Abstract

Polycomb protein-mediated transcriptional repression plays a crucial role in the regulation of responses to environmental stimuli in multicellular eukaryotes, but the underlying signalling events remain elusive. During Arabidopsis vernalization, prolonged cold exposure results in the formation of a Polycomb-repressed domain at the potent floral repressor FLC to confer its stable silencing upon temperature rise or epigenetic ‘memory of prolonged cold’, enabling the plants to bloom in spring. Here we report that the evolutionarily conserved casein kinase CK2 phosphorylates and thus stabilizes histone 3 lysine-27 (H3K27) methyltransferases (PRC2 subunits) to promote H3K27 trimethylation throughout the Arabidopsis genome. We found that prolonged cold induces progressive CK2 accumulation, leading to a gradual accumulation of cellular PRC2. We further show that the cold-CK2–PRC2 signalling promotes increasing PRC2 enrichment on FLC chromatin during prolonged cold exposure as well as post-cold PRC2 spreading across FLC to establish a Polycomb-repressed domain for FLC repression in warmth. Thus, this signalling cascade transduces prolonged cold exposure, but not cold spells, into epigenetic memory of prolonged cold in warmth during vernalization. CK2 phosphorylation motifs are widely present in H3K27 methyltransferases from plants and animals. Our study reveals a new layer of control of PRC2 activity in multicellular organisms.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The raw data of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq from this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive database at the National Genomics Data Center (China) with the following accession numbers: CRA015362 (ChIP-seq) and CRA015386 (RNA-seq). Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Blackledge, N. P. & Klose, R. J. The molecular principles of gene regulation by Polycomb repressive complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 815–833 (2021).

Mozgova, I. & Hennig, L. The Polycomb group protein regulatory network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66, 269–296 (2015).

Lanzuolo, C. & Orlando, V. Memories from the Polycomb group proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 46, 561–589 (2012).

Chanvivattana, Y. et al. Interaction of Polycomb-group proteins controlling flowering in Arabidopsis. Development 131, 5263–5276 (2004).

Caretti, G., Palacios, D., Sartorelli, V. & Puri, P. L. Phosphoryl-EZH-ion. Cell Stem Cell 8, 262–265 (2011).

Chen, S. et al. Cyclin-dependent kinases regulate epigenetic gene silencing through phosphorylation of EZH2. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 1108–1114 (2010).

Cha, T. L. et al. Akt-mediated phosphorylation of EZH2 suppresses methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Science 310, 306–310 (2005).

Ghate, N. B. et al. Phosphorylation and stabilization of EZH2 by DCAF1/VprBP trigger aberrant gene silencing in colon cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 2140 (2023).

Bouche, F., Woods, D. P. & Amasino, R. M. Winter memory throughout the plant kingdom: different paths to flowering. Plant Physiol. 173, 27–35 (2017).

Andres, F. & Coupland, G. The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 627–639 (2012).

Gao, Z. & He, Y. Molecular epigenetic understanding of winter memory in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 194, 1952–1961 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Distinct phases of Polycomb silencing to hold epigenetic memory of cold in Arabidopsis. Science 357, 1142–1145 (2017).

Choi, K. et al. The FRIGIDA complex activates transcription of FLC, a strong flowering repressor in Arabidopsis, by recruiting chromatin modification factors. Plant Cell 23, 289–303 (2011).

Angel, A., Song, J., Dean, C. & Howard, M. A Polycomb-based switch underlying quantitative epigenetic memory. Nature 476, 105–108 (2011).

Zhang, Z., Luo, X., Yang, Y. & He, Y. Cold induction of nuclear FRIGIDA condensation in Arabidopsis. Nature 619, E27–E32 (2023).

Sung, S. & Amasino, R. M. Vernalization in Arabidopsis thaliana is mediated by the PHD finger protein VIN3. Nature 427, 159–164 (2004).

De Lucia, F., Crevillen, P., Jones, A. M., Greb, T. & Dean, C. A PHD-Polycomb repressive complex 2 triggers the epigenetic silencing of FLC during vernalization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 16831–16836 (2008).

Kim, D. H. & Sung, S. Coordination of the vernalization response through a VIN3 and FLC gene family regulatory network in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 454–469 (2013).

Yuan, W. et al. A cis cold memory element and a trans epigenome reader mediate Polycomb silencing of FLC by vernalization in Arabidopsis. Nat. Genet. 48, 1527–1534 (2016).

Gao, Z. et al. A pair of readers of bivalent chromatin mediate formation of Polycomb-based “memory of cold” in plants. Mol. Cell 83, 1109–1124 (2023).

Jiang, D. & Berger, F. DNA replication-coupled histone modification maintains Polycomb gene silencing in plants. Science 357, 1146–1149 (2017).

Wood, C. C. et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana vernalization response requires a Polycomb-like protein complex that also includes VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE 3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 14631–14636 (2006).

Gibbs, D. J. et al. Oxygen-dependent proteolysis regulates the stability of angiosperm Polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit VERNALIZATION 2. Nat. Commun. 9, 5438 (2018).

Ye, R. et al. Glucose-driven TOR-FIE-PRC2 signalling controls plant development. Nature 609, 986–993 (2022).

Zhao, Y. S., Antoniou-Kourounioti, R. L., Calder, G., Dean, C. & Howard, M. Temperature-dependent growth contributes to long-term cold sensing. Nature 583, 825–829 (2020).

Katz, A., Oliva, M., Mosquna, A., Hakim, O. & Ohad, N. FIE and CURLY LEAF Polycomb proteins interact in the regulation of homeobox gene expression during sporophyte development. Plant J. 37, 707–719 (2004).

Fatihi, A., Zbierzak, A. M. & Dormann, P. Alterations in seed development gene expression affect size and oil content of Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 163, 973–985 (2013).

Roffey, S. E. & Litchfield, D. W. CK2 regulation: perspectives in 2021. Biomedicines 9, 1361 (2021).

Mulekar, J. J. & Huq, E. Expanding roles of protein kinase CK2 in regulating plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 2883–2893 (2014).

Gao, Z. et al. An AUTS2-Polycomb complex activates gene expression in the CNS. Nature 516, 349–354 (2014).

Kawaguchi, T., Machida, S., Kurumizaka, H., Tagami, H. & Nakayama, J. I. Phosphorylation of CBX2 controls its nucleosome-binding specificity. J. Biochem. 162, 343–355 (2017).

Zhu, J. et al. CK2 promotes jasmonic acid signaling response by phosphorylating MYC2 in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 619–630 (2023).

Lu, S. X. et al. A role for protein kinase casein kinase2 alpha-subunits in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Physiol. 157, 1537–1545 (2011).

Salinas, P. et al. An extensive survey of CK2 alpha and beta subunits in Arabidopsis: multiple isoforms exhibit differential subcellular localization. Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 1295–1308 (2006).

Hardtke, C. S. et al. HY5 stability and activity in Arabidopsis is regulated by phosphorylation in its COP1 binding domain. EMBO J. 19, 4997–5006 (2000).

Bu, Q. et al. Phosphorylation by CK2 enhances the rapid light-induced degradation of PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 1 in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12066–12074 (2011).

Sugano, S., Andronis, C., Ong, M. S., Green, R. M. & Tobin, E. M. The protein kinase CK2 is involved in regulation of circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 12362–12366 (1999).

Mulekar, J. J., Bu, Q., Chen, F. & Huq, E. Casein kinase II alpha subunits affect multiple developmental and stress-responsive pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 69, 343–354 (2012).

Schubert, D. et al. Silencing by plant Polycomb-group genes requires dispersed trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27. EMBO J. 25, 4638–4649 (2006).

Kinoshita, E. & Kinoshita-Kikuta, E. Improved Phos-tag SDS-PAGE under neutral pH conditions for advanced protein phosphorylation profiling. Proteomics 11, 319–323 (2011).

Jiang, D., Wang, Y., Wang, Y. & He, Y. Repression of FLOWERING LOCUS C and FLOWERING LOCUS T by the Arabidopsis Polycomb repressive complex 2 components. PLoS ONE 3, e3404 (2008).

Lopez-Vernaza, M. et al. Antagonistic roles of SEPALLATA3, FT and FLC genes as targets of the Polycomb group gene CURLY LEAF. PLoS ONE 7, e30715 (2012).

Ubersax, J. A. & Ferrell, J. E. Jr. Mechanisms of specificity in protein phosphorylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 530–541 (2007).

Niefind, K., Guerra, B., Ermakowa, I. & Issinger, O. G. Crystal structure of human protein kinase CK2: insights into basic properties of the CK2 holoenzyme. EMBO J. 20, 5320–5331 (2001).

Lee, I., Michaels, S. D., Masshardt, A. S. & Amasino, R. M. The late-flowering phenotype of FRIGIDA and luminidependens is suppressed in the Landsberg erecta strain of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 6, 903–909 (1994).

Searle, I. et al. The transcription factor FLC confers a flowering response to vernalization by repressing meristem competence and systemic signaling in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 20, 898–912 (2006).

Gu, X., Xu, T. & He, Y. A histone H3 lysine-27 methyltransferase complex represses lateral root formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 7, 977–988 (2014).

Siddiqui-Jain, A. et al. CX-4945, an orally bioavailable selective inhibitor of protein kinase CK2, inhibits prosurvival and angiogenic signaling and exhibits antitumor efficacy. Cancer Res. 70, 10288–10298 (2010).

Shu, J. et al. Genome-wide occupancy of histone H3K27 methyltransferases CURLY LEAF and SWINGER in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Direct 3, e00100 (2019).

Xi, Y., Park, S. R., Kim, D. H., Kim, E. D. & Sung, S. Transcriptome and epigenome analyses of vernalization in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 103, 1490–1502 (2020).

Kim, D. H., Doyle, M. R., Sung, S. & Amasino, R. M. Vernalization: winter and the timing of flowering in plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 25, 277–299 (2009).

Rivero, L. et al. Handling Arabidopsis plants: growth, preservation of seeds, transformation, and genetic crosses. Methods Mol. Biol. 1062, 3–25 (2014).

Pasini, D., Bracken, A. P., Jensen, M. R., Denchi, E. L. & Helin, K. SUZ12 is essential for mouse development and for EZH2 histone methyltransferase activity. EMBO J. 23, 4061–4071 (2004).

Montgomery, N. D. et al. The murine Polycomb group protein EED is required for global histone H3 lysine-27 methylation. Curr. Biol. 15, 942–947 (2005).

Jeong, C. W. et al. An E3 ligase complex regulates SET-domain Polycomb group protein activity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8036–8041 (2011).

Moeller, H. B., Aroankins, T. S., Slengerik-Hansen, J., Pisitkun, T. & Fenton, R. A. Phosphorylation and ubiquitylation are opposing processes that regulate endocytosis of the water channel aquaporin-2. J. Cell Sci. 127, 3174–3183 (2014).

Nguyen, L. K., Kolch, W. & Kholodenko, B. N. When ubiquitination meets phosphorylation: a systems biology perspective of EGFR/MAPK signalling. Cell Commun. Signal. 11, 52 (2013).

Fiedler, M. et al. Head-to-tail polymerization by VEL proteins underpins cold-induced Polycomb silencing in flowering control. Cell Rep. 41, 111607 (2022).

Doyle, M. R. & Amasino, R. M. A single amino acid change in the Enhancer of Zeste ortholog CURLY LEAF results in vernalization-independent, rapid flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 151, 1688–1697 (2009).

Michaels, S. D. & Amasino, R. M. FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell 11, 949–956 (1999).

Yang, H., Howard, M. & Dean, C. Antagonistic roles for H3K36me3 and H3K27me3 in the cold-induced epigenetic switch at Arabidopsis FLC. Curr. Biol. 24, 1793–1797 (2014).

Kaneko, S. et al. Phosphorylation of the PRC2 component Ezh2 is cell cycle-regulated and up-regulates its binding to ncRNA. Genes Dev. 24, 2615–2620 (2010).

Gong, L. et al. CK2-mediated phosphorylation of SUZ12 promotes PRC2 function by stabilizing enzyme active site. Nat. Commun. 13, 6781 (2022).

Makarevich, G. et al. Different Polycomb group complexes regulate common target genes in Arabidopsis. EMBO Rep. 7, 947–952 (2006).

Wang, D., Tyson, M. D., Jackson, S. S. & Yadegari, R. Partially redundant functions of two SET-domain Polycomb-group proteins in controlling initiation of seed development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 13244–13249 (2006).

Karimi, M., De Meyer, B. & Hilson, P. Modular cloning in plant cells. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 103–105 (2005).

Ma, X. et al. A robust CRISPR/Cas9 system for convenient, high-efficiency multiplex genome editing in monocot and dicot plants. Mol. Plant 8, 1274–1284 (2015).

Cao, M. et al. TMK1-mediated auxin signalling regulates differential growth of the apical hook. Nature 568, 240–243 (2019).

Uhrig, R. G., She, Y. M., Leach, C. A. & Plaxton, W. C. Regulatory monoubiquitination of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in germinating castor oil seeds. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29650–29657 (2008).

Savitski, M. M. et al. Confident phosphorylation site localization using the Mascot Delta Score. Mol. Cell Proteom. 10, M110 003830 (2011).

Towbin, H., Staehelin, T. & Gordon, J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 76, 4350–4354 (1979).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287 (2012).

Wang, Y., Gu, X., Yuan, W., Schmitz, R. J. & He, Y. Photoperiodic control of the floral transition through a distinct Polycomb repressive complex. Dev. Cell 28, 727–736 (2014).

Johnson, L., Cao, X. & Jacobsen, S. Interplay between two epigenetic marks: DNA methylation and histone H3 lysine 9 methylation. Curr. Biol. 12, 1360–1367 (2002).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Ramirez, F. et al. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W160–W165 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G. & He, Q. Y. ChIPseeker: an R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 31, 2382–2383 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Goodrich (University of Edinburgh) for kindly providing the seeds of GFP:CLF and clf-81, Y. She and an in-house mass spectrometry facility for protein phosphorylation analysis, X. Luo and Y. Li for experimental assistance, Z. Shang for bioinformatic analysis and Q. Liu for critically reading this manuscript. This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 32330007, 31830049 and 31721001 to Y.H.), Peking-Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences and Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. conceived and designed the research. X.Z., Zheng Gao, J.G., G.Q. and Y.O. designed and conducted the experiments. X.Z., Zheng Gao, Y.H. and J.G. analysed data. Zhaoxu Gao conducted bioinformatic analysis. G.Q. and P.W. analysed the mass-spectrometry data. Y.H. wrote the paper with help from X.Z. and Zheng Gao.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Ryo Fujimoto, Daniel Gibbs and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Analysis of the phosphorylation of S182 on CLF.

a, Tandem MS spectrum of the phosphopeptide IYYDQTGGEALICpSDSEEEAIDDEEEKRDFLEPEDYIIR showing the phosphorylation of S182 on the functional GFP:CLF protein extracted from Arabidopsis seedlings. b, List of phosphorylation sites in the GFP:CLF protein identified by LC-MS/MS. c, Functionality analysis of CLF:Flag, driven by a native promoter region of CLF and introduced into clf-29, a null mutant with phenotypes less severe than clf-81 that bears a point mutation in the catalytic domain39. Dots represent individual measurements (n = 12), and middle lines for medians. P values are derived from one-way ANOVA. d, Phos-tag SDS-PAGE analysis of CLF phosphorylation. Total proteins extracted from the cold-exposed seedlings of CLF:Flag (#1), were treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP), followed by separation in an SDS-PAGE gel containing 50 μM Zn2+-Phos-tag. Immunoblotting was conducted using anti-Flag. At the bottom is a normal SDS-PAGE blot, serving as a control. e, Treatment of CLFpS182:Flag (anti-Flag immunoprecipitations) with CIP. ACTIN serves an endogenous control. The experiments in (d,e) were conducted at twice independently with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Functional analysis of pS182 on CLF and conservation of the CK2 phosphorylation sites among CLF homologs in plants and animals.

a, Phenotypes of the indicated lines grown in LDs. Shown are T1 (the first generation) transgenic seedlings expressing CLFpro-CLF, CLFS182A or CLFS182T. Scale bars, 1 cm. b,c, Analysis of FLC (b) and FT (c) expression in the indicated seedlings. Two independent lines for each transgene were examined. Transcript levels were quantified by real-time PCR (qPCR), and then normalized to the constitutively-expressed PP2A. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates, and P values are derived from one-way ANOVA. d,e, Levels of H3K27me3 on total histones in the indicated seedlings, as revealed by immunoblotting with anti-H3K27me3. Representative protein blots are shown in (d), whereas relative levels of H3K27me3 are shown in (e). The levels of H3 serve as loading controls. Relative fold changes over WT (set as 1.0) are presented. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates, and P values are derived from one-way ANOVA. f, Sequence alignment of CLF homologs from land plants. The conserved Ser182 of CLF is indicated by an asterisk. g, Schematic illustration of a CK2 phosphorylation motif conserved among EZH1 homologs in animals. h, Sequence alignment of animal EZH1 homologs. Accession numbers: human EZH1, NP_001982.2; mouse EZH1, NP_001390750; chicken EZH1, XP_040509295; frog EZH1, XP_031750333; zebrafish EZH1, NP_001035072; fruitfly E(z), NP_001261682.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Analysis of ck2 mutants and transgene functionality.

a-c, Schematic illustrations of the mutations in ck2-b1, ck2-b2 (a), ck2-b3 (b) and ck2-b4 (c) mutants. Boxes for exons; A of the start codon ATG as +1. Dashes indicate the deleted DNA base pairs, while red nucleotides denote insertions. d, Knockout of CK2-B1 expression in the ck2b quadruple mutant of ck2-b1/b2-1/b3-1/b4-1, as revealed by RT-PCR. The constitutively-expressed TUBULIN2 (TUB2) serves as a loading control. The experiment was conducted twice independently with similar results. e, Flowering times of the indicated mutants grown in LDs. f,g, Functionality analysis of Flag-tagged CK2-B3 (f) and CK2-A3 (g) transgenes. These transgenes driven by respective native promoters, were introduced into ck2-a1a2a3 or ck2-b1b2b3. Two independent homozygous transgenic lines were scored for flowering times. h, Functionality analysis of CLF:HA, driven by a native promoter region of CLF and introduced into clf-29. Two independent homozygous transgenic lines were scored for flowering times. i, FLC expression in the seedlings of WT and ck2-a1a2a3. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates. Dots in (e-h) represent individual measurements (n = 12), and middle lines for medians. All data in (e-i) were analyzed by two-tailed t test.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Characterization of CLFpS182 phosphorylation.

a, Purification of recombinant CK2α3 and CK2β3 from E. coli. Affinity-purified MBP:His:CK2α3 and GST:CK2β3 were separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by staining with Coomassie blue R250. MBP, maltose-binding protein; GST for glutathione s-transferase. The experiment was conducted at least twice independently with similar results. b, Tandem MS spectrum of the phosphopeptide IYYDQTGGEALICpSDSEEEAIDDEEEKR showing the phosphorylation of S182 on CLF. A CLF fragment (aa 111-451) was phosphorylated in vitro by the reconstituted CK2 holoenzyme of CK2α3 and CK2β3, followed by tandem MS. c, Confocal fluorescent imaging of CLF:GFP and CLFS182A:GFP root tips. Root tips of 7-d-old seedlings were imaged; scale bar for 20 μm. d, Expression levels of CLF or CLF transgenes at a seedling stage. Transcript levels were quantified by qPCR and normalized to PP2A. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates. e, Functionality analysis of Flag:CLF. 15 plants per genotype were scored, and T1 plants of Flag:CLF (in clf-29) were examined. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d., and P values are derived from one-way ANOVA. f, Levels of Flag:CLF and Flag:CLFS182A in transgenic seedlings. Randomly-chosen T1 seedings were examined by immunoblotting. ACTIN serves as a loading control. The experiment was conducted twice independently with similar results. g, Relative expression of CLF and SWN in the seedlings of WT and ck2b-quad. Transcripts were quantified by qPCR and normalized to TUB2. Relative expression to WT is presented. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 5 CK2 phosphorylates the S170 on SWN for its stabilization.

a, SWNpro-SWN:9xHA is fully functional. The transgene was introduced into clf swn by genetic transformation. Seedlings were grown on half-strength MS media under a long-day (LD) condition. b, Co-immunoprecipitation of SWN with CK2β3. SWN:HA was immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag recognizing CK2β3:Flag, from the F1 seedlings of a SWN:9xHA line crossed to the CK2-B3:Flag line. The experiment was conducted twice independently with similar results. c, Confirmation of the phosphorylation of Ser170 on the SWN:HA protein in the indicated seedlings by an antibody elicited by the phosphorylated antigen of a short polypeptide conserved in CLF and SWN. SWN:HA was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA beads. Part of the samples were dephosphorylated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP), followed by western blotting. ACTIN serves as a loading control for total protein used in each anti-HA immunoprecipitation. The experiment was conducted twice independently with similar results. d,e, Immunoblotting analysis of the degradation of total SWN:HA (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated at S170) following cycloheximide (CHX) treatment. A SWN:HA line (in ck2b quad) was crossed to WT and ck2b-quad, and the resulting F1 seedlings were treated by the translation inhibitor CHX, followed by immunoblotting. Representative blots were shown in (d), while relative levels of total SWN:HA over the ‘0 h ck2b+/- sample’ (set as 1.0) are shown in (e). Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates, and P values are derived from one-way ANOVA.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Ser170 phosphorylation is essential for SWN function.

a,b, Phenotypes of swn-7, clf-29, lines of the SWN transgene in clf swn, lines of SWNS170A in clf swn, lines of SWNS170D in clf swn, and lines of SWNS170E in clf swn. Seedlings were grown on half-strength MS media for 9 d (a) and 17 d (b) under a LD condition. After germination, the clf swn mutant exhibited stunted growth and failed to continue developing. Scale bars, 2.5 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 CK2 modulates genome-wide H3K27 trimethylation and gene expression in Arabidopsis.

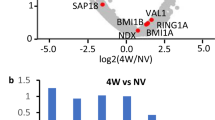

a, Principle component (PC) analysis of WT and ck2b-quad transcriptomes at a seedling stage. Data are plotted using two PCs. Three biological replicates for each genotype were performed. b, Gene Ontology (biological processes) enrichment analysis of DEGs in ck2b (relative to WT). The abscissa represents the proportion of enriched genes in each GO term, and the size of the circle indicates the number of enriched genes. P values are adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. c, Heatmaps showing H3K27me3 distribution at individual loci in WT and ck2b-quad seedlings. TSS for transcription start site, TES for transcription end site, and scales on the right represent RPM values. d,e, Correlation analysis of biological replicates of H3K27me3 ChIP-seq experiments using WT (d) and ck2b-quad (e) seedlings. Three biological replicates were performed for each genotype. Values on both x and y axes are read coverages. f, Venn diagram showing overlapping of the protein-coding genes upregulated in ck2b-quad, list of genes upregulated in clf-29 swn-4, and the protein-coding loci bearing H3K27me3. Notably, the list of genes upregulated in clf swn is from the published study49. g, Levels of H3K27me3 across the FLC locus in the seedlings of WT and clf-29. Levels of the FLC fragments immunoprecipitated by anti-H3K27me3 were quantified by qPCR and normalized to input DNA. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Expression of CK2 subunit genes and CLF over the course of prolonged cold exposure.

a-h, Expression of CK2-A1 (a), CK2-A2 (b), CK2-A3 (c), CK2-A4 (d), CK2-B1 (e), CK2-B2 (f), CK2-B3 (g) and CK2-B4 (h) in FRI-Col seedlings over the course of 35-d cold exposure. i, CLF expression over the course of 35-d cold exposure. a-i, Transcripts were quantified by qPCR and normalized to PP2A. Relative expression to pre-cold /no cold is presented, and data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates. j, Examination of CK2α3:Flag abundances following the co-treatment of CX-4945 with the protease inhibitor MG132. ACTIN serves as a loading control. The experiment was conducted twice independently with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Characterization of CK2B function in prolonged cold-induced H3K27 trimethylation.

a, Analysis of SWN:HA levels in the seedlings of ck2b+/- and ck2b-quad over the course of 35-d cold treatment. ACTIN serves as an endogenous control. The experiment was conducted twice independently with similar results. b,c, Levels of H3K27me3 on total histones in the seedlings of WT and ck2b-quad over the course of 35-d cold exposure, as revealed by immunoblotting with anti-H3K27me3. Representative protein blots are shown in (b), whereas relative levels of H3K27me3 are shown in (c). H3 serves as an endogenous control. The levels of H3K27me3 were normalized to H3; data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates, and P values are derived from one-way ANOVA.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Characterization of the roles of CLF, SWN and CK2 in vernalization.

a, SWN expression in the indicated seedlings. Transcripts were quantified by qPCR and normalized to PP2A. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates. b, Phenotypes of the indicated lines grown in LDs. c, ChIP analysis of H3K27me3 enrichment at FLC upon 35-d cold exposure (vernalization) in the indicated seedlings. Levels of FLC fragments were quantified by qPCR and normalized to total input DNA. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. of three biological replicates. d, Flowering times of the indicated lines (grown in LDs) following vernalization (35-d cold treatment). e, Total leaf number at flowering of the transgenic lines of FRI clf-29 expressing CLFpro-CLF or CLFS182A. Plants were grown in LDs. f, FRI ck2b is partially vernalization-insensitive. FRI-Col and FRI ck2b seedlings were exposed to cold for 35 d. Dots in (d-f) represent individual measurements (n = 12), and middle lines for medians. The data in (c) and (d) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and two-tailed t test, respectively.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

List of genes misregulated in ck2b-quad.

Supplementary Table 2

List of H3K27me3-bearing genes upregulated in ck2b-quad.

Supplementary Table 3

List of primers used in this study.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 2

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 4

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 5

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed DNA gels.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Unprocessed western blots.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, X., Gao, Z., Gu, J. et al. CK2 kinase–PRC2 signalling regulates genome-wide H3K27 trimethylation and transduces prolonged cold exposure into epigenetic cold memory in plants. Nat. Plants 11, 1572–1590 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02054-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02054-1

This article is cited by

-

Phosphorylation powers plant Polycomb

Nature Plants (2025)

-

A pair of readers of histone H3K4 methylation recruit Polycomb repressive complex 2 to regulate photoperiodic flowering

Nature Communications (2025)