Abstract

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is a promising biomarker in early hormone receptor (HR) + , HER2-negative breast cancer. We assessed ctDNA with the RaDaR assay in NeoRHEA (NCT03065621), a single-arm, phase II neoadjuvant palbociclib plus endocrine therapy trial over 4 months (4 × 28-day cycles). Plasma samples were drawn pre-treatment, after cycle 1, pre-surgery, and 1 month post-surgery. Baseline ctDNA was detected in 55%, fell to 5% during treatment, and was undetectable in all patients by 1-month post-surgery. Baseline detection was higher in grade 3 tumors, lower in multifocal/multicentric disease, and higher in residual cancer burden (RCB) 3. MYC gains/amplifications were enriched in ultrasound (US) responders, while PIK3CA gains were enriched in US non-responders; FAT1 losses were enriched in RCB 3. Baseline ctDNA predicted poor response to this regimen, supporting ctDNA as a biomarker to guide treatment in HR + /HER2-negative disease. Trial registration: EU Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT 2016-000879-24; registered 15 February 2017).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative (HR+/HER2−) breast cancer (BC) accounts for ~70% of all BC diagnoses and remains a significant clinical challenge despite advances in treatment strategies1,2.

CDK4/6 inhibitors and endocrine therapy (ET) are standard of care in the treatment of HR + , HER2-negative (HR+/HER2−) advanced BC, as well as high-risk early breast cancer (EBC)3,4. However, not all patients benefit equally from this treatment, and predictive biomarkers to identify those who will achieve an optimal response remain a critical unmet need. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis has emerged as a promising non-invasive biomarker for disease monitoring across multiple cancer types. Several studies have assessed ctDNA for detecting minimal residual disease (MRD), predicting disease recurrence, and assessing treatment response in breast cancer5,6,7,8,9,10. However, ctDNA detection remains challenging in early HR+/HER− breast cancer, characterized by lower proliferation rates and potentially lower ctDNA levels.

Furthermore, while previous research has examined ctDNA dynamics in metastatic breast cancer patients receiving CDK4/6 inhibitors and ET11,12, limited data exist on ctDNA analysis in patients receiving CDK4/6 inhibitors in the early setting. Understanding how these targeted therapies affect ctDNA release and clearance could provide valuable insights into their biological effects and help optimize treatment strategies.

In this work, we investigated the prognostic value of a personalized ctDNA assay for monitoring treatment response in patients included in the NeoRHEA trial, a single-arm, phase II study of neoadjuvant palbociclib and endocrine therapy administered over 4 months (four 28‑day cycles). We evaluated ctDNA dynamics across four different time points, and we explored the association of ctDNA detection with clinical and pathological characteristics, clinical outcome measures and genomic data.

Results

ctDNA detection at baseline is higher in patients with high proliferative rates or unifocal tumors

A total of 100 patients were enrolled in the Neorhea trial, out of which 97 patients were evaluable. Of them, 17 had no available tumor tissue for the design of personalized RaDaR assays and were excluded from the study (Supplementary Information; Fig. S1). Baseline clinicopathological characteristics for the remaining 80 patients are provided in Table S1 (Supplementary Information). A total of 68% of patients were postmenopausal, 79% had cT2 tumors, 66.25% had cN0 tumors, 18.75% had multifocal or multicentric tumors, and 18.75% had histological grade 3 tumors.

WES was successfully performed on the remaining 80 patients to a median coverage of 285× (range: 32×–648×). RaDaR panels were successfully designed for all sequenced tumors with a median of 48 patient-specific variants (range: 18–52). Following panel QC, panels were released for plasma ctDNA profiling with a median of 25 variants (range: 7–48). A total of 312 plasma samples were tested on the designed RaDaR assays. Of them, eight samples from two patients were removed from the analysis due to the number of variants remaining after filtering out those present in control DNA being below the minimum required for sensitive ctDNA detection. A further two samples were removed after failing to amplify successfully. Final analysis included 302 plasma samples from 78 patients (Supplementary Information; Fig. S1). CtDNA was detected in 50/302 tested plasma samples (16.6%) at a median estimated variant allele frequency (eVAF) of 0.026% (range: 0.00099-0.913%). Of the 76 patients with an evaluable baseline sample, ctDNA was detected in 42 of them (55%) at a median eVAF of 0.0227% (range: 0.00116-0.913%). ctDNA was detected in 4/76 patients at C1D28 (5%) and in 4/75 patients prior to surgery. Of them, 3 patients were ctDNA positive at both C1D28 and prior to surgery. None of the 76 patients were found to be ctDNA positive one month post-surgery (EoS). ctDNA detection per timepoint and per patient (for all tested samples) is shown in Figs. 1, 2, respectively. Out of the 69 patients with evaluable ctDNA results at all four timepoints, 30 (49%) had no ctDNA detection at any timepoint (group 1). Of the remaining 39 patients (all ctDNA-positive at baseline), 34 were negative at all subsequent timepoints (Group 2), whereas 5 (Group 3) had a subsequent positive sample (1 at C1D28, 1 before surgery and 3 at both timepoints).

A The number of patients assessed by the RaDaR assay (y axis) across four time points (x axis). Patients with ctDNA detection are colored in red (ctDNA = positive), patients with no ctDNA detection are colored in blue and patients with unavailable ctDNA detection are colored in gray. The numbers on each colored bar represent the absolute number of patients in each category. B Associations of the percentage of patients detected as ctDNA positive at baseline against baseline clinicopathological characteristics.

A Patients with positive ctDNA (42) at baseline, follow-up period expressed in days. Circles represent ctDNA testing, with empty circles denoting ctDNA-negative and black circles, ctDNA-positive samples. Relapse patients (n = 3) are marked with a red/pink line (distant/locoregional) and the time of relapse with a red triangle. Surgery timepoint is marked with a vertical green line. Baseline clinicopathological features-histological grade and multifocal/multicentric status-as well as the RCB class assessed at surgery, are displayed for each patient on the left side of the y axis. B Patients with negative ctDNA (n = 34) at baseline, follow−up period expressed in days.

At baseline, ctDNA was detected in 72.7% of patients with clinical nodal status N1 versus 48.1% of those with N0. Detection rates were higher in postmenopausal than in premenopausal women (59.6% vs. 45.8%). At baseline, ctDNA was positive in 70% of patients with cT3 tumors, 57.1% of those with T1c lesions, and 52.5% of patients with T2 tumors. Notably, baseline ctDNA detection rates were higher in patients with histological grade 3 tumors (84.6% in G3 vs. 53.7% in G1/G2) and lower in those with multifocal or multicentric tumors compared to patients with unifocal tumors (26.6% vs. 53.6%, respectively, Fig. 1B).

ctDNA detection at baseline is associated with residual tumor burden (RCB 3) at surgery

Association between ctDNA detection and treatment resistance was evaluated. A total of 26 (32.5%), 36 (45%) and 13 (16.25%) patients, respectively, presented RCB 3 at surgery, no ultrasound response following the neoadjuvant treatment, and absence of CCCA at surgery (Supplementary Information; Table S2). Because there were only three patients with RCB0/1 in our cohort (RCB0 = 0; RCB1 = 3), we grouped RCB as RCB3 vs RCB0–2 to preserve statistical power.

Patients with ctDNA detection at baseline had an increased probability of having RCB 3 at surgery. No association was observed between ctDNA detection at any other timepoint and any outcome measure (Supplementary Information; Table S2). When focusing on patient groups based on ctDNA detection at baseline, C1D28 and surgery (69 patients), patients in group 2 (patients with ctDNA clearance) and group 3 (patients with ctDNA persistence) had a significantly higher probability of having RCB 3 compared to group 1 (ctDNA-negative patients across all time points) (Table 1). No other associations between these groups and outcome measures were observed.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value (PPV, NPV) of ctDNA detection at baseline by the ctDNA assay to predict clinical outcome were then evaluated. The performance varied depending on the clinical outcome against which it was measured. For CCCA, the assay’s sensitivity (43%), specificity (47%) and PPV are low (21%); by contrast, its NPV of 71% suggests that a ctDNA-negative result at baseline is associated with increased likelihood of CCCA (Table 2). For RCB, the assay performed more robustly: with a sensitivity of 76%, it correctly identified most patients who will have RCB3, and although its specificity remains moderate at 55%, a negative ctDNA result at baseline was associated with increased likelihood of absence of RCB3 (NPV: 82%). Conversely, the PPV of 45% remained modest. For ultrasound response, the assay’s discriminative power was weak (Table 2).

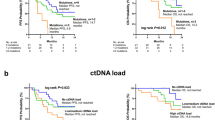

With a median follow-up of 3.8 years (range: 1–5 years), four patients experienced distant recurrences, and one patient had a locoregional recurrence. Patients who were ctDNA-positive at baseline experienced three out of five recurrences (one locoregional and two distant), with one of them with distant recurrence also being tested ctDNA-positive at C1D28. Notably, the log-rank test for the Kaplan-Meier curves assessing BCFS at the C1D28 timepoint was statistically significant; however, this finding is driven by a single event and should be interpreted with caution, warranting further validation. Among patients who were ctDNA-negative at all time points, there were two patients who experienced a relapse (Fig. 2, Supplementary Information; Fig. S2).

Genomic aberrations associated with ctDNA detection, clinical features, outcome measures and recurrence

We then performed copy number alteration (CNA) and single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) analysis on 80 patients out of the 98 included in the NeoRHEA study using WES data from baseline tumor samples. We mapped CNA segments to cancer-relevant genes from the COSMIC database13 and assessed their associations with baseline clinicopathological features, baseline ctDNA detection and clinical outcomes (Fig. 3). The full list of genes analyzed for associations with CNA losses, CNA gains, and SNVs is provided in Table S3–S5. We found that loss of MTOR and CDH1, was more common in patients with lobular carcinoma, and patients with histological grade G3 tumors were more likely to have RB1 loss compared with patients with histological grade G1–G2 tumors (Table S3). MYC and CCNE1 gains and RB1 losses were detected in 32% (26/80), 15% (12/80) and 15% (12/80) of patients, respectively and were more frequent in grade 3 tumors (Table S4). We found FAT1 losses and PIK3CA gains in 9% and 13% of patients and no association with any baseline characteristic. We found no association between CNAs and ctDNA detection at baseline (Table S3, S4). When assessing associations between CNAs and outcome measures, we found MYC gene gains or amplifications to be more frequent in US responders (Table S4) and patients that relapsed, while PIK3CA gains were more common in US non-responders (Table S4). Additionally, FAT1 losses were more frequently observed in patients with RCB 3 (Table S3).

Then, we searched for SNVs and short insertions and deletions (SNVs) and identified a median of 24 variants per sample range (1–1423 variants) (Supplementary Information; Fig. S3). Mutations in the PIK3CA, CDH1 and TP53 genes were detected in 39%, 18%, and 16% of patients, respectively (Fig. 4). We investigated associations between genes mutated in at least 10% of patients and baseline clinicopathological characteristics and found that PIK3CA mutations were more common in tumors with Ki67 at baseline <20% (Table S5). We found no associations between any SNVs and ctDNA detection at baseline (Table S5). Mutations in the TTN gene were found to be associated with ultrasound response and relapse, while no other mutations showed significant associations with relapse or CCCA.

Discussion

This study explored ctDNA dynamics and genomic alterations, along with their clinical significance, in women with HR+/HER2− early breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant treatment Palbociclib and ET as part of the NeoRHEA trial.

Although monitoring early-stage HR+/HER2− breast cancer through liquid biopsy remains challenging due to the typically low tumor DNA fraction in circulation14,15, the RaDaR assay detected ctDNA in 55% of patients at baseline. It is worth noting that baseline ctDNA positivity levels in our cohort (55%) were higher than those observed in patients treated with neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in the I-SPY2 EOP trial16, where 35.6% of patients with Stage 2/3 HR+/HER2− breast cancer (including both MammaPrint low and high-risk signatures) had detectable ctDNA at baseline. The I-SPY2 cohort demonstrated associations between baseline ctDNA positivity and nodal involvement (64% vs 40% in ctDNA-negative patients, p = 0.036), higher Ki67 levels (p = 0.03), and larger functional tumor volume by MRI (p = 0.03).

However, it is difficult to determine why the detection rates differ between the two studies, given the small sample sizes in both trials (76 evaluable patients in NeoRHEA vs 101 in I-SPY2 EOP). Small sample sizes can significantly impact the precision of detection rate estimates, making it difficult to assess the true sensitivity of ctDNA assays and to determine whether observed differences reflect true biological or technical variations versus sampling variability.

Analysis of ctDNA dynamics across the four timepoints and associations with clinical significance aimed to assess its potential as a biomarker for treatment monitoring and residual disease detection. At C1D28, ctDNA was detectable in 5% of patients (4/76), dropping from 55% at baseline (42/76 patients). This decrease in ctDNA detection and the absence of detectable ctDNA at the end of the study could be due to reduced tumor burden or low cell proliferation after treatment, but it could also be due to technical factors related to the sensitivity and the reproducibility of the assay in this setting. Persistent ctDNA in 5% (4/75) of patients before surgery suggests the need for additional interventions. Although the small patient cohort limits the survival analysis to a primarily qualitative interpretation, similar findings from a study on high-risk early breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant I-SPY 2 trial further support the need for additional validation8.

Consistent with previous findings5, patients with histological grade 3 tumors are more likely to test ctDNA positive at baseline. This aligns with the aggressive nature of higher-grade tumors, which are characterized by greater genomic instability and elevated proliferation rates5. The lower ctDNA detection rates observed in patients with multifocal or multicentric tumors (p = 0.01) could be attributed to the challenges of different clonal origins in bilateral or multifocal tumors. We sequenced a single tumor focus, as in the previous study17. Future studies may consider the inclusion of multiple tumor foci in the generation of tumor-informed assays to increase ctDNA detection in this subset of patients.

Analysis of patients grouped by ctDNA detection indicates that patients within Group 2 and Group 3 are more likely to have RCB 3 at surgery compared to Group 1. Groups 2 and 3 both have ctDNA detection at baseline, and this might be more relevant for the association with RCB as opposed to ctDNA dynamics in this setting. Taken together, our findings suggest that the RaDaR ctDNA assay may be more valuable when used adjunctively, particularly for ruling out RCB3 after neoadjuvant endocrine therapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors. Of note, such an approach of neoadjuvant endocrine treatment plus CDK4/6 inhibitors is being tested in clinical trials, but it is not part of the standard of care18. Ultimately, the ctDNA assays could complement—rather than replace—established imaging assessments. Zhou et al.19 investigated the potential of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) as a minimally invasive biomarker for assessing treatment response during neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NST) in early breast cancer patients. They developed a personalized ctDNA assay and tracked ctDNA in plasma samples collected at baseline, mid-therapy, and end of treatment, correlating ctDNA detection with pathological response measures and tumor characteristics. They found that mid-therapy ctDNA detection significantly correlated with higher RCB scores (OR = 0.062; 95% CI, 0.01–0.48; P = 0.0077) and nearly all patients (96.8%) with detectable ctDNA at mid-therapy were non-responders with RCB 2/3. Another two studies12,20 on patients with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) receiving neoadjuvant treatment, used highly sensitive personalized assays and reported ctDNA association with RCB. Stecklein et al. show that post-treatment ctDNA detection in TNBC patients with residual disease correlates with increasing RCB class (14% in RCB-I, 31% in RCB-II, 57% in RCB-III) and independently predicts inferior outcomes, with ctDNA-positive patients demonstrating significantly reduced 3-year event-free survival (48% vs 82%) and overall survival (50% vs 86%) compared to ctDNA-negative patients. Parsons et al. analyzed responders (RCB 0/1) and matched non-responders (RCB 2/3) patients using ctDNA detection on plasma samples before, during and at the end of therapy. They showed that ctDNA clearance at the end of treatment correlated with RCB, with most of the RCB 0 patients testing ctDNA-negative (10/11 patients) and all the patients with RCB 3 testing ctDNA positive (0/4 patients). This can provide an early endpoint of treatment efficacy to guide clinical decisions regarding treatment approaches while using a minimally invasive method.

Additional context is provided by the monarchE adjuvant trial21, in which circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis was performed in 910 patients with HR+, HER2-negative, node-positive, high-risk early breast cancer who were treated with either abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone. As monarchE was an adjuvant trial, their baseline ctDNA measurements—taken post-surgery—correspond to our end-of-study (EoS) timepoint, which was also one month after surgery. Notably, while we observed 0% ctDNA positivity at the EoS timepoint, the monarchE trial reported an 8% baseline ctDNA positivity rate (70 of 910 patients). This discrepancy may be explained by the substantially larger sample size in monarchE (910 vs. 76 evaluable patients in our study), which affords greater statistical power to detect low-frequency ctDNA-positive cases that might be missed in smaller cohorts. Time point, which was also one month after surgery. Notably, while we observed 0% ctDNA positivity at the EoS timepoint, the monarchE trial reported an 8% baseline ctDNA positivity rate (70 of 910 patients). This discrepancy may be explained by the substantially larger sample size in monarchE (910 vs. 76 evaluable patients in our study), which affords greater statistical power to detect low-frequency ctDNA-positive cases that might be missed in smaller cohorts.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess ctDNA detection in patients with early breast cancer treated with endocrine therapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors. The drop in ctDNA detection rates between baseline and subsequent timepoints may be due to decreased proliferation following this treatment.

The analysis of CNA and somatic mutations in cancer-relevant genes, along with their associations with clinicopathological characteristics and treatment outcomes, offers insights into the genetic landscape specific to ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. WES analysis on tumor biopsy samples showed alterations in several genes associated with breast cancer. CNA analysis showed that MTOR and CDH1 loss is associated with lobular breast cancer22, but also alterations in genes known to be associated with treatment resistance, such as RB1, FAT1, and CCNE123,24,25. The observed frequency of CDH1 alterations (50%) is consistent with findings from a previous study26 showing that CDH1 loss is a hallmark of breast invasive lobular carcinoma. MYC and CCNE1 gains, along with RB1 losses, are more commonly observed in patients with histological grade 3 tumors, suggesting a link to increased genomic instability and tumor aggressiveness27. Previous cell line studies indicated that MYC overexpression induces resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors28. Interestingly, in our cohort, patients with MYC-amplified tumors were more likely to respond to ultrasound assessment. This difference might arise from differences between preclinical models and studies on patient tumors, but also due to the relatively low number of patients analyzed in this study. Tumors with FAT1 loss were more likely to have RCB 3 at surgery, and previous studies have also suggested that FAT1 loss may contribute to resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors15, and a high RCB is indicative of a poor treatment response. SNV analysis identified PIK3CA and TP53 mutations as being amongst the most frequent, occurring in 39% and 16% of patients, respectively. No associations were observed between the detection of these mutations and clinical outcome measures. Moreover, no association was found between ctDNA detection at baseline and genomic aberrations. This may be attributed to the limited sample size, as well as the fact that ctDNA detection is influenced by multiple factors, including tumor burden and the biological characteristics of the tumor.

This study has some limitations, such as the relatively low number of patients and rather short follow-up period (median: 3.8 years, range: 1–5 years), which may not allow capturing long-term outcomes, including late relapses. Multifocal tumors represented 20% (15/78) of the cohort undergoing ctDNA testing, and this limits the ctDNA assay sensitivity. Moreover, assessing ctDNA detection only once after surgery (after one month) and not serially during follow-up is compromising the association between ctDNA dynamics and disease recurrence, since it is known that the median lead time between ctDNA detection and disease relapse is ~1 year29. Given the small number of patients with RCB 0/1 (RCB0 = 0; RCB1 = 3), we grouped RCB as RCB3 vs RCB0–2 to preserve power. While this contrast highlights patients with extensive residual disease, in larger cohorts an RCB0–1 vs RCB2–3 dichotomy may be more clinically informative, reflecting the similarity of outcomes between RCB0 and RCB1 and the escalation of risk from RCB2 onward.

Finally, alternative ctDNA detection strategies could enhance both sensitivity and sample inclusion.

Although techniques such as ddPCR offer high analytical sensitivity, they interrogate only one or two predefined mutations per assay, whereas RaDaR employs a multiplexed NGS strategy to track up to 48 patient‑specific variants, increasing the sensitivity of detection. Prior evaluations have suggested improvements in ctDNA detection rates and lead times with RaDaR compared to ddPCR, but the small sample sizes and high concordance (often >90%) between the two methods mean that these differences should be interpreted cautiously30. Building on this evolution, approaches based on whole-genome sequencing of the primary tumor may increase the sensitivity and power of ctDNA analysis. By leveraging comprehensive, tumor-informed platforms—ranging from phased-variant enrichment sequencing to multiplex dPCR of structural variants—that interrogate extensive sets of patient-specific genomic alterations, MRD assays can attain analytical sensitivities in the single-digit parts-per-million range with specificity exceeding 99.9%, enabling earlier and more sensitive ctDNA detection. Several whole-genome sequencing–based tumor-informed approaches have similarly demonstrated improved clinical sensitivity in early-stage breast cancer settings, both before and after surgery. It will be important to assess WGS-based methods in a CDK4/6 inhibitor-treated cohort to recognize the potential benefits14,31,32,33,34,35. Approaches based on tumor-agnostic methods—though generally less sensitive—could broaden patient inclusion36,37. Notably, 20% of patients were excluded from the study due to unavailable tumor biopsies or insufficient variants identified by whole-exome sequencing for plasma calling.

This study provides insights into ctDNA dynamics, genomic alterations, and their associations with clinical outcome in ER-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer treated with palbociclib and ET. Larger studies with longer follow-up in patients receiving adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitors are warranted to validate our findings and guide personalized treatment strategies.

Methods

Human subjects and sample collection

Blood and tumor samples were collected as part of the NeoRhea trial (NCT03065621), an open-label, multi-center, single-arm, phase 2 study involving pre- or postmenopausal female patients diagnosed with ER-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer. Participants received four cycles of palbociclib at a dose of 125 mg (administered from Day 1 to Day 21 in each cycle, followed by a one-week rest period), combined with continuous ET (administered from Day 1 to Day 28 of each cycle).

The endocrine therapy was determined according to the menopausal status of the patient evaluated at the study screening. For postmenopausal patients, endocrine therapy consisted of letrozole 2.5 mg continuously. For pre-menopausal or peri-menopausal patients, endocrine therapy consisted of tamoxifen 20 mg continuously, combined or not with goserelin 3.6 mg monthly at the local investigator’s discretion. The primary objective was to identify biomarkers of no response by locally-assessed ultrasound (US) using RNA-seq on baseline (pre-treatment) tumor biopsies. Patients with no US response to treatment (US non-responders) were defined as those with stable or progressive disease (SD or PD) at post-treatment US (prior to surgery) based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria38. US responders were defined as patients with partial or complete response (PR or CR) at post-treatment US according to WHO criteria. Secondary endpoints included residual cancer burden (RCB) of 3 and absence of complete cell cycle arrest (CCCA), defined as a Ki67 index > 2.7% at surgery based on immunohistochemistry (IHC) evaluation, as well as ctDNA monitoring39,40. Post-surgery follow-up was conducted as part of the clinical routine. Blood draws were performed before and after surgery, together with standardized clinical and laboratory examinations. IHC > 2.7% at surgery as well as ctDNA monitoring39,40. Post-surgery follow-up was conducted as part of the clinical routine. Blood draws were performed before and after surgery, together with standardized clinical and laboratory examinations.

Patients were enrolled between 05/07/2017 and 28/03/2019 in five sites in Belgium, with the cut-off follow-up date of 01/02/2023.

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. The NeoRHEA trial was approved by the Comité d’éthique hospitalo-facultaire Erasme-ULB (2016-000879-24) and the Federal Agency for medicines and health products (Belgium).

The study design and conduct complied with all relevant regulations regarding the use of human study participants and was conducted in accordance with the criteria set by the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed written informed consent before inclusion.

The NeoRHEA trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) (ID: NCT03065621) and on the EU Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT 2016-000879-24; registered 15 February 2017).

Tumor biopsy and plasma samples

Baseline biopsy samples were obtained before Day 1 of Cycle 1 (pre-treatment biopsy), along with a whole blood sample. Blood samples for plasma processing were collected after enrollment and pre-treatment (BL), before Day 1 of Cycle 2 (C1D28), on the day of surgery (prior to surgery), and one month post-surgery at the end of study (EoS) visit.

RaDaR assay for ctDNA detection

The personalized RaDaR assay (NeoGenomics) was utilized for ctDNA detection. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed on tumor DNA extracted from baseline FFPE tumor biopsies, followed by the personalized assay development using tumor, plasma and normal DNA in order to track up to 48 patient-specific, somatic variants in plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA). ctDNA analysis was performed retrospectively on batched collected samples.

WES sequencing and design of personalized RaDaR assays

Tumor DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) biopsy specimens obtained at baseline using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit (Qiagen) and was sent to NeoGenomics for WES. Following WES, patient-specific somatic variants were prioritized using a proprietary algorithm and used to design personalized RaDaR assays (NeoGenomics) of up to 48 amplicons each, capturing at least one such somatic variant.

Plasma processing and ctDNA profiling

Circulating cfDNA was extracted at NeoGenomics Laboratories Inc. (Durham, NC) from a median plasma volume of 3.4 mL (range 0.55-5.2 mL) using a solid-phase reverse immobilization magnetic bead protocol on a Hamilton Microlab STAR (RRID:SCR_019993) automated platform. A no-template control sample was included in each extraction batch to monitor for contamination. Following panel qualification using the same tumor DNA used in WES, plasma cfDNA samples were amplified by multiplex PCR on the qualified personalized RaDaR assays alongside a matched buffy coat sample serving as a positive amplification control. The inclusion of the buffy coat control sample also ensured that germline variants, as well as those associated with mosaicism and age-related clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) variants, were excluded from the plasma calling process to eliminate the possibility of false positive results.

Negative and positive amplification controls were included in each RaDaR batch run to rule out amplification due to contamination and ensure amplification efficiency, respectively. The resulting amplification libraries were then subjected to ultra-deep sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Data analysis involved demultiplexing raw binary sequencing base calls (bcl format) into FASTQ files with the bcl2fastq 2.20 tool (RRID:SCR_015058), alignment via Burrows-Wheeler Aligner(bwa-mem)41 (RRID:SCR_022192), and proprietary software processing to identify primer pairs and count mutant/reference bases. Variants found in buffy coat material or those not being validated in tumor DNA, were excluded from the plasma calling process.

As previously described9,42,43, plasma ctDNA detection employed proprietary methods that used a statistical model to evaluate the significance of observed mutant counts for each variant. This information was integrated across all personalized variants to determine tumor presence or absence. A sample was classified as ctDNA-positive when its cumulative statistical score exceeded a predetermined threshold defined during RaDaRs analytical validation.

Normal DNA extraction sequencing for primary tumor copy number and single-nucleotide variation analysis

Normal DNA was extracted from white blood cells (WBC) with QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit (50) and was sent to the BrightCORE facility for sequencing. The libraries were constructed using 150 ng of input DNA with the KAPA HyperPlus kit (Roche Sequencing, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s recommendations, with three modifications: (1) an enzymatic fragmentation for 20 min at 37 °C was used to obtain average DNA insert sizes of 200 bp, (2) the usage of 15 µM of our in-house designed UDI/UMI adapters and (3) a total of eight PCR cycles were applied to get sufficient libraries for target enrichment. A maximum of eight samples were pooled at equal mass for a total of 2400 ng and captured using 4 µl xGen™ Exome Hyb Panel v2 and

1 µl of a custom spike-in probe set (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa, USA) to enrich for more difficult target regions in the “Belgian Genetic Expanded Carrier Screening” (BeGECS) genelist. For this, version 5 of the “xGen™ hybridization capture of DNA libraries” manual was followed. A total of seven post-capture PCR cycles was needed to yield sufficient libraries for sequencing. Final libraries were qualified on the AATI Fragment Analyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), using the DNF-474 High Sensitivity NGS Fragment Analysis Kit (Agilent Technologies Inc., CA, USA) and quantified on the Qubit 2.0 with the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies, CA, USA). Per sample, a minimum of 58 million 2 × 100 bp reads were generated on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina Inc., CA, USA), with the NovaSeq 6000 S4 Reagent Kit (200 cycles) to obtain a minimum average coverage of ×100. For this, 1 nM libraries were denatured according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Genomic data preprocessing and quality control

Data obtained from sequencing baseline tumor biopsy samples at NeoGenomics was pre-processed and aligned using a proprietary pipeline. The WBC sequencing data were provided by the BrightCORE facility as paired-end FASTQ files. FASTQ files were processed by TRIMMOMATIC v.0.38(RRID:SCR_011848)44 to remove adapters and low-quality reads (True LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 MINLEN:36). The trimmed reads were aligned to the human reference genome (hg38) with bwa-mem software package v.0.7.1741 (RRID:SCR_022192) and sorted by coordinates with samtools v.1.1045 (RRID:SCR_002105). The duplicates were marked with sambamba v.0.8.246, and coverage calculation was performed with mosdepth v.0.3.347.

Copy number and single-nucleotide variation bioinformatic analysis

Copy number(CN) alterations (CNAs) were calculated with FACETS v.0.6.248. Before running FACETS (RRID:SCR_026264), snp-pileup(params -g -q15 -Q20 -P100 -r25,0) was executed to calculate reference and variant allele read counts from BAM files for germline polymorphic sites from dbSNP database(RRID:SCR_002338). For each sample, the integer CN calculated by FACETS was normalized by the average total copy number of the sample, which is modeled as the sum of the tumor contribution(given by the product of the tumor purity and tumor ploidy) and the normal cells contribution(given by (1-purity) multiplied by 2). The normalized CN were scaled by 2, to bring the normalized CN onto a diploid reference scale. Deletions were defined as CN < 1, amplifications as CN > 3.2 and gains as CN > 5.2. The CN analysis and visualization were done with a custom R script. FACETS was run for different values of the cVAL parameter (segmentation parameter), and the one that resulted in the least noisy output was selected. The genes from COSMIC database49 (RRID:SCR_002260) were mapped on the FACESTS CNA segments to extract the CNA information at the gene level.

Somatic SNVs and small insertions and deletions(indels) were calculated with Manta v1.6.050 (RRID:SCR_022997) and Strelka v2.9.213 (RRID:SCR_005109) using matched tumor and WBC WES. As per Strelka2 recommendations, Manta was run as the first step to increase the indel calling certainty. Gene-based (RefSeq genes (RRID:SCR_003496), UCSC genes, ENSEMBL genes(RRID:SCR_006773)) and filter-based (dbSNP, 1000 Genome Project(RRID:SCR_008801), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) or Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD, RRID:SCR_014964), COSMIC49) annotation was performed with ANNOVAR51 (RRID:SCR_012821) on both SNVs and indels calculated by Strelka2. The variants passing Strelka2’s default filters are further refined as to exclude variants with: (1) low depth (10 for normal depth and 25 for tumor depth), (2) low variant allele frequency (VAF) on tumor (<1%) or high normal samples VAF (higher than 1%), (3) variants found in general population (e.g., ExAC, gnomAD) with a VAF higher than 0.01% (4) variants found more than two times in Neorhea, but not in COSMIC database49, variants that occur in >60% of the samples. The oncoplots were generated using MAFTools52 (RRID:SCR_024519).

Statistical analysis

The Fisher exact test was used to compare the number of ctDNA-positive patients against baseline clinicopathological characteristics and outcome measures, including CCCA, US response, RCB (0, 1, 2 vs 3).

Statistical comparisons were performed to address the following research questions: (1) Are patients with ctDNA clearance (Group 2) or persistent ctDNA positivity (Group 3) more likely to have RCB 3 compared to patients who remain consistently ctDNA-negative (Group 1)? (2) Are patients in Groups 2 and 3 less likely to achieve US response compared to Group 1? (3) Are patients in Groups 2 and 3 less likely to achieve CCCA at surgery compared to Group 1? For all analyses, Group 1 served as the reference group with odds ratios and p-values calculated using Fisher’s exact test to compare each group against this reference.

Baseline ctDNA detection was compared with three clinical outcomes—RCB 0–2 vs. RCB 3, US Responders vs. US Non‑responders and CCCA, defined at surgery by Ki‑67 > 2.7% vs. no CCCA defined as Ki‑67 ≤ 2.7%—after excluding any cases with missing ctDNA or outcome data. For each outcome, we tabulated true and false positives (TP/FN) and true negatives and false positives (TN/FP), to calculate the following performance metrics: sensitivity (TP/[TP + FN]), specificity (TN/[TN + FP]), positive predictive value (PPV; TP/[TP + FP]) and negative predictive value (NPV; TN/[TN + FN]). All metrics were rounded to three decimal places.

Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the association between the number of patients with CNA gains/CNA losses/SNVs on specific genes and baseline clinicopathological characteristics and outcome measures. The odds ratio was calculated whenever possible, and the correction for multiple testing was done with the Benjamini & Hochberg method (represented by the FDR column across all tables containing odds ratios).

Survival analysis was visualized using Kaplan–Meier curves. The breast cancer free survival (BCFS) event was defined as locoregional and distant relapse, and the time was calculated from the date of first blood sample collection until the date of relapse. Due to the limited sample size, the results were primarily qualitative.

Statistical analysis was performed with Python 2.7.13(RRID:SCR_008394) and R version 3.4.2 (RRID:SCR_001905).

Results were reported according to the remark guidelines53.

Data availability

The raw and processed data generated in this study have been deposited at the Data Centre at Institut Jules Bordet in Brussels (Belgium) and can be made available upon approval of a research proposal. Any request for data (e.g., individual de-identified participant data, additional study documents including study protocol and/or statistical analysis plan) will be reviewed by the study team and should be addressed to Michael Ignatiadis, [michail.ignatiadis@hubruxelles.be](mailto:michail.ignatiadis@hubruxelles.be). Restrictions may apply to requests from industry or for commercial purposes. The expected timeframe for response to access requests is 6 months. Once access has been granted, the data will be available for 12 months (extendible upon approval). The scripts used to generate the analysis and the figures presented in the paper can be found here: https://github.com/MIgBCLab/RaDaRPaperAnalysis.

Code availability

The scripts used to generate the analysis and the figures presented in the paper can be found here: https://github.com/MIgBCLab/RaDaRPaperAnalysis.

References

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 136, E359–E386 (2015).

Ignatiadis, M. & Sotiriou, C. Luminal breast cancer: from biology to treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 10, 494–506 (2013).

Ma, C. X. et al. NeoPalAna: Neoadjuvant Palbociclib, a Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitor, and Anastrozole for Clinical Stage 2 or 3 Estrogen Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 4055–4065 (2017).

Hurvitz, S. A. et al. Potent cell-cycle inhibition and upregulation of immune response with abemaciclib and anastrozole in neoMONARCH, Phase II neoadjuvant study in HR+/HER2− breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 566–580 (2020).

Elliott, M. J. et al. Longitudinal evaluation of circulating tumor DNA in patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy for early breast cancer using a tumor-informed assay. Nat. Commun. 16, 1837 (2025).

Rothé, F. et al. Circulating tumor DNA in HER2-amplified breast cancer: a translational research substudy of the NeoALTTO Phase III trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 3581–3588 (2019).

Coombes, R. C. et al. Personalized detection of circulating tumor DNA antedates breast cancer metastatic recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 4255–4263 (2019).

Magbanua, M. J. M. et al. Clinical significance and biology of circulating tumor DNA in high-risk early-stage HER2-negative breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Cell 41, 1091–1102.e4 (2023).

Lipsyc-Sharf, M. et al. Circulating tumor DNA and late recurrence in high-risk hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 2408–2419 (2022).

Lynce, F. et al. Adjuvant nivolumab, capecitabine or the combination in patients with residual triple-negative breast cancer: the OXEL randomized phase II study. Nat. Commun. 15, 2691 (2024).

Martínez-Sáez, O. et al. Circulating tumor DNA dynamics in advanced breast cancer treated with CDK4/6 inhibition and endocrine therapy. NPJ Breast Cancer 7, 8 (2021).

Parsons, H. A. et al. Circulating tumor DNA association with residual cancer burden after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer in TBCRC 030. Ann. Oncol. 34, 899–906 (2023).

Kim, S. et al. Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nat. Methods 15, 591–594 (2018).

Ignatiadis, M., Sledge, G. W. & Jeffrey, S. S. Liquid biopsy enters the clinic—implementation issues and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 297–312 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Clinical significance of circulating tumor DNA in neoadjuvant-treated HER2-negative luminal B breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, e12616 (2024).

Alkhafaji, S. et al. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in patients with stage 2/3 HR+ HER2‑negative breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in the I‑SPY2 Endocrine Optimization Pilot (EOP) trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 43, 3008 (2025).

Cailleux, F. et al. Circulating tumor DNA after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer is associated with disease relapse. JCO Precis Oncol. 6, e2200148 (2022).

Brandão, M. & Ignatiadis, M. CDK4/6 inhibitors as neoadjuvant treatment in breast cancer-what can we learn?. Ann. Oncol. 29, 2274–2278 (2018).

Zhou, Q. et al. Persistence of ctDNA in patients with breast cancer during neoadjuvant treatment is a significant predictor of poor tumor response. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 697–707 (2022).

Stecklein, S. R. et al. ctDNA and residual cancer burden are prognostic in triple-negative breast cancer patients with residual disease. NPJ Breast Cancer 9, 10 (2023).

Loi, S. et al. Prognostic utility of ctDNA detection in the monarchE trial of adjuvant abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy in HR+, HER2‑, node‑positive, high‑risk early breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, LBA507 (2024).

Desmedt, C. et al. Genomic characterization of primary invasive lobular breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 1872–1881 (2016).

Kumarasamy, V. et al. RB loss determines selective resistance and novel vulnerabilities in ER-positive breast cancer models. Oncogene 41, 3524–3533 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Loss of the FAT1 tumor suppressor promotes resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors via the Hippo pathway. Cancer Cell 34, 893–905.e8 (2018).

Zhao, Z. M. et al. CCNE1 amplification is associated with poor prognosis in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer 19, 96 (2019).

Dopeso, H. et al. Genomic and epigenomic basis of breast invasive lobular carcinomas lacking CDH1 genetic alterations. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 33 (2024).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490, 61–70 (2012).

Ma, J. et al. MYC induces CDK4/6 inhibitors resistance by promoting pRB1 degradation. Nat. Commun. 15, 1871 (2024).

Pantel, K. & Alix-Panabières, C. Minimal residual disease as a target for liquid biopsy in patients with solid tumours. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 22, 65–77 (2025).

Coakley, M. et al. Comparison of a personalized sequencing assay and digital PCR for circulating tumor DNA based molecular residual disease detection in early-stage triple negative breast cancer in the cTRAK-TN trial. Cancer Res. 83, PD5–PD03 (2023).

Zviran, A. et al. Genome-wide cell-free DNA mutational integration enables ultra-sensitive cancer monitoring. Nat. Med. 26, 1114–1124 (2020).

Northcott, J. et al. Analytical validation of NeXT Personal®, an ultra-sensitive personalized circulating tumor DNA assay. Oncotarget 15, 200–218 (2024).

Garcia-Murillas I. et al. Whole genome sequencing-powered ctDNA sequencing for breast cancer detection. Ann Oncol. 36, 673–681 (2025).

Cabel L. et al. Ultra-sensitive ctDNA detection and monitoring in early breast cancer using PhasED-Seq. Poster 293P presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress; September 8–12 (Munich, Germany, 2024).

George A. M. et al. NeoCircle: circulating tumor DNA dynamics during neoadjuvant chemotherapy predict survival in primary breast cancer. Poster presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting (Chicago, IL, 2025).

Bruhm, D. C. et al. Genomic and fragmentomic landscapes of cell-free DNA for early cancer detection. Nat. Rev. Cancer 25, 341–358 (2025).

Panet, F. et al. Use of ctDNA in early breast cancer: analytical validity and clinical potential. NPJ Breast Cancer 10, 50 (2024).

Miller, A. B., Hoogstraten, B., Staquet, M. & Winkler, A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer 47, 207–214 (1981).

Symmans, W. F. et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 4414–4422 (2007).

Bedard, P. L. et al. Low residual proliferation after short-term letrozole therapy is an early predictive marker of response in high proliferative ER-positive breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 18, 721–730 (2011).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Flach, S. et al. Liquid BIOpsy for MiNimal RESidual DiSease detection in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (LIONESS). Br. J. Cancer 126, 1186–1195 (2022).

van Dorp, J. et al. High- or low-dose preoperative ipilimumab plus nivolumab in stage III urothelial cancer: the phase 1B NABUCCO trial. Nat. Med. 29, 588–592 (2023).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Tarasov, A., Vilella, A. J., Cuppen, E., Nijman, I. J. & Prins, P. Sambamba: fast processing of NGS alignment formats. Bioinformatics 31, 2032–2034 (2015).

Pedersen, B. S. & Quinlan, A. R. Mosdepth: quick coverage calculation for genomes and exomes. Bioinformatics 34, 867–868 (2018).

Shen, R. & Seshan, V. E. FACETS: allele-specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e131 (2016).

Tate, J. G. et al. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D941–D947 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Manta: rapid detection of structural variants and indels for germline and cancer sequencing applications. Bioinformatics 32, 1220–1222 (2016).

Wang, K., Li, M. & Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from next-generation sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164 (2010).

Mayakonda, A., Lin, D. C., Assenov, Y., Plass, C. & Koeffler, H. P. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28, 1747–1756 (2018).

Sauerbrei, W., Taube, S. E., McShane, L. M., Cavenagh, M. M. & Altman, D. G. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): an abridged explanation and elaboration. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110, 803–811 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an educational grant from Pfizer and Neogenomics, and a grant from L’association Jules Bordet no 2021-08. M.I. was the recipient of all the above grants. Pfizer and Neogenomics had no role in study design, data collection and analysis or manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Alexandra Stanciu, Michail Ignatiadis. Resources, supervision, and funding acquisition: Michail Ignatiadis. Data curation: Alexandra Stanciu, Elisa Agostinetto, Christodoulos Pipinikas, Amber Chevalier, Nathan Campbell. Software and Project Administration: Alexandra Stanciu. Formal analysis: Alexandra Stanciu, Christodoulos Pipinikas, Amber Chevalier, Nathan Campbell. Writing—original draft: Alexandra Stanciu, Elisa Agostinetto, Michail Ignatiadis. Validation, investigation, visualization, and writing—review & editing: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Alexandra Stanciu: The author declares no potential conflicts of interest. Elisa Agostinetto: advisory board or honoraria from Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Abscint, Bayer; research grant to my Institution from Gilead; meeting/travel grants from Novartis, Roche, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Abscint, Menarini (all outside the submitted work). Mariana Brandão: Advisory board for Janssen, Sanofi, Pierre-Fabre, Daichii, Pfizer and Amgen. Speaker fee from AstraZeneca, BMS, Janssen, Takeda, MSD, Pfizer. Is/was an investigator for AstraZeneca, Boeringher, Merus, Merck, Roche/GNE, Sanofi, iTeos, Pierre-Fabre. Travel grant from Takeda, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Roche, Merus. Consultancy for AstraZeneca and Boeringher. Organizations: EORTC LCG, ESMO committees. Andreas Papagiannis and Christodoulos Pipinikas: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest Lieveke Ameye: The author declares no potential conflicts of interest. Marianne Paesmans: The author declares no potential conflicts of interest. Tatiana Besse: The author declares no potential conflicts of interest. Francoise Rothe: The author declare no potential conflicts of interest, Laurence Buisseret: Salary partly covered by the Fondation contre le Cancer (Belgium), Research funding to my Institution from AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Advisory role for Domain Therapeutics, iTeos Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Member of the IMMUcan Consortium (EORTC), Travel grants from GILEAD, AstraZeneca, Roche, LilyDonatienne Taylor and Patrick Neven and Christos Sotiriou: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest, Francois P Duhoux: reports consultancy and advisory role fees to institution from Amgen, AstraZeneca, DaiichiSankyo, Gilead Sciences, Lilly, Menarini, MSD Oncology, Novartis, Pierre-Fabre, Pfizer, Roche, Seattle Genetics; travel support for attending medical conferences from Amgen, DaiichiSankyo/AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, and Teva.Peter Vuylsteke: The author declare no potential conflicts of interes., Michail Ignatiadis consultancy roles for Seattle Genetics, Daichi, AstraZeneca, Menarini/Stemline, Gilead Sciences, Rejuveron Senescence Therapeutics, and Novartis, grant/research support (to institution) from Pfizer, Roche, Inivata Inc, and Natera Inc, and uncompensated roles for EORTC (EORTC Board of Directors 2018–2021, Chair EORTC Breast Cancer Group 2021–2024).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stanciu, A., Agostinetto, E., Papagiannis, A. et al. Personalized ctDNA detection and genomic profiling in the NeoRHEA Study. npj Breast Cancer 11, 137 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00852-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00852-6