Abstract

Aqueous zinc-ion batteries offer inherent safety and low cost, yet performance is limited by unstable zinc metal negative electrodes and dissolution-prone positive electrodes, causing dendrite growth, sluggish ion transport, and rapid capacity decay. Replacing both electrodes with intercalation hosts provides a solution, but progress is slowed by the lack of a universal principle for selecting kinetically compatible pairs. Most existing efforts optimize single components rather than addressing the electrodes’ kinetic mismatch governing full-cell stability. Here we show a machine-learning-assisted kinetic-matching framework that quantitatively evaluates ion-transport compatibility in intercalation-type zinc-ion batteries electrodes. By correlating interlayer spacing with Zn2+ diffusion behavior, the model introduces two descriptors predicting synchronized ion flux for rational electrode pairing. Using this framework, an optimized Zn3V3O8 | |NH4V4O10 system achieves a specific capacity of 310 mAh g-1 and retains over 12,000 cycles at 5 A g-1. The strategy further extends to deformable formats through conductive hydrogel architectures, enabling omnidirectionally stretchable, all-hydrogel zinc-ion batteries with an areal capacity of 1.2 mAh cm-2 and an energy density of 1070 μWh cm-2. These results provide a quantitative design route for next-generation zinc-ion batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aqueous zinc-ion batteries (AZIBs) are among the most promising candidates for next-generation energy storage, offering intrinsic safety, low cost, and competitive energy and power densities1. However, their reliance on metallic zinc negative electrodes and traditional deposition-dissolution positive electrodes imposes fundamental electrochemical and mechanical constraints2. Zinc undergoes dendritic growth, corrosion, and parasitic side reactions, degrading Coulombic efficiency, accelerating capacity fade, and shortening cycle life-issues that interfacial coatings or electrolyte additives cannot fully resolve3,4,5. Meanwhile, positive electrode materials in AZIBs primarily operate via three distinct mechanisms: intercalation, dissolution-deposition, and conversion. Dissolution-deposition systems are highly representative because the Zn metal negative electrode—the most common and practical choice for AZIBs—offers high volumetric capacity and operates through a simple, highly reversible mechanism that enables uniform plating/stripping and improved cycling stability. Many positive electrodes, including MnO2, Fe, and organic quinone-based compounds, also rely on reversible dissolution-precipitation reactions6,7,8. Despite their attractive capacities and stability, dissolution-deposition electrodes can still face structural collapse, sluggish Zn2+ kinetics, and incomplete material utilization, which limit specific energy and power capability. In contrast, conversion-type electrodes involve complex multiphase transitions and differ fundamentally in system design, while intercalation and dissolution-deposition remain the two most prevalent and practically relevant categories for AZIBs9,10. Mechanically, the rigidity and limited ductility of zinc metal preclude the repeatable stretchability and omnidirectional flexibility required for flexible electronics. Structural innovations, such as mesh-like architectures and spring-inspired designs11, and conductive hydrogels, can partially accommodate strain12,13, but the continued use of zinc powder and deposition-dissolution positive electrodes perpetuates degradation pathways14. In hydrated environments, hydrogel-induced zinc oxidation further accelerates corrosion, and positive electrode dissolution undermines structural and compositional stability15,16,17. These intertwined challenges have thus far limited AZIB integration across a wide spectrum of applications18,19, from flexible wearables and implantable devices to autonomous Internet of Things sensors, portable power tools, and even stationary grid-level energy storage20,21,22, where reliable, high-performance aqueous batteries are critically needed23.

To surmount these barriers, dual-intercalation architectures have emerged, replacing both zinc and MnO2 with intercalation hosts for the negative and positive electrodes. Inspired by the “rocking-chair” mechanism of lithium-ion batteries24,25, this approach shuttles Zn2+ between two stable lattices, eliminating metal plating/stripping and mitigating dendrite, corrosion, and interface degradation. Compared with Li-ion batteries, where negative electrode overmatching prevents lithium plating, the dual-intercalation aqueous zinc-ion system requires closely synchronized kinetics. Both electrodes rely on intercalation, and Zn2+ transport is slower than Li+, so mismatched diffusion rates at either electrode create bottlenecks and limit performance (Fig. 1). Thus, well-matched intercalation kinetics are essential to maximize rate capability, minimize polarization, and enhance cycling stability. Layered compounds such as titanium phosphate have demonstrated over 10,000 stable cycles with improved safety26, and V-based oxides offer higher theoretical capacity and energy densities. Yet these systems still exhibit low specific capacity and sub-40 percent retention at high rates, highlighting kinetic mismatches between electrode pairs27. In the pursuit of developing desired AZIBs, substantial progress has been achieved in material design, electrode architecture, and interface regulation. However, a key factor that continues to limit full-cell performance is the mismatch in ion diffusion kinetics between intercalation-type positive and negative electrodes. This issue, initially observed by Wu et al. in lithium-ion battery and supercapacitor hybrid systems28, becomes particularly pronounced in dual-intercalation AZIBs, where both electrodes operate within constrained kinetic windows. When the ion transport rates of the two electrodes are not well aligned, the resulting concentration gradients lead to ion accumulation, distorted electric fields, increased polarization, and ultimately reduced energy efficiency and cycling stability29. To address this mismatch, structural modulation has emerged as a promising strategy to achieve diffusion compatibility. One effective method involves crystal facet engineering. For example, exposing the (011) planes of TiS2 improved diffusion kinetics and enabled better compatibility with MnO2 positive electrodes, achieving a high capacity of 71.9 mAh g−1 at 2 A g−1 30. Alternatively, simultaneous lattice optimization of both CoVOH and O-MoO3 electrodes resulted in 90% capacity retention over 500 cycles31, confirming the value of synchronizing diffusion kinetics across both electrodes. These studies demonstrate that structural tuning can effectively improve rate capability and cycling stability. Nevertheless, many intercalation materials continue to exhibit inherently low specific capacities and structural instability, limiting further progress. This performance gap ultimately traces back to a fundamental problem where rational electrode selection criteria for full-cell design remain underdeveloped. Central to this problem is the compatibility of ion diffusion kinetics between the negative and positive electrodes, which serves not only as a prerequisite for maximizing the intrinsic properties of electrode materials but also as a decisive factor in performance optimization. Despite its importance, the field still lacks a universal theoretical framework or quantitative model to evaluate and predict kinetic compatibility. This deficiency forces reliance on empirical trial-and-error strategies and confines material exploration to a narrow range of familiar electrode pairs, thereby hindering innovation in next-generation battery systems. Therefore, developing comprehensive theoretical frameworks and predictive models for ion diffusion kinetics matching is crucial to accelerate the development of cutting-edge AZIB technologies. To address this long-standing challenge, machine learning serves as an indispensable tool for decoding complex electrode kinetics and validating physically derived hypotheses32,33. By integrating domain knowledge with data-driven modeling, machine learning provides a robust statistical framework to quantify and unravel the nonlinear relationships between material properties and electrochemical behavior. This approach enhances the predictability and generalizability of kinetic matching principles, complementing traditional experimental methods and opening pathways for the rational design of high-performance energy storage systems.

The upper set of panels corresponds to a kinetically matched AZIB system, in which balanced (de)intercalation rates enable a uniform Zn2+ flux. Here, ions shuttle efficiently between the electrodes without significant accumulation at the interfaces, maintaining a homogeneous electric field and minimizing polarization-behavior reflected in the well-defined, symmetric CV profile shown schematically alongside the ion-transport illustration. The lower panels represent a mismatched system where asynchronous ion transport during charge/discharge leads to interfacial Zn2+ accumulation. These local imbalances distort the internal electric field and increase polarization, as schematically indicated by the distorted CV response.

In this study, we explore the ionic diffusion kinetics matching and its impact on the electrochemical performance of intercalation-type negative electrode materials with varying diffusion coefficient distributions when paired with layered positive electrodes with controllable diffusion rates. Based on experimental validation across diverse intercalation systems and machine learning optimization, this work establishes a quantitative, machine learning-assisted kinetic matching model that links confined interlayer spacing to ion diffusion kinetics in intercalation electrodes. The model is universal because it systematically evaluates ion-diffusion compatibility across a wide spectrum of intercalation electrodes, rather than being limited to familiar electrode pairs. It is quantitative because it leverages machine learning to establish predictive correlations, replacing semi-empirical heuristics with data-driven rigor and enabling rational optimization of full-cell kinetics. This model introduces two descriptors, Composite Shift Index (CSI) and diffusion ratio (DR), that enable intuitive assessment of kinetic compatibility between electrode pairs. Effective matching is achieved when both conditions are simultaneously satisfied: 0.241 < CSI < 1.013 and 0.936 < DR < 1.020. Notably, the descriptors CSI and DR were derived through experience-guided feature engineering grounded in physical insights into intercalation kinetics. These features were not generated by machine learning but were intentionally designed by researchers to capture the fundamental kinetic characteristics of intercalation processes. Furthermore, by regulating the interlayer spacing and zinc-ion diffusion rate of NH4V4O10, a well-matched Zn3V3O8 | |NH4V4O10 (ZVO||NVO) full cell was designed, exhibiting a high specific capacity of 310 mAh g−1, a long cycle life exceeding 12,000 cycles at 5 A g−1, and notable rate capability. Guided by the proposed kinetic-matching framework, we developed a universal silver-poly(acrylic acid) conductive hydrogel that preserves the structural integrity and electrochemical performance of ZVO||NVO electrodes while reinforcing the mechanical resilience of the stretchable system. This work presents a practical demonstration of an omnidirectionally deformable electrode platform compatible with diverse intercalation materials, offering a generalizable strategy for constructing high-performance, dual-intercalation AZIBs. By integrating hydrogel electrolytes, we further construct an omnidirectionally stretchable AZIB system, achieving a high areal capacity of 1.2 mAh cm−2 and an energy density of 1070 µWh cm−2 (4 cm2). This battery meets the energy demands of wearable electronics (power consumption >2 mW)34, and provides intrinsic flexibility to accommodate omnidirectional deformation, thereby demonstrating the guiding value of the proposed formula. Importantly, the mathematical model for electrode matching provides a robust theoretical foundation and practical reference for electrode pair selection and full-cell performance prediction in Zn-metal-free AZIBs.

Results and discussion

Design principles of dual-intercalation AZIBs

As mentioned, intercalation-type electrode materials typically have narrow kinetic windows, making them prone to mismatches in ionic intercalation rates between the positive and negative electrodes. Additionally, the available positive electrode-negative electrode pairings for intercalation-based systems are more limited compared to those in conventional zinc-metal-based AZIBs, which further constrains the design space for achieving optimal kinetic matching. To systematically address these noted challenges of intercalation AZIBs, it is crucial to first elucidate the nature and consequences of kinetic mismatch between electrodes. A quantitative framework for defining “kinetic matching” must be established to guide material selection and device engineering. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 1, when the positive electrode facilitates rapid Zn2+ deintercalation (typically features a relatively larger interlayer spacing) compared to the slower intercalation kinetics of the negative electrode, charge processes induce significant ion accumulation at the negative electrode-electrolyte interface. Conversely, if the positive electrode possesses sluggish ion insertion kinetics (typically derived from a smaller interlayer spacing), Zn2+ congestion at the positive electrode-electrolyte interface arises during discharge. This phenomenon is referred to as kinetic mismatch between positive and negative electrodes. The kinetic mismatch between the electrodes leads to asynchronous ion intercalation and deintercalation processes. When the positive electrode deintercalates faster than the negative electrode can intercalate, Zn2+ accumulates at the negative electrode-electrolyte interface; conversely, slower positive electrode intercalation relative to negative electrode deintercalation causes ion congestion at the positive electrode-electrolyte interface. These local imbalances distort the uniform electric field within the cell, requiring higher overpotentials to drive ion migration and increasing overall polarization. Electrochemically, this manifests as voltage hysteresis, peak splitting in cyclic voltammetry (CV), and asymmetric current responses, reflecting inefficient redox reactions and compromised kinetics. Quantitative kinetic matching mitigates these effects by synchronizing ion flux, stabilizing interfacial conditions, and minimizing polarization, thereby improving rate performance, energy efficiency, and long-term cycling stability. In contrast, when the ionic intercalation kinetics of the electrodes are well-matched, the Zn2+ flux remains synchronized throughout charged-discharge cycling, maintaining dynamic equilibrium at the electrode-electrolyte interfaces. This balance promotes homogeneous electric field distribution, which is reflected in CV curves with minimal peak separation and near-unity anodic-to-cathodic current ratios. Therefore, rationally designing electrode materials with matched intercalation kinetics is essential for mitigating polarization, enhancing charge-transfer efficiency, and achieving stable long-term cycling.

Kinetic evaluation and structural stability of NVO intercalation electrode

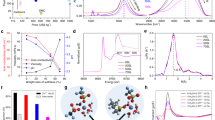

To enable a quantitative evaluation of “kinetic matching”, it is essential to investigate the intrinsic intercalation kinetics of electrode materials in greater depth. In selecting a representative positive electrode model, NVO was chosen due to its two-dimensional layered structure and abundance of redox-active sites. The insertion of NH4+ ions acts as a structural pillar, stabilizing and expanding the V-O layers35, which enhances its capacity to accommodate Zn2+ ions (Fig. S1). The layered structure of NVO supports efficient ion insertion and extraction while ensuring structural stability, which helps maintain high and stable capacity even under rapid charge/discharge cycles, contributing to high-rate performance36. Therefore, NVO offers broad applicability, structural stability, high electrochemical reversibility, and favorable rate capability, making it a reliable positive electrode candidate selected for this study. To investigate the effect of NVO crystal structure on ion intercalation kinetics, the zinc-ion diffusion energy barrier distribution was simulated using Density Functional Theory (DFT) based on its lattice structure, as shown in Fig. 2a. To establish NVO models with varying lattice structures, the number of NH4+ ions and H2O molecules between the V-O layers within the unit cells was adjusted. Specifically, the number of H2O molecules was set to 4, 3, 2, and 1, corresponding to NH4+ ion counts of 12, 13, 14, and 15. This resulted in four NVO structures with different interlayer spacings, yielding c-lattice constants of 13.87, 14.44, 15.21, and 16.46 Å (the atomic coordinates of these models are provided in Supplementary Data 1–4). For NVO-2, NVO-3, and NVO-4, diffusion energy barriers were calculated using the most stable adsorption site at the ammonium vacancy. For NVO-1, which lacks intrinsic vacancies, multiple adsorption configurations were evaluated (Fig. S2), and the configuration with the lowest adsorption energy was selected to ensure accurate diffusion barrier determination. Comparative analysis of two possible diffusion paths, Path-1 and Path-2, revealed that Path-1 exhibits a lower Zn2+ diffusion barrier, confirming it as the most favorable diffusion pathway. These calculations ensure that the reported barriers accurately reflect the energetically preferred ion transport routes. As shown in Fig. 2b, DFT simulation results reveal that the zinc-ion diffusion energy barrier in NVO decreases initially and then increases with the gradual removal of ammonium ions and insertion of water molecules across four structural configurations. This trend is attributed to the evolution of Bader charge and adsorption energy, as presented in Fig. 2c and Table S1. The Bader charge analysis specifically quantifies the charge transfer associated with the Zn2+ ion when occupying different adsorption sites. Importantly, this charge redistribution exhibits an inverse correlation with the diffusion barrier: smaller absolute charge variation corresponds to more effective electrostatic stabilization of Zn2+ within the host lattice, which weakens Zn-host interactions, lowers the energy penalty for ion displacement, and thereby facilitates long-range migration. This analysis explicitly clarifies that it is the charge variation of the Zn2+ ion, rather than changes in the host framework, that underpins the observed correlation between Bader charge values and diffusion barriers. With increasing interlayer spacing, the charge transfer values calculated via Bader analysis of the four models are calculated as −1.11 e, −1.05 e, −0.77 e, and −0.98 e, respectively, accompanied by corresponding adsorption energies of −1.89 eV, −1.26 eV, −0.61 eV, and −2.22 eV. As the absolute adsorption energy of zinc ions on the V-O layers decreases, the diffusion energy barrier drops significantly from 2.57 to 0.77 eV. However, when the interlayer spacing becomes excessively large, the charge transfer values derived from Bader charge analysis increase again, causing zinc ions to favor diffusion along the layer edges, where the stronger adsorption enhances the energy barrier, elevating it to 1.868 eV. These simulation results demonstrate that the ion diffusion kinetics of NVO can be effectively tuned by modulating interlayer spacing, offering a viable strategy for optimizing intercalation dynamic performance.

a Schematic diagrams of the zinc-ion transport paths within the lattice of four different NVO structures (the atomic coordinates of the computational models were provided in Supplementary Data 1–4), white spheres denote hydrogen (H), blue spheres nitrogen (N), small red spheres oxygen (O), large red spheres vanadium (V), and gray spheres zinc (Zn). b DFT-calculated energy barrier distributions for Zn2+ diffusion in NVO, blue, red, purple, and yellow dotted lines correspond to NVO-1, NVO-2, NVO-3, and NVO-4 structures. c Adsorption energies (red dotted line) and corresponding diffusion energy barriers (blue dotted line) of Zn2+ in structurally distinct NVO variants. d Ex situ XRD patterns of the NVO electrode (measured at the fully charged and discharged state during the initial three cycles at 1 A g−1 and 25 °C). e Comparison of Zn2+ diffusion coefficients for ZVO and NVO under different cutoff voltages, blue, red, cyan, and purple dotted lines correspond to NVO-1.6 V, NVO-1.8 V, NVO-2.0 V, and ZVO electrodes. f EQCM curves of ZVO compared with NVO under different voltages (The testing temperature is ~25 °C), yellow, red, and blue curves correspond to ZVO, NVO-1.8 V, and NVO-2.0 V electrodes. g Ex situ XPS V 2p spectrum of the NVO positive electrode and (h) the ZVO negative electrode in the ZVO||NVO full cell (collected from the ZVO||NVO full cell at the fully charged and discharged state during the initial two cycles at 1 A g−1 and 25 °C), green represents V3+, dark green corresponds to V4+, and blue indicates V5+.

An experimental strategy enabling real-time regulation of the actual intercalation rate of NVO allows for precise monitoring of the electrochemical response during the transition from a kinetically “mismatched” to a “matched” state, thereby providing a quantitative framework to define the functional range of kinetic matching. To investigate this, NVO was assembled into a half-cell configuration with zinc metal as the counter electrode for subsequent electrochemical studies. In-situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were conducted, revealing that the interlayer spacing of NVO undergoes reversible changes during the charge-discharge process. Specifically, in-situ XRD results revealed that the (001) diffraction peak of NVO, located in the 5–7° range, shifted to a lower angle during the charging process and gradually returned to a higher angle during discharge (Fig. S3a). According to DFT simulations, this behavior is attributed to the extraction of ammonium ions during charging, which reduces electrostatic interactions between the V–O layers and leads to an expansion of the interlayer spacing. During discharge, the insertion of Zn2+ ions into NH4V4O10 induces a contraction of the interlayer spacing, as evidenced by the shift of the (001) diffraction peak toward higher angles. This behavior contrasts with the gradual peak shift to lower angles reported for other vanadium oxides such as HNaV6O16·4H2O and Al-V2O5·1.6H2O, which is typically attributed to lattice expansion upon Zn2+ intercalation37,38. The distinct response of NH4V4O10 arises from the strong electrostatic interaction between the inserted Zn2+ ions and the negatively charged V-O layers, which effectively pulls the layers closer together and leads to lattice tightening. This contraction is further facilitated by the presence of ammonium ions, which stabilizes the layered structure and enhances the reversibility of the Zn2+ intercalation process. Importantly, this unusual contraction does not indicate a detrimental effect; instead, it reflects the ion-layer interactions in NH4V4O10, which contribute to its high structural stability during cycling. Recent studies on ammonium vanadate positive electrodes have reported similar interlayer contraction phenomena, supporting our observations and providing experimental validation for the proposed mechanism35,39,40. These studies highlight that NH4V4O10-based electrodes can accommodate Zn2+ intercalation without significant structural degradation, which is advantageous for long-term cycling performance and rate capability. Furthermore, ex situ XRD characterization over the initial three charge-discharge cycles (Fig. 2d) showed that the maximum interlayer spacing increased from 1.332 to 1.659 nm during charging to 2.0 V, while the minimum spacing decreased from 1.324 to 1.304 nm during discharging to 0.2 V, eventually stabilizing over time. These results demonstrate that the interlayer spacing of NVO can be effectively modulated by adjusting the charge-discharge cut-off voltage. Simultaneously, these results clearly indicate that the interlayer spacing of NVO remains in a dynamic state throughout electrochemical cycling. As such, it can only be characterized by defining a range between its maximum and minimum values, rather than by a single static value. Consequently, the interlayer spacing of NVO is dynamically modulated by the intercalation and deintercalation of Zn2+ and NH₄+ ions during cycling, creating a distribution of diffusion barriers that governs ion transport. While conventional methods, such as adjusting temperature (Fig. S7) or other targeted interventions like SEI layers and surface engineering can influence overall kinetics, they cannot selectively balance the kinetic mismatch between positive and negative electrode or offer broad applicability. In contrast, controlling the cut-off voltage serves a dual purpose in ensuring positive electrode stability. Firstly, it regulates the range of interlayer spacing variation to tune Zn2+ diffusion pathways and surface flux. Secondly, it mitigates the notorious H+ insertion prevalent at higher potentials. Given the much smaller size of H+ compared with Zn2+ and interlayer NH4+, its insertion causes minimal spacing variation. This is critical, as excessive H+ insertion at high voltages leads to over-reduction of vanadium species and subsequent V–O bond breakage, a primary cause of structural dissolution41,42. The selected voltage window (0.2–1.8 V) effectively limits proton insertion per cycle, thereby mitigating its contribution to vanadium dissolution. Consequently, this strategy not only optimizes kinetic matching across electrodes but also enhances structural integrity by minimizing both lattice strain and H+-induced degradation.

To probe the structural evolution of NVO positive electrode within full-cell AZIBs, it is essential to pair it with suitable negative electrode materials featuring both rapid ion diffusion kinetics and high theoretical capacity. ZVO, a tunnel-structured intercalation-type compound, was selected as the model negative electrode due to its favorable zinc storage characteristics. ZVO can accommodate up to three Zn2+ ions per formula unit, offering high specific capacity, while its robust framework and efficient Zn2+ transport kinetics make it particularly well-suited for probing intercalation rate matching43. These attributes also render ZVO a promising negative electrode candidate for the rational design of dual-intercalation AZIBs. As shown in Fig. S4, XRD analysis confirms that the product corresponds to the standard peaks of ZVO (PDF 31-1477), indicating successful synthesis. Ex-situ XRD of the ZVO negative electrode showed no significant shift in diffraction peaks, demonstrating the stability of its crystal structure and intercalation kinetics during the charge-discharge process. Building on the voltage-controlled interlayer spacing characteristics of NVO and the structural stability of ZVO, it is proposed that the lattice structure of NVO can be adjusted by modifying the cutoff charging voltage to achieve kinetic matching with ZVO. To verify this, the ZVO||NVO full cell was cycled at upper cutoff voltages of 1.6 V, 1.8 V, and 2.0 V, and the changes in the c-lattice parameter after 1, 10, and 50 cycles were examined using ex situ XRD (Fig. S5). The results revealed the cutoff voltage-controlled interlayer modulation mechanism. As the cutoff voltage increased, the extent of interlayer expansion also increased. At a voltage window of 0.2–2.0 V, after 50 cycles, the (001) peak shifted to 5.22°, corresponding to the largest interlayer spacing. Upon discharge, the interlayer spacing contracted significantly, with the peak shifting to 6.72°, the highest among the three groups, indicating structural instability due to excessive extraction of ammonium ions at higher voltages. In contrast, the sample cycled at 0.2–1.8 V exhibited the smallest diffraction angle of 6.50° after discharge, while the peak during charging shifted to 5.28°, suggesting that within the 0.2–1.8 V window, NVO maintains a relatively large and stable interlayer spacing, ranging from 1.332 to 1.640 nm.

Intercalation synergy regulation and compatibility verification of ZVO||NVO cell

To systematically evaluate the impact of positive electrode-negative electrode kinetic matching on the electrochemical performance of full cells, it is necessary to quantify the zinc-ion diffusion coefficients and identify the optimal voltage window for matching the intercalation dynamics of NVO with ZVO. Galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) measurements were performed on both NVO and ZVO electrodes, each assembled in a half-cell configuration with Zn metal as the counter electrode (Fig. S6). As shown in Fig. 2e, ZVO exhibits a faster zinc ion diffusion rate (logD = −11.22 to −9.39) compared to NVO (logD = −11.74 to −10.51). Further GITT tests on NVO at different upper cutoff voltages revealed that NVO displayed the largest ion diffusion coefficient (logD = −9.42 to −10.71) when the maximum cutoff voltage was set to 1.8 V, which aligns with the DFT simulation results and demonstrates a great match with the ZVO negative electrode. This indicates that the voltage window of 0.2–1.8 V facilitates ideal matching of the ion intercalation kinetics in the ZVO||NVO full cell. To further demonstrate the voltage control over NVO ion diffusion kinetics and explore its matching status with ZVO, electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (EQCM) measurements were conducted. As shown in Fig. 2f, significant mass changes are observed at both the negative electrode and positive electrode during the discharge processes. The mass response of NVO with a cutoff voltage of 1.8 V closely mirrors that of ZVO, indicating consistent ion diffusion behaviors between the two electrode materials. XPS analysis of the three samples with different interlayer spacing initiated by cutoff charging voltages, shown in Fig. S3b, reveals that as the maximum cutoff voltage increases, the proportion of vanadium in the V5+-oxidation state also increases from 61.4 to 86.3%. This observation supports the explanation that the expansion of interlayer spacing is due to the extraction of ammonium ions, consistent with charge conservation. These findings demonstrate that increasing the cutoff voltage enhances the capacity of NVO by modulating the ion diffusion kinetics to match that of ZVO, although the higher vanadium oxidation states may increase resistance to zinc ion insertion during discharge.

To investigate the relationship between intercalation compatibility and electrochemical performance in dual-intercalation AZIBs, a ZVO||NVO full cell was constructed as a representative electrode intercalation synergy model. This system serves to reveal the underlying redox mechanisms and ion transport kinetics between the ZVO negative electrode and NVO positive electrode, offering insight into the impact of kinetic matching on overall cell performance. The energy storage mechanism and structural evolution of the ZVO and NVO electrodes were verified during the charge-discharge process in the ZVO||NVO full cell via ex-situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The peak area ratio in Fig. 2g shows that during the charge-discharge process, V5+ remains the dominant species in NVO. Additionally, after discharge, the proportion of V4+ increases from 9.1 to 38.6%, and this change occurs reversibly during the cycling process, demonstrating the stability of the redox mechanism. In Fig. 2h, the results of ZVO negative electrode indicate that vanadium predominantly exists in the +5-oxidation state during discharge and shifts to the +4-oxidation and +3-oxidation state upon charging, confirming a reversible redox reaction that significantly contributes to the high capacity. The alternating insertion and extraction of zinc ions between the two electrodes leads to the reversible rise and fall of the vanadium valence state, proving theoretical feasibility of the stable and reversible redox reaction between ZVO and NVO. Figure S8 shows the CV curves of ZVO within a voltage window of 0.2–1.6 V, displaying two reduction peaks at relatively low potentials of 0.4 and 0.8 V. Electrochemical reaction kinetics were further analyzed from CV curves at different scan rates (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 mV s−1), yielding b-values of 0.794, 0.834, 0.838, and 0.815 for the corresponding oxidation-reduction peaks, indicating that both internal diffusion and surface reactions influence the reaction kinetics, leading to rapid and highly reversible dynamics. Galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) results demonstrate a specific capacity above 260 mAh g−1 at a specific current of 0.2 A g−1 and 115 mAh g−1 at 2 A g−1 (Fig. S9). Additionally, the Zn||ZVO half-cell exhibits high cycling stability, with capacity continuously increasing even after 300 cycles at 2 A g−1 (Fig. S10). NVO has also been tested to possess a high specific capacity of 493 mAh g−1 within a voltage window of 0.2–1.8 V (Fig. S11). Additionally, under this voltage window, the CV curve analysis of the Zn||NVO half-cell reveals that the three pairs of redox peaks correspond to b-values of 0.826, 0.965, 0.845, 0.966, 0.957, and 0.858, indicating similar reaction kinetics with the ZVO negative electrode (Fig. S12). Through the systematic characterizations of the redox mechanisms and analysis of reaction kinetics in the ZVO||NVO full-cell, the results demonstrate the practical feasibility of constructing metal-free zinc-ion batteries using this paired electrode system. Its reversible electrode reaction can be expressed by the following equations:

Notably, to construct a durable metal-free battery system, intercalation electrodes were initially selected from literature-reported candidates27,44,45, but many of these proved highly electrolyte-dependent and prone to positive electrode-negative electrode mismatching. Therefore, the ZVO||NVO system was selected as a representative model, not only due to its well-documented advantages in the literature and more optimal overall performance in preliminary full-cell tests among various intercalation-type electrode pairs, but also because it serves as an exemplary template for high-performance intercalation-matched energy storage systems. This system offers valuable insights into the fundamental correlation between electrode matching and electrochemical behavior.

Electrochemical impact of intercalation kinetics matching

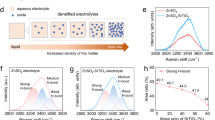

To theoretically elucidate the influence of intercalation kinetics matching status between the positive and negative electrodes on full-cell electrochemical performance, finite element simulations executed by COMSOL Multiphysics were conducted to visualize the spatial distributions of zinc ion concentration and electric field intensity under different kinetic scenarios. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, b, the white circles denote active electrode particles where interfacial intercalation reactions take place, as simulated using a finite element-based microstructure model consistent with established computational studies of battery electrodes46,47. When the ion diffusion rate of the positive electrode is lower than that of the negative electrode, Zn2+ ions tend to accumulate at the positive electrode surface, resulting in a steep concentration gradient and localized electric field intensification at the positive electrode-electrolyte interface. Theoretical calculations of the mismatched model reveal a concentration gradient difference of 0.48 mol m−3 at the positive electrode surface, while the negative electrode side shows only a 0.09 mol m−3 difference. This disparity results in a significant electric field gradient, ranging from 0.75 to 0.43 V m−1, at the positive electrode-electrolyte interface. In contrast, when the diffusion rates of the positive and negative electrodes are well matched, the Zn2+ concentration becomes more uniformly distributed throughout the cell, giving rise to a homogeneous electric field profile with the maximum field intensity located near the negative electrode surface. Consequently, the ion concentration variation at the positive electrode-electrolyte interface in the matched model is 2.2 times smaller than that in the mismatched model, leading to a reduced electric field gradient of 0.22 to 0.18 V m−1, which is seven times lower than that in the mismatched model. This electrodynamic uniformity facilitates more balanced ion transport and improved reaction kinetics. Correspondingly, as shown in Fig. 3c, the voltage differences between the main redox peaks for ZVO||NVO cells with cutoff voltages of 1.6 V, 1.8 V, and 2.0 V were 0.363 V, 0.319 V, and 0.393 V, respectively. The cell operating at 1.8 V, corresponding to the kinetically matched ZVO||NVO configuration, exhibited the smallest peak separation and thus the highest redox reversibility and minimal polarization. These findings underscore the critical role of positive electrode-negative electrode kinetic matching in achieving efficient, stable energy storage performance. As shown in Fig. 3d, the Nyquist plots of NVO subjected to different cutoff voltages reveal that the sample treated at 1.8 V exhibits the steepest low-frequency slope, indicating enhanced interfacial ion diffusion. Consistent with this observation, the Warburg impedance values were determined to be 16.65 ± 0.31 Ω, 15.16 ± 0.19 Ω, and 17.77 ± 0.06 Ω for NVO-1.6 V, NVO-1.8 V, and NVO-2.0 V, respectively. Statistical analysis using Tukey’s HSD test confirms the differences are significant. The NVO-1.8 V electrode showed the lowest impedance, further supporting its faster ion transport kinetics within the full cell.

Finite element modeling of (a) the ion concentration distribution and b the electric field distribution of the dual-intercalation AZIBs with matched and mismatched electrodes. c CV curves of the full cell at different voltage windows. d EIS curves of the full cell at different voltage windows, symbols represent the raw data, solid lines represent the fitted data, and the error is summarized in Table S11 (inset: the corresponding Warburg impedance comparison, the error bars are presented as mean ± standard deviation and n = 5, n denotes the number of independent replicate EIS testing performed for each ZVO||NVO cell). e Rate performance comparison of the full cell at different voltage windows. (Throughout c, d, e, blue, red, and yellow correspond to voltage windows of 1.6 V, 1.8 V, and 2.0 V, respectively). f CV curves (blue, light blue, cyan, green, and purple curves correspond to scan rates of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mV s−1, respectively). g GCD curves (blue, light blue, green, purple, and red curves correspond to specific currents of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 A g−1, respectively) of ZVO||NVO cell. h The initial capacity and the cycle number under the corresponding specific current of ZVO||NVO cell compared with other works30,63,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80. All electrochemical measurements above were performed at ~25 °C.

Figure 3e compares the performance rate of the full cells assembled with three NVO positive electrodes. It was observed that while the 1.8 V sample had a lower initial capacity than the 2.0 V sample at 0.2 A g−1, it outperformed the other two samples at high currents, specifically at 10 A g−1, demonstrating a desired rate performance. To quantitatively evaluate the trade-off between specific energy and rate performance resulting from the reduced upper cut-off voltage, we systematically compared the gravimetric energy densities of cells operated at 2.0 V and 1.8 V across a range of specific currents (Fig. S13). Although lowering the voltage window inevitably decreases the nominal specific energy (Energy = Capacity × Voltage), the discharge plateau remains largely unchanged, meaning that the actual energy loss is less severe than the nominal voltage reduction would suggest. At low specific currents (<2 A g−1), the 2.0 V cell delivers higher specific energy owing to its larger specific capacity, with the 1.8 V cell showing a reduction of approximately 15.4–19.1%. However, at higher specific currents, the situation reverses: the 1.8 V cell exhibits higher specific energy because its significantly enhanced ion transport kinetics and reduced polarization enable more efficient utilization of active material. This rate-dependent crossover highlights the application-dependent balance point between specific energy and rate performance. For energy-oriented scenarios, the 2.0 V configuration remains advantageous, while for high-power and long-life applications, the 1.8 V configuration offers a more favorable compromise. Furthermore, the modeling framework developed in this study provides a generalizable means to identify such operating windows for other electrode systems by quantitatively balancing energy and power requirements under different working conditions. To validate the positive impact of the matching state of ZVO||NVO on the electrochemical performance of AZIBs, the battery was assembled with an NP ratio of 2 and tested under a voltage window of 0.2–1.8 V. As shown in Fig. 3f, the battery exhibits distinct pairs of oxidation-reduction peaks, with high reduction potentials at 0.75 V and 1.65 V. Additionally, the battery demonstrates a high specific capacity of 310 mAh g−1 at a specific current of 0.1 A g−1, which surpasses all other reported Zn-metal-free AZIBs (Fig. 3g). Stable cycling performance was achieved in full-cell tests (Fig. 3h), with over 4500 cycles at 2 A g−1 and more than 12,000 cycles at 5 A g−1, maintaining over 80% of the initial capacity (Fig. S14). For a comprehensive comparison, Table S10 benchmarks this work against recently reported AZIBs based on zinc metal negative electrodes or dual-intercalation systems. The kinetically matched system developed here achieves a high initial specific capacity and sustained cycling stability across various specific currents, as quantified in the table, contributing to the development of AZIBs with balanced specific energy and durability. This highlights the benefits of a metal-free design and emphasizes the crucial role of dynamic matching between the positive and negative electrodes in determining battery performance.

To overcome the limitation of using a single electrode pairing (ZVO||NVO) in the aforementioned experiments and to verify the broader applicability of the kinetic matching theory across various electrode systems, VOPO4 (VOP) and V2O5·nH2O (VOH) were selected as intercalation-type positive electrodes with tunable interlayer spacing for electrochemical performance evaluation. By fixing ZVO as the negative electrode to control variables, this approach enables elucidation of the mathematical correlation between interlayer spacing in positive electrode materials and ionic diffusion kinetics matching. Both positive electrodes feature tunable interlayer spacing, which was adjusted through the intercalation of aniline molecules into VOP and potassium ions into VOH. The structural modifications were confirmed by XRD to verify the changes in interlayer spacing.

As shown in Fig. S15a, the XRD pattern reveals changes in the interlayer structure, where potassium ion intercalation into VOH induces a decrease in interlayer spacing from 1.147 to 1.067 nm due to electrostatic attraction between VOH and potassium ions. Consequently, the potassium ion-modified VOH (KVOH) exhibits an increased capacity of 3.56 times, as demonstrated in Fig. 4a. Additionally, the potential difference of the redox peaks significantly decreases from 0.147 to 0.003 V, which notably suppresses electrode polarization. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) curves shown in Fig. 4b exhibit a noticeable decrease in impedance, with the charge transfer resistance (Rct) reducing from 9.497 to 0.435 Ω, and the Warburg impedance (Rw) dropping from 11.500 to 5.413 Ω. Furthermore, the rate-performance comparisons in Fig. 4c confirm that regulating the interlayer spacing significantly enhances the rate capability. When the specific current increased from 0.1 to 10 A g−1, the capacity retention increased from 55 to 77%. In contrast, Fig. S15b reveals that aniline intercalation causes the (001) peak of the modified VOP electrode (PA-VOP) to shift from 11.8° to 5.5°, indicating an expansion of the interlayer spacing (1.571 nm) compared to VOP (0.733 nm). In terms of optimizing electrochemical performance, VOP and PA-VOP exhibit a similar trend to VOH and KVOH. As shown in Fig. 4d, both VOP and PA-VOP exhibit a broad voltage window of 0.5–2.2 V in CV tests. A notable 3.5-fold capacity enhancement from 68.5 to 239.6 mAh g−1 is observed for PA-VOP following interlayer expansion, while KVOH exhibits a 3.6-fold enhancement in capacity when tested with the same ZVO. Quantitative analysis of the CV curves confirms that Zn2+ intercalation remains the dominant charge storage mechanism in the full cells, with the diffusion-controlled process contributing over 60% of the total capacity at 0.2 mV s−1. The observed improvements in capacity, together with the subtle shifts in redox peak positions, are primarily attributed to the expanded interlayer spacing of the positive electrode materials. This structural modification facilitates faster zinc-ion diffusion and reduces kinetic mismatches between the negative and positive electrodes, thereby enhancing overall ion transport efficiency. As a result, the electrochemical performance, including rate capability and cycle stability, is significantly improved. These findings underscore that the enhanced behavior is mainly driven by structural and kinetic optimizations, rather than by alternative charge storage contributions such as proton pseudocapacitance (Fig. S16). At the same time, the peak voltage difference decreased from 0.844 to 0.465 V, the Rct decreased from 32.170 to 8.837 Ω, and the Rw reduced from 288.900 to 5.628 Ω. Additionally, the capacity retention improved from 31 to 45% with the specific current increased from 0.1 to 10 A g−1. Furthermore, the zinc ion intercalation kinetics of VOP and VOH before and after lattice regulation were quantitatively assessed using GITT, as shown in Fig. S17. Pre-intercalation significantly enhances the zinc ion diffusion coefficients of both VOH and VOP, where the natural logarithm of the diffusion coefficient for VOH increased from the range of [−12.280, −8.879] to [−10.890, −9.785], while the distribution range for VOP shifted from [−15.493, −9.215] to [−14.640, −8.879], aligning them more closely with the diffusion kinetics of ZVO. Consequently, the optimized electrodes exhibit both increased capacity, reduced polarization resistance, and enhanced rate performance. These findings confirm that the electrochemical performance of vanadium-based positive electrodes is critically governed by their kinetic compatibility with the ZVO negative electrode, thereby substantiating the broader applicability of the electrode kinetics matching framework.

a CV curves, b EIS curves (symbols represent the raw data, solid lines represent the fitted data, and the error is summarized in Table S11), and c the rate performance comparison of the ZVO||VOH cell before and after positive electrode intercalation. d CV curves, e EIS curves (symbols represent the raw data, solid lines represent the fitted data, and the error is summarized in Table S11), and f the rate performance comparison of the ZVO | | VOP cell before and after positive electrode intercalation. (Throughout a–f, blue corresponds to cell before positive electrode intercalation and red corresponds to cell after intercalation). g Comparison of zinc ion diffusion coefficients for each electrode material, and the CSI of the full cells based on 5 different negative electrodes (the error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of diffusion coefficients calculated at multiple voltage points during cycling for each full cell. The number of voltage points (n) for each material is: ZVO: n = 69, TiS2: n = 58, MXene: n = 47, MoO2: n = 53, PTCDI: n = 18, NVO-1.8 V: n = 64, PA-VOP: n = 72, KVOH: n = 33, NVO-2.0 V: n = 68, VOP: n = 59, VOH: n = 42). And comparison of the redox potential difference (PD), mass-specific capacity (Cm) at 1 mV s−1, capacity retention (CR, specific current increased from 0.1 to 1 A g−1), charge transfer resistance (Rct), and Warburg resistance (Rw) of the 5 negative electrodes in pair with 3 positive electrodes before and after matching. All electrochemical measurements above were performed at ~25 °C. (Green hatched, purple hatched, and yellow hatched filling represent mismatched cells with NVO, VOH, and VOP positive electrodes, respectively; while solid green, purple, and yellow filling denote their matched counterparts.).

Development of a semi-empirical model for electrode kinetic matching status in dual-intercalation AZIBs

Building on the consistent optimization effect of intercalation kinetics matching on electrochemical performance in the aforementioned systems, a rational, tunable strategy for optimizing electrode pairings in dual-intercalation AZIBs can be further developed. Notably, both the expansion and contraction of interlayer spacing result in enhanced electrochemical performance, indicating the existence of an optimal kinetic range for ionic diffusion. The degree of electrode matching status fundamentally hinges on the extent of overlap between the respective kinetic windows of the positive and negative electrode. Therefore, by modulating interlayer spacing to either accelerate or decelerate diffusion kinetics, the kinetic overlap between electrodes is increased relative to the initial mismatch, thereby improving overall cell performance. The magnitude of this overlap directly correlates with the degree of electrochemical enhancement. The varying degrees of overlap determine the extent of improvement in electrochemical performance. To further substantiate the hypothesis of kinetic range matching between electrodes, a series of positive electrode materials with varying interlayer spacings were investigated to quantify their corresponding Zn2+ diffusion coefficients relative to the ZVO negative electrode (Table S2). The derivation of the diffusion matching model is grounded in diffusion coefficients calculated from Fick’s second law48, which governs the temporal evolution of concentration profiles under diffusive transport and is mathematically expressed as Eq. (1):

Where \({C}_{{Zn}}\) is the concentration of the diffusing Zn2+, t is time, and D denotes the diffusion coefficient. Then, to enable the comparison and eventual matching of diffusion coefficients between different electrodes within an electrochemical system, the solution of Fick’s second law is represented as Eq. (2):

Here, Di denotes the diffusion coefficient corresponding to a specific current value i; F is Faraday’s constant (96485 C mol−1); Vm is the molar volume of the electrode material; ZA is the ionic charge number (for Zn2+, ZZn = 2); S is the contact area between the electrode and electrolyte; \(dE/d\delta\) represents the slope of the Coulomb titration curve, reflecting the voltage response to compositional changes; and \({dE}/d\sqrt{t}\) captures the relationship between potential and the square root of time.

Balancing the ion diffusion kinetics between the negative and positive electrode and evaluating their impact on overall electrochemical performance requires a statistical analysis of the diffusion coefficients for each electrode material. To enable quantitative comparison across this broad range of diffusion coefficients, the base-10 logarithm (\({\mathrm{lg}}D\)) is applied. The mean (\(\bar{{\mathrm{lg}}D}\)) and standard deviation (\({\sigma }_{{\mathrm{lg}}D}\)) of the logarithmic diffusion coefficients over the entire charge-discharge cycle are calculated to evaluate both the overall diffusion level and its temporal stability. These are defined as Eqs. (3) and (4):

Where n is the number of data points, and \({\mathrm{lg}}{D}_{i}\) denotes the logarithmic value of the zinc ion diffusion coefficient at each step of the charge-discharge process. The mean and standard deviation of \({\mathrm{lg}}D\) for each electrode material were used to construct a statistical distribution range for their respective intercalation kinetics. To quantitatively evaluate the degree of kinetic mismatch between two electrodes, a CSI was proposed, which serves as a metric for the divergence in their ion diffusion kinetics. A higher CSI value reflects a greater degree of kinetic disparity. The CSI is defined as Eq. (5):

This calculation formula provides a quantitative feature for evaluating the dynamic matching status between electrodes. The applicability and predictive capability of this approach are validated by the observed variations in CSI values across three representative positive electrode materials (NVO, VOP, and VOH), as summarized in Table S3, each showing distinct enhancement effects based on their kinetic alignment with ZVO.

Building upon the established set of kinetic evaluation equations, we further validated their universality by expanding the study to include four additional negative electrode materials beyond Zn3V3O8 (ZVO): TiS2, MXene, 3, 4, 9, 10-perylenetetracarboxylic diimide (PTCDI), and MoO2. These materials were systematically paired with various layered positive electrodes, and their full-cell electrochemical performances were evaluated (Fig. 4g and Tables S4–S8). To extract deeper correlations, the XGBoost machine learning algorithm was employed to model the relationship between diffusion-derived features and electrochemical performance, particularly capacity retention under high specific currents (Fig. 5a). XGBoost was selected due to its well-established computational efficiency and predictive accuracy, which have supported its widespread application in data-rich scientific and industrial domains. To quantify feature relevance, we computed Pearson correlation coefficients between derived diffusion metrics and electrochemical outcomes (Fig. 5b). In the resulting heatmap, darker tones reflect stronger correlations. Among all features, the Diffusion Ratio (DR, defined as the ratio of mean ion diffusion coefficients) and the CSI exhibited the strongest correlations with electrochemical performance. These two metrics also emerged with the greatest feature importance in the XGBoost model (Fig. 5c, d), underscoring their dominant influence on electrochemical behavior. Notably, the significance of DR was consistent with insights from finite element simulations, which suggest that closer alignment of ion diffusion kinetics between electrodes facilitates more efficient charge transport and rate performance. The machine-learning-derived optimal DR range (0.936−1.020) is tightly centered near unity, reflecting the critical principle of kinetic balance between the negative and positive electrode. The slight asymmetry of this range may indicate a modest tolerance for slightly faster negative electrode kinetics, which arises naturally from the composition of the training dataset: negative electrode materials generally exhibit higher diffusion rates than positive electrodes, producing a minor skew of DR values below 1, as shown in Supplementary Table S9. Experimental validation of the DR descriptor across 30 distinct electrode pairs via GITT measurements confirms strong agreement with the predicted optimal range (0.936–1.020), as detailed in Table S9, supporting its utility for predicting and optimizing full-cell performance. Thus, while the model accommodates minor asymmetry, the overarching design guideline emphasizes the achievement of well-matched intercalation kinetics to ensure efficient ion flux, minimize polarization, and maximize both rate capability and cycling stability in dual-intercalation AZIBs. The XGBoost model exhibited strong predictive capability when utilizing both the DR and CSI descriptors, achieving a high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.886) and a low root mean square error (RMSE = 0.067) (Fig. 5e). To ensure the robustness of our modeling approach, we conducted a comparative evaluation of multiple machine-learning algorithms, including Linear Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), Lasso, and Ridge Regression. As summarized in Fig. S18, all of these models exhibited substantially lower predictive accuracy compared with XGBoost: their R2 values (0.528, 0.610, 0.443, 0.547, and 0.573) were considerably below that of XGBoost (0.886), while their RMSE values (0.136, 0.124, 0.148, 0.134, and 0.130) were consistently higher than XGBoost’s 0.067. This quantitative comparison highlights XGBoost’s robust predictive capability, attributable to its ability to effectively capture complex nonlinear feature interactions in our dataset. The inclusion of these comparative results in the Supporting Information not only provides readers with a broader methodological context but also reinforces the rationale for selecting XGBoost as the most suitable and robust framework for this study. Notably, the model identified electrode pairs with DR values in the range of 0.936–1.020 as those most likely to achieve the top 30% electrochemical performance. The CSI metric also proved effective, with high-performing systems predominantly falling within a CSI range of 0.241–1.013 (Fig. 5f). To evaluate the robustness of this design criterion, sensitivity analyses were performed using alternative thresholds of top 10% and top 50%. While the top 10% threshold yielded very narrow parameter ranges (DR: 0.946–0.956; CSI: 0.801–0.803) with insufficient data points for practical screening, the top 50% threshold produced broad ranges (DR: 0.936–1.114; CSI: 0.148–1.244) that introduced high performance variance and reduced predictive specificity. Crucially, the central tendencies and directional correlations between DR, CSI, and full-cell electrochemical performance remained consistent across all thresholds, with strong mutual overlap between the derived ranges. These results confirm that the proposed design rule is inherently robust, providing reliable guidance for electrode selection and screening while maintaining practical applicability for different material systems (Fig. S19). Introduced in this study as two quantitative descriptors, DR and CSI capture the degree of intercalation kinetics matching between electrode pairs. The CSI quantifies the distributional spread of Zn2+ diffusion coefficients across available pathways. Optimal values (0.241–1.013) reflect uniform diffusion landscapes that enable rapid kinetics, whereas values outside this range indicate inhomogeneous transport and localized bottlenecks that exacerbate polarization. The DR measures kinetic compatibility between electrodes, with values of 0.936–1.020 corresponding to balanced intercalation/deintercalation dynamics, and deviations beyond this range revealing electrode-specific kinetic mismatches. Machine-learning feature importance analysis identified CSI and DR as the most predictive descriptors, a conclusion further corroborated by experimental validation. Among the 30 combinations evaluated, those falling within the optimal DR range (0.936–1.020) and CSI range (0.241–1.013) consistently exhibited reduced redox peak separations, lower charge-transfer (Rct) and Warburg (Rw) resistances, higher specific capacities, and larger capacity retention as the specific current increased from 0.1 to 1.0 A g−1 (Fig. 4g). More broadly, this work establishes a data-driven, formula-based approach that transforms the previously qualitative understanding of ion diffusion kinetics matching into a quantitative design rule, paving the way for rational electrode intercalation synergy and system-level optimization in advanced flexible energy storage technologies.

a An overview of ML-based model. b Heatmap analysis between all features, including average diffusion coefficients of positive electrode (+D) and negative electrode (−D), standard deviation of positive electrode (+V) and negative electrode (−V), DR, Sum of standard deviation (S), overlap_index (OI), CSI, weighted diffusion discrepancy (WD), Asymmetry Index (AI), RC, stability (Sta). c SHAP values of feature importance. d Order of relative contribution among variables. e Modeling the performance of features for single-target prediction using the XGBoost model. f The predicted value numerical range corresponding to the DR and CSI ranges, the blue solid line represents all predicted sample values, the orange dashed line indicates the values with a performance threshold of top 30%, and the gray dashed lines demarcate the feature value range corresponding to the top 30% density distribution.

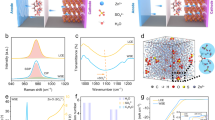

Fabrication of all-hydrogel AZIBs with matched kinetics for flexible applications

To validate the practical applicability of the above empirical models in guiding electrode material selection for dual-intercalation flexible AZIBs, the previously characterized ZVO||NVO electrode pairing, which simultaneously satisfies the screening criteria for both DR (0.946) and CSI (0.321), was selected to construct a Zn-free intercalation-type full cell for subsequent electrochemical performance evaluation. To establish a kinetically matched state, the ionic diffusion kinetics matching rate was tuned to 68% via cutoff voltage modulation. Building upon this foundation and ensuring full electrode flexibility, both NVO and ZVO were integrated into a PAA-Ag hybrid hydrogel precursor solution to fabricate self-supporting, flexible hydrogel electrodes. Ag nanoflakes were incorporated as a conductive filler to form an efficient percolation network within the hydrogel electrode, substantially enhancing electronic conductivity. Four-probe measurements confirmed that the sheet resistance decreased from 1.580 kΩ to 307.4 mΩ following the addition of Ag nanoflakes (Fig. S20), demonstrating their crucial role in improving charge transfer kinetics. The SEM morphology of the hydrogel electrode (inset of Fig. 6a) reveals a porous network structure, which facilitates ion transport while maintaining good elasticity. The mechanical properties of these hydrogel electrodes are presented in Fig. 6a, demonstrating that both the hydrogel negative electrode and hydrogel positive electrode achieve an elongation rate of nearly 400% and a tensile strength of 100 kPa, surpassing even the pure hydrogel matrix without host materials (24 kPa breaking stress at 230% strain). This enhancement can be attributed to the hydrogen bonding interactions between hydroxyl groups on the surfaces of ZVO||NVO vanadate crystals and the hydrogel network. The incorporation of rigid crystalline domains helps to bear part of the mechanical stress and even undergoes orientation alignment under strain, leading to increased hydrogel strength. Additionally, the introduction of more non-covalent interactions further contributes to the improved stretchability of the network. Moreover, the influence of gel encapsulation on the intrinsic electrochemical properties of the host materials was minimized through concentration optimization. For the negative electrode (Fig. 6b), increasing the ZVO concentration to 300 mg mL−1 allowed the hydrogel electrode to achieve electrochemical behavior comparable to that of the pristine ZVO electrode. Similarly, for the positive electrode (Fig. 6c), raising the NVO concentration to 200 mg mL−1 resulted in a CV curve closely resembling that of the pristine NVO electrode, with well-defined oxidation-reduction peaks. Higher loadings, while enhancing tensile strength, markedly reduced elongation-at-break due to restricted polymer chain mobility. Excessive loadings further disrupted the crosslinking density of the PAA network, compromising structural cohesion and preventing the fabrication of robust free-standing electrodes. Therefore, mass loadings were optimized at 200 mg mL−1 for the positive electrode and 300 mg mL−1 for the negative electrode.

a Stress-strain curves of the hydrogel electrodes, blue, yellow, and red curves correspond to ZVO-filled, NVO-filled, and unfilled PAA/EG hydrogel, respectively. (inset: SEM morphology of the hydrogel electrode). b, c CV curves of hydrogel positive electrode (blue, yellow, and red curves correspond to loading concentrations of 100, 200, and 300 mg mL−1) and negative electrode (blue, yellow, and red curves correspond to loading concentrations of 60, 100, and 200 mg mL−1) at different active material ratios. d CV curves (red, purple, green, light blue, and blue curves correspond to scan rates of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mV s−1). e GCD curves (blue, light blue, green, purple, and red curves correspond to specific currents of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.5, and 5.0 mA cm−2), and f cycling performance of the all-hydrogel AZIB (red dotted line represents capacity retention, and the blue dotted line represents Coulombic efficiency). g Photographs of the series-connected AZIBs operating an LED display and maintaining stable performance under twisting and bending states. h Hydrogel-based AZIBs integrated with flexible circuits were demonstrated as wearable power sources by adhering them to the hand, showcasing their potential for on-skin energy applications. i CV curves recorded at 10 mV s−1 and capacity retention under 40% stretching-releasing cycles. j Ragone plot of the device compared with other works50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61. All electrochemical measurements above were performed at ~25 °C.

Considering that the hydrogen bond-induced adhesion between the electrode and electrolyte improves interfacial contact, enhances synergy, and strengthens the connection, the host materials are firmly anchored to the electrolyte surface, reducing interfacial impedance and shortening ion transport pathways. Therefore, a PVA-based hydrogel electrolyte was integrated with PAA hydrogel-based electrodes to fabricate coplanar flexible AZIBs (Fig. S21). As shown in Fig. 6d, this coplanar cell exhibits stable CV curves within a voltage window of 0.2–1.8 V. The GCD curves in Fig. 6e indicate a high areal capacity of 1.2 mAh cm−2 at a current density of 0.5 mA cm−2. Long-term cycling tests (Fig. 6f) further demonstrate the significant cyclic stability of the fabricated coplanar cell, which retains over 80% of its initial capacity after more than 200 cycles. Notably, the all-hydrogel cell fabricated in this study no longer exhibits the typical deformation constraints seen in previously reported flexible AZIBs with zinc-metal negative electrodes and gel electrolytes, which can only undergo small amplitude deformations in specific directions49. Lateral deformation, bending, or twisting may cause metal plates to fracture or lead to interface delamination, resulting in battery failure. Due to the flexibility of the electrodes, this coplanar cell can adapt to deformations in all directions, including twisting and bending, and can maintain its power supply performance for an LED signboard during deformation, as illustrated in Fig. 6g and Supplementary Movie 1. Also, this intrinsically flexible battery can stably power devices without compromising their wearability, exhibiting adaptability to everyday human motions. For example, integration with a palm-conformable, printed flexible light-emitting device enables this battery to deliver stable power during dynamic hand motions. (Figs. 6h and S22; Supplementary Movie 2). This capability to deform omnidirectionally, while maintaining stable electrochemical performance under mechanical stress, is critical for powering wearable devices during dynamic motion. This flexible cell was subjected to 40% strain cycling to quantitatively validate conformance with wearable requirements. It retains stable electrochemical performance even after 120 stretching-releasing cycles (Fig. 6i), demonstrating its robust mechanical resilience and long-term durability under deformation. As shown in Fig. S23, the devices utilize the hydrogel electrolyte itself as an encapsulation layer, exhibiting good water retention with only 0.041 wt% loss after 288 h under ambient conditions, thereby ensuring operational stability without additional packaging. Moreover, the all-hydrogel cell (4 cm2) achieves an energy density of 1070 µWh cm−2 (0.8 mW cm−2), while maintaining a high-power density of 4.0 mW cm−2 (248.2 µWh cm−2), as shown in Fig. 6j. These performances metrics are among the high values reported for the Zn-metal-free AZIBs in terms of areal capacity (<500 µWh cm−2 at 0.1 mA cm−2) and cyclic lifespan (<100 cycles)50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61, highlighting the notable performance of this developed flexible AZIBs. Moreover, it substantiates the positive impact of kinetically matched electrode pairings, as defined by the empirical model proposed in this study, on the performance of dual-intercalation AZIBs. This provides a theoretical framework for electrode material selection and performance prediction in the design of not only dual-intercalation but also broader classes of flexible AZIBs.

In summary, this study quantitatively defines ionic diffusion kinetics matching status in dual-intercalation electrode systems through a semi-empirical formula, establishing mathematical criteria for efficient electrode intercalation synergy. Although not applicable to non-intercalation or hybrid systems, this strategy provides broadly useful guidance for electrode pairing in dual-intercalation AZIBs under standard conditions, underscoring the importance of system-specific kinetic considerations in future battery design. By correlating theoretical calculations with experimental results, it clarifies the relationship between electrode matching and full-cell performance, providing a reliable reference model for performance prediction and a guiding principle for optimizing dual-intercalation AZIBs. Building on this, the interlayer spacing of the NVO positive electrode was tuned via voltage excitation to achieve optimized matching with the widely applicable ZVO negative electrode. The resulting aqueous AZIBs exhibited a specific capacity of 310 mAh g−1 and notable cycling stability exceeding 12,000 cycles at 5 A g−1. To further validate the applicability of the proposed empirical equation in guiding electrode selection for flexible Zn-metal-free systems, a kinetically matched ZVO||NVO electrode pair was embedded into a PAA hydrogel matrix and assembled with a PVA-based hydrogel electrolyte via hydrogen bonding, resulting in the construction of an all-hydrogel AZIB. This battery demonstrated omnidirectional deformability, high durability, and stable functionality under mechanical deformation, achieving an energy density of 1070 µWh cm−2 (4 cm2) while maintaining electrochemical stability over 120 stretching-releasing cycles. This intrinsically flexible, stretchable, and high-performance AZIB design presents a promising pathway for advancing flexible energy storage systems to power next-generation wearable and portable electronic devices, seamlessly adapting to a wide range of human motions and body curvatures.

Methods

Materials

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Mw 89000-98000, 98-99% hydrolyzed), vanadium pentoxide (V2O5, ≥99.5%), aniline (≥99.5%), ammonium metavanadate (NH4VO4, ≥99%), N-Methylpyrrolidone (NMP, ≥99.5%), ammonium persulfate (APS, ≥98%), and N, N’-methylenebisacrylamide (MBAA, ≥99%) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co. Ltd. Zinc acetate dihydrate (CH3COO)2Zn·2H2O (98%), ethylene glycol (EG, 98%), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, ≥85 wt. % in H2O, ≥99.99% metals basis), potassium sulfate (K2SO4, 99%), isopropanol (≥99.9%), ethanol (>99.9%), Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, 99.9%) and acrylic acid (>99%) was purchased from Shanghai Macleans Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Oxalic acid (H2C2O4·2H2O, ≥99.5%) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, ≥ 30%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Zinc trifluoromethanesulfonate (Zn(OTf)2, 98%) was purchased from Energy Chemical. Super P ( > 99.9%) was purchased from Feynman Biotechnology Tech Co., Ltd. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, average Mw ~1,100,000, ≥99.5%) was purchased from Nanjing Moges Energy Technology Co., Ltd. Silver nanoflakes (96.5%) was purchased from Jiangsu XFNANO Materials Tech Co., Ltd. Zinc plate (99.99%) was purchased from Chengshuo Metal Materials Co., Ltd., and deionized water was used for all experiments.

Preparation of electrode materials

Synthesis of Zn3V3O8

To synthesize the negative electrode host materials62, 10 mmol of (CH3COO)2Zn·2H2O and 10 mmol of NH4VO3 were added to 60 mL of deionized water and stirred magnetically at 90 °C for 5.5 h to form a sol. The sol was then dried in an oven at 70 °C for 72 h. After drying, the obtained bulk product was ground into a fine powder and annealed at 750 °C for 9 h under a 5% Ar/H2 mixed gas atmosphere with a heating rate of 4 °C min−1, then cooled naturally to obtain the target product.

Synthesis of layered NH4V4O10

To synthesize the positive electrode host materials63, 4.67 mmol of NH4VO3 and 0.71 mmol of H2C2O4·2(H2O) were dissolved in 70 mL of distilled water and stirred at 25 °C for 1 h. The solution was then transferred to a hydrothermal autoclave and heated at 180 °C for 2 h. After the reaction, the product was naturally cooled to 25 °C, washed sequentially with deionized water and ethanol three times, and dried at 60 °C to yield the target product.

Synthesis of VOP and PA-VOP

To synthesize VOP64, 2.4 g of V2O5 powder and 13.3 mL of H3PO4 were added to 57.7 mL of deionized water and stirred for 2 h. The mixture was then heated in a hydrothermal reactor at 120 °C for 16 h. After the reaction, the product was centrifuged, washed, and dried at 60 °C to obtain VOP.

Subsequently, PA-VOP was synthesized using an ultrasonic exfoliation and self-assembly process. For this, 100 mg of VOPO4 powder was dispersed in 7 mL of isopropanol, and the solution was sonicated for 30 min. After centrifugation, the exfoliated sheets were transferred into an aniline solvent and stirred for 24 h. The product was then centrifuged, washed, and dried under vacuum at 60 °C.

Synthesis of KVOH and VOH

To synthesize KVOH65, 0.364 g of V2O5 was dissolved in 50 mL of deionized water, and 2 mL of H2O2 was added. Separately, 0.087 g of K2SO4 was dissolved in 30 mL of deionized water. The two solutions were mixed under magnetic stirring for 0.5 h and then heated at 120 °C for 6 h. The resulting precipitate was washed three times with deionized water and ethanol and dried in an oven at 60 °C for 10 h to obtain the green powder KVOH. For VOH, the same procedure was followed without adding K2SO4.

Fabrication of hydrogel electrolytes and testing electrodes

To prepare the electrolyte56, 4.5 g of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) powder was added to 40 mL of a mixed solution containing 1 M Zn(OTf)2 in water and ethylene glycol. The mixture was stirred at 90 °C until it dissolved uniformly and then froze at −40 °C for crosslinking to form the hydrogel.

For the testing electrode, the electrode slurry was formulated by thoroughly mixing the active material (lab-synthesized), Super P, and PVDF in a mass ratio of 7:2:1 within NMP solvent. This slurry was then manually single-side coated onto the titanium mesh (99.99%, 200 meshes, thickness: 0.5 mm, pore size: 0.077 mm) utilizing a coating brush. Following drying under 60 °C, the electrode sheets were punched into circular disks with an electrode cutter (MSK-T10, Shenzhen Kejing Star Technology Co., Ltd.), achieving a targeted active material mass loading of 1–2 mg cm−2. Notably, the basic electrochemical performance of the electrode materials was tested by assembling coin cells (CR2032, 20 × 20 × 3 mm, stainless steel 304) with electrode sheets (φ = 12 mm) and hydrogel electrolytes (φ = 16 mm, volume: 0.26 ± 0.05 cm3). For the half-cell test, zinc foil (thickness: 80 μm) was used as the negative electrode.

Fabrication of hydrogel electrodes and assembled AZIBs

A precursor solution was prepared with ethylene glycol and water in a 2:1 volume ratio, followed by the addition of 15 mL of acrylic acid to 35 mL of the mixed solution. To this, 150 mg of Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, 20 mg of MBAA, and 150 mg of APS were added. The mixture was stirred thoroughly, and ethanol (50 vol% relative to the total precursor volume) was added to retard the spontaneous polymerization process, yielding the polyacrylic acid (PAA) precursor solution.

The hydrogel electrodes were formulated by homogeneously mixing active electrode material (NH4V4O10 for the positive electrode or Zn3V3O8 for the negative electrode) with Ag nanoflakes in the PAA hydrogel precursor solution. The concentration of the active material was systematically varied from 60 to 300 mg mL−1, while the concentration of Ag nanoflakes was maintained constant at 400 mg mL−1 to ensure consistent electrical conductivity. The resulting mixtures were poured into Petri dishes and gelled at 60 °C to form self-supporting electrode films with a uniform thickness of approximately 0.1 mm. These freestanding hydrogel electrodes were then cut into rectangular strips of desired dimensions (typically 10 mm × 25 mm) using a surgical blade. The electrolyte and substrate consisted of the PVA hydrogel, prepared according to the procedure described in the previous section of hydrogel electrolyte. The PVA precursor solution was cast in a Petri dish and gelled at −40 °C, forming a transparent, freestanding film with a thickness of approximately 1.0 mm. A co-planar battery architecture was constructed by arranging the discrete positive and negative hydrogel electrode strips in parallel on the same PVA hydrogel substrate, maintaining a defined insulating gap of 0.2 mm between them to prevent internal short-circuiting. The assembly was fully encapsulated by casting a second layer of PVA precursor solution over the electrodes and substrate, followed by a final gelling step at −40 °C. This created a monolithic, all-hydrogel structure with integrated ionic continuity. External electrical connections were established by attaching flexible conductive adhesive tapes to the exposed terminals of the hydrogel electrodes, enabling electrochemical testing and the configuration of devices in series. The electrochemical properties of the electrodes were evaluated using CV, GCD, and EIS methods via an electrochemical workstation. Additionally, the mechanical properties of the hydrogel electrodes were measured and compared using a universal testing machine.

Characterizations