Abstract

Biofilm proliferation in confined environments is a challenge in biomedical, industrial, and space applications. Surfaces in contact with fluids experience varying bulk stresses due to flow and gravity, factors often overlooked in biofilm studies. This research quantifies the combined effect of gravity and shear stress on Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 motility and biofilm growth. Using a rectangular-section microfluidic channel under laminar flow, we compared top and bottom surfaces, where gravity either pulls bacteria away or pushes them toward the surface. Results revealed an asymmetric bacterial distribution, leading to varying surface cell densities and contamination levels. We also analyzed spatial reorganization over time and classified bacterial motility under flow. Findings show that external mechanical stresses influence both motility and biofilm morphology, impacting biocontamination patterns based on shear stress and gravity direction. This study provides insights into biofilm control strategies in diverse environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biofilms are consortia of microorganisms that colonize interfaces through a self-synthesized soft gel, mainly made of polysaccharides, eDNA, and proteins, generally called extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs)1. Biofilm plays a key role in the ubiquitarian microbial success across all ecological niches2. Due to its resilience, biofilm constitutes a risk in a wide spectrum of applications, ranging from food contamination, medical devices, and industrial implants corrosion1,3,4. Biofilm resistance to chemical compounds usually employed for surface detergency, and antibiotics poses a challenge for its removal process, greatly increasing costs and efforts5,6. Moreover, microbial growth on solid surfaces can significantly compromise the lifespan and integrity of systems and equipment, including heat exchangers, and water/air recycling systems7,8. Its growth can directly damage tubes, brackets, and surfaces by using them as carbon and nitrogen sources9 or can indirectly alter systems functionality due to biofouling phenomena10. While biofilms are often associated with negative implications, it is worth mentioning that their formation can also have beneficial applications in wastewater treatment11, and as plant growth promoter (in association with plant roots) by enhancing nutrient uptake and providing protection against pathogens.

Evidence of biofilm formation was also found beyond planet Earth, aboard the International Space Station (ISS) in a peculiar microgravity environment4,7,12,13,14,15. This enclosed space inadvertently triggers ideal conditions for microbial growth15,16,17,18, posing an issue to both human health and equipment functionality. On several occasions, for example, biofilm caused loss of functionality in the Water Processor Assembly (WPA), a facility that produces potable water from a combination of humidity condensate and urine distillate on the ISS7,14,19. The WPA consists of a wastewater tank connected to the Mostly Liquid Separator (MLS) and a succession of downstream plants for water recycling20,21. Peristaltic pumps were periodically activated to initialize the recycling process, but several biofouling problems on solenoid valves (parts of the MLS) occurred, causing a subsequentially component substitution7,14,21. This is an example of an interface between a flowing liquid and solid surfaces22, which is frequently encountered in biomedical and industrial applications. Such interfaces occur in confined environments where typically two sources of stress coexist, namely bulk stresses (also related to gravity), and flow-induced stresses such as shear flow.

Microbial growth and biofilm formation in microgravity conditions are well documented13,14,18, but still unclear, with controversial hypothesis in the literature behind the role of gravity on bacterial growth and biofilm spatial organization. Benoit and Klaus investigated the role of microgravity on biofilm shaping in liquid environment and hypothesized a correlation with bacteria motility23,24. Their theory suggests an indirect role of microgravity due to the lack of gravity-induced liquid convection and sedimentation. Both phenomena are commonly experienced on Earth, but absent or severely modified in space. Experiments demonstrate a stronger effect of microgravity on non-motile bacteria in comparison to motile ones18.

Under normal gravity, non-motile microbial cells tend to sink, experiencing low shear forces during the sedimentation process, after which they accumulate at the bottom of the suspension. In contrast, under microgravity conditions, gravity-dependent forces are significantly reduced, altering the microenvironment around non-motile cells. In these quiescent conditions, nutrient availability may increase due to a more uniform cell distribution, but the local accumulation of toxic metabolic by-products can also occur. The former would intuitively support growth, while the latter may have inhibitory effects.

Unlike non-motile cells, motile bacteria rely less on gravity-driven sedimentation to influence their environment. Through the action of their flagellar machinery, they actively induce local mixing and fluid convection. However, the strength of the induced flow decays rapidly with distance, proportional to the inverse square of the radius from the cell25. This limits the spatial extent of mixing in dilute suspensions. In moderately dense bacterial suspensions, however, collective behaviors can generate transient vortices and jets that extend beyond individual cell scales26. Therefore, although the hydrodynamic influence exerted by bacterial flagella is limited to a short range, the overall distribution of motile bacteria remains less affected by gravitational conditions. Their ability to self-propel and actively interact with their microenvironment allows them to maintain controlled spatial behavior even under microgravity17.

However, following Benoit and Klaus' hypothesis, bacterial motility is often described as an on/off behaviour, flattening potential differences between bacterial trajectories in various situations. To the best of our knowledge, this aspect has always been overlooked, potentially hiding an effect of gravity on motile microbial behaviour. To quantify bacterial motility, an approach based on the Persistent Random Walk (PRW) theory is adopted in this work. Motility can be characterized by using a mathematical approach first proposed by Tranquillo et al. 27. According to the PRW theory, cell motility is a stochastic process that can be fully described in analogy with a Brownian motion27,28,29,30 through representative diffusion coefficient. Trajectories were described as a succession of uncorrelated movements of duration equal to a characteristic time called persistence time27. Fitting the mean-squared displacement (MSD) of cells trajectories with PRW equation cell motility can be described with two key parameters: motility coefficient μ (analogous to diffusion coefficient, able to describe cell mass flow on a long time scale) and persistence time P (the time cells move in the same direction)27.

In line with the hypothesis of motility as a key parameter to explain biofilm differences in microgravity in comparison to normal gravity, Kim et al.18, discovered a correlation between P. aeruginosa motility and biofilm morphology, investigating microorganism swimming behaviour through the employment of motility deficient mutant in normal and microgravity conditions. In normal gravity, under flow conditions, defined as hydrodynamic regime, they observed “mushroom-like” biofilm structures, while “flat” biofilm structures were observed in stagnant conditions. In microgravity conditions, in an experiment run on the ISS, they observed a unique “column and canopy” biofilm in stagnant conditions and not the expected “flat” structures, underpinning a role of gravity also on motile bacteria. The same experiments repeated in the case of motility-deficient mutants proved that flagella-driven motility plays a key role in the formation of both “mushroom” and “column and canopy” morphologies18.

The effect of gravity on biofilm morphology can be hypothesized to affect bacterial spatial organization directly due to different bulk forces interplay with cells (in analogy with Benoit and Klaus' theory23) or indirectly due to an internal bacterial response to gravity. This second statement can be explained taking into account a mechanosensing system responsive to gravity31,32. As a reprove of this kind of system, P. aeruginosa biofilm exhibit a slightly different gene expression on spaceflight in comparison to biofilm growth on Earth18,19,33.

Recent studies clearly suggest genetic heterogeneity, in the case of B. subtilis, severely affects gene expression, depending on spatial localization within biofilm structure34,35, supporting also the idea of a different genetic pattern activation in the same confined environment due to local different physical and chemical stimuli. Chemical (such as nutrient depletion or concentration gradients36,37) or mechanical (such as flow induced38,39,40) stresses are the main inducers of biofilm formation. Flow conditions and in particular, shear stress affect biofilm morphology and mechanical properties38,41. As mentioned before, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, flagellar motility is one of the key factors required for the formation of the characteristic “mushroom-shaped” biofilm structure18,42. In addition, filamentous networks composed of extracellular DNA (eDNA) and cells have been observed under specific flow conditions, which are thought to induce their formation43,44. Chlorella vulgaris biofilm growth in flow exhibits an enhanced resistance to erosion45.

While comparisons between microgravity and normal gravity conditions are commonly found in the literature for bacteria and biofilm growth in stagnant conditions, the role of hydrodynamics in altered gravity conditions is still unexplored46. It is worth mentioning the relevance of this aspect goes beyond the space-related application and has a wide potential impact in standard “on Earth” conditions. Indeed, the interaction between bacteria and a solid surface under flow, where submerged biofilm typically develops, for example, inside flow channels, always faces different roles of gravity. In the case of top channel surfaces, the gravity force essentially pulls bacteria away from the substrate. Conversely, the interaction between bacteria and the bottom surface is somewhat enhanced by the direction of gravity, which pushes bacteria towards the substrate. Intermediate conditions can be found in the case of tilted or vertical walls47. To the best of our knowledge, this aspect, despite being relevant from the scientific and technological point of view, was never investigated systematically.

In this work, we investigated the impacts of gravity vector direction on Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 cell motility and biofilm morphology through flow-visualization experiments, by comparing the top and the bottom wall of a microfluidic channel. We select the monotrichous bacterium P. fluorescens as a model organism due to previous swimming motility studies performed by Ping et al.48. We chose a motile strain to understand the effect of gravity on bacterial motility, a key parameter in biofilm formation18. We also employed the PRW to estimate bacterial motility coefficient and persistence time at different channel heights. We quantified those parameters for different wall shear stresses, comparing top and bottom surfaces. Biofilm morphology at surfaces was also characterized and quantified at Confocal Microscopy to find a connection between bacterial swimming behaviour and biofilm morphology.

Results prove an asymmetric bacterial motility and biofilm growth in the channel driven by gravity and reinforced with an increased shear stress.

Results

In stagnant conditions, bacteria undergo an asymmetrical wall accumulation process due to gravity vector

The initial stage of the biofilm growth experiment involved a 2 h stagnant phase (no flow) in the microfluidic apparatus depicted in Fig. 1, to allow P. fluorescens SBW25 attachment to the surfaces.

a The system is composed by a syringe pump, a commercial microfluidic channel (z = 0.4 mm, x = 17 mm, and y = 3.8 mm), and a tank of collection; details about components are reported in the method section. Bacterial were inoculated in stagnant conditions for 2 h before initiating flow imposing a fixed flow rate by the syringe pump. b The cartoon reports the microfluidic channel where sample was imaged in bright field time lapse at five different focal planes: channel bottom wall z1 (0 μm), z2 (100 μm), half-height channel z3 (200 μm), z4 (300 μm), channel top wall z5 (400 μm). CLSM z stack were acquired after sample staining, at the end of each experiment for bottom and top walls.

After inoculation, P. fluorescens planktonic population can be divided into two categories: motile cells and non-motile cells (including damaged or dead cells). We identified and quantified these two sub-populations by analysis of bright field time-lapse microscopy. Non-motile bacteria were identified by averaging a sequence of 200 frames, acquired with a frame rate of 8.78 fps, and subtracted from the images, to obtain a time series with motile cells only.

The analysis was repeated along 5 different z positions within the microfluidic channel, as reported in Fig. 1b. Non-motile cells detected at the two solid-liquid interfaces with a stable interaction with the surfaces of the channel were considered as sessile cells, basically attached to the surfaces.

Quantification of cell subpopulations density was repeated over time during the 2 h of inoculum in Fig. 2c. In Fig. 2b, we presented the density of motile and sessile bacteria at the initial inoculum time and after 2 hours of stagnant conditions at the 5 z positions considered. At the beginning of the experiment (0 h), motile bacteria were evenly distributed across the channel height (light green bars in Fig. 2b). At the end of the stagnant phase (2 h), both categories of motile and non-motile cells accumulated at the channel surfaces, as it shown in Fig. 2a. However, this accumulation was not symmetric between the top and bottom surfaces, with sessile bacteria being more concentrated at the bottom surface, respect to the top.

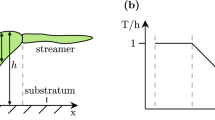

a Illustration of bacterial spatial distribution in the microfluidic channel. Motile bacteria, in green, experience a trapping effect at channel walls due to the boundary layer effect, while non-motile bacteria, in yellow, slowly sediment at the bottom of the channel. We reported as Lz the characteristic depth of the layer where cell experience the trapping effect, and we distinguished the different diffusivity coefficient near the wall and in the middle of the channel. b Spatial distribution of bacterial density at inoculum and after 2 h in stagnant conditions in a microfluidic channel. The x-axis represents bacterial density in number per square millimetre, while the height is measured relative to reference points in the microfluidic channel. The maximum height (400 μm) corresponds to the top layer z5, and 0 μm represents the bottom layer z1. Motile bacteria are depicted in green, appearing light at time 0 and dark after 2 h. Non-motile bacteria on the surface are shown in yellow, appearing light at time 0 and dark after 2 h. c Temporal evolution of bacterial density over 0 to 2 h corresponding to the layers visualized in graph A. Accumulation of bacteria is observed at the surfaces of the layers, while a depletion is noticeable in the middle layers of the channel.

We explain this spatial evolution over time by the simultaneous action of three phenomena: sedimentation, which inexorably drives bacteria downwards; self-propelled forces that move bacteria with a vector dependent on the direction of their movement; and the adhesion of motile bacteria at interfaces leading to an increase in sessile population (resulting to the first step of biofilm formation). Comparing the concentration of motile and sessile sub-populations, we can assess that after 2 hours the asymmetry of the system is totally driven by gravity due to the sedimentation of non-motile cells, as is visible by the dark yellow in Fig. 2b. Considering the motile bacterial population alone, their ability to self-propel allows them to overcome gravitational forces. However, due to the nature of their flagellar-driven motion, these cells tend to accumulate near boundaries, leading to the formation of dense populations at both the top and bottom interfaces. This phenomenon finds explanation due to hydrodynamic interactions, leading to swimmers' stable trajectories in a finite region parallel to a surfaces49,50. The ability of motile cells to overcome gravity vector is not absolute, as the heterogeneity of the cell population also includes less motile cells that may be more affected by gravity than other, however, due to the symmetrical distribution in our experimental campaign we consider this aspect negligible.

Bacterial boundary attraction was already verified for E. coli51, and was explained as the results of geometrical cell parameters following the model proposed by Shum et al.49. We reported the transitory phase leading of this accumulation in Fig. 2c were, in a 400 μm depth channel, a stationary density of motile bacteria can be achieved after 50 min. As can be seen in Fig. 2c, motile density between top and bottom channels was not affected by gravity vector. However, Zheng et al.50 proves that this statement can became false in high media density, when buoyancy can overcome motile bacteria symmetrical distribution and push cells upwards. It is worth noting that, in addition to causing an asymmetrical distribution, increased buoyancy also has the secondary effect of reducing the overall mean motility velocity of the bacterial population, as reported in the same study.

Motile bacteria distribution is driven by a slow diffusivity region near surfaces

Bacterial density and spatial distribution can provide useful information to estimate quantitative swimming parameters. As described by Berke et al.52, swimming cells, especially monotrichous bacteria, can be approximated to a force dipole where flagella motion and drag force compete with each other. Near a wall, bacterial cells confined between two parallel surfaces have a velocity in the direction z, orthogonal to the surfaces, given by:

Where, H is the maximum distance between the two parallel surfaces (in our case 400 μm), p is the dipole strength, η is the viscosity of suspending medium, and z is the distance from the surface. Dipole strength can be estimated as p = f·l where f is cells thrust force, experimentally obtained by Ping et al.48 as 1.1 pN for P. fluorescens SBW25 and l bacterial minor axis, measured to be about 1 μm. This equation can be used to describe cells advection to the boundaries. The balance equation between cells advection and diffusion along channel height z, in a region near boundaries can be written as follows:

Where, n(z) refers to cell probability distribution across the channel, and Dz is the diffusion coefficient in the region near the wall. Coupling Eq. 1 and Eq. 2 and integrating (a graphical representation is reported in Supplementary Figure 1), it is possible to calculate an analytical solution for a steady state concentration profile52:

Where \({L}_{z}=\frac{3p}{64\pi \eta {D}_{z}}\) is a characteristic size, representing the thickness of the region near the wall where cells experience an attraction to the surfaces. In this region bacteria diffuse on z-axis with Dz coefficient.

We fitted Eq. 3 to steady-state bacterial concentration profile. Data were an extension on the ones reported in Fig. 2c, assuming a steady state, values after 50 min from inoculation. It is worth mentioning that this model accounts only for hydrodynamic interactions between the cell body and the surrounding fluid, disregarding any physical or chemical interactions between bacteria and wall surfaces. For this reason, the model remains valid for distances higher than 10 μm from the wall. Below this distance, other forces become relevant, and experimental data points were discarded from the fit.

From the fitting (reported in supplementary materials, Supplementary Fig. 1) we obtained Lz and \({n}_{0}\) values, and so we finally estimated Dz coefficient which is equal to 0.57 μm2/s. This diffusivity coefficient is referred to the small region of height Lz near the walls, however, this parameter must not be confused to the coefficient of cell diffusivity along z-axis outside this boundary. This second coefficient is expected to be higher of approximately two orders of magnitude in comparison to previous as will be later discussed in the text.

Flow setup validation and directional velocity analysis of bacterial cells

After 2 h of stagnant conditions, we started flow, injecting sterile media in the microfluidic channel. We imposed different flow rates Q using the syringe pumps, corresponding to different values of wall shear rates \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) and shear stress \({\tau }_{w}\), as reported in Table 1.

It is worth mentioning that in all flow conditions investigated for motility purposes, medium velocity at a distance equal to Lz from the wall never exceeded bacterial maximum velocity estimated as 102 μm/s for P. fluorescens SBW25 by Ping et al.48, in agreement with our measurements. We acquired bacterial trajectories, as described in Materials and Methods. Images were taken before activating the flow, in stagnant conditions, and 24, 48 h after flow initiation. Images were taken at five different z positions, as described in Fig. 1. We performed a preliminary experimental campaign to assess the optimal choice of the planar position (xy).

A preliminary test of the experimental setup was run using 2 μm polystyrene microparticles as trackers. Microparticles trajectories were acquired for the aforementioned flow conditions at different channel y and z positions (fixing x position at 8.5 mm, corresponding to the half-length of the channel). We estimated the velocity profile in a rectangular channel according to Cornish et al.53 where the local flow is described as follows:

While the volumetric flow rate is:

\(\frac{{dp}}{{dx}}\) is eliminated as follows:

where η = viscosity; p = pressure; b = half-width; n = counter; δ = half-height. In Fig. 3a, we report the theoretical flow velocities obtained using Eq. 6 along the zy plane under steady-state conditions. The illustration highlights the impact of confinements walls on flow velocity, with velocities peaking at the centre of the channel and decreasing towards the walls along the z-axis. Additionally, the side walls contribute to a secondary effect, as evident in the gradual decrease of flow velocity along y direction. According to Fig. 3a, we estimated a region along y-axis of ±1200 μm from the channel centre, where the side walls effect can be considered negligible. In this region flow was prevalently affected by z confinement only, while is reasonably constant along y. To experimentally validate those predictions, we compared microparticles velocity (blue dots) with the expected theoretical values (black lines) in Fig. 3b, c. Detailed representations of particle raw data and volumetric flow rate estimations are reported in supplementary materials (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

a Contour plots representing the theoretical velocity profiles calculated using the Cornish equation53. Each row corresponds to a different shear rate value indicated by the black lines headers, while the colour legend is provided on the left side. b Average velocity values calculated fixing the y position at 0 μm at the centre of the channel where lateral wall effect on flow is negligible. The theoretical values are represented with the continuous black line, microparticles velocities are in blue, and bacterial velocities at various time points are represented by histograms. c Velocity of average cell displacement along the x-flow direction. Data are reported with the same legend of column b. d Velocity of average cell displacement in the direction orthogonal to the flow. Data are reported with the same legend of column b.

At the end of this investigation, we identified a region along xy plane (x = 8.5 mm and y = ±400 μm from y centre of the channel) used to image bacterial cells motility at the different z and flow conditions.

In Fig. 3b, we report the average absolute values of bacterial velocities. For all \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\), bacterial velocities at the walls are higher compared to both the theoretical profile and the experimental validation with microparticles, which is consistent with the intrinsic movement of bacteria27. Conversely, at central z positions, bacterial cells have velocities comparable to values predicted and to the case of microparticles, for slow flows. Above \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) = 1 s−1, bacterial cells have lower velocities at the centre of the channel respect to microparticles and theory. This progressive reduction in velocity, ~−50 μm/s for \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) = 1.67 s−1 and −100 μm/s for \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) = 3 s−1, can be attributed to flagellar orientation and tentative to swim against flow. Measurement was repeated at different experimental times, reported with different colours in the histograms in Fig. 3b, no significant change was observed between 0 h and 72 h.

We further refined the analysis by examining the x and y components of average velocity, along the x-axis, the flow direction (Fig. 3c), and along the y-axis, orthogonal to the flow direction (Fig. 3d). Concerning velocity along the x-axis, results mirror what already described for velocity moduli, reported in Fig. 3b, except at the walls where the net displacement velocity is ~0 μm/s. This indicates that displacements along the flow are counteracted by those against the flow when bacteria are in wall proximity.

In the y direction, orthogonal to the flow, velocities are smaller and fluctuate around 0 μm/s, as expected due to the absence of a preferential direction.

All velocity components measured here resulted to be symmetrical between top and bottom walls, showing no preference between positive and negative z direction, where gravity is present.

Gravity-driven sedimentation induces asymmetry in motility coefficients between top and bottom channel walls

We run a detailed investigation on bacterial displacement, focusing our analysis on trajectories observed at the top and bottom walls of the channel (layers 1 and 5 along z, as reported in Fig. 1). We identified an heterogeneous range of behaviours, consistent with previous findings on monothricous bacteria at interfaces54.

We identified cells exhibiting predominantly ballistic motion (see Supplementary Movie 1). These cells move exclusively in the flow direction, with a speed strongly influenced by the drag force induced by the flow, as discussed in the previous paragraph. It is important to note that this ballistic motion is entirely flow-induced rather than a result of self-motility. Consequently, both non-motile cells, passively transported by the fluid, and motile cells, whose orientation is overridden by the strong flow, can exhibit this behaviour. Cells are classified as ballistic if, throughout the entire observation period, each step of their movement occurs in the flow direction (positive x direction) without inversion. A limited number of ballistic trajectories are observed near the channel walls, where fluid velocity reaches its minimum, whereas ballistic motion represents most bacterial trajectories in the presence of flow at the other investigated distances (100, 200, and 300 µm).

Near the wall, other types of trajectories are possible. P. fluorescens SBW25 cells can associate with a single pole to the surface, mainly exhibiting pirouette trajectories (see Supplementary Movie 2), In this case bacterial cell body quickly rotate with a pole fixed in a defined position. This behaviour can be related to rotating flagella partially attached to the surfaces, transferring torsion to cell body54 due to momentum conservation.

Bacteria can also remain in the same position, fluctuating in place. This behaviour can be observed at negligible flow velocities (e.g., only near the wall during flow experiments) or throughout the entire channel height under stagnant conditions. We define this type of behaviour as passive diffusion, where bacterial movement follows a diffusion process like that of colloidal particles. In this case, bacterial motion is entirely driven by thermal fluctuations and fluid interactions, resulting in purely Brownian diffusion52. Unlike motile bacteria, which can actively navigate their environment, passive diffusive bacteria do not exert self-propulsion. In P. fluorescens, this occurs when bacteria lack flagella, are metabolically inactive, or are in highly viscous environments where active motility is suppressed. Over our observation period (typically 30 s), these bacteria appear essentially non-motile.

Another category of trajectories we observed is represented by the active diffusive bacteria. This class consists of bacteria with self-propelled behaviour (compatible with swimming motility) that exhibit an active diffusion. We described those active diffusive bacteria according to the Persistent Random Walk theory27, where their Mean Square Displacement is described by a motility coefficient (due to their flagellar motion) analogous to the Fickian diffusion coefficient. However, the random pattern of bacterial swimming cells is strictly dependent on the chosen species and strains55. The most studied case is the well-documented peritrichous E. coli56,57 that swims with a “run and tumble” pattern. In this case, cells alternate movements in one direction (run) with moments of rearrangement and starting off in another random direction (tumble), without prioritizing any specific direction (in a free gradient environment). However, in our case, P. fluorescens SBW25 exhibits another peculiar movement pattern called “run and reverse” (see Supplementary Movie 4), much more similar to P. aeruginosa or marine bacteria55. In our specific case P. fluorescens strain exhibited a sophisticated swimming behaviour composed by alternating “run” phases, where cells exhibit fine tuning only, while swimming always in the roughly same direction, and “reverse” phases when cells show abrupt, almost 180° inversion. Physiological explanation of this motility mode is related to cyclic inversions in flagella rotational verse. Fine tuning, variations, and fluctuations around the 180° reverse, and differences in velocity between run and reverse phase result in a zig-zag trajectory that, on a time scale long enough, can be described in agreement with a diffusive regime according to an equation modelled by Villa-Torrealba et al 58.

Other types of active trajectories are observed in tight surface proximity and dilute conditions (in situations where cells are isolated), where bacteria's movement is represented by the Curly Path trajectories (see Supplementary Movie 3). In this case, we observed curvilinear translation due to hydrodynamic interactions between swimming bacteria and surfaces. Interpretation of this phenomena is well documented and modelled in the literature54.

“Run and reverse” and “Curly Path” trajectories are the prevalent motion behaviours on a surface, can be described on a long time scale according to an active diffusive behaviour, and are heavily affected by cell density in a crowded environment (such as in our wall conditions). More specifically, trajectories become more random, with a reduction in persistent times and stronger direction changes, due to interactions with stationary obstacles (such as adhered bacteria) and other motile bacteria.

In our analysis, we excluded pirouettes, ballistic, and passive diffusive trajectories as described in supplementary (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1) and analysed in detail motility of active diffusive bacteria. Selected trajectories on top and bottom channel walls were analysed independently and compared. Cell trajectories were analysed following the work of Tranquillo et al.27. According to the model proposed, where cells' mean squared displacements are given by the following equation.

Where \({n}_{d}\) in the number of the dimensions, that in our case is 2, since we only considered planar movement of the cells. We fitted Eq. 7 to cell Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) to quantify the motility coefficient μ (analogous to the Fickian diffusion coefficient D, see Fig. 4) and the persistence time P (see Supplementary Fig. 5), the time in which a cell persists in the same direction.

Motility coefficient μ, analogous to Fick’s diffusion coefficient, calculated for the bottom (in black) and top (in red) surfaces of the microfluidic channel at various flow hours. Each row represents different shear rate values imposed. a The first column reports isotropic motility coefficient, calculated according to Eq. 7. b Analysis of the same trajectories as plotted in column A, focusing on the MSD along the x-axis (flow direction) only. c Analysis of the same trajectories as plotted in column A, considering the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) along the y-axis (orthogonal to the flow direction) only.

To further investigate the contribution of the flow on bacteria motion, we reiterated this analysis, distinguishing between motion along x-direction parallel to the flow, and motion along y-direction orthogonal to the flow.

As evident from the trajectory analysis reported in Fig. 4, the motility coefficient of bacteria at the top wall (in red) is higher than that of bacteria at the bottom wall (in black). This observation holds true for both the two-dimensional analysis of trajectories (Fig. 4a) and the separation of movements along the flow direction (Fig. 4b) from those orthogonal to the flow (Fig. 4c). This discrepancy persists both before flow activation (0 h) and after 24 and 48 h of flow.

This difference in motility arises from the varying number of bacteria (bacterial surface density), which, in the case of the bottom wall, overcrowds the environment, thereby hampering motility.

To further explore this relationship, we quantified the motility coefficient μ as a function of surface cell concentration (cells/mm²) for both the top and bottom walls (Fig. 5). The data reveal a clear decreasing trend in motility with increasing surface density, confirming that overcrowding reduces bacterial movement. This effect is more pronounced at the bottom wall, where gravity-driven sedimentation leads to higher non-motile bacterial accumulation. Based on data from Fig. 2, surface densities after two hours of stagnant conditions are estimated to be ~5.7 × 104 and 7.2 × 104 cells/mm² for the top and bottom surfaces, respectively. These values are indicated in Fig. 5 as vertical dashed grey lines. Notably, the values of μ obtained here are in excellent agreement with those reported in Fig. 4 under isotropic conditions (0 h of flow), further supporting the robustness and consistency of our analysis.

Relationship between bacterial motility (μ\muμ) and surface cell concentration (cells/mm²) for the top (red) and bottom (black) walls of the microfluidic channel. A decreasing trend in motility is observed as cell density increases, confirming that overcrowding hampers bacterial movement. This effect is more pronounced at the bottom wall, where gravity-driven sedimentation results in higher local cell accumulation. Dashed vertical grey lines indicate the estimated surface cell densities after 2 h under stagnant conditions.

These findings confirm an asymmetry in bacterial motility between the top and bottom walls of the microfluidic channel, with higher motility consistently observed at the top wall, for any flow conditions. Gravity indirectly affects bacterial motility by altering the spatial distribution of cells near surfaces. In particular, it preferentially concentrates non-motile cells at the bottom wall, increasing local density and hindering the movement of actively motile bacteria. This establishes a clear, indirect link between gravity and bacterial swimming behavior.

Regarding flow, as the wall shear rate value increases, isotropic motility increases for both the top and bottom walls. However, as evident from the comparison of values in Fig. 4b, c, this increase is entirely attributed to the increment along flow direction (as intuitively expected). This occurs due to a greater drag effect experienced by bacterial cells as the shear rate value increases. The same analysis was also conducted for persistence times, as reported in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Fig. 5), with no clear trend.

Biofilm under flow conditions exhibits asymmetrical growth between top and bottom walls due to gravity

The results achieved from the investigation previously described led to the hypothesis that shear and bulk stress not only directly influence bacterial motility, but also on biofilm growth38. After 48 h of flow conditions, we evaluated biofilm growth at the top and bottom solid-liquid interfaces through Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) coupled with live/dead staining (see Materials and Methods). Experiments were conducted with the same experimental set-up used before, reported in Fig. 1, but only the bottom and the top wall layers were visualized, since the focus of the experiment was on biofilm growth at solid-liquid interface. Flow conditions investigated are summarized in Table 1.

In Fig. 6, we qualitatively report biofilm structures obtained under different flow conditions, comparing top and bottom walls of the channel. As described in methods section, we acquired z stacks on top and bottom layers after 48 h of growth, with live-dead staining. In green (Syto9) are visualized live cells, in red (Propidium Iodide) dead or damaged cells, however, in red are also visible traces of extracellular DNA (see Supplementary Fig. 6). In Fig. 6, 3D reconstruction (Paraview) of biofilm on top and bottom channel walls are compared for 5 different flow conditions (\({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 1.67 s−1 as reported in Supplementary Fig. 7 for the sake of brevity), with a colour map representing biofilm thickness. Representative images of top and bottom layers are also reported. Mushroom-like structures are visible (Supplementary Movie 5), and streamers structures are reported in supplementary (Supplementary Fig. 6). This morphology is in accordance with Pseudomonas biofilm shapes under flow for other strains18. Images were analysed with BiofilmQ to measure morphology parameters, such as Biovolume and coverage fraction, reported in the charts. Experiments were repeated in biological triplicate, each sample was imaged in 3 different positions with a 2 × 2 z-stack mosaic scanning. Box plots in the charts represent the statistical variance of the measurements.

a The top row displays 3D reconstructions obtained in Paraview from z-stack images of the biofilm grown at various investigated shear rates (\({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 1.67 was omitted), colorimetric scale bar depicting biofilm thickness in μm was reported on the left. In the second raw images of a single field of view depicting the biofilm growth on the top surface. In the third row, images of biofilm growth at the bottom surface. b Biovolume (μm³/μm²) of the biofilm measured at the top (in blue) and bottom (in red) walls as a function of shear rate (\({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\), s⁻¹). Box plots illustrate the statistical distribution of biovolume values, showing an increase in biofilm growth with shear rate up to \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 10 s⁻¹, followed by a decrease at higher shear rates. Biofilm growth is more pronounced on the bottom wall compared to the top. c Substratum coverage (A.U.) at the top (in blue) and bottom (in red) walls as a function of shear rate (\({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\), s⁻¹). Substratum coverage follows a similar trend to biovolume, increasing with shear rate up to \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 1 s⁻¹ before decreasing. The bottom surface exhibits a higher biofilm coverage than the top surface, indicating an asymmetrical biofilm development influenced by gravity.

Results show how flow heavily affects biofilm growth. Particularly, under low stress conditions, up to \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 10 s−1, flow enhances biofilm formation, as visible by the increase in biofilm thickness and biovolume with shear rate. For example, at \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 0.4 and \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 1 s−1, surfaces are poorly colonized by a bacterial monolayer or small clusters of 4-5 bacterial cells adhered to surfaces. Moreover, these structures exhibit a higher degree of death cells (in red). Faster flows lead to a biofilm progression to mushroom-shaped structures, up to carpet-like structures with fungal protrusions towards the centre of the channel, widely visible in the case of \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 10 s−1. This increase is visible on both surfaces but appears accentuated on the lower surfaces, especially for high \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) values. From still faster flows, we observe instead a decrease in biofilm growth, as evident comparing the case of \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 10 s−1 and \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) 30 s−1. This result is in agreement with the work of Wei et al.59, who reported a decrease in biofilm thickness on side walls of a rectangular channel, in a stress range spanning from \({10}^{-3}\) Pa to \(1\) Pa, corresponding in our setup to \({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) > 10 s−1.

It is worth mentioning, the decrease we observed is stronger on top surfaces, with respect to the case of bottom walls, resulting in an asymmetrical biofilm growth between the two surfaces and proving gravity vector has a key role on biofilm development at solid-liquid interfaces under flow.

Discussion

In this work, we investigated the often overlooked influence of the gravitational vector on bacterial motility and biofilm formation through direct visualization. We used bright-field microscopy for motility analysis and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) for morphological assessment. Different flow conditions were investigated to verify the interplay between gravity and shear stress on motility and biofilm formation.

Our results show that the monotrichous bacteria Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25, in a three-dimensional and confined environment such as our microfluidic channel, accumulate at the channel walls.

(I) In the case of motile cells, this accumulation results from hydrodynamic interactions between bacteria and flat surfaces, which induce a reorientation of swimming cells parallel to the surfaces and an attraction of cells toward the nearest wall. We compared the top and bottom walls of the channel, reporting both the transient and steady-state population profiles. We observed a symmetrical bacterial distribution between these two surfaces, and from the steady-state profile, we estimated a region Lz = 29.1 μm near the walls where cells accumulate and swim along trajectories nearly parallel to the surfaces. Inside these two regions, bacterial movement along the Z-axis of the channel was estimated to be Dz equal to 0.57 μm²/s, two orders of magnitude lower than the surface parallel motility coefficient, and was consistent with a passive diffusion mechanism.

(II) In the case of non-motile cells, bacteria can irreversibly attach to surfaces via appendages or remain free-floating, eventually sinking due to gravity and primarily accumulating at the bottom wall of the channel. Non-motility can arise for various reasons, including senescence, mutations, or transient states in which flagellar genes are not transcribed, or the flagellum is damaged. Some of these cells may still retain the ability to form or become incorporated into existing biofilm structures. However, this capacity is hampered, as observed in recent works18.

Merging the two subpopulations, we observed that bacterial accumulation becomes asymmetrical, with a higher concentration of cells at the bottom. This discrepancy, entirely driven by non-motile cells, is caused by sedimentation and introduces a bias in cell density between the two surfaces.

We investigate the impact of this bias on bacterial cell motility by analyzing 2D bacterial trajectories in the region where cells predominantly swim parallel to the walls and comparing top and bottom walls. We quantified the two-dimensional motility coefficient (Dxy) using the Persistent Random Walk model, obtaining values on the order of 10² μm²/s. In this region, we neglected bacterial motion along the z-axis and focused exclusively on cells actively swimming via flagellar motility in the plane parallel to the wall. Non-motile cells and those not displaying clear flagellar-driven motion were excluded from the analysis. Only trajectories lasting at least 3 s were considered.

Bacteria exhibit a higher motility rate at the top surface, approximately twice that observed at the bottom, underling that gravity-driven sedimentation has an indirect role on bacterial motility due to the different cell densities. This asymmetry persists both under stagnant conditions and in flow for up to 48 h.

Furthermore, we analyzed the influence of this bias on the subsequent biofilm growth across a wide range of shear stresses. Generally, we observed that increasing shear stress leads to increased biofilm formation. This trend reverses beyond a critical stress value, where further increases of stress result in a less biofilm volume.

However, comparing top and bottom walls, we observed that biovolume is not symmetrically developed between the two walls. Gravity induces anisotropy due to the aforementioned bias, and as a consequence, we quantified a higher biovolume and substratum coverage at the bottom wall, compared to the top one.

Our results represent a systematic investigation of the combined role of gravity and flow on bacteria motility and subsequent biofilm development. We placed emphasis on the role of gravity, providing an analysis based on the entire cell population and not focused on local environment or subpopulations. The impact of this work will be relevant for the fundamental understanding of the influence of bulk and flow-related stress on bacterial contamination in confined environments, a wide range of applications, including also design of flow device for human deep space explorations.

Methods

Bacterial strain and media

Biofilm experiments were performed by using Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 strain48,60, gently provided by Dr. Romain Briandet, INRAE. Frozen −80 C° glycerol stock solution 25% (v/v) was plated on LB agar (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl, 15 g/L agar, bi-distilled water) and incubated overnight at 28 °C. Single colony was picked and resuspended in minimal media (6.8 g/L of Na2HPO4, 3 g/L of KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L of NaCl, and 1 g/L NH4Cl, 0.24 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.04 g/L CaCl2·2H2O, 0.05 g/L EDTA, 8.3 mg/L FeCl3, 0.84 mg/L ZnCl2, 0.1 mg/L CuCl2·2 H2O, 0.1 mg/L CoCl2·2H2O, 0.1 mg/L H3BO3, and 0.016 mg/L MnCl2·4 H2O supplemented with 0.4% succinic acid, at pH 7), and incubated in shaken conditions (90 rpm) until optical density OD600nm ≈ 0.3, was achieved.

In-flow experimental setup and biofilm growth conditions

Bacterial suspension was first inoculated under laminar hood in a rectangular cross-section commercial microfluidic channel (Ibidi Cell in Focus, µ-Slide VI 0.4 untreated) with the following dimensions: 0.4 mm, 17 mm, 3.8 mm (height z, length x, width y). Subsequently, channel inlet was connected by silicone tube and connectors (Ibidi Elbow luer male connector) to a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Pump 33DDS) equipped with 60 mL BD plastic syringe, while the outlet was connected to a waste. Sterile syringes and tubes were previously filled with minimal medium. Two three-way valves were placed in the system. The first between syringe pump and channel inlet, and the second between channel outlet and the waste. A scheme of the experimental setup and flow chamber is reported in Fig. 1.

By closing valves, we impose an initial phase of stagnant conditions to guarantee an initial bacterial adhesion to the top and bottom walls of the channel. Inoculum was left in stagnant conditions for 2 h. After the adhesion phase, both valves were opened, and syringe pump was activated, flowing sterile minimal media through the chamber. Biofilm was left growing in hydrodynamic conditions for 48 h.

The role of flow intensity was investigated by imposing different volumetric flow rates Q, obtained by setting the inlet syringe pump. The flow rate for a given channel geometry corresponds to different values of wall shear rates \(\dot{\gamma }\), that is, the effective local measurement of kinematic flow intensity: \(\dot{\gamma }=\frac{3\cdot Q}{(2\cdot {\delta }^{2}\cdot W)}\), where δ and W are respectively the half height and the width of the channel. In our experimental campaign, we investigated six different values of \(\dot{\gamma }\) (0.4, 1.0, 1.67, 3.0, 10.0, 30.0 s−1). For each flow condition, Reynolds numbers were calculated to assure the laminar regime of the chosen wall shear rate. The estimation was performed following the equation: \(\mathrm{Re}=\frac{\rho \cdot \upsilon \cdot {D}_{h}}{\eta }\), with \({D}_{h}=\frac{4A}{P}=\frac{4\left(W\cdot \delta \right)}{W+\delta }\). The experimental apparatus was kept at 28 C° to facilitate P. fluorescens growth and avoid bubble formation. A visual inspection was conducted, and experiments where evident bubbles occurred were discarded.

To verify that top and bottom walls of the microfluidic channel do not influence biofilm morphology, we repeated one flow condition \((\dot{\gamma }={3\,{\rm{s}}}^{-1})\) with the channel placed upside down. The results confirmed no significant differences and are presented in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Time-lapse imaging

We recorded bright field videos using a time-lapse microscopy automated workstation, based on an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and a 32x objective, equipped with a motorized stage and focus system (Märzhäuser Wetzlar) for automated sample position. Imaging was performed by using a CCD video camera (Orca AG; Hamamatsu, Japan), which provides grey scale images at defined frame rates. Sensor binning was changed (1 × 1 or 2 × 2) to optimize planar resolution and camera frame rate. Videos were obtained by merging time-lapse images.

A preliminary campaign was conducted by flowing 2 μm polystyrene microparticles in the experimental setup to verify the parabolic flow velocity profile inside the channel, as expected. Samples were imaged in a fixed length position, more precisely at the half length of the channel x = 8.5 mm. 20 fields of view were acquired along chamber width y at five different z heights each, as reported in the scheme in Fig. 1. For every position, 250 frames were acquired at frame rate of 16.37 fps. To measure a complete velocity profile, for each flow condition, 100 videos were analysed.

For P. fluorescens SBW25 experiments, stagnant conditions videos were taken at 8.78 fps (binning 1 × 1) with a conversion of 0.19 μm/px to ensure a precise count of bacteria and an optimal estimation of their dimension. Images were taken in one x, y position (centre of the channel) for all 5 z planes as reported in Fig. 1, at defined times: 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, 80, and 120 min after the inoculation. Subsequentially, in-flow conditions videos were recorded at 16.37 fps. Images were taken by using the same z planes at defined times: 0, 24, and 48 h after the end of stagnant conditions.

Images segmentation and bacteria count

We analysed time-lapse videos using Image-Pro Plus v6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). All videos were processed to binarize images, separating bacterial cells or microparticles from the background. We created a custom macro for segmentation. Images were averaged to obtain a background image to subtract background noise and identify motionless bacterial cells or microparticles. A flatten filter was then applied to further reduce background noise.

The subsequent counting operation in our macro automatically identifies objects with a different grey value with respect to the background. Specifically, we applied a threshold for object dimensions and pixel intensity. For our investigation, we selected objects with an area dimension of 0.72 μm² and a pixel intensity ranging from white to the 10% tail of the Gaussian distribution of the pixel scale in the images. Further details and examples of image processing are reported Fig. 7.

a Single frame from a processed video. Starting from the raw video (250 frames), the image processing procedure is outlined. Following the described steps, a background image was subtracted from the raw video, and several morphological filters were applied to enhance cell visibility: a sharpening filter (3 × 3), high Gaussian filtering (7 × 7), and a rank filter (3 × 3, 50%). The resulting image is shown. b Average Image. Average image of the processed videos, representing sessile/non-motile cells. The resulting image reports cells that remain in a fixed position over all video duration. c) Single frame from a video including only motile cells. Motile bacteria are identified by subtracting the average image (Panel b) from the processed videos. The resulting motile videos reveal only actively moving cells. Tracking algorithm representation. Example of a bacterial cell tracking was the research area between the first and second frames is described by the yellow circle. Iterating this procedure, the trajectories is acquired over time. Numerical parameters are described in the Materials and Methods section.

Major and minor axes of each object identified were also calculated as key parameters of bacterial morphology. These operations were applied only to video taken at z1 (bottom surfaces) and z5 (top surfaces), where interaction between wall and bacteria occurs.

Bacteria and microparticle trajectories acquisition

We created a dedicated macro for the semi-automatic tracking of bacterial cells and microparticles in recorded videos using the Image-Pro Plus plug-in Track Object. The videos were segmented through the following algorithm: We estimated a background image by averaging images, previously filtered using a flatten filter (bright background); background subtraction allowed to remove stationary bacteria from the segmented source videos. Sharpen filter followed by rank filter were used to enhance bacterial edges, segment images, identify bacteria position, and measure trajectories. We applied a threshold for object dimensions (bacteria and microparticles) and pixel intensity as described in the case of sessile bacteria count.

The coordinates (X, Y) of an object in each frame were determined by calculating the centroid of the area of the object itself. The tracking operation involves starting from the initial frame and identifying a circular search area for each individual object. As the sequence progresses to the next frame, the algorithm checks if an object falls within its respective search area. If an object is found within this area in the subsequent frame, it is determined to be the same object as in the previous frame, indicating its movement across frames. This iterative process allows for the tracking of objects as they translate (due to swimming behaviour in the case of bacteria) from one frame to the next one.

We calibrated the circular search area by establishing a search radius of 18 pixels. The video frame rate is 16.37 fps, and the resolution is 0.38 μm/px. Multiplying these factors, we determined a search radius to track motile objects with a maximum speed of 114 μm/s. This value is slightly above the reported maximum velocity P. fluorescens SBW25, which is equal to 102.0 μm/s, as documented by Ping et al.48. Additionally, we filtered out trajectories with a duration less than 3 s or a length less than 19 μm. We analysed videos consisting of 250 frames, resulting in a total track duration of 15.3 s. Since bacteria move in and out of the field of view during recording, multiple bacteria tracks were recorded to describe bacterial motility behaviour. For trajectories quantification, at least 70 trajectories were considered to guarantee statistical significance (see Supplementary material, Supplementary Fig. 8).

Mathematical model and trajectories analysis

To estimate quantitative bacterial cell motility parameters, trajectories were processed by a self-made MATLAB© script, used to calculate the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) as function of migration time \(\tau\). For each cell trajectory, several non-overlapping intervals27,28,61 of size \(\tau\) were identified, and the squared displacement was estimated for each interval by calculating the Euclidean distance between bacterial position at the beginning and at the end of the interval. MSD corresponding to an interval of size \(\tau\), was then calculated as the average of all the measurements taken for each cell, along the same time lapse imaging, and for all the different cells present in the sample. This process was iterated for different values of \(\tau\), the minimal size considered was the time between two consecutive frames acquisition (i.e., 1/9 or 1/16 s, depending on the acquisition modes); the maximum size measurable was the entire time acquisition. However, it is worth mentioning that small values of \(\tau\) correspond to higher numbers of independent measurements, while largest value of \(\tau\) correspond to a poorer dataset. For this reason, in order to guarantee statistical significance to our data, even if raw data allowed to measure MSD corresponding to the entire time acquisition of 20 s, we limited our analysis to a maximum value of 3 s, corresponding to about 50 frames, that is the longer trajectory length considered in our fit.

The analysis of cell motility was based on PRW theory27,56, developed by Ornstein and Uhlenbeck30, and subsequently extended for the motility studies of active particles, eukaryotic cells27,28,62, and bacteria58,63.

In this model, it is assumed that cell motion is characterized by a diffusion coefficient (known as random motility coefficient) μ (μm2/s) and a persistence time P (s) between cell directional changes. The value of μ is a quantitative measurement of cell migration and is related to both the average speed of cells and the persistence time through the following relationship: μ ~V2P. According to Tranquillo et al.27, the mean squared displacement is given by Eq. 7.

It is worth mentioning that both the MSD obtained from bacterial trajectories and the motility coefficient (μ) fitted with the mathematical model are purely two-dimensional (xy-plane). This approach is well suited for our investigation, as the consecutive 50-frame displacements observed with a system featuring a small depth of field (3.15 μm) can be approximated as occurring within a plane for bacterial cells. In this way, we aimed to study bacterial motility parallel to the walls (top and bottom).

Moreover, along the z-axis near the wall (in the Lz region), motility in the z direction is significantly hindered (by approximately two orders of magnitude) and is characterized by the Dz value presented in the Results section. For this reason, we chose to distinguish the two-dimensional motility coefficient parallel to the wall (μ) from the Dz diffusive/motility coefficient.

The presence of flow induces an anisotropy in cell motility, which is characterized by different persistence times and random motility coefficients along two orthogonal axes, e.g., x (parallel to the flow direction) and y (orthogonal to the flow). In this case, we set \({n}_{d}\) equal to 1 and we obtained values for P and μ along the x and y directions.

CLSM acquisition and analysis

Biofilm was grown in the microfluidic channel at different values of wall shear rates (\({\dot{\gamma }}_{w}\) = 0.4 s−1, 1.0 s−1, 1.67 s−1, 3.0 s−1, 10.0 s−1, 30.0 s−1) corresponding to different wall shear stress (\({\tau }_{w}\): 0.38\(\cdot\)10−3 Pa, 0.95\(\cdot\)10−3 Pa, 1.59\(\cdot\)10−3 Pa, 2.86\(\cdot\)10−3 Pa, 9.53\(\cdot\)10−3 Pa, 28.60\(\cdot\)10−3 Pa). After 48 h, flow was stopped, sample was placed in a dark room, and 200 μL of staining solution was loaded into the channel. The staining solution was prepared by adding 3 μL of SYTO9 and 3 μL of propidium iodide in 1 mL of distilled water. After 30 min at room temperature, the sample was analysed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 5 Pascal, Zeiss) equipped with a helium/neon laser (LASOS Lasertechnik GmbH, LGK SAN7460A). Experimental observations were performed with a Plan Apo λ 63 X/1.49 NA oil-objective and a Nikon digital camera, with a standard field of view of 1024 pixels x 1024 pixels, corresponding to 142.855 μm × 142.855 μm. Excitation was provided at a wavelength of 488.6 nm using a detection filter of 498 nm and at a wavelength of 561.5 nm with a detection filter of 580 nm. 3D Images were acquired applying a 2 × 2 tie scan combined with Z-stacks along the biofilm thickness using a 0.6 μm interval between consecutive layers.

Due to the steric hindrance caused by the proximity of the channel connectors and the large diameter of the oil-immersion objective, combined with the limited working distance of the 63X, 1.49 NA objective, it was not possible to acquire images from both the top and bottom walls of the channel in a single experimental setup. To overcome this limitation, two separate experimental campaigns were performed. In the first, the channel was used in its standard orientation (connectors facing downward), allowing for the acquisition of biofilm images from the bottom wall. For imaging the top wall, a second dedicated campaign was carried out in which the channel was placed upside down immediately after inoculation and maintained in this orientation throughout the entire 48-hour growth period. This allowed direct optical access to the top surface without the need to image through the full channel depth.

Image processing was performed for each single field of view acquired using BiofilmQ through MATLAB©64. BiofilmQ allows the analysis of Z-stack images by denoising and segmenting images with customized settings and by declumping into voxels of preferred dimensions. Single-cell voxel analyses are performed to obtain several parameters. Settings for denoising were chosen according to Bridier et al.65: convolution kernel size xy = 5, z = 3; medium filter along Z selected; top-hat filtering with size 25 voxels (3.49 μm). Segmentation was performed with the Otsu method with 3 classes, with class 2 assigned to background and a sensitivity of 0.4 (sensitivity was chosen by comparing different image analyses with different values), and objects were declumped with cube size of 10 voxels (1.40 μm cube side length). The segmented image was processed by removing small clusters of less than 1000 voxels (2.72 μm3) to avoid the presence of single or pairs of bacteria. Both green (live) and red (dead) channels were processed, and after segmentation, the two channels were merged. We selected biofilm thickness, biovolume, and substratum coverage as useful parameters.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Hall-Stoodley, L., Costerton, J. W. & Stoodley, P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 95–108 (2004).

Azeredo, J. et al. Critical review on biofilm methods. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 43, 313–351 (2017).

Høiby, N. et al. ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of biofilm infections 2014. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 21, S1–S25 (2015).

Novikova, N. D. Review of the knowledge of microbial contamination of the Russian manned spacecraft. Microb. Ecol. 47, 127–132 (2004).

Penesyan, A., Paulsen, I. T., Gillings, M. R., Kjelleberg, S. & Manefield, M. J. Secondary effects of antibiotics on microbial biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 11, 2109 (2020).

Tixador, R. et al. Behavior of bacteria and antibiotics under space conditions. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 65, 551–556 (1994).

Zea, L. et al. Design of a spaceflight biofilm experiment. Acta Astronautica 148, 294–300 (2018).

Stoodley, P., Lewandowski, Z., Boyle, J. D. & Lappin-Scott, H. M. Structural deformation of bacterial biofilms caused by short-term fluctuations in fluid shear: an in situ investigation of biofilm rheology. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 65, 83–92 (1999).

Mansour, R. & Elshafei, A. M. Role of microorganisms in corrosion induction and prevention. Br. Biotechnol. J. 14, 1–11 (2016).

Flemming, H.-C. Biofouling and me: my Stockholm syndrome with biofilms. Water Res. 173, 115576 (2020).

Feng, L., Wu, Z. & Yu, X. Quorum sensing in water and wastewater treatment biofilms. J. Environ. Biol. 34, 437–444 (2013).

Bruce, R. J., Ott, C. M., Skuratov, V. M. & Pierson, D. L. Microbial surveillance of potable water sources of the International Space Station. SAE Trans. 114, 283–292 (2005).

Marra, D. et al. Migration of surface-associated microbial communities in spaceflight habitats. Biofilm 5, 100109 (2023).

Zea, L. et al. Potential biofilm control strategies for extended spaceflight missions. Biofilm 2, 100026 (2020).

Venkateswaran, K. et al. International Space Station environmental microbiome—microbial inventories of ISS filter debris. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 6453–6466 (2014).

Coil, D. A. et al. Growth of 48 built environment bacterial isolates on board the International Space Station (ISS). PeerJ 4, e1842 (2016).

Klaus, D., Simske, S., Todd, P. & Stodieck, L. Investigation of space flight effects on Escherichia coli and a proposed model of underlying physical mechanisms. Microbiology 143, 449–455 (1997).

Kim, W. et al. Spaceflight promotes biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 8, e62437 (2013).

Flores, P., McBride, S. A., Galazka, J. M., Varanasi, K. K. & Zea, L. Biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in spaceflight is minimized on lubricant impregnated surfaces. npj Microgravity 9, 66 (2023).

Diaz, A. M., Li, W., Calle, L. M., Callahan, M. R. Investigation of biofilm formation and control for spacecraft-an early literature review. 2019.

Weir, N. et al. Microbiological characterization of the International Space Station water processor assembly external filter assembly S/N 01. 2012; p. 3595.

Vaccari, L. et al. Films of bacteria at interfaces. Adv. Colloid interface Sci. 247, 561–572 (2017).

Benoit, M. R. & Klaus, D. M. Microgravity, bacteria, and the influence of motility. Adv. Space Res. 39, 1225–1232 (2007).

Klaus, D. M., Benoit, M. R., Nelson, E. S. & Hammond, T. G. Extracellular mass transport considerations for space flight research concerning suspended and adherent in vitro cell cultures. J. Gravitational Physiol11, 17–27 (2004).

Drescher, K., Dunkel, J., Cisneros, L. H., Ganguly, S. & Goldstein, R. E. Fluid dynamics and noise in bacterial cell–cell and cell–surface scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 10940–10945 (2011).

Aranson, I. S. Bacterial active matter. Rep. Prog. Phys. 85, 076601 (2022).

Dickinson, R. B. & Tranquillo, R. T. Optimal estimation of cell movement indices from the statistical analysis of cell tracking data. AIChE J. 39, 1995–2010 (1993).

Wu, P.-H., Giri, A. & Wirtz, D. Statistical analysis of cell migration in 3D using the anisotropic persistent random walk model. Nat. Protoc. 10, 517–527 (2015).

Lauffenburger, D., Aris, R. & Keller, K. Effects of cell motility and chemotaxis on microbial population growth. Biophys. J. 40, 209–219 (1982).

Uhlenbeck, G. E. & Ornstein, L. S. On the theory of the Brownian motion. Phys. Rev. 36, 823 (1930).

Gordon, V. D. & Wang, L. Bacterial mechanosensing: the force will be with you, always. J. Cell Sci. 132, jcs227694 (2019).

Baker, A. E. et al. PilZ domain protein FlgZ mediates cyclic di-GMP-dependent swarming motility control in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 198, 1837–1846 (2016).

Kim, W. et al. Effect of spaceflight on Pseudomonas aeruginosa final cell density is modulated by nutrient and oxygen availability. BMC Microbiol. 13, 1–10 (2013).

Dergham, Y. et al. Comparison of the genetic features involved in Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation using multi-culturing approaches. Microorganisms 9, 633 (2021).

Dergham, Y. et al. Direct comparison of spatial transcriptional heterogeneity across diverse Bacillus subtilis biofilm communities. Nat. Commun. 14, 7546 (2023).

Vasaturo, A. et al. A novel chemotaxis assay in 3-D collagen gels by time-lapse microscopy. PLoS ONE 7, e52251 (2012).

Ferraro, R. et al. Diffusion-induced anisotropic cancer invasion: A novel experimental method based on tumor spheroids. AIChE J. 68, e17678 (2022).

Recupido, F. et al. The role of flow in bacterial biofilm morphology and wetting properties. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 192, 111047 (2020).

Lecuyer, S. et al. Shear stress increases the residence time of adhesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biophys. J. 100, 341–350 (2011).

Wei, G. & Yang, J. Q. Microfluidic investigation of the impacts of flow fluctuations on the development of Pseudomonas putida biofilms. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 9, 73 (2023).

Fanesi, A. et al. Shear stress affects the architecture and cohesion of Chlorella vulgaris biofilms. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–11 (2021).

Martínez-Calvo, A. et al. Morphological instability and roughening of growing 3D bacterial colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2208019119 (2022).

Secchi, E. et al. The structural role of bacterial eDNA in the formation of biofilm streamers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2113723119 (2022).

Rusconi, R., Lecuyer, S., Guglielmini, L. & Stone, H. A. Laminar flow around corners triggers the formation of biofilm streamers. J. R. Soc. Interface 7, 1293–1299 (2010).

Fanesi, A. et al. Shear stress affects the architecture and cohesion of Chlorella vulgaris biofilms. Sci. Rep. 11, 4002 (2021).

Marra, D., Ferraro, R. & Caserta, S. Biofilm contamination in confined space stations: reduction, coexistence or an opportunity?. Front. Mater. 11, 1374666 (2024).

Evgenidis, S. P., Kalić, K., Kostoglou, M. & Karapantsios, T. D. Kerberos: a three camera headed centrifugal/tilting device for studying wetting/dewetting under the influence of controlled body forces. Colloids Surf. A521, 38–48 (2017).

Ping, L., Birkenbeil, J. & Monajembashi, S. Swimming behavior of the monotrichous bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 86, 36–44 (2013).

Shum, H., Gaffney, E. A. & Smith, D. J. Modelling bacterial behaviour close to a no-slip plane boundary: the influence of bacterial geometry. Proc. R. Soc. A466, 1725–1748 (2010).

Zheng, H. et al. Swimming of buoyant bacteria in quiescent medium and shear flows. Langmuir 39, 4224–4232 (2023).

Molaei, M., Barry, M., Stocker, R. & Sheng, J. Failed escape: solid surfaces prevent tumbling of Escherichia coli. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 068103 (2014).

Berke, A. P., Turner, L., Berg, H. C. & Lauga, E. Hydrodynamic attraction of swimming microorganisms by surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 038102 (2008).

Cornish, R. J. Flow in a pipe of rectangular cross-section. Proc. R. Soc. A120, 691–700 (1928).

Deng, J., Molaei, M., Chisholm, N. G. & Stebe, K. J. Motile Bacteria at Oil–Water Interfaces: pseudomonas aeruginosa. Langmuir 36(25), 6888–6902 (2020).

Stocker, R. Reverse and flick: hybrid locomotion in bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 2635–2636 (2011).

Berg, H. C. Motile behavior of bacteria. Phys. today 53, 24–29 (2000).

Wadhwa, N. & Berg, H. C. Bacterial motility: machinery and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 161–173 (2022).

Villa-Torrealba, A., Chávez-Raby, C., de Castro, P. & Soto, R. Run-and-tumble bacteria slowly approaching the diffusive regime. Phys. Rev. E 101, 062607 (2020).

Wei, G. & Yang, J. Q. Impacts of hydrodynamic conditions and microscale surface roughness on the critical shear stress to develop and thickness of early-stage Pseudomonas putida biofilms. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 120, 1797–1808 (2023).

Noirot-Gros, M.-F., Forrester, S., Malato, G., Larsen, P. E. & Noirot, P. CRISPR interference to interrogate genes that control biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–14 (2019).

Ascione, F. et al. Comparison between fibroblast wound healing and cell random migration assays in vitro. Exp. cell Res. 347, 123–132 (2016).

Dickinson, R. B., Guido, S. & Tranquillo, R. T. Biased cell migration of fibroblasts exhibiting contact guidance in oriented collagen gels. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 22, 342–356 (1994).

Berg, H. C. & Brown, D. A. Chemotaxis in Escherichia coli analysed by three-dimensional tracking. Nature 239, 500–504 (1972).

Hartmann, R. et al. Quantitative image analysis of microbial communities with BiofilmQ. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 151–156 (2021).

Bridier, A. & Briandet, R. Microbial biofilms: structural plasticity and emerging properties. Microorganisms 10, 138 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted under the umbrella of the European Space Agency Topical Team: “Biofilms from an interdisciplinary perspective”. Financial support was provided from the Ministry of University and Research, project PRIN 2022 PNRR "BREAKUP - Numerical and Experimental Investigation of Small Plastics Breakup in Complex Flows" - Prot. P20225AEF4 - CUP n. E53D23016850001 - Resp. Sc. Prof. S. Caserta. ESA (research projects OSIP IDEA: I-2021–03382) to University of Naples. This study was carried out within the Space It Up project funded by the Italian Space Agency, ASI, and the Ministry of University and Research, MUR, under contract n. 2024-5-E.0 - CUP n. I53D24000060005. Ing. Carmine Schiavone is gratefully acknowledged for his valuable help in the initial steps of the project in the definition of the methodologies used for the analysis of trajectories and development of MATLAB code used for data analysis. Dr. Romain Briandet and Dr. Marie-Francoise Noirot-Gros (INRAE) are gratefully acknowledged for providing bacteria strains used in this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.: Writing—Original Draft, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. M.R.: Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. S.C.: Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Resources, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marra, D., Rizzo, M. & Caserta, S. Microfluidics unveils role of gravity and shear stress on Pseudomonas fluorescens motility and biofilm growth. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 11, 122 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00744-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00744-4

This article is cited by

-

Interspecies electron transfer of mixed-species biofilms in microbial corrosion of metals: mechanisms and mitigation strategies

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2025)