Abstract

Head-to-body ratios (HBRs) are important anthropometric traits with direct relevance to human growth, development, and disease risk. However, the role of the proportions between head and body remains understudied, with the genetic basis of HBRs remaining largely unexplored. By applying deep learning models to 38,202 whole-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry images from the UK Biobank, we generated 10 distinct HBR phenotypes based on head (length/width) and various body dimensions. Our genome-wide association analyses identify 245 significant loci, with SNP-based heritability estimates ranging from 25% to 43%. Functional annotations show that genes prioritized for HBRs are enriched in chondrocytes in skeletal tissues and oligodendrocytes across multiple brain regions. Polygenic risk scores and mendelian randomization analyses further showed that HBRs are significantly associated with risks for cardiovascular, metabolic, musculoskeletal, and neuropsychiatric diseases, underscoring their potential value as health-related biomarkers. Evolutionary analyses show that HBR-associated variants are enriched in conserved genomic regions and human accelerated regions, particularly those influencing brain development. Overall, our study provides insights into the genetic architectures of HBRs, establishes their relevance to major human diseases, and offers evolutionary context for their biological significance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mammals and birds have evolved a substantially larger brain for a given body size compared to other vertebrates1,2. Among these, humans exhibit an exceptional degree of brain enlargement relative to body size3,4. Head-to-body ratio (HBR) is an important morphological indicator for describing relative brain size and reflecting normal growth and development. It is also linked to certain genetic disorders or evolutionary adaptations. A larger HBR is often thought to reflect evolutionary selection for enhanced cognitive abilities5. Abnormal HBR is associated with neurological and physical impairments that impact quality of life. For example, autism spectrum disorder is linked to atypical rates of head growth relative to height during early childhood6,7, and excessive early head size growth may be associated with an increased risk of cancer8. Therefore, understanding the factors influencing HBR could provide valuable insights into relevant traits and diseases. Most phenotypes are influenced by both environmental and genetic factors. While evidence from fossil records and global paleoclimatic reconstructions indicated that environmental factors account for only a limited degree of variation in body and brain size9, the extent to which genetic factors contribute to variation in HBR remains unclear and warrants further investigation.

The main elements of the HBR include head length, head width, height, shoulder width, trunk length, hip width, and leg length. However, except for height, these other elements are rarely measured in large sample sizes. While genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified numerous loci associated with height10,11, the genetic basis of HBR remains largely understudied. Recently, deep-learning techniques to noninvasive medical imaging has been proven to be an effective approach for accurately and efficiently extracting anthropometric indicators. Furthermore, the combination of genetic, phenotypic, and imaging data by national biobanks facilitates the exploration for image-derived phenotypes (IDPs) with sufficiently large sample sizes. Several genetic studies have successfully applied computer vision to generate IDPs of the retina12, distribution of body fat13, skeletal measure14, pelvic form15, and heart structure16, linking significant loci to various disorders. Benefiting from these, we can avoid large-scale manual measurements and obtain skeletal measurements with greater accuracy, enabling a deeper investigation into the genetic architectures of HBR.

In this study, we applied computer vision methods to obtain height-adjusted measurements of human head length, head width, and body dimensions (including height, shoulder width, trunk length, hip width, and leg length) from biobank-scale whole-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) images. We generated 10 ratio phenotypes between the head and the body measurements. We then performed genome-wide scans on these HBR phenotypes to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the genetic factors contributing to inter-individual variations in head-related body proportions. Functional annotations showed that the prioritized HBR genes are significantly enriched in somatotropes of the pituitary gland and oligodendrocytes in multiple brain regions. Specifically, we found that loci associated with HBR phenotypes are significantly enriched both in human accelerated regions and regulatory elements of differentially expressed genes between humans and great apes during development. Additionally, we evaluated the phenotypic correlations, genetic risks, and causal relationships between HBRs and common diseases, with a focus on cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, metabolic, and neuropsychiatric disorders. The overall design is shown in Fig. 1.

a We constructed multiple deep learning models to perform quality control and processing on the large-scale DXA image data from the UK Biobank. We constructed a series of image segmentation models, extracted head and body dimensions data, and calculated 10 types of head-to-body ratio (HBR). b Combining the individual genotype data from UKB, we conducted GWASs to identify genetic loci associated with HBRs. Using various analytical methods, we obtained an optimized set of HBR genes and performed functional annotation, MGI phenotypes annotation, and single-cell disease relevance score. c We analyzed the role of HBRs in human evolution. d We explored the association and the causality, between HBRs and common diseases. KYA: kilo years ago, MYA: million years ago, p.c.w: post-conceptional week. Panels c, d were partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. All organism silhouettes are from PhyloPic. DXA images are reproduced by kind permission of UK Biobank ©.

Results

HBRs computation from biobank-scale imaging data using deep-learning

We originally obtained 152,326 whole-body DXA images from UK Biobank (application number 46387). We developed a series of ResNet-15217 models to perform image quality control procedures, including selecting whole-body transparent images, removing cropping artifacts, excluding images with contrast abnormality, and eliminating non-frontal head view images. To enhance the processing capability of models, we processed the images with black and white backgrounds separately (detailed in the Methods). After quality control, a total of 48,410 images were remained (Fig. 2a). To facilitate subsequent GWAS analysis, we only kept the images derived from British white individuals with available genetic data. Finally, data from 38,202 individuals were remained. These individuals are aged between 46 and 86 years, reflecting adult morphology. We report baseline information about this analyzed cohort in Supplementary Data 1.

a This panel illustrates the process of extracting, quality controlling, and categorizing raw DXA images from the UK Biobank using a series of deep learning models, where we retained only the skeletal images with black and white backgrounds in a frontal view. b For the retained images, we manually annotated six landmarks (on the head, shoulders, hips, and ankles) used these to train and apply deep learning models. c We extracted six direct measurements (head length, head width, shoulder width, trunk length, hip width, and leg length) from the images. These were used to calculate the 10 HBRs. DXA images are reproduced by kind permission of UK Biobank ©.

After data quality control, we manually annotated the head mask, which highlights the region of the head in the image, and six pixel-level landmarks (two shoulder joints, two hip joints and two ankle joints) on 400 images under the guidance from orthopedic doctors as training data. We applied computer vision architectures based on the U-Net framework18, using ResNet-15217 as the encoder, for head segmentation and landmarks estimation (Fig. 2b). Upon training, both head segmentation models for background images achieved a Dice loss below 0.0146 and an average intersection-over-union (IoU) score above 0.9744 on the test set. The six landmark models achieved Dice losses ranging from 0.0615 to 0.0857, and IoU scores ranging from 0.8479 to 0.8849. Each model achieved comparable performance on the validation and test datasets, demonstrating that the models were not overfitted and possessed good generalization capabilities (Supplementary Data 3). The detailed workflow for image processing and segmentation is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

After training and validating the deep-learning model on the 400 manually annotated images, we applied this model to segment the head and 6 landmarks on the remaining 48,410 whole-body DXA images. We defined height as the distance from the upper edge of the head to the ankle landmark. Head length was defined as the distance from the crown to the chin, while head width was measured as the maximum horizontal span across the skull, taken at the point where the head is widest. Shoulder width was defined as the distance between the two shoulder joints, and trunk length was defined as the vertical distance from the chin to the hip joint. Hip width was defined as the distance between the two hip joints, and leg length was defined as the vertical distance from the hip joint to the ankle joint. Using these measurements, we calculated 10 HBR phenotypes, namely the head length to body height ratio (LHR), head width to body height ratio (WHR), head length to shoulder width ratio (LSR), head width to shoulder width ratio (WSR), head length to trunk length ratio (LTR), head width to trunk length ratio (WTR), head length to hip width ratio (LHiR), head width to hip width ratio (WHiR), head length to leg length ratio (LLeR), head width to leg length ratio (WLeR), as shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Data 7.

Validation of HBRs estimates

To validate the robustness of the 10 HBR phenotypes, we first compared predictions of our models against values derived from manually annotated masks on a 40-image test set. This comparison yielded Pearson correlation coefficients all above 0.98 and normalized mean squared errors between 0.0202 and 0.0374 (Supplementary Fig. 3a, Supplementary Data 6). We further evaluated the reproducibility of our measurements through three tests. First, the correlation between torso length and leg length derived from the left and right limbs was 0.9250 and 0.9938, respectively, indicating high internal consistency (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Second, using repeat scans from 3632 individuals obtained at an average interval of two years, the test-retest correlation for HBRs ranged from 0.8435 to 0.9685 (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Third, to assess robustness to technical variations, we examined 500 samples with images containing two different background colors and found that the HBR correlations remained high, ranging from 0.8487 to 0.9728 (Supplementary Fig. 3d). We also downloaded the GWAS summary data of head width generated by Xu et al.15, the genetic correlation analysis result with our GWAS data for head width showed a relatively high genetic correlation with r = 0.7705. These results demonstrate that the IDPs generated by our deep learning model are highly reproducible.

With the reliability of the HBR measures established, we next investigated their population-level characteristics. We observed that all the HBR values conform to the characteristics of a normal distribution (Supplementary Fig. 3e), and a moderate negative correlation between HBR phenotypes and height (r2 ranged from 0.0447 to 0.4974, Supplementary Fig. 3f).

Genome-wide association analyses on HBRs

We performed GWASs using imputed genotype data in UKB to identify variants associated with the 10 HBR phenotypes. After quality control (Supplementary Data 8), 38,202 individuals of white ancestry from British and 7,459,980 common biallelic single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were included in our analyses.

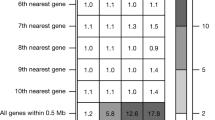

Across the 10 HBR phenotypes, our GWAS identified a total of 7394 significant (p < 5 × 10−8) SNPs located at 245 independent loci (Fig. 3a-b, Supplementary Fig. 4). After conditioning on all lead SNPs of independent loci discovered in a saturated GWAS for height11, 46 loci remained significant (Supplementary Data 10). The minimal deviation of univariate LD Score regression (LDSC)19 intercepts from 1.0 suggested that this inflation was attributed to polygenicity rather than to confounding (Fig. 3b). Based on the generated summary statistics for each HBR, the proportion of phenotype variance explained by SNPs for all HBR phenotypes ranged from 25.27% to 42.86%, indicating that HBRs are moderately heritable (Fig. 3c).

a Combined Manhattan plot for all HBRs, where only the nearest coding genes to the most significant SNPs within 5 Mb are annotated. We randomly sampled 50,000 SNPs with −log10(p)≤5, and retained all SNPs with −log10(p)>5. GWAS p-values were calculated using BOLT-LMM. b The total number of genome-wide significant SNPs (Ngw, SNP) and loci (locus) for each HBR, along with the intercept calculated by LDSC. c Bar plot shows the SNP heritability of each HBR. The estimated heritability and its standard error (error bars) are derived from LDSC.

To investigate the extent of genetic overlap among the HBRs, we calculated the genetic correlation between each pair. All HBRs showed positive phenotypic correlations (r ranged from 0.1516 to 0.9436), and the genetic correlations between HBRs were also positive, ranging from 0.1968 to 0.9309 (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Data 11). We observed that phenotypes divided by trunk length and leg length were indeed highly correlated with those divided by height (\({r}_{g}\) > 0.8). To be concise, the results for four HBRs based on trunk and leg length are only presented in the Supplementary Data 12–25.

To identify causal variants associated with HBRs, we conducted fine-mapping and identified 61 loci that had five or fewer causal variants within the 95% credible set, and two loci that had one causal variants (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Data 12). For example, FINEMAP20 nominated rs41271299 as the sole putative causal variant in the 6q22.3 locus associated with LLeR. Moreover, it remained significantly associated with LLeR in height-conditioned analyses, suggesting its association with LLeR is independent from height.

Gene prioritization of HBRs

We used four methods for gene prioritization: genomic annotation using ANNOVAR21, transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS22), GWAS colocalization analysis (COLOC23), and summary data-based mendelian randomization (SMR24) by integrating GWAS and eQTL data on the brain and whole blood from the GTEx project (V8). For TWAS and SMR, we retained genes that remained significant after multiple testing correction. For colocalization analysis, we set the threshold of posterior probability of hypothesis 4 (PPH4, indicating shared causal association between GWAS and eQTL) as 0.9. Finally, we identified 608 protein-coding genes associated with HBRs supported by at least one of the four analysis results (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 13).

a Summary of evidence categories for prioritized genes. This panel displays 40 genes supported by at least three out of four analytical methods for six HBRs. “TWAS” indicates significant results from Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies in any selected tissue, “COLOC” indicates significant results from colocalization analysis in any selected tissue, “SMR” indicates significant results from Summary Data-Based Mendelian Randomization in any selected tissue, “Closest” indicates that the gene is the nearest gene within 35k bp of the GWAS significant loci, and “Muti-phenotype” indicates whether the gene is associated with more than three HBR phenotype. b The region plots of gene WNT16. From top to bottom, the plot shows the significant TWAS results of three HBRs around WNT16. P-values were calculated using MR-JTI and adjusted using Benjamini-Hochberg correction. The upper triangle represents cases where the TWAS z-score is greater than 0, while the lower triangle represents the opposite. c, d The bubble plots show all GO BP terms and KEGG pathways enriched in six HBRs (via one-sided hypergeometric tests), arranged in the order of manual categorization. The size of the bubbles represents the number of genes in each term, and the color indicates the FDR-adjusted p-value. e The bar plots illustrate the annotation counts of mouse phenotypes related to the skeleton, head, or brain. These phenotypes have been annotated with priority genes at least eight times across six HBRs. LHR: head length to body height ratio, WHR: head width to body height ratio, LSR: head length to shoulder width ratio, WSR: head width to shoulder width ratio, LHiR: head length to hip width ratio, WHiR: head width to hip width ratio.

Nearly half (285/608) of these prioritized genes are associated with more than one HBR, and more than 20% of these genes are linked to at least three HBRs. For example, WNT16 was found to be associated with WHR, WHiR, and WSR, as shown in Fig. 4b. WNT16 gene has been proposed to signal via the non-canonical pathway, influencing bone mineral density, cortical bone thickness, and bone strength25. Additionally, WNT16 had lead variants in the GWAS of brain structural connectome26, and includes GWAS signals associated with brain volume measurement27.

Biological insights from HBRs associations

To identify relevant biological processes or pathway for the prioritized genes, we performed gene set enrichment analysis for each HBR separately using data from the Gene Ontology (biological process category, GO-BP)28 and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)29 database. This analysis revealed that the prioritized genes are enriched in 32 GO-BP terms (Fig. 4c), most of which are related to organ development, skeletal and connective tissue development, and growth hormone signaling (Supplementary Data 14). The prioritized gene sets are also enriched in 11 KEGG pathways directly associated with body development and metabolism (Fig. 4d), such as growth hormone synthesis, secretion, and action pathway30. These genes are also enriched in the cardiovascular JAK-STAT signaling pathway, whose dysregulation may lead to inflammation and cardiovascular diseases31 (Supplementary Data 15).

We further evaluated whether the prioritized genes are associated with skeletal or brain-related phenotypes in the mouse using the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) database32. The results indicate that, in addition to being broadly annotated with various phenotypes related to mouse body length, the HBR prioritized genes are also associated with six distinct brain-related phenotypes, including “abnormal forebrain development” and “abnormal neurocranium morphology” (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Data 16).

Cell types associated with HBRs

To identify relevant cells exhibiting excess expression across disease-associated genes implicated by GWAS, we performed single-cell disease-relevance score (scDRS)33 analysis using single-cell RNA sequencing data from 11 brain regions classified according to conventional brain structures34,35, as well as five human skeletal tissues (cranium, skull base, shoulder, hip, knee)36. The single-cell data comprised 3750 to 134,262 cells for brain-related datasets and 49,263 to 100,869 cells for skeletal-related datasets.

We identified 44 cell type-phenotype association pairs across brain regions and skeletal tissues (Supplementary Data 13). Notably, oligodendrocytes from five brain regions (cerebral cortex, cerebral nuclei, hippocampal formation, hypothalamus, and thalamic complex) were found to be associated with six HBRs (LHR, LHiR, LLeR, WHR, WHiR and WLeR). In addition, somatotropes in the pituitary tissue were also associated with WHR, and WSR. In skeletal tissues, WHR was associated with chondrocytes in all five skeletal tissues, while LSR was linked to early progenitors and endothelial cells in the shoulder. Furthermore, the two types of bone tissue cells were associated with corresponding body proportion phenotypes, specifically, LHiR was linked to chondrogenic and osteogenic cells in the hip, and WLeR was associated with chondrogenic cells in the knee (Fig. 5). These findings highlight the critical role of these cell types in the development of HBR phenotypes.

Single-cell UMAP plots for five skeletal-related tissues and seven brain regions were annotated based on scDRS results for each cell type, highlighting significant associations with one or more HBR phenotypes. Different colors represent the HBR phenotype significantly associated with cell type. In cases where a cell type is associated with multiple HBR phenotypes, the different HBRs phenotypes were evenly distributed among the cells of that type. LHR: head length to body height ratio, WHR: head width to body height ratio, LSR: head length to shoulder width ratio, WSR: head width to shoulder width ratio, LHiR: head length to hip width ratio, WHiR: head width to hip width ratio. This figure was partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Evolutionary analysis

Both mammals and birds have evolved substantially larger brains relative to their body size compared to other vertebrates37, which might be related to the shared evolutionary characteristics between the two groups. Therefore, we investigated whether the variants associated with HBR phenotypes are enriched in genomic regions conserved between birds and mammals. We excluded genomic regions shared with reptiles and amphibians, focusing only on the genomic regions conserved between mammals and birds38 (Fig. 6a left). By comparing the distribution of HBR-associated variants to the matched randomly selected background SNPs, we found that HBR-associated variants are significantly enriched in the conserved genomic regions of mammals and birds, excluding those shared with reptiles and amphibians (p < 0.002, Fig. 6a right, Supplementary Data 18). These results suggest that mammals and birds may have evolved larger brains independently, but through similar genetic mechanisms, implying that convergent evolution might be at play, where different lineages adopt similar genetic pathways to achieve a common phenotypic trait of an increased brain size relative to body size.

a The left panel is a schematic diagram of genome conservation shared between mammals and birds. The bar plot shows the enrichment (via one-sided permutation tests) of GWAS-significant SNPs for all HBRs in the shared conserved regions of bird and mammalian genomes, after excluding and intersecting with the genomic regions of reptiles and amphibians. b The bar plot shows the enrichment (via one-sided permutation tests) of GWAS-significant SNPs for HBR phenotypes, psychiatric disorders, and skeletal diseases in human accelerated regions. P-values are adjusted using Benjamini-Hochberg correction. c, d The heatmaps show the enrichment for HBR phenotypes across different human evolution-related genomic annotations, as determined by FDR-adjusted one-sided permutation tests. Asterisks indicate significant FDR-adjusted p-values, while the color gradient represents the odds ratio of HBR loci compared to matched loci within each annotation. LHR: head length to body height ratio, WHR: head width to body height ratio, LSR: head length to shoulder width ratio, WSR: head width to shoulder width ratio, LHiR: head length to hip width ratio, WHiR: head width to hip width ratio. KYA: kilo years ago, MYA: million years ago, p.c.w: post-conceptional week. All organism silhouettes are from PhyloPic.

Considering relatively larger brain size in humans contributes to superior cognitive abilities compared to non-human primates39, we also investigated whether variants associated with HBR phenotypes overlapped with human accelerated regions (HARs) more than expected. HARs are genomic elements that are highly conserved across vertebrate and great ape evolution but exhibit significantly accelerated substitution rates in human40. The results showed that genetic signals from five HBR phenotypes (WHR, WSR, WTR, LHR, and WLeR), particularly those related with head width, are significantly enriched in HARs (FDR-adjusted p < 0.05, Fig. 6b, Supplementary Data 19). Similarly, traits related to neurological and cognitive disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorder and cognitive abilities) are also enriched in HARs, although not as significantly as the HBR phenotypes. In contrast, skeletal diseases such as joint pain and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are not significantly enriched. These results suggest that genetic variants associated with HBR may be more closely linked to the evolution of human brain development.

We further examined the enrichment of genomic annotations reflecting divergence at various evolutionary time points from great apes to Homo sapiens. These annotations include regions that exhibit differences in epigenetic elements (such as enhancers and promoters) between humans and primates during early developmental stages41, as well as that acquired novel functions in the adult brain after the human divergence from rhesus macaques and chimpanzees42. Except for LSR, LTR, and WSR, most HBR phenotypes showed extensive enrichment in regulatory regions linked to human-ape differences during both fetal development and adulthood (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Data 20). This enrichment indicates that genetic variants associated with HBR phenotypes may result from evolutionary changes at critical developmental stages, influencing early growth and adult traits in humans compared to great apes. Moreover, we examined the enrichment of selection in the modern human lineage since diverging from the common ancestor with Neanderthals and Denisovans43.

The results showed that all head-width-related HBRs were significantly enriched (adjusted p < 0.05) in depleted regions of archaic human genomes, whereas head-length-related HBRs were not (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Data 20). These results suggest that the further evolution of head-width-related HBRs after the divergence from great apes is associated with specific adaptations in modern humans, while head-length-related HBRs may have a weaker functional relationship with adaptive evolution. This disparity may be due to the more direct influence of head width on brain capacity compared to head length.

Phenotypic and genetic association of HBRs with common diseases

We mainly focus on diseases of the five major systems, including psychiatric44,45, neurological44,45, skeletal46, cardiovascular50,51, and metabolic diseases47,48, which may have potential relationships with HBRs according to published studies. We utilized the ICD-10 diagnoses from the UK Biobank and only common diseases with more than 1000 cases in the cohort were included in our analyses (Supplementary Data 21).

As shown in Fig. 7a and Supplementary Data 22, among the 133 significant association pairs, 78.95% exhibit negative correlations. For example, all 10 HBRs were negatively associated with atrial fibrillation (AF), and previous research corroborates this by demonstrating an association between AF and smaller brain volume49. We also observed that WHR was positively associated with ten diseases, such as hypertension (OR = 1.09, adjusted p = 1.07 × 10-8) and mononeuropathies of the upper limb (ULMN, OR = 1.26, adjusted p = 1.99 × 10-11). These results suggest that the HBR phenotypes are biologically meaningful and can reflect underlying health traits.

a Heatmap of the associations between HBRs and various diseases, based on logistic regression analysis with two-sided Wald test. The color scale represents the odds ratio (OR), while asterisks (*) denote significance after Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction. The square size indicates the level of significance, corresponding to five tiers (from largest to smallest: FDR-adjusted p < 1 × 10-8, 1 × 10-4, 0.01, 0.05, and FDR-adjusted p > 0.05). b Heatmap showing the genetic association between the polygenic risk scores of HBRs and diseases, based on logistic regression analysis with two-sided Wald test. The color scale represents the odds ratio (OR), while asterisks (*) denote significance after BH correction. The square size indicates the level of significance, corresponding to five tiers (from largest to smallest: FDR-adjusted p < 1 × 10-8, 1 × 10-4, 0.01, 0.05, and FDR-adjusted p > 0.05). c Heatmap of Mendelian Randomization results using the Inverse-Variance Weighted method, treating HBRs as exposures and diseases as outcomes. The color represents the OR, and asterisks indicate a significant causal estimate after BH correction. The square size corresponds to four tiers of significance (from largest to smallest: FDR-adjusted p < 5 × 10-4, 5 × 10-3, 0.05, and FDR-adjusted p > 0.05). LHR: head length to body height ratio, WHR: head width to body height ratio, LSR: head length to shoulder width ratio, WSR: head width to shoulder width ratio, LHiR: head length to hip width ratio, WHiR: head width to hip width ratio.

We next investigated whether the PRS generated from our GWAS results could predict the status of common diseases. To avoid overlap between the GWAS cohort and the tested individuals, data from 315,392 UKB participants of white British ancestry who did not have DXA image data were used for PRS analyses. PRS were generated using Bayesian regression with a continuous shrinkage prior50. Logistic regressions were then used to examine the relationship between the generated PRS and disease outcomes. As shown in Fig. 7b and Supplementary Data 23, after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction, most of the HBR phenotypes are associated with a trend toward lower disease risk (84.78%). This includes cardiovascular diseases such as AF, heart failure, and varicose veins, as well as metabolic or musculoskeletal disorders like type 2 diabetes and RA. However, eight HBR phenotypes are linked to an increased risk of developing ULMN, the plausibility of this association is supported by previous studies that have described connections between peripheral nerve conditions and brain structure51,52. These findings suggest that PRS effectively capture genetic risk factors of HBR associated with these diseases.

Mendelian randomization to assess the causal effects of HBRs on disease status

We further applied two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) to investigate the causal effects of HBR phenotypes on 46 common diseases from five physiological systems. Our analysis identified a total of 46 significant causal associations (Fig. 7c, Supplementary Data 25). Consistent with the phenotype correlation and PRS analysis, the majority (75.76%) of these associations are protective. Specifically, the significant causal effects of HBR phenotypes on cardiovascular, metabolic, and musculoskeletal system diseases were generally protective. LHR, WHR, LSR, and WSR were consistently negatively associated with risks of AF, RA, and osteoarthritis. However, the effects of HBR phenotypes on psychiatric disorders were predominantly risk-increasing, with a notable exception being WHiR, which was negatively associated with the risk of schizophrenia (OR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93 to 0.98, adjusted p = 0.006). For example, WHR, WHiR, and LTR were risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease, and WSR was positively associated with the risk of bipolar disorder (OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.09, adjusted p = 0.002).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed 38,202 whole-body DXA images from the UKB using deep learning to extract various HBRs data, and explored the genetic basis of HBRs. Our GWAS identified 245 independent genetic loci associated with HBRs. Through integrative analyses, we identified 608 coding genes potentially related to HBRs, characterized their primary functions, and pinpointed the main cell types where these genes are active. Moreover, we linked HBRs to various conserved or specific genomic regions involved in human evolution. Finally, we examined association and causality between HBRs and common diseases such as cardiovascular, metabolic, musculoskeletal, and neuropsychiatric diseases.

To better reflect our primary objective, we analyzed HBR by dividing head size by body measurements. Compared with metrics that examine only the head or the body, HBR provides a more comprehensive perspective. It is important not only as a key morphological trait in human evolutionary adaptation53,54, but also as a crucial indicator of growth and development, with established associations with a range of psychiatric44,45, neurological6,55, and skeletal disorders46. We compared our GWAS results on HBRs with the phenotypes adjusting for body measurements as covariates, following previous studies14,15. Although there are global genetic correlations between the ratio-based and covariate-adjustment phenotypes, the overlapped GWAS significant loci were limited, indicating the divergence at the locus-specific level (Supplementary Data 9).

Our HBR GWAS uncovers genetic insights linked to fundamental biological processes. Notably, over one-sixth of the loci identified in the GWAS on HBRs were conditionally independent of loci in previous GWASs related to height11,56. Enrichment analysis and MGI phenotypes annotation of the prioritized genes highlighted their important roles in body development-related pathways. These genes also exhibited substantial enrichment in key signaling pathways essential for cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. and are closely associated with various common human diseases, including cardiovascular diseases57, chronic inflammatory diseases31, and metabolic disorders58,59.

We found that HBR-related genes are associated with somatotropes in the pituitary and oligodendrocytes in the hypothalamus. The hypothalamic–neurohypophyseal system regulates essential physiological processes such as growth, metabolism, and reproduction by secreting various hormones, which directly influence cardiovascular diseases60,61, insulin sensitivity62, and inflammation63. Dysfunction of oligodendrocytes has been linked to various psychiatric64,65,66 and neurological67 disorders. HBR-related genes are also associated with early progenitors and endothelial cells in multiple skeletal tissues. Early progenitors provide a direct cellular source for skeletal growth68, while endothelial cells play a crucial role in the onset and progression of RA69, which may explain the association between HBRs and RA. These findings suggests that HBR-related genes may influence broad regulatory mechanisms underlying human health and diseases by modulating complex physiological processes in living organisms.

We further investigated the associations and potential causality between HBR and diseases of the five major systems. We found that HBRs generally have a protective effect against cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and metabolic diseases, which is consistent with previous neurological research47,48,49. Given the significant inverse correlation between HBR and height, this observation is interesting as greater height is also reportedly protective against these diseases70,71,72. A potential explanation is that HBR reflects some characteristics or developmental features of the head that directly influence health risks, as head size shows a stronger association with these diseases than height (Supplementary Data 24), suggesting that cranial development is the primary driver of this protective effect. Conversely, our study identified a higher HBR as a significant risk factor for certain neuropsychiatric disorders. This is in agreement with existing studies on conditions like Alzheimer’s disease73,74,75,76 and developing ULMN51,52. These findings indicate that HBRs are complex biomarkers that are associated with beneficial physical outcomes but also increase the risk of neurological problems, and they highlight their potential as accessible markers for disease risk stratification, which may support public health efforts through proactive management and targeted prevention strategies.

Compared to other vertebrates, both mammals and birds have evolved substantially larger brains relative to their body size37, a trait associated with their advanced cognitive functions77. Specifically, birds with the most complex vocal learning abilities were also the best problem solvers and had the largest brains relative to body size78. In addition, both of them could maintain a relatively stable body temperature79, which may be associated with the role of HBR in thermoregulation. Our evolutionary analysis revealed that HBR-related variants are enriched in conserved genomic regions shared by mammals and birds, highlighting their crucial role in the evolution of brain development beyond body size constraints. Additionally, HBR-related variants are also enriched in human accelerated regions, indicating that HBR has undergone significant evolutionary divergence from other great apes during the long course of human evolution. We also observed differences in the HBR regulatory elements between humans and great apes during the embryonic stage, suggesting that species-specific early development drives the differences in HBR. Fossil reconstructions reveal that the shape of the modern human brain evolved to become nearly spherical80, with the width of the head narrowing throughout evolution81,82. As human body size increased, the HBR gradually decreased during human evolution, resulting in a substantial difference in HBR between humans and great apes83. These findings underscore the complex evolutionary changes that have shaped human body proportions, particularly the head-to-body ratio.

Our study has several potential limitations. First, the GWASs were restricted to individuals with European ancestry, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Further studies are needed to evaluate the transferability of the results across diverse ancestries. Secondly, although we employed deep learning to standardize image data with the head facing forward as much as possible, the impact of posture on head measurements could not be entirely eliminated. Additionally, due to challenges in correcting for foot positioning, we excluded the extraction of height below the ankles. This resulted in a partial omission of total body height, causing the calculated LHR and WHR to be slightly larger than conventional values, with averages of approximately 0.12 and 0.09, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3e). However, considering the relationship between ankle height and head length, HBRs we calculated are consistent with conventional adult proportions84.

Taken together, our study systematically investigated the genetic basis of various human HBRs in a large-scale sample. We identified genetic loci associated with HBR phenotypes, along with corresponding coding genes and regulatory pathways. We pinpointed the cell types influencing HBRs and linked these findings to specific diseases. Furthermore, we uncovered genomic evidence of evolutionary changes underlying differences in HBRs between humans and great apes. These findings enhance our understanding of human body structure and its functional significance, highlighting potential impacts on human health and diseases.

Methods

UKB participants and dataset

All analyses were performed using data from the UKB unless otherwise specified. The UKB is a large-scale, prospective, population-based cohort study that recruited 500,000 participants in the United Kingdom via mailed invitations starting in 200685. For this study, we analyzed data from 486,737 participants with available genetic data who had not withdrawn their consent as of August 20, 2020. Among these participants, approximately 80,000 had DXA imaging data released by the UK Biobank under bulk data field ID 20158, with 76,320 having accessible data as of November 13, 2023, along with baseline metadata including age, sex, and other relevant study variables.

The DXA images were acquired using an iDXA instrument (GE-Lunar, Madison, WI). For each participant, a series of up to 8 types images were captured: two whole-body images - one focusing on the skeleton and the other on adipose tissue, as well as images of the lumbar spine, the lateral spine from L4 to T4, each knee, and each hip. The bulk download provided 76,320 zip files, each corresponding to a specific patient identifier, commonly referred to as each EID of patient. Each zip file contains several DXA images of the patient, though not necessarily all, as described above.

Sample size selection for deep-learning models

Our sample size selection procedure was conducted as a two-stage process to ensure both statistical validity and practical utility. First, we employed different models to sequentially remove different categories of unqualified images (e.g., incomplete, abnormal contrast or resolution, and exhibited non-frontal head posture). The proportions of different types of unqualified images are different in the dataset. To ensure robust feature learning, we manually annotated varying sample sizes per model to include at least 50 instances of each unqualified category, following the guidance of previous studies86,87. Next, using the manually annotated data, we employed a progressive sampling strategy: iteratively expanding training sets until performance gains plateaued. Specifically, for each sample size, we performed 30 iterations of randomly splitting the dataset (80% training, 10% validation, 10% testing). In each iteration, we recorded the model’s loss and evaluation metric (AUC or IoU) on the test set of each task.

As shown in the Supplementary Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2b, the model performance (AUC↑ or IoU ↑ , Loss ↓ ) improved significantly with more data initially but eventually plateaued, indicating that further sample increases yielded negligible gains. The final sample size for each model was chosen as the largest number within this stable performance plateau, ensuring we leveraged our annotated data efficiently. This resulted in the final sample sizes: 300 for body-class model, 500 for crop-class model, 800 for contrast-class and pose-class model, and 200 for all segmentation models

Classification to extract whole-body skeleton DXA images

We utilized Pydicom88 to extract metadata from the DICOM files, screened 152,326 “Total Body” images from 71,167 participants, converted the images into PNG and NPY formats, and excluded low-quality images with PNG file sizes of less than 40 KB. To extract the skeleton radiographs, we built a U-Net-based 2-classification model to classify two whole-body images.

We randomly selected 300 images for manual annotation, and randomly divided them into training, validation, and testing datasets in an 8:1:1 ratio (the same dataset partitioning strategy was used for all subsequent models). Using ResNet-15217 in the Python library Torchvision (v0.16.1)89 as encoder, using cross entropy as loss function, we trained for up to 10 epochs, and kept the best model on the validation set, which also had 100% accuracy on the test set. This classifier was run on all DXA images obtained from the UKB. After classification and removal of images, we were left with 76,153 whole-body skeleton DXA images (Supplementary Data 2).

Removal of poorly cropped images

After we determined the final set of whole-body DXA images, we performed additional quality control to remove images that were improperly cropped or had portions of the ankles or shoulders cut off. To do this, we created a binary classifier using Torchvision to differentiate between cropped and non-cropped images. We randomly selected 500 images for manual annotation. A CNN based on the ResNet-152 architecture was trained on this data for up to 30 epochs using cross-entropy as the loss function. The results had an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 1.00 on validation data and testing data (Supplementary Data 3). Removal of all the cropped images resulted in a total of 69,025 whole-body images that we used for analysis.

Image standardization and background differentiation

The whole-body DXA images are varied in both pixel dimension and background, which will limit the performance of the segmentation model. In all the subsequent deep learning models, we trained two separate series of models, one for black background and one for white background. Broadly, the images comprised two main size specifications: black-background images were typically 681-811 by 272 pixels, while white-background images were generally 936-943 by 316-372 pixels. All images were padded to a standardized maximum height and width (960 × 384 pixels) using the methods described in ref. 14. After removing 15 images with abnormal background pixels, we retained 51,432 black background and 17,593 white background complete whole-body skeleton DXA images, respectively.

Removal of images with abnormal contrast

In the whole-body images with both backgrounds, we found that some images had too high contrast due to the UKB image processing, making it difficult to distinguish the details of the bones. To remove these images, we created a binary classifier using Torchvision for each background type. We randomly selected and manually annotated 800 images for each background. These images were trained for up to 30 epochs using a CNN based on the ResNet-152 architecture, with cross-entropy employed as the loss function. The results had an AUC of 1.00 on validation data and testing data of both backgrounds (Supplementary Data 3). After removing images with contrast anomalies, we retained 45,514 black background and 14,597 white background complete whole-body skeleton DXA images, respectively.

Classification of head pose

Since the head posture of the participants will affect the projected shape of the head when acquiring DXA images, we built a binary classification model to distinguish between images with direct gaze and non-direct gaze postures. We also randomly selected and manually annotated 800 images for each background. These images trained for up to 30 epochs using a CNN based on the ResNet-152 architecture, with cross-entropy employed as the loss function. The results show that the validation set AUC is 0.9732 and the test set AUC is 0.9683 in the black background images, and the validation set AUC is 0.9769 and the test set AUC is 1.00 in the white background images (Supplementary Data 3). After removing non-frontal images, we retained 36,319 black background and 12,091 white background complete whole-body skeleton DXA images, respectively. To ensure these filtering steps did not introduce selection bias, we then analyzed its effect on key phenotypes. Statistical analysis confirmed a negligible effect on both sex and age distributions (Tables S4 and S5). Although the Chi-squared tests for sex yielded significant p-values, the corresponding Cramér’s V values90 were all near or below 0.1. Likewise, Cohen’s d values91 from t-tests for age were all below 0.2, indicating a negligible impact.

Deep learning-based image segmentation models for identifying head and joint landmarks

To train our deep learning models, we manually annotated a total of 400 images, with 200 on a black background and 200 on a white background, under the guidance of the orthopedic doctors. We used 160 images of each type for training, and the rest were evenly split for validation and testing. The images that were chosen for this training dataset had an equal number of male and female individuals, were from the white British population group, and sampled equally across the age distribution of the UKB cohort.

We used the open-source annotation tool LabelMe92 in polygon mode to outline the head, and to label six body landmarks (left shoulder, right shoulder, left hip, right hip, left ankle, and right ankle). For masking each of these landmarks, the locations specified below were chosen because they were the easiest and most consistent to identify across all the images, which featured slightly different poses. The center of the head of the humerus was chosen to be masked for each shoulder landmarks. The center point of the tibial plateau was selected as the masking point for each hip joint landmark. The point where the ends of the tibia, fibula, and talus converge was chosen to be masked for each ankle landmarks. An example of the annotation of one image is shown in Fig. 2b with landmarks placed at each of the locations listed above.

We applied the U-Net architecture models with ResNet-152 encoders from the library Segmentation Models Pytorch (SMP, v 0.3.3) to perform image segmentation on the head and the six joint landmarks. The default pre-trained weights provided by SMP were used. Dice loss was employed as the loss function, and training was conducted for up to 50 epochs, retaining the model with the best performance on the validation set for testing.

Obtaining head and body measurements and calculating HBRs

A major issue in integrating our analysis across different input pixel ratios was that these ratios corresponded to varying resolution scales, likely due to the differing distances at which the scanner was held above the patient. For instance, in one image, a pixel might represent 0.44 cm, while in another it could represent 0.46 cm. To address this scaling issue and standardize the images, we decided to regress the height directly measured on the image using the top of the head and the midpoint of the two ankle landmarks, which could be consistently identified across all image pixel ratios. We also incorporated overall height data extracted from the DICOM meta information. Although the height measurements we used did not include the area below the ankles, they were relative measurements, and we utilized them to derive a scaling factor for the pixel ratio in each image to achieve standardization.

We calculated the head length and head width based on the bounding box around the head, and the shoulder width, trunk length, hip width, and leg length based on the center points of the landmarks. Individuals whose length measurements deviated from the mean by more than 3 standard deviations were excluded from the analysis. We calculated the ratios of head length and head width to the corresponding body measurements. A list of these HBRs can be found in Supplementary Data 7.

Participant and Genetic data quality control

For genome-wide association analyses, we filtered participants with correctly labeled whole-body DXA images (FID 20158) to include only Caucasian individuals (FID 22006) from the White British population, as determined by genetic PCA (FID 21000). We removed individuals who were outliers for heterozygosity or genotype missingness rates, as determined by UKB quality control of sample processing and DNA preparation for genotyping (FID 22027), individuals with missingness rates greater than 2% (FID 22005), and individuals with a kinship coefficient greater than 0.0442 (corresponding to at least one third- to fourth-degree relative). A total of 38,202 individuals remained (Supplementary Data 8).

Imputed genetic data for 486,737 individuals was downloaded from UKB for chromosomes 1 to 22 (FID 22828) and subsequently filtered to the quality-controlled subset using PLINK293. All duplicate SNPs were excluded (--rm-dup exclude-all) and only biallelic sites were retained (--snps-only just-acgt), with a maximum of 2 alleles (--max-alleles 2), a minor allele frequency of at least 1% (--maf 0.01), and genotype missingness no greater than 2% (--geno 0.02). A total of 7,459,980 SNPs remained in the final dataset.

GWAS and heritability analysis

Each HBR was used as a ratio phenotype in a GWAS performed with BOLT-LMM94. Covariates included the first 20 genetic principal components (FID 22009) provided by UKB, sex (FID 31), age (FID 21003), and “BACKGROUND”. Additionally, the DXA scanner serial number and the software version used for image processing were combined into a single categorical covariate with seven categories. Independent SNPs in each resulting GWAS were calculated using GCTA COJO24 (--cojo-slct) with a significance threshold of 5.0 × 10⁻⁸, and a window size of 1 M bp for SNP heritability. Genetic correlations were calculated using LDSC. We then obtained all genome-wide significant, independent loci (n = 7209) from Yengo et al.11, which were used in a conditional analysis with GCTA COJO for each of the HBR phenotypes.

Gene prioritization and functional annotation

For gene prioritization, we employed TWAS, COLOC, and SMR using eQTL data from GTEx project(V8)95. For each of the 10 HBRs, we utilized whole blood and 14 head-related and brain-related tissues (details in Supplementary Data 13). All tissues were pooled and corrected together, retaining genes that were significant in any tissue with an adjusted p-value after BH correction of less than 0.01. For COLOC, genes with a PPH4 > 0.9 were retained. We performed TWAS, SMR, and COLOC based on inferred cis-regulated gene expression using MR-JTI22, coloc23 and GCTA24 with default settings. The gene expression weights for TWAS and COLOC were downloaded from https://zenodo.org/records/3842289, and the eQTL summary data for SMR were downloaded from https://yanglab.westlake.edu.cn/software/smr/#DataResource. Pathway enrichment analysis was separately performed for each individual HBR using the R package clusterProfiler96. The resulting terms were adjusted for multiple comparisons using BH correction method, and terms with fewer than five hit genes were excluded. Relevant MGI phenotypes were manually selected from the mouse phenotype descriptions that included the terms “bone,” “skeletal,” “head,” and “brain.” Subsequently, we counted the number of genes annotated to these phenotypes within each HBR.

Associating cell types with HBR phenotypes

In this study, we reanalyzed the publicly available human embryonic skeletal snRNA-seq data36, human embryonic pituitary scRNA-seq dataset35 and adult human brain snRNA-seq dataset34, retaining the major tissues and cell types as defined in the original study. We used scDRS (v1.0.2) to link the scRNA-seq data with polygenic risk at a single-cell resolution, independent of cell type. For each type of HBR, polygenic scores were computed based on GWAS z-scores and scRNA-seq expression values. Cell-specific association p-values were determined by comparing the normalized disease scores to an empirical distribution of normalized scores generated from all control gene sets across all cells. We retained HBR phenotype–cell type associations with “assoc mcp” values less than 0.05 in each tissue.

Enrichment analysis for regions of evolutionary context

The conserved regions in the bird genome38 were converted to the hg19 reference genome using the UCSC liftOver tool, and the intersecting regions with mammalian conserved regions were identified. We extracted the intersection of alignments between five species of reptiles or amphibians and the human genome from the NCBI Comparative Genome Viewer. These genomic regions in reptiles were then marked within the shared conserved regions between birds and mammals. All other evolutionary genomic annotations were derived from Kun et al.14,97. Additionally, as a control for HAR enrichment, we selected the psychiatric disorders mentioned earlier and performed the same enrichment permutation experiment on the significant loci.

We then used SNPsnap98 to assess the enrichment of each HBR-associated SNP based on MAF, the number of SNPs in LD under different LD thresholds, distance to the nearest gene, and gene density, using 1000 sets of null-matched SNPs for comparison (p < 5 × 10−8). We extended the 500 bp upstream and downstream regions of both HBR SNPs and a random set of null-matched SNPs, respectively, to calculate their intersections with the annotation regions. The number of hits where the matched SNPs had equal or greater hits than the HBR SNPs was counted, and the ratio of this number to the number of random iterations was used as the p-value for the one-sided permutation test. The odds ratio was calculated as median value of the permutation tests. Finally, all p-values for HBRs and genomic annotations were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the BH correction method.

Phenotypic association of HBR with common diseases

We defined disease based on the annotation information in diagnoses of ICD-10 (Field 41270) in UKBB. In diagnoses of ICD10, diseases are categorized into different classes. We selected 46 common diseases from five categories: psychiatric, neurological, musculoskeletal system, circulatory system, and metabolic system. The selection was performed at the second hierarchical level of the ICD-10 structure (three-character codes), except for Pian. Only common diseases with more than 1000 cases in the cohort were included in our analyses. Patients received a “1” if a disease code appeared in their hospital records, and a “0” otherwise. The ICD-10 code and details for the diseases used in our study are shown in Supplementary Data 21. We counted the number of samples for each disease, used sex, age, imaging equipment, image background and first 10 principal components as covariates, performed logistic regression using the logistic regression method “Logit” of the statsmodels99 python library, calculated the exponent of the coefficients to get the odds ratio, and used the BH method to correct the p-value of the regressions.

Polygenic risk score analyses and logistic regression

We utilized PRS-CS50 to construct polygenic risk score (PRS) prediction models. PRS-CS is a command-line tool based on Python that uses GWAS summary statistics and external LD reference panels to infer the posterior effect sizes of SNPs under a continuous shrinkage prior. In our model, we incorporated 1,117,425 SNPs from HapMap3 and performed clumping using PLINK2-clump with parameters “r2 = 0.01” and “kb=250”. For the reference LD panel, we used the 1000 Genomes (1000 G) data for the European population. The output from PRS-CS includes the chromosome, rs ID, base position, A1, A2, and posterior effect size estimates for each SNP. We concatenated the output files for all chromosomes and then used the PLINK2 --score command to calculate the PRS for all genotyped non-imaged individuals of white British ancestry (who had also undergone genetic QC), with a sample size of 315,404 participants after excluding related individuals. We subsequently performed logistic regression for 46 manually selected diseases using the same method as for the phenotypic logistic regression, based on the polygenic scores.

Mendelian randomization

We collected summary statistics of GWAS for 46 diseases across five categories from several sources, including FinnGen (release R11)100, Million Veteran Program (MVP)101, the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium studies (PGC)102 and Social Science Genetic Association Consortium103. For diseases with multiple available summary statistics, the dataset with the largest effective sample size was selected for our analysis (Supplementary Data 21). We investigated the causal association between these diseases and HBRs using two-sample Mendelian randomization.

We first selected independent SNPs for each exposure (r2 = 0.001, window size = 1 Mb, and p < 5 × 10−8) using the clustering algorithm in PLINK2. The 1000 G European data were used as a reference for LD estimation. For the IVs, three key assumptions must hold: 1) the selected IVs must be associated with the exposure (relevance assumption); 2) the selected IVs are not associated with potential confounders (independence assumption), and 3) the IVs affect the outcome only through their effect on the exposure (exclusion restriction assumption). We used RadialMR104 package to remove pleiotropic SNPs. The remaining SNPs were used to perform MR analysis. We used MR Steiger filtering to check whether the MR analysis estimates assessed the true causal direction105. We performed MR testing using the “mr_ivw” method with the TwoSampleMR106 R package, followed by BH correction for all MR test results.

For the significant MR results, we performed a further sensitivity analysis. First, we performed leave-one-out analysis to check whether the causal association was obviously driven by a single SNP (p-value < 0.05 was regarded as an outlier). Second, we conducted MR-PRESSO107 to detect the presence of horizontal pleiotropy (p-value < 0.05). Third, we executed MR-Egger regression to examine the potential bias of directional pleiotropy. The intercept in the Egger regression indicates the mean pleiotropic effect of all genetic variants, which is interpreted as evidence of directional pleiotropy when the value differs from zero (p-value < 0.05). Cochran’s Q and Rucker’s Qʹ statistics were also calculated to check for the presence of heterogeneity for the Inverse-Variance Weighted and MR-Egger method, respectively.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data from UK Biobank used in this study are available through a procedure described at: https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research. All public data sources are cited in the corresponding sections of the Methods. The GWAS summary statistics used in the MR analysis can be obtained from the URLs listed in Supplementary Data 21. The GWAS summary data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database under accession code 14835684 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17421944108 and GWAS Catalog database under accession IDs GCST90702447-GCST90702456 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/).

Code availability

The codes used for quality control of the DXA images and for performing deep learning-based segmentation of the head and key landmarks are available at https://github.com/weishaoxia/head-body-ratio and archived at Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17422184109. We carried out all deep learning using the Python programming language (v3.9.23) with the PyTorch (v2.7.1+cu128) and cv2 (v4.12.0) libraries on NVIDIA RTX 5090 GPUs on the CentOS Linux system the CUDA (v12.8) toolkit.

References

Jerison, H. J. Evolution of the brain and intelligence: Comment on radinsky’s review. Evolution 30, 186–187 (1976).

Striedter, G. F. Precis of principles of brain evolution. Behav. Brain Sci. 29, 12–36 (2006).

Miller, I. F., Barton, R. A. & Nunn, C. L. Quantitative uniqueness of human brain evolution revealed through phylogenetic comparative analysis. Elife 8, e41250 (2019).

Venditti, C., Baker, J. & Barton, R. A. Co-evolutionary dynamics of mammalian brain and body size. Nat. Ecol. Evolution 8, 1534–1542 (2024).

Isler, K. & Van Schaik, C. P. How humans evolved large brains: comparative evidence. Evolut. Anthropol.: Issues, N., Rev. 23, 65–75 (2014).

Lainhart, J. E. et al. Head circumference and height in autism: a study by the collaborative program of excellence in autism. Am. J. Med Genet A 140, 2257–2274 (2006).

Sacco, R., Gabriele, S. & Persico, A. M. Head circumference and brain size in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 234, 239–251 (2015).

Knol, M. J. et al. Genetic variants for head size share genes and pathways with cancer. Cell Rep. Med 5, 101529 (2024).

Will, M., Krapp, M., Stock, J. T. & Manica, A. Different environmental variables predict body and brain size evolution in Homo. Nat. Commun. 12, 4116 (2021).

Lango Allen, H. et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature 467, 832–838 (2010).

Yengo, L. et al. A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature 610, 704–712 (2022).

Currant, H. et al. Correction: Genetic variation affects morphological retinal phenotypes extracted from UK Biobank optical coherence tomography images. PLoS Genet 17, e1009858 (2021).

Agrawal, S. et al. BMI-adjusted adipose tissue volumes exhibit depot-specific and divergent associations with cardiometabolic diseases. Nat. Commun. 14, 266 (2023).

Kun, E. et al. The genetic architecture and evolution of the human skeletal form. Science 381, eadf8009 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. The genetic architecture of and evolutionary constraints on the human pelvic form. Science 388, eadq1521 (2025).

Bai, W. et al. A population-based phenome-wide association study of cardiac and aortic structure and function. Nat. Med 26, 1654–1662 (2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 770-778 (IEEE, 2016).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015 (eds Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W. & Frangi, A.) 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Bulik-Sullivan, B. K. et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet 47, 291–295 (2015).

Benner, C. et al. FINEMAP: efficient variable selection using summary data from genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 32, 1493–1501 (2016).

Wang, K., Li, M. & Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 38, e164 (2010).

Zhou, D. et al. A unified framework for joint-tissue transcriptome-wide association and mendelian randomization analysis. Nat. Genet 52, 1239–1246 (2020).

Giambartolomei, C. et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004383 (2014).

Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76–82 (2011).

Zheng, H.-F. et al. WNT16 influences bone mineral density, cortical bone thickness, bone strength, and osteoporotic fracture risk. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002745 (2012).

Wainberg, M. et al. Genetic architecture of the structural connectome. Nat. Commun. 15, 1962 (2024).

Smith, S. M. et al. An expanded set of genome-wide association studies of brain imaging phenotypes in UK Biobank. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 737–745 (2021).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat. Genet 25, 25–29 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Tanabe, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic acids Res. 45, D353–D361 (2017).

Bergan-Roller, H. E. & Sheridan, M. A. The growth hormone signaling system: Insights into coordinating the anabolic and catabolic actions of growth hormone. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 258, 119–133 (2018).

Shen-Orr, S. S. et al. Defective signaling in the JAK-STAT pathway tracks with chronic inflammation and cardiovascular risk in aging humans. Cell Syst. 3, 374–384. e374 (2016).

Hayamizu, T. F., Mangan, M., Corradi, J. P., Kadin, J. A. & Ringwald, M. The Adult Mouse Anatomical Dictionary: a tool for annotating and integrating data. Genome Biol. 6, 1–8 (2005).

Zhang, M. J. et al. Polygenic enrichment distinguishes disease associations of individual cells in single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat. Genet 54, 1572–1580 (2022).

Siletti, K. et al. Transcriptomic diversity of cell types across the adult human brain. Science 382, eadd7046 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics identifies divergent developmental lineage trajectories during human pituitary development. Nat. Commun. 11, 5275 (2020).

To, K. et al. A multi-omic atlas of human embryonic skeletal development. Nature 635, 657–667 (2024).

Olkowicz, S. et al. Birds have primate-like numbers of neurons in the forebrain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 7255–7260 (2016).

Zhang, G. et al. Comparative genomics reveals insights into avian genome evolution and adaptation. Science 346, 1311–1320 (2014).

Oishi, T. [Species Differences in the Brain between Human and Non-Human Primates]. Brain Nerve 71, 807–813 (2019).

Doan, R. N. et al. Mutations in human accelerated regions disrupt cognition and social behavior. Cell 167, 341–354. e312 (2016).

Reilly, S. K. et al. Evolutionary genomics. Evolutionary changes in promoter and enhancer activity during human corticogenesis. Science 347, 1155–1159 (2015).

Vermunt, M. W. et al. Epigenomic annotation of gene regulatory alterations during evolution of the primate brain. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 494–503 (2016).

Vernot, B. et al. Excavating neandertal and denisovan DNA from the genomes of melanesian individuals. Science 352, 235–239 (2016).

Jones, G. H. & Lewis, J. E. Head circumference in elderly long-stay patients with schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 159, 435–438 (1991).

Ward, K. E., Friedman, L., Wise, A. & Schulz, S. C. Meta-analysis of brain and cranial size in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res. 22, 197–213 (1996).

Williams, C. A., Dagli, A. & Battaglia, A. Genetic disorders associated with macrocephaly. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 146, 2023–2037 (2008).

Bucher, H., Prader, A. & Illig, R. Head circumference, height, bone age and weight in 103 children with congenital hypothyroidism before and during thyroid hormone replacement. Helvetica paediatrica acta 40, 305–316 (1985).

Renaud, D. L. Leukoencephalopathies associated with macrocephaly. Semin Neurol. 32, 34–41 (2012).

Stefansdottir, H. et al. Atrial fibrillation is associated with reduced brain volume and cognitive function independent of cerebral infarcts. Stroke 44, 1020–1025 (2013).

Ge, T., Chen, C. Y., Ni, Y., Feng, Y. A. & Smoller, J. W. Polygenic prediction via bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nat. Commun. 10, 1776 (2019).

Maeda, Y. et al. Functional deficits in carpal tunnel syndrome reflect reorganization of primary somatosensory cortex. Brain 137, 1741–1752 (2014).

Maeda, Y. et al. Altered brain morphometry in carpal tunnel syndrome is associated with median nerve pathology. Neuroimage Clin. 2, 313–319 (2013).

Kappelman, J. The evolution of body mass and relative brain size in fossil hominids. J. Hum. evolution 30, 243–276 (1996).

Grabowski, M. Bigger brains led to bigger bodies? The correlated evolution of human brain and body size. Curr. Anthropol. 57, 174–196 (2016).

Chaste, P. et al. Adjusting head circumference for covariates in autism: clinical correlates of a highly heritable continuous trait. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 576–584 (2013).

Yengo, L. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in approximately 700000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum. Mol. Genet 27, 3641–3649 (2018).

Muslin, A. J. MAPK signalling in cardiovascular health and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Clin. Sci. 115, 203–218 (2008).

Grimaud, E., Heymann, D. & Rédini, F. Recent advances in TGF-β effects on chondrocyte metabolism: potential therapeutic roles of TGF-β in cartilage disorders. Cytokine growth factor Rev. 13, 241–257 (2002).

Ansari, M. D., Majid, H., Khan, A. & Sultana, Y. Clinical frontiers of metabolic bone disorders: a comprehensive review. Metab. Target Organ Damage 4, 2 (2023).

Ntali, G., Markussis, V. & Chrisoulidou, A. An overview of cardiovascular risk in pituitary disorders. Medicina 60, 1241 (2024).

Burford, N. G., Webster, N. A. & Cruz-Topete, D. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis modulation of glucocorticoids in the cardiovascular system. Int J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2150 (2017).

Schernthaner-Reiter, M. H., Wolf, P., Vila, G. & Luger, A. The interaction of insulin and pituitary hormone syndromes. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 626427 (2021).

Chrousos, G. P. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med 332, 1351–1363 (1995).

Zhou, B., Zhu, Z., Ransom, B. R. & Tong, X. Oligodendrocyte lineage cells and depression. Mol. psychiatry 26, 103–117 (2021).

Liu, S.-H., Du, Y., Chen, L. & Cheng, Y. Glial cell abnormalities in major psychiatric diseases: A systematic review of postmortem brain studies. Mol. Neurobiol. 59, 1665–1692 (2022).

Galvez-Contreras, A. Y., Zarate-Lopez, D., Torres-Chavez, A. L. & Gonzalez-Perez, O. Role of oligodendrocytes and myelin in the pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorder. Brain Sci. 10, 951 (2020).

Spaas, J. et al. Oxidative stress and impaired oligodendrocyte precursor cell differentiation in neurological disorders. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78, 4615–4637 (2021).

Ono, N., Balani, D. H. & Kronenberg, H. M. Stem and progenitor cells in skeletal development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 133, 1–24 (2019).

Totoson, P., Maguin-Gate, K., Prati, C., Wendling, D. & Demougeot, C. Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis: lessons from animal studies. Arthritis Res Ther. 16, 202 (2014).

Nelson, C. P. et al. Genetically determined height and coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med 372, 1608–1618 (2015).

Chen, Y., Yu, Z., Packham, J. C. & Mattey, D. L. Influence of adult height on rheumatoid arthritis: association with disease activity, impairment of joint function and overall disability. Plos One 8, e64862 (2013).

Lawlor, D., Ebrahim, S. & Davey Smith, G. The association between components of adult height and Type II diabetes and insulin resistance: British women’s heart and health study. Diabetologia 45, 1097–1106 (2002).

Schofield, P. W., Logroscino, G., Andrews, H. F., Albert, S. & Stern, Y. An association between head circumference and alzheimer’s disease in a population-based study of aging and dementia. Neurology 49, 30–37 (1997).

Borenstein Graves, A. et al. Head circumference and incident alzheimer’s disease: Modification by apolipoprotein E. Neurology 57, 1453–1460 (2001).

Perneczky, R. et al. Head circumference, atrophy, and cognition: implications for brain reserve in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 75, 137–142 (2010).

Kwon, O. D., Choi, S.-Y. & Bae, J. Association of head circumference with cognitive decline and symptoms of depression in elderly: a 3-year prospective study. Yeungnam Univ. J. Med. 35, 205–212 (2018).

Emery, N. J. & Clayton, N. S. The mentality of crows: convergent evolution of intelligence in corvids and apes. Science 306, 1903–1907 (2004).

Audet, J.-N., Couture, M. & Jarvis, E. D. Songbird species that display more-complex vocal learning are better problem-solvers and have larger brains. Science 381, 1170–1175 (2023).

Koteja, P. The evolution of concepts on the evolution of endothermy in birds and mammals. Physiological biochemical Zool. 77, 1043–1050 (2004).

Neubauer, S., Hublin, J. J. & Gunz, P. The evolution of modern human brain shape. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao5961 (2018).

Bramble, D. M. & Lieberman, D. E. Endurance running and the evolution of Homo. Nature 432, 345–352 (2004).

Lacruz, R. S. et al. The evolutionary history of the human face. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 726–736 (2019).

Grabowski, M., Hatala, K. G., Jungers, W. L. & Richmond, B. G. Body mass estimates of hominin fossils and the evolution of human body size. J. Hum. Evol. 85, 75–93 (2015).

Bogin, B. & Varela-Silva, M. I. Leg length, body proportion, and health: a review with a note on beauty. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 7, 1047–1075 (2010).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Dong, Y., Pan, Y., Zhang, J. & Xu, W. Learning to read chest X-ray images from 16000+ examples using CNN. In 2017 IEEE/ACM international conference on connected health: applications, systems and engineering technologies (CHASE) 51-57 (IEEE, 2017).

Rajpurkar, P. et al. Deep learning for chest radiograph diagnosis: A retrospective comparison of the CheXNeXt algorithm to practicing radiologists. PLoS Med. 15, e1002686 (2018).

Mason, D. SU-E-T-33: pydicom: an open source DICOM library. Med. Phys. 38, 3493–3493 (2011).

Marcel, S. & Rodriguez, Y. Torchvision the machine-vision package of torch. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Multimedia 1485-1488 (ACM, 2010).

Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor. Dent. Endod. 42, 152 (2017).

Goulet-Pelletier, J.-C. & Cousineau, D. A review of effect sizes and their confidence intervals, Part I: The Cohen’sd family. Quant. Methods Psychol. 14, 242–265 (2018).

Russell, B. C., Torralba, A., Murphy, K. P. & Freeman, W. T. LabelMe: a database and web-based tool for image annotation. Int. J. computer Vis. 77, 157–173 (2008).

Chang, C. C. et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4, 7 (2015).

Loh, P. R. et al. Efficient Bayesian mixed-model analysis increases association power in large cohorts. Nat. Genet 47, 284–290 (2015).

Consortium, G. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369, 1318–1330 (2020).

Yu, G., Wang, L.-G., Han, Y. & He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics: a J. Integr. Biol. 16, 284–287 (2012).

Kun, E., Sohail, M. & Narasimhan, V. M. The trait-specific timing of accelerated genomic change in the human lineage. Cell Genomics 5, 10.1016/j.xgen.2024.100740 (2025).

Pers, T. H., Timshel, P. & Hirschhorn, J. N. SNPsnap: a Web-based tool for identification and annotation of matched SNPs. Bioinformatics 31, 418–420 (2015).

Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. Statsmodels: econometric and statistical modeling with python. SciPy 7, https://www.statsmodels.org/stable/index.html (2010).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 613, 508–518 (2023).

Verma, A. et al. Diversity and scale: Genetic architecture of 2068 traits in the VA Million Veteran Program. Science 385, eadj1182 (2024).

Sullivan, P. F. et al. Psychiatric genomics: an update and an agenda. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 15–27 (2018).

Lee, J. J. et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a 1.1-million-person GWAS of educational attainment. Nat. Genet. 50, 1112 (2018).

Bowden, J. et al. Improving the visualization, interpretation and analysis of two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization via the Radial plot and Radial regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47, 1264–1278 (2018).