Abstract

Extreme temperature events are becoming widespread with global warming, impacting phytoplankton, the foundation of the marine ecosystem. In the Southern Ocean, these impacts are not well understood, despite the key role of phytoplankton in global carbon cycling and climate. Here, we use 26 years of satellite observations and confirm previously identified impacts of marine heatwaves (MHWs) on phytoplankton in the Southern Ocean, while systematically comparing the opposite impacts of marine cold spells (MCSs). MHWs decrease phytoplankton chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) in subtropical regions (−21.11%) but less so in polar regions, with Chl-a even increasing in the Sub-Antarctic Zone ( + 22.26%). MCSs exhibit opposite patterns, enhancing Chl-a in subtropical regions ( + 32.37%) while inhibiting it in southern regions (−21.19%). These regional differences in Chl-a anomalies are mediated by distinct responses in phytoplankton size composition to MHWs and MCSs. As extreme events intensify with global warming, Southern Ocean’s phytoplankton will be disrupted, with implications for global biogeochemical cycles. These findings highlight the importance of simultaneously considering both MHWs and MCSs when assessing the ecological impacts of climate extremes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marine heatwaves (MHWs) and marine cold spells (MCSs) are extreme events characterized by prolonged periods of anomalously warm or cold ocean temperatures1,2,3. In recent decades, the frequency, duration, and intensity of MHWs have increased significantly across most global oceans1,2,3, while MCSs have exhibited the opposite trend globally4. MHWs are particularly pronounced in the Southern Ocean, which has absorbed the majority of anthropogenic heat uptake and experienced rapid warming5,6,7, while MCSs show more complex trends with possible duration increases in the Antarctic Zone8. The increasing incidence of MHWs in the Southern Ocean9 has resulted in severe ecological consequences, such as sharp reductions in surface chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) concentration10, heightened mortality among birds and marine life11. Concurrently, the intensified temperature variability in the Southern Ocean has also led to more frequent MCSs8, which may have profound ecological impacts.

Given its role as a major global carbon sink12,13 and a key driver of global climate and biogeochemical cycles14,15, understanding the Southern Ocean’s responses to these extreme events is of paramount importance. Phytoplankton, which form the base of marine food webs and mediate key biogeochemical processes like carbon fixation16, are particularly relevant in this context. They contribute significantly to oceanic carbon sequestration through the biological pump17,18, and serve as indicators of climate change impacts on marine ecosystems due to their sensitivity to environmental changes19,20. Although numerous studies have examined the long-term responses of phytoplankton in the Southern Ocean to gradual warming19,20,21,22,23,24, the impact of discrete, short-term extreme events like MHWs and MCSs remains poorly understood. The Southern Ocean’s strong meridional gradients in temperature, nutrient availability, and phytoplankton community structure25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 suggest that responses of phytoplankton to these extreme events may vary substantially across different regions. However, a comprehensive assessment of these responses is lacking. Moreover, responses of phytoplankton size structure, a key determinant of ecological and biogeochemical funtions26, to MHWs and MCSs, remain unexplored.

Here, we address these gaps by conducting an integrated assessment of phytoplankton responses to MHWs and MCSs across the entire Southern Ocean. Utilizing satellite-derived sea surface temperature (SST) and Chl-a concentration data from 1998 to 2023, coupled with advanced phytoplankton size class (PSC) models, we contrasted the response of phytoplankton in three distinct subregions: the subtropical Zone (STZ), Sub-Antarctic Zone (SAZ), and Permanently Open Ocean Zone (POOZ). Our results revealed striking regional disparities in the response of phytoplankton to extreme events. We found that MHWs in the POOZ can stimulate phytoplankton growth and potentially enhance carbon export – a stark contrast to the negative impacts observed in other regions. These regional differences are further mediated by the responses of different PSCs, which have significant implications for biogeochemical cycles. Our results highlight the need to account for regional and ecological complexities when assessing the effects of a changing climate on marine ecosystems.

Results

Spatiotemporal patterns of MHWs and MCSs

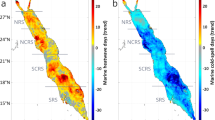

We used European Space Agency (ESA) satellite-derived SST data to detect MHWs and MCSs in the Southern Ocean. MHWs/MCSs were defined as periods when SST exceeded/fell below the 90%/10% percentile of the climatological baseline (1991–2020) for at least five consecutive days. Our analysis revealed distinct spatiotemporal patterns in the frequency, duration, and intensity of MHWs and MCSs across the Southern Ocean. MHWs were most frequent and prolonged in the STZ and SAZ, particularly in the Tasman Sea, southeastern Australia, and the Indian Ocean sector of the Southern Ocean southwest of Australia, where the annual average frequency exceeded 3.5 times, and the duration surpassed 60 days (Fig. 1a, b). In contrast, MHW intensity showed less spatial variability, with hotspots in the southwestern South Atlantic and around South America (Fig. 2a), possibly linked to mesoscale eddy activities within the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC)9. MCSs displayed a unique spatial distribution with higher frequencies in the POOZ (Fig. 1c), reflecting the accelerated warming in the northern Southern Ocean and cooling in the southern regions. This regional contrast was particularly pronounced in the duration of MCSs, with the POOZ experiencing an annual average of >60 days, compared to <20 days in the STZ and SAZ (Fig. 1d). The intensity patterns of MCS aligned closely with those of MHWs (Fig. 2b).

a, b Annual average frequency and days of MHWs. c, d Corresponding metrics for MCSs. Time series of the percentage of area affected by MHW (e) and MCS (g) in each subregion: the subtropical Zone (STZ, orange), Sub-Antarctic Zone (SAZ, purple), and Permanently Open Ocean Zone (POOZ, green). Spatially averaged days of MHW (f) and MCS (h) for each zone. Dashed lines indicate trends estimated using Sen’s slope, with significance assessed by the Mann–Kendall test. The subtropical front (STF) and polar front (PF) are indicated by the outer and inner black lines, respectively.

Seasonal variations were evident in the occurrence of MHWs and MCSs (Supplementary Fig. 1). MHWs peak in the austral summer and autumn in the STZ and SAZ, whereas MCSs were predominant in winter and spring in the POOZ (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Over the past four decades, the area fraction of the STZ affected by MHWs and that of the SAZ have increased significantly (+9.04% decade−1, p < 0.05; +3.64% decade−1, p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 1e, f). The area fraction affected by MCSs in the STZ and SAZ has decreased (−9.60% decade−1, p < 0.05; −2.20% decade−1, p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 1g, h). However, the area fraction of the POOZ affected by MCSs has increased (+2.9% decade−1, p < 0.05), with the area of increase exceeding that of the MHW decrease (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Phytoplankton responses to MHW and MCS

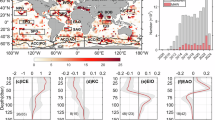

The response of phytoplankton to MHWs and MCSs was quantified by the percentage change from the mean Chl-a anomaly (climatological mean), and showed significant regional differences (Fig. 2c, d). Chl-a anomalies in the subtropical region are predominantly negative during MHWs (Fig. 2c), with only 5.89% of area showing positive anomalies, whereas in the SAZ and POOZ, positive anomalies are observed in 54.64% and 52.11% of the area, respectively (Fig. 2e). In contrast, only 7.41% of area in the subtropical region shows negative anomalies during MCSs, whereas the area with negative anomalies increases to 65.67% and 57.21% in the SAZ and POOZ, respectively (Fig. 2e). The spatial differences in phytoplankton response to extreme events appear to be delineated by the subtropical front (Fig. 2c, d).

To investigate phytoplankton responses under extreme temperature events of varying severity, we applied the Hobday et al.34 classification framework at each grid cell, categorizing MHWs and MCSs into four intensity levels (Supplementary Fig. 3). This classification is based on the ratio between the SST anomaly above the climatological 90th percentile and the difference between the climatological 90th percentile and the baseline climatology. In general, the intensity of extreme events increases progressively, with the occurrence probability of Category III and IV events being relatively low (Supplementary Fig. 3a–h). Despite varying intensities, the spatial distribution of phytoplankton responses remains broadly similar, and the percentage of Chl-a anomalies increases with event intensity (Supplementary Fig. 3i–p).

The temporal evolution of phytoplankton Chl-a anomalies during MHWs and MCSs reveals distinct patterns across regions (Supplementary Fig. 4). Phytoplankton anomalies began to emerge approximately 10 days before the onset of MHWs, with weak positive anomalies in the SAZ and POOZ, potentially reflecting high sensitivity to warming in this region (Supplementary Fig. 4i, m). As MHWs intensified, negative anomalies in the STZ amplified, while positive anomalies enhanced in the SAZ and POOZ (Supplementary Fig. 4j, n). During the decay phase of MHWs, positive anomalies weakened, while negative anomalies persisted (Supplementary Fig. 4k, o), suggesting asymmetry in response to warming and cooling phases. MCSs induced nearly opposite patterns, with positive anomalies in the STZ and negative anomalies in the SAZ and POOZ intensifying with MCS strength (Supplementary Fig. 4m–p). The temporal evolution mirrored that of MHWs, with anomalies emerging prior to MCS onset and persisting post-decay (Supplementary Fig. 5). Notably, the magnitude of positive anomalies often exceeded that of negative anomalies and persisted longer after extreme events. This suggests that the processes driving positive phytoplankton responses, particularly in the SAZ and POOZ, may have more prolonged effects than those driving negative responses. We further examined phytoplankton carbon and physiological responses to MHWs and MCSs (Supplementary Text 1), providing additional context for the observed patterns.

Distinct responses across PSCs

Underlying these regional patterns were significant differences in responses of PSCs to MHWs and MCSs. During MHWs, PSCs in the STZ exhibited relatively uniform responses, with negative anomalies occurring across 93.01−95.06% of the area (Fig. 3a–c). In contrast, in the SAZ and POOZ, picoplankton showed widespread positive anomalies, covering 79.1% of the area, whereas nanoplankton and microplankton were positively affected in only 48.5% and 51.1% of the area, respectively (Fig. 3a–c). This positive impact of picoplankton likely reflects their high temperature sensitivity and low nutrient requirements20,26. Total and size-fractionated phytoplankton Chl-a concentration show a strong positive correlation with increasing MHW intensity in the STZ and SAZ (Supplementary Fig. 6). Statistical analysis of the proportion of each PSC to total Chl-a in response to MHWs reveals that the proportion of small-sized phytoplankton increases significantly, while the proportion of medium- and large-sized phytoplankton decreases markedly during MHW events (Fig. 3g–i). This shift in size structure demonstrates high spatial consistency (Supplementary Fig. 7). Notably, during individual MHW events, changes in phytoplankton community composition can be highly pronounced, with the proportion of picoplankton increasing by up to 56.39% (Supplementary Fig. 8). Although variations in phytoplankton community composition may fluctuate in both positive and negative directions during individual events, statistical analysis of multiple events indicates that extreme warming events drive the phytoplankton community structure toward a dominance of smaller-sized populations, with a positive correlation with MHW intensity (R2 = 0.41, p < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 9).

Chl-a anomalies for picoplankton (a), nanoplankton (b), and microplankton (c) during MHWs. d–f Corresponding Chl-a anomalies during MCSs. g–i Box plots of phytoplankton community fractions in the subtropical Zone (STZ), Sub-Antarctic Zone (SAZ), and Permanently Open Ocean Zone (POOZ) during MHWs and MCSs, respectively. Box-plot elements are defined as follows: the center line represents the median; the box limits indicate the upper and lower quartiles; and the whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range.

During MCSs, PSCs exhibited positive anomalies across 83.7–94.1% of the STZ area (Fig. 3e, f). In the SAZ and POOZ, positive anomalies of picoplankton were observed over 86.2% of the area, whereas nano- and microplankton were positively affected in only 58.9% and 58.5% of the regions, respectively (Fig. 3e, f). With increasing MCS intensity, total and size-fractionated phytoplankton Chl-a concentration is significantly enhanced (Supplementary Fig. 6). In the STZ, Chl-a anomalies exhibit a strong correlation with MCS intensity, with the spatiotemporal mean anomaly of microplankton concentration reaching up to 165.3% (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting that extreme cooling events may have a more pronounced effect on phytoplankton communities than MHWs. Moreover, the response of phytoplankton size structure to MCS events is characterized by a significant increase in the proportion of total Chl-a by large-sized phytoplankton (Fig. 3g–i). During individual MCS events, the proportion of total Chl-a by microplankton can increase by up to 71.47% (Supplementary Fig. 10). These findings indicate that extreme cooling events shift the phytoplankton community toward a dominance of larger-sized populations.

Mechanisms underpinning regional differences in phytoplankton responses

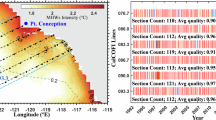

The distinct regional differences in phytoplankton responses to MHWs and MCSs across the Southern Ocean arise from varying phytoplankton division rates, which are modulated by temperature-light-nutrient dynamics, and loss rates that are regulated through ecological mechanisms35. In the subtropical zone, where phytoplankton growth is primarily limited by nitrate availability36 (Fig. 4), MHW-induced stratification exacerbates this limitation by reducing phytoplankton division rates and increasing loss rates through heightened grazing pressure from zooplankton concentrated in the shallower mixed layer, ultimately causing negative Chl-a anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 4e–h). Enhanced mixed-layer irradiance also promotes photoacclimation, shifting the carbon to Chl-a ratio (Supplementary Fig. 11c). Conversely, the SAZ represents the largest high-nutrient, low-chlorophyll (HNLC) region globally and exhibits phytoplankton division rates that are fundamentally constrained by iron availability despite nitrate sufficiency37.

a Annual average surface NO3 concentrations (PISCES, 1998–2023 climatology), b MLD averaged irradiance (calculation method in “Methods” section, 1998–2023 climatology). Mean anomaly percentages of MLD averaged irradiance during MHWs (c) and MCSs (d). The subtropical front (STF) and polar front (PF) are indicated by the outer and inner black lines, respectively.

During MHWs, increased stratification and shallower mixed layers38 enhance light availability for phytoplankton39. While direct evidence linking MHWs to iron limitation mitigation in the SAZ is lacking, their effects vary depending on regional contexts. For example, in areas with relatively adequate iron conditions – such as regions around the Antarctic Circumpolar Current characterized by upwelling40 and areas experiencing increased storm activity due to climate change, which may increase the delivery of iron-rich dust41– MHWs may synergistically enhance phytoplankton growth36,42. In the POOZ, which lies between the polar front and the northern limit of winter sea ice (Fig. 1), phytoplankton is seasonally co-limited by the micronutrient iron and light due to deep mixing and large solar zenith angles36,43. MHWs have a dual effect here: they enhance water column stability44, alleviating light limitation38,43, and accelerate ice melt45, relieving iron limitation46,47,48,49. These combined effects drive the strong positive Chl-a concentration anomalies observed during MHWs.

In contrast, MCSs induce opposite effects. On a global scale, MCSs induced an average increase of 4.25 ± 0.92 m in MLD, corresponding to an 8.13% enhancement50. The SAZ region features a winter deep mixing band (DMB) adjacent to the Antarctic Circumpolar Current’s (ACC) northern boundary51,52 and exhibits high winter mixed-layer resource availability53. Notable increases in MLD of approximately 20–30 meters were observed specifically in the Atlantic and Pacific sectors. This MCS-induced MLD deepening during winter enhanced vertical mixing, subsequently augmenting nutrient supply to the upper layer and alleviating nitrate limitation in SAZ regions. The increased nutrient supply elevated phytoplankton division rates, especially for fast-growing diatoms, while the deeper mixed layer may have contributed to reduced loss rates, potentially through greater population dilution and decreased grazing pressure54,55. Ultimately, the dominance of division rates over loss rates resulted in higher Chl-a concentrations and positive anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 5e–h). However, in the SAZ and POOZ, despite abundant nitrate availability, phytoplankton growth is primarily limited by iron availability; thus, additional input of nitrate alone would not promote phytoplankton growth. Instead, in the light-limited POOZ, the intensified mixing caused by MCS reduces light exposure for phytoplankton. MCSs promote sea-ice formation, and the process of seawater freezing absorbs dissolved iron46,47,48, exacerbating iron limitation and further suppressing phytoplankton growth.

The response mechanisms of phytoplankton of different size classes to environmental changes are generally consistent with the overall trend of total Chl-a concentration. However, larger phytoplankton exhibit more pronounced responses during extreme temperature events (Fig. 3c, f). Studies have shown that temperature and nutrient variations have a particularly significant impact on larger cells56. In general, nutrient availability is considered an important factor controlling the size structure of phytoplankton56. During MHWs, the sharp decline in nutrient supply significantly suppresses the growth of medium- and large-sized phytoplankton, while smaller phytoplankton gain a competitive advantage due to their lower nutrient requirements57,58, leading to a shift in community structure toward smaller sizes. Additionally, some Antarctic diatoms, such as Fragilariopsis cylindrus59, exhibit reduced cell size under high temperatures, which helps lower cellular iron quotas, increase the surface area-to-volume ratio, and enhance nutrient uptake and growth59. In contrast, during MCSs, nutrient replenishment reverses the advantage of larger phytoplankton, particularly in nutrient-poor subtropical zones (STZ), where the competitive advantage of smaller phytoplankton is diminished.

Implications for understanding phytoplankton responses to climate extremes

Recent research has primarily focused on the effects of extremely high temperatures on phytoplankton38,43,57,58,60,61,62. This study complements these efforts by examining phytoplankton responses during extreme low temperatures. We found that phytoplankton responses to extreme low temperatures can be more severe than to extreme high temperatures. This investigation explores the response of different PSCs to extreme temperature events and proposes underlying response mechanisms. Our results reveal that phytoplankton Chl-a concentrations exhibit symmetrical responses in terms of anomaly magnitude during extreme high and low temperatures, consistent with proposed response mechanisms based on light, temperature, and nutrients. However, changes in PSCs during MHWs and MCSs appear less regular, and their mechanisms are more complex, potentially related to nutrient levels, zooplankton predation, phytoplankton sedimentation, among other factors56,63,64. These findings align with recent work reporting significant differences in PSCs during MHWs driven by varying factors57. For example, atmospheric forcing-driven MHWs tend to shift PSCs towards larger species, while ocean process-driven MHWs lead to irregular size distributions. These observations suggest that the dynamics shaping phytoplankton size structure during extreme temperatures are more intricate than those affecting overall Chl-a levels.

It is also important to recognize that the choice of MHW definition can substantially influence event detection and severity, as well as whether long-term climate trends or short-term anomalies are emphasized65. We adopted the Hobday et al.3 framework because it is widely standardized and facilitates cross-study comparability, but acknowledge that alternative baselines or regionally tailored definitions could yield different insights. Future research should aim to elucidate the mechanisms underpinning these regional and size-dependent responses and quantify their implications for carbon cycling and ecosystem functioning. Incorporating extreme temperature events into biogeochemical and ecosystem models will greatly improve our ability to project the future of the Southern Ocean under climate change. As global ocean stratification intensifies, leading to reduced surface nitrate concentrations predicted by CMIP5 and CMIP6 models66,67, understanding how extreme events interact with these background nutrient trends is crucial. MHWs are predicted to intensify and occur more frequently in the northern region of the Southern Ocean1,44,68. Both MHWs and MCSs are projected to intensify in the POOZ (Fig. 1f, h), and the response of phytoplankton to these extreme events may shift from a previously positive or neutral effect to a predominantly negative one. This transition is likely to further suppress primary productivity and biological carbon export in the Southern Ocean, thereby exerting significant adverse impacts on the ocean’s capacity to regulate global climate change. Additionally, while our study focused on surface Chl-a and PSC changes, it is essential to investigate how these responses extend vertically through the water column, as vertical distribution patterns significantly impact ecosystem dynamics and biogeochemical cycles69.

Our study systematically assesses the complex and unexpected impacts of MCSs on Southern Ocean phytoplankton, highlighting the need for a regionally and ecologically nuanced perspective when evaluating the effects of climate extremes. As extreme events like MHWs and MCSs are becoming more widespread with global warming, their influence on the Southern Ocean’s role in global climate and biogeochemical cycles is likely to intensify. Unraveling this complexity will be critical for predicting the future of this vital ecosystem in a rapidly changing climate.

Methods

ESA CCI sea surface temperature and sea-ice concentration

The European Space Agency (ESA) Climate Change Initiative (CCI) SST version 3.0 is a daily sea surface temperature (SST) product with a 0.05° resolution70, spanning from 1981 to the present. CCI SST provides the mean SST at a depth of 0.2 meters, closely aligning with the nominal depth of drifting buoy measurements. It includes both the AVHRR and Along-Track Scanning Radiometer (ATSR) series, with satellite observation biases adjusted by recalibrating radiances using a reference channel to ensure a stable product. CCI applies a variational assimilation scheme to generate a gap-filled estimate of daily-mean SST. CCI v3.0 data can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5285/4a9654136a7148e39b7feb56f8bb02d2. We extracted SST and sea-ice concentration (SIC) data for a subset region centered on Antarctica, down to 30°S, from 1982 to 2023. For the purpose of comparing MHWs and MCSs with other variables, we re-gridded the 0.05° CCI SST data to a 0.25° resolution using bilinear interpolation.

Refined satellite observations of Chl-a

Daily satellite remote sensing reflectance data with a 4 km spatial resolution was extracted from the ESA Ocean Colour Climate Change Initiative (OC-CCI) v6.0 product71 for 1998–2023. CCI v6.0 uses data from ESA’s MERIS (Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer) sensor, NASA’s SeaWiFS (Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor) and MODIS-AQUA (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer-Aqua) sensors, as well as NOAA’s VIIRS (Visible and Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite). This time series now spans from late 1997 to the present, with the chosen algorithms optimized to meet climate user requirements. Remote sensing reflectance data from MODIS-Aqua, MERIS, and VIIRS were spectrally shifted to match SeaWiFS bands, and overlapping data were used to correct mean deviations between sensors at each pixel (https://rsg.pml.ac.uk/thredds/catalog-cci.html). For Chl-a calculations, we applied the OC4v6 algorithm72, which was developed for SeaWiFS and modified for the Southern Ocean to address the underestimation of chlorophyll levels by conventional algorithms in this region. We validated the algorithm using an in situ observational dataset. (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13).

Phytoplankton carbon and θ

Phytoplankton carbon was estimated using the backscattering coefficient73 at 443 nm (bbp(443)), with bbp(443) data obtained from OC-CCI, covering the period from 1998 to 2023. θ is defined as the ratio of phytoplankton carbon to Chl-a.

BGC-Argo data

In situ chlorophyll-a data were collected by profiling floats, primarily deployed under the Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modeling (SOCCOM) project, which is part of the international BGC-Argo program. BGC-Argo data were downloaded using the One-Argo-Mat toolbox for MATLAB. These data are collected and freely provided by the international Argo program and its contributing national programs (https://argo.ucsd.edu and https://www.ocean-ops.org).

We collected 35,493 profiles from 291 floats south of 30°S between January 2012 and December 2023 and applied standard quality control procedures to the data. The mixed-layer depth (MLD) was estimated using the density method74 with a threshold of 0.03 kg m−3, while the euphotic depth was determined through an iterative estimation based on chlorophyll profiles75.

Global ocean biogeochemistry hindcast

The Mercator-Ocean Global Ocean Biogeochemistry L4 product provides a daily and monthly three-dimensional reanalysis of biogeochemical fields from 1993 to the present at a 0.25° × 0.25° resolution across 75 depth levels. This product, generated using the latest versions of the NEMO and PISCES biogeochemical models, is freely accessible at https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00019. We extracted daily nitrate, silicate, and phosphate data for the Southern Ocean from 1998 to 2023.

Regional subdivision and masking

We divided the Southern Ocean into the STZ, SAZ, and POOZ based on hydrographic parameter isolines, following the major frontal structures that delineate these subregions26. Here, the POOZ is defined as the region between the polar front and the Seasonal Sea Ice Zone (SSIZ). Since SST beneath sea ice cannot be retrieved by satellites, areas within the SSIZ were masked to minimize the influence of sea-ice cover on MHW/MCS detection.

Definition and categorization of MHW and MCS

In this study, MHW and MCS were defined using the criteria established by Hobday et al.2,8,34. Specifically, an MHW was defined as a period of at least five consecutive days when SST exceeded the 90th percentile of a climatological baseline (1991–2020). Conversely, an MCS was defined as a period of at least five consecutive days when SST fell below the 10th percentile. The 1991–2020 climatology, recommended by the WMO, was used as the baseline. This period provides a balanced representation of recent climate conditions between the cooler 1990s and warmer 2010s, benefits from improved satellite data quality after the early 1990s, and aligns with the temporal coverage of the Chl-a dataset (1998–2023). Events occurring within less than three days of each other were aggregated into a single event to mitigate the impact of short-term fluctuations. To smooth SST data, we first applied an 11-day moving average followed by a 31-day moving average. This dual-stage smoothing process helps to reduce noise and capture the border temporal patterns of temperature anomalies.

For categorizing the severity of MHWs and MCS, we adopted the approach proposed by Hobday et al.8,34. This approach classifies events into four categories based on the magnitude of the peak temperature anomaly compared to the threshold distance, which is defined as the difference between the 90th percentile and the climatological mean:

-

(1)

Category I (moderate): The anomaly equals the threshold distance.

-

(2)

Category II (strong): The anomaly is twice the threshold distance.

-

(3)

Category III (Severe): The anomaly is three times the threshold distance.

-

(4)

Category IV (Extreme): The anomaly is four or more times the threshold distance.

These classifications were rounded down to the nearest whole number for consistency. For MCS, the categorization mirrored that of MHWs, with the threshold distance representing the maximum negative temperature anomaly below the 10th percentile. The development phase of MHW (Phase 1) was defined as the period from the onset of the heatwave to the peak temperature anomaly76, while the decay phase (Phase 2) extended from the peak anomaly (excluding the peak day) to the end of the heatwave.

PSC model

We employed a 17-parameter PSC model77, that uses daily Chl-a concentrations and SST as inputs. This model outputs the Chl-a concentration of three different PSCs. These size classes include picoplankton (<2 μm), nanoplankton (2–20 μm), and microplankton (>20 μm). For detailed methodological descriptions and parameter settings, refer to Supplementary Text 2. We evaluated the performance of the PSC algorithm in the Southern Ocean using in situ HPLC datasets (Supplementary Figs. 12, 13).

Since SST is included as an input variable, this may potentially introduce circularity in interpreting phytoplankton responses to temperature. To address this concern, we conducted additional analyses of model uncertainty and sensitivity. Our results indicate that incorporating SST leads to more robust and accurate PSC estimates compared with using Chl-a alone (Supplementary Figs. 14–16). Nevertheless, we additionally validated the anomalous variations in the outputs of the PSC model without SST input during MHWs and MCSs (Supplementary Fig. 17). The results demonstrate that, even without SST input, the conclusions of this study remain valid, effectively addressing the issue of circularity.

The in situ observational data used for model validation were derived from diagnostic pigment analysis of HPLC measurements78,79,80,81. The total Chl-a concentration was estimated as a weighted sum of seven diagnostic pigments, according to the following equation:

where Wᵢ and Pᵢ represent the weight and the corresponding diagnostic pigment, respectively. The diagnostic pigments include fucoxanthin, peridinin, 19′-hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin, 19′-butanoyloxyfucoxanthin, alloxanthin, total chlorophyll b, and zeaxanthin. The weights were calculated through multiple linear regression following Sun et al.77 (Supplementary Table S2). The estimated total Chl-a showed good agreement with in situ measurements (correlation coefficient = 0.982, root mean square difference in log10 space = 0.111)77. The Chl-a fractions of PSCs were then calculated using the following equations82:

where F₁, F₂, and F₃ represent the fractions of picoplankton, nanoplankton, and microplankton, respectively. Since fucoxanthin is also present in nanoplankton, a portion of fucoxanthin was assigned to nanoplankton83, i.e.:

Finally, the fractions of each size class were multiplied by the estimated total Chl-a to obtain the Chl-a concentrations of different phytoplankton size classes.

Estimate of mixed-layer averaged irradiance

The average irradiance within the mixed layer (the availability of light in the mixed layer) can be estimated using the following formula84.

where I0 represents the photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) incident at the sea surface, kd is the diffuse attenuation coefficient, and zml is the mixed-layer depth. kd data is provided by OC-CCI, and PAR data is provided by the GlobColour project with a spatial resolution of 4 km. The mixed-layer depth data are sourced from the Copernicus Marine Service (CMEMS) global ocean physics reanalysis product (GLORYS), covering the period from 1998 to 2023.

Definition of anomaly

In investigating MHWs and MCSs, we removed extreme values by calculating an 11-day running mean of sea surface temperature, followed by smoothing with a 31-day moving average. We applied a similar approach to daily chlorophyll-a and nitrate concentration data. To identify anomalies, we calculated the daily deviation from the climatological mean for each grid point. The climatology and anomalies were both based on a 1998–2023 baseline period.

In situ observation dataset

This study used 3508 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) samples collected from the surface layer of the Southern Ocean between 1998 and 2023. The data were sourced from the Global HPLC Phytoplankton Pigment Data Compilation, Version 2 dataset provided by PANGAEA and the Australian Marine Biogeochemical Optical Database (https://portal.aodn.org.au/search). In this study, only samples collected within the top 20 meters of the water column were used. To ensure the quality of the pigment data, HPLC data with Chl-a concentrations below 0.001 mg/m³ were excluded, and diagnostic pigments with concentrations below 0.001 mg/m³ were set to zero85. The HPLC data were retained only when the difference between total chlorophyll concentration and total accessory pigment concentration was less than 30% of the total pigment concentration86. Using seven pigment analyses, we calculated the Chl-a fractions for three phytoplankton categories (picoplankton, nanoplankton, and microplankton), with detailed formulas provided in the supplementary document. The results of the PSC model outputs were also validated.

Data availability

The daily SST-CCI (version 3.0) and SIC data are provided by ESA from their website: https://doi.org/10.5285/4a9654136a7148e39b7feb56f8bb02d2. The daily Rrs-CCI and kd (version 6.0) data are provided by ESA from their website: https://rsg.pml.ac.uk/thredds/catalog-cci.html. The PAR data are provided by GlobColour from their website: https://hermes.acri.fr/index.php?class=archive. The nitrate data provided by CMEMS from their website: https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00019. The MLD (GLORYS12V1) data provided by CMEMS from their website: https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00021. The HPLC data provided by PANGAEA from their website: https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.938703. The HPLC data provided by ADON from their website: https://portal.aodn.org.au/search. The data used to generate the figures presented in this study are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3021702187.

Code availability

The analyses were performed using MATLAB and Python; the main code used in this study is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1722329288, with BGC-Argo data processing based on code from https://github.com/NOAA-PMEL/OneArgo-Mat and MHWs/MCSs detection using code from https://github.com/ZijieZhaoMMHW/m_m hw1.0.

References

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. 9, 1324 (2018).

Frölicher, T. L., Fischer, E. M. & Gruber, N. Marine heatwaves under global warming. Nature 560, 360–364 (2018).

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Wang, Y., Kajtar, J. B., Alexander, L. V., Pilo, G. S. & Holbrook, N. J. Understanding the changing nature of marine cold-spell. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097002 (2022).

Dispert, B. oeningC. W., Visbeck, A., Rintoul, M. & Schwarzkopf, S. R. FU. The response of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to recent climate change. Nat. Geosci. 1, 864–869 (2008).

Swart, N. C., Gille, S. T., Fyfe, J. C. & Gillett, N. P. Recent Southern Ocean warming and freshening driven by greenhouse gas emissions and ozone depletion. Nat. Geosci. 11, 836–841 (2018).

Shi, J.-R., Talley, L. D., Xie, S.-P., Peng, Q. & Liu, W. Ocean warming and accelerating Southern Ocean zonal flow. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 1090–1097 (2021).

Schlegel, R. W., Darmaraki, S., Benthuysen, J. A., Filbee-Dexter, K. & Oliver, E. C. J. Marine cold-spells. Prog. Oceanogr. 198, 102684 (2021).

He, Q. et al. Enhancing impacts of mesoscale eddies on Southern Ocean temperature variability and extremes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2302292120–e2302292120 (2023).

Montie, S., Thomsen, M. S., Rack, W. & Broady, P. A. Extreme summer marine heatwaves increase chlorophyll a in the Southern Ocean. Antarct. Sci. 32, 508–509 (2020).

Jones, T. et al. Massive mortality of a Planktivorous seabird in response to a marine heatwave. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 3193–3202 (2018).

Gruber, N. et al. Trends and variability in the ocean carbon sink. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 119–134 (2023).

Hauck, J. et al. The Southern Ocean Carbon Cycle 1985–2018: mean, seasonal cycle, trends, and storage. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 37, e2023GB007848 (2023).

Frölicher, T. L. et al. Dominance of the Southern Ocean in anthropogenic carbon and heat uptake in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 28, 862–886 (2015).

Roemmich, D. et al. Unabated planetary warming and its ocean structure since 2006. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 240–245 (2015).

Buesseler, K. O. & Boyd, P. W. Shedding light on processes that control particle export and flux attenuation in the twilight zone of the open ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 1210–1232 (2009).

Boyd, P. W., Claustre, H., Levy, M., Siegel, D. A. & Weber, T. Multi-faceted particle pumps drive carbon sequestration in the ocean. Nature 568, 327–335 (2019).

Decima, M. et al. Salp blooms drive strong increases in passive carbon export in the Southern Ocean. Nat. Commun. 14, 425 (2023).

Boyce, D. G., Lewis, M. R. & Worm, B. Global phytoplankton decline over the past century. Nature 466, 591–596 (2010).

Thomas, M. K., Kremer, C. T., Klausmeier, C. A. & Litchman, E. A global pattern of thermal adaptation in marine phytoplankton. Science 338, 1085–1088 (2012).

Rodrigues, R. R., Taschetto, A. S., Sen Gupta, A. & Foltz, G. R. Common cause for severe droughts in South America and marine heatwaves in the South Atlantic. Nat. Geosci. 12, 620–626 (2019).

Crampton, J. S. et al. Southern Ocean phytoplankton turnover in response to stepwise Antarctic cooling over the past 15 million years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 6868–6873 (2016).

Thomalla, S. J., Nicholson, S.-A., Ryan-Keogh, T. J. & Smith, M. E. Widespread changes in Southern Ocean phytoplankton blooms linked to climate drivers. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 975–984 (2023).

Pinkerton, M. H. et al. Evidence for the impact of climate change on primary producers in the Southern Ocean. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 592027 (2021).

Martin, J. H., Gordon, R. M. & Fitzwater, S. E. Iron in Antarctic waters. Nature 345, 156–158 (1990).

Orsi, A. H., Whitworth, T. & Nowlin, W. D. On the meridional extent and fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 42, 641–673 (1995).

Holliday, N. P. & Read, J. F. Surface oceanic fronts between Africa and Antarctica. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 45, 217–238 (1998).

Boyd, P. W. et al. A mesoscale phytoplankton bloom in the polar Southern Ocean stimulated by iron fertilization. Nature 407, 695–702 (2000).

Flynn, R. F. et al. Nanoplankton: The dominant vector for carbon export across the Atlantic Southern Ocean in spring. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi3059 (2023).

Shiomoto, A., Sasaki, H. & Nomura, D. Size-fractionated phytoplankton biomass and primary production in the eastern Indian sector of the Southern Ocean in the austral summer 2018/2019. Prog. Oceanogr. 218, 103119 (2023).

Hayward, A., Pinkerton, M. H., Wright, S. W., Gutierrez-Rodriguez, A. & Law, C. S. Twenty-six years of phytoplankton pigments reveal a circumpolar Class Divide around the Southern Ocean. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 92 (2024).

Schlosser, T. L., Strutton, P. G., Baker, K. & Boyd, P. W. Latitudinal trends in drivers of the Southern Ocean spring bloom onset. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 130, e2024JC021099 (2025).

Hayward, A. et al. Antarctic phytoplankton communities restructure under shifting sea-ice regimes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 889–896 (2025).

Hobday, A. J. et al. Categorizing and naming marine heatwaves. Oceanography 31, 162–173 (2018).

Behrenfeld, M. J. Climate-mediated dance of the plankton. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 880–887 (2014).

Weis, J. et al. One-third of Southern Ocean productivity is supported by dust deposition. Nature 629, 603–608 (2024).

Deppeler, S. L. & Davidson, A. T. Southern Ocean phytoplankton in a changing climate. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 40 (2017).

Noh, K. M., Lim, H.-G. & Kug, J.-S. Global chlorophyll responses to marine heatwaves in satellite ocean color. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 64034 (2022).

Doney, S. C. Plankton in a warmer world. Nature 444, 695–696 (2006).

De Baar, H. J. W. et al. Importance of iron for plankton blooms and carbon dioxide drawdown in the Southern Ocean. Nature 373, 412–415 (1995).

Cassar, N. et al. The Southern Ocean biological response to aeolian iron deposition. Science 317, 1067–1070 (2007).

Jabre, L. J. et al. Molecular underpinnings and biogeochemical consequences of enhanced diatom growth in a warming Southern Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2107238118 (2021).

Le Grix, N., Zscheischler, J., Laufkötter, C., Rousseaux, C. S. & Frölicher, T. L. Compound high-temperature and low-chlorophyll extremes in the ocean over the satellite period. Biogeosciences 18, 2119–2137 (2021).

Hayashida, H., Matear, R. J., Strutton, P. G. & Zhang, X. Insights into projected changes in marine heatwaves from a high-resolution ocean circulation model. Nat. Commun. 11, 4352 (2020).

Richaud, B. et al. Drivers of marine heatwaves in the Arctic Ocean. Journal of Geophys. Res. Oceans 129, e2023JC020324 (2024).

Loscher, B. M., De Baar, H. J. W., De Jong, J. T. M., Veth, C. & Dehairs, F. The distribution of Fe in the Antarctic circumpolar current. Deep Sea Res. Part II Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 44, 143–187 (1997).

De Baar, H. J. W. & de Jong, J. T. M. Distributions, sources and sinks of iron in seawater. In The Biogeochemistry of Iron in Seawater (Wiley, 2001).

Lannuzel, D., Schoemann, V., de Jong, J., Tison, J.-L. & Chou, L. Distribution and biogeochemical behaviour of iron in the East Antarctic sea ice. Mar. Chem. 106, 18–32 (2007).

Oh, J.-H. et al. Antarctic meltwater-induced dynamical changes in phytoplankton in the Southern Ocean. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 24022 (2022).

Sun, W. et al. Marine heatwaves/cold-spells associated with mixed layer depth variation globally. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL112325 (2024).

Dong, S., Sprintall, J., Gille, S. T. & Talley, S. Southern Ocean mixed-layer depth from Argo float profiles. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 113, C06013 (2008).

DuVivier, A. K., Large, W. G. & Small, R. J. Argo observations of the deep mixing band in the Southern Ocean: a salinity modeling challenge. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 123, 7599–7617 (2018).

Rigby, S. J., Williams, R. G., Achterberg, E. P. & Tagliabue, A. Resource availability and entrainment are driven by offsets between nutriclines and winter mixed-layer depth. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 34, e2019GB006497 (2020).

Behrenfeld, M. J. & Boss, E. S. Student’s tutorial on bloom hypotheses in the context of phytoplankton annual cycles. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 55–77 (2018).

Diaz, B. P. et al. Seasonal mixed layer depth shapes phytoplankton physiology, viral production, and accumulation in the North Atlantic. Nat. Commun. 12, 6634 (2021).

Maranon, E. Cell size as a key determinant of phytoplankton metabolism and community structure. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 7, 241–264 (2015).

Zhan, W., Zhang, Y., He, Q. & Zhan, H. Shifting responses of phytoplankton to atmospheric and oceanic forcing in a prolonged marine heatwave. Limnol. Oceanogr. 68, 1821–1834 (2023).

Zhan, W. et al. Reduced and smaller phytoplankton during marine heatwaves in eastern boundary upwelling systems. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 629 (2024).

Jabre, L. & Bertrand, E. M. Interactive effects of iron and temperature on the growth of Fragilariopsis cylindrus. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 5, 363–370 (2020).

Hayashida, H., Matear, R. J. & Strutton, P. G. Background nutrient concentration determines phytoplankton bloom response to marine heatwaves. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 4800–4811 (2020).

He, W., Zeng, X., Deng, L., Chun Pi, Q. L. & Zhao, J. Enhanced impact of prolonged MHWs on satellite-observed chlorophyll in the South China Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 218, 103123 (2023).

Wolf, K. K. E. et al. Heatwave responses of Arctic phytoplankton communities are driven by combined impacts of warming and cooling. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl5904 (2024).

Acevedo-Trejos, E., Brandt, G., Bruggeman, J. & Merico, A. Mechanisms shaping size structure and functional diversity of phytoplankton communities in the ocean. Sci. Rep. 5, 8918 (2015).

Hillebrand, H. et al. Cell size as driver and sentinel of phytoplankton community structure and functioning. Funct. Ecol. 36, 276–293 (2022).

Farchadi, N., McDonnell, L. H., Ryan, S., Lewison, R. L. & Braun, C. D. Marine heatwaves are in the eye of the beholder. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 236–239 (2025).

Bopp, L. et al. Multiple stressors of ocean ecosystems in the 21st century: projections with CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences 10, 6225–6245 (2013).

Kwiatkowski, L. et al. Twenty-first century ocean warming, acidification, deoxygenation, and upper-ocean nutrient and primary production decline from CMIP6 model projections. Biogeosciences 17, 3439–3470 (2020).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Projected marine heatwaves in the 21st century and the potential for ecological impact. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 734 (2019).

Viljoen, J. J., Sun, X. & Brewin, R. J. W. Climate variability shifts the vertical structure of phytoplankton in the Sargasso Sea. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 1292–1298 (2024).

Embury, O. et al. Satellite-based time-series of sea-surface temperature since 1980 for climate applications. Sci. Data 11, 326 (2024).

Sathyendranath, S. et al. An ocean-colour time series for use in climate studies: the experience of the Ocean-Colour Climate Change Initiative (OC-CCI). Sensors 19, 4285 (2019).

Johnson, R., Strutton, P. G., Wright, S. W., McMinn, A. & Meiners, K. M. Three improved satellite chlorophyll algorithms for the Southern Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 3694–3703 (2013).

Westberry, T., Behrenfeld, M. J., Siegel, D. A. & Boss, E. Carbon-based primary productivity modeling with vertically resolved photoacclimation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 22, GB2024 (2008).

Talley, L. & Holte, J. A new algorithm for finding mixed layer depths with applications to Argo data and subantarctic mode water formation. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 26, 1920–1939 (2009).

Morel, A. & Maritorena, S. Bio-optical properties of oceanic waters: a reappraisal. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 106, 7163–7180 (2001).

Liu, H., Nie, X., Shi, J. & Wei, Z. Marine heatwaves and cold spells in the Brazil Overshoot show distinct sea surface temperature patterns depending on the forcing. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 102 (2024).

Sun, X. et al. Coupling ecological concepts with an ocean-colour model: Phytoplankton size structure. Remote Sens. Environ. 285, 113415 (2023).

Vidussi, F., Claustre, H., Manca, B. B., Luchetta, A. & Marty, J. C. Phytoplankton pigment distribution in relation to upper thermocline circulation in the eastern Mediterranean Sea during winter. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 106, 19939–19956 (2001).

Uitz, J., Claustre, H., Morel, A. & Hooker, S. B. Vertical distribution of phytoplankton communities in open ocean: an assessment based on surface chlorophyll. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 111, C08005 (2006).

Brewin, R. J. W. et al. A three-component model of phytoplankton size class for the Atlantic Ocean. Ecol. Model. 221, 1472–1483 (2010).

Hirata, T. et al. Synoptic relationships between surface chlorophyll-a and diagnostic pigments specific to phytoplankton functional types. Biogeosciences 8, 311–327 (2011).

Brewin, R. J. W. et al. Influence of light in the mixed-layer on the parameters of a three-component model of phytoplankton size class. Remote Sens. Environ. 168, 437–450 (2015).

Devred, E., Sathyendranath, S., Stuart, V. & Platt, T. A three component classification of phytoplankton absorption spectra: Application to ocean-color data. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 2255–2266 (2011).

Britten, G. L., Padalino, C., Forget, G. & Follows, M. J. Seasonal photoacclimation in the North Pacific Transition Zone. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26, e2022GB007324 (2022).

Claustre, H. et al. An intercomparison of HPLC phytoplankton pigment methods using in situ samples: application to remote sensing and database activities. Mar. Chem. 85, 41–61 (2004).

Aiken, J. et al. Phytoplankton pigments and functional types in the Atlantic Ocean: a decadal assessment, 1995–2005. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 56, 899–917 (2009).

Bai, Z. et al. Extreme temperature events reshuffle the ecological landscape of the Southern Ocean. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30217021 (2025).

Bai, Z. et al. Model code and output for: Extreme temperature events reshuffle the ecological landscape of the Southern Ocean. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17223292 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC). Specifically, Z.J. received support from NSFC Grants #42176173 and 42476168, while D.L. was supported by NSFC Grant #42406172. Additional funding was provided by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant # 2023A1515110837) awarded to D.L., and by the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (Grants #SML2024SP023 and SML2024SP029), and the Innovation Group Project of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (Grant #311020004), awarded to Z.J. R.J.W.B. is supported by a UKRI Future Leader Fellowship (MR/V022792/1) and the European Space Agency’s project Tipping points and abrupt changes In the Marine Ecosystem (TIME). The author acknowledges the European Space Agency (ESA) for providing daily Sea Surface Temperature (SST), Sea Ice Concentration (SIC), Diffuse Attenuation Coefficient (Kd), and Remote Sensing Reflectance (Rrs) data products through the Ocean Colour Climate Change Initiative (OC-CCI). The author also thanks the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS) for providing daily model data of Nitrate (NO₃), and Mixed-Layer Depth (MLD). Appreciation is extended to GlobColour for providing Level-3 (L3) daily Photosynthetically Available Radiation (PAR) data. Additionally, the author acknowledges the PANGAEA Data Publisher for Earth & Environmental Science and the Australian Waters Bio-optical Database (AWBD) for providing High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) datasets. We further acknowledge the Argo Program, which is part of the Global Ocean Observing System (https://www.seanoe.org/data/00311/42182/), as well as the Southern Ocean Observing System (SOOS) and the Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modeling (SOCCOM) Project, funded by the National Science Foundation, Division of Polar Programs (NSF PLR-1425989 and OPP-1936222), and supplemented by NASA. The BGC-Argo data were collected and made freely available by the International Argo Program and the national programs that contribute to it (http://www.argo.ucsd.edu, http://argo.jcommops.org).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Z.M. and D.L. conducted data processing and analysis under Z.J.’s instruction. H.W.B. provided the conceptual framework. H.W.B. and Q. C. contributed data and algorithms. B.Z.M. drafted the initial manuscript, and Z.J. and R.J.W.B. reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, Z., Deng, L., Brewin, R.J.W. et al. Extreme temperature events reshuffle the ecological landscape of the Southern Ocean. Nat Commun 17, 1278 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68029-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68029-0