Abstract

The ability to perform quantum error correction (QEC) and robust gate operations on encoded qubits opens the door to demonstrations of quantum algorithms. Contemporary QEC schemes typically require mid-circuit measurements with feed-forward control, which are challenging for qubit control, often slow, and susceptible to relatively high error rates. In this work, we propose and experimentally demonstrate a universal toolbox of fault-tolerant logical operations on error-detecting codes without mid-circuit measurements on a trapped-ion quantum processor. We present modular logical state teleportation between two four-qubit error-detecting codes without measurements during algorithm execution. Moreover, we realize a fault-tolerant universal gate set on an eight-qubit error-detecting code hosting three logical qubits, based on state injection, which can be executed by coherent gate operations only. We apply this toolbox to experimentally realize Grover’s quantum search algorithm fault-tolerantly on three logical qubits encoded in eight physical qubits, with the implementation displaying clear identification of the desired solution states. Our work demonstrates the practical feasibility and provides first steps into the largely unexplored direction of measurement-free quantum computation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The practical implementation of quantum algorithms depends on their resilience to errors, alongside the ability to perform arbitrary quantum operations. Quantum error correction (QEC) enables the detection and correction of errors arising during computation by encoding information across multiple physical qubits1,2,3. Computations on these encoded qubits can be realized through a discrete, universal set of gates3. These operations have to be implemented in a robust, fault-tolerant (FT) fashion, meaning that local faults in the underlying gate operations do not proliferate uncontrollably across the logical qubits4. However, no QEC code intrinsically supports a full, inherently FT universal gate set5. Completing this FT universal gate set is a key challenge for realizing a potential advantage beyond the reach of algorithms that can be efficiently simulated classically. Recent experiments have demonstrated QEC cycles on trapped-ion quantum processors6,7,8,9,10, superconducting architectures11,12,13,14, as well as neutral-atom platforms15,16. FT universal gate sets have been realized on these platforms by means of code switching17,18, where information is transferred between two codes with complementary sets of inherently FT gates, as well as magic state injection12,19,20,21, which requires high-fidelity magic states as a resource22,23. These advancements in the practical and scalable implementations of logical qubits enabled the execution of the first, small quantum algorithms run on encoded qubits, such as the Bernstein–Vazirani algorithm24,25, one-bit addition26,27, Grover search on two logical qubits16,28 or the quantum Fourier transform on three logical qubits29.

Many practical protocols rely on measurements during algorithm execution and feed-forward operations conditioned on these measurement outcomes, which is experimentally demanding on many hardware platforms and limits their success probability: In both atomic and superconducting quantum processors, measurements remain orders of magnitude slower than typical gate times, which poses speed limitations and results in decoherence of idling qubits during measurements. Moreover, fluorescence read-out in atomic setups requires additional cooling during and after measurements, as atoms are heated during this process17,20,30,31,32.

Following early works33,34, recent theoretical works have proposed practical measurement-free protocols for logical state preparation35, rounds of QEC36,37,38 and the implementation of an FT universal gate set39,40,41. In these protocols, stabilizer information is transferred onto auxiliary qubits, allowing decoding and coherent feedback to be carried out within the quantum algorithm itself. This approach avoids the need for mid-circuit measurements or feed-forward operations entirely. At the end, auxiliary qubits are replaced or reset to be reused, effectively removing the entropy introduced by the noise.

In this work, we develop and experimentally demonstrate a complete toolbox of logical operations needed for FT universal quantum computing on an ion-trap quantum processor, without mid-circuit measurements or feed-forward operations. First, we construct protocols for modular logical quantum state teleportation, such that different encoded blocks are never directly coupled to one another, which is a key desideratum for scaling up quantum computations to large numbers of logical qubits. We analyze the performance of these measurement-free protocols for different logical input states, accompanied by numerical simulations. We then complete an FT, measurement-free universal gate set for an eight-qubit error-detecting code by constructing and implementing circuits for a logical Hadamard gate on an encoded qubit. Finally, we use this implementation as a building block for Grover’s algorithm to search for two elements out of eight, for the first time demonstrating a small-scale FT and measurement-free universal quantum algorithm.

Results

Experimental setup

The experimental data were obtained with a 16-qubit quantum computing device based on trapped ions42. The chain of 16 40Ca+ ions is confined in a linear Paul trap. The physical qubits are encoded in \(| 0\rangle=| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=-1/2 \rangle\) and \(| 1\rangle=| {3}^{2}{{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{5/2},{m}_{J}=-1/2\rangle\) Zeeman sub-levels. The state of each qubit can be manipulated individually by optically addressing the ions with 729 nm laser light. Two-qubit gates are realized as a Mølmer–Sørensen (MS) interaction43, providing all-to-all two-qubit-gate connectivity. Overall, the native gate set of the device includes arbitrary-angle rotation gates \(R(\theta,\phi )=\exp (-i\frac{\theta }{2}[X\cos \phi+Y\sin \phi ])\), ‘virtual’ Z-gates \({R}_{Z}(\theta )=\exp (-i\frac{\theta }{2}Z)\), and maximally-entangling two-qubit gates \(XX(\pi /2)=\exp (-i\frac{\pi }{4}X\otimes X)\). A description of the experimental setup can be found in refs. 21,42,44.

Our trapped-ion platform is capable of performing mid-circuit measurement operations, as was shown in ref. 7. However, such an operation, together with an additional feed-forward, represents a substantial experimental overhead in both sequence duration and infidelity. In our protocols, we do not need to perform these operations, but require only resets of the quantum state of certain qubits. The reset is faster than our current implementation of the mid-circuit measurement (1.7 ms vs. ≈30 ms), and the preservation of the data qubit’s state is higher, which is discussed further in the ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Qubit reset’. Instead of re-initializing physical qubits, one can also replace them with fresh physical qubits. In our experiments, we make use of the full 16-ion register and use fresh physical qubits whenever possible.

Logical state teleportation without mid-circuit measurements

In this section, we discuss how to teleport a logical state between two four-qubit registers without mid-circuit measurements or feed-forward operations, and demonstrate this concept experimentally. We consider a [[4, 1, 2]]-code instance that encodes k = 1 logical qubit in n = 4 physical qubits and has distance d = 2, meaning that any single error can be detected. The stabilizers and logical operators defining the code are shown in Fig. 1a.

a Stabilizers SZ, SX and logical operators of the [[4, 1, 2]]-code. b Experimental logical quantum state tomography for FT logical state initialization. The black dashed boxes correspond to ideal values in a fault-free case. Any deviation from the black dashed boxes, e.g., unboxed gray, blue or brown areas, indicates that noise reduces the overall fidelity. c High-level circuit for measurement-based modular logical teleportation. The source (S) and target (T) code blocks are merged by measuring the joint logical \({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{S}}}}}{X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\)-operator via an auxiliary register (Aux.) and applying a Z-type feedback operation based on the measurement outcome (first green box). The two blocks are then split again by measuring \({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{S}}}}}\) and applying an X-type operation to the target register conditioned on the measurement outcome (second green box). d Schematic illustration of modular state teleportation, where the source and target registers are never directly coupled to one another, but only interact via an auxiliary quantum register (Aux). e High-level circuits for measurement-free logical teleportation and experimental logical quantum state tomography. We replace the measurements and feed-forward operations with coherent feedback operations to teleport a state without mid-circuit measurements (blue). An additional HL is applied to the target state using the circuit shown in orange. The reset operation can either be carried out explicitly by physically resetting the auxiliary qubits and reusing them afterwards, or implemented by replacing them with fresh qubits.

A standard approach for teleporting a state between registers is based on lattice surgery45,46, which is illustrated in Fig. 1c. First, two code blocks are merged by measuring the joint logical X-operator. Based on this measurement outcome, one applies a logical Z-operation to the target register. In a second step, the two blocks are split again by measuring the logical Z-operator of the source register and applying a conditional logical X-operation to the target register. The measurement-based approach has been realized experimentally on various platforms12,20,47,48,49.

Instead of performing measurements and conditional operations based on the measurement outcomes, we now map the respective operators to an auxiliary register and apply coherent feedback operations, as illustrated in Fig. 1e in blue. In the first step, we couple both logical qubit registers to the auxiliary register by applying pairs of CNOT-gates to map the information about the joint logical operator \({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{S}}}}}{X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\) of the source (S) and the target (T) register to the auxiliary qubits. The conditional logical Z-operation can then be implemented coherently with a combination of CZ-gates that act on the auxiliary and target register, as shown in the green dashed box in Fig. 1e. In the second step, we map the logical \({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{S}}}}}\) to the auxiliary register and apply a coherent feedback with a combination of CNOT-gates. The scheme is made FT by repeating subroutines, i.e., by mapping multiple stabilizer-equivalent logical operators onto auxiliary qubits, as discussed further in the ‘Methods’ Section. The explicit circuits can be found in the ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Circuits’.

We construct a similar protocol that enables the implementation of a logical HL-gate (shown in Fig. 1e in orange) with the same resources as the bare teleportation protocol. We find this circuit by inserting a physical H-gate to the target qubit and propagating it back through the circuit, such that no H-gate has to be performed explicitly. This means that no HL-gate has to be applied to a [[4, 1, 2]] instance when shifting this circuit to the logical level.

We experimentally perform logical state tomography for three protocols: state initialization, logical state teleportation and the application of a logical HL-gate for logical input states \({| 0\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) and \({|+\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), which is shown in Fig. 1b, e. Further details on the measurement bases and number of shots can be found in the ‘Methods’ Section. We achieve fidelities of up to 93(2)% for state teleportation and 95(3)% for an HL-gate, which is lower than the respective physical gate operation with a fidelity of ≈0.996. The difference in fidelities for the two logical input states can be traced back to two sources. First, dephasing on idling qubits due to fluctuations in the magnetic fields introduces a strong bias towards Z-type errors. Furthermore, we measure the qubits in the Z-basis in the end and determine the logical value from this measurement, if the target state is a \({| 0\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\)-state. Based on these outcomes, we perform a classical round of error detection and postselect on the two Z-stabilizers of the [[4, 1, 2]]-code. When the target state is the \({|+\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\)-state, and we determine the logical X-value, we can only postselect on one X-stabilizer. By accepting fewer runs, we effectively also discard a fraction of runs where higher-weight errors lead to a failure, and fidelities increase the more we postselect.

Our FT logical state teleportation scheme can, in principle, be scaled to higher-distance surface codes, which is discussed further in the ‘Methods’ Section. Here, the key idea is to use d representations of logical operators on a distance-d code to ensure that no weight-d fault leads to a logical failure.

FT toolbox for universal operations on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code

In this section, we discuss circuit constructions for a FT universal gate set on an eight-qubit error-detecting code, which we use to implement Grover’s search algorithm on three logical qubits experimentally in the following section. The [[8, 3, 2]]-code is the smallest instance of a three-dimensional color code26,27,50,51,52 that encodes k = 3 logical qubit in n = 8 physical qubits and has distance d = 2, meaning that any single error can be detected. The X-stabilizer and a Z-stabilizer of this code have support on all eight qubits, while three additional weight-4 Z-stabilizers are defined on three faces of a cube, intersecting on edges, as shown in Fig. 2a. The three logical Pauli X-operators of this code have support on the weight-4 faces of the cube, while the logical Z-operators are defined on edges of weight 2.

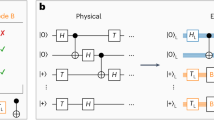

a Definition of stabilizers and logical operators on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code26,27,52. b The upper left circuit implements measurement-based H-gate injection, where an auxiliary qubit is prepared in \(|+\rangle\) and entangled with the data qubit in state \(| \psi \rangle\). In this protocol, one would measure the auxiliary qubit and apply a Pauli operation that depends on the measurement outcome m. The measurement and conditional operation (green dashed box) can be replaced with a combination of CNOT-gates (lower left), such that no mid-circuit measurements or feed-forward operations are required. We shift this scheme to the logical level by replacing the data qubit with one logical qubit of the [[8, 3, 2]]-code and the auxiliary qubit with one logical qubit of a [[4, 2, 2]]-code, which supports a natively transversal HL-gate, up to a simple relabeling.

The [[8, 3, 2]]-code supports a transversal non-Clifford gate26,27,52: the CCZ-gate can be implemented by applying single-qubit T- and T†-gates to individual qubits as illustrated in Fig. 3a, such that errors do not propagate within one code block. A logical CNOT-gate between qubits that are encoded within the same encoded block can be implemented by swapping pairs of qubits. In the following, we implement these CNOT-gates within one block by relabeling pairs of qubits, which does not require any physical gate operations. The [[8, 3, 2]]-code has in the past been used for multiple experimental demonstrations15,26,27. Recent theoretical works have proposed constructions for measurement-free, FT universal quantum computing39,40, but require a substantial overhead in gate operations and qubit count. Here, we introduce an implementation of a HL-gate for the [[8, 3, 2]]-code that does not rely on mid-circuit measurements or feed-forward operations, and, together with the CCZ-gate, completes a FT universal gate set. Our construction for the FT single-qubit logical HL-gate is based on state injection53. State injection makes use of a suitable resource state54, which is injected onto the data qubit by, first, entangling the two qubits, then measuring the resource qubit and, finally, applying a Clifford operation to the data qubit conditioned on the measurement outcome in the second step. Figure 2b1 shows the circuit that may be used to apply an HL-gate to a state \({| \psi \rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) by means of state injection. Here, an auxiliary qubit is prepared in \(|+\rangle\) as a resource state, then entangled with the data qubit with a combination of a CNOT- and a CZ-gate. Finally, the auxiliary qubit is measured in the X-basis, and either a Pauli X- or Z-flip is applied to the data qubit, depending on the measurement outcome m.

a We recompile the Grover search algorithm that includes a phase oracle55,62 into the available FT gate operations within one [[8, 3, 2]]-code {HL, CNOTL, CCZL}. b Experimentally obtained (dark) and numerically simulated (light) probabilities for each possible solution. The two solutions 011 and 101 can be clearly distinguished, and the total probability to find one of the two solutions (green) is psuccess = p011 + p101 = 0.40(4).

We now replace the measurement of the auxiliary qubit with a coherent feedback operation comprising two CNOT-gates, as shown in Fig. 2b2. A measurement can always be replaced with a quantum circuit3,34, but does not automatically obey fault-tolerant circuit design principles. In our circuit construction, we have to apply H-gates to the auxiliary qubit in order to achieve the desired H-gate injection to the data qubit. If both qubits corresponded to logical qubits of the same code, there would be no benefit in using this approach, because it would require an HL-gate in order to inject one. We therefore use different types of codes to inject the desired gate operation. Specifically, we consider the three encoded qubits of the [[8, 3, 2]]-code and inject an HL-gate onto one of the logical qubits by means of an auxiliary [[4, 2, 2]]-code prepared in \({|+0\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) as a resource state. In this circuit, we require a CNOT-gate that acts on two logical qubits that are encoded in two different code blocks. This gate can be implemented with a non-transversal, yet FT, gate implementation, implying that any single fault that may propagate through the full circuit remains detectable afterwards. This logical inter-block CNOT-gadget and the full circuit for the injection of an HL-gate are depicted in Suppl. Fig. 4. Our implementation of the FT logical HL-gate requires 4 auxiliary qubits and 26 two-qubit gates.

We perform experimental logical state tomography for each logical qubit, considering FT logical state initialization, the single-logical HL-gate and the transversal CCZL-gate on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code. We achieve fidelities of up to 81(3)% for HL on logical qubit 0, accepting 10% of the runs after postselection. Moreover, we find fidelties between 65(6)% and 99.89(14)% for the two idling logical qubits, depending on the logical input state and its sensitivity to dephasing. All results are shown and further analyzed in the ‘Methods’ Section. Notably, we identify dephasing of idling qubits as a major error source, which we estimate to account for almost two-thirds of the overall logical error rate, as discussed further in ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Error budget’.

The presented FT universal gate set on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code unlocks the capability to run minimal logical algorithms without relying on explicit mid-circuit measurement or feed-forward operations. In the next step, we use it to implement an FT Grover search on three logical qubits encoded in the [[8, 3, 2]]-code.

Grover search on logical qubits

Grover’s search algorithm55,56 enables quantum computers to search through unsorted databases significantly more efficiently than classical methods. It achieves a quadratic speedup by reducing the number of queries required to find a desired item, and can be used as a subroutine for other quantum algorithms57,58,59,60. Grover’s algorithm consists of three steps3,61:

-

1.

Initialization: Prepare all qubits in an equal-weight superposition of the computational basis states with the Hadamard transform, i.e., apply single-qubit H-gates to all qubits.

-

2.

Grover iteration: Perform (a) and (b) j times to amplify the amplitude of the solution-states s:

-

(a)

Apply an oracle operator O that marks the solutions by flipping the sign of these states.

-

(b)

Apply a diffusion operator D that reflects the state about the initial state.

-

(a)

-

3.

Measurement: Measure the qubit register in the computational basis.

We implement Grover’s algorithm on three logical qubits, thus searching a database of size N = 2n = 8 bits. As an example, we consider the phase oracle that marks s = 2 solution-states \(| 011\rangle\) and \(| 101\rangle\). In this setting, the probability of finding a solution after one Grover iteration in a noise-free setting is 1, which is discussed further in ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Grover’s search algorithm’. The optimal classical search corresponds to performing a single query, followed by a random guess, and the probability to find a solution in this case is s/N + (N − s)/N ⋅ s/(N − 1) ≈ 0.46 in our case. Grover’s search algorithm has been implemented on physical qubits on trapped ions62,63, superconducting architectures64,65,66, on spin qubits in silicon67, and on molecules using NMR techniques68. It has also been realized on two logical qubits encoded in a [[4, 2, 2]]-code with better-than-physical logical Clifford operations16,28, searching a database of N = 4. This algorithm with N = 4 does not require a universal set of gates, but can be realized with Clifford-gate operation only.

We implement the three-qubit Grover’s algorithm on logical qubits encoded in the [[8, 3, 2]]-code by utilizing the universal FT gate set {HL, CNOTL, CCZL}. We recompile the initial circuit3,55,62 into the available FT gates introduced in the previous section, as shown in Fig. 3a. We then implement this circuit on our experimental trapped-ion quantum processor, accompanied by numerical simulations according to a multi-parameter noise model specified in the ‘Methods’ Section. Figure 3b shows the determined probabilities for each of the eight possible final states, two of which correspond to the correct solution states as marked in green. The total probability to find a solution using the experimental data is psuccess = p011 + p101 = 0.40(4). This overall probability to find a solution in a single shot is slightly lower than the optimal classical probability of 0.46, as determined above. However, as discussed further in the ‘Methods’ Section, only slight enhancements to the current setup are sufficient to outperform the optimal classical algorithm. Numerical simulations show that reducing, e.g., the two-qubit-gate error rate by 1% to p2 ≈ 0.015, which has been demonstrated on experimental trapped-ion platforms31,69,70, leads to an overall success rate of ≈ 0.52, which clearly outperforms the optimal classical strategy. Instead of reducing p2, also extending the coherence time to T2 = 100 ms, which has been shown in independent technical demonstrations71,72,73,74,75, leads to a success probability of psuccess ≈ 0.67. This demonstrates that for only slightly smaller error rates on idling qubits and two-qubit gate operations, a regime where the measurement-free quantum algorithm outperforms its classical counterpart is reachable today.

Our scheme for Grover’s algorithm can be scaled to a larger search space, provided enough qubits and sufficiently reliable gate operations are available. One can implement the FT gate set {HL, CNOTL, CCZL} on logical qubits encoded within one [[8, 3, 2]] block. In addition, one can apply an inter-block CNOT-gate between two logical qubits of two distinct [[8, 3, 2]]-codes76. These operations enable the implementation of an oracle and the amplification on more than three qubits by decomposing the required gates into the available gate sets3.

Discussion

In this work, we introduce and experimentally implement a complete toolbox of operations for fault-tolerant (FT) universal quantum computing without mid-circuit measurements. Our work presents the first experimental realization of a FT universal gate set that operates without mid-circuit measurements and marks the FT implementation of Grover’s algorithm on a search space of up to N = 8 on encoded logical qubits, demonstrating for the first time a FT logical algorithm without mid-circuit measurements.

Our schemes are tailored toward trapped-ion architectures that provide all-to-all connectivity9,31,75,77, but they can be analogously implemented on other architectures. For example, neutral atom platforms have demonstrated the capabilities required for implementing the presented code constructions15,78. These architectures offer long-range connectivity and high-fidelity single- and two-qubit gates, while mid-circuit measurements and real-time feedback are still experimentally demanding due to relatively long measurement times15,78,79,80. These features make our measurement-free implementations ideal candidates for neutral atom platforms, potentially enhancing performance by avoiding costly circuit components, provided that mid-circuit measurements are no noisier than a two-qubit gate. Future developments may depend on improvements in the measurement fidelities.

Future work will include the analysis of our protocols for higher-distance codes, as outlined above, and the investigation of thresholds and required overheads in terms of qubit count and gate operations, including extensions to fault-tolerant realizations under restricted qubit-connectivity81. Moreover, we have identified dephasing on idling qubits during two-qubit gates as a major logical error source in our experimental demonstration. Further adjustment of our schemes to a biased noise setting41,82, which is often given in experimental architectures15,17,79, could therefore potentially boost the performance while reducing overheads.

Our work presents the first demonstration of measurement-free fault-tolerant quantum computation and lays the ground for further exploring the full potential of this new paradigm of fault-tolerant quantum information processing without mid-circuit measurements.

Methods

Qubit reset

The qubit reset procedure allows for a selective reinitialization of some of the qubits to state \(| 0\rangle\). Physically, the reset is performed by quenching the lifetime of the 32D5/2 manifold by illuminating the ion chain with the 854 nm laser with subsequent optical pumping to reinitialize the qubits in the \(| 0\rangle\) state. The data qubits are hidden in the 42S1/2 manifold \(| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=-1/2\rangle,| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=+ 1/2\rangle\) by means of the electron shelving technique83 during the lifetime quenching to preserve their state. This re-encoding of the data qubits in the \(| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=-1/2\rangle,| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=+ 1/2\rangle\) levels instead of the \(| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=-1/2\rangle,| {3}^{2}{{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{5/2},{m}_{J}=-1/2\rangle\) levels results in a higher sensitivity to magnetic field noise and, consequently, lower coherence time. Therefore, we perform two dynamical decoupling pulses (DD) with the radio-frequency (RF) antenna driving the transition between the \(| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=-1/2\rangle\) and \(| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=+ 1/2\rangle\) levels. The sketch of the procedure is shown in Fig. 4a, while additional details can be found in ref. 7. The reset procedure does not require recooling of the ion chain, unlike the full mid-circuit measurement, since the reset ions emit only a few photons during the procedure. Consequently, the reset is faster than our current implementation of the mid-circuit measurement (1.7 ms vs. ≈ 30 ms) and the preservation of the data qubit’s state is higher (process fidelity 0.955(9) vs. 0.908(12)). The χ-matrix for the reset procedure obtained via quantum process tomography is depicted in Fig. 4b. The main fidelity limitation for both processes at the moment is the coherence of the ground state qubit (\(| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=-1/2\rangle\) and \(| {4}^{2}{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{1/2},{m}_{J}=+ 1/2\rangle\)) of 5.3(6) ms. The recent hardware modifications, reducing the magnetic field noise, allowed us to extend this coherence time to 113(17) ms, which should significantly improve the fidelity of mid-circuit operations. Moreover, other trapped-ion setups have demonstrated even higher coherence times of the order of seconds, e.g. 84. The fidelities can be further boosted by improving the hiding pulses fidelities by the use of composite pulses85. The results will be presented in future works.

a The pulse sequence implementing the qubit reset procedure. Firstly, the data qubits are hidden in the 42S1/2 manifold by applying a global RF pulse and individually addressing each data qubit with a π-pulse. After that, the auxiliary qubits are reinitialized to \(| 0\rangle\). Finally, the data qubits' encoding is restored to the original. The dynamical decoupling (DD) pulses are inserted to mitigate decoherence of the data qubits in the 42S1/2 manifold. b The χ-matrix representation of the reset procedure as the process acting on data qubits, averaged over all data qubits. The area and the color coding of the squares correspond to the absolute value and the phase of an element of the χ-matrix, respectively. The dashed square represents an ideal outcome, specifically the identity process.

We make use of the full 16-ion register and use fresh auxiliary qubits as long as possible. The reset procedure is only used in our implementation of Grover’s algorithm (see Fig. 3) to reset one auxiliary qubit that is used for the FT preparation of \({|+00\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) for the [[8, 3, 2]]-code (see Suppl. Fig. 3e). This auxiliary qubit is later used for the mapping of one Z-stabilizer of the [[8, 3, 2]]-code, as discussed in ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Tomography’.

Anticipated performance of measurement-free state teleportation

The measurement-free logical teleportation schemes are made FT as illustrated in Fig. 5a. First, we prepare auxiliary two-qubit GHZ-states \(| {\psi }_{{{{\rm{aux}}}}}\rangle=(| 00\rangle+| 11\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) stabilized by \({S}_{X}^{{{{\rm{aux}}}}}={X}_{8}{X}_{9}\) and \({S}_{Z}^{{{{\rm{aux}}}}}={Z}_{8}{Z}_{9}\), which ensures that no single fault on an auxiliary qubit propagates to a logical error when the two registers are coupled. In addition, we map two representations of the joint logical operator \({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{S}}}}}{X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\), that have fully disjoint support, onto the auxiliary register such that no single fault on a data qubit leads to a logical error on the output state (panels 1 and 2 in Fig. 5a). Here, the information about each representation of the joint logical operator is stored in one physical auxiliary qubit, which then acts as a control qubit in the coherent feedback operation consisting of CZ-gates. The same strategy is used in step 3, where two representations of \({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{S}}}}}\) with disjoint support are mapped onto two physical qubits. The explicit circuits can be found in the ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Circuits’. The non-FT (nFT) counterparts of these protocols make use of a bare physical auxiliary qubit and only map a single representation of the respective operators onto this auxiliary qubit, which is then used to control the coherent feedback operation.

a We prepare an auxiliary two-qubit GHZ-state to prevent single faults on auxiliary qubits from causing a logical failure. In addition, we map two stabilizer-equivalent representations of the joint logical operator with fully disjoint qubit support onto the auxiliary registers (1, 2). The same strategy is used in step 3, where two equivalent but fully disjoint logical Z-operators of the source register are mapped onto two physical qubits. b Numerically determined scaling of the logical infidelity for FT and non-FT logical teleportation and the HL-gate, averaged over initial states \({| 0\rangle }_{{\mathrm{L}}}\) and \({|+\rangle }_{{\mathrm{L}}}\). We fix the error parameters \(\vec{p}=({p}_{{{{\rm{1}}}}},{p}_{{{{\rm{2}}}}},{p}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}},{p}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}},{p}_{{{{\rm{idle}}}}})\) to experimental error rates7,17 and scale these with a common improvement factor λ. We identify a quadratic scaling of the infidelity for the FT protocols with λ, which indicates—as expected—that no single fault leads to a logical failure. The FT teleportation protocol outperforms its non-FT counterpart already for the current experimental noise parameters (λ = 1). The inset shows the logical infidelities at λ = 1 obtained from the experiment (darker color) and numerical simulations (lighter color). c Scaling measurement-free state teleportation to surface codes with higher distances d > 2. Each string of qubits connecting opposing boundaries supports a representation of a logical \({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{S}}}}}\) (upper lattice) and \({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\) (lower lattice); one exemplary representation is shown in red. There are d equivalent representations that have fully disjoint support. Each one can be mapped onto an auxiliary d-qubit GHZ-state, and coherent feedback steps can be applied, which are controlled by the state on d physical auxiliary qubits.

In Fig. 5b, we simulate the scaling of the logical infidelity for FT and non-FT measurement-free logical state teleportation and the application of the HL-gate operation by means of teleportation. Here, we consider a multi-parameter noise model, attributing different error rates to each type of component in the circuits. Specifically, we consider depolarizing noise on single-qubit gates with a probability p1 = 3.6 × 10−3, two-qubit depolarizing noise on two-qubit gates with a probability p2 = 2.5 × 10−2, flipped physical qubit initializations with a probability pi = 3 × 10−3, and flips before the final projective measurements with a probability pm = 3 × 10−3. The values of the error rates correspond to the ones in our experimental setup7,17,21,42. We implement dephasing on all idling qubits, where a Z-fault is applied to each idling physical qubit with a probability \({p}_{{{{\rm{idle}}}}}=(1-{e}^{-{t}_{{{{\rm{gate}}}}}/{T}_{2}})\) given the gate time of the respective operation and the coherence time T2 = 50 ms. Note that gates in the experimental setup can only be executed sequentially, which increases the total dephasing time. The noise channels and numerical methods are explicitly given in ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Numerical methods’. We scale the error parameters \(\vec{p}(\lambda )=\lambda \cdot ({p}_{1},{p}_{2},{p}_{i},{p}_{m},{p}_{{{{\rm{idle}}}}})\) with a common factor λ, such that λ = 1 corresponds to the set of parameters as given in the current experimental setup. As expected, the FT protocols scale quadratically with λ, indicating that the required fault-tolerance properties are fulfilled.

Our approach for logical state teleportation without mid-circuit measurements is, in principle, straightforwardly scalable to higher distance d > 2 surface codes, as illustrated in Fig. 5c. These codes have d equivalent representations of the logical Pauli operators which do not share support. For the FT mapping of the weight-d logical operators, we then have to prepare the auxiliary register fault-tolerantly in a d-qubit GHZ-state, and apply coherent feedback steps controlled on the state of d physical auxiliary qubits. However, this approach requires the FT preparation of potentially high-weight GHZ-states. An alternative route to scalability could entail concatenating the presented schemes to avoid the need for high-weight physical GHZ-states. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the averaged simulated logical error rates for the [[4, 1, 2]]-code. For simplicity, here we implement a single-parameter noise model where each two-qubit gate introduces an error with probability p. Additionally, we count the lowest-weight fault-locations that lead to a logical failure in the [[4, 1, 2]]-code. Specifically, 1792 weight-two fault-locations lead to a failure for the initial state \({|+\rangle }_{L}\) and 2784 fault-locations for the initial state \({| 0\rangle }_{L}\). Note that for each two-qubit gate, we consider 15 possible locations corresponding to the 15 distinct two-qubit Pauli errors. These counts provide an estimate of the logical failure rate, which scales as pL ≈ c × p2. Given this polynomial, we can infer the failure rates for higher levels of concatenation because \({p}_{L}^{(n)}={c}^{{2}^{n}-1}\cdot {p}^{{2}^{n}}\), i.e., \({p}_{L}^{(1)}=c\cdot {p}^{2}\), \({p}_{L}^{(2)}=c\cdot {p}_{L}^{(1)2}={c}^{3}{p}^{4}\) and so on. As shown in Fig. 2, the calculated polynomials (dashed lines) for the first two concatenation levels agree with the numerically simulated ones (solid curves). These results demonstrate that our approach for measurement-free logical state teleportation can be scaled to higher distances without the need for large GHZ-states. However, within the error-detecting framework, we always have to discard a fraction of runs, and this fraction increases with more layers of concatenation, as can be seen in Suppl. Fig. 1b, because more and higher-weight errors can be detected. Another approach to achieving scalability is to rely on different auxiliary states that still maintain fault tolerance in the presented protocols. Preliminary results indicate that MF FT operation of distance-3 surface code by means of carefully crafted quantum circuits without the need of FT prepared GHZ ancillary states is also viable, but a detailed analysis and generalization to higher code distances is left for future follow-up work.

Numerical methods

We use Monte-Carlo simulations to estimate the logical infidelities of our protocols86. Each circuit component is modeled by first applying the respective ideal operation, followed by an error E occurring with probability p. We simulate a depolarizing noise channel after every single- and two-qubit gate. With probabilities p1 and p2, an error from the respective sets is applied. These probabilities define the corresponding error channels

with \({E}_{1}^{k}\in \{X,Y,Z\}\) for k = 1, 2, 3 and \({E}_{2}^{k}\in \{IX,XI,XX,IY,YI,YY,IZ,ZI,ZZ,XY,YX,XZ,ZX,YZ,ZY\}\) for k = 1, …, 15. All qubits are initialized and measured in the Z-basis, at the very end of the respective protocols. To simulate faults in these operations, we apply X-flips after initialization and before measurement, each occurring with probabilities pinit and pmeas, respectively. Moreover, qubits that remain idle during gate operations may experience dephasing, which we model with the error channel

The probability pidle depends on the execution time t of the performed gate and the qubit coherence time T2 = 50 ms

In our simulations, we use t1 = 70 μs as the gate time of single-qubit gates and t2 = 350 μs as the gate time of two-qubit gates, as summarized in Suppl. Tab. 1.

We measure the final state in the logical X-, Y-, and Z-basis for each protocol, as described in ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Tomography’, and calculate the state fidelity between the ideal logical state ρ1 and the reconstructed density operator ρ2 obtained after postselecting, as

We use Qiskit’s Quantum Information package to calculate fidelities87.

Circuits

Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the explicit circuits that were implemented for FT logical state teleportation discussed in Section ‘Logical state teleportation without mid-circuit measurement’. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows the circuit constructions for the FT logical state initializations on the [[4, 1, 2]]- and the [[8, 3, 2]]-code without mid-circuit measurements as implemented in the demonstrated protocols. In these circuits, fault tolerance is maintained even without measurements by means of a flag-qubit-controlled reduction of potentially dangerous weight-2 errors to weight-1 configurations. Supplementary Fig. 4 depicts the circuit construction for the application of a single-logical HL-gate on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code.

Tomography

[[4, 1, 2]]-code

We perform logical state tomography for two logical input states \({| 0\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) and \({|+\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) considering logical state preparation, state teleportation and the application of a HL-gate on the [[4, 1, 2]]-code, as shown in Fig. 1. To this end, we measure in the X-, Y-, and Z-basis to extract the respective logical expectation values. For measurements in the X-basis, we measure all physical qubits in the X-basis in the end and infer the logical X-operator and the X-type stabilizer from this measurement. Analogously, we can extract the logical Z-operator and the Z-type stabilizers for measurements of all physical qubits in the Z-basis. However, we cannot simply determine the required stabilizers and the logical value at the same time for measurements in the Y-basis, because they share support but are of different Pauli-type, as for example YL = Y0X1Z2 and the Y-type stabilizer SY = Y0Y1Y2Y3. We therefore map out the Y-stabilizer onto a physical auxiliary qubit with the circuit shown in Suppl. Fig. 6. Here, the gate ordering ensures that no hook error, i.e., a fault on an auxiliary qubit that may propagate onto multiple data qubits, leads to a logical flip in the subsequent measurement, as any single propagated fault is still detected in the end by a Z-stabilizer. We finally measure the 4 qubits in the Y-, X-, and Z-basis, allowing us to determine YL and one additional Z-stabilizer \({S}_{Z}^{2}={Z}_{2}{Z}_{3}\).

[[8, 3, 2]]-code

We perform logical state tomography for each state prepared with the specified protocol, i.e., logical state preparation and the logical operations HL and CCZL on [[8, 3, 2]] for different input states, as shown in Fig. 6. We consider each individual logical qubit and perform tomography for each one independently. For measurements in the X-basis, we measure all physical qubits in the X-basis and determine the three logical Pauli-operators \({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{0}\), \({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{1}\), \({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{2}\) and the X-stabilizer SX, as defined in Fig. 2a. Analogously, we extract the logical Z-operators simultaneously, along with the Z-stabilizers, when measuring all physical qubits in the Z-basis. In this case, we additionally map out the X-stabilizer SX onto an auxiliary qubit when performing the HL-gate to achieve fault tolerance. The circuit that is used for measurements in the Z-basis is shown in Suppl. Fig. 5a. In this circuit, a single fault may propagate as illustrated in red, but is detected by the Z-stabilizers afterwards.

For measurements in the Y-basis, we have to take into account that the different logical operators may share support but are of different Pauli-type, as for example \({Y}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{0}={Y}_{0}{X}_{1}{Z}_{2}{X}_{4}{X}_{5}\) and \({Y}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{1}={Y}_{0}{X}_{1}{X}_{2}{X}_{3}{Z}_{4}\), so they cannot be extracted simultaneously in a single measurement. We therefore perform three sets of independent experiments and determine \({Y}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{0}\), \({Y}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{1}\), and \({Y}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{2}\) individually. For measurements in the Y-basis, we also map the Y-stabilizer SY = Y0Y1Y2Y4Y3Y5Y6Y7 onto an auxiliary qubit when performing the HL-gate. We then measure the physical qubits in different bases to extract the respective logical Y-operator and one additional Z-stabilizer. An exemplary circuit that is used for measurement in the Y-basis for the extraction of \({Y}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{0}\) is shown in Suppl. Fig. 5b. When extracting \({Y}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{1}\) and \({Y}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{2}\), we measure the physical qubits in the bases Y0X1X2X3Z4Z5Z6Z7 and Y0Z1X2Z3X4Z5X6Z7, respectively.

Moreover, the logical auxiliary qubit is still intact after performing the single-logical HL-gate. We also projectively measure the logical auxiliary qubit, extract the stabilizers of the [[4, 2, 2]]-instance, and postselect for a trivial syndrome to increase the fidelities in our protocols. Here, we map the Z-stabilizer of the logical auxiliary qubit onto another physical auxiliary with the circuit shown in Suppl. Fig. 5c.

When we run the full logical Grover search algorithm on the three qubits of the [[8, 3, 2]]-code, we additionally map two Z-stabilizers \({S}_{Z}^{1}={Z}_{0}{Z}_{1}{Z}_{2}{Z}_{3}\) and \({S}_{Z}^{2}{S}_{Z}^{3}={Z}_{1}{Z}_{2}{Z}_{5}{Z}_{6}\) onto physical auxiliary qubits in the end in order to maintain fault tolerance.

Number of measurements

In the tomography experiments described in ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Tomography’, each logical state was measured in three measurement bases {X, Y, Z} with the same number of measurements for each basis. The teleportation experiment with the [[4, 1, 2]]-code (see Fig. 1) took 40000 shots for each logical state per measurement basis. The initialization and logical operations with the [[8, 3, 2]]-code (see Fig. 6) took 7500 shots for each logical state and logical qubit per measurement basis. The Grover’s algorithm demonstration (see Fig. 3) took 37,500 shots per measurement basis. All data sets were split into 12 equal subsets; the tomography was performed for every subset, yielding 12 values for the fidelity for every experiment. The final fidelity numbers are the mean and the standard deviation of these 12 values.

Performance of the FT universal gate set on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code

Figure 6 shows the logical state fidelities that were obtained experimentally for FT logical state initialization, the single-logical HL-gate and the transversal CCZL-gate on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code. We find that fidelities are higher if the final target state is a Z-eigenstate, as opposed to an X-eigenstate, due to dephasing, which does not affect the fidelity for Z-eigenstates. Additionally, postselection based on the four Z-stabilizers is more selective than only a single X-stabilizer, which boosts the fidelities in these cases. The degree of postselection is reflected in the acceptance rates: the average acceptance rates in the experiment[simulation] after the state initialization are 0.6[0.64] in the X-basis, 0.48[0.53] in the Y-basis, and 0.3[0.48] for measurements in the Z-basis; the numbers in brackets indicate the acceptance rate obtained in the simulation. After the injection of an HL-gate, these are 0.3[0.2] for measurements in the X-basis, 0.2[0.13] in the Y-basis and 0.1[0.07] in the Z-basis. The fidelities for the state initialization of \({|+00\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) and CC\({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}{|+00\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) agree with each other within the given uncertainty interval, since the CCZL consists entirely of virtual Z-rotations, thus no additional operations are physically applied to the qubits.

Figure 7 shows the simulated scaling of the logical infidelity for the logical HL-gate on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code for each logical qubit. We scale the noise parameters \(\vec{p}(\lambda )=\lambda \cdot ({p}_{1},{p}_{2},{p}_{i},{p}_{m},{p}_{{{{\rm{idle}}}}})\) given the same values as specified above, such that λ = 1 corresponds to the set of parameters as given for the current experimental setup. The inset shows the state fidelities for the different logical input states obtained from experiment and simulation.

We fix the error parameters \(\vec{p}=({p}_{{{{\rm{1}}}}},{p}_{{{{\rm{2}}}}},{p}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}},{p}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}},{p}_{{{{\rm{idle}}}}})\) and scale these with λ. λ = 1 corresponds to the current values in the experimental setup. We determine numerically the scaling of the logical infidelity for the logical qubit 0 (a), on which the HL is applied, and idling logical qubits 1 (b) and 2 (c). The inset shows the logical infidelities at λ = 1 obtained from the experiment (darker color) and from numerical simulations (lighter color). We find that experimentally and numerically obtained state fidelities agree within their uncertainty intervals for qubits 1 and 2, while these values differ on qubit 0 for certain states, as discussed further in ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Performance of the FT universal gate set on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code’.

We find that the numerically and experimentally obtained fidelities agree for the two idling logical qubits, while the fidelities of the first logical qubit obtained from simulation, shown in blue in Fig. 7a, differ from the experimental result by more than 14% for logical states \({|+00\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) and \({| 000\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\). We attribute this deviation to global dephasing effects due to random fluctuations in the effective magnetic field that act on all physical qubits simultaneously88, instead of locally and uncorrelated on each individual qubit. The effect of this global dephasing on the eight-qubit state can be estimated by considering the explicit basis states, for example,

Local dephasing on this state leads to decay of the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix with a factor of e−Δn/2⋅γt, where γ is a decay constant, and t is time. Δn is the number of positions in the basis states, where the entries of two basis states differ, and corresponds to the Hamming distance. For \({| 000\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), Δn = 8 and the decay factor is given by e−4γt. Global dephasing, on the other hand, will cause the off-diagonal elements to decay with a factor of \({e}^{-{(\Delta m/2)}^{2}/2\cdot \gamma t}\)88. Δm is the difference in magnetization of the basis states, where the magnetization of a state is given by the difference between the number of qubits in the ground state \(| 0\rangle\) and the remaining number of bits in the excited state \(| 1\rangle\)88.

For \({| 000\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), Δm = 16 and, thus, this prefactor is given by e−32γt. This means that, for \({| 000\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), the off-diagonal elements decay eight times faster for global dephasing than for local. \({| 000\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) is most sensitive to this global effect, since it is an eight-qubit GHZ-state with maximal difference in the magnetization between its basis states. This effect is expected and found to be less pronounced for \({|+00\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=\frac{1}{2}(| 00000000\rangle+| 11111111\rangle+| 11001100\rangle+| 00110011\rangle )\), where only some coherences decay according to Δm = 8 and some with Δm = 4, so twice and eight times faster than for local dephasing. We only account for local dephasing in our simulations, as characterized in ‘Methods’ Subsection ‘Numerical methods’, which may partly explain the observed differences between the numerically determined and the experimental fidelities. The deviation between experiment and simulation is less pronounced for the two idling logical qubits, because, considering the states that are most sensitive to this global dephasing effect, i.e., \({| 000\rangle }_{L}\) and \({|+00\rangle }_{L}\), these qubits stay in the \(| 0\rangle\)-state throughout the whole protocol and are therefore not affected by Z-type errors.

Error budget

Logical errors can be correlated in quantum codes that encode multiple logical qubits, such as block codes89 or quantum low-density parity-check codes90,91. We investigate these correlated errors by determining the probabilities for each logical error configuration, including single and correlated errors, for the non-transversal single-logical HL-gate on the [[8, 3, 2]]-code. To this end, we prepare logical state \({|+00\rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\)(\({| 0++ \rangle }_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\)), then apply the HL-gate to the first qubit and measure destructively in the Z(X)-basis. From this, we infer if one, two or all three logical qubits have been flipped, which corresponds to the probability of logical X(Z)-errors. Figure 8a, b shows the probabilities for logical X- and Z-error configurations on the experimental setup. Notably, logical errors do not occur independently as \(p({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{i}{X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{j})\ne p({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{i})p({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{j})\) and \(p({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{i}{Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{j})\ne p({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{i})p({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{j})\), as theoretically predicted in previous works on quantum LDPC codes92. Figure 8c, d shows numerical data for a setting without dephasing on idling qubits and for perfectly initialized logical states, to isolate the contribution of the HL-gate protocol. Logical error probabilities decrease substantially, while the overall distribution is maintained. Notably, we find that dephasing attributes for a large part of the overall logical error rate: without dephasing, the logical Z-error rate on qubit 0 drops from almost 0.3 (left-most light blue column in Fig. 8b) to less than 0.1 (left-most orange column in Fig. 8d).

a, b Simulated and experimentally obtained probabilities for logical X- and Z-error configurations. The numbers on top of the bars correspond to the ratio between \(p({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{i}{X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{j})\) and \(p({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{i})p({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{j})\), and \(p({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{i}{Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{j})\) and \(p({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{i})p({Z}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{j})\). For example, the determined probability \(p({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{0}{X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{1})\) is 2 times larger than the probability one would expect from independent errors on logical qubits 0 and 1, \(p({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{0})p({X}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{1})\). c, d Probabilities for each logical X- and Z-error configuration without dephasing, and for a perfectly initialized input state. Here, the probabilities for X-error configurations are shown on a logarithmic scale for visibility.

Grover’s search algorithm

The number of required Grover iterations n providing the highest amplification of the solution-states depends on the size of the search space N (N = 23 = 8 in our case) and the number of solutions s. In this work, we use a phase oracle61,62 with two solutions (s = 2) \(w\in \{| 011\rangle,| 101\rangle \}\): states \(| 011\rangle\) and \(| 101\rangle\) are marked by the oracle of the form

The initial equal-superposition state can be represented as a superposition of solutions and non-solution states3

with \(\sqrt{s/N}=\sin \theta\), i.e., θ = π/6 in our case. The probability of obtaining a valid solution w when measuring in the computational basis is s/N = 1/4, and the probability of obtaining an orthogonal non-solution state \({\psi }^{{\prime} }\) equals (N − s)/N = 3/4. One Grover step is a product of two reflections, first about the solution states \(| w\rangle\) with the oracle O and then about the initial state \(| \psi \rangle\) with the diffusion operator D. This corresponds to an overall rotation of the initial state, and the rotation angle can be identified to be 2θ = π/3 in our case. A single application of the Grover iteration, including the oracle O and the diffusion operator D, amplifies the probability of success to 13,61, since

meaning that a solution in the fault-free case is found with certainty. Analogously, the probability of finding a solution after k Grover iterations in a noise-free setting is given by \({\sin }^{2}((2k+1)\theta )\).

A quantum circuit implementing this algorithm is shown in Fig. 3a. This original circuit can be simplified to allow for a simpler implementation with logical qubits compiled into available logical gates of the [[8, 3, 2]]-code, reducing the number of required HL-gates to one. All operations in the resulting circuit can be fault-tolerantly implemented within the [[8, 3, 2]]-code as described in Section ‘FT toolbox for universal operations on the[[8,3,2]]-code’.

Projected performance of Grover’s algorithm

We simulate Grover’s algorithm on logical qubits for different sets of noise parameters in order to estimate how much physical error rates have to improve to gain an advantage over the classically optimal success probability of 0.46. Figure 9 shows the simulated probabilities to find each possible solution state for the initial set of noise parameters (blue), for a two-qubit-gate error rate reduced by 1% and for an increased coherence time \({T}_{2}^{{\prime} }=2{T}_{2}=100\,\,{{{\rm{ms}}}}\). Both projected scenarios outperform the classical counterpart, indicating that even minor enhancements to the current setup could push performance beyond this break-even point.

We simulate Grover’s search algorithm for the set of noise parameters as characterized by the current experimental setup (blue), indicating a success probability of psuccess = 0.40(4). For a slightly lower two-qubit-gate error rate of \({p}_{2}^{{\prime} }={p}_{2}-0.01=0.015\), we already obtain a total success probability of 0.52(1), which is above the classical optimal success probability of 0.46, as discussed in Section ‘Grover search on logical qubits’. If instead of lowering p2, we increase T2 by a factor of 2–100 ms (orange), we find even higher success rates of psuccess = 0.67(1).

Grover search on physical qubits

We implement Grover’s search algorithm on physical qubits, as compiled in Fig. 3a on our experimental trapped-ion setup, accompanied by numerical simulations; the results are shown in Fig. 10. The total experimental[simulated] success probability of 76(2)%[77(1)%] is larger than for the FT implementation on logical qubits, indicating that the quantum algorithm executed on logical qubits is currently still operated above the break-even point with its counterpart realization on physical qubits.

We implement the circuit shown in Fig. 3a on physical qubits and determine the probabilities for each outcome in the experiment (darker columns) and simulation (lighter columns).

Data availability

The data provided in the figures in this article, the explicit circuits, and the code that was used to simulate the presented protocols are available at https://zenodo.org/records/17375920.

References

Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2, 79 (2018).

Gottesman, D. Stabilizer Codes and Quantum Error Correction. PhD thesis (California Institute of Technology, 1997).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th edn (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Knill, E., Laflamme, R. & Zurek, W. H. Resilient quantum computation. Science 279, 342–345 (1998).

Eastin, B. & Knill, E. Restrictions on transversal encoded quantum gate sets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 110502 (2009).

Ryan-Anderson, C. et al. Realization of real-time fault-tolerant quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041058 (2021).

Postler, L. et al. Demonstration of fault-tolerant Steane quantum error correction. PRX Quantum 5, 030326 (2024).

Huang, S., Brown, K. R. & Cetina, M. Comparing Shor and Steane error correction using the Bacon–Shor code. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp2008 (2024).

Reichardt, B. W. et al. Demonstration of quantum computation and error correction with a tesseract code. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.04628 (2024).

Nguyen, N. H. et al. Demonstration of Shor encoding on a trapped-ion quantum computer. Phys. Rev. A 16, 024057 (2021).

Google Quantum AI and Collaborators. Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. Nature 638, 920–926 (2025).

Lacroix, N. et al. Scaling and logic in the color code on a superconducting quantum processor. Nature 645, 614–619 (2025).

Krinner, S. et al. Realizing repeated quantum error correction in a distance-three surface code. Nature 605, 669–674 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Realization of an error-correcting surface code with superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 030501 (2022).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2024).

Chung, W. C. et al. Fault-tolerant operation and materials science with neutral atom logical qubits. npj Quantum Inf. 11, 95 (2025).

Pogorelov, I. et al. Experimental fault-tolerant code switching. Nat. Phys. 21, 298–303 (2025).

Daguerre, L., Blume-Kohout, R., Brown, N. C., Hayes, D. & Kim, I. H. Experimental demonstration of high-fidelity logical magic states from code switching. Phys. Rev. X 15, 041008 (2025).

Dasu, S. et al. Breaking even with magic: demonstration of a high-fidelity logical non-Clifford gate. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.14688 (2025).

Ryan-Anderson, C. et al. High-fidelity teleportation of a logical qubit using transversal gates and lattice surgery. Science 385, 1327–1331 (2024).

Postler, L. et al. Demonstration of fault-tolerant universal quantum gate operations. Nature 605, 675–680 (2022).

Sales Rodriguez, P. et al. Experimental demonstration of logical magic state distillation. Nature 645, 620–625 (2025).

Gupta, R. S. et al. Encoding a magic state with beyond break-even fidelity. Nature 625, 259–263 (2024).

Bernstein, E. & Vazirani, U. Quantum complexity theory. In Proc. 25th Annu. ACM Symp. Theory Comput. 11–20 (1993).

Reichardt, B. W. et al. Logical computation demonstrated with a neutral atom quantum processor. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.11822 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Fault-tolerant one-bit addition with the smallest interesting color code. Sci. Adv. 10, eado9024 (2024).

Honciuc Menendez, D., Ray, A. & Vasmer, M. Implementing fault-tolerant non-Clifford gates using the [[8, 3, 2]] color code. Phys. Rev. A 109, 062438 (2024).

Pokharel, B. & Lidar, D. A. Better-than-classical Grover search via quantum error detection and suppression. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 23 (2024).

Mayer, K. et al. Benchmarking logical three-qubit quantum Fourier transform encoded in the Steane code on a trapped-ion quantum computer. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.08616 (2024).

Graham, T. M. et al. Midcircuit measurements on a single-species neutral alkali atom quantum processor. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041051 (2023).

Moses, S. A. et al. A race-track trapped-ion quantum processor. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041052 (2023).

Singh, K. et al. Mid-circuit correction of correlated phase errors using an array of spectator qubits. Science 380, 1265–1269 (2023).

Paz-Silva, G. A., Brennen, G. K. & Twamley, J. Fault tolerance with noisy and slow measurements and preparation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 100501 (2010).

Gottesman, D. Surviving as a quantum computer in a classical world. Textbook manuscript preprint (2016).

Goto, H., Ho, Y. & Kanao, T. Measurement-free fault-tolerant logical-zero-state encoding of the distance-three nine-qubit surface code in a one-dimensional qubit array. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 043137 (2023).

Perlin, M. A., Premakumar, V. N., Wang, J., Saffman, M. & Joynt, R. Fault-tolerant measurement-free quantum error correction with multiqubit gates. Phys. Rev. A 108, 062426 (2023).

Heußen, S., Locher, D. F. & Müller, M. Measurement-free fault-tolerant quantum error correction in near-term devices. PRX Quantum 5, 010333 (2024).

Veroni, S., Müller, M. & Giudice, G. Optimized measurement-free and fault-tolerant quantum error correction for neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 043253 (2024).

Butt, F., Locher, D. F., Brechtelsbauer, K., Büchler, H. P. & Müller, M. Measurement-free, scalable, and fault-tolerant universal quantum computing. Sci. Adv. 11, eadv2590 (2025).

Veroni, S., Paler, A. & Giudice, G. Universal quantum computation via scalable measurement-free error correction. PRX Quantum 6, 040337 (2025).

Brechtelsbauer, K. et al. Measurement-free quantum error correction optimized for biased noise. PRX Quantum 6, 040349 (2025).

Pogorelov, I. et al. Compact ion-trap quantum computing demonstrator. PRX Quantum 2, 020343 (2021).

Sørensen, A. & Mølmer, K. Entanglement and quantum computation with ions in thermal motion. Phys. Rev. A 62, 022311 (2000).

Heußen, S. et al. Strategies for a practical advantage of fault-tolerant circuit design in noisy trapped-ion quantum computers. Phys. Rev. A 107, 042422 (2023).

Horsman, D., Fowler, A. G., Devitt, S. & Van Meter, R. Surface code quantum computing by lattice surgery. New J. Phys. 14, 123011 (2012).

Gutiérrez, M., Müller, M. & Bermúdez, A. Transversality and lattice surgery: Exploring realistic routes toward coupled logical qubits with trapped-ion quantum processors. Phys. Rev. A 99, 022330 (2019).

Erhard, A. et al. Entangling logical qubits with lattice surgery. Nature 589, 220–224 (2021).

Besedin, I. et al. Realizing lattice surgery on two distance-three repetition codes with superconducting qubits. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.04612 (2025).

Zhang, B. et al. Leveraging erasure errors in logical qubits with metastable 171Yb atoms. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.13724 (2025).

Bombin, H. & Martin-Delgado, M.-A. Topological computation without braiding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 160502 (2007).

Kubica, A., Yoshida, B. & Pastawski, F. Unfolding the color code. New J. Phys. 17, 083026 (2015).

Campbell, E. T. The smallest interesting colour code. Blog post (2016).

Bravyi, S. & Kitaev, A. Universal quantum computation with ideal Clifford gates and noisy ancillas. Phys. Rev. A 71, 022316 (2005).

Goto, H. Minimizing resource overheads for fault-tolerant preparation of encoded states of the Steane code. Sci. Rep. 6, 19578 (2016).

Grover, L. K. Quantum mechanics helps in searching for a needle in a haystack. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 325 (1997).

Boyer, M., Brassard, G., Høyer, P. & Tapp, A. Tight bounds on quantum searching. Fortschr. Phys. 46, 493–505 (1998).

Chakrabarty, I., Khan, S. & Singh, V. Dynamic Grover search: Applications in recommendation systems and optimization problems. Quantum Inf. Process. 16, 1–21 (2017).

Roget, M., Guillet, S., Arrighi, P. & Di Molfetta, G. Grover search as a naturally occurring phenomenon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 180501 (2020).

Tezuka, H., Nakaji, K., Satoh, T. & Yamamoto, N. Grover search revisited: Application to image pattern matching. Phys. Rev. A 105, 032440 (2022).

Nagib, O., Saffman, M. & Mølmer, K. Efficient preparation of entangled states in cavity QED with Grover’s algorithm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 050601 (2025).

NJavadi-Abhari, A. et al. Qiskit textbook: Grover’s Algorithm. https://github.com/Qiskit/textbook/blob/main/notebooks/ch-algorithms/grover.ipynb.

Figgatt, C. et al. Complete 3-qubit Grover search on a programmable quantum computer. Nat. Commun. 8, 1918 (2017).

Brickman, K.-A. et al. Implementation of Grover’s quantum search algorithm in a scalable system. Phys. Rev. A 72, 050306 (2005).

AbuGhanem, M. Characterizing Grover search algorithm on large-scale superconducting quantum computers. Sci. Rep. 15, 1281 (2025).

Roy, T. et al. A programmable three-qubit superconducting processor with all-to-all connectivity. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1809.00668 (2018).

DiCarlo, L. et al. Demonstration of two-qubit algorithms with a superconducting quantum processor. Nature 460, 240–244 (2009).

Thorvaldson, I. et al. Grover’s algorithm in a four-qubit silicon processor above the fault-tolerant threshold. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 427–477 (2025).

Chuang, I. L., Gershenfeld, N. & Kubinec, M. Experimental implementation of fast quantum searching. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 3408–3411 (1998).

Chen, J.-S. et al. Benchmarking a trapped-ion quantum computer with 30 qubits. Quantum 8, 1516 (2024).

Ballance, C. J., Harty, T. P., Linke, N. M., Sepiol, M. A. & Lucas, D. M. High-fidelity quantum logic gates using trapped-ion hyperfine qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 060504 (2016).

Harty, T. P. et al. High-fidelity preparation, gates, memory, and readout of a trapped-ion quantum bit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 220501 (2014).

Ruster, T. et al. A long-lived Zeeman trapped-ion qubit. Appl. Phys. B 122, 254 (2016).

Wang, P. et al. Single ion qubit with estimated coherence time exceeding one hour. Nat. Commun. 12, 233 (2021).

Debnath, S. et al. Demonstration of a small programmable quantum computer with atomic qubits. Nature 536, 63–66 (2016).

Pino, J. M. et al. Demonstration of the trapped-ion quantum CCD computer architecture. Nature 592, 209–213 (2021).

Hangleiter, D. et al. Fault-tolerant compiling of classically hard instantaneous quantum polynomial circuits on hypercubes. PRX Quantum 6, 020338 (2025).

Jain, S. et al. Penning micro-trap for quantum computing. Nature 627, 510–514 (2024).

Evered, S. J. et al. High-fidelity parallel entangling gates on a neutral-atom quantum computer. Nature 622, 268–272 (2023).

Radnaev, A. G. et al. Universal neutral-atom quantum computer with individual optical addressing and nondestructive readout. PRX Quantum 6, 030334 (2025).

Tsai, R. B.-S., Sun, X., Shaw, A. L., Finkelstein, R. & Endres, M. Benchmarking and fidelity response theory of high-fidelity Rydberg entangling gates. PRX Quantum 6, 010331 (2025).

Zen, R. et al. Quantum circuit discovery for fault-tolerant logical state preparation with reinforcement learning. Phys. Rev. X 15, 041012 (2025).

Bonilla Ataides, J. P., Tuckett, D. K., Bartlett, S. D., Flammia, S. T. & Brown, B. J. The XZZX surface code. Nat. Commun. 12, 2172 (2021).

Schindler, P. et al. A quantum information processor with trapped ions. NJP 15, 12 (2013).

Dasu, S. et al. Order-of-magnitude extension of qubit lifetimes with a decoherence-free subspace quantum error correction code. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.22107 (2025).

Torosov, B. T., Ivanov, S. S. & Vitanov, N. V. Narrowband and passband composite pulses for variable rotations. Phys. Rev. A 102, 013105 (2020).

Ryan-Anderson, C. PECOS: performance estimator of codes on surfaces. GitHub.

Qiskit Quantum Information. https://docs.quantum.ibm.com/api/qiskit/quantum_info.

Pal, A. K. et al. Relaxation times do not capture logical qubit dynamics. Quantum 6, 632 (2022).

Poulin, D. Optimal and efficient decoding of concatenated quantum block codes. Phys. Rev. A 74, 052333 (2006).

Gottesman, D. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant overhead. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1310.2984 (2013).

Breuckmann, N. P. & Eberhardt, J. N. Quantum low-density parity-check codes. PRX Quantum 2, 040101 (2021).

Old, J., Rispler, M. & Müller, M. Lift-connected surface codes. Quantum Sci. Technol. 9, 045012 (2024).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under Grant Agreement Number 101114305 (‘MILLENION-SGA1’ EU Project) (T.M., M. Meyer, M. Müller), the US Army Research Office through Grant Number W911NF-21-1-0007 (F.B., T.M., M. Müller), the Austrian Research Promotion Agency under Contract Number 897481 (HPQC) (T.M.) supported by the European Union—NextGenerationEU, the Austrian Science Fund (FWF Grant-DOI 10.55776/F71) (SFB BeyondC) (T.M.), Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), under the Entangled Logical Qubits program through Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-23-2-0216 (I.P., F.B., R.F., A.S., M.-Meyer, T.M., M. Müller). We further receive support from the IQI GmbH, and by the German ministry of science and education (BMBF) via the VDI within the project IQuAn (M. Müller), by the European ERC Starting Grant QNets through Grant No. 804247 (M. Müller) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy ‘Cluster of Excellence Matter and Light for Quantum Computing (ML4Q) EXC 2004/1’ 390534769 (M.Müller). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of IARPA, the Army Research Office, or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes, notwithstanding any copyright notation herein. We acknowledge computing time provided at the NHR Center NHR4CES at RWTH Aachen University (Project No. p0020074) (F.B., M. Müller). This is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and the state governments participating on the basis of the resolutions of the GWK for national high-performance computing at universities.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.B. developed the presented protocols and performed the numerical simulations. I.P. and R.F. implemented the presented protocols on the experimental setup and performed experiments. I.P., R.F., A.S. and M. Meyer built and maintained the experimental setup. F.B., I.P. and R.F. analyzed results. F.B. and I.P. wrote the paper, with contributions from all authors. T. M. and M. Müller supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.M. is connected to Alpine Quantum Technologies GmbH, a commercially oriented quantum computing company. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Butt, F., Pogorelov, I., Freund, R. et al. Demonstration of measurement-free universal logical quantum computation. Nat Commun 17, 995 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68533-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68533-x