Abstract

The temperate seagrass Zostera marina is a foundational marine species that provides critical habitat in bays and estuaries throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Human activities and climatic events have necessitated Z. marina restoration, for which high transplant mortality rates call for innovative cross-disciplinary solutions. We identify a hybrid between Z. marina and Z. pacifica and explore the hybrid population as a tool for restoration from a genomic perspective. Among several habitat distinctions, Z. pacifica, an endemic to the Southern California Bight (West Coast, USA), is deeper-living and may encode resilience to low light, a leading factor of seagrass restoration failure. We construct a haplotype-resolved chromosome-scale genome assembly of the hybrid and several California Zostera accessions to describe the divergence between Z. marina and Z. pacifica and characterize the hybrid’s stage of maturity as an F1. Transcriptomes of Z. marina and the hybrid subjected to reduced light in an experimental mesocosm reveal divergent trends in photosynthesis, carbohydrate utilization and stress responses. Photoperiod regulation by Z. pacifica orthologues of key circadian clock genes, prominently LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL and WITH NO-LYSINE KINASEs, may drive this response. By describing the hybridization event using genomic and transcriptomic methods, this study presents preliminary evidence of low-light tolerance modulated by a labile circadian clock to motivate further ecological and functional studies of this hybrid as an experimental tool to access Z. pacifica genetics and its relevance to restoration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Seagrasses are marine plants that form the foundation of productive and ecologically valuable coastal ecosystems, promoting carbon-rich sediment deposition and retention1,2. Common eelgrass (Zostera marina) is the dominant seagrass in bays and estuaries along the West Coast of North America. In California, Z. marina inhabits estuaries and bays from intertidal to subtidal depths of 4 m, forming extensive and structurally complex habitats that provide critical ecosystem services such as cycling nutrients, improving water quality and stabilizing sediment to reduce coastal erosion3,4,5. As an ecosystem engineer, Zostera spp. provide nearshore habitat for juvenile fish and invertebrates, which is designated at the federal level as an essential fish habitat3. These vital systems are, however, experiencing large-scale losses from anthropogenic damage6. Dredging, boating activity and coastal development have reshaped the bays that eelgrass populates7. Changes in light, temperature and pollutants threaten the photosynthetic capacity of seagrasses and make them more prone to disease8,9.

Eutrophication-induced light limitation has emerged as a leading physiological cause of seagrass die-offs and restoration failures in California bay systems10. When subjected to transient light reduction in the marine environment, eelgrasses metabolize non-structural carbohydrates (NSCs) stored in the rhizome8,11,12,13,14. These NSCs consist of ~87% sucrose, lending Z. marina the nickname ‘marine sugarcane’ and providing the plant with a metabolic fallback plan when light falls below the light compensation point, at which carbon usage outstrips carbon assimilation11. This stress response has been demonstrated in the field and in aquaria and quantified with direct measurements of sucrose and starch as well as gene expression in the leaf11,12,13,14. Chronic and episodic light disturbance in eelgrass beds during their growth season reduces survivorship of eelgrass by depleting NSCs prior to overwintering8. Following the sequencing of the Z. marina genome, mechanistic study of the eelgrass low-light response has focused on NSC depletion, with genes identified for sucrose transport and stress signalling in the abscisic acid (ABA) pathway13,15,16. Yet, low-light tolerance varies seasonally and among populations in Zostera, and it remains to be seen how this resilience is genetically determined17.

The open-coast, offshore eelgrass Z. pacifica thrives at over triple the depth of Z. marina, making it an interesting case study in eelgrass low-light tolerance. Endemic to Southern California, Z. pacifica has a distinctive wide-leaf phenotype and principally inhabits sandy-sediment areas in exposed coastal shelf habitats and offshore islands in depths ranging from 6 to 22 m (refs. 18,19,20). Foundational studies of eelgrass light requirements agree that photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) of 3–3.8 mol m−2 d−1 is the minimum for Z. marina survivorship, while maximum growth takes place at 15–20 mol m−2 d−1 (refs. 21,22,23,24). Offshore Z. pacifica beds were found to grow at the low range of Zostera light requirements, averaging 3–4 mol m−2 d−1, with several transient and seasonal storm periods <1 mol m−2 d−1 (ref. 20). In addition to light quality, the Z. pacifica environment differs in temperature, pressure, dissolved oxygen content, sediment composition and wave activity from the estuaries and bays that Z. marina most commonly inhabits20.

Z. pacifica will hybridize with Z. marina in bays. Observed populations intermediate to Z. marina and Z. pacifica in San Diego Bay and Newport Bay suggest that hybridization is a consequence of Z. pacifica restoration transplants18. Our surveys located a persistent hybrid eelgrass bed in Mission Bay’s Mariner’s Basin in San Diego County at 2–4 m depth. At this site in October 2011, the US Army Corps of Engineers contracted eelgrass restoration to compensate for dredging impacts, a practice known as mitigation25,26. This project included a 1.39-acre mixed Z. marina and Z. pacifica transplant intended to address suspected light limitation, given the depth and bathymetry25. The mixed-species site successfully restored eelgrass density, though post-transplant surveys do not resolve whether success stemmed from site conditions, the presence of Z. pacifica or that of a hybrid26. Currently, the site hosts a robust mix of Z. marina and hybrid eelgrass.

The Mariner’s Basin eelgrass hybrid Z. marina × pacifica (hereafter referred to as the hybrid) represents a striking intermediate of natural and human-facilitated hybridization. Both species are native to the region, but they have high niche differentiation, making opportunities for introgression rare18,19. Other marine plants, including the euryhaline grass Ruppia and the seagrass Posidonia, have been shown to hybridize within their native ranges27,28. Interspecific hybridization increases genetic diversity and may produce hybrid vigour (heterosis) or adaptive radiation within the mosaic habitat pressures of a hybrid zone29,30. Anthropogenic threats to eelgrass necessitate creative solutions to restoration. With both deep- and shallow- living parentage, the hybrid may colonize intermediate depths in bay environments where Z. marina is ephemeral or absent, or may better withstand seasonal storms. Here we describe the hybridization using genomic and transcriptomic methods and present preliminary evidence of low-light tolerance to motivate further ecological and genetic studies of this hybrid.

Results

Identifying and sequencing a Zostera hybrid

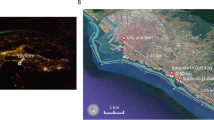

Z. pacifica’s wide leaves (Fig. 1a) contrast with the narrow leaves of Southern California Z. marina (Fig. 1b) and express as average leaf width in the hybrid (Fig. 1c). Physiologically, increased leaf width in eelgrass is produced by an increase in cell number rather than cell size (Extended Data Fig. 1a–c). In Mariner’s Basin, long, broad leaves distinguish hybrid eelgrass from the surrounding Z. marina. We collected nearby Z. marina (Zmar913) and Z. pacifica (Zpac1022) from the Matlahuayl State Marine Reserve in La Jolla (Fig. 1d,e). Through resequencing and counting K-mers, we estimated diploid genome sizes of 303 Mb for Zmar913, 249 Mb for Zpac1022 and 497 Mb for the hybrid, which displays much higher heterozygosity than either inbred (Extended Data Fig. 2a–c).

a–c, The wide-leaved Z. pacifica (Zpac1022-Sio2) (a) versus the narrow-leaved Southern California Z. marina (Zmar913-Mar3) (b) and the hybrid (Zmar912-Mar1) with intermediate leaf width (c). d, The hybrid and proximal Z. marina and Z. pacifica were collected in Mission Bay and La Jolla; for the sample metadata, see Supplementary Table 1. e, De novo genome assemblies for the hybrid, Z. marina and Z. pacifica resolve the hybrid as a diploid F1, with haplotype assemblies referenced as Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica.

We constructed a haplotype-resolved genome of the hybrid, along with Zmar913 and Zpac1022 and several Z. marina accessions from broader California. The hybrid assembly is highly contiguous (with pre-scaffolding contig N50s of 25.7 Mb for haplotype 1 (Hap1) and 16.1 Mb for Hap2) and has high per-base accuracy (assembly quality values (QV) = 42.6 and 43.4) (Supplementary Table 1). All assemblies, excluding a lower-quality sample from Humboldt, achieved Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) completeness of 98.1–98.4%, on par with the Z. marina reference genome at 98.4%. We annotated protein-coding genes in each haplotype of the hybrid, hereafter referred to as Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica, and these annotations achieved 95.8% and 96.0% BUSCO completeness, respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

By resequencing 12 hybrid individuals distributed throughout the site, we estimated that all hybrids displaying the characteristic wide leaf at the site are clones (Extended Data Fig. 2d). In the assembled hybrid genome, Hap1-marina aligns with Zmar913 and Hap2-pacifica with Zpac1022, with no conspicuous recombination of coding sequences (Fig. 1e). Hap1-marina shares 17,418 syntenic orthologues with Zmar913 (89.2% of on-scaffold genes), and Hap2-pacifica shares 17,304 with Zpac-1022 (90.7%) (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). There are no apparent rearrangements between homologous chromosomes indicative of a more mature hybrid (Extended Data Fig. 4a–l), outside of a highly repetitive centromere sequence in chromosome 4 (Extended Data Fig. 4g), which is more likely the result of misassembly or scaffolding inaccuracies in this repeat-rich area of the genome.

Z. pacifica speciation

The Southern California Bight endemic Z. pacifica is considered a distinct species from Z. marina given differences in their ecology. This speciation had not been corroborated with genomic evidence beyond microsatellite phylogenetics and plastid assembly, which found the Z. pacifica chloroplast to be 99.4% similar to that of Z. marina18,31. We estimated that Z. pacifica and Z. marina diverged from a common ancestor 1.17 million years ago (Ma) using synonymous substitution rates, and we derived a range of 1.15–3.04 Ma using phylogenetic reconstruction of seagrasses within the monocots from multisequence alignment (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Data 2).

To test whether Z. pacifica could alternatively be described as an ecotype, we compared the Z. pacifica genome to both geographically and phenotypically similar Z. marina. Leaf width is a plastic trait in Zostera and has led species distinctions to be later challenged by genetic evidence, as in the case of the wide-leaved Z. angustifolia in Europe32. The leaves of Z. pacifica are similar to those of higher-latitude Z. marina, beginning in Central and Northern California and extending northward along the coastline of North America. We collected Z. marina from across six distinct populations in California that display a wide-leaf phenotype and produced un-scaffolded de novo genome assemblies to produce a small pangenome (Fig. 2a,b)16. All Z. pacifica assemblies cluster distinctly from Z. marina across California, with no grouping of Z. pacifica with Z. marina by either geographical proximity (Z. pacifica with Southern California Z. marina) or the wide-leaf phenotype (Z. pacifica with Northern California Z. marina). This supports Z. pacifica speciation, as opposed to its being an ecotype displaying wider leaves in response to the darker and colder offshore environment.

a, California eelgrass collections from south to north with latitudes: Mission Bay (32.8° N), Elkhorn Slough (36.8° N), San Francisco Bay (37.9° N), Tomales Bay (38.2° N), Eel River Estuary (40.6° N), Humboldt Bay (40.7° N) and Crescent City Harbor (41.7° N). The collection locations are numbered as follows: (1) Zpac1022-Sio2, (2) Zpac1022-Sio1, (3) hybrid Hap2-pacifica, (4) hybrid Hap1-marina, (5) Zmar913-Mar3, (6) Zmar1017-Elk1, (7) Zmar1015-Sfb1, (8) Zmar1010-Tom3, (9) Zmar106-Eel1, (10) Zmar107-Hum1, (11) Zmar108-Cre1 and (12) Zmar668 Finland16. Zpac, Z. pacifica; Zmar, Z. marina. The accession names correspond to those in Supplementary Table 1 for metadata. b, Pangenome clustered by Jaccard similarity of genome-wide K-mers. For the bolded accessions, red denotes hybrid haploid assemblies, green the reference genome and black the chromosome-resolved Z. marina and Z. pacifica assemblies. c, Chromosome 1 (Chr. 1) protein-coding gene synteny. Zmar107-Hum1 (10) was omitted due to its lower-quality assembly. d, Hybrid Hap1-marina and hybrid Hap2-pacifica homologous chromosomes with gene and transposable element density. Transposable elements are grouped as follows: LTR-RTs (long terminal repeat retrotransposons); LINE/SINEs (long/short interspersed nuclear elements); TIRs (terminal inverted repeats). Paired chromosomes are scaled to reflect relative length in Mb.

Across the Z. marina accessions, we did note a persistent chromosome 1 inversion (Fig. 2c). While chromosomes 2–6 are syntenic across the pangenome, a chromosome 1 inversion appears in Southern and Central California accessions Zmar913-Mar3, hybrid Hap1-marina and Zmar1017-Elk1. Z. pacifica does not share this inversion, so we assume that Z. pacifica divergence predates it and that the inversion is not relevant to the speciation. However, this inversion does result in the hybrid possessing an internal inversion between otherwise homologous autosomes.

The Z. pacifica genome, assembled and scaffolded into chromosomes as Zpac1022 and hybrid Hap2-pacifica, is moderately smaller than that of Z. marina, which has more long terminal repeat retrotransposons in the centromere region (Fig. 2d). Centromere assembly in Zostera is highly variable across sequencing methods and plant samples, but the smaller genome size and reduced long-terminal-repeat-retrotransposon content of Z. pacifica remains consistent between Hap2-pacifica and Zpac1022 as compared with their Z. marina counterparts (Supplementary Table 1). While one un-scaffolded Z. pacifica assembly is an outlier (Zpac1022-Sio1), when we aligned the contigs to a scaffolded assembly, we found that the alignment matched the expected Z. pacifica genome size. Querying orthogroups constructed from 29 flowering plants (Supplementary Table 2), we found very few orthogroups with significant Z. pacifica gene expansion, and of these new genes that have informative annotations with Gene Ontology (GO) descriptions, nearly all appear to be untranscribed pseudogenes (Supplementary Table 3). This suggests that Z. pacifica divergence from Z. marina is not the result of conspicuous copy number expansion. Instead, evolving gene function and transcriptional regulation may drive ongoing adaptation, necessitating an experimental approach.

Z. marina and hybrid transcriptomes diverge under low-light conditions

We next explored whether the hybrid and its Z. pacifica genes demonstrate a low-light response distinct from that of Z. marina. We conducted a mesocosm growth experiment that challenged the hybrid and Z. marina to five days of shading, and we surveyed the transcriptome before, during and after perturbation (Fig. 3a–c). This light reduction was designed to mimic an oceanic storm or plankton bloom that creates semi-darkness at the benthos, persisting for days to weeks. At peak midday sunlight, the light-limited tank received ~37 μmol m−2 s−1 PAR; previous experimental studies in Zostera have simulated low-light stress using between 20 and 52.8 μmol m−2 s−1, yielding integrated daily light availability <1 mol m−2 d−1, which constitutes severe shading in the field8,13,14,33. Specifically, 3 mol m−2 d−1 has been defined as the threshold for sustained Z. marina growth21. Late-day sampling minimized ambient light intrusion and captured the plants’ transcriptomic response to either satiation or starvation of photosynthate.

a–c, The mesocosm, maintained outdoors with flow-through seawater, contained transplanted hybrid and Z. marina plants growing in a common garden. At the end of each sampling day before, during and after dark treatment, plants were removed, and leaf (L) and rhizome (R) tissues were collected for nucleotide extraction (a). The tank was fed with continuously flowing seawater at ambient ocean temperature, and air was bubbled in along the central axis. Experimental time points 1–4 and replicates a–c are shown (b). The experimental timeline contained an acclimation period, a light sample (t1) and two low-light samples at three days (t2) and five days (t3), after which the tank was uncovered, and a recovery time point (t4) was taken after a day. All tissue samples were collected just prior to sunset (c).

The mesocosm experiment presents a combination of hybrid and inbred (non-hybrid) Z. marina RNA-seq samples; we mapped all RNA-seq reads to the hybrid transcriptome, resulting in an average of 69.8% mapping for the hybrid samples and 70.2% for Z. marina (Supplementary Table 4). To eliminate haplotype cross-mapping prior to differential expression analysis, we used inbred Z. marina and Z. pacifica RNA-seq to calculate transcript mapping accuracy for every Hap1–Hap2 orthologous gene pair (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). After applying a 90% mapping accuracy cut-off, we carried through 13,952 1:1 orthologues to differential expression, representing 85.4% of the transcription observed in the hybrid throughout the study as a function of transcripts per million (Supplementary Data 3). With this set of orthologues, we observed that transcriptome-wide patterns of transcript relative abundance in the hybrid Hap1-marina haplotype are similar to those in inbred Z. marina (Fig. 4a). A subset of genes in the hybrid demonstrate expression bias between the parental haplotypes (Fig. 4b,c). Across all conditions, bias is higher in the leaf than in the rhizome but does not favour one subgenome. Biased expression is distributed evenly across the genome, suggesting genome-wide divergence of regulatory timing or strength within gene networks, rather than a single region experiencing selective pressure (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b).

a, In resolving the Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica transcriptomes, we observed that they occupy distinct space in a Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) dimensionality reduction of all experimental time points. The UMAP represents the expression of 1:1 orthologous gene pairs across all tissues and treatments. Hybrid Hap1-marina clusters with inbred Z. marina in both leaves and rhizomes. b,c, We extracted the genes differentially expressed between the hybrid haplotype 1:1 orthologues at each time point to derive gene counts for biased expression. In the leaf (b) and rhizome tissue (c), a subset of genes display expression bias to Hap1 or Hap2. The quantity of biased gene pairs varies over experimental time points and between tissues. Supplementary Data 3 presents the 1:1 orthologue pairs.

Within the set of 13,952 confident orthologue pairs, we carried out differential expression analysis of the plants in low light (t2 and t3) compared with full light (t1 and t4) (Supplementary Data 4) and identified enriched GO terms that describe divergent trends for the hybrid and inbred Z. marina. By separating the hybrid haplotypes in this analysis, we could directly compare the Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica subgenomes with Z. marina in terms of gene count. A potential weakness of this approach is that Z. marina as a diploid may demonstrate an amplified differential expression signal when orthologous genes on both haplotypes are summed, but we did not observe this and in fact found fewer differentially expressed genes in Z. marina. Of the two tissue types, the leaf experienced greater up- and downregulation of genes in response to low light intensity, with the hybrid leaf upregulating 2,445 genes on Hap1 and 2,481 on Hap2, and the Z. marina leaf upregulating 1,959, whereas the hybrid rhizome upregulated 1,073 and 1,062 genes and the Z. marina rhizome 334 (Fig. 5a,b).

a,b, Counts of differentially expressed (DE) genes in the leaf (a) and rhizome (b) for hybrid Hap1-marina, Hap2-pacifica and Z. marina, with positive numbers indicating upregulation in the shade, and negative numbers indicating downregulation. Shaded time points t2 and t3 in combination were compared to full-light time points t1 and t4 to extract DE genes. c, GO category enrichment analysis of all up-regulated (+) and downregulated (−) DE genes, with all points plotted exceeding a significance cut-off of FDR < 0.05. GO terms are presented with descriptive names and grouped into thematic groups. Exhaustive results of the GO enrichment analysis, including GO ID numbers, are presented in Supplementary Data 5.

We extracted enriched GO groupings from the up- and downregulated gene sets (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Data 5). Light-sensing genes (A) experience up- and downregulation for both Z. marina and the hybrid, though the hybrid’s response to red or far-red light and photoperiodism is significant compared with that of Z. marina. Blue light sensing is downregulated in both plants. A divergent trend emerges in primary metabolism and carbohydrate utilization (B), as the plants respond to low photosynthate. At this late-day collection, the hybrid has upregulated photosynthesis (enrichment, 4.4 (Hap1) and 4.7 (Hap2); false discovery rate (FDR), <0.0001). Additionally, genes for chlorophyll biosynthesis are highly enriched in the hybrid leaf (enrichment, 8.2; FDR < 0.0001) and not in Z. marina. Instead, we observed Z. marina upregulating sucrose catabolism in the rhizome (enrichment, 24.3; FDR < 0.05). The hybrid also upregulates sucrose catabolism, but enrichment is statistically significant only in Z. marina due to lower differentially expressed gene counts. From this, we determined that both Z. marina and the hybrid catabolize some rhizome sugars during shade stress, but the hybrid additionally maintains photosystem proteins and chlorophylls for photosynthesis, suggesting that photosynthesis continues despite low PAR. For stress response (C), both Z. marina and the hybrid up- and downregulate the leaf’s response to radical oxygen species. Otherwise, their stress responses differ, with the hybrid upregulating trehalose metabolism and the regulation of the immune response and reproductive phase shift in the leaf, and the Z. marina leaf upregulating callose deposition, response to anoxia and photomorphogenesis. Lastly, growth and development genes (D) demonstrate both up- and downregulation in the hybrid and Z. marina, indicating a mix of turning on and turning off pathways due to light reduction.

Low-light photosynthesis in the hybrid leaf

While Z. marina responded to the experimental shade conditions by metabolizing its stored rhizome sugars, the hybrid additionally upregulated chlorophyll biosynthesis and late-day photosynthesis, suggesting that a shift in circadian-clock- regulated transcription drives the continued maintenance of photosystems and implied production of photosynthate. Light-harvesting and chlorophyll biosynthesis genes show concerted overexpression across both the Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica orthologues during the low-light time points t2 (three days of shade) and t3 (five days of shade) (Fig. 6a,b). Light-harvesting components including several orthologues of LIGHT HARVESTING COMPLEX A and B (LHCA and LHCB), LOW QUANTUM YIELD OF PHOTOSYSTEM II 1 (LQY1) and PSB27, encoding a Photosystem II family protein, are highly expressed at t2 and have heterogenous expression at t3 (refs. 34,35,36). Other light-harvesting components—FTSH2, encoding an ATP-dependent zinc metalloprotease, and DEG5, encoding an ATP-independent serine protease, both involved in PSII maintenance and recycling—show their highest expression at t3 (refs. 37,38). Despite strong upregulation of light-harvesting complex transcripts, plastid-to-nuclear read ratios showed no increase in chloroplast number under shade (Extended Data Fig. 8), suggesting that the hybrid copes with low light by upregulating LHCs and photosystem-maintenance genes to repair or replace photosystem components rather than by increasing chloroplast density.

a–c, Hybrid genes associated with the enriched GO categories of GO:0009765 (photosynthesis, light harvesting) (a), GO:0015995 (chlorophyll biosynthetic process) (b) and GO:0009648 (photoperiodism) (c), visualized with normalized log fold change across the experimental time points for the hybrid leaf experiencing low-light stress. The orange box highlights Hap2-pacifica biased overexpression in the photoperiodism group. Gene identity was derived from gene annotations and A. thaliana/O. sativa orthologues. Experimental replicates are clustered on the horizontal axis by transcriptome (Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica) and time point (t1 (full light), t2 and t3 (low light), and t4 (full-light recovery)). Gene positional information (for example, chr04.g119180) is given for the Hap1-marina orthologue in cases where multiple gene copies are expressed. The log1p values plotted represent normalized expression values, log-transformed for visualization.

The key light-harvesting pigments chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b are biosynthesized from glutamate and share a porphyrin scaffold intermediate, protoporphyrin IX, with haem biosynthesis39,40. Several key biosynthetic components of chlorophyll biosynthesis are upregulated both upstream and downstream of protoporphyrin IX, indicating concerted upregulation before and after the haem junction. These include the early-pathway HEMA and HEMC, which encode the biosynthesis genes for glutamyl-tRNA reductase (GluTR) and porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD), and the down-pathway CHLI, encoding a subunit of magnesium-protoporphyrin chelatase, as well as the genes for magnesium protoporphyrin methyltransferase (CHLM) and 3,8-divinyl chlorophyllide a 8-vinyl reductase (DVR)40. Additionally, CAO, encoding chlorophyllide a oxygenase, catalyses the interconversion of chlorophyllide a and chlorophyllide b, driving chlorophyll b biosynthesis41. While most components are overexpressed on both haplotypes, one HEMA homologue demonstrates transcription bias to Hap1-marina, and HEMC, which shows a tandem duplication on chromosome 5, is biased to Hap2-pacifica for two copies.

Though we observed relatively balanced overexpression of photosynthesis and pigment biosynthesis genes across parental 1:1 orthologues, several photoperiod genes demonstrate haplotype bias (Fig. 6c). In plants, photoperiodism describes the ability to respond to day length by modulating time-of-day-regulated functions such as photosynthesis and flowering, and indeed in this GO category we observed several circadian clock components and signalling proteins. The core circadian clock transcription factor gene LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY) is upregulated in low light on both haplotypes but is biased to Hap2-pacifica42. LHY transcription oscillates with morning-specific time-of-day-specific expression, when it binds the promoters of light-harvesting complex encoding genes to promote transcription and phytochrome signalling42,43. LHY transcript oscillation has been observed in Z. marina to peak in the pre-dawn under ideal light conditions, but we measured transcript upregulation in the late-day hybrid subjected to low light12. Abiotic cues reach the circadian clock through signalling pathways; ABA signalling has previously been implicated in the Zostera low-light stress response, and we note two copies of an mRNA binding protein encoding gene, ABH1, involved in post-transcriptional regulation of ABA signalling with overexpression strongly biased to Hap2-pacifica13,44. WITH NO-LYSINE KINASEs (WNKs) are protein kinases implicated in integrating abiotic stress signals into the timing of the circadian clock, evidenced in monocots such as rice (Oryza sativa) and soy (Glycine max)45,46,47. Three WNKs are overexpressed in the low-light hybrid, including a chromosome 4 WNK1 homologue unique to temperate seagrasses that only shows low-light differential expression of the Hap2-pacifica orthologue, indicative of neofunctionalization. The WNKs are also involved with ABA signalling, but these interactions are not fully elucidated46. WNK1 may also act on flowering time genes (FTs) such as TIME OF FLOWERING 1 (TFL1), which we observed to be upregulated in this GO category with heterogeneity among replicates47. Lesser-studied genes implicated in GO:photoperiodism include the zinc-finger homodomain transcription factor HB31, involved in floral phenotype, and the serine/threonine protein kinase LRK10L3, each of which has multiple copies in the hybrid, demonstrating haplotype bias48,49.

In addition to LHY, we observed other circadian clock transcription factors to be upregulated in low light, particularly those comprising the morning loop that promotes photosynthesis, identified using homology to Arabidopsis thaliana and O. sativa (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 4)50. Several of these genes show haplotype bias (Extended Data Fig. 9a–l). The PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATORs (PRRs) are activated by LHY and expressed in the morning and midday, and they have three orthologues in Zostera, two of which are expressed and are upregulated across both haplotypes of the hybrid42,43. The classic repressor of LHY and core constituent of the evening loop, TIMING OF CAB EXPRESSION 1 / PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR 1 (TOC1/PRR1), is highly conserved in land plants but not present in Zostera16. In the evening complex, LUX ARRHYHTHMO (LUX) is upregulated, but the differential expression of EARLY FLOWERING 3 or 4 (ELF3/4) is not significant. Along with LHY, the ELF3/4 and CCA1 HIKING EXPEDITION (CHE) genes demonstrate haplotype bias across all time points, with LHY and one CHE biased to Hap2-pacifica, and the other CHE and ELF biased to Hap1-marina.

a, Using gene homology to Arabidopsis, we extracted the clock genes embedded in cycles of activation and repression, with the morning loop promoting photosynthesis and the evening loop promoting respiration. The regulatory relationships of circadian clock components are represented in a network with connecting lines ending in arrows indicating activation and those ending in T’s indicating repression. The up and down arrows indicate differential expression, with each arrow indicating a gene copy and its direction corresponding to up- or downregulation. The loss of TOC1 in Zostera is represented as a greying out of those regulatory connections. Gene information, including Ka/Ks values and log fold changes, are presented in Supplementary Table 5. b, Observations made in this late-afternoon sampling procedure support a theory that adaptive Zostera circadian clock regulation shifts periodicity under low-light conditions.

The majority of these circadian genes are experiencing purifying selection, with the ratio of protein sequence synonymous to non-synonymous substitution rates (Ka/Ks) <1 between hybrid Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica orthologues. However, the upregulated LHY, LUX, WNK5 and TFL1 are experiencing positive selection, with Ka/Ks values of 1.05, 1.26, 1.22 and 1.16, respectively (Supplementary Table 5). Our RNA-seq collections represent a single time point on the oscillator. Our results therefore support a theory of shifting day length that will require testing in a time course in the future (Fig. 7b).

Discussion

Through whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and assembly of resolved parental chromosomes, we have described the landscape of a Zostera hybrid genome, which is a first-generation F1 homoploid with Z. marina and Z. pacifica parental haplotypes that have yet to recombine. The haplotype-resolved hybrid transcriptome enabled the comparison of Z. marina and Z. pacifica gene orthologues under shade conditions. The hybrid demonstrated a divergent low-light response from inbred Z. marina, upregulating photosystem and chlorophyll biosynthesis; this differential expression implies the continued creation of photosynthate at a light intensity above the light compensation point, or the minimum light intensity for carbon assimilation, indicative of shade tolerance (though direct measurements of rhizome sucrose are absent from this study).

The observation of late-day photosynthesis gene upregulation in the hybrid may be related to photoperiod control, as we observed differential expression of circadian clock transcription factors, WNK protein kinases and ABA signalling proteins. Under shade conditions, we observed the morning loop of the circadian oscillator to be upregulated in the evening. Light reduction is known to lengthen the circadian period—for example, the phase of LHY is advanced by two hours in shaded tomato, and hybrid haplotypes have been shown decouple the oscillation of core clock genes51,52. LHY demonstrated expression bias to Hap2-pacifica over the course of our experiment, suggesting that the Z. pacifica and Z. marina clocks may have asynchronous daily oscillations.

Zostera species possess a single LHY homologue per haplotype, while some plant lineages (including the Brassicaceae, with the model plant Arabidopsis) have two, performing semi-redundant tasks16,42. Ma et al. hypothesized that the reduction of clock genes in Zostera and other aquatic plants is due to water availability reducing the need for such strict timing of metabolic tasks16. Building on this, we posit that shade tolerance in temperate seagrasses, exemplified by the deep-living Z. pacifica, favours a reduced clock that is flexible to shifting periodicity. These plants face a highly variable light environment; storms or plankton blooms may transiently drop PAR to near the light compensation point for days to weeks, while seasonal shifts set longer-term constraints on growth, necessitating the retention of clock-controlled processes such as flowering. This lifestyle favours a plant with a malleable definition of day length to take advantage of all photosynthetically available light during short-timescale low-light events, while retaining clock-regulated transcription given ideal light conditions. The circadian clock in Zostera deserves deeper study directed towards potential neofunctionalization of these conserved clock genes across the metabolic day as important players in low-light resilience.

The Z. marina × pacifica hybridization event in Mariner’s Basin was a consequence of mitigation management. Yet, this population may be useful in restoration if advantageous traits such as low-light tolerance or high growth rate from heterosis are demonstrated in the field. Ecological studies in the mixed meadow could compare primary productivity and bed expansion/contraction across multiple seasons to determine whether the hybrid is becoming a competitive dominant at the site. Longer-term in situ shading experiments or experimental small-scale outplanting of hybrid and Z. marina plants in a light-challenged site, coupled with continuous PAR measurements, could explore survivorship and growth rate. Additionally, the vital question of sexual viability remains. The dominant hybrid clone appears to be first-generation, or F1, which aligns with the recency of the Z. pacifica transplant at the site. Though we have yet to observe clear F2 progeny through exploratory genotyping, the hybrid can produce flowers. After no observed flowering in 2023–2024, in summer 2025, the hybrid produced reproductive tissue, flowers and seeds, indicating the potential for outcrossing. Eelgrass can produce extensive clones, though these are less common in Southern California than genotypically mixed beds that rely on some amount of sexual reproduction18. It remains unclear whether the prevalence of the clone is due to low sexual viability or to having a competitive genotype suited to its environment. Discovering whether the hybrid produces viable seeds, and the frequency of these flowering events moving forward, is a priority for understanding its ecological impact. Dependent on these traits, the hybrid could expand the range of suitable habitat for eelgrass restoration, allowing outplanting in areas impacted by lower PAR from depth, seasonal events or poor water clarity.

Light limitation will continue to hamper Z. marina restoration efforts as eutrophication, dredging and sea level rise contribute to reduced PAR for bay and estuarine eelgrass. Expanding eelgrass restoration to include offshore Z. pacifica could benefit coastal ecosystems and carbon capture in Southern California but requires further elucidation of Z. pacifica growth parameters for selecting suitable restoration sites, which the hybrid may enable34. Z. marina bay and estuarine systems and Z. pacifica open coast ecosystems are differentiated by a host of biophysical factors, even as their genomes appear highly similar in gene content and synteny. For comparative studies, the hybrid offers a clonal accession containing both genomes that is suitable for ex situ growth experiments. We encourage future studies of the hybrid directed towards these experimental applications, as well as ecological surveys of hybrid growth rates, reproduction and low-light tolerance in the field.

Methods

Plant collection for nucleotide extraction

For all plants subjected to WGS, complete sample metadata (locations throughout California and dates of collection) are presented in Supplementary Table 1. All Z. marina for WGS were collected by snorkelling from these various locations, while Z. pacifica for WGS and RNA-seq was collected in the Matlahuayl SMR in San Diego, California, USA, via SCUBA. Using gloved hands, whole seagrass ramets (root, rhizome and leaves) were carefully cut from the clonal rhizome. On shore or boat, each specimen was briefly cleaned in seawater of epiphytes and sediment, separated into root, rhizome and leaf tissue samples, and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA, we used the leaf tissue within the sheath, down to the first node of the rhizome. Zostera plants were collected and sacrificed or maintained in seawater tanks under California Department of Fish and Wildlife scientific collection permit no. S-210200011-21023-001.

Plant collection for transplant

In September 2023, 12 hybrid and 12 Z. marina were collected from Mission Bay at the same depth (2–3 m), bagged and transported in seawater in a chilled cooler. The transplants all contained two to four ramets and appeared healthy (that is, substantial new leaf growth, young roots and minimal epiphytes). In parallel with the plant collection, we collected several pounds of sediment from the eelgrass beds to recreate the rhizosphere and sediment microbiome in the eelgrass beds to aid plant acclimation and mixed this with more accessible sediment from the shoreline to increase the sediment depth in the tank to ~10 cm. A turquoise outdoor aquaculture tub tank (base dimensions 0.5 m by 1.1 m) at Scripps Institution of Oceanography was outfitted with flowing seawater at ambient ocean temperature and air bubblers down the centre of its long axis and shaded by a mesh cover to reduce tank overheating and protect the tank from birds. Hybrid and Z. marina plants were planted in a common garden in the tank. Figure 3 provides a schematic of the tank and the experimental design. The plants were acclimated for 30 days before exposure to experimental conditions. During this acclimation period, the tank and plants were cleaned of algal epiphytes and grazers, and mature leaves were trimmed to remove necrotic tissue. Phyllaplysia slugs were allowed to remain in the tank to reduce algal epiphytes. Transplant was deemed successful when we observed new leaf growth of existing ramets, as well as several juvenile ramets appearing, around 20 days after transplant for both genotypes. A prior validation of these growth conditions was conducted with a non-experimental seagrass tank that supported both hybrid and Z. marina eelgrass for several months.

Growth experiment

We constructed a shade box from heavy-duty white cardboard on a wood frame to entirely surround the tank. At peak sunlight, the box reduced available light to the plants to an average of 37 μmol m−2 s−1 (~95% reduction) across the experiment days, measured at noon each day using an Odyssey Xtreem PAR logger (OXLPAR), calibrated by an Apogee MQ-510 quantum meter. Due to an error with the PAR logger, PAR measurements at other times of day were not collected; we therefore infer a daily integrated PAR of <1 mol m−2 d−1 not from direct measurement and integration but from comparison to other studies in Zostera spp.13,14,21. The water temperature in the tank averaged 17.9 °C and reached a minimum of 16.7 °C on the fourth day of the experiment, which coincided with a swell bringing colder sea surface temperatures. The experiment consisted of four collection time points, all carried out at sunset: t1 before shade treatment (control), t2 at day 3 of shade treatment, t3 at day 5 of shade treatment and t4 the day after the box was removed. Each sampling took three plants of each genotype as biological replicates, and the youngest ramet was sampled for leaf and rhizome tissue (excluding juvenile ramets <10 cm tall). To normalize by growth stage across all samples, leaf lengths as a proxy for age were kept relatively consistent, with hybrid leaves 22.1 cm ± 5.7 cm and Z. marina 15.8 cm ± 5.8 cm. Rhizomes were sampled at the first internode of the same ramet. To reduce sampling bias of microenvironments within the tank at any given time point (for example, closest to the seawater outflow or next to the tank wall), replicates a–c for each time point were distributed throughout the tank. All leaves were cleaned of epiphytes (minimal), roots and sediment were removed from the rhizomes, and the samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and transported on dry ice. Each plant was processed separately, and the box was closed between each sampling.

DNA extraction

For the hybrid (Zmar912-Mar1), Zpac1022-Sio1, Zmar1010-Tom3, Zmar1017-Elk1, Zmar108-Cre1, Zmar106-Eel1 and Zmar1015-Sfb1, HMW DNA was extracted using an Oxford Nanopore Community protocol for HMW DNA, which uses components of the QIAGEN Blood and Cell Culture DNA Midi Kit (13343) (https://community.nanoporetech.com/extraction_method_groups/plant-leaf-gDNA). We followed this protocol with two modifications: a 20-ml lysis buffer ‘half reaction’ to eliminate sample splitting, and a three-hour final isopropanol incubation.

For Zmar913-Mar3, Zpac1022-Sio2 and Zmar107-Hum1, HMW DNA was extracted using the Circulomics Nanobind Plant Nuclei Big DNA Kit (NB-900-801-01), following the UHMW DNA Extraction protocol from isolated plant nuclei (EXT-PLH-002). To isolate nuclei, we used the following procedure. After 10 min of grinding in liquid nitrogen, ~1.5 g of leaf powder was resuspended in IBTB buffer (15 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA, 130 mM KCL, 20 mM NaCL, 8% PVP-10, 1.15 mM spermine, 1.15 mM sperimidine, 0.1% Triton-X 100, 7.5% 2-mercaptoethanol (BME)). Before the spermine and spermidine were added, the pH was adjusted to 9.5, and the Triton-X and BME were added immediately before use. The following isolation steps were performed on ice: 100-μm and 40-μm cell strainers filtered out cell debris and organelles lysed by adding 0.25% Triton-X 100. Residual cell debris were removed via 1 min of centrifugation at 60 g before the nuclei were pelleted at 2,500 g for 10 min, followed by washes in IBTB. Nuclei containing traces of green plastid material were then carried into the Circulomics protocol with no alterations. For seagrass HMW samples, we recommend the Nanopore protocol, as used for the hybrid, which carries out direct lysis and extraction on young plant tissue; the nuclei isolation method represents an older workflow.

DNA intended for short read sequencing was extracted using a Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (96106). An MP Biomedicals FastPrep-96 bead beater (6010500) was used for tissue homogenization; <100 mg of all samples were placed in MP Biomedicals 2-ml steel bead beating tubes (6925050) on dry ice and beaten for 90 seconds at maximum speed with dry ice before we proceeded to the lysis step.

All DNA was quality assessed using a ThermoFisher Nanodrop 2000c (8353-30-0011) and a Qubit Fluorometer (Q33238) with the Broad Range assay (Q33231). Fragment lengths of all HMW DNA samples were measured using an Agilent 4150 Tapestation (G2992AA) with a Genomic DNA ScreenTape (5067-5365).

RNA extraction

The mesocosm experiment yielded leaf and rhizome tissue for RNA extraction, and several wild-collected Z. pacifica tissue samples were included to aid transcript identification. We present RNA integrity and yields for all tank experiment samples in Supplementary Table 3. An MP Biomedicals FastPrep-96 bead beater (6010500) was used for tissue homogenization; <100 mg of all samples were placed in MP Biomedicals 2-ml steel bead beating tubes (6925050) on dry ice and beaten for 90 seconds at maximum speed with dry ice before we proceeded to lysis. We used a Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (74904) with no modifications. All RNA samples were treated with ThermoFisher Invitrogen TURBO DNase and DNase inactivation reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (AM1907). Rhizome samples from Z. marina time points t3 and t4 yielded negligible RNA, despite several repeated extractions, leading to loss of a replicate at t3 and t4 for Z. marina rhizome, and one replicate lost at t4 for Z. marina leaf (Supplementary Table 4). RNA samples were quantified and quality assessed using an Agilent 4150 Tapestation (G2992AA) with RNA ScreenTape (5067-5576).

Long read library preparation and sequencing

Coverage statistics of sequencing reads from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) for individual assemblies are presented in Supplementary Table 1. For Zmar913-Mar3, Zpac1022-Sio2 and Zmar107-Hum1, samples for ONT were prepped for sequencing via ligation (SQK-LSK110) using the Long Fragment Buffer included in the kit, and immediately loaded onto a PromethION flow cell (v.9.4.1) and run on the PromethION running Guppy (v.5.0.12) for base calling and visualization with MinKNOW (v.21.05.20). For Zmar913-Mar3, a 250-ng library prep yielded 13,270,000 reads, 62.59 Gb passed bases and a sequencing N50 of 21.89 kb. A 266-ng Zpac1022-Sio2 library prep yielded 14,940,000 reads, 94.12 Gb passed bases and a sequencing N50 of 16.21 kb.

The hybrid Zmar912-Mar1 was sequenced on a PacBio Sequel II, with SMRTbell 3.0 library prep (102-141-700). A single SMRT cell yielded 1,550,000 HiFi reads (QV > Q20) with a mean length of 16.54 kb, resulting in a 25.58-Gb yield with a mean QV of Q31. Zpac1022-Sio1, Zmar1010-Tom3, Zmar1017-Elk1, Zmar108-Cre1, Zmar106-Eel1 and Zmar1015-Sfb1 were sequenced on a PacBio Revio with SMRTbell library prep for Revio (103-381-200) and barcoded in groups of two or three per SMRT cell, with the individual SMRT cells producing 86.40–93.70 Gb each.

Short read library preparation and sequencing

WGS libraries for the hybrid clonal genotyping sample set as well as for the hybrid genome assembly were prepared using an Illumina Nextera Flex (20018706). The WSG libraries for samples Zmar913-Mar3 and Zpac1022-Sio2 were prepared via ThermoFisher Collibri ES DNA library prep for Illumina (A38605024). The cDNA library preps of all RNA-seq samples were prepared via Illumina Stranded mRNA library prep (20040534), which includes a Poly-A selection. For Zmar913-Mar3, Zpac1022-Sio2 and Zmar912-Mar1, high-throughput chromatin conformation capture (Hi-C) libraries were prepared with a Phase Genomics Proximo Hi-C kit for plant tissue (KT3045) with protocol v.4.0. All library preps were completed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with no protocol modifications. The hybrid Zmar912-Mar1 required a repeat library prep and sequencing to achieve quality scaffolding, and the Hi-C coverage in Supplementary Table 1 reflects a summed yield. Hi-C and non-hybrid WGS libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq500, and cDNA libraries and hybrid WGS libraries on a NovaseqX, all with the PE150 run configuration. Coverage statistics of sequencing reads from Illumina WGS libraries and Hi-C libraries for individual assemblies are presented in Supplementary Table 1. RNA-seq mapping rates and yields from each Illumina cDNA library are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

Genome assembly

PacBio HiFi, ONT and Illumina HiC reads were incorporated into the assembly of the Zmar912-Mar1 hybrid with HiFiasm v.0.19.8 (https://github.com/chhylp123/hifiasm)53. ONT reads longer than 30 kb and with a mean quality greater than Q10 were used as the ‘ul’ input into HiFiasm, while ONT reads shorter than 30 kb with a mean quality greater than Q20 were combined with the PacBio reads as HiFi input. ONT read filtering was accomplished using fastq-filter v.0.3.0. The HiC reads were included via the ‘hic1’ and ‘hic2’ flags to improve assembly phasing. After assembly, the contigs were screened for contamination using v.0.5.0 of NCBI’s Foreign Contamination Screening–GX workflow (https://github.com/ncbi/fcs)54. PacBio HiFi reads from Zpac1022-Sio1, Zmar1010-Tom3, Zmar1017-Elk1, Zmar108-Cre1, Zmar106-Eel1 and Zmar1015-Sfb1 were assembled and filtered with the same versions of HiFiasm and Foreign Contamination Screening–GX as the hybrid.

Prior to assembly, the longest ONT reads from Zmar913-Mar3 and Zpac1022-Sio2 were sub-sampled to produce 13.5 Gb of data per sample, reducing read coverage to around 60×. ONT reads from the Zmar913-Mar3, Zpac1022-Sio2 and Zmar107-Hum1 samples were then assembled with Flye v.2.9 (https://github.com/mikolmogorov/Flye)55. The contigs for these samples were then polished with three rounds of Racon v.1.4.20 (https://github.com/isovic/racon)56. An additional three rounds of Pilon v.1.24 (https://github.com/broadinstitute/pilon) polishing were then used for Zmar913-Mar3 and Zpac1022-Sio2 with short-read data57.

Genome scaffolding and resolving chromosomes in the hybrid

Illumina HiC reads were mapped to both haplotypes of the Zmar912-Mar1 hybrid using bwa (https://github.com/lh3/bwa) v.0.7.17-r1188 and samblaster v.0.1.26 (https://github.com/GregoryFaust/samblaster)58,59. Filtering of the mapped reads, followed by ordering and orientation of the contigs, was accomplished with the HapHiC v.1.0.3 pipeline (https://github.com/zengxiaofei/HapHiC)60. HiC reads from the Zmar913-Mar3 and Zpac1022-Sio2 samples were mapped to their respective contigs using the Juicer v.1.6.2 pipeline (https://github.com/aidenlab/juicer) followed by ordering and orientation via 3D-DNA v.180922 (https://github.com/aidenlab/3d-dna)61,62,63. All scaffolded assemblies then underwent manual curation using Juicebox v.1.11.08 (https://github.com/aidenlab/Juicebox)61.

Assessing genome content

Genome assembly completeness was assessed using BUSCO v.5.8.2 (https://gitlab.com/ezlab/busco) with the viridiplantae_odb10 database64. To estimate genome sizes, we counted K-mers derived from Illumina short reads using Jellyfish (https://github.com/gmarcais/Jellyfish)65. The clonality of the hybrid was also assessed using K-mers within a dataset of 12 samples. Meryl v.1.4.1 (https://github.com/marbl/meryl) with meryl_dif_history computed shared and unique K-mers for all representative sample pairs66. We annotated gene encoding sequences in the scaffolded assemblies (Zmar913-Mar3, Zpac1022-Sio2 and both haplotypes of hybrid Zmar912-Mar1) using gene models produced by Helixer v.0.3.3 (https://github.com/weberlab-hhu/Helixer), a deep neural network gene prediction tool67. Using the land_plant database, we found that Helixer performed better for BUSCO completeness metrics than cDNA-informed gene calls. For long terminal repeat/transposable element content, we annotated repeats using EDTA v.2.2.0 (https://github.com/oushujun/EDTA) running RepeatModeler (sensitive), excluding un-scaffolded contigs from this analysis68.

Speciation divergence time estimation and phylogenetic reconstruction

OrthoFinder v.3.0 (https://github.com/davidemms/OrthoFinder) used 104 orthogroups representing conserved single-copy genes to construct a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and species tree for the plant proteomes specified in Supplementary Table 1 (refs. 16,17,69,70,71,72,73). From this MSA and tree topology, we extracted all monocot species, excluding Triticum aestivum due to alignment gaps, and for Zostera spp. included only Zostera_marina_913 and Zostera_pacifica_1022 to reduce redundancy. MCMCtree within PAML v.4.9 (https://github.com/abacus-gene/paml) was used for phylogenetic reconstruction with this protein MSA as input and calibration points of 42–52 Ma for Oryza sativa / Brachypodium distachion divergence, 118–129 Ma for Spirodela polyrhiza / Z. marina and 130–140 Ma for aquatic monocots, with hard bounds on tail probabilities16,74.

The resulting input species tree with 21 species was as follows: (Acorus_americanus, (((Colocasia_esculenta, (Spirodela_polyrhiza, Lemna_minor)), (Thalassia_testudinum, ((Cymodocea_nodosa, Posidonia_oceanica), (Potamogeton_acutifolius, (Phyllospadix_torreyi, (Zostera_marina_913, Zostera_pacifica_1022))))))‘B(1.18,1.29,1e-300,1e-300)’, (Dioscorea_dumetorum, ((Ananas_cosmosus, (((Zea_mays, Sorghum_bicolor), Oropetium_thomaeum), (Oryza_sativa, (Phyllostachys_edulis, Brachypodium_distachyon))‘B(0.42,0.52,1e-300,1e-300)’)), (Asparagus_officinalis, Phalaenopsis_equestris))))‘B(1.3,1.4,1e-300,1e-300)’).

MCMCtree was run with independent rates using an approximate likelihood calculation. Root age was constrained to <200 Ma, and the rate of 6.5 × 10−9 substitutions per site from Oryza sativa informed an rgene_gamma of 65 100, where 65/100 = 0.65 substitutions per site per time unit of 100 Ma (ref. 75). After a burn-in of 10,000, 200,000 samples were taken with a sampling frequency of 10 for a total of 20,000 samples, and a second independent run with the same parameters proved model convergence with an R2 of 0.9998. Acceptance proportions of node ages remained stable throughout both runs between 0.20 and 0.40, indicating sufficient burn-in and adequate priors. All node ages fall within the 95% confidence intervals of the phylogeny reported in Ma et al.16.

In parallel, we calculated the divergence time between Z. marina and Z. pacifica using genome-wide Ka/Ks ratios and the same 6.5 × 10−9 synonymous substitution rate from O. sativa 75. MCscan Python within JCVI-toolkit v.1.5.3 (https://github.com/tanghaibao/jcvi) was used to compute syntenic orthologues from gene annotation coding sequences and proteins, and these gene pairs were supplied to gKaKs v.1.3.0, a pipeline validated on closely related species76,77.

Pangenome

All Z. marina and Z. pacifica assemblies derived in this study, as well as the v.3.1 Z. marina reference genome (Zmar668), were fed into PanKmer (https://salk-tm.gitlab.io/pankmer/) genome-coverage to create a Zostera pangenome K-mer index16,78. Individual indices were produced for Z. marina and Z. pacifica genomes only, and these species-specific K-mer pools were used to compute percentage K-mer conservation across all hybrid chromosomes via the anchorplot functionality.

To plot chromosome 1 synteny (Fig. 2c) across the pangenome, we first scaffolded the draft genomes using our chromosome-resolved assemblies. Scaffolding used RagTag v.2.1.0 (https://github.com/malonge/RagTag) with the Zmar913-Mar3 assembly as a reference for all Z. marina and Zpac1022-Sio2 for all Z. pacifica79. Helixer v.0.3.2 produced gene models for the scaffolded assemblies, and we aligned chromosome 1 annotations with GENESPACE v.1.3.1 (https://github.com/jtlovell/GENESPACE) with the default parameters, specifying Zmar668 as the reference genome and a custom genome order for visualization using plot_riparian80.

We carried out all-by-all Ka/Ks calculations of the California Zostera assemblies using MCscan Python with the JCVI toolkit v.0.9.14 (ref. 77). First syntenic orthologues were identified between the coding sequences of two genomes (jcvi.compara.catalog ortholog–no_strip_names). Next, the Ka and Ks values were estimated (jcvi.apps.ks calc–msa=muscle). The genomes described here were run all-by-all to determine all pairwise Ka/Ks values, and the Yang–Nielson estimation was used for the reported data81.

RNA-seq transcript mapping

The hybrid transcriptome used for RNA-seq mapping was derived from the Helixer-generated protein-coding gene annotations of the Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica assemblies, concatenated. Raw Illumina RNA-seq reads for all mesocosm experimental samples and the wild-collected Z. pacifica were mapped to the hybrid transcriptome using Salmon v.1.10.1 (https://github.com/COMBINE-lab/salmon)82. Next, we derived mapping accuracy for all genes with orthologues between Z. marina and Z. pacifica. We ran OrthoFinder v.3.0 on a set of 29 plant proteomes presented in Supplementary Table 1, including hybrid Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica, and extracted all one-to-one gene pairs, excluding one-to-many pairings69. A set of 22 Z. marina RNA-seq samples (all mesocosm samples) and 7 Z. pacifica samples were used to derive mapping accuracy for each gene pair. We defined mapping accuracy as the percentage of expected mapping (Z. marina transcript to Hap1-marina, or Z. pacifica transcript to Hap1-pacifica) out of all mapping in terms of read counts and derived the median accuracy within the sample set for each gene to reduce outlier effects from samples with very low mapping. Supplementary Data 3 contains the gene pairs with accuracy >90% that were carried forward to differential expression analysis.

Differential expression and GO enrichment

To isolate Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica transcription for direct comparison of 1:1 orthologues, each hybrid sample was split post-mapping into two subsamples (Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica), and gene IDs were normalized to Hap1-marina. Differential expression was carried out using a Python implementation of DESeq2, PyDESeq2 v.0.4.12 with default_inference (https://github.com/owkin/PyDESeq2), using salmon read counts (NumReads) as input83. These quants data are presented in Supplementary Data 4. DE gene significance was defined by a DESeq2 adjusted P ≤ 0.05 across replicates and a log2 fold change absolute value ≥0.5. Biased expression is defined as DE genes between the Hap1-marina and Hap2-pacifica subsamples. For the comparison of full-light transcription (t1 and t4) to reduced light (t2 and t3), we aggregated the reduced-light samples as replicates to remedy replicate loss for Z. marina, as detailed in Supplementary Table 3. For each tissue and accession, we derived enrichment for all DE genes displaying upregulation in the low-light treatment ((t2 + t3):t1 and (t2 + t3):t4) and downregulation (t1:(t2 + t3) and t4:(t2 + t3)), to extract genes that were differentially expressed in the shade time points as compared with either t1 (control) or t4 (recovery). We treated the hybrid and Z. marina as distinct species and therefore analysed them via PyDESeq2 as separate datasets, compared through GO term enrichment analysis. For GO term enrichment analysis of each tissue and accession, we used GOATOOLS v.1.4.12 (https://github.com/tanghaibao/goatools) with the go-basic library and fdr_bh multiple test correction84. Exhaustive results of the GO enrichment analysis are presented in Supplementary Data 5.

Plastid relative coverage

Known Z. marina chloroplast and mitochondrion complete genomes—accessions NC_036014.1 and NC_035345.1, respectively—were concatenated to the chromosomal sequences of the Zmar912-Mar1 hybrid. Illumina WGS reads from the 12 tank samples were mapped to the combined sequences using minimap2 v.2.24-r1122 (https://github.com/lh3/minimap2) with secondary mapping disabled85. Bedtools v.2.30.0 (https://github.com/arq5x/bedtools2) was then used to obtain the coverage across the sequences, and the median read coverage of each sequence was recorded for all samples86. The median read coverages for the two plastid sequences were divided by the average chromosome mean read coverage to compare changes in relative plastid number for each time point and are presented in Extended Data Fig. 8.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All sequencing reads have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession PRJNA1237350. The assemblies are available via Figshare, with Z. marina at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28702679 (ref. 87), Z. pacifica at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28710650 (ref. 88) and hybrid Z. marina × pacifica at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28710710 (ref. 89).

References

Oreska, M. P. J. et al. The greenhouse gas offset potential from seagrass restoration. Sci. Rep. 10, 7325 (2020).

Papenbrock, J. Highlights in seagrasses’ phylogeny, physiology, and metabolism: what makes them special? Int. Sch. Res. Notices 2012, 103892 (2012).

Pondella, D. J., Allen, L. G., Craig, M. T. & Gintert, B. Evaluation of eelgrass mitigation and fishery enhancement structures in San Diego Bay, California. Bull. Mar. Sci. 78, 115–131 (2006).

Holmer, M. in Coastal Wetlands, 2nd edn (eds Perillo, G. M. E. et al.) 443–477 (Elsevier, 2019); https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63893-9.00013-7.

Hansen, J. & Reidenbach, M. Wave and tidally driven flows in eelgrass beds and their effect on sediment suspension. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 448, 271–287 (2012).

Waycott, M. et al. Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12377–12381 (2009).

Kelly, J. J., Orr, D. & Takekawa, J. Y. Quantification of damage to eelgrass (Zostera marina) beds and evidence-based management strategies for boats anchoring in San Francisco Bay. Environ. Manage. 64, 20–26 (2019).

Wong, M. C., Vercaemer, B. M. & Griffiths, G. Response and recovery of eelgrass (Zostera marina) to chronic and episodic light disturbance. Estuaries Coasts 44, 312–324 (2021).

Jakobsson-Thor, S., Brakel, J., Toth, G. B. & Pavia, H. Complex interactions of temperature, light and tissue damage on seagrass wasting disease in Zostera marina. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 575183 (2020).

Ward, M. & Beheshti, K. M. Lessons learned from over thirty years of eelgrass restoration on the US West Coast. Ecosphere 14, e4642 (2023).

Burke, M., Dennison, W. & Moore, K. Non-structural carbohydrate reserves of eelgrass Zostera marina. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 137, 195–201 (1996).

Ruocco, M. et al. Daily regulation of key metabolic pathways in two seagrasses under natural light conditions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 757187 (2021).

Davey, P. A. et al. A new mechanistic understanding of light-limitation in the seagrass Zostera muelleri. Mar. Environ. Res. 134, 55–67 (2018).

Eriander, L. Light requirements for successful restoration of eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) in a high latitude environment—acclimatization, growth and carbohydrate storage. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 496, 37–48 (2017).

Olsen, J. L. et al. The genome of the seagrass Zostera marina reveals angiosperm adaptation to the sea. Nature 530, 331–335 (2016).

Ma, X. et al. Seagrass genomes reveal ancient polyploidy and adaptations to the marine environment. Nat. Plants 10, 240–255 (2024).

Olesen, B. & Sand-Jensen, K. Seasonal acclimatization of eelgrass Zostera marina growth to light. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 94, 91–99 (1993).

Olsen, J. L., Coyer, J. A. & Chesney, B. Numerous mitigation transplants of the eelgrass Zostera marina in southern California shuffle genetic diversity and may promote hybridization with Zostera pacifica. Biol. Conserv. 176, 133–143 (2014).

Obaza, A. K., Bird, A., Sanders, R., Ware, R. & Ginsburg, D. W. Variable fish habitat function in two open-coast eelgrass species. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 696, 15–27 (2022).

Sanders, R. D. et al. Wave, light, and dissolved oxygen exposures drive novel coastal eelgrass (Zostera pacifica) transplant performance. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1355449 (2024).

Thom, R. M., Southard, S. L., Borde, A. B. & Stoltz, P. Light requirements for growth and survival of eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) in Pacific Northwest (USA) estuaries. Estuaries Coasts 31, 969–980 (2008).

Moore, K. A., Wetzel, R. L. & Orth, R. J. Seasonal pulses of turbidity and their relations to eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) survival in an estuary. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 215, 115–134 (1997).

Dennison, W. C. & Alberte, R. S. Role of daily light period in the depth distribution of Zostera marina (eelgrass). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 25, 51–61 (1985).

Dunic, J. C. & Côté, I. M. Management thresholds shift under the influence of multiple stressors: eelgrass meadows as a case study. Conserv. Lett. 16, e12938 (2023).

Final Eelgrass Mitigation and Monitoring Plan in Support of the 2010 Mission Bay Harbor Maintenance Dredging Project, Mission Bay, California (Merkel & Associates, 2011).

24-Month Eelgrass Monitoring Report for the Mission Bay Maintenance Dredging Project, Mission Bay, California (Merkel & Associates, 2013).

Beirinckx, L., Vanschoenwinkel, B. & Triest, L. Hidden hybridization and habitat differentiation in a Mediterranean macrophyte, the euryhaline genus Ruppia. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 830 (2020).

Sinclair, E. A., Cambridge, M. L. & Kendrick, G. A. First report of hybridization in the seagrass genus Posidonia (Posidoniaceae). Aquat. Bot. 156, 10–13 (2019).

Seehausen, O. Hybridization and adaptive radiation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 198–207 (2004).

Hochholdinger, F. & Baldauf, J. A. Heterosis in plants. Curr. Biol. 28, 1089–1092 (2018).

Abdulrahman, S. et al. Complete chloroplast genome of the marine eelgrass Zostera pacifica (Zosteraceae, Plantae) from Monterey, California. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 14, e01189–24 (2025).

Coyer, J. et al. Phylogeny and temporal divergence of the seagrass family Zosteraceae using one nuclear and three chloroplast loci. Syst. Biodivers. 11, 271–284 (2013).

Bertelli, C. M. & Unsworth, R. K. F. Light stress responses by the eelgrass, Zostera marina (L). Front. Environ. Sci. 6, 39 (2018).

Lu, Y., Hall, D. A. & Last, R. L. A small zinc finger thylakoid protein plays a role in maintenance of Photosystem II in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 23, 1861–1875 (2011).

Nowaczyk, M. M. et al. Psb27, a cyanobacterial lipoprotein, is involved in the repair cycle of Photosystem II. Plant Cell 18, 3121–3131 (2006).

Jansson, S. A guide to the Lhc genes and their relatives in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 4, 236–240 (1999).

Malnoë, A., Wang, F., Girard-Bascou, J., Wollman, F.-A. & de Vitry, C. Thylakoid FtsH protease contributes to Photosystem II and Cytochrome b6f remodeling in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under stress conditions. Plant Cell 26, 373–390 (2014).

Lu, Y. Identification and roles of Photosystem II assembly, stability, and repair factors in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 168 (2016).

von Wettstein, D., Gough, S. & Kannangara, C. G. Chlorophyll biosynthesis. Plant Cell 7, 1039–1057 (1995).

Kobayashi, K. & Masuda, T. Transcriptional regulation of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1811 (2016).

Tanaka, A. et al. Chlorophyll a oxygenase (CAO) is involved in chlorophyll b formation from chlorophyll a. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12719–12723 (1998).

Mizoguchi, T. et al. LHY and CCA1 are partially redundant genes required to maintain circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2, 629–641 (2002).

Wang, Z. Y. et al. A Myb-related transcription factor is involved in the phytochrome regulation of an Arabidopsis Lhcb gene. Plant Cell 9, 491–507 (1997).

Hugouvieux, V., Kwak, J. M. & Schroeder, J. I. An mRNA cap binding protein, ABH1, modulates early abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Cell 106, 477–487 (2001).

Su, B. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the WNK kinase gene family in soybean. Mol. Breed. 44, 16 (2024).

Kumar, K., Rao, K. P., Biswas, D. K. & Sinha, A. K. Rice WNK1 is regulated by abiotic stress and involved in internal circadian rhythm. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 316–320 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. The plant WNK gene family and regulation of flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant Biol. 10, 548–562 (2008).

Shin, K. H. et al. Alternative splicing of mini-exons in the Arabidopsis leaf rust receptor-like kinase LRK10 genes affects subcellular localisation. Plant Cell Rep. 34, 495–505 (2015).

Lee, Y. K., Olson, A., Kim, K., Ohme-Takagi, M. & Ware, D. HB31 and HB21 regulate floral architecture through miRNA396/GRF modules in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 18, 45–55 (2024).

Goodstein, D. M. et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 1178–1186 (2012).

Huang, T. et al. Low light intensity elongates period and defers peak time of photosynthesis: a computational approach to circadian-clock-controlled photosynthesis in tomato. Hortic. Res. 10, uhad077 (2023).

Rees, H. et al. Circadian regulation of the transcriptome in a complex polyploid crop. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001802 (2022).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Astashyn, A. et al. Rapid and sensitive detection of genome contamination at scale with FCS-GX. Genome Biol. 25, 60 (2024).

Kolmogorov, M., Yuan, J., Lin, Y. & Pevzner, P. A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 540–546 (2019).

Vaser, R., Sović, I., Nagarajan, N. & Šikić, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27, 737–746 (2017).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 9, e112963 (2014).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1303.3997 (2013).

Faust, G. G. & Hall, I. M. SAMBLASTER: fast duplicate marking and structural variant read extraction. Bioinformatics 30, 2503–2505 (2014).

Zeng, X. et al. Chromosome-level scaffolding of haplotype-resolved assemblies using Hi-C data without reference genomes. Nat. Plants 10, 1184–1200 (2024).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simao, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4647–4654 (2021).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Rhie, A. et al. Towards complete and error-free genome assemblies of all vertebrate species. Nature 592, 737–746 (2021).

Stiehler, F. et al. Helixer: cross-species gene annotation of large eukaryotic genomes using deep learning. Bioinformatics 36, 5291–5298 (2021).

Ou, S. et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 20, 275 (2019).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Van Bel, M. et al. PLAZA 4.0: an integrative resource for functional, evolutionary and comparative plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1190–D1196 (2018).

Yin, J. et al. A high-quality genome of taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott), one of the world’s oldest crops. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 68–77 (2021).

Ernst, E. et al. Duckweed genomes and epigenomes underlie triploid hybridization and clonal reproduction. Curr. Biol. 35, 1828–1847 (2025).

Jain, R. et al. Genome sequence of the model rice variety KitaakeX. BMC Genom. 20, 905 (2019).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Gaut, B. S., Morton, B. R., McCaig, B. C. & Clegg, M. T. Substitution rate comparisons between grasses and palms: synonymous rate differences at the nuclear gene Adh parallel rate differences at the plastid gene rbcL. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 10274–10279 (1996).

Zhang, C., Wang, J., Long, M. & Fan, C. gKaKs: the pipeline for genome-level Ka/Ks calculation. Bioinformatics 29, 645–646 (2013).

Tang, H. et al. JCVI: a versatile toolkit for comparative genomics analysis. iMeta 3, e211 (2024).

Aylward, A. J., Petrus, S., Mamerto, A., Hartwick, N. T. & Michael, T. P. PanKmer: k-mer-based and reference-free pangenome analysis. Bioinformatics 39, btad621 (2023).

Alonge, M. et al. Automated assembly scaffolding using RagTag elevates a new tomato system for high-throughput genome editing. Genome Biol. 23, 258 (2022).

Lovell, J. T. et al. GENESPACE tracks regions of interest and gene copy number variation across multiple genomes. eLife 11, e78526 (2022).

Yang, Z. & Nielsen, R. Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 32–43 (2000).

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017).

Muzellec, B., Teleńczuk, M., Cabeli, V. & Andreux, M. PyDESeq2: a python package for bulk RNA-seq differential expression analysis. Bioinformatics 39, btad547 (2023).

Klopfenstein, D. V. et al. GOATOOLS: a Python library for Gene Ontology analyses. Sci. Rep. 8, 10872 (2018).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Moore, M., Michael, T., Allsing, N. & Hartwick, N. California Zostera marina genome assemblies and annotations. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28702679 (2025).

Moore, M., Michael, T., Allsing, N. & Hartwick, N. California Zostera pacifica genome assemblies and annotations. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28710650 (2025).

Moore, M., Michael, T., Allsing, N. & Hartwick, N. California Zostera marina X Zostera pacifica genome assembly and annotation. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28710710 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Bogdanov for observing an unusual seagrass leaf phenotype in Mission Bay and sharing that with us. We also thank M. Sedarat, M. Costa, P. Lertvilai and the SIO Dive Safety Program for SCUBA dive buddy and boating support, and A. Cannon, C. Procko, E. Allen and J. Noel for helpful conversations and advice. This work was supported through the Salk Harnessing Plants Initiative with funding from the TED Audacious Project, the Bezos Earth Fund and Hess Corporation; the pangenome tool development in the Michael Lab was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant no. INV-040541 to T.P.M.). A National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship (fellow no. 2021321499) supported M.L.M.; additionally, this work was funded in part by a grant from the Tang genomics fund to T.P.M.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L.M. and T.P.M. conceived the study. M.L.M. designed the plant collection and experiment, obtained the permits, collected the plants, conducted the growth experiment and performed the nucleotide extractions. M.L.M. and E.R.M. performed the HiC experiments. M.L.M. and R.D.S. surveyed the study site, and R.D.S. described the transplant history of the study site. M.L.M., N.A., N.T.H., A.M. and T.P.M. assembled the genomes and analysed the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.P.M. is a founder of the carbon sequestration company CQuesta. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Kathryn Beheshti and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Leaf cross-sections.

Mature leaf tissue from (a) Z. pacifica (b) Hybrid (c) Z. marina imaged with a Zeiss dissecting microscope. Vascular bundles (VB) alternate with a series of functionalized aerenchyma called lacunae, which are conspicuous in leaf cross-section and contain the air which creates Zostera leaf buoyancy. As leaf width increases, this VB-lacunae pattern repeats, with Southern California Z. marina having up to five VBs, Hybrid seven, and Z. pacifica nine, though these counts vary from young to mature tissue. Original images (no cropping or contrast enhancement) available as Supplementary Data 1.

Extended Data Fig. 2 K-mer frequency estimates genome size and Hybrid clonality.

Illumina short reads produce K-mer frequency histograms for (a) Z. marina accession Zmar913-Mar3, (b) Z. pacifica accession Zpac1022-Sio2 and (c) Hybrid accession Zmar1102-1A. Peak 1 indicates the heterozygous peak (K-mer coverage at max. frequency used to estimate diploid genome size) and 2 the homozygous peak (estimates haploid genome size). Twelve Hybrid plants from Mariner’s Basin (d) demonstrate homogenous K-mer content at the homozygous and heterozygous peaks, indicating that all individuals are clones. SET d = 1 indicates K-mers found in only one individual in the set, 1<d < 12 some shared individuals but not all, and d = 12 all individuals.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Syntenic ortholog dot plots of Hybrid and scaffolded Z. marina and Z. pacifica assemblies.

Syntenic orthologs of (a) Zmar913-Mar3 vs Hybrid Hap1-marina and (b) Zpac1022-Sio2 vs Hybrid Hap2-pacifica. Numerical axes are in terms of syntenic gene count, presented in chromosomes C01-C06, not base pair position. Plots generated with JCVI Toolkit.