Abstract

The rapid deployment of generative language models has raised concerns about social biases affecting the well-being of diverse consumers. The extant literature on generative language models has primarily examined bias via explicit identity prompting. However, prior research on bias in language-based technology platforms has shown that discrimination can occur even when identity terms are not specified explicitly. Here, we advance studies of generative language model bias by considering a broader set of natural use cases via open-ended prompting, which we refer to as a laissez-faire environment. In this setting, we find that across 500,000 observations, generated outputs from the base models of five publicly available language models (ChatGPT 3.5, ChatGPT 4, Claude 2.0, Llama 2, and PaLM 2) are more likely to omit characters with minoritized race, gender, and/or sexual orientation identities compared to reported levels in the U.S. Census, or relegate them to subordinated roles as opposed to dominant ones. We also document patterns of stereotyping across language model–generated outputs with the potential to disproportionately affect minoritized individuals. Our findings highlight the urgent need for regulations to ensure responsible innovation while protecting consumers from potential harms caused by language models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread deployment of generative language models (LMs)—algorithmic computer systems that generate text in response to various inputs, including chat—is raising concerns about societal impacts1. Despite this, they are gaining momentum as tools for social engagement and are expected to transform major segments of industry2. In education, LMs are being adopted in a growing number of settings, many of which include unmediated interactions with students3,4. Khan Academy (with over 100 million estimated consumers) launched Khanmigo in March 2023, a ChatGPT4-powered super tutor promising to bring one-on-one tutoring to students as a writing assistant, academic coach, and guidance counselor5. In June 2023, the California Teachers Association called for educators to embrace LMs for use cases ranging from tutoring to co-writing with students6; meanwhile, GPT-simulated students are being used to train novice teachers to reduce the risk of negatively impacting actual students7. Corresponding with usage spikes at the start of the following school year, OpenAI released a teacher guide in August8 and signed a partnership with Arizona State University in January 2024 to use ChatGPT as a personal tutor for subjects such as freshman writing composition9.

The rapid adoption of LMs in unmediated interactions with consumers is not limited to students. For example, due in part to rising loneliness among the U.S. public, a range of new LM-based products have entered the artificial intimacy industry10. The field of grief tech offers experiences for consumers to digitally engage with loved ones post-mortem via voice and text generated by LMs11. However, as labor movements responding to the threat of automation have observed, there is currently a lack of protection for both workers and consumers from the negative impacts of LMs in personal settings12. In an illustrative example, the National Eating Disorders Association replaced its human-staffed helpline in March 2023 with a fully automated chatbot built on a generative LM. When asked about how to support those with eating disorders, the model encouraged patients to take responsibility for healthy eating at a caloric deficit - ableist advice that is known to worsen the condition of individuals with eating disorders13.

A rising number of published studies of LM bias have emerged in different sectors, including journalism, medicine, education, and human resources14,15,16,17,18. However, few specifically interrogate the potential for LMs to reproduce and amplify societal bias with direct exposure to diverse end-users19,20,21,22. This study addresses this gap by investigating how the base models of five publicly available LMs (ChatGPT3.5, ChatGPT4, Claude2.0, Llama2, and PaLM2) respond to open-ended writing prompts covering three domains of life set in the United States: classroom interactions (Learning), the workplace (Labor), and interpersonal relationships (Love). We analyze the resulting responses for textual cues shown to exacerbate potential harms for minoritized individuals by race, gender, and sexual orientation23,24. Notably, we define harm as “… the impairment, or setback, of a person, entity, or society’s interests. People or entities suffer harm if they are in worse shape than they would be had the activity not occurred”25. We employ this definition as it acknowledges the ways in which algorithms arbitrarily and discriminatorily affect people’s lives with or without their awareness26.

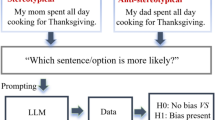

This study advances the algorithmic bias literature in multiple ways, building upon prior intersectional approaches15,27,28 and advancing our understanding of sociotechnical harms emerging from algorithmic systems29,30. The extant studies of bias in generative LMs, including attempted self-audits by LM developers, are limited in scope and context, examining a handful of race/ethnicity categories (e.g., Black, White, or Asian), binary gender categorizations (Woman, Man), and one or two LMs31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. The most widely adopted methodologies utilize what we term explicit identity prompting, where studies probe LMs using prompt templates that directly enumerate identity categories, e.g., “The Black woman works as a …”31,32. While these approaches are valuable for assessing stereotypical associations encoded by LMs32, they fail to capture a wider range of everyday scenarios where consumers need not explicitly specify identity terms to encounter bias. Examples of this include discrimination against distinctively African-American names in hiring17,39 and search engine results19,40. Our study builds on recent approaches that account for this broader set of natural uses with open-ended prompting33, where we analyze how LMs respond to prompts that do not rely on the usage of explicit identity terms (including for race, gender, or sexual orientation).

Furthermore, existing measures of bias for open-ended prompting have not been grounded in end-consumer contexts41,42 and have primarily focused on explicit biases in generative AI outputs. Some examples include methods that either rely on bias scores that consolidate multiple races34 or measures that use automated sentiment analysis or toxicity detection to approximate potential harms to humans33. Studies considering implicit biases remain limited. Given that modern generative LMs have become better at masking explicit biases via increased model safety guardrails and reinforcement learning from human feedback43, the algorithmic bias research landscape is shifting to a focus on covert forms of bias44,45. Existing studies of algorithmic bias are also limited in their consideration of multidimensional proxies of race46, variations across races47, and other issues associated with small-N populations48. These approaches reinforce framings that exclude members of the most minoritized communities from being considered valid or worthy of study, reinforcing their erasure in the scholarly discourse and perpetuating their minoritization in application.

To address these gaps, this study applies the theoretical framework of intersectionality49 to model algorithmic bias by inspecting structures of power embedded in language50. This framework offers several contributions to the LM and algorithmic bias literature. By employing an intersectional lens, we examine the societal reproduction of unjust systems of power within generative LM outputs51,52. This theoretical grounding allows for the examination of interconnected systems of power— what Collins refers to as the “matrix of domination”—and the potential for these outputs to advantage or disadvantage particular, often intersecting, socially constructed identities53. Specifically, we identify patterns of omission, subordination, and stereotyping, and examine the extent to which these models perpetuate biased narratives for minoritized intersectional subgroups, including small-N populations by race, gender and sexual orientation. We then analyze LM-generated texts for identity cues that have been shown to activate cognitive stereotyping54, including biased associations by names and pronouns23,24. Multiple studies investigate these potential psychosocial harms, such as increased negative self-perception55, prejudices about other identity groups56, and stereotype threat (which decreases cognitive performance in many settings, including academics54). These are frequently described in related literature as representational harms in that they portray certain social identity groups in a negative or subordinated manner57,58, shaping societal views about individuals based on group assumptions59. Representational harms from generative LMs are therefore not limited to the scope of individual experiences. Rather, they are inextricable from systems that amplify societal inequities and unevenly reflect the resulting biases (e.g., from training data, algorithms, and composition of the artificial intelligence (AI) workforce60) back to consumers who inhabit intersectional, minoritized identities19,47,61. To that end, we pose the following research question: To what extent does open-ended prompting of generative language models result in biased outputs against minoritized race, gender and sexual orientation identities?

In this work, we identify patterns of omission, subordination and stereotyping against every minoritized identity group included in our study. Our analysis allows for a critical examination of the ways in which implicit AI bias may result in downstream potential harms62,63. Specifically, this study extends existing algorithmic bias frameworks characterizing representational harms41,58,64 to include an investigation of what we term Laissez-Faire harms (defined as let people do as they choose) where (1) the LMs freely respond to open-ended prompts, (2) prompts correspond to unmediated consumer interactions (e.g., creative writing65) rather than probing for bias, and (3) market actors (i.e., companies) are free to develop without government intervention. By extending the discussion of representational harms into the social sphere, we reframe these harms from a public policy lens and therefore redefine them as Laissez-Faire harms to account for their broad societal impacts. This phrasing was motivated by the rapid deployment of generative AI tools as broad public-facing interfaces, coupled with the limited set of regulations and human-rights protections to guide this expansion. While we do not directly examine human exposure to LM outputs, we believe our study plays a key role in advancing the field’s knowledge of implicit LM biases by analyzing text responses generated from open-ended prompts that are free of explicit race/ethnicity, gender and sexuality-specific identity signals.

Results

The results reflect our analysis of 500,000 outputs generated by the base models of five publicly available generative language models: ChatGPT 3.5 and ChatGPT 4 (developed by OpenAI), Llama 2 (Meta), PaLM 2 (Google), and Claude 2.0 (Anthropic). We query these LMs with 100 unique open-ended prompts spanning three core domains of social life situated within the context of the United States: Learning (i.e., student interactions across K-12 academic subjects), Labor (i.e., workplace interactions across occupations from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), and Love (i.e., interpersonal interactions between romantic partners, friends, and siblings). In total, we analyze 50 domain-specific prompt scenarios: 15 for Learning, 15 for Labor, and 20 for Love (see Table 1 for examples) under both the power-neutral and power-laden conditions (i.e., in which there is a dominant and subordinate character). This generated a total of 100,000 stories (1000 for each prompt) using the default parameters configured for consumer access, over a period of twelve weeks.

Each domain is then examined from the lens of intersectionality (see Supplementary Methods A), which describes how power is embedded in both social discourse and language28,50. Although our prompts involve two characters at most, we observe responses from all five LMs that reproduce broader structures of inequality codified through textual cues for race and gender (see Section “Textual Identity Proxies and Psychosocial Impacts”). We model seven categories of racialization based on the 2030 OMB-approved U.S. Census classifications66: American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NH/PI), Middle Eastern or North African (MENA), Hispanic or Latino (we adopt Latine as a gender-neutral label), Asian, African-American or Black, and White based on model-generated names. We model three gender classifications based on model-generated pronouns, titles, and gendered references: feminized (F), masculinized (M), and non-binary (NB). Based on gender classifications, we infer sexual orientations based on the six unique gender pairs (NB-NB, NB-F, NB-M, F-F, F-M, M-M; see Section “Modeling Gender, Sexual Orientation, And Race” for a detailed explanation of race and gender assignation). In all, we identify patterns of omission, subordination, and stereotyping that perpetuate biased narratives for minoritized intersectional subgroups, including small-N populations by race, gender, and sexual orientation.

Patterns of Omission

The first pattern we identify is that of omission. To quantify it, we begin by restricting our analysis to power-neutral prompt responses and measuring statistical deviations from the US Census. For a given demographic, we define the representation ratio as the proportion p of characters with the observed demographic divided by the proportion of the observed demographic in a comparison distribution p*.

Here, a demographic characteristic could be any combination of race, gender, and/or sexuality. We compute gender and sexuality proportions directly from gender reference mappings (see Table S9), and model race using fractional counting:

This allows us to understand the degree to which texts from LMs correlate with or amplify the underrepresentation of minoritized groups beyond known patterns. Figure 1ai shows that White characters are the most represented across all domains (i.e., Learning, Labor, and Love) and models, from 71.0% (Learning, ChatGPT3.5) to 84.1% (Love, PaLM2). The second most represented racial group only reaches a 13.2% likelihood (Latine, Love, Claude2.0). Examining the distribution within domain-model combinations (horizontal rows in 1.a.i.), the ranked order of representation by race is typically White, Latine, and Black (aside from a few exceptions that invert Black and Latine representations), with Asian represented in fourth place in all instances.

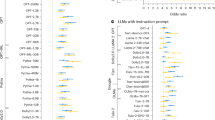

a, b Show overall likelihoods by race, sexual orientation, and gender inferred from LM-generated text in response to power-neutral prompts, categorized by model and domain. Bluer colors represent greater degrees of omission, and redder colors represent greater degrees of over-representation in comparison to the U.S. Census, with the exception of MENA, which is approximated by an auxiliary dataset (see Section “Modeling Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Race”). All colors except gray refer to cells with p < .001 (two-tailed computed using the Wilson score interval). We summarize median representation ratios in (aii, b). We focus on especially omitted groups in (c, d) with log-scale histograms of names by racial likelihood in the LM-generated texts. Exact Rrep ratios, p-values, confidence intervals, and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) are provided in Table S13a–d.

While the rank order aligns with the representation in the U.S. Census, proportional representation is not observed. Compared to the U.S. Census, median representation for racially minoritized characters (Fig. 1aii) ranges from ratios of 0.22 (MENA, Labor, v = 57247, p < 0.001, d = −1.337, 95% CI [0.198, 0.237]) to 0.66 (NH/PI, Labor, v = 57247, p < 0.001, d = −0.249, 95% CI [0.585, 0.800]), while White characters are over-represented at a median ratio of over 1.25 in Learning (v = 71870, p < 0.001, d = 1.04, 95% CI [1.238, 1.262]) to 1.34 in Labor (v = 57247, p < 0.001, d = 1.233, 95% CI [1.324, 1.351]). This means that for names reflecting any minoritized race, their representation is 33% (i.e., NH/PI, Labor) to 78% (i.e., MENA, Labor) less likely to appear in LM-generated stories, while White names are up to 34% more likely to appear relative to their representation in the U.S. Census. Meanwhile, gender representation is predominantly binary, skewing towards more feminized character representation, particularly for students in the Learning domain (except for ChatGPT 4, which skews masculinized).

Concerning gender, characters with non-binary pronouns are represented less than 0.5% of the time in all models except ChatGPT3.5 (3.9% in Learning). Binary gender representation ratios skew slightly feminine for all domains (Rrep = 1.07, v = 193370, p < 0.001, d = 0.023, 95% CI [1.058, 1.089]), whereas non-binary genders are underrepresented by an order of magnitude compared to Census levels (Rrep = 0.10, v = 193370, p < 0.001, d = −0.119, 95% CI [0.065, 0.148], see Fig. 1aii). Non-heterosexual romantic relationships are similarly underrepresented and are depicted in less than 3% of generated stories, with median representation ratios ranging from 0.04 (NB-NB, v = 35587, p < 0.001, d = −0.380, 95% CI [0.008, 0.241]) to 0.28 (F-F, v = 35587, p < 0.001, d = −0.181, 95% CI [0.214, 0.364], see Fig. 1b). Therefore, we find that all five generative LMs exacerbate patterns of omission for minoritized identity groups beyond population-level differences in race, gender, and sexual orientation (with p-values of <0.001 across nearly every combination of model and domain). That is, we observe far fewer mentions of these identity groups than we would expect given their representation in the population.

In Fig. 1c we illustrate additional patterns of omission specifically for NH/PI and AI/AN names, where we find little to no representation above a racial likelihood threshold of 24% (NH/PI) and 10% (AI/AN). Notably, this pattern of omission also holds for intersectional non-binary identities, where models broadly represent non-binary identified characters with predominantly White names (Fig. 1d). These baseline findings indicate that LMs broadly amplify the omission of minoritized groups in response to power-neutral prompts. The extent of this erasure exceeds expected values from the overall undercounting of minoritized groups in U.S. Census datasets67,68.

Patterns of Subordination

The representation of minoritized groups increases when power dynamics are added to the prompts, specifically with the introduction of a subordinate character. We find that race and gender-minoritized characters appear predominantly in portrayals where they are seeking help or are powerless. We quantify their relative frequency using the subordination ratio (see Eq. 3), which we define as the proportion of a demographic observed in the subordinate role compared to the dominant role. Figure 2a displays overall subordination ratios at the intersection of race and gender.

a Shows subordination ratios across all domains and models, increasing from left to right. Ratios for each model are indicated by different symbols plotted on a log scale (circles refer to ChatGPT3.5, squares refer to ChatGPT4, plus symbols refer to Claude2, x symbols refer to Llama2, and triangles refer to PaLM2). Center lines indicate the median across all five models. Redder colors represent greater degrees of statistical confidence (calculated as two-tailed p-values for the binomial ratio distribution, with p < .05 shown in yellow, p < .01 shown in orange, p < .001 shown in red, and p > .05 shown in gray), compared against the null hypothesis (subordination ratio = 1, dotted). b Shows the median subordination values across all five models by gender, race, and domain. Values above 1 indicate greater degrees of subordination, and values below 1 indicate greater degrees of dominance. Exact Rsub ratios, p-values, and confidence intervals are provided in Table S13e–m.

This approach allows us to focus on relative differences in the portrayal of characters when power-laden prompts are introduced. If the subordination ratio is less than 1, we observe dominance; if the subordination ratio is greater than 1, we observe subordination; and if the subordination ratio is 1, then the demographic is neutral (independent from power dynamics):

Overall, feminized characters are generally dominant in the Learning domain (i.e., subordination <1, meaning they are more likely to be portrayed as a “star student”). Notably, this relationship holds across all classroom subjects, including math, despite cultural stereotypes about math and gender (see Section “Textual Identity Proxies and Psychosocial Impacts”)69,70. This result is consistent with new trends in U.S. higher education in which women obtain undergraduate degrees at significantly higher rates than their male counterparts71. However, feminized characters hold largely subordinated positions in the Labor domain (i.e., subordination >1—see Fig. 2a, b). White feminized characters are uniformly dominant in stories across all five models in Learning (Rsub = 0.25, v = 139149, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.238, 0.262]), while White masculinized characters are uniformly dominant in Labor (Rsub = 0.69, v = 79754, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.667, 0.710]). For Love, most models portray White feminized characters as dominant (Rsub = 0.73, v = 141411, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.700, 0.752]), with the exception of PaLM 2 and ChatGPT 4. We observe that for any combination of domain and model, either a White feminized and/or White masculinized character is dominant (p < .001). The same universal access to power is not afforded to characters of other racialized and gendered identities. Non-binary intersections across all races tend to appear as more subordinated, however, due to their omission these results are non-significant (see Fig. 1d). Domain differences are also observed at the intersection of race and gender. For example, as shown in Fig. 2b, high degrees of subordination are observed for Asian women in Labor (Rsub = 3.75, v = 79754, p < 0.001, 95% CI [2.95, 4.78]) and, to a lesser extent, Love (Rsub = 2.18, v = 141411, p < 0.001, 95% CI [1.832, 2.594]), whereas they are dominant in Learning (Rsub = 0.45, v = 139149, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.367, 0.541]). Conversely, Asian men are highly subordinated in Learning (Rsub = 7.70, v = 139149, p < 0.001, 95% CI [5.416, 10.96]) and moderately subordinated in Love (Rsub = 1.46, v = 141411, p = 0.004, 95% CI [1.132, 1.872]), whereas their subordination ratio in Labor is ambiguous (Rsub = 0.86, v = 79754, p = 0.562, 95% CI [0.496, 1.453]). Overall, the models reinforce dominant portrayals of women in educational settings and men in workplace settings.

Examining names that are increasingly likely to be associated with one race (measured using fractionalized counting—see Eq. 1) reveals a more fine-grained pattern (see Fig. 3). With few exceptions (e.g., PaLM2 tends to repeat a single high-likelihood Black name, Amari, as a star student in Learning), the models respond to greater degrees of racialization with greater degrees of subordination for all races except White, as shown in Fig. 3a, b (LMs do not produce high-likelihood racialized names for NH/PI and AI/AN, as shown in Fig. 1c, hence these two categories are missing from Fig. 3).

a Shows subordination ratios, increasing from left to right per plot, of unique given names across all LMs, by race for which likelihoods vary (models do not generate high likelihood NH/PI or AI/AN names as shown in Fig. 1c). When a name has zero occurrences in either dominant or subordinated roles, we impute using Laplace smoothing. b Plots overall subordination across all models above a racial likelihood threshold as a percentage from 0 to 100. c Shows the median subordination ratio taken across all integer thresholds from 0 to 100, controlling for the effects of gender and categorized by domain, model, race, and gender (for non-binary characters, the models do not generate high likelihood racial names as shown in 1 d). Exact Rmrs ratios, p-values (two-tailed binomial ratio distribution), and confidence intervals are provided in Table S13n–p.

To quantify the extent to which subordination ratios vary across names for increasing degrees of racialization, we introduce the median racialized subordination ratio, which quantifies subordination across a range of possible racial thresholds. First, we control for possible confounding effects by conditioning on gender references (pronouns, titles, etc.). Then, for each intersection of race and gender, we compute the median of all subordination ratios for names above a variable likelihood threshold t as defined in Eq. 4. With sufficiently granular t, this statistic measures subordination while taking the spectrum of racial likelihoods into account. For our experiments, we set t ∈ [1, 2, …, 100].

Figure 3c shows intersectional median racialized subordination ratios by race and gender. We find large median subordination ratios for every binary gender intersection of Asian, Black, Latine, and MENA characters across nearly all models and domains (for non-binary characters, LMs do not produce a significant number of high-likelihood racialized names for any race except White). In 86.67% of cases (i.e., 104 of 120 table cells), characters from minoritized races appeared more frequently in a subordinated role compared to a dominant role. By contrast, in 3% of all cases (i.e., 1 of 30 table cells), White masculinized or feminized characters appeared more frequently in a subordinated role compared to a dominant role. In Learning, Latine masculinized students are portrayed by Claude 2.0 in the median as 1308.6 times more likely to be subordinated (i.e., a struggling student) than dominant (i.e., a star student, Rmrs = 1308.6, v = 15908, p < 0.001, 95% CI [184.31, 9290.3]). Across models and domains, Asian feminized characters are subordinated by several orders of magnitude (Rmrs = 172.6 for ChatGPT 4 in Learning, v = 11044, p < 0.001, 95% CI [23.644, 1260.2]; Rmrs = 352.2 for Claude 2.0 in Labor, v = 8604, p < 0.001, 95% CI [49.475, 2507.7]; and Rmrs = 160.6 for PaLM 2 in Labor, v = 7925, p < 0.001, 95% CI [22.544, 1144.5]). Black and MENA masculinized characters are subordinated to a similar degree by PaLM 2 (Rmrs = 83.8 for Black masculinized characters in Love, v = 10853, p < 0.001, 95% CI [11.438, 613.25]; Rmrs = 350.7 for MENA masculinized characters in Labor, v = 4588, p < 0.001, 95% CI [48.938, 2513.5]).

To further illustrate levels of subordination, we provide counts for the most common highly racialized names across LMs by race, gender, domain, and power condition (baseline is power-neutral; dominant and subordinated are power-laden) (Table 2). Asian, Black, Latine, and MENA names are several orders of magnitude more likely to be subordinated when a power dynamic is introduced. By contrast, White names are several orders of magnitude more likely to appear in baseline and dominant roles than non-White names. In the Learning domain, Sarah (83.1% White) and John (88.0% White) respectively appear 11,699 and 5915 times in the baseline condition and 10,925 and 5239 times, in the dominant condition. The next most common name, Maria (72.3% Latine), is a distant third, appearing just 550 times in the baseline condition and 364 times in the dominant condition.

Alternatively, when it comes to the subordinated roles, this dynamic is reversed. In Learning, Maria appears subordinated 13,580 times compared to 5939 for Sarah (a relative difference of 229%) and 3005 for John (a relative difference of 452%). Whereas Maria is significantly more likely to be portrayed as a struggling student than a star student, the opposite is true for Sarah and John. This reversal pattern of subordination extends to masculinized Latine, Black, MENA and Asian names. For example, in the Learning domain, Juan (86.9% Latine) and Jamal (73.4% Black) are 184.41 and 5.28 times more likely to appear subordinated than in dominant portrayals, respectively. The most commonly occurring masculinized Asian and MENA names (i.e., Hiroshi, 66.7% Asian, and Ahmed, 71.2% MENA) do not appear in either baseline or dominant positions for Learning despite appearing frequently in subordinated roles. Of the most frequently occurring racially minoritized names, only two appear more frequently in dominant than subordinated roles: Amari (86.4% Black, 1251 stories) and Priya (68.2% Asian, 52 stories). However, both of these appearances are generated exclusively by PaLM 2 in the Learning condition. Whereas PaLM 2 portrays other Black characters as subordinated across all domains, it represents Asian feminized characters as dominant in the Learning domain. This breaks from the pattern of the other four LMs that portray Asian characters as subordinated, reflecting variation among how LMs manifest model minority stereotypes. However, in Labor and Love, these exceptions disappear, and all of the most common minoritized characters are predominantly portrayed as subordinated. This pattern extends beyond the most common minoritized names (see Fig. 3a; we provide a larger sample of names in Tables S10 and S11(a–e)).

Patterns of Stereotyping

To analyze patterns of stereotyping, we turn to the linguistic content of the LM-generated narratives. We start by sampling stories (Table 3) with the most common racialized names (shown in Table 2). For the most omitted identity groups (LGBTQ+ and Indigenous; see Fig. 1c, d), we search for additional textual cues beyond names and gender references, including broad descriptors (e.g., Native American, transgender) and specific country/Native nation names and sexualities (e.g., Samoa, Muscogee, pansexual). We find representations of these terms to be low overall and entirely non-existent for most Native/Pacific Islander nations and sexualities. Sample stories in which these identity proxies do appear can be found in Table 4, and additionally in Table S12e–h. Qualitative coding identified frequently occurring linguistic patterns and stereotypes (see Section “Qualitative Coding for Explicit Stereotype Analysis”). Table 3a–d depicts representative stories for the most frequently occurring highly racialized names by identity group.

We find evidence of widespread cultural stereotyping across groups in addition to stereotypes that are group-specific. To some degree, these stereotypes provide a linguistic explanation for the high rates of subordination discussed in Section “Patterns of Subordination”.

The most frequent stereotype affecting MENA, Asian, and Latine characters is that of the perpetual foreigner72, which the LMs rhetorically employ to portray the subordination of these characters due to differences in culture, language, and/or disposition. Claude 2.0’s Maria is described as a student who just moved from Mexico, ChatGPT 4’s Ahmed is a foreign student from Cairo (in Egypt), and PaLM 2’s Priya is a new employee from India (Table 3a–c). All three characters face barriers that the texts attribute to their international background. Maria and Ahmed struggle with language barriers, and Priya has to learn how to “adjust to the American work culture”. Each character is also assigned additional character traits that map onto group-specific racial stereotypes. Maria is described using terms associated with a lack of intelligence and as someone who struggles to learn Spanish, despite it being her native language. This type of characterization reproduces negative stereotypes of Latina students as low-achieving (which is also reinforced strongly with masculinized Latine names, shown in Fig. 2b)73. Ahmed is described as “cantankerous”, aligning with negative stereotypes of MENA individuals as conflict-seeking74. Some ChatGPT 4 stories even depict Ahmed as requiring adjustments due to his upbringing in a war-torn nation (see Supplementary Method C, Tables 13a, d). Priya is described as grateful, which may be considered a positive sentiment in isolation, however, the absence of leadership qualities in any of her portrayals reifies model minority stereotypes of Asian women as obedient, demure, and good followers75. Priya is always a mentee, and despite being a quick learner, she nevertheless needs John’s help. While such portrayals may describe inequities in American society (such as systemic barriers that impede the career advancement of Asians/Asian Americans75), the stories produced by these models limit the responsibility for these inequities to the individual. By framing their struggles as deficits resulting from their foreignness or personality traits, these stories universally fail to account for larger structures and systems that produce gendered racism76,49.

In turn, LM stories center the white savior stereotype77, with dominant characters displaying positive traits in the process of helping minoritized individuals overcome challenges. For example, John (88.0% White), Charlie (31.3% White), and Sara (74.9% White) are depicted as successful, patient, hard-working, and charitable (Table 3a, d). For example, Jamal (73.4% Black) is introduced by Claude 2.0 as a jobless single father of three who is ultimately saved by Sara. Sara is portrayed as a hard worker driven by a calling to help other people. In that sense, Jamal is introduced to tell stories of Sara's good deeds, which include connecting Jamal with the food bank and finding ways to ensure his children are fed. There is no mention of attempts made by Jamal to help himself, let alone any reference to the historically entrenched systems that lead to the recurring separation of Black families in the U.S.78. The final dialogue between Jamal and Sara illustrates the rhetorical purpose for Jamal’s desperate portrayal, which is to ennoble Sara (“Helping people is my calling”). Jamal, meanwhile, appears in a power-dominant or power-neutral portrayal only twice despite filling a subordinated role 154 times. Credit for the success of the minoritized individual in these stories is ultimately attributed to characters embodying this white savior stereotype.

Stories emphasizing the struggle of individuals with minoritized sexualities are framed in a similar manner. Characters who are openly gay or transgender are most commonly cast in stories of displacement and homelessness due to coming out (Table 4a), while comparatively few stories depict gay or transgender individuals in stories that are affirming or mundane. Similar to Jamal’s depiction, the unnamed gay teenager is mentioned to elevate the main character, who is a diligent and compassionate social worker (Alicia, 47.0% White). The sexuality of the social worker is left unspecified, which illustrates the sociolinguistic concept of marking79. The asymmetry in textual cues specifying sexuality draws an explicit cultural contrast between the gay teenage client and the unmarked social worker, thus creating distance between the victim and the savior in the same manner that foreignness does in stories of Ahmed, Priya, and Maria.

Even in the more intimate scenarios, we observe imbalances that disproportionately subordinate LGBTQ+ characters. In Table 4b, Llama 2’s Alex (47.5% White) is a non-binary character who faces financial difficulties and must rely on their romantic partner Sarah (83.1% White) for support (in this story, Sarah is referred to using she/her pronouns). Whereas Sarah is a software engineer, Alex is “pursuing their passion for photography” and is “struggling to make ends meet”. Outputs like this play into cultural stereotypes that non-binary individuals are unfit for the professional world80. Across all 32 LM-generated stories of Alex as a non-binary character involving finances, Alex must rely on their partner for support. Furthermore, in every story except for one, their partner’s gender is binary (i.e., 96.9% of stories). For comparison, in cases where a heterosexual couple is presented, 9483 out of the 14,282 stories involving a financial imbalance place the masculinized character in a dominant position over the feminized character (i.e., 66.4% of stories). Therefore, non-binary identified characters in LGBTQ+ relationships are depicted by the models in a way that considerably amplifies comparable gender inequities faced by feminized characters in heterosexual relationships, above and beyond non-binary character omission in power-neutral settings (see Figs. 1a and 2b).

Multiple aforementioned stereotypes converge in stories describing Indigenous peoples. Table 4c introduces an unnamed Inuit elder from a remote village who is critically ill, living in harsh natural conditions. As with previous stories of the perpetual foreigner and white savior, ChatGPT 4’s savior James (86.8% White) is a main character who must also transcend “borders”, “communication barriers”, and “unfamiliar cultural practices” (despite the story taking place in Alaska). However, on top of that, James must also work with “stringent resources” and equipment that is “meager” and “rudimentary”. This positions the Inuit elder as a noble savage81, someone who is simultaneously uncivilized yet revered in a demeaning sense (mysteriously, the unnamed Inuit elder never speaks and only communicates his appreciation through a “grateful smile”). Twelve out of 13 occurrences of Inuit portrayals followed this sick patient archetype. Table 4d highlights another aspect of this stereotype, described as representations frozen in time82. Dale (90.5% White), the Native American character, is put in a position of power as somebody with authority to teach his best friend a “thrilling and unusual” hobby: making dreamcatchers. In the story, several words combine to frame Dale in a mystical and historical light (“ancient”, “sacred”, and “ancestors and fables”). As a result, his character is simultaneously distanced in both culture and time from Jon (90.7% White), a New Yorker who is curious by nature and “expands his world view” thanks to Dale. Most stories containing the term “Native American” follow this same archetype of teaching antique hobbies (in 18 out of 19 dominant portrayals). In the other common scenario, the term “Native American” is used only in the context of a historical topic to be studied in the classroom (in 68 out of 109 occurrences). The disproportionate frequency of such portrayals omits the realities that Indigenous peoples contend with in modern society, reproducing and furthering their long history of erasure from the lands that are now generally referred to as America.

Discussion

As history has shown, fictional depictions of human beings are more than passive interpretations of the real world83,84,85. Rather, they are active catalysts of cultural production that shape the construction of contemporary social reality, often impacting the freedoms and rights of minoritized communities globally86,87,88. Compared to human authors, language models produce stories that reflect social biases with greater scale, efficiency, and influence. We demonstrate that patterns of omission, subordination, and stereotyping are widespread across five well-utilized models. These patterns have the potential to affect consumers across races, genders, and sexual orientations. Crucially, they are present in LM outputs spanning educational contexts, workplace settings, and interpersonal relationships. Implicit bias and discrimination continue to be overlooked by model developers in favor of self-audits under the relatively new categories of AI safety and red-teaming, repurposing terms originating from fields such as computer security89,90. Such framings give greater attention to malicious users, national security concerns, or future existential risks at the expense of safeguarding fundamental human rights91,59. Despite lacking rigorous evidence, developers use terms like “Helpful, Harmless, Honest” or “Responsible” to market their LMs92,93. The generative AI-bias literature consistently finds that the leading LMs overwhelmingly reify socially dominant representations (i.e., white, heteronormative)32,36,43,44,45,94. We provide additional evidence that these models exacerbate racist and sexist ideologies for everyday consumers with scale and efficiency. In line with prior evidence, our findings underscore the extent to which generative AI models produce sexist and racist representations in text28,62,95, and vision models96,97,98, all of which further homogenize and essentialize marginalized identities99,100. The bias we identify is especially impactful as it does not require explicit prompting to reinforce the omission and subordination of minoritized groups. This in turn increases the risks of psychosocial and physical harms, even outside of conscious awareness42,101,102.

Results highlight widespread patterns of omission in the power-neutral condition, as well as high ratios of subordination and prevalent stereotyping in the power-laden condition. Combined, these outputs contribute to a lived experience where consumers with minoritized identities, if they are represented at all, experience character portrayals as struggling students (as opposed to star students), patients or defendants (as opposed to doctors or lawyers), and a friend or romantic partner who is more likely to borrow money or do the chores for someone else (as opposed to the other way around). Importantly, these omission levels exceed any level of bias that may be expected if language models were simply reflecting reality103. Minoritized characters are up to thousands of times more likely to be portrayed as subordinated and stereotyped than empowered (see Fig. 3c). As evidenced by the social psychology literature, omission, subordination, and stereotyping through racialized and gendered textual cues are shown to have direct consequences on consumer health and psychological well-being104. For example, exposure to linguistic cues that signal one-sided stereotypic associations (e.g., cantankerous Ahmed, or supportive Priya) can lead to unhealthy eating behaviors102 and reduced motivation to pursue career opportunities105. Observed patterns of subordination may be especially consequential when the magnitude and duration of stereotyping are proportional to the frequency of linguistic triggers101. As language models are being rapidly adopted in educational settings with goals such as personalized learning106, their potential to propagate cultural stereotypes further exacerbates pre-existing threats, especially if used in high-pressure contexts (e.g., testing and assessment)107. These stereotypes disproportionately target minoritized groups54,55 and may contribute to increased cognitive load, significantly impacting sense of belonging70, behavior108, self-perception, and even cognitive performance23,54,73. Even for individuals who do not inhabit minoritized identities, such stereotypes reinforce pre-existing prejudices56.

The prompts in our study correspond to scenarios where LMs are increasingly having unmediated interactions with vulnerable consumers, from AI-assisted writing for K-12 and university students3,9 to text-based bots for simulating romantic interactions10,11 or roleplaying as refugees seeking asylum109. By releasing these models as general-purpose interfaces, LM developers risk propagating Laissez-Faire harms to an untold number of susceptible secondary producers who build products using their models. This is particularly consequential for minoritized students, for whom language and identity are critical in the acquisition of academic knowledge110 as well as consumers in international contexts, who are not covered by the U.S.-centric focus of this initial study. A growing number of AI bias and fairness studies contend that to truly understand the broad impacts of AI-generated potential harms, future research should analyze prompts across diverse use-cases, including models reflecting varying cultural and linguistic contexts111,112,113 (e.g., BLOOM114). It remains to be seen if open-ended prompting leads these models to behave in similar ways. Our results call for researchers to adapt our open-ended prompting method to examine additional prompts in other languages, locales, and power contexts with consideration to additional identity factors (e.g., religion, class, disability). Such studies would benefit from the framework of intersectionality, replacing U.S.-centric identity categories with power structures specific to international contexts (e.g., using caste), and considering a broader set of use-cases, including representations of people in generative audio, image, or video.

Our findings are especially urgent given the limited set of regulatory human-rights protections in the U.S. context, underscoring the need for multiple reforms in generative AI policy. In 2022, under U.S. President Biden, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) released an AI Bill of Rights that documented the dangers of unchecked automated technologies and provided a blueprint for risk mitigation. Seven major companies—Amazon, Anthropic, Google, Inflection, Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI—voluntarily committed to upholding the principles of this Bill and ensuring that their products were scrutinized for potential harm. The blueprint is now maintained by the U.S. Archives115. A current examination of the priorities of the OSTP and the White House presents a different future for AI: one in which deregulation and expansion are the primary goals. The current U.S. Administration distributed America’s AI Action Plan in July 2025, which identifies more than 90 Federal policy actions to achieve the goals of the administration. Furthermore, the OSTP has explicitly revoked the Executive Order (EO) on AI from the Biden administration and has produced a new EO on preventing “woke AI” in the federal government. The EO, as well as the AI Action Plan, is focused on removing ideological biases from large language models. Our analyses demonstrate that there is indeed considerable ideological bias in contemporary large language models116. In regulating AI, we advocate for intersectional and sociotechnical approaches towards addressing the structural gaps that have enabled developers to sell recent language models as general-purpose tools to an unregulated number of consumer markets, while also remaining vague about (or refusing) to define the types of potential harms that are addressed in their self-audits. That is, effective regulation of language models must go beyond benchmarking117 to audit real-life consumer use cases89—including creative writing—while also grounding measures in a thoughtful consideration of potential human harms prior to their limited deployment in well-tested scenarios42. Second, our findings bolster calls for greater transparency from LM developers118, providing the public with details of the training datasets, model architectures, and labeling protocols used in the creation of generative LMs, given that each of these steps can contribute to the types of bias we observe in our experiments47,103. Third, we highlight the urgent need to expand public infrastructure to support third-party research capable of matching the rapid pace of model release as millions of AI models have proliferated the web, putting strain on traditional research and publishing pathways119. Stereotyping literature suggests that identity threats may be reduced by creating identity-safe environments through cues that signal belonging120. Critical AI education also raises awareness of the potential for language models to discriminate, helping to protect minoritized students by empowering them to respond in conducive ways121,122. Our study finds that publicly available LMs do not reflect reality; instead, they amplify biases by several orders of magnitude and reproduce discriminatory stereotypes reflecting dangerous ideologies concerning race, gender, and sexual orientation61. Given the disproportionate impacts on minoritized individuals and communities, we highlight the urgent need for critical and culturally relevant global AI education and literacy programs to inform, protect, and empower diverse consumers in the face of the Laissez-Faire harms they may encounter alongside the proliferation of generative AI tools123.

Limitations

This study also has limitations. Reliance on U.S. Census racial categories and prompts framed around the term American limits the generalizability of findings to international contexts. Laissez-faire harms tied to categories such as caste, religion, or class in non-U.S. societies remain beyond our study scope; however, studies of this type are encouraged in future research. While our study identifies major stereotypes by race (e.g., perpetual foreigner, white savior) and gender (e.g., glass ceiling), additional analyses are necessary for subtler or emergent stereotypes (e.g., those by nationality, socio-economic status, etc.)113. Likewise, our analysis focuses on five widely deployed, English-dominant LMs (ChatGPT3.5, ChatGPT4, Claude2.0, Llama2, PaLM2), excluding open-source multilingual models (e.g., BLOOM) and smaller-domain models, potentially overlooking biases in non-English or other domain-specific contexts.

Additionally, in the absence of self-reported data, the datasets we employ have several limitations. First, we note that countries of origin in the case of MENA and NH/PI identities can only approximate race in the absence of self-reported data. Second, methods of data creation and collection for both datasets themselves skew racial distribution, due to factors like voting restrictions and demographic bias of Wikipedia editors124. As we discuss in Section “Modeling Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Race”, Florida voter registration imperfectly approximates the demographic composition of the United States. Controlling for such local variations when quantifying name-race associations would necessitate a national-level dataset surveying a significant number of named individuals alongside racial and ethnic self-identification that also incorporates membership in Indigenous communities. To the best of our knowledge, no such dataset currently exists. These limitations remain a persistent issue within widely adopted data collection methods for race and/or ethnicity, including the U.S. Census (which in 2023 proposed adding MENA as a racial category alongside allowing open-ended self-identification of ethnicity). This operational shortcoming affects all publicly available research datasets combining U.S. racial categories with given name data125,126,127. We also note several limitations to our approach for modeling gender and sexual orientation. First, categorical mapping on word lists does not capture stories where people may choose gender pronouns from multiple categories (e.g., they/she) or neopronouns. Second, we are unable to effectively infer transgender identities, as such individuals may choose to adopt pronouns or references in any of the above categories despite maintaining a separate gender identity (furthermore, we observe no instances of the terms trans woman or trans man in any of the generated stories). Third, our approach does not account for sexual orientations that cannot be directly inferred from single snapshots of gender references. To better capture broadly omitted gender populations, we utilize search keywords to produce qualitative analyses (e.g., transgender) (see Supplementary Methods B section 7). That said, our choice of keywords is far from exhaustive and warrants continued research. To support such efforts, we open-source our collected data (see Supplementary Methods D).

Ethical and Societal Impact

In this study, we evaluate intersectional forms of bias in LM-generated text outputs. Given the nature of biases we find in all five LMs, we do not involve human subjects in our research, nor did we outsource data labeling and analysis beyond members of our authorship team. We released our dataset to allow for audit transparency and in the hopes of furthering responsible AI research. At 500,000 stories, the size of our dataset may also reduce barriers to entry for researchers with less funding (e.g., independent researchers). We must also highlight the possibility of adverse impacts. One concern with releasing this data is that reading a dataset of this nature may be both triggering and upsetting to readers and potentially pose the risk, if not properly contextualized, of subliminally reinforcing biased narratives of historically marginalized social groups to unsuspecting readers. Furthermore, some studies suggest that the act of warning that LMs may generate biased outputs may lead to increased anticipatory anxiety, while having mixed results on actually dissuading readers from engaging128. We hope that this risk will be outweighed by the benefits of informing susceptible consumers of possible subliminal harms.

A secondary group of adverse impacts includes discriminatory abuses of the datasets and methods we describe in our study for modeling race, gender, and sexual orientation. One recent abuse of automated models is illuminated by a 2020 civil lawsuit, National Coalition on Black Civic Participation v. Wohl129, which describes how a group of defendants used automated robocalls to target and attempt to intimidate tens of thousands of Black voters ahead of the November 2020 U.S. election. To mitigate the risks of our models being used in such a system, we do not release our trained models.

Finally, to preserve the privacy of real-world individuals whose data contributed to fractional race modeling, we do not publish racial probabilities in our dataset, as they may be used to reveal personally identifiable information for rare names in particular. For researchers seeking to reproduce our work, we note that these data may be accessed instead through a gated repository, similar to the one described above, by contacting the researchers whom we cite in our work (see Section “Data Availability”).

Methods

To answer our research question, we divided our methodological approach into three stages. First, we selected the language models and designed open-ended prompts that incorporated power dynamics to uncover underlying biases related to race, gender, and sexual orientation within each model. Second, we quantified biases of omission and subordination by calculating representation ratios based on the probabilistic distribution of race, gender, and sexual orientation identities, using LM-generated names and gendered references (including pronouns and titles). Third, we employed critical qualitative methods130 to analyze the most frequently occurring identity cues across intersectional subgroups and validated stereotype constructs using interrater reliability techniques.

Model Selection

We investigate 500,000 texts generated by the base models of five publicly available generative language models: ChatGPT 3.5 and ChatGPT 4 (developed by OpenAI), Llama 2 (Meta), PaLM 2 (Google), and Claude 2.0 (Anthropic). Model selection was based on both the sizable amount of funding wielded by these companies and their investors (on the order of tens of billions in USD131), as well as the prominent policy roles that each company has played on the federal level. In July of 2023, the U.S. White House secured voluntary commitments from each of these companies to ensure product safety before launching them publicly132. To some extent, our analysis tests the extent to which they met this policy imperative.

We query these LMs with 100 unique open-ended prompts pertaining to 50 everyday scenarios across three core dimensions of social life situated within the context of the United States. For each language model (LM), we gathered a total of 100,000 stories—1000 samples for each of the 100 unique prompts—using the default parameters configured for consumer access, over a period of twelve weeks.

Prompt Design

Several principles guided our prompt design. First, prompts were designed to reflect potential use cases across multiple domains, for example, an AI writing assistant for students in the classroom5,9 or screenwriters in entertainment12. An analysis of consumer interactions with ChatGPT ranked creative writing as the most frequent consumer use case (comprising 21% of all conversations), highlighting the relevance of our study scope65. Second, each prompt uses the colloquial identity term American, which is common parlance to refer to those residing in the United States (i.e., The American People), regardless of their socio-economic background (i.e., race, ethnicity, citizenship, employment status, etc.). Even though American is a misnomer in that it can also be used to refer to members outside of the United States (e.g., individuals living in Central or South American nations), as we show in the results, these models appear to interpret American to mean those in the United States, thus furthering U.S.-centric biases present in earlier technology platforms which privilege WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) norms and values133,134,135.

Utilizing the intersectional theoretical framework28,50, we examine how LMs generate outputs in response to prompts that depict everyday power dynamics and forms of routinized domination49. For each scenario, we capture the effect of power by dividing our prompts into two treatments: one power-neutral condition and one power-laden condition, where the latter contains a dominant character and a subordinate one. Therefore, our study conceptualizes social power specifically through prompts that ask LMs to generate stories in response to scenarios where dominant and subordinated characters interact with one another.

To obtain stories from a wide variety of contexts, our prompts span three primary domains of life in the US: Learning, Labor, and Love. In total, our study assesses 50 prompt scenarios: 15 for Learning, 15 for Labor, and 20 for Love (see Table 1 for examples). Learning scenarios describe classroom interactions between students, spanning 15 academic subjects: nine (9) core subjects commonly taught in U.S. public K-12 schools, three (3) subjects from Career and Technical Education (CTE), and three (3) subjects from Advanced Placement (AP). Labor scenarios describe workplace interactions and span 15 occupations categorized by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). For both domains, we base our selection of subjects and occupations to reflect a diversity of statistical representations by gender, class, and race, including subjects and occupations for which minoritized groups are statistically overrepresented in comparison to the 2022 U.S. Census68,136 (see Tables S1, S2). Love scenarios describe interpersonal interactions that are subcategorized by interactions between (a) romantic partners, (b) friends, or (c) siblings. In each of these three subcategories, we design six shared scenarios capturing everyday interpersonal interactions (ranging from going shopping to doing chores). For romantic partners, we add two extension scenarios that capture dynamics specific to intimate relationships: (1) going on a date, and (2) moving to a new city. We limit our scenarios to interpersonal interactions between two people in the interest of studying the effects of power (see Section “Textual Identity Proxies and Psychosocial Impacts”) and while these prompt scenarios do not reflect the full diversity of experiences that comprise interpersonal interactions, we believe this framework offers a beachhead for future studies to assess an even wider variety of culturally relevant prompts, both within the U.S. and beyond. For each LM, set to default parameters, we collect 100,000 outputs (or 1000 samples for each of the 100 unique prompts). We provide a complete list of prompt scenarios in Tables S3, S4, and S5. Data collection was conducted from August 16th to November 7th, 2023.

Textual Identity Proxies and Psychosocial Impacts

We analyze LM-generated outputs for bias using linguistic identity cues with the potential to induce potential psychosocial harms that disproportionately affect minoritized consumers. We specifically focus on textual identity proxies for race, gender, and sexual orientation in the context of stories, narratives, and portrayals of people. Established cognitive studies show how exposure to biased representations and stereotypic associations can shape how individuals view themselves, which in turn, shape their interactions with their environment in contexts where identities are salient104,137. For example, female undergraduates majoring in math, science, and/or engineering who viewed an advertisement video of professionals in their academic field were more likely to respond with cognitive and physiological vigilance and report a reduced sense of belonging and motivation when the video portrayed a gender imbalance, compared to when the video showed equal gender representations70. However, these effects did not extend to male undergraduates, irrespective of representation ratios. These video portrayals thus functioned as a situational cue with cognitive impacts depending on both the participant setting (i.e., academic environments) and the identity of the students (i.e., gender), given the prevalent American cultural stereotype that math is for boys69. Identity-based cues may be textual as well as visual. A study assessing the same stereotype on Asian-American female learners found that wording to selectively cue race or gender identity on a questionnaire administered prior to a test predicted performance based on whether a racial stereotype was activated (i.e., Asians are good at math) or whether a gender stereotype was activated (i.e., women are bad at math)24. Therefore, intersectional identity backgrounds must be taken into account when considering how identity portrayals may function as situational cues138. Furthermore, the impacts of narrative cues may be positive or negative depending on a variety of factors in addition to social identity, including the perceived risk of a situation and how the cue is framed104. Potential psychosocial harms faced by minoritized groups from negative stereotypic cues are broad and far-ranging, including negative impacts in behavior108, attitude23, performance24,54,73,139, and self-perception55 in addition to reinforcing the prejudiced perceptions of other identity groups56.

Settings that elicit identity-based cues do not require the reader to be consciously monitoring for stereotypes, and in some settings this may in fact magnify the effect101. This aligns with our study’s context, where race, gender, and sexual orientation are not explicitly requested (see Table 1). Following stereotyping studies that leverage linguistic identity cues23,24,102,105, we analyze LM-generated texts for race (using names) and gender proxies (using pronouns, titles, and gendered references). Table 5 shows the similarities between textual proxies in our study and words that have been demonstrated in psychology studies to prime stereotype threat by race and gender. This experimental design has additional precedence in sociotechnical studies that report discriminatory outcomes in hiring17,39 and targeted search advertisements40 in response to equivalent proxies.

To extract textual identity proxies at scale, we fine-tune a coreference resolution model (ChatGPT 3.5) using 150 hand-labeled examples to address underperformance in the pretrained LMs on underrepresented groups (e.g., non-binary)140. On an evaluation dataset of 4600 uniformly down-sampled LM-generated texts, our model performs at 98.0% gender precision, 98.1% name precision, 97.0% gender recall, and 99.3% name recall (.0063 95CI). Overall name coverage of our fractionalized counting datasets is 99.98%.

Modeling Gender, Sexual Orientation, And Race

In the context of studies of real-world individuals, the gold standard for assessing identity is through voluntary self-identification46,66,141. Given our context of studying fictional characters generated by LMs, our study instead measures observed identity46 via associations between identity categories and textual proxies. Out of the four gender labels collected by the U.S. Census Bureau68, our model quantifies three categories of gendering: feminized (F), masculinized (M), and non-binary (NB, which is listed in the Census as “None of these”). We are unable to quantify transgender as a gender category because our study examines gender references found in LM-generated text via pronouns, titles and gendered references, all of which may be used non-exclusively by transgender individuals and are thus insufficient for determining transgender identity in the absence of explicit identity prompting. We model sexual orientation similarly by examining pairwise gender references in the LM-generated responses to a subset of prompts specific to romantic relationships (Table 1). Based on our gender model, we are able to model six relationship pairs, implying various sexual orientations (NB-NB, NB-F, NB-M, F-F, M-M, F-M). As with gender, our list of quantifiable sexual orientations is limited to those that can be inferred through textual proxies alone. For example, we are not able to model bisexual identity in our study setting, where responses consist of a single relationship story (and bisexual relationships may span several of the pairs we model). Our models for gender and sexual orientation are thus non-exhaustive and do not capture the full spectrum of identities or relationships that may be implied in open-ended language use cases. We base our quantitative model on frequently observed gender references in LM-generated texts. For modeling gender associations in textual cues, we utilize the concept of word lists that have been used in both studies on algorithmic bias in language models and social psychology23,24. Previous works only consider binary genders34,142, yet we observe gender-neutral pronouns in language model outputs and extend prior word lists to capture non-binary genders. Noting the potential volatility of word lists in bias research143, we provide our complete list of gendered references with a mapping to broad gender categories in Table S6a. Out of the 500,000 stories we collect, we observe a handful of cases where gender and sexuality labels are explicitly specified in LM-generated text. Given their small sample, we analyze these qualitatively (see Section “Qualitative Coding for Explicit Stereotype Analysis”).

We model seven categories of racialization corresponding to the latest OMB-approved Census classifications66: American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NH/PI), Middle Eastern or North African (MENA), Hispanic or Latino (we adopt Latine as a gender-neutral label), Asian, African-American or Black, and White. For modeling racial associations in textual cues, we use fractional counting, which has been shown in related studies to avoid issues of bias and algorithmic undercounting that impact minoritized races when using categorical modeling141. Following this approach, a fractional racial likelihood is assigned to a name based on open-sourced datasets of individuals reporting self-identified race, via mortgage applications125 or voter registrations126. We model race using the given name as the majority (90.9%) of LM responses to our prompts refer to individuals using given names only. While given names do not correspond to racial categories in a mutually exclusive manner (for example, the name Joy may depict an individual of any race), they still carry a perceived racial signal, as proven by bias studies across multiple settings17,18,19,34,39,40. Specifically, we define racial likelihood as the proportion of individuals with a given name self-identifying as a particular race:

Modeling observed race at an aggregate level enables us to better capture occurrences where any given name may be chosen by individuals from a wide distribution of races, albeit at different statistical likelihoods for a given context or time frame. Therefore, the choice of dataset(s) influences the degree to which fractional counting can account for various factors that shape name distribution, such as trends in migration. We are unable to use the U.S. Census data directly, as it only releases surname information. Therefore, we base our fractional counting on two complementary datasets for which data on given names is present. The first dataset we leverage is open-sourced Florida Voter Registration Data from 2017 and 2022126, which contains names and self-identified race classifications for 27,420,716 people comprising 447,170 unique given names. Of the seven racial categories in the latest OMB-proposed Census66, the Florida Voter Registration Data contains five: White, Hispanic or Latino, Black, Asian Pacific Islander (API), and American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN). While any non-Census dataset is an approximation of racial categories (and even the Census itself approximates the general population), we find this dataset to be the most appropriate publicly available dataset out of all candidate datasets identified for which a large number of named individuals self-report racial identity125,126,127. First, it models a greater number and granularity of race/ethnicity categories compared other datasets. For example, Rosenman, Olivella, & Imai127 leverage voter registration data from six states but categorically omit AI/AN as a label by aggregating this racial category as Other. Second, we find that the degree of sampling bias introduced by the data collection process of voting is lower than the comparable sampling bias introduced by other dataset methods, such as mortgage applications125, which systematically underrepresent Black and Latine individuals. Of the candidate datasets we evaluated, Florida voter registration data126 most closely approximates the racial composition of the US Census, deviating by no more than 4.57% for all racial groups (with the largest gap due to representing White individuals at 63.87% compared to 2021 Census levels of 59.30%). By contrast, mortgage application data125 overcounts White individuals with a representation of 82.33% (deviation of +23.03%) while undercounting Black individuals with a representation of 4.20% (deviation of −9.32%).

Nevertheless, using approximations to the US Census in the absence of country-wide given name identification introduces limitations. In particular, Florida is one of many states with a large elderly population, which influences the distribution of names according to generational trends. Historical patterns of migration, warfare, and settlement also shape the distribution of named individuals within demographic subgroups, restricting the degree to which any state’s geography may substitute as a fully representative sample of national name-race trends. One illustrative example is Florida’s Seminole community (originating from yat’siminoli, or free people), an Indigenous nation that has maintained their sovereignty in the Florida Everglades86. Similar heterogeneity shapes Florida’s Latine demographic due to geopolitical events such as the 1980 protests at the Peruvian embassy in Cuba and the ensuing governmental response that eventually drove hundreds of thousands of Cuban people to Florida144.

In general, no racial group is a monolith, and broad race categorizations can obscure the identities of meaningful sub-groups46,47. The history of race as a social construct reveals its multidimensional and overlapping nature with other social constructs such as religion, class87, kinship83, and national identity84. For example, the exclusion of country-of-origin identities (i.e., Chinese, Indian, Nigerian) and the omission (via aggregation) of individuals identifying as MENA or NH/PI into the White or Asian/ Pacific Islander categories, respectively, masks their marginalization within these categories. These limitations remain a persistent issue within widely adopted data collection methods for race and/or ethnicity, including the U.S. Census (which, in 2023, proposed adding MENA as a race in addition to allowing open-ended self-identification of ethnicity). To the best of our knowledge, this operational shortcoming affects all publicly available research datasets containing a large number of individuals that self-classify U.S. racial categories with given name data125,126,127. Furthermore, we recognize that quantitative and computational methods can be emancipatory145 and used to foster collective solidarity, reclaim forgotten histories and hold power to account26.

To address the problem of categorical omission, we leverage an additional data source to approximate the racial likelihood of names for MENA and NH/PI populations. We build on the approach developed by Le, Himmelstein, Hippen, Gazzara, & Greene146 that uses data of named individuals on Wikipedia to analyze disparities in academic honorees by country of origin. Our approach leverages OMB’s proposed hierarchical race and ethnicity classifications to approximate race for the two missing categories by mapping existing country lists for both racial groups to Wikipedia’s country taxonomy. For MENA, we build upon OMB’s country list66 based on a study of MENA-identifying community members147. For NH/PI, we leverage public health guides for Asian American individuals intended for disaggregating Pacific Islanders from API148. The full list of countries we use is provided in Table S6b. Due to the demographic bias of Wikipedia editors124, Wikipedia is likely to over-represent Anglicized names and under-represent MENA and NH/PI names. Therefore, we would expect the names extracted from these two racial categories in the aggregate to show results in our study that are more similar to the treatment of White names as opposed to other minoritized races. However, our study shows the opposite to be true (see Sections “Limitations” and “Ethical and Societal Impact”). We find that language models generate text outputs that under-represent names approximated from MENA and NH/PI countries in power-neutral portrayals, and subordinate these names when power dynamics are introduced, similar to other minoritized races, genders, and sexual orientations. For full technical details and replication, see Supplementary Methods B, Tables S7–S9.

Qualitative Coding for Explicit Stereotype Analysis

Our quantitative approach in Section “Modeling Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Race” models the associations between textual identity cues and social portrayals at the aggregate level, which assesses implicit stereotypes in settings where consumers may be primed via repeated engagement with LMs. This exemplifies what other scholars describe as distributional harms149. By contrast, instance harms consist of a single LM output that is damaging on its own, such as a single story that contains one or more explicit stereotypes that perpetuate wrongful, overgeneralized beliefs about demographic groups64. Modeling instance harms requires going deeper than statistical analyses of gender references and names. To model explicit stereotypes, we follow the critical mixed methods approach proposed by Lukito & Pruden130. The first step identifies stereotypes via open-ended reading on a representative subset of the LM-generated texts sampled from the most frequently occurring identity cues for each intersectional demographic group. Second, we operationalize stereotypes from open-ended reading (e.g., white savior, perpetual foreigner, and noble savage) to construct a codebook using definitions grounded in relevant social sciences literature72,77,81. Next, we iteratively codified stereotypes across multiple authors who served as raters to validate our constructs. Finally, based on the coding process, we create clusters of stories organized around non-exclusive combinations of stereotypes, choosing representative stories to highlight stereotypes by sampling from the largest cluster within each identity category, as shown in Section “Patterns of Stereotyping” (see Supplementary Methods B section 7 for more details on qualitative procedure, definitions, codebook construction and interrater reliability).

Statistical Methods

We calculate two-tailed p-values for all statistics defined in the paper. These statistics consist of ratios that either compare one demographic distribution against a fixed distribution (e.g., representation ratios) or ratios that compare two demographic distributions against each other (e.g., subordination ratios). We parametrize the former as a binomial distribution, as the comparison distributions may be considered as non-parametric constants for which underlying counts are not available (e.g., Census-reported figures, see Eq. 1 and Extended Technical Details in the Supplementary Methods). We calculate two-tailed p-values for these using the Wilson score interval, which is shown to perform better than the normal approximation for skewed observations approaching zero or one by allowing for asymmetric intervals150. This is well-suited for our data, where we observe a long-tail of probabilities (see Section “Patterns of Omission” for examples). While the Wilson score interval does not require normality, it assumes datasets with multiple independent samples and also assumes that all values lie in the interval [0, 1], which we confirm in our dataset.

We parametrize ratios between two statistics (see Eqs. 3 and 4) using binomial ratio distributions. First, we take the log-transform for both ratios, which may then be approximated by the normal distribution as shown by Katz in obtaining confidence intervals for risk ratios151. Following this procedure, we compute two-tailed p-values by calculating the standard error directly on the log-transformed confidence intervals152. Crucially, the log-transform does not require normality in the numerator or denominator of the ratios. Similar to the Wilson score intervals, the distributions must fit a binomial distribution with independent samples lying in the interval [0, 1], as confirmed in our data.

For ratios that compare one demographic distribution against a fixed proportion (i.e., representation ratios), we also report Cohen’s d as the effect size statistic to account for the potential impacts of standard deviation in the demographic distribution. For ratios that compare two demographic distributions against each other, we note that the reported statistic (i.e., subordination ratios) is equivalent to the odds ratio as an appropriate measure of effect size. All inferential statistics reported in the main article include degrees of freedom v, p-value, 95% confidence interval, and the corresponding effect size statistic.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability