Abstract

For decades, semiconductors and their heterostructures have underpinned both fundamental and applied research across all areas of electronics. Two-dimensional, 2D (atomically thin) semiconductors have now the potential to push further the miniaturization of electronic components, enabling the development of more efficient electronics. Here, we report on a large tunneling magnetoresistance of 1100% at a bias current of 1 nA and a giant anomalous zero-bias spin voltage effect in magnetic tunnel junctions based on 2D materials. The generation, manipulation and detection of electron spin across a nanometer-thick magnetic tunnel junction do not require any applied bias. The large zero-bias spin voltage signal exceeds 30,000%, which is far greater than the highest magnetoresistance signals reported to date. This non-equilibrium spin-engine state arises from the asymmetric diffusion of spin-up/spin-down electrons across the junction. It is driven by the built-in electric field of the junction and occurs under continuous energy exchange of the junction with the environment. Our findings reveal unexplored opportunities to transform and amplify spin information for low-power electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The success of charge-based applications in semiconductor heterostructures1 suggests intriguing opportunities to combine spin and charge degrees of freedom in spintronics2,3. To date, key progress in spintronics have focused on spin valves, including magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs) with metallic ferromagnets. The resistance of these junctions varies with the relative magnetization orientation of the two ferromagnets2,3,4,5,6. While metallic spin valves remain valuable for magnetically storing and sensing information, they are of limited use for transferring and processing information, where semiconductors excel. Typically, there are two ways to integrate spin with the versatile charge control in semiconductors: chemical doping and spin injection2,3,7,8. Adding magnetic impurities to common semiconductors comes at a high cost: the carrier mobility is drastically reduced and robust emission of light is lost. Alternatively, heterostructures combining common ferromagnets and semiconductors encounter different challenges: spin injection from a ferromagnet into a semiconductor can be strongly suppressed by the interface quality and the resistance mismatch between the materials2,3. Although these problems can be alleviated by inserting a tunnel barrier2,3, the current flow is impeded, requiring a larger applied bias and increased power consumption.

Building on advances in van der Waals (vdW) layered materials and vdW heterostructures9,10, including a growing number of two-dimensional (2D) magnets11,12, here we demonstrate a different platform to overcome these obstacles in spintronics. A hallmark of vdW layered materials is their strong covalent atomic bonding within the 2D planes and weak vdW bonding between the layers. This allows for the fabrication of stable thin films down to the monolayer level10, avoiding interface and crystal defects that are detrimental for spin transport in covalently-bonded magnetic multilayers13. As vdW bonding supports atomically-sharp interfaces between dissimilar materials, the same platform can also be suitable for atomically-thin electronic and photonic devices, relying on high-quality metal/semiconductor contacts14,15,16. Here, we report on a large tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) and a giant anomalous zero-bias spin voltage effect (SVE) in MTJs based on 2D magnet and semiconductor p-n junctions. Without applying an external bias, the generation, manipulation and detection of electron spin across a nanometer-thick MTJs are achieved by exploiting high quality ferromagnetic/semiconductor interfaces and semiconductor p-n junctions. To analyze the origin of the zero-bias SVE, we conducted a series of control studies: 1) The zero-bias SVE is not observed in MTJ devices with a single spacer layer, excluding noise from the measurement setup and 2) does not originate from the spin Seebeck effect, as confirmed by experiments with a temperature gradient along the junction; 3) a semiclassical model of the spin-dependent drift-diffusion combined with first-principles density functional theory (DFT) of the junction reveals a non-equilibrium spin-engine state. This features the injection of electron spins at the Fe3GeTe2/GaSe interface, their diffusion under the built-in electric field of the junction and their spin flipping at the InSe/Fe3GeTe2 interface.

Results

For our vdW heterostructures, as depicted in Fig. 1a, we select the layered ferromagnetic metal Fe3GeTe2 (FGT) owing to its desirable large coercivity, strong perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, and relatively high Curie temperature, Tc of up to 220 K17,18. Unlike common spin valves, where two ferromagnets are separated by a single nonmagnetic region2,3,19, here we employ a vdW p-GaSe/n-InSe heterostructure composed of materials with different doping and composition. The vdW heterostructure is assembled by stacking 2D materials (FGT, γ-InSe, and ɛ-GaSe) exfoliated from bulk crystals (see Methods for details). The optical image of a typical device is shown in Fig. 1b, where the contours of different nanoflakes are outlined by dotted lines of different colors. Figure 1c shows the cross-sectional high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image for a typical device structure. The HRTEM and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (Figure S1 in Supplementary Information) confirm atomically-sharp interfaces without contamination or amorphous oxide. We fabricated three MTJ devices with varying barrier layer thicknesses, where the barrier layers are 5-nm-GaSe/5-nm-InSe (device A), 10-nm-GaSe/5-nm-InSe (device B), and 15-nm-GaSe/5-nm-InSe (device C). The current-voltage (I-V) characteristic curves of these devices were measured, as shown in Fig. 1d. As the total thickness of the barrier layer increases, the I-V curves of the devices change from a nearly symmetrical, ohmic response to an increasingly asymmetrical, rectifying behavior.

a Schematic of the structure with source and drain contacts to the FGT layers and applied perpendicular magnetic field, B. b An optical image of a typical device. c Cross-sectional HRTEM image. d I-V curves in the parallel magnetization alignment for devices A, B, and C. e, f V-B curves under bias current of 1 nA for devices A, B, and C show a TMR of ~1100%, 10%, and 0, respectively, at 10 K. g, h V-B curves without external applied voltage for devices A, B, and C show a zero-bias anomalous SVE of ~1930%, 30%, and 0, respectively, at 10 K. i, The zero-bias anomalous SVE as a function of the resistance-area product at 10 K for different devices labelled A, B, C, D, E, F.

Similar to conventional spin-valve devices, passing a charge current I through the FGT/p-GaSe/n-InSe/FGT vdW heterostructure under a magnetic field B perpendicular to the layers leads to a tunnel magnetoresistance, TMR = |(RAP−RP)/RP|, where RAP (RP) is the resistance for the antiparallel (parallel) configuration of the magnetization in the two FGTs. However, the inclusion of the vdW p-n junction leads to significant differences in the measured spin-voltage effect

where VAP (VP) is the voltage for antiparallel (parallel) configuration. At a finite current I, the SVE coincides with the TMR for devices with symmetric linear I-V since VAP, P/I = RAP, P. Figure 1e and 1f, respectively, present the TMR of devices A, B, and C measured under a fixed bias current of 1 nA. As the barrier layer thickness increases, the TMR ratio decreases from a very large value of ~1100% in device A to 10% in device B, and eventually vanishes in device C. The TMR observed in device A is significantly higher than that in other similar 2D material-based MTJs. The origin of such a large TMR can be attributed to two factors: on the one hand, the two connected Brillouin zone filtering effect induced by the p-n tunnel junctions, where one spin conduction channel is selectively enhanced while the other is suppressed; on the other hand, the built-in electric field in the p-n junction induces a novel spin-dependent electric potential, which gives rise to the zero-bias SVE observed in our experiment. Remarkably, we observe a giant and reproducible zero-bias SVE across the p-n junction in the absence of any bias current. As shown in Fig. 1g, h, the SVE for device A reaches a value of ~1930% at 10 K and decreases to 30% in device B and disappears in device C. The V-B curves exhibit typical SVE with two states. Upon sweeping B from negative to positive values, a sharp jump to the high-voltage state occurs at B ~ 0.15 T corresponding to the AP configuration ↓↑ or ↑↓, where the arrows denote the out-of-plane FGT magnetization. At B ~ 0.21 T, a sharp jump to the low-voltage state corresponds to the P configuration ↓↓ or ↑↑. The voltage jumps are also observed for B < 0. The zero-bias SVE of several devices is summarized in Fig. 1i. As the resistance-area product increases, the zero-bias SVE decreases exponentially and disappears, indicating that it is dominated by the spin tunneling mechanism.

While a spin signal between two ferromagnets typically increase as their separation decreases2,3, we observe the opposite behavior when we replace the p-n junction with individual thinner p- or n-type layers. Both TMR and SVE are significantly enhanced in the 10-nm-thick p-n junction compared to devices with a nonmagnetic region of either 5-nm-thick p-GaSe or n-InSe layers. For devices based on thin individual p- or n-doped vdW regions, there is no zero-bias SVE (SVE = 0 at I = 0). Even under I = 1 nA, the TMR for p-GaSe ( ~ 85%)20 and n-InSe ( ~ 41%)21 is significantly smaller than that for the p-GaSe/n-InSe junction (Supplementary Note 1 and Fig. S2). This dependence of the spin signal on the thickness of the spacer suggests that our observations do not arise from proximity effects, as proposed in other vdW spin valves19. Thus, the data from different device structures suggest that the observation of the anomalous zero-bias SVE requires a thin p-n junction sandwiched between two FGT electrodes.

We now focus on the temperature- and current-dependent behavior of these devices. As shown in Fig. 2a for device A, clear V-B hysteresis loops without any applied bias current are observed up to the Curie temperature of FGT, Tc = 220 K. The measured widths of the voltage jumps for the antiparallel magnetic configurations of the FGT electrodes (↓↑ or ↑↓) change non-monotonically with increasing T. This is ascribed to the different T-dependence of the coercive field in the two FGT layers22. Figure 2b shows the value of VAP and VP in the zero-bias state as a function of T extracted from the V-B curves: unlike the monotonic decrease of VAP with T, most likely related to the T-dependence of the spin-injection efficiency, the value of VP varies non-linearly with T and changes sign twice. This gives rise to a large SVE and singularities in the SVE versus T plot. The corresponding T-dependence of the magnitude of the zero-bias spin voltage is shown in Fig. 2c. It can be seen that the zero-bias SVE reaches a maximum value of 32,230% at T = 35 K. The SVE has excellent stability and the corresponding V-B loop at T = 35 K is presented in Supplementary Fig. S3. The non-monotonic temperature dependence of the SVE suggests that, in addition to the properties of the FGT, other mechanisms need to be considered, such as the magnitude and direction of the spin polarization at the FGT/InSe and FGT/GaSe interfaces, and the spin transport along the p-n junction. We also extracted the temperature dependence of the spin accumulation voltage ΔV (ΔV = VAP - VP), as shown in Fig. 2c (red squares), and confirmed a clear trend: ΔV gradually decreases with increasing temperature and drops to zero when the temperature approaches 230 K. This trend directly confirms the intrinsic spin-dependent origin of the SVE: above FGT’s Curie temperature, FGT loses its ferromagnetic order, and electron spin polarization diminishes to zero. Consequently, the spin-dependent voltage difference between the parallel and antiparallel states vanishes (ΔV = 0), resulting in SVE = 0. This behavior stands in contrast to extrinsic effects (e.g., thermal noise), which would not exhibit such a sharp, temperature-dependent cutoff tied to FGT’s ferromagnetic phase transition.

At a given temperature, the magnitude of the SVE can be optimized by the bias current (Fig. 3a–d). For example, at T = 10 K, a large SVE of 15,720% is obtained for I = −1 nA (Fig. 3b). The SVE amplitude extracted from the V-B plots (Fig. 3d) agrees well with the values obtained from the I-V curves (Fig. 3c) measured in the parallel and antiparallel configurations. Figure 3e shows the color scale plot of the SVE amplitude versus the bias current and temperature. The maximum SVE at low T occurs under a negative current bias, switches to positive current bias at around 40 K, and then switches back under a negative current bias at 180 K, reflecting the T-dependence of VP. The conductance dI/dV of the device in the parallel state shows a similar T-dependence to that of the bias current for maximum SVE below 170 K (Fig. 3e). We attribute this non-monotonic T-dependence of the maximum SVE and dI/dV to the competition of two effects: with decreasing T the carrier densities in the p-GaSe and n-InSe layers decrease, which reduces the built-in electric field and consequently lowers the spin-dependent tunneling conductance; simultaneously the spin polarization at the interface increases and charge/spin scattering rate decreases, leading to longer spin lifetimes. The spin voltage effect in the FGT/p-GaSe/n-InSe/FGT vertical vdW devices with thin spacer layers is robust and reproducible. The temperature-dependent and bias-dependent SVE for the additional heterostructure device with 5 nm p-GaSe/5 nm n-InSe junction (device D) are shown in Supplementary Figs. S4-5.

a V-B curves for different bias currents at 10 K. b V-B curve under a bias current I = −1 nA corresponding to SVE = 15,720%. c I-V curves in the parallel and antiparallel magnetization alignments. d SVE as a function of I extracted from the V-B (points) and I-V (line) curves. e Dependence of SVE on T and I. The dotted line shows the conductance versus T in the parallel magnetization alignment.

The zero-bias SVE is not caused by a temperature gradient due to the spin Seebeck effect23. To exclude this phenomenon, we designed and fabricated a device structure comprising a magnetic tunnel junction and a heating element. As shown in Fig. 4a, the FGT/p-GaSe/n-InSe/FGT junction (device G) is capped with hBN/semi-metal Td-WTe2. WTe2 acts as the top heating resistor and is separated from the junction by a hBN layer. In this structure, we can create a thermal gradient along the vertical direction by applying an electrical current to the WTe2 layer. The temperature of the WTe2 layer was estimated from its resistance. Firstly, we tested the resistance curve of WTe2 as a function of the heating current. As the heating current increases, the resistance of WTe2 exhibits a quadratic increase, consistent with the Joule heating effect (details see Supplementary Note 2 and Fig. S6). We examined the relationship between the resistance and temperature of WTe2 under conditions (1 μA) of negligible Joule heating, as illustrated in Fig. 4b. Then, the temperature of the WTe2 layer was increased under different heating currents. As the heating current increases from 0 to 0.5, 0.75, and 1 mA, the corresponding temperature of the WTe2 layer increases from 10 to 15, 20, and 25 K, respectively. The hysteresis loops of zero-bias anomalous SVE under different heating currents are shown in Fig. 4c. We find that the zero-bias SVE is not sensitive to the thermal gradient. Thus, we conclude that the SVE cannot originate from the generation of a spin voltage due to the thermal injection of spin currents from the FGT into the junction.

a The optical image of device G, which consists of a bottom-FGT/5-nm-InSe/5-nm-GaSe/top-FGT/15-nm-hBN/20-nm-Td-WTe2 heterojunction. Joule heating is generated by applying a constant current through the top WTe2 layer of the device, creating a vertical thermal gradient. b The dependence of WTe2 resistance on temperature ranging from 10 K to 40 K at 1 μA. c The zero-bias SVE curves under different vertical thermal gradients.

We note that the zero-bias SVE was observed in several devices with a similar structure, but differing for the magnetic electrode or p-n junction, e.g. in MTJs based on FGT/p-GaSe/n-MoS2/FGT and on Fe5GeTe2/p-GaSe/n-InSe/Fe5GeTe2, supporting the universality of the measured phenomenon (Supplementary Note 3 and Figs. S7-8). To further test the SVE at zero-bias, we conducted additional experiments: a resistor was connected in series with a magnetic tunnel junction, which acts as a current source in the antiparallel configuration of the FGT (Supplementary Note 4 and Fig. S9).

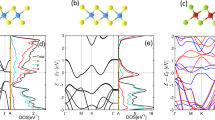

To explain the zero-bias SVE, we examine the spin-polarization of electrons at the semiconductor/ferromagnet interface and the asymmetric diffusion of spin-up/spin-down electrons (Fig. 5). For a structure where a single spacer layer (GaSe or InSe) is embedded between two FGT layers (Fig. 5 ai, ii), the bidirectional diffusion of spins between the FGT cannot generate any spin-voltage at zero-bias, regardless of whether the two FGT have the same or opposite spin polarization orientations. However, when a p-n junction is embedded between the FGT layers, the spin diffusion becomes asymmetric due to the built-in electric field of the p-n junction (Fig. 5aiii, iv). This asymmetry leads to a net spin diffusion in one direction, which we model by a combination of first-principles DFT and semiclassical transport equations.

a Schematics depicting a single spacer layer between two FGT electrodes in parallel (i) and antiparallel (ii) state, and a p-n junction spacer layer between two FGT electrodes in parallel (iii) and antiparallel (iv) state. b Calculated profile of the spin polarization P across the GaSe (5 nm)/InSe (5 nm) junction. Inset: Sketch of the spin density in the junction giving rise to the SVE. c, d Schematic energy band diagram for the FGT/GaSe/InSe/FGT junction in (c) the parallel state and (d) antiparallel state. The dotted lines indicate the electron spin up (red) and spin down (blue) quasi-Fermi levels.

From DFT, we derive the energy band diagram and electric field of the p-n junction, and the spin splitting of the energy bands due to the FGT (see details in the Supplementary Notes 5,6 and Figs. S10−12). The spin-polarized transport across the p-n junction is simulated using drift-diffusion equations for electrons and holes24. Due to the lighter mass and higher mobility of electrons, the spin signal is predominantly determined by electrons (see details in the Supplementary Note 7 and Fig. S13)25. Figure 5b shows the spin polarization P = (n↑ - n↓)/(n↑ + n↓), where n↑ and n↓ are the spin-resolved electron densities. At the FGT/GaSe interface, we assume P = 0.66 at zero-bias voltage, as informed by studies of FGT/hBN/FGT devices26. In conventional spin valves, the spatial dependence of the spin polarization P and the spin density s = n↑ - n↓ are equivalent2,3. However, while P decays monotonically away from the point of injection of electron spins at the FGT/GaSe interface, the dependence of s is non-monotonic (see inset of Fig. 5b). This non-monotonicity induces an asymmetric distribution of spin-polarized electrons at the FGT/GaSe and FGT/InSe interfaces. Furthermore, the measured spin-voltage difference at zero bias between the parallel and antiparallel states is estimated by considering the energy cost of spin flipping at the FGT/InSe interface (see details in the Supplementary Note 8 and Fig. S14). Taking into account the spin polarization of the injected electrons at the interface between GaSe and FGT, the energy difference Δμ at the edge of the InSe is 1.17 meV for p-GaSe (5 nm)/n-InSe (5 nm) and 0.80 meV for p-GaSe (9 nm)/n-InSe (5 nm), respectively. For simplicity, the spin splitting of the top and bottom FGT is assumed to be the same, which is consistent with the DFT calculations. Then the energy level diagram for parallel and antiparallel states can be drawn as shown in Fig. 5c, d, respectively. The measurable voltage difference between antiparallel and parallel states generated by the spin flipping at the InSe/FGT interface is estimated to be 690.3 μV, which is the same order of magnitude as the experimental observation. The above theoretical analysis reveals the formation of a non-equilibrium spin-engine state, which is characterized by two key processes: 1) spin injection at the FGT/GaSe interface driven by the built-in electric field—this generates a spin current flowing across the junction, and the spin current induces spin accumulation, which gives rise to the detectable voltage signal; 2) spin flipping at the InSe/FGT interface—spin flipping reduces the spin energy state, prompting the device to absorb thermal fluctuations from the environment to maintain its own magnetic state. Since the SVE depends on the built-in electric field of the junction as well as on the spin polarization of the FGT/GaSe(InSe) interface, the non-monotonic SVE with both temperature and electric field can be explained.

Table 1 compares the zero-bias SVE signal of our all vdW FGT/p-GaSe/n-InSe/FGT MTJs with the TMR signal of several other types of MTJs, such as traditional covalent bonding materials-based MTJs, vdW barrier-based MTJs and all vdW MTJs. At low temperature (T = 5 K), MTJs based on the half-metal CrO2/SnO2/Co heterostructure exhibit a zero-bias spin voltage of ~60 μV (where VAP ≠ 0 and VP ≈ 0 at I = 0) that persists for at least 30 minutes27. This was ascribed to the diffusion of the spins and their flipping under a strong exchange field27, leading to an electrochemical potential difference between spin-up and spin-down electrons28,29. This difference was detected in early spin-injection experiments30. Additionally, a zero-bias SVE of -70% was observed in Co/C/MgO/C/Co MTJ devices (where IP ≠ IAP ≠ 0 at V = 0), in which the energy source of this spin-driven electrical power is attributed to the harvesting of thermal fluctuations energy31,32. As shown in Table 1, the zero-bias SVE magnitude in our all vdW p-n junction spin devices is significantly higher, indicating opportunities for higher signal-to-noise ratio and lower energy consumption in spintronic applications.

Discussion

Our demonstration of efficient spin injection and large magnetoresistance in vdW heterostructures has implications across several fields. The inherent nonlinearities in semiconductors and electrical tunability of 2D ferromagnetism offer opportunities for future developments. Just as the nonlinear response of p-n junctions was crucial for early transistors1, the zero-bias anomalous spin-voltage effect could be employed to implement spin logic and amplification in atomically thin vdW p-n junctions. The current use of an applied magnetic field in our experiments could be replaced by using spin-orbit torques33 to switch the ferromagnet, enabling seamless integration nonvolatile magnetic memory and spin logic. By using a spin-orbit torque and vdW semiconductors with a direct band gap, the angular momentum from injected spin-polarized carriers could be transferred to control the helicity of the emitted light for low-power and long-distance spin-information transfer34,35. While the primary focus of spin valves is their magnetoresistance2,3,4,5,6, changing the relative magnetization orientation also changes the resulting fringing fields. By considering heterostructures of our FGT-based spin valves with superconductors, such fringing fields, could potentially support elusive spin-triplet superconductivity, offering a versatile platform for a fault-tolerant topological quantum computing36,37 by creating Majorana states in 2D geometries38.

Methods

Fabrication of the FGT/p-GaSe/n-InSe/FGT vertical heterostructure devices

Figure 1a in the main text shows a schematic illustration of our spin-valve devices. The few-layer Td-WTe2 (from HQ Graphene), FGT (from HQ Graphene), ɛ-GaSe (from 2D Semiconductors) and γ-InSe (was grown by the Bridgman method at the Frantsevich Institute for Problems of Materials Science, Ukraine) flakes were mechanically exfoliated using adhesive tape from bulk single crystals of Td-WTe2, FGT, ɛ-GaSe and γ-InSe, respectively. The few-layer FGT, serving as ferromagnetic electrode, was mechanically exfoliated onto a stamp. Then the stamp was adhered to a glass slide to facilitate handling and identification of thin layers by optical microscopy. Subsequently, the target FGT sheet was transferred onto a SiO2/p-Si substrate. Using the same method, the InSe sheet was transferred on top of the FGT sheet. After that, the GaSe sheet was transferred on top of the InSe sheet to fabricate a 2D heterojunction. Finally, another exfoliated few-layer FGT sheet was transferred onto the InSe sheet to form the top electrode. To prevent the FGT from oxidizing once the device was exposed to air, a 15 nm-thick hBN layer was used to cap the entire heterostructure stack. The two FGT sheets were contacted with metallic electrodes, which were fabricated on the substrate prior to the transfer using standard photoetching, thermal evaporation and lift-off. After the transfer process, the MTJ devices were baked at 120 °C for 10 minutes to ensure intimate contact between the interfaces of the various vdW materials. The active overlap area of this vertical device is typically around 5 μm2. The thickness of the FGT, InSe and GaSe flakes was determined by atomic force microscopy (Bruker Multimode 8). The typical thickness of the 2D materials used for the vertical heterostructures in this work is between 5−15 nm. All the fabrication processes were carried out in a glove box with a concentration of less than one part per million of water and oxygen.

Measurements of SVE

A Keithley 2602 current source and a Keithley 2182 A nanovoltmeter were used for the magnetoresistance effect measurements. An Agilent Technology B1500A parameter analyzer was used to study the output characteristics of the spin-valve devices. All measurements were conducted in a Cryogenic Probe Station with magnetic field out-of-plane and at temperatures below and above the Curie temperature (Tc = 220 K) of FGT.

Computational methods

The electronic structures of different layers γ-InSe, ε-GaSe, FGT and their heterostructures were investigated using the general potential linearized augmented plane-wave (LAPW) method as implemented in the WIEN2K code. The local density approximation (LDA) was used to describe the exchange and correlation functional, which can yield reasonable electronic structures for InSe, GaSe, and FGT. By fully relaxing both the lattice constants and atomic positions, the optimized lattice constants (a, c) of (3.7 Å 15.7 Å), (4.0 Å, 24.4 Å), and (3.9 Å, 16.3 Å) were obtained for the bulk GaSe, InSe and FGT, respectively. The lattice constants of few-layer films were kept the same as those in the optimized bulk structures.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information or available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes that support the theoretical part of this study are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alferov, Z. I. Nobel Lecture: The double heterostructure concept and its applications in physics, electronics, and technology. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 767–782 (2001).

Žutić, I., Fabian, J. & Das Sarma, S. Spintronics: Fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 323–410 (2004).

Maekawa, S. Concepts in Spin Electronics. (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Moodera, J. S., Kinder, L. R., Wong, T. M. & Meservey, R. Large magnetoresistance at room temperature in ferromagnetic thin film tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3273–3276 (1995).

Parkin, S. S. P. et al. Giant tunnelling magnetoresistance at room temperature with MgO (100) tunnel barriers. Nat. Mater. 3, 862–867 (2004).

Yuasa, S., Nagahama, T., Fukushima, A., Suzuki, Y. & Ando, K. Giant room-temperature magnetoresistance in single-crystal Fe/MgO/Fe magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 3, 868–871 (2004).

Ohno, H. Making nonmagnetic semiconductors ferromagnetic. Science 281, 951–956 (1998).

Dietl, T. & Ohno, H. Dilute ferromagnetic semiconductors: Physics and spintronic structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 187–251 (2014).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Ajayan, P., Kim, P. & Banerjee, K. Two-dimensional van der Waals materials. Phys. Today 69, 38–44 (2016).

Burch, K. S., Mandrus, D. & Park, J.-G. Magnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals materials. Nature 563, 47–52 (2018).

Zhu, W. & Wang, K. Aharonov-Anandan phases in a van der Waals antiferromagnet CrPS4. Sci. Bull. 70, 1001–1003 (2025).

Zega, T. J. et al. Determination of interface atomic structure and its impact on spin transport using Z-contrast microscopy and density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 196101 (2006).

Chuang, S. L. Physics of Optoelectronic Devices. 2nd edn, (Wiley, 2009).

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Wu, S. et al. Monolayer semiconductor nanocavity lasers with ultralow thresholds. Nature 520, 69–72 (2015).

Fei, Z. et al. Two-dimensional itinerant ferromagnetism in atomically thin Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Mater. 17, 778–782 (2018).

Jiang, X. et al. Recent progress on 2D magnets: Fundamental mechanism, structural design and modification. Appl. Phys. Rev. 8, 031305 (2021).

Cardoso, C., Soriano, D., García-Martínez, N. A. & Fernández-Rossier, J. Van der Waals spin valves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 067701 (2018).

Zhu, W. et al. Large and tunable magnetoresistance in van der Waals ferromagnet/semiconductor junctions. Nat. Commun. 14, 5371 (2023).

Zhu, W. et al. Large tunneling magnetoresistance in van der Waals ferromagnet/semiconductor heterojunctions. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104658 (2021).

Hu, C. et al. From two- to multi-state vertical spin valves without spacer layer based on Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals homo-junctions. Sci. Bull. 65, 1072–1077 (2020).

Ramos, R. & Saitoh, E. Spin Caloritronics, in Spintronics Handbook: Spin Transport and Magnetism. 2 edn, Vol. 3 269-299 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2019).

Žutić, I., Fabian, J. & Das Sarma, S. Spin injection through the depletion layer: A theory of spin-polarized p-n junctions and solar cells. Phys. Rev. B 64, 121201 (2001).

Madelung, O. R., U.; Schulz, M. Non-Tetrahedrally Bonded Elements and Binary Compounds I. (Springer, 1998).

Wang, Z. et al. Tunneling spin valves based on Fe3GeTe2/hBN/Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals heterostructures. Nano Lett. 18, 4303–4308 (2018).

Miao, G.-X., Xiao, G. & Gupta, A. Anomalous bias dependence in magnetic tunnel junctions based on half-metallic CrO2 with heteroepitaxial SnO2 tunnel barrier. Europhys. Lett. 87, 47006 (2009).

van Son, P. C., van Kempen, H. & Wyder, P. Boundary resistance of the ferromagnetic-nonferromagnetic metal interface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 2271–2273 (1987).

Wunderlich, J. et al. Coulomb blockade anisotropic magnetoresistance effect in a (Ga,Mn)As single-electron transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 077201 (2006).

Johnson, M. & Silsbee, R. H. Interfacial charge-spin coupling: Injection and detection of spin magnetization in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 1790–1793 (1985).

Katcko, K. et al. Spin-driven electrical power generation at room temperature. Commun. Phys. 2, 116 (2019).

Chowrira, B. et al. Quantum advantage in a molecular spintronic engine that harvests thermal fluctuation energy. Adv. Mater. 34, 2206688 (2022).

Li, Y., Edmonds, K. W., Liu, X., Zheng, H. & Wang, K. Manipulation of magnetization by spin–orbit torque. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2, 1800052 (2019).

Dainone, P. A. et al. Controlling the helicity of light by electrical magnetization switching. Nature 627, 783–788 (2024).

MacNeill, D. et al. Control of spin–orbit torques through crystal symmetry in WTe2/ferromagnet bilayers. Nat. Phys. 13, 300–305 (2017).

Desjardins, M. M. et al. Synthetic spin–orbit interaction for Majorana devices. Nat. Mater. 18, 1060–1064 (2019).

Amundsen, M., Linder, J., Robinson, J. W. A., Žutić, I. & Banerjee, N. Colloquium: Spin-orbit effects in superconducting hybrid structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 021003 (2024).

Zhou, T., Mohanta, N., Han, J. E., Matos-Abiague, A. & Žutić, I. Tunable magnetic textures in spin valves: From spintronics to Majorana bound states. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134505 (2019).

Ikeda, S. et al. Tunnel magnetoresistance of 604% at 300K by suppression of Ta diffusion in CoFeB∕MgO∕CoFeB pseudo-spin-valves annealed at high temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 082508 (2008).

Sukegawa, H. et al. Tunnel magnetoresistance with improved bias voltage dependence in lattice-matched Fe/spinel MgAl2O4/Fe(001) junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 212505 (2010).

Asshoff, P. U. et al. Magnetoresistance of vertical Co-graphene-NiFe junctions controlled by charge transfer and proximity-induced spin splitting in graphene. 2D Mater. 4, 031004 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Spin-valve effect in NiFe/MoS2/NiFe junctions. Nano Lett. 15, 5261–5267 (2015).

Piquemal-Banci, M. et al. Insulator-to-metallic spin-filtering in 2D-magnetic tunnel junctions based on hexagonal boron nitride. ACS Nano 12, 4712–4718 (2018).

Min, K.-H. et al. Tunable spin injection and detection across a van der Waals interface. Nat. Mater. 21, 1144–1149 (2022).

Zhu, S. et al. Voltage tunable sign inversion of magnetoresistance in van der Waals Fe3GeTe2/MoSe2/Fe3GeTe2 tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 222401 (2024).

Lin, H. et al. Spin-valve effect in Fe3GeTe2/MoS2/Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals heterostructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 43921–43926 (2020).

Pan, Z.-C. et al. Room-temperature orbit-transfer torque enabling van der Waals magnetoresistive memories. Sci. Bull. 68, 2743–2749 (2023).

Zhu, W. et al. Large room-temperature magnetoresistance in van der Waals ferromagnet/semiconductor junctions. Chin. Phys. Lett. 39, 128501 (2022).

Jin, W. et al. Room-temperature and tunable tunneling magnetoresistance in Fe3GaTe2-based 2D van der Waals heterojunctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 36519–36526 (2023).

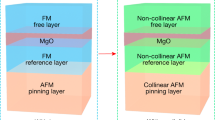

Jin, W. et al. Tunable high-temperature tunneling magnetoresistance in all-van der Waals antiferromagnet/semiconductor/ferromagnet junctions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2402091 (2024).

Acknowledgements

K.W. is grateful to Prof. H. Ohno for the useful discussion. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2022YFA1405100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12241405, 12174384 and 12404146). A.P. acknowledges the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme Graphene Flagship Core 3. T.Z. and I.Ž. were supported by U.S. DOE, Office of Science BES, Award No. DE-SC0004890 (DFT calculations), I.Ž. was supported by U.S. National Science Foundation, Award No. ECCS-2512491 (modeling p-n junctions). Z.R.K. acknowledges funding through a Nottingham Research Fellowship from the University of Nottingham.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.W. conceived the work. W.Z. fabricated the devices, W.Z., Z.W., T.H., C.H., H.L., X.L., Y.D. and Q.L. performed the experiments. W.Z., C.H. and K.W. analyzed the data. Z.W., Y.D., I.Ž. and K.W. carried out the modeling. T.Z. and I.Ž. performed DFT calculations. Z.R.K., Z.D.K. and A.P. provided the InSe bulk crystals and conducted the preliminary studies of InSe. W.Z., Z.W., C.H., L.Z., A.P., I.Ž., H.Z. and K.W wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, W., Wang, Z., Hu, T. et al. Two-dimensional magnetic tunnel p-n junctions for low-power electronics. Nat Commun 17, 1283 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68043-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68043-2