Abstract

Combining immunotherapy with chemoradiation is effective in locally advanced cervical cancer. However, the impact of induction combination immunotherapy on immune modulation and treatment response is poorly understood. In this phase II trial (NCT04256213), 40 females with locally advanced cervical carcinoma received one cycle of nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab immunotherapy before standard chemoradiation, followed by maintenance nivolumab. We show, using multiplex-immunofluorescence tissue imaging, a significantly increased CD8+/FOXP3+ cell ratio (primary endpoint; increase of 0.87 cells/mm², P = 0.0164) and proliferative CD8+ T-cell density after one cycle of combination immunotherapy. HOT score (27-gene-based signature identifying immunologically active tumors) also increased significantly (exploratory analysis; 0.17, P < 0.0001). Objective response rates (secondary endpoint) were 13% immediately after combination immunotherapy, 98% (65% complete response) after chemoradiation, and 90% at treatment completion. High HOT score at baseline and immune changes induced by combination immunotherapy were associated with complete response at treatment completion. Induction immunotherapy may prime tumors for improved response to standard therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cisplatin-based chemoradiation is the standard of care for locally advanced cervical cancer (LACC). However, up to 30% of patients with high-risk LACC experience recurrence within 2 years, cure is rare, and improved treatment for LACC remains an area of unmet need. Established prognostic factors include International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, pathologic tumor type, nodal status, and lymphovascular space invasion1. Outcomes in patients with pelvic and para-aortic lymph node metastases are particularly poor.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy modulates the immune microenvironment in LACC, promoting anti-cancer immunity by increasing tumor-infiltrating effector lymphocytes (CD8+ Teffs) at the expense of regulatory T cells (forkhead box P3 [FOXP3]+ Tregs)2. Indeed, a high tumor CD8+/FOXP3+ cell ratio, as assessed by immunohistochemistry, was associated with better clinical outcomes after platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in a retrospective study of patients with LACC2.

Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) combined with chemotherapy is the standard first-line treatment for recurrent, persistent, or metastatic cervical cancer. Randomized phase III trials have demonstrated an overall survival (OS) benefit with the addition of either pembrolizumab (KEYNOTE-826) or atezolizumab (BeatCC) to chemotherapy (with or without bevacizumab)3,4,5. In high-risk LACC, the phase III CALLA trial failed to demonstrate a significant progression-free survival (PFS) benefit from durvalumab given in combination with and following chemoradiotherapy6. However, pembrolizumab significantly improved PFS and OS when combined with chemoradiation for high-risk LACC in the ENGOT-cx11/GOG-3047/KEYNOTE-A18 trial7,8. A better understanding of the impact of ICB on the tumor microenvironment will help in refining immunotherapy approaches and patient selection with the goal of improving clinical outcomes.

When immunotherapy is given before local therapy (surgery or radiotherapy), the presence of the tumor in situ provides a source of antigens that may favor potent reinvigoration of tumor-specific T cells with ICB. In several cancer types, accumulating evidence indicates that neoadjuvant immunotherapy may expand tumor-specific T-cell clones and modify their transcriptional features9. This can lead to a more robust anti-tumor immune response and a greater number of functional effector T cells (Teffs) able to recirculate and ready to fight cancer cells, even after local therapy10. The neoadjuvant setting also provides a unique opportunity to elucidate the impact of immunotherapy on the tumor immune microenvironment in LACC. In the phase I GOG-9929 study, chemoradiation followed by two doses of the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor ipilimumab for node-positive human papillomavirus (HPV)-related LACC was associated with activation of immune cells in blood, and a significant expansion of central and effector memory T-cell populations11. However, in this study, the impact of immunotherapy alone before chemotherapy was not investigated.

High CTLA-4 transcript expression is common in cervical cancer and correlates significantly with high PD-1 RNA levels12. Co-expression of PD-1 and CTLA-4 is associated with more severe dysfunction of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells13. In in vivo models, dual PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockade reversed tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte dysfunction, increased proliferation of CD8+ and CD4+ Teffs, and depleted Tregs in tumors13. In another study, high-dimensional single-cell profiling demonstrated that dual PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockade elicited distinct cellular responses, including expansion of activated CD8+ Teffs14. Finally, promising and durable clinical activity, coupled with favorable tolerability, was seen in the largest trial to date evaluating dual PD-1/CTLA-4 blockade in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic cervical cancer15. In the window-of-opportunity COLIBRI study, we explored the effect of ICB on the tumor immune microenvironment, aiming to understand how dual PD-1/CTLA-4 blockade affects the T-cell immune infiltrate in cervical cancer and how sequencing ICB before and after chemoradiotherapy affects the immune response and anti-tumor efficacy (Fig. 1).

Iconographies (cells, antibodies, blood tubes, uterus) adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com), licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Servier Medical C cycle, D day, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, EOT end of treatment, FIGO International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, LACC locally advanced cervical cancer, q4w every 4 weeks, RTCT chemoradiation (comprising cisplatin 40 mg/m2 or carboplatin AUC2 every week for 5 weeks, external beam radiotherapy 45 Gy in 25 fractions at 1.8 Gy/fraction, 5 fractions per week, and brachytherapy [high-dose rate: 27.5–30 Gy; low/pulsed-dose rate: 35–40 Gy]). aOptional cervical tumor sample during surgery. bMandatory blood sample and optional biopsy at progression.

Results

Patient population and treatment exposure

Forty female patients were enrolled from sites in France with gynecologic oncology expertise between June 28, 2020, and August 4, 2021. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median duration of follow-up was 95 (95% confidence interval [CI] 73–114) weeks. Tumor samples were collected before immune treatment and before chemoradiation from 39 patients (98%) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thirteen patients (33%) refused biopsy after chemoradiotherapy because of procedure-associated pain.

All 40 patients received neoadjuvant nivolumab and ipilimumab. Only one patient (3%) required dose modification (temporary nivolumab interruption because of treatment-related pruritic rash). During chemoradiotherapy, 39 patients (98%) received cisplatin and three (8%) received carboplatin (Supplementary Table 1). Chemotherapy was interrupted for toxicity in six patients (15%). External beam radiotherapy was delivered per protocol in all 40 patients (median duration 36 days, range 32–71 days) and brachytherapy was delivered in 36 patients (90%) (Supplementary Table 1). All but one patient (39; 98%) received all radiotherapy within ≤55 days and started maintenance nivolumab. In the maintenance phase, 34 patients (85%) completed all six cycles of nivolumab. Reasons for discontinuing maintenance therapy before cycle 6 were disease progression (PD; two patients) and adverse events (AEs), AE/non-compliant concomitant medication, and patient decision (each in one patient). Four patients (10%) underwent optional surgery before starting maintenance therapy.

Biomarker analysis

At baseline (before ICB), multiplex-immunofluorescence (mIF) and high-throughput genomic (HTG) sequencing were each evaluable in 39 patients. After ICB (before chemoradiation), mIF and HTG were evaluable in 32 and 37 patients, respectively. Among patients evaluable for the primary study endpoint, paired samples (pre- and post-ICB before chemoradiation) were available for mIF and HTG analysis from 31 and 37 patients, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). Figure 2A shows representative images of mIF staining at baseline and after ICB, revealing an increase in total and proliferating CD8+ T cells. Quantitative digital image analysis revealed significantly increased CD4+ (P = 0.0091) and CD8+ (P = 0.0132) Teffs post-ICB (before chemoradiation) and more variable effects on Tregs (CD3+FOXP3+) (P = 0.0903) and B cells (CD20+, P > 0.5), resulting in higher ratios of CD8+/FOXP3+ (P = 0.0164), but not CD4+/FOXP3+ (P > 0.5) cells (Fig. 2B).

A Digital mIF images of tumor collected at baseline vs before chemoradiation from a representative patient. The white arrows indicate Ki67 and CD8 double-positive cells (i.e., proliferating CD8+ Teffs). B Graphs depicting densities (number of cells per mm2) of various immune populations quantified from mIF-stained tumors collected from 31 patients at BL versus BEF (i.e., after ipilimumab + nivolumab). Ratios between selected immune cell densities are also shown. Each dot represents a tumor sample and lines depict paired BL versus BEF samples. A two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine statistical significance and unadjusted P-values are indicated. C The gene expression-based HOT score was compared in paired BL versus BEF samples within patients after immunotherapy using the statistics as for (B). D Sankey diagram showing the transition of patients’ HOT status (HOT or COLD) from BL to BEF; the width of each ribbon is proportional to the number of patients in the corresponding transition. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. BEF before chemoradiation, BL baseline, CK cytokeratin, mIF multiplex-immunofluorescence, HTG high-throughput genomic, Teff effector T cells, Treg regulatory T cells.

In most patients, ICB drastically increased proliferative (Ki67+) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (both P < 0.0001) and the ratio of proliferative CD8+ Teffs to Tregs (P < 0.0001). Dynamic changes in all evaluable immune parameters between paired pre- and post-ICB samples are shown in Fig. 3.

Graph depicting the –log10(P) values for all measured immune parameters between BL and BEF paired tumor samples (n = 31 patients). Blue bars represent parameters that decreased after ICB and red bars represent parameters that increased after ICB. A two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine statistical significance, and unadjusted P-values are indicated. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. BEF before chemoradiation, BL baseline, ICB immune checkpoint blockade, Teff effector T cells, Treg regulatory T cells.

In exploratory analyses, the HTG HOT score (a 27-gene-based signature identifying immunologically active tumors) increased significantly (P < 0.0001) after dual ICB (Fig. 2C). At baseline, only 10 (26%) of 39 evaluable samples were classified as HOT compared with 22 (56%) after ICB (Fig. 2D).

Subgroup analyses are limited by small patient numbers, but the baseline CD8+ Teff/Treg ratio appeared to be higher in patients with FIGO stage III/IV than stage I/II disease and this appears to be largely driven by lower Treg levels (Fig. 4). There were no differences in other immune parameters at baseline, including HOT score, according to FIGO stage.

The 39 patients with mIF data at baseline were classified according to FIGO stage into FIGO I/II (n = 21) and FIGO III/IV (n = 18). A Graph depicting the P-values of selected tumor immune parameters between the two groups at baseline (Mann–Whitney U tests). B Boxplots of selected immune cell parameters. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. FIGO International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, mIF multiplex-immunofluorescence, Teff T effector cells, Treg regulatory T cells.

Clinical response and correlation with biomarkers

By the data extraction date (February 11, 2023), six patients (15%) had experienced PD (of whom four [10%] had died).

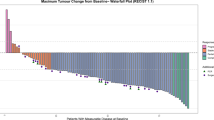

The global objective response rate was 13% (95% CI 4–27%, with a further 83% of patients experiencing stable disease) after ICB within 1 week before chemoradiation. The objective response rate was 98% (95% CI 87–100%; complete response [CR] in 65%, partial response [PR] in 33%) 4 weeks after chemoradiation, and 90% (95% CI 76–97%; CR in 78%, PR in 13%) at the end-of-treatment visit (Table 2). Both patients with PD before chemoradiation had a PR after chemoradiation, with no evidence of PD during follow-up until the data cutoff.

Heatmaps showed that several immune parameters measured at baseline or before chemoradiation significantly differed between patients classified according to their response to treatment, assessed either before chemoradiation or at the end of treatment (Fig. 5A, B and Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Although few patients showed a PR before chemoradiation, most of them displayed high lymphocyte infiltration at baseline (Fig. 5A). Indeed, compared with non-PR patients, this group showed a tendency for higher baseline infiltration by CD8+ T cells and displayed significantly higher ratios of total CD8+ Teff/FOXP3+ Treg (P = 0.0011), proliferating CD8+ Teff/FOXP3+ Treg (P = 0.0001), and proliferating CD4+ Teff/FOXP3+ Treg (P = 0.0087) (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. 2c). When considering the response at the end of maintenance therapy, only two baseline parameters were associated with CR: CD4+ density and, to a lesser (non-significant) extent, CD8+ Teffs (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. 2b). In contrast, total and proliferating CD8+ T cells, proliferating CD4+ T cells and CD20+ B cells, and the ratio of proliferative CD8+ Teff/FOXP3+ Tregs before chemoradiation (i.e., after dual ICB) correlated significantly with CR at the end of maintenance therapy (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. 2c). A similar (non-significant) tendency was seen for the CD8+ Teff/FOXP3+ Treg ratio (Fig. 5C). In contrast, none of the four patients with PD during treatment showed any significant change in CD8+ Teffs infiltrate or CD8+ Teff/FOXP3+ Treg ratio, nor did we observe changes in their HOT/COLD status after dual ICB (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Similar comparisons according to the HOT score showed a significant relationship between elevated HOT score at baseline and CR at the end of maintenance treatment (Fig. 5D). Graphs depicting the P-values for all measured immune parameters obtained by univariate analysis are shown in Fig. 6. Tertiary lymphoid structures with segregated T- and B-cell zones were detected in very few patients (5/39 at baseline and 3/32 after ICB, Supplementary Fig. 3), preventing evaluation of their relationship with clinical response. To explore further the relationship between treatment-induced immune changes and clinical response, we constructed a multivariate longitudinal linear model adjusted on the immune values measured at baseline to control for baseline differences between patients. This analysis revealed that CR at the end of maintenance treatment correlated with high densities of total and proliferating CD8+ Teff and, to a lesser extent, proliferating CD4+ Teff (Table 3). CR at the end of maintenance treatment also correlated with high proliferative CD8+ Teff/Treg ratios measured before chemoradiation (i.e., immediately after neoadjuvant ICB). The relationship between PR before chemoradiation and high proliferating CD8+ Teff density and CD8+ Teff/Treg ratio bordered on statistical significance.

A, B Heatmaps showing immune parameters (A) in baseline samples (before ICB) according to response evaluated before chemoradiation: non-PR (n = 5) and PR (n = 35) and (B) in samples after ICB (before chemoradiation) according to response at treatment completion: CR (n = 31) and non-CR (n = 9). Each column represents a patient and each row an immune parameter; cell color denotes the Z-score. Within each response group, patients were sorted left to right by decreasing CD8+ Teff density. Group differences for each immune parameter (A non-PR vs PR; B CR vs non-CR) were assessed using the two-sided Mann–Whitney U test and non-adjusted P-values are shown. C, D Graphs depicting the association between selected immune parameters quantified by (C) mIF or (D) HTG HOT score from samples collected at BL (upper graphs) or before RTCT (lower graphs) and response to treatment. Patients were stratified by clinical response before RTCT (non-PR vs PR, left graphs) or at EOT (non-CR vs CR, right graphs). Each dot represents a patient measured once at the indicated timepoint (biological replicates only; no technical replicates). Statistical differences between groups were tested using the two-sided Mann–Whitney U test with no adjustment for multiple comparisons. No separate control group was used as comparisons were performed between response-defined groups within the same cohort. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. BEF before chemoradiation, BL baseline, CR complete response, EOT end of treatment, HTG high-throughput genomic, ICB immune checkpoint blockade, mIF multiplex-immunofluorescence, PD disease progression, PR partial response, RTCT chemoradiation, SD stable disease, Teff effector T cells, Treg regulatory T cells.

Group differences for each immune parameter (A non-PR vs PR for response before RTCT; B non-CR vs CR for response after RTCT; C non-CR vs CR for response at EOT) were evaluated using the two-sided Mann–Whitney U test with no adjustment for multiple comparisons. Graphs depicting –log10(P-values) of the immune parameters between the two groups (A non-PR vs PR; B non-CR vs CR; C non-CR vs CR) are shown. Sample sizes are presented in each panel. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. BL baseline, CR complete response, EOT end of treatment, PR partial response, RTCT chemoradiation, Teff T effector cells, Treg regulatory T cells.

Safety

Grade ≥2 AEs were reported in 14 (35%) patients during ICB, 33 (83%) during chemoradiation, and 17 (44%) during maintenance nivolumab (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 2). Grade ≥3 AEs were considered possibly related to ICB in one patient (3%) during induction ICB (grade 3 asthenia) and three patients (8%) during chemoradiation (grade 3 lymphopenia in two patients, grade 3 asthenia in one patient), and possibly related to nivolumab in five (13%) patients during maintenance therapy. There were no treatment-related deaths. The most common any-grade AEs were asthenia (28%; grade 1/2 in 25%) and pruritus (20%; all grade 1/2) during induction therapy; diarrhea (58%), nausea (53%), anemia (48%), asthenia (38%), and hypothyroidism (23%) during chemoradiation; and asthenia (26%; 23% grade 1/2) during maintenance nivolumab.

In exploratory analyses, we observed that, compared with patients who experienced grade ≤1 immune-related AEs, patients with grade 2/3 immune-related AEs showed significantly lower CD8+ Teff/Treg ratio in their tumor at baseline but quite similar individual densities of CD8+ Teff or total Treg cells (Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, a statistically significant increase in Tregs (total and proliferating) and proliferating B cells, and a decrease in proliferating CD4+ Teff/Treg ratio, was observed in samples collected after ICB before chemoradiation from patients with grade 2/3 immune-related AEs compared with patients who had only grade 1 or no immune-related AEs (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

The COLIBRI trial in LACC demonstrates the feasibility and tolerability of dual nivolumab plus ipilimumab ICB before chemoradiation followed by up to 6 months of maintenance nivolumab after chemoradiation. At treatment completion, responses were ongoing in 36 (90%) patients, suggesting no detrimental effect from sequencing ICB before chemoradiotherapy.

Analysis of immune parameters using mIF imaging and gene expression profiling (HTG sequencing) demonstrated a significant remodeling of the tumor microenvironment following ICB, including increased tumor infiltration by CD8+ cells, resulting in elevated CD8+/FOXP3+ cell ratios, and increased HOT gene expression score. Interestingly, a PR was observed after a single ICB dose in five patients, and was significantly associated with high baseline CD8+ Teff/Treg ratios, suggesting that early clinical benefit from dual ICB is linked to a pre-existing immune-active tumor microenvironment. The only baseline parameter significantly correlating with response after treatment completion was tumor infiltration by CD4+ T cells.

In a study in cervical cancer, neoadjuvant paclitaxel and cisplatin did not significantly modify tumor infiltration by CD8+ T cells2. However, in COLIBRI, a single cycle of ipilimumab and nivolumab triggered CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte proliferation and significantly increased CD8+ T cells at the expense of Tregs in most patients. Recent reports have described complex immune changes within the tumor microenvironment during neoadjuvant ICB (nivolumab/ipilimumab) with concurrent radiotherapy in other cancers, including advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinomas and non-small-cell lung cancer, and resectable melanoma16,17,18. In the single-arm phase II CLAP study, 45 patients with chemotherapy pre-treated advanced/metastatic cervical cancer (two-thirds squamous cell carcinoma, one-third adenocarcinoma) were treated with the anti-PD-1 antibody camrelizumab and the VEGFR-2 inhibitor apatinib19. Higher densities of CD8+ T cells in the tumor-invasive margin before treatment were associated with prolonged PFS (but not OS) in patients receiving combination therapy. However, in COLIBRI, pre-treatment CD8 density was less clearly associated with treatment response than in the CLAP trial.

Methodological limitations of the COLIBRI trial include the relatively small sample size, potentially limiting the reliability and generalizability of the findings, and the lack of a control arm, preventing assessment of the contribution of immunotherapy to treatment efficacy and safety. We found no evidence of increased toxicity or decreased acceptability compared with experience of chemoradiation alone in the EMBRACE-1 study20, but the single-arm design of COLIBRI prevents robust assessment of tolerability. Finally, enrollment of patients from a single country limits the generalizability of our results to countries with different clinical practices and healthcare environments.

The absence of ICB concurrently with chemoradiation may be seen as a limitation of the design, particularly given the recent positive results from the ENGOT-cx11/GOG-3047/KEYNOTE-A18 trial7,8, in which pembrolizumab was administered throughout chemoradiation and continued as maintenance therapy. However, no PFS difference between treatment arms was detected during the chemoradiation phase of KEYNOTE-A187 and the design does not allow disentanglement of the ICB contribution in combination with chemoradiation or in the maintenance phase21,22,23. The lack of induction chemotherapy before chemoradiation in COLIBRI may be criticized given recent results from the INTERLACE trial (also with some limitations), which demonstrated significantly improved PFS and OS in patients receiving 6 weeks of dose-dense paclitaxel and carboplatin induction chemotherapy before chemoradiation for LACC24. It would be interesting to explore whether observations from COLIBRI are replicated with dual ICB added to dose-dense chemotherapy. Nevertheless, the CD8+/FOXP3 ratio findings provide a robust foundation for further research on ICB sequencing in this setting. Although the sample size for the primary endpoint was smaller than planned because of technical issues, data were missing at random and missingness was not directly linked to patient characteristics. Consequently, there is likely to be minimal impact on estimation of the parameters of interest and the conclusions drawn.

Three additional recently reported trials evaluating immunotherapy and chemoradiation for cervical cancer deserve mention. In the NRG GY017 trial evaluating differential sequencing of atezolizumab (before or during chemoradiation) for high-risk cervical cancer, the likelihood of a complete pathologic response was increased in patients with a more diverse pre-treatment T-cell receptor repertoire25. However, most clonal expansion occurred in response to radiation rather than atezolizumab, and most of the expanded clones were absent in pre-treatment blood samples. In NRG GY017, the authors report on the tolerability of induction immunotherapy followed by chemoradiation and concurrent immunotherapy in 36 evaluable patients, of whom two experienced acute colitis and one thrombocytopenia. The single-arm NACI study demonstrated the feasibility and activity of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with camrelizumab, followed by radical surgery and/or chemoradiation depending on response to induction therapy26. Finally, cohort B of the GOTIC-018 trial included nivolumab before, during, and after chemoradiation for LACC but enrolled only 15 patients27 and, to date, no translational analyses have been reported.

A strength of the COLIBRI study is that the tumor microenvironment was evaluated both before and after dual ICB. The observed association between treatment-induced modulation of the immune microenvironment following ICB and clinical benefit provide proof of concept for induction dual ICB. Total and proliferating CD8+ Teff, proliferating CD4+ Teff, and Teff/Treg ratios measured after ICB (but not at baseline) were positively associated with response at the end of maintenance therapy. Insights from COLIBRI potentially pave the way for further improvements in combination regimens. Additional strengths include the high quality of chemoradiation and the integration of novel technologies (mIF) into the primary objective. Compared with conventional immunohistochemistry, multiplex technology reduces the quantity of tissue required, enhances the dimensionality of the analysis, and allows for evaluation of the cell-cell ecosystem and its impact on patient outcomes. These findings may also be relevant for new-generation ICB for cervical cancer, including bispecific antibodies28,29.

Ongoing analyses are evaluating the neighborhood of CD8+ and FOXP3+ immune cells and spatial localization of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages, and PD-L1 expression using mIF and immunohistochemistry. Additional analyses include gene expression profiles by RNA and whole-exome sequencing, and characterization of the phenotype and activation status of immune cells and anti-HPV T-cell responses using multiparametric flow cytometry and ELISA. Finally, associations between outcomes and HPV molecular status, integration sites, viral gene deletion, and HPV circulating tumor DNA kinetics will be characterized. Future research is warranted in larger cohorts of patients to improve the robustness and generalizability of findings from this window-of-opportunity study. Efforts should be taken to maximize the support provided to patients during biopsy to lessen the risk of missing data. Future research will include evaluation of the optimal duration of ICB as neoadjuvant chemotherapy, regimens combining PD-1 inhibition with novel agents (e.g., LAG3 inhibitors or other agents priming the immune response), the optimal duration of maintenance therapy in this setting, and the role of ICB for FIGO 2018 stage IIB disease not included in the current indication for pembrolizumab. Considerations for future trials potentially include exploration of ICB given concurrently with chemoradiation.

In conclusion, results from COLIBRI, combined with ongoing translational research, support further evaluation of neoadjuvant sequencing strategies for high-risk patients with LACC. The randomized phase II COLIBRI-2 trial (NCT06715241) is exploring nivolumab with or without the LAG3 inhibitor relatlimab as induction therapy before standard chemoradiation for LACC.

Methods

Study design

The multicenter single-arm phase II COLIBRI pilot study (GINECO-CE108b; NCT04256213) evaluated the immune impact and safety of a single cycle of nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy before primary chemoradiation for cervical cancer. The study was performed in accordance with ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice and applicable regulatory requirements. The final study protocol (available as a supplementary file) and informed consent form, including biomarker sample consents and any other patient materials, were approved by the national ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Est I; CPP EST I).

Objectives

The primary objective was to evaluate changes in the CD8+/FOXP3+ T-cell ratio in biopsies collected before versus after nivolumab and ipilimumab combination treatment before chemoradiation. The CD8+/FOXP3+ ratio was assessed by evaluating the composition of the immune infiltrate using seven-color spatial mIF.

Key secondary objectives included assessment of dynamic changes in the immune microenvironment (including CD8+, FOXP3+ Tregs, CD4+ T cells, and CD20+ B cells) before and after chemoradiation using mIF tissue imaging and HTG sequencing, clinical activity (including objective response rate according to RECIST version 1.1; by MRI and PET-CT if required) before and after chemoradiation (and at treatment completion as an exploratory objective), potential correlations between biologic changes in the tumor microenvironment and clinical activity, and tolerability.

Patients

Eligible patients had histologically confirmed squamous cell cervical carcinoma (FIGO 2018 stage IB3–IVA) for which standard-of-care chemoradiation was required as initial therapy. Patients had to be aged ≥18 years, with performance status 0 or 1, and adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function. All patients provided written informed consent before undergoing any study-specific procedure, and consented to collection of blood samples, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue, and fresh tumor biopsies for correlative studies. Patients were ineligible if they required neoadjuvant chemotherapy before chemoradiation, had previously received an immune checkpoint inhibitor, had any contraindication to nivolumab or ipilimumab, or had known or suspected uncontrolled CNS metastases, active, known or suspected autoimmune disease, or a history of chronic hepatitis.

Procedures

Patients were enrolled by investigators at participating centers and received a single cycle of intravenous ipilimumab 1 mg/kg on day 1 with nivolumab 3 mg/kg on days 1 and 15 before undergoing chemoradiation for 5–8 weeks per standard practice, with brachytherapy or external boost if brachytherapy was not feasible (Fig. 1). After chemoradiation, patients received maintenance nivolumab 480 mg every 28 days for 6 months. If required, residual disease was surgically resected 4–6 weeks after completing chemoradiation per local standards.

All patients underwent pelvic and abdominal MRI and PET-CT within 28 days before starting study treatment (with bone and CT scans if clinically indicated), and MRI within 1 week before and 4 weeks after chemoradiation. Tumor imaging was performed at the end of treatment visit for exploratory analysis of response rate. Cervical biopsies were mandatory before and after chemoradiation and optional during follow-up. AEs, graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03, were followed for 100 days after the last nivolumab dose or until starting another anti-cancer therapy. A data safety monitoring board reviewed each event that could modify the benefit:risk ratio. Patients were followed actively for approximately 12 months or until PD.

Clinical data were collected using the Clinsight v8.2.110 (Euraxi Pharma) clinical data management system, CSOnline v8.2.110 web interface (https://ecrf.euraxipharma.fr/CSOnline/), Oracle 11g back-end database, and MedDRA v21.1 and WHODrug Format C March 2017 for medical coding.

Translational methods

Seven-color mIF methods were similar to previous studies30,31 (Supplementary Methods). Targeted gene expression profiling of 2549 genes was performed using HTG sequencing to evaluate the 27-gene-based “HOT” score as a biomarker of immunologically active tumors. The HOT score evaluated the following genes: CCL19, CCR2, CCR4, CCR5, CD27, CD40LG, CD8A, CXCL10, CXCL11, CXCL13, CXCL9, CXCR3, CXCR6, FASLG, FGL2, GZMA, GZMH, IDO1, IFNG, IRF8, LAG3, LYZ, MS4A1, PDCD1, TBX21, TLR7, and TLR8. This signature has been validated as a prognostic marker in patients receiving first- or second-line anti-PD-(L)1 with or without chemotherapy for other tumor types17 and is computed using the Gene Set Variation Analysis to classify scores as positive (HOT) or negative (COLD).

Statistical analysis

It was planned to enroll 40 patients. Assuming a standard deviation of 14 units, this would provide a 95% CI with a precision of 5 units around the mean estimation of the CD8+/FOXP3+ relative change of lymphocytes between pre- and post-treatment biopsies. Paired pre- and post-treatment biopsies were compared using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests. The association between mIF and HTG data with tumoral response was assessed using Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney and Fisher exact tests. For each immune parameter and for each objective response timepoint (1 week before chemoradiation and end of treatment), a multivariate longitudinal linear model was performed to compare the immune responses between the overall tumoral responses (CR vs non-CR or PR vs non-PR). The models were adjusted on the baseline immune response level to control for initial differences between subjects. To consider repeated measurement by subject over time (biopsies performed at baseline and at 1 week before chemoradiation), the variance-covariance matrix used was compound-symmetry. The variances heterogeneity between groups was considered in the models. Adjusted means were calculated for the interaction between time effect and immune response, adjusting for baseline. Multiple comparisons were performed using Tukey–Kramer’s adjustment to control for type I error. P-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance in all tests. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), R version 4.1.1, and GraphPad Prism 9.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw and processed HTG data and metadata generated in this study have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE303300 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). For the remaining data, currently, no mechanism is in place to allow sharing of individual de-identified patient data. Requests to access the de-identified data for further scientific use can be sent to ARCAGY-GINECO (Sébastien Armanet, sarmanet@arcagy.org) and will be considered on a case-by-case basis in a timely manner beginning 3 months and ending 5 years after publication of this article, taking into consideration that some translational research is still ongoing. The request must contain a proposal with scientific and methodologically justified objectives. A data transfer agreement will be established to provide a formal framework regarding the use of the data. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Tantari, M. et al. Lymph node involvement in early-stage cervical cancer: is lymphangiogenesis a risk factor? Results from the MICROCOL study. Cancers 14, 212 (2022).

Liang, Y., Lü, W., Zhang, X. & Lü, B. Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ and FOXP3+ lymphocytes before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cervical cancer. Diagn. Pathol. 13, 93 (2018).

Colombo, N. et al. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1856–1867 (2021).

Oaknin, A. et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy for metastatic, persistent, or recurrent cervical cancer (BEATcc): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 403, 31–43 (2024).

Monk, B. J. et al. First-line pembrolizumab + chemotherapy versus placebo + chemotherapy for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer: final overall survival results of KEYNOTE-826. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 5505–5511 (2023).

Monk, B. J. et al. Durvalumab versus placebo with chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer (CALLA): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 24, 1334–1348 (2023).

Lorusso, D. et al. Pembrolizumab or placebo with chemoradiotherapy followed by pembrolizumab or placebo for newly diagnosed, high-risk, locally advanced cervical cancer (ENGOT-cx11/GOG-3047/KEYNOTE-A18): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 403, 1341–1350 (2024).

Lorusso, D. et al. Pembrolizumab or placebo with chemoradiotherapy followed by pembrolizumab or placebo for newly diagnosed, high-risk, locally advanced cervical cancer (ENGOT-cx11/GOG-3047/KEYNOTE-A18): overall survival results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 404, 1321–1332 (2024).

Topalian, S. L. et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade: a window of opportunity to advance cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 41, 1551–1566 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Improved efficacy of neoadjuvant compared to adjuvant immunotherapy to eradicate metastatic disease. Cancer Discov. 6, 1382–1399 (2016).

Da Silva, D. M. et al. Immune activation in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with ipilimumab following definitive chemoradiation (GOG-9929). Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 5621–5630 (2020).

Krishnamurthy, N. et al. High CTLA-4 transcriptomic expression correlates with high expression of other checkpoints and with immunotherapy outcome. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 16, 17588359231220510 (2024).

Duraiswamy, J., Kaluza, K. M., Freeman, G. J. & Coukos, G. Dual blockade of PD-1 and CTLA-4 combined with tumor vaccine effectively restores T-cell rejection function in tumors. Cancer Res. 73, 3591–3603 (2013).

Wei, S. C. et al. Combination anti–CTLA-4 plus anti–PD-1 checkpoint blockade utilizes cellular mechanisms partially distinct from monotherapies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 22699–22709 (2019).

O’Malley, D. M. et al. Dual PD-1 and CTLA-4 checkpoint blockade using balstilimab and zalifrelimab combination as second-line treatment for advanced cervical cancer: an open-label phase II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 762–771 (2022).

Roland, C. L. et al. A randomized, non-comparative phase 2 study of neoadjuvant immune-checkpoint blockade in retroperitoneal dedifferentiated liposarcoma and extremity/truncal undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Nat. Cancer 5, 625–641 (2024).

Foy, J. P. et al. Immunologically active phenotype by gene expression profiling is associated with clinical benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in real-world head and neck and lung cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 174, 287–298 (2022).

Huang, A. C. et al. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat. Med. 25, 454–461 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Multiparametric immune profiling of advanced cervical cancer to predict response to programmed death-1 inhibitor combination therapy: an exploratory study of the CLAP trial. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 25, 256–268 (2023).

Vittrup, A. S. et al. Overall severe morbidity after chemo-radiation therapy and magnetic resonance imaging-guided adaptive brachytherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: results from the EMBRACE-I study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 116, 807–824 (2023).

Buchwald, Z. S. et al. Radiation, immune checkpoint blockade and the abscopal effect: a critical review on timing, dose and fractionation. Front. Oncol. 8, 612 (2018).

Morisada, M. et al. PD-1 blockade reverses adaptive immune resistance induced by high-dose hypofractionated but not low-dose daily fractionated radiation. Oncoimmunology 7, e1395996 (2018).

Twyman-Saint Victor, C. et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature 520, 373–377 (2015).

McCormack, M. et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by standard chemoradiotherapy versus standard chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer (GCIG INTERLACE): an international, multicentre, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 404, 1525–1535 (2024).

Mayadev, J. et al. Neoadjuvant or concurrent atezolizumab with chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer: a randomized phase I trial. Nat. Commun. 16, 553 (2025).

Li, K. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus camrelizumab for locally advanced cervical cancer (NACI study): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 25, 76–85 (2024).

Nakamura, K. et al. Efficacy and final safety analysis of pre- and co-administration of nivolumab (Nivo) with concurrent chemoradiation (CCRT) followed by Nivo maintenance therapy in patients (pts) with locally advanced cervical carcinoma (LACvCa): results from the phase I trial, GOTIC-018. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 5519 (2023).

Lou, H. et al. Cadonilimab combined with chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab as first-line treatment in recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer (COMPASSION-13): a phase 2 study. Clin. Cancer Res. 30, 1501–1508 (2024).

Wu, X. et al. Cadonilimab plus platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab as first-line treatment for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer (COMPASSION-16): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial in China. Lancet 404, 1668–1676 (2024).

Small, M. et al. Genetic alterations and tumor immune attack in Yo paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 135, 569–579 (2018).

Plaschka, M. et al. ZEB1 transcription factor promotes immune escape in melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 10, e003484 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported financially by Bristol-Myers Squibb (no grant number applicable) and by grants from the SIRIC project (LYriCAN+, INCa-DGOS-INSERM-ITMO cancer_18003) and the Région Rhône Alpes (IRICE Project: RRA18-010792-01–10365). We thank all the patients, their families, the investigators and staff at participating centers (Supplement), the sponsor (ARCAGY: S. Adam, C. Montoto-Grillot, D. Cardoso, E. Cantelli, S. Armanet, B. Votan), the independent Data Monitoring Committee members (T. De La Motte Rouge, X. Paoletti, C. Chargari), the pathologists (G. Bataillon, C. Genestie, C. Jeanne, P.A. Just), Evaluation Médicales et Sarcomes (EMS) at Centre Léon Bérard (CLB), the statistician (S. Chabaud), PATHEC (pathology platform) at Centre de Lutte Contre le Cancer at CLB (A. Colombe-Vermorel, L. Odeyer), PGEB (biological sample management platform) at CLB (S. Tabone-Eglinger), the Centre de Resources Biologiques at ARCAGY-GINECO (Institut Curie: L. Fuhrmann, A. Degnieau, E. Glais), the French National Cancer Institute (INCa), PGC (genomic cancer platform) at CLB, and the Team for Integrated Analysis of the Dynamics of Cancer at CRCL (M. Lamkhioued). We thank Servier Medical Art for providing publicly available medical illustrations (https://smart.servier.com), which were adapted for Fig. 1 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Medical writing support was provided by Jennifer Kelly (Medi-Kelsey Ltd, Ashbourne, UK), funded by GINECO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: I.R.-C., A.d.M., F.L., B.D. Administrative support: I.R.-C. Provision of study materials or patients: I.R.-C., M.-C.K.-F., F.J., D.B.-R., A.A., A.-C.H.-B., A.-M.S., S.B. Collection and assembly of data: A.d.M. Data analysis and interpretation: I.R.-C., R.O., A.d.M., I.T., S.G.-B., P.S., L.M., V.A., J.A., G.C., A.L., H.P., D.V., J.B., C.C., F.L., B.D. Manuscript writing: I.R.-C., R.O., A.d.M., P.S., L.M., B.D. Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

I.R.-C. reports honoraria from AbbVie, Advaxis, Agenus, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Clovis Oncology, Daiichi Sankyo, Deciphera, Genmab, GSK, Immunocore, Immunogen, MacroGenics, Mersana, MSD Oncology, Novartis, OxOnc, Pfizer, PharmaMar, PMV Pharma, Roche, Seagen, Sutro Biopharma, and Tesaro; consulting/advisory roles for AbbVie, Agenus, AstraZeneca, Blueprint Medicines, BMS, Clovis Oncology, Daiichi, Deciphera, Eisai, Genmab, GSK, Immunocore, Immunogen, MacroGenics, Mersana, MSD Oncology, Novartis, Novocure, OSE Immunotherapeutics, Pfizer, PharmaMar, Roche, Seagen, Sutro Biopharma, and Tesaro; research funding (to institution) from BMS, MSD Oncology, and Roche/Genentech; and travel/accommodations/expenses from Advaxis, AstraZeneca, BMS, Clovis Oncology, GSK, PharmaMar, Roche, and Tesaro. F.J. reports consulting/advisory roles for AstraZeneca, Janssen, Ipsen, Pfizer, MSD Oncology, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GSK, Astellas Pharma, Clovis, Amgen, Seagen, Bayer, Eisai, Sanofi/3A, and Viatris and travel/accommodation/expenses from Janssen, AstraZeneca, Ipsen, GSK, BMS, Eisai, MSD Oncology, and Chugai Pharma. D.B.-R. reports travel/accommodation/expenses from Daiichi Sankyo and Lilly. P.S. reports honoraria from HTG Molecular Diagnostics, Inivata, ArcherDx, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Roche Molecular Diagnostics; research funding from Roche, AstraZeneca, Novartis, BMS Foundation, Illumina, and OmiCure; and travel/accommodation/expenses from Illumina, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, and Roche. A.A. reports honoraria from AstraZeneca and GSK and travel/accommodation/expenses from GSK. A.-C.H.-B. reports consulting/advisory roles for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, GSK, Eisai, Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca, MSD, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, and Regeneron. H.P. reports honoraria from MSD, Gilead, and ViiV; consulting/advisory role for MSD; and travel/accommodation/expenses from MSD and Gilead. F.L. reports consulting/advisory roles for GSK, AstraZeneca, and Pharma&, and research funding from MSD Oncology. B.D. reports research funding from MSD. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jyoti Mayadev, Stephane Champiat and Yuhao Xie for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ray-Coquard, I., Kaminsky-Forrett, MC., Ohkuma, R. et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade before chemoradiation for cervical squamous carcinoma (GINECO window-of-opportunity COLIBRI study): a phase II trial. Nat Commun 17, 922 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67646-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67646-z