Abstract

The clinical utilization of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in breast cancer (BC) management is not well-defined. In this prospective study, 168 patients with early-stage BC were recruited, serial blood samples were collected before and after surgery. Tumor-informed ctDNA testing was performed, which sequenced tumors for 95 genes followed by bespoke mPCR to track 1–9 mutations in the plasma. ctDNA was detected before surgery in 14.6%, 40.0%, 83.8%, and 80.0% of HR+ low-risk, HR+ high-risk, HR-HER2+ and HR-HER2- patients, respectively. Pre-operative ctDNA positivity was significantly associated with decreased disease-free survival (DFS) (adjusted HR = 3.09, 95% CI 2.65–80.0, p = 0.001). After a median 26.6-month follow-up, 11 patients relapsed, and ctDNA at landmark time point 2–4 weeks after surgery was detected in 50.0% (5/10) of cases. Landmark ctDNA clearance was associated with significantly longer DFS (p = 0.0009) and positive ctDNA persistence after adjuvant therapy occurred in 36.4% (4/11) of stage-III patients. During surveillance, ctDNA detection had 90.9% sensitivity and 98.8% specificity to predict recurrence, and median lead time of 9.7 months. Patients with detected ctDNA had shorter DFS than those with undetectable ctDNA (adjusted HR = 207.05, 95% CI 41.38- > 1000, p = 0.001). Therefore, ctDNA status both before and after surgery could help stratify recurrence risk for BC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most prevalent cancer type in women, and early BC accounts for 80–90% of newly diagnosed cases1,2. TNM stage and histological/molecular subtypes remain key prognostic factors for disease-free and overall survival1,3,4. The luminal subtypes with positive hormone receptor (HR) status typically have good prognosis in the first 5 years5. However, a proportion of the HR+ patients have the risk of recurrence or death up to three-times higher in the first 2 years if they present with high-risk clinicopathological characteristics, such as large tumor size, multiple nodal involvement and a high Oncotype Dx score3,4. For the HR- subtypes including the HR-HER2+ and HR-HER2-, the recurrence risk peaks approximately in the first 20 months6. Since these groups of patients have high risk of recurrence at ~10–15% in the first 2-year post surgery3,4,5, it is critical to monitor them closely in this time window.

Conventional methods to monitor BC patients are serial imaging and physical examination. All of these methods have limited sensitivity and specificity to detect post-treatment minimal residual disease (MRD), the leading cause of cancer recurrence7,8,9. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), a subtype of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) released specifically from dying cancer cells into the bloodstream, has emerged as a promising biomarker to both detect and quantify MRD. Recent evidence strongly suggests that ctDNA monitoring serves as an early prognostic biomarker and offers valuable insights into evaluating therapeutic efficacy across various stages of BC treatment10,11. Currently, there are several platforms to analyze ctDNA using sophisticated methodologies but they remain far from affordable for majority of patients, particularly those in developing countries. Despite such high cost, how to integrate ctDNA testing at different stages of BC management and what clinical trial evidence is missing to enable adoption of this biomarker into routine clinical practice remain the biggest questions to answer.

We previously developed a streamlined tumor-informed MRD assay K-Track to detect ctDNA in a small cohort of BC patients12. In this study, we completed the analysis of 24-month disease-free survival (DFS) in all BC patients having serial ctDNA monitoring. Besides the prognostic value of ctDNA, we demonstrated the clinical relevance and implications of ctDNA monitoring at different critical time points in BC management: before surgery, post surgery, and post adjuvant therapy.

Results

Study design and patient characteristics

A total of 179 early-stage BC women enrolled in our study but after exclusion due to nonadherence and withdrawal, 168 patients were finally included (Fig. 1A). The median age of our cohort was 52 and 42.9% of patients were under 50 years old. Majority had invasive ductal carcinoma (98.2%) and presented with a single tumor (91.7%) (Table 1). Stage II accounted for 50.0% while stage I and III accounted for 26.2% and 20.8% of the cases respectively. Patients were categorized into four groups: HR + HER2− (56.0%), HR + HER2+ (16.6%), HR − HER2+ (17.9%), and HR − HER2− (9.5%), and then further classified into low-risk (LowR) and high-risk (HighR) of recurrence. The LowR group included only HR+LowR patients, while the HighR group included HR+HighR, HR − HER2 + , and HR − HER2− patients (Table 1). After a median follow-up time of 26.6 months (up to 32.8 months), only 141 patients remained in the study. Of 97 HighR patients, 11.3% (11/97) were clinically diagnosed with local recurrence (3/11) and distant metastasis (8/11), while no patients (0/44) in the LowR group relapsed. Patients who relapsed had HR+ Her2- (36.4%), HR+ Her2+ (18.2%), HR-HER+ (27.3%), or HR-HER2- (18.2%) subtypes; stage III accounted for 63.6% of the cases (Table 1).

A Diagram showing the number of breast cancer patients recruited and followed up in the study, as well as the number of tissue and serial plasma samples collected for analysis. B For each patient, paired tumor FFPE and WBC DNA samples were sequenced to identify tumor-specific mutations in 95 cancer-associated genes. The top 1–9 mutations were used to detect ctDNA in serial plasma samples by bespoke multiplex PCR and ultra-deep sequencing.

A total of 168 FFPE and 499 plasma samples were collected at different time points: 163 pre-operation, 132 post-operation, 204 samples from follow-up visits (Fig. 1A, B). Genomic DNA from paired FFPE and WBC samples was hybridized to a panel of 95 cancer-associated genes (Table S1) to profile all tumor-specific variants; top variants were then selected for each patient to detect ctDNA in plasma samples (Fig. 1B).

Mutation profiling and pre-operative ctDNA detection

All 168 pairs of FFPE-WBC passed quality control criteria and at least 1 somatic mutation was identified in all tumors (Fig. S1). The average number of mutations was 5, 4, 7, and 9 mutations per patient for HR+ LowR, HR+ HighR, HR − HER2 + , and HR − HER2− subgroups (Fig. 2A). The HR+ LowR group had significantly fewer somatic mutations compared to the HR − HER2+ group. The mutation burden was not affected by the TNM stage nor node status (Fig. 2A). Since our previous study identified TP53 and PI3KCA as the most frequently mutated genes in BC12, we examined mutation frequency of these 2 genes in this larger cohort. While mutation frequencies of PI3KCA were similar across 4 subgroups, TP53 was mutated more frequently the in the HR- subgroups (HR − HER2 + : 80%, HR − HER2 − : 62.5%) compared to the HR+ subgroups (lowR: 25.0%; highR: 33.3%) (Fig. 2B).

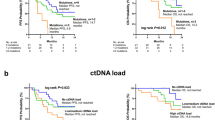

A The number of mutations identified per patient were compared among BC subtypes, stages, and node status. *p ≤ 0.05 using Kruskal-Wallis and post hoc Dunn’s test. B Mutation frequencies of the top frequently mutated genes TP53 and PIK3CA among BC subtypes. C The ctDNA detection rates in pre-operative plasma were compared among BC subtypes, stages, and nodal status. *p ≤ 0.05 using Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Kaplan-Meier analysis of disease-free survival for (D) all patients stratified by pre-operative ctDNA status, E all patients stratified by pre-operative ctDNA level (higher or lower than the median level of 0.18%), and (F) high-risk patients stratified by pre-operative ctDNA status.

The average number of mutations selected to track was 4 mutations per patient (range 1 – 9). Pre-operative detection rate of ctDNA was 14.6%, 40.0%, 83.8% and 80.0% for HR+ LowR, HR+ HighR, HR-HER2+ and HR-HER2- subgroups, respectively (Fig. 2C). The rate was highest in stage-III patients and those with lymph node involvement (Fig. 2C). Besides, mutations with VAF ≥ 10% in FFPE had a higher detection rate (18.8%) in plasma than those with VAF < 10% (1.5%) (Fig. S1E). The number of mutations selected did not affect the pre-operative ctDNA detection rate in all BC subtypes (Fig. S2).

Prognostic value of TNM stage combined with pre-operative ctDNA

We next examined the prognostic value of all pre-treatment variables. For genetic factors, the TMB and MSI status were also analyzed (Fig. S3A, B). Univariate Cox proportional hazards analysis showed that only TNM stage, lymph node involvement, risk classification and pre-operative ctDNA status were the significant factors to predict disease-free survival (DFS) (Table 2, Fig. S3C–F). Patients with pre-operative ctDNA(+) had significantly shorter DFS compared to those with ctDNA- (HR = 10.35, 95% CI 3.30–32.49, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2D). When patients were further stratified by median ctDNA VAF level of 0.18%, those with VAF higher than 0.18% showed remarkably reduced DFS compared to those with VAF lower than 0.18% (HR = 32.85, 95% CI 7.92–136.2, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2E). However, it is important to note that a large proportion of patients with undetectable pre-operative ctDNA belonged to the HR+ LowR subgroup; and as expected, none of them experienced recurrence in the duration of this study. Therefore, the hazard ratios calculated above for the whole cohort were presumably inflated. We then analyzed only high-risk patients (n = 97) and found that pre-operative ctDNA remained a significant prognostic factor (HR = 6.16, 95% CI 1.98–19.22, p = 0.002). The 24-month DFS rates for highR patients with and without ctDNA detection before surgery were 84.0% and 100% respectively (Fig. 2F). The pre-operative ctDNA positivity or VAF level did not affect the relapse site or lead time (Fig. S3G, H).

In multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, only TNM stage (HR = 1.20, 95% CI 1.09–11.54, p = 0.03) and pre-operative ctDNA status (HR = 3.09, 95% CI 2.65–80.0, p = 0.001) remained statistically significant after adjusting for other pretreatment factors (Table 2). Using TNM stage alone, the 24-month DFS rate was 96.1% and 82.9% for stage I-II and stage III, respectively, regardless of ctDNA status (Table 3). When pre-operative ctDNA information was combined, the 24-month DFS rate was further reduced by ~5% for patients with pre-operative ctDNA(+) status, specifically at 90.7% and 77.8% for stage I-II and stage III, respectively (Table 3). The trend was also the same in the high-risk patients.

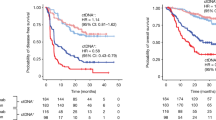

Post-operative ctDNA as a strong independent prognostic factor

After surgery, ctDNA detected at any time point was associated with worse outcome (Table 4). Patients with ctDNA(+) at either landmark (HR = 68.59, 95% CI 9.04–520.6, p < 0.0001) or during surveillance (HR > 1000, 95% CI > 1000, p < 0.0001) had significantly shorter DFS compared to those with ctDNA(-) (Fig. 3A, B). Among high-risk patients, the trend was similar and that ctDNA status during surveillance (HR = 137.9, 95% CI 13.10–1448, p < 0.0001) had stronger prognostic value than landmark ctDNA (HR = 18.11, 95% CI 3.09–106.1, p = 0.001) (Fig. 3C, D). The difference between 24-month DFS of all patients with ctDNA(+) versus ctDNA(-) at landmark (73.3% vs 95.4%) was much less prominent than during surveillance (20.2% vs 99.2%). Moreover, unlike pre-operative ctDNA status, post-operative ctDNA detection was an independent prognostic factor regardless of TNM stage (HR = 207.05, 95% CI 41.38- > 1000, p = 0.001) (Table S2). Subgroup analysis also indicated that surveillance ctDNA was a significant prognostic factor in each BC subtype (Table S3), but the accuracy of this analysis was limited by the small sample size. We next examined ctDNA dynamics post-surgery and post-adjuvant therapy. There was no statistically significant difference in the DFS between the persistently-negative (Neg-Neg) and converted-negative (Pos-Neg) groups, and between the persistently-positive (Pos-Pos) and converted-positive (Neg-Pos) groups (Fig. 3E, Table 4). The Pos-Pos group had strikingly shorter DFS compared to the Pos-Neg group (HR > 1000, 95% CI 136.4- > 1000, p = 0.0009), indicating that clearance of post-operative ctDNA was associated with superior outcome.

Kaplan-Meier (KM) analysis of disease-free survival (DFS) for all patients stratified by post-operative ctDNA status (A) at landmark (2–4 weeks after surgery), and (B) during surveillance (last follow-up visit). KM analysis of DFS for high-risk patients stratified by post-operative ctDNA status (C) at landmark, and (D) during surveillance. E KM analysis of DFS for all patients stratified by the dynamics of post-operative ctDNA. F Swimmer plot showing ctDNA dynamics, adjuvant regimens and clinical outcomes in selected stage-III BC patients who had landmark ctDNA detected. CAF cyclophosphamide-adriamycin-fluorouracil, AC-T adriamycin and cyclophosphamide-trastuzumab, EC-P epirubicin and cyclophosphamide-paclitaxel, TCH-T taxotere-carboplatin-herceptin-trastuzumab.

Landmark ctDNA clearance by SOC was inadequate in stage-III patients

Landmark ctDNA clearance by SOC adjuvant therapy did not occur in all patients, leading to persistently-positive ctDNA and ultimately recurrence. While 100% (4/4) of patients at stage I-II had ctDNA clearance by SOC, only 63.6% (7/11) of patients at stage III responded to SOC adjuvant therapy (Table 3). Among these 11 stage-III patients, we compared different clinical and genetic factors, such as BC subtype, number of tumor, germline mutation and exact adjuvant chemotherapy regimen between the Pos – Pos and Pos – Neg groups (Fig. 3F, Table S4). There did not seem to be a role of the examined factors but analysis was limited by small sample size.

ctDNA-based detection of recurrence was early and accurate

During follow-up visits, serial ctDNA results were compared with clinical outcomes (Fig. S4A). Landmark ctDNA detection had the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy in predicting recurrence of only 50.0%, 87.0%, 33.3%, 93.1%, and 82.8% respectively (Fig. S4B). Surveillance ctDNA detection showed higher sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy at 90.9%, 98.8%, 90.9%, 98.8%, and 97.9%, respectively (Fig. 4A). One patient (ZMB302) was followed up for only 8.9 months after ctDNA detection and possibility of later recurrence could not be ruled out. The positive ctDNA results all preceded clinical diagnosis by a median lead time of 9.7 months (3.3–13.2 months) (Fig. 4B). Neither ctDNA VAF nor ctDNA dynamics seemed to have any correlation with the lead time (Fig. 4C). Neither BC subtypes, stage, nor post-operative ctDNA level and dynamics could predict the relapse sites to be local or distant (Fig. 4D).

A Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy of post-operative surveillance ctDNA status in predicting clinical recurrence. B Lead time from ctDNA detection to clinical diagnosis of recurrence and/or metastasis. C No correlation was observed between lead time and post-operative ctDNA variant allele frequency (VAF) or ctDNA dynamics. D The rate of local recurrence and distant metastasis among BC subtypes, stages, post-operative ctDNA dynamics and ctDNA level. E, F Case study illustration showing longitudinal ctDNA monitoring and clinical outcomes.

Finally, we presented 2 cases to demonstrate the clinical use of ctDNA monitoring. The first patient ZMB115, was a 43-year-old woman diagnosed with HR + HER2 + pT3N2M0 invasive ductal carcinoma. Pre-operative ctDNA was 0.47%, which was cleared at 8 months post-surgery. At the 12-month follow-up visit, ctDNA was detected at 0.18%, ultrasound was negative, and no clinical symptoms. Only at the 24-month visit, neck ultrasound revealed enlarged supraclavicular lymph node and fine-needle aspiration biopsy confirmed supraclavicular lymph node metastasis of BC (Fig. 4E). The second case was patient ZMB130, a 54-year-old woman diagnosed with HR-HER2- pT3N2M0 invasive ductal carcinoma. Similar to the above, ctDNA was detected at 0.08% at the 12-month follow-up visit when ultrasound was negative and no clinical symptoms. MRI imaging later revealed liver and lung metastasis, 9.7 months after ctDNA detection (Fig. 4F).

Discussion

Early risk stratification is increasingly recognized as a key to enable timely delivery of precision medicine. Right after diagnosis is established, physicians often use clinical factors to prognosticate patients and develop treatment plan accordingly. In our analysis, TNM stage was found as the most prognostic clinical factor, consistent with the literature5 and with our data that stage-III patients accounted for 63.6% of the relapse cases. Furthermore, we identified pre-operative ctDNA as the only prognostic genetic factor, and that pre-operative ctDNA positivity reduced an extra 5% in the 24-month DFS rates stratified by the TNM stage. Pre-treatment ctDNA detection has been associated with aggressive breast tumor features previously13 because in general, breast tumors do not readily release ctDNA into the bloodstream like some other types of cancer. This also explains our ctDNA detection rate before surgery to be highest in the more aggressive BC subtypes HER2+ and TNBC, as also observed in other studies14,15. In addition, besides ctDNA detection, pre-operative ctDNA level also had prognostic value as high VAF was associated with poorer outcome. An earlier study by Garcia-Murillas et al. also made the same conclusion but their median VAF cut-off was 0.36% compared to our median VAF of 0.18%16. There has been no absolute cut-off value as it can fluctuate based on the patient cohort as well as the ctDNA analysis platform.

After diagnosis, post-surgery is a critical “actionable” time window when appropriate intervention could change clinical outcomes of patients. Although we found that landmark ctDNA detection had low PPV and sensitivity to predict recurrence, which was expected, the clearance of landmark ctDNA by SOC was found to be associated with superior outcome. While all stage-II patients cleared ctDNA after adjuvant chemotherapy, only 63.6% of stage-III patients, regardless of subtypes, responded to SOC. This suggests that current adjuvant regimens may not be adequate and ctDNA-guided escalation for adjuvant therapy in stage-III BC might be worth exploring in the future. Since stage-III patients accounted for 10–12% of newly diagnosed BC cases and the rate can be higher in developing countries5, such intervention could transform care and improve overall survival for numerous patients. Besides, since the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) has become increasingly popular for early BC17, ctDNA status post-NAC, which is earlier than post-surgery, is being actively studied as a potential predictive biomarker to guide adjuvant therapy11. Unfortunately, at the time of study design and recruitment, NAC was not yet a routine practice in our country; so we are evaluating the ctDNA dynamics during NAC in a separate clinical trial.

After adjuvant therapy and during surveillance, presence of plasma ctDNA was a strong and independent prognostic factor, corroborating findings in previous studies (Table S5). It should be noted that our K-Track assay utilized only a panel of 95 genes and a 4-plex mPCR assay to detect ctDNA in liquid biopsy. This approach is fairly streamlined compared to multiple studies using whole exome sequencing and customized primers/probes for 16–488 mutations18,19,20, which are the major costs of tumor-informed ctDNA testing. Larger gene panels and higher number of mutations to track could improve sensitivity of ctDNA detection, especially for samples with low DNA input, and potentially increase lead time. However, our simplification has advantages of reduced data workload, more high-throughput and lower cost compared to other sophisticated platforms. Although the established limit of detection (LOD) of our assay was 0.05%12,21, lower than some platforms achieving LOD ≤ 0.01%22,23, the clinical performance of our test was non-inferior to previous studies, not only in breast cancer (Table S5) but also in multiple solid tumors24,25. Moreover, although the pre-operative detection rate was less than 50% for the HR+ subtype, we were still able to detect molecular recurrence in 83.3% (5/6) of HR+ patients who eventually relapsed. ctDNA became more easily detectable likely because the recurrent tumors were more aggressive and released more ctDNA into the bloodstream; or in the cases of metastatic recurrence, presence of cancer cells in circulation or distant organs could also enhance ctDNA detection.

A major limitation of our study was small sample size and small number of events, so our findings in subgroup analysis need to be re-evaluated in a larger cohort. In addition, as our ctDNA detection rate before surgery was low for the HR+ lowR group, we could not speculate the performance of our assay to predict late recurrence in this group of patients. Future study design for this group is challenging due to potential issues with tumor availability and quality, sampling frequency for prolonged surveillance up to 20 years after treatment. Finally, we were unable to directly compare ctDNA with more advanced imaging technologies like PET/CT and PET/MRI, or with MRI at all time points, as they were not used routinely in our local practice. However, their sensitivity and specificity to detect local recurrence and distant metastasis were reported to vary below 90%9, which was lower than our ctDNA assay.

In conclusion, ctDNA monitoring holds significant prognostic value at various stages of BC management. Our simplified approach could make ctDNA testing more accessible to adopt in developing countries.

Methods

Patients and sample collection

This was a multi-center prospective clinical study conducted from March 2021 to January 2024 at University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Thu Duc City Hospital and Medical Genetics Institute in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. The study recruited a total of 179 women diagnosed with stage I-III BC and indicated for curative-intent surgery. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were described in detail previously12. Standard-of-care (SOC) treatment was administered to all patients under the supervision of surgical and medical oncology teams. Ultrasound imaging was performed in all follow-up visits. Peripheral blood samples (10 mL) were collected in cfDNA blood collection tubes (Streck Corp, USA) at different time points: 7 days before surgery, 2–4 weeks after surgery (landmark), after adjuvant therapy and at 12- or 18- month follow-up visits (surveillance). Pathologists provided formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples of surgically removed tumors with at least 60% tumor cellularity, along with immunohistochemical (IHC) staining results for hormone receptor (HR) status, including estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR), as well as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). The date of clinical recurrence was determined by CT/MRI imaging or biopsy confirming local recurrence (cancer returning in the same breast area as the original tumor) and/or distant metastasis (cancer spreading to other parts of the body). ctDNA results were not returned to patients and healthcare providers during the study. Patient demographics are in Table 1, and the study design and workflow are illustrated in Fig. 1 (created with BioRender.com).

Patients were categorized into 4 groups based on the IHC status of their tumors: HR + HER2-, HR + HER2 + , HR-HER2 + , HR-HER2-. For the HR+ groups, patients were further stratified into low- and high-risk for recurrence using clinicopathological features established in previous studies3,4. A HR+ patient was defined as clinically high-risk if they met any of the following criteria: 1) a predicted risk of death within 10 years of at least 15% using ePREDICT V2.1 (https://breast.predict.nhs.uk/tool), or 2) a tumor size > 5 cm (T3) regardless of lymph node status, 3) N ≥ 4 lymph nodes, or 4) N = 1–3 lymph nodes with at least one of the following: tumor size > 3 cm, high histological grade 3, or high genomic risk defined as Oncotype Dx Recurrence Score > 26. All HR-HER2+ and HR-HER2- patients were defined as clinically high-risk in this study.

Ethics statement

The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, granting permission for the anonymous utilization of their samples, clinical information, and genomic data for the purposes of this study. Approval for the study was obtained from the institutional ethics committees of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ho Chi Minh City (Approval #: 300/HDDD), and Thu Duc City Hospital (Approval #: 17/HDDD).

Tumor and white blood cell sample processing

FFPE and blood samples were processed following the established procedure of the K-Track assay12,21,26. Tumor somatic variant ranking and multiplex PCR to detect plasma ctDNA were described previously12,21. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) status were determined using a large validated gene panel of 473 genes26.

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables, the Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc Dunn’s test was used for comparisons of more than two groups. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. DFS was defined as the length of time from surgery until the diagnosis of recurrence. Univariable and multivariable analysis was carried out with Cox proportional hazard regression considering all variables to assess the most significant prognostic factor associated with DFS. Survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. All statistical analyses were conducted using Graphpad Prism, and significance was determined at p < 0.05.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

Change history

13 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00825-9

References

Benitez Fuentes, J. D. et al. Global Stage Distribution of Breast Cancer at Diagnosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Oncol. 10, 71–78 (2024).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Sheffield, K. M. et al. A real-world US study of recurrence risks using combined clinicopathological features in HR-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer. Future Oncol. 18, 2667–2682 (2022).

Gómez-Acebo, I. et al. Tumour characteristics and survivorship in a cohort of breast cancer: the MCC-Spain study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 181, 667–678 (2020).

Colleoni, M. et al. Annual Hazard Rates of Recurrence for Breast Cancer During 24 Years of Follow-Up: Results From the International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 927–935 (2016).

Dent, R. et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res 13, 4429–4434 (2007).

Pedersen, A. C. et al. Sensitivity of CA 15-3, CEA and serum HER2 in the early detection of recurrence of breast cancer. Clin. Chem. Lab Med 51, 1511–1519 (2013).

Coombes, R. C. et al. Personalized Detection of Circulating Tumor DNA Antedates Breast Cancer Metastatic Recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res 25, 4255–4263 (2019).

Ming, Y. et al. Progress and Future Trends in PET/CT and PET/MRI Molecular Imaging Approaches for Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 10, 1301 (2020).

Guo, N. et al. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) as prognostic markers of relapsed breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer 4, 63–73 (2024).

Vlataki, K. et al. Circulating Tumor DNA in the Management of Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Cells. 12, 1573–1595 (2023).

Nguyen Hoang, V. A. et al. Genetic landscape and personalized tracking of tumor mutations in Vietnamese women with breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 17, 598–610 (2023).

Cavallone, L. et al. Prognostic and predictive value of circulating tumor DNA during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for triple negative breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 10, 14704 (2020).

Moss, J. et al. Circulating breast-derived DNA allows universal detection and monitoring of localized breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 31, 395–403 (2020).

Magbanua, M. J. M. et al. Circulating tumor DNA in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer reflects response and survival. Ann. Oncol. 32, 229–239 (2021).

Garcia-Murillas, I. et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer. Sci. Transl. Med 7, 302ra133 (2015).

Asaoka, M., Gandhi, S., Ishikawa, T. & Takabe, K. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer: Past, Present, and Future. Breast Cancer (Auckl.) 14, 1178223420980377 (2020).

Parsons, H. A .et al. Sensitive Detection of Minimal Residual Disease in Patients Treated for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 26, 2556–2564 (2020).

Coakley, M. et al. Comparison of Circulating Tumor DNA Assays for Molecular Residual Disease Detection in Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 30, 895–903 (2024).

Lipsyc-Sharf, M. et al. Circulating Tumor DNA and Late Recurrence in High-Risk Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 2408–2419 (2022).

Nguyen, H. T. et al. Tumor genomic profiling and personalized tracking of circulating tumor DNA in Vietnamese colorectal cancer patients. Front Oncol. 12, 1069296 (2022).

Newman, A. M. et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat. Med 20, 548–554 (2014).

Abbosh, C. et al. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature 545, 446–451 (2017).

Nguyen, H. T. et al. Clinical trial and real-world evidence of circulating tumor DNA monitoring to predict recurrence in patients with resected colorectal cancer. ESMO Real World Data. Digit. Oncol. 6, 100076 (2024).

Nguyen Hoang, V.-A. et al. Real-World Utilization and Performance of Circulating Tumor DNA Monitoring to Predict Recurrence in Solid Tumors. JCO Oncol. Adv. e2400084 (2025).

Nguyen Hoang, T. P. et al. Analytical validation and clinical utilization of K-4CARE: a comprehensive genomic profiling assay with personalized MRD detection. Front Mol. Biosci. 11, 1334808 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Gene Solutions, Vietnam. The funder did not have any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T.N., T.V.N., T.H.P., T.C.D., D.H.P., D.S.N., T.T.T.D. recruited patients and performed clinical analysis. V.A.N.H., N.N., H.-N.N., H.G. processed samples and analyzed genetic data. D.N.V. performed some statistical analysis. L.T. conceived and designed the project, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

V.A.N.H., N.N., D.N.V., D.S.N., H.-N.N., H.G. and L.T. are current employees of Gene Solutions, Vietnam. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, S.T., Nguyen Hoang, VA., Nguyen Trieu, V. et al. Personalized mutation tracking in circulating-tumor DNA predicts recurrence in patients with high-risk early breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 11, 58 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00778-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00778-z