Abstract

Tree bark represents a large global carbon stock, comprising 2-20 % of woody biomass, and plays a distinct role in carbon and nutrient cycling. It is poorly understood how different abiotic and biotic drivers contribute to bark decomposition globally, or how these relationships play out in a changing climate. Here, we compile a global dataset to estimate the spatial variability of current bark decomposition rates (k values) and employ three machine learning approaches to project the response of k in future climate scenarios. We find that, globally, bark decomposes 2.9 times faster than the rate previously estimated for tree trunks (including bark). Mean k values increase latitudinally from 0.093 year-1 in the boreal region to 1.339 year-1 in the tropical region. Angiosperm bark decomposes faster (k = 0.450 year-1) than gymnosperm bark (0.198 year-1). Climate, especially mean annual temperature and mean annual precipitation, and bark phosphorus concentration, are the predominant factors driving bark decomposition. Four leading future climate scenarios predict bark decomposition to slow down in warm and wet regions and accelerate in cold and dry regions. Our results highlight the importance of considering bark decomposition in carbon cycling models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tree bark, the outermost layer of the tree trunk in woody plants, constitutes a critical component of woody plant biomass, accounting for a non-trivial 2–20% of stem biomass1,2. Bark is also vital to the ecosystem nutrient cycles, contributing a third of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) concentrations in stems3,4; and probably releasing these nutrients faster after death because of (on average) faster decomposition rate compared to xylem5,6,7. While the role of bark in carbon (C) and nutrient cycling during the life of trees is well-established8, its ecological importance extends further, particularly after tree or woody stem death9. Decomposing bark not only promotes nutrient availability but also enhances biodiversity, increases habitat heterogeneity, and diversifies trophic niches, thus fulfilling multiple functions in the ecosystem10,11,12. However, the response of bark decomposition to abiotic and biotic drivers, especially in the context of climate change, remains poorly understood compared to insight into decomposition of other plant organs such as leaves and shoots13. It is crucial to comprehend the contributions of these drivers of bark decomposition to accurately predict how future climate will impact forest ecosystems and their carbon budgets.

In most biomes, decomposition is a biologically driven process, mainly carried out by microbes and soil fauna, which is jointly regulated by substrate quality and climate14,15,16. The type of dominant decomposers involved and the assembly history may have significant and long-lasting impacts on the decomposition process of bark and even the whole deadwood17,18. Bark persistence can range from several years to decades7,19, which is tree species- and region-specific. For example, deadwood in tropical forests tends to decompose faster than that in temperate or high-altitude regions, partly due to high activity of termites, which have a strong and positive temperature sensitivity20. However, most research has primarily focused on how the substrate quality-related factors, such as tree species, diameter, and decomposition stage7,21, affect decomposer activity, while little attention has been paid to the effects of climate and their interactions with the aforementioned factors. This is likely due to the climate-driven functional convergence of tree species (and their substrate quality) within the same region, where the effects of climate and substrate quality are often closely linked, making it difficult to differentiate their relative importance. At a high taxonomic level, for example, gymnosperms, which predominate in cool and cold biomes, had generally poorly decomposable bark compared to angiosperms in a temperate study1, probably partly due to their high contents of extracts (e.g., resins) in bark. Another reason lies in the limitations of experimental design: bark decomposition study of multiple tree species is usually carried out at a single site, making it difficult to compare decomposition rates and disentangle their drivers at a broader scale. Disentangling the drivers of bark decomposition from regional to global scale through a comprehensive analysis would allow us to better estimate bark decomposition in regions with limited observations, improve the accuracy of predictions about bark’s decomposition response to future climate change, and help anticipate the consequences for carbon dynamics and ecosystem functioning. However, no research has systematically investigated the separate and combined contributions of different drivers of decomposition related to both bark substrate quality and climate at the global scale.

Temperature and precipitation are among the most important climate factors driving tree growth and tree decomposition22,23. Global warming and the spatial redistribution of precipitation may affect bark decomposition rates or patterns by altering tree species composition, substrate quality, decomposer community composition, and decomposer activity24,25. For example, deadwood in dryland decomposed faster with increased precipitation due to the higher decomposer activity and different nutrient status26. However, such responses have not been studied for bark. Although temperature projections show general agreement in the global warming trends, precipitation projections exhibit significant regional uncertainties27, leading to regionally distinct wetting or drying conditions. This spatial heterogeneity in climate projections suggests that the response of bark decomposition to climate change will vary across regions, depending on local changes in temperature and precipitation13. For instance, decomposer activity would be greatly stimulated in high-latitude or high-altitude regions, where warmer and wetter conditions are expected globally under climate change28. Meanwhile, decomposers in arid or semi-arid regions would be challenged by the increased high temperature extremes and decreased precipitation29,30. Identifying the key factors driving bark decomposition in different climate regions is essential for accurately predicting potential responses of forest ecosystems to future climate scenarios. This is not only a significant scientific issue but also a prerequisite for developing forest management and policy.

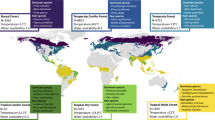

Using 350 records across biomes, including tropical, subtropical, temperate, and boreal, where woody plants occur (Fig. 1a), we investigate the spatial variation of bark decomposition and identify key drivers across and within climate regions. We subsequently project how bark decomposition will respond to the changing climate (Fig. S1). First, we use three climate variables and four substrate quality related variables as input factors in three widely used machine learning models, i.e., random forest (RF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and support vector machines (SVM) (see Methods, Machine learning), and rank the models’ performance by comparing their R2 and Mean Squared Error (MSE) scores. Next, we assess the relative importance of climate factors and substrate quality in driving bark decomposition. The machine learning results show that climate factors have stronger effects than substrate quality on bark decomposition at the global scale. Thus, we project how bark decomposition rates would change in response to global climate change. We hypothesize that (1) bark decomposition rates and their drivers will vary significantly across regions due to differences in both climate and substrate quality of different tree taxa and functional groups, and their interactions; (2) the responses of bark decomposition to climate change will vary spatially as the response pattern of temperature and precipitation to climate change will itself depend on the current local hydrothermal conditions.

a Geographic distribution of the locations included in this analysis. Different shapes indicate the types of biome where the specific study sites are located, and different colors indicate the four functional groups. The size of the circle is proportional to the sample size for bark decomposition. b The spatial distributions of locations across the Whittaker biomes along climatic gradients. Bark k (Mean ± SE, year−1) varies with (c) biomes and (d) functional groups at the global scale. Values attached to each bar indicate the n number of observations in each category. Bars that do not share any letters in (c) or (d) are significantly different from one another at level p < 0.05.

Results

Global pattern and drivers of bark decomposition

The global averaged bark k value was 0.362 year−1 (ranging from 0.001 year−1 to 5.495 year−1) under the current climate, which varied significantly (p < 0.05) among biomes and functional groups (Fig. 1c, d). Bark decomposition showed a latitudinal gradient, being faster in tropical regions (k = 1.339 ± 0.148 year−1) than that in other regions, with the lowest bark k values in boreal regions (k = 0.093 ± 0.013 year−1). Bark k at the major clade level contributed most to the differences among functional groups and was much higher for angiosperms (0.450 ± 0.050 year−1) than for gymnosperms (0.198 ± 0.033 year−1). Decomposition rates were notably higher in Angiosperm-Deciduous (AD, k = 0.614 ± 0.084 year−1) bark as compared with Angiosperm-Evergreen (AE, k = 0.236 ± 0.017 year−1) bark, and higher in Gymnosperm-Evergreen (GE, k = 0.214 ± 0.038 year−1) bark than in Gymnosperm-Deciduous (GD, k = 0.086 ± 0.034 year−1) bark.

By comparing the R2 and MSE scores of the RF, XGBoost, and SVM models (Table 1), we found that all three models showed a generally good and broadly similar performance. The RF model had the best fit to the data, and we therefore employed it for the subsequent analyses. The RF model yielded significant relationships between bark k values and all seven predictor variables (Fig. 2a, Table S2) across all tree species. Mean annual temperature (MAT) and mean annual precipitation (MAP) showed the highest relative importance values (25.3% and 17.7%, respectively) and the strongest positive Spearman correlation coefficients (r = 0.551 and r = 0.328, respectively, p < 0.001, Fig. 2c) in explaining bark k while bark phosphorus (P) also had a rather strong positive correlation (r = 0.289, p < 0.001).

a The relative importance of variables explaining variation in bark decay constant (k, year−1) globally using a Random Forest model. Dark and light green bars indicate climate-related factors and bark substrate quality, respectively. b Relationships between observed and predicted bark k values based on the Random Forest model. The red dashed line is the 1:1 line. c Spearman correlation coefficients between bark k values and variables representing climate and bark traits. The circle size is proportional to the coefficients. Positive correlations are displayed in red and negative correlations in purple.

Climate and trait effects on bark decomposition across climate regions

Since climate had the strongest effect on bark k, we further quantified the influence of the variables across different climate regions. The averaged bark k values in warm and wet regions were 0.586 (±0.061) year−1 and 0.580 (±0.064) year−1, which were 5.1 and 4.1 times higher than the values in cold (0.116 ± 0.013 year−1) and dry regions (0.142 ± 0.013 year−1), respectively (Fig. 3). In both warm (Fig. 4a) and wet regions (Fig. 4c), the RF model indicated that bark P concentration had the strongest effect on bark k, followed by MAT (Table S4). Spearman correlation coefficients also revealed a significant (p < 0.05) positive relationship between bark k and bark nitrogen (N) concentration (r = 0.284 and r = 0.256 for warm and wet regions, respectively), as well as bark carbon (C) concentration (r = 0.333 and r = 0.173, respectively). A significant (p < 0.05) negative relationship was found between bark C/N ratio (r = −0.252 and r = −0.220, respectively) and bark k. In both cold (Fig. 4b) and dry regions (Fig. 4d), the RF model indicated that MAT had the strongest effect on bark k (Table S4). Spearman correlation coefficients also revealed a significant (p < 0.05) positive relationship between bark k and MAP (r = 0.198 and r = 0.487 in the cold and dry regions, respectively), whereas a significant (p < 0.05) negative relationship was observed between bark k and bark C concentration (r = −0.207 and r = −0.255, respectively).

Climate region is divided by (a) median mean annual temperature (MAT, 13 °C) or (b) median mean annual precipitation (MAP, 1100 mm). The bar plots attached in the bottom left indicate mean bark k (mean ± SE) in each climate region. The sample size (n numbers) for each group is given on top of each bar. Circle size is proportional to the bark k values.

The results of the Random Forest model and Spearman correlation analysis are conducted in (a) warm region, (b) cold region, (c) wet region, and (d) dry region, respectively. Dark and light green bars indicate climate-related factors and substrate quality, respectively. The red and purple circles are the Spearman correlation coefficients between predictive variables and bark k. The circle size is proportional to the coefficients. Circles in red and purple indicate positive and negative Spearman’s correlation. EL elevation, C_N carbon to nitrogen ratio.

Bark k predictions in different climate regions

The projected responses of bark k in the future climate scenarios also vary across climate regions (Figs. S2, S3, S4). The global averaged bark k by the end of this century is projected at 0.386, 0.376, 0.380, and 0.374 year−1 under the scenarios of SSP 1-2.6, SSP 2-4.5, SSP 3-7.0, and SSP 5-8.5, respectively. Based on RF model prediction, the bark k averages in the warm region (Fig. 5a) and wet region (Fig. 5c) are projected to decrease under all four SSP scenarios. By the end of this century (Fig. 5, S2), bark k is expected to decline from 0.586 ± 0.061 year−1 to 0.494 ± 0.012 year−1 (\(\Delta k\%\) = −15.7%) in the warm region, and to decline from 0.580 ± 0.064 year−1 to 0.484 ± 0.013 year−1 (\(\Delta k\%=\) −16.6%) in the wet region. In contrast, the bark k in cold and dry regions is projected to increase in all four SSP scenarios. By the end of this century (Figs. 5b, d, S2), bark k in the cold region is expected to rise from 0.116 ( ± 0.013) year−1 to 0.260 ± 0.006 year−1 (\(\Delta k\%=\) 124.1%), and to rise from 0.142 ± 0.013 year−1 to 0.273 ± 0.006 year−1 (\(\Delta k\%=\) 92.3%) in the dry region.

Difference (mean ± SE, Δk) of predicted bark k values (year−1) and current observed bark k values (year−1) are calculated in (a) warm region, (b) cold region, (c) wet region, and (d) dry region, respectively. Four Shared Socio-economic Pathways (SSPs) for the periods I (2021–2040), II (2041–2060), III (2061–2080), and IV (2081–2100) are simulated in each climate region. Positive values (Δk > 0) indicate increased bark decay rate and negative values (Δk < 0) indicate decreased bark decay rates under future climate scenarios. n numbers of each prediction (i.e., one bar) are attached in the four climate regions, respectively.

Discussion

Understanding the spatial variation of bark decomposition rates globally and identifying the key drivers controlling bark decomposition are central to disentangle the roles of bark decomposition in carbon dynamics and ecosystem functioning. This will enable us to anticipate the consequences of global climate change for these roles. In our study, we estimated bark decomposition rates (in terms of bark k) globally across biomes, major taxa, and functional groups. Our results showed, first, that climatic factors, specifically MAT and MAP, have stronger effects on bark k values than bark substrate quality at the global scale, although bark P was also important as a predictor. Second, the relative importance of climate and substrate quality as predictors differed spatially. We further revealed that the response of bark k to future climate was spatially restricted, with the directions depending on the current hydrothermal conditions, and the strength depending only slightly on four of the leading future climate scenarios. Although bark k in different climate regions would converge by the end of this century, bark decomposition rates in warm and wet regions are still expected to remain faster than those in cold and dry regions.

Consideration of bark decomposition

Previous studies highlighted that bark generally decomposes faster than xylem, and that bark cover could significantly affect the decomposition process of xylem9,30,31,32. In comparison to a meta-analysis estimating the k values of deadwood (i.e., including both bark and xylem), our estimated global mean bark k (0.362 year−1) is 2.9 times higher (k = 0.13 year−1)33. The highest bark k observed (5.495 year−1) is 4.6 times higher than the highest deadwood k (1.19 year−1). This difference can be understood from previous studies demonstrating substantial differences in the structure and chemical composition of bark and xylem7,18,34, both at the start of decomposition and throughout the process. Chang et al.35 further showed that bark and xylem respond differently to environmental disturbance (i.e., forest gaps) with variations in both decomposition rate magnitude and decomposition pattern. Additionally, bark decomposition rate drives the decomposition process of the underlying xylem via mediating microclimate and substrate quality36,37. For example, the contribution of termites to xylem consumption was closely related to the bark mass loss in the subtropical region32. Thus, bark decomposition dynamics should be considered separately.

Bark decomposition is a complex, multi-stage process involving the sequential degradation of inner bark and outer bark, and the duration of each stage depends on the relative proportions of inner bark and outer bark, as well as their substrate quality38. The asynchrony of decomposition within bark is primarily due to the distinct origins of inner bark (derived from the vascular cambium), which functions as photosynthate transport and storage, and outer bark (derived from the phellogen), which serves a protective role. Understanding how the structural and functional differences between inner and outer bark influence the decomposition process would provide valuable insights into bark decomposition mechanisms38. Bark attached to the tree trunk and bark separated from the tree trunk are both commonly seen on the forest floor, and the latter is more exposed to the decomposer organisms and sensitive to the environmental flux. Thus, bark status might show contrasting decomposition processes. Our study found an overall weak effect of bark status on decomposition (Fig. S5) because the effects could be positive, neutral, or negative, which was influenced by factors such as tree species, diameter, and decay stage9. However, little information about these factors was given in the published articles, thus this limits further examination. We encourage further researchers to put more emphasis on the bark status impacts and to record the factors mentioned above to help unravel and understand the mechanisms of the bark/deadwood decomposition process.

Decomposition drivers vary with climate regions

Biodegradation by microbes and invertebrates is the main pathway of decomposition in most ecosystems and is primarily driven by climate and substrate quality22. In our study, we also found both climate and bark traits had a significant influence on bark decomposition. The RF models revealed that MAT and MAP, as related to geographic location and topography (altitude), are the key abiotic determinants of bark decomposition rates on the global scale, which is consistent with the classic decomposition theory22. Furthermore, we found that the relative importance of climate versus bark traits varied with regional climatic conditions (i.e., MAT or MAP), which can be partly explained by the spatial scale theory39. Notably, we also identified the specific drivers that regulate bark decomposition in different climate regions.

Our results suggested that the hydrothermal condition is fundamental to bark decomposition, followed by the nutrient status. In our study, bark k values show a strong positive correlation with the bark nutrient concentration, especially bark P concentration, in warm and wet regions. One possible reason is that the decomposer organisms tend to experience a faster growth rate and a higher metabolic rate in these regions, resulting in a high demand for nutrients. Another explanation is that these two regions are usually environmentally P-limited due to the imbalance between the slow rate of rock weathering and high demand of P absorption, and because of the generally high nutrient leaching rate40,41. Conversely, in regions with low MAT and/or MAP, the decomposers are typically exposed to harsh hydrothermal conditions that suppress their activity and may reduce their survival, making bark traits a minor driver of bark decomposition compared to climate. A study measuring aspen bark decomposition rate42 correspondingly found that the decomposition rate was mostly enhanced by the addition of N and P, with the highest incubation temperature of 22 °C. Incorporating the hierarchically ordered drivers, considering spatial scale, and weighting the dominant drivers in different climate regions could significantly improve the accuracy of global predictive decomposition models. This would also benefit high-resolution mapping of global bark decomposition rates. Such analyses could provide more accurate estimates of carbon turnover rates and habitat loss due to bark decomposition in forest ecosystems.

Bark P concentrations best predict the decomposition rates

Although climate factors are stronger predictors of bark decomposition rates, bark traits still play an important role in explaining variations in bark decomposition rates. We found that several initial bark traits—in particular, P concentration followed by N concentration - are important predictors for bark decomposition rates both at global and regional scales. This is likely because decomposer activity in deadwood is often either N-limited or P-limited (Fig. S6)43. Previous research suggests that the N/P ratio of decomposing deadwood converges to a value around 2044, a process largely influenced by decomposer activity. While both N and P concentrations may increase their translocation into deadwood by wood-decomposing fungi during decomposition43, N accumulation could additionally be stimulated by biological N fixation45. Our results suggest that bark decomposition is generally P-limited both at global and regional scales, but mostly within warm and wet regions. A meta-analysis4 summarizing global bark N and P concentrations also observed their negative trends with latitude, which aligns with our findings. Furthermore, they reported that the global mean bark N/P ratio is approximately 19 and remains relatively constant across latitudes. Based on these patterns, we infer that the living bark N/P ratio may not serve as a reliable predictor of bark decomposition rate.

To improve our understanding of the bark decomposition mechanism, we suggest applying multi-dimensional stoichiometric theory and analysis in further research. Compared with the relatively poor substrate quality of xylem, the chemical composition and nutrient concentration in living bark are less influenced by the local environment (e.g., soil nutrient availability)3. Our study has revealed a strong relationship between bark C, N, P, and decomposition rates, and some sporadic studies have reported micro-elements in bark to be important for decomposition. For instance, manganese (Mn) is vital for synthesizing lignin-degrading enzymes like manganese peroxidase (MnP), produced by white-rot fungi46,47. Furthermore, bark physical traits, such as thickness, density, texture, and persistence, have been proved to be important filters for soil fauna decomposers32,48. However, due to the limited studies that reported both bark decomposition and micro-elements or physical traits, we were unable to assess them in our analysis. Studies disentangling the effects of these physical and chemical traits on bark decomposition are encouraged.

The consequence of bark decomposition to climate change is spatially dependent

We predicted that, by the end of this century, bark decomposition rate would increase by 124.1% in cold regions and 92.3% in dry regions, respectively. Emerging evidence suggests that deadwood is a major contributor to soil organic matter, significantly influencing soil properties49,50,51such as pH, moisture content, nutrient levels, effective caption exchange capacity, base saturation, and available molybdenum-reactive P. Studies in temperate and subtropical forests also found that the effects of deadwood on soil properties and soil organisms diminish during the mid-decomposition stage (ca 12–60 years)50,52, which is mostly the barkless stage. This supports the view that bark plays a key role in deadwood function, likely due to its higher nutrient content and faster decomposition rate compared to xylem. Furthermore, the bark of deadwood exhibits greater chemical variation across tree species than xylem35. However, most studies have conflated the contribution of these two tissues, with the exception of Almeida et al.53, who clearly addressed the pathways of bark decomposition in controlling soil organic matter formation. This ambiguity has hindered our ability to accurately project bark decomposition dynamics in response to future climate change.

Our results suggested that bark litter will exhibit accelerated future decomposition (i.e., a shorter persistence in the ecosystem) in cold and dry regions, where bark-associated biodiversity would face the risk of habitat loss. Besides nursing the organisms living in the decaying bark, bark cover could also alter the assemblage history of both beneath (the xylem as well) and on-bark organisms by regulating microclimate and substrate quality12,54. For example, diverse bryophytes such as mat-forming or wet-forming (e.g., Lophocolea) and cushion-forming (e.g., Lepidoziaceae) types are widely found on bark55. Together, bryophyte mats and decomposing bark support a diverse array of invertebrates (collectively referred to as bryofauna), which include protozoa, nematoda, annelida, and arthropoda, as well as fungi, such as nematode-trapping and saprotrophic species55. Bark in cold and dry regions usually provides critical shelters for species that are sensitive to low temperature or low air humidity (e.g., mites).

In conclusion, this study globally synthesized the currently available data for bark decomposition rates and clearly identified the key factors driving bark decomposition across different climate regions. We found that climate factors are more influential than bark substrate quality itself in determining bark decomposition rates at the global scale. However, regional climate is crucial: in the regions with suitable temperature and abundant rainfall, bark decomposition is primarily driven by bark P concentration, while in the regions with poor hydrothermal conditions, temperature is the dominant factor driving decomposer activity. Based on our estimation, the global average bark decomposition is 2.9 times faster than deadwood (i.e., xylem with bark) decomposition33, with the highest observed bark decomposition rate surpassing the observed highest deadwood decomposition rate by 4.6 times. Our findings are consistent with a previous study56 that documented the stepwise deadwood decomposition process; we further revealed that bark plays a pivotal role in controlling the whole deadwood decomposition rate in the early stages, followed by xylem. We also found that the response of bark decomposition rates to climate change is itself climate-dependent, leading to spatial variation in the response direction and magnitude. These results emphasize the importance of integrating bark into predictive models to achieve accurate forecasts of the global carbon cycle.

Methods

Data assembly

We compiled a global database of bark decomposition rate for woody plants from published literature using Web of Science (http://apps.webofknowledge.com), Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com), and the National Knowledge Infrastructure Database (http://cnki.net). We used the combination of keywords (bark) AND (decomposition rate OR decay rate OR mass loss OR density loss OR decay constant) AND (twig OR branch OR stem OR woody debris OR deadwood OR dead wood OR dead tree). We further filtered the literature by reviewing the abstracts and experimental designs to exclude studies that (1) were conducted in the laboratory; (2) did not provide latitude, longitude and elevation information; (3) involved bark or woody plants that were attacked by pest or pathogen before death; (4) involved woody plants died unnaturally such as due to drought, fire, or other disturbances; (5) only included control records of bark decomposition rates if bark was decomposed with treatments such as fertilization, invertebrate exclusion (control: mesh size > 2 mm), or heating. Based on these criteria, we compiled a dataset that consists of 350 observations from 48 sites and 80 tree species (Fig. 1, see Table S1 for the full list).

There are two types of methodology (Table S1, methodology) of decomposition study in the literature: (1) For the studies using “chronosequence” method57, multiple decomposition rates were reported for different decomposition durations. As decomposition rates of different durations were measured for different logs, we extracted a unique record for each duration. (2) The studies using the ‘direct’ method7 determined decomposition rates by “direct” measurement of bark initial dry weight before decomposition and dry mass remaining after decomposition. Two types of bark material were recorded in the literature: (1) bark naturally attached to the tree trunk during decomposition and (2) bark detached from the tree trunk and decomposed as litter (Table S1, “bark status”). Data were extracted from the main text, tables, and digitized graphs of primary references. We used GetData Graph Digitizer (version 2.26) to extract raw data presented only in figures. Three linked databases were incorporated in this study: “decomposition rate”, “site” and “trait”. The detailed information of each database is below.

Decomposition rate

Bark decomposition is the transformative process by which complex organic compounds, such as cellulose and lignin, are catabolized into smaller units and ultimately mineralized58. Bark decomposition rate refers to the speed at which the bark and its residuals are broken down by respiration, fire, photodegradation, and physical degradation14,59. Consequently, the decomposition rate of bark could be expressed in the form of mass loss (mass loss/area, mass loss/length), volumetric loss, coverage loss, and thickness loss, etc. In our study, the “decomposition rate” database contains various measures of decomposition rates, including the decomposition rate constant (k values)60, mass loss, density loss, or thickness loss, from which k values could be calculated. All metrics of decomposition rates were converted to k values (Eq. 1) using the single negative exponential model because this model has been documented as the most useful and realistic biologically in decomposition study22. A larger k value indicates a greater proportional mass loss, volumetric loss, coverage loss, or thickness loss per unit time.

Y0 is the initial mass/density/thickness before decomposition started. Yt is the mass/density/thickness remaining after decomposition for a certain time duration t.

Site

In addition to bark k, we also compiled the “site” database, which includes geographic information (longitude, latitude, and elevation) and climate conditions for each observation. Temperature and water availability are the key climatic drivers in the classic decomposition model22. Considering the data availability at a global scale and the collinearity of climate variables, we chose the MAT and MAP to represent climate conditions for this study. The climate conditions for each observation (observational data) are extracted from the articles. For those articles in which the MAT and/or MAP are not provided, we filled in the missing data from WorldClim (https://worldclim.org/) using longitude and latitude information with a resolution of 2.5 arc-minutes. The added climate data are sourced from the observed monthly average data for the current period (1970–2000, WorldClim version 2.1).

Trait

Bark substrate quality is a key predictor for decomposition rate22. Bark elemental chemistry is likely more phylogenetically conserved than other commonly measured morphological and physiological traits61, and macro-elements tend to be more strongly linked to phylogeny than micro-elements62. Carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) are considered as the most basic elements in the ecological stoichiometry, which are also essential for tree growth and also for the metabolism of decomposer organisms4,63. Furthermore, empirical studies1,31 have revealed that bark decomposition rates varied with phylogeny. Thus, the third database, “trait” includes initial (pre-decomposition) bark traits (Fig. S6), including bark C, N, carbon to nitrogen ratio (C/N ratio), and P, and these traits were extracted and recorded when available in the literature or related publications from the same experimental setup. Authors were contacted if it was clear that the desired data were collected but not reported. Otherwise, we obtained the data of the same tree species from the TRY Plant Trait Database (try-db.org) because these macro-elements exhibited a stronger taxonomic conservatism than environmental control, exhibiting a narrow range of internal concentrations64.

Data analysis

Division of climate regions

To better understand the drivers of bark decomposition at different climate regions, we further divided the 48 sites into warm region and cold region based on the median MAT value (13 °C), or divided the sites into wet region and dry region based on the median MAP value (1100 mm)15, hereafter named as the “dichotomous approach”. Alternatively, we divided the sites into four groups (Fig. S7) based on (1) whether they were warmer or colder than the median MAT value, and (2) whether they were wetter or drier than the median MAP value. We found significant differences in bark k among the four groups (Fig. S7). However, we encountered difficulties in the in-depth analysis of the warm-dry region and cold-wet region because of the limited sample size. To improve the robustness of our analysis, given the generally linear relationship (r = 0.600, p < 0.001, Pearson’s correlation) between MAT and MAP, we selected the dichotomous approach for subsequent analysis.

General analysis

The missing observational MAT and MAP values of each plot were extracted using ArcGis (version 10.7) after downloading the raster data from WorldClim. All the other analysis were performed in R (version 4.4.1, https://www.r-project.org/). Before performing the analyses, we tested the collinearity of the climate and trait variables using the “vif” function from the R package “car”. The “GLM” function from the “stats” package was used to test the effects of biomes and functional types on bark k. The Shapiro–Wilk test indicated that the data were non-normally distributed, so we calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between each variable and bark k using the “cor.test” function from the “psych” package. To test the differences in bark k and bark traits among biomes, functional groups, and climate regions, the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis Test applying “kruskal.test” in “coin” package was used. If there is significant difference at p < 0.05 level, we further applied the “dunn.test” in “dunn.test” package for post-hoc analysis.

Machine learning

To identify the best fit model for predicting bark k and projecting the potential response of bark k in different climate regions, we applied three machine learning approaches: RF, eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and SVM. Each approach represents distinct modeling strategies with different strengths in handling non-linearity, variable interactions, and generalization. RF is an ensemble learning method based on the bagging principle, where multiple decision trees are constructed using bootstrapped samples and random feature subsets65. XGBoost is a powerful and scalable machine learning algorithm based on gradient boosting decision trees66. SVMs are margin-based models that aim to find an optimal hyperplane for classification or regression67.

Climate factors (MAT, MAP), elevation, bark traits (C, N, P, and C/N ratio), and bark status (see Table S1) were assigned as explanatory variables in the three models. For each model, we used 10-fold cross-validation in the training dataset to test the model performance and to help reduce overfitting. 70% of the observations were set as the training dataset, and the remaining 30% were used as the prediction dataset. First, R2 and MSE were calculated to estimate the goodness of fits to the model (Table 1). The lower MSE and the higher R2 scores indicated which model performed better. We found an increase in R2 and a decrease in MSE if we excluded bark status as the explanatory variable in the training model, which indicated a better model performance (Fig. S5). Thus, we decided to use climate factors and bark traits as explanatory variables in the processes of machine learning. Then, we evaluated the relative effects of climate factors and bark traits that affected the bark decomposition rates based on the estimation of the three models, respectively. The functions and packages used for each machine learning model are listed in Table S3.

Second, we projected bark k under different climate conditions using the model with the lowest MSE and the highest R2 scores. To better represent plausible trajectories of future conditions of temperature and precipitation, we used four illustrative Shared Socio-economic Pathways scenarios (i.e., SSP scenarios) beyond the current scenarios. SSP scenarios ranged from sustainability-focused pathways (SSP 1-2.6) to very high greenhouse gas emissions scenarios (SSP 5-8.5), with SSP 2-4.5 and SSP 3-7.0 in between, instructed by Coupled Model Intercomparison Projects (CIMP6). Bark traits and climate factors were assigned as explanatory variables in the predicting models of machine learning. We assumed that bark traits and elevation would not change during the research period, whereas MAT and MAP would change due to the different climate conditions of the four SSP scenarios. The future climate data was categorized by four different SSPs scenarios for the following time periods: 2021–2040 (near-term), 2041–2060 (mid-term I), 2061–2080 (mid-term II), and 2081–2100 (long-term). Third, we calculated the changes in bark k (Δk) and the relative changes in bark k (Δk%) by the end of this century (Figs. 5, S3, S4) based on Eq. 2 and Eq. 3, respectively.

kpredicted is the model projected bark decomposition constant by the end of this century under different scenarios. kcurrent is the observational bark decomposition constant sourced from the literature (Table 1).

Bias correction for future climate data

The projected temperature and precipitation data were sourced from the Scenarios Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) of CMIP6. We adopted the average values of the available outputs from 28 distinct Earth System Models (ESMs, Table S5, Fig. S8) at the monthly resolution. Since the outputs of ESMs models are generally biased compared to observations68 and these outputs are at coarse resolutions, we bias-corrected and downscaled the temperature and precipitation outputs before we added the values to the predicting model of machine learnings. Briefly, we utilized a trend-preserving bias correction method68,69 to the monthly mean temperature and precipitation data using the observation data in TerraClimate70 as baseline climate (period 1985–2014, T0). We applied an additive correction approach (Eq. 4) to correct the monthly mean temperature values. Given the positive constraint on precipitation data, we applied a multiplicative correction approach (Eq. 5) to correct the monthly mean precipitation values.

\({\widetilde{{tem}}}_{t,{m}}^{{sim}}\) and \({{tem}}_{t,m}^{{sim}}\) are the corrected and uncorrected monthly mean temperature for the period t at the 1/24° (~4-km) resolution. \({C}_{m}\) is an additive factor for each month m {m\(\,\in\)Z+, m\(\le\)12}, which represents the long-term differences between the simulated \({{tem}}_{{T}_{0},m}^{{sim}}\) and observed \({{tem}}_{{T}_{0},m}^{{obs}}\) monthly mean temperature during the reference period T0.

\({\widetilde{{pre}}}_{t,{m}}^{{sim}}\) and \({{pre}}_{t,m}^{{sim}}\) are the corrected and uncorrected monthly mean precipitation for period t at the 1/24° (~ 4-km) resolution. \({C}_{m}\) is an additive factor for each month m {m\(\,\in\)Z+, m\(\le\)12}, which represents the long-term differences between the simulated \({{pre\,}}_{{T}_{0},m}^{{sim}}\) and observed \({{pre}}_{{T}_{0},m}^{{obs}}\) monthly mean temperature during the reference period T0. For detailed information about the bias correction and downscaling procedure see Xu et al.69.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Bark traits data are available from public database TRY Plant Trait Database (https://www.try-db.org/TryWeb/Home.php). The historical and predicted climate data are available at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6. The observational climate dataset is available at ref. 70 (https://www.nature.com/articles/sdata2017191). Data for all figures and tables are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28876976.

Code availability

The analysis scripts are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28876976.

References

Chang, C. et al. Methodology matters for comparing coarse wood and bark decay rates across tree species. Methods Ecol. Evol. 11, 828–838 (2020).

Neumann, M. & Lawes, M. J. Quantifying carbon in tree bark: the importance of bark morphology and tree size. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 646–654 (2021).

Rosell, J. A. et al. Inner bark vs sapwood is the main driver of nitrogen and phosphorus allocation in stems and roots across three tropical woody plant communities. N. Phytol. 239, 1665–1678 (2023).

Gong, H. et al. Global patterns and controlling factors of tree bark C:N:P stoichiometry in forest ecosystems consistent with biogeochemical niche hypothesis. N. Phytol. 244, 1303–1314 (2024).

Krankina, O. N., Harmon, M. E. & Griazkin, A. V. Nutrient stores and dynamics of woody detritus in a boreal forest: modeling potential implications at the stand level. Can. J. Res. 29, 20–32 (1999).

Johnson, C. E., Siccama, T. G., Denny, E. G., Koppers, M. M. & Vogt, D. J. In situ decomposition of northern hardwood tree boles: decay rates and nutrient dynamics in wood and bark. Can. J. Res. 44, 1515–1524 (2014).

Dossa, G. G., Paudel, E., Cao, K., Schaefer, D. & Harrison, R. D. Factors controlling bark decomposition and its role in wood decomposition in five tropical tree species. Sci. Rep. 6, 34153 (2016).

Rosell, J. A., Gleason, S., Méndez-Alonzo, R., Chang, Y. & Westoby, M. Bark functional ecology: evidence for tradeoffs, functional coordination, and environment producing bark diversity. N. Phytol. 201, 486–497 (2014).

Dossa, G. G. O. et al. The cover uncovered: bark control over wood decomposition. J. Ecol. 106, 2147–2160 (2018).

Kushnevskaya, H., Mirin, D. & Shorohova, E. Patterns of epixylic vegetation on spruce logs in late-successional boreal forests.Ecol. Manag. 250, 25–33 (2007).

Persson, Y., Ihrmark, K. & Stenlid, J. Do bark beetles facilitate the establishment of rot fungi in Norway spruce? Fungal Ecol. 4, 262–269 (2011).

Kazartsev, I., Shorohova, E., Kapitsa, E. & Kushnevskaya, H. Decaying Picea abies log bark hosts diverse fungal communities. Fungal Ecol. 33, 1–12 (2018).

Chen, Z. et al. Climate warming accelerates carbon release from foliar litter-A global synthesis. Glob. Chang. Biol. 30, e17350 (2024).

Cornwell, W. K. et al. Plant traits and wood fates across the globe: rotted, burned, or consumed? Glob. Chang. Biol. 15, 2431–2449 (2009).

Bradford, M. A. et al. Understanding the dominant controls on litter decomposition. J. Ecol. 104, 229–238 (2015).

Seibold, S. et al. The contribution of insects to global forest deadwood decomposition. Nature 597, 77–81 (2021).

Weslien, J., Djupstrom, L. B., Schroeder, M. & Widenfalk, O. Long-term priority effects among insects and fungi colonizing decaying wood. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1155–1162 (2011).

Yang, S. et al. Stem decomposition of temperate tree species is determined by stem traits and fungal community composition during early stem decay. J. Ecol. 112, 1240–1255 (2024).

Shorohova, E. & Kapitsa, E. Mineralization and fragmentation rates of bark attached to logs in a northern boreal forest.Ecol. Manag. 315, 185–190 (2014).

Zanne, A. E. et al. Termite sensitivity to temperature affects global wood decay rates. Science 377, 1440–1444 (2022).

Chang, C. et al. Reciprocal bark exchange helps to disentangle tree species-dependent bark and wood trait effects on invertebrate diversity. J. Ecol. 111, 125–138 (2023).

Harmon, M. E. et al. Ecology of coarse woody debris in temperate ecosystems. Adv. Ecol. Res. 15, 133–302 (1986).

Nemani, R. R. et al. Climate-driven increases in global terrestrial net primary production from 1982 to 1999. Science 300, 1560–1563 (2003).

Miyamoto, Y., Sakai, A., Hattori, M. & Nara, K. Strong effect of climate on ectomycorrhizal fungal composition: evidence from range overlap between two mountains. ISME J. 9, 1870–1879 (2015).

van Tiel, N. et al. Regional uniqueness of tree species composition and response to forest loss and climate change. Nat. Commun. 15, 4375 (2024).

Yu, W. et al. Precipitation and diameter affect wood decomposition both directly and indirectly via deadwood traits and position. Soil Biol. Biochem. 199, 109604 (2024).

Trancoso, R. et al. Significantly wetter or drier future conditions for one to two thirds of the world’s population. Nat. Commun. 15, 483 (2024).

Group MRIEW. Elevation-dependent warming in mountain regions of the world. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 424–430 (2015).

Zaitchik, B. F., Rodell, M., Biasutti, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Wetting and drying trends under climate change. Nat. Water 1, 502–513 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Wetting-warming climate increases ecosystem carbon use efficiency of Chinese arid and semi-arid ecosystem. Agric. Meteorol. 351, 110018 (2024).

Shorohova, E. et al. Tree species traits are the predominant control on the decomposition rate of tree log bark in a mesic old-growth boreal forest.Ecol. Manag. 377, 36–45 (2016).

Tuo, B. et al. Influences of the bark economics spectrum and positive termite feedback on bark and xylem decomposition. Ecology 102, e03480 (2021).

Hu, Z. et al. Traits drive global wood decomposition rates more than climate. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 5259–5269 (2018).

Jones, J. M., Heineman, K. D. & Dalling, J. W. Soil and species effects on bark nutrient storage in a premontane tropical forest. Plant Soil 438, 347–360 (2019).

Chang, C. et al. Tissue type and location within forest together regulate decay trajectories of Abies faxoniana logs at early and mid-decay stage.Ecol. Manag. 475, 118411 (2020).

Hagge, J. et al. Bark coverage shifts assembly processes of microbial decomposer communities in dead wood. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 286, 20191744 (2019).

Jones, J. M., Heath, K. D., Ferrer, A., Dalling, J. W. & Timothy Paine, C. E. Habitat-specific effects of bark on wood decomposition: influences of fragmentation, nitrogen concentration and microbial community composition. Funct. Ecol. 34, 1123–1133 (2020).

Lin, L. et al. Considering inner and outer bark as distinctive tissues helps to disentangle the effects of bark traits on decomposition. J. Ecol. 110, 2359–2373 (2022).

Bradford, M. A. et al. Climate fails to predict wood decomposition at regional scales. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 625–630 (2014).

Dijkstra, F. A. et al. Climate change alters stoichiometry of phosphorus and nitrogen in a semiarid grassland. N. Phytol. 196, 807–815 (2012).

Ziegler, S. E. et al. Biogeochemical evidence raises questions on the longevity of warming-induced growth enhancements in wet boreal forests. Ecosphere 15, e70109 (2024).

Kurganova, I., Lopes de Gerenyu, V., Galibina, N., Kapitsa, E. & Shorohova, E. Coupled effect of temperature and mineral additions facilitates decay of aspen bark. Geoderma 316, 27–37 (2018).

Zhao, Z. et al. Nutrient availability explains distinct soil fungal colonization of angiosperm versus gymnosperm wood. J. Ecol. 113, 232–248 (2024).

Lambert, R. L., Lang, G. E. & Reiners, W. A. Loss of mass and chemical change in decaying boles of a subalpine balsam fir forest. Ecology 61, 1460–1473 (1980).

Laiho, R. & Prescott, C. E. Decay and nutrient dynamics of coarse woody debris in northern coniferous forests: a synthesis. Can. J. Res. 34, 763–777 (2004).

Fujii, K., Uemura, M., Hayakawa, C., Funakawa, S. & Kosaki, T. Environmental control of lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, and laccase activities in forest floor layers in humid Asia. Soil Biol. Biochem. 57, 109–115 (2013).

Yue, K. et al. Dynamics of calcium, magnesium, and manganese during litter decomposition in alpine forest aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecosystems 24, 516–529 (2020).

Zuo, J. et al. Faunal community consequence of interspecific bark trait dissimilarity in early-stage decomposing logs. Funct. Ecol. 30, 1957–1966 (2016).

Wojciech, P., Ewa, B. & Jaroslaw, L. Soil biochemical properties and stabilisation of soil organic matter in relation to deadwood of different species. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 95, fiz011 (2019).

Šamonil, P. et al. Convergence, divergence or chaos? Consequences of tree trunk decay for pedogenesis and the soil microbiome in a temperate natural forest. Geoderma 376, 114499 (2020).

Sokołowski, K., Gawryś, R. & Błońska, E. The falling of a tree in the forest is the beginning of significant changes in the soil. Plant Soil 507, 383–396 (2024).

Kooch, Y., Nouraei, A. & Wirth, S. Deadwoods are hotspots for soil functions in old-growth beech forests: monitoring during 15 years after a windthrow event. Eur. J. Res. 142, 1401–1421 (2023).

Almeida, L. F. J. et al. Forest litter constraints on the pathways controlling soil organic matter formation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 163, 108447 (2021).

Kushnevskaya, H. & Shorohova, E. Presence of bark influences the succession of cryptogamic wood-inhabiting communities on conifer fallen logs. Folia GeoBot. 53, 175–190 (2018).

Gerson, U. Bryophytes and invertebrates. In Bryophyte Ecology (ed. Smith, A. J. E.). 291–332 (Springer, 1982).

Oberle, B. et al. Accurate forest projections require long-term wood decay experiments because plant trait effects change through time. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 864–875 (2020).

Shorohova, E., Kapitsa, E., Ruokolainen, A., Romashkin, I. & Kazartsev, I. Types and rates of decomposition of Larix sibirica trees and logs in a mixed European boreal old-growth forest. Ecol. Manag. 439, 173–180 (2019).

Ulyshen, M. D. Wood decomposition as influenced by invertebrates. Biol. Rev. 91, 70–85 (2016).

Erdenebileg, E. et al. Multiple abiotic and biotic drivers of long-term wood decomposition within and among species in the semi-arid inland dunes: a dual role for stem diameter. Funct. Ecol. 7, 1472–1484 (2020).

Olson, J. S. Energy storage and the balance of producers and decomposers in ecological systems. Ecology 44, 322–331 (1963).

Furey, G. N. & Tilman, D. Plant chemical traits define functional and phylogenetic axes of plant biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 26, 1394–1406 (2023).

Han, W. X., Fang, J. Y., Reich, P. B., Ian Woodward, F. & Wang, Z. H. Biogeography and variability of eleven mineral elements in plant leaves across gradients of climate, soil and plant functional type in China. Ecol. Lett. 14, 788–796 (2011).

Wijas, B. J., Cornwell, W. K., Oberle, B., Powell, J. R. & Zanne, A. E. Faster than expected: release of nitrogen and phosphorus from decomposing woody litter. N. Phytol. 245, 2214–2223 (2025).

Zhao, N. et al. Coordinated pattern of multi-element variability in leaves and roots across Chinese forest biomes. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 25, 359–367 (2016).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining,785–794 (ACM, 2016).

Mammone, A., Turchi, M. & Cristianini, N. Support vector machines. WIREs Comput. Stat. 1, 283–289 (2009).

Hempel, S., Frieler, K., Warszawski, L., Schewe, J. & Piontek, F. A trend-preserving bias correction—the ISI-MIP approach. Earth Syst. Dyn. 4, 219–236 (2013).

Xu, H., Yue, C., Zhang, Y., Liu, D. & Piao, S. Forestation at the right time with the right species can generate persistent carbon benefits in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2304988120 (2023).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Parks, S. A. & Hegewisch, K. C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958-2015. Sci. Data 5, 170191 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42501127, C.H.C) and China Scholarship Council (2021M700226, C.H.C). This research was also support by the Key Research and Development Program of Tibetan Autonomous Region of China (XZ202401ZY0095, X.D.W.) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (32425038, B.Z.). We thank Dr. Xu Hao (Peking University, P.R.China) for his help in the bias correction and downscaling for the climate data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H.C., J.H.C.C., and X.D.W. conceived the ideas and designed the methodology; J.Y.L. contributed to data collection and data analysis; C.H.C. led the writing of the manuscript; B.Z., G.G.O.D., and W.Q.Y. commented on the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ekaterina Shorohova, who co-reviewed with Joette Crosier and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, C., Liu, J., Zhu, B. et al. Climate and traits drive bark decomposition patterns at global scale. Nat Commun 17, 299 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68249-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68249-4