Abstract

Tuning the strength of spin-orbit interaction (SOI) is pivotal for developing next-generation spintronic and quantum devices. Proximity-induced SOI is a promising route toward this goal, but its experimental characterization with resolution in k-space using ARPES remains challenging. We advance previous ARPES investigations of proximity-induced SOI in graphene-based systems to transition-metal dichalcogenides (MoSe2) in proximity to an amorphous overlayer of high-Z metal (Pb) whose disordered nature suppresses k-space mismatch at the interface. The use of soft-X-ray ARPES is instrumental for accessing MoSe2 beneath the Pb layer. We introduce an approach to interpret the experimental data based on the identification of local SOI-derived band gaps—SOI hotspots—where the intrinsic SOI contribution, arising from the SOI field transfer from the overlayer to the host, is isolated from competing effects such as scalar (non-SOI) hybridization, interlayer interactions and Rashba-type splitting. We find that the proximity to Pb strongly enhances the intrinsic SOI as manifested by k-dependent increase of the band splitting in the SOI hotspots by up to several tens of meV. Tunability of this effect via Pb coverage provides versatile means for tailoring SOI to specific spintronic and quantum applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spintronics is based on novel operational principles that utilise the electron spin degree of freedom to process information, offering a greater functional diversity with respect to conventional electronics1,2,3. Spintronic devices are also expected to be the leading contenders for the next-generation devices, which will boast reduced power consumption, increased memory density, and processing capabilities. Typically, in such spintronic devices, spin polarisation is controlled either by magnetic layers or via spin-orbit (SO) interaction (SOI)4.

SOI is known to play a key role in a variety of novel functionalities that distinguish materials used for spintronics. Depending strongly on the SOI strength, these functionalities include spin-orbit torques3, the anomalous Hall effect5, anisotropic magnetoresistance6, and spin relaxation7 in magnetic materials. They also encompass interconversion between nonequilibrium charge and spin currents8,9 as well as the direct and inverse Rashba–Edelstein effects in non-magnetic materials10,11. Strong SOI is a key requirement for forming topologically protected electronic states, including two-dimensional (2D) surface states in topological insulators12,13 and three-dimensional (3D) states such as nodal lines and chains in Dirac and Weyl semimetals14,15. Pivotal for detailed investigation of such states has been angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy (ARPES) as a unique experimental technique resolving electron states in electron momentum (k). Beyond spintronics, tunable SOI is vital for engineering exotic quantum states such as Majorana fermions, envisioned for qubits where superconductors are interfaced with strong-SOI semiconductors16,17. Here, SOI provides topological protection against decoherence from low-energy excitations18. Therefore, identifying practical and controllable ways to tune SOI strength is critical for advancing functional materials for next-generation spintronic and quantum devices.

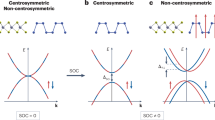

The SOI strength can be increased by interfacing materials with high-Z atoms. This so-called proximity effect manifests as an enhancement of the SO splitting (ΔSO) in the host band structure. We can differentiate two contributions to the proximity effect19,20,21,22: (1) Rashba-type SOI, which introduces energy splitting proportional to the Rashba parameter (αR), which, in the heuristic form, is written as \(\alpha_{\rm{R}} \sim \lambda_{0}|\langle \psi_{0} |\frac{\partial V}{\partial z}| \psi_{0} \rangle | \). Here, λ0 is the SOI constant of the host atoms, ψ0 the host wavefunction, and \(\frac{\partial V}{\partial z}\) the potential gradient. Proximity to the external atoms can render αR non-zero in two different ways, either by a structural distortion causing asymmetry of ψ0 (often referred to as structure-induced Rashba effect) or by imposing an external electric field on top of the host \(\frac{\partial V}{\partial z}\) (field-induced Rashba effect). In either case, the Rashba-type SOI can be identified based on the characteristic doublet of band dispersions with opposite spin, which are split in k-space23; (2) the so-called intrinsic SOI, where ψ0 hybridizes with that of the high-Z external atom (ψ1), providing a strong SOI field. In this case, energy splitting is proportional to the proximity-enhanced SOI strength (λeff), which, in a simplified form of the second-order perturbation theory, is written as \(\lambda_{\rm{eff}} \sim \lambda_{0}+ \frac{| \langle \psi_{0} |H_{1}^{\rm{SOI}}| \psi_{1}\rangle|^{2}}{E_{0} - E_{1}}\), where H1SOI and E1 are the spin-orbit Hamiltonian and energy level of the external atoms, respectively. While several studies have reported proximity-induced SOI, clear experimental identification of the intrinsic contribution remains rare. However, under favourable hybridization conditions and high-Z external atoms, introducing a strong SOI field, the intrinsic contribution should dominate the proximity effects. An insightful theoretical discussion of the Rashba-type vs intrinsic SOI, tailored to graphene-based materials in proximity to transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs), can be found in refs. 19,20,21,22.

Most experimental studies of proximity effects focused on graphene-related systems. For example, numerous ARPES studies of graphene grown on various 5d metal substrates such as Au, Ir, and Pt24,25,26,27,28,29 have detected tangible structure-induced Rashba splitting co-existing with band gaps opening due to scalar (non-SOI) hybridization of graphene with substrate states. However, the proximity-induced intrinsic SOI could not be convincingly disentangled from Rashba-type effects. An alternative strategy to manipulate SOI in graphene is its interfacing to TMDCs. Magnetotransport measurements30 and scanning tunneling spectroscopy31 identified the Rashba and the intrinsic valley-Zeeman terms in the proximity-induced SOI in such heterostructures, with magnitudes of the order of 10 meV and 2 meV, respectively. Such effects have also been observed in heterojunctions MoSe2/EuS32, graphene on WS233 and other TMDCs34, and bilayer graphene on MoS235 and WSe236, with strong impact on spin-relaxation anisotropy33,37. Inversion symmetry can also be broken by applying an out-of-plane electric field, but even at several V/nm, the resulting spin splitting remains at the few-meV level10,21. In any case, the gapless nature of pristine graphene questions its utility for transistor applications.

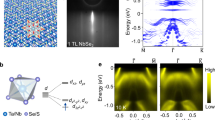

An alternative platform to manipulate the SOI effects can be the diverse family of TMDCs, composed of weakly van der Waals (vdW) bonded atomic layers38,39. Various band structure patterns, including semiconductor band gaps, make these materials promising candidates for novel microelectronic and spintronic devices. One such TMDC is MoSe2, an indirect band gap semiconductor crystallising in its thermodynamically stable 2H-phase shown in Fig. 1a, b. Its trigonal single-layer structure denies inversion symmetry, allowing intrinsic SOI to cause energy- and k-dependent splitting of the valence bands of the order of ~200 meV. Owing to this distinct splitting, MoSe2 is an ideal host for ARPES experiments on proximity-induced modulation of SOI. Theoretically, Rashba-type SOI spin splitting has been predicted for PtSe2/MoSe2 heterostructures40. Magnetic proximity effects in graphene-based materials and TMDCs32,40,41,42,43 are beyond the scope of this work.

Here, we extend previous ARPES studies of proximity-induced SOI from graphene-based materials as receivers of the SOI field to a new class of materials, TMDCs (specifically, 2H-MoSe2). In contrast to previous epitaxial systems, the high-Z overlayer (Pb) is amorphous, which avoids k-space mismatch at the interface, otherwise limiting proximity effects. Methodologically, we introduce an approach based on the identification of isolated SOI-derived band gaps—SOI hotspots—that allows separation of the intrinsic SOI contribution, arising from the SOI field transfer, from competing effects such as scalar hybridization and Rashba-type splitting. Applying this framework to the MoSe2/Pb interface, we observe proximity-induced enhancement of intrinsic SOI by several tens of meV tunable via the Pb thickness. Exceeding the effects reported for graphene-based systems, this enhancement reflects a genuine intrinsic proximity mechanism driven by hybridization between Mo d-orbitals and Pb sp-orbitals, which imposes a strong SOI field on MoSe₂. Our experiments use soft-X-ray ARPES at photon energies (hv) around 800 eV, where large photoelectron inelastic mean free path (IMFP) enables access to MoSe2 beneath the Pb layer and also sharpens the intrinsic out-of-plane momentum resolution (Δkz) for precise navigation in 3D k-space44,45,46,47.

Results and discussion

SO splitting hotspots in the valence band of bare MoSe2

Similarly to other TMDCs48,49,50,51, the valence band (VB) of MoSe2 is formed by the metal states (Mo 4d) hybridized with the chalcogen ones (Se 4p). The electronic structure of MoSe2 critically depends on the number of layers upon their pile-up from one monolayer to the bulk51. The corresponding evolution of the electronic structure is driven by a modification in the hybridization between the out-of-plane Se 3pz orbitals, in turn interacting with the Se 4pxy in-plane orbitals and with the Mo 4d ones inside the layers. This hybridization is responsible for the interlayer interaction in bulk MoSe2 and quantum confinement in its heterostructures. Furthermore, in systems with an odd number of MLs lacking the inversion centre, this hybridization modulates the Rashba-type SO splitting at the Γ-point23,51. A particular focus of previous works has been the local VB maximum in the K-point of the monolayer through bulk MoSe2, see the corresponding 2D and 3D Brillouin zones (BZs) in Fig. 1c. It was shown that the band splitting (Δbs) at this point arises mostly from the interlayer interaction with a smaller contribution from the intrinsic SOI and, in the monolayer limit, from the strong SOI caused by the absence of the inversion centre51,52,53.

Our DFT calculations for bulk MoSe2 without and with SOI are shown in Fig. 2a, b for the in-plane directions and in (c,d) for the out-of-plane ones. The ГA direction in (c,d) is unfolded to the Г0AГ1 one, whose length is the double out-of-plane size of the 3D-BZ. This double-BZ periodicity reflects the actual periodicity of the ARPES response of 2H-MoSe2 related to a non-symmorphic space group of its crystal structure54,55. Hereinafter, energy scale of all theoretical and experimental data is set relative to the global VB maximum (VBM) in the Г1-point.

a, b In-plane symmetry directions, and c, d out-of-plane ones without and with SOI (the ГA direction unfolded to the double out-of-plane size of the 3D-BZ). The energy scale hereinafter is relative to the VBM in the Г1-point. The band splitting in the K-point (green circle) is largely due to the interlayer interaction, and those in the H- and Г1-points (red and blue circles, respectively) are the two hotspots where the splitting is predominated by SOI.

The SOI effects in the band structure of MoSe2 can be distinguished in Fig. 2 by comparing (a) with (b). At the K-point maximum (green circle), Δbs increases only slightly when SOI is added. At this point, it is therefore controlled mostly by the interlayer interaction with only a weak contribution of SOI. The H-point, which differs from the K only in kz, is completely different, however. The bands near EF at this point (red circle) split only when SOI is activated. Therefore, in contrast to the sister K-point, Δbs at this point results solely from strong SOI. This makes the H-point the ideal hotspot for analysis of SOI and its modulation driven by the proximity effect. Another band structure point where the SOI effects are critical is the band manifold at binding energy (EB) around −1 eV at the Г-point (blue circle). Whereas without SOI this manifold is almost degenerate in the Г-point, it spills over an energy interval of ~250 meV when SOI is on. The unfolded band structures along Г0AГ1, in (c) and (d), show that the point most relevant for our analysis is Г1, where the SOI-split doublet is maximally separated in energy from other bands. This is therefore the second hotspot of SOI. Yet another hot spot might in principle be found at the K-point at EB around −3.5 eV, but the corresponding Δbs will be hidden in the spectral peak broadening which increases away from EF because of decreasing hole lifetime. A key property of the SOI hotspots, as we will see below, is that the band gap magnitude is insensitive to scalar (non-SOI) band hybridization and Rashba-type spin splitting, making them ideal for isolating the intrinsic proximity effects.

Experimental valence band of bare MoSe2

To identify the SOI hotspots in the experimental ARPES data, we will first establish the experimental 3D band structure of bare MoSe2. Figure 3a shows the (kx,kz) out-of-plane iso-EB maps of ARPES spectral intensity taken at EB = 0 and −0.65 eV under variation of hv. A dispersive periodic pattern along kz through the consecutive Г-points manifest 3D electronic states in this k-space region, with the observed kz periodicity of the double out-of-plane size of the 3D-BZ reflecting the non-symmorphic space group of 2H-MoSe2. The nearly non-dispersive lines through the K-points manifest nearly 2D states consistent with the calculations in Fig. 2c, d. The conversion from hv to kz used the free-electron approximation for the final states (corrected for the photon momentum) with an empirical inner potential V0 of 14 eV. Figure 3b shows an additional sequence of (kx,kz) in-plane maps of the ARPES intensity for a few EB values, which were measured at hv = 737 eV corresponding to the Г1 point in the unfolded band structure, Fig. 2c. The map for EB = −0.65 eV, in particular, shows up a hexagonal pattern of circles around the Г1-points and closed trigonal contours around the K-points, with the latter split because of the aforementioned interlayer splitting. This effect is in agreement with our calculations in Fig. 2b as well as with the previous theoretical and experimental data35,51,56,57.

a Out-of-plane maps of ARPES intensity in the hv range 700–850 eV, taken for kx oriented along the Г1K direction of the 3D-BZ (Fig. 1c) at EB = 0 and −0.65 eV. b The in-plane maps with the same kx orientation at Eb = 0, −0.3, −0.65 and −1.85 eV. These maps were taken at hv = 737 eV, corresponding to the Г1KM plane of the 3D-BZ. The hexagonal symmetry and the trigonal warping around the K-points are seen.

The experimental out-of-plane dispersion of the valence states is represented in Fig. 4a, which shows the ARPES intensity maps as a function of EB and kz measured at kx = 0 Å−1 (along ГA) and 1.6 Å−1 (along KH) in the hv range from 700 eV to 850 eV. Along ГA, the two bands with the strongest kz-dispersions are formed by the bonding Se 4pz and antibonding Se 4pz* out-of-plane orbitals (centered at EB ~ −6.3 eV and −2.5 eV, respectively) which overlap across the vdW gap. The dispersing band near the VBM is formed by the Mo 4d orbitals located inside the atomic layers, and its kz-dispersion manifests an interlayer cross-talk of these orbitals mediated by their hybridization with the Se 4pz* ones48. For the ГA direction, the experimental dispersions run the indicated sequence through the Г-points (the even indices correspond to Г0 and odd to Г1) separated by the A-ones. The observed kz periodicity, following the double-BZ periodicity, agrees with the calculated band dispersions unfolded to Г0AГ1 in Fig. 2c, d. For the KH direction, the experimental dispersions are more flat, and the double-BZ periodicity is less clear. The experimental out-of-plane ARPES intensity as a function of EB and kx along the ГK direction is represented in Fig. 4b. The left one was measured at hv = 737 eV (the same as used for the in-plane iso-EB maps in Fig. 3b), which brings to kz at the Г1-point. Due to small variations of kz with kxy in the soft-X-ray range, this map corresponds almost exactly to the Г1K direction of the 3D-BZ. The right map was measured at 715 eV, bringing kz to the A-point, and corresponds to AH.

a Out-of-plane ARPES intensity map as a function kz in the hv range 700–850 eV along the ГA and KH directions. b In-plane ARPES intensity images measured at hv = 737 eV (left) and 715 eV (right), where k runs along the Г1K and AH directions of the 3D-BZ. c, d Zoom-ins of b near the Г1- and H-hotspots (marked) with the corresponding EDC and −d2I/dE2 > 0 plots in these points. The horizontal dashes on the −d2I/dE2 > 0 plots mark the corresponding Δbs values, in this case identified with ΔSO.

We will now focus on Δbs at the Г1- and Н-hotspots, which are central for our analysis of SOI. Figure 4c, d shows zoom-ins of the ARPES data from (b) around these hotspots. The experimental bands at the Г1- and Н-hotspots are clearly split, which is also evident in the corresponding Energy-Distribution Curves (EDCs) plotted next to the zoom-ins. The Δbs values were determined from the negative second derivative of these EDCs (−d2I/dE2 > 0, with the unphysical negative values set to zero) shown to the right. These values, in our case reflecting almost pure ΔSO, were found as 221 ± 2 meV in the Г1-hotspot and 210 ± 2 meV in the H-one. They are consistent with our DFT calculations with SOI in Fig. 2b. We note that the H-point differs from the K-one, where Δbs is driven primarily by the interlayer interaction, only by its kz. The small intrinsic Δkz achieved in the soft-X-ray energy range is quintessential to distinguish these two points in the experimental spectra45,46,47. Indeed, according to the TPP-2M formula58,59, the IMFP in our kinetic-energy range is ~15 Å. This gives Δkz ~ 0.07 Å−1, which is sufficiently sharp relative to the kz separation of the K- and H-points of 0.23 Å−1. We notice, however, that while our calculations predict Δbs to vary from ~290 to 200 meV between the K- and H-points, the experiment finds it stay at 210 meV, essentially constant within the experimental accuracy.

Electronic structure evolution with Pb thickness

To study the proximity-induced SOI in MoSe2, we deposited Pb in-situ on its cleaved crystalline surface, and tracked the evolution of Δbs at the two SO-hotspots versus the overlayer thickness. As Pb does not wet the MoSe2 surface, the depositions from a thermal evaporator were carried out at the sample temperature 14 K to ensure formation of a continuous amorphous overlayer, essential for our study. The cumulative depositions were each followed by X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) and ARPES measurements. The XPS spectra of the Pb 4f and Mo 3d core-level peaks, Fig. 5a, have shown a monotonous increase of their intensity ratio upon the Pb deposition corresponding to a linear increase of the overlayer thickness with the deposition time without formation of islands. Here, a thickness of 2.86 Å corresponds to one effective monolayer (ML) of Pb60. Importantly, the Mo 3d and Se 3d peaks have not shown any noticeable lineshape changes upon the deposition, confirming the absence of chemical reactions between the Pb and MoSe2 or formation of new chemical environments of the interfacial atoms. This observation also excludes any intercalation of Pb atoms into MoSe2 as well as layer-breaking reactions61.

a XPS overview spectra at hv = 1000 eV showing the Mo 3d and Pb 4f core levels depending on the cumulative Pb thickness. b In-plane ARPES images along the Г1K and AH directions of the 3D-BZ for a Pb thickness of 0.25 nm, and c these images in red colorscale overlaid with the bands of bare MoSe2 (blue). Besides an increase of the incoherent background, broadening of the spectral peaks and their marginal k-dependent energy shifts, the Pb overlayer does not much affect the MoSe2 electronic states.

ARPES data in the VB region of MoSe2 under the Pb overlayer is represented in Fig. 5b as measured for an overlayer thickness of 0.25 nm (corresponding to ~1 ML). The full dataset measured along the ГKMK and AHLH lines through the whole series of Pb depositions is represented in the Supporting Information (SI) in Fig. SI1. We notice a significant incoherent background coming from the amorphous Pb layer (Fig. SI2) and increased broadening of the spectral peaks due to partial disorder induced into MoSe2 by the Pb atoms. Figure 5c shows the data from (b) overlaid with the bands of bare MoSe2 from Fig. 4b in the curvature representation62. The observed energy shifts are k-dependent and are of the order of 100 meV and less. Their main cause is that the electron density introduced by Pb atoms mediates the scalar orbital hybridization63 in MoSe2; another effect, discussed below, is the SOI field. Besides these effects, the band structure of MoSe2 stays quite resilient under the Pb overlayer, without formation of additional coherent electronic states. Also notable in the spectra is the Fermi edge from the Pb overlayer, best seen in angle-integrated spectra in Fig. SI1. Owing to the low density of Pb states in this energy region, the Fermi edge clearly identifies only at higher Pb coverages. It is located at ~400 meV above the VBM, varying with the Pb thickness within ±50 meV. This variation is less expected because most metal-TMDC interfaces show pinning of the Fermi level to the VBM, resulting from formation of intermetallic compounds at the interface64,65. Aligned with the absence of the core-level changes and resilience of the buried MoSe2 band structure, this behaviour is attributed to low chemical activity of Pb on MoSe2.

In order to identify the SOI modulation due to the proximity effects, we will now turn to the evolution of the band structure in the Г1- and H-hotspots upon increase of the Pb thickness. Following the in-plane ARPES data around these hotspots for bare MoSe2 in Fig. 4e, f, the zoom-ins in Fig. 6a–d show the corresponding EDC and −d2I/dE2 > 0 data for MoSe2 covered with 0.25 and 0.5 nm of Pb, equivalent to ~1 and 2 MLs, respectively (the full dataset compiling all Pb coverages is presented in Fig. SI3). The −d2I/dE2 peaks signal a significant increase of Δbs in the Г1-hotspot from 221 meV in bare MoSe2 to 231 ± 2 and 252 ± 4 meV for the 0.25- and 0.5-nm thickness of the Pb overlayer, and in the H-hotspot from 210 meV to 250 ± 2 and 270 ± 2 meV.

ARPES data for the Г1- and H-hotspots (a–d respectively) for the 0.25- and 0.5-nm thickness (a–d) of the Pb overlayer, represented in the same way as the data on bare MoSe2 in Fig. 4c, d. The increase of Δbs upon the deposition of Pb identifies the increase of SOI in MoSe2 caused by the proximity effect.

Importantly, the Δbs modulations in the SOI hotspots are unaffected by scalar hybridization of the Pb states with MoSe2, which contribute to the marginal k-dependent energy shifts63 noticed in Fig. 5c. This is clear from the fact that the electron wavefunctions above and below the SOI-induced band gaps have the same spatial (spin-independent) parts and should therefore exhibit almost the same energy shifts upon the scalar hybridization, leaving Δbs the difference unchanged. The observed increase of Δbs is significantly stronger than for graphene also interfaced to high-Z metals24,25,26,27,28 or TMDCs33,34,35.

We interpret the observed increase of Δbs in the SOI hotspots as due to the intrinsic proximity effect caused by the transfer of the strong SOI field from Pb to MoSe2. Its mechanism is the hybridization of the Pb wavefunctions with the Mo-derived ones across the Pb/MoSe2 interface, mediated by the Se-derived wavefunctions in the top layer of MoSe2. Below, we ascertain this interpretation based on assessment of alternative scenarios.

The whole body of our experimental data on Δbs as a function of the Pb thickness is compiled in Fig. 7. It runs over the Г31-, H30- and H31-hotspots from the experimental kz dependence in Fig. 4a, b for the Pb-layer thickness from 0 to ~2.5 nm (also included here is the Г32-point, measured at hv = 778 eV and corresponding to Г0 in Fig. 2d, although Δbs in this point is affected by hybridization with the Se 4pz* band). We see that as the Pb thickness piles up, the experimental Δbs gradually increases and saturates at about two full MLs. In the H-hotspots Δbs saturates at ~270 meV (increasing by ~60 meV compared to pristine MoSe2), and in the Г1-hotspot at ~250 meV (increasing by ~30 meV).

Interestingly, Δbs continues to increase beyond 1 ML coverage, despite the short-range nature of SOI. This behavior can be attributed to Pb atoms adsorbing on already covered regions and leaving uncovered areas accessible to atoms from the continuing Pb. Also, we cannot rule out an amplification of the interfacial SOI field from interactions among Pb atoms within the deposited film. The slight reduction of Δbs for the Г31 and Г32 points at the Pb thickness around 1 nm, though within the confidence intervals, could be attributed to a complex band hybridization pattern near these k-points. Evidently, the key parameter to control the proximity-induced ΔSO is the Pb coverage, mostly in the sub-ML range.

Assessment of alternative scenarios

We have also analysed alternative scenarios for the observed modulation of Δbs in the SOI hotspots. The simplest possibility might be a chemical reaction between Pb and MoSe₂. However, our XPS spectra show no evidence for new chemical environments formed at the interface, and the ARPES data reveal no formation of new electron states. This is consistent with the absence of the Fermi-level pinning to the VBM, indicative of the formation of intermetallic compounds64,65. These observations allow us to rule out chemical-reaction origins of the Δbs modulation.

Next, we considered whether the Δbs modulation could arise from Rashba-type SOI. Critically, the experimental bandstructure in Fig. 6 shows no sign of the characteristic k-space splitting of the bands in the SOI hotspots. Given the large increase of Δbs, such splitting would be also large compared to the experimental k-resolution—yet not observed. As additional arguments to rule out the Rashba-type SOI, we will now analyze its structure-induced and field-induced mechanisms.

Two considerations argue against the structure-induced Rashba-type SOI. First, it would typically require a well-defined interfacial asymmetry in the out-of-plane direction, as found in crystalline heterostructures. In contrast, the Pb overlayer in our system is amorphous and lacks long-range structural order, making such asymmetry unlikely. The second argument aligns with the insensitivity of the band gap in the SOI hotspots to the scalar hybridization, discussed above. Owing to the nearly identical spatial parts of the wavefunctions at the edges of the SOI-induced band gaps, the Rashba effect would affect them equally, leaving Δbs at most unchanged, in contrast to our experiment.

To assess the role of field-induced Rashba SOI, we performed band structure calculations for MoSe2 under a static out-of-plane electric field up to 1 V/nm, an upper-bound estimate for the field potentially induced by the Pb overlayer. Our theoretical results in Fig. SI4-1 show that the field lifts the spin degeneracy of the bands, which we classify by their dominant out-of-plane spin component Sz. In this context, Δbs is defined as the energy separation between the centers of the spin-split doublets, marked by green dashes at the K- and H-points. Fig. SI4-2 shows that Δbs at the H-hotspot stays constant within a few μeV over the entire field range. This behavior contrasts to our experimental increase of ~60 meV upon Pb deposition. A similar lack of field effect is found at the Γ1-point, again contradicting the ~30 meV increase observed in the experiment. These findings allow us to rule out any significant contribution from field-induced Rashba SOI to the experimental Δbs modulation. We note in passing that direct verification of the field effect in ARPES experiments66 presently stays challenging because of overwhelming technical difficulties such as gate leakage currents.

Lastly, the clearest demonstration of the role of strong SOI field in the observed proximity effect has come from a control experiment in which we replaced the Pb deposition by Al, an element having comparable electronic structure but much lower atomic SOI. The resulting ARPES bandstructure is presented in Fig. SI5. Larger chemical activity of Al compared to Pb is evidenced in larger incoherent spectral background. Strikingly, no changes of Δbs in either SOI hotspot were detected upon the Al deposition. The whole body of our results, taken together and critically compared against alternative scenarios, confirms that the observed Δbs modulation is a genuine intrinsic proximity effect, arising from the transfer of a strong SOI field from Pb into MoSe₂.

In summary, we have demonstrated a SOI proximity effect in MoSe2 induced by interfacing it with a high-Z element, Pb. This work extends proximity studies from graphene-based materials as receivers of the SOI field to TMDCs, establishing this class of materials as a promising platform for SOI engineering. In contrast to previous epitaxial systems, we employ an amorphous Pb overlayer, which circumvents k-space mismatch at the interface to enable efficient SOI transfer. Methodologically, we introduced an approach based on identifying local SOI-derived band gaps. At their edges, the spatial parts of the wavefunctions are nearly identical and thus respond equally to scalar hybridization and Rashba-type effects, effectively isolating the intrinsic SOI contribution due to the SOI field transfer into the host.

Applying this framework to the MoSe2/Pb interface, we have found the SOI hotspots in the Γ1- and H-points of the 3D-BZ. The Pb overlayer enhances Δbs in these points by up to ~30 meV and ~60 meV, respectively, saturating above 2 MLs. These values significantly exceed those observed in graphene-based systems and fall into the energy range relevant for spintronic applications. Owing to the intrinsic nature of the SOI hotspots, these enhancements manifest the profound intrinsic proximity effect resulting from hybridization of Mo d-orbitals in the top MoSe2 layer to the Pb sp-orbitals, transferring a strong SOI field into the host. We have confirmed this proximity mechanism by critical assessment of all other possible effects, including chemical reactions, structure- or field-induced Rashba splitting, all of which are ruled out by experimental or theoretical evidence. A control experiment, where changing Pb to the low-Z element Al has completely extinguished the SOI proximity effect, has verified our conclusion. Instrumental for our study has been the use of soft-X-ray ARPES, whose large probing depth was essential to penetrate through the Pb film to MoSe2, and the sharp intrinsic kz definition essential to isolate the SOI hotspots in 3D k-space.

Our results establish a clear strategy for manipulating intrinsic SOI in TMDCs via proximity to high-Z elements. Their amorphous overlayers eliminate potential effects of k-space mismatch between the proximitized wavefunctions at the interface. This strategy naturally extends to TMDC intercalated with high-Z atoms. Concerning the Pb/MoSe₂ interface specifically, we find its device perspective attractive owing to the absence of Fermi-level pinning, consistent with weak chemical interaction and favorable Schottky contact behavior.

In a broader perspective, our demonstration of proximity-induced modulation of the intrinsic SOI is not only interesting for fundamental solid-state physics, it also illustrates a viable approach for tuning spin-related properties via heterostructure design. For example, PbS/MoSe₂ heterostructures could enable similar SOI control while preserving semiconducting behavior, making them suitable for integration into van der Waals transistors. The use of amorphous overlayers simplifies fabrication compared to epitaxial growth. More broadly, combining materials with distinct electronic properties (such as superconductivity and ferromagnetism) offers a route to engineer multifunctional systems for applications in spintronics, quantum technologies, and beyond.

Methods

ARPES measurements. Synchrotron-radiation ARPES experiments over a series of four 2H-MoSe2 bulk crystals (HQ Graphene) were performed at the SX-ARPES endstation45 of the ADRESS beamline67 at the Swiss Light Source (Villigen, Switzerland). The spectra were recorded in the hv range 700–850 eV with circularly polarised light, using the hemispherical analyzer PHOBOS-225 (SPECS GmbH) at a combined (beamline + analyzer) energy resolution of ~100–120 meV. The samples were cleaved in-situ and measured at 14 K in a vacuum better than 2 ⋅ 10−10 mbar.

A particular concern in acquisition of the hv-dependent ARPES data was a slight hv-dependent charging of pristine 2H-MoSe2 crystals and systematic interpolation errors of the JENOPTIC monochromator energies68. To solve this problem, acquisition of the ARPES images for every next hv value was followed by a short measurement of the Mo 3d core-level. The energy scale in these images was then corrected by the core-level energy shift relative to its position at hv = 737 eV, where kz falls in the VBM, see Fig. 4b.

If not stated otherwise, all figures in the main text and SI represent the raw ARPES intensity, including the incoherent background coming from the Debye-Waller factor and the amorphous Pb overlayer. Reproducibility of the ARPES data measured from different 2H-MoSe2 crystals is illustrated by the EDCs in the SOI hotspots shown in Fig. SI6. Conversion of the photoelectron kinetic energies and emission angles to the k values included the photon momentum correction45. The Δbs values were determined from the second derivative of the EDCs, and their confidence-interval halfwidths calculated by multiplying the standard deviation over four crystals by the Student’s t-factor for a confidence interval of 75%69.

Pb deposition. The Pb overlayers were deposited at the sample temperature 14 K. Assuming their homogeneity, the thickness (d) was estimated based on the attenuation of the Mo 3d and Se 3d core levels relative to bare MoSe2 expressed as \(I/{I}_{0}={e}^{-d/{\lambda }_{{Pb}}}\), where λPb is the IMFP in Pb. According to the TPP-2M formula58,59, λPb at hv = 1000 eV equals ~19 Å for Mo 3d and ~22 Å for Se 3d. The calibrated deposition rate was ~6 Å/min.

DFT calculations. Electronic band structure calculations for bulk MoSe2 with and without SOI were carried out within the density functional theory (DFT) using the linear muffin-tin orbital (LMTO) method70. We use the fully relativistic PY LMTO computer code71. Self-consistent calculations have been performed with the experimental lattice parameters and within the local density approximation (LDA).

Data availability

The raw data generated in this study, sorted in figure order, have been deposited in the database figshare.com under https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30631352.

Code availability

The software MATools for ARPES data processing, including k-space conversion, extraction of various k-space cross-sections, and various data visualisations, is available under https://www.psi.ch/en/sls/adress/manuals.

References

Wolf, S. A. et al. Spintronics: a spin-based electronics vision for the future. Science 294, 1488 (2001).

Awschalom, D. D. Semiconductor Spintronics and Quantum Computation (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2002).

Manchon, A. et al. Current-induced spin-orbit torques in ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 035004 (2019).

Hirohata, A. et al. Review on spintronics: principles and device applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 509, 166711 (2020).

Nagaosa, N. et al. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1539 (2010).

McGuire, T. & Potter, R. Anisotropic magnetoresistance in ferromagnetic 3d alloys. IEEE Trans. Magn. 11, 1018 (1975).

Dyakonov, M. I. Spin Physics in Semiconductors 439 (Springer, 2008).

Ganichev, S. D. et al. Spin-galvanic effect. Nature 417, 153 (2002).

Kato, K. Y. & Awschalom, D. Electrical manipulation of spins in nonmagnetic semiconductors. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 77, 031006 (2008).

Ghiasi, S. et al. Charge-to-spin conversion by the Rashba-Edelstein effect in two-dimensional van der waals heterostructures up to room temperature. Nano Lett. 19, 5959 (2019).

Song, Q. et al. Observation of inverse Edelstein effect in Rashba-split 2DEG between SrTiO3 and LaAlO3 at room temperature. Sci. Adv. 3, 1602312 (2017).

Zhang, H. et al. Topological insulators in Bi2Se3, Bi2Te3 and Sb2Te3 with a single Dirac cone on the surface. Nat. Phys. 5, 438 (2009).

Xia, Y. et al. Observation of a large-gap topological-insulator class with a single Dirac cone on the surface. Nat. Phys. 5, 398–402 (2009).

Armitage, N. P., Mele, E. J. & Vishwanath, A. Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three-dimensional solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015001 (2018).

Schröter, N. B. M. et al. Chiral topological semimetal with multifold band crossings and long Fermi arcs. Nat. Phys. 15, 759 (2019).

Desjardins, M. M. et al. Synthetic spin-orbit interaction for Majorana devices. Nat. Mater. 18, 1060 (2019).

Sato, M. & Fujimoto, S. Topological phases of noncentrosymmetric superconductors: edge states, Majorana fermions, and non-Abelian statistics. Phys. Rev. B 79, 094504 (2009).

Albrecht, S. M. et al. Exponential protection of zero modes in Majorana islands. Nature 531, 206 (2016).

Min, H. et al. Intrinsic and Rashba spin-orbit interactions in graphene sheets. Phys. Rev. B 74, 165310 (2006).

Zollner, K., Junior, P. E. & Fabian, J. Strain-tunable orbital, spin-orbit, and optical properties of monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 100, 195126 (2019).

Zollner, K. et al. Twist- and gate-tunable proximity spin-orbit coupling, spin relaxation anisotropy, and charge-to-spin conversion in heterostructures of graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 108, 235166 (2020).

Island, J. O. et al. Spin-orbit-driven band inversion in bilayer graphene by the van der Waals proximity effect. Nature 571, 85 (2019).

Manchon, A. et al. New perspectives for Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Nat. Mater. 14, 871 (2015).

Shikin, A. M. et al. Induced spin orbit splitting in graphene: the role of atomic number of the intercalated metal an di/id hybridization. N. J. Phys. 15, 013016 (2013).

Marchenko, D. et al. Giant Rashba splitting in graphene due to hybridization with gold. Nat. Commun. 3, 1232 (2012).

Marchenko, D., Sánchez-Barriga, J., Scholz, M. R., Rader, O. & Varykhalov, A. Spin splitting of Dirac fermions in aligned and rotated graphene on Ir(111). Phys. Rev. B 87, 115426 (2013).

Varykhalov, A. et al. Tunable Fermi level and hedgehog spin texture in gapped graphene. Nat. Commun. 6, 7610 (2015).

Klimovskikh, I. et al. Spin-orbit coupling induced gap in graphene on Pt(111) with intercalated Pb monolayer. ACS Nano. 11, 368 (2017).

Rybkina, A. A. et al. Origin of giant rashba effect in graphene on Pt/SiC. Symmetry 15, 2052 (2023).

Avsar, A. et al. Spin–orbit proximity effect in graphene. Nat. Commun. 5, 4875 (2014).

Sun, L. et al. Determining spin-orbit coupling in graphene by quasiparticle interference imaging. Nat. Commun. 14, 3771 (2023).

Liang, X. et al. The magnetic proximity effect and electrical field tunable valley degeneracy in MoS2/EuS van der Waals heterojunctions. Nanoscale 9, 9502 (2017).

Zihlmann, S. et al. Large spin relaxation anisotropy and valley-Zeeman spin-orbit coupling in WSe2/graphene/h-BN heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 97, 075434 (2018).

Gmitra, M. & Fabian, J. Graphene on transition-metal dichalcogenides: a platform for proximity spin-orbit physics and optospintronics. Phys. Rev. B 92, 155403 (2015).

Masseroni, M. et al. Spin-orbit proximity in MoS2/bilayer graphene heterostructures. Nat. Comm. 15, 9251 (2024).

Gmitra, M. & Fabian, J. Proximity effects in bilayer graphene on Monolayer WSe2: field-effect spin valley locking, spin-orbit valve, and spin transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 146401 (2017).

Cummings, A. W. et al. Giant spin lifetime anisotropy in graphene induced by proximity effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 206601 (2017).

Manzeli, S., Ovchinnikov, D., Pasquier, D., Yazyev, O. V. & Kiss, A. 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17033 (2017).

Ashton, M., Paul, J., Sinnott, S. B. & Hennig, R. G. Topology-scaling identification of layered solids and stable exfoliated 2D materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 106101 (2017).

Xiang, L. et al. Tunable giant Rashba-type spin splitting in PtSe2/MoSe2 heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 203501 (2019).

Rybkin, A. G. et al. Sublattice ferrimagnetism in quasifreestanding graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 226401 (2022).

Rybkin, A. G. et al. Magneto-spin-orbit graphene: interplay between exchange and spin−orbit couplings. Nano Lett. 18, 1564 (2018).

Zollner, K. et al. Proximity exchange effects in MoSe2 and WSe2 heterostructures with CrI3: twist angle, layer, and gate dependence. Phys. Rev. B 100, 085128 (2019).

Strocov, V. N. et al. k-resolved electronic structure of buried heterostructure and impurity systems by soft-X-ray ARPES. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 236, 1 (2019).

Strocov, V. N. et al. Soft-X-ray ARPES facility at the ADRESS beamline of the SLS: concepts, technical realisation and scientific applications. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 21, 32 (2013).

Strocov, V. N. Intrinsic accuracy in 3-dimensional photoemission band mapping. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 130, 65 (2003).

Strocov, V. N. et al. Three-dimensional electron realm in VSe2 by soft-X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: origin of charge-density waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 086401 (2012).

Silva-Guillén, J., San-Jose, P. & Roldán, T. R. Electronic band structure of transition metal dichalcogenides from Ab initio and Slater-Koster tight-binding model. Appl. Sci. 6, 284 (2016).

Cheng, Y. & Schwingenschlögl, U. MoS2: a first-principles perspective. in Lecture Notes in Nanoscale Science and Technology (Springer International Publishing, 2013).

Splendiani, A. et al. Emerging photoluminescence in monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 10, 1271 (2010).

Wang, Q. H. ua et al. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699 (2012).

Liu, G. et al. Electronic structures and theoretical modelling of two-dimensional group-VIB transition metal dichalcogenides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2643 (2015).

Davies, F. et al. Band alignment of transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B. 103, 045417 (2021).

Pescia, D. et al. Determination of observable conduction band symmetry in angle-resolved electron spectroscopies: non-symmorphic space groups. Solid State Commun. 56, 809 (1985).

Weber, F. et al. Three-dimensional Fermi surface of 2H-NbSe2: implications for the mechanism of charge density waves. Phys. Rev. B. 97, 235122 (2018).

Mahatha, S. K. et al. Electronic structure investigation of MoS2 and MoSe2 using angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy and ab initio band structure studies. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 24, 475504 (2012).

Th, B. oker et al. Band structure of MoS2, MoSe2, and α−MoTe2: angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy and ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. B. 64, 235305 (2001).

Tanuma, S., Powell, C. J. & Penn, D. R. Proposed formula for electron inelastic mean free paths based on calculations for 31 materials. Surf. Sci. Lett. 192, L849–L857 (1987).

Shinotsuka, H. et al. Calculations of electron inelastic mean free paths. XII. Data for 42 inorganic compounds over the 50 eV to 200 keV range with the full Penn algorithm. Surf. Interface Anal. 51, 427 (2018).

Stolyarov, V. S. et al. Superconducting long-range proximity effect through the atomically flat interface of a Bi2Te3 topological insulator. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 9068 (2021).

Starnberg, H. I. Deposition of Ca on the 2H–NbSe2 surface: competing processes. J. Chem. Phys. 160, 164703 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. A precise method for visualizing dispersive features in image plots. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82, 043712 (2011).

Vyalikh, D. V. et al. Tuning the hybridization at the surface of a heavy-fermion system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 137601 (2009).

Smyth, C. M. et al. Origins of fermi-level pinning between molybdenum dichalcogenides (MoSe2, MoTe2) and bulk metal contacts: interface chemistry and band alignment. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 23919 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Fermi level pinning dependent 2D semiconductor devices: challenges and prospects. Adv. Mater. 34, e2108425 (2021)

Nguyen, P. V. et al. Visualizing electrostatic gating effects in two-dimensional heterostructures. Nature 572, 220 (2019).

Strocov, V. N. et al. High-resolution soft X-ray beamline ADRESS at the Swiss Light Source for resonant inelastic X-ray scattering and angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopies. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 17, 631 (2010).

Krempaský, J. et al. Heydemann interpolation correction for energy linearization of soft X-ray monochromators. In Proc. SPIE Proceedings 8139 “Advances in X-Ray/EUV Optics and Components” 8139 (2011).

Student. The Probable Error of a Mean. Biometrika 6, 1–25 (1908).

Andersen, O. K. Linear methods in band theory. Phys. Rev. B. 12, 3060 (1975).

Antonov, V., Yaresko, A. & Harmon, B. Electronic Structure and Magneto-optical Properties of Solids 545 (Springer-Verlag New York Inc., 2004).

Acknowledgements

F.A. acknowledges the financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation within the Grant No. 200020B_188709, and J.M. from the project “Quantum materials for applications in sustainable technologies” (QM4ST) funded as project No. CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004572 by Programme Johannes Amos Commenius within the call Excellent Research. The authors thank J.-H. Dil, I. Di Marko and E. Della Valle for valuable advice, and A. G. Rybkin for expert suggestions on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.N.S. and J.M. conceptualised the research. F.A. performed the experiment supported by V.N.S., X.W., and T.S., as well as processed the data supported by V.N.S. and P.C. J.M., D.N., and A.P. performed the DFT calculations. V.N.S., J.M., and F.A. developed the data interpretation in discussions with other authors. F.A. and V.N.S., supported by J.M., wrote the manuscript with advice from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alarab, F., Minár, J., Constantinou, P. et al. k-dependent modulation of intrinsic spin-orbit interaction in MoSe2 induced by proximity to amorphous Pb. Nat Commun 17, 1076 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67833-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67833-y