Abstract

Recently, high-temperature superconductivity (HTSC) is found in the La3Ni2O7/SrLaAlO4 ultrathin film with critical temperature Tc above the McMillan limit at ambient pressure (AP). It is eager to enhance Tc of La3Ni2O7 at AP. We propose that a perpendicular electric field strongly enhances Tc in the single-bilayer film of La3Ni2O7 at AP. Under electric field, the layer with lower potential energy will accept electrons flowing from the other layer to fill in the Ni-\(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals, as the nearly half-filled Ni-\(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital cannot accommodate more electrons. With the enhancement of the filling fraction in the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals in this layer, the interlayer s-wave pairing is suppressed, but the intralayer d-wave pairing in this layer is strongly enhanced. We numerically verify this idea and yield that an imposed voltage of about 0.1 ~ 0.2 volt between layers is enough to realize liquid-nitrogen-temperature HTSC in this single bilayer at AP. Our results appeal for experimental verification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of superconductivity (SC) with critical temperature Tc above the boiling point of liquid nitrogen ( ≈ 77 K) in the pressurized La3Ni2O71,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 has attracted great interests10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144. This discovery has sparked the exploration of high-temperature SC (HTSC) in Ruddlesden-Popper phase multilayer nickelates, resulting in the discovery of SC in the pressurized La4Ni3O1039,40,41,42,43,44,45, which together with the previously synthesized infinite-layer nickelates Nd1−xSrxNiO246,47,48,49 have established a new family of SC other than cuprates and iron-based superconductors. However, the high pressure (HP) circumstance not only strongly hinders the experimental detection of the samples but also brings difficulties in the application of SC in industry. Very recently, the La3Ni2O7 ultrathin film with a few layers of unit cell grown on the SrLaAlO4 (SLAO) substrate has been grown by two different groups independently and SC with Tc above the McMillan limit ( ≈ 40 K) has been detected at ambient pressure (AP)132,133,134, allowing various experimental investigation of the pairing mechanism in this material, attracting a lot of interests135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144. It is now eager to enhance the Tc of this material at AP. Here we propose a viable approach to realize Tc above the boiling point of liquid nitrogen in the La3Ni2O7 single-bilayer film at AP.

Presently, the pairing mechanism in the La3Ni2O7, either in the bulk material under HP74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,104,105,106,107,108,125,126,127,128 or in the ultrathin film at AP135,138,140,143, is still under debate. Density-functional-theory (DFT) based first-principle calculations have suggested that the low-energy orbitals are mainly Ni-\(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) and \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\), which are nearly half- and quarter- filled50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,61. Various experiments have revealed the strongly-correlated characteristic of the material14,16,22,24,25,28,31,32. Particularly, the optical study reveals significant reduction of the electron kinetic energy which places the system in the proximity of the Mott phase25; the angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy uncovers strong band renormalization caused by electron correlation28; the linearly temperature-dependent resistivity suggests “strange-metal” behavior2. Therefore, we take a strong-coupling view of the system. Under the strong Hubbard repulsion, the nearly half-filled \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) electrons can almost be viewed as localized spins. Therefore, the main carrier of SC should be the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) electrons, which subject to the in-plane superexchange interaction just mimic the 50% hole-doped cuprates. However, it is a problem how HTSC can emerge under such a high doping level. The key physics lies in the important role played by the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals. Through strong interlayer perpendicular superexchange, the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) electrons form interlayer pairing. The interlayer perpendicular superexchange or the interlayer pairing of the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) electrons can be transmitted to the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) electrons through the Hund’s rule79,80,82,87,92,93,95,96,97,98,100,107,108 or the nearest-neighbor (NN) hybridization65,83,86,87,91,98,105,107,108 or both. Under such view, the role of pressure in enhancing the Tc lies in the enhancement of the interlayer perpendicular superexchange, the inter-orbital hybridization, or both.

In this work, we propose an alternative approach to realize HTSC with Tc above the boiling point of liquid nitrogen in the ultrathin film of La3Ni2O7 at AP. Here we consider the thinnest limit, i.e. a single bilayer film of La3Ni2O7, and realize the goal by introducing charge transfer with a perpendicular electric field, which let the electrons flow from the high-energy layer to the low-energy layer, similar to the mechanism for the spontaneous charge transfer in oxide heterostructures145,146,147,148,149,150. The external electric field based approach avoids introducing disorder as in chemical doping151 or exhibiting orbital selectivity based on symmetry152, demonstrating exceptional performance in the field of twisted multilayer graphene materials153,154,155. We can impose a perpendicular electric field, say pointing upward, in this single bilayer, so that electrons from the top layer will flow to the bottom layer. These electrons will fill the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals in the bottom layer as the nearly half-filled \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals there cannot accommodate more electrons. The enhancement of the bottom-layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) electron number will first suppress the interlayer s-wave SC due to mismatch of the electron numbers between the two layers, similar with the case in which an imposed Zeeman field acting on the spin leads to mismatch of the electron numbers between the two spin species and thus suppresses singlet pairing, and then promptly lead to the intra-bottom-layer d-wave SC with strongly enhanced Tc. To test this idea, we have performed a combined simplified single orbital study and a comprehensive two orbital study, which consistently yield that a voltage of experimentally achievable levels (around 0.1 ~ 0.2 volt predicted by the mean-field calculations) between the two layers is enough to induce d-wave SC with Tc above the boiling point of liquid nitrogen in the bottom layer. Intriguingly, the d-wave SC carried by the bottom layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) electrons coexists with the interlayer s-wave pseudo gap carried by the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) electrons in the mixing ratio of 1: i, breaking time-reversal symmetry. Our proposal potentially provides a viable approach to realize HTSC with Tc above the boiling point of liquid nitrogen in the single bilayer film of La3Ni2O7.

Results

Consideration and a simplified study

The La3Ni2O7 ultrathin film grown on the SLAO substrate form a bilayer square lattice135,137. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, the leading hopping integrals are the interlayer hopping of the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) electrons t⊥ and the intralayer NN hopping of the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) electrons t∥. Under strong Hubbard U, these hopping terms can induce the effective superexchange J⊥ and J∥ through \(J\approx \frac{4{t}^{2}}{U}\). Under the Hund’s rule coupling JH, the spins of the two orbitals are inclined to be parallel aligned, as illustrated in Fig. 1b, which partly transmits the interlayer perpendicular superexchange J⊥ between the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals to the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals as \({\widetilde{J}}_{\perp }=\alpha {J}_{\perp }\) with α ∈ (0, 1) describing the efficiency of this process and related to the strength of Hund’s coupling JH. In addition, there exists intralayer NN- hybridization txz between the two orbitals. As shown in Fig. 2(a, b), the nearly quarter-filled \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) electrons subject to J∥ and \({\widetilde{J}}_{\perp }\) form interlayer-dominant pairing79.

a Schematic diagram for the dominant hopping integrals and superexchange interactions between the Eg orbitals in La3Ni2O7. b Schematic diagram illustrating that the Hund’s rule coupling transmits the interlayer perpendicular superexchange interaction J⊥ between the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals to the effective one \({\widetilde{J}}_{\perp }\) between the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals.

Now let us turn on the upward electric field ε, forcing electrons downward, as shown in Fig. 2(c, d). In the top layer, since the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals host larger density of state (DOS) than the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals, they will donate more electrons. Most of these donated electrons will fill the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals in the bottom layer, as the nearly half-filled \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals there cannot accommodate more electrons. A minority of the donated electrons can also be accepted by the top-layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals.

Even with doped holes under ε, the top-layer \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) electrons cannot carry SC: Firstly, lacking pairing interaction, they cannot form intralayer pairing. Secondly, although they can pair with the localized bottom-layer \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) electrons, such pairs cannot coherently move, only resulting in the pseudo-gap. Therefore, the SC under ε can only be carried by the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals. As the filling fractions of the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals in the two layers are different, their Fermi levels are relatively shift, leading to mismatch of their Fermi surfaces (FSs), which will suppress their interlayer pairing. Here the perpendicular electric field acts as a “pseudo-Zeeman field” acting on the layer index, just like the Zeeman field acting on the spin degree of freedom. The bottom-layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals will form d-wave SC, mimicsing the cuprates, as shown in Fig. 2(d). When ε is strong enough so that the filling fraction of the bottom-layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals is near that of the optimal doped cuprates, d-wave HTSC with strongly enhanced Tc will be achieved in this layer, and the top layer will also acquire SC below Tc through proximity.

Based on the above general consideration, we first conduct the following simplified model study including only the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbital, with the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital only viewed as a source which tunes the total electron number. The following widely adopted single \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbital bilayer t − J − J⊥ model79,80,82,92,93,95,96,100 is adopted,

Here \({c}_{i\mu \sigma }^{{\dagger} }\) creates an electron at site i in the layer μ (=top (t)/bottom (b)) with spin σ, \(\widehat{P}\) is a projection operator projecting out the double occupancy of all site, and niμ or Siμ denote the corresponding electron number or spin operator. Only NN- bond 〈i, j〉 is considered in the summation. The ϵμ is introduced to control the filling fractions of the two layers under ε, with ϵt − ϵb = ε. However, as the total particle number of the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) electrons under given ε is unknown, we have to assume the ratio r: 1 between the electron number flowing from the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals and that flowing from \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals in the top layer when solving the model with the standard slave-boson mean-field (SBMF) theory156, which demonstrates exceptional performance for La3Ni2O7 in previous studies79,80 that is qualitatively consistent with experimental data1 and theoretical studies using other numerical methods (like DMRG)82,92,96. Due to reason of DOS, we assume this ratio to be 2: 1, with details provided in the Supplementary Information (SI). Nevertheless, the concrete value of this ratio turns out not to obviously affect the results (see the SI). The filling fractions are fixed under this assumption in the SBMF study. To capture the quantum fluctuation beyond mean-field, the density matrix renormalization group (DMRG)157,158 method is also employed, whose results are qualitatively consistent with those of the SBMF study, indicating that the SBMF theory can capture the main features of this system. See details in the Methods and SI.

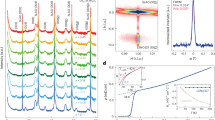

We set t∥ = 1 as the energy unit and J∥ = 0.4t∥ in our study. \({\widetilde{J}}_{\perp }=(1-{\delta }_{tz})\times 1.3{J}_{\parallel }\) is applied in our SBMF study. The results are shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3(a) shows the amplitude and symmetry of the ground-state pairing gap as function of the bottom-layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) electron number nbx, whose value enhances with ε. It is shown that when ε or nbx enhances, the pairing amplitude \(\widetilde{\Delta }\) decays first and then increases. When nbx = 0.5, the ground state is confirmed to be interlayer s-wave SC by comparing the energies of states with different symmetries (See SI for more details). Then the s-wave pairing is suppressed by the enhancement of ε or nbx because of the mismatch of the FSs of the two layers caused by ε, similar to the case of a singlet pairing state placed within a pair-breaking Zeeman field. Therefore, it is also possible that this “pseudo Zeeman field” can drive pair density wave (PDW), just like that the real Zeeman field can drive the Fulde-Ferrell-Larkin-Ovchinnikov state. When nbx ≥ 0.53, the ground state is an intralayer d-wave SC, with the dominant pairing limited in the bottom layer. It is inspiring that with the enhancement of nbx in this regime, the \(\widetilde{\Delta }\) enhances promptly, similar to the case in the overdoped cuprates, wherein the enhancement of the filling fraction promptly enhances the pairing strength. The pairing configurations of the two different pairing symmetries are illustrated in Fig. 3(c, d).

a The pairing amplitude \(\widetilde{\Delta }\) (in unit of t∥) as function of the bottom-layer particle number per site nbx. Different pairing symmetries are distinguished by color. b The Tc as function of nbx, in comparison with \(0.42\widetilde{\Delta }\) for the d-wave and \(0.9\widetilde{\Delta }\) for the s-wave regime. Inset: the spinon pairing temperature Tpair and the holon condensation temperature TBEC as function of nbx. In (a, b), we set J∥ = 0.4t∥ and \({\widetilde{J}}_{\perp }=(1-{\delta }_{tz})\times 1.3{J}_{\parallel }\). c, d The pairing configurations of the s-wave and d-wave, respectively.

The Tc ~ nbx is shown in Fig. 3(b). In the SBMF theory, the Tc is given as the lower one between the spinon-pairing temperature Tpair and the holon-BEC temperature TBEC. The inset of Fig. 3(b) displays TBEC ≫ Tpair, rendering Tc = Tpair in the considered nbx regime. Note that the Tc here is in the sense of Kosterlitz-Thouless transition. A comparison between Fig. 3(b) and (a) suggests that Tc scales with \(\widetilde{\Delta }\), which is more clear when the Tc ~ nbx is well fitted by \(0.42\widetilde{\Delta } \sim {n}_{bx}\) for the d-wave and \(0.9\widetilde{\Delta } \sim {n}_{bx}\) for the s-wave in Fig. 3(b), consistent with the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory. Inspiringly, for nbx≥0.75, the Tc ≳ 0.02t∥ ≈ 80 K, suggesting the HTSC in the liquid nitrogen temperature range.

On the above, we have adopted \({\widetilde{J}}_{\perp }=\alpha {J}_{\perp }(1-{\delta }_{tz})\) with α = 1, where δtz denotes the hole density of the top-\(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital. For the reduced α, only the low-nbx regime accommodating the interlayer s-wave pairing in Fig. 3(a, b) shrinks but the high-nbx regime accommodating the intralayer d-wave SC is not affected because the intralayer pairing is blind to \({\widetilde{J}}_{\perp }\). Furthermore, assuming different ratios between the changes of the filling fractions of the two top-layer Eg orbitals turns out to yield similar results when expressed as functions of nbx, as the dominant pairing under strong ε is the intra-bottom-layer pairing, which is blind to the filling fraction of the top layer. See the SI for details.

We have further employed the DMRG approach, which can capture the quantum fluctuation beyond mean-field, to compute the ground state of Hamiltonian (1) under different electric fields ε and the transferred electron-doping levels of the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals δ = ntx + nbx − 1. For ε = 0, we have δ = 0. When ε increases, it drives electrons from \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\)-orbitals in the top layer to \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbitals in both layers, increasing δ. However, as the exact relationship between ε and δ is unclear, we set them as two independent variables in our DMRG study. The parameters t∥ and J∥ take the same values as the ones in the SBMF study while \({\widetilde{J}}_{\perp }=0.8{J}_{\parallel }\) is adopted in the DMRG study. To characterize the pairing symmetry and strength, we analyze the interlayer pairing correlation function Φ⊥(r) and the intra-bottom-layer pairing correlation function \({\Phi }_{b}^{\parallel }(r)\). More details are provided in Methods.

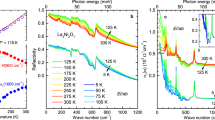

Figure 4 (a) shows the pairing phase diagram with respect to δ ( = 0, 1/16, 1/8) and ε ( ∈ [0, 1.6t∥]). Figure 4(b) shows the absolute value of the intra-bottom-layer pairing correlation functions \(| {\Phi }_{b}^{\parallel }(r)|\) under different electric fields ε = 0, 0.4t∥, 0.8t∥, 1.2t∥, 1.6t∥ for δ = 0, and the results for δ = 1/16 are presented in Fig. 4(c). It turns out that \(| {\Phi }_{b}^{\parallel }(r)|\) exhibits algebraic decay under an non-zero external electric field with the decaying power exponent to be KSC, i.e. \(| {\Phi }_{b}^{\parallel }(r)| \propto {r}^{-{K}_{{{\rm{SC}}}}}\) for large enough r, implying the presence of pairing within the bottom layers. Figure 4(d) and (e) depict \(| {\Phi }_{b}^{\parallel }(r)|\) for different transferred \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-electron-doping levels δ = 0, 1/16, 1/8 under ε = 0.4t∥ in (d) and ε = 0.8t∥ in (e). All the algebraic decay exponents KSC are provided accordingly.

a The δ − ε phase diagram of the ground state. The red region corresponds to the s-wave pairing and the blue region to the d-wave pairing. The absolute value of the intra-bottom-layer pairing correlation functions \(| {\Phi }_{b}^{\parallel }(r)|\) under different electric fields ε = 0, 0.4t∥, 0.8t∥, 1.2t∥, 1.6t∥ for δ = 0 in (b) and δ = 1/16 in (c). \(| {\Phi }_{b}^{\parallel }(r)|\) for different transferred \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-electron-doping levels δ = 0, 1/16, 1/8 under ε = 0.4t∥ in (d) and ε = 0.8t∥ in (e). The algebraic decay exponents KSC are written in the four figures as well, reflecting the decay rate of the pairing correlation function with spatial distance, negatively correlated with the corresponding pairing strength. In (a–e), δ and ε are set as independent variables, since their exact relationship is unclear.

The results indicate that (i) With the enhancement of the perpendicular electric field ε, and hence the transferred \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-electron-doping level δ, the pairing symmetry changes from interlayer s-wave to intra-bottom-layer d-wave (The criterion of the pairing symmetry is provided in Methods); (ii) For all the transferred \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-electron-doping levels δ tested, the enhancement of the perpendicular electric field ε leads to a reduction of KSC, suggesting the enhancement of the intra-bottom-layer pairing; (iii) Under all the perpendicular electric field strengths ε tested, the enhancement of the transferred \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-electron-doping level δ leads to a reduction of KSC, suggesting the enhancement of the intra-bottom-layer pairing. From (ii) and (iii), it is clear that the enhancement of ε and hence δ will significantly enhance the intra-bottom-layer pairing. These results are qualitatively consistent with those of the SBMF study. More results are given in the SI.

Besides, we study the effect of interlayer Coulomb interaction. Our results show that the interlayer Coulomb interaction slightly promotes charge transfer between layers and the intra-bottom-layer pairing, while suppressing the interlayer pairing. See SI for details.

The comprehensive two-orbital study

The above simplified single-orbital study has drawbacks: We cannot determine the relationship between the electron-doping of the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals and the electric field. In the SBMF study, we have to assume the ratio between the changes of the filling fractions of the two top-layer Eg orbitals. In addition, we do not know how the neglected \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital degree of freedom affects the pairing nature. To settle these puzzles, we conduct a comprehensive two-orbital model107 to study with,

The operators ciμασ, niμα, Siμα take the same meanings as those in model (1) except for an extra index α = x/z labeling the orbital, and \(\widehat{P}\) is a projection operator projecting out the double occupancy in the same orbital of all sites. Note that Siμα for each orbital is spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) operator. ϵα denotes the on-site energy of the orbital α. We adpot the tight-binding (TB) parameters reported in ref. 141, i.e. t∥ = 0.445 eV, txz = 0.221 eV, t⊥ = 0.503 eV and ϵx − ϵz = 0.367 eV. The superexchange interactions are obtained through \({J}_{\parallel }\approx 4{t}_{\parallel }^{2}/U\) and \({J}_{\perp }\approx 4{t}_{\perp }^{2}/U\), with U = 10t∥. Finally ε denotes the voltage between the two layers. Here, due to the weak super-exchange interaction between the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals in the layer, we do not consider this term in our model. In addition, the Hund’s coupling JH of La3Ni2O7 is generally considered to be in the range of 0.7 eV to 1 eV in past studies68,70,76, which only slightly larger than the largest hopping parameter t⊥ = 0.503eV and thus does not satisfy the premise of the Schriffer-Wolf transformation or perturbation theory, we do not apply it here. More details are provided in Methods.

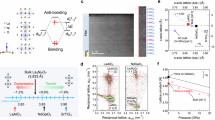

Our SBMF results of Eq. (2) (see Methods and the SI) are shown in Fig. 5. Figure 5(a) shows the ε-dependence of the hole densities δμα. Obviously, the δtz enhances obviously with ε, suggesting that the top-\(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital is donating electrons. These donated electrons flow to the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals in both layers, with more of them flowing to the bottom layer when ε > 0.1 eV while about half of them flow to the bottom layer when ε ≤ 0.1 eV. Figure 5(b) shows the ε-dependence of the pairing symmetry and the pairing gap amplitude of the bottom-layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital. At low ε ≤ 0.03 eV, the pairing symmetry is s-wave, whose pairing configuration is shown in Fig. 5(c), wherein the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\)-orbital form interlayer s-wave pseudo-gap, while the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital form s-wave SC with coexisting intralayer and interlayer pairing. In this regime the interlayer pairing is suppressed by the enhancement of ε while the intralayer pairing is enhanced. When ε = 0, the interlayer pairing gap is the largest. When ε is about 0.01 ~ 0.03 eV, the intralayer pairing gap is slightly larger than the interlayer pairing gap. When ε > 0.03 eV, the pairing symmetry is d(\(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\))+is(\(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\)), whose pairing configuration is shown in Fig. 5(d). In this state, the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital form interlayer s-wave pseudo-gap, while the bottom-layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital form intralayer d-wave SC. When ε enhances in this regime, the pairing amplitude for the d-wave part enhances promptly. For ε > 0.13 eV, the pairing amplitude can go beyond 0.02 eV. Then from the relation \({T}_{c}\approx 0.42\widetilde{\Delta }\) for the d-wave SC illustrated in Fig. 3(b), we have got HTSC with Tc ≳ 80 K!

a The hole densities δμα for the three orbitals as functions of the strength of the electric field ε. b The pairing gap amplitude of the bottom-layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbital as function of ε. c, d The pairing configurations of the s-wave and the d(\(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\))+is(\(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\))-wave, respectively.

The result shown in Fig. 5(b) for the comprehensive two-orbital study and that shown in Fig. 3(b) for the simplified one-orbital study look similar, except that in Fig. 5(b) the result is expressed as function of the directly controllable quantity ε. Actually, if we replace the x-axis of Fig. 5(b) by the calculated nbx = 1 − δbx, the resulting curve nearly coincides with Fig. 3(b), particularly in the large-nbx regime, see the SI. The main reason for such similarity lies in that under strong ε, the dominant superconducting pairing is the intra-bottom-layer \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbital pairing, which is insensitive to the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital. The main new information obtained in the two-orbital study lies in that the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital form interlayer s-wave pseudo-gap which is mixed with the intra-bottom-layer d-wave HTSC of the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital in the ratio of 1: i, as shown in Fig. 5(d). This state breaks time-reversal symmetry, although the experimentally detected superconducting gap is the standard d-wave gap of the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital. This intriguing result is left for experimental verification.

Discussion

In conclusion, we propose that an imposed strong perpendicular electric field can drive HTSC with Tc above the boiling point of liquid nitrogen in the single-bilayer film of La3Ni2O7 at AP. The reason lies in that under the strong electric field, the electrons in the layer with higher potential energy will flow to the layer with lower potential energy, to fill the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals in the latter layer. When the imposed electric field is weak, it acts as the "pseudo-Zeeman field" operating on the layer index which supresses the interlayer SC, possibly inducing the PDW state. With considerably enhanced filling fraction, the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) electrons in that layer just mimic the cuprates, which form intralayer d-wave HTSC with strongly enhanced Tc. Our combined one-orbital and two-orbital studies consistently verify this idea.

Presently, while different groups have provided slightly different TB parameters for the La3Ni2O7 ultrathin film grown on SLAO substrate at AP, we have just adopted one set of these TB parameters to perform our calculations. However, the strong-coupling calculations performed here do not seriously rely on the accurate values of these parameters, because the main physics here is clear and simple. Actually, the well consistency between the result of the comprehensive two-orbital study and those of the simplified one-orbital studies with assuming different input conditions just verifies the robustness of our conclusion.

Moreover, we want to emphasize that the essence of introducing the perpendicular electric field is breaking the symmetry of the two layers by making their filling fractions different to each other. Actually, the filling fractions of different NiO layers in the La3Ni2O7 ultrathin film grown on the SLAO substrate may different from each other because of the existence of the substrate on one side of the film. This can be considered as effective electric field. Thus, our work provides a possible way to understand the high Tc of the La3Ni2O7 ultrathin film grown on the SLAO substrate.

Methods

The one-orbital model

The SBMF theory is used to solve the one-orbital model(1). In the SBMF approach, the superexchange terms are decomposed in χ − Δ channel, e.g. \({{{\bf{S}}}}_{it}\cdot {{{\bf{S}}}}_{ib}=-\frac{3}{8}\left(\left\langle {\chi }^{\perp {\dagger} }\right\rangle {\chi }_{i}^{\perp }+{{\rm{h.c.}}}+\left\langle {\Delta }^{\perp {\dagger} }\right\rangle {\Delta }_{i}^{\perp }+{{\rm{h.c.}}}\right)\), χ and Δ represents hopping and pairing operators respectively. These MF parameters are further solved in a self-consistent manner. The specific steps can be referenced from prior work79,107,156 and SI.

We also employ the DMRG method157,158 to solve the ground state of the Hamiltonian(1) as a comparison for the SBMF approach. The tensor libraries TensorKit159 and FiniteMPS160 provide an implementation of the required symmetry161,162. We study the model on a 2 × 2 × Lx lattice with the open boundary conditions in the x direction and choose Lx = 64 for calculations. The matrix product state is constructed as shown in Fig. 6. We keep up to D = 12000 U(1)charge × SU(2)spin multiplets in DMRG simulations and ensure the convergence accuracy of 10−6.

The interlayer and intralayer singlet pairing operators take the form of

Here, the subscripts i + x(i + y) represent the NN site of the site i in the x(y) direction. Figure 7 shows how the singlet pairing operators are defined.

The considered correlation functions are defined as follow

where r = ∣i − j∣ is the distance between the sites i and j.

For a pairing channel whose absolute value of correlation function decays algebraically with distance, following the form \({r}^{-{K}_{{{\rm{SC}}}}}\), the decay exponent KSC is associated with the Luttinger parameter specific to the channel. KSC < 2 signals a divergent superconducting susceptibility in that channel. The channel with the lowest KSC value is considered to dominate the pairing behavior.

The dominant pairing channel is related to pairing symmetry. For the case where interlayer pairing dominates, the pairing symmetry is restricted to s-wave pairing; while for the case where intralayer pairing in the bottom-layer dominates, we determine the pairing symmetry by the sign function \({{\rm{sgn}}}\left[{\Phi }_{b}^{\parallel }(r){\Phi }_{b}^{{{\bf{xy}}}}(r)\right]\). If \({{\rm{sgn}}}\left[{\Phi }_{b}^{\parallel }(r){\Phi }_{b}^{{{\bf{xy}}}}(r)\right]=-1\) holds for all r, the ground state can be identified as the d-wave pairing SC state. See SI for more details on DMRG.

The two-orbital model

Here we provide more technique details for the SBMF study on the two-orbital model(2). The electron operator is decomposed as \({c}_{i\mu \alpha \sigma }^{{\dagger} }={f}_{i\mu \alpha \sigma }^{{\dagger} }{b}_{i\mu \alpha }\), where f is spinon operator and b is holon operator. Since we have found that TBEC ≫ Tpair in the considered nbx regime and Tpair is proportional to the zero-temperature spinon pairing gap, we can get the critical temperature of superconductivity only by calculating the ground-state spinon pairing gap. Thus we only consider the spinon Hamiltonian at zero temperature. The superexchange term is also decomposed in χ − Δ channel. The spinon Hamiltonian is described as

where \({\delta }_{\mu \alpha }=\left\langle {b}_{i\mu \alpha }{b}_{j\mu \alpha }^{{\dagger} }\right\rangle\) since holon condense at zero temperature. Under the electric field, we have δbz = 0 and δtz, δtx and δbx are solved in a self-consistent manner by adjustment to onsite energies ϵα (See SI for more details). The mean-field order parameters are represented by

and

Notably, the spin-exchange \({\widetilde{J}}_{\perp }\) of the Hamiltonian in Eq. (2) doesn’t produce a hopping term \({\chi }_{x}^{\perp }\) in Eq. (5), which is the feature of such a bilayer system. Without interlayer hopping, a small interlayer spin-exchange J⊥ leads to 〈χ⊥〉 ≈ 0.

Consequently, the \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital only participate in the interlayer pairing. However, this pairing is not SC as the corresponding SC order parameter goes to zero in the SBMF theory due to δbz = 0. The SC is carried by the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals, which can form both intralayer and interlayer pairing. The superconducting Tc scales with the ground state gap amplitude of the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals via the BCS relation exhibited in Fig. 3(b).

The expectation value of the mean-field order parameters are obtained by numerically solving the following self-consistent equations

where \(\epsilon \, ({{\bf{k}}})=\frac{\cos ({k}_{x})+\cos ({k}_{y})}{2}\).

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database at https://zenodo.org/records/17691236.

Code availability

The code that supports the plots within this paper is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Sun, H. et al. Signatures of superconductivity near 80K in a nickelate under high pressure. Nature 621, 493–498 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. High-temperature superconductivity with zero resistance and strange-metal behaviour in La3Ni2O7−δ. Nat. Phys. 20, 1269–1273 (2024).

Hou, J. et al. Emergence of high-temperature superconducting phase in pressurized La3Ni2O7 crystals. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40, 117302 (2023).

Wang, G. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in polycrystalline La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011040 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Observation of high-temperature superconductivity in the high-pressure tetragonal phase of La2PrNi2O7−δ. arXiv:2311.08212. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.08212 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Effects of pressure and doping on Ruddlesden-Popper phases Lan+1NinO3n+1. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 185, 147–154 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Investigations of key issues on the reproducibility of high-Tc superconductivity emerging from compressed La3Ni2O7. Matter Radiat. Extrem. 10, 027801 (2025).

Wang, N. et al. Bulk high-temperature superconductivity in the high-pressure tetragonal phase of bilayer La2PrNi2O7. Nature 634, 579–584 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Identification of the superconductivity in bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7 upon 100 gpa. Natl. Sci. Rev. 12, nwaf220 (2025).

Fukamachi, T., Kobayashi, Y., Miyashita, T. & Sato, M. 139La NMR studies of layered perovskite systems La3Ni2O7−δ and La4Ni3O10. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 62, 195–198 (2001).

Khasanov, R. et al. Pressure-enhanced splitting of density wave transitions in La3Ni2O7−δ. Nat. Phys. 21, 430–436 (2025).

Chen, K. et al. Evidence of spin density waves in La3Ni2O7−δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 256503 (2024).

Zhao, D. et al. Pressure-enhanced spin-density-wave transition in double-layer nickelate La3Ni2O7−δ. Sci. Bull. 70, 1239–1245 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. Electronic and magnetic excitations in La3Ni2O7. Nat. Commun. 15, 9597 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Evidence for charge and spin density waves in single crystals of La3Ni2O7 and La3Ni2O6. Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron. 66, 217411 (2023).

Kakoi, M. et al. Multiband metallic ground state in multilayered nickelates La3Ni2O7 and La4Ni3O10 probed by 139La-NMR at ambient pressure. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 93, 053702 (2024).

Xie, T. et al. Strong interlayer magnetic exchange coupling in La3Ni2O7−δ revealed by inelastic neutron scattering. Sci. Bull. 69, 3221–3227 (2024).

Gupta, N. K. et al. Anisotropic spin stripe domains in bilayer La3Ni2O7. Nat. Commun. 16, 6560 (2025).

Ren, X. et al. Resolving the electronic ground state of La3Ni2O7−δ films. Commun. Phys. 8, 52 (2025).

Feng, J.-J. et al. Unaltered density wave transition and pressure-induced signature of superconductivity in Nd-doped La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 110, L100507 (2024).

Meng, Y. et al. Density-wave-like gap evolution in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure revealed by ultrafast optical spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 15, 10408 (2024).

Fan, S. et al. Tunneling spectra with gaplike features observed in nickelate La3Ni2O7 at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. B 110, 134520 (2024).

Xu, M. et al. Pressure-induced phase transitions in bilayer La3Ni2O7. J. Phys. Chem. C. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.5c07252 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Distinct ultrafast dynamics of bilayer and trilayer nickelate superconductors regarding the density-wave-like transitions. Sci. Bull. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2095927324007503 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Electronic correlations and partial gap in the bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Nat. Commun. 15, 7570 (2024).

Yashima, M. et al. Microscopic evidence for spin–spinless stripe order with reduced Ni moments within ab plane for bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7 probed by 139La-NQR. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 94, 054704 (2025).

Khasanov, R. et al. Oxygen-isotope effect on the density wave transitions in La3Ni2O7 and La4Ni3O10. arXiv:2504.08290. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.08290 (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Orbital-dependent electron correlation in double-layer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Nat. Commun. 15, 4373 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Structure responsible for the superconducting state in La3Ni2O7 at low temperature and high pressure conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7506–7514 (2024).

Cui, T. et al. Strain mediated phase crossover in Ruddlesden Popper nickelates. Commun. Mater. 5, 32 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Electronic correlation and pseudogap-like behavior of high-temperature superconductor La3Ni2O7. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 087402 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Distinguishing electronic band structure of single-layer and bilayer Ruddlesden-Popper nickelates probed by in-situ high pressure X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy. arXiv:2410.04230. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.04230 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Revealing nanoscale structural phase separation in La3Ni2O7−δ single crystal via scanning near-field optical microscopy. arXiv:2410.06602. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.06602 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Chemical versus physical pressure effects on the structure transition of bilayer nickelates. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 1 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. Polymorphism in the Ruddlesden–Popper nickelate La3Ni2O7: discovery of a hidden phase with distinctive layer stacking. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3640–3645 (2024).

Dong, Z. et al. Visualization of oxygen vacancies and self-doped ligand holes in La3Ni2O7−δ. Nature 630, 847–852 (2024).

Li, F. et al. Design and synthesis of three-dimensional hybrid Ruddlesden-Popper nickelate single crystals. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 053401 (2024).

Puphal, P. et al. Unconventional crystal structure of the high-pressure superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 146002 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Superconductivity in pressurized trilayer La4Ni3O10−δ single crystals. Nature 631, 531–536 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Superconductivity in trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10 under pressure. Phys. Rev. X 15, 021005 (2025).

Huang, X. et al. Signature of superconductivity in pressurized trilayer-nickelate Pr4Ni3O10−δ. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 127403 (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Signature of superconductivity in pressurized La4Ni3O10. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 017401 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Intertwined density waves in a metallic nickelate. Nat. Commun. 11, 6003 (2020).

Xu, S. et al. Origin of the density wave instability in trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10 revealed by optical and ultrafast spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 111, 075140 (2025).

Du, X. et al. Correlated electronic structure and density-wave gap in trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10. arXiv:2405.19853. https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.19853 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Superconductivity in an infinite-layer nickelate. Nature 572, 624–627 (2019).

Lee, K. et al. Linear-in-temperature resistivity for optimally superconducting (Nd, Sr) NiO2. Nature 619, 288–292 (2023).

Nomura, Y. & Arita, R. Superconductivity in infinite-layer nickelates. Rep. Prog. Phys. 85, 052501 (2022).

Gu, Q. & Wen, H.-H. Superconductivity in nickel-based 112 systems. Innovation 3. https://www.cell.com/the-innovation/fulltext/S2666-6758(21)00127-2 (2022).

Sui, X. et al. Electronic properties of the bilayer nickelates R3Ni2O7 with oxygen vacancies (R = La or Ce). Phys. Rev. B 109, 205156 (2024).

Luo, Z., Hu, X., Wang, M., Wú, W. & Yao, D.-X. Bilayer two-orbital model of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 126001 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A. & Dagotto, E. Electronic structure, dimer physics, orbital-selective behavior, and magnetic tendencies in the bilayer nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, L180510 (2023).

Cao, Y. & Yang, Y. -f. Flat bands promoted by Hund’s rule coupling in the candidate double-layer high-temperature superconductor La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 109, L081105 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A. & Dagotto, E. Structural phase transition, s±-wave pairing, and magnetic stripe order in bilayered superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Nat. Commun. 15, 2470 (2024).

Huang, J., Wang, Z. D. & Zhou, T. Impurity and vortex states in the bilayer high-temperature superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 174501 (2023).

Geisler, B., Hamlin, J. J., Stewart, G. R., Hennig, R. G. & Hirschfeld, P. Structural transitions, octahedral rotations, and electronic properties of A3Ni2O7 rare-earth nickelates under high pressure. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 38 (2024).

Rhodes, L. C. & Wahl, P. Structural routes to stabilize superconducting La3Ni2O7 at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 044801 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A. & Dagotto, E. Electronic structure, magnetic correlations, and superconducting pairing in the reduced Ruddlesden-Popper bilayer La3Ni2O6 under pressure: Different role of \({d}_{3{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) orbital compared with La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B. 109, 045151 (2024).

Yuan, N., Elghandour, A., Arneth, J., Dey, K. & Klingeler, R. High-pressure crystal growth and investigation of the metal-to-metal transition of Ruddlesden-Popper trilayer nickelates La4Ni3O10. J. Cryst. Growth 627, 127511 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Structural transition, electric transport, and electronic structures in the compressed trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 67, 117403 (2024).

Geisler, B. et al. Optical properties and electronic correlations in La3Ni2O7−δ bilayer nickelates under high pressure. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 89 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Fermiology and electron dynamics of trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10. Nat. Commun. 8, 704 (2017).

Wang, J.-X., Ouyang, Z., He, R.-Q. & Lu, Z.-Y. Non-Fermi liquid and Hund correlation in La4Ni3O10 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 109, 165140 (2024).

Chen, C.-Q., Luo, Z., Wang, M., Wú, W. & Yao, D.-X. Trilayer multiorbital models of La4Ni3O10. Phys. Rev. B 110, 014503 (2024).

Shen, Y., Qin, M. & Zhang, G.-M. Effective bi-layer model hamiltonian and density-matrix renormalization group study for the high-Tc superconductivity La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40, 127401 (2023).

Christiansson, V., Petocchi, F. & Werner, P. Correlated electronic structure of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 206501 (2023).

Shilenko, D. A. & Leonov, I. V. Correlated electronic structure, orbital-selective behavior, and magnetic correlations in double-layer La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, 125105 (2023).

Wú, W., Luo, Z., Yao, D.-X. & Wang, M. Superexchange and charge transfer in the nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron. 67, 117402 (2024).

Chen, X., Jiang, P., Li, J., Zhong, Z. & Lu, Y. Charge and spin instabilities in superconducting La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 111, 014515 (2025).

Ouyang, Z. et al. Hund electronic correlation in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 109, 115114 (2024).

Heier, G., Park, K. & Savrasov, S. Y. Competing dxy and s± pairing symmetries in superconducting La3Ni2O7: LDA + FLEX calculations. Phys. Rev. B 109, 104508 (2024).

Wang, Y., Jiang, K., Wang, Z., Zhang, F.-C. & Hu, J. Electronic and magnetic structures of bilayer La3Ni2O7 at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. B 110, 205122 (2024).

Bötzel, S., Lechermann, F., Gondolf, J. & Eremin, I. M. Theory of magnetic excitations in multilayer nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, L180502 (2024).

Yang, Q.-G., Wang, D. & Wang, Q.-H. Possible S±-wave superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, L140505 (2023).

Liu, Y.-B., Mei, J.-W., Ye, F., Chen, W.-Q. & Yang, F. s±-wave pairing and the destructive role of apical-oxygen deficiencies in La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 236002 (2023).

Lechermann, F., Gondolf, J., Bötzel, S. & Eremin, I. M. Electronic correlations and superconducting instability in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201121 (2023).

Sakakibara, H., Kitamine, N., Ochi, M. & Kuroki, K. Possible high Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure through manifestation of a nearly half-filled bilayer Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 106002 (2024).

Gu, Y., Le, C., Yang, Z., Wu, X. & Hu, J. Effective model and pairing tendency in the bilayer Ni-based superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 111, 174506 (2025).

Lu, C., Pan, Z., Yang, F. & Wu, C. Interlayer-coupling-driven high-temperature superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 146002 (2024).

Oh, H. & Zhang, Y.-H. Type-II t-J model and shared superexchange coupling from Hund’s rule in superconducting La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 174511 (2023).

Liao, Z. et al. Electron correlations and superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under pressure tuning. Phys. Rev. B 108, 214522 (2023).

Qu, X.-Z. et al. Bilayer t-J-J⊥ model and magnetically mediated pairing in the pressurized nickelate La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036502 (2024).

Yang, Y.-F., Zhang, G.-M. & Zhang, F.-C. Interlayer valence bonds and two-component theory for high-Tc superconductivity of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201108 (2023).

Jiang, K., Wang, Z. & Zhang, F.-C. High temperature superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 017402 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A. & Dagotto, E. Trends in electronic structures and s±-wave pairing for the rare-earth series in bilayer nickelate superconductor R3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 165141 (2023).

Qin, Q. & Yang, Y.-F. High-Tc superconductivity by mobilizing local spin singlets and possible route to higher Tc in pressurized La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B. 108, L140504 (2023).

Tian, Y.-H., Chen, Y., Wang, J.-M., He, R.-Q. & Lu, Z.-Y. Correlation effects and concomitant two-orbital s±-wave superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 109, 165154 (2024).

Jiang, R., Hou, J., Fan, Z., Lang, Z.-J. & Ku, W. Pressure driven fractionalization of ionic spins results in cupratelike high-Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 126503 (2024).

Lu, D.-C. et al. Superconductivity from doping symmetric mass generation insulators: Application to La3Ni2O7 under pressure. arXiv:2308.11195. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.11195 (2023).

Kitamine, N., Ochi, M. & Kuroki, K. Theoretical designing of multiband nickelate and palladate superconductors with d8+δ configuration. arXiv:2308.12750. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.12750 (2023).

Luo, Z., Lv, B., Wang, M., Wú, W. & Yao, D.-X. High-Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 based on the bilayer two-orbital t-J model. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 61 (2024).

Zhang, J.-X., Zhang, H.-K., You, Y.-Z. & Weng, Z.-Y. Strong pairing originated from an emergent \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) berry phase in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 126501 (2024).

Pan, Z., Lu, C., Yang, F. & Wu, C. Effect of rare-earth element substitution in superconducting R3Ni2O7 under pressure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 087401 (2024).

Sakakibara, H. et al. Theoretical analysis on the possibility of superconductivity in the trilayer Ruddlesden-Popper nickelate La4Ni3O10 under pressure and its experimental examination: Comparison with La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, 144511 (2024).

Lange, H. et al. Pairing dome from an emergent Feshbach resonance in a strongly repulsive bilayer model. Phys. Rev. B 110, L081113 (2024).

Yang, H., Oh, H. & Zhang, Y.-H. Strong pairing from a small Fermi surface beyond weak coupling: Application to La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 110, 104517 (2024).

Lange, H. et al. Feshbach resonance in a strongly repulsive ladder of mixed dimensionality: A possible scenario for bilayer nickelate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 109, 045127 (2024).

Kaneko, T., Sakakibara, H., Ochi, M. & Kuroki, K. Pair correlations in the two-orbital Hubbard ladder: Implications for superconductivity in the bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, 045154 (2024).

Fan, Z. et al. Superconductivity in nickelate and cuprate superconductors with strong bilayer coupling. Phys. Rev. B 110, 024514 (2024).

Wu, X., Yang, H. & Zhang, Y.-H. Deconfined Fermi liquid to Fermi liquid transition and superconducting instability. Phys. Rev. B 110, 125122 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A. & Dagotto, E. Prediction of s±-wave superconductivity enhanced by electronic doping in trilayer nickelates La4Ni3O10 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 136001 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. The s±-wave superconductivity in the pressurized La4Ni3O10. Phys. Rev. B 110, L180501 (2024).

Yang, Q.-G., Jiang, K.-Y., Wang, D., Lu, H.-Y. & Wang, Q.-H. Effective model and s±-wave superconductivity in trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10. Phys. Rev. B 109, L220506 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A. & Dagotto, E. Electronic structure, self-doping, and superconducting instability in the alternating single-layer trilayer stacking nickelates La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 110, L060510 (2024).

Yang, Y.-F. Decomposition of multilayer superconductivity with interlayer pairing. Phys. Rev. B 110, 104507 (2024).

Ryee, S., Witt, N. & Wehling, T. O. Quenched pair breaking by interlayer correlations as a key to superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 096002 (2024).

Lu, C., Pan, Z., Yang, F. & Wu, C. Interplay of two Eg orbitals in superconducting La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 110, 094509 (2024).

Ouyang, Z., Gao, M. & Lu, Z.-Y. Absence of electron-phonon coupling superconductivity in the bilayer phase of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 80 (2024).

LaBollita, H., Pardo, V., Norman, M. R. & Botana, A. S. Electronic structure and magnetic properties of La3Ni2O7 under pressure: active role of the Ni-\({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals. arXiv:2309.17279. https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.17279 (2024).

Zhang, B., Xu, C. & Xiang, H. Emergent spin-charge-orbital order in superconductor La3Ni2O7. arXiv:2407.18473. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.18473 (2024).

Leonov, I. V. Electronic correlations and spin-charge-density stripes in double-layer La3Ni2O7. arXiv:2410.15298. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.15298v1 (2024).

LaBollita, H., Pardo, V., Norman, M. R. & Botana, A. S. Assessing spin-density wave formation in La3Ni2O7 from electronic structure calculations. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, L111801 (2024).

Ni, X.-S. et al. Spin density wave in the bilayered nickelate La3Ni2O7−δ at ambient pressure. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 17 (2025).

Yi, X.-W. et al. Nature of charge density waves and metal-insulator transition in pressurized La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 110, L140508 (2024).

LaBollita, H., Kapeghian, J., Norman, M. R. & Botana, A. S. Electronic structure and magnetic tendencies of trilayer La4Ni3O10 under pressure: Structural transition, molecular orbitals, and layer differentiation. Phys. Rev. B 109, 195151 (2024).

Jiang, K.-Y., Cao, Y.-H., Yang, Q.-G., Lu, H.-Y. & Wang, Q.-H. Theory of pressure dependence of superconductivity in bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 076001 (2025).

Chen, Y., Tian, Y.-H., Wang, J.-M., He, R.-Q. & Lu, Z.-Y. Non-Fermi liquid and antiferromagnetic correlations with hole doping in the bilayer two-orbital Hubbard model of La3Ni2O7 at zero temperature. Phys. Rev. B 110, 235119 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A., & Dagotto, E. Magnetic correlations and pairing tendencies of the hybrid stacking nickelate superlattice La7Ni5O17 (La3Ni2O7/La4Ni3O10) under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 112, 024508 (2025).

Lin, L.-F. et al. Magnetic phase diagram of a two-orbital model for bilayer nickelates with varying doping. Phys. Rev. B 110, 195135 (2024).

Jiang, G. et al. Intertwined charge and spin instability of La3Ni2O7. Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron. 68, 297411 (2025).

Leonov, I. V. Electronic structure and magnetic correlations in the trilayer nickelate superconductor La4Ni3O10 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 109, 235123 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Growth and characterization of the La3Ni2O7−δ thin films: dominant contribution of the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 124801 (2024).

Liu, Y. Ou, M., Wang, Y. & Wen, H.-H. Temperature-independent Hall coefficient in hole-doped La3Ni2O7 thin films: evidence for single-band transport. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 37, 255502 (2025).

Tian, Y. & Chen, Y. Spin density wave and superconductivity in the bilayer t-J model of La3Ni2O7 under renormalized mean-field theory. Phys. Rev. B 112, 014520 (2025).

Yin, Y., Zhan, J., Liu, B. & Han, X. The s ± pairing symmetry in the pressured La3Ni2O7 from electron-phonon coupling. arXiv:2502.21016. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.21016 (2025).

Xi, W., Yu, S.-L. & Li, J.-X. Transition from s±-wave to \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave superconductivity driven by interlayer interaction in the bilayer two-orbital model of La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 111, 104505 (2025).

Kaneko, T., Kakoi, M. & Kuroki, K. t-J model for strongly correlated two-orbital systems: Application to bilayer nickelate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 112, 075143 (2025).

Ji, J.-H. et al. A strong-coupling-limit study on the pairing mechanism in the pressurized La3Ni2O7. arxiv:2504.12127. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.12127 (2025).

Wang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Jiang, K. Electronic structure and disorder effect of La3Ni2O7 superconductor. Chin. Phys. B 34, 047105 (2025).

Haque, M. E., Ali, R., Masum, M., Hassan, J. & Naqib, S. DFT exploration of pressure dependent physical properties of the recently discovered La3Ni2O7 superconductor. arXiv:2504.15853. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.15853 (2025).

Shi, L., Luo, Y., Wu, W. & Zhang, Y. Theoretical investigation of high-Tc superconductivity in Sr-doped La3Ni2O7 at ambient pressure. arXiv:2503.13197. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.13197 (2025).

Ko, E. K. et al. Signatures of ambient pressure superconductivity in thin film La3Ni2O7. Nature 638, 935–940 (2025).

Zhou, G. et al. Ambient-pressure superconductivity onset above 40 K in (La, Pr)3Ni2O7 films. Nature 640, 641–646 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Superconductivity and normal-state transport in compressively strained La2PrNi2O7 thin films. Nat. Mater. 24, 1221–1227 (2025).

Yue, C. et al. Correlated electronic structures and unconventional superconductivity in bilayer nickelate heterostructures. Natl. Sci. Rev. 12, nwaf253 (2025).

Li, P. et al. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy of superconducting (La,Pr)3Ni2O7/SrLaAlO4 heterostructures. Natl. Sci. Rev. 12, nwaf205 (2025).

Bhatt, L. et al. Resolving structural origins for superconductivity in strain-engineered La3Ni2O7 thin films. arXiv:2501.08204. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.08204 (2025).

Shao, Z.-Y., Liu, Y.-B., Liu, M. & Yang, F. Band structure and pairing nature of La3Ni2O7 thin film at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. B 112, 024506 (2025).

Shi, H. et al. The effect of carrier doping and thickness on the electronic structures of La3Ni2O7 thin films. Chin. Phys. Lett. 42, 080708 (2025).

Le, C., Zhan, J., Wu, X. & Hu, J. Landscape of correlated orders in strained bilayer nickelate thin films. arXiv:2501.14665. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.14665 (2025).

Hu, X., Qiu, W., Chen, C.-Q., Luo, Z. & Yao, D.-X. Electronic structures and multi-orbital models of La3Ni2O7 thin films at ambient pressure. Commun. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02411-8 (2025).

Wang, B. Y. et al. Electronic structure of compressively strained thin film La2PrNi2O7. arxiv:2504.16372. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.16372 (2025).

Huang, J. & Zhou, T. Effective perpendicular electric field as a probe for interlayer pairing in ambient-pressure superconducting La2.85Pr0.15Ni2O7 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 112, 054506 (2025).

Geisler, B., Hamlin, J. J., Stewart, G. R., Hennig, R. G. & Hirschfeld, P. Electronic reconstruction and interface engineering of emergent spin fluctuations in compressively strained La3Ni2O7 on SrLaAlO4(001). arXiv:2503.10902. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.10902 (2025).

Phillips, P. J. et al. Experimental verification of orbital engineering at the atomic scale: Charge transfer and symmetry breaking in nickelate heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 95, 205131 (2017).

Lee, S. et al. Strong orbital polarization in a cobaltate-titanate oxide heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 117201 (2019).

Chandrasena, R. U. et al. Depth-resolved charge reconstruction at the LaNiO3/CaMnO3 interface. Phys. Rev. B 98, 155103 (2018).

Paudel, J. R. et al. Direct experimental evidence of tunable charge transfer at the LaNiO3/CaMnO3 ferromagnetic interface. Phys. Rev. B 108, 054441 (2023).

Mondal, D. et al. Modulation-doping a correlated electron insulator. Nat. Commun. 14, 6210 (2023).

Paudel, J. R. et al. Depth-resolved profile of the interfacial ferromagnetism in CaMnO3/CaRuO3 superlattices. Nano Lett. 24, 15195–15201 (2024).

Jiang, J. et al. Electronic properties of epitaxial La1−xSrxRhO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 103, 195153 (2021).

Sohn, B. et al. Observation of orbital selective charge transfer in a Fe/BaTiO3 interfacial two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 109, 155106 (2024).

Cao, Y. et al. Tunable correlated states and spin-polarized phases in twisted bilayer–bilayer graphene. Nature 583, 215–220 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Observation of dichotomic field-tunable electronic structure in twisted monolayer-bilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 15, 3737 (2024).

Zhou, Z. et al. Gate-tunable double-dome superconductivity in twisted trilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 21, 1773–1779 (2025).

Kotliar, G. & Liu, J. Superexchange mechanism and d-wave superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 38, 5142–5145 (1988).

White, S. R. Density-matrix algorithms for quantum renormalization groups. Phys. Rev. B 48, 10345–10356 (1993).

Lee, Y. L., Lee, Y. W., Mou, C.-Y. & Weng, Z. Y. Two-leg t−J ladder: a mean-field description. Phys. Rev. B 60, 13418–13428 (1999).

Jutho et al. Jutho/tensorkit.jl: v0.12.7. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13950435 (2024).

Li, Q. FiniteMPS.jl. https://github.com/Qiaoyi-Li/FiniteMPS.jl (2025).

Weichselbaum, A. Non-abelian symmetries in tensor networks: a quantum symmetry space approach. Ann. Phys. 327, 2972–3047 (2012).

Weichselbaum, A. X-symbols for non-abelian symmetries in tensor networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023385 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the stimulating discussions with Chen Lu. F. Y. and C. W. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under the Grant No. 12234016. F. Y. is also supported by the CAS Superconducting Research Project under Grant No. [SCZX-0101] and the NSFC under the Grant No. 12074031. C. W. is also supported by the NSFC under the Grant No. 12174317. D. X. Y. is supported by NSFC-12494591, NSFC-92165204, NSFC-92565303, NKRDPC-2022YFA1402802, Research Center for Magnetoelectric Physics of Guangdong Province (2024B0303390001), and Guangdong Provincial Quantum Science Strategic Initiative (GDZX2401010). C. W. is also supported by the New Cornerstone Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. Yang proposed the main idea and supervised the study. Z.-Y. Shao performed the SBMF study. J.-H. Ji performed the DMRG study. D.-X. Yao and C. Wu helped shape the main idea. F. Yang, Z.-Y. Shao and J.-H. Ji wrote the paper. All authors contributed significantly to the data analysis and discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, ZY., Ji, JH., Wu, C. et al. Possible liquid-nitrogen-temperature superconductivity driven by perpendicular electric field in the single-bilayer film of La3Ni2O7 at ambient pressure. Nat Commun 17, 1120 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67880-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67880-5