Abstract

Amorphous chalcogenide alloys exhibiting crystallization-free Ovonic threshold switching behaviour have gained immense attention as selector materials. While the switching characteristics depend on the chalcogen species, understanding device-level elemental behaviour, particularly for tellurium (Te), remains challenging due to its low crystallization temperature and poor glass-forming ability. Here, we realize an electrothermally induced amorphous Te (a-Te) phase via on-device cryogenic quenching, which rapidly suppresses crystallization in the supercooled liquid at low ambient temperature. The order-to-disorder transition yields a ~ 0.81 V increase in threshold voltage and a ~ 10³ reduction in subthreshold current, attributed to enhanced deep-level trap formation. The a-Te phase exhibits reliable self-regulated oscillations, driven by deep traps, distinguishing it from conventional capacitance-driven effects. These findings support that the threshold switching in Te originates from defect-mediated transitions occurring before melting, rather than solely from thermal phase-change effects. Our results provide insights into chalcogenide switching mechanisms and pave the way for stoichiometry-tuned selector devices, nano-oscillators, and selector-only memory applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovonic threshold switching (OTS), a volatile electronic switching phenomenon observed in amorphous chalcogenide alloys, has generated intense interest as a crucial enabler for high-speed, energy-efficient memory and logic systems when integrated as a selector element1. OTS behavior is marked by a rapid, substantial current increase, often spanning several orders of magnitude, at a specific threshold voltage (Vth) without inducing crystallization2,3, thus retaining the amorphous structure over 106–108 operation cycles. These characteristics position amorphous chalcogenides as ideal candidates for selector devices in high-density, parallel-processing memory arrays, where precise write and read operations are paramount4,5. Over the past decades, extensive material-level design approaches, including doping6,7,8 and heterogeneous structuring9,10,11, have been explored to enhance the selector performances. More recently, unconventional behaviors such as the prior pulse polarity effect12,13 and self-regulating oscillation14,15 have been observed, highlighting the significant impact of chalcogen species selection: tellurium (Te) vs. selenium (Se). Unlike Se-based systems, Te-containing alloys typically exhibit smaller bandgaps, lower glass transition temperatures, and a higher density of shallow trap states. More specifically, Te becomes stabilized in the amorphous matrix through enhanced covalency with other elements, thereby enabling unipolar switching and reliable oscillation. However, even though the primary component is attributed to a threshold characteristic, the intrinsic contribution of the amorphous chalcogen itself has not been directly investigated.

In parallel, elemental Te itself has been intensively investigated across a broad spectrum of fields, from fundamental materials science to practical device applications. Te forms a quasi-two-dimensional atomic configuration, consisting of one-dimensional helical chains held together by van der Waals (vdW) interactions16,17. Highly crystalline Te (c-Te) films are typically produced via traditional physical vapor deposition methods18,19,20 and, very recently, by atomic layer deposition (ALD)21. Owing to their intrinsic p-type semiconducting behavior21,22,23,24, Te has enabled the development of diverse complementary logic devices21,25,26. In addition, Te has emerged as a potential selector component, exhibiting a first-order crystal-liquid phase transition through local Joule heating20,27. The high Schottky barrier between Te and TiN enables threshold switching with low and high current operation in the crystalline solid and metallic-like liquid states. Despite growing interest, prior studies have predominantly focused on highly c-Te. In contrast, the solid-state amorphous counterpart of Te remains unexplored, largely due to its low crystallization temperature (Tcry) of −10–0 °C18 and poor glass-forming ability. While several attempts have been made to stabilize amorphous Te (a-Te) and characterize its physical properties, these efforts have been limited to a closed cryogenic deposition system, not yet extended to functional electronic device integration28,29,30,31. Meanwhile, computational investigations of monatomic amorphous chalcogen matrix have suggested hypervalent bonding networks in a-Te, distinct from conventional covalent bonding in Se- or S-based amorphous matrices32,33,34,35, further motivating experimental verification of its electronic properties.

In this work, we demonstrate a robust approach for stabilizing an electronic device that integrates both the ordered and disordered solid states of Te by simultaneously controlling the internal and external thermal conditions. The nanoscale chalcogen-metal contact effectively induced Joule heating within the proposed via-hole device, enabling selective phase transitions from the liquid chalcogen. Specifically, the rapid electrothermal quenching resulted in a disordered configuration by suppressing crystallization kinetics, sustaining its atomic arrangement under a cryogenic environment. The degradation of crystallinity generated thermally stable deep-level traps within the Te layer, resulting in a higher Vth, lower conductance, and reliable oscillation behavior. Furthermore, the formation of a highly oriented single-domain structure, thermodynamically grown from amorphous nuclei, distinctly contrasts with the polycrystalline morphology induced by electrical pulses, thereby providing indirect evidence of amorphization within the device. Although sputtered Te devices have previously been reported to show volatile switching behavior20,27, we now clarify that this behavior is governed by defect-driven switching that occurs prior to the solid-liquid transition. Furthermore, on-device cryogenic stabilization of both c- and a-Te allows us to resolve distinct physical and electrical features, most notably a self-regulating oscillation in a-Te that has not been demonstrated before. Our findings clarify the underlying electrical properties of the disordered elemental Te and so highlight its significance in the trap-assisted threshold switching of OTS materials and their applications from a device perspective.

Results

Threshold switching of tellurium under Joule heating

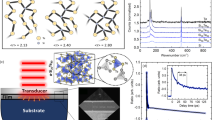

Figure 1a illustrates our 2-terminal Te-based electrothermal device employing a nanoscale via-hole architecture. This device configuration, commonly used in phase-change memory systems, is particularly well-suited for generating and modulating localized Joule heating via electrical pulse waveforms36,37. Specifically, the melting and subsequent phase transition of Te predominantly occur above the via-hole region−referred to as the programming region−where the generated electrothermal heat is maximally concentrated. Figure 1b summarizes the key experimental findings regarding the phase configurations of monatomic Te explored in this work. To achieve a disordered matrix, which is crucial for overcoming Te’s inherently poor glass-forming ability, we adopted a rapid quenching strategy from the liquid phase. This approach effectively suppresses nucleation and inhibits nuclei growth in the supercooled liquid, thereby preventing crystallization. Consequently, reversible and programmable transitions between ordered and disordered phases are achieved from the liquid phase in the via-hole region, governed by precisely controlled electrothermal pulses. Both solid states of Te can be demonstrated inside a nanoscale device at ambient room temperature (RT) and in a cryogenic environment. However, holding the programmed Te at RT provides sufficient thermal energy to induce recrystallization, thereby reverting the amorphous phase to the crystalline state and promoting defect relaxation even within the crystalline phase. In contrast, both solid states, particularly a-Te, remain stable under cryogenic conditions, enabling reliable characterization of their physical and electrical properties without thermal interference.

a Schematic illustration of the Te device based on a via-hole architecture. b Summary of reconfigured Te phases investigated in this work. A cryogenic environment is essential for retaining electrothermally constructed Te phases, particularly for the electrical analysis. c Bright-field transmission electron microscope (BF-TEM) image of the fabricated Te device with a ~400 nm hole diameter. The scale bar is 200 nm. d Raman spectra of as-deposited Te films on the metal electrode and dielectric layers. Inset images represent E1, A1, and E2 vibrational modes of the hexagonal Te phase. e Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) analysis of bulk W and Te. The measured work function difference is ~0.25 eV. The scale bar is 2 μm. f Expected energy band alignment between p-type Te and W. g–i Threshold switching in the Te device. All measurements are conducted at room temperature (RT). g False-colored scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the Te device array. The scale bar is 30 μm. h I–V plots of the Te device for the initial, after first, and 100th triangular pulse injections. i Dynamic transient curve showing input voltage (Vinput) and output current (Ioutput) during an initial single triangular pulse injection.

detailed fabrication procedures for the Te device are provided in the Methods section and Supplementary Fig. 1. Cross-sectional high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) and corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) confirm successful device fabrication with a via-hole diameter of 400 nm (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2). Initial characterization by Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 1d) with isotropic angle-resolved properties (Supplementary Fig. 3) and X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Fig. 4) revealed that the as-deposited Te thin films exhibit a randomly oriented hexagonal polycrystalline structure on both metal and dielectric layers. As discussed, two distinct Te solid states can be stabilized under cryogenic conditions, and their electrical characterization below RT necessitates minimizing the Schottky barrier height between Te and the metal electrode. To achieve this, tungsten (W) was selected as the bottom electrode contact (BEC) material to mitigate excessive Schottky contact with Te20. Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) was employed to determine the work function difference between W and Te (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 5), yielding a low Schottky barrier height of 0.20–0.25 eV for the p-type monatomic Te film (Fig. 1f). This optimized contact design ensures that electrical contrasts originate from the intrinsic chalcogen phases via the electrothermal effect within the nanoscale device.

The Te device arrays were initially evaluated at RT using a triangular pulse with a 3 V input voltage and 1 μs rise/fall times (Fig. 1g). Figure 1h displays the output current−input voltage (I–V) curves over multiple pulse cycles, clearly demonstrating volatile OTS characteristics. This behavior is attributed to intrinsic trap states associated with lone-pair electrons within Te’s covalent bonding networks, which is experimentally discussed in the subsequent sections38,39. To capture the sequential phase transitions, we present the dynamic transient responses to the initial pulse injection, showing the progression from the initial solid state to the liquid phase, and finally to the rearranged solid state (Fig. 1i). Initially, the device exhibited a low current until reaching a threshold voltage (Vth) of 1.90 V. Beyond this point, a sufficient electric field induced a high current flow. The low melting temperature of Te (~450 °C) facilitated its transformation into the liquid phase with only a few mA of current20, solidifying as the pulse fell. Subsequently, the device reverted to a low current state below a holding voltage (Vh) of 0.72 V. During multiple 1 μs melt-cooling processes, the Vth stabilized around ~1.1 V, while the subthreshold current gradually increased (see Supplementary Fig. 6 for details). These results confirm that the nanoscale via-hole device effectively generates localized Joule heating within the programming region, inducing phase rearrangement of the solidified Te.

Reversible order to disorder phase transition

Figure 2a illustrates the conceptual framework and experimental design for regulating the quenching rate within the programming region, i.e., the Te melting zone induced by Joule heating above the BEC, so as to achieve reversible transitions between ordered and disordered Te phases. This approach emulates melt-quenching processes wherein a fast quenching speed on the nanosecond timescale leads to amorphization, while slower cooling favors crystallization. The output current directly correlates with the electrothermal temperature achieved during Joule heating, and critically, the pulse fall time determines the time-dependent temperature gradient (dT/dt). All electrical measurements presented in Fig. 2 were conducted at RT.

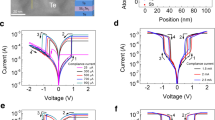

All measurements are conducted at RT. The subthreshold current is measured using a direct current (DC) bias (IDC) of 0.5 V. a Schematic of ordered-disordered phase transitions from the liquid phase via adjusted pulse conditions. b I–V curves for HRS and LRS across 50 individual Te devices. c Statistical distributions of Vth and IDC. The order-to-disorder phase transition induces a ~0.81 V in Vth and ~103 times in IDC. d Cycle-to-cycle variations in Vth and IDC at HRS and LRS. e Time-relevant retention behavior plotted using logarithm and linear-scaled currents. f, g Defect annihilation in electrothermally reconfigured crystalline Te. f I–V plots and g Vth-IDC trends at various LRS relaxation times. h Conductance values for various atomic arrangements, extracted from 50 individual Te devices. Box plot elements are defined as follows: the center line denotes the median; box limits represent the upper and lower quartiles; whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range.

Based on such quenching-rate-guided phase regulation, we obtained I–V curves for two distinct Te phases−a high resistance state (HRS) and a low resistance state (LRS)−across 50 devices (Fig. 2b). The subthreshold current was measured using a direct current (DC) bias (IDC) of 0.5 V. The HRS was programmed with a 5 V pulse (20 ns rise, 100 ns width, 20 ns fall), while the LRS was achieved using a 3 V pulse (1 μs rise, 100 ns width, 1 μs fall). The reading pulses in the dynamic transient curves exhibited distinct contrasts in Vth and subthreshold current after programming HRS and LRS, but with identical switching times of ~45 ns (Supplementary Fig. 7). Based on these results, we analyzed the probability distributions of Vth and IDC (Fig. 2c). Gaussian fit curves reveal distinct distributions with an average Vth contrast of ~0.81 V and an IDC difference spanning approximately three orders of magnitude. This IDC difference notably aligns with the reported resistivity ratio between a-Te and c-Te40. The device also demonstrated cyclic reliability exceeding 104 cycles, confirming its durable phase transition (Fig. 2d). Additionally, the identical phenomenon was observed in devices utilizing an ALD-grown Te layer, indicating that the observed behavior is indeed intrinsic to the material itself (Supplementary Fig. 8). We also confirmed the negligible polarity effects in the Te device during both programming and reading pulses (Supplementary Figs. 9, 10), ruling out conductive paths within the chalcogen matrix generated from the metal electrode. We note that polar segregation and internal or interfacial dipole formation are further prohibited in our devices because the monatomic Te is non-polar and structurally homogeneous41,42. Finally, we investigated the final solidified arrangement of the liquid monatomic chalcogen across a range of input voltages and fall times (Supplementary Fig. 11), demonstrating how the atomic configuration is solely dictated by the quenching rate.

Notably, the threshold switching (TS) was identified as an inherent phenomenon, independent of the Te phases. This key observation prompted a deeper investigation into whether the TS mechanism, particularly in the crystalline phase, is defect-driven rather than exclusively associated with a liquid-solid phase transition. To elucidate the origin of this phenomenon, we compared our Te device with a standard Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST)-based PCM device, utilizing the concept of an order-to-disorder transition. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12, both GST and Te devices transition from the initial LRS to the HRS via melt-slow quenching. However, under identical pulse rise regimes in the dynamic transient curves, TS occurred exclusively in the Te device, whereas crystalline GST exhibited linear I–V behavior. Furthermore, the S-shaped negative differential resistance observed in the current-driven I–V curves of both a-Te and c-Te provides additional evidence of OTS behavior in monatomic Te phases (see Supplementary Fig. 13 for details). This stark contrast strongly suggests that the TS in c-Te arises from intrinsic defect states rather than electrothermal phase transitions.

Significantly, thermally unstable Te phases reorganize upon exposure to ambient thermal energy (Fig. 2e). The HRS initially sustained its current, but rapidly increased and saturated within ~102 s due to spontaneous crystallization. Conversely, the LRS current level gradually decreased, as clearly monitored in the linear scaling retention results. To elucidate these phenomena, Fig. 2f and Fig. 2g explore the time-dependent Vth drift of the LRS. The relaxation time (trelax) was defined as the interval between two identical triangular pulses, ranging from 100 ns to 105 s. The Vth remained constant within ~100 μs of trelax but soon began to perturb after a few seconds. After about 105 s (24 h), it reached full saturation, showing a voltage difference of ~0.8 V. Typically, Te-containing amorphous OTS alloys exhibit a drift phenomenon within 100 μs, primarily due to latent heat from Joule heating43. Therefore, the Vth drift observed in our Te device is best explained by structural relaxation and subsequent defect annihilation in the electrothermally reconfigured ordered phase (see Supplementary Fig. 14 for details)44. As the fully annihilated current level of LRS is identical to the recrystallized HRS (Fig. 2e), it suggests that the disordered state spontaneously crystallizes towards a thermodynamically stable ordered state of elemental Te, further evident in time-dependent relaxation in HRS as presented in Supplementary Fig. 15. The observed current decrement of LRS is directly attributed to the Vth drift, which ultimately saturates as it reaches its equilibrium state at ambient temperatures. Furthermore, the pulse-induced defect relaxation in a-Te yields defect dynamics comparable to those of conventional OTS materials when using pulse conditions tailored to match prior reports44,45 (see Supplementary Fig. 16 for details).

During the order-disorder transitions, we obtained the conductance values for three Te phases: disordered, liquid, and ordered (Fig. 2h). Details of the extracted calculations are provided in Supplementary Note 1. Notably, the conductance extracted for each Te phase was converted to an estimated resistivity under the assumed device geometry, and the resulting values are in good agreement with previously reported experimental data (see Supplementary Table 1). Starting from the initial liquid phase, solidification into distinct atomic arrangements leads to significant contrasts in their conductance. Specifically, a 20 ns fall time effectively transforms supercooled liquid Te into an amorphous solid state by suppressing the stable nucleation growth. Given that these outcomes correlate with the defect population within the Te phases, the inherent trap characteristics are further investigated under cryogenic conditions, where both thermally unstable solid states can be reliably preserved.

Phase dependent trap characteristics in tellurium

The specific trap characteristics were examined under cryogenic conditions (T < Tcry) (Fig. 3). All the electrical analyses were conducted at 80 K, unless otherwise noted as RT or as part of temperature-dependent measurements. The order-disorder phase transition was also clearly demonstrated at 80 K, showing a ~0.4 V positive shift in Vth compared to RT conditions (Supplementary Fig. 17). Figure 3a presents robust phase retentions for over 103 s in both the ordered and disordered phases. Notably, the LRS maintained its current level without any disturbance from delocalized defect annihilation, emphasizing the necessity of cryogenic stabilization for preserving electrothermally reconfigured monatomic chalcogen phases. Distinct trap properties were extracted using a Poole-Frenkel-based thermally assisted hopping (TAH) conduction model, described by the following equation:

where \(q\) is the elementary charge, \(A\) is the BEC area, \({N}_{{{{\rm{T}}}},{{{\rm{tot}}}}}\) is the integral of the trap distribution (approximately \(\frac{1}{{\Delta z}^{3}}\)), \(\Delta z\) is trap-to-trap distance, \({E}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\) is the activation energy, \({V}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}\) is the applied bias, \({k}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}\) is the Boltzmann constant, \(T\) is temperature, and \({u}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\) is the chalcogenide thickness46,47. Given that the current flow in Te is mainly hole-driven below 150 K48, the trap-limited conduction model considers holes as the primary mobile charge carriers. Figure 3b showcases the DC I–V curves for individual HRS and LRS in the subthreshold voltage region. The extracted HRS trap characteristics exhibited a ~0.93 nm reduction in \(\Delta z\) and a 0.06 eV larger \({E}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\), compared to those of the LRS. Additionally, the DC measurements of a-Te confirmed OTS functionality, showing an off-current of ~60 nA at 1/2 Vth and an on/off ratio of ~103 under compliance-limited conditions, which increases to ~104 without compliance (Supplementary Fig. 18).

a Time-dependent retention of HRS and LRS at 80 K and comparison with the LRS at RT. b DC I–V curves in the subthreshold region of HRS and LRS at 80 K. The Poole-Frenkel-based thermally assisted hopping (TAH) model exhibits a good fit for both Te states. Inter-trap distance (\(\varDelta Z\)) and activation energy \(({E}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}})\) of HRS and LRS were extracted from model fitting. c Temperature-dependent conductance of disordered Te state (HRS). The inset graph indicates a rearranged ln(G)-1/kbT plot to extract activation energies. d–f Investigation of inherent trap properties regarding pulse quenching rate. All measurements are conducted at 80 K. d Vth inspections of HRS as a function of pulse fall time. The programming pulse is identical to the conventional HRS pulse, and the fall time ranges from 50 to 450 ns. e DC I–V curves in the subthreshold current region at various pulse fall times. f \(\Delta z\) and \({E}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\) trends corresponding to pulse fall times.

Furthermore, \({E}_{a}\) was validated through temperature-dependent conductance (\(G\)) measurements of the HRS, using the following equation:

where G0 is the initial conductance (Fig. 3c). The disordered Te exhibited p-type semiconducting behavior, consistent with previous reports49. The inset of Fig. 3c presents a logarithmic conductance plot versus inverse temperature, from which two distinct \({E}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\) values are derived. The boundary point between these two linear regions correlates with Vth changes observed under varying measurement temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 19). Notably, the extracted energy of ~0.15 eV is comparable to the \({E}_{a}\) obtained from the TAH model. A minimal \({E}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\) of ~0.004 eV indicates a localized trap forming an Urbach tail near the valence band edge50. Figure 3d–f further explore trap properties as a function of the quenching rate at 80 K. At a fixed input voltage of 5 V, the Te device abruptly transitioned from the HRS to the LRS when the fall time reached 300 ns (Fig. 3d). Concurrently, the subthreshold current gradually increased, even as the Vth remained similar between the HRS and LRS regions (Fig. 3e). The gradually reduced quenching rate consistently led to the annihilation of deep-level trap density, as reflected by clear trends in \(\Delta z\) and \({E}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\) dictated by the regulated fall time (Fig. 3f). Consequently, the disordered phase possesses energetically more stable and denser deep-level traps than the ordered phase.

The presence of such energetically stable and dense trap populations in disordered Te is presumed to be a key factor enabling reliable oscillations. Investigations into the trap nature revealed robust self-oscillation performance in the monatomic chalcogen device (Fig. 4). Experimental details are described in Fig. 4a and Supplementary Note 2. While the oscillations are generally observed in Te-containing amorphous chalcogenide materials, explicit mechanistic evidence has often been lacking51. Here, reliable oscillations were clearly demonstrated in the HRS, driven by self-modulation of the applied bias in response to a 100-μs square pulse (Fig. 4b). The average oscillation period was ~7 μs, composed of a switching time of ~0.28 μs and a relaxation time of ~6.72 μs (Fig. 4c). In contrast, Fig. 4d shows a constant current without any oscillatory behavior in the LRS. The consistent absence of oscillation across various input voltages in the LRS indicates a fundamental lack of physical factors required to establish self-regulated properties in this state (Supplementary Fig. 20). Further analysis of the HRS oscillatory behavior was conducted under prolonged square pulses (>300 μs). Despite the current injection being mitigated by external resistance, a continuous oscillation current range of 50–100 μA gradually transformed the initial amorphous phase into the crystalline phase; accordingly, the oscillation characteristics then vanished (Fig. 4e).

All measurements are conducted at 80 K with an external resistance (RExt) of 50 kΩ. a Schematic of the measurement setup and representative oscillation waveform in the Te device. b Dynamic transient voltage curves during oscillation in the HRS. VInput indicates the input voltage, while VTe and VExt represent the bias across the Te layer and RExt, respectively. c Time components of each oscillation period, consisting of a rise time (abrupt threshold switching) and a fall time (current relaxation). d Self-oscillation phenomenon in the monatomic Te. Notably, only the HRS represents a reliable oscillation. e Oscillation failure at the long-range period of input bias due to the transformation towards the LRS. f–h Oscillation behavior as a function of HRS programming fall time, with a fixed 5 V amplitude, 20 ns rise time, and 500 ns pulse width. f Oscillation waveforms under varying fall times. g Decay and rise times during oscillation within a 100-μs square pulse. h Minimum and maximum current levels during oscillation within a 100-μs square pulse. Box plot elements are defined as follows: the center line denotes the median; box limits represent the upper and lower quartiles; whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range.

The defect-related oscillation behavior in disordered Te was further investigated (Fig. 4f–h). To systematically modulate the defect density in the amorphous matrix, the fall time of the HRS programming pulse was varied from 50 to 250 ns, while other parameters remained constant (details provided in Fig. 3d). Figure 4f showcases the oscillation waveforms corresponding to the quenching rate-dependent disordered Te phases. The corresponding oscillation components were then analyzed under a 100-μs square pulse (Fig. 4g, h). Specifically, the current rise time remained constant at 40–50 ns regardless of fall time, matching the HRS switching time (Supplementary Fig. 7). Conversely, the current decay time gradually decreased as the minimum oscillation current increased (Fig. 4h), which is a direct result of the reduction in deep-level trap density. Collectively, these results strongly underscore that the deep-level traps, originating from localized defects in Te, are essential for robust oscillation behavior, while shallow-level traps inhibit self-regulating performance. A detailed electrical and atomic-level description of oscillation in the Te devices is provided in Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 21–23.

Theoretical comparison of three tellurium phases

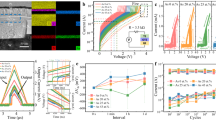

To support the experimental outcomes, various Te phases were rigorously analyzed using ab initio molecular-dynamics (AIMD) simulations. Figure 5a displays the disordered atomic configuration of the a-Te, constructed with 180 Te atoms. For direct comparison, the charge density distributions of both amorphous and crystalline phases were visualized along the same crystallographic orientation corresponding to the (200) plane in the crystalline structure (Fig. 5b), clearly revealing distinct differences between the disordered and ordered configurations. The amorphous phase exhibited only short-range order (SRO) without any periodicity. In contrast, a long-range order (LRO), characterized by periodic alignment between adjacent helical Te chains, was clearly observed in the crystalline phase (see Supplementary Fig. 24 for details). To further understand the amorphous matrix, we examined the local bonding environment of disordered Te. The bond-angle distribution revealed two dominant populations: one at 90–100° and another exceeding 160° (Supplementary Fig. 25a). The latter is attributed to the presence of hypervalent networks involving lone-pair electrons. Furthermore, the bond length distribution indicated a mid-range order (MRO) at ~4.351 Å and a prominent SRO at ~2.940 Å (Supplementary Fig. 25b).

Each Te phase is constructed with 180 Te atoms in a supercell. a Amorphous model of disordered Te at 80 K. b Contour maps of electron charge density of disordered and ordered Te on the (200) plane. The amorphous Te uses a cubic supercell, while a trigonal lattice is adopted for the crystalline Te. Total density of states (TDOS) and their inverse participation ratio (IPR) of c disordered, and d ordered phase. Notably, due to the limitation of the exchange-correlation functional employed in this study, the resulting computed bandgap is slightly larger than that of the bulk Te16,21. e Bandgap of disordered, ordered, and liquid phases. All the bandgaps are extracted from the TDOS and IPR. f Maximally localized Wannier function spread (\({\varOmega }_{{{{\rm{avg}}}}}^{0.5}\)) of disordered, ordered, and liquid phases. The error bar represents the standard deviation.

To investigate the bandgap (Eg) and the mid-gap state (MGS), we calculated the total density of states (TDOS) and corresponding normalized inverse participation ratios (IPR). Higher IPR values indicate more localized electron states. In the disordered Te phase, the calculated Eg was ~0.7 eV, significantly larger than that of c-Te (Fig. 5c, d). No MGS was observed in the ordered Te, consistent with the defect-free nature of the crystalline supercell. In contrast, a distinct MGS appeared in the disordered phase at ~0.18 eV, close to the valence band maximum. This theoretical result matches the Ea of trap states in disordered Te within 30 meV, as experimentally extracted from the p-type hole-driven analytic conduction model (Fig. 3b, c). Additionally, the statistical analysis of multiple independently constructed a-Te models yielded mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) values of (0.704 eV, 0.040 eV) for Eg and (0.156 eV, 0.045 eV) for Ea, in good agreement with Fig. 5c (Supplementary Fig. 26). The high reproducibility across these models indicates that the calculated electronic properties capture intrinsic features of disordered Te. Partial DOS (PDOS) for the 4s, 4p, and 3d orbitals of Te further elucidated the orbital contributions to the MGS (Supplementary Fig. 27). All 4p orbitals (e.g., 4px, 4py, and 4pz) significantly contributed to forming the MGS, while the 4s orbital accounted for less than 5 %. This suggests that the dominant trap states dispersed in disordered Te originate from hypervalent networks involving lone-pair electrons, a feature absent in amorphous Se35. Exceptionally, the liquid Te phase displayed continuously dispersed delocalized orbitals across all band energies (Supplementary Fig. 28). The absence of a well-defined bandgap and the extensive orbital overlay further support the metallic nature of the liquid Te.

The conductivity differences among the ordered, disordered, and liquid Te phases were subsequently interpreted in terms of Eg and the maximally localized Wannier function (MLWF) spread. Figure 5e displays a stepwise increase in Eg, corresponding to the transition from liquid to ordered, and then to disordered Te. The 0.58 eV Eg of the ordered phase slightly differs in the bandgap extracted via UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy (~0.33 eV for 45-nm-thick Te), presumably due to the exchange-correlation functional employed (Supplementary Fig. 29). The MLWF spread was then analyzed in Fig. 5f. Specifically, the spread of each MLWF, \({\varOmega }_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}\), represents the measure of spatial extent (i.e., variance) from the center of the Wannier function, expressed as following equation:

where \({w}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}\) is nth Wannier function, and r is the position vector. From the disordered, to ordered, to liquid phases, the average spread (\({\varOmega }_{{{{\rm{avg}}}}}^{0.5}\)) gradually increased, indicating reinforced electron delocalization35. Collectively, the consistent trends in Eg and MLWF spread explain the abrupt conductance contrast between the liquid and two solid states (a-Te and c-Te), as discussed in Fig. 2h.

Structural characterization of the amorphization pathway

To confirm the formation of electrothermally programmed amorphous monatomic Te, we performed a detailed TEM analysis. Since direct observation of disordered Te is challenging without specialized in-situ cryogenic TEM capabilities, we instead investigated the atomic reconfiguration via post-annealed grain growth from the presumed a-Te within the nanoscale device18. To prepare the specimen, the Te device was initially programmed to the HRS at 80 K, and then subjected to a post-annealing process at 273 K for 1 h. Figure 6a presents the prepared device, analyzed via the cross-sectional TEM. Three distinct Te regions were defined based on the influence of Joule heating: (i) the programming region above the metal electrode (Areas 1–4), (ii) the non-programming region above the dielectric layer (Area 6), and (iii) the intermediate region (Area 5) between (i) and (ii). Fast Fourier transform (FFT) was applied to areas 1–4 within a 400 nm2 scale along the fixed zone axis of [0001] (Fig. 6b). The results strikingly revealed identical hexagonal configurations within the region that had been previously amorphized. While the entire region did not transform into a fully single-crystalline domain, each grown grain, exceeding 100 nm in size, exhibited a consistent orientation towards an identical crystallographic order. Furthermore, we compared FFT analyses of three distinct ordered Te phases: (i) as-deposited Te at RT, (ii) electro-thermally crystallized Te induced by multiple LRS pulse injections, and (iii) post-annealed Te grown from amorphous nuclei above the metal electrode (Supplementary Fig. 30). Although injecting a slow cooling pulse also tends to align the crystallographic orientation of Te, misoriented grains are still clearly observed in that case. The highly uniform orientation observed only in the post-annealed amorphous region provides compelling and distinctive evidence for the successful amorphization process of monatomic Te within our device.

a Bright-field transmission electron microscope (BF-TEM) image of a Te device after programming to HRS at 80 K and post-annealing at 273 K for 1 hour. The scale bar is 200 nm. b Fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns for areas 1–4 within the programming region. c High-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM) image of trigonal helical Te between areas 1 and 2. The scale bar is 10 nm. The inset TEM image indicates a lattice constant of the trigonal phase after crystallization. The inset scale bar is 0.4 nm. d Moiré pattern of Te within the intermediate region (area 5). Parallel and vertical helical Te chains along the zone axis of [0001] coexist in area 5. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns from e the programming region (between areas 1–2) and f the non-programming region (including area 6). The aperture size of the SAED pattern is ~100 nm. Both scale bars are 5 nm−1.

The origin of the hexagonal FFT images is further elucidated in Fig. 6c. High-angle annular dark-field STEM (HAADF-STEM) analysis revealed large-scale trigonal helical chains with a lattice constant of ~4.348 Å. This extracted lattice constant matched the d-spacing of (10-10) planes (~3.788 Å), within the zone axis of [01-10] (Supplementary Fig. 31). In the intermediate region, a Moiré pattern was observed, indicating the coexistence of parallel and vertical helical chains along the same zone axis (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 32). This is attributed to the radial dispersion of hemispherical Joule heating generated during device programming. Interestingly, the lattice constant of this hexagonal motif was slightly smaller than that of bulk trigonal Te (~4.5 Å). It is speculated that over-coordinated (>2-folded) MRO Te clusters act as crystalline nuclei, given that their interatomic distances are similar to the recrystallized lattice constant34,52. Selected area diffraction (SAED) patterns with the aperture size of ~100 nm were subsequently analyzed in the programming and non-programming regions (Fig. 6e, f). Consistent with prior XRD results (Supplementary Fig. 4), small Te grains above the dielectric layer, lacking a preferred orientation, produced irregular diffraction spots. In contrast, the SAED patterns from the programming region unequivocally confirmed the presence of a highly oriented hexagonal phase. Consequently, our results provide robust evidence that rapid melt-quenching successfully induces a-Te formation within the nanoscale device, reliably covering the BEC contact region. We further note that visualizing a-Te via on-device cryogenic quenching combined with in-situ cryogenic TEM could enable direct observation of the amorphization process, which is potentially investigated in future studies.

Discussion

In this work, we selectively demonstrated the electrothermally controlled crystallographic arrangement of monatomic Te by utilizing effectively generated Joule heating within the nanoscale device. Unlike previous reports that predominantly focused on c-Te, our work directly investigates the threshold characteristics and critical material implications of its disordered counterpart. We successfully established and stabilized two distinct solid states, ordered and disordered Te phases, by precisely tuning the melt-quenching rate under a cryogenic environment. Reversible order-to-disorder phase transitions exhibited significant differences in both the Vth and subthreshold current. These changes primarily originate from the degree of trap localization, specifically an increased concentration of traps moving closer to the Fermi level in the amorphous phase. The presence of energetically stable deep traps enhanced the self-regulation characteristics, providing clearer insight into the fundamental mechanism underlying the oscillation phenomenon. Under these circumstances, TS in both Te phases is predominantly governed by defect-mediated transitions, whereas a subsequent first-order solid-liquid phase-change occurs by post-Joule heating after sufficient current injection. Furthermore, the formation of highly oriented, larger-sized crystallites grown in the amorphous domains confirmed that a stable disordered configuration could be achieved through rapidly quenched Joule heating. Our investigation offers a meaningful perspective on the critical role of the chalcogen element in the basis of OTS behavior, Vth modulation by prior pulses, and the revealing oscillation phenomenon in amorphous chalcogenide glasses.

Methods

Device fabrication

The bottom electrode contact (BEC) was initially defined on the 300-nm-thick SiO2/Si substrate. Firstly, W was deposited using a DC sputter. Conventional photolithography and dry etching via an inductively coupled plasma-reactive ion etching (ICP-RIE) were sequentially processed for patterning. The photoresist was cleaned with the solvent (e.g., acetone and IPA). After that, a 30 nm Si3N4 dielectric layer was deposited using a plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition technique. A nanoscale hole was then patterned via a combination of e-beam lithography and ICP-RIE. Next, an RF sputtering system was used to cover the patterned area completely with monatomic tellurium (Te, 45 nm) or phase-change material (GST, 180 nm) inside the via hole. The base pressure was under 5 × 10−7 torr to obtain high-quality, non-oxidized chalcogen film. After that, TiN (~10 nm) by reactive sputtering with Ti target and N2 gas was immediately encapsulated Te film to prevent oxidation. It is patterned by the lift-off process. Prior to the metallization, BEC opening is defined by the ICP-RIE process, as the etching region is defined by photolithography. Finally, TiN (~10 nm) and W (100 nm) were deposited for metallization of both bottom and top electrodes within the lift-off and solvent-cleaning process. Note that, TiN should be interposed between chalcogenide materials and W due to the adhesion issues.

Thin-film characterization

Surface topography and film thickness were measured by AFM (MFP-3D Origin, Oxford Instruments) in a tapping mode using the Si cantilever (AC160TS-R3). The work function difference between adjacent materials was obtained by KPFM surface potential map using a Ti/Ir (5/20 nm)-coated tip (ASYELEC-01-R2, AsylumResearch) with a resonance frequency of 75 kHz and a force constant of 2.8 N m−1. Phonon vibration modes were inspected by a confocal micro-Raman system (customized based on XperRam 200 S, NANOBASE Inc.) using a 532 nm laser with a power of 0.3 mW. Crystallinities of the thin film were obtained by XRD (Bruker, D8 Discover system) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5405 Å) in the 2θ of 20–60°. For GI-XRD, the incident angle for the X-ray beam source and sample stage is tilted by 0.3°. Optical bandgaps were investigated using a UV-Vis spectrometer (Cary 5000, Agilent) analyzed by the Tauc plot53.

Electrical measurements

Electrical measurements were performed using a Keithley 4200A-SCS semiconductor analyzer and pulse measure unit (4225-PMU). Minimum rise/fall time and pulse width of electrical pulses are 20 ns and 50 ns, respectively. To obtain accurate resistance values, we employed a DC reading voltage of 0.5 V utilizing an embedded source measure unit (SMU). Also, we used remote preamplifier/switch modules (4225-RPM) to connect both PMU and SMU for comfortable conversion of DC and AC pulse measurements. The cryogenic environment was constructed using liquid nitrogen (LN2) gas, cooling the vacuum chamber. To achieve self-regulating oscillations, the external resistance of ~50 kΩ was series connected between the BE probe and the RPM module.

Cross-sectional TEM characterization

A cross-sectional TEM specimen was prepared using a focused ion beam (FIB) (Helios 450 HP FIB). The Te device under investigation was first coated by a Pt thin film (FEI sputter), and then the amorphous carbon layer was deposited on the target area to minimize ion beam damage during the FIB preparation. The cross-sectional high-resolution bright-field high-resolution TEM and high-angle annular dark-field (HAA-DF) TEM images of the Te device were acquired using a Cs-corrected scanning TEM (JEOL, JEM-ARM300F) operated at 160 kV.

Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulations

Ab initio molecular-dynamics (AIMD) simulations based on density-functional theory (DFT) were employed to construct and analyze crystalline, amorphous, and liquid Te models, as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) code54. All models used the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional55 within the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method56. For bandgap calculations, the hybrid functional of HSE06 was employed57. A plane-wave energy cutoff of 300 eV was used. The crystalline model consisted of 81 Te atoms in a supercell. The amorphous model was generated with 180 Te atoms via a melt-quenching process, cooling from 900 K to 80 K at a rate of 5 K/ps. The temperature was controlled by a Nosé thermostat algorithm, and the MD time step was 3 fs. The simulation volume was kept constant during the AIMD simulations. Structural relaxation of the quenched amorphous models was carried out using the conjugate-gradient method at 0 K, until the force on any atom was less than 0.01 eV/Å. Maximally localized Wannier functions and their spread were computed by the wannier90 code58.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the main text and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Ovshinsky, S. R. Reversible electrical switching phenomena in disordered structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 21, 1450–1453 (1968).

Zhu, M., Ren, K. & Song, Z. Ovonic threshold switching selectors for three-dimensional stackable phase-change memory. MRS Bull. 44, 715–720 (2019).

Zhao, Z. et al. Chalcogenide ovonic threshold switching selector. Nano Micro Lett. 16, 81 (2024).

Wen, T. H. et al. Fusion of memristor and digital compute-in-memory processing for energy-efficient edge computing. Science 384, 325–332 (2024).

Ielmini, D. & Wong, H. S. P. In-memory computing with resistive switching devices. Nat. Electron. 1, 333–343 (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Performance improvement of GeTex-based ovonic threshold switching selector by C doping. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 42, 688–691 (2021).

Ban, S. et al. Effect of silicon doping in B-Te (B4Te6) binary ovonic threshold switch system. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 43, 643–646 (2022).

Wu, R. et al. The role of arsenic in the operation of sulfur-based electrical threshold switches. Nat. Commun. 14, 6095 (2023).

Adinolfi, V. et al. ALD heterojunction ovonic threshold switches. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2, 3818–3824 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. A symmetric multilayer GeSe/GeSeSbTe ovonic threshold switching selector with improved endurance and stability. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Integrated Circuits, Technologies and Applications (ICTA) 2, 45–46 (IEEE, 2021).

Lee, J. et al. Enhanced switching characteristics of an ovonic threshold switching device with an ultra-thin MgO interfacial layer. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 43, 220–223 (2022).

Lee, J. et al. Understanding switching mechanism of selector-only memory using Se-based ovonic threshold switch device. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 71, 3351–3357 (2024).

Ravsher, T. et al. Polarity-induced threshold voltage shift in ovonic threshold switching chalcogenides and the impact of material composition. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. 17, 2200417 (2023).

Fu, Y. et al. A 2.22 Mb/s true random number generator based on a GeTex ovonic threshold switching memristor. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 44, 853–856 (2023).

Jeon, J. W. et al. Vertically stackable ovonic threshold switch oscillator using atomic layer deposited Ge0.6Se0.4 film for high-density artificial neural networks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 15032–15042 (2024).

Qiu, G. et al. The resurrection of tellurium as an elemental two-dimensional semiconductor. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 6, 17 (2022).

Reed, E. J. Two-dimensional tellurium. Nature 552, 1–2 (2017).

Zhao, C. et al. Tellurium single-crystal arrays by low-temperature evaporation and crystallization. Adv. Mater. 33, 2100860 (2021).

Kim, T. et al. Growth of high-quality semiconducting tellurium films for high-performance p-channel field-effect transistors with wafer-scale uniformity. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 6, 4 (2022).

Shen, J. et al. Elemental electrical switch enabling phase segregation–free operation. Science 374, 1390–1394 (2021).

Kim, C. et al. Atomic layer deposition route to scalable, electronic-grade van der Waals Te thin films. ACS Nano 17, 15776–15786 (2023).

Qin, J. K. et al. Raman response and transport properties of tellurium atomic chains encapsulated in nanotubes. Nat. Electron. 3, 141–147 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Field-effect transistors made from solution-grown two-dimensional tellurene. Nat. Electron. 1, 228–236 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Thickness-dependent bandgap and atomic structure in elemental tellurium films. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. 18, 2300414 (2024).

Zhao, C. et al. Evaporated tellurium thin films for p-type field-effect transistors and circuits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 53–58 (2020).

Zhou, G. et al. High-mobility helical tellurium field-effect transistors enabled by transfer-free, low-temperature direct growth. Adv. Mater. 30, 1803109 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Nanosecond phase-transition dynamics in elemental tellurium. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2408725 (2024).

Brodsky, M. H., Gambino, R. J., Smith, J. E. & Yacoby, Y. The Raman spectrum of amorphous tellurium. Phys. Status Solidi 52, 609–614 (1972).

Yannopoulos, S. N. Structure and photo-induced effects in elemental chalcogens: a review on Raman scattering. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron 31, 7565–7595 (2020).

Cheng, Y. H., Teitelbaum, S. W., Gao, F. Y. & Nelson, K. A. Femtosecond laser amorphization of tellurium. Phys. Rev. B 98, 134112 (2018).

Ikemoto, H. & Miyanaga, T. Local structure of amorphous tellurium studied by EXAFS. J. Synchrotron Rad. 21, 409–412 (2014).

Joannopoulos, J. D., Schlüter, M. & Cohen, M. L. Electronic structure of trigonal and amorphous Se and Te. Phys. Rev. B 11, 2186 (1975).

Akola, J. & Jones, R. O. Structure and dynamics in amorphous tellurium and Te n clusters: a density functional study. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 85, 134103 (2012).

Qiao, C. et al. Structure, bonding nature and transition dynamics of amorphous Te. Scr. Mater. 202, 114011 (2021).

Lee, T. H. & Elliott, S. R. Hypervalency in amorphous chalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 13, 1458 (2022).

Wong, H.-S. P. et al. Phase change memory. Proc. IEEE 98, 2201–2227 (2010).

Yang, W., Hur, N., Lim, D. H., Jeong, H. & Suh, J. Heterogeneously structured phase-change materials and memory. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 050903 (2021).

Koo, Y. & Hwang, H. Zn1−xTex ovonic threshold switching device performance and its correlation to material parameters. Sci. Rep. 8, 11822 (2018).

Kastner, M., Adler, D. & Fritzsche, H. Valence-alternation model for localized gap states in lone-pair semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 37, 1504–1507 (1976).

Okuyama, K. & Kumagai, Y. Study of crystallization in amorphous tellurium films using resistivity measurements. Thin Solid Films 156, 345–350 (1988).

Sung, H.-J. et al. Microscopic origin of polarity-dependent VTH shift in amorphous chalcogenides for 3D self-selecting memory. Adv. Sci. 11, 2408028 (2024).

Fantini, P. et al. VT window model of the Single-chalcogenide Xpoint Memory (SXM). In 2024 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting. 1–4 (IEEE, 2024).

Yoo, J. et al. Threshold voltage drift in Te-based ovonic threshold switch devices under various operation conditions. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 41, 191–194 (2019).

Kabuyanagi, S. et al. Understanding of tunable selector performance in Si-Ge-As-Se OTS devices by extended percolation cluster model considering operation scheme and material design. In 2020 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology 1–2 (IEEE, 2020).

Ravsher, T. et al. Comprehensive performance and reliability assessment of se-based selector-only memory. In 2024 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS) 7A.5-1–7A.5-9 (IEEE, 2024).

Ielmini, D. & Zhang, Y. Evidence for trap-limited transport in the subthreshold conduction regime of chalcogenide glasses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 192102 (2007).

Koo, Y., Lee, S., Park, S., Yang, M. & Hwang, H. Simple binary ovonic threshold switching material SiTe and its excellent selector performance for high-density memory array application. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 38, 568–571 (2017).

Ishiguro, T. & Tanaka, T. Non-ohmic and oscillatory behaviours at strong electric field in tellurium. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 6, 864–874 (1967).

Ray, A. K., Swan, R. & Hogarth, C. A. Conduction mechanisms in amorphous tellurium films. J. Non Cryst. Solids 168, 150–156 (1994).

Kolobov, A. V. On the origin of p-type conductivity in amorphous chalcogenides. J. Non Cryst. Solids 198, 728–731 (1996).

Lee, J. et al. An artificial tactile neuron enabling spiking representation of stiffness and disease diagnosis. Adv. Mater. 34, 2201608 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Indium turns tellurium into an ovonic threshold switching selector via a stabilizing amorphous network. J. Mater. Chem. C. 12, 10118–10126 (2024).

Tauc, J. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous Ge and Si. Mat. Res. Bull. 3, 37–46 (1968).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. An updated version of wannier90: a tool for obtaining maximally-localized Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 2309–2310 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National R&D Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2024-00336695, RS-2025-12602968, and RS-2025-23323754). This research was also partially supported by the National Supercomputing Center with supercomputing resources including technical support (KSC-2024-CRE-0583) for T.H.L. J.S. acknowledges support by Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd (IO251216-14657-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. and N.H. conceived the idea and designed the experiment. N.H. performed most of the experiments, including material deposition, analysis, optimized device fabrication, electrical measurement, and TEM characterization. S.K. mainly supported this work, including sputtering and electrical measurement. T.H.L. and Y.B.P. constructed and characterized AIMD simulations. C.K. grew ALD-Te thin films and supported KPFM analysis. S.Y. supported cryogenic measurement. Y.C. supported device fabrication. J.S. and N.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Min Zhu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hur, N., Kim, S., Park, Y.B. et al. On-device cryogenic quenching enables robust amorphous tellurium for threshold switching. Nat Commun 17, 1509 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68223-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68223-0