Abstract

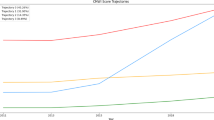

Multimorbidity elevates late-life mortality, yet existing tools remain complex. Using two nationally representative Chinese cohorts—the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity and Happiness Family Study (CLHLS-HF; n = 8675) and the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS, n = 4171)—we developed and externally validated a simplified, time-dependent, interpretable survival model. A four-stage feature-selection pipeline (univariate Cox, L1-penalized Cox, multi-model importance with 100 bootstraps, and cumulative performance) identified four routinely available predictors: age, BMI, and cooking and toileting abilities. Among five algorithms, a parsimonious Cox model performed best (C-index 0.7524 internal; 0.7104 external) with a favorable time-Brier Score (0.1417; 0.1157), good calibration, decision-curve net benefit, and subgroup fairness. Time-dependent permutation importance confirmed age as dominant, toileting ability as short-term, and cooking ability as mid- to long-term contributors, while BMI showed modest, stable effects. Implemented as the M-SAGE online tool, this four-item model enables rapid, interpretable mortality risk stratification and supports individualized interventions for older adults with multimorbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of two or more chronic conditions within an individual, has dramatically increased among older adults globally, posing critical challenges to public health systems1,2. A recent meta-analysis reported that the prevalence of multimorbidity among Chinese older adults exceeds 30% and rises steeply with advancing age3. Besides elevating all-cause mortality, multimorbidity drives high healthcare expenditures, long-term care demands, and financial stress for families4,5,6. Evidence suggests that early, comprehensive interventions, such as lifestyle modification, medication optimization, and functional training, can mitigate mortality and functional decline in older adults with multimorbidity7,8,9. Consequently, precise yet user-friendly survival prediction tools are essential to identify high-risk individuals, guide personalized interventions, and optimize resource allocation.

Currently, survival prediction for older adults with multimorbidity predominantly relies on traditional statistical methods10,11. External validation studies of commonly used 1-year mortality scores reported moderate predictive performance (C-index: 0.62–0.69), insufficient for clinical utility12,13. Traditional models struggle to capture the complex, non-linear associations and interactions among high-dimensional health characteristics, restricting their generalizability14. While machine learning algorithms offer advantages in handling complex data, existing research has been constrained by single models, small sample sizes, lack of external validation, and time-dependent effects are seldom explored10,15. In primary care or resource-limited settings, an excessive number of predictors increases data-collection burden and impedes model deployment16,17. Achieving high predictive accuracy with a concise set of easily accessible variables would substantially enhance clinical feasibility18,19. Therefore, constructing streamlined survival prediction models with robust predictive performance for older adults with multimorbidity is critical for enhancing the models’ practical utility.

Moreover, integrating time-dependent interpretability into survival models allows dynamic quantification of the contributions of predictors across survival periods, providing quantitative evidence for stage-specific interventions20. To our knowledge, rigorously validated survival models combining simplified variables with time-dependent interpretability for older adults with multimorbidity remain scarce.

Therefore, our study aimed to develop and externally validate a minimalist machine learning-based survival prediction model with high discrimination, robust calibration, time-dependent interpretability, and simplicity for older adults with multimorbidity. Using two nationally representative cohorts of Chinese older adults, the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity and Happy Family Study (CLHLS-HF) and the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a four-stage feature selection strategy was employed to minimize redundancy and enhance model stability. We also applied time-dependent interpretability methods to elucidate the dynamic contributions of key predictors across different survival intervals. The resulting online tool (M-SAGE) could offer a cost-effective and easily deployable solution for personalized risk stratification and phased interventions among older adults with multimorbidity.

Results

Study cohorts

This study enrolled 8675 older adults with multimorbidity (at least 2 of 14 specified chronic conditions, see Supplementary Table S1) in the development cohort (CLHLS-HF) and 4171 in the external validation cohort (CHARLS). A detailed sample-selection flowchart is presented in Fig. 1.

For the development cohort, the average age was 85.80 ± 11.05 years, with 55.07% being female, and an average of 2.94 conditions at baseline. The survival rates at 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year were 87.42% (95% confidence intervals [CI]: 86.73–88.12), 48.20% (95% CI: 47.11–49.32), and 26.29% (95% CI: 25.10–27.53), respectively, and the median survival time was 4.74 years (95% CI: 4.58–4.90), with the median follow-up time being 9.85 years (95% CI: 9.70–9.89). For the external validation cohort, the average age was 71.16 ± 5.92 years, with 50.92% being female, and an average of 2.82 conditions at baseline. The 1-year and 5-year survival rates were 95.76% (95% CI: 95.15–96.37) and 84.28% (95% CI: 83.17–85.40), respectively, with a median follow-up time being 9.01 years (95% CI: 9.01–9.01).

Compared with the external validation cohort (Table 1), participants in the development cohort were substantially older (85.80 ± 11.05 vs 71.16 ± 5.92 years; Standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.65), with a lower married status (37.26% vs 74.51%; SMD = 0.810), and a higher proportion of illiteracy (59.39% vs 49.58%; SMD = 0.198). The two cohorts also differed systematically (SMD > 0.20) in psychological status, lifestyle, activities of daily living (ADL) limitations, and chronic conditions, underscoring pronounced heterogeneity between the data sources. Within the development cohort, baseline characteristics were well balanced between the training and internal test subsets, with SMDs for almost all variables below 0.05 (Supplementary Table S2).

As depicted in Fig. 1, 2243 older adults with multimorbidity in the CLHLS-HF were excluded owing to missing follow-up data, resulting in an attrition rate of 20.54%. Compared with the retained development cohort (Supplementary Table S3), the excluded participants exhibited several moderate baseline imbalances (SMD = 0.20–0.35). In the CHARLS, 219 respondents were lost to follow-up (attrition rate = 0.49%). Compared with the validation cohort (Supplementary Table S4), the excluded samples from CHARLS were disproportionately urban residents, native birth, carried a higher multimorbidity count, and exhibited more pronounced ADL limitations.

Feature selection process

Utilizing a four-stage feature-selection framework (preliminary screening, regularized refinement, multi-model feature importance ranking, and cumulative performance evaluation), we identified an optimal, compact predictor set. First, utilizing univariate Cox proportional hazards regression (Coxph), we identified 53 potential features (Supplementary Table S5). Subsequently, 28 features were retained using an L1-penalized Coxph (Cox-LASSO) with λ1se (Supplementary Fig. S1). The correlation heatmap indicates generally low residual correlations among most predictors (Supplementary Fig. S2). Third, we ranked feature importance with four survival algorithms, each refit with 100 bootstrap replications to obtain stability-aware rankings (Supplementary Fig. S3). Rankings were highly concordant across algorithms: age, cooking ability, and body mass index (BMI) consistently appeared in the top three for Coxnet, GBM, and XGBoost, while RSF likewise prioritized age and cooking ability. Fourth, the top-k cumulative performance curves for each survival algorithm revealed a marginal-gain elbow at k = 3 for GBM and Coxnet (age + cooking ability + BMI), whereas XGBoost exhibited a statistically significant additional gain when toileting ability was added to the top-three set (k = 4) (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5). Accordingly, the top four features (age, cooking ability, BMI, and toileting ability), as indicated by the XGBoost ranking, achieved the highest performance and the best parsimony-stability trade-off for the simplified survival model (Supplementary Fig. S6).

To evaluate the robustness of the four-stage feature-selection framework, we conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, a direct Cox-LASSO approach retained more candidates but did not yield a significant gain in predictive performance (ΔC-index = 0.0014, P = 0.140), supporting the utility of an initial univariable Cox pre-screen. Second, compared with performing feature-importance ranking directly on the full feature set across the four algorithms, our four-stage feature-selection framework achieved a superior parsimony-performance trade-off (Supplementary Table S6 and Fig. S7).

Internal and external validation

Among the five survival models constructed using the top 4 features (Table 2, detailed inter-model performance comparison in Supplementary Table S7, 8), the Coxph model yielded optimal predictive performance in the internal testing set, achieving a Harrell’s concordance index (C-index) of 0.7524 (95% CI: 0.7519, 0.7529), the highest time-dependent area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (time-AUC) of 0.7879 (95% CI: 0.7873, 0.7885) and the lowest time-dependent Brier Score (time-BS) of 0.1417 (95% CI: 0.1415, 0.1419), which was comparable to Coxnet and GBM (P > 0.05), but significantly superior to XGBoost and Stacking (P < 0.001). Decision curve analysis (DCA) demonstrated net benefits for Coxph and Coxnet across a broad range of probability thresholds (Fig. 2A). In external validation, the Coxph model maintained good performance, with a C-index of 0.7104 (95% CI: 0.7097, 0.7111), time-AUC of 0.6568 (95% CI: 0.6561, 0.6576), time-BS of 0.1157 (95% CI: 0.1155, 0.1159), and yielded significant net benefits (Fig. 2B), supporting robustness and generalizability across datasets. Calibration curves at multiple time points (1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year) indicated good agreement between predicted and observed risks in both the internal testing and external validation sets (Fig. 2C, D). Several sensitivity analyses further supported our findings (Supplementary Table S9–11).

Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) of models in CLHLS-HF (A) and CHARLS (B); Calibration curves (1, 3, 5, and 10 years) for the optimal survival model (Coxph) in CLHLS-HF (C); Calibration curves (1, 3, and 5 years) for Coxph in CHARLS (D); Kaplan–Meier curves of high- and low-risk groups in CLHLS-HF (E) and CHARLS (F).

The time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis yielded area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUROC) of 0.776, 0.834, and 0.917 at 1, 5, and 10 years in the testing set, and 0.784 and 0.745 at 1 and 5 years in the validation cohort, demonstrating robust short-term and acceptable mid-term discrimination (Supplementary Fig. S8). Using the optimal probability threshold derived from the training set, we stratified both testing and validation sets into high- and low-risk groups (Fig. 2E, F, Supplementary Table S12). The 5-year survival rates for high-risk groups were 26.77% (95% CI: 24.51%, 29.24%) in the testing set and 45.95% (95% CI: 41.14%, 51.33%) in the validation set, whereas the rates exceeded 75% in the low-risk groups (testing set: 78.60%, 95% CI: 76.04%, 81.24%; validation set: 88.07%, 95% CI: 87.04%, 89.12%).

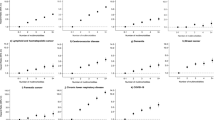

Restricted cubic splines (RCS) analysis revealed a non-linear S-shaped increase in mortality risk with age, crossing the reference line (hazard ratio [HR] = 1) at 86 (Fig. 3A). BMI exhibited an inverse J-shaped relationship: risk rose below 19, reached its nadir around 25 (HR = 0.8), and then gradually increased again beyond (Fig. 3B). Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by ADL functioning scores (0 = without assistance, 1 = needing partial assistance, 2 = needing full assistance) showed significant survival differences in both cooking ability (log-rank = 810.48, P < 0.001, Fig. 3C) and toileting ability (log-rank = 548.30, P < 0.001, Fig. 3D). Participants with no assistance needs had the longest median survival (cooking: 7.68 years, 95% CI: 7.34–8.18; toileting: 5.58 years, 95% CI: 5.19–5.95).

(A, B) Non-linear association of age and BMI with all-cause mortality using restricted cubic splines; (C, D) Survival differences across functional levels of cooking and toileting abilities in activities of daily living by Kaplan–Meier curves; (E, F) Time-dependent permutation importance of model prediction, evaluated using brier score (E) and 1-AUC (F) loss functions. Higher values denote greater feature importance at that time point.

Time-dependent interpretation analyses

Utilizing permutation-based variable-importance analysis with two time-dependent loss functions (Brier Score and 1-AUC), we dynamically quantified each feature’s contributions across the survival horizon (Fig. 3E, F). Age remained the dominant predictor throughout, with the AUC decreased by 0.1399 at 1 year and 0.1645 at 5 years when age was permuted. It also yielded the highest Brier Score in the 5–10-year interval. Toileting ability of ADL was the second-most influential factor within 1 year (AUC loss: 0.0192) but declined steadily thereafter. In contrast, the cooking ability of ADL gained influence over time, surpassing toileting at 5 years (AUC loss: 0.0245 vs. 0.0079). BMI consistently exerted the smallest and most stable effect (AUC loss < 0.0055). The time-dependent feature importance rankings were identical under both loss functions, underscoring the robustness.

Fairness analysis

As shown in Supplementary Table S13, no significant interactions were observed between the sensitive attributes (gender and multimorbidity count) and the predicted survival probabilities. Moreover, stratified analyses revealed no meaningful differences in prediction performance across subgroups (Supplementary Table S14). Including these sensitive attributes in the optimal model, therefore, did not materially affect the outcomes (Supplementary Table S15). These findings indicate that the model achieved fairness with respect to both gender and multimorbidity count.

Online tool application

As shown in Fig. 4, the M-SAGE (Survival Assessment for Geriatric Efficiently on Multimorbidity) was developed for personalized prognostic survival assessment (https://juinzhu.shinyapps.io/Survival_multimorbidity/).

Discussion

This study offers dual contributions. First, we developed and externally validated a simplified time-dependent interpretable survival prediction model specifically designed for older adults with multimorbidity. Second, the online tool (M-SAGE), incorporating only four easily accessible predictors, demonstrated good predictive performance and practical utility in supporting early risk identification and personalized intervention strategies.

Despite growing interest, rigorous prognostic research on mortality among older adults with multimorbidity remains scarce. A recent systematic review of 27 studies found that most published models incorporated more than 10 predictors and relied heavily on laboratory indices or detailed functional scales rarely available in routine primary care10. Furthermore, over 80% employed logistic regression or conventional Cox methods, achieved only median C-indices and were rarely externally validated, limiting real-world applicability10,11. Our study designed a four-stage feature-selection framework that balances parsimony and accuracy. Using a common candidate pool, the feature rankings converged across algorithms: age, cooking ability and BMI consistently occupied the top three positions for Coxnet, GBM, and XGBoost, while RSF likewise prioritized age and cooking ability. This cross-algorithm concordance suggests that these features were not artifacts of any single model’s inductive bias but reflect robust determinants of survival. Based on the top-k cumulative performance curves, the triad of age, cooking ability, and BMI captured the principal gains in discrimination. Moreover, XGBoost exhibited a marked marginal improvement when toileting ability was added, indicating that this item contributed complementary information. Guided by these results, we retained four routinely obtainable predictors: age, BMI, cooking ability and toileting ability. The resulting model achieved a C-index of 0.7524 (internal) and 0.7104 (external), outperforming previously reported 1-year mortality scores for older adults with multimorbidity (C-index: 0.62–0.69)12,13. Deployed as the lightweight M-SAGE online tool, the model provides rapid risk estimates and intuitive visualizations, offering a cost-effective, deployable solution for mortality risk stratification in resource-constrained settings and enabling more proactive, personalized geriatric care.

Time-dependent interpretability analyses further revealed that predictor contributions varied across the survival horizon. Age, a non-modifiable factor, remained the most critical feature across the entire survival and exhibited a non-linear S-shaped relationship with mortality, aligning with previous studies15,21,22. RCS analysis demonstrated a progressive rise in mortality risk after age 80, with the HR exceeding 1 at age 86, implying that preventive efforts should target the 65–85-year window to maximize intervention benefits, such as modifiable chronic condition management, ADL enhancement, and individualized nutritional optimization. In contrast, for individuals aged 86 and older, care entered a supportive phase, with residual function preservation, fall prevention, environmental adaptation and assistive device provision, and timely initiation of advance care planning. For modifiable factors (ADL, BMI), while ADL total scores are widely used in mortality prediction23,24, few studies have explored the distinctive impact of specific ADL items. Our findings revealed that toileting ability was more predictive of short-term survival, whereas cooking ability had a greater influence in predicting medium- to long-term outcomes. Toileting ability reflects core physical capacity and self-care autonomy25, while cooking ability represents higher-order functions requiring cognition and coordination26,27. Impairment in either function may indicate broader health deterioration, commonly linked to chronic conditions, frailty, and long-term care needs, which are known as risk factors for mortality28,29,30. Notably, loss of toileting ability may signal severe physiological decline and shortened survival. Therefore, routine monitoring and targeted support for these two essential functions, such as nutritional counseling, physiotherapy, social assistance, and home-environment adaptation, could help delay functional decline, improve quality of life, and may reduce mortality risk31. In addition, BMI exhibited an inverted J-shaped association with mortality, with the lowest risk range of 19–25. This finding accords with prior evidence suggesting that the optimal BMI for older adults may fall within the overweight or mildly obese category, underscoring the importance of bidirectional nutritional strategies that guard against both under- and overnutrition32,33. Taken together, these findings raise the plausible hypothesis that functional dependence and nutritional status may act as mediators linking multimorbidity to mortality risk, a pathway that warrants dedicated investigation. Overall, preserving essential daily-living functions, maintaining appropriate nutritional status, and implementing timely, individualized interventions appear pivotal for mitigating mortality among older adults with multimorbidity.

Conducting fairness analysis is indispensable for detecting and mitigating predictive bias when deploying survival models in real-world practice. It reconciles purely data-driven feature selection with clinically critical stratification factors, thereby safeguarding the model’s generalizability and clinical utility across heterogeneous individuals. Prior studies have highlighted that both gender and multimorbidity count substantially influence mortality risk among older adults with multimorbidity4,34. Our findings indicated that the model neither systematically over- nor under-estimated mortality risk across gender or multimorbidity count, thereby satisfying established principles of group fairness.

Nonetheless, several limitations warrant mention. First, the CHARLS dataset lacked exact death dates, requiring median imputation, which may affect survival time estimation. Future work will employ multiple-imputation or interval-censoring methods to assess the robustness of this assumption. Second, our model did not incorporate certain important variables, such as frailty, multimorbidity trajectory, genetic markers, or environmental factors35,36. Integrating multimodal data may further enhance predictive performance. Third, the lack of cause-specific mortality restricted our ability to build disease-specific survival models. Fourth, participants from the CLHLS-HF experienced attrition exceeding 20%, and retained several baseline imbalances, whereas loss to follow-up in CHARLS was under 5%. These discrepancies may introduce selection bias and, therefore, warrant caution when extending the model to a population with different retention profiles. Finally, although M-SAGE has been deployed, its routine clinical use still faces several critical challenges: achieving seamless data and interface integration, such as embedding ADL variables and the tool itself within electronic medical-record systems; improving end-users’ grasp of the model’s time-dependent interpretability outputs; and coordinating cross-departmental implementation of age-specific intervention strategies. Future work will aim to integrate the application into clinical workflows.

This study developed and validated a simplified survival-prediction model for older adults with multimorbidity that combines well-predictive performance with transparent, time-dependent interpretability. Leveraging a concise set of routinely collected variables, the model can be rapidly deployed in primary-care settings, and its dynamic explanations help guide the timing of interventions and the tailoring of management strategies. Moreover, our accessible online tool supports the early identification of high-risk individuals, enabling precise, targeted interventions that promote healthy ageing.

Methods

Study design and data source

This study followed the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) + AI statement37. A prospective, dual-cohort design was adopted: the survival prediction model was developed and internally validated in the CLHLS-HF38 and externally validated in the CHARLS39. Both cohorts are nationally representative, community-based longitudinal studies that conduct follow-ups every 2–4 years and systematically collect sociodemographic, lifestyle, psychological, functional, and physical health data. CLHLS-HF, launched in 1998, targets individuals aged 65 and older, while CHARLS, initiated in 2011, enrolls adults aged 45 and above. Both cohorts received ethical approval from the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University (CLHLS-HF: IRB0000105213074, CHARLS: IRB0000105211015). All participants or their legal representatives provided written informed consent to indicate their willingness to participate in the CLHLS-HF and CHARLS. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Given that all data were de-identified before analysis, no additional ethical approval was required.

Study population

Participants were eligible if they were aged 65 and older at baseline, had at least 2 of 14 specified chronic conditions, and had a complete survival outcome1,40. Individuals with missing data on any of the 14 conditions were excluded. Given CLHLS-HF began recording additional conditions (e.g., arthritis or rheumatism) since 2008, we merged the 2008, 2011, and 2014 waves, removed duplicates, and treated the combined dataset as the baseline of the development cohort, with follow-up until 201815,41. For external validation, data from the 2011, 2013, and 2015 waves from CHARLS were similarly merged (duplicate records removed) and follow-up extended to 2020.

The final analytical sample included 8675 older adults with multimorbidity in the development cohort (37516.70 person-years) and 4171 in the external validation cohort (26122.37 person-years).

Survival outcome

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, including survival time and status. Survival time was defined as the interval from enrollment to death, last follow-up, or the end of the study, whichever came first. Information on mortality was confirmed by family members or close relatives. Since CHARLS did not provide exact dates of death, the death date was approximated as the midpoint between the last two waves42.

Predictors

Drawing on established evidence and consensus in geriatrics and multimorbidity regarding mortality outcomes, we first prioritized core domains including sociodemographic, lifestyle, and anthropometrics21,23. Aligned with scalability in primary care and resource-constrained settings, we focused on low-cost, non-invasive information and deliberately avoided reliance on laboratory or imaging indices. To ensure cross-cohort comparability and enable external validation, all candidate variables were harmonized and consistently coded in both CLHLS-HF and CHARLS with controlled missingness. Accordingly, we assembled an initial candidate set of 58 baseline variables spanning sociodemographic, lifestyle, ADL, psychological, physical function, and health conditions.

Sociodemographic factors included age, gender, residence, birthplace, residential region, marital status, education, and retirement benefits. Age was determined based on self-reported birth dates and verified through family member accounts, genealogical records, ID cards, and household registration booklets. Gender was categorized as male and female. Residence included urban, town and rural areas. Birthplace was classified as native or outlander. Residential region was categorized into Eastern China (Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, and Hainan), Central China (Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, and Hunan), Western China (Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang), and Northeastern China (Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning), according to geographical, climatic, and dietary differences. Marital status was classified into married and other (widowed, divorced, separated, or never married). Education was divided into illiteracy and literacy. Retirement benefits were assessed by whether participants received retirement benefits when retired.

Lifestyle factors included smoking status, drinking status, traveling status, and social involvement activities. Smoking and drinking status were both categorized as never, ever, and current. Traveling status was determined based on whether the times or expenses exceeded zero in the past year. Social involvement activity included outdoor activity, playing cards or mahjong, and organized social activity, and each item was scored from 1 (almost daily) to 3 (not regularly or never). Higher score of each item indicated poorer ability to engage in social involvement activity. Psychological factors included life satisfaction, self-rated health and personality mood. Life satisfaction and self-rated health were both scored 1 (very good) to 5 (very bad), with a higher score corresponding to worse life satisfaction or health status. Personality mood was assessed using five questions (fearfulness, loneliness, uselessness, unhappiness, insomnia) and scored from 0 (rarely or none) to 3 (most or always), respectively. Higher score of each item indicated a more pessimistic personality or negative mood.

ADL contained basic ADL (BADL) and instrumental ADL (IADL). BADL included fundamental skills (bathing, dressing, toileting, getting up, continence, and eating) required to care for oneself, while IADL encompassed more complex tasks (shopping, cooking, washing, walking, carrying, and crouching) needed for independent living and daily life management in a community. Each subscale of the ADL was scored from 0 (without assistance) to 1 (needing partial assistance) to 2 (needing full assistance), with a higher score indicating greater physical disability. Each component of ADL was directly incorporated into the models to explore the specific contribution.

Physical function included sleep time, tooth loss (yes or no), and physical examination, which assessed systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate, height, weight, BMI, upper arm length, and knee height. Also, we included the 14 specific chronic conditions and calculated the multimorbidity count from them.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.2.3), and machine learning modeling was implemented using the “mlr3” package (version 0.18.0). Continuous variables were summarized as mean (standard deviation), and categorical variables were presented as counts (percentage). Baseline characteristics were compared across different samples using one-way ANOVA or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test for categorical variables, including comparisons between the development and validation cohorts, the training and testing sets, as well as between the analytical samples (development and validation cohorts) and their corresponding excluded samples (withdraw individuals). SMD was used to assess baseline differences across samples. Pairwise correlations among candidate predictors were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation (ρ), and the correlation matrix was visualized as a heatmap. Univariate Coxph models were employed to evaluate the association between baseline predictors and survival outcomes. The proportional hazards assumption of the Cox model was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals. Overall survival differences were determined with the Kaplan–Meier curve and log-rank test. Multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction, and a two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data preprocessing

The workflow of model development and validation is illustrated in Fig. 5. The development cohort was randomly divided into training and testing sets (7:3 ratio). Data preprocessing was performed separately for each dataset and included outlier detection, missing value imputation using the “missForest” algorithm, standardization of continuous variables, and one-hot encoding of categorical variables43.

Feature selection framework

To balance parsimony with predictive accuracy, we implemented a four-stage, data-driven feature selection pipeline in the training set16,17,18. (1) Preliminary screening: All 67 candidate features, derived from 58 baseline variables, were evaluated in univariate Coxph regression. Features with P < 0.10 were retained to eliminate obvious noise and curb overfitting. (2) Regularized refinement: The retained features were reduced using Cox-LASSO44. The optimal penalty (λ) was chosen via 10-fold cross-validated C-index, attenuating multicollinearity and further reducing redundancy. (3) Multi-model feature importance ranking: Feature importance was quantified with four mainstream survival machine learning algorithms, including Generalized Linear Model with Elastic Net Regularization Survival Learner (Coxnet)45, Survival Gradient Boosting Machine Learner (GBM)46, Survival Random Forest SRC Learner (RSF)47, and Extreme Gradient Boosting Survival Learner (XGBoost)48. Each algorithm was repeated 100 bootstrap replications to rank the top 10 feature stability. (4) Cumulative performance evaluation: Following each algorithm’s importance ranking, features were added sequentially to construct survival models. Using 5-fold cross-validation, five survival models (including the above four and Coxph) were trained to evaluate the cumulative performance. The smallest subset was selected with the optimal trade-off between simplicity and performance.

To verify robustness, we conducted two complementary sensitivity analyses. First, we compared “univariable Cox pre-screening + Cox-LASSO” versus “direct Cox-LASSO” with respect to the selected feature sets and downstream performance to assess whether pre-screening confers additional de-noising benefits. Second, we contrasted feature-importance ranking directly on the full feature set across the four algorithms (Coxnet, GBM, RSF, and XGBoost), against our four-stage pipeline by examining top-k cumulative performance curves, thereby testing whether the proposed framework achieves a superior parsimony-performance balance.

Model development

Based on the optimal feature set, we developed five survival models: Coxph, Coxnet, GBM, XGBoost, and a Stacking model (using Coxph as the meta-learner with Coxnet/GBM/XGBoost as base learners). Hyperparameters were tuned using the Bayesian Optimization with Hyperband (BOHB) coupled with 10-fold cross-validation on the training set49, using Harrell’s C-index as the objective. Search spaces were defined as follows to balance breadth and plausibility: for GBM, n.trees∈[10,2000], interaction.depth∈[1,15], shrinkage∈[0.01,0.10]; for Coxnet, α∈[0,1] and nlambda∈[10,2000]; for RSF, ntree∈[10,2000], mtry∈[2,20], nodesize∈[1,20], and nsplit∈[1,20]; for XGBoost, max_depth∈[3,10], nrounds∈[10,2000], eta∈[0.01,0.30], colsample_bytree∈[0,1], subsample∈[0,1], and regularization parameters λ,α,γ∈[0,1]. The BOHB procedure adaptively allocated budget across configurations and folds, converging to well-calibrated settings for each learner. Final selected hyperparameters are reported in Supplementary Table S16.

Internal evaluation and external validation

Model performance was evaluated in the testing set from CLHLS-HF and externally in the validation cohort from CHARLS. Discrimination was assessed using C-index and time-AUC, with higher values indicating superior performance. Calibration was assessed using calibration curves and time-Brier Score, with lower values denoting excellent calibration. All metrics were calculated with 95% CI derived from 1000 bootstrap resamples50.

To compare models, C-index differences were tested with the “compareC” package, using the “compareC” function to perform a nonparametric test for correlated C-indices on the same sample51. Time-AUC differences were quantified with the “survcomp” package: Uno’s IPCW AUC was estimated at prespecified time points, and compared between models using a paired Wilcoxon signed-rank procedure52.

Clinical net benefit was evaluated using DCA53. Time-dependent ROC curves were employed to evaluate prediction performance over 1, 5, and 10 years.

Risk stratification was performed by determining the optimal cut-off threshold in the training set via the “survminer” package, and Kaplan–Meier curves with log-rank tests were applied to compare survival differences between high- and low-risk groups in the testing and external validation sets.

Nonlinear associations between continuous predictors and survival were examined using RCS in Coxph models, with the optimal number of knots determined via Akaike information criterion. Survival differences across categorical variables were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests.

Time-dependent interpretability analysis

Using the “survex” package, we applied time-dependent permutation importance analysis to quantify the dynamic contribution of each feature over the survival horizon54. For the optimal model, at each time t, we randomly permuted one feature while holding others fixed, re-evaluated model performance with a standardized loss, and defined the importance as lossperm – lossfull. We used two time-dependent loss functions to capture both calibration and discrimination: the Brier score (a combined error metric) and 1-AUC (a discriminative loss). Accordingly, we reported trajectories of ΔBrier(t) and ΔAUC(t) to depict temporal contribution profiles, where larger values indicate greater performance deterioration, and thus greater importance at time t.

Fairness evaluation

To assess model fairness with respect to the sensitive attributes (gender, multimorbidity count), we conducted a series of fairness analyses55. First, we examined the interactions between each sensitive attribute and the predicted survival probabilities56. Second, we evaluated model performance separately within subgroups defined by these attributes57. Third, we refitted the model by forcibly including the sensitive attributes and recalculated the performance to quantify any changes resulting from their inclusion56,57.

Online tool application

Following findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable (FAIR) principles58, we developed an interactive online survival prediction tool using the “shiny” package. The tool enables users to input individual-level features and obtain personalized survival probabilities.

Sensitivity analyses

To test the robustness and generalizability of the optimal model, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. We first restricted the analysis to participants with complete data on all selected predictors. Second, for those with any missing data in the assessment of the 14 specific chronic conditions, each absence was assumed as “free of condition”, and the multimorbid population was redefined accordingly. A total of 1147 additional individuals were included to evaluate model generalizability. Third, considering that the ADL score represents an incremental hierarchy of functional limitation, we refitted the model treating ADL as an ordinal categorical variable to verify the robustness of the estimates without imposing a linear-distance assumption.

Additionally, to evaluate the potential violation of the proportional hazards assumption, we further applied a Cox model with time-dependent covariate interactions and an accelerated failure time model as an alternative modeling strategy.

Data availability

The CLHLS-HF dataset is open to researchers with reasonable requests and can be found at https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/dataverse/CHADS. The CHARLS dataset is open to researchers with reasonable requests and can be found at http://charls.pku.edu.cn. All the database includes anonymous responses from all CLHLS-HF and CHARLS study respondents.

Code availability

Algorithms underpinning the simplified survival machine learning models are available from the multi_survival repository at https://github.com/juinzhu/multi_survival. Code for statistical analysis is available upon reasonable request.

References

Academy of Medical Sciences. Multiple long-term conditions (Multimorbidity): a priority for global health research. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/policy/policy-projects/multimorbidity (2018).

Whitty, C. J. M. et al. Rising to the challenge of multimorbidity. BMJ 368, l6964 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in China during 2002–2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 93, 102165 (2024).

Yao, S.-S. et al. Multimorbidity measures differentially predicted mortality among older Chinese adults. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 146, 97–105 (2022).

Tran, P. B. et al. Costs of multimorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Med. 20, 234 (2022).

Nunes, B. P., Flores, T. R., Mielke, G. I., Thumé, E. & Facchini, L. A. Multimorbidity and mortality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 67, 130–138 (2016).

Skou, S. T. et al. Exercise therapy and self-management support for individuals with multimorbidity: a randomized and controlled trial. Nat. Med. 31, 3176–3182 (2025).

Veronese, N. et al. Long-term impact of physical activity on mortality in adults with multimorbidity: a 12-year cohort longitudinal study from the survey on health, ageing and retirement in europe. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 16, e13695 (2025).

Sheppard, J. P. et al. Effect of antihypertensive deprescribing on hospitalisation and mortality: long-term follow-up of the OPTiMISE randomised controlled trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. 5, e563–e573 (2024).

Chen, Y.-Y. et al. Risk prediction models for mortality in patients with multimorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 13, 1505541 (2025).

Exmann, C. J. C. et al. Mortality prediction models for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 101, 102525 (2024).

Schneider, C. et al. Comparison of 6 mortality risk scores for prediction of 1-year mortality risk in older adults with multimorbidity. JAMA Netw. open 5, e2223911 (2022).

Aubert, C. E. et al. HOSPITAL score and LACE index to predict mortality in multimorbid older patients. Drugs Aging 39, 223–234 (2022).

Leist, A. K. et al. Mapping of machine learning approaches for description, prediction, and causal inference in the social and health sciences. Sci. Adv. 8, eabk1942 (2022).

Xing, M. et al. Development and validation of a stacking ensemble model for death prediction in the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey (CLHLS). Maturitas 182, 107919 (2024).

Yang, Q. et al. A machine learning–based preclinical osteoporosis screening tool (POST): model development and validation study. JMIR Aging 6, e46791–e46791 (2023).

Yan, L. et al. An interpretable mortality prediction model for COVID-19 patients. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 283–288 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Artificial intelligence based multispecialty mortality prediction models for septic shock in a multicenter retrospective study. npj Digit Med. 8, 228 (2025).

Ning, C. et al. Development and validation of an explainable machine learning model for mortality prediction among patients with infected pancreatic necrosis. eClinicalMedicine 80, 103074 (2025).

Krzyziński, M., Spytek, M., Baniecki, H. & Biecek, P. SurvSHAP(t): time-dependent explanations of machine learning survival models. Knowl.-Based Syst. 262, 110234 (2023).

Duan, J. et al. The development and validation of a nomogram-based risk prediction model for mortality among older adults. SSM - Popul. Health 25, 101605 (2024).

Suemoto, C. K. et al. Development and validation of a 10-year mortality prediction model: meta-analysis of individual participant data from five cohorts of older adults in developed and developing countries. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 72, 410–416 (2017).

Xi, D. et al. Risk factors associated with heatwave mortality in Chinese adults over 65 years. Nat. Med. 30, 1489–1498 (2024).

Osawa, T. et al. Activities of daily living, hypoxemia, and lymphocytes score for predicting mortality risk in patients with pulmonary TB. CHEST 165, 267–277 (2024).

Heiland, E. G. et al. Association of mobility limitations with incident disability among older adults: a population-based study. Age Ageing 45, 812–819 (2016).

Soriano, G. et al. Meal-related difficulties and weight loss in older people: longitudinal data from MAPT study. Clin. Nutr. 39, 3483–3488 (2020).

Njegovan, V., Man-Son-Hing, M., Mitchell, S. L. & Molnar, F. J. The hierarchy of functional loss associated with cognitive decline in older persons. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M638–M643 (2001).

Nielsen, A. B. et al. Survival prediction in intensive-care units based on aggregation of long-term disease history and acute physiology: a retrospective study of the Danish national patient registry and electronic patient records. Lancet Digit. Health 1, e78–e89 (2019).

Wei, M. Y., Kabeto, M. U., Galecki, A. T. & Langa, K. M. Physical functioning decline and mortality in older adults with multimorbidity: joint modeling of longitudinal and survival data. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74, 226–232 (2019).

Han, E.-J., Song, M. K. & Lee, Y. The 10-year multimorbidity trajectory and mortality risk in older people with long-term care needs. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 103, 104775 (2022).

Zheng, J. et al. Diet quality and mortality among Chinese adults: findings from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Nutrients 16, 94 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Obesity paradox of cardiovascular mortality in older adults in the United States: a cohort study using 1997–2018 National Health Interview Survey data linked with the National Death Index. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 155, 104766 (2024).

Lv, Y. et al. Body mass index, waist circumference, and mortality in subjects older than 80 years: a mendelian randomization study. Eur. Heart J. 45, 2145–2154 (2024).

Jani, B. D. et al. Relationship between multimorbidity, demographic factors and mortality: findings from the UK Biobank cohort. BMC Med. 17, 74 (2019).

Simard, M. et al. 10-Year multimorbidity trajectories in older people have limited benefit in predicting short-term health outcomes in comparison to standard multimorbidity thresholds: a population-based study. Clin. Epidemiol. 16, 345–355 (2024).

Eto, F. et al. Ethnic differences in early onset multimorbidity and associations with health service use, long-term prescribing, years of life lost, and mortality: a cross-sectional study using clustering in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. PLoS Med. 20, e1004300 (2023).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 385, e078378 (2024).

Zeng, Y., Feng, Q., Hesketh, T., Christensen, K. & Vaupel, J. W. Survival, disabilities in activities of daily living, and physical and cognitive functioning among the oldest-old in China: a cohort study. Lancet 389, 1619–1629 (2017).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 61–68 (2014).

Hou, C. et al. Medical conditions associated with coffee consumption: disease-trajectory and comorbidity network analyses of a prospective cohort study in UK Biobank. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 116, 730–740 (2022).

Ji, J. S. et al. Residential greenness and mortality in oldest-old women and men in China: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Planet. Health 3, e17–e25 (2019).

Li, C., Wang, L., Ding, L. & Zhou, Y. Determinants and inequities in healthy working life expectancy in China. Nat. Med. 30, 3318–3326 (2024).

Stekhoven, D. J. & Bühlmann, P. MissForest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 28, 112–118 (2012).

Bielza, C., Robles, V. & Larrañaga, P. Regularized logistic regression without a penalty term: an application to cancer classification with microarray data. Expert Syst. Appl. 38, 5110–5118 (2011).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Friedman, J. H. Stochastic gradient boosting. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 38, 367–378 (2002).

Hothorn, T. & Zeileis, A. Partykit: a modular toolkit for recursive partytioning in R. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 16, 3905–3909 (2015).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost. In Proc. the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (ACM, 2016).

Falkner, S., Klein, A. & Hutter, F. BOHB: Robust and efficient hyperparameter optimization at scale. In Proc. 35th international conference on machine learning (eds Dy, J. & Krause, A.) vol. 80 1437–1446 (PMLR, 2018).

NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Global Surgery. Development of a machine learning–based prescriptive tool to address racial disparities in access to care after penetrating trauma. JAMA Surg. 158, 1088 (2023).

Kang, L., Chen, W., Petrick, N. A. & Gallas, B. D. Comparing two correlated C indices with right-censored survival outcome: a one-shot nonparametric approach. Stat. Med. 34, 685–703 (2015).

Schröder, M. S., Culhane, A. C., Quackenbush, J. & Haibe-Kains, B. survcomp: an R/bioconductor package for performance assessment and comparison of survival models. Bioinformatics 27, 3206–3208 (2011).

Van Calster, B. et al. Reporting and interpreting decision curve analysis: a guide for investigators. Eur. Urol. 74, 796–804 (2018).

Spytek, M. et al. survex: an R package for explaining machine learning survival models. Bioinformatics 39, btad723 (2023).

Collins, G. S. et al. Evaluation of clinical prediction models (part 1): from development to external validation. BMJ 384, e074819 (2024).

Khor, S. et al. Racial and ethnic bias in risk prediction models for colorectal cancer recurrence when race and ethnicity are omitted as predictors. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2318495 (2023).

Schuch, H. S. et al. Fairness of machine learning algorithms for predicting foregone preventive dental care for adults. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2341625 (2023).

Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3603000) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82404373). The authors would like to thank CLHLS-HF and CHARLS for providing us with the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z.: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, visualization, and writing—original draft. H.C.: Data curation, software, and validation; S.D.: Investigation, and methodology; Y.W.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, resources, validation, and writing—review and editing; Y.F.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, and writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, J., Chen, H., Duan, S. et al. Development and validation of a simplified time-dependent interpretable machine learning-based survival model for older adults with multimorbidity. npj Aging 12, 10 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00308-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00308-y