Abstract

Antibiotic treatment for sepsis has an unintended yet crucial consequence: it exerts a bystander effect on the microbiome, changing its bacterial composition and resistome. Antimicrobial stewardship aims, in part, to minimise this effect to prevent development of subsequent drug-resistant infection, but data evaluating and quantifying these changes are largely lacking, especially in low-income settings which are disproportionately affected by antimicrobial resistance. Such data are critical to creating evidence-based stewardship protocols. Here, we address this data gap in Blantyre, Malawi. We use longitudinal sampling of human stool and metagenomic deep sequencing to describe microbiome composition and resistome pre-, during- and post-antimicrobial exposure. We develop Bayesian regression models to link these changes to individual antimicrobial agents. We find that ceftriaxone, in particular, exerts strong off-target effects, both increasing abundance of Enterobacterales, and the prevalence of macrolide and aminoglycoside resistance genes. Simulation from the fitted models allows exploration of different stewardship strategies and can inform practice in Malawi and elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global public health threat, and a key strategy to prevent it is antimicrobial stewardship. Stewardship aims to avoid unnecessary antimicrobials, to reduce the duration of antimicrobial use to the minimum necessary, and to select an antimicrobial agent with as narrow a spectrum of antibacterial activity as possible1. These principles aim in part to minimise antimicrobial pressure for promotion of AMR in bacteria other than the intended pathogenic target - the so-called bystander effect2. Even though minimising the bystander effect is a key factor in the selection of an antimicrobial agent for a given infection, data quantifying the magnitude and duration of this effect for a given antimicrobial at the individual level are lacking.

Addressing this is key to designing and implementing antimicrobial strategies that can minimise the development of AMR. In sepsis, for example, it is recognised that early antimicrobials confer a survival advantage and global efforts to improve sepsis care prioritise early antimicrobials in suspected sepsis3. But this strategy may result in widespread administration of broad-spectrum antimicrobials, including to people who are ultimately found not to have sepsis or an infectious cause of their illness. This is particularly the case in low-resource settings where diagnostics to inform targeted antimicrobial treatment are frequently unavailable. To truly assess the impact of such a strategy requires not only descriptions of clinical outcomes but tools to quantify the unintended effects of antimicrobials in promoting AMR, both in pathogens and in bystander bacteria.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing provides a method to achieve this, enabling a quantitative assessment of bacterial taxa in a sample (microbiota) and antimicrobial resistance genes (resistome), and linking changes to antimicrobial exposures. Most work has focussed on the development of the gut microbiome in the first days to years of life, where antimicrobial exposure delays development of a mature microbiome4, reduces diversity5 and promotes colonisation with resistant organisms6,7, with evidence that narrower-spectrum treatment may reduce this effect8. In adults, data are largely restricted to healthy volunteers9,10 or specific cohorts11 (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease) in high resource settings—where data suggest that a major determinant of antimicrobial effect on the microbiome is the pre-exposure composition12. Data from low-resource settings, like much of sub-Saharan Africa, is very scanty, particularly in people with febrile illness. This group may be expected to have both a significant broad-spectrum antimicrobial exposure plus different pre-exposure microbiota composition to healthy controls, and so may well have different antimicrobial-induced microbiota changes than healthy volunteers in high-resource settings—but data describing this are largely absent. Given that the highest burden of AMR falls in low-resource settings13 this is an important data gap to address.

This present work aims to address this by leveraging our prior study which described the aetiology and clinical outcomes of a cohort of adults admitted to hospital in Blantyre, Malawi with sepsis14. In that study, we described the development of gut mucosal colonisation with Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-E), as defined by longitudinal sampling and selective culture15. We linked antimicrobial exposure to ESBL-E carriage with a Bayesian modelling approach, demonstrating that antimicrobial exposure acted to promote ESBL-E carriage. Here, we build on this: we describe the dynamics of gut microbiota and resistome of the cohort under antimicrobial pressure, expanding our models to quantify the bystander effect of individual antimicrobial agents. We find that ceftriaxone, in particular, exerts strong off-target effects, both increasing the abundance of Enterobacterales and the prevalence of macrolide and aminoglycoside resistance genes

Results

Quantifying the bystander effect on microbiome: ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin exposure are associated with increased Enterobacterales abundance

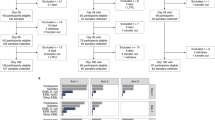

The original study recruited 425 adults between February 2017 and October 2018 into three study arms: 225 participants with sepsis admitted to Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre Malawi, and exposed to antimicrobials, 100 age- and sex-matched antimicrobial-unexposed hospital inpatients and 100 community members. Stool or rectal swab samples were collected at recruitment (within 24 h of hospitalisation for hospitalised participants), then at four subsequent visits: 7, 28, 90 and 180 days later, except for community members who did not have day 7 or 90 samples. For the current analysis we carried out shotgun metagenomic sequencing on a subset of samples: 426 samples from 162 participants passed QC and were incorporated. Table 1 shows the demographics of included participants. Most of the cohort (109/162, 67%) received at least one antimicrobial, most commonly ceftriaxone (94/109 of antimicrobial-exposed, 86%), followed by co-trimoxazole (56/109, 51%), ciprofloxacin (30/109, 28%) and amoxicillin (25/162, 15%, Supplementary Table 1). Co-trimoxazole had a prolonged course length compared to other antimicrobials (Supplementary Table 1) because use was commonly as preventative therapy (CPT) in the context of HIV (52/56 co-trimoxazole prescriptions, 93% were CPT); this also had a reduced dose compared to treatment (480 mg once daily versus 960 mg twice daily). Antibiotic combination therapy was unusual (Supplementary Fig. 1, with 1,418/9,559 [15%] person-days of antibacterial exposure) but where it occurred, it was most commonly co-trimoxazole with another antimicrobial (1,034/1,418 [73%] person-days of antibacterial combination therapy). Sequential antibacterial exposure was common: 27/109 (25%) participants received one antibacterial, 48/109 (44%) two, and 34/109 (32%) three or more antibacterials.

We first examined microbiome composition stratified by study arm and visit. There were shifts in alpha diversity (Shannon diversity), most marked at visit 1 (day 7) in the hospitalised/antimicrobial-exposed group (Fig. 1A), corresponding to the time of maximal antimicrobial exposure. We explored this effect with linear modelling of Shannon diversity. A within-participant correlation structure accounted for repeated sampling, and we included the top four antimicrobials—ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole and amoxicillin and hospitalisation as covariates (hence accounting for different durations of antibiotic exposure or hospitalisation), with an exponential decay of effect following cessation. Stool (versus rectal swab) was included as a covariate to account for any differences introduced by different sampling methods. This identified that ceftriaxone exposure (Fig. 1B, D) was most strongly associated with a decrease in diversity; cotrimoxazole had the least effect. Hospitalisation itself was also associated with a reduction in diversity (Fig. 1B, D). Sampling stool (versus rectal swab) did not have an association with diversity (Fig. 1C). Shannon diversity returned to baseline by ~50 days in simulations following perturbation (Fig. 1D).

A Shannon Diversity stratified by study arm and visit. B, C parameters from modelling Shannon Diversity as a function of antimicrobial exposure. beta_s = effect of stool (vs rectal swab), alpha = magnitude of within-participant correlation, length scale = decay parameter of within participant correlation (on standardised time scale, 1 unit = 55 days), beta_0 = model population intercept, tau = decay constant of effect of antimicrobial exposure (on standardised time scale, 1 unit = 55 days). Antimicrobial and hospitalisation parameters can be interpreted as the change in mean Shannon Diversity given exposure; error bars are 95% credible intervals of parameter value (D) simulated mean Shannon Diversity in stool for hospitalisation (10 days) and antimicrobial exposure (7 days) with different antimicrobials; shaded areas are 95% credible intervals from predictions (E) Principal coordinate plot of all-against-all Bray Curtis dissimilarity (beta diversity) with 95% confidence intervals assuming student T distribution stratified by study arm showing between-arm differences in beta diversity. F Within-participant Bray-Curtis dissimilarity to baseline sample, stratified by arm, showing that participants admitted to hospital and exposed to antimicrobials have persistent changes in beta diversity over six months, compared to community and hospital controls. P values are from a Kruskall–Wallace test between all groups at a given visit (the degrees of freedom/test statistic for visits 1, 2, 3, 4, respectively, are 1/3.89, 2/11.18, 1/4.06, 2/8.44). In all panels, boxplots show median as line and first and third quantiles as boxes, with whiskers that extend form box edge to the largest value no further than 1.5 times interquartile range from box edge. The number of participants included in the analysis is given in Supplementary Table 3.

We assessed beta diversity with all-against-all Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and principal components analysis; there was overlap of all three arms of the study in PCA space, but 61 hospitalised/antimicrobial exposed samples fell outside the 95% percentile of the distribution of the antimicrobial unexposed samples, consistent with different microbiome composition (Fig. 1E). Hospitalised/antimicrobial exposed participants had persistent differences in within-participant Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between baseline and subsequent samples (Fig. 1E), compared to controls. Hence, though Shannon diversity returned to baseline, there is evidence for changes in microbiome composition due to antimicrobial exposure, which persist out to 6 months following exposure.

At all time points and across all arms the most abundant Phylum was Bacteroidetes (Fig. 2A); Proteobacteria (largely Enterobacterales) were more abundant at visit 1 (day 7) in the hospitalised/antimicrobial exposed group (Fig. 2A–C), the time point which corresponds to maximal antimicrobial exposure. To quantify this, we fit negative-binomial Bayesian mixed effects models to the absolute number of reads assigned to a given taxon with a per-participant random effect with a multivariate-normal correlation structure to account for repeated measurements, a per-sample read depth offset to account for varying sampling depth and covariates (antimicrobial exposure, hospitalisation, and stool versus swab) as above. A separate model was fit for each of the top three phyla, the top 10 orders of phylum Proteobacteria, and the top 10 genera of order Enterobacterales.

Relative abundance of top 3 Phyla (A), top 3 Proteobacteria orders (B) and top 3 Enterobacterales genera (C), stratified by study arm and visit, showing higher abundance of Proteobacteria, Enterobacterales and Escherichia at visit 1 in the antibiotic exposed, corresponding to maximal antimicrobial exposure. In all panels, boxplots show median as line and first and third quantiles as boxes, with whiskers that extend form box edge to the largest value no further than 1.5 times interquartile range from box edge. D parameter values for effect of antimicrobial exposure or hospitalisation on microbiome composition, on log scale with 95% credible intervals; parameter values > 1 correspond to an increase <1 to a decrease. E, F simulated antimicrobial exposures (7 days) showing proportion of Proteobacteria reads (right panel), proportion of Proteobacteria reads that are Enterobacterales (middle panel), proportion of Enterobacterales reads that are Escherichia (left panel) with shaded area showing 95% credible intervals in stool. The number of participants included in the analysis is given in Supplementary Table 3.

The results of these models are shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2. Ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin are associated (95% Credible Interval [CrI] effect > 1 on log scale) with increase in Proteobacteria abundance, driven by increase in Order Enterobacterales and, within that order, the genera Escherichia and Shigella (though credible intervals on genus-level parameter estimates are wide and 95% CrI cross 1). Across all models, the posterior median half-life of the exponential decay of exposure effect was 11 (range 4–156) days (Supplementary Fig. 2). Simulation of the fitted models (Fig. 2E, F) allows comparison of the effect of different antimicrobial strategies on microbiome composition; generally, antimicrobial-associated effects return to baseline by 30 days following exposure. Rectal swabs (versus stool) had a higher abundance of Proteobacteria, driven by the genera Enterobacterales, Campylobacterales, and Pseudomonadales, and within Enterobacterales, a higher abundance of Escherichia/Shigella, Klebsiella, and Salmonella.

Ceftriaxone exerts a bystander effect on the resistome, increasing prevalence of aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance

We used metagenome assembly followed by AMRFinderPlus to define each individual’s resistome over time. Across the 426 samples, we identified 369 unique AMR genes of 25 classes and 60 subclasses (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. 3); trimethoprim, tetracycline, beta-lactam, sulphonamide, and lincosamide/macrolide/streptogramin resistance genes were present in almost all samples, as were aminoglycoside resistance genes despite low levels of intestinal excretion of these drugs in humans. The plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr was detected twice (mcr10 and mcr10.1): in two different participants, neither of whom had hospital admission within the previous 3 months, despite colistin being prohibited in Malawi, as seen in a recent large E. coli genome collection from Blantyre16. Many of the cephalosporin and carbapenem resistance genes were Bacteroides -specific and less clinically relevant in terms of causing drug-resistant infection in our setting (Supplementary Fig. 4); excluding these (which we defined as defined as cfiA, cblA, crxA, cepA or cfxA beta-lactamases), cephalosporin and carbapenem resistance genes were identified in 74% (102/138) and 7% (10/138) of samples from hospitalised participants respectively (Supplementary Table 2), most commonly blaCTX-M-15 and blaOXA-818- (Supplementary Fig. 4).

A Prevalence of AMRFinderPlus-defined resistance gene subclass with exact binomial 95% confidence intervals. B Selected AMRFinderPlus-defined gene subclass prevalence stratified by visit and arm with exact binomial 95% confidence intervals. Colours represent different study arms. Cephalosporin and quinolone resistance gene prevalence shows little relationship with visit/arm, but macrolide and aminoglycoside resistance subclasses have a higher prevalence at visit 1 in the hospitalised/antimicrobial exposed group, consistent with an association with antimicrobial exposure. C Parameter values from modelling antimicrobial resistance gene subclass presence as a function of antimicrobial exposure. Parameter values (and 95% CrI) can be interpreted as logged odds ratio. Parameter values with a clear association between exposure and outcome (defined at lower bound of 95% CrI > 0) are coloured red. D, E simulated AMR gene subclass prevalence in stool for selected subclasses, following a 10-day hospital admission and 7-day exposure to a given antimicrobial agent. Lines show median posterior prediction, shaded area 95% credible interval. Colours show different antimicrobial exposures. Ceftriaxone is associated with an increase in aminoglycoside and clindamycin-erythromycin-streptogramin B subclass genes not seen with the other agents. F Associations of exposures to presence of AMR gene subclass restricted to beta-lactamases with models fit separately to Bacteroides-associated genes (defined as cfiA, cblA, crxA, cepA or cfxA beta-lactamases) or all others (defined as all other genes), expressed as parameter values and 95% credible intervals. The number of participants included in the analysis is given in Supplementary Table.

Five AMRFinderPlus defined gene subclasses were more prevalent in hospitalised/antimicrobial exposed group at visit 1 (day 7) than other study arms or visits, corresponding to time of maximal antimicrobial exposure (Supplementary Fig. 5): they conferred aminoglycoside, macrolide and cephalosporin resistance, consistent with these subclasses being associated with antimicrobial exposure. To quantify this effect and relate it to individual antimicrobial agents we fit models identical to the taxonomy models but including the presence/absence of AMRFinderPlus gene subclass in a mixed-effect logistic regression model (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. 6, 7). These confirmed that ceftriaxone exposure was associated (95% CrI of odds ratio >1) with increased prevalence of genes conferring resistance to aminoglycosides (primarily aac(6’)-I, aac(3)-II and aph(3’)-II alleles), macrolides (mphA, msrC, ermB) and rifamycins (arr). The effect of ciprofloxacin was similar: it was associated with the presence of aminoglycoside (aac(6’)-I) and macrolide (mphA, ermC) genes. Amoxicillin and co-trimoxazole were associated with fewer resistance subclasses than ceftriaxone (amoxicillin with mphA macrolide aac(6’)-I aminoglycoside resistance genes and co-trimoxazole with msrD and mefA macrolide resistance and qnr plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance). Stool (versus rectal swab) did not have a strong effect on the presence of resistance gene subclass: spectinomycin resistance genes were more likely to be identified in rectal swab samples, and trimethoprim resistance genes more likely to be identified in stool samples, but in both cases, confidence intervals were wide (Supplementary Fig. 6).

The 95% CrI of effect estimates for the association of all antibiotics with cephalosporin resistance genes crossed the null (Fig. 3C), but cephalosporin resistance genes were very commonly detected across all samples. Bacteroides-specific genes were included in this analysis (Fig. 3B) which were present in almost all samples - this could obscure an effect on other beta lactamases in the modelling analysis. Hence, we stratified all beta lactamases as Bacteroides-associated (defined as cfiA, cblA, crxA, cepA or cfxA beta-lactamases) or not (all other beta-lactamases) and refit the models (Fig. 3F). This showed that, consistent with our previous culture-based analysis, there was an association of ceftriaxone exposure with presence of non-Bacteroides cephalosporin resistance genes (largely blaCTX-M-15); hospitalisation and co-trimoxazole exposure also showed an association with cephalosporin resistance, as did amoxicillin and ciprofloxacin, though in the case of the latter two antimicrobials the 95% CrI crossed the null. Co-trimoxazole was also associated with the presence of narrow spectrum beta lactamases (most commonly blaTEM and blaOXA).

Overall, and across all models, the half-life of the effect of antimicrobial exposure was more prolonged in resistome that taxonomy models, with a posterior median (range) 76 (8–245) days; simulations from the posterior quantify the effect of ceftriaxone in particular in driving aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance genes (Fig. 3D, E), and again show that antibiotic-induced perturbations in resistome return to baseline by around 30 days.

Because AMRFinderPlus is likely biased towards pathogenic/culturable bacteria, we repeated the above analysis using ResFinderFG, which contains antibiotic resistance genes identified from functional metagenomic studies17. In contrast to the AMRFinderPlus analysis there was no clear relationship between prevalence of resistance genes expected to confer resistance a given antimicrobial agent and study arm or visit; prevalence of aminoglycoside resistance genes was higher in the hospitalised/antimicrobial exposed, but confidence intervals were wide and overlapping (Supplementary Fig. 8). In the modelling analysis, only presence of genes expected to confer resistance to gentamicin were associated with ceftriaxone exposure, in contrast to AMRFinderPlus-identified genes (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Resistance is associated with clinically relevant Enterobacterales, including E. coli

In the AMRFinderPlus analysis, presence of genes of the macrolide and aminoglycoside resistance subclasses (as well as chloramphenicol and the fluoroquinolone subclasses) correlated with Proteobacteria abundance (Supplementary Fig. 10), particularly Enterobacterales, and Escherichia within this order. To explicitly link AMR gene presence to clinically relevant Enterobacterales, we focussed on E. coli. We binned all assembled contigs, identified bins comprising E. coli (defined as Average Nucleotide Identity to an E. coli reference > 95%) and identified AMR genes that could be attributed to E. coli using AMRFinder using the E. coli specific models which allowed identification of point mutations conferring resistance (e.g. in quinolone-resistance determining region, QRDR) as well as AMR gene presence. We compared the diversity of the genomes identified using this approach to our previous analysis of E. coli genomes we identified in the same samples using ESBL-selective media by clustering the genomes using popPUNK v2.7.2. As expected, the genomes from the metagenomic approach were more diverse (33 unique popPUNK clusters in culture-derived genomes versus 95 in the metagenome-derived genomes, Fig. 4A). We identified 93 unique AMR associated genes/mutations in 260 E. coli bins: predicted fluoroquinolone resistance was common (128/260 [49%] samples, commonly gyrA and parC mutations), as was trimethoprim (75/260 [29%], all dfr alleles) and cephalosporin resistance (68/260 [26%], most commonly blaCTX-M-15 Supplementary Fig. 11).

A Comparing the diversity of the metagenome-assembled E. coli genomes to genomes from ESBL-selective culture using popPUNK; number of samples (y-axis) for a given popPUNK cluster (x-axis) show that the metagenome-assembled genomes are more diverse. B Prevalence of AMRFinder gene subclass in samples with a high-quality E. coli metagenome-assembled genome (n = 259) with exact binomial 95% confidence intervals. C Parameter values and 95% credible intervals from fitted models quantifying the effect of exposures (panels) on the presence of AMR gene subcategory in E. coli metagenome-assembled genomes. Coefficients are on the log scale and can be interpreted as exposure resulting in a log odds ratio for the presence of a given gene. A value of 0 (dotted line) is no change. The number of participants included in the analysis is given in Supplementary Table 3.

Fitting this E. coli specific AMRFinder subclass presence/absence data using the models described above (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 12, 13) revealed that the association of ceftriaxone exposure with aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance was at least partly mediated via resistance in E. coli: presence of aminoglycoside (aac(3)-IId and aac(6’)-Ib) and macrolide (mphA) genes in E. coli was associated (95% CrI or odds ratio > 1) with ceftriaxone exposure (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 13). Ceftriaxone exposure was associated with AMR determinants of multiple other subclasses including cephalosporin (largely blaCTX-M-15 and blaCMY-2 genes), but also of the quinolone (largely QRDR point mutations) and sulphonamide (largely sul alleles) subclasses, and point mutations associated with fosfomycin, colistin and aztreonam resistance (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 13). Quinolone exposure was associated with presence of trimethoprim resistance determinants in E. coli; amoxicillin exposure with quinolone and fosfomycin resistance mutations in E. coli, whereas co-trimoxazole exposure was not associated with clinically relevant antimicrobial resistance determinants in E. coli. Hospitalisation, independent of exposure to antimicrobials of these four classes, was associated with the presence of resistance determinants of the cephalosporin and aztreonam subclass in these E. coli genomes. Stool (versus rectal swab) did not show an association with the presence of resistance genes in this E. coli focussed analysis.

Discussion

We present here a description of the bystander effect of antimicrobial treatment for sepsis in Blantyre, Malawi on microbiome and resistome composition, using two approaches to identifying resistance genes: AMRFinderPlus and ResFinderFG, to focus on culturable/pathogenic and unculturable/commensal bacteria, respectively. Using a Bayesian modelling approach, we quantify this effect, finding that different antimicrobials act to promote different bacterial taxa and resistance genes. Ceftriaxone, the first-line treatment for sepsis in Malawi, has a broad effect on microbiota and resistome composition. In this setting with a high prevalence of detectable baseline cephalosporin resistance genes, it is associated with an increase in abundance of Enterobacterales, including Escherichia, a key pathogenic genus. It is also associated with an increased prevalence of cephalosporin, macrolide and gentamicin resistance genes in E. coli, and non-Bacteroides cephalosporin, macrolide, gentamicin and rifamycin resistance gene prevalence generally in the resistome as identified by AMRFinderPlus. Ciprofloxacin—another agent with high prevalence of baseline detectable resistance genes—is similarly associated with an increase in Enterobacterales, with an increase in macrolide and aminoglycoside resistance gene prevalence in the resistome as identified by AMRFinderPlus. We did not identify a clear association of ciprofloxacin exposure with cephalosporin or quinolone resistance, but the relative rarity of ciprofloxacin exposure meant that confidence intervals were wide. Amoxicillin and co-trimoxazole had a less pronounced effect on microbiome and resistome composition as defined by AMRFinderPlus, though again credible intervals were wide for these agents. Importantly, non-Bacteroides cephalosporin and beta-lactam resistance genes as defined by AMRFinderPlus were associated with co-trimoxazole exposure, an important finding when co-trimoxazole is used on a huge scale in community settings across the country in the context of co-trimoxazole preventative therapy in HIV. These gross antibiotic-specific perturbations in microbiome and resistome return to baseline over a timescale of around a month, though there is evidence of persistent changes in composition (beta diversity compared to baseline) out to six months. We found that resistance genes as identified by ResFinderFG showed considerably less association with amicrobial exposure than those identified by AMRFinderPlus; this could be consistent with a relative stability of the non-culturable resistome as compared to the culturable/pathogenic resistome. Overall, we can draw several conclusions from our findings.

First, and most importantly, quantification of the bystander effect on resistome provides evidence to inform antimicrobial stewardship protocols in Malawi and elsewhere. One of the aims of stewardship is to minimise antimicrobial exposure (both in terms of duration and spectrum), but without a quantitative measure of the off-target effect of individual antimicrobial agents, such strategies cannot be fully evidence based. Ceftriaxone, the first-line treatment for sepsis in Malawi, demonstrates a profound effect on microbiota and resistome composition but these deleterious effects must be balanced against its activity on the locally prevalent pathogens. Prior analysis of this cohort has demonstrated that 83% of participants with sepsis receive ceftriaxone but this agent would be expected to be an effective therapy in only 24%14. There is clearly scope for expanded stewardship (both to reduce ceftriaxone exposure in those who do not require it, but also to expand access to alternate, effective, antimicrobials such as carbapenems, where required) but any strategy comes with resource implications (a significant consideration in this resource-limited setting) and possible effects on the microbiota. By quantifying the effect of antimicrobial exposure, our modelling analysis paves the way for in silico simulation from the posterior of our fitted models to quantitatively compare the microbiota effect of competing stewardship strategies. For example, a high proportion of the 83% of people with sepsis in our prior study who received ceftriaxone have disseminated TB14; what would the impact on colonisation with resistant organisms be of a rapid de-escalation of ceftriaxone when the TB diagnosis is made? Without data describing the effect of antimicrobial exposure on the microbiome, it is not possible to answer this question, but the data and the modelling framework we present can answer this question with a simulation approach, to inform local antibiotic policies and future interventional studies.

Second, our findings highlight important similarities but also differences between our cohort and high-resource settings. A reduction in microbiome diversity in high-resource settings following antimicrobial exposure is well described, both in healthy volunteers9,18,19, and hospitalised inpatients20,21 and most studies report an approximate return to baseline alpha diversity over months9,18, though differences in species or resistome composition or pre-to-post treatment beta diversity may persist for six months or more, as we demonstrate. In our analysis, we link antimicrobial exposure to the presence of Proteobacteria, particularly Enterobacterales. Elsewhere, blooms of pathobionts including E. coli and Klebsiella spp. have been described in healthy volunteers following meropenem/vancomycin/gentamicin administration in the US18, but in Oxford, UK21 ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin exposure were associated with reduced Enterobacterales abundance in hospital inpatients. A potential explanation could be a difference in resistance mechanisms present in commensal E. coli circulating in the community between UK and Malawian settings: we have previously demonstrated very high prevalence of human carriage and environmental contamination with ESBL producing E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in our setting in Malawi16,22.

Directly comparative data linking antimicrobial agent to resistance gene presence from elsewhere are scanty. Previous studies in high-resource settings have linked some individual agents (e.g. meropenem, vancomycin, gentamicin, levofloxacin, azithromycin, cefpodoxime) to changes in diversity of composition and resistome, often in healthy volunteers and mostly using aggregate measures of resistome diversity9,18,20,23. Heterogeneity in analysis makes it difficult to compare between studies or extrapolate from the findings to the impact on a given antimicrobial stewardship strategy in different geographical settings. Nevertheless, where sought, a bystander effect on resistome is generally demonstrated: Cefpodoxime (a third generation cephalosporin) was found to be associated with an increase in the Bacteroides-associated beta-lactamase gene cfxA and tetracycline resistance genes tetO and tet40 in 20 healthy volunteers in the United States18. A patient cohort in Oxford, UK21 found an increase in abundance of aminoglycoside and tetracycline resistance genes following beta lactam exposure (as we demonstrate). In Germany ciprofloxacin was associated with an increase in macrolide and cephalosporin resistance gene abundance but a decrease in aminoglycoside resistance gene abundances (the opposite of our findings), compared to co-trimoxazole18. This highlights the complexity of the antimicrobial effect on microbiome which is likely modified by diet, pretreatment bacterial structure, and host living environment including water sanitation and hygiene12,24. In our cohort, hospitalisation was associated with changes in microbiome and resistome, which could be due to ward crowding and sanitation (one shared toilet per ward, limited handwashing facilities and availability of detergent and unhygienic facilities for patient attendants25) – though confounding is also possible if hospitalisation was associated with receipt of medications which could modulate the microbiota.

Third, our findings highlight a key role for E. coli as a carrier of AMRFinderPlus-defined AMR genes in our setting; antimicrobial exposure (particularly ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin) is associated with an increase abundance of Enterobacterales, (largely due to Escherichia abundance) and drug resistance in E. coli. In high income settings, E. coli has repeatedly been identified as a significant contributor to AMR gene carriage in the microbiome of infants and young adults6,23. Presence of drug-resistant E. coli in stool increases risk of subsequent infection26 and microbiome-modulating strategies such as faecal microbiota transplant have been demonstrated in case reports to promote colonisation resistance to resistant Enterobacterales27. Given our findings, strategies to reduce colonisation with drug-resistant Enterobacterales could have a significant role to play in moderating the resistome in people treated with antibiotics in Malawi, with a subsequent effect on invasive infection. This would certainly include improved water, sanitation and hygiene in the community and infection prevention and control strategies in hospital, but also potentially trials of probiotic/prebiotic and antimicrobial stewardship with bystander AMR as an outcome.

The strengths of our study are our longitudinal sampling, and modelling approach, which together allow us to account for between-person microbiome variation, and describe the microbiome effect of antimicrobials in an under-studied low-resource setting. Our Bayesian modelling strategy allows us to fit complex models in a computationally straightforward manner (allowing the timescale of decay of antimicrobial effect to vary, for example) and to move beyond null hypothesis significance testing and simulate from the posterior of our models to explore the effect of different antimicrobial strategies. The flexible modelling approach can be easily modified to reflect different sampling strategies.

The major limitations of the study are that, despite the modelling, residual confounding is very likely to remain which warrants caution in causal interpretations: for example, co-trimoxazole is largely used as a preventative therapy which is associated with HIV. Given the collinearity of HIV and CPT, it is not possible to include both variables in the models. We included both stool and rectal swabs in our analysis because of the nature of our patient population (who could not always provide stool); we have accounted for this by including sample type as a covariate in our modelling, but if sample type was associated with other participant characteristics, this could have introduced confounding. Our sample selection and subsequent lack of age-sex matching may have resulted in confounding or other bias. Some exposures – ciprofloxacin and particularly amoxicillin, were rare compared to ceftriaxone, resulting in wide confidence intervals of parameter estimates, so absence of evidence of an effect may not represent evidence of absence. These effects are important to quantify in the future given the importance of these agents in the community. It is also possible—in this setting where antimicrobials can be easily available without a prescription25—that participants received antimicrobials, which could affect microbiome/resistome composition—especially in the hospitalised/antimicrobial-exposed group who had an otherwise-unexplained high Proteobacteria prevalence.

We present simulations from the posterior but have not carried out any formal out-of-sample validation; hence, the models are likely overfit to data and should not be interpreted as predictions but rather as aids to understanding the effects of different covariates in the models. True predictive modelling would require a larger data set. Though we present an analysis linking antimicrobial exposure to microbiome changes, the link between these changes and clinically important outcomes - transmission, and development of invasive infection—are not well understood and should be a priority for future research. In keeping with other short-read shotgun-metagenomic studies, assembling mobile genetic elements and linking them to the bacterial genomes with which they were associated is not possible; it is likely, therefore, that our E. coli binning approach may underestimate E. coli-associated AMR if MGEs are not correctly assigned to a bin. Our identification of AMR genes in general is dependent on their presence in the databases we used. We did not perform any culture-based identification of bacteria, beyond our previously published selective ESBL-E culture analysis15.

In conclusion, we use metagenomic sequencing and Bayesian modelling to quantify the bystander effect of antimicrobials on microbiome composition and resistome in Malawi. We demonstrate strong promotion of Proteobacteria, particularly Enterobacterales, associated with ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin exposure, and off-target increase in prevalence of aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance genes. These changes are mediated at least in part by the presence of resistance genes in E. coli. Amoxicillin and, particularly, co-trimoxazole, are associated with less microbiome and resistome perturbation, though co-trimoxazole shows an association with cephalosporin resistance, which, given the widespread national use of cotrimoxazole preventative therapy, may be a significant driver of ESBL gene colonisation. These findings can begin to inform antimicrobial stewardship protocols in Malawi.

Methods

Inclusion and ethics statement

The study was approved by the research ethics committees of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (16-062) and Malawi College of Medicine (P.11/16/2063). The study has included local researchers throughout the research process and took place in the context of the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome clinical research project, which has ongoing capacity-building programmes. The research does not result in stigmatisation, incrimination, discrimination or otherwise personal risk to participants and does not involve health, safety, security or other risk to researchers. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study design and setting

The design of the observational clinical cohort study on which this analysis is based is described in detail elsewhere15. The study was approved by the research ethics committees of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (16-062) and Malawi College of Medicine (P.11/16/2063).

Samples were collected between February 19th, 2017, and 1st May 2019. In arm one, adults at least 16 years old with sepsis - defined as fever (or history of fever within 72 h) and evidence of organ dysfunction (oxygen saturation <90%, systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, respiratory rate >30 breaths/minute or Glasgow Coma Score <15) were enroled. Two comparator cohorts were also enroled: arm 2 was composed of age- and sex-matched adults being admitted to hospital via the Emergency Department but with no current plan for antibiotic therapy from the attending clinical team, and arm 3 was a group of age-, sex- and location-matched community controls. Participants were excluded from the comparator groups if they had received antibiotics within the past four weeks. Hospitalised participants were followed up daily by a member of the study team to record exposure to antibiotics. Treatment decisions were taken by clinicians who were independent from the study team. On discharge, patients were followed up at approximately days 7, 28, 90 and 180, corresponding to visits 1, 2, 3 and 4. Day 7 and 90 (1 and 3) visits were omitted for the community group. At baseline (visit 0, within 24 h of hospital admission for hospitalised participants) and at each study visit, a stool sample or rectal swab was collected. Missing samples were unusual (13% of visits) and distributed across all study visits; because of participant deaths more samples were collected in the earlier visits, Supplementary Fig. 14); full flow of participants through the study is described in the original study publication15. Following incubation in enrichment broth, culture and identification (using analytical profile index) for the presence of ESBL-E organisms was carried out, and primary samples were stored.

Isolate sequencing

Isolates selected for whole genome sequencing and their extraction have been described previously28,29, and these data are available at in the European Nucleotide Archive under project IDs PRJEB26677, PRJEB28522, PRJEB36486 and PRJNA869071 with linked metadata available as the R blantyreESBL package30. Briefly, DNA was extracted from overnight nutrient broth cultures using the Qiagen DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed at the Wellcome Sanger Institute using the Illumina HiSeq X10 system (Illumina Inc., USA), producing 150 bp paired-end reads.

Metagenomic sequencing

Samples for metagenomic sequencing were stored at 4 degrees Celsius immediately following collection then at −20 degrees Celsius within 24 h, and DNA extracted within 2 weeks. A subset of 450 stored extracted DNA samples from 163 participants were selected for metagenomic sequencing. These were selected on pragmatic grounds to maximise longitudinal representation. Samples were not sequenced from individuals who had only completed one study visit. Due to the process of selecting samples for sequencing, age and sex matching of the comparator cohorts was not maintained. Genomic material was extracted using the Qiagen DNA stool mini kit (Hilden, Germany), with the addition of a bead-beating step. A sterile saline negative control sample for each extraction run was included (25 in total), which were also prepared and sequenced as below. Library preparation was performed with the NEBNExt Ultra II FS kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts, Unites States) on the Mosquito Ultra II platform (Qiagen), using a 1/10 reduced volume protocol. Metagenomic sequencing was performed at the University of Liverpool Centre for Genomic Research (Liverpool, U.K.), using the Illumina NovaSeq platform with an S4 flow cell (San Diego, California, United States). Sequencing was multiplexed and aimed at a depth of 100 million reads per sample. Reads were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive, under project accession PRJEB86881.

Bioinformatic analysis

Quality control of reads

Modules from the MetaWRAP (v1.3.2) pipeline31 were used to standardise metagenome analysis. All paired-end reads underwent quality control using the MetaWRAP “read_qc” module to remove low-quality, adapter, and human sequence reads. The T2T consortium complete human genome (GCF_009914755.1) and human mitochondrial genome (NC_012920.1) were used as references for the removal of human reads. Samples with sequencing failure (fewer than 0.5million reads were excluded from further analysis). Excluding these, the samples had a median (IQR) of 133 (107–150) million reads for stool samples and 82 (58–128) million reads for rectal swab samples, with median (IQR) proportion of human reads 0.1% (01–0.6%) for stool samples and 4.8% (0.4–20.2%) for rectal swab samples.

Read-based taxonomy

Reads were assigned taxonomy with Kraken232 (v2.1.2) using a custom database comprising all RefSeq complete genomes and proteins for archaea, bacteria, fungi, viruses, plants, and protozoa downloaded on 14 March 2023. This database also included complete RefSeq plasmid nucleotide and protein sequences, as well as a version of the NCBI UniVec database minimised for false positives. A confidence threshold of 0.1 was applied for read assignments, and reports were generated for downstream analysis.

Assembly of metagenomes and E. coli bins

Metagenomic reads were assembled using metaSPAdes33 (v3.1.3) under default settings. To generate the best bins possible, three binning strategies (MetaBAT2, CONCOCT and MaxBin2) were employed across all samples via MetaWRAP. The reference genome for the E. coli type strain (ATCC 11775, Accession: GCF_003697165.2) was then used as a reference for FastANI34 (v1.3.3) to identify any bins that were E. coli to the species level (>95% ANI). CheckM235 (v1.0.2) was then used to select bins that meet MIMAG standards (>50% completion, <10% contamination). For each sample, the most complete bin was then selected for downstream analysis, yielding 261 bins, representing the same number of samples.

Calling antimicrobial resistance from metagenomes and quantifying the bystander effect

To understand the general contribution of the microbiome to antimicrobial resistance, metagenomes were analysed to find acquired antimicrobial resistance genes using AMRFinderPlus36 (v3.11.20) under default settings (coverage 50%, identity 90%). Once E. coli was determined to be a primary organism of interest, a second analysis was conducted using an E. coli-specific model within AMRFinderPlus, allowing detection of point mutations associated with resistance. This refined analysis was applied to the E. coli metagenome-derived genome bins, and E. coli isolates. This approach aimed to compare the diversity of AMR genes between cultured and uncultured samples and to quantify the extent to which specific AMR determinants could be attributed to the E. coli metagenomic bins. Isolate reads were assembled using SPAdesSPA37 (v3.1.3).

To identify genes that may be associated with unculturable bacteria, we performed the same analysis using the ResFinderFG v2.0 database, which collates antimicrobial resistance genes from functional metagenomic studies17. We generated a binary presence/absence matrix of ResFinderFG v2.0 antibiotic resistance genes across samples; to align the methods with the AMRFinderPlus analysis, hits were retained if BLAST alignments had ≥90% identity and ≥50% coverage of the reference gene. Gene names and antibiotic classes were extracted directly from FASTA headers.

Cultured vs uncultured diversity using PopPUNK

In order to characterise diversity in a comparable way, PopPUNK38 (v2.7.2) was used to assign clusters to E. coli bins and isolates, querying the “reference only” Escherichia coli v2 database. The resulting PopPUNK clusters were visualised in Microreact39 and summarised as frequency tables to identify the dominant clusters observed when comparing metagenomic versus culture-based approaches.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

Study design and sample size are detailed above. No data were excluded from the analyses. The study was not randomised and there was no blinding.

All analysis was carried out in R40 v4.4.2 and all plots were generated with ggplot41 v3.5.1. Unless otherwise stated, summary statistics are presented as medians with interquartile ranges or proportions with exact binomial confidence intervals. Shannon Diversity and Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity were used to quantify alpha and beta diversity, and principal components analysis on alpha diversity were carried out using the PhyloSeq42 v1.5.0 R package. Kruskall-Wallis test to compare Bray-Curtis dissimilarity to baseline across the three study arms was carried out with ggstatsplot v0.13.0. Linear models as implemented in lm function in R were used to compare Shannon diversity between stool and rectal swab samples and PERMANOVA as implemented in the adonis2 function in the R package vegan v2.6.8 used to compare Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between stool and rectal swab samples.

Comparing stool and rectal swab samples

Comparing rectal swab and stool samples in terms of Shannon diversity, Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and taxonomy (Supplementary Fig. 15) showed that, though they were similar (stool vs rectal swab effect on Shannon diversity −0.15 (95% CI −0.36–0.07, p = 0.17, R2 = 0.002 from linear model) there were some differences in beta-diversity (PERMANOVA p = 0.001, R2 = 0.02); we accounted for this by including stool versus rectal swab as a covariate in the modelling analysis.

Linear regression: Shannon diversity

To quantify the effect of antimicrobial exposure on Shannon diversity, taxa abundance and presence of AMR genes, and account for any differences from including stool and rectal swab samples together, we constructed Bayesian regression models using the Stan probabilistic programming language, accessed via cmdstanR v0.8.1 using cmdstan v2.35. All the models had the same correlation structure to account for repeated measurements on individuals; the simplest model with the linear regression model for Shannon diversity, where the sample \({y}_{i}\) is given by

Where μ is the mean and σ the standard deviation of the normal distribution. \(i={{\mathrm{1,2}}},...n\) where n is the number of samples. There are \(j\) covariates in the model; \({x}_{{ij}}\) is a matrix with \(n\) rows: row \(i\) gives the covariate values for sample \({y}_{i}\); \({\beta }_{j}\) are the regression coefficients. \(f\) encodes the within-participant correlation; it is 0 for different participants, but within-participant for a given sample is defined by

i.e. a multivariate normal distribution with a k-by-k covariance matrix for \(k\) within-participant samples. This matrix uses an exponentiated quadratic kernel:

Where \({t}_{{ij}}\) is the difference in time between two samples. \(\alpha\) encodes the magnitude of the within-particpant correlation and \(l\), the length scale, the temporal correlation.

The effect of antimicrobials was encoded in a time-dependent manner, \(\beta (t)\).

If antimicrobials are administered between \({t}_{a}\) and \({t}_{b}\) then during exposure, the effect of a given antimicrobial j is

The effect after exposure is

And the effect before any exposure (or for a participant with no exposure) is

This allows the effect of antimicrobial exposure to decay exponentially on a time scale fit to the data, with a rate of decay defined by the parameter tau. Stool versus rectal swab is included in the model as a binary covariate without this time-dependent structure (i.e. a standard linear model covariate).

Priors were Student t distribution with 3 degrees of freedom and mean 0, sd 3 for \(\beta\), \(\tau,\alpha .\) \(l\) used an inverse gamma distribution with both parameters set to 3; the mean of the prior on \({\beta }_{0}\) was 3.

Negative binomial regression: taxon abundance

Modelling absolute read numbers assigned to a given taxa used the same linear predictor, but assumed that the read number was negatively binomially distributed with an over dispersion parameter \(\phi\), and added an offset to account for varying read depths

Where \({d}_{i}\) is the number of reads for sample \(i\), and \({y}_{i}\) here is the number of reads assigned to the taxa of choice. A different model was fit for the top 10 phyla, orders, and genera. Priors were the same as the linear model except the prior on the intercept (β0) was set to a mean of −3. Antimicrobial covariates had the same time-varying effect, and stool vs rectal the same non-time varying effect as the linear Shannon diversity model.

Logistic regression: AMR gene presence

Modelling presence or absence of AMR gene used the same linear predictor as above, but a logistic regression model and logit link function

Priors were the same as the linear model except the intercept (β0) was set to a mean of 0. Antimicrobial covariates had the same time-varying effect, and stool vs rectal the same non-time varying effect as the linear Shannon diversity model.

Fitting and simulating from the models

Time was scaled by the standard deviation. All models were run with 4 chains for 1000 iterations with a warmup of 500 iterations. Convergence was assessed by the Gelman-Rubin statistic being close to 1, and inspection of traceplots. Posteriors were summarised using median and 95% credible intervals, unless otherwise stated. For simulations, covariate values were fixed and the whole posterior (excluding warmup) used to generate predictions of the population mean outcomes of interest (i.e. ignoring within-participant correlations), which were then summarised with medians and 95% quantiles, unless otherwise stated.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Metadata for the participants from whom samples were collected an including antimicrobial exposures are available via the blantyreESBL v1.4.1 R package30. Reads were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive, under project accession PRJEB86881; accession numbers of individual samples are in Supplementary Data, linked back to metadata by the lab_id variable.

Code availability

Code to replicate the analysis is available at the project GitHub repo https://github.com/joelewis101/deep_sequencing and mirrored at Zenodo. (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17296033).

References

WHO Regional Office for Europe. Antimicrobial Stewardship Interventions: A Practical Guide (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2021).

Tedijanto, C., Olesen, S. W., Grad, Y. H. & Lipsitch, M. Estimating the proportion of bystander selection for antibiotic resistance among potentially pathogenic bacterial flora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, E11988–E11995 (2018).

Evans, L. et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit. Care Med. 49, e1063 (2021).

Gibson, M. K. et al. Developmental dynamics of the preterm infant gut microbiota and antibiotic resistome. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16024 (2016).

Schwartz, D. J., Langdon, A. E. & Dantas, G. Understanding the impact of antibiotic perturbation on the human microbiome. Genome Med 12, 82 (2020).

Lebeaux, R. M. et al. The infant gut resistome is associated with E. coli and early-life exposures. BMC Microbiol. 21, 1–18 (2021).

Oldenburg, C. E. et al. Gut resistome after oral antibiotics in preschool children in Burkina Faso: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 70, 525–527 (2020).

Reyman, M. et al. Effects of early-life antibiotics on the developing infant gut microbiome and resistome: a randomized trial. Nat. Commun. 13, 893 (2022).

Palleja, A. et al. Recovery of gut microbiota of healthy adults following antibiotic exposure. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 1255–1265 (2018).

Suez, J. et al. Post-antibiotic gut mucosal microbiome reconstitution is impaired by probiotics and improved by autologous FMT. Cell 174, 1406–1423.e16 (2018).

Fredriksen, S., de Warle, S., van Baarlen, P., Boekhorst, J. & Wells, J. M. Resistome expansion in disease-associated human gut microbiomes. Microbiome 11, 1–11 (2023).

Raymond, F. et al. The initial state of the human gut microbiome determines its reshaping by antibiotics. ISME J. 10, 707–720 (2016).

Murray, C. J. et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

Lewis, J. M. et al. A longitudinal, observational study of etiology and long-term outcomes of sepsis in Malawi revealing the key role of disseminated tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 74, 1840–1849 (2022).

Lewis, J. M. et al. Colonization dynamics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales in the gut of Malawian adults. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 1593–1604 (2022).

Musicha, P. et al. One Health in Eastern Africa: No barriers for ESBL producing E. coli transmission or independent antimicrobial resistance gene flow across ecological compartments. 2024.09.18.613694 https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.18.613694 (2024).

Gschwind, R. et al. ResFinderFG v2.0: a database of antibiotic resistance genes obtained by functional metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W493–W500 (2023).

Anthony, W. E. et al. Acute and persistent effects of commonly used antibiotics on the gut microbiome and resistome in healthy adults. Cell Rep. 39, 110649 (2022).

Zaura, E. et al. Same exposure but two radically different responses to antibiotics: resilience of the salivary microbiome versus long-term microbial shifts in feces. mBio 6, e01693–15- (2015).

Willmann, M. et al. Distinct impact of antibiotics on the gut microbiome and resistome: a longitudinal multicenter cohort study. BMC Biol. 17, 1–18 (2019).

Peto, L. et al. The impact of different antimicrobial exposures on the gut microbiome in the ARMORD observational study. eLife 13 (2024).

Cocker, D. et al. Investigating risks for human colonisation with extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae in Malawian households: a one health longitudinal cohort study. medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.22278508 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Differential responses of the gut microbiome and resistome to antibiotic exposures in infants and adults. Nat. Commun. 14, 8526 (2023).

Ng, K. M. et al. Recovery of the gut microbiota after antibiotics depends on host diet, community context, and environmental reservoirs. Cell Host Microbe 26, 650–665.e4 (2019).

Panulo, M. et al. Assessment of infrastructure, behaviours, and user satisfaction of guardian waiting shelters for secondary level hospitals in southern Malawi. PLOS Glob. Public Health 4, e0002642 (2024).

Temkin, E. et al. The natural history of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales: progression from carriage of various carbapenemases to bloodstream infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. ciae 110, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciae110 (2024).

Woodworth, M. H., Hayden, M. K., Young, V. B. & Kwon, J. H. The role of fecal microbiota transplantation in reducing intestinal colonization with antibiotic-resistant organisms: the current landscape and future directions. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 6, ofz288 (2019).

Lewis, J. M. et al. Genomic analysis of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli colonising adults in Blantyre, Malawi reveals previously undescribed diversity. Microb Genom. 9 (2023).

Lewis, J. M. et al. Genomic and antigenic diversity of colonizing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates mirrors that of invasive isolates in Blantyre, Malawi. Microb. Genomics 8, 000778 (2022).

Lewis, J. joelewis101/blantyreESBL: 1.4.1. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10053362 (2023).

Uritskiy, G. V., DiRuggiero, J. & Taylor, J. MetaWRAP—a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome 6, 1–13 (2018).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20, 1–13 (2019).

Nurk, S., Meleshko, D., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 27, 824–834 (2017).

Jain, C., Rodriguez-R, L. M., Phillippy, A. M., Konstantinidis, K. T. & Aluru, S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9, 5114 (2018).

Chklovski, A., Parks, D. H., Woodcroft, B. J. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM2: a rapid, scalable and accurate tool for assessing microbial genome quality using machine learning. Nat. Methods 20, 1203–1212 (2023).

Feldgarden, M. et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog facilitate examination of the genomic links among antimicrobial resistance, stress response, and virulence. Sci. Rep. 11, 12728 (2021).

Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477 (2012).

Lees, J. A. et al. Fast and flexible bacterial genomic epidemiology with PopPUNK. Genome Res. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.241455.118 (2019).

Argimón, S. et al. Microreact: visualizing and sharing data for genomic epidemiology and phylogeography. Microb. Genomics 2, e000093 (2016).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (clinical PhD studentship to JL, 109105z/15/a, and 206545/Z/17/Z, the core grant to the Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Programme) and NIHR (NIHR200632). JL was supported by a NIHR academic clinical lectureship (CL-2019-07-001). E.C.-O. and A.C.D. are affiliated with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Protection Research Unit in Gastrointestinal Infections at the University of Liverpool, in partnership with the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), and in collaboration with the University of Warwick. E.C.-O. and A.C.D. are based at the University of Liverpool. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, or the UK Health Security Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.C.-O.: Conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing, visualisation, supervision; V.P.: Formal analysis, investigation, writing; M.M.: data curation, investigation, writing; J.M.: conceptualisation, resources, writing; A.D.: conceptualisation, methodology, resources, writing, supervision; N.A.F.: conceptualisation, methodology, resources, writing, supervision, funding acquisition; J.M.L.: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing, visualisation, supervision, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Katariina Parnanen, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cunningham-Oakes, E., Price, V., Mphasa, M. et al. Quantifying the bystander effect of antimicrobial use on the gut microbiome and resistome in Malawian adults. Nat Commun 17, 954 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67677-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67677-6