperature. d The exciton diffusion dynamics of BM2PbBr4, (CMA)2PbBr4 and (1,4-CMA)PbBr4. The inset shows the transient photoluminescence mapping of the (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 single crystal. D represents carrier diffusion coefficient. e Electrostatic potential (φmax) of the representative amines in 2D perovskites. f Temperature-dependent intensity of PL spectra and the fitted excitonic binding energy (Eb). The inset is the temperature-dependent PL spectra for (1,4-CMA)PbBr4.

We then quantify exciton diffusion dynamics by performing transient photoluminescence microscopy (TPLM) on single crystals (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 8-9 and Supplementary Note I). The diffusion constant D is determined by D = (σt2 − σ02)/4t, where σt2 represents the time-dependent variance of the exciton population, and σ02 corresponds to the initial variance. The diffusion coefficient of (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 is 0.0238 cm2 s−1, significantly smaller than BM2PbBr4 (0.0925 cm2 s−1), indicating much stronger in-plane exciton confinement than BM2PbBr4. The serious in-plane exciton diffusion of BM2PbBr4 also explains its relatively low light yield ( ~ 3,000 photons MeV−1)23.

We also calculate the electrostatic potentials of the organic amine molecules (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 10). 1,4-CMA exhibits the lowest electrostatic potential, which enables stronger out-of-plane dielectric confinement37,38. Consequently, the exciton binding energy (Eb) of (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 reaches 363.4 meV, slightly higher than (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4 (305.9 meV) and CMA2PbBr4 (265.4 meV) (Fig. 3f), and much higher than previously reported 2D perovskites, including PEA2PbBr4 (190 meV) and BA2PbBr4 (260 meV)23,39.

We further evaluate the photoluminescence performance through fluence-dependent photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) measurements, which reveal that all samples exhibit a characteristic rise-to-roll-off trend (Supplementary Fig. 11). The initial rise suggests efficient filling of non-radiative trap states at lower excitation densities. The subsequent universal roll-off is attributed to intensified exciton-exciton interactions at high exciton densities, where the decreased average distance between excitons significantly raises the probability of synergistic energy loss through multiple recombination pathways31.

Scintillation performance

We then characterize the radioluminescence (RL) properties. During the scintillation process under X/γ-ray excitation, primary high-energy electrons are initially generated and rapidly thermalize (on the picosecond to femtosecond timescale) to form band-edge excitons. The response speed of scintillators is determined by the slow recombination process of these excitons near band edges (Fig. 4a). The atomic-level confined exciton in these 2D perovskite enable efficient and fast recombination. To verify their radioluminescence properties, we grow high-quality, large single crystals of (CMA)2PbBr4, (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4, (1,4-CMA)PbBr4, and (1,3-CMA)PbBr4 using the slow cooling solution method according to their respective solubility curves (Supplementary Fig. 12). The basic properties, including optical images, absorption spectra and band structures, are shown in Supplementary Figs. 13–15.

a Schematic of exciton recombination processes under X/γ-ray excitation. b Normalized radioluminescence spectra of 2D perovskites. c Pulse height spectra of BGO, LYSO:Ce, (CMA)2PbBr4, (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4 and (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 under 241Am (59.5 keV) excitation. d PL decay. e RL decay. f Radiation stability of (1,4-CMA)PbBr4.

As presented in Fig. 4b, the RL spectra of these single crystals are measured using an integrating sphere, with the well-studied PEA2PbBr4 single crystal of the same size and thickness serving as a reference. The RL spectra closely resemble their corresponding PL spectra excited by ultraviolet light (inset of Fig. 3c), indicating the same radiative recombination pathway. (CMA)2PbBr4, (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4, and (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 all exhibit narrowband RL emission while (1,3-CMA)PbBr4 displays broadband STE emission. The scintillation light yields of (CMA)2PbBr4, (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4, and (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 are evaluated relative to a LYSO:Ce reference (32,000 photons MeV−1) using standard pulse-height analysis. In this setup, the crystals are optically coupled to a photomultiplier tube (PMT), and the signals excited by 241Am (59.5 keV) are recorded on an oscilloscope. The acquired spectra are presented in Fig. 4c. We calculate the yield based on the channel number of the full-energy peak centroid, incorporating a correction for the PMT’s wavelength-dependent efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 16). The full energy peak centroids for the three crystals are located at the channel number 68.52, 28.99, and 27.99, which are 1.47, 0.62, and 0.60 times that of the LYSO:Ce standard, respectively. Thus, the scintillation yields of (CMA)2PbBr4, (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4, and (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 are estimated to be 50,460, 20,460, and 19,730 photons MeV−1, respectively.

Furthermore, we record the PL and RL decay dynamics of these scintillators using a pulsed 367 nm laser and a pulsed X-ray source, respectively. The average lifetime of (CMA)2PbBr4 (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4 and (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 under laser excitation was 5.23 ns, 0.98 ns and 0.46 ns, respectively (Fig. 4d). However, the RL decay was slightly slower than PL decay (Fig. 4e), primarily because X-rays excites high-energy electrons, which are more likely to escape from their exciton-bound states, leading to longer lifetimes. This difference is further accentuated by enhanced non-radiative recombination at the surface under PL excitation—a contrast to the bulk-dominated carrier generation and comparatively lower defect-mediated recombination in RL. This also implies that, due to the energy being 3-5 orders of magnitude higher, achieving fast RL is much more challenging than for materials like phosphors or OLEDs, making exciton confinement even more crucial. For a more rigorous comparison, we adopt RL decay time. We find that (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 achieves an average scintillation lifetime of 0.62 ns, while (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4 and (CMA)2PbBr4 exhibit average lifetimes of 1.09 ns and 8.4 ns, respectively. The fast and slow component of RL decay for (CMA)2PbBr4 is 4.37 ns and 9.61 ns, while for (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4, they are 0.61 and 2.13 ns, respectively. Notably, the fast and slow component of RL decay for (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 reach as short as 0.25 and 1.16 ns, respectively (Supplementary Table 7). In comparison, BaF240—one of the fastest commercial scintillators—exhibit the fast component of 0.6 ns, lagging behind (1,4-CMA)PbBr4, underscoring the advantage of our materials.

We also assess the stability of the fastest scintillator (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 toward moisture and continuous radiation (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 17). No detectable weight loss is recorded for the sample following a 35-day period at 70% relative humidity. In terms of radiation stability, the light output is measured while the bare single crystal (without encapsulation) is irradiated with X-rays in an ambient environment (25 °C and 70% relative humidity), as shown in Fig. 4f. After continuous X-ray irradiation (916.09 mGy s−1) and repeated on-off X-ray cycles, accumulating a total dose of 1,099 Gyair, no deterioration in light output was observed. This dose is equivalent to 20,000 times CT scans, demonstrating exceptional radiation hardness. The structural and optical integrity after testing are confirmed by XRD and PL measurements, which show negligible degradation (Supplementary Figs. 18–19). The scintillation kinetics are largely retained post-irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 20), and the variations are consistent with the creation and evolution of point defects41,42, as evidenced by the stable crystal structure (Supplementary Fig. 18).

Applications in fast radiation detection and imaging

Next, we investigate the advantages of the scintillator for time-of-flight PET (TOF-PET) and dynamic X-ray imaging. In TOF-PET, CTR serves as a critical performance parameter, where a lower CTR results in better spatial resolution43. LYSO:Ce,Ca crystals were selected as a benchmark reference due to their rapid timing characteristics and high stopping power (Supplementary Fig. 21). An alternating stack consisting of three naturally grown (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 single crystal layers and four manually cut LYSO:Ce,Ca layers was constructed, with all surfaces polished. The overall dimensions were 3 × 2.8 × 3 mm3 and covered with enhanced specular reflector films, wrapped in Teflon thereafter, except for the light extraction face. This dual-layer coating can effectively reduce light escape from the crystal corners44. The reference and sample crystals are directly coupled to the optical windows of the SiPMs. A pair of detectors detects coincidence signals from two back-to-back 511 keV γ-photons produced by positron annihilation from a 22Na radioactive source. A coincidence event was recorded when two photons trigger both detectors within energy and time difference windows. The signals were selected in a coincidence window of ±1 ns filtered through an energy/voltage filter to isolate those in the photopeak region of the energy spectrum, using the valley between Compton edge and photopeak as the reference point (Fig. 5a). The acquisitions were post-processed using custom Python code to detect features like different CTR voltage thresholds for each voltage bias, analyzing and sanitizing acquired events, as detailed in previous work45.

a Integrated charge spectra for 511 keV photons along with the intervals filtered by different response voltages. b Decay curves collected by the two opposite detectors, and the location (Δx) can be calculated based on the time difference (Δτ) via Δx = Δτc/n. c, the speed of light in a vacuum; n, the refractive index of the medium. c Delay time histograms of LYSO:Ce,Ca against (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 before (orange line) and after (red line) photopeak event selection. d Delay time histograms of (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 before photopeak event selection (blue line) and after photopeak event selection with different filters (orange, black and red lines). The FWHMs are extracted using a Gaussian fit. The inset is the enlarged curve of the red line showing the Coincidence time resolution (CTR) of 43.3 ps. e CTR comparison of state-of-the-art scintillators. f Advantages of the high timing resolution in reconstruction-free PET imaging, and the corresponding spatial precision. g Dynamic X-ray imaging of a moving screw by (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 and commercial CsI:Tl scintillator. The scale bar represents 5 mm. h Modulation transfer function (MTF) curve. i X-ray image of the standard X-ray resolution pattern plate. j High-resolution X-ray images (campus card, chip, bird leg). The bird leg specimen used for X-ray imaging was obtained from a commercial food market; no live animals were used in this experiment. The scale bar represents 1 cm.

The integrated charge spectrum shows clear full energy peaks with an energy resolution of 10.4% at 511 keV (Fig. 5a). To enhance the effective count rate of the system, a laminated configuration consisting of LYSO and perovskite was implemented. By employing a filter (0/1, 130 nV s) to process the coincidence pairs of output pulses and performing overlapping integration, a CTR of 79.6 ± 0.8 ps was achieved for the LYSO/(1,4-CMA)PbBr4 laminated detector (Fig. 5b, c), smaller than the intrinsic CTR of the LYSO detector itself of 83 ± 3 ps. To further obtain the intrinsic CTR of (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 independently, a single-layer perovskite was directly coupled to SiPM surface through optical grease. Remarkably, a record CTR of 43.3 ps of (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 detector was obtained (Fig. 5d). This performance significantly surpasses that of commercial scanners ( ~ 200 ps), previously reported BM2PbBr4 (207 ps), and PEA2PbBr4 (119 ps), and Zr-DPA MOF (85 ps), highlighting the excellent temporal resolution of the (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 (Fig. 5e)22,23,46. The improved timing resolution for TOF-PET implies the ability to diagnose smaller lesions or tumors. When the timing resolution is sufficiently precise to directly localize the source, a new regime is entered, where images can be obtained directly without the need for reconstruction steps. As shown in Fig. 5f, traditional TOF-PET requires image reconstruction to precisely locate the source position. Our detector, leveraging its ultra-short resolution, eliminates the need for reconstruction and directly accomplishes the task with just a pair of detectors. Beyond medical applications, the fast response and high efficiency of these scintillators make them highly promising for astrophysical cosmic ray detection, nuclear monitoring, border control, and high-energy physics experiments, all of which require fast response to mitigate pile-up background and accurately localize event vertexes.

Benefiting from the short decay time, (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 demonstrates a suppressed afterglow. Residual images of a round nut with a camera after 10 sec of X-ray exposure were captured (Supplementary Fig. 22). (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 presents negligible residual images in all frames, whereas the commercial CsI:Tl film shows distinct residual images even after 2 s. As shown in Fig. 5g, a screw was mounted on a slide-traction plate, and the steel plate applied a pulling force to the screw while continuous X-ray irradiation occurred (Supplementary Fig. 23). The image was captured in an interval of 30 ms. As the screw moved, the serrated structure on the outer edge of the screw was clearly visible with no residual shadow.

Furthermore, featuring a high light yield, (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 exhibits a spatial resolution of 32.3 lp mm−1 at a modulation transfer function (MTF) of 0.2, measured by the slanted-edge method (Fig. 5h). This performance outperforms commercial CsI:Tl (3–5 lp mm−1) and GOS:Tb (4–8 lp mm−1), and also exceeds recently reported perovskite (22 lp mm−1) and organic scintillators (18 lp mm−1)13,20,47,48,49. X-ray images of a standard resolution test chart indicate that the line pairs at 30 lp mm−1 remain clearly resolvable (Fig. 5i), validating this high spatial resolution. This exceptional imaging resolution enables the precise identification of ultra-fine internal structures, as demonstrated in a campus card (showing embedded components), an integrated circuit chip (revealing trace distributions), and a bird leg (visualizing bone structure) (Fig. 5j).

Finally, we evaluate the practical performance of (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 by comparing its radiation hardness and X-ray stopping power with commercial BaF2 (Supplementary Fig. 24). While BaF2 exhibits superior radiation resistance and higher stopping power, (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 demonstrates reasonable radiation hardness ( ~2% degradation after 5 kGyair) despite its lower attenuation coefficient.

Discussion

In summary, we elucidate the structure-property relationship between long-chain organic cations, various structural distortions, and the resulting exciton confinement in 2D perovskites. By carefully screening A-site cations with highly symmetric structures and small functional ammonium groups, we develop a series of fast and efficient scintillators with atomic-level exciton confinement.

Our strategy overcomes a fundamental limitation in luminescent materials: the typical correlation between strong exciton localization and STE emission. By precisely engineering the lattice distortions, we achieve in-plane exciton confinement without inducing the strong electron-phonon interaction that dictates STE formation. Importantly, the in-plane tilting in our system is a controlled structural feature within a stable lattice framework, which does not compromise the mechanical integrity or phase stability, as evidenced by our stability tests.

Our strategy provides a viable solution to the intrinsic trade-off between efficiency and sub-nanosecond response, surpassing nearly all existing scintillators. This exceptional performance enables significant advancements in medical imaging, including reconstruction-free PET imaging, low-dose CT and dynamic X-ray imaging. Moreover, the rational distortion engineering approach we apply to enhance exciton confinement can be extended to the design of other materials, such as nanocrystals, quantum dots, nanoclusters and low-dimensional perovskites. While the bulk crystals in this study are optimized for scintillation, the underlying photophysics suggests that nanostructured or thin-film versions of these materials could open avenues for efficient electroluminescence. This will further propel the development of applications in LEDs, lasers, quantum light sources, and LiDAR technologies.

Methods

Materials

Cyclohexylmethylammonium (97%), 4-(aminomethyl)cyclohexanecarboxylic acid (99%), 1,3-bis(aminomethyl)cyclohexane (98%) were purchased from Adamas Reagent Co. Ltd. 1,4-cyclohexane-diyldimethanamine (98%), hydrobromic acid (HBr) (40%), were purchased from Aladdin Chemical Co. Ltd. Lead bromide (99.999%) was purchased from Advanced Election technology Co. Ltd. All the chemicals were used as received without any further purification.

Preparation of single crystals and film

The (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 crystal was synthesized using the solution cooling method. PbBr2 (0.15 mmol) and cyclohexane-1,4-diyldimethanamine (1,4-CMA) (0.15 mmol) were separately dissolved in HBr (2 mL and 4 mL, respectively). The solutions were mixed, heated to 120 °C until dissolved, then cooled at 0.5 °C h−1 to promote crystal growth. The (CMA)2PbBr4 crystal was synthesized similarly. PbBr2 (0.5 mmol) and cyclohexylmethylammonium (CMA) (1 mmol) were separately dissolved in 1 ml and 6 ml of HBr. Then the solutions were mixed, heated to 125 °C, then cooled at 2 °C h−1 to allow crystal growth. The (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4 crystal was synthesized by dissolving PbBr2 (0.5 mmol) and 4-(aminomethyl)cyclohexanecarboxylic acid (CMA-COOH) (1 mmol) in HBr. The mixed solution was heated to 100 °C and cooled at 2 °C h−1 to promote crystal growth. The (1,3-CMA)PbBr4 crystal was synthesized by dissolving PbBr2 (0.5 mmol) and 1,3-Bis(aminomethyl)cyclohexane (1,3-CMA) (0.5 mmol) in 1 mL and 3 mL of HBr, respectively. The mixed solution was heated to 125 °C and cooled at 2 °C h−1 for growth. The (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 crystal was mechanically ground for 30 min to obtain micron-sized powders. Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) was dissolved in ortho-xylene by magnetic stirring and heating at 100 °C until fully dissolved. The prepared powders were then mixed with PMMA at a mass ratio of 2:1, followed by mechanical stirring for 24 h. Finally, the mixture was dropped onto a mold. After drying at room temperature for 5–6 h, the film was formed and could be peeled off.

Materials characterizations

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurements were conducted on an XtaLAB PRO MM007HF X-ray diffractometer equipped with a liquid nitrogen cooling system and a Cu Kα radiation source. Powder XRD measurements were performed using a Rigaku MiniFlex600 X-ray diffractometer, utilizing a Mo Kα X-ray tube (λ = 0.71073 Å), operating at 40 kV and 15 mA, with a step size of approximately 0.08° s−1. Photoluminescence and photoluminescence excitation spectra were recorded using an FL3-22 time-resolved fluorescence spectrometer. Ultraviolet-visible-near infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) absorption spectra were obtained using a Lambda 750 s spectrophotometer in transmission mode. Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy measurements were carried out with a Spirit 1040-8-SHG06900 fR Rack LCR1 spectrometer, using a 340 nm pulsed laser for excitation. PLQY was measured using an XPQY-EQE photoluminescence efficiency measurement system. For RL and X-ray imaging, we used X-ray tube (Moxtek MAGPRO 70 kV 12 W) as the source. X-ray photons were generated under an accelerating voltage of 50 kV and operating currents from 20 to 140 μA. The distance between the X-ray tube and the detector varied from 10 to 80 cm. The X-ray dose rate was calibrated using an ion chamber dosimeter (IBA Dosimetry MagicMax). The stability was recorded using an oscilloscope (RIGOL DS1202Z-E). The RL spectra were recorded with a PG2000-PRO spectrometer. X-ray images were captured using a digital camera (FL 20BW). The RL decay dynamics of the scintillators were characterized using a picoX 5084 X-ray excited scintillation lifetime/decay (TRRL) testing system developed by Shanghai UPU Optoelectronic Technology Co., Ltd. The system employs a N16432 photo-excited X-ray tube (Hamamatsu), which generates pulsed X-rays controlled by the illumination of a photocathode. By utilizing a picosecond laser to produce high-repetition-rate, sub-100-picosecond X-ray pulses, the system enables rapid measurements based on time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC).

Structural distortion calculation and statistics

Structural distortion parameters have been calculated (using VESTA software) from the crystallographic data, including both published data and data from crystals synthesized in this work. The intra-octahedral distortion was evaluated by mean of the following parameters50,51,52,53:

where αi are the Br-Pb-Br angles.

The extent of structural distortion within the inorganic framework was quantified through a detailed analysis of the bridging Pb-Br-Pb angles. All calculations were performed based on the Cartesian atomic coordinates derived from the single-crystal X-ray diffraction structure refinement.

The total octahedral tilting (Dtilt) for a given Pb-Br-Pb angle is defined as the angular deviation from the ideal linear geometry: Dtilt = 180° - θPb-Br-Pb, where θPb-Br-Pb was measured from the refined crystallographic information file (CIF) using the angle measurement tool in the VESTA software.

To decouple the distinct components of the total tilt, the three-dimensional Pb-Br-Pb angle was vectorially decomposed into its out-of-plane and in-plane projections. This decomposition was carried out by defining a best-fit plane through the three Pb atoms (Pbi, Pbj, and an adjacent Pbk) constituting the local inorganic layer environment. This approach of using atomic positions to define a local plane, rather than relying on the crystallographic (001) plane, was adopted because in certain cases the Pb atoms do not lie perfectly in the (001) plane.

The unit normal vector (n̂) of this locally defined plane was computed. The vectors corresponding to the Pb-Br-Pb bonds were then projected onto the direction of n̂ (out-of-plane component) and onto the plane itself (in-plane component). The angles between these projected vectors, θout and θin, were calculated using the standard arccosine dot product formula (For vectors a and b, the angle between them is given by θ = cos−1[(a • b) / ( | a | |b | )]).

From these projections, the respective distortion parameters were defined as: Out-of-plane tilting (Dout): Dout = 180° - θout, In-plane tilting (Din): Din = 180° - θin. Here, θout and θin represent the angles between the out-of-plane and in-plane projections of the Pb-Br bond vectors, respectively. The uncertainty δf in an arbitrary function f(x) is δf = |df/dx | ·δx, hence δ(cos−1x) = |(1-x2)−1/2 | ·δx. This results in higher error in D values when the Pb-Br-Pb angles are closer to 180°. This does not represent lower precision in a particular X-ray structure, but is a necessary result of correct error propagation.

Following the calculations, the validity of the vector decomposition was corroborated by verifying that the following relation holds approximately: cos2(θtilt) ≈ cos2(θin) + cos2(θout) – 1, which derives from the spherical law of cosines.

TOF-PET measurement

TOF-PET measurements were conducted using a custom-made standard apparatus. This setup incorporated electronic boards providing dual outputs (energy and timing) and NUV-HD-MT SiPMs manufactured by Fondazione Bruno Kessler (FBK), tested with various coupling materials54,55. The sample crystal pixel was coupled to the SiPM surface using optical grease, and a LYSO:Ce layer was positioned above it. The device has an overall volume of 3 × 3 × 0.4 mm3 and an extraction face of about 3 × 3 mm2. For the reference detector, a bulk 3 × 3 × 5 mm3 LYSO:Ce,Ca crystal sourced from SIPAT (China) was employed. A 22Na source is placed between a pair of facing gamma-ray detectors to form the coincidence system. The detector unit comprises a scintillator for gamma-to-light conversion, followed by a SiPM that generates electrical signals from these photons. These signals are then conditioned by front-end electronics while preserving a high signal-to-noise ratio. To capture the full pulse dynamics and extract all relevant signal features, we utilized an 8 GHz bandwidth oscilloscope (Rhode & Schwarz RTP084) connected to the timing and energy channels45. The device was configured to trigger only on specific voltage thresholds, thereby performing coincidence filtering directly within the hardware.

First-principles calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)56,57. We adopted the projector augmented-wave (PAW) formalism with a plane-wave energy cutoff set to 500 eV58,59. The valence electron configurations were defined as 6s26p2 for Pb, 4s24p5 for Br, 2s22p3 for N, 2s22p2 for C, and 1s1 for H. To describe the exchange-correlation interactions, we employed the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)60. The electronic self-consistency was achieved with a convergence threshold of 10−6 eV. To account for van der Waals forces in the (1,4-CMA)PbBr4 system, the DFT-D361 correction was included. Structural relaxations were conducted until the residual forces on ions dropped below 0.01 eV Å−1. Spin-orbit coupling (SOC) effects were incorporated into the electronic structure calculations. The shell GGA-1/2 (shGGA-1/2) method62,63 was employed to mitigate the inherent band gap inaccuracy of DFT. In the case of Br within (1,4-CMA)PbBr4, we applied optimal inner and outer cutoff radii of 0.6 Bohr and 2.9 Bohr, respectively64. The Gaussian 16 W package was utilized to compute the electrostatic potentials (φ) for the organic A-site cations, applying the B3LYP functional with the 6–31 G(d) basis set. For the analysis of the NH3+ terminal group, the maximum potential φ (φmax) was extracted via the Multiwfn code65.

Calculation of scintillation light yield

We performed a cross-verification using multiple standard scintillators with different light yields and emission wavelengths to ensure the accuracy of our test setup and calibration procedure. We employed two certified reference scintillators (LYSO:Ce and BGO). LYSO:Ce (purchased from Meishan Bora New Materials Co., Ltd., China): Certified light yield of ~32,000 photons MeV−1, emission peak at ~428 nm; BGO (purchased from Meishan Bora New Materials Co., Ltd., China): Certified light yield of 10,000 photons MeV−1, emission peak at ~480 nm.

We measured the pulse-height spectra of both LYSO:Ce and BGO under a 241Am (59.5 keV) γ-ray excitation using a photomultiplier tube (PMT, model R2059, Hamamatsu). The quantum efficiency (QE) curve of this PMT was provided by the manufacturer and is included in Supplementary Fig. 16. A high-voltage power supply (556, Ortec) was used to provide the necessary voltage to the PMT. The output signal from the PMT was read using an oscilloscope (MSO54B 5-BW-2000, Tektronix). The radioactive 241Am, with an activity of 2.85 × 108 Bq, irradiated the crystal through a Be window from a distance of 1 cm. Both the PMT and the 241Am source were placed inside a completely lightproof shielding box. A total of 50,000 pulses were collected using the oscilloscope, processed into a pulse height spectrum, and fitted using a Gaussian function. The light yield of one standard was used to predict the other, following the full spectral correction methodology. The corrected light yield is calculated as:

where C denotes the channel number, and \(\varphi\) is the wavelength dependent detection efficiency correction constant, calculated by convolving each scintillator’s emission spectrum with the PMT’s QE curve:

where Ij(λ) represents the RL intensity of the scintillator, and S(λ) is the wavelength-dependent PMT detection efficiency.

Using LYSO:Ce (LY ~ 32,000 photons MeV−1) to predict BGO’s LY: \({\varphi }_{{{\rm{BGO}}}}\)= 0.1920, \({\varphi }_{{{\rm{LYSO}}}}\)= 0.2691. The measured photopeak channel ratio was CBGO / CLYSO = 0.24 (Fig. 4c). Predicted LYBGO = 32,000 × 0.24 × (0.2691/0.192) = 10,764 photons MeV−1. This value is in agreement with the certified LY of BGO ( ~10,000 photons MeV−1), well within the acceptable uncertainty range for such measurements, considering factors like surface finish and coupling.

We then measured our 2D perovskite scintillator under identical conditions. The calculated φ values were 0.2691 for the LYSO:Ce reference, and 0.2503, 0.2611, and 0.2614 for (CMA)2PbBr4, (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4, and (1,4-CMA)PbBr4, respectively. For each sample, the light yield was calculated using the established comparative formula:

This rigorous calibration procedure, applying all necessary corrections, obtained the final light yields of 50,460, 20,460, and 19,730 photons MeV−1 for (CMA)2PbBr4, (CMA-COOH)2PbBr4, and (1,4-CMA)PbBr4, respectively.

Calculation of X-ray imaging spatial resolution

The spatial resolution of the X-ray imaging system was quantitatively evaluated using the MTF based on the slanted-edge method. Sharp-edge images were acquired by imaging a copper sheet approximately 0.15 mm in thickness. The edge spread function (ESF) was obtained from the edge profile, followed by differentiation to generate the line spread function (LSF). Finally, the MTF was computed by applying a Fourier transform to the LSF, as expressed in the equation below:

where ν is the spatial frequency.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information or upon request from the corresponding authors. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, under deposition numbers CCDC 2502889, 2502891, 2502928, 2502972. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Crystallographic data are also provided as Supplementary Data 1.

References

Dantus, M. Ultrafast studies of elusive chemical reactions in the gas phase. Science 385, eadk1833 (2024).

Roques-Carmes, C. et al. A framework for scintillation in nanophotonics. Science 375, eabm9293 (2022).

Nimmo, K. et al. Magnetospheric origin of a fast radio burst constrained using scintillation. Nature 637, 48–51 (2025).

Gandini, M. et al. Efficient, fast and reabsorption-free perovskite nanocrystal-based sensitized plastic scintillators. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 462–468 (2020).

Ziegler, S. I. Positron emission tomography: principles, technology, and recent developments. Nucl. Phys. A 752, 679–687 (2005).

A. Gektin, M. Korzhik, Inorganic Scintillators for Detector Systems (Springer, 2017).

Lecoq, P. Development of new scintillators for medical applications. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A-Accel. Spectrom. Dect. Assoc. Equip. 809, 130–139 (2016).

Luo, J. et al. Efficient and stable emission of warm-white light from lead-free halide double perovskites. Nature 563, 541–545 (2018).

E. Fermi, Nuclear Physics: a course given by Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago (University of Chicago Press, 1950).

Weber, M. Scintillation: mechanisms and new crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A-Accel. Spectrom. Dect. Assoc. Equip. 527, 9–14 (2004).

Pidol, L. et al. High efficiency of lutetium silicate scintillators, Ce-doped LPS, and LYSO crystals. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 51, 1084–1087 (2004).

Kubota, S., Gen, J. -zR., Itoh, M., Hashimoto, S. & Sakuragi, S. A new type of luminescence mechanism in large band-gap insulators: proposal for fast scintillation materials. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A-Accel. Spectrom. Dect. Assoc. Equip. 289, 253–260 (1990).

Chen, Q. et al. All-inorganic perovskite nanocrystal scintillators. Nature 561, 88–93 (2018).

Klimov, V. I. et al. Single-exciton optical gain in semiconductor nanocrystals. Nature 447, 441–446 (2007).

Becker, M. A. et al. Bright triplet excitons in caesium lead halide perovskites. Nature 553, 189–193 (2018).

Yang, Z., Yao, J., Xu, L., Fan, W. & Song, J. Designer bright and fast CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystal scintillators for high-speed X-ray imaging. Nat. Commun. 15, 8870 (2024).

Du, X. et al. Efficient and ultrafast organic scintillators by hot exciton manipulation. Nat. Photonics 18, 162–169 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Organic phosphors with bright triplet excitons for efficient X-ray-excited luminescence. Nat. Photonics 15, 187–192 (2021).

Ma, W. et al. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) organic molecules for efficient X-ray scintillation and imaging. Nat. Mater. 21, 210–216 (2022).

Wang, J.-X. et al. Heavy-atom engineering of thermally activated delayed fluorophores for high-performance X-ray imaging scintillators. Nat. Photonics 16, 869–875 (2022).

Xu, J. et al. Ultrabright molecular scintillators enabled by lanthanide-assisted near-unity triplet exciton recycling. Nat. Photonics 19, 71–78 (2025).

Jin, T. et al. Self-wavelength shifting in two-dimensional perovskite for sensitive and fast gamma-ray detection. Nat. Commun. 14, 2808 (2023).

Xia, M. et al. Sub-nanosecond 2D perovskite scintillators by dielectric engineering. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211769 (2023).

Yazdani, N. et al. Coupling to octahedral tilts in halide perovskite nanocrystals induces phonon-mediated attractive interactions between excitons. Nat. Phys. 20, 47–53 (2024).

Koegel, A. A. et al. Correlating broadband photoluminescence with structural dynamics in layered hybrid halide perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1313–1322 (2022).

Cortecchia, D. et al. Broadband emission in two-dimensional hybrid perovskites: the role of structural deformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 39–42 (2017).

Mao, L., Wu, Y., Stoumpos, C. C., Wasielewski, M. R. & Kanatzidis, M. G. White-light emission and structural distortion in new corrugated two-dimensional lead bromide perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5210–5215 (2017).

Shao, Y. et al. Unlocking surface octahedral tilt in two-dimensional Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites. Nat. Commun. 13, 138 (2022).

Xie, G., Li, H. & Qiu, L. Recent advances on monolithic perovskite-organic tandem solar cells. Interdiscip. Mater. 3, 113–132 (2024).

Yi, Z. et al. Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) in inverted perovskite solar cells and their tandem photovoltaics application. Interdiscip. Mater. 3, 203–244 (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. Ultrafast (600ps) vacuum-UV reflective scintillation enabled by surface exciton recombination in layered perovskite PEA2PbBr4. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202505665 (2025).

Febriansyah, B. et al. Metal coordination sphere deformation induced highly stokes-shifted, ultra broadband emission in 2D hybrid lead-bromide perovskites and investigation of its origin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 10791–10796 (2020).

Jana, M. K. et al. Organic-to-inorganic structural chirality transfer in a 2D hybrid perovskite and impact on Rashba-Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling. Nat. Commun. 11, 4699 (2020).

Chiara, R. et al. The templating effect of diammonium cations on the structural and optical properties of lead bromide perovskites: a guide to design broad light emitters. J. Mater. Chem. C 10, 12367–12376 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Negative pressure engineering with large cage cations in 2D halide perovskites causes lattice softening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11486–11496 (2020).

Duan, J. et al. Xi, 2D hybrid perovskites: from static and dynamic structures to potential applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2403455 (2024).

Takagahara, T. Effects of dielectric confinement and electron-hole exchange interaction on excitonic states in semiconductor quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 47, 4569 (1993).

Katan, C., Mercier, N. & Even, J. Quantum and dielectric confinement effects in lower-dimensional hybrid perovskite semiconductors. Chem. Rev. 119, 3140–3192 (2019).

Silver, S., Yin, J., Li, H., Brédas, J. L. & Kahn, A. Characterization of the valence and conduction band levels of n=1 2D perovskites: a combined experimental and theoretical investigation. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1703468 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Study on the time response of a barium fluoride scintillation detector for fast pulse radiation detection. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 67, 1893–1898 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Fang, W. H., Long, R. & Prezhdo, O. V. Exciton dissociation and suppressed charge recombination at 2D perovskite edges: key roles of unsaturated halide bonds and thermal disorder. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 15557–15566 (2019).

Zhao, C. et al. Highly diffusive nonluminescent carriers in hybrid phase lead triiodide perovskite nanowires. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202411499 (2024).

Kwon, S. I. et al. Ultrafast timing enables reconstruction-free positron emission imaging. Nat. Photon. 15, 914–918 (2021).

Leem, H. et al. Optimized TOF-PET detector using scintillation crystal array for brain imaging. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 54, 2592–2598 (2022).

Latella, R., Gonzalez, A. J., Benlloch, J. M., Lecoq, P. & Konstantinou, G. Comparative analysis of data acquisition setups for fast-timing in ToF-PET applications. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 8, 743–751 (2024).

Perego, J. et al. Composite fast scintillators based on high-Z fluorescent metal–organic framework nanocrystals. Nat. Photonics 15, 393–400 (2021).

Howansky, A., Mishchenko, A., Lubinsky, A. & Zhao, W. Comparison of CsI: Tl and Gd2O2S: Tb indirect flat panel detector x-ray imaging performance in front-and back-irradiation geometries. Med. Phys. 46, 4857–4868 (2019).

Hou, B. et al. Materials innovation and electrical engineering in X-ray detection. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 639–655 (2024).

Yi, L., Hou, B., Zhao, H., Tan, H. Q. & Liu, X. A double-tapered fibre array for pixel-dense gamma-ray imaging. Nat. Photonics 17, 494–500 (2023).

Thomas, N. W. Crystal structure–physical property relationships in perovskites. Struct. Sci. 45, 337–344 (1989).

Robinson, K., Gibbs, G. & Ribbe, P. Quadratic elongation: a quantitative measure of distortion in coordination polyhedra. Science 172, 567–570 (1971).

Ertl, A. et al. Polyhedron distortions in tourmaline. Can. Mineral. 40, 153–162 (2002).

Fleet, M. Distortion parameters for coordination polyhedra. Mineral. Mag. 40, 531–533 (1976).

Loizzo, P. et al. Characterization of the new FBK NUV SiPMs with low cross-talk probability. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A-Accel. Spectrom. Dect. Assoc. Equip. 1068, 169751 (2024).

Latella, R. et al. Exploiting Cherenkov radiation with BGO-based metascintillators. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 7, 810–818 (2023).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Smith, D. G., Burns, L. A., Patkowski, K. & Sherrill, C. D. Revised damping parameters for the D3 dispersion correction to density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 2197–2203 (2016).

Ferreira, L. G., Marques, M. & Teles, L. K. Approximation to density functional theory for the calculation of band gaps of semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 78, 125116 (2008).

Ferreira, L. G., Marques, M. & Teles, L. K. Slater half-occupation technique revisited: the LDA-1/2 and GGA-1/2 approaches for atomic ionization energies and band gaps in semiconductors. AIP Adv. 1, 032119 (2011).

Xue, K.-H., Fonseca, L. R. & Miao, X.-S. Ferroelectric fatigue in layered perovskites from self-energy corrected density functional theory. RSC Adv. 7, 21856–21868 (2017).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 62275206 to M.X., U2330115 to M.X., T2525023 to G.N., U23A20359 to G.N.), Knowledge Innovation Program of Wuhan-Shuguang Project, Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (SGDX20230116093205009 to G.N., KJZD20240903101307010 to G.N., JCYJ20250604191008011 to G.N.), Innovation Project of Optics Valley Laboratory (OVL2025YZ001 to G.N.), Fundamental Research Project of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (2025BRA012 to G.N.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.N. and M.X. conceived the idea. J.L., M.X., and G.N. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.L. and M.L. carried out most material design, fabrication, optimization and characterizations. P.L., R.L., and G.K. carried out the timing performance and CTR measurement and analyzed the results. J.Y. performed the theoretical simulation and analyzed the results. Z.L. and G.N. carried out light yield measurement. J.W. helped with fabrication of the single crystals. Y.X. helped with measurement of RL spectra. Q.L. helped with data analysis. M.X., G.N., and J.L. wrote the paper. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Weidong Xu, Wei Zheng and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Liao, M., Latella, R. et al. Atomically confined excitons in 2D perovskites for bright and sub-nanosecond scintillation. Nat Commun 17, 820 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67525-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67525-7