Abstract

Biofilm formation by Klebsiella pneumoniae is mediated by the type 3 fimbriae Mrk, and regulated by MrkH and 3’,5’-cyclic diguanylic acid (c-di-GMP). We sought to identify specific chemical inhibitors of K. pneumoniae biofilm formation that reduced the activity of MrkH. A compound N-(3-cyano-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-cyclohepta[b]thien-2-yl)-2-methoxybenzamide, JT71, reduced K. pneumoniae mrkA promoter activity and biofilm formation by 50% without affecting cell viability. Western blot analysis, hemagglutination assays, electron microscopy and qPCR showed that JT71 reduced type 3 fimbriae production, and transcription of mrkA and mrkH. JT71 demonstrated activity against other clinical and multi-drug resistant K. pneumoniae isolates, and a type 3 fimbriate-positive Citrobacter koseri strain. In silico molecule docking was used to illustrate that JT71 could bind directly to the MrkH protein and block its activity. JT71 possesses promising drug-likeness properties and is non-toxic to mammalian cells. Chemical inhibition of transcriptional regulators that control fimbriae expression can inhibit bacterial biofilm formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Klebsiella pneumoniae species complex (KpSC) is a heterogeneous group of Gram-negative, opportunistic bacteria that are responsible for community and nosocomial infections, especially amongst immunocompromised patients1,2,3. An important mechanism of pathogenesis in hospital environments involves the formation of biofilms, which are broadly defined as surface-associated communities of bacterial cells. The presence of biofilms on medical devices used in health-care settings, such as catheters and implants, is frequently associated with infections, and places a significant burden on health care systems4,5,6.

The widespread and sometimes indiscriminate usage of conventional antimicrobials to treat bacterial infections has inevitably exerted a strong selective pressure on KpSC, resulting in the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains, such as those carrying genes encoding for extended-spectrum β-lactamases7,8,9. A novel carbapenem-hydrolysing β-lactamase, KPC-1 from K. pneumoniae, was first reported in 2001 in the USA and subsequently worldwide10, and confers resistance to nearly all β-lactams. The continued spread of these MDR pathogens represents a major threat to global human health11,12,13,14,15, and genomics of a pan-resistant K. pneumoniae strain revealed the critical role of mobile resistance elements in driving new resistance16. It is evident that biofilm-associated cells exhibit significantly enhanced phenotypic resistance to antimicrobial agents and disinfectants17,18; in some cases, the concentrations of antibiotics needed to reach bactericidal activity against bacteria with biofilms can be 10–1000 times higher than for planktonic cells, making them difficult to eradicate19,20. The close proximity of bacteria to each other within biofilms facilitates horizontal gene transfer, including resistance genes21.

An emerging strategy to combat bacterial pathogens that have become recalcitrant to conventional antibiotic treatment is to specifically target microbial virulence factors without affecting cell viability22. For example, drugs that inhibit virulence gene expression might lead to a reduction in a bacterium’s ability to colonise in vitro or in vivo surfaces, or evade a host’s immune system, without imposing a selective pressure for the development of resistance that occurs when bacterial growth is targeted23,24.

Most efforts in identifying novel virulence inhibitors place strong emphasis on targets such as toxin function and delivery25,26,27, regulators of virulence expression28,29, or the assembly of fimbriae30. None of these drugs, which address virulence, has been approved for use in humans. Anti-biofilm drugs targeting K. pneumoniae, such as diguanylate cyclase enzyme inhibitors31 or an iron antagonising molecule32 have been reported. These approaches are, like most current antibiotics, not specific for pathogens and risk changing the ‘protective’ microbiome.

Previous studies have shown that K. pneumoniae biofilm formation on a range of surfaces is mediated by the type 3 fimbriae, encoded by the mrkABCDF operon33,34,35. MrkA is the major subunit of the fimbriae that facilitates binding to abiotic surfaces, while MrkB and MrkC function as the periplasmic chaperone and the outer membrane usher, respectively34,36. Through the MrkD adhesin tip of the fimbriae, K. pneumoniae exhibits adherence to extracellular matrix proteins such as type IV and/or type V collagen, human bronchial cells, and basement membrane regions of epithelial cells37,38. The mrkABCDF operon, which is transcribed by a single promoter located upstream of mrkA, is positively regulated by a 3’,5’-cyclic diguanylic acid (c-di-GMP)-dependent transcriptional activator called MrkH, a PilZ domain protein39,40,41. When mrkH is absent or mutated, the mrkABCDF operon is transcriptionally inactive39,40,41 and biofilm formation is heavily mitigated39. However, when present and in association with c-di-GMP, MrkH binds to a nucleotide sequence known as the “MrkH box” located upstream of the type 3 fimbrial operon, to facilitate recruitment of RNA polymerase to the mrkA promoter for transcription of the mrkABCDF operon39,42. We have also reported that MrkH functions as an auto-activator for the mrkHI genes in a mechanism analogous to its function at the mrkA promoter43. The mrkI gene, which encodes another transcriptional regulator involved in type 3 fimbriae expression, is co-transcribed with mrkH39,40,41.

Given the critical importance of MrkH in activating K. pneumoniae biofilm formation, we sought to identify inhibitors of MrkH that could lead to the development of new anti-biofilm approaches (e.g., incorporation of chemicals into medical plastics to prevent bacterial attachment and subsequent biofilm formation). In this study, we screened a small compound library and identified one compound, which we named JT71, that specifically inhibited MrkH-dependent mrk transcription, type 3 fimbriae synthesis, and biofilm formation by K. pneumoniae.

Results

Design of a phenotypic screen and identification of a MrkH inhibitor

We developed a phenotypic screen of a synthetic compound library (ChemBridge ‘Microformats’) to identify compounds that specifically inhibit MrkH function (i.e., by inhibiting MrkH-mediated transcription of the mrkA promoter). The inhibitor screen used Escherichia coli strain MC4100 harbouring a MrkH-expressing plasmid (pACYC184-mrkH) and the single-copy plasmid pMUmrkA-lacZ, which carries a transcriptional fusion of the mrkA promoter (inducible by c-di-GMP via MrkH) upstream of the lacZ gene that encodes β-galactosidase39. Previous studies have shown that E. coli MC4100 carrying pMUmrkA-lacZ expresses very low β-galactosidase levels39,42. However, in the presence of pACYC184-mrkH, the β-galactosidase activity increases by over 300-fold39,42. Using this reporter system to measure MrkH-mediated activation of transcription from the mrkA promoter offered a simple method to screen for chemical inhibitors of MrkH. To eliminate false positives in the screen, a control E. coli MC4100 strain containing an unrelated transcriptional regulatory system (pACYC184-aggR/aap-lacZ)44,45 was run in parallel with the test strains. AggR regulates virulence genes in enteroaggregative E. coli and does not control type 3 fimbriae, making it a suitable negative control in this assay. Compounds that inhibited E. coli growth or β-galactosidase production in both test and control strains were not examined further.

Screening of 13,440 synthetic compounds in the E. coli host strain identified the compound N-(3-cyano-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-cyclohepta[b]thien-2-yl)-2-methoxybenzamide (Fig. 1a; JT71) as a potent inhibitor of MrkH activity. Relative to the non-inhibitory reference compound G771, JT71 reduced mrkA-lacZ reporter output by approximately 56% at 71 s and 34% at 142 s when tested at 100 µM, while its effect on the aap-lacZ reporter was comparatively minor (15% and 10% reductions, respectively; Fig. 1b). Also shown in Fig. 1b is compound B371, which inhibited both reporters and was classified as a false positive due to non-specific or toxic effects. JT71 selectively inhibited luminescence only in the mrkA-lacZ reporter strain, suggesting target specificity. The chemical structures of B371 and G771 are provided in Supplementary Fig. S1.

a Chemical structure of JT71. b Luminescence-based β-galactosidase screen of E. coli MC4100 containing either pMUmrkA-lacZ and pACYC184-mrkH (test plate) or pMUaap-lacZ and pACYC184-aggR (control plate), following treatment with ChemBridge library compounds. The activity of the hit compound JT71 was assessed relative to G771, a representative non-inhibitory compound on the same plate, while B371 represents a false positive that inhibited both reporters. Data shown are single measurements from the primary screen. c β-galactosidase activity from the mrkA promoter reporter in K. pneumoniae ΔlacZ in the presence of 50 µM JT71 or 1% DMSO. Activity from the mtr-lacZ control promoter is shown in parallel. Symbols represent biological replicates pooled from three independent assays; horizontal lines indicate the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed t test. d qRT-PCR analysis of K. pneumoniae AJ218 grown in the presence of 50 µM JT71 or 1% DMSO. Transcript levels of mrkA and mrkH were quantified and normalised to rpoD. Expression values are presented as fold change relative to the DMSO control. Horizontal bars indicate the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed t test. e Static growth of K. pneumoniae AJ218 (OD600) over 6 hours in M63 media containing 50 µM JT71 or 1% DMSO. Data are shown as the mean ± SD from three independent assays.

To validate this finding in the native host, JT71 was tested in two strains of K. pneumoniae AJ218 (ΔlacZ) carrying either pMUmrkA-lacZ (test strain) or pACYC177-tyrR/pMUmtr-lacZ (control strain)29. At 50 µM, JT71 inhibited MrkH-mediated mrkA promoter activity by approximately 50%, while having no measurable effect on TyrR-dependent mtr expression (Fig. 1c). The use of two unrelated regulatory systems (aggR/aap and tryR/mtr) across both stages of the assay helped confirm the specificity of JT71 and rule out off-target effects on general transcription or β-galactosidase activity. To determine whether the observed effects were due to general toxicity, K. pneumoniae was cultured in M63 minimal media with or without 50 µM JT71. M63 media was used in place of LB for downstream assays, as it promotes more consistent expression of type 3 fimbriae and provides a defined environment for assessing compound activity.

To confirm that JT71 inhibits MrkH-dependent transcription of the mrkABCDF and mrkHI operons, we quantified mrkA and mrkH mRNA levels in K. pneumoniae AJ218 grown with or without 50 µM JT71 using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Treatment with JT71 led to a 2.4-fold reduction in mrkA transcript levels compared to the DMSO control (P = 0.0016), and a 2.4-fold reduction in mrkH transcript levels (P = 0.0070) (Fig. 1d). These results demonstrate that JT71 inhibits transcription from both the mrkA and mrkH promoters, consistent with its proposed role as an inhibitor of MrkH function. No differences in growth were observed over a 6-hour incubation, confirming that JT71 did not impair bacterial viability under these conditions (Fig. 1e).

JT71 reduces type 3 fimbriae production of K. pneumoniae

To confirm that JT71 inhibits MrkH function and determine whether this results in reduced type 3 fimbriae expression, we performed assays to detect MrkA production. Whole-cell lysates from K. pneumoniae were separated by SDS-PAGE and analysed by Western blot using anti-MrkA antisera to detect the major fimbrial subunit. The upper panel of Fig. 2a shows a Coomassie-stained gel used to verify equal protein loading across lanes. The lower panel shows the corresponding Western blot, comparing untreated (1% DMSO) K. pneumoniae samples (wild-type and ΔmrkA complemented with pACYC184-mrkABCDF) with samples treated with 50 µM JT71. MrkA production was markedly reduced in JT71-treated samples relative to untreated controls. The complemented strain, which overexpresses mrkABCDF, exhibited a more intense MrkA signal, as expected, and was used to enhance detection sensitivity due to low MrkA expression in the wild-type background.

a SDS-PAGE of whole-cell lysates and Western blot of MrkA from K. pneumoniae grown with or without 50 µM JT71. K. pneumoniae containing pMrk (mrkABCDF) was used to overexpress type 3 fimbriae. A type 3 fimbriae mutant (ΔmrkA) was used as a negative control. b Hemagglutination assay showing the lowest bacterial concentration (cfu/mL) required to agglutinate tanned sheep erythrocytes. Horizontal bars represent the mean, and data points shown are biological replicates from one representative experiment of two independent experiments performed. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed t test. c Representative images of hemagglutination reactions with K. pneumoniae at the indicated bacterial concentrations grown with or without 50 µM JT71. d Representative TEM images of K. pneumoniae immunogold-labelled with anti-MrkA antibodies. Cells were grown with or without 50 µM JT71. Immunogold particles (black dots) indicate surface-localised MrkA. Scale bars are shown.

The type 3 fimbriae of K. pneumoniae can be selectively detected in a functional assay using tanned erythrocytes in a mannose-resistant hemagglutination reaction that involves the fimbrial adhesin tip protein MrkD46. We sought to determine whether JT71 reduces the production of type 3 fimbriae using this assay. Following growth of K. pneumoniae AJ218 for 6 hours statically in the presence of 50 µM JT71 or 1% DMSO, serial dilutions of bacteria were mixed with tanned sheep erythrocytes and allowed to agglutinate. The minimum bacterial density of K. pneumoniae required to agglutinate the erythrocytes was then determined. As expected, the negative control (K. pneumoniae ΔmrkA) failed to agglutinate erythrocytes even at the highest bacterial cell density tested (7.3 × 109 cfu/mL). The average minimum bacterial density required to cause an agglutination reaction in K. pneumoniae wild-type was 5.5 × 108 cfu/mL for the untreated sample (1% DMSO) and 8.5 × 108 cfu/mL for the JT71-treated sample (50 µM) (Fig. 2b). Thus, JT71 significantly increased the number of K. pneumoniae cells required to agglutinate erythrocytes in a type 3 fimbriae-dependent manner (see Fig. 2c for representative images of agglutination reactions).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with immunogold labelling was used to visually confirm whether JT71-treatment of K. pneumoniae caused reduced production of type 3 fimbriae on the cell surface. The cell surface of untreated bacteria (1% DMSO) was covered in large quantities of fimbriae up to 1 µm long that were bound to gold-labelled monoclonal MrkA antibodies (Fig. 2d). In contrast, JT71-treated bacteria showed a reduction in the number and length of labelled fimbriae on the cell surface.

Taken together, these observations demonstrated that JT71 is a type 3 fimbriae inhibitor that acts to significantly reduce the amount of MrkA subunit produced, leading to a reduction of type 3 fimbriae presented on the K. pneumoniae cell surface.

Incubation of K. pneumoniae with JT71 inhibits biofilm formation

We have previously reported that MrkH promotes type 3 fimbriae production and biofilm formation on a number of medically relevant materials, including polystyrene and collagen-coated surfaces29,39,43. Having established that JT71 reduced MrkH-mediated transcription from the mrkA and mrkH promoters, causing a significant reduction in type 3 fimbriae production, we next examined whether this translated into reduced biofilm formation.

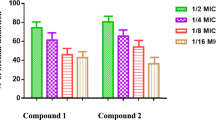

Biofilm assays were performed using K. pneumoniae AJ218 cultured in M63 minimal media on uncoated polystyrene and type IV collagen-coated polystyrene surfaces. Type IV collagen was selected to simulate host extracellular matrix conditions encountered on damaged tissue or indwelling medical devices, where type 3 fimbriae play a critical role in adherence33,47. JT71 significantly inhibited biofilm formation on both surfaces in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3). Maximum inhibition was observed at 100 µM, with a 60% reduction on uncoated polystyrene (Fig. 3a), and a 50% reduction on type IV collagen-coated surfaces (Fig. 3b). These findings confirm that blocking MrkH function with JT71 impairs the ability of K. pneumoniae to form biofilm under both abiotic and host-mimicking conditions.

Biofilm formation of K. pneumoniae AJ218 on uncoated polystyrene (a) and type IV collagen-coated polystyrene (b) grown in the presence of varying concentrations of JT71 or equivalent concentrations of DMSO solvent used. Biological replicates (n = 25–30) are pooled from three independent assays, and the mean ± 95% CI for each group is shown. c Biofilm formation of K. pneumoniae (Kp), C. koseri (Ck), and P. aeruginosa (Pa) strains grown with or without 50 µM JT71. Data are the mean ± 95% CI of biological replicates pooled from three independent assays. Each JT71-treated group was compared to controls that were treated with equivalent amounts of DMSO solvent using two-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post-test, *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

To assess whether JT71 can reduce pre-formed biofilms, K. pneumoniae AJ218 biofilms were established for either 8 or 24 hours prior to treatment with 50 µM JT71 or 1% DMSO. Assays were performed either by adding the treatment directly to the existing medium or by replacing the medium with fresh treatment-containing medium. Biofilm biomass was then quantified over periods of up to 48 hours post-treatment (Supplementary Fig. S2). Across all conditions, JT71 did not significantly reduce biofilm biomass relative to DMSO controls (Wilcoxon signed-ranked test, p > 0.05). These findings indicate that JT71 lacks biofilm-eradicating activity but remains a potent inhibitor of biofilm formation during the early stages of development.

JT71 inhibits biofilm formation in other type 3 fimbriated K. pneumoniae and Citrobacter koseri isolates

The chromosomal region encoding the mrkABCDF and mrkHI operons is highly conserved among K. pneumoniae strains, with nucleotide similarity exceeding 90% across sequenced genomes39. To determine whether JT71 has broader anti-biofilm activity within this species, we tested three additional clinical K. pneumoniae isolates (AJ94, AJ97, and MGH78578), all of which carry conserved mrk operons. Each strain showed a significant reduction in biofilm formation when cultured with 50 µM JT71 compared to DMSO-treated controls (Fig. 3c), consistent with inhibition of MrkH-dependent fimbriae production.

We next examined whether JT71 could inhibit biofilm formation in C. koseri, another type 3 fimbriae-producing species within the Enterobacteriaceae. C. koseri is a known cause of urinary tract infections, sepsis, and meningitis, particularly in neonates and immunocompromised adults48,49,50. It also carries a conserved mrk locus51, but robust biofilm formation under our assay conditions required elevated intracellular c-di-GMP levels. To promote biofilm formation and activate MrkH, we overexpressed the yfiRNB operon (encoding the diguanylate cyclase YfiN39) in wild-type C. koseri BAA-895 using pACYC184-yfiRNB. Treatment with 50 µM JT71 significantly reduced biofilm formation relative to DMSO controls (Fig. 3c), suggesting that the compound inhibits MrkH-dependent transcription in C. koseri as well.

To test whether JT71 affects biofilm formation in organisms lacking mrk genes, we examined the Pseudomonas aeruginosa model strain PAO1, which does not encode a MrkH homologue and type 3 fimbriae. JT71 had no measurable effect on PAO1 biofilm formation under the same conditions (Fig. 3c). These findings support JT71’s activity as being specific to type 3 fimbriae-producing species and consistent with its proposed mechanism of targeting MrkH-dependent regulatory pathways.

Analysis of JT71 analogues

Since JT71 emerged as a key hit compound, we sought to determine whether structural modifications could improve its biofilm-inhibitory activity. We focused on a small set of synthetically tractable modifications of the benzamide phenyl ring, while maintaining the 3-cyano-cycloheptathienyl part of the molecule, so that we could clearly observe the effect of the modifications on biofilm formation. The eight analogues were tested, along with JT71, at 50 µM in a K. pneumoniae AJ218 biofilm assay, with biofilm levels normalised to matched DMSO-treated controls. The ortho-methoxy group (i.e., O-CH3) of JT71 is a potential hydrogen bond acceptor (via the oxygen atom), and it also influences the orientation of the phenyl ring with respect to the amide moiety. Removal of the ortho-methoxy to produce JT71-P greatly reduces the ability of the compound to prevent biofilm formation (Fig. 4b), suggesting that an ortho-substituent is required for activity. Replacing the methoxy group with hydroxyl (i.e., compound JT71-OH) introduces the ability to both donate and accept hydrogen bonds in the ortho-position but decreases the size of the substituent while increasing its polarity (compared to the ortho-methoxy substituent). JT71-OH also has reduced anti-biofilm activity compared to the parent compound, JT71 (Fig. 4b). Fluorine is much smaller in size than a methoxy or hydroxyl group, and the introduction of a fluorine into the two ortho-positions (i.e., compound 4612) does not retain or improve activity. Incorporating the ortho and meta-positions of the phenyl ring into a napthyl ring system (i.e., compound 6385) also results in a loss of activity when compared to JT71 (Fig. 4b). Similarly, moving the methoxy substituent around the phenyl ring to the meta- or para-positions does not improve or retain activity (i.e., compounds 4356, 6262, and 3453). Increasing the distance between the amide moiety and the phenyl ring by inserting a methoxy linker (i.e., -OCH2-), to produce compound 1295, also results in a loss of anti-biofilm activity (Fig. 4b). In summary, all eight analogues showed markedly reduced anti-biofilm activity relative to JT71, demonstrating the importance of the ortho-methoxy substituent of the benzamide moiety of the parent compound.

JT71 exhibits “drug-likeness” properties

The molecular weight of JT71 is 326.4 g/mol, which is less than the upper limit of 500 g/mol predicted to be optimal for orally active small molecule compounds. Likewise, the compound contains one hydrogen bond donor and four hydrogen bond acceptors, which are within the optimal range for these parameters52. Finally, JT71 exhibits a low polar surface area (tPSA = 90.4 Å2) and has a partition coefficient (clogP) of 4.13. Altogether, JT71 fully satisfies Lipinski’s rule of five (i.e., molecular weight < 500 g/mol, clogP <5, <5 hydrogen bond donors and <10 hydrogen bond acceptors52,53) and possesses drug-likeness properties54. Importantly, treatment of 50 µM JT71 was found to be non-toxic to mammalian HeLa cells when compared to untreated cells, as measured by the release of LDH, an indicator of cell death (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Modelling the JT71-MrkH complex suggests two distinct inhibitory mechanisms

The structure of K. pneumoniae AJ218 MrkH is comprised of two distinct domains connected by a six-residue flexible linker (Fig. 5a)55. The C-terminal domain adopts a traditional PilZ domain fold, whereas the fold of the N-terminal domain has been described as PilZ-like. Binding two intercalated molecules of c-di-GMP to the C-terminal PilZ domain of apo-MrkH (i.e., inactive MrkH) induces a domain rotation, which then enables the N-terminal domain to also interact with the c-di-GMP molecules (Fig. 5a–c)55. Directly opposite the two c-di-GMP molecules is a groove that runs across the central section of holo-MrkH (i.e., active MrkH, Fig. 5b). The groove is electrostatically positive (lined by several basic lysine and arginine residues), typical of a DNA-binding groove55.

The apo- and holo-MrkH structures are shown in (a, b), respectively (PDB ID: 5KEC and 5KGO55). The N- and C-terminal PilZ domains are indicated. b The two intercalated molecules of c-di-GMP bound to the holo-MrkH are depicted as yellow sticks, and the putative DNA binding groove is labelled. c Overlay of the N-terminal PilZ-like domain of apo- and holo-MrkH illustrating the large domain movement (~138°) that occurs upon binding the two molecules of c-di-GMP to the C-terminal PilZ domain. The root mean square deviation for the overlay of the apo and holo N-terminal PilZ-like domains (Cα atoms) is 0.4 Å. d–f In apo-MrkH, JT71 (green sticks) can bind to a pocket located between the N- and C-terminal PilZ domains. g–i In holo-MrkH, the DNA binding groove is the likely site of interaction of JT71 (magenta sticks). The two molecules of c-di-GMP form part of the putative DNA-binding groove and the JT71 binding pocket. e, h Show the same view as (d, g), respectively, with MrkH and c-di-GMP depicted as molecular surfaces. f, i Close-up view of the two proposed JT71 binding pockets shown in (d, g), nearby residues are shown as sticks. Polar interactions are depicted as black dashed lines. f H62 can interact with the phenyl ring of JT71 via a π-π interaction, whereas in i F114 makes this interaction with JT71.

JT71 could potentially inhibit MrkH activity by two distinct mechanisms. The first mechanism involves JT71 binding to the apo form of MrkH, thereby stabilising this conformation. The putative binding site of JT71 in apo-MrkH is a pocket located between the N- and C-terminal PilZ domains (Fig. 5d, e), which overlaps with the binding site of the two intercalated molecules of c-di-GMP. Residues forming this proposed JT71 binding site are F32, N34, H62, K63, R65, N78, P112, R113, F114, R115, S142, D143, G144, K184, N185, S205, C206 and Q207. Modelling revealed these residues can interact with JT71 via polar interactions, π-π interactions, and Van der Waals contacts (Fig. 5f). Once bound, JT71 could prevent or impede c-di-GMP from binding, and thereby block the formation of holo-MrkH and subsequent DNA binding.

An alternative inhibitory mechanism may involve JT71 binding to the proposed DNA-binding groove of holo-MrkH (Fig. 5g), preventing DNA from accessing the site and thereby inhibiting MrkH. The two molecules of c-di-GMP also form part of the putative DNA-binding groove. The electropositive DNA binding groove provides a snug binding pocket for JT71 (Fig. 5g, h), where it is surrounded by residues K25, R26, E28, H69, D71, Q107, R109, R110, P112, R113, F114, R115, R117, and D140. These residues, along with nearby atoms of c-di-GMP, can interact with JT71 via polar interactions, π-π interactions, and Van der Waals contacts (Fig. 5i).

JT71 inhibits biofilm formation independently of c-di-GMP abundance

To further explore the mechanism by which JT71 inhibits MrkH-dependent biofilm formation, we compared its activity in two K. pneumoniae strains, AJ218 wild-type and AJ218 expressing the diguanylate cyclase YfiN (expressed from pACYC184-yfiRNB), which elevates intracellular c-di-GMP and enhances biofilm formation56. If JT71 acted by competing with c-di-GMP at MrkH (as illustrated in Fig. 5d–f), its inhibitory effect would be expected to diminish in the +YfiN strain, where excess c-di-GMP could outcompete the compound. Figure 6 shows similar magnitudes of biofilm inhibition, which suggests that JT71 may not primarily compete with c-di-GMP binding, but instead interferes with the DNA-binding activity of MrkH (as illustrated in Fig. 5g–i).

Biofilm biomass (OD600) was measured after 24 hours for AJ218 wild-type (WT) and AJ218 containing pACYC184-yfiRNB, which expresses the diguanylate cyclase YfiN to elevate intracellular c-di-GMP and promote biofilm formation. Cultures were treated with 50 μM JT71 or 1% DMSO. The percentage reductions caused by JT71 treatment are shown. Data represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, each averaged from five technical replicates.

Discussion

Indwelling medical devices such as implants, catheters, and endotracheal tubes are frequently used in medical practice. With prolonged use, these devices can be colonised with microbial biofilms, commonly leading to chronic infections that are difficult to treat. K. pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen that is often associated with nosocomial infections amongst patients with indwelling devices6,57,58. A study on device-related infections showed that K. pneumoniae was the major contributor to biofilm-based catheter-related bloodstream infections and catheter-associated urinary tract infections6, and KpSC are commonly isolated from reused catheters in patients with spinal injury59.

Biofilm-associated cells have considerably reduced susceptibility to antimicrobial agents and disinfectants. Factors that contribute to this phenomenon include decreased antimicrobial diffusion through the biofilm matrix and the reduced growth rate of bacterial cells within the biofilm60,61,62. The biofilm environment also provides a supportive niche for enhanced conjugative plasmid transfer, further increasing the likelihood of antimicrobial resistance gene transmission between bacteria in multi-species biofilms63,64. These observations highlight the need to develop a more complete understanding of biofilm development and new approaches to prevent and treat bacterial biofilm-related infectious diseases.

The coating of catheters with antimicrobial substances has had some impact on biofilm formation65, and we hypothesised that a compound that specifically inhibits a key determinant of the biofilm process might have better utility by preventing initial adhesion of bacterial cells. Both initial and mature biofilm formation by K. pneumoniae has been shown to require the expression of type 3 fimbriae33,34,35. The MrkA filament of type 3 fimbriae mediates adherence to abiotic surfaces, while MrkD mediates attachment to specific host cell receptors on damaged tissue surfaces and/or catheters coated in situ with host-derived extracellular matrix proteins33,37,38,66. Studies have demonstrated that defined mutants of K. pneumoniae that lack either MrkA or MrkD can no longer effectively form biofilms on uncoated or human collagen-coated surfaces, respectively37,39. The type 3 fimbriae operon forms part of the K. pneumoniae core genome and was conserved in over 300 global isolates analysed67. Blocking type 3 fimbriae production represents a clear strategy to prevent K. pneumoniae adhesion to surfaces and subsequent infection in susceptible hosts.

The MrkH transcriptional regulator activates the expression of type 3 fimbriae39,40. In previous studies, we showed that MrkH becomes activated by c-di-GMP and initiates transcription at both the mrkA and mrkH promoters39,42,43. On this basis, we developed a high-throughput phenotypic screening assay that employed a transcriptional reporter to identify small molecules that block MrkH function. The main benefit of using small molecule inhibitors that specifically target regulatory pathways contributing to virulence (e.g., adhesion) is that bacterial growth is unlikely to be inhibited, thus reducing selective pressure for the development of resistance. A small molecule screening approach has been validated by other groups seeking biofilm inhibitors of Vibrio cholerae68, Porphyromonas gingivalis69, Candida albicans70, Listeria monocytogenes71, Streptococcus mutans72, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa73.

In this study, we identified a compound, JT71, that inhibited MrkH activity and subsequently reduced transcription of the type 3 fimbriae mrk operon. Of the 13,440 compounds screened, JT71 was the only molecule that consistently and selectively reduced mrkA-lacZ reporter expression. This low hit frequency suggests that pharmacological inhibition of MrkH-dependent mrk expression may be challenging, or that such inhibitors are rare within the limited chemical space represented in the screened library. We also showed that mrkH gene expression itself was down-regulated in the presence of JT71. Previously, we reported that MrkH also auto-regulates mrkH gene expression43. The two inhibitory targets suggest that the mode of transcription inhibition by JT71 of the mrkHI and mrkABCDF operons is similar. The observed transcriptional inhibition of lacZ reporter fusions by JT71 supports the conclusion that the compound enters the bacterial cytosol. Since β-galactosidase activity is a cytoplasmic process, any reduction in reporter output implies intracellular interference with the transcriptional machinery. This is consistent across both the E. coli screen and follow-up assays in K. pneumoniae, and occurred in the absence of growth inhibition, indicating that the effect is not due to general toxicity.

We also demonstrated that K. pneumoniae can form robust biofilms on a variety of medically relevant materials, and that MrkH is critical for this process43. By selecting MrkH as a target to inhibit type 3 fimbriae synthesis, we identified a compound, JT71, that inhibited biofilm formation on biotic (human collagen) and abiotic (polystyrene) surfaces commonly encountered by K. pneumoniae. We also showed that JT71 can inhibit biofilms of other clinical K. pneumoniae isolates in our collection.

Although JT71 shows promising anti-biofilm activity against K. pneumoniae in vitro, a key limitation of many antivirulence strategies is the challenge of demonstrating their effectiveness in vivo. While type 3 fimbriae are well-established mediators of adhesion to abiotic surfaces and extracellular matrix components, their contribution to virulence in standard murine models remains poorly defined. Further evaluation in catheter- or device-associated infection models may provide more appropriate systems to assess the in vivo utility of JT71. Moreover, to enhance the therapeutic potential of JT71, additional in vitro studies are warranted. We examined the importance of the ortho-methoxy substituent on biofilm formation using a small set of JT71 analogues, however, none of the eight analogues were as active as the parent compound. Optimisation of the in vitro activity and physicochemical properties of JT71 through extensive structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis would be an important step before progressing to animal models and assessing bioavailability, efficacy, and toxicity.

Early-stage biofilm formation was effectively inhibited by JT71; however, additional testing showed that it does not disrupt pre-formed biofilms, even with prolonged exposure. This indicates that its activity is confined to blocking MrkH-dependent type 3 fimbriae during the initial stages of adhesion rather than dismantling mature biofilms dominated by matrix components. Molecules such as JT71 may therefore be best suited as prophylactic anti-biofilm agents, for example, through incorporation into catheter or implant coatings to prevent initial bacterial colonisation.

Like K. pneumoniae, C. koseri forms biofilms through expressing type 3 fimbriae, with the mrkHI and mrkABCDF gene clusters well conserved51. We speculated that the MrkH homologue of C. koseri has a similar function and mechanism of action to that of K. pneumoniae MrkH. In support of this, we observed a significant reduction in biofilm formation by C. koseri when treated with JT71, suggesting that Citrobacter MrkH functions as a transcriptional activator of the C. koseri mrk genes.

A variety of compounds have been shown to reduce K. pneumoniae biofilm formation. Some compounds have been proposed to target iron uptake mechanisms32,74 or stress response regulators75. However, the mode of action for the majority of biofilm inhibitors reported is currently unknown. Type 3 fimbriae are synthesised by the chaperone-usher pathway of protein translocation and belong to the same family as the well-characterised P-pili (pap) and type 1 fimbriae (fim) systems. Various chemicals have been shown to inhibit E. coli attachment to intestinal cells by blocking the FimH adhesin of type 1 fimbriae76,77, or to inhibit the assembly of type 1 or AAF/II fimbriae post-translationally78,79. A general ‘pilicide’ has been developed which inhibits piliation by E. coli type 1, P and S pili80, and quorum sensing inhibition has also proved useful in blocking pili production81,82. To our knowledge, JT71 is the first reported chemical inhibitor of type 3 fimbriae transcription and biosynthesis, and we present two models illustrating putative binding sites of JT71 on apo or holo-MrkH.

One of the most important signalling molecules produced by bacteria is c-di-GMP, because it regulates the lifestyle transition between planktonic and biofilm states83,84,85,86,87. The ‘PilZ-domain’ proteins are the most common c-di-GMP-binding effector proteins identified so far. These proteins regulate diverse processes, including fimbriae production, flagellar activity, exopolysaccharide synthesis, and gene regulation83. Although functionally diverse, all PilZ proteins share a highly conserved sequence and structural homology in their c-di-GMP binding site. Because c-di-GMP signalling is highly conserved and unique in bacteria, and has a central role in controlling biofilm formation, targeting this system provides an attractive approach to inhibit bacterial adherence. Compounds have been identified that interfere with c-di-GMP metabolism by binding to diguanylate cyclase31,88 and phosphodiesterase73 proteins to reduce c-di-GMP synthesis, as well as binding to the PilZ-domain protein Alg44 from P. aeruginosa to reduce alginate production89.

We have identified a specific inhibitor, JT71, which targets MrkH-mediated activation of transcription at two genetic loci, and results in reduced type 3 fimbriae synthesis and biofilm formation by K. pneumoniae. This inhibition of biofilm formation extended over a wide range of clinically relevant isolates. Given the widespread conservation of type 3 fimbriae amongst K. pneumoniae, and the high prevalence of c-di-GMP-associated factors produced by the majority of bacterial species, this proof-of-principle study provides a foundation for further design and development of agents that reduce the risk of biofilm-associated infections without exacerbating the problem of more generalised antibiotic resistance.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. K. pneumoniae AJ218 is a human urinary tract infection isolate90. Unless otherwise stated, all bacterial strains were cultured at 37 °C, with shaking, in Luria Bertani (LB) broth overnight, followed by dilution in M63B1-GCAA minimal media (M63; containing 1% glycerol and 0.3% casamino acids). When necessary, the growth medium was supplemented with chloramphenicol (30 µg/mL) or trimethoprim (200 µg/mL).

Small molecule screening assay

Overnight cultures of the test strain E. coli MC4100 (containing pMUmrkA-lacZ and pACYC184-mrkH)39 and the control strain E. coli MC4100 (containing pMUaap-lacZ and pACYC184-aggR) were diluted 1:100 in LB broth containing chloramphenicol and trimethoprim and then dispensed in 100 μL aliquots into separate 96-well microtiter trays. Compounds (5 µL, 2 mM) from the ChemBridge Microformats library (ChemBridge, San Diego, USA) were added to wells (100 μM final concentration), and trays were incubated at 37 °C for 10 h. The compound library was dissolved in 100% DMSO, resulting in a final DMSO concentration of 5%. An 8 μL aliquot of lysozyme (6 mg/mL) was added to wells and incubated for 20 min to lyse the bacterial cells. A 25 μL aliquot of Beta-Glo solution (Promega, Madison, USA) was then added to wells to convert the β-galactosidase released from cells into a luminescence signal. The level of luminescence from each well was measured at 0 s, 71 s, and 142 s with a FLUOStar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). Compounds that inhibited luminescence by >50% (measured as Relative Luminescence Units (RLU) compared to a representative non-inhibitory compound on the same plate), without reducing the RLU of the control strain by >30% relative to the same reference, at either of the two time-points, were identified as promising candidates and investigated further. DMSO-only controls showed no inhibition of growth or β-galactosidase activity, indicating E. coli was tolerant under the assay conditions. For subsequent validation experiments in K. pneumoniae, DMSO was used at 1% to minimise solvent-related effects.

Beta-galactosidase assay

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 with M63 media containing the appropriate antibiotics and grown statically in the presence or absence of the ChemBridge compound at 37 °C for 6 h (OD600 ~ 0.8), after which the β-galactosidase activity was determined as described elsewhere39. The data shown are the results of three independent assays.

RNA extraction

K. pneumoniae AJ218 was grown statically overnight at 37 °C in M63 supplemented with either 50 µM JT71 or 1% DMSO. Bacteria were diluted 1:100 in the same media and supplements, and grown in 96-well microtiter trays statically at 37 °C for 6 h (OD600 of ~0.9). A 5 mL volume of culture was incubated with 10 mL of RNAProtect solution (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) at room temperature. The cells were pelleted, and RNA was extracted using a FastRNA Pro Blue Kit (Q-Biogene). Residual DNA was removed using an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen) prior to RNA purification with a RNeasy MiniElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). RNA quality was validated with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (G2938C). All samples had an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) greater than 8.1.

Quantitative real-time PCR

The extracted cellular RNA from K. pneumoniae AJ218 (1 µg) was used as template to synthesise cDNA with Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies, USA) with random hexamers in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The absence of residual genomic DNA was verified by a conventional PCR reaction. qRT-PCR was performed using a 20 μL reaction mixture containing the following: 10 μL of 2× SsoFast Evagreen Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, California, USA), 1 μM of primer pair qMrkA-for (AGGATGACGTAAGCAAACTGG) and qMrkA-rev (CGGTAGCGTTGTCAGTAGACAG) or qrpoDFor (TAAGGAGCAAGGCTATCTGACC) and qrpoDRev (ACCTGAATACCCATGTCGTTG), and 5 μL of 1:10 diluted of newly synthesised first strand cDNA. Each reaction was performed in triplicate. Amplification of target and housekeeping gene transcripts was performed with a CFX96 RT-PCR/C1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with the following programme: 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 55 °C for 20 s. CFX Manager version 2.0 (Bio-Rad) software was used to perform data analysis. The gene of interest (mrkA or mrkH) was normalised against the housekeeping gene, rpoD, and the expression ratios between untreated (1% DMSO) and treated (50 µM JT71) samples were determined.

Western blot

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 with M63 media with appropriate antibiotics in 96-well microtiter plates. Following 6 h incubation at 37 °C, cells were harvested, and the OD600 of the whole-cell lysates was standardised. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond-C Extra nitrocellulose (Amersham Bioscience, Amersham, UK) using a Transblot SD Electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 12 V for 30 min. The membrane was blocked for 2 h at 4 °C in 5% skim milk in PBS and then washed 3 × 10 min in 0.05% PBST, followed by 3 × 10 min in distilled water. The primary MrkA antibody (anti-rabbit) was diluted 1:1000 in PBS containing 1% casein and 0.05% thiomersal and incubated with the membrane at 4 °C overnight. Unbound antibody was removed by washing the membrane in 0.05% PBST for 3 × 15 min, followed by 3 × 10 min in distilled water. Anti-rabbit secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Invitrogen) was diluted 1:3000 with 1% skim milk in PBS and incubated with the membrane for 2 h. The membrane was subsequently developed with TMB Membrane Peroxidase Substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, USA).

Hemagglutination assay

Type 3 fimbriae production by K. pneumoniae was detected by mannose-resistant hemagglutination assays as described previously39. Briefly, tannic acid-treated sheep erythrocytes were mixed with equal volumes of a series of 2-fold dilutions of bacterial suspension treated with 50 μM of JT71 or 1% DMSO. The minimum bacterial density (cfu/mL) required to agglutinate erythrocytes was determined. Two independent experiments were performed, yielding a total of eight samples. The data shown are representative of one experiment (five samples).

Static biofilm assay

Nunc 96-well non-treated polystyrene microtiter plates (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) that were uncoated or coated with type IV human collagen (Sigma-Aldrich; C7526) were used for biofilm assays. The type IV collagen-binding assay was performed as described previously91,92 with minor modifications. Briefly, wells were coated with type IV collagen (5 μg/mL) in PBS for 18 h at 4 °C, followed by a blocking step with 1% BSA for 2 h at room temperature. The wells were then washed three times with 0.05% PBST and air-dried. Material surfaces were incubated with ~ 107 cfu/mL of bacteria in M63 media supplemented with JT71 (10–100 µM) or its corresponding DMSO concentration (0.2–2%). Following 6 h of static incubation at 37 °C, the surfaces were washed twice with distilled water. Adherent biofilms were stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA) for 15 min, solubilised with 33% acetic acid, and absorbance readings were taken at OD600. Data for each strain represents mean values taken from at least five replicate wells performed in at least three independent experiments.

Transmission electron microscopy

Overnight cultures of wild-type K. pneumoniae AJ218 were diluted 1:100 with M63 media supplemented with 50 μM of JT71 or 1% DMSO. Following 6 h of static incubation at 37 °C, the cultures were pelleted and resuspended with 100 μL of PBS. 15 μL of the suspension was placed on formvar/carbon-coated EM grids. The grids were blocked with blocking solution (1% skim milk, 1% BSA in TBS) for 20 min at room temperature and transferred directly to primary MrkA antibody (1:100) for 1 h incubation. The grids were subsequently washed with washing buffer (TBS with 0.2% BSA) and incubated with gold conjugate (1:100 in TBS + 0.2% BSA), after which the samples were negatively stained with 1.5% ammonium molybdate for 30 s and placed under a Phillips CM120 transmission electron microscope at 120 kV for visualisation.

Synthesis of N-(3-cyano-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-cyclohepta[b]thien-2-yl]-2-hydroxybenzamide (JT71-OH)

To a solution of N-(3-cyano-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-cyclohepta[b]thien-2-yl]-2-methoxybenzamide (JT71) (1.0 mM, 328 mg) in anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) (20 mL) under argon at −78 °C was added boron tribromide (1.0 M in DCM, 2.0 mL) dropwise. The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for a further 22 h. Water (20 mL) and diethyl ether (20 mL) were added, and the phases were separated. The aqueous phase was extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 20 mL), and the combined organic phases were washed with water and brine, dried (MgSO4), and evaporated to give a yellow-brown powder. Flash column chromatography (silica gel, EtOAc-hexane, 4:1) gave N-(3-cyano-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-cyclohepta[b]thien-2-yl]-2-hydroxybenzamide (JT71-OH) as a white powder (314 mg, 100%).

Eukaryotic cell toxicity assay

An LDH Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Takara Bio Inc.; Japan) was used to determine the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), an indicator of cell death. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, HeLa cells in DMEM (10% FCS, v/v) were seeded at ~0.8 × 104 cells/well. After overnight incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2, the cells were washed once with PBS to remove LDH released during overnight incubation. The cells were then supplemented with DMEM (1% FCS, v/v) only, or media containing JT71 (50 μM) or its corresponding DMSO concentration. Controls included cells incubated with DMEM (1% FCS, v/v) supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 or DMEM (1% FCS, v/v) in empty wells. After incubation for 6 h, the microtiter plates were centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min, and 100 μL/well supernatant was transferred to new wells. 100 μL of the substrate mix was added to the wells and incubated up to 15 min. Absorbance (at 490 nm) from each well was measured using a FLUOStar Omega plate reader. The percentage of cell death (cytotoxicity) was determined by using the formula \(\frac{({experimental\; value}-{background\; release})}{({maximum\; release}-{background\; release})}\) × 100%.

Modelling the JT71–MrkH complex

There are four MrkH crystal structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for K. pneumoniae K54 strain AJ218 (UniProt ID: G3FT00): two are apo (inactive) structures (PDB IDs: 5KEC and 5KED55) and two are holo (active) structures where MrkH is in complex with two intercalated molecules of c-di-GMP (PDB ID: 5EJL93 and 5KGO55). In the apo-MrkH structures, there are two MrkH molecules in the 5KEC asymmetric unit (the smallest repeating object that generates the unit cell of the crystal) and four such molecules in 5KED, giving a total of six separate molecules to examine. The six molecules of apo-MrkH were aligned via the Cα atoms (root mean square deviation <0.8 Å); the conformations are almost identical, therefore the A chain of 5KEC was selected for the compound JT71 in silico docking studies. In the asymmetric unit of the unit cell of the holo-MrkH complexes, there are two molecules of MrkH in 5KGO and one molecule in 5EJL. The three molecules of holo-MrkH were aligned via the Cα atoms (root mean square deviation <1.7 Å); there are small conformational differences at the extremities of the N- and C-terminal MrkH PilZ domains, but these are well away from the c-di-GMP binding pocket and the putative DNA binding groove. The three molecules of holo-MrkH are very similar around the c-di-GMP binding pocket and the putative DNA binding groove; therefore, the A chain of 5KGO was selected for JT71 in silico docking studies.

JT71 was docked into the two most distinct putative binding pockets, one located between the N- and C-terminal PilZ domains of apo-MrkH, and the second was the putative DNA binding groove of holo-MrkH. Flexible protein and compound docking was performed using Surflex-Dock v2.7 (within SYBYL-X 2.1.1, Certara, L.P., Princeton, NJ, USA); the protocol was generated using the automatic method, a 0.5 threshold, and a bloat value of 3 for apo-MrkH and 5 for holo-MrkH. GeomX docking mode was used, with protein flexibility enabled and all other parameters set to default values. The docked poses of JT71 were ranked using the C Score scoring function, and the top 30 ranked poses in each MrkH structure (i.e., the apo and holo structures) were retained for analysis.

All JT71-MrkH docking figures were created using The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.1.1 (Schrödinger LLC, Cambridge, MA).

Physicochemical properties of JT71

Molecular weight (g/mol), partition coefficient (clogP), topological polar surface area (tPSA in Å2), and the number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors were calculated for JT71 using OSIRIS DataWarrior version 5.2.194.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Podschun, R. & Ullmann, U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11, 589–603 (1998).

Lei, T. Y., Liao, B. B., Yang, L. R., Wang, Y. & Chen, X. B. Hypervirulent and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: A global public health threat. Microbiol. Res. 288, 127839 (2024).

Yu, V. L. et al. Virulence characteristics of Klebsiella and clinical manifestations of K. pneumoniae bloodstream infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 986–993 (2007).

Hall-Stoodley, L., Costerton, J. W. & Stoodley, P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 95–108 (2004).

Camara, M. et al. Economic significance of biofilms: a multidisciplinary and cross-sectoral challenge. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 8, 42 (2022).

Singhai, M., Malik, A., Shahid, M., Malik, M. A. & Goyal, R. A study on device-related infections with special reference to biofilm production and antibiotic resistance. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 4, 193–198 (2012).

Davies, J. & Davies, D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 417–433 (2010).

Gniadkowski, M. Evolution of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases by mutation. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14, 11–32 (2008).

Dong, N., Yang, X., Chan, E. W., Zhang, R. & Chen, S. Klebsiella species: Taxonomy, hypervirulence and multidrug resistance. EBioMedicine 79, 103998 (2022).

Yigit, H. et al. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1151–1161 (2001).

Navon-Venezia, S. et al. First report on a hyperepidemic clone of KPC-3-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Israel genetically related to a strain causing outbreaks in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 818–820 (2009).

Nordmann, P., Cuzon, G. & Naas, T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9, 228–236 (2009).

Schwaber, M. J. & Carmeli, Y. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a potential threat. JAMA 300, 2911–2913 (2008).

Villegas, M. V. et al. First detection of the plasmid-mediated class A carbapenemase KPC-2 in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from South America. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 2880–2882 (2006).

Miller, W. R. & Arias, C. A. ESKAPE pathogens: antimicrobial resistance, epidemiology, clinical impact and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 598–616 (2024).

Zowawi, H. M. et al. Stepwise evolution of pandrug-resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 5, 15082 (2015).

Hoiby, N., Bjarnsholt, T., Givskov, M., Molin, S. & Ciofu, O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35, 322–332 (2010).

Lewis, K. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 999–1007 (2001).

Li, L. et al. Relationship between biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae and updates on antibiofilm therapeutic strategies. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1324895 (2024).

Chung, P. Y. The emerging problems of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections: carbapenem resistance and biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 363, fnw219 (2016).

Maree, M., Ushijima, Y., Fernandes, P. B., Higashide, M. & Morikawa, K. SCCmec transformation requires living donor cells in mixed biofilms. Biofilm 7, 100184 (2024).

Allen, R. C., Popat, R., Diggle, S. P. & Brown, S. P. Targeting virulence: can we make evolution-proof drugs?. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 300–308 (2014).

Clatworthy, A. E., Pierson, E. & Hung, D. T. Targeting virulence: a new paradigm for antimicrobial therapy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 541–548 (2007).

Rasko, D. A. & Sperandio, V. Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 117–128 (2010).

Moayeri, M., Wiggins, J. F., Lindeman, R. E. & Leppla, S. H. Cisplatin inhibition of anthrax lethal toxin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 2658–2665 (2006).

Nordfelth, R., Kauppi, A. M., Norberg, H. A., Wolf-Watz, H. & Elofsson, M. Small-molecule inhibitors specifically targeting type III secretion. Infect. Immun. 73, 3104–3114 (2005).

Shoop, W. L. et al. Anthrax lethal factor inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 7958–7963 (2005).

Anthouard, R. & DiRita, V. J. Small-molecule inhibitors of toxT expression in Vibrio cholerae. MBio 4, e00403–e00413 (2013).

Yang, J. et al. Disarming bacterial virulence through chemical inhibition of the DNA binding domain of an AraC-like transcriptional activator protein. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 31115–31126 (2013).

Klein, R. D. & Hultgren, S. J. Urinary tract infections: microbial pathogenesis, host-pathogen interactions and new treatment strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 211–226 (2020).

Sambanthamoorthy, K. et al. Identification of small molecules that antagonize diguanylate cyclase enzymes to inhibit biofilm formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 5202–5211 (2012).

Chhibber, S., Nag, D. & Bansal, S. Inhibiting biofilm formation by Klebsiella pneumoniae B5055 using an iron antagonizing molecule and a bacteriophage. BMC Microbiol. 13, 174 (2013).

Jagnow, J. & Clegg, S. Klebsiella pneumoniae MrkD-mediated biofilm formation on extracellular matrix- and collagen-coated surfaces. Microbiology 149, 2397–2405 (2003).

Langstraat, J., Bohse, M. & Clegg, S. Type 3 fimbrial shaft (MrkA) of Klebsiella pneumoniae, but not the fimbrial adhesin (MrkD), facilitates biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 69, 5805–5812 (2001).

Di Martino, P., Cafferini, N., Joly, B. & Darfeuille-Michaud, A. Klebsiella pneumoniae type 3 pili facilitate adherence and biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces. Res. Microbiol. 154, 9–16 (2003).

Murphy, C. N. & Clegg, S. Klebsiella pneumoniae and type 3 fimbriae: nosocomial infection, regulation and biofilm formation. Future Microbiol. 7, 991–1002 (2012).

Hornick, D. B., Thommandru, J., Smits, W. & Clegg, S. Adherence properties of an mrkD-negative mutant of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 63, 2026–2032 (1995).

Tarkkanen, A. M. et al. Type V collagen as the target for type-3 fimbriae, enterobacterial adherence organelles. Mol. Microbiol. 4, 1353–1361 (1990).

Wilksch, J. J. et al. MrkH, a novel c-di-GMP-dependent transcriptional activator, controls Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm formation by regulating type 3 fimbriae expression. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002204 (2011).

Johnson, J. G., Murphy, C. N., Sippy, J., Johnson, T. J. & Clegg, S. Type 3 fimbriae and biofilm formation are regulated by the transcriptional regulators MrkHI in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 193, 3453–3460 (2011).

Wu, C. C. et al. Fur-dependent MrkHI regulation of type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. Microbiology 158, 1045–1056 (2012).

Yang, J. et al. Transcriptional activation of the mrkA promoter of the Klebsiella pneumoniae type 3 fimbrial operon by the c-di-GMP-dependent MrkH protein. PLoS One 8, e79038 (2013).

Tan, J. W. et al. Positive Autoregulation of mrkHI by the cyclic di-GMP-dependent MrkH protein in the biofilm regulatory circuit of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 197, 1659–1667 (2015).

Morin, N. et al. Autoactivation of the AggR regulator of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli in vitro and in vivo. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58, 344–355 (2010).

Nataro, J. P., Yikang, D., Yingkang, D. & Walker, K. AggR, a transcriptional activator of aggregative adherence fimbria I expression in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176, 4691–4699 (1994).

Duguid, J. P. Fimbriae and adhesive properties in Klebsiella strains. J. Gen. Microbiol. 21, 271–286 (1959).

Murphy, C. N., Mortensen, M. S., Krogfelt, K. A. & Clegg, S. Role of Klebsiella pneumoniae type 1 and type 3 fimbriae in colonizing silicone tubes implanted into the bladders of mice as a model of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect. Immun. 81, 3009–3017 (2013).

Doran, T. I. The role of Citrobacter in clinical disease of children: review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28, 384–394 (1999).

Dzeing-Ella, A. et al. Infective endocarditis due to Citrobacter koseri in an immunocompetent adult. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 4185–4186 (2009).

Vaz Marecos, C., Ferreira, M., Ferreira, M. M. & Barroso, M. R. Sepsis, meningitis and cerebral abscesses caused by Citrobacter koseri. BMJ Case Rep. 2012, bcr1020114941 (2012).

Ong, C. L. et al. Molecular analysis of type 3 fimbrial genes from Escherichia coli, Klebsiella and Citrobacter species. BMC Microbiol. 10, 183 (2010).

Lipinski, C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W. & Feeney, P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 46, 3–26 (2001).

Doak, B. C., Over, B., Giordanetto, F. & Kihlberg, J. Oral druggable space beyond the rule of 5: insights from drugs and clinical candidates. Chem. Biol. 21, 1115–1142 (2014).

Veber, D. F. et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 45, 2615–2623 (2002).

Schumacher, M. A. & Zeng, W. Structures of the activator of K. pneumoniae biofilm formation, MrkH, indicates PilZ domains involved in c-di-GMP and DNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10067–10072 (2016).

Malone, J. et al. YfiBNR mediates cyclic di-GMP dependent small colony variant formation and persistence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PloS Pathog. 6, e1000804 (2010).

Mermel, L. et al. Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter–related infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32, 1249–1272 (2001).

Stahlhut, S. G., Struve, C., Krogfelt, K. A. & Reisner, A. Biofilm formation of Klebsiella pneumoniae on urethral catheters requires either type 1 or type 3 fimbriae. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 65, 350–359 (2012).

Miller, T. et al. The microbiological burden of short-term catheter reuse in individuals with spinal cord injury: a prospective study. Biomedicines 11, 1929 (2023).

Nguyen, D. et al. Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science 334, 982–986 (2011).

Tuomanen, E., Cozens, R., Tosch, W., Zak, O. & Tomasz, A. The rate of killing of Escherichia coli by β-lactam antibiotics is strictly proportional to the rate of bacterial growth. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132, 1297–1304 (1986).

Anderl, J. N., Franklin, M. J. & Stewart, P. S. Role of antibiotic penetration limitation in Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm resistance to ampicillin and ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 1818–1824 (2000).

Molin, S. & Tolker-Nielsen, T. Gene transfer occurs with enhanced efficiency in biofilms and induces enhanced stabilisation of the biofilm structure. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 14, 255–261 (2003).

Ong, C. L., Beatson, S. A., McEwan, A. G. & Schembri, M. A. Conjugative plasmid transfer and adhesion dynamics in an Escherichia coli biofilm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 6783–6791 (2009).

Oleksy-Wawrzyniak, M. et al. The in vitro ability of Klebsiella pneumoniae to form biofilm and the potential of various compounds to eradicate it from urinary catheters. Pathogens 11, 42 (2021).

Rego, A. T. et al. Crystal structure of the MrkD1P receptor binding domain of Klebsiella pneumoniae and identification of the human collagen V binding interface. Mol. Microbiol. 86, 882–893 (2012).

Holt, K. E. et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E3574–E3581 (2015).

Hung, D. T., Shakhnovich, E. A., Pierson, E. & Mekalanos, J. J. Small-molecule inhibitor of Vibrio cholerae virulence and intestinal colonization. Science 310, 670–674 (2005).

Wright, C. J., Wu, H., Melander, R. J., Melander, C. & Lamont, R. J. Disruption of heterotypic community development by Porphyromonas gingivalis with small molecule inhibitors. Mol. Oral. Microbiol 29, 185–193 (2014).

Fazly, A. et al. Chemical screening identifies filastatin, a small molecule inhibitor of Candida albicans adhesion, morphogenesis, and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13594–13599 (2013).

Nguyen, U. T. et al. Small-molecule modulators of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm development. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 1454–1465 (2012).

Liu, C., Worthington, R. J., Melander, C. & Wu, H. A new small molecule specifically inhibits the cariogenic bacterium Streptococcus mutans in multispecies biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 2679–2687 (2011).

Andersen, J. B. et al. Identification of small molecules that interfere with c-di-GMP signaling and induce dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 7, 59 (2021).

Hancock, V., Dahl, M. & Klemm, P. Abolition of biofilm formation in urinary tract Escherichia coli and Klebsiella isolates by metal interference through competition for Fur. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3836–3841 (2010).

de la Fuente-Nunez, C., Reffuveille, F., Haney, E. F., Straus, S. K. & Hancock, R. E. Broad-spectrum anti-biofilm peptide that targets a cellular stress response. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004152 (2014).

Brument, S. et al. Thiazolylaminomannosides as potent antiadhesives of type 1 piliated Escherichia coli isolated from Crohn’s disease patients. J. Med. Chem. 56, 5395–5406 (2013).

Totsika, M. et al. A FimH inhibitor prevents acute bladder infection and treats chronic cystitis caused by multidrug-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli ST131. J. Infect. Dis. 208, 921–928 (2013).

Lo, A. W. et al. Suppression of type 1 pilus assembly in uropathogenic Escherichia coli by chemical inhibition of subunit polymerization. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 1017–1026 (2014).

Shamir, E. R. et al. Nitazoxanide inhibits biofilm production and hemagglutination by enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains by blocking assembly of AafA fimbriae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 1526–1533 (2010).

Greene, S. E. et al. Pilicide ec240 disrupts virulence circuits in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. MBio 5, e02038 (2014).

Eisenbraun, E. L., Vulpis, T. D., Prosser, B. N., Horswill, A. R. & Blackwell, H. E. Synthetic Peptides Capable of potent multigroup Staphylococcal quorum sensing activation and inhibition in both cultures and biofilm communities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 15941–15954 (2024).

Juszczuk-Kubiak, E. Molecular aspects of the functioning of pathogenic bacteria biofilm based on quorum sensing (QS) signal-response system and innovative non-antibiotic strategies for their elimination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 2655 (2024).

Amikam, D. & Galperin, M. Y. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics 22, 3–6 (2006).

Boyd, C. D. & O’Toole, G. A. Second messenger regulation of biofilm formation: breakthroughs in understanding c-di-GMP effector systems. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 28, 439–462 (2012).

D’Argenio, D. A. & Miller, S. I. Cyclic di-GMP as a bacterial second messenger. Microbiology 150, 2497–2502 (2004).

Hengge, R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 263–273 (2009).

Sondermann, H., Shikuma, N. J. & Yildiz, F. H. You’ve come a long way: c-di-GMP signaling. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 15, 140–146 (2012).

Antoniani, D., Bocci, P., Maciag, A., Raffaelli, N. & Landini, P. Monitoring of diguanylate cyclase activity and of cyclic-di-GMP biosynthesis by whole-cell assays suitable for high-throughput screening of biofilm inhibitors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 1095–1104 (2010).

Zhou, E. et al. Thiol-benzo-triazolo-quinazolinone Inhibits Alg44 Binding to c-di-GMP and Reduces Alginate Production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 3076–3085 (2017).

Jenney, A. W. et al. Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae in an Australian Tertiary Hospital and its implications for vaccine development. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 102–107 (2006).

Sebghati, T. A., Korhonen, T. K., Hornick, D. B. & Clegg, S. Characterization of the type 3 fimbrial adhesins of Klebsiella strains. Infect. Immun. 66, 2887–2894 (1998).

Westerlund, B. et al. The O75X adhesin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli is a type IV collagen-binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 3, 329–337 (1989).

Wang, F. et al. The PilZ domain of MrkH represents a novel DNA binding motif. Protein Cell 7, 766–772 (2016).

Sander, T., Freyss, J., von Korff, M. & Rufener, C. DataWarrior: an open-source program for chemistry aware data visualization and analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model 55, 460–473 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by research grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Programme (Programme Grant 606788) and the Australian Research Council (Project Grant DP130100957). Funding from the Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support Scheme to St. Vincent’s Institute is acknowledged. M.W.P. is a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Investigator Fellow (APP1194263). N.W. is a Ruth Bishop Fellow and is supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T., J.Y., J.W., and R.S. conceived the project and conducted basic experimental design. V.B.-W., D.H., N.W., E.H., M.T., M.S., and R.R.B. conducted specific phenotypic analyses in support of J.T. and J.W. S.A.Z. and C.S. undertook the synthesis of chemical molecules. T.N. and M.P. conducted the modelling analysis, and R.S., T.L., J.W., T.N., and M.P. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the submitted manuscript and made modifications where necessary.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilksch, J.J., Tan, J.W.H., Nero, T.L. et al. Chemical inhibition of MrkH-dependent activation of type 3 fimbriae synthesis and biofilm formation by Klebsiella pneumoniae. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 11, 212 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00834-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00834-3