Abstract

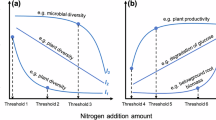

Global nitrogen (N) enrichment promotes soil organic carbon (SOC) accumulation but often causes biodiversity loss in plants and soil microbes, creating a central challenge for achieving co-benefits of carbon accumulation and biodiversity conservation. The extent to which biodiversity contributes to SOC accumulation, and how these trade-offs can be mitigated under N enrichment remains poorly understood. Here, we conduct a global meta-analysis of N enrichment experiments encompassing 2141 observations from 275 studies to evaluate the contributions of plant, bacterial, and fungal diversity to SOC accumulation and to determine associated ecological thresholds. Our findings indicate that biodiversity, especially in plant communities, is the most important factor for SOC accumulation. We identify three distinct N thresholds characterized by different ecological responses: biodiversity loss accelerates at 50 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, soil degradation persists at 200 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, and SOC accumulation declines beyond this point. Given that the promoting effects of bacterial, fungal, and plant diversity on SOC diminish or even reverse at 50, 67, and 74 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, respectively, we suggest limiting fertilization to around 50 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, as the trade-off between biodiversity loss and SOC accumulation under N enrichment is potentially minimized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil is the largest carbon (C) reservoir in terrestrial ecosystems, playing a critical role in regulating the global C cycle. Even small changes in the soil organic carbon (SOC) pool can have profound impacts on ecosystem services and land-climate feedbacks1,2. Soil N availability significantly influences storage capacity of SOC, since N is a key component of SOC3,4. While increased N input has alleviated constraints on global food production, it has also elevated ecosystem N availability, leading to eutrophication and altered ecosystem processes5,6,7. Previous studies have demonstrated that N enrichment can enhance SOC storage by promoting the formation of larger soil aggregates, improving soil fractions, and increasing N use efficiency4,8,9,10. However, these effects are not always consistent, as some studies have documented neutral or even negative outcomes11,12, potentially due to differences in substrate quantity, mineral associations, environmental conditions, and biodiversity13. Biodiversity, in particular, is widely recognized to regulate soil C cycling14,15, and its loss drives large-scale changes in ecosystem energy flow and nutrient cycling16,17. Higher plant diversity often increases biomass inputs and root exudation18, while soil microbial diversity governs the balance between C catabolism (decomposition) and anabolism (biomass and extracellular production)19,20,21, thereby shaping SOC dynamics. N enrichment generally reduces biodiversity22,23,24,25, primarily through mechanisms such as competitive exclusion, soil acidification, and cation toxicity24,26. Yet microbial diversity exhibits inconsistent responses27,28. For example, N enrichment significantly reduced overall microbial diversity, but the decline was mainly observed for bacteria, whereas fungal diversity remained unchanged27. This highlights the complex and taxon-specific nature of microbial responses to N enrichment. Therefore, such divergent responses between plant and microbial diversity may weaken the positive biodiversity effects on SOC sequestration29,30. Moreover, the potential erosion of functional diversity could further decrease resource-use efficiency and ecosystem productivity, posing a major challenge for sustaining SOC accumulation while mitigating biodiversity loss14,19,22,31,32,33. Despite increasing evidence of these complexities4,9,27,34, few studies have jointly assessed the relative contributions of major drivers, including plant and microbial diversity and biomass, soil physicochemical attributes (e.g., pH, moisture, nutrient availability), and climatic variables (e.g., mean annual precipitation (MAP), mean annual temperature (MAT)), to SOC responses under N enrichment. Therefore, a global assessment of the factors underpinning SOC dynamics is critical for reducing uncertainty in biogeochemical models of soil C turnover and advancing our understanding of how biodiversity mediates soil C dynamics in an N-enriched world35.

Biodiversity and soil C conservation are dual priorities in the global effort to mitigate climate change36,37. However, N enrichment can disrupt this co-benefit over time, decoupling biodiversity and C goals22. For example, a 27-year field experiment in temperate grassland reported SOC gains under high N input, but at the cost of substantial plant diversity loss38. Similarly, a global meta-analysis revealed that soil bacterial and fungal diversity are strongly negatively associated with soil C content, and their linkages are influenced by N fertilization rate and duration22. In contrast, tree species mixtures with high diversity can enhance SOC accumulation under elevated N availability39. These findings suggest that biodiversity-SOC relationships under N enrichment are context-dependent, and sustained N inputs may trigger trade-offs under specific environmental conditions. Therefore, identifying ecological thresholds along N gradients is essential to anticipate when biodiversity losses may begin to undermine soil C gains40,41. Recognizing and quantifying such thresholds is crucial for ecosystem-based management and policy formulation, as they offer valuable benchmarks for designing effective management interventions and conservation targets42,43,44,45. While prior studies have observed nonlinear or saturating responses of biodiversity and SOC to N inputs, systematic identification of critical thresholds remains limited. Given their high metabolic rates and short generation times46, soil microbial communities are more sensitive and responsive to environmental change than plants47,48 and are therefore expected to exhibit abrupt shifts at lower N levels than plants. However, these microbial shifts may not immediately translate into changes in SOC, particularly for mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC), which is resistant to rapid turnover49. This temporal lag suggests that biodiversity thresholds, particularly for soil microbes, may precede those for C, potentially delaying detectable SOC destabilization under N enrichment. Understanding how biodiversity and SOC in terrestrial ecosystems respond to increasing N inputs is critical for advancing ecological threshold theory and informing estimates of N input levels that agroecosystems and natural ecosystems can tolerate before facing heightened risks of biodiversity loss and soil C destabilization.

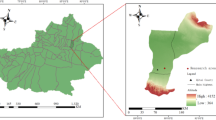

To address this knowledge gap, we compile a global database containing 2,141 observations from 275 in situ N enrichment experiments (Fig. 1a, b), spanning a wide range of climates (MAT from −9 to 30 °C and MAP from 100 to 4500 mm), vegetation types (farmlands, grasslands, and forests), and soil properties (pH from 3.5 to 9.0, SOC from 1.6 to 203.8 g C/kg soil). We examine how plant and microbial diversity and biomass jointly affect SOC accumulation under N enrichment. Additionally, we quantify the critical thresholds of N inputs at which shifts in plant and microbial communities and SOC accumulation occur, and identify a defined window where soil C gains can be achieved with minimal biodiversity loss. This framework allows us to comprehensively assess the role of biodiversity in mediating SOC and to reveal the critical N thresholds that enable co-benefits of biodiversity conservation and soil C accumulation globally in an N-enriched world.

Distribution of study sites is shown globally (a) and across Whittaker’s biomes (b). The base world map was sourced from Natural Earth, supported by the North American Cartographic Information Society (https://www.naturalearthdata.com). Effects of N enrichment on diversity in plants (c), soil bacteria (d), and fungi (e). Effects of N enrichment on biomass in plants (f) and soil microbes (g). h Effects of N enrichment on SOC. Values are mean effect size ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs). If the 95% CI value does not overlap with zero, the response is considered significant. The number of observations in each variable is given on the right. Closed symbols indicate significant effects (α = 0.05), and the open symbols indicate nonsignificant effects. Compound N refers to fertilizers composed of multiple nitrogen forms (e.g., mixtures of nitrate, ammonium, and/or urea). Organic N refers to industrial organic fertilizers, livestock manure, and compost. CO(NH₂)₂ was classified separately (“Urea N”) owing to its rapid hydrolysis to ammonium, which differentiates it from other organic N sources such as manure or compost. Created in BioRender. Jiao, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/814s45u. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Results and discussion

N enrichment effects on biodiversity and SOC

N enrichment consistently reduced diversity across plant and soil microbial communities, with declines of 12.5% in plants (95% confidence interval (CI): −17.0% to −7.8%, not applicable to farmland; P < 0.001), 5.5% in bacteria (95% CI: −7.7% to −3.1%; P < 0.001), and 0.98% in fungi (95% CI: −4.6% to 2.8%; P = 0.604) (Fig. 1c–e), aligning with findings from recent studies22,50. The weak negative effect of N enrichment on fungal diversity likely reflects heterogeneous responses among functional guilds51, as N reduces the diversity and abundance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) while simultaneously increasing the relative proportion of saprotrophic fungi52,53. This functional reorganization may obscure declines in total fungal diversity. In addition, the compensatory dominance of tolerant fungal taxa may buffer the loss of more sensitive species under global change conditions54. Despite receiving frequent N inputs, farmland exhibited the largest declines in soil microbial diversity compared to natural ecosystems, with decreases of 6.9% in bacterial diversity (95% CI: −11.7% to −1.8%; P = 0.009) and 5.6% in fungal diversity (95% CI: −13.4% to 3.0%; P = 0.194). This suggests that agricultural soil microbial diversity may continue to decline under future N enrichment. Additionally, plant diversity declined mainly in temperate regions (−16.4%, 95% CI: −22.0% to −10.3%; P < 0.001), while bacterial diversity decreased in both temperate (−5.7%, 95% CI: −8.3% to −3.1%; P < 0.001) and tropical regions (−5.5%, 95% CI: −10.0% to −0.8%; P = 0.021). In contrast, fungal diversity showed no significant change within any climatic region, but shifted from negative to positive responses with decreasing temperature (−1.2%, 95% CI: −5.1% to 2.9%, in temperate regions; 12.9%, 95% CI: −1.7% to 29.7%, in polar regions; all P > 0.05). The greater decline in plant and bacterial diversity in warm regions may be explained by the amplification of aboveground biomass responses to N addition under higher temperature and precipitation, which intensifies light competition and leads to the exclusion of rare species55. Fungi may be more resistant because of their higher tolerance to osmotic and environmental stress56. These patterns highlight the influence of regional climatic conditions on the responses of plant and microbial communities to N inputs. Declines in plant and soil microbial diversity intensified with increasing N rates and prolonged exposure, likely driven by continued soil acidification24,57. These contrasting responses between plant and microbial communities underscore the complexity of ecosystem and climate dynamics under N enrichment, emphasize the importance of a nuanced understanding of N-driven linkages between above- and belowground processes in terrestrial ecosystems.

Beyond biodiversity loss, N enrichment also significantly reshaped biomass dynamics in both above- and belowground compartments. In contrast with reductions in diversity, N enrichment significantly increased plant biomass by 32.8% (95% CI: 24.8% to 41.3%; P < 0.001) while reducing soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) by 5.8% (95% CI: −10.6% to −0.7%; P = 0.027), which was more pronounced in grassland ecosystems (Fig. 1f, g). The stronger responses may be linked to greater increases in photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and water use efficiency under N addition in herbaceous species in grasslands, compared to woody species in forests58. Within each climatic region, plant biomass showed a significant increase in tropical regions (46.4%, 95% CI: 28.9% to 66.4%; P < 0.001), whereas MBC showed greater reductions in temperate regions (−8.9%, 95% CI: −14.5% to −2.8%; P = 0.004). Both trends intensified under higher N rates and longer exposure durations. Additionally, plant biomass showed a non-significant increase under organic fertilizer application (17.9%, 95% CI: −16.0% to 65.5%; P = 0.342), suggesting that organic amendments may partially mitigate the trade-off between diversity loss and biomass gain40. As expected, SOC increased under N enrichment (Fig. 1h), particularly in grassland ecosystems (6.6%, 95% CI: 3.0% to 10.2%; P < 0.001), reinforcing their role as C sinks in the context of global N enrichment59. Across climatic regions, SOC accumulation tended to decline from cold (9.5%, 95% CI: −5.3% to 26.7%; P = 0.219) to warm regions (0.9%, 95% CI: −3.6% to 5.5%; P > 0.5). This pattern is consistent with the metabolic theory of ecology, which predicts that increasing temperature enhances microbial metabolic activity and accelerates organic matter decomposition, thereby limiting net SOC storage9,60. Unlike other variables, SOC accumulation showed no consistent increase with rising N rates or durations, indicating its complex and the uncertainty of SOC stock predictions under future N enrichment scenarios. These findings highlight the complexity of ecosystem responses to N enrichment and the need for targeted management strategies to balance soil C storage and biodiversity conservation.

In addition to its biological effects, N enrichment also altered key soil chemical properties. N enrichment significantly reduced soil pH by 27.5% (95% CI: −32.2% to −22.5%; P < 0.001), driven primarily by increases in total N (TN) (11.0%, 95% CI: 6.9% to 15.2%; P < 0.001), nitrate nitrogen (NO₃−-N) (111.1%, 95% CI: 82.7% to 144.0%; P < 0.001), and ammonium nitrogen (NH₄+-N) (50.1%, 95% CI: 33.4% to 68.8%; P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1a–d). Despite these changes, soil phosphorus (P), including total P (TP) and available P (AP), remained largely unaffected (all P > 0.05), indicating that our study excluded scenarios involving co-addition of N and P (Supplementary Fig. 1e, f). Unexpectedly, the reduction in soil pH in grassland was nearly identical to that in farmland (−30.0% vs. −30.6%; Supplementary Fig. 1d). This may be attributed to their low-stature plant communities reaching N saturation more readily, leaving more unassimilated H+ and reactive N in the soil61. Additionally, limited precipitation in many grassland systems may constrain plant uptake and buffering capacity, further exacerbating acidification under elevated N62. Regional variations in pH reduction were also evident, with the smallest declines observed in polar regions (−19.9%, 95% CI: −38.4% to 4.0%; P = 0.10), followed by tropical regions (−22.7%, 95% CI: −30.7% to −13.8%; P < 0.001), while temperate regions exhibited the greatest declines (−30.0%, 95% CI: −35.1% to −24.4%; P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Temperate soils experienced the strongest pH decline, likely due to their weak buffering capacity and widespread podzolization, which facilitates Al³⁺ release and amplifies acidification63. In contrast, tropical soils form stable Al oxides that immobilize Al³⁺, while polar soils show slight change due to low biological activity and thick organic horizons buffering acidity63,64. Furthermore, the reduction in soil pH was amplified by increasing N rates and longer durations, suggesting that the current quantification of N enrichment effects may underestimate its long-term impacts on soil health and ecosystem functioning. Notably, the application of organic fertilizers significantly mitigated acidification compared to synthetic N fertilizers, likely due to their buffering effects through enhanced cation exchange capacity40. Given the pivotal role of soil pH in maintaining ecosystem diversity and multifunctionality, sustainable N management strategies should prioritize organic fertilizers and limit excessive use of synthetic fertilizers in agriculture.

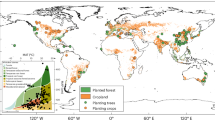

Given that plant and microbial biomass constitute the immediate foundation for SOC formation and turnover, we independently modeled the global responses of plant biomass, microbial biomass, and SOC under N enrichment to better elucidate ecosystem C dynamics (Fig. 2). Across regions, plant biomass exhibited consistently positive responses, especially in temperate and boreal regions of North America, Europe and Asia (Fig. 2a), reflecting N-stimulated productivity to N inputs65. In contrast, MBC exhibited greater spatial heterogeneity. Positive responses were prevalent in tropical and polar regions, while declines were widespread across mid-latitude temperate ecosystems such as central North America, Europe, and East Asia (Fig. 2b). This divergence could be attributed to regional disparities in baseline N deposition and soil sensitivity66. In tropical and polar regions with low ambient N, moderate enrichment promotes microbial growth. However, excess N in high-background areas induces acidification and nutrient imbalance, ultimately suppressing microbial biomass67,68. Similarly, SOC responses were largely positive across temperate regions, particularly in Europe and northern Asia. However, negative responses prevailed in parts of the Southern Hemisphere and tropical regions, including southern Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia (Fig. 2c). The contrasting trends are likely shaped by nutrient limitation and turnover dynamics that differ across ecosystems. In temperate regions, N addition stimulates plant inputs while simultaneously suppressing decomposition, thereby favoring soil C accumulation69. In contrast, phosphorus limitation and high decomposition rates dominate in many tropical regions, where added N often fails to enhance biomass input and may even accelerate C loss70. Together, these spatial patterns illustrate how N enrichment reshapes C cycling across climatic gradients and emphasize the importance of region-specific N management aligned with soil C accumulation objectives.

Global patterns of N enrichment effects on plant biomass (a), soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) (b), and SOC (c). The maps were generated using random forest models at a spatial resolution of 0.25°. Uncertainties in the mapped changes are provided in Supplementary Fig. 16. Created in BioRender. Jiao, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/814s45u. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Biodiversity mediates SOC responses under global N enrichment

To understand how biodiversity and SOC respond to N enrichment, we first examined the main environmental predictors associated with diversity and SOC patterns, respectively. Using the random forest approach, we found that the response of plant diversity was strongly linked to N availability (TN, NH₄+-N and NO₃−-N), MAT, and soil moisture (Fig. 3a; all P < 0.05), reflecting their critical roles in supporting plant growth. In contrast, bacterial diversity was primarily associated with NH₄+-N and pH (Fig. 3b; all P < 0.05), whereas fungal diversity responded most strongly to NO₃−-N, MAT, and soil moisture (Fig. 3c; all P < 0.05). These findings are consistent with previous research, which highlights N-induced soil acidification as a primary predictor of biodiversity loss in terrestrial ecosystems71,72, while also underscoring the modulatory role of climatic factors in shaping biodiversity responses under N enrichment73. Given the direct contribution of plant and microbial biomass to the formation of SOC, we further identified the main predictors of these two biomass components. Our random forest and meta-regression analyses revealed that the responses of plant and microbial diversity are associated with changes in MBC under N enrichment (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 5), supporting that biodiversity contributes to belowground C turnover under N enrichment74. After controlling for N addition level in the meta-regression, we found that several pairwise associations remained significant (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Importantly, by integrating all abiotic and biotic factors (e.g., diversity and biomass of plants and soil microbial communities), our random forest analysis revealed that the responses of TN and plant diversity were the strongest predictors of SOC changes, with plant diversity playing a pivotal role in regulating SOC accumulation under N enrichment (Fig. 3d; P < 0.05). Our work supports the fundamental theory that biodiversity acts as a key regulator of ecosystem C dynamics33,75,76,77, suggesting the urgent need to incorporate the response of biodiversity to revisit SOC accumulation effect under N enrichment. Despite being much discussed, we provided the global evidence that biodiversity mediates SOC responses in the context of N enrichment.

Relative importance of each factor in predicting the response of plant richness (a), soil bacterial richness (b), fungal richness (c), and SOC (d) under N enrichment, based on the entire dataset (n = 2141). Variable importance represents the increase in mean error (computed on out-of-bag data) across trees when a predictor is permuted. Box boundaries represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, and whisker caps represent the 95th and 5th percentiles. Predictors shown in black are significant, whereas those in gray are non-significant (α = 0.05). MAT mean annual temperature, TN total N, SM soil moisture, NH4+-N ammonia nitrogen, NO3−-N nitrate nitrogen. The relationships between environmental factors (e.g., climatic variables and soil responses) and plant, soil microbial communities and SOC are shown in Supplementary Figs. 3–5. e Relationships between diversity (plant, soil bacterial, and fungal communities) and SOC under ambient conditions, evaluated using two-sided t-tests in mixed-effect models with study ID as a random factor. Values are mean effect size ± standard deviation (SD). f Associations between the responses of diversity (plant, soil bacterial and fungal communities) and SOC under N enrichment, evaluated using two-sided t-tests in mixed-effect meta-regression models, including study ID and N rate level as random factors to account for variability across studies and the N-induced potential co-variation. Values are mean effect size ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Numbers in parentheses below each P value in e, f indicate the number of observations. Created in BioRender. Jiao, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/814s45u. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Beyond identifying the key predictors of biodiversity and SOC, it is essential to assess whether and how biodiversity and SOC responses are interlinked under N enrichment. Mixed-effects meta-regression models revealed that N enrichment significantly altered the associations between bacterial, fungal, and plant diversity and SOC. Under control conditions, all three diversity metrics showed a significant positive correlation with SOC (Fig. 3e; all P < 0.05). Following N enrichment, plant and fungal diversity turned negative, whereas bacterial diversity remained positively linked to SOC (Fig. 3f; all P < 0.05). This shift suggests a transformation in ecosystem C cycling from synergistic to trade-off dynamics under N enrichment. The observed trade-off between plant diversity and SOC aligns with the competitive exclusion hypothesis, as SOC accumulation under N enrichment is primarily driven by increased plant biomass inputs3. The parallel responses of fungi and plants to N enrichment are likely rooted in the close functional integration between mycorrhizal fungi and their plant hosts51. Given that N enrichment affects both biodiversity and soil processes through multiple interacting pathways, the detected biodiversity-SOC associations may partly reflect shared environmental responses rather than direct causal relationships. Overall, these findings reveal a decoupling of soil C allocation between above- and belowground components under N enrichment29,78, and highlight the importance of incorporating synergistic plant–microbe responses into biogeochemical cycle models under future global change.

Critical thresholds of above- and belowground compartments and SOC

We analyzed the responses of plant and soil microbes, as well as SOC to increasing N rate and identified the thresholds at which these responses exhibited abrupt shifts. All measured variables showed nonlinear responses to rising N inputs (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figs. 6, 7, all P < 0.001). These shifts occurred in three distinct phases: accelerated biodiversity loss at 50 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, persistent soil degradation at 200 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, and a decline in SOC accumulation at higher N levels (Fig. 4a). In the first phase, plant and soil microbial diversity consistently declined with N enrichment, with sharp decreases observed at thresholds of 34, 48, and 50 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ for fungi, bacteria, and plants, respectively. Soil fungi appeared more tolerant to N enrichment than bacteria, yet exhibited earlier threshold responses. This earlier threshold response of fungi may be attributed to their dual ecological roles as both decomposers and plant symbionts, which expose them to multiple forms of N-induced stress79. For instance, fungi must maintain functional symbiosis with host plants under altered nutrient conditions while also coping with increasing cation toxicity from acidification79. These simultaneous demands may trigger earlier physiological adjustments, even if their overall tolerance to high N levels remains greater than that of bacteria. Plant diversity exhibited a higher N threshold, likely due to plants’ longer life cycles and slower population dynamics47, which delay their responses to environmental changes. The early thresholds observed for biological communities underscore the importance of biodiversity monitoring as an early-warning indicator for significant ecosystem transformations45, advocating for strategic conservation efforts to safeguard terrestrial ecosystems and their services. During the soil degradation phase, we observed a significant decline in soil pH occurring at 66 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹. MBC remained stable until a threshold of 87 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, after which it declined significantly. Although a threshold was identified for soil moisture, changes in soil water availability were minimal. Soil NH₄+-N, NO3−-N, and TN levels increased rapidly with N enrichment initially but stabilized after surpassing their respective thresholds. In the last phase, SOC accumulation and plant biomass both showed positive correlations with N input before reaching their thresholds but shifted to negative correlations beyond these points. This indicates that continued microbial diversity loss and persistent soil acidification could offset the SOC gains from increased plant biomass observed at earlier stages of N enrichment, potentially destabilizing long-term soil C sequestration.

a Critical thresholds of above- and belowground compartments and SOC. Values are mean values ± standard deviation (SD). Regressions of each variable and significant differences before and after the threshold (two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test) are presented in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7. Moving-window associations between biodiversity responses and SOC responses along N gradients for bacteria (b), fungi (c), and plants (d). Dots represent bootstrapped coefficients of the fixed effects within each subset window. The sign of each dot (relative to the zero line, where values > 0 indicate positive associations and values < 0 indicate negative associations) reflects whether biodiversity and SOC respond in the same (co-increase or co-decline) or in opposite directions. The slope of the fitted line indicates how biodiversity-SOC associations change across the N gradient: a positive slope suggests strengthening associations with increasing N input, whereas a negative slope suggests weakening or reversal. The dashed lines denote the nonlinear trend fitted by GAMs. Vertical dashed lines and inset numbers indicate N enrichment thresholds, and the solid lines represent the linear fits at both sides of each threshold. Significant differences between before and after the threshold are determined using a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test in Supplementary Fig. 8. Created in BioRender. Jiao, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/814s45u. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Moreover, we performed a moving-window analysis to evaluate the potential shifts in the associations between the responses of diversity and SOC with increasing N (Fig. 4b–d and Supplementary Fig. 8; all P < 0.001). The responses of bacterial diversity and SOC showed a slightly negative correlation below ~50 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ (Fig. 4b), indicating a transient non-causal association. At this stage, the increase in SOC may directly benefit from aboveground productivity (e.g., leaf litter and root exudates)80,81, while the decline in bacterial species may be functionally compensated by redundant taxa82. As N input exceeded this threshold, the association progressively became positive (reaching ~200 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹), marking a co-decline phase where intensified N enrichment suppressed both biodiversity and SOC. The response of fungal diversity fluctuated around ~67 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ but maintained a positive association with SOC across the N gradient (Fig. 4c), suggesting that fungi play a continuous and important role in SOC accumulation83. For example, certain ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi are capable of expressing oxidative enzymes that decompose recalcitrant organic matter84, while arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi may enhance MAOM formation through efficient hyphal turnover and microbial-derived pathways85,86. At low N inputs (<50 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹), plant diversity and SOC responses were negatively associated (Fig. 4d), reflecting a decoupled pattern where diversity loss driven by light competition and cation toxicity co-occurred with ongoing SOC accumulation24. Between 50 and 74 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, the association became strongly positive, indicating a shift toward synchronized biodiversity loss and slower or declining SOC gains. Above ~74 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, the positive association weakened, likely reflecting reduced plant-derived inputs as severe plant diversity loss constrained new C incorporation into soils17. Collectively, these results delineate a three-phase trajectory: low-N decoupling, mid-N synergy, and high-N functional breakdown. This trajectory underscores a mechanistic shift from N-stimulated C gains to biodiversity-governed constraints under saturation. Importantly, our results showed that the intermediate range (~50–74 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹) emerges as a potential co-benefits threshold for maintaining SOC accumulation without severe biodiversity loss. Overall, this context-dependent transition from synergy to trade-off underscores the complex and multifaceted consequences of biodiversity loss for SOC accumulation. Limiting N inputs to around 50 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ could help mitigate biodiversity loss and its negative effects on SOC storage, supporting long-term ecosystem stability.

Although we were able to collect a substantial dataset for this meta-analysis, research into joint effects of aboveground and belowground components on soil C dynamics is still in its infancy. First, SOC accumulation does not directly reflect long-term C accumulation potential, which is also influenced by decomposition rates, microbial metabolism, and environmental conditions. Second, while our soil microbes only included decomposers (bacteria and fungi), the potential influence of primary predators (nematodes and protists) and vertebrate control through trophic cascades on ecosystem C cycling under N enrichment have been overlooked, despite its recent identification as a significant factor in global C turnover87. Third, our study underrepresents Africa, South America, and Australia, potentially limiting the generalizability of the observed joint effects of N enrichment on biomass and soil C dynamics across biomes. Future studies should adopt factorial designs that independently manipulate biodiversity and N input (e.g., long-term crossed treatments), helping to disentangle causal effects from environmental confounding. Notwithstanding these challenges, our study provides robust global evidence that biodiversity, both aboveground and belowground, plays a pivotal role in regulating soil C stocks under N enrichment. Furthermore, we identified critical N thresholds that elucidate how above- and belowground systems alongside SOC respond simultaneously to N enrichment. These findings reveal key N input levels that balance biodiversity conservation and SOC accumulation, offering valuable evidence toward achieving a win-win scenario under N enrichment.

Overall, our study develops a series of N enrichment thresholds that identify the critical inflection points for biodiversity and SOC responses under N enrichment. By jointly analyzing how above- and belowground community diversity mediates soil carbon dynamics, our findings demonstrate that intensified N inputs can induce nonlinear shifts in biodiversity-carbon relationships from synergy to decoupling and eventual collapse. In particular, once the threshold (e.g., ~50 kg N ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹) is exceeded, the sharp decline in biodiversity may offset the potential benefits of SOC accumulation. This global meta-analysis simultaneously evaluates plant and microbial diversity in relation to SOC across diverse ecosystems, offering an integrated perspective on how multi-trophic biodiversity regulates biogeochemical responses to N enrichment. This knowledge enables more precise prediction of ecosystem carbon dynamics across diverse terrestrial biomes under future global changes, as aboveground and belowground responses are critical to maintaining and conserving ecosystem service. In doing so, the identification of actionable N input thresholds can inform sustainable N management strategies, delivering co-benefits for biodiversity conservation and long-term carbon retention.

Methods

Data collection

We constructed a global database to jointly investigate how SOC responses are influenced by changes in plant and soil microbial diversity to N enrichment, adhering to the PRISMA guidelines88 (Preferred Reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) (Supplementary Fig. 9). Peer-reviewed publications on the impacts of N enrichment on plant and soil microbial diversity in our study were searched using the Web of Science (https://webofscience.clarivate.cn/wos/woscc/basic-search) and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, https://www.cnki.net), including all research up to April 1, 2023 (a full list is provided in Supplementary Data 1). Keywords used were: “(nitrogen fertilization OR N deposition OR nitrogen addition OR N enrichment) AND (plant OR soil microbial) AND (richness) AND (SOC OR MBC OR plant biomass)”. We focused on diversity and biomass of plant and soil microbes as: (1) there is a significant knowledge gap regarding how their responses affect carbon allocation between plant and soil microbial biomass, and thus soil C storage under N enrichment; and (2) to provide a balanced dataset that considers both plant and soil microbes, as these variables are rarely measured simultaneously in studies.

Relevant publications were selected based on the following criteria: (1) N fertilizer was directly applied to terrestrial ecosystems under field conditions using paired treatment-control plots, excluding laboratory incubation studies. (2) At least one soil microbial phylotype related to diversity (richness), including bacteria and fungi, or biomass (MBC) was reported. (3) N application rate and experiment duration were recorded to standardize the effect of N enrichment across studies. (4) Means and sample sizes for the selected variables were available or could be calculated from the publications. Our search yielded a dataset of 2141 observations from 275 peer-reviewed studies (Fig. 1a, b), encompassing plant diversity and biomass, soil microbial diversity and biomass, SOC content, and associated climate and soil variables (Supplementary Table 1).

Extracted data

We collected plant and multiple soil variables, including plant species richness and biomass, soil microbial diversity and biomass, soil properties, and SOC from the selected publications. Numerical data were extracted from text, tables, figures, and appendices, whereas graphical data were digitized using GetData Graph Digitizer (http://getdata-graph-digitizer.com). Mean values, standard deviations (SD), and sample sizes (n) were recorded or calculated. When studies reported standard error (SE), it was converted to SD: \(\mathrm{SD}=\mathrm{SE}\times \sqrt{n}\). Climatic variables, including MAT and MAP, were obtained from Worldclim 2.0 (http://www.worldclim.org) based on study coordinates. Ecosystem types were categorized as farmland, forest, and grassland, and climatic regions as tropical (tropical and subtropical), temperate, and polar (polar and boreal), following the 2010 Global Ecological Zones dataset (https://data.apps.fao.org/). Here, we used richness (that is, the number of species) as a metric of diversity, as richness is the most used and simplest89,90. Accordingly, only studies reporting microbial richness were included. Due to prevalent monoculture practices in farmlands, land diversity data were largely unavailable and therefore not included. Soil microbial biomass was represented by MBC91. Soil properties (e.g., pH and moisture), nutrients (e.g., total N, total P, available N, and available P) and SOC were collected in the dataset. Detailed descriptions of all variables are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Since the analytical data were transformed into response ratios for subsequent analyses, any method-induced differences are considered negligible.

Data analyses

In this study, the natural logarithmic response ratio (lnRR), an effect size metric widely applied in meta-analysis, was used to evaluate the effect of N enrichment on each variable. The lnRR of an observation was calculated as follows:

Where \({X}_{T}\) and \({X}_{C}\) represent the mean values of response variables in the N treatment (T) and control (C), respectively. The N effect on soil pH was calculated as the difference between the treatment and control groups, as soil pH uses a logarithmic scale.

The weighted mean response ratio (\(\mathrm{ln}\overline{{\rm{RR}}}\)) for each group (e.g., ecosystem types, climate regions) was calculated as follows:

where m represents the number of observations in group, and \({w}_{i*}\) is the weighting factor of the ith observation in the group. The \({w}_{i*}\) was calculated as follows:

where \({v}_{i*}\) is the variance of study (i) in the group. The \({v}_{i*}\) was calculated as follows:

where \({v}_{i}\) is the within-study variance of study (i), and T2 is the between-studies variance. The \({v}_{i}\) was calculated as follows:

where SDT and SDC are the SD of the variables in the treatment and control treatments, respectively; nT and nC are the sample size in the treatment and control, respectively.

The SE of \(\mathrm{ln}\overline{{\rm{RR}}}\) was calculated as follows:

The 95% CI for \(\mathrm{ln}{\rm{RR}}\) was calculated as follows:

If the 95% CI does not overlap zero, the overall effect size of the N enrichment was significant92. For easier interpretation, the \({\mathrm{ln}}\,{\overline{{\rm{RR}}}}\) was back-transformed and expressed as a percentage change (%):

A mixed-effects model was employed to calculate the weighted mean of lnRR using the rma.mv function of the R package metafor93, with lnRR ID nested within study ID as the random effect. The distributions of lnRR for each variable analyzed in this study are presented in Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11. All statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.2.1.

Random forest model

We used random forest analysis to identify the primary predictors of plant and soil microbial diversity, biomass, and SOC responses94. Initially, we analyzed various environmental and biological variables to determine the key drivers of richness in plants, soil bacteria, and fungi. Given the pivotal role of diversity in influencing biomass, we incorporated diversity metrics into the original variables to identify the strongest predictors of plant and microbial biomass responses. Finally, we combined all environmental and biological variables, as well as diversity and biomass metrics from plants and soil microbial communities, to identify the main predictors of SOC response. The random forest models were implemented using the R package spatialRF95, which effectively reduces multicollinearity, captures key variable interactions, and evaluates model robustness through spatial cross-validation94. Before model fitting, we minimized multicollinearity by performing two steps: (1) correlation-based filtering (auto_cor function, |r| > 0.6) to remove highly correlated predictors, and (2) variance inflation factor filtering (auto_vif function, VIF > 2.5) to further exclude N-induced collinear variables. Predictor importance was assessed by measuring the average decrease in prediction accuracy (mean square error) when the data for a given predictor were permuted across trees. Due to the uneven distribution of data when incorporating both aboveground and belowground variables, and the inability of the random forest model to handle missing values, we included observations with at least seven available variables in the dataset used to identify key predictors96. This approach ensured robust representation and analytical reliability across all study observations (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). To accommodate missing data, values were imputed using the missForest function from the missForest package with the parameter ntree set to 99997.

Mixed-effects meta regression

Mixed-effects meta-regression models were used to examine the relationships between climatic and soil factors (identified through the random forest model) and plant, soil microbial communities, and SOC, using the rma.mv function in the R package metafor92. All models were fitted using inverse-variance weighting to account for differential contributions of each study98. Study ID was included as a random factor, and to account for potential non-independence among response variables arising from shared variance related to N enrichment, N rate level was also included as a random effect.

Threshold identification

In this study, we applied a two-step procedure based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to identify the most suitable model describing the relationship between the response of soil factors, diversity and biomass or SOC (y) and N enrichment rates (x), followed by previous studies42,43. First, we fitted linear and nonlinear models, including quadratic regressions (simple nonlinear trends) and generalized additive models (GAM, flexible trends using smoothing parameters)42,43. The linear model served as the null hypothesis, representing a gradual x-y relationship. Lower AIC values for nonlinear models indicated a threshold point, suggesting a departure from linear trends. In the second step, thresholds were tested only when nonlinear models demonstrated a better fit. Thresholds were categorized as either continuous or discontinuous. A continuous threshold marks a point of gradual slope change, often identified using GAM or segmented regressions, which capture points of maximum curvature. In contrast, discontinuous thresholds involve abrupt changes in both slope and intercept and are best modeled using step regressions or stegmented regressions (a combination of step and segmented approaches). Among segmented, step, and stegmented regressions, the model with the lowest AIC value was selected. If GAM was the best model, the segmented regression threshold was reported to highlight the point of maximum curvature. To ensure robustness, we removed outliers using the Mahalanobis distance method (cutoff >12) and restricted threshold searches to the 0.05–0.95 quantile range of x43. Each case underwent 1000 bootstrap resamplings to estimate plausible thresholds, with the mean threshold reported as the final value. We tested the significance of thresholds by bootstrapping linear regressions on either side of the threshold and comparing slopes using a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test. Threshold detection revealed significant differences in slopes in nearly all cases where nonlinear regressions provided a better fit. All models were implemented using the chngpt99 and gam100 packages in R.

Moving-window analysis

We evaluated how the relationships between diversity and SOC in plant and soil microbial communities change along gradients of N enrichment using a moving-window approach. Linear mixed-effects models were applied to successive subsets of paired diversity–SOC observations, beginning with the lowest N enrichment values and iteratively shifting the window by one observation until the window limit was reached, with study ID included as a random factor101. Following previous studies102,103, the window size was set to 20 observations. For each subset, standardized coefficients of diversity with N rates were bootstrapped and aligned with the average N rate value of the subset101. Linear and nonlinear regressions were then used to identify N rate thresholds, with their validity tested using the methods outlined above.

Global distribution of above- and belowground biomass under N enrichment

Global data collection

Using the important predictors identified by the random forest models, we generated global spatial predictions for the responses of plant biomass, MBC, and SOC under N enrichment. In the absence of global N enrichment data, we substituted N deposition rates from Ackerman et al. for the global map values to represent N availability66. Plant diversity data were sourced from Cai et al. (https://gift.uni-goettingen.de/shiny/predictions)104. Soil biodiversity data from the project of Global Soil Biodiversity Atlas (https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/content/global-soil-biodiversity-atlas) were used as a proxy for soil microbial diversity. Climatic variables were obtained from Worldclim 2.0 (http://www.worldclim.org) based on location data. Soil properties such as pH and total N (TN) were extracted from SoilGrids (http://www.isric.org/explore/soilgrid). All covariate map layers were resampled and reprojected to a unified 0.25°-pixel grid in EPSG:4326 (WGS84). Higher-resolution layers were down-sampled using mean aggregation, while lower-resolution layers were up-sampled without interpolation to match the grid.

Prediction validation

We applied a random forest model to upscale site-level responses of plant biomass, MBC, and SOC under N enrichment to the regional scale, considering contemporary climate scenarios. Each tree in the model was trained on a randomly selected subset of data, with out-of-bag data used to estimate prediction error and variable importance105. Validation against observed data yielded Pearson’s r values of 0.54, 0.58, and 0.52 for plant biomass, MBC, and SOC, respectively (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 14). The random forest training was repeated 1000 times, and the average predictions from these iterations were taken as the final variable estimates. All random forest computations were performed using the RandomForestRegressor function in the scikit-learn package in Python version 3.7106. The potential effects of global N deposition on these variables were then spatially extrapolated for each pixel using model parameters and the selected variables. Extrapolation and geospatial analyses were conducted in Python version 3.7 and ArcGIS version 10.4.1107,108. Prediction uncertainty for the global estimates was quantified as the 95% CIs (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Publication bias

To assess potential bias in our collected dataset, we employed three independent approaches. First, we utilized a funnel plot to visually examine the possibility of bias (Supplementary Fig. 16). To quantitatively test for asymmetry in the funnel plot, we applied Egger’s regression test109 (Supplementary Table 2). In cases where asymmetry was detected, we used the Rosenberg fail-safe number (Nfs) to determine the extent to which unpublished studies might influence our conclusions110. If the Nfs is larger than 5k + 10 (k, number of study observations) (Supplementary Table 2), the results are robust regardless of any potential publication bias. Lastly, we evaluated the robustness of our results by performing a leave-one-out analysis using the leave1out function111 (Supplementary Fig. 17). These findings indicate that publication bias is unlikely to affect the interpretation of our results.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed in this study have been deposited in the figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30646841). Supplementary Data 1 contains the full citation information for all primary studies included in the meta-analysis. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The main R code used in this study is available at the figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30646841).

References

Amelung, W. et al. Towards a global-scale soil climate mitigation strategy. Nat. Commun. 11, 5427 (2020).

Lehmann, J., Bossio, D. A., Kögel-Knabner, I. & Rillig, M. C. The concept and future prospects of soil health. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 544–553 (2020).

Ling, J. et al. Soil organic carbon thresholds control fertilizer effects on carbon accrual in croplands worldwide. Nat. Commun. 16, 3009 (2025).

Yang, X. et al. Nitrogen addition promotes soil carbon accumulation globally. Sci. China Life Sci. 68, 284–293 (2025).

Galloway, J. N. et al. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 320, 889–892 (2008).

Hiis, E. G. et al. Unlocking bacterial potential to reduce farmland N2O emissions. Nature 630, 421–428 (2024).

Ye, C. et al. Reconciling multiple impacts of nitrogen enrichment on soil carbon: plant, microbial and geochemical controls. Ecol. Lett. 21, 1162–1173 (2018).

Lu, X. et al. Nitrogen addition stimulates soil aggregation and enhances carbon storage in terrestrial ecosystems of China: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 2780–2792 (2021).

Tang, B., Rocci, K. S., Lehmann, A. & Rillig, M. C. Nitrogen increases soil organic carbon accrual and alters its functionality. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 1971–1983 (2023).

Feng, X. et al. Nitrogen input enhances microbial carbon use efficiency by altering plant-microbe-mineral interactions. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 4845–4860 (2022).

Neff, J. C. et al. Variable effects of nitrogen additions on the stability and turnover of soil carbon. Nature 419, 915–917 (2002).

Mack, M. C., Schuur, E. A., Bret-Harte, M. S., Shaver, G. R. & Chapin, F. S. Ecosystem carbon storage in arctic tundra reduced by long-term nutrient fertilization. Nature 431, 440–443 (2004).

Janssens, I. A. et al. Reduction of forest soil respiration in response to nitrogen deposition. Nat. Geosci. 3, 315–322 (2010).

Lange, M. et al. Plant diversity increases soil microbial activity and soil carbon storage. Nat. Commun. 6, 6707 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Microbial diversity losses constrain the capacity of soils to mitigate climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17601 (2024).

Cardinale, B. J. et al. Effects of biodiversity on the functioning of trophic groups and ecosystems. Nature 443, 989–992 (2006).

Hooper, D. U. et al. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature 486, 105–108 (2012).

Angst, S., Angst, G., Mueller, K. E., Lange, M. & Eisenhauer, N. Un(der)explored links between plant diversity and particulate and mineral-associated organic matter in soil. Nat. Commun. 16, 5548 (2025).

Liang, C., Schimel, J. P. & Jastrow, J. D. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17105 (2017).

Sokol, N. W. et al. Life and death in the soil microbiome: how ecological processes influence biogeochemistry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 415–430 (2022).

Domeignoz-Horta, L. A. et al. Microbial diversity drives carbon use efficiency in a model soil. Nat. Commun. 11, 3684 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Nitrogen fertilization weakens the linkage between soil carbon and microbial diversity: a global meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 6446–6461 (2022).

Simkin, S. M. et al. Conditional vulnerability of plant diversity to atmospheric nitrogen deposition across the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4086–4091 (2016).

Namuhan et al. Mechanisms of biodiversity loss under nitrogen enrichment: unveiling a shift from light competition to cation toxicity. New Phytol. 243, 1966–1979 (2024).

Tian, Q. et al. An integrated belowground trait-based understanding of nitrogen-driven plant diversity loss. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 3651–3664 (2022).

Band, N., Kadmon, R., Mandel, M. & DeMalach, N. Assessing the roles of nitrogen, biomass, and niche dimensionality as drivers of species loss in grassland communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2112010119 (2022).

Wang, X. D. et al. Globally nitrogen addition alters soil microbial community structure, but has minor effects on soil microbial diversity and richness. Soil Biol. Biochem. 179, 108982 (2023).

Fierer, N. et al. Comparative metagenomic, phylogenetic and physiological analyses of soil microbial communities across nitrogen gradients. ISME J. 6, 1007–1017 (2012).

Yu, Q. et al. Decoupled responses of plants and soil biota to global change across the world’s land ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 15, 10369 (2024).

Loreau, M. & Hector, A. J. N. Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature 412, 72–76 (2001).

Hu, J., Huang, C., Zhou, S. & Kuzyakov, Y. Nitrogen addition to soil affects microbial carbon use efficiency: meta-analysis of similarities and differences in 13C and 18O approaches. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 4977–4988 (2022).

Liu, W., Qiao, C., Yang, S., Bai, W. & Liu, L. Microbial carbon use efficiency and priming effect regulate soil carbon storage under nitrogen deposition by slowing soil organic matter decomposition. Geoderma 332, 37–44 (2018).

Weiskopf, S. R. et al. Biodiversity loss reduces global terrestrial carbon storage. Nat. Commun. 15, 4354 (2024).

Liu, H. Y., Huang, N., Zhao, C. M. & Li, J. H. Responses of carbon cycling and soil organic carbon content to nitrogen addition in grasslands globally. Soil Biol. Biochem. 186, 109164 (2023).

Schuldt, A. et al. Carbon-biodiversity relationships in a highly diverse subtropical forest. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 5321–5333 (2023).

Zhu, L. et al. Regional scalable priorities for national biodiversity and carbon conservation planning in Asia. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe4261 (2021).

Soto-Navarro, C. et al. Mapping co-benefits for carbon storage and biodiversity to inform conservation policy and action. Philos. T. R. Soc. B 375, 20190128 (2020).

Fornara, D. A. & Tilman, D. Soil carbon sequestration in prairie grasslands increased by chronic nitrogen addition. Ecology 93, 2030–2036 (2012).

Zhou, T., Wang, C. K. & Zhou, Z. H. Nitrogen availability regulates tree mixture effects on soil organic carbon in temperate forests: insights from a meta-analysis and long-term experiment. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 34, e70073 (2025).

Shi, T. S. et al. A global meta-analysis on the effects of organic and inorganic fertilization on grasslands and croplands. Nat. Commun. 15, 3411 (2024).

Xia, L. L. et al. Trade-offs between soil carbon sequestration and reactive nitrogen losses under straw return in global agroecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 5919–5932 (2018).

Berdugo, M. et al. Global ecosystem thresholds driven by aridity. Science 367, 787–790 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Water availability creates global thresholds in multidimensional soil biodiversity and functions. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1002–1011 (2023).

Pan, H. et al. Aridity threshold induces abrupt change of soil abundant and rare bacterial biogeography in dryland ecosystems. mSystems 7, e0130921 (2022).

Egidi, E., Coleine, C., Delgado-Baquerizo, M. & Singh, B. K. Assessing critical thresholds in terrestrial microbiomes. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 2230–2233 (2023).

Frantzeskakis, L. et al. Rapid evolution in plant–microbe interactions–a molecular genomics perspective. New Phytol. 225, 1134–1142 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Divergent phenological responses of soil microorganisms and plants to climate warming. Nat. Geosci. 18, 753–760 (2025).

Hodge, A., Robinson, D. & Fitter, A. Are microorganisms more effective than plants at competing for nitrogen? Trends Plant Sci. 5, 304–308 (2000).

Lavallee, J. M., Soong, J. L. & Cotrufo, M. F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 261–273 (2020).

Midolo, G. et al. Impacts of nitrogen addition on plant species richness and abundance: a global meta-analysis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 28, 398–413 (2019).

Han, Y. F., Feng, J. G., Han, M. G. & Zhu, B. Responses of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to nitrogen addition: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 7229–7241 (2020).

Ma, X. C. et al. Global negative effects of nutrient enrichment on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, plant diversity and ecosystem multifunctionality. New Phytol. 229, 2957–2969 (2021).

Morrison, E. W. et al. Chronic nitrogen additions fundamentally restructure the soil fungal community in a temperate forest. Fungal Ecol. 23, 48–57 (2016).

Branco, S., Schauster, A., Liao, H. L. & Ruytinx, J. Mechanisms of stress tolerance and their effects on the ecology and evolution of mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 235, 2158–2175 (2022).

Zavaleta, E. S., Shaw, M. R., Chiariello, N. R., Mooney, H. A. & Field, C. B. Additive effects of simulated climate changes, elevated CO2, and nitrogen deposition on grassland diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 7650–7654 (2003).

Wang, C. Q. & Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial-fungal competition for soil resources. ISME J. 18, wrae073 (2024).

Hu, Z. et al. Nutrient-induced acidification modulates soil biodiversity-function relationships. Nat. Commun. 15, 2858 (2024).

He, Y. C. et al. Water controls the divergent responses of terrestrial plant photosynthesis under nitrogen enrichment. J. Ecol. 112, 2638–2651 (2024).

Bai, Y. F. & Cotrufo, M. F. Grassland soil carbon sequestration: current understanding, challenges, and solutions. Science 377, 603–608 (2022).

Brown, J. H., Gillooly, J. F., Allen, A. P., Savage, V. M. & West, G. B. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 85, 1771–1789 (2004).

Tian, D. H., Wang, H., Sun, J. & Niu, S. L. Global evidence on nitrogen saturation of terrestrial ecosystem net primary productivity. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 024012 (2016).

Maestre, F. T. et al. Increasing aridity reduces soil microbial diversity and abundance in global drylands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15684–15689 (2015).

Carpenter, D. N., Bockheim, J. G. & Reich, P. F. Soils of temperate rainforests of the North American Pacific Coast. Geoderma 230, 250–264 (2014).

Machmuller, M. B. et al. Arctic soil carbon trajectories shaped by plant-microbe interactions. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 1178–1185 (2024).

Xia, J. & Wan, S. Global response patterns of terrestrial plant species to nitrogen addition. New Phytol. 179, 428–439 (2008).

Ackerman, D., Millet, D. B. & Chen, X. Global estimates of inorganic nitrogen deposition across four decades. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 33, 100–107 (2019).

He, C., Ruan, Y. & Jia, Z. Effects of nitrogen addition on soil microbial biomass: a meta-analysis. Agriculture 14, 1616 (2024).

Treseder, K. K. Nitrogen additions and microbial biomass: a meta-analysis of ecosystem studies. Ecol. Lett. 11, 1111–1120 (2008).

Forstner, S. J. et al. Vertical redistribution of soil organic carbon pools after twenty years of nitrogen addition in two temperate coniferous forests. Ecosystems 22, 452–452 (2019).

Tian, J. et al. Long-term nitrogen addition modifies microbial composition and functions for slow carbon cycling and increased sequestration in tropical forest soil. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 3267–3281 (2019).

Zhou, Z., Wang, C. & Luo, Y. Meta-analysis of the impacts of global change factors on soil microbial diversity and functionality. Nat. Commun. 11, 3072 (2020).

Meng, C. et al. Global soil acidification impacts on belowground processes. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 074003 (2019).

Kong, W. et al. Climate and soil pH modulate global negative effects of nitrogen enrichment on soil nematodes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 208, 109860 (2025).

Domeignoz-Horta, L. A. et al. Plant diversity drives positive microbial associations in the rhizosphere enhancing carbon use efficiency in agricultural soils. Nat. Commun. 15, 8065 (2024).

Strassburg, B. B. et al. Global congruence of carbon storage and biodiversity in terrestrial ecosystems. Conserv. Lett. 3, 98–105 (2010).

Thomas, C. D. et al. Reconciling biodiversity and carbon conservation. Ecol. Lett. 16, 39–47 (2013).

Nielsen, U. N., Ayres, E., Wall, D. H. & Bardgett, R. D. Soil biodiversity and carbon cycling: a review and synthesis of studies examining diversity–function relationships. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 62, 105–116 (2010).

Zhao, M. et al. Decoupled responses of above- and below-ground beta-diversity to nitrogen enrichment in a typical steppe. Ecol. Lett. 27, e14339 (2024).

Genre, A., Lanfranco, L., Perotto, S. & Bonfante, P. Unique and common traits in mycorrhizal symbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 649–660 (2020).

Forsmark, B. et al. Anthropogenic nitrogen enrichment increased the efficiency of belowground biomass production in a boreal forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 155, 108154 (2021).

Hyvönen, R. et al. Impact of long-term nitrogen addition on carbon stocks in trees and soils in northern Europe. Biogeochemistry 89, 121–137 (2008).

Allison, S. D. & Martiny, J. B. Colloquium paper: resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11512–11519 (2008).

Li, T. et al. Mycorrhizal allies: synergizing forest carbon and multifunctional restoration. Trends Ecol. Evol. 40, 983–994 (2025).

Auer, L. et al. Metatranscriptomics sheds light on the links between the functional traits of fungal guilds and ecological processes in forest soil ecosystems. New Phytol. 242, 1676–1690 (2024).

Kakouridis, A. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhiza convey significant plant carbon to a diverse hyphosphere microbial food web and mineral-associated organic matter. New Phytol. 242, 1661–1675 (2024).

Wu, S. L. et al. Soil organic matter dynamics mediated by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi - an updated conceptual framework. New Phytol. 242, 1417–1425 (2024).

Tuo, B. et al. Meta-analysis reveals that vertebrates enhance plant litter decomposition at the global scale. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 411–422 (2024).

Takkouche, B. & Norman, G. J. E. PRISMA statement. 22, 128 (2011).

Fan, K. et al. Soil biodiversity supports the delivery of multiple ecosystem functions in urban greenspaces. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 113–126 (2023).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Multiple elements of soil biodiversity drive ecosystem functions across biomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 210–220 (2020).

Liu, S. W. et al. Response of soil carbon dioxide fluxes, soil organic carbon and microbial biomass carbon to biochar amendment: a meta-analysis. GCB Bioenergy 8, 392–406 (2016).

Liu, T. et al. Forest canopy maintains the soil community composition under elevated nitrogen deposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 143, 107733 (2020).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48 (2010).

Sáez-Sandino, T. et al. The soil microbiome governs the response of microbial respiration to warming across the globe. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1382–1387 (2023).

Benito, B. M. spatialRF: Easy Spatial Regression with Random Forest Measurement (R package version,2021).

Pelletier, T. A., Carstens, B. C., Tank, D. C., Sullivan, J. & Espíndola, A. Predicting plant conservation priorities on a global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 13027–13032 (2018).

Stekhoven, D. J. & Bühlmann, P. MissForest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 28, 112–118 (2012).

Lee, C. H., Cook, S., Lee, J. S. & Han, B. Comparison of two meta-analysis methods: inverse-variance-weighted average and weighted sum of Z-scores. Genom. Inform. 14, 173–180 (2016).

Fong, Y. Y., Huang, Y., Gilbert, P. B. & Permar, S. R. chngpt: threshold regression model estimation and inference. BMC Bioinform. 18, 454 (2017).

Hastie, T. gam: Generalized additive models. R package version 1.20 (2020).

Hu, W. et al. Aridity-driven shift in biodiversity-soil multifunctionality relationships. Nat. Commun. 12, 5350 (2021).

Silva, J. F. Jr. et al. Multivariate split moving windows and magnetic susceptibility for locating soil boundaries of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Geoderma Reg. 26, e00418 (2021).

Jiao, S., Lu, Y. H. & Wei, G. H. Soil multitrophic network complexity enhances the link between biodiversity and multifunctionality in agricultural systems. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 140–153 (2022).

Cai, L. et al. Global models and predictions of plant diversity based on advanced machine learning techniques. New Phytol. 237, 1432–1445 (2023).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Abraham, A. et al. Machine learning for neuroimaging with scikit-learn. Front. Neuroinform. 8, 14 (2014).

Childs, C. Interpolating surfaces in ArcGIS spatial analyst. ArcUser 3235, 32–35 (2004).

Lawhead, J. Learning Geospatial Analysis with Python (Packt Publishing Ltd, 2013).

Egger, M. atthias, Martin Schneider, G. D. S. & Minder, C. hristoph Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 316, 629–634 (1997).

Rosenberg, M. S. The file-drawer problem revisited: a general weighted method for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis. Evolution 59, 464–468 (2005).

Wong, T. T. Performance evaluation of classification algorithms by k-fold and leave-one-out cross validation. Pattern Recognit. 48, 2839–2846 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number: 2021YFD1900500; S.J.), National Science Foundation of China (grant number: 42477129; S.J.), and National Science Foundation for Excellent Young Scholars of China (grant number: 42122050; S.J.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J. and H.P. conceived the ideas and designed the methodology. H.P., Y.H., W.W., and S.L. contributed to the literature inclusion and data collection. H.P. performed the analyses and wrote the original draft. S.J. and G.W. reviewed the paper before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, H., Hui, Y., Wu, W. et al. Critical thresholds for co-benefits of carbon accumulation and biodiversity conservation under global nitrogen enrichment. Nat Commun 17, 1336 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68090-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68090-9