Abstract

The emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in clinically important bacterial pathogens has severely compromised the effectiveness of commonly used antibiotics in healthcare. Acquisition and transmission of AMR genes (ARGs) are often facilitated by sublethal concentrations of antibiotics in microbially dense environments. In this study, we use sewage samples (n = 381) collected from six Indian states between June and December 2023 to assess the concentration of eleven antibiotics, microbial diversity, and ARG richness. We find antibiotics from seven drug classes and detect over 2000 bacterial amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Metagenomic (n = 220) and isolated genome sequences (n = 305) of aerobic and anaerobic bacterial species identify 82 ARGs associated with 80 mobile genetic elements (MGEs). These MGEs are predominantly present in multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial pathogens. Comparative core genome analysis of MDR bacterial isolates (n = 7166) shows strong genetic similarity between sewage-derived strains and clinical pathogens. Our results highlight sewage as a significant reservoir for ARGs, where genetic exchanges occur and facilitate the evolution and spread of AMR pathogens in both community and healthcare settings. Additionally, the dipstick-based assay developed for ARGs detection can be used for sewage surveillance in low-resource settings for better understanding of resistance prevalence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a critical and urgent global health crisis, threatening human, animal, and environmental health due to the increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial pathogens1. The emergence of MDR microbes is driven by the widespread use of antibiotics across various sectors, which exerts selective pressure that favors resistant variants over susceptible microorganisms2,3. Rapid advances in DNA sequencing technologies have enabled scientists worldwide to decode the metagenomes and whole genomes of diverse microorganisms, facilitating the monitoring of AMR genes (ARGs) and their genetic associations with mobile genetic elements (MGEs). These elements play a crucial role in the rapid spread of resistance through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) among both closely and distantly related microbial species.

The growing need for comprehensive global genomic pathogen surveillance has become increasingly urgent as pathogens continuously evolve. The recent COVID-19 pandemic, one of the most devastating respiratory infectious diseases, highlighted the critical importance of real-time global surveillance systems to detect and track pathogens. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) in close collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Organization of Animal Health (WOAH) has developed the One Health AMR Global Action Plan (GAP), to mitigate the AMR crisis. This tripartite organization (FAO-WOAH-WHO) is tasked to oversee the development and execution of National Action Plans (NAPs) and strategies which aim at reversing AMR4. The WHO is also dedicated to overseeing water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) efforts as well as wastewater management, which are crucial for mitigating and reducing the impact of AMR in sewage. An in-depth study on the AMR patterns and burden in sewage and leveraging this data can significantly advance WASH strategies, enabling precise tracking and early detection of AMR pathogens.

Sewage water constitutes a dynamic and complex ecological matrix that plays a pivotal role in the emergence and dissemination of AMR. Characterized by densely populated and diverse microbial communities, this often poorly regulated environment serves as a critical hotspot for HGT, facilitating the exchange of ARGs among bacterial species5. These exchanges are facilitated by MGEs, such as plasmids and transposons, which act as key drivers in the spread of resistance traits. Resistant pathogens originating from sewage systems pose a significant public health risk, with potential transmission to human populations through various pathways such as environmental discharge, agricultural reuse, and contaminated water sources6. In response to the growing need for efficient monitoring tools, we recently applied a high-throughput, culture-independent dipstick-based molecular assay for the rapid detection of bacterial species and viral variants circumventing the need for traditional culturing or genomic sequencing7,8. This approach complements recent advances in genomic and metagenomic surveillance, which have revolutionized our capacity to investigate AMR in complex matrices like wastewater9,10. Integration of next-generation sequencing, quantitative PCR, and meta-transcriptomics now enables high-resolution profiling of microbial communities and resistome dynamics, uncovering not only the breadth of ARGs present but also the molecular mechanisms driving their spread11,12. However, data from Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), including India, remain limited. In India, pilot studies under national AMR programs are emerging, though coverage remains limited13. Globally, many countries are increasingly implementing wastewater-based surveillance systems that integrate genomic approaches to monitor ARGs and resistant pathogens. This integrated strategy enables early detection of emerging resistance trends and supports evidence-based public health interventions across both clinical and environmental settings. Despite these breakthroughs, significant knowledge gaps remain particularly concerning the environmental and biological factors that modulate HGT and the precise role of MGEs in real-time ARG transmission. Addressing these gaps is vital for developing targeted interventions to curb the environmental spread of AMR. This study supports the One Health Approach and contributes valuable insights into AMR dynamics in resource-constrained environments, aligning with the global trend of wastewater-based surveillance for comprehensive AMR monitoring and informed public health interventions. We utilize a suite of advanced molecular and computational tools to elucidate the drivers and dynamics of AMR propagation in sewage water, contributing to a deeper understanding of this under-explored but globally significant reservoir of resistance.

Results

Quantification of antibiotic contamination in urban sewage using QTRAP mass spectrometer

During June to December 2023, a total of 381 sewage samples were collected from six different states located across the country, including the national capital region (NCR) of India (Supplementary Fig. S1). A total of 102 sewage samples, collected across multiple rounds from various states, were analysed to quantify the concentrations of eleven antibiotics representing seven distinct drug classes using QTRAP mass spectrometer (Fig. 1). To ensure representative coverage across geography and time, 102 samples were selected from the larger set based on spatiotemporal diversity. The calibration curves generated using pure drug compounds were linear across the tested concentration ranges from approximately 0.1 to 500 ng/ml (Supplementary Data S1). The concentrations of tetracycline, amoxicillin, and spectinomycin in sewage were found to be substantially higher (>10 ng/ml) compared to other antibiotics. We observed the highest fluctuation of concentration in spectinomycin and amoxicillin in the sewage among all the eleven antibiotics, depending on the site and date of sample collection. The details of the regression equation, correlation coefficient (R2), limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantification (LOQ) along with the concentration data of antibiotics generated in this study were included in Supplementary Data S1a–l. Among 11 antibiotics analysed, kanamycin (66.6%), azithromycin (55.8%), and spectinomycin (50%) were most frequently detected above LOQ, however ampicillin, polymyxin-B, and colistin were not detected. Detected concentrations ranged from 0.049 to 18.711 ng/mL, with tetracycline and spectinomycin showing the highest maximum values.

The figure illustrates concentrations of different antibiotic residues in sewage water samples (n = 102). Each dot represents the concentration of specific antibiotics belonging to macrolide, rifampin, tetracycline, beta-lactams, polymyxin, aminoglycosides, and quinolone group within the sample. The image was prepared using the Graph pad Prism v 10. The statistical significance was assessed by comparing the concentrations of different antibiotics to that of ampicillin which was undetectable through Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS-MS) in test samples. Statistical analysis were performed using two-sided t-test, with results indicated as non-significant (ns), or significant (marked with *). **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

High-throughput monitoring of sewage resistome using dipstick-based molecular assay

Given the widespread presence of multiple antibiotics in sewage across the sites, we expanded our analysis to screen for ARGs (n = 16) using a culture-independent dipstick-based molecular assay7,8. Our findings revealed significant heterogeneity in the prevalence of ARGs across different samples (Fig. 2). Notably, six ARGs-blaTEM, catB, aac(6)-Ib, sul1, ermB and dfrA1 were present in more than 50% of the samples tested in this study. The lowest prevalence was observed for the oqxA, followed by blaKPC, and aadA1 ranging from (1 to 4%). Other prominent ARGs detected including mphA (50%), sul2 (45%), blaOXA (42%), blaCTX-M (39%), and qnrS (38%) (Supplementary Data S2). A comparative assessment employing QTRAP mass spectrometry for quantification of antibiotic residues and dipstick-based assays for ARG detection consistently demonstrated the co-occurrence of antibiotics, including azithromycin, amoxicillin, and kanamycin, with their respective resistance genes (mphA, ermB, blaTEM, blaCTX-M, blaOXA, and aac(6’)-Ib) across both platforms (Supplementary Data S3a).

Metagenomic investigation of urban sewage microbiomes diversity

A total of 220 sewage samples were analysed using metagenomic profiling. Sequencing of the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene yielded 16,679,255 high-quality reads. The number of non-chimeric reads ranged from a minimum of 25,762 to a maximum of 123,274 after quality filtering with an average read count of 75,815 ± 12,935.56 (Supplementary Data S4). We compared the sewage microbiome profiles between community settings and hospital outlets in Faridabad, Haryana using longitudinal samples collected over seven months. The study included five community sites Badkhal (n = 27), Ballabgarh (n = 27), Dabua colony (n = 27), Parvatiya colony (n = 26), and Sanjay colony (n = 26), and two hospital outlets: BK hospital (n = 21) and ESIC hospital (n = 18). Analysis of alpha diversity indices (Observed, Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson) revealed a significant difference between community and hospital sewage microbiomes in Haryana (BH adjusted p < 0.05) (Fig. 3a). Bray-Curtis distance matrices showed variation captured by 21.3% on the 3D Principal Coordinates Analysis 1 (PCoA1), 14.1% on the PCoA2, and 11.1% on PCoA3 in the ordination plot (Fig. 3b). To validate the patterns observed in the 3D PCoA, we also performed a non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity. The NMDS plot revealed clustering patterns across the seven sites that were broadly consistent with the PCoA results, reinforcing the presence of temporal structure in the microbial communities (Supplementary Fig. S2a). The NMDS stress value was 0.136, indicating a good fit of the data in three dimensions. Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) confirmed that Faridabad sites significantly influenced community composition in both analyses (R² = 0.111, p = 0.001). At the genus level, Aliarcobacter was notably elevated across all the collected sites, however, for ESIC hospital (6.3%), its relative abundance was lower compared to BK hospital (20.5%). In hospital outlets, the relative abundance of genera such as Aeromonas, Escherichia and Trichococcus were found to be increased, while Romboustia was lower compared to community settings. Other Gram-negative pathogens like Klebsiella, Acinetobacter, and Pseudomonas were prevalent in both environments (Fig. 3c). Specifically, at the species level, Trichococcus flocculiformis and Aeromonas veronii were more abundant in hospital sewage, while the abundance of Aliarcobacter cryaerophilus remained similar across both settings, with a slight decline at the ESIC outlet (Fig. 3d).

a Violin plots showing different alpha-diversity measures between the community and hospital sewage water sites of Haryana; Observed, Chao1, Shannon and Simpson index. In the violin plot, the central box represents the interquartile range (IQR), with a line inside indicating the median. The whiskers extending to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 × IQR, and any points beyond as outliers, summarizing the distribution, spread, and skewness of the data. Group differences were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by pairwise comparisons with Dunn’s post hoc test, applying the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure to correct for multiple testing. b Beta diversity represented by principal coordinate analysis plots (3D PCoA) to visualize the difference in sewage microbiome structure between the seven sites of Haryana. Each shape represents a particular sample, which is color-coded based on the collection sites of the current study. Statistical significance of variance was calculated using permutational multivariate analysis of variance, which reflected that the sites had a variance among them (R² = 0.111, p = 0.001). Heatmap showing the mean relative abundance of top bacterial taxa in the c genus d species level in all the seven sites of Haryana. The color gradient (blue to red) signifies minimum to maximum relative abundance value. The analysis for a–d included five community sample sites, viz. Badkhal (n = 27), Ballabgarh (n = 27), Dabua colony (n = 27), Parvatiya colony (n = 26), and Sanjay colony (n = 26), and two hospital outlets: BK hospital (n = 21) and ESIC hospital (n = 18). The samples were collected longitudinally from different locations of Faridabad, Haryana from June to December, 2023. e Violin plot depicting Observed, Chao1, Shannon and Simpson indices in all the community sewage sites from the six states of India (Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by pairwise comparisons with Dunn’s post hoc test, BH corrected). The box in violin plot shows the IQR, median as a line in the box, and whiskers to values within 1.5 × IQR, and any points beyond as outliers, summarizing data distribution and spread. f Bray-Curtis’s distance-based 3D PCoA between the six states were statistically confirmed by PERMANOVA, which showed significant variation among the states (R² = 0.188, p = 0.001). g Heatmap illustrating the predominant microbial species present in the community sewage samples across the sampled states viz. Assam (AS), Haryana (HR), Jharkhand (JH), Uttarakhand (UK), Uttar Pradesh (UP), and West Bengal (WB). The color code in the heatmap is according to the relative abundance of the bacterial taxa. The analysis for e–g included community sewage samples from different locations of Haryana (n = 133), West Bengal (n = 8), Uttar Pradesh (n = 10), Uttarakhand (n = 4), Assam (n = 16) and Jharkhand (n = 10). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

In this study, we collected community sewage samples from various Indian states, including Assam (n = 16), Jharkhand (n = 10), Uttar Pradesh (n = 10), West Bengal (n = 9), and Uttarakhand (n = 4). We then compared these datasets with community-level data from Haryana. Alpha diversity indices like Observed, Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson were calculated and compared across all six states. Haryana exhibited significantly higher alpha diversity than the other five states (Fig. 3e), indicating a richer bacterial diversity in its sewage microbiome. Specifically, the observed species ranged from 192 to 879, Shannon indices from 4.15 to 6.4, and Simpson indices from 0.975 to 0.99. Beta diversity analysis using 3D PCoA and NMDS (Stress-0.141) revealed distinct microbial community structures across sewage samples from six Indian states. The observed geographic clustering was statistically supported by PERMANOVA (R² = 0.188, p = 0.001), highlighting significant state-level variation. (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. S2b). The species with the most assigned sequencing fragments include A. cryaerophilus and Aeromonas caviae across the states. Several other bacteria with known pathogenic potential, including Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus species, and Acinetobacter baumannii, were also found to be prevalent in sewage samples collected from various states across India (Fig. 3g).

In our shotgun sequencing analysis, we sequenced the metagenomic DNA from a subset of 167 samples, 143 from community source and 24 from hospital outlets, to assess taxonomic composition and diversity metrics. Significant differences in alpha diversity indices (Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson) were observed between the community and hospital settings (Fig. 4a). Bacteroides graminisolvens, A. cryaerophilus and Aeromonas caviae were the most dominant taxa in sewage water across both sequencing strategies. Taxonomic analysis showed a notable enrichment of Aeromonas and Trichococcus in hospital sewage outlets, aligning with findings from amplicon sequencing data (Fig. 4b and c). Additionally, pathogenic bacteria such as E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, various species of Aeromonas and Pseudomonas were commonly detected in sewage wastewater of community and hospital sources in both sequencing approaches (Fig. 4c).

a The box plot represents the alpha diversity indices; Chao1 (p = 0.02), Shannon (p = 0.00039), Simpson (p = 0.0031) between community (n = 143) and hospital (n = 24) settings. Differences between the two groups were assessed using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Mann–Whitney U test). The line within the box displays the median, the IQR as the box, whiskers extending to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 × IQR, and any points beyond as outliers, summarizing the distribution of the data. The heatmap illustrates the distribution of sewage microbial taxa at b the genus level and c the species level, with the color code representing the relative abundance of the bacterial taxa. The color gradient (blue to red) signifies minimum to maximum relative abundance value. Additionally, there is a heatmap displaying the distribution of sewage resistome which are associated with taxonomically resolved metagenome assembled genome (MAGs) in the community and hospital sewage outlets for d antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and e efflux genes detected in shotgun sequencing analysis.

Temporal variations in sewage microbiomes

Longitudinal sampling in Faridabad, Haryana from June to December 2023 revealed temporal shifts in the sewage microbiome. The clustering points in the 3D PCoA plot of each month indicates temporal variation in microbial community composition (R2 = 0.213, p = 0.001). Notably, samples from November and December showed a tendency to cluster separately, suggesting gradual temporal shifts in community composition toward the end of the sampling period. In contrast, samples from June and July were more diffusely distributed, though some degree of grouping was still apparent, pointing to greater variability or transitional dynamics. Samples from August, September, and October displayed moderate overlap, suggesting a period of more gradual change or mixing in community composition (Fig. 5a). These temporal trends were further supported by 3D NMDS analysis, which revealed comparable patterns of month-wise clustering (Supplementary Fig. S2c). Together, these patterns imply a temporal progression in sewage-associated microbial communities, with both distinct and transitional phases observed across the sampling timeline.

a A 3D PCoA (Principal Coordinate Analysis) plot was generated to visualize variations in the sewage microbiome structure across different months. Each dot corresponds to a specific sample, with colors representing the respective months. The statistical significance of variance was assessed using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA), revealing a significant variance among the sites (R2 = 0.213, p = 0.001). Box plots illustrating different alpha-diversity metrics include b Observed, c Shannon, and d Simpson indices, with statistical significance observed. Group differences were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by pairwise comparisons with Dunn’s post hoc test. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure was applied to adjust for multiple testing. The box represents the interquartile range (IQR), the median value is indicated by a line within the box, and whiskers extend to the extreme values (within 1.5 × IQR). The bars represent mean ± standard deviation, SD. e A heatmap depicting the distribution of highly prevalent bacterial taxa in terms of relative abundance at the species level across different months (from June to December 2023). The color code corresponds to the relative abundance of the bacterial taxa. The analysis included sewage samples collected longitudinally from June to December at multiple time points. The number of samples collected per month was as follows: June (n = 15), July (n = 28), August (n = 28), September (n = 28), October (n = 34), November (n = 18) and December (n = 21). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

The alpha diversity of sewage microbial communities in Faridabad measured by Observed richness (Kruskal-Wallis, p = 1.81e-08), Shannon (p = 1.443e-09), and Simpson (p = 1.703e-09) indices, showed monthly variation. Diversity peaked from June to August and declined from September through December (Fig. 5b–d). We also examined how the abundance of bacterial taxa varied across different months. The relative abundance of A. veronii and T. flocculiformis significantly decreased from June to August, followed by a gradual increase starting in September, reaching higher levels by December. In contrast, Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum, Streptococcus equinus, and Bifidobacterium adolescentis were less abundant in July and August but showed an increase in September and October, followed by a decline in November and December. Aliarcobacter ellisi, Aliarcobacter faecis, P. aeruginosa, Tolumonas auensis, and Thauera selenatis were abundant in June through October, with their levels decreasing in November and December. Notably, Pseudomonas lundensis was completely absent from June to October but showed increased abundance in November and December (Fig. 5e).

To elucidate temporal patterns in microbial community structure, we performed a longitudinal, month-wise analysis of the sewage microbiome in Faridabad, with a specific focus on contrasting community and hospital sources, given previously observed significant differences between these settings (Fig. 3a). Month-wise analysis showed significantly higher microbial diversity in community sewage samples compared to the hospital sites. The Observed index was significantly higher in August, September, and October, while Shannon and Simpson indices indicated greater richness and evenness in July, August, and October (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p < 0.05). No comparison was made for June due to the absence of hospital samples (Supplementary Fig. S3a–c). These findings were further supported by the 3D PCoA, which revealed a clear separation between community and hospital samples across the examined months, indicating distinct microbial community structures influenced by both sampling source and time (R² = 0.2872, p = 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S3d). The 3D PCoA accounted for a total of 47.7% of the variance across the first three axes, underscoring its robustness in capturing community differences. Similarly, the 3D NMDS analysis echoed these patterns, further validating the temporal and source-based differentiation in microbial composition (Stress = 0.136, R² = 0.2872) (Supplementary Fig. S2d). Next, we analysed the variations in community sewage microbial profiles across different Indian states by comparing them to Haryana using samples collected in December, the month during which all six states were sampled. We observed that A. cryaerophilus was highly prevalent in Haryana, Uttarakhand, and Uttar Pradesh, but present at much lower levels in the other states. In contrast, A. caviae and A. veronii were enriched in Jharkhand and Assam, respectively. E. coli was found to be dominant in Uttarakhand, while its abundance remained low in the other states during the same month. These findings suggest that, despite uniform sampling time, microbial compositions varied substantially across geographical locations, highlighting the influence of region-specific environmental and anthropogenic factors on sewage microbiomes (Supplementary Fig. S3e).

The resistomes diversity and dynamics in urban sewage

We aimed to analyse the resistome profile in both the community and hospital outlets sewage water sites using assembled metagenomic shotgun sequences. A total of 403 resistomes were obtained across 167 samples collected from six Indian states (Supplementary Data S5). Out of these, 248 resistomes are associated with 893 taxonomically resolved metagenomic assembled genomes (MAGs) out of 2214 bins. We identified a total of 170 distinct ARGs encoding resistance to 16 drug classes having enzyme mediated or target alteration mechanisms and 78 efflux genes, with varying abundances across the two different sites. The majority of the genes belonged to the beta-lactam, aminoglycoside, macrolide, vancomycin and sulphonamide classes. Notably, among all the 170 ARGs, mphE, msrE, mphA, and mphB from the macrolide class were the most common across the samples, while blaOXA-427, E. coli-blaampC, E. coli-blaampH, blaMOX-6, were prominent from the beta-lactamase class (Supplementary Data S6a). Additionally, qnrS1 and catQ from the fluoroquinolone and chloramphenicol classes were observed in multiple samples across community and hospital sites. mphE, msrE, qnrS1, and mphA were found at higher levels in community sewage sites, while blaOXA-427, dfrG, IsaE, ermT, qnrB4, blaOXA-12, tetM and tetQ were more prevalent in hospital settings. (Fig. 4d). We identified 78 efflux genes, with CRP being the most common across all samples, while the emrA, emrB, emrR, mexF and tolC gene was more prevalent in hospital settings (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Data S6b). A comparison of ARGs identified through shotgun sequencing and those detected using the dipstick-based assay revealed strong concordance between the two approaches for several ARGs such as blaTEM, blaKPC, blaOXA, dfrA1, sul1, and tetB (Supplementary Data S3b). Further, a correlation analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between antibiotic residues detected through LC-MS/MS and the abundance of the corresponding resistance genes identified through shotgun metagenomic sequencing. The resulting plot revealed positive correlation between the macrolide antibiotic (azithromycin and erythromycin) residues and the abundance of mph and msr genes, nalidixic acid with qnr and oqxB genes, kanamycin and spectinomycin residues with aad genes, and amoxicillin residues and bla gene (blaOXA) (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Network analyses of bacterial species and their associated ARGs frequently uncover co-occurrence patterns, suggesting which bacterial species are likely to contain or share resistance genes. A network graph depicting bacterial species-ARG association showed clear separation according to species-level taxonomy (Fig. 6). Proteobacterial species such as K. pneumoniae, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, Enterococcus faecium, and Enterobacter spp. harbored a variety of ARGs. Some ARGs like aac(3)-IId, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, qnrS1, blaTEM, mphA, mphE, msrE and sul2 are shared among them, while others are uniquely seen in their respective species. E. coli, in particular, have the highest number of assigned ARGs and shared many with other Gram-negative bacteria including K. pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp. and others (Fig. 6). We also identified colistin resistant genes mcr-3, mcr-3.8, mcr-5, and mcr-9 among several Gram-negative pathogens, including E. coli, Enterobacter mori, E. cloacae and A. veronii. Among Gram-positive bacteria, Enterococcus have the most diverse ARGs, which are shared with other Gram-positive species like Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus paranthracis, and several Streptococcus species (Fig. 6).

This network analysis illustrates the associations between bacterial taxa and their corresponding ARGs, as identified through shotgun metagenomic sequencing of sewage samples (n = 167). In the network diagram, red rectangular boxes represent bacterial species detected in the samples, while the colored ovals correspond to different antibiotic drug classes associated with the identified ARGs. Edges (lines) between nodes indicate the presence of specific ARGs within a given bacterial taxon, suggesting a potential reservoir for resistance against particular antibiotic classes.

Functional metagenomic analysis of the sewage samples has revealed several pathways potentially involved in the degradation of xenobiotic pollutants. We employed Illumina shotgun sequencing reads to investigate KEGG pathways involved in biodegradation across sewage samples from community and hospital sites in Haryana, extending the comparison to community sewage from other Indian states. A total of 20 KEGG categories associated with various xenobiotic compounds were identified, including aminobenzoate, atrazine, benzoate, caprolactam, chloroalkane, chlorocyclohexane, dioxin, ethylbenzene, furfural, naphthalene, nitrotoluene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, steroids, toluene, and xylene, along with drug metabolism pathways mediated by cytochrome P450. Among these, the drug metabolism via cytochrome P450 and benzoate degradation pathways were found to be dominant across most sites. In contrast, pathways such as atrazine degradation and chlorocyclohexane/chlorobenzene degradation are present at relatively lower abundances (Supplementary Fig. S5a). While the overall xenobiotic degradation profiles are largely similar between community and hospital samples in Haryana, region-specific differences were evident when comparing across states. Notably, the benzoate degradation pathway was highly enriched in Uttarakhand relative to other regions. In West Bengal, lower abundances of dioxin, atrazine, toluene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and xylene degradation pathways were observed, whereas drug metabolism and steroid degradation was comparatively enriched (Supplementary Fig. S5b). These findings underscore geographic variability in microbial functional potential for xenobiotic degradation, likely driven by environmental and anthropogenic factors. These variations highlight regional differences in the microbial capacity for xenobiotic degradation in sewage, potentially influenced by local environmental conditions, population lifestyle, industrial discharge, and pollution levels.

Antimicrobial resistance phenotypes of aerobic and anaerobic bacterial taxa isolated from urban sewage

Culturomics analysis of the samples identified a total of 964 bacterial isolates, encompassing both Gram-negative and Gram-positive from sewage water. The bacterial isolates include MDR strains with aerobic and facultative anaerobic metabolic traits. Among the Gram-negative bacteria, notable isolates include E. coli (n = 264), Morganella morganii (n = 127), P. mirabilis (n = 72), K. pneumoniae (n = 70), Enterobacter spp. (n = 22), Pseudomonas spp. (n = 18), and A. baumannii (n = 8). In contrast, the Gram-positive bacteria identified are mostly facultative anaerobes, with E. faecium being the most prevalent (n = 138) (Supplementary Data S7a).

All the aerobic isolates (n = 627) and a subset of facultative anaerobic isolates (n = 54) were subjected to susceptibility testing against 32 antibiotics from 10 different classes (Supplementary Data S7b & S8a). A majority of these isolates (93.8%; n = 639/681) demonstrated resistance to more than 10 antibiotics (Fig. 7a). Notably, Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens especially K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa and Enterobacter spp. exhibited resistance to multiple antimicrobial classes such as aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and tetracycline. Among Gram-positive bacteria, most E. faecium isolates were resistant to most of the tested antibiotics, including erythromycin and vancomycin (Fig. 7b, Supplementary Data S8b).

a Whisker plot illustrates the distribution of sewage isolates resistant to the total number of antibiotics tested. The central line represents the median, the bounds of the box indicate the interquartile range, and the whiskers denote the minimum and maximum values. b The heatmap represents the overall percentage of resistance among bacterial isolates to various antibiotic classes tested. The white-blue gradient in the heatmap reflects the proportion of resistance across isolates, transitioning from white (0%, indicate complete susceptibility) to deep blue (100%, indicating fully resistant).

In accordance with the WHO’s 2024 guidelines, the study isolates were categorized into critical and high-priority groups. All the A. baumannii study isolates were classified as critical priority pathogens (CPP), due to their resistance to at least one carbapenem antibiotic. Furthermore, among the tested enterobacterial isolates, 69.3% were found to be carbapenem-resistant which includes Enterobacter spp. (78.8%), Citrobacter spp. (72.7%), Proteus spp. (72.2%), K. pneumoniae (70.5%), Morganella spp. (87.8%) and E. coli (57.7%). However, 84.7% of these Enterobacterial isolates exhibited resistance to cephalosporins that are also categorized as CPP. Conversely, the high-priority pathogens identified in this study included vancomycin-resistant E. faecium, which accounted for 18.8% of the tested isolates, and carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa, with a concerning resistance rate of 88.8% (Supplementary Data S7c).

Genomic insights into MDR bacterial pathogens isolated from urban sewage

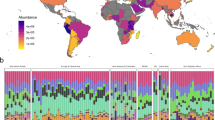

A total of 305 isolates cultured from wastewater and hospital sewage outlets were sequenced and analysed to understand their genetic relatedness and genetic signatures. These isolates belonged to 16 different genera and 31 different species; predominantly the Gram-negative Escherichia (n = 69), Klebsiella (n = 40), Morganella (n = 33), Providencia (n = 31), Citrobacter (n = 29), Proteus (n = 25), and the Gram-positive Enterococcus (n = 22). The overview of all the isolates is shown in the phylogenetic tree based on the 5S, 16S and 23S rRNA sequences (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Data S9a). Global phylogeographical analysis was done to understand the relatedness of the Indian isolates from the sewage and the global representative collection of clinical isolates including E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, E. faecium, and the emerging pathogens M. morganii, P. mirablis, Citrobacter werkmani, and Providencia rettgeri from 2019 to 2023 (Supplementary Data S9b–j). The phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the core-gene SNPs (Fig. 8b–d, Supplementary Fig. S6a–f). The phylogeographical analysis of all the 2769 E. coli isolates (2700 clinical and 69 sewage) showed that these isolates were quite diverse (Fig. 8b) and widely distributed into eight different phylogroups (A, B1, B2, C, D, E, F, and G). However, the isolates obtained from sewage belonged to phylogroups A, B1, B2, C, D, and F and among which B1 (n = 22) and A (n = 20) were the most prevalent. Although B2 isolates were relatively more common in the global clinical cases, this phylogroup was not as prevalent in the Indian clinical cases or the sewage (n = 3). The sewage isolates belonged to 22 different STs/lineages, the predominant were ST167, ST410, ST448, ST648 and ST5869. A few of these isolates that belonged to ST167, ST2083, ST410 and ST448 clustered with the Indian clinical isolates.

a Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the similarity of the 16S, 23S and 5S rRNA gene sequences gives an overview of the isolates from sewage. Phylogenomic trees based on the core-gene SNPs shows the genetic relatedness of sewage isolates with the global clinical cases show b E. coli (n = 2769), c K. pneumoniae (n = 1314), d A. baumannii (n = 697). The trees are annotated with metadata such as sample source, geographical location and year of collection. The scale bar is indicated in the figures.

The phylogeographical analysis of all 1314 K. pneumoniae isolates (1281 clinical and 33 sewage) showed these isolates to be less diverse and distributed into distinct clades (Fig. 8c). Although the study isolates are distributed on different clades, these isolates clustered closely with the Indian clinical isolates. The most prevalent STs in sewage isolates were ST15, ST37, and ST16 which were also observed to be widely isolated from clinical cases in the US, East and South-East Asia. Although not prevalent, ST11, ST101, ST231 and ST147 found in sewage isolates were also observed in Indian clinical cases. The phylogeographical analysis of 697 A. baumannii isolates (689 clinical and 08 sewage) showed that the isolates are clonal (Fig. 8d). The sewage isolates belonged to ST2 which was found to be the prevalent circulating ST in the clinical settings of India and also in global cases. The P. aeruginosa isolates (774 clinical and 06 sewage) segregated into different clades and the study isolates clustered with the clinical isolates from India, East Asia and North America (Supplementary Fig. S6a). The ST357, one of the dominating STs in the clinical cases of India and East Asia was also observed in sewage. In the case of E. faecium, the isolates (639 clinical and 21 sewage) were quite diverse on the phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. S6b). The most prevalent ST in sewage isolates was ST80 which was also observed to be prevalent in both Indian and global clinical settings. Although most of the study isolates were positioned adjacent to the clinical isolates from Europe and East Asian countries on the tree, few of the sewage isolates clustered with the Indian clinical isolates. The M. morganii isolates (196 clinical and 33 sewage) were clonal forming distinct clades with most isolates clustering with clinical isolates from East Asia, Europe, Oceania and South America (Supplementary Fig. S6c). The P. mirabilis sewage isolates are segregated to different clades clustering with clinical isolates from North America (Supplementary Fig. S6d).

Genetics of antibiotic resistance traits of MDR bacterial pathogens

The analysis revealed a wide range of ARGs conferring resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics, some of which were species-specific while others were shared among different bacteria. Morganella, Citrobacter and Aeromonas showed the presence of limited ARGs when compared with other Gram-negative pathogens such as, Escherichia, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella and Acinetobacter spp. The resistance encoded was either through enzymatic inactivation, target alteration or antibiotic efflux (Fig. 9, Supplementary Figs. S7–S8). Majority of ARGs encoded resistance to beta-lactams. The blaADC, blaSHV, blaOKP, blaPDC, blaCPH were specific to A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella quasipneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and A. veronii, respectively, with almost all the genomes of these species having the specific ARGs. Although not specific to M. morganii, blaDHA was found to be quite prevalent in M. morganii with the presence of one or the other allele in its genome. Except in Enterococcus, the Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), blaOXA was found in all the species. However, the allele varied from species to species, some being organism-specific, such as blaOXA-66 and blaOXA-23 were specific to A. baumannii, blaOXA-50 to P. aeruginosa, and blaOXA-12 to A. veronii. Similarly, the carbapenemase blaNDM-1 was observed in Providencia, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella and Enterobacter, while blaNDM-5 was observed only in E. coli. The most prevalent beta-lactamase genes in E. coli were the ESBLs blaTEM (n = 37/69), followed by blaCTX-M (n = 23/69). Intriguingly, none of the Enterococcus isolates showed the presence of any beta-lactamase genes (Fig. 9, Supplementary Data S10a–i).

The aminoglycoside modifying enzymes (AMEs) viz. aph(3”)-Ib or strA and aph(6)-Id or strB were quite prevalent in Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Proteus, Escherichia and Klebsiella. Interestingly, Proteus genomes have more of AMEs compared to other ARGs. While armA was prevalent in A. baumannii, rmts were observed in Pseudomonas and Enterobacterales. The aac(6’)-Ie-aph(2”)-Ia complex and ant(6)-Ia were observed only in E. faecium. The allele aac(6’)-Ii was specific to the Gram-positive Enterococcus and was present in almost all of the E. faecium (n = 20/21). For resistance to macrolides, the msrE and mphE were prevalent in the non-fermenters such as Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas and Enterobacter spp. The mphA was observed more in E. coli and Klebsiella, while mphB was detected in nearly all E. coli (n = 66/69). The msrC was specific to E. faecium and present in almost all isolates (n = 19/21). Resistance to tetracyclines was mostly encoded by efflux genes and amongst tetA and tetB were the most prevalent ones. All the 8 Acinetobacter isolates had the tetB and the adeABC and the adeFGH efflux system genes for resistance towards tetracyclines. The tetE is specific to Aeromonas, tetG to Pseudomonas, tetJ to Proteus, and tetL, tetM and tetU to Enterococcus. Several efflux genes, including those encoding multidrug efflux proteins, were identified in the isolates, with many being species-specific. E. coli had the highest number of efflux genes, followed by P. aeruginosa where nearly all isolates carrying Pseudomonas-specific mex, mux, opm, opr, triA, triB and triC genes confer resistance to multiple drug classes (Fig. 9b). Genes providing resistance to trimethoprim (dfr) were harbored by all the species, with dfrA1 being the most prevalent, majorly observed in Providencia, Proteus, Morganella, and Escherichia. Except for Enterococcus, genes encoding resistance to sulfonamides (sul1 and sul2) were observed in all the species. Enterococcus on the other hand, showed resistance to vancomycin (van genes) (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Comparative analysis of the genomes from sewage pathogens and those from the global clinical isolates revealed notable similarities (Supplementary Data S9a–j). The ESBL blaCTX-M-15 was the most prevalent allele of the blaCTX-M genes in Escherichia, Klebsiella and Morganella in the sewage as well as clinical isolates. While blaNDM-5 was the most prevalent allele of metallo- beta-lactamase in Escherichia in clinical cases and wastewater, blaNDM-1 was the most prevalent allele in Klebsiella and Morganella from clinics and wastewater. The cephalosporin resistant blaDHA-20 was quite prevalent in the clinical and sewage Morganella isolates. However, blaDHA-1 was almost equally prevalent in wastewater, this was not as frequently observed in the clinical cases. Likewise, the blaDHA-17 that was the most prevalent beta-lactamase in the Morganella isolates from clinics, this allele was completely absent in the Morganella from wastewater. Strikingly, the prevalence of strA and strB genes in the sewage samples were identified to be 50% more as compared to the clinical samples. While vanA was the prevalent gene responsible for vancomycin resistance in the global isolates followed by vanB gene, the Indian clinical isolates exclusively had only vanA gene. Interestingly, this was also reflected in the sewage isolates and they only carried the vanA gene.

Genetic linkage of antibiotic resistance genes with mobile genetic elements

Many of these ARGs were found to be associated with MGEs such as, transposons, insertion sequences (IS), and miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs). A total of 187 out of 305 genomes showed the association of one or more ARGs with MGEs and IS elements were identified to be the most abundant (Fig. 10a). The species with most number of isolates having ARGs linked with either IS elements or transposons are E. coli (n = 61/69), followed by K. pneumoniae (n = 25/33), M. morganii (n = 20/33), P. mirabilis (n = 14/25), A. baumannii (n = 07/08) and P. putida (n = 06/06). The IS6100 was the predominant IS element found in the study isolates. The most common ARGs that were linked with MGEs are aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, ant(3”)-IIa, the dfr genes and the sul genes (Supplementary Data S10j). While in most of the cases the MGEs linked with these ARGs were different across the species, some ARGs were linked with the same MGE across the species. For example, Tn7 is associated with ant(3”)-IIa and dfrA1 in P. mirabilis and M. morganii and blaCTX-M-15 is linked with ISEc9 in E. coli, K. pneumoniae and M. morganii implying inter-species movement of the ARGs by MGEs. In a few isolates of E. coli and M. morganii, the chloramphenicol resistance genes (catI and catB3) were linked with Tn6196. In E. coli, ARGs such as mphA, sul1, blaDHA-1, qnrB4, aadA5 and the dfr genes were associated with IS6100 but in P. putida, IS6100 is associated with mphE, msrE, aph(3”)-Ib and aph(6)-Id. In majority of E. coli isolates that showed linkage of strA, strB and blaTEM-1 with a MGE, the MGE has been IS1133 and/or IS5075 but in A. baumannii, the MGE associated with these two AMEs is ISvsa3. The Gram-positive Enterococcus harbored a completely different set of IS elements and transposons as compared to the Gram-negative species (Fig. 10a).

a Sankey diagram shows the ARGs associated with the MGEs in different organisms from the sewage. Most ARGs are associated with the IS6100 element in different organisms. E. coli has the highest number of ARGs associated with MGEs. b Sankey diagram shows the ARGs in different sewage isolates that are linked with plasmid genes. The Inc plasmids are the most prevalent. c Chord diagram shows the ARGs in different organisms that are found within integrons. The thickness of the lines (connections) indicates the prevalence of that association.

Further, these isolates were screened for the presence of acquired plasmids through the PlasmidFinder database. The database identified the presence of acquired plasmid genes in Klebsiella, Escherichia, Proteus, Enterobacter, Citrobacter and Enterococcus (Supplementary Data S10k). However, very few isolates showed the presence of ARGs in these plasmids. The beta-lactamase genes blaOXA-181, blaOXA-232, blaOXA-484, and blaCTX-M-15 were associated with the ColKP3 plasmid in E. coli which also harbored many Inc plasmids that carried AMEs such as aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id and aph(3’)-Ia. Apart from E. coli, a few isolates of Klebsiella, Citrobacter and Enterococcus showed the presence of ARGs with plasmids. Other ARGs carried on Inc plasmids were sul2, tetA, blaCMY-59, and blaTEM-1 (Fig. 10b). IntegronFinder identified integrons in all the species. In many isolates of Acinetobacter, Aeromonas, Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Escherichia, Klebsiella, Morganella, Proteus, Providencia, and Pseudomonas, ARGs were located within these integrons (Supplementary Data S10). Most of these ARGs encoded AMEs such as aadA2 and ant(3”)-IIa, trimethoprim-resistance dfr genes, and the rifamycin-resistance arr-2 gene (Fig. 10c).

Discussion

Sewage represents a critical hotspot for bacterial HGT which serves as a valuable proxy for monitoring the diversity of AMR and identifying resistant pathogens associated with both human and animal populations14. Wastewater surveillance of pathogens has emerged as a cutting-edge strategy for monitoring public and environmental health, driven by factors such as exposure to surface runoff, human and animal interactions, and the discharge of untreated effluents15. Previously, the MDR bacteria confined to frail and debilitated hospital patients, are now spreading in communities posing a growing threat to public health. Analysing wastewater systems helps in identifying circulating resistant bacteria and track emerging resistance trends, providing an early warning system for potential outbreaks. In this study, we have investigated the AMR spectrum of open drainage systems using both culture-dependent and culture-independent metagenomic approaches. Sewage samples were collected from six states across India, viz. Assam, Haryana, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and West Bengal and constituting the first large-scale integrated multifaceted study of urban sewage samples. Faridabad (Haryana) was chosen for longitudinal sampling due to multiple reasons like its large population exceeding 1.4 million, and status as a key industrial hub within the National Capital Region of India. The city encompasses a diverse range of wastewater sources, including densely populated urban areas, rapidly expanding peri-urban zones, community sewage, and hospital effluents, many of which lack adequate treatment infrastructure. Furthermore, several sewage sites are connected to the Yamuna River, a critical tributary of the Ganges, which amplifies the potential environmental and public health implications due to downstream contamination risks. Despite its relevance, Faridabad remains underrepresented in AMR surveillance, particularly in environmental studies.

Given the complex sewage landscape of Faridabad and its underrepresentation in environmental AMR studies, assessing the occurrence and distribution of antibiotics in its wastewater provides critical insights into the pharmaceutical burden and potential resistance reservoirs in such urban ecosystems. Antibiotics are widely prescribed and commonly enter the environment through improper drug disposal, excreted waste or municipal dumpsites containing human or animal pharmaceutical waste16. In the present study, a suite of eleven clinically important antibiotics spanning multiple pharmacological classes, namely beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, quinolones, macrolides, tetracyclines, rifamycins, and polymyxins were analysed in sewage water samples to assess their environmental prevalence. Among the compounds investigated, kanamycin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic, demonstrated the highest detection frequency, being present in 66.6% of the samples. Its concentrations consistently exceeded the limit of quantification (LOQ), ranging from 2.064 to 4.809 ng/mL. This high detection frequency and quantifiable presence suggest widespread use and possible persistence of the compound in the wastewater system. Azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic, was the second most frequently detected compound, identified in 55.8% of the samples with a maximum concentration reaching up to 5.149 ng/mL. The frequent occurrence of azithromycin may be attributed to its high prescription rates and known environmental persistence. Spectinomycin (50%; 1.004–18.711 ng/mL) and amoxicillin (45.1%; 0.416–10.525 ng/mL) were also frequently detected, reflecting their widespread and extensive clinical and veterinary applications, as well as their persistence in wastewater. In contrast, the occurrence of erythromycin, tetracycline, nalidixic acid and rifampicin were relatively less, being detected in fewer than 15% of the analysed samples. The observed variation in antibiotic concentrations may be attributed to factors influencing their persistence and distribution, such as antibiotic class, molecular weight, and chemical stability. Our analysis demonstrated the widespread presence of clinically significant antibiotics with amoxicillin and spectinomycin showing particularly high concentrations along with tetracycline, although it occurred less frequently. The detection frequency and concentration of antibiotics observed in wastewater could be influenced by the site-specific factors, and seasonal variation in sampling17. In India, previous studies have investigated the occurrence and distribution of antibiotics across various aquatic systems and consistently reported the presence of amoxicillin, azithromycin, erythromycin, and fluoroquinolones17,18,19,20. Consistent with previous reports, azithromycin (55.8%) and amoxicillin (45.1%) were among the most frequently detected antibiotics in the current study, reflecting their widespread usage and persistence in the environment. Notably, our findings also revealed elevated detection frequencies of aminoglycosides (ranging from 50 to 66.6%), a class of antibiotics that has been infrequently reported in prior wastewater studies from India. This observation provides novel insight into the regional antibiotic contamination profile, suggesting a potentially underrecognized contribution of aminoglycosides to the overall antimicrobial burden in Indian wastewater systems. Also, in our study, ampicillin and polymyxins were not detected which may be due to comparatively lower usage or enhanced degradation, and instability under environmental conditions. The concentration of antibiotics and their detection frequency in aquatic environments such as river, lakes, ponds and sewage systems is highly dynamic and influenced by various factors such as seasonal variation, population density, antibiotic usage patterns and waste management practices. In a geographically diverse country like India, the variability in antibiotic usage across regions contributes to antibiotic contamination profiles in different water bodies. Globally, several studies have reported the occurrence of antibiotics in sewage, including ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, and cefalexin prevalent in Europe, sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim in Africa, and elevated levels of fluoroquinolones in Asia21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Thus, this study provides a broader perspective by systematically analysing antibiotic contamination patterns in wastewater across different regions of India while drawing insights from global status. The integration of regional and international data highlights unique and variable trend in antibiotic occurrence and distribution, which emphasize the need for continuous surveillance of antibiotic residues in Indian wastewater. Such evidence-based monitoring can support strategic planning and targeted mitigation measures, in alignment with global AMR monitoring initiatives.

In the current study, the elevated concentrations of different antibiotic residues indicate that the presence of antibiotics in wastewater may exert selective environmental pressure, potentially accelerating the persistence, emergence, and dissemination of associated ARGs from environment to other settings. Macrolide antibiotics and the genes encoding macrolide resistance mphA and ermB, were consistently detected in the majority of the sewage samples through LC-MS/MS and dipstick assay, respectively underscoring the escalating threat of macrolide resistance. This finding aligns with the recent study form South India, where macrolides and aminoglycosides contributed significantly to resistance profiles10. Notably, despite high tetracycline residues, the dipstick assay showed low tetB prevalence, likely due to dominance of other tet genes as revealed by metagenomics.

Shanmugakani et al. developed a dipstick assay for rapid detection of carbapenemase genes from stool specimen28. However, in our study, we developed four multiplex dipstick assay panels, each enabling simultaneous detection of four resistance genes, allowing rapid and comprehensive screening of ARGs. Our dipstick results showed concordance with shotgun sequencing, with sensitivities ranging from 72% to >95%. The highest sensitivity was observed for dfrA1, blaKPC and sul1 alleles (>95%), whereas qnrS and sul2 showed relatively lower sensitivity (approx. 72%). In certain instances, the dipstick assay detected resistance genes that were not identified through shotgun sequencing, reflecting its higher analytical sensitivity for low-abundance ARGs that fall below sequencing threshold especially at limited sequencing depths. Conversely, in a few samples, shotgun sequencing identified resistance genes such as oqxA that were not captured by the dipstick assay, likely due to sequence variations or mutations in target regions that affect probe binding efficiency in the dipstick format. Despite occasional discordance, the dipstick assay demonstrated strong potential as a cost-effective, rapid, and field-deployable tool for ARG surveillance. Incorporating probes based on pilot metagenomic data can enhance detection sensitivity. While limitations such as semi-quantitative outputs and potential false negatives exist, the assay complements sequencing approaches by enabling early detection and routine monitoring of ARGs and pathogens in both clinical and environmental settings, particularly in resource-limited contexts28.

The longitudinal analysis of sewage microbiomes in Faridabad from June to December 2023 revealed significant temporal shifts in microbial community composition. PCoA results demonstrated distinct clustering by month (R² = 0.213, p = 0.001), with September and late-year samples (November-December) showing the most divergent community structures. Alpha diversity metrics (Observed richness, Shannon, Simpson indices) peaked mid-year (June-August) and declined toward year-end, indicating seasonal fluctuations in microbial richness and evenness. Specific taxa displayed notable temporal dynamics, A. veronii and T. flocculiformis decreased mid-year before rising again in winter; Bifidobacterium species and S. equinus peaked in early autumn but declined later; P. lundensis emerged only in November–December. Community sewage samples consistently harbored higher diversity than hospital samples, with clear month-wise distinctions in microbiome profiles (p = 0.001). Comparisons across Indian states sampled in December showed geographic variation despite synchronized sampling, with taxa like A. cryaerophilus prevalent in northern states and others enriched regionally. These findings underscore the combined effects of temporal, spatial, and source-specific factors shaping sewage microbiomes, reflecting underlying environmental and anthropogenic influences. A large number of taxa, representing a wide phylogenetic span, was uncovered from the sewage samples from community and hospital settings. Interestingly, we identified notable differences in how spatiotemporal variation affected certain bacterial taxa. These variations suggest that specific bacterial groups respond differently to seasonal changes, which may influence their abundance, diversity, or pathogen dynamics in different environments29,30,31.

Our finding is consistent with previous research that highlights the prominence of beta-lactam resistance in both clinical and environmental contexts32. Research by Li et al., highlighted the role of the efflux pumps in both clinical and environmental bacterial isolates, reinforcing efflux mechanisms as a key factor in the resistance landscape33. Our sequencing based identification of 66 efflux pump genes supports previous studies highlighting efflux pumps as a key mechanism of resistance in bacteria. The varying abundances of ARGs between the community and hospital settings could reflect differences in antibiotic usage patterns. Kraemer et al. had previously discussed how hospitals typically have higher selective pressures due to intensive antibiotic use, leading to enriched resistance profiles in their effluents34. Our findings indicate a significant overlap between sewage and clinical isolates, underscoring the potential role of wastewater environments as reservoirs for drug-resistant bacteria. Similar findings have been reported by others that highlight the presence of clinically relevant strains in environmental sources32,35.

The diversity within E. coli isolates, with 22 different sequence types (STs), suggests that sewage harbors significant genetic variation indicating the genetic diversity of MDR E. coli in the study population. Furthermore, the prevalence of K. pneumoniae STs (ST15, ST37, and ST16) in sewage is mirrored by their prevalence in clinical cases across America and Asia indicating a shared lineage that likely facilitates transmission of these strains among clinical and environmental settings. This underscores the critical role of specific STs in the global epidemiology of antibiotic resistance, with these lineages being implicated in major outbreaks worldwide36,37.

The widespread presence of ARGs across species highlights the growing threat of XDR pathogens, with prominent challenge of beta-lactam resistance driven by blaTEM, blaNDM, and blaOXA genes which is in consistence with global data32,38. The current study observed differences in ARG profiles among genera, suggesting diverse selective pressure in environment and clinical settings, revealing potential gaps in resistance mechanisms for targeted intervention39.

Furthermore, many of these AMR genes were associated with MGEs and the finding that certain ARGs, such as aph(3”)-Ib and blaCTX-M-15, are linked with the same MGE across different species implies a significant inter-species transfer of resistance traits, further complicating the landscape of AMR. These findings are consistent with studies demonstrating that MGEs such as insertion sequences, transposons and integrons are critical for the evolution of MDR bacteria40,41. However, the specific association of resistance genes with distinct MGEs, such as IS1133 and IS5075 in E. coli or ISvsa3 in A. baumannii, suggests species-specific adaptation strategies that may influence the effectiveness of treatment options.

Our findings indicate that the vanA gene is the dominant driver of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) in India, consistent with global reports42,43. In contrast, vanB isolates were less common compared to global data, suggesting geographical or environmental factors influence resistance patterns. Notably, resistance genes like blaDHA-20 in Morganella and strA and strB for aminoglycoside resistance were more prevalent in sewage isolates than in clinical samples, highlighting a significant environmental reservoir.

A comprehensive understanding of the abundance, diversity, and distribution of AMR genes, along with the factors that influence their spread, is essential for accurately assessing risks and developing effective strategies to combat antibiotic resistance. Thus, the strategic integration of multi-pronged approaches in this study including QTRAP mass spectrometry for the detection and precise quantification of antibiotic residues, dipstick-based assay for rapid ARGs identification, 16 s metagenomic sequencing to characterize microbial community diversity, along with the shotgun and whole genome sequencing for resistome profiling established a robust and holistic framework for accurately assessing the prevalence, diversity, and complexity of AMR in sewage water.

This study provides valuable insights into the contamination of antibiotics, microbial diversity, and ARGs richness across sewage samples collected from six Indian states between June and December 2023. However, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sampling period of seven months limits the ability to capture seasonal variations in antibiotic concentrations, microbial community structure, and ARG dynamics. Continuous or year-round monitoring would be essential to better understand temporal trends and the potential influence of climatic or anthropogenic factors on resistance patterns. Second, the geographical scope of the study, though covering multiple states, does not represent the entire diversity of environmental, socio-economic, and infrastructural contexts present across India. Expanding surveillance to additional regions, including rural and under-sampled urban areas, would provide a more comprehensive national perspective on AMR dissemination pathways.

In conclusion, this study highlights the role of sewage as a significant reservoir for MDR and XDR pathogens, facilitating the transfer of ARGs into the clinically important bacterial pathogens. The findings underscore the influence of antibiotic residues and MGEs in promoting HGT, which fosters bacterial adaptability and resistance. Furthermore, the dipstick-based assay developed in this research provides a rapid, cost-effective, and specific tool for sewage surveillance, allowing for timely and targeted interventions. The shared MDR lineages and resistant alleles between clinical and environmental settings emphasize the interconnection of these environments and reinforce the necessity of a One Health approach. In light of these insights, the study advocates for the implementation of nationwide sewage monitoring programs and the development of region-specific strategies for outbreak preparedness. Tailoring antibiotic use policies to the unique conditions of each region, rather than relying on generic guidelines, will be essential in mitigating the growing threat of antibiotic resistance.

Method

Sewage sampling and measurement of antibiotic concentration using QTRAP mass spectrometer

Wastewater samples (n = 332) were collected from seven different sites across Faridabad, Haryana (North India) including both hospital (n = 82) and community sewage outlets (n = 250) for a duration of seven months from June 2023 to December 2023. Apart from Faridabad, samples (n = 49) were also collected from other parts of India including Assam (North-eastern state), West Bengal & Jharkhand (Eastern states of India), Uttar Pradesh, and Uttarakhand (Northern states of India) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Wastewater samples were collected from publicly accessible sites, and the local authorities were informed prior to sampling. The details of all the sampling sites along with the geographical locations and coordinates are provided in the Supplementary Data S11. The untreated wastewater samples were collected in sterile bottles by grab sampling method during morning hours and immediately transported to the Functional Genomics Laboratory, THSTI, Faridabad, India on ice for further processing44. On reaching the laboratory, the collected 200 ml sample was mixed thoroughly and 30 ml from it was collected in 50 ml sterile falcons and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then filtered through a 0.22 µm Millex GV syringe filter (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and stored at −80 °C for subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis to detect antibiotic residues in sewage water45. Further, the pellet was carefully resuspended in 1.5 ml nuclease free water and 100 µl were inoculated in culture broths and incubated both aerobically and anaerobically for culturomics study. From the remaining 1.3 ml sample, 1 ml was used for metagenomic nucleic acid extraction and subsequent 16S metagenomic sequencing, dipstick assay and shotgun sequencing.

The Sciex Exion LC system paired with the QTRAP 6500 + MS was used for LC-MS/MS analysis of antibiotic residues in sewage water. Samples were filtered through a 0.22 µm Millex GV syringe filter (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) before analysis. Separation was performed on an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column at 40 °C with a gradient elution of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B), ramping B from 15 to 90% in six minutes at 0.2 mL/min. For electrospray ionization, electrospray voltage used was +5500 V, with a source temperature of 500 °C. Transition ranges were determined by initially injecting each commercially purchased pure antibiotic into the LC-MS/MS. One transition per antibiotic with the sharpest peaks was selected for identification purposes and ANALYST 1.7.2 software was used for data analysis46. The method performance characteristics, including the linearity, LOD, LOQ, and coefficient of correlation (R2) were evaluated. Standard calibration curves were obtained using eight different concentrations of each antibiotic across the linear range and was considered acceptable if the coefficient of correlation was more than 0.98 (Supplementary Data S1)47. The LOD and LOQ values, for all the eleven antibiotics, were determined as the concentrations corresponding to signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios of 3:1 and 10:1, respectively18,48.

Isolation of sewage metagenomic DNA and screening of antibiotic resistance genes by dipstick molecular assay

Metagenomic DNA was extracted from sewage samples using the THSTI DNA extraction method49 which includes a series of chemical, physical and mechanical actions to disrupt the cells and release the genomic DNA. The precipitated genomic DNA was washed and resuspended in nuclease-free water followed by resolving the sample in 0.8% agarose and purity check using the Nanodrop One Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wisconsin, USA) (Supplementary Data S4b).

Purified metagenomic DNA was used as a template to detect the presence and prevalence of ARGs in sewage water. Sixteen emerging resistance determinants (Supplementary Data S2) representing different drug classes commonly used in hospital settings or are highly prevalent among bacterial pathogens, were selected for dipstick based detection analysis. Oligonucleotides were initially validated in silico using Clone Manager (Sci-Ed Software), NCBI BLAST and Primer-BLAST to ensure target specificity and to exclude significant cross-hybridization with non-target sequences. Parameters such as secondary structure, primer-dimer formation, and melting temperature compatibility were also evaluated prior to in-vitro testing. Candidate primers were then validated in singleplex and multiplex PCR, and representative amplicons were confirmed by Sanger sequencing to ensure specificity. For dipstick assay, either the forward or reverse primer of each validated set is labeled with a single-stranded tag-linker sequence, complimentary to its respective probe imprinted on the dipstick for hybridization, while the paired primer was labeled with biotin to enable binding with streptavidin-coated latex beads (Tohoku Bio-array, Sendai, Japan). Subsequently, the tagged and biotinylated oligos were used to standardize the multiplex PCR assays for dipstick analysis. Standardized m-PCR assays were translated into C-PAS (4) dipstick test strips (TBA Co., Ltd, Sendai, Japan), in which diluted amplicons were combined with developing solutions containing streptavidin-coated blue-colored latex beads. Immersion of the dipstick in the resulting solution generates a blue color line, indicating the detection of target genes.

16S rRNA gene and shotgun sequencing of sewage metagenome

The metagenomic DNA of the microbiome was amplified for the targeted metagenomics of the 16S rRNA specific V3 to V4 region. The nucleoside nomenclature of the overhang (shown in italics) holding primers for targeting the amplification sites are: Forward Primer: 5’TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG3’, Reverse Primer: 5’GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC3’. The amplicons were cleaned up with the Agencourt AMPure XP paramagnetic beads (Beckman Coulter). Samples were subjected for the library preparation with the Nextera XT Index Kit V2 (Illumina, California, US). The cleaned-up libraries were quantified with Qubit Flex Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, US) and verified for quality analysis with Tape Station 4200 (Agilent, California, US) automated electrophoresis system. Qualified libraries have been normalized to 4 nM concentration and a final concentration of 700pM pooled library was sequenced in the Nextseq 2000 sequencing platform (Illumina, California, US) with paired end 2 × 300 cycle chemistry.

For the shotgun sequencing the metagenomic DNA samples were quantified with the Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kits and HS Assay kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, US) in the Qubit Flex Fluorometer. A good quantity of samples with 300 ng were tagmented to short fragments using the bead-linked transposome (Illumina, California, US). The library was prepared using the washed fragments with the Illumina DNA prep kit and IDT-Illumina DNA/RNA UD indexes (Illumina, California, US). The library was cleaned up following left-side and right-side size selection double clean up method with the Agencourt AMPure XP paramagnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, California, US) and the library quantity was determined. The TapeStation 4200 (Agilent, California, US) has been used to check the bell-shaped curve formation in the electropherograms of the libraries. Presence of any impurities was cleaned up using the SPRIselect beads (Beckman Coulter, California, US). The libraries were normalized to 4 nM concentration and pooled for sequencing at a final concentration of 750 pM in the Nextseq2000 sequencing platform (Illumina, California, US). The sequencing chemistry used the paired end 2 × 150 cycles chemistry in the P2 flow cell (Illumina, California, US) and the data generated for 16 s metagenome & shotgun data has been submitted to NCBI database (Bioproject ID: PRJEB81436).

Analysis of bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance genes in the sewage metagenome

Demultiplexed FASTQ files for Read 1 (R1.fastq) and Read 2 (R2.fastq) of each sample were subjected to initial quality control based on the Fastp (version 0.20.1) reports generated. The trimmed reads were processed using DADA2 package50 (Version 1.16) in R (Version 4.4.1) to generate amplicon sequence variant (ASV) generation. For species-level classification, the NCBI 16S Microbial database was used with blaSTn for alignment51. Only representative sequences with >98% sequence identity in BLAST were selected for species-level annotation. For shotgun data, raw reads were processed and trimmed and the resulting reads were subsequently aligned to the human reference database (GRCh38) using HISAT2. The reads that remained unaligned after HISAT2 were concurrently subjected to taxonomic classification using Kraken252 and assembled with SPAdes (version 3.13.0) in meta mode53. Bacterial reads were extracted selectively via a custom bash script after Kraken2. The bacterial diversity within the sewage metagenome was assessed using the phyloseq package in R. Metagenome binning for each sample was carried out with MetaBAT254. Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) were screened for ARGs using the abricate tool with the CARD database, applying default settings (>80% identity, >80% coverage). The contigs with CARD hits were taxonomically classified with Kraken 2, and taxa were evaluated from species to phylum levels. The contigs/scaffolds that met the following criteria were selected for network analysis of bacteria and ARGs: (1) classified as belonging to the superkingdom Bacteria by Kraken 2, (2) contained an ARG as identified by the CARD tool, and (3) had a Kraken 2 taxonomic classification at the species level. Bacteria and ARG nodes connected in the network were visualized using Cytoscape. Additionally, the MAGs were queried against KEGG Orthology (KO) IDs, Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG), and Gene Ontology (GO) using EggNOG-mapper, with parameters set for >90% identity and >80% coverage55.

Isolation, identification and cultivation of drug-resistant aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacterial species

The sample resuspended in enriched medium, was inoculated into Mueller-Hinton and Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth, under selective pressure from five different antibiotics: ampicillin (100 µg/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml), nalidixic acid (10 µg/ml), azithromycin (15 µg/ml), and tetracycline (10 µg/ml). Samples demonstrating optimal growth were subsequently processed for culturomics analysis. This involved further culturing on MacConkey and BHI agar to isolate both aerobic and anaerobic organisms. Isolates were identified using 16S rRNA gene Sanger sequencing, and the results were analysed using NCBI database.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacterial isolates

The susceptibility profiles of a total of 681 aerobic and facultative anaerobic isolates were assessed using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method against a panel of 32 commercially available antibiotic discs. The interpretation of results adhered to the latest guidelines from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST)56,57. Reference strains, including E. coli ATCC 25922, A. baumannii ATCC 17978, and K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, were employed to ensure the accuracy of the experiments. The specific details on antibiotic concentrations and bacterial isolates tested are provided in the Supplementary Data S7.

Whole genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

The bacterial isolates confirmed with the Sanger sequencing (Applied Biosystems Genetic Analyzer 3500) were subjected for the whole genome sequencing (WGS). Library preparation involved tagmentation with in vitro transposition resulting DNA fragments. The transposed fragments readily bind to the index adapters (Nextera XT Index kit V2, Illumina). After indexing, the library pool was sequenced at 750 pM following the shotgun sequencing protocol. The raw files were processed using the seqtk tool v1.3-r106 and then merged using PEAR (Paired-End read merger) software. The SPAdes pipeline was employed to assemble the genome from the cleaned paired-end reads53. The quality of the assembled genomes was evaluated using CheckM (version v1.1.3)58. Only genomes meeting the criteria of >90% completeness and <5% contamination were included for subsystem analysis. Annotation was carried out using PROKKA v1.14.6. The whole genome sequences of the bacterial isolates are submitted to the NCBI database (Bioproject ID: PRJEB81436).

Multilocus sequence typing

The sequence type (ST) of the genomes was identified using the MLST finder (https://github.com/tseemann/mlst). The Achtman scheme was used for E. coli (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, recA), the Pasteur scheme was used for A. baumannii (cpn60, fusA, gltA, pyrG, recA, rplB, rpoB) and the PubMLST scheme was used for K. pneumoniae (phoE, mdh, tonB, gapA, rpoB, pgi, infB), P. aeruginosa (acsA, areE, guaA, mutL, nuoD, ppsA, trpE) and E. faecium (adk, atpA, ddl, gdh, gyd, pstS, purK)59.

Phylogenetic analysis