Abstract

Cells of the retina, photoreceptors especially, are highly metabolically active with substantial energy requirements. Accordingly, the effective delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the retina via the retinal vasculature is key to tissue function. Indeed, a disturbed retinal blood supply, especially if prolonged, can result in a loss of vision. Vascular endothelial cells, which form the inner lining of blood vessels, are pivotal in ensuring a healthy blood circulation in many tissues, including the light-sensitive retina at the back of the eye. However, the mechanism by which vascular endothelial cells maintain a functional retina (and aid the healing of a damaged one) is not understood. Here, through single-cell RNA sequencing, colony-forming assays and lineage tracing analysis, we provide data that point to a new regulatory system by which vascular endothelial cells are supplied to the retina by a reservoir of stem/progenitor cells in the optic nerve.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coordinated somatic stem cell activities are central to the homeostasis of tissues that turn over1,2. Indeed, in epithelial, hematopoietic, vascular and nervous systems, homeostatic remodeling by the stem cell system occurs at different time points and at different speeds in response to various chronic external or internal stresses3,4,5,6. During acute injury, stem cells are activated and tissue repair occurs, however, if a stem cell system becomes dysfunctional, disease invariably develops due to failed remodeling7,8.

Endothelial cells from different tissues possess unique transcriptional patterns, often clustering into organ-specific subtypes as has been demonstrated by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)9,10. Some studies have suggested that resident endothelial stem cells underpin vascular healing and renewal11,12,13, however, the existence or not of vascular endothelial cell progenitors remains a matter of debate.

As the innermost layer of the eye, the light-sensitive retina is essential for vision. However, owing to the high energy expenditure of cells of the retina—which has a metabolic rate surpassing that of the brain—a restricted supply of oxygen and nutrients caused by a disrupted blood supply can deleteriously affect vision. Indeed, the ischemic retinopathies, such as diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity and retinal vein occlusion, are primary causes of vision loss14,15. As well as providing oxygen and nutrients, the retinal vasculature also plays a key role directing immune cell movement and upholding tissue balance16,17. By virtue of their role lining the inside of retinal blood vessels, endothelial cells are instrumental in maintaining tissue homeostasis and also for enabling angiogenesis, a process that creates new blood vessels from existing ones18,19. Here, we report a prominent population of retinal vascular endothelial stem cells (VESCs) in the optic nerve that not only supply endothelial cells to the retina under homeostatic conditions but are also active in vascular healing, being rapidly recruited to repair damaged blood vessels.

Results

Endothelial stem cells in the optic nerve

In the murine eye, the ophthalmic artery traverses the orbital space, advancing towards the scleral portion of the eye, with the central retinal vein situated closer to the optic nerve20 (Fig. 1a). As previously reported, retinal and optic nerve flat-mount staining for PECAM1(CD31, pan-endothelial marker) shows that the central retinal vein is embedded into the retina along the optic nerve (Fig. 1b). To explore retinal endothelial stem/progenitor cells, we first focused on cell surface antigens CD157 and CD201 as markers of endothelial progenitors12,13. In order to confirm whether endothelial progenitor cells exist in retinal blood vessels, CD45negCD31+ endothelial cells were sorted (Fig. 1c–e). From this it was found that about 1 to 2% of CD157+ cells were seen in the retina, which is a lower proportion than the approximately 5% often seen in other organs12 (Fig. 1f). A wider analysis disclosed that CD157+ or CD201+ cells derived from retinal vessels and the optic nerve were present at levels exceeding 5% (Fig. 1g), and that the optic nerve itself harbored more than 20% of CD157+ or CD201+ endothelial progenitors (Fig. 1h and i). CD157+ or CD201+ cells were also present in the central retinal vein (Fig. 1j and k). When the clonal expansion potential of endothelial cells in the retina and optic nerve was compared, colony-forming assays using CD45negCD31+ cells from adult mice revealed that endothelial cells from optic nerve generated more endothelial cells (Fig. 1l and m). Moreover, the cells that expressed both CD157 and CD201 markers demonstrated characteristics of endothelial colony-forming cells, unlike CD157+CD201neg, CD157negCD201+ and CD157negCD201neg cells (Fig. 1n and o).

a Diagram illustrating the connection between the retina and the optic nerve. b Flat-mount immunostaining for CD31 on retina and optic nerve (8-week-old C57Bl6J mouse). Half of the retina has been removed. c–e Flow cytometric analysis of CD45negCD31+ endothelial cells (ECs) in retina, retina plus optic nerve (ON) and ON. f–h Flow cytometric analysis for CD201 and CD157 in ECs from (c–e, respectively). i Quantification of percentage of CD157+ ECs, CD201+ECs and CD157+ CD201+ ECs from (f–h). Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments (each using 3 mice per experiment) and displayed as mean ± SD. j Immunostaining for CD31 (green) and CD157 (red) and staining with DAPI (blue) in ON section from 8-week-old C57Bl6J mice. Four mice were used in this experiment. k Immunostaining for CD31 (green) and CD201 (red) and staining with DAPI (blue) in ON sections from 8-week-old C57Bl6J mice. l, m Colony forming assay using ECs form retina or ON. Immunostaining for CD31 (green) and with phalloidin (red) and DAPI (blue) (l). ECs from ON potentiate, producing more ECs (m). Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments (each using 10 mice per experiment) and displayed as mean ± SEM. n, o Colony forming assay using CD157+/neg CD201+/neg ECs. Immunostaining for CD31 (green) and staining with phalloidin (red) and DAPI (blue) (n). Quantification of colony forming assay demonstrates CD157+ CD201+ ECs from retina plus ON potentiate, producing more ECs (o). Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments (each using 20 mice per experiment) and displayed as mean ± SEM. p Illustrative representation of the approach for FACS analysis of cultured endothelial colony-forming cells originating from CD157 + CD201+ ECs. q Re-analysis of ECs from colony-forming assays shows that the majority of cells in colonies formed by CD157+CD201+ VESCs were composed of CD157negCD201+ endothelial cells or CD157negCD201neg endothelial cells. Hearts or livers from two mice were used in this experiment. r Diagrammatic illustration of the hierarchical model of vascular endothelial cells in the retina. Significance was determined using two-tailed unpaired t test in m and a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test in (i, o). Each image are from representative of at least two independent experiments. Scale bars, 100 μm (500 μm in b).

To better understand the hierarchy of vascular endothelial cells below VESCs, we re-analyzed endothelial colony-forming cells derived from CD157 + CD201+ endothelial cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Fig. 1p). Because insufficient numbers of endothelial cells could be obtained from the optic nerve for FACS analysis, we used liver and heart, which have favorable colony-forming capabilities and similar CD157 + CD201 + VESC fractionation rates to those in retina plus optic nerve. The analysis revealed that CD157+CD201neg cells formed less than 5% of colonies, CD157negCD201+ cells formed 20-30% and CD157negCD201neg cells formed 40–70% (Fig. 1q). This suggests a hierarchical structure, with CD157 + CD201+VESCs upstream and CD157neg CD201+ECs and CD157negCD201neg ECs located downstream (Fig. 1r).

Retinal vascular endothelial cells exist in the optic nerve in homeostatic conditions

The 3’ and 5’ ends of RNA of sorted retinal endothelial cells, defined as CD45negCD31+ cells from 8-week-old mice, were studied by scRNA-seq21. A total of 44,358 endothelial cells from “retina only” and from “retina plus optic nerve” were analyzed (Fig. 2a), identifying multiple endothelial clusters contaminated by a small fraction of photoreceptor cells, Müller cells, bipolar cells and monocytes (Fig. 2b). Within endothelial populations, distinct clusters were detected that express Bst1 [CD157] and Procr [CD201] (Fig. 2c) and were located upstream of cell differentiation (Fig. 2d). These are assumed to represent a VESC subpopulation (Fig. 2d). Subpopulations highly expressing Bst1 also expressed Lrg1, which is a regulator of angiogenesis (Fig. 2c)22 along with other genes and pathways (Supplementary Fig S1a and b). The velocity analysis (Fig. 2d) and pseudotime analysis (Fig. 2e) suggest a differentiation trajectory where Bst1-low endothelial cells might emerge from Procr-positive or Bst1-positive cells (Fig. 2d and e). Moreover, VESC candidate clusters highly expressing Bst1 (clusters 6 and 10) were abundantly included in endothelial cells collected from the retina plus optic nerve (Fig. 2f–h). Transcription factors such as Atf3, Irf1 and Stat3 were more highly expressed in cluster 10 than in the other clusters (Fig. 2i). Atf3-binding motif was enriched in transcribed candidate enhancer regions of cluster 10 (Supplementary Fig. S1c).

a Schematic diagram of the strategy for 3′ and 5′ scRNA-seq for sorted ECs (CD45negCD31+) from retina or retina plus optic nerve. Experiments using 10 mice were pooled three times and analyzed. b A uniform manifold approximation (UMAP) of ECs identified by scRNA-seq of sorted 44,358 total (retina and retina plus optic nerve) cells (CD45negCD31+) at 8-weeks of age. Batch corrections were performed by Harmony. c UMAPs of the levels of gene expression (Pecam1 [CD31], Bst1 [CD157], Procr [CD201] and Lrg1. d Velocity estimate projected onto UMAP demonstrating a directionality of RNA dynamics. e UMAP projection of endothelial cluster colored by RNA velocity–derived pseudotime (0 = early, 1 = late) as computed with scVelo, demonstrating a continuous progression along the inferred cellular trajectory. f mRNA levels of Bst1 [CD157] in vascular endothelial cluster in cells from retina only (left) and retina plus optic nerve (right). A distinct Bst1 positive population was present through integration of the optic nerve into the retina. g Distribution of the percentage of Bst1 positive cells in each cluster. h Bar plots of the fractions of cells form retina or retina plus optic nerve in all cells (top), cluster 10 (middle) and Bst1 positive cells in cluster 10 (bottom), respectively. *p = 7.308e-09, **p < 2.2e-16 by two-sided Fisher’s exact test. i Scatter plot of average expression (x‑axis) versus log₂ fold change (y‑axis) for genes upregulated in cluster 10. Predicted transcription factors are colored, with Atf3, Irf1 and Stat3 (logFC > 1) highlighted in red. Highly expressed marker genes—including Lrg1, Mctp1 and Ptgs2—are labeled, and the Atf3‑binding motif sequence logo is overlaid at the top left. Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. P-values were adjusted with the Bonferroni correction.

To identify CD157 + CD201+ endothelial cells and mark their location, Procr [CD201]-CreERT2 mice were crossed with a floxed tdTomato reporter strain (Fig. 3a). Two days after a single tamoxifen injection into 8-week-old mice, tdTomato expression was predominant in vessels of the optic nerve. Seven days after the injection, tdTomato-positive CD31+ cells were also observed in the veins of the central retina and at 14 days in mid-peripheral retinal vessels too. After two months, tdTomato-positive cells were present mainly in the optic nerve vessels rather than the retinal veins (Fig. 3b and c). These data suggest that tdTomato‑labeled cells undergo reverse migration—migrating against the direction of blood flow17—to traverse from veins to arteries via the capillary network (Fig. 3d).

a Schematic diagram of the strategy for tamoxifen administration and lineage tracing for Procr[CD201];CreERT2-tdTomato mice at indicated time points. b Flat-mount confocal microscopic analysis of retina and optic nerve for td-Tomato combined with CD31 and DAPI staining. The time course was examined for homeostatic condition at 2, 7, 14, 28 days post-tamoxifen injection (dpi) and 2 months post-injection (Mpi) in optic nerve, central retina and mid-peripheral retina of 8-week-old mice. Bar indicates 50 µm. c Quantification of tdTomato+CD31+ ECs in optic nerve, artery or vein and in the central and mid-peripheral retina at 2 (n = 5), 7 (n = 4), 14 (n = 4) and 28 (n = 4) days and 2 months (n = 6) post-tamoxifen injection. Data were from at least four mice for each tracing time point and lines are presented as median. Each image are from representative of at least two independent experiments. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. d Schematic illustration of the proposed tdTomato labeled cells migration from optic nerve.

Endothelial stem cells help repair the retinal vasculature

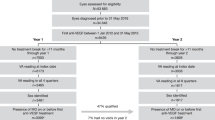

To interrogate the mechanism of vascular repair and ascertain if damaged vessels are formed by endothelial stem/progenitor cells, a mouse vascular injury model (oxygen induced retinopathy; OIR) was studied. In this, mice are placed under hyperoxic conditions at P7 to induce ischemic retinopathy and the shedding of blood vessels. A return to normal oxygen conditions (normoxia) at P12 results in neovascularization peaking at P17, with a recovery to normal by P3023,24. CD45negCD31+ retinal endothelial cells at P12 (ischemic phase), P17 (retinopathy phase) and P25 (vascular repair phase) were collected from retina only or retina plus optic nerve (six samples) and analyzed along with six control specimens (Fig. 4a). When combining all 12 samples, the scRNA-seq analysis identified seven endothelial cell clusters contaminated by a small fraction of photoreceptor cells and so on (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. S2a). Pglyrp1, reported to be specific to brain endothelial cells9, was highly expressed in all clusters except cluster 4, which appeared to consist of photoreceptors rather than endothelial cells (Supplementary Fig. S2b). In the combined retina plus optic nerve samples, cluster 1 was enriched for endothelial stem cell populations (Fig. 4c). This cluster was also abundantly represented among endothelial cells collected from the retina plus optic nerve at P12, P17, and P25 (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. S2c). Based on the results of the colony-forming assays shown in Fig. 1n, retinal endothelial cells were divided into four fractions: Bst1 [CD157]+Procr [CD201]+; Bst1neg Procr + ; Bst1+Procr neg; Bst1 neg Procr neg. An analysis of these indicated that more Bst1+ Procr+ endothelial cells were present, especially in cluster 1 of the combined retina plus optic nerve samples. Moreover, copious Bst1 neg Procr+ endothelial cells were found at P17 and P25 in retinal samples taken from mice with a retinal vascular injury (Fig. 4e).

a Schematic diagram of the strategy for scRNA-seq for sorted endothelial cells (CD45negCD31+) of retina (Retina) or retina plus optic nerve (Retina + ON) from a total of twelve injury model samples at P12, P17 and P25 and their respective controls. Samples from 10 mice were pooled in three independent experiments for analysis. b UMAP plot of the integrated scRNA-seq data from CD45negCD31+ vascular endothelial cells sorted from twelve samples, showing distinct endothelial cell subpopulations. c Feature plot showing the expression of Bst1 (CD157). d Comparisons between the Retina and Retina+ON groups at P12, P17, and P25 under both control and OIR conditions. Stacked bar charts show that cells in cluster 1 were significantly more abundant in Retina+ON than in Retina, at all three time points, except P12 control. e Proportion of Bst1+/neg Procr+/neg endothelial cells in each sample. The proportion of Bst1negProcr+ vascular endothelial cells was increased in the retina and ReON samples at P17 and P25. Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided Fisher’s exact test. OIR, oxygen-induced retinopathy. ON, optic nerve. ReON, Retina+optic nerve.

Hierarchy of endothelial cells in retinal/optic nerve vasculature

To examine the role of CD201+ endothelial cells in vascular repair, we again studied Procr-CreERT2-tdTomato reporter mice in OIR model and its physiological control (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. S3a–d). An injection of tamoxifen at P12 was used to determine the involvement of marked VESCs in vascular repair. This indicated that one day after tamoxifen injection (P13), only a few CD201+ endothelial cells marked by tdTomato in the retina were present in the OIR model (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. S3c), whereas a substantial number of CD201+ endothelial cells marked by tdTomato were found in optic nerve vessels. At P15, tdTomato-positive cells were present on the optic nerve side of the large veins but not in peripheral side in the retina (Supplementary Fig. S3d), whilst at P17, they were seen in all of the large veins in the retina. Furthermore, at P28, most of the reconstructed blood vessels consisted of tdTomato-positive cells (Fig. 5b and c). In addition, it was also shown that the blood vessels reconstructed by tdTomato-positive cells improved ischemia and were functional (Supplementary Fig. S4a). These results suggest that endothelial progenitors residing in the optic nerve play a pivotal role in the restoration of retinal blood vessels (control data is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2b). To clarify if the tdTomato-positive cells were CD201+ cells or were derived from CD201+ cells, FACS analysis was performed. In the OIR model at P28 when the blood vessels are undergoing repair, an analysis of retinal and optic nerve samples showed that less than 5% of the CD45negCD31+ endothelial cells were CD201+ (i.e., expressing CD201 by FACS analysis). However, at this juncture more than 50% of the cells are clones of CD201+ cells (i.e., tdTomato-positive ones) (Supplementary Fig. S4b). One possible reason why stem cells may reside in the niche is hypoxia25,26. In the OIR model, as expected, hypoxia was observed in the retina, but no hypoxia was seen in the optic nerve (Supplementary Fig. S4c). Taken together with the results of in vitro experiments (in which CD157neg CD201+ and CD157neg CD201neg endothelial cells form from CD157 + CD201+endothelial cells) this suggests a hierarchy in which the CD157 + CD201+ VESCs occupy the upstream position, followed by CD157neg CD201+ endothelial cells and CD157neg CD201neg below (Fig. 5d). To characterize the role of CD201+ progenitors in vascular repair, we crossed Procr [CD201]-creERT2 mice with an inducible diphtheria toxin receptor (ROSA26iDTR) line (Fig. 6a). Selective depletion of Procr+ cells after treatment with tamoxifen and diphtheria toxin significantly increased vascular obliteration in vascular repair phase at P28 (Fig. 6b and c).

Lineage tracing analysis in a vascular injury model suggests that endothelial progenitor cells that reside in optic nerve play a pivotal role in vascular repair in the retina. a Scheme of the experimental set-up for tamoxifen administration and lineage tracing in Procr;CreERT2-tdTomato mice at indicated time points during oxygen induced retinopathy (OIR). b Flat-mount confocal microscopic analysis of the optic nerve and retina for td-Tomato combined with CD31 immunostaining. Vascular regeneration was studied at P13, P17 and P28. c Quantification of tdTomato+ area/CD31+ area in optic nerve, the central and mid-peripheral retina at P13, P17 and P28 in Procr;CreERT2-tdTomato mice during OIR model (n = 4). Data were from at least four mice for each tracing time point and lines are presented as median. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. d Schematic illustration of the hierarchy of retinal endothelial cells in this study. Each image is from representative of at least two independent experiments. Bar indicates 200 µm in the retina images and 50 µm in those of optic nerve.

a Scheme of experimental set-up for tamoxifen administration and lineage tracing in Procr[CD201]cre-ROSA26iDTR (ProcriDTR) mice at indicated time points following oxygen induced retinopathy. b Representative PECAM-1 stained OIR flat-mount retinas of ProcriDTR mice in OIR and controls at P28. Scale bars: 500 μm. In the top-right inset, neovascular tufts are shown in red and vascular obliteration in yellow. c Quantification of neovascular tufts and vascular obliteration of (b) (n = 12 in iDTR mice and n = 10 in ProcriDTR). CD201+ cells deletion resulted in more vascular obliteration. Data from at least 10 eyes and lines are presented as median. Significance was determined using two-tailed unpaired t test. Each image are from representative of at least two independent experiments. d Schematic illustration of the proposed stem cell system of retinal endothelial cells uncovered in this study.

Transcription factors in endothelial progenitors mediate vascular repair

To gain a mechanistic insight into the activity of retinal VESCs, we focused on ATF3, a transcription factor that is highly expressed in the candidate endothelial progenitor subpopulation, and whose transcription factor binding motif is enriched in the subpopulation’s transcribed enhancer regions (Fig. 2i, Supplementary Fig. S1c)21. To probe the influence of ATF3 on VESCs we generated an inducible, cell-specific mouse model in which ATF3 is selectively and conditionally deleted in endothelial progenitors upon tamoxifen treatment (Procr [CD201]-CreErt2/ATF3flox/flox) (Supplementary Fig. S5a). When oxygen induced retinopathy experiments were performed on these ATF3ΔProcr mice, a larger area of the retinal vasculature was eliminated at P17 and P21 following tamoxifen injection at P12, but not at P12 following tamoxifen injection at P7 (Supplementary Fig. S5b and c).

Discussion

A longstanding question in the field of vascular biology has revolved around identifying the origin of endothelial cells responsible for homeostasis and tissue remodeling. Here, we present multiple lines of evidence based on scRNA-seq, colony-forming assays, lineage tracing and gene targeting analyses, indicating that endothelial cells expressing stem cell markers are prominent in the optic nerve, where they supply the retina. A cellular hierarchy is proposed, which is characterized by (i) a slow supply of retinal endothelial cells by progenitors enriched in the optic nerve during homeostasis and (ii) activated vascular repair by CD201+CD157neg endothelial cells following injury (Fig. 6d).

Consistent with this model, selective ablation of the Procr (CD201)⁺ lineage (Procr-creERT2; ROSA26^iDTR^) increased vaso-obliteration during the repair phase (P28) without reducing neovascular tufts. We interpret this as consistent with our observation that tdTomato-positive cells in Procr-CreERT2-tdTomato reporter mice are relatively sparse within neovascular tufts and more abundant in large retinal vessels (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. S3c). Moreover, pan-endothelial ATF3 deletion showed the same result (expanded avascular area with unchanged neovascular tuft)27. These findings support a role for Procr-lineage cells in preserving and reconstituting the physiological capillary plexus under stress rather than directly driving pathological tuft formation.

While our data support a predominant contribution from optic-nerve–enriched progenitors, additional inputs cannot be excluded; for example, bone-marrow–derived cells may act in parallel under inflammatory or ischemic conditions. Future work should quantify the relative input of the optic nerve versus other sources.

Anatomically and developmentally, the retina is often viewed as an extension of the CNS. The current discovery of a stem cell niche in the optic nerve that supplies endothelial cells to the retinal vasculature underscores this notion. The identification of retinal endothelial stem cells in the optic nerve also opens up the possibility of developing future therapeutic strategies to treat retinal disease by inducing vascular endothelial cells to repair the retina. In the case of proliferative diabetic retinopathy, the most advanced phase of diabetic retinopathy, for example, new vascular formations originate from the retinal veins and capillaries28. However, these newly formed vessels are characteristically fragile, which significantly heightens the risk of complications, including intraocular hemorrhage and/or retinal detachment. If a more normal vasculature could be formed from endothelial cells originating from the stem cell reservoir in the optic nerve, these risks might be alleviated.

Methods

Mice

All the animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institute of Experimental Animal Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Osaka University, Japan. Procr;CreERT2-IRES-tdTomato (Jackson Laboratories), Rosa26;CAG-lsl-tdTomato (The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo), ATF3fl/fl (Tokyo Medical and Dental University)29 C57BL/6-Gt(ROSA)26Sor<tm1(HBEGF)Awai > /J (ROSA26iDTR) (Jackson Laboratories) and C57BL/6 J mouse strains (SLC and Charles River Laboratories) were used in this study. For the oxygen induced retinopathy study, mice were treated with 4 mg/25 g BW tamoxifen at P7 and examined at P12 or treated with 4 mg/25 g BW tamoxifen at P12 and examined at P13, P17, P21 and P28. Tamoxifen in corn oil (Sigma) was used. For the analysis of homeostasis, mice were treated with 4 mg/25 g BW tamoxifen at eight weeks of age and examined at 2, 7, 14, 28 and 56 dpi. In the OIR Diphtheria Toxin (DT) administration experiment, tamoxifen was administered at a dose of 4 mg/25 g body weight (BW) on P12, followed by Diphtheria Toxin (50 ng/g BW) administration on P12, P13, and P14. Mice were then analyzed on P28. Diphtheria Toxin (Sigma) was dissolved in PBS (Wako) for the injections.

Flow cytometry

Mouse retinas, heart or liver were incubated in dispase I (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and 1% collagenase I and II (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) in 4% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). Retinas were disrupted and extracted through an 18 G needle and dissociated into single cells using a 40 μM cell strainer (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The cells were blocked with anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Fc Blocker) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and stained with Brilliant Violet 421 anti-mouse CD31 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), FITC anti-mouse CD45 antibodies (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), APC anti-mouse CD157 antibodies (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and PE anti-mouse CD201 antibodies (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Dead cells were stained with propidium iodide (Immunostep, Salamanca, Spain) and excluded. Cells were analysed and sorted using a BD FACS Melody™ Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Fluorescence and light microscopy

For whole-mount retinas and optic nerves, eyes were enucleated, dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed for 2 h in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, washed in 40%, 70%, and 100% methanol and stored overnight at −30 °C in 100% methanol. The next day, the retinas were washed in 70% and 40% methanol and incubated overnight in blocking buffer (skim milk 2%, 5% NGS, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.1% Tween20 in PBS). The retinas were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer, followed by another overnight incubation at 4 °C with an appropriate secondary antibody. The retinas were mounted on microscope slides and fluorescein images acquired using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Migration experiments of stem cell-derived tdTomato+CD31+ cells in a steady state were conducted on 8-week-old Procr;tdToamto mice: The number of tdTomato-positive cells on CD31+ blood vessels was counted in 20x fields of view of the optic nerve and retina, respectively. Four fields of view were counted for each retina, central and mid-peripheral. For the optic nerve, one or two fields of view were counted for each nerve. Quantification of CD31+ Vessels and tdTomato-Positive Cells in the Procr;tdTomato mice in oxygen-induced retinopathy model. Whole-mount retinas and optic nerves were collected from Procr;tdTomato mice at postnatal day 17 following oxygen-induced retinopathy. Images were acquired using a VF3000 microscope (Olympus [now Evident], Tokyo, Japan). For vascular repair experiments in CD201-CreERT2-tdTomato reporter mice, two non-overlapping fields of view were captured at 40× magnification from the retina and two from the optic nerve. All images were processed in Fiji (ImageJ 2.0.0; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Images were first converted to 8-bit grayscale, then subjected to the “Threshold” function to generate binary masks for CD31 and tdTomato signals. The “Analyze Particles” tool was used to calculate the total positive area for each channel within each field of view. Mean vessel and cell areas were computed by averaging across the four retinal and four optic-nerve fieldsofview per animal and are reported as mean ± SEM. For vascular repair experiments in Procr[CD201]-CreERT2-ROSAiDTR and -ATF3fl/fl mice, the avascular area and surface area of NVTs were measured27. All images were analyzed using ImageJ software (v1.54) (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) or Adobe Photoshop software version (v23.5.1) (Adobe Systems Incorporated, Seattle, WA, USA). For frozen sections, fixed optic nerves were embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan) after which 10 μm-thick sections were cut. Antibodies for staining were anti-CD31(PECAM1) (1/200, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), anti-CD157(BST1) (1/200, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), anti-CD201(PROCR) (1/200, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and anti-Collagen Type Ⅳ (1/200, Merck Millipore). The secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor 488/594/647-conjugated IgG (1/500, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). To visualize the nuclei, DAPI (1/1000, Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA) was added to the secondary antibody solution. Hypoxic areas were detected by the Hypoxyprobe™-1 Omni Kit (Natural Pharmacia International Inc., Burlington, MA, USA), which contains pimonidazole hydrochloride (HCl) and rabbit anti-pimonidazole antisera (primary antibody for immunofluorescent labeling). Pimonidazol was used intraperitoneally at 60 mg/kg. The secondary antibody was an anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated IgG (1/500, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Samples were collected 90 min after pimonidazole-HCl administration, and then fixed and stained in the same manner as whole-mount retinal tissue staining.

Oxygen induced retinopathy model

Oxygen induced retinopathy was induced in C57BL/6 J mice according to a protocol described elsewhere30. Briefly, P7 pups and their mothers were transferred from room air to an environment of 75% oxygen for 5 days and after which they were returned to room air. The hyperoxic environment was created and maintained using a chamber from Bio-Spherix. Under these conditions, large hypovascular areas formed in the central retina during hyperoxia. Abnormal pre-retinal neovascularization occurred after return to normoxia, peaking at around P17 and ultimately resolving. The retina and optic nerve were dissected at P12, P13, P17, P21, P25 and P28.

Colony forming assay

Primary targeted endothelial cells were isolated and 500–5000 cells/well were co-cultured with OP9 stromal cells (RIKEN cell bank, Tsukuba, Japan) in 8-well chambers. Cultures were maintained in RPMI (Sigma-Aldrich Japan), supplemented with 10% FCS and 10–5 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Life Technologies) and VEGF (10 ng/mL; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). Cells were fixed for immunostaining after 14 days and the colony area was measured. Proliferation-positive colonies were defined as clusters of at least two adjacent CD31+ cells. Images were acquired and processed in Fiji (ImageJ v1.53c; National Institutes of Health, USA). All micrographs were first converted to 8-bit grayscale, then binarized by setting an intensity threshold via Image, Adjust, Threshold. CD31+ areas were quantified using the “Analyze Particles” function, and colonies meeting the adjacency criterion were counted as proliferation-positive.

Single-cell RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing

Mouse retinal endothelial cells were sorted using flow cytometry as described31. The cell suspensions were loaded onto a Chromium Single Cell B Chip or K Chip to generate Gel Bead-In-emulsions (GEMs) using Chromium Controller (10x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Reverse transcription was performed in a thermal cycler. First-strand cDNA was purified from the post-GEM-RT reaction mixture using DynaBeads. The cDNA was then amplified using a thermal cycler, and the amplified cDNA product was purified using the SPRIselect Reagent Kit (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Gene expression libraries were constructed using Chromium Single Cell 3′ GEM, Library & Gel Bead Kit v3 or Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5’ Kit v2 (10x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A 2100 Bioanalyzer Laptop Bundle (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to assess DNA quality and quantity. The single-cell library was sequenced using Illumina HiSeq with DNAFORM (Yokohama, Japan).

Integration analysis of 5′ and 3′ scRNA-seq data

scRNA-seq data were processed using Cell Ranger version 7.1.0 (10x Genomics) with default settings32, aligning reads to the mouse reference genome (refdata-gex-mm10-2020-A, 10x Genomics). An initial quality control was performed to exclude low-quality cells, removing cells with fewer than 200 detected genes and cells with a high mitochondrial genome content (>10%). To identify and remove potential doublets, DoubletFinder version 2.0.333 was used with default settings. The filtered data were then normalized and scaled using the Seurat package version 4.3.034, and the top 2000 highly variable genes were selected for downstream analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on these genes, and the top 20 principal components were used to cluster cells at a resolution of 0.5. To correct for potential batch effects, Harmony version 0.1.135 was used with dim = 20 and resolution = 0.5 to ensure that clusters were not biased by technical variations. Marker gene identification was performed using the FindAllMarkers function in Seurat with the parameters only.pos=true, logFC = 0.1, and min.pct = 0.05. Cell type annotation was performed based on known markers from the literature, specifically from Lukowski et al.36 and Cowan et al.37. Marker genes of cluster 10 were subjected to enrichment analysis using the clusterProfiler (v4.10.1) and ReactomePA (v1.46.0) packages to identify significantly enriched GO terms, KEGG pathways, Reactome pathways, and WikiPathways (p < 0.05).

RNA velocity analysis

Spliced and unspliced mRNA counts were obtained from the processed data using Velocyto version 0.17.1638. RNA velocity was estimated using scVelo version 0.2.439 with default settings. The analysis was conducted in a Python environment (version 3.8.19) using the Scanpy package (version 1.9.8)40.

Identification of transcribed candidate enhancer regions using 5′ scRNA-seq data

We identified 17,390 transcribed candidate enhancer regions in this study using the pipeline provided by the authors (Oguchi et al. Science 2024, https://github.com/MurakawaLab/ReapTEC)21. The versions of the tools and references used for ReapTEC are as follows: STAR version 2.7.10a41, mm10 GENCODE version M23 (primary assembly)42, umi-tools version 1.1.243, samtools version 1.15.144, bedtools version 2.30.045, bedGraphToBigWig and bigWigAverageOverBed46. To identify transcribed enhancers, transcription start site (TSS) peak pairs were detected using the scripts available at https://github.com/anderssonrobin/enhancers/blob/master/scripts/bidir_enhancers47 with minor modifications. TSS peaks were generated by merging TSSs within 10 bp of each other. The TSS regions (±300 bp) of protein-coding transcripts (mm10; GENCODE version M23 [‘primary assembly’]) were masked for negative filtering of bidirectionally transcribed regions.

Motif analysis

To examine the enhancer activity in each cluster, 5′ ends of transcripts were counted at the single-cell level to the identified transcribed candidate enhancer regions. Transcribed enhancer regions with a cutoff of log2CPM ≥ 0 in cluster 10 (Fig. 2) were used for motif analysis (n = 1315). Motif analysis was performed using AME tool implemented in MEME Suite version 5.5.548 with JASPAR2024 (Mus musculus)49 as the reference database with the following parameters: --verbose 1, -o $48, --scoring avg, --method fisher, --hit-lo-fraction 0.25, --evalue-report-threshold 1000.0, --control, --shuffle--, and --kmer 2. Input enhancer regions were modified to center ±100 bp regions of transcribed enhancers.

Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis (OIR Model)

Raw reads were aligned to the mm10 mouse reference genome using the Cell Ranger (10x Genomics, v7.1.0) count pipeline with default parameters. The output count data were corrected for ambient RNA expression using the R package SoupX (v1.6.2)50, and doublets were identified using the Python package scrublet (v0.2.3)51. The corrected count matrices were processed using the R package Seurat (v5.1.0)52. In addition to the doublets removal, low-quality cells were excluded based on the following criteria: cells with fewer than 2000 or more than 8000 detected genes, cells with more than 7% of the reads mapped to mitochondrial genes, and cells with more than 15% of the reads mapped to ribosomal protein-coding genes. To standardize the number of cells across samples, 2000 cells were randomly selected from each sample. The data were normalized and scaled using the SCTransform function while regressing out the percentage of mitochondrial and ribosomal protein-coding genes. Processed datasets of the 12 samples were integrated using the IntegrateLayers function with the CCAIntegration method. After dimensionality reductions using the RunPCA and RunUMAP functions, clustering was performed using the FindNeighbours and FindClusters functions with a resolution of 0.1. Marker genes for each cluster were identified using the FindAllMarkers function, with each sample set as a latent variable the likelihood ratio test as the statistical method. The top 10 differentially expressed genes in each cluster were visualized using the DoHeatmap function. The list of tissue-enriched EC marker genes was obtained from Kalucka et al.9. Cells with at least one read mapped to the Bst1 or Procr gene were classified as CD157+ or CD201+ cells, respectively. The proportion of cells in each sample was statistically compared using Fisher’s exact test.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source Data are provided with this paper. The scRNA-seq data from wild-type 8-week-old mice have been deposited in the Genomic Expression Archive (GEA) at DDBJ under accession number E-GEAD-882. Data from the vascular injury model are available in the ArrayExpress repository at EMBL-EBI under accession number E-MTAB-14315. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Biteau, B., Hochmuth, C. E. & Jasper, H. Maintaining tissue homeostasis: dynamic control of somatic stem cell activity. Cell Stem Cell 9, 402–411 (2011).

van Velthoven, C. T. J. & Rando, T. A. Stem cell quiescence: dynamism, restraint, and cellular idling. Cell Stem Cell 24, 213–225 (2019).

Barker, N. Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 19–33 (2014).

Homem, C. C., Repic, M. & Knoblich, J. A. Proliferation control in neural stem and progenitor cells. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 647–659 (2015).

Pietras, E. M., Warr, M. R. & Passegue, E. Cell cycle regulation in hematopoietic stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 195, 709–720 (2011).

Simons, B. D. & Clevers, H. Strategies for homeostatic stem cell self-renewal in adult tissues. Cell 145, 851–862 (2011).

Oh, J., Lee, Y. D. & Wagers, A. J. Stem cell aging: mechanisms, regulators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Med. 20, 870–880 (2014).

Lane, S. W., Williams, D. A. & Watt, F. M. Modulating the stem cell niche for tissue regeneration. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 795–803 (2014).

Kalucka, J. et al. Single-cell transcriptome Atlas of murine endothelial cells. Cell 180, 764–779.e720 (2020).

Paik, D. T. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing unveils unique transcriptomic signatures of organ-specific endothelial cells. Circulation 142, 1848–1862 (2020).

McDonald, A. I. et al. Endothelial regeneration of large vessels is a biphasic process driven by local cells with distinct proliferative capacities. Cell Stem Cell 23, 210–225.e216 (2018).

Wakabayashi, T. et al. CD157 marks tissue-resident endothelial stem cells with homeostatic and regenerative properties. Cell Stem Cell 22, 384–397.e386 (2018).

Yu, Q. C., Song, W., Wang, D. & Zeng, Y. A. Identification of blood vascular endothelial stem cells by the expression of protein C receptor. Cell Res. 26, 1079–1098 (2016).

Duh, E. J., Sun, J. K. & Stitt, A. W. Diabetic retinopathy: current understanding, mechanisms, and treatment strategies. JCI Insight 2, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.93751 (2017).

Hellstrom, A., Smith, L. E. & Dammann, O. Retinopathy of prematurity. Lancet 382, 1445–1457 (2013).

Hirschi, K. K. & Dejana, E. Resident endothelial progenitors make themselves at home. Cell Stem Cell 23, 153–155 (2018).

Trimm, E. & Red-Horse, K. Vascular endothelial cell development and diversity. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 20, 197–210 (2023).

Eilken, H. M. & Adams, R. H. Dynamics of endothelial cell behavior in sprouting angiogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 617–625 (2010).

Carmeliet, P. & Jain, R. K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473, 298–307 (2011).

May, C. A. & Lutjen-Drecoll, E. Morphology of the murine optic nerve. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 2206–2212 (2002).

Oguchi, A. et al. An atlas of transcribed enhancers across helper T cell diversity for decoding human diseases. Science 385, eadd8394 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. LRG1 promotes angiogenesis by modulating endothelial TGF-beta signalling. Nature 499, 306–311 (2013).

Connor, K. M. et al. Quantification of oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse: a model of vessel loss, vessel regrowth and pathological angiogenesis. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1565–1573 (2009).

Smith, L. E. et al. Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 35, 101–111 (1994).

Keith, B. & Simon, M. C. Hypoxia-inducible factors, stem cells, and cancer. Cell 129, 465–472 (2007).

Suda, T., Takubo, K. & Semenza, G. L. Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell 9, 298–310 (2011).

Ueda, C. et al. Endothelial activating transcription factor 3 promotes angiogenesis and vascular repair in the mouse retina. iScience 28, 111516 (2025).

Pan, J. et al. Characteristics of neovascularization in early stages of proliferative diabetic retinopathy by optical coherence tomography angiography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 192, 146–156 (2018).

Taketani, K. et al. Key role of ATF3 in p53-dependent DR5 induction upon DNA damage of human colon cancer cells. Oncogene 31, 2210–2221 (2012).

Sakimoto, S. et al. CD44 expression in endothelial colony-forming cells regulates neurovascular trophic effect. JCI Insight 2, e89906 (2017).

Sakimoto, S. et al. A role for endothelial cells in promoting the maturation of astrocytes through the apelin/APJ system in mice. Development 139, 1327–1335 (2012).

Zheng, G. X. et al. Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat. Commun. 8, 14049 (2017).

McGinnis, C. S., Murrow, L. M. & Gartner, Z. J. DoubletFinder: doublet detection in single-cell RNA sequencing data using artificial nearest neighbors. Cell Syst. 8, 329–337.e324 (2019).

Hao, Y. et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573–3587.e3529 (2021).

Korsunsky, I. et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods 16, 1289–1296 (2019).

Lukowski, S. W. et al. A single-cell transcriptome atlas of the adult human retina. EMBO J. 38, e100811 (2019).

Cowan, C. S. et al. Cell types of the human retina and its organoids at single-cell resolution. Cell 182, 1623–1640.e1634 (2020).

La Manno, G. et al. RNA velocity of single cells. Nature 560, 494–498 (2018).

Bergen, V., Lange, M., Peidli, S., Wolf, F. A. & Theis, F. J. Generalizing RNA velocity to transient cell states through dynamical modeling. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1408–1414 (2020).

Wolf, F. A., Angerer, P. & Theis, F. J. SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol. 19, 15 (2018).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Harrow, J. et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res. 22, 1760–1774 (2012).

Smith, T., Heger, A. & Sudbery, I. UMI-tools: modeling sequencing errors in unique molecular identifiers to improve quantification accuracy. Genome Res. 27, 491–499 (2017).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Kent, W. J., Zweig, A. S., Barber, G., Hinrichs, A. S. & Karolchik, D. BigWig and BigBed: enabling browsing of large distributed datasets. Bioinformatics 26, 2204–2207 (2010).

Andersson, R. et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature 507, 455–461 (2014).

Bailey, T. L., Johnson, J., Grant, C. E. & Noble, W. S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W39–W49 (2015).

Rauluseviciute, I. et al. JASPAR 2024: 20th anniversary of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D174–D182 (2024).

Young, M. D. & Behjati, S. SoupX removes ambient RNA contamination from droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing data. Gigascience 9, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa151 (2020).

Wolock, S. L., Lopez, R. & Klein, A. M. Scrublet: computational identification of cell doublets in single-cell transcriptomic data. Cell Syst. 8, 281–291.e289 (2019).

Hao, Y. et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 293–304 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Department of Ophthalmology, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University. We also thank the Biomedical Research Core and Animal Facilities, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University for technical support. This research was supported by AMED CREST (Grant Number jp23gm1210004), the JST FOREST Program (Grant Number JPMJFR2358, Japan), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (21K09674, 25K12871) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation, the Japan Foundation for Applied Enzymology (VBIC), Takeda Science Foundation Medical Research Grants, the Charitable Trust Fund for Ophthalmic Research in Commemoration of Santen Pharmaceutical’s Founder, The Global Ophthalmology Awards Program (GOAP) and a Bayer Retina Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Sakimoto., T.T. and K.N. conceptualized the project and experiments. T.T., C.U., A.S., K.S. and K.Y. performed the dissection and imaging of mice retinas. Y. F. generated the mouse OIR model. A.O., M.Y., S. Sekito and Y.M. analyzed single cell RNA-seq data. S. Sakimoto, T.T., S.K., A.J.Q. and K.N. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S. Sakimoto. is the holder of an Endowed Chair provided by ROHTO Pharmaceutical. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakimoto, S., Takigawa, T., Oguchi, A. et al. Endothelial stem cells of the retinal vasculature reside in the optic nerve. Nat Commun 17, 606 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68201-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68201-6