Abstract

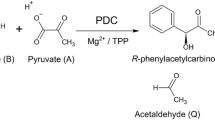

RIBULOSE-1,5-BISPHOSPHATE CARBOXYLASE/OXYGENASE (Rubisco) produces pyruvate in the chloroplast through β-elimination of the aci-carbanion intermediate1. Here we show that this side reaction supplies pyruvate for isoprenoid, fatty acid and branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis in photosynthetically active tissue. 13C labelling studies of intact Arabidopsis plants demonstrate that the total carbon commitment to pyruvate is too large for phosphoenolpyruvate to serve as a precursor. Low oxygen stimulates Rubisco carboxylase activity and increases pyruvate production and flux through the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway, which supplies the precursors for plastidic isoprenoid biosynthesis2,3. Metabolome analysis of mutants defective in phosphoenolpyruvate or pyruvate import and biochemical characterization of isolated chloroplasts further support Rubisco as the main source of pyruvate in chloroplasts. Seedlings incorporated exogenous,13C-labelled pyruvate into MEP pathway intermediates, while adult plants did not, underscoring the developmental transition in pyruvate sourcing. Rubisco β-elimination leading to pyruvate constituted 0.7% of the product profile in in vitro assays, which translates to 2% of the total carbon leaving the Calvin–Benson–Bassham cycle. These insights solve the “pyruvate paradox”4, improve the fit of metabolic models for central metabolism and connect the MEP pathway directly to carbon assimilation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All study data are included in the Letter and/or its supplementary and extended information. The isotopic labelling data displayed in Figs. 2 and 3 are compiled in Supplementary Dataset 4. The raw MS data supporting Figs. 1–4 and Extended Data Figs. 1–10 are available under identifier MSV000095073 at the MassIVE data repository (https://massive.ucsd.edu/). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Andrews, T. J. & Kane, H. J. Pyruvate is a by-product of catalysis by ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 9447–9452 (1991).

Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. & Boronat, A. Elucidation of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria and plastids: a metabolic milestone achieved through genomics. Plant Physiol. 130, 1079–1089 (2002).

Phillips, M. A., León, P., Boronat, A. & Rodríguez-Concepción, M. The plastidial MEP pathway: unified nomenclature and resources. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 619–623 (2008).

Sharkey, T. D. The end game(s) of photosynthetic carbon metabolism. Plant Physiol. 195, 67–78 (2024).

Bergman, M. E., González-Cabanelas, D., Wright, L. P., Walker, B. J. & Phillips, M. A. Isotope ratio-based quantification of carbon assimilation highlights the role of plastidial isoprenoid precursor availability in photosynthesis. Plant Methods 17, 32 (2021).

Phillips, M. A. & Croteau, R. B. Resin-based defenses in conifers. Trends Plant Sci. 4, 184–190 (1999).

McCormick, A. C., Unsicker, S. B. & Gershenzon, J. The specificity of herbivore-induced plant volatiles in attracting herbivore enemies. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 303–310 (2012).

Banerjee, A. & Sharkey, T. D. Methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway metabolic regulation. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 1043–1055 (2014).

Havaux, M. Plastoquinone in and beyond photosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 25, 1252–1265 (2020).

De Vriese, K., Pollier, J., Goossens, A., Beeckman, T. & Vanneste, S. Dissecting cholesterol and phytosterol biosynthesis via mutants and inhibitors. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 241–253 (2020).

Gershenzon, J. & Dudareva, N. The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 408–414 (2007).

Brilli, F. et al. Response of isoprene emission and carbon metabolism to drought in white poplar (Populus alba) saplings. N. Phytol. 175, 244–254 (2007).

Guidolotti, G. et al. Emission of constitutive isoprene, induced monoterpenes, and other volatiles under high temperatures in Eucalyptus camaldulensis: a 13C labelling study. Plant, Cell Environ. 42, 1929–1938 (2019).

Kreuzwieser, J. et al. Xylem-transported glucose as an additional carbon source for leaf isoprene formation in Quercus robur. N. Phytol. 156, 171–178 (2002).

Trowbridge, A. M. et al. Contribution of various carbon sources toward isoprene biosynthesis in poplar leaves mediated by altered atmospheric CO2 concentrations. PLoS ONE 7, e32387 (2012).

Bergman, M. E. et al. An Arabidopsis GCMS chemical ionization technique to quantify adaptive responses in central metabolism. Plant Physiol. 189, 2072–2090 (2022).

Szecowka, M. et al. Metabolic fluxes in an illuminated Arabidopsis rosette. Plant Cell 25, 694–714 (2013).

Andriotis, V. M. E., Kruger, N. J., Pike, M. J. & Smith, A. M. Plastidial glycolysis in developing Arabidopsis embryos. N. Phytol. 185, 649–662 (2010).

Prabhakar, V. et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate provision to plastids is essential for gametophyte and sporophyte development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22, 2594–2617 (2010).

Prabhakar, V. et al. Molecular and functional characterization of the plastid-localized phosphoenolpyruvate enolase (ENO1) from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 583, 983–991 (2009).

Andre, C., Froehlich, J. E., Moll, M. R. & Benning, C. A heteromeric plastidic pyruvate kinase complex involved in seed oil biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 2006–2022 (2007).

Staehr, P. et al. Reticulate leaves and stunted roots are independent phenotypes pointing at opposite roles of the phosphoenolpyruvate/phosphate translocator defective in cue1 in the plastids of both organs. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 126 (2014).

Streatfield, S. J. et al. The phosphoenolpyruvate/phosphate translocator is required for phenolic metabolism, palisade cell development, and plastid-dependent nuclear gene expression. Plant Cell 11, 1609–1621 (1999).

Voll, L. et al. The phenotype of the Arabidopsis cue1 mutant is not simply caused by a general restriction of the shikimate pathway. Plant J. 36, 301–317 (2003).

Furumoto, T. et al. A plastidial sodium-dependent pyruvate transporter. Nature 476, 472–475 (2011).

Stitt, M. & Ap Rees, T. Capacities of pea chloroplasts to catalyse the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway and glycolysis. Phytochem 18, 1905–1911 (1979).

Flores-Tornero, M. et al. Overexpression of the triose phosphate translocator (TPT) complements the abnormal metabolism and development of plastidial glycolytic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mutants. Plant J. 89, 1146–1158 (2017).

Liang, C. et al. Impacts of high ATP supply from chloroplasts and mitochondria on the leaf metabolism of Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 922 (2015).

Yoshida, K. & Hisabori, T. Biochemical basis for redox regulation of chloroplast-localized phosphofructokinase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 62, 401–410 (2021).

Okegawa, Y. As clear as night and day: redox-dependent metabolic switching in chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 62, 389–391 (2021).

Fu, X., Gregory, L. M., Weise, S. E. & Walker, B. J. Integrated flux and pool size analysis in plant central metabolism reveals unique roles of glycine and serine during photorespiration. Nat. Plants 9, 169–178 (2023).

Xu, Y., Wieloch, T., Kaste, J. A. M., Shachar-Hill, Y. & Sharkey, T. D. Reimport of carbon from cytosolic and vacuolar sugar pools into the Calvin–Benson cycle explains photosynthesis labeling anomalies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2121531119 (2022).

Wright, L. P. et al. Deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate synthase controls flux through the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 165, 1488–1504 (2014).

Banerjee, A. et al. Feedback inhibition of deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase regulates the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 16926–16936 (2013).

Di, X. et al. MEP pathway products allosterically promote monomerization of deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase to feedback-regulate their supply. Plant Commun. 4, 100512 (2023).

Pulido, P., Toledo-Ortíz, G., Phillips, M. A., Wright, L. P. & Rodríguez-Concepción, M. Arabidopsis J-protein J20 delivers the first enzyme of the plastidial isoprenoid pathway to protein quality control. Plant Cell 25, 4183–4194 (2013).

Rivasseau, C. et al. Accumulation of 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate in illuminated plant leaves at supraoptimal temperatures reveals a bottleneck of the prokaryotic methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 82–92 (2009).

Knappe, S., Flugge, U. I. & Fischer, K. Analysis of the plastidic phosphate translocator gene family in Arabidopsis and identification of new phosphate translocator-homologous transporters, classified by their putative substrate-binding site. Plant Physiol. 131, 1178–1190 (2003).

Xu, Y. et al. The metabolic origins of non-photorespiratory CO2 release during photosynthesis: a metabolic flux analysis. Plant Physiol. 186, 297–314 (2021).

Winter, D. et al. An ‘electronic fluorescent pictograph’ browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS ONE 2, e718 (2007).

Evans, S. E. et al. Plastid ancestors lacked a complete Entner–Doudoroff pathway, limiting plants to glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway. Nat. Commun. 15, 1102 (2024).

Portis, A. R. Jr, Li, C., Wang, D. & Salvucci, M. E. Regulation of Rubisco activase and its interaction with Rubisco. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 1597–1604 (2007).

Evans, S. E. et al. Design and fabrication of an improved dynamic flow cuvette for 13CO2 labeling in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Methods 18, 40 (2022).

Edwards, K., Johnstone, C. & Thompson, C. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plant genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 1349 (1991).

Phillips, M. A., D’Auria, J. C., Luck, K. & Gershenzon, J. Evaluation of candidate reference genes for real-time quantitative PCR of plant samples using purified cDNA as template. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 27, 407–416 (2009).

Duursma, R. A. Plantecophys—an R package for analysing and modelling leaf gas exchange data. PLoS ONE 10, e0143346 (2015).

Alseekh, S. et al. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics: a guide for annotation, quantification and best reporting practices. Nat. Methods 18, 747–756 (2021).

Nicodemus, T. J., Behrens, M., Allen, J. W., DiRusso, C. C. & Black, P. N. Co-cultures of Coccomyxa subellipsoidea and Psuedomonas denitrificans increases lipid accumulation independent of nutrient conditions. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 19, 101197 (2022).

Cauz-Santos, L. A. et al. A repertory of rearrangements and the loss of an inverted repeat region in Passiflora chloroplast genomes. Genome Biol. Evol. 12, 1841–1857 (2020).

Hall, N. P. & Tolbert, N. A rapid procedure for the isolation of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from spinach leaves. FEBS Lett. 96, 167–169 (1978).

Desai, R. K., Streefland, M., Wijffels, R. H. & Eppink, M. H. Extraction and stability of selected proteins in ionic liquid based aqueous two phase systems. Green Chem. 16, 2670–2679 (2014).

Xu, Y. et al. Daylength variation affects growth, photosynthesis, leaf metabolism, partitioning, and metabolic fluxes. Plant Physiol. 194, 475–490 (2023).

Young, J. D., Shastri, A. A., Stephanopoulos, G. & Morgan, J. A. Mapping photoautotrophic metabolism with isotopically nonstationary 13C flux analysis. Metab. Eng. 13, 656–665 (2011).

Young, J. D., Walther, J. L., Antoniewicz, M. R., Yoo, H. & Stephanopoulos, G. An elementary metabolite unit (EMU) based method of isotopically nonstationary flux analysis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 99, 686–699 (2008).

Zamboni, N., Fendt, S.-M., Rühl, M. & Sauer, U. 13C-based metabolic flux analysis. Nat. Protoc. 4, 878–892 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a Discovery grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (no. RGPIN-2017-06400) and a John Evans Leadership Fund grant from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (no. 36131). This work was also supported by a grant from the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the United States Department of Energy (grant no. DE-FG02-91ER20021). T.D.S. received partial salary support from Michigan AgBioResearch. Rubisco was isolated from N. tabacum by A. Johnson; we thank L. Gregory for help with the Rubisco assay. We also acknowledge help from the MSU Mass Spectrometry and Metabolomics Core Facility, and we thank the MSU Institute for Cyber-Enabled Research for providing a high-performance computing cluster and services and J. Young for making INCA accessible. We also acknowledge a generous NSERC CGSD graduate scholarship supporting M.E.B. and thank UTM staff members B. Pitton of the Teaching Greenhouse, P. Duggan of the Academic Machine Shop and Stores Supervisor M. Malcolm (POE) for their excellent technical and logistical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.E.E. labelled plants and performed the MS analysis. S.E.E. and M.E.B. performed data analysis. S.A.F. analysed fatty acid methyl esters and amino acids. Y.L. prepared plants for experiments and genotyped mutants. Y.X. quantified Rubisco product profiles and carried out the mass flux analysis. T.D.S. edited the manuscript and analysed Rubisco-catalysed pyruvate production. M.A.P. wrote the manuscript and directed the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Ewa Swiezewska and Mirko Zaffagnini for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Enzyme activity of plastid-localized ENO and PGM from isolated chloroplasts of Arabidopsis.

Crude protein extracts were obtained from intact chloroplasts isolated from 7-day-old seedlings and rosette-staged leaves (42 days) and incubated with 2 mM 3-PGA or 1 mM 2-PGA to assess the relative activity of PGM and ENO glycolytic enzymes. a, Assay showing lower activity of plastidic ENO in rosette leaves when compared to seedlings. b, Coupled enzyme activity of PGM and ENO shows low conversion of 3-PGA to PEP in rosette leaves (ENO P = 0.0002; PGM + ENO P = 0.0026). c, Representative chromatograms depicting PEP product formation after one hour incubation with 2-PGA. All chromatograms are shown on the same scale. d, Intact chloroplasts isolated from 7-day-old seedlings. Bar = 10 μm. The experiment was repeated once with identical results. Error bars represent standard deviation of measurements (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences (** P < 0.001; *** P < 0.0001) as determined by Student’s two-sided t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 2 13C label incorporation and absolute concentrations of photorespiratory intermediates in Arabidopsis leaves under normal (21%) and low (1%) oxygen conditions.

Details on administration of 13C under physiological conditions, extraction of metabolites, and analysis by liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry are given in the Methods section. For absolute quantification, the data are shown as box plots, with the central line indicating the median, upper and lower bounds representing quartile 3 (75th percentile) and quartile 1 (25th percentile), respectively, and the whiskers denote the minima and maxima of the data points. Mean values of n = 18–25 individual plants are shown as yellow diamonds (Glycerate P = 0.0022). Asterisks indicate significant differences at * P < 0.01, based on Student’s two-sided t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Adaptation of Arabidopsis plants to low oxygen conditions.

a, Representative total carbon assimilation (A) during adaptation of plants to normal (21%) or low (1%) oxygen conditions in a dynamic flow cuvette connected to a LI-COR 6800 photosynthesis system. The flat line indicates a photosynthetic steady state prior to initiation of 13CO2 labelling, indicated by the arrow. b, Metabolite concentrations were monitored in time course plants for any changes in metabolite pool size during the labelling experiment. The low R2 values indicate metabolite pool size is independent of duration of the labelling experiment. Triose-P, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate + dihydroxyacetone phosphate; DXP, 1-deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate; MEcDP, 2-C-methylerythritol-2,4-cyclodiphoshate; IDP/DMADP, isopentenyl and dimethylallyl diphosphate.

Extended Data Fig. 4 13C labelling incorporation and absolute concentrations of glycolytic and Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle intermediates under normal (21%) and low (1%) oxygen conditions.

For absolute quantification, the data are visualized as box plots, with the central line indicating the median, upper and lower bounds represent quartile 3 (75th percentile) and quartile 1 (25th percentile), respectively, and the whiskers denote the minima and maxima of the data points. Mean values (yellow diamonds) show averages (n = 18–25) (PEP P = 0.0012). Asterisks indicate significant differences at * P < 0.01, based on Student’s two-sided t-test. G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; F6P, fructose-5-phosphate; S7P, sedoheptulose-7-phosphate; Xu5P, xylulose-5-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

Extended Data Fig. 5 13CO2 in vivo labelling of Arabidopsis seedlings.

F = fractional 13C labelling of the carbon atoms in the indicated central metabolite pool. Seedlings were labelled under normal (21%) or low (1%) oxygen conditions to observe the effect of stimulating Rubisco carboxylase activity on seedling metabolism. Seedlings grown for 7 d on solid media were adapted in a controlled environment dynamic flow cuvette (lower right). After 1 h of monitoring with a LI-COR 6800 system to verify the seedlings had reached a photosynthetic steady state, the air supply (normal or low oxygen) was switched to one containing 400 μL ∙ L−1 13CO2. The seedlings were incubated in the 13CO2 containing atmosphere for 30 min and then flash frozen for lyophilization and metabolite extraction. Details of the analysis of central metabolites and calculation of label incorporation are provided in online methods. Bar graphs show means of 3–6 individual plates while error bars show standard deviation (Serine P = 0.0008). The individual data points are overlain as dots. Asterisks indicate statistical significance, based on Student’s two-sided t-test (* = P < 0.01). Otherwise, no statistically significant difference was observed. DXP, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate; MEcDP, 2-C-methylerythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate; IDP/DMADP, isopentenyl and dimethylallyl diphosphate; 3-PGA, 3-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; S7P, sedoheptulose-7-phosphate; Xu5P, xylulose-5-phosphate; R5P, ribose-5-phosphate.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Incorporation of [2-13C] pyruvate into intermediates of the 2-C-methylerythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in Arabidopsis seedlings (7-day old) vs. rosettes (42-day old).

Following incubation with [2-13C] pyruvate, 13C was detected in MEP pathway intermediates in seedlings but not in rosette leaves. a, Label incorporation into 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP). b, Label incorporation into 2-C-methylerythritol-2,4,-cyclodiphosphate (MEcDP); c, Label incorporation into isopentenyl and dimethylallyl diphosphate (IDP/DMADP). IDP and DMADP, which are the products of both the MEP pathway in the chloroplast and the mevalonate pathway in the cytosol, displayed measurable label incorporation in both seedlings and rosette leaves. d, Detection of exogenously supplied [2-13C] pyruvate in extracts of seedlings or rosette leaves. Seedlings were grown in ¾ MS media supplemented (or not) with 5 mM 2-13C pyruvate for 7 days while leaves of rosette plants were infiltrated for 24 hours with MS media supplemented with labelled pyruvate at the same concentration (or MS media only for controls). Pooled leaves or seedlings were flash-frozen and extracted for LCMS/MS and GCMS analysis. Percent labelling incorporation into each metabolite was calculated using the equation (\(1/N\)) \({\sum }_{i}^{N}Mi\times i\), where N is the number of carbon atoms in the molecule and Mi is the fractional abundance of the ith isotopologue. Error bars indicate standard deviation of measurement (n = 3-4). Asterisks indicate significant differences (** P < 0.001; *** P < 0.0001) as determined by Student’s two-sided t-test. n.s., Not statistically significant.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Genotyping of mutants deficient in PPT1 (cue1) and BASS2 (bass2-1 and bass2-2).

a, b Genotyping of bass2-1 and bass2-2 mutants using gene specific primers (BASS2 LP and RP or full-length (FL) primers) and T-DNA left border primers (LBb1.3). Amplification was performed using genomic DNA. c, RT-PCR analysis of PPT1 and BASS2 in cue1, bass2-1 and bass2-2 mutant plants. The cue1 mutant lacks full-length transcripts for PPT1, and bass2 mutant lines similarly lack full-length transcripts for BASS2. d, The Arabidopsis thaliana dihydroxy-acid dehydratase gene (DHAD; AT3G23940) was used as a control to confirm cDNA quality. M, DNA marker. e, Uncropped gel images shown in a-d. PCR and gel analyses in a-d were repeated at least once with identical results.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Roles of transporters in supplying pyruvate and phosphoenolpyruvate for amino acid biosynthesis in the chloroplast.

Concentrations of aromatic (phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine) and branched chain amino acids (isoleucine, leucine and valine) were analyzed by liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry in leaf extracts from wild-type (WT), cue1, and bass2 plants. Raw peak areas were normalized to the internal standard N-methylglucamine and compared to external standard calibration curves derived from authentic standards. The data are displayed as box plots, with the central line indicating the median and upper and lower bounds representing quartile 3 (75th percentile) and quartile 1 (25th percentile), respectively. Whiskers denote the minima and maxima of the data points. Yellow diamonds indicate mean values (n = 6-7 individual plants). Asterisk indicates significant differences (* P < 0.01, ** P < 0.001, *** P < 0.0001) based on Student’s two-sided t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) analysis in Arabidopsis wild-type (WT), cue1, and bass2 mutant plants.

a, Representative chromatogram showing elution profile of FAMEs by gas chromatography – mass spectrometry. b, Total fatty acid content of each genotype expressed as summed peak areas of FAMEs relative to the internal standards (IS), triheptadecanoin (C17) and dotriacontane (n = 4–6). There were no statistical differences in total fatty acid content between groups (P < 0.01), but content of some individual components were lower in cue1 compared to WT (see Supplementary Dataset 2 for details).

Extended Data Fig. 10 CO2 assimilation (A) and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) in Arabidopsis wild-type (WT), bass2 and cue1 mutant plants.

A/Ci curves were fit based on the Farquhar-von Caemmerer-Berry (FvCB) model of photosynthesis using the plantecophys package on R46. Estimates of Vcmax (maximum Rubisco carboxylation rate) and Jmax (the maximum rate of electron transport) are presented as mean ± SD from individual fit (n = 3-4 plants). Ac represents photosynthesis limited by rubisco, while Aj indicates limitation due to RuBP-regeneration.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1 and Tables 1–5.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Datasets 1–4.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

ChemDraw file for the Rubisco mechanism shown in Fig. 1b.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, S.E., Xu, Y., Bergman, M.E. et al. Rubisco supplies pyruvate for the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol-4-phosphate pathway. Nat. Plants 10, 1453–1463 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01791-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01791-z

This article is cited by

-

Non-canonical plant metabolism

Nature Plants (2025)

-

Time-resolved targeted metabolomics shows an abrupt switch from Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle to tricarboxylic acid cycle when the light is turned off

Photosynthesis Research (2025)