Abstract

Auranofin (AF), a former rheumatoid polyarthritis treatment, gained renewed interest for its use as an antimicrobial. AF is an inhibitor of thioredoxin reductase (TrxB), a thiol and protein repair enzyme, with an antibacterial activity against several bacteria including C. difficile, an enteropathogen causing post-antibiotic diarrhea. Several studies demonstrated the effect of AF on C. difficile physiology, but the crucial questions of resistance mechanisms and impact on microbiota remain unaddressed. We explored potential resistance mechanisms by studying the impact of TrxB multiplicity and by generating and characterizing adaptive mutations. We showed that if mutants inactivated for trxB genes have a lower MIC of AF, the number of TrxBs naturally present in clinical strains does not impact the MIC. All stable mutations isolated after AF long-term exposure were in the anti-sigma factor of σB and strongly affect physiology. Finally, we showed that AF has less impact on human gut microbiota than vancomycin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clostridioides difficile is a Gram-positive, anaerobic and spore-forming bacterium responsible for post-antibiotic gastrointestinal infections1. During dysbiosis, a switch of microbiota leading to a change of metabolites is observed favoring C. difficile colonization and infection2,3. Clinical signs of C. difficile infections (CDIs) are diarrhea, pseudo-membranous colitis and toxic megacolon, which can lead to the death of the patient2. Historically identified as a healthcare-associated infection, changes in epidemiology have been observed during the last years, with now around 25% of community-associated CDIs4. The symptoms of CDIs are caused by the toxins of C. difficile5. TcdA and TcdB cause disruption of the epithelial intestinal barrier6,7, resulting in a strong inflammation with recruitment of immune cells and production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species6,8,9. CDT is an additional binary toxin, only present in some strains, that is associated to severe infections and increased risk of recurrences10,11. Indeed, after a first episode, a high rate of recurrences (20–25%) is usually observed12. Risk factors of recurrences are age and the antibiotic treatment used13. Indeed, the use of large spectrum antibiotic treatment inducing a strong disruption of the gut microbiota favors recurrences while the gut microbiota recovery protects from recurrence. On the bacterial side, these recurrences are at least partly due to the production of spores, which allows dissemination and transmission of this anaerobe pathogen5. These spores are highly resistant to air and disinfectants, and are responsible for widespread contamination in hospital and for re-infection of patients1. Biofilms might be another mechanism of recurrences of CDI, favoring persistence in the gut during antibiotic treatment14,15.

First-line antibiotics for CDIs are vancomycin (Van) and fidaxomicin (Fdx) as metronidazole (Mtz) is now recommended only for pediatric infections16. After one or more recurrences, alternative treatments are recommended such as addition to the antibiotic treatment of bezlotoxumab, an anti-TcdB monoclonal antibody, or fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)16. The choice of therapy will depend on the severity of infection, the risk and number of recurrences and the cost of the treatment. Despite all these treatments, CDIs remain a challenge to treat. Around 200,000 and 500,000 cases a year are observed in Europe17 and in the US18, respectively, with a mortality rate of 5–10%17,19. These numbers are diminishing in the last few years4, notably with the increasing use of Fdx, FMT and bezlotoxumab. Although expensive20,21, these treatments show better clinical efficacy and protection against recurrence than Van and Mtz22,23. However, even if limited yet, Fdx resistant strains isolated from patients have been recently described24,25,26. Thus, alternative treatments are still needed, and therapeutic repositioning is one of the considered options, as it allows faster and cheaper development, clinical trials, and commercialization.

Auranofin (AF) is a drug formerly commercialized as Ridauran for its anti-inflammatory properties in the treatment of rheumatoid polyarthritis27. Due to more efficient treatments, its use has been gradually stopped in several countries. However, recent studies showed an antibacterial potential for this molecule, with activity against various pathogens including Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp., Helicobacter pylori, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and C. difficile28,29,30,31. AF was shown to impact growth and survival of C. difficile vegetative cells32,33 and to decrease spore formation and toxin production29,32. Accordingly, an AF treatment increases survival in hamster or mouse models of CDI by reducing gut damages32,34,35.

The mode of action of AF remains unclear. AF has a bactericidal effect against Mycobacterium spp. and Neisseria gonorrhoeae28,36,37, but a bacteriostatic effect against Enterococcus spp.38. AF is known to be an inhibitor of bacterial thioredoxin-reductases (TrxB), as demonstrated on the purified enzymes of M. tuberculosis and S. aureus28. A recent study showed the crucial role of the thiol repair thioredoxin systems in C. difficile physiology39. Three thioredoxins (TrxAs) and three to four TrxBs are present in C. difficile strains. Two TrxBs (TrxB2 and TrxB3) are canonical NADPH-dependent flavin TrxBs (NTRs) while the third one (TrxB1) is a ferredoxin-dependent flavin TrxB (FFTR), an anaerobe-specific class of TrxB. Two thioredoxin systems (TrxA1, TrxA2, TrxB1, TrxB2) are involved in stress response, protecting vegetative cells from exposure to O2, inflammation-related molecules and bile salts. The TrxA1/B1 system is also present in the spores and contributes to germination and survival to hypochlorite (HOCl), a disinfectant used to eradicate the spores. Finally, the third system (TrxA3/B3) contributes to glycine reduction and sporulation. In addition to the possible TrxB inhibition, AF has a broader effect on thiol homeostasis and selenium metabolism33. C. difficile possesses two selenoenzymes involved in Stickland metabolism, the proline-reductase, PrdB, and the glycine-reductase, GrdA40. The clostridial-specific Stickland pathways allow the production of energy from the degradation of amino acids41,42. Various studies show the involvement of Stickland metabolism in C. difficile colonization and infection42,43. Interestingly, the recycling of the selenoenzyme GrdA is ensured by a dedicated system TrxA3/B3 encoded by the glycine-reductase operon39,44.

All these studies provide good arguments for the use of AF as a new treatment for CDI. However, several elements are lacking before going through clinical trials. In C. difficile, the precise targets of AF and potential resistance mechanisms remain uncharacterized while interactions with molecules produced in the gut during infection and with first-line treatments are not described. Moreover, AF spectrum of action and its impact on the gut microbiota has never been studied. This question is crucial, especially in a context where the gut microbiota is the main barrier against CDIs and recurrences1,13. In this work, we studied AF interactions with other therapeutic molecules or with infection-related molecules, addressed the question of potential resistance mechanisms in clinical strains or generated in laboratory, and analyzed the impact of AF on human gut microbiota in vitro.

Results

Role of TrxBs in AF response

Bacterial TrxBs are known to be the first target of AF28. The C. difficile 630∆erm strain has three trxB genes in its genome39. We have previously inactivated the trxB1 and trxB2 genes in the 630∆erm strain and obtained a double trxB1/trxB2 mutant39. To investigate the role of TrxB in AF tolerance in C. difficile, we performed a Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) assay (Table 1). The MIC of the strain 630∆erm is 0.75 µg mL−1. Single trxB mutants had similar MIC to that of the parental strain, while a 2-fold decrease was observed for the double trxB1/trxB2 mutant. We observed a similar trend using an assay on plates containing sub-inhibitory doses of AF (Fig. 1A, B), with a survival defect only for the double mutant. These results indicate that the inactivation of the genes encoding the two TrxBs involved in stress response increased the susceptibility to AF.

A, B Growth of trxB mutants in presence of AF. A Culture of 630∆erm was serially diluted and spotted on TY and TY containing AF 0.5 µg mL−1. B The survival was calculated by doing the ratio between CFUs with AF and CFUs without AF. Experiment was performed in six biological replicates. Mean and SD are shown. C MBCs of trxB mutants. MIC experiments were performed and CFUs from inoculum and wells with no visible growth were numerated. Survival was calculated by doing the ratio between the CFUs after and before treatment. Experiment was performed in four biological replicates. Geometric mean and geometric SD are shown. D MICs of clinical strains. MICs of clinical strains encoding or not the trxB4 gene were compared. The clade of each strain is indicated by a color code. The MIC to AF of these different strains carrying or not the trxB4 gene were indicated in Supplementary Table 1. MICs were performed in four biological replicates. E MBC of strains containing or not the trxB4 gene. MIC experiments were performed on the 630∆erm strain, the 630∆erm strain expressing the trxB4 gene or on the E1 and RT027 strains, which naturally contain the trxB4 gene. CFUs from inoculum and wells with no visible growth were numerated. Survival was calculated by doing the ratio between the CFUs after and before treatment. Experiment was performed in four biological replicates. Geometric mean and geometric SD are shown. For survival on plate, one-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison. For MBC, Mann–Whitney tests were used. For the MIC comparison, a Mann–Whitney test was used. * indicates p value < 0.05.

As AF has been shown to have a bactericidal effect on several bacteria28,36,37, we performed a Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) experiment (Fig. 1C). We demonstrated that AF have a bactericidal effect on C. difficile, with a MBC of 1.5 µg mL−1 for the 630∆erm strain. This MBC remained similar in the single trxB1 and trxB2 mutants, while the double mutant MBC was 0.75 µg mL−1 with a 5-log decrease of survival compared to the parental strain (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, a significant drop of survival was observed at 0.75 µg mL−1 for the trxB1 mutant compared to the WT strain, suggesting that this mutant was more susceptible to AF than the parental strain. No significant differences were observed between the trxB1 and the trxB2 mutant. These results confirm that TrxBs are involved in AF tolerance with a slightly more pronounced effect of TrxB1, and strongly suggest that C. difficile TrxBs are AF targets.

Impact of the presence of an additional TrxB paralog on AF susceptibility

Not all C. difficile strains harbor the same number of trxB genes. Indeed, we have recently identified the presence of a fourth trxB gene (trxB4) widely distributed in C. difficile strains from clades 3 and 539. TrxB4, like TrxB1, is a FFTR45 contrary to TrxB2 and TrxB3 which are NTRs. As we observed a higher susceptibility of the trxB1 mutant to AF, we investigated the influence of the presence of a second FFTR on AF resistance. The MIC of a panel of clinical strains harboring or not the trxB4 gene (Supplementary Table 1) was tested. Clade 3 and clade 5 strains carrying the trxB4 gene were included, but also trxB4-positive strains from clade 1 and clade 2 for which most of the strains are not encoding the trxB4 gene39. No significant difference in the MIC of AF was observed between the strains harboring or not the trxB4 gene (Fig. 1D). In addition, there were no differences in MIC between strains with or without trxB4 in clades 1 and 2. As trxB gene deletion has an impact on MBC, we assessed the MBC of three strains encoding trxB4. We used two clinical strains, the E1 (clade 5) and the RT023 strain (clade 3), and the 630∆erm strain harboring a pMTL84121 plasmid carrying the trxB4 gene from the E1 strain expressed under the control of its own promoter39. Both the E1 and the RT027 strains had a MIC of 1.5 µg mL−1 (Supplementary Table 1) and a MBC of 3 µg mL−1 (Fig. 1E), corresponding to a 2-fold increase compared to the 630∆erm strain. The expression of the trxB4 gene in the 630∆erm strain did not change neither the MIC nor the MBC. Even though a slight increase in resistance was observed for the two clinical strains encoding TrxB4, our results are not sufficient to conclude that this additional FFTR impacts susceptibility to AF.

Interaction of AF with other antibiotics used for C. difficile infection treatment

Another potential resistance mechanism that could be already spread in C. difficile strains is cross-resistance with antibiotics of first-line treatments. We evaluated the AF MICs of clinical strains resistant to Mtz or Fdx and of strains with a decreased sensitivity to Van (Table 2). The MICs of these strains were between 0.375 and 1.5 µg mL−1, corresponding to a 2-fold change or less compared to the 630∆erm reference strain. The absence of higher MIC of AF for clinical resistant strains indicates that no cross-resistance was detected. We also tested the synergy of AF with the three antibiotics used for CDI treatments using the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) method46 (Table 3). We obtained values between 0.5 and 1 for Fdx and Mtz, suggesting an additive effect with AF. For Van, the FIC value was between 1 and 4 indicating no interaction with AF. Our results suggest that no cross-resistance mechanism is already present in clinical strains of C. difficile and indicate that no antagonism exists between AF and the first-line treatments against CDIs. The risks of using a two-drug therapy with AF are therefore limited.

Generation of adaptive mutations through long-term exposure to AF

In order to study the appearance of resistance in vitro, we tried to generate mutations conferring a decreased susceptibility to AF via two strategies. We first used a screening of spontaneous resistant clones by plating cultures of strain 630∆erm on plates containing high doses of AF (5 and 10 µg mL−1). After 5 to 7 days at 37 °C, clones were visible on plates but the MIC of most of these clones remained between 0.75 and 1.5 µg mL−1. Three clones had an increased MIC (3 to 6 µg mL−1). However, when sequenced, no mutations were identified, suggesting an absence of stability of the selected mutations.

The second approach was a long-term exposure to sub-inhibitory dose of AF with iterative MIC experiments (Fig. 2A). After a first MIC experiment, the well with visible growth at the highest concentration of AF was used to prepare the inoculum for the next MIC experiment. This method allows an adaptive increase of the AF dose over time. We performed this experiment for 30 days and followed the MIC of the 630∆erm and the E1 strains. The MIC of both strains increased slightly over the experiment. The maximum MIC values reached during the experiment were 3 and 6 µg mL−1 obtained for the 630∆erm and E1 strains, respectively, corresponding to a 4-fold increase. Importantly, this increase was not stable over time regardless of the strain, with variations of the MIC from day to day. Finally, the E1 strain had a higher MIC over time than the 630∆erm (two-way ANOVA, p value = 0.03), confirming that the E1 strain is more tolerant to AF than the 630∆erm strain (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 2A).

A Evolution of AF MIC during long time exposure. MIC experiments were performed on the 630∆erm and the E1 strain over 30 days. Every day, the bacterial suspension with visible growth at the highest AF concentration was used to prepare a new MIC experiment after a 1:100 dilution. MIC was recorded daily. Thin lines represent the four biological replicates of each strain, thick line represents the median. B, C Survival of mutated strains. Cultures of 630∆erm, rsbW* and rsbWSTOP strains (B) or cultures of 630∆erm pDIA6103, rsbWSTOP pDIA6103 and rsbWSTOP pDIA6103-rsbW strains (C) were serially diluted and spotted on TY and TY containing AF at 0.75 µg mL−1. The survival was calculated by doing the ratio between CFUs with AF and CFUs without AF. Experiments were performed in six biological replicates. D MBC of the 630∆erm, rsbW* and rsbWSTOP strains. MIC experiments were performed and CFUs from inoculum and wells with no visible growth were numerated. Survival was calculated by doing the ratio between the CFUs after and before treatment. Experiments were performed in four biological replicates. Geometric mean and geometric SD are shown. For survival on plate, one-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison. For MBC, Mann–Whitney tests were used. * indicates p value < 0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001 and **** <0.0001.

To identify selected mutations, we sequenced at day 30 the evolved populations, 4 replicates of the E1 strain and 3 biological replicates for the 630∆erm strain. Additionally, the replicate 3 of the E1 strain was also sequenced at day 10, corresponding to the first day when a replicate reached a MIC of 6 µg mL−1. Although several mutated genes have been identified (Supplementary Table 2), two of them were mutated in independent populations. Mutations in the rsbW gene were identified in all the 630∆erm replicates and in the third replicate of the E1 strain, both at day 10 and day 30. RsbW is the anti-sigma factor of σB, the sigma factor of the general stress response47. Three mutations were different non-synonymous point mutations at different positions of the rsbW gene. The fourth mutation was an insertion of a T at position 17 over 408 that introduces an early stop codon leading to the production of a truncated RsbW protein of 17 amino acids instead of 135. Finally, two 630∆erm replicates presented two different non-synonymous point mutations in the CD3089 gene encoding a phosphotransferase system specific for trehalose48.

Characterization of the mutations on AF susceptibility

To study the impact of the mutations in the rsbW and CD3089 genes on AF susceptibility, we constructed a CD3089::erm mutant in the 630∆erm background and we used two rsbW mutants of the 630∆erm strain obtained from the evolution experiment (Supplementary Table 2). The 630∆erm replicate 2, mentioned as the rsbW* strain, has a D37Y modification in RsbW. The 630∆erm replicate 3, mentioned as the rsbWSTOP strain, has an early stop codon in the rsbW gene but also contains a F228L mutation in the CD3089 gene. To complement the rsbWSTOP mutation, we used a plasmid carrying the rsbW gene expressed under the control of its own promoter47.

First, no differences of MIC were observed for the different mutants compared to the parental strain 630∆erm (Supplementary Table 3). Since the expression of the CD3089 gene is induced by trehalose48, we performed MIC and survival assays in presence of 10 or 100 mM of trehalose. Identical MICs were obtained for the WT strain and the CD3089::erm mutant in all the conditions tested (Supplementary Table 3), while the survival on plates containing 0.75 µg mL−1 AF was similar for these two strains in absence or in presence of trehalose (Supplementary Fig. 1A). In contrast, we observed an increased survival upon exposure to 0.75 µg mL−1 of AF for both strains containing a mutation in the rsbW gene compared to the parental strain, with a greater effect for the rsbWSTOP strain than for the rsbW* strain (Fig. 2B). Plasmid complementation of the rsbWSTOP mutant with the WT copy of the rsbW gene restored AF susceptibility (Fig. 2C). These results confirmed that mutations in the rsbW gene were responsible for increased survival to AF and suggested that the CD3089 gene is not involved in this phenotype. Finally, we performed MBC assays of the four strains (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. 1B). The rsbW* and the CD3089::erm strains had no differences of survival compared to the 630∆erm strain. However, the MBC of the rsbWSTOP was 6 µg mL−1 instead of 3 µg mL−1 for the parental strain. Altogether, our results indicated that the inactivation of rsbW, decreases AF bactericidal activity, although it does not confer resistance.

Impact of the rsbW STOP mutation on C. difficile physiology

We evaluated the impact of the rsbW mutations on key steps of the bacterium physiology. We first performed growth curves of the strains (Fig. 3A). No differences were observed between the WT and the rsbW* strain, but the rsbWSTOP strain displayed a longer lag phase and a reduced growth yield compared to the WT strain (Fig. 3A). This growth defect was exacerbated in a peptone-containing medium (Pep-M), a less rich medium (Supplementary Fig. 2A). We then assessed the sporulation efficiency of the rsbWSTOP strain (Fig. 3B). The rsbWSTOP strain produced significantly less spores after 48 h compared to the parental strain and never reached 100% of sporulation, contrary to the WT strain. Finally, we tested the production of toxins (Fig. 3C–F). The intracellular levels of TcdA and TcdB were significantly reduced in the rsbWSTOP strain compared to the parental strain (Fig. 3C, E). By contrast, the extracellular levels of toxins, although way lower than the intracellular levels, were higher in the rsbWSTOP strain (Fig. 3D, F). The increased levels of extracellular toxin are probably due to an increased lysis since more lactate dehydrogenase, a cytoplasmic protein used as lysis control, was detected in the supernatant of the rsbWSTOP strain (Fig. 3G). Consistently with the decreased total amount of toxins produced, we also observed a downregulation of the expression of the tcdA and tcdB genes by qRT-PCR in the rsbWSTOP strain, although not significant for tcdB (Fig. 3H). Since tcdR is also downregulated in the rsbWSTOP strain, we assumed that the transcriptional control of tcdA and tcdB expression by RsbW is mediated via TcdR, the specific sigma factor of tcdA and tcdB transcription49.

A Growth of the rsbW mutants. Growth of 630∆erm, rsbW* and rsbWSTOP strains was assessed by following OD600nm in 96-well plates in TY medium. Experiments were performed in five technical and three biological replicates. Mean and SD are shown. B Sporulation of the rsbWSTOP strain. Sporulation rate was evaluated by serially diluting a culture and plating before (total cells) and after (spores) ethanol shock. Sporulation rate was evaluated by calculating the ratio between spores and total CFUs. Mean and SEM are shown. C–F Toxin production. One ml of a 24 h culture was harvested and centrifuged. Supernatant was used for extracellular toxins quantification. Pellet was lysed to determine intracellular toxin levels. Sandwich ELISAs were performed to evaluate C, D TcdA and E, F TcdB concentrations in C, E intracellular and D, F extracellular fractions. Toxin amount was normalized using the OD600nm of the culture. Experiment was performed on six biological replicates. Mean and SD are shown. G Extracellular LDH in the WT strain and rsbWSTOP mutant. One ml of a 24 h culture was harvested and centrifuged. LDH present in the supernatant was quantified and normalized by the OD600nm of the culture to evaluate cell lysis. Experiment was performed on six biological replicates. Mean and SD are shown. H Expression of toxin-related genes. Expression of genes was compared by qRT-PCR between the WT and rsbWSTOP strains. Experiment was performed on five biological replicates. Mean and SD are shown. For sporulation, multiple t-tests were used to compare the rate of sporulation every day. For toxin quantification, unpaired t-tests were performed. For LDH assay, unpaired t-test was performed. For qPCR, one sample t-tests were used with comparison of the fold change to 1. * indicates p value < 0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001 and **** <0.0001.

Altogether, our results indicate that the rsbWSTOP mutation has a strong impact on C. difficile physiology with a modified growth, an increased cell lysis, a reduced sporulation efficiency, and a drop in toxin production.

Characterization of the rsbW STOP mutation

We thus wanted to dig into the mechanism of the decreased AF susceptibility of the rsbWSTOP strain. RsbW is the anti-sigma factor of σB, the sigma factor of the general stress-response47. σB controls the expression of a large set of genes involved in stress response, including the trxA1-trxB1 operon and the trxB2 gene39,50. We therefore compared the expression of the trxB genes in the rsbWSTOP and WT strains by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4A). We found that the three trxB genes were downregulated in the rsbWSTOP strain compared to the WT strain, suggesting a positive regulation by RsbW. Since trxB1 and trxB2 are transcribed from a promoter recognized by σB39,50,51 and because RsbW is the anti-σB, we expected that trxB1 and trxB2 gene expression would be upregulated in the rsbWSTOP strain. We can exclude that this unexpected result is due to a polar effect of the rsbWSTOP mutation on the sigB gene located downstream (Supplementary Fig. 2B)47 as we did not observe differences in the expression of the sigB gene in the rsbWSTOP strain compared to the WT strain (Supplementary Fig. 2C). All these data suggest that RsbW, despite being described as the anti-σB, may have another function and might also control genes that do not belong to the σB regulon such as trxB3. This hypothesis is consistent with a study performed on a ∆rsbW mutant in the R20291 strain indicating that most of the genes positively controlled by σB are not upregulated in a rsbW mutant52.

A, B Gene expression in the rsbWSTOP strain. Expression of the trxB genes (A) and of the grdA, prdB and selD genes (B) was measured by qRT-PCR in WT and rsbWSTOP strains. Experiments were performed in five biological replicates. Mean and SD are shown. C MBC of the ∆grdAB mutant. A MIC experiment was performed and CFUs from inoculum and wells with no visible growth were numerated. Survival was calculated by doing the ratio between the CFUs after and before treatment. Experiment was performed in four replicates. Geometric mean and geometric SD are shown. For qRT-PCR, one sample t-tests were used with comparison of the fold change to 1. For MBC, Mann–Whitney tests were used. * indicates p value < 0.05 and *** <0.001.

The decreased susceptibility of the rsbWSTOP strain to AF is not due to an overexpression of trxB genes. Another possible target of AF are selenoenzymes33. C. difficile selenoproteins are the Stickland enzymes PrdB and GrdA, whose synthesis relies on the selenophosphate synthetase, SelD40. In the R20291 ∆rsbW mutant, the expression of both the grd and prd operons is strongly downregulated, including the genes encoding for PrdB and GrdA52. In the rsbWSTOP strain, we found that the expression of grdA was significantly downregulated compared to the WT strain, while the rsbW mutation had no effect on the expression of the prdB or the selD gene (Fig. 4B). To see if the downregulation of grdA contributes to the tolerance of the rsbWSTOP strain, we performed an MBC assay on a ∆grdAB mutant (Fig. 4C). No differences were observed between the ∆grdAB mutant and the WT strain, suggesting that the downregulation of grdA expression alone is not sufficient to decrease AF susceptibility. However, this downregulation can explain, at least partly, the sporulation defect of rsbWSTOP strain, as grdAB has been shown to contribute to sporulation39,53.

Synergy of AF with inflammation-associated molecules

A loss of efficiency of a treatment at the infection site can also be due to inactivation of the antibiotic by molecules produced by the host or the microbiota, or by antagonistic interactions. CDI is associated with microbiota dysbiosis leading to an increase of O2-tensions in the gastrointestinal tract and with an intense inflammation leading to the production of antibacterial compounds by immune cells8,9,54,55. To evaluate the impact of such molecules on AF activity, we tested the effect of a sub-inhibitory concentration of AF (0.5 µg mL−1) in presence of different molecules of the inflamed gut (Fig. 5). Combining a sub-inhibitory dose (0.1%) of HOCl with AF (Fig. 5A) led to a complete inhibition of C. difficile growth on plates. An inhibition was also observed with DEA-NONOate, a nitric oxide (NO) donor, at 750 µM (Fig. 5B). These results confirmed that the presence of inflammation-related molecules potentializes the effect of AF on C. difficile. Compared to anaerobiosis, we observed a more drastic effect of AF at a low physiological O2-tension of 0.4%56,57 (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, when we exposed C. difficile to a lethal dose of Mtz (1.5 µg mL−1) at 0.4% O2 (Fig. 5D), we observed a decrease of the activity of Mtz. Altogether, our results suggest that in opposition to Mtz, AF activity on C. difficile is increased in presence of infection-related stress molecules.

A, B Synergy of AF with molecules produced during inflammation. Culture of 630∆erm was serially diluted and spotted on TY with or without AF 0.5 µg mL−1 and with or without A HOCl 0.1% or B DEA NONOate 750 µM. C Synergy of AF with O2 and D antagonism of Mtz and O2. Culture of 630∆erm was serially diluted and spotted in duplicate on TY Tau plates with or without AF 0.5 µg mL−1 (C) and with or without Mtz 1.5 µg mL−1 (D). Plates were incubated either in anaerobiosis or at 0.4% O2. Photos are representative of four independent biological replicates.

Effect of AF on human gut microbiota

Both CDIs and recurrences are linked to microbiota dysbiosis3,13, underlying importance to analyze the impact of C. difficile treatments on gut microbiota. The impact of AF on human gut microbiota has not been studied yet, and its spectrum of action is poorly characterized. To address these questions, we used MiPro, an in vitro microbiota model, which allows the culture of human gut microbiota in 96-well plates58. This model can allow to study the impact of molecules on the microbiota59. We evaluated the effect of three doses of AF (3 ; 30 and 300 µg mL−1 corresponding to 4; 40 and 400x the MIC) on four individual frozen biobanked fecal microbiota from healthy subjects as previously described60. Van, a C. difficile treatment known to perturbate the microbiota61, was used as a control. The dose used for Van (500 µg mL−1) corresponds to 300x to 500x the MIC62 and to fecal concentration found in patients treated four times a day with an oral dose of 125 mg following recommendations63. Such data are lacking for AF, but we tested a range of concentrations (from 3 to 300 µg mL−1) that includes the dose found in patients stools following a treatment for rheumatoid polyarthritis (5 µg mL−1)64.

After 48 h of culture, microbiota composition was analyzed by 16S sequencing. A treatment with Van significantly induced a decreased Alpha-diversity, as shown by the Shannon index (Fig. 6A), while a trend of decrease in diversity was observed with AF in a dose-dependent manner. A Spearman’s correlation (Fig. 6B) highlighted a significant negative correlation between AF doses and Alpha-diversity (Chao1 index, p value = 0.0014), indicating that AF also impacts microbiota composition.

A Alpha diversity indices (Shannon and Chao1) calculated from the raw taxonomic tables after 48 h of treatment with AF (3, 30 or 300 µg mL−1) or Van (500 µg mL−1). Kruskal–Wallis tests with Dunn’s test post hoc (Benjamini–Hochberg p value correction method) were used to compare the groups. * indicates p value < 0.05. B Spearman’s correlation of the dose of AF and Alpha-diversity indices.

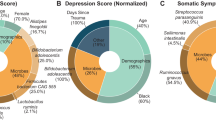

We therefore analyzed which bacteria were impacted by the various treatments (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Data). Van induced a significant decrease in abundance of Bacteroidaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Barnesiellaceae and Tannerellaceae, while AF only significantly impacted Bacteroidaceae abundance at the highest dose (Fig. 7A and Supplementary Data). However, Spearman’s correlation pointed out some effects of AF treatments (Fig. 7B). There were significant negative correlations between AF doses and abundance of Bacteroidaceae, Oscillospiraceae, Lachnospiraceae and Barnesiellaceae, suggesting that AF inhibits the growth of these organisms in the human microbiota. Moreover, a positive correlation was shown for Enterobacteriaceae, indicating that AF treatment favors their presence. Altogether, our results indicate that AF has a lesser impact on human microbiota than Van, even if it still impacts the microbiota composition.

A Relative abundance of different bacterial families after 48 h of treatment with AF (3, 30 or 300 µg mL−1) or Van (500 µg mL−1). Kruskal–Wallis tests with Dunn’s test post hoc (Benjamini–Hochberg p value correction method) were used to compare the groups. * indicates p value < 0.05, ** <0.01. B Spearman’s correlation of the dose of AF and relative abundances of bacterial families.

Discussion

In this work, we provided new elements for the use of AF as a possible treatment for CDI. AF has been demonstrated in various study to protect against CDI in animal models32,34,35. AF inhibits C. difficile growth but also sporulation and toxin production, both in vivo and in vitro32. We demonstrated that AF has a bactericidal activity on C. difficile, as observed in other bacteria28,36. In addition, we showed that the efficiency of AF on C. difficile increases in presence of infection-related metabolites such as HOCl and NO or low physiological O2 tension. These molecules are known to post-translationally modified thiols through oxidation or S-nitrosylation65,66. The TrxBs involved in thiol repair are necessary for HOCl, O2 and NO survival in C. difficile39. Thus, the likely inhibition of TrxB activity by AF, which has been demonstrated for the TrxB of M. tuberculosis and S. aureus28, probably results in an increased susceptibility of C. difficile to HOCl, O2 and NO in the presence of AF. These results suggest that AF would have an increased activity against C. difficile at the site of infection during inflammation and dysbiosis.

Consistent with a TrxB inhibition by AF, we demonstrated that a double trxB1/trxB2 mutant was more susceptible to AF. In addition, survival of a trxB1 mutant to AF at 0.75 µg mL−1 was also significantly reduced compared to the WT strain, which was not the case for the trxB2 mutant. This result needs to be confirmed, as there was no significant difference between the trxB1 and the trxB2 mutants, but it suggests that the NTR TrxB2 is slightly more susceptible to AF inhibition than TrxB1, which is a FFTR, a class of TrxB specific of anaerobes45. Some strains of C. difficile harbor a second FFTR, TrxB439. The presence of the trxB4 gene mainly found in clade 3 and clade 5 strains, did not significantly decrease susceptibility to AF. Interestingly, clade 5 strains have been demonstrated to be more tolerant to ebselen67, another TrxB inhibitor68, although the link with the presence of trxB4 has not been established.

The slight effect of the inactivation of both trxB1 and trxB2 on AF susceptibility with only a significant two-fold change in MIC and MBC, suggests that either TrxB3 compensates the inactivation of the two other enzymes, or that there are other AF targets in the cell. The other known targets in C. difficile are the selenoenzymes, GrdA and PrdB, which are crucial for C. difficile physiology42,53,69. AF disrupts selenium metabolism and the production of these selenoenzymes33. The selenium-mediated mechanism by which AF inhibits C. difficile is still unclear, as a recent study showed that mutants lacking selenoproteins were as susceptible to AF as the parental strain70. However, it is to note that only MIC assays were performed in this study, whereas we observed decreased susceptibility to AF only through MBC assays. The multiplicity of AF targets probably explains why the apparition of resistance to AF is limited in C. difficile. In S. aureus, the modified TrxB protein with G13T and G139A substitutions leads to a 512-fold increase of the MIC of AF71. However, S. aureus has a unique TrxB72 and no selenoproteins. We identified a unique mutation decreasing AF susceptibility that corresponds to the synthesis of a truncated inactivated form of RsbW, the anti-sigma factor of σB47,50. As σB controls the expression of two C. difficile trxB genes39, we first hypothesized that this tolerance was due to their derepression and thus, an increase of the amount of TrxB in the cell. However, rsbW inactivation rather decreased trxB gene expression. Another change in the rsbWSTOP mutant is a decreased expression of grdA, but we were not able to demonstrate that this downregulation was correlated with a decreased susceptibility. The mechanism involved in the decreased susceptibility to AF in the mutants inactivated for rsbW remains to be identified. In addition, we showed that the rsbWSTOP mutation strongly impacts C. difficile physiology and maybe also pathogenesis by decreasing toxin production and spore formation. These results are in agreement with a previous study on a ∆rsbW mutant in a ribotype 027 strain52. It suggests that if such a mutation appears in vivo, the pathogenesis and thus the symptoms of the infection would probably diminish, as observed in the case of Fdx resistance25. Consistently, the ∆rsbW mutant of a 027 ribotype strain is less virulent in a Galleria model of infection52.

For CDIs, the impact of a treatment on the microbiota is crucial, as it is a major risk factor of recurrence13. We evaluated the effect of AF on human gut microbiota composition using an in vitro microbiota model. We showed that AF impacts microbiota diversity in a lesser extent than Van. Interestingly, we observed an overlap between Van- and AF-impacted bacteria (Supplementary Data). This result suggests that these two molecules have a rather similar spectrum of action, even if their molecular targets in the cell are completely different73. Our in vitro microbiota experiment also provides clues on the spectrum of action of AF, which is still poorly characterized. For antibacterial purpose, AF was shown to affect several Firmicutes, Mycobacterium spp. and H. pylori28,38. Here, we demonstrated that AF decreases the abundance of the Oscillospiraceae and Lachnospiraceae Firmicutes74, confirming the general susceptibility of this phylum to AF. This molecule also impacts the abundance of two members of the Bacteroidales order, Bacteroidaceae and Barnesiellaceae75. An effect of AF on Bacteroidales has been previously demonstrated in vitro76. Interestingly, Bacteroidales, as many Firmicutes, Mycobacterium spp. and H. pylori, lack the Glutaredoxin (Grx) system77,78,79. The Grx system is an alternative system for disulfide bond exchange and thiol repair that uses glutathione, a Grx protein and a GSH-reductase80. There is a partial functional redundancy between this alternative system for thiol homeostasis and the thioredoxin system81,82,83. The Grx system is widespread in Gram-negative bacteria83, which are mostly not susceptible to AF84. Our results therefore suggest that the lack of Grx system is the reason for AF-susceptibility. This hypothesis has been proposed to explain susceptibility to ebselen, another TrxB inhibitor68, and is supported by our observation of an increase of abundance of Enterobacteriaceae in the microbiota in the presence of AF.

Altogether, our study provides new elements for the use of AF as a CDI treatment. We showed that AF likely targets the TrxBs of C. difficile in addition to the selenoenzymes of the cell33. This multiplicity of targets leads to a low rate of resistance apparition, and the only mutation that we identified decreasing AF susceptibility strongly impacts C. difficile physiology. We also demonstrated no cross-resistances nor negative interactions with the first-line treatments for CDIs. The clinical relevance of synergy assays is still debated46, but these results suggest that a dual therapy using AF and a first-line treatment should be tested in animal models, before being used in clinics if the results are conclusive. Finally, we provide new elements to identify the spectrum of AF and to characterize its impact on gut microbiota. More studies are required to characterize the impact of AF on human gut microbiota. 16S microbiota analysis, with a characterization of bacterial diversity at the family level, is a first approach. Metagenomics approaches would be a source of additional information about diversity but also functions that are lost with an AF treatment85. Assessing the effect of AF on the microbiota on human subjects would also consider the effect of the immune system, while the MiPro system that we used allows the study of human microbiota and to get rid of the effects of absorption and stomach passage.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture media

C. difficile strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 4. C. difficile strains were grown anaerobically (5% H2, 5% CO2, 90% N2) in TY (Bacto tryptone 30 g L−1, yeast extract 20 g L−1, pH 7.4), in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI; Difco), or in Pep-M (Proteose peptone No.2 40 g L−1, Na2HPO4 5 g L−1, KH2PO4 1 g L−1, NaCl 2 g L−1, MgSO4 0.1 g L−1). For solid media, agar was added to a final concentration of 17 g L−1. When necessary, thiamphenicol (Tm, 15 µg mL−1), cefoxitin (Cef, 25 µg mL−1) and erythromycin (Erm, 2.5 µg mL−1) were added to C. difficile culture. E. coli strains were grown in LB broth. When indicated, ampicillin (Amp, 100 µg mL−1) and chloramphenicol (Cm, 15 µg mL−1) were added to the culture medium. When indicated, the spore germinant taurocholate (Tau) was added in plates at 0.05%.

The MiPro culture medium was composed of 2.0 g L−1 peptone water, 2.0 g L−1 yeast extract, 0.5 g L−1 L-cysteine hydrochloride, 2 mL L−1 Tween 80, 5 mg L−1 hemin, 5 μL L−1 vitamin K1, 1.0 g L−1 NaCl, 0.4 g L−1 K2HPO4, 0.4 g L−1 KH2PO4, 0.1 g L−1 MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.1 g L−1 CaCl2 · 2H2O, 4.0 g L−1 NaHCO3, 4.0 g L−1 porcine gastric mucin, 0.25 g L−1 sodium cholate, and 0.25 g L−1 sodium chenodeoxycholate.

Construction of C. difficile strains

All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 5. The CD3089::erm mutant was obtained by using the ClosTron gene knockout system as previously described. The PCR product generated by overlap extension that can facilitate intron retargeting to CD3089 was cloned between the HindIII and BsrG1 sites of pMTL007-CE5 to obtain pDIA7274. This plasmid introduced in the HB101/RP4 E. coli strain was then transferred by conjugation into the 630∆erm strain. Transconjugants selected on BHI plates supplemented with Tm and C. difficile selective supplement (SR0096, Oxoid) were restreaked into new BHI plates containing Cef and Tm. The mutant was then selected by restreaking into BHI plates containing Cef and Erm.

For the construction of the rsbW complementation plasmid, pDIA6325, a derivative of pDIA6103 containing the promoter of the CD0007-sigB operon and the sigB gene was digested by StuI and BamHI. The rsbW gene was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides NK211 and NK212. The PCR product was cloned between the StuI and BamHI of pDIA6325 replacing the sigB gene by rsbW to produce pDIA7275. In this plasmid, the rsbW gene is expressed under the control of the promoter of the CD0007-sigB operon (Supplementary Fig. 2B). This plasmid was transferred by conjugation into the C. difficile rsbWSTOP strain.

MIC, FIC and MBC experiments

The MIC of AF was determined by broth microdilution containing 2-fold serial dilution of AF in TY medium. After inoculation with a bacterial suspension adjusted to an OD600nm of 0.05, plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in an anaerobic atmosphere. The MIC was recorded as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that inhibited visible growth of the microorganism. Experiment was performed in four biological replicates.

For MBC experiments, MIC assays were performed. The 0.05 initial inoculum was serially diluted and plated on TY agar for numeration of colony forming units (CFUs). After incubation of the MIC plate, wells with absence of visible growth were serially diluted and plated for numeration of CFUs. Survival was determined by doing the ratio between the CFUs after AF exposure and the CFUs in the inoculum. The MBC is defined as the concentration for which less than 0.1% survival is observed. Experiment was performed in four replicates.

FIC experiments were performed as MIC assays, with two gradients of 2-fold serial dilution of AF and Fdx, Van or Mtz. Experiment was performed in four replicates. The FIC index was calculated using the following formula:

Equation (1). FIC index calculation. From ref. 46.

Survival on antibiotic-containing plates

After growth, cultures were serially diluted (non-diluted to 10−5) and 5 µl of each dilution were plated on antibiotic-containing plate and on TY control plate. To test survival to AF, TY agar plates containing 0.5 or 0.75 µg mL−1 of AF were used. For synergy experiments with O2, TY Tau plates were prepared in duplicate and incubated either in anaerobiosis or in the presence of 0.4% of O2, with either 0.5 µg mL−1 of AF or 1.5 µg mL−1 of Mtz. For other synergy assays, AF was used at 0.5 µg mL−1 and DEA NONOate and HOCl were used at 750 µM and 0.1%, respectively. The experiment was performed in five replicates.

Evolution experiments

To identify spontaneous mutations increasing AF tolerance, an overnight culture of either 630∆erm or E1 strain was plated on TY containing AF at 5 or 10 µg mL−1. After 4 to 7 days, visible clones were cultured for congelation and MIC experiment. To select and identify adaptive mutations, MIC experiments of either 630∆erm or E1 strain were performed. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the MIC was recorded and the well with bacterial growth visible with the highest AF dose was diluted to perform a new MIC. The experiment was run over 30 days. Samples were frozen every 5 days.

Sequencing

DNA from evolved populations and parental strains were extracted using the NucleoSpin Microbial DNA kit (Macherey-Nagel). Strains were sequenced using Illumina with paired-end 300 bp reads by the dieresis around Plateforme Microbiologie Mutualisée (P2M—Institut Pasteur). The platform provided filtered pair-end reads, de novo assembly and annotation. Identification of SNPs was performed using breseq v0.35.786 with default parameters using filtered reads. This software allows to detect mutation relying on read mapping onto the assembled and annotated reference genomes.

Growth curves

After inoculation in an anaerobic cabinet of 96-well plates with a bacterial suspension adjusted to an OD600nm of 0.05, plates were sealed using plate sealers (R&D Systems) and growth curves were assessed by OD600nm measuring every 30 min for 24 h in the GloMax® Explorer system (Promega). The experiment was done in triplicate.

Sporulation assay

The sporulation assay was performed as previously described39. Briefly, an overday culture was used to inoculate a 5 mL culture at OD600nm of 0.05. After inoculation, and every 24 h for 4 days, total cells were numerated by serial dilution and spotting on TY + taurocholate 0.05%. Dilutions were then treated with ethanol 96% 1/1 v/v for 1 h to eliminate vegetative cells before new spotting. Percentage of sporulation was calculated by dividing the number of spores by the number of total cells. The experiment was done in five replicates.

Toxin quantification

An overday culture was used to inoculate a fresh culture at an OD600nm of 0.05. After 24 h, the OD600nm was measured and 1 mL of culture was centrifuged. Supernatant was collected and pellet was washed once in PBS before storage at −20 °C. Bacteria were then lysed through an incubation of 40 min at 37 °C in PBS in the presence of DNAse I at 12 µg mL−1 (Sigma). Sandwich ELISAs were then performed to quantify free and intracellular toxins A and B in MaxiSorp 96-wells plates (Nunc). For toxin A, PCG4.1 antibody (Biotechne) at 4 µg mL−1 was used for capture and LS-C128215 antibody (LS Bio) at 0.1 µg mL−1 antibody was used for detection. For toxin B, BM347-N4A8 antibody (BBI Solutions) at 2 µg mL−1 was used for capture, while biotinylated BM347-T4G1 antibody (BBI Solutions) at 1 µg mL−1 antibody and streptavidin-HRP (Thermo Scientific) at 125 µg mL−1 were used for detection. For revelation, the TMB substrate solution (Thermo Fisher) was used and reaction was stopped with H2SO4 at 0.2 M prior quantification through OD490nm measurement. Purified toxin A or B (Sigma) were used for the standard curve that allows toxin quantification. Results were normalized by the OD600nm of the initial culture. The experiment was done in six replicates.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Cultures of the WT strain and the rsbWSTOP strain were inoculated in TY at OD600nm 0.05 and incubated for 5 h in anaerobiosis. Pellets were resuspended in RNApro solution (MP Biomedicals) and RNA was extracted using the FastRNA Pro Blue Kit (MP Biomedicals). RNA purification was performed using the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research). cDNAs synthesis and real-time quantitative PCR were performed as previously described87,88. In each sample, the quantity of cDNAs of a gene was normalized to the quantity of cDNAs of the gyrA gene. The relative change in gene expression was recorded as the ratio of normalized target concentrations (the threshold cycle ΔΔCt method)89. Experiment was performed in five biological replicates.

Statistical analysis

For survival on plate, one-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison. For MBC, Mann–Whitney tests were used. To compare MIC distribution between trxB4 positive and negative strains, a Mann–Whitney test was used. To compare MIC evolution between strain, a two-way ANOVA was performed. For sporulation, multiple t-tests were used to compare the rate of sporulation every day. For toxin quantification, unpaired t-tests were performed. For LDH assay, unpaired t-test was performed. For qPCR, one sample t-tests were used with comparison of the fold change to 1. Figures and statistical analysis were performed using the GraphPad Prism (version 10.1.1).

MiPro

Approval for human stool collection was obtained from the local ethics committee (Comité de Protection de Personnes Ile de France IV, IRB00003835 Suivitheque study; registration no. 2012/05NICB). Human stool collection, preparation, storage and MiPro set up were done as previously described58,60. Briefly, four healthy male volunteers were recruited for stool sample collection. Approximately 8 g of fresh stools were collected from the volunteers, immediately transferred to anaerobic workstation and then homogenized in 20 mL pre-reduced deoxygenated preservation buffer (10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1% (w/v) L-cysteine hydrochloride in PBS) in 50 mL sterile conical centrifuge tubes. Prior to usage, the preservation buffer was stored in an anaerobic workstation (5% H2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2) overnight before use. Additional pre-reduced deoxygenated preservation buffer was added make a 20% (w/v) fecal slurry. The mixture was filtered using sterile gauzes to remove large particles, aliquot and stored at −80 °C.

The culture medium was equilibrated in an anaerobic workstation overnight before use. Frozen fecal slurry was thawed at 37 °C with thorough shaking prior to inoculation and diluted at 2% in MiPro medium. AF diluted in DMSO was added at a final concentration of 3, 30 or 300 µg mL−1 and DMSO was added as vehicle control at the same volume of AF. Van diluted in DMSO was added at a final concentration of 500 µg mL−1. The plate was covered with vented sterile silicone mats and shaken at 500 rpm at 37 °C for 48 h in the anaerobic workstation. At 24 and 48 h, cultures were centrifuged, and pellets were used for DNA extraction.

16S analysis

Fecal DNA extraction was performed as previously described90. Gut microbiota composition and diversity were determined using 16S sequencing. Following PCR, amplicon quality was verified by gel electrophoresis and sent to the @BRIDGe platform for sequencing protocol on an Illumina MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

The size of the sequenced pair-end libraries ranged from 33,739 bp to 112,325 bp, representing a total of over 2.6 million 250 bp reads. Reads were processed through Qiime2 (version 2020.8.0)91: low-quality reads and sequencing adapters were removed using Cutadapt92, and sequencing errors were corrected with Dada293 using custom parameters (--p-trunc-len-f 230 --p-trunc-len-r 220). Taxonomic assignation of resulted ASVs was done using SILVA trained database (version 138-99)94 based on scikit-learn’s naïve Bayes algorithm95. Results were deep analyzed with the Phyloseq package (version 1.34.0)96 as for the analysis of taxonomic and alpha diversity. Statistical analyses were performed using rstatix (version 0.7)97 and figures were plotted using the ggplot2 package (version 3.3.5)98. Spearman rank correlation analyses were conducted to associate auranofin treatment and microbiota features using the R package rstatix (version 0.7.2). Multivariable association between microbial community abundance and treatment was examined with MaAsLin299.

Data availability

The GenBank accession number for the sequences of the evolution experiment is PRJNA1047340. The GenBank accession number for the sequences of the 16S sequencing experiment is PRJNA1083456.

References

Smits, W. K., Lyras, D., Lacy, D. B., Wilcox, M. H. & Kuijper, E. J. Clostridium difficile infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2, 16020 (2016).

Schäffler, H. & Breitrück, A. Clostridium difficile—from colonization to infection. Front. Microbiol. 9, 646 (2018).

Theriot, C. M. et al. Antibiotic-induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat. Commun. 5, 3114 (2014).

Couturier, J., Davies, K. & Barbut, F. Ribotypes and new virulent strains across Europe. in Updates on Clostridioides difficile in Europe (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Vol. 1435) (eds Mastrantonio, P. & Rupnik, M.) 151–168 (Springer International Publishing, 2024).

Awad, M. M., Johanesen, P. A., Carter, G. P., Rose, E. & Lyras, D. Clostridium difficile virulence factors: insights into an anaerobic spore-forming pathogen. Gut Microbes 5, 579–593 (2014).

Aktories, K., Schwan, C. & Jank, T. Clostridium difficile toxin biology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 71, 281–307 (2017).

Kuehne, S. A. et al. The role of toxin A and toxin B in Clostridium difficile infection. Nature 467, 711–713 (2010).

Abt, M. C., McKenney, P. T. & Pamer, E. G. Clostridium difficile colitis: pathogenesis and host defence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 609–620 (2016).

Naz, F. & Petri, W. A. Host immunity and immunization strategies for Clostridioides difficile infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 36, e00157-22 (2023).

Aktories, K., Papatheodorou, P. & Schwan, C. Binary Clostridium difficile toxin (CDT)—a virulence factor disturbing the cytoskeleton. Anaerobe 53, 21–29 (2018).

Barbut, F. et al. Clinical features of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea due to binary toxin (actin-specific ADP-ribosyltransferase)-producing strains. J. Med. Microbiol 54, 181–185 (2005).

Kelly, C. P. Can we identify patients at high risk of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 21–27 (2012).

Song, J. H. & Kim, Y. S. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: risk factors, treatment, and prevention. Gut Liver 13, 16–24 (2019).

Meza-Torres, J., Auria, E., Dupuy, B. & Tremblay, Y. D. N. Wolf in sheep’s clothing: Clostridioides difficile biofilm as a reservoir for recurrent infections. Microorganisms 9, 1922 (2021).

Rubio-Mendoza, D., Martínez-Meléndez, A., Maldonado-Garza, H. J., Córdova-Fletes, C. & Garza-González, E. Review of the impact of biofilm formation on recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Microorganisms 11, 2525 (2023).

van Prehn, J. et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: 2021 update on the treatment guidance document for Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27, S1–S21 (2021).

European Centre for Disease prevention and Control. Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infections—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2016–2017. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/clostridiodes-difficile-infections-annual-epidemiological-report-2016-2017 (2022).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), 2019).

Di Bella, S. et al. Clostridioides difficile infection: history, epidemiology, risk factors, prevention, clinical manifestations, treatment, and future options. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 37, e00135-23 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Cost-effectiveness of bezlotoxumab and fidaxomicin for initial Clostridioides difficile infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27, 1448–1454 (2021).

Wynn, A. B., Beyer, G., Richards, M. & Ennis, L. A. Procedure, screening, and cost of fecal microbiota transplantation. Cureus 15, e35116 (2023).

Louie, T. J. et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 422–431 (2011).

Minkoff, N. Z. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile (Clostridium difficile). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, CD013871 (2023).

Schwanbeck, J. et al. Characterization of a clinical Clostridioides difficile isolate with markedly reduced fidaxomicin susceptibility and a V1143D mutation in rpoB. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74, 6–10 (2019).

Marchandin, H. et al. In vivo emergence of a still uncommon resistance to fidaxomicin in the urgent antimicrobial resistance threat Clostridioides difficile. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 78, 1992–1999 (2023).

Wilcox, M. H. et al. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 305–317 (2017).

Suarez-Almazor, M. E., Spooner, C., Belseck, E. & Shea, B. Auranofin versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2000, CD002048 (2000).

Harbut, M. B. et al. Auranofin exerts broad-spectrum bactericidal activities by targeting thiol-redox homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 4453–4458 (2015).

AbdelKhalek, A., Abutaleb, N. S., Mohammad, H. & Seleem, M. N. Antibacterial and antivirulence activities of auranofin against Clostridium difficile. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 53, 54–62 (2019).

Owings, J. P. et al. Auranofin and N-heterocyclic carbene gold-analogs are potent inhibitors of the bacteria Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 363, fnw148 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Repurposing of the gold drug auranofin and a review of its derivatives as antibacterial therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 27, 1961–1973 (2022).

Hutton, M. L. et al. Repurposing auranofin as a Clostridioides difficile therapeutic. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 409–417 (2019).

Jackson-Rosario, S. et al. Auranofin disrupts selenium metabolism in Clostridium difficile by forming a stable Au-Se adduct. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 14, 507–519 (2009).

Abutaleb, N. S. & Seleem, M. N. Auranofin, at clinically achievable dose, protects mice and prevents recurrence from Clostridioides difficile infection. Sci. Rep. 10, 7701 (2020).

Abutaleb, N. S. & Seleem, M. N. In vivo efficacy of auranofin in a hamster model of Clostridioides difficile infection. Sci. Rep. 11, 7093 (2021).

Ruth, M. M. et al. Auranofin activity exposes thioredoxin reductase as a viable drug target in Mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, e00449-19 (2019).

Elkashif, A. & Seleem, M. N. Investigation of auranofin and gold-containing analogues antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sci. Rep. 10, 5602 (2020).

AbdelKhalek, A., Abutaleb, N. S., Elmagarmid, K. A. & Seleem, M. N. Repurposing auranofin as an intestinal decolonizing agent for vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Sci. Rep. 8, 8353 (2018).

Anjou, C. et al. The multiplicity of thioredoxin systems meets the specific lifestyles of Clostridia. PLoS Pathog. 20, e1012001 (2024).

McAllister, K. N., Bouillaut, L., Kahn, J. N., Self, W. T. & Sorg, J. A. Using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing to generate C. difficile mutants defective in selenoproteins synthesis. Sci. Rep. 7, 14672 (2017).

Andreesen, J. R. Glycine metabolism in anaerobes. Antonie Van. Leeuwenhoek 66, 223–237 (1994).

Johnstone, M. A. & Self, W. T. d-Proline reductase underlies proline-dependent growth of Clostridioides difficile. J. Bacteriol. 0, e00229-22 (2022).

Pavao, A. et al. Reconsidering the in vivo functions of Clostridial Stickland amino acid fermentations. Anaerobe 76, 102600 (2022).

Andreesen, J. R. Glycine reductase mechanism. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 8, 454–461 (2004).

Buey, R. M. et al. Ferredoxin-linked flavoenzyme defines a family of pyridine nucleotide-independent thioredoxin reductases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12967–12972 (2018).

Doern, C. D. When does 2 plus 2 equal 5? A review of antimicrobial synergy testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 4124–4128 (2014).

Kint, N. et al. The σB signalling activation pathway in the enteropathogen Clostridioides difficile. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 2852–2870 (2019).

Norsigian, C. J. et al. Systems biology analysis of the Clostridioides difficile core-genome contextualizes microenvironmental evolutionary pressures leading to genotypic and phenotypic divergence. Npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 6, 31 (2020).

Chandra, H., Sorg, J. A., Hassett, D. J. & Sun, X. Regulatory transcription factors of Clostridioides difficile pathogenesis with a focus on toxin regulation. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 49, 334–349 (2023).

Kint, N. et al. The alternative sigma factor σB plays a crucial role in adaptive strategies of Clostridium difficile during gut infection: role of σB in stress adaptation in C. difficile. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 1933–1958 (2017).

Soutourina, O. et al. Genome-wide transcription start site mapping and promoter assignments to a sigma factor in the human enteropathogen Clostridioides difficile. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1939 (2020).

Cheng, J. K. J. et al. Regulatory role of anti-sigma factor RsbW in Clostridioides difficile stress response, persistence, and infection. J. Bacteriol. 205, e00466-22 (2023).

Rizvi, A. et al. Glycine fermentation by C. difficile promotes virulence and spore formation, and is induced by host cathelicidin. Infect. Immun. 91, e00319-23 (2023).

Sinha, S. R. et al. Dysbiosis-induced secondary bile acid deficiency promotes intestinal inflammation. Cell Host Microbe 27, 659–670.e5 (2020).

Byndloss, M. X. et al. Microbiota-activated PPAR-γ-signaling inhibits dysbiotic Enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science 357, 570–575 (2017).

Kint, N. et al. How the anaerobic enteropathogen Clostridioides difficile tolerates low O2 tensions. mBio 11, e01559-20 (2020).

Kint, N., Morvan, C. & Martin-Verstraete, I. Oxygen response and tolerance mechanisms in Clostridioides difficile. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 65, 175–182 (2022).

Li, L. et al. An in vitro model maintaining taxon-specific functional activities of the gut microbiome. Nat. Commun. 10, 4146 (2019).

Li, L. et al. Berberine and its structural analogs have differing effects on functional profiles of individual gut microbiomes. Gut Microbes 11, 1348–1361 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Evaluating live microbiota biobanking using an ex vivo microbiome assay and metaproteomics. Gut Microbes 14, 2035658 (2022).

Sunwoo, J. et al. Impact of vancomycin‐induced changes in the intestinal microbiota on the pharmacokinetics of simvastatin. Clin. Transl. Sci. 13, 752–760 (2020).

Dubois, T. et al. A microbiota-generated bile salt induces biofilm formation in Clostridium difficile. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 5, 14 (2019).

Gonzales, M. et al. Faecal pharmacokinetics of orally administered vancomycin in patients with suspected Clostridium difficile infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 10, 363 (2010).

Capparelli, E. V., Bricker-Ford, R., Rogers, M. J., McKerrow, J. H. & Reed, S. L. Phase I clinical trial results of auranofin, a novel antiparasitic agent. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61 https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01947-16 (2016).

Cole, J. A. Anaerobic bacterial response to nitrosative stress. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 72, 193–237 (2018).

Poole, L. B. The basics of thiols and cysteines in redox biology and chemistry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 80, 148–157 (2015).

Marreddy, R. K. R., Olaitan, A. O., May, J. N., Dong, M. & Hurdle J. G. Ebselen not only inhibits Clostridioides difficile toxins but displays redox-associated cellular killing. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e00448-21 (2021).

Lu, J. et al. Inhibition of bacterial thioredoxin reductase: an antibiotic mechanism targeting bacteria lacking glutathione. FASEB J. 27, 1394–1403 (2013).

McAllister, K. N., Martinez Aguirre, A. & Sorg, J. A. The selenophosphate synthetase gene, selD, is important for Clostridioides difficile physiology. J. Bacteriol. 203, e00008-21 (2021).

Johnstone, M. A., Holman, M. A. & Self, W. T. Inhibition of selenoprotein synthesis is not the mechanism by which auranofin inhibits growth of Clostridioides difficile. Sci. Rep. 13, 14733 (2023).

Chen, H., Liu, Y., Liu, Z. & Li, J. Mutation in trxB leads to auranofin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 22, 135–136 (2020).

Uziel, O., Borovok, I., Schreiber, R., Cohen, G. & Aharonowitz, Y. Transcriptional regulation of the Staphylococcus aureus thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase genes in response to oxygen and disulfide stress. J. Bacteriol. 186, 326–334 (2004).

Stogios, P. J. & Savchenko, A. Molecular mechanisms of vancomycin resistance. Protein Sci. 29, 654–669 (2020).

Taib, N. et al. Genome-wide analysis of the Firmicutes illuminates the diderm/monoderm transition. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1661–1672 (2020).

Maus, I. et al. The role of petrimonas mucosa ING2-E5AT in mesophilic biogas reactor systems as deduced from multiomics analyses. Microorganisms 8, 2024 (2020).

Maier, L. et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 555, 623–628 (2018).

Rocha, E. R., Tzianabos, A. O. & Smith, C. J. Thioredoxin reductase is essential for thiol/disulfide redox control and oxidative stress survival of the anaerobe bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8015–8023 (2007).

Szczepanowski, P. et al. HP1021 is a redox switch protein identified in Helicobacter pylori. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 6863–6879 (2021).

Newton, G. L. et al. Distribution of thiols in microorganisms: mycothiol is a major thiol in most actinomycetes. J. Bacteriol. 178, 1990–1995 (1996).

Ogata, F. T., Branco, V., Vale, F. F. & Coppo, L. Glutaredoxin: discovery, redox defense and much more. Redox Biol. 43, 101975 (2021).

Holmgren, A. Hydrogen donor system for Escherichia coli ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase dependent upon glutathione. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73, 2275–2279 (1976).

Aslund, F., Ehn, B., Miranda-Vizuete, A., Pueyo, C. & Holmgren, A. Two additional glutaredoxins exist in Escherichia coli: glutaredoxin 3 is a hydrogen donor for ribonucleotide reductase in a thioredoxin/glutaredoxin 1 double mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 9813–9817 (1994).

Meyer, Y., Buchanan, B. B., Vignols, F. & Reichheld, J. P. Thioredoxins and glutaredoxins: unifying elements in redox biology. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 335–367 (2009).

Feng, X. et al. Synergistic activity of colistin combined with auranofin against colistin-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 12, 676414 (2021).

Wensel, C. R., Pluznick, J. L., Salzberg, S. L. & Sears, C. L. Next-generation sequencing: insights to advance clinical investigations of the microbiome. J. Clin. Invest. 132, e154944 (2022).

Deatherage, D. E. & Barrick, J. E. Identification of mutations in laboratory evolved microbes from next-generation sequencing data using breseq. Methods Mol. Biol. 1151, 165–188 (2014).

Saujet, L., Monot, M., Dupuy, B., Soutourina, O. & Martin-Verstraete, I. The key sigma factor of transition phase, SigH, controls sporulation, metabolism, and virulence factor expression in Clostridium difficile▿. J. Bacteriol. 193, 3186–3196 (2011).

Soutourina, O. A. et al. Genome-wide identification of regulatory RNAs in the human pathogen Clostridium difficile. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003493 (2013).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Lamas, B. et al. CARD9 impacts colitis by altering gut microbiota metabolism of tryptophan into aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands. Nat. Med. 22, 598–605 (2016).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Kassambara, A. rstatix: pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rstatix/index.html (2023).

Wickham, H. et al. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (2016).

Mallick, H. et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009442 (2021).

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. eucast: Clinical breakpoints and dosing of antibiotics. https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (grant numbers ECO202006011710 and FDT202304016494) and by the Institut Pasteur for the funding of the PhD contract of C.A. and by the Institut Universitaire de France for I.M.-V. The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript. We thank Laure Diancourt for her help with the sequencing of the strains, Elena Capuzzo for her experimental help, Marie-Noelle Rossignol and Kassandra Alexis-Alphonse (Plateforme @BRIDGe, INRAe) for 16S sequencing, and Harry Sokol for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.M.V. and C.A. designed the research. I.M.V. and C.M. supervised experimental work and I.M.V., C.A., M.R., E.B. and L.C. performed the experiments. N.R., I.A.S. and M.B. performed the MiPro experiment and the 16S analysis. J.L. analyzed the WGS of evolved strains. B.D. and F.B. provided material. I.M.V. and C.A. wrote the manuscript, and all authors reviewed it. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anjou, C., Royer, M., Bertrand, É. et al. Adaptation mechanisms of Clostridioides difficile to auranofin and its impact on human gut microbiota. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 10, 86 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00551-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00551-3