Abstract

Monocyte derived macrophages (MDMs) comprise a major cellular fraction of the brain metastatic breast cancer (BMBC) tumor microenvironment (TME), however, their role in BMBC growth and response to therapeutics remains elusive. We developed heterotypic three-dimensional (3D) co-culture spheroid platform of triple negative BMBC cell line MDA-MB-231Br or BMBC patient xenograft derived cell line F2-7 and THP1 monocytes and assessed the impact of monocytes/MDMs on BMBC proliferation, immune modulation, and response to paclitaxel. BMBC cell and monocyte interactions enhanced BMBC cell proliferation and upregulated markers pertaining to M2 macrophage, immune suppression and evasion. Additionally, F2-7 and monocyte co-culture upregulated M1 macrophage and both pro- and anti-inflammatory markers. Co-culture spheroids exhibited higher resistance to paclitaxel as compared to monoculture BMBC spheroids. Our 3D co-culture platform successfully recapitulated to an extent the pro-tumorigenic, immunosuppressive, therapy resistant TME, and tumor immune heterogeneity of BMBC and could contribute towards understanding tumor immune interactions in BMBC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brain metastatic breast cancer (BMBC) occurs in ~24% of breast cancer patients and eventually proves fatal within few months of diagnosis1. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) positive and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) bears the highest propensity to metastasize to the brain, with highly aggressive TNBC accounting for early fatality2. The unavailability of any effective means to control metastases apart from local surgery and radiotherapy contributes to the poor prognosis of BMBC patients3. Of the many reasons, the lack of understanding of the tumor microenvironmental niche of brain metastases has been a major hurdle in developing effective therapeutic measures against BMBC.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex cellular ecosystem of strategically located plethora of cell types including tumor cells and other stromal cells such as immune cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts4. Amongst these cell types, innate immune cells that are mostly of myeloid origin including monocytes and macrophages have been shown to comprise the major fraction of the non-tumor cells in the TME5. Importantly, these innate immune cells have been reported to play a crucial role in promoting growth and survival of cancer cells and reshaping the TME6. This is particularly true for primary breast cancer and its extracranial metastases. However, the cellular diversity of intracranial metastases arising from breast, lung, skin and other forms of cancer have only been elucidated to a limited extent. A recent study at single cell resolution by Karimi et al., has shown that intracranial metastases are largely populated by resident microglial cells and blood derived macrophages7. Similarly, Griguolo et al., Friebel et al., and others have also reported the presence of blood-derived macrophages and comprising thereof, a significant fraction of cellular population of brain metastases8,9. As opposed to earlier notion that brain microenvironments are immune privileged, these recent studies have unequivocally demonstrated that brain metastases are immune rich and prone to immune modulation.

Significant advances in solid tumor studies have led to the appreciation of the profound impact TME has on disease progression and treatments10. Despite the cognizance of the pivotal role that the innate immune cells have on the TME, the fundamentals of the inter cellular crosstalk in the TME are only beginning to be unraveled. Especially, the TME of brain metastases remains largely unexplored and poorly understood, in part, due to limited access to samples of brain metastases and lack of model systems to study these crucial interactions. To address this need, in this work, we developed a three-dimensional (3D) co-culture spheroid platform comprising of triple negative BMBC cells (including BMBC patient xenograft derived cells) and THP1 monocytes/macrophages. Using this platform, we have recapitulated to an extent the pro-tumorigenic and immune suppressive microenvironment of BMBC. We have shown through patient xenograft derived BMBC and monocyte/macrophage co-culture spheroids that BMBC cell-monocyte interaction in the TME leads to polarization of these immune cells to both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory phenotypes. We further show that these polarized macrophages can alter the response of BMBC cells towards therapeutic challenges. Our 3D co-culture spheroid platform, to an extent, has recapitulated the close contact interaction of these cell types occurring in the TME of BMBC leading to pro-tumorigenic, immunosuppressive and therapy resistant microenvironments in vitro.

Results

Multicellular co-culture spheroids of triple negative BMBC cells and monocytes recapitulate pro-tumorigenic microenvironments

BMBC cells and monocytes were mixed at a 1:1 ratio to prepare multicellular co-culture spheroids and assess the morphological variations induced by the presence of tumor cells and innate immune cells in close contact with each other in a 3D environment. Multicellular MDA-MB-231Br monoculture spheroids depicted typical spherical morphology (Fig. 1A). However, multicellular co-culture spheroids of MDA-MB-231Br cells and monocytes appeared distinct with significantly higher numbers of protrusions radiating out of the spheroid. (Fig. 1A, B). We found that the protrusions were mostly comprised of BMBC cells as evidenced by the presence of red fluorescence in the protrusive structures (Fig. 1A). Longitudinal tracking of the spheroid area revealed a significant increase in the cross-sectional area of both monoculture and co-culture spheroids with time (Fig. 1A,C). However, fold change analysis of increase in cross sectional area of respective spheroids from day 1 to day 5 revealed a significantly higher fold change (~ 1.9-fold) in case of co-culture spheroids (Fig. 1C). To assess whether such interaction of monocyte and cancer cells were specific to brain tropic MDA-MB-231Br cells, we developed co-culture spheroids of monocytes and parental MDA-MB-231 cells. Interestingly, we found that the protrusive structures of parental MDA-MB-231 co-culture spheroids were morphologically different and significantly higher in number than the protrusions of brain tropic MDA-MB-231Br co-culture spheroids (Supplementary Fig. 1). Moreover, the parental MDA-MB-231 co-culture spheroids maintained distinct spread-out morphology with numerous spiny protrusions as compared to MDA-MB-231Br co-culture spheroids post 5 days of incubation. These data suggest that parental and brain tropic MDA-MB-231Br cells may interact differentially with monocytes. Increased numbers of protrusive structures and overall spread-out morphology of spheroids with spiney edges indicate that, possibly, interaction of parental cells with monocytes imparts more migratory and invasive capabilities potentiating their metastatic properties, while interactions of brain tropic MDA-MB-231Br and monocytes suggest an induction of overall proliferative advantage. These differential interactions may help the parental cancer cells to migrate and metastasize to distant tissues while at the metastatic sites similar interactions may assist the brain tropic cancer cells to proliferate and colonize the niche.

A tdTomato expressing MDA-MB-231Br BMBC cells and THP1 monocytes were co-cultured (at 1:1 ratio) for indicated days and images were captured on a confocal microscope. B Quantification of number of protrusions. C Quantification of spheroid cross-sectional area. D GFP-Luc expressing F2-7 patient xenograft derived BMBC cells and THP1 monocytes were co-cultured (at 1:1 ratio) for indicated days and images were captured on a confocal microscope. E Quantification of spheroid cross-sectional area. F MDA-MB-231Br cells co-cultured with monocytes exhibit higher levels of proliferative marker (EdU). G Quantification of EdU positive MDA-MB-231Br cells. H F2-7 cells co-cultured with monocytes exhibit higher levels of proliferative marker (Ki67). I Quantification of Ki67 positive F2-7 cells. N = 10 replicates. Data represents mean ± SD. Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. *p < 0.05, ****p < .0001. Scale bar = 200 μm panels (A) and (D); 100 µm panels (F) and (H).

Similarly, we assessed the morphological variation and cross-sectional area of co-culture spheroids of BMBC patient xenograft derived F2-7 and monocytes. Multicellular monoculture spheroids of slow growing F2-7 cells exhibited spherical morphology and an increase in cross sectional area with time, albeit at longer interval as compared to MDA-MB-231Br monoculture multicellular spheroids (Fig. 1D). Both monoculture and co-culture spheroids of F2-7 cells experienced growth with a positive fold change in spheroid cross sectional area. However, the co-culture spheroids showed a significantly higher fold increase (~1.5-fold) compared to monoculture spheroids (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, we observed a distinct accumulation of monocytes circumscribing the central core spheroid of F2-7 cells (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. 2). Extended incubation showed emergence of smaller micro spheroids of F2-7 cells in the presence of monocytes (Fig. 1D).

Tumor associated innate immune cells in primary breast cancers have been shown to promote proliferation of cancer cells leading to enhanced growth and survival of cancer cells in the TME11. Since we observed higher fold change in the cross-sectional area of co-culture spheroids, we measured the percentage of proliferative BMBC cells. In the co-culture spheroids of fast-growing MDA-MB-231Br and monocytes the percentage of proliferation marker (EdU) positive BMBC cells were significantly higher (~29%) as compared to BMBC cell spheroid cultured alone (~20%) (Fig. 1F, G). Interestingly, we also observed similar results in patient xenograft derived F2-7 and monocyte co-culture spheroids. The percentage of proliferation marker (Ki67) positive BMBC F2-7 cells were significantly higher (~40%) in co-culture spheroids as compared to F2-7 cells only spheroids (~27%) (Fig. 1H, I) (Note: We were not able to use EdU for F2-7 cells since they were GFP positive). These findings demonstrate that monocytes in the BMBC TME promote pro-tumorigenic functions.

Activation of mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway following BMBC and monocyte interaction in co-culture spheroids

EMT and MAPK pathways regulate major pro-survival and proliferative processes in the cellular environment12,13. In our multicellular co-culture spheroids of BMBC cells and monocytes, BMBC cells exhibited significantly higher levels of proliferation prompting us to investigate whether key players of MAPK and EMT pathway are modulated via this interaction. We found that levels of phosphorylated Erk1/2 increased significantly in MDA-MB-231Br BMBC cells under co-culture conditions with monocytes (Fig. 2A, B) (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). Similarly, phosphorylated Erk1/2 levels were significantly higher in F2-7 cells under co-culture conditions with monocytes (Fig. 2C, D) (Supplementary Fig. 3C, D). The formation of protrusive structures in MDA-MB-231Br and monocyte co-culture spheroids also suggested enhanced migration of these BMBC cells. To assess the involvement of EMT pathway in monocyte induced migration of BMBC cells, we tested levels of Vimentin, a key player of EMT, in MDA-MB-231Br and monocyte co-culture spheroids. We observed that the intensity of vimentin staining per cell was significantly higher in MDA-MB-231Br cells co-cultured with monocytes (Fig. 2E, F). Additionally, we found that the transcript level of Vimentin was significantly upregulated under co-culture conditions (Fig. 2G). These findings suggest that the co-culture of BMBC cells with monocytes in their microenvironment activates MAPK and EMT pathways in the BMBC cells, thus, imparting a pro-survival and proliferative advantage.

p-Erk 1/2 levels were significantly higher in A, B MDA-MB-231Br or C, D F2-7 cells co-cultured with monocytes as 3D spheroids. E, F Vimentin levels in MDA-MB-231Br and monocyte co-culture spheroids. G Transcript level of Vimentin was significantly upregulated in MDA-MB-231Br and monocyte co-culture conditions. N = 10 replicates, Data represents mean ± SD. Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.001. Scale bar 100 µm.

We further assessed the involvement of redox balance in monocyte induced phenotypic changes in MDA-MB-231Br cells. ROS neutralization by NAC pretreatment completely abolished the formation of distinct protrusive structures in co-culture spheroids. Moreover, NAC pretreatment of BMBC cells prior to incubation with monocytes specifically led to complete abolishment of protrusive structure formation (Supplementary Fig. 4A, B). These data indicate that monocyte interaction with BMBC cells in co-culture spheroids induces ROS modulation in BMBC cells leading to phenotypic changes. Since F2-7 and monocyte co-culture spheroids did not exhibit protrusive structures similar to MDA-MB-231Br and monocyte co-culture spheroids, EMT marker Vimentin and redox balance in F2-7 and monocyte co-culture spheroids were not assessed. Our 3D co-culture spheroid platform demonstrates that innate immune cells in the TME milieu of BMBC cells modulates major proliferative and pro-survival pathways in conjunction with redox homeostasis akin to tumor associated innate immune cells at primary tumor sites5.

Presence of varying levels of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophage markers in BMBC cells and monocyte co-culture spheroids

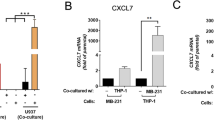

Cancer cells in their milieu have been known to attract innate immune cells and differentiate them to pro-tumorigenic and immunosuppressive phenotype14. We quantitatively analyzed the transcript levels of CCL5, a major chemoattractant that helps in the recruitment of immune cells to tumor niche. We found that CCL5 is significantly upregulated in MDAMB-231Br (~9.4 fold) or F2-7 (~14.9 fold) and monocytes co-culture spheroids suggesting that close physical encounter of BMBC cells and monocytes further promotes the recruitment of immune cells to the TME via CCL5 axis (Figs. 3A and 4A). Further analysis revealed that alternatively activated macrophage M2 markers CD163, CD206 and cMyc were significantly elevated in co-culture of MDA-MB-231Br cells and monocytes with fold changes of ~2.4, ~6.7, and ~1.8 respectively (Fig. 3A), while typical M1 macrophage markers HLA-DRA and CD80 showed no significant changes (Fig. 3B). Tumor-immune cell interactions in their milieu renders the TME highly immunosuppressive facilitating immune evasion, tumor growth and resistance to immunotherapeutic challenges15. We found that transcript levels of immune evasive markers CD24 and CD47 and immune suppressive markers PD1and PDL1 were significantly upregulated in MDA-MB-231Br and monocyte co-culture spheroids with fold changes of ~2, ~1.3, ~1.2, and ~1.2 respectively indicating the existence of an immune suppressive environment (Fig. 3C).

A M2 macrophage markers CD163, CD206, and cMyc, were significantly upregulated in co-culture conditions. B M1 macrophage markers HLA-DRA, CD80 and IL6 showed no significant change. C Immune evasive markers CD24 and CD47 as well as immune suppressive markers PD1 and PDL1 were significantly upregulated under co-culture conditions. N = 10 replicates. Data represents mean ± SD. Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

We then tested BMBC patient xenograft derived F2-7 cells and monocyte co-culture spheroids to assess the polarization status of macrophages and the existence of an immune suppressive environment. Similar to MDA-MB-231Br and monocyte co-culture, we found significant upregulation of alternatively activated M2 macrophage markers in patient xenograft derived F2-7 cells and monocyte co-culture spheroids (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, in addition, we observed significant upregulation of M1 macrophage markers in patient xenograft derived F2-7 cells and monocyte co-culture spheroids (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, both M1 and M2 macrophage derived cytokines, IL6 and IL10 were significantly higher with fold changes of ~1.4 and ~1.5 respectively, in F2-7 and monocyte co-culture spheroids (Fig. 4A, B). We also observed the presence of M1 like elongated macrophages in F2-7 and monocytes/macrophage co-cultures (Supplementary Figs. 5, 6). The immune evasive markers CD24, CD47 and immune suppressive makers PD1 and PDL1 were significantly higher in F2-7 and monocyte co-culture conditions (Fig. 4C). In particular, CD24, CD47, PD1 and PDL1 showed ~1.4-, ~3.0-, ~2.4- and ~22.8-folds higher expression respectively in co-culture spheroids versus controls. We observed that the magnitude of significantly upregulated markers in F2-7 and monocytes co-culture spheroids were higher than the ones that were upregulated in MDA-MB-231Br and monocytes co-culture spheroids. Particularly, CD163 (17.3-fold vs. 2.4-fold), cMyc (5.4-fold vs. 1.8-fold), CSF1 (7.3-fold vs. 2.0-fold) and PDL1 (22.8-fold vs. 1.2-fold) in co-culture spheroids of F2-7 and monocytes showed substantially higher magnitude (Supplementary Fig. 7).

A M2 macrophage markers CD163, CD206, IL10, and cMyc were significantly upregulated in co-culture conditions. B M1 macrophage markers HLA-DRA, CD80 and IL6 were also significantly upregulated in co-culture conditions. C Immune evasive markers CD24 and CD47 as well as immune suppressive markers PD1 and PDL1 were significantly upregulated under co-culture conditions. N = 10 replicates. Data represents mean ± SD. Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.00, ****p < 0.0001.

The differential expression of CSF1 and CSF2 in co-culture spheroids of MDA-MB-231Br/F2-7 cells with monocytes may be associated with M2 type polarization in both conditions while M1 type polarization is only observed in F2-7 co-culture spheroids. Particularly, in MDA-MB-231Br co-cultures, we observed significant upregulation of only CSF1, suggesting that the monocytes in the TME are inclined to polarize towards anti-inflammatory M2 like phenotype expressing key markers such as CD206, CD163 and IL10. On the other hand, in F2-7 and monocyte co-culture, significant and robust upregulation of both CSF1 and CSF2 was observed indicating that the co-cultured monocytes in the F2-7 TME may polarize towards anti and/or proinflammatory phenotype. Presence of crucial markers associated with either of the phenotypes and both proinflammatory cytokine IL6 and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 in the F2-7 TME also further corroborates the presence of both anti and pro inflammatory polarized macrophages. Overall, our 3D spheroid platform partially captures the heterogeneity in the extent of polarization of monocytes into pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophages by different BMBC cell types.

To assess the functional implication of monocyte polarization by BMBC cells, we performed phagocytosis assay using blue fluorescent latex beads. We found that immune cells co-cultured with MDA-MB-231Br showed higher phagocytic activity as compared to monocytes cultured alone (Supplementary Fig. 8A, B). Similarly, we assessed phagocytosis by immune cells co-cultured with F2-7 cells and found that co-cultured immune cells exhibited significantly higher levels of phagocytosis as compared to monocytes cultured alone (Supplementary Fig. 8C, D). These data suggest that the phagocytic activity of monocytic immune cells increases under co-culture conditions with BMBC cells corroborating further that BMBC cells induced monocyte differentiation. We also tested the phagocytic activity of PMA induced THP1 derived macrophages and found substantially higher phagocytic activity (Supplementary Fig. 9) compared to those co-cultured with tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. 8), possibly due to PMA being a strong inducer of monocyte differentiation. We further assessed the prevalence of these key immune markers in the BMBC microenvironment as reported in prior literature in murine models or patient samples. Several markers including CCL5, CD163, MHCII (HLA-DRA), and immune suppression related molecules were reported to be upregulated in the BMBC microenvironment (Supplementary Table 3). This data further suggests that our BMBC and innate immune cell co culture spheroids recapitulate certain features of the tumor immune microenvironment of BMBC.

Co-culture spheroids of BMBC and in vitro polarized pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophages exhibit distinct proliferative and morphological traits

Our results showed increased expression of anti-inflammatory (M2 type) macrophage markers in MDA-MB-231Br and monocyte co-culture spheroids. Moreover, both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory (M1 and M2 type) macrophage markers were upregulated in our F2-7 and monocyte co-culture spheroids. Therefore, increased expression of polarized macrophage markers in BMBC and monocytes co-culture system suggested that close contact interaction between these two types of cells led to differentiation of precursor monocytes into effector macrophages. This finding prompted us to assess the impact of direct interaction of macrophages and BMBC cells as 3D multicellular co-culture spheroids. We created co-culture spheroids of BMBC cells and independently polarized macrophages. Morphological analysis of MDA-MB-231Br and macrophage co-culture spheroids revealed that morphology of M0 culture spheroids appeared similar to monocyte co-culture spheroids with outward radiating protrusive structures (Fig. 5A). MDA-MB-231Br and M1 or M2 co-culture spheroids did not exhibit such distinctive protrusions (Fig. 5A). However, similar to MDA-MB-231Br and M0 co-culture spheroids, M2 co-culture spheroids also showed a significant increase in cross sectional area (~1.9 fold) post incubation further confirming that macrophages in tumor milieu promote tumor growth (Fig. 5B). A similar morphological assessment of F2-7 BMBC cell and macrophage co-culture spheroids was performed. We found that M0 and M2 macrophages circumscribed the central BMBC core spheroid to form distinct BMBC and macrophage co-culture spheroids (Fig. 5C). On the other hand, M1 macrophages and F2-7 BMBC cell spheroids showed only a subtle change in morphology (Fig. 5C). Nevertheless, F2-7 and M0 or M2 macrophage co-culture spheroids showed significantly higher fold change (~2.4 fold and ~2.6 fold respectively) in cross sectional areas as compared to monoculture spheroids (Fig. 5D). These data indicate that innate immune cells (i.e., monocyte-derived macrophages) in the BMBC TME milieu promote tumor growth.

A Representative images of MDA-MB-231Br and macrophage co-culture spheroids. B Quantification of spheroid cross-sectional area from (A). C Representative images of F2-7 and macrophage co-culture spheroids. D Quantification of spheroid cross-sectional area from (C). E MDA-MB-231Br cells isolated from M0 or M2 macrophage co-culture spheroids show higher levels of proliferative marker EdU. F F2-7 cells isolated from M0 or M2 macrophage co-culture spheroids show higher levels of proliferative marker Ki67. G, H Quantitative representation of data from (E) and (F), respectively. Scale bar = 200 μm for (A) and (C). Scale bar = 100 μm for (E) and (F). N = 6 replicates. Data represents mean ± SD. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

The percentage of proliferation marker positive BMBC cells in these co-culture spheroids was assessed to further confirm the pro-tumorigenic effect of direct macrophage interaction with BMBC cells (Fig. 5E, F). M0 or M2 macrophage co-cultures resulted in a significantly higher percentage of proliferation marker positive BMBC cells in both cell types as compared to their respective monoculture controls (Fig. 5G, H). In particular, MDA-MB-231Br + M0 co-culture spheroids showed ~28% EdU positive BMBC cells and MDA-MB-231Br + M2 co-culture spheroids showed ~25% EdU positive BMBC cells. Similarly, F2-7 + M0 co-culture spheroids showed ~40% Ki67 positive BMBC cells and F2-7 + M2 co-culture spheroids showed ~39% Ki67 positive BMBC cells. However, no such increase occurred in M1 macrophage and BMBC cell co-culture spheroids (Fig. 5G, H). Cumulatively, these results suggest that non polarized M0 macrophages with potential to be polarized by cancer cells in situ into anti-inflammatory phenotype and M2 macrophages significantly impact the proliferative and morphological attributes of co-culture spheroids.

BMBC cells and macrophage interaction mediates protective effect on BMBC cells against therapeutic challenge

A very limited repertoire of anti-cancer therapeutics is available against TNBC brain metastases which are effective to a certain extent. One such chemotherapeutic agent, a taxane derivative Paclitaxel has been reported to exhibit limited effect against intracranial metastases of breast cancer16. Blood brain barrier poses major obstruction for free movement of such chemotherapeutic agents thus severely limiting the therapeutic benefits. However, even the low amounts of chemotherapeutic agents that manage to cross the blood brain tumor barrier and accumulate in the metastatic sites fails to impart significant anti-cancer activities17. The innate immune cells in the TME, particularly the tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) have been reported to modulate the response of cancer cells to therapeutic challenges in primary breast cancers and their extracranial metastases18. To assess whether TAMs play similar role in case of brain metastases of TNBC, we exposed co-culture spheroids of BMBC cells and macrophages to Paclitaxel and recorded the response. Monoculture spheroids of BMBC cells were first treated with Paclitaxel to determine the concentration resulting in a viability reduction of ~50%, which was found to be ~50 nM (Supplementary Figs. 10–12). We observed a distinct response of BMBC cells to Paclitaxel in presence of differentially polarized macrophages. The viability of MDA-MB-231Br and M0 or M2 macrophage co-culture spheroids treated with paclitaxel were significantly higher than monoculture spheroids of MDA-MB-231Br cells treated with paclitaxel (Fig. 6A). Although the viability of paclitaxel treated co-culture spheroids of MDA-MB-231Br and M1 macrophages was higher than monoculture spheroids of MDA-MB-231Br cells treated with Paclitaxel, it failed to reach a significant level of difference (Fig. 6A). Additionally, we observed that there was a significant reduction in viability of MDA-MB-231Br and M0 or M1 macrophage co-culture spheroids treated with paclitaxel as compared to their respective untreated controls (Fig. 6A). In contrast, MDA-MB-231Br and M2 macrophage co-culture spheroids treated with Paclitaxel showed no significant reduction in viability as compared to its untreated control (Fig. 6A). These findings suggest that M2 macrophages in the microenvironment of fast growing BMBC cells confers significant protective effect on BMBC cells against chemotherapeutic agent paclitaxel.

A MDA-MB-231Br and M2 macrophage co-culture spheroids show significantly higher viability in the presence of Paclitaxel. B F2-7 and macrophage co-culture spheroids showed significantly higher viability in the presence of Paclitaxel. All three types of macrophages imparted similar effect on the response of F2-7 cells against Paclitaxel. N = 6 replicates. Data represents mean ± SD. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

We further assessed the response of patient xenograft derived F2-7 BMBC cells and macrophage co-culture spheroids against Paclitaxel. We found that the viability of F2-7 and M0 or M1 or M2 macrophage co-culture spheroids treated with paclitaxel was significantly higher than the viability of monoculture spheroids of F2-7 treated with paclitaxel (Fig. 6B). Strikingly, all three types of macrophages including the M1 type macrophages were involved in reducing the inhibitory effects of paclitaxel against F2-7 cells in co-culture conditions (Fig. 6B). Additionally, we found that the viability of co-culture spheroids of F2-7 and M2 type macrophages treated with Paclitaxel showed no significant reduction in viability as compared to untreated control (Fig. 6B).

To specifically ascertain the impact of paclitaxel on BMBC cells under co-culture conditions our next approach was to determine the proliferative fraction of BMBC cells post therapeutic challenge. Paclitaxel is a very potent cytostatic chemotherapeutic drug, and it induces mitotic arrest in actively growing cancer cells19. Using proliferation marker Ki67, we found that the percentage of proliferative BMBC cells in BMBC cells and M0 or M2 macrophages co-culture spheroids were significantly higher than BMBC cells in monoculture spheroids (Fig. 7). Moreover, significantly higher levels of Ki67 positive BMBC cells were present in co-culture spheroids of BMBC cells and M0 or M2 macrophages post therapeutic challenge as compared to monoculture spheroid of respective BMBC cells treated with paclitaxel (Fig. 7B, D). Post paclitaxel treatment, MDA-MB-231Br+M0 co-culture spheroids showed ~33% Ki67 positive cells and MDA-MB-231Br+M2 co-culture spheroids showed ~35% Ki67 positive cells. Similarly, post paclitaxel treatment, F2-7+M0 co-culture spheroids showed ~41% Ki67 positive cells and F2-7+M2 co-culture spheroids showed ~42% Ki67 positive cells (Fig. 7). However, we observed certain differences in proliferative cellular fraction between these cell types with respect to paclitaxel treatment in the presence of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages. No increase in proliferative MDA-MB-231Br BMBC cells was observed under M1 macrophage co-culture conditions post paclitaxel treatment compared to monoculture spheroids of MDA-MB-231Br treated with paclitaxel (Fig. 7B). Contrastingly, higher levels of Ki67 positive F2-7 BMBC cells (~32%) were observed in F2-7 and M1 macrophages co-culture spheroids post therapeutic challenge in comparison to monoculture spheroids of F2-7 cells treated with paclitaxel (Fig. 7D). These results were in line with the cell viability data where we observed significantly higher cellular viability in F2-7 and M1 macrophage co-culture spheroids post paclitaxel treatment. Collectively, our 3D co-culture spheroid platform provides evidence that innate immune cells in the microenvironmental niche of BMBC impart protective effect on BMBC cells from chemotherapeutic challenges.

A Representative images showing Ki67 positivity in Paclitaxel treated MDA-MB-231Br and macrophage co-culture spheroids. B Quantification of Ki67 positive MDA-MB-231Br cells. C Representative images showing Ki67 positivity in Paclitaxel treated F2-7 and macrophage co-culture spheroids. D Quantification of Ki67 positive F2-7 cells. N = 6 replicates. Data represents mean ± SD. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

The TME provides crucial support to the tumor cells for their growth and survival20. Consequently, tumor cells actively regulate and modulate the functions of tumor microenvironmental factors including the cellular counterparts towards protumor phenotype21. The multi-directional cross talk between cancer cells, innate immune cells, other stromal cells and the acellular components of the TME encompasses a diverse range of molecular communication, which is only beginning to be understood. The innate immune cells, which form the major fraction of the cellular component of the TME has been attributed to several tumor supportive functions including growth, survival, evasion, invasion, metastases and resistance to therapies22. The basic understanding of this complex crosstalk ongoing in the TME comes from studies pertaining to primary breast tumors and their extracranial metastases. Furthermore, co-culture systems of primary breast cancer cells and other stromal cells including immune cells, endothelial cells and fibroblast cells have significantly contributed towards understanding the intricacies of TME of primary breast cancer23,24,25. However, so far, the TME of the intracranial metastases including BMBC remains poorly understood. Nevertheless, recent single cell multi-omics studies have elucidated that intracranial metastases are heavily populated with innate immune cells including brain resident microglia and blood monocyte derived macrophages26,27,28. These studies highlighting the compositional dominance of resident and blood derived innate immune cells in the intracranial metastases prompts a very crucial question pertaining to the roles that these cells play in the BMBC TME.

To investigate such pivotal questions, we developed a 3D BMBC cell and innate immune cell co-culture spheroid platform. We used pre-established triple negative BMBC cell line MDA-MB-231Br and triple negative BMBC patient xenograft derived F2-7 in a 3D co-culture system with monocytic cell line THP1 for this purpose. Our findings show that monocytes and BMBC interaction confers a proliferative advantage to BMBC cells. The pro-tumorigenic role of TAMs which are of innate origin have been well established in the TME of primary breast cancers and their extracranial metastases29. TAMs have been known to promote EMT and activate MAPK pathways in tumor cells30,31,32. Additionally, ROS in the TME have been linked to pro survival and metastatic outcomes33,34. A recent study reported that macrophages mediated enhanced viability and metastatic ability of TNBC cells35. These changes were mediated by tumor cell specific elevation of ROS and activation of ERK1/2-ZEB1-VIM pathway via IL1α upregulation. Reportedly, they found that IL1α positively correlated with higher macrophage infiltrations and shorter survival of breast cancer patients35. Another study showed the modulation of migratory potential of triple negative as well as ER+ breast cancer cells via Erk and ROS cross regulation36. Furthermore, immune cell mediated transfer of mitochondria to TNBC cells have been reported to increase ROS and activate Erk leading to enhanced cancer cell proliferation37. Our 3D co-culture spheroids composed of BMBC cell and monocytes show the modulation of EMT and MAPK pathway via immune cell and BMBC cell interaction. Furthermore, immune cell mediated modulation of ROS in the BMBC cells is also evident in our co-culture system. These findings suggest our co-culture system recapitulates some facets of the intricate crosstalk ongoing between BMBC cells and innate immune cells via known mediators of cell survival and proliferation.

Recent reports on brain metastatic niche have promulgated these sites to be highly immune suppressive38. In our co-culture system, we observed significant upregulation of markers pertaining to alternatively activated macrophages along with immune evasion and suppression. Additionally, in co-cultures of patient xenograft derived BMBC cells and monocytes we observed upregulation of markers of classically activated macrophages. As reported earlier by other studies39,40,41, findings from our in vitro 3D co-culture platform suggest the existence of immune evasive and suppressive environment in the BMBC niche. Particularly, we have shown that some of the immune related markers prevalent in the BMBC TME of patients and mouse models were expressed in our multicellular 3D spheroid co-culture platform. Such findings suggest that our in vitro 3D co-culture platform reflects few aspects of the tumor and innate immune cell interactions. Therefore, our BMBC and innate immune cell multicellular 3D co-culture platform would find relevance in complementing in vivo studies pertaining to BMBC.

In the largely immunosuppressive BMBC niche there exist heterogeneity in cellular population and extent of macrophage polarization. For instance, an earlier study reported that in breast cancer metastases, immune infiltration is lower but they harbor higher levels of M2 type macrophages in their TME as compared to their primary tumor42. However, another group reported lower infiltration of M2 type macrophages but higher infiltration of plasma cells43. Variations in macrophage polarization depending on the metastatic site of intracranial breast cancer has been reported previously44. In the BMBC microenvironment, the presence of both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory phenotypes of macrophages suggests existence of continuum of macrophage polarization status. The dichotomic macrophage polarization status prevalent in the BMBC microenvironment is corroborated to a limited extent in our BMBC patient xenograft derived F2-7 BMBC cells and innate immune cells co-culture system. Essentially, our 3D co-culture platform partially captured the heterogeneity in macrophage polarization depending upon the BMBC cells used. We acknowledge that this represents only a very small fraction of the cellular heterogeneity of BMBC TME.

It remains extremely difficult to treat brain metastatic diseases, with radiotherapy and surgery being the primary modes of treatment. The non-responsiveness of brain metastases to chemotherapeutic, targeted or immunotherapeutic challenges have been largely attributed to restrictions posed by intact blood brain barrier (BBB)45. However, disruption of BBB by tumor metastases and their neovascularization allows therapeutic molecules to reach the brain metastases, albeit at variable concentrations17. Moreover, it has been reported that therapeutic agents accumulating in the brain metastases fail to discharge antitumor activities suggesting that the TME of brain metastases could be responsible for such outcomes17. The innate immune component, TAMs, have been known to modulate the response of cancer cells to therapeutic challenges46. Possibly, innate immune cells in the BMBC TME also play similar role in imparting therapy resistance to BMBC cells. In line with this, in our co-culture spheroid platform of BMBC cells and macrophages, the close contact interaction of immune cells and BMBC cells led to significant rescue of BMBC cells from antitumor effect of chemotherapeutic agent Paclitaxel. Such an effect was especially more profound in the co-culture system where M2 type macrophages were used. Our co-culture spheroid platform demonstrates that macrophages in the TME of the BMBC play a crucial role in instigating protection to BMBC cells from systemic chemotherapeutic measures.

Unlike HR/HER2 positive BMBC, the lack of specific therapeutic targets against triple negative BMBC leaves very limited treatment options with systemic chemotherapy as one of the medical interventions17. Various nanoparticles, liposomes and peptide derivates of taxanes are under development for intracranial targeting of BMBC which may show better efficacy against triple negative BMBC47,48,49. Nevertheless, apart from the mode of delivery of paclitaxel in various formulations including either albumin bound, liposome encapsulated, or peptide bound the fundamental mechanism of action targeting the microtubules function and disrupting the cell cycle remains the same. Therefore, it remains imperative to understand the role of triple negative BMBC TME including the immune cells in modulating the therapeutic response to chemotherapeutic agent paclitaxel. Our approach to use paclitaxel as the choice of chemotherapeutic agent will help towards understanding this modulation of response to taxane derivatives by BMBC TME. Nonetheless, for our future studies we will be using better brain penetrant derivatives of chemotherapeutic agents including taxane in combination with other immunotherapeutic agents. These combinations strategies may have better efficacy against the triple negative BMBC.

Our study highlights differences in innate immune cell-mediated modulation of BMBC cell survival, proliferation, and response to therapeutic challenges. Also, variations in the cross regulation of immune cells by two types of triple negative BMBC cells highlight differences in BMBC cell modulated TME prevalent innate immune cells. MDA-MB-231Br BMBC cells polarized monocytes towards mostly anti-inflammatory phenotypes while the BMBC patient xenograft derived F2-7 cells induced polarization towards a mixed type of both pro inflammatory and anti-inflammatory phenotypes. Moreover, therapeutic response of F2-7 BMBC cells against Paclitaxel was modulated by both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophages while only anti-inflammatory macrophages modulated response of MDA-MB-231Br cells further suggesting the prevalence of tumor intrinsic differences that shape the tumor immune interaction and outcomes. The tumor intrinsic differences in growth rate, migratory potential, mesenchymal like phenotype of MDA-MB-231Br and epithelial like phenotype of F2-7 cells, may have influenced the differential polarization of monocytes as well as observed dichotomy in response to paclitaxel in presence of M1 type macrophages. The observed differences in monocyte polarization and therapy response are indicative of inter patient heterogeneity in BMBC TME arising from similar primary breast cancer subtype. While rational designing of therapeutic strategies targeting mostly anti-inflammatory TAMs may be helpful in alleviating TME mediated tumor progression or therapy resistance, further consideration pertaining to contribution of proinflammatory macrophages in the TME milieu is necessary. Further exploration of BMBC TME based on our platform may be helpful in identifying these tumor intrinsic differences leading to identification of biomarkers associated with brain metastases arising from triple negative primary tumor subtype. Additionally, better understanding of the phenotypic and functional variations of the innate immune cells including TAMs prevalent in the BMBC TME would also be possible through our platform. Potentially, our platform could be further adapted to incorporate other major components of the BMBC TME. Through such improvements, our platform can contribute towards better understanding of heterogeneity of the BMBC TME thus potentially contributing to patient stratification based upon the biomarkers and TME variations. Better understanding of BMBC TME heterogeneity will be very helpful in designing therapeutic strategies targeting tumor intrinsic and TME factors best suited for the patient thus increasing the efficiency of treatments while reducing or eliminating untoward outcomes.

In sum, our in vitro 3D co-culture spheroids composed of BMBC cells and monocytes/macrophages successfully captured certain aspects of pro-tumorigenic, immunosuppressive and therapy resistant BMBC TME. In addition, our system is also partially reflective of the pro and anti-inflammatory heterogeneity observed in the BMBC niche. Thus, this system could potentially serve as a platform for studying the BMBC and innate immune cells interactions and delineating the multidirectional crosstalk. Moreover, this system could also be helpful in drug screening applications for developing strategies targeted towards BMBC and innate immune cell interactions in the future. As with any other in vitro platforms, our 3D co-culture system cannot recapitulate the entire complexity of the BMBC TME. Hence, we acknowledge some limitations of the present study: (1) This study is limited by the use of only two triple negative BMBC cells and one monocytic cell line and the impact of other stromal components of BMBC TME is yet to be addressed. (2) The monocytic cell line THP1 is representative of the infiltrating monocyte derived macrophages. Thus, the contribution of other groups of resident macrophages in the TME may not be fully recapitulated. (3) Multiple subtypes of breast cancer, especially the brain tropic HER2 positive BMBC has not been included in this work. (4) The usage of discreet M1 and M2 polarized macrophages may not represent the continuum of macrophage phenotypic state occurring in vivo. Future works incorporating other crucial components of the BMBC TME including astrocytes, microglia, and endothelial cells will significantly expand our understanding of the complex TME and their role in tumor progression. These would be the focus of future studies, wherein this platform could also serve as a foundation for the inclusion of additional cellular and acellular components of the BMBC TME.

Methods

Cell culture

tdTomato expressing triple negative BMBC cell line MDA-MB-231Br was cultured in DMEM as described previously50. Triple negative BMBC patient xenograft derived F2-7 GFP-Luc cell line (provided by Dr. Diana Cittelly, University of Colorado) was cultured in DMEM/F12 with insulin (1 nM). THP1 monocytes were cultured in RPMI 1640. Parental MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM. All media were supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep antibiotic. The cell lines were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified chamber.

Reagents

The list of reagents is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Monocyte differentiation into macrophages and polarization

Monocytes were treated with Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (150 nM) overnight to induce differentiation into macrophages. Spent media was discarded and adherent macrophages were further cultured in fresh media for 24 h. For polarization into M1 phenotype, adherent macrophages were treated with Interferon gamma (IFN-G) (20 ng/ml) and Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 pg/ml) for 72 h. For polarization into M2 phenotype, adherent macrophages were treated with Interleukin 4 (IL-4) (20 ng/ml) for 72 h. Macrophages cultured without added polarizing agents were considered M0 macrophages. Adherent macrophages were harvested by incubating the cells in 10 mM EDTA in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. The macrophages were collected by centrifugation at 350 × g for 5 min and washed once with fresh complete media to remove any remaining EDTA. Finally, the macrophages were suspended in fresh media and used for preparing co-culture spheroids.

Preparation of co-culture spheroids

Multicellular co-culture spheroids were prepared by mixing BMBC cell lines (MDA-MB-231Br or F2-7) and monocytes or macrophages at a 1:1 ratio. Requisite number of cells suspended in 100 µl of fresh media were transferred to Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA) coated 96 well conical bottom plates and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min. 2.5 µl of growth factor reduced Matrigel was added to each well to facilitate spheroid formation and incubated overnight. Next day, individual spheroids were transferred to pHEMA coated 96-well flat bottom plates and incubated further in an incubator for 5–15 days as necessary.

Cell viability and drug treatment

Viability of spheroids was measured by MTS assay. Briefly, BMBC monoculture or macrophage co-culture spheroids were treated at indicated concentrations of Paclitaxel for 72 h. Post treatment, untreated and Paclitaxel treated spheroids were incubated with MTS dye dissolved in media for 4 h in an incubator. Post incubation, the plates with spheroids were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 2 min and 100 µl of supernatant was transferred to a fresh 96 well clear bottom plate. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm in a Molecular Devices spectrophotometer. The percentage viability was calculated using the following formula.

Percent viability = (Abs490nm of treated sample/Abs490nm of control sample) *100.

EdU incorporation assay

Cell proliferation was determined by EdU incorporation assay as described previously51. Briefly, co-culture spheroids of BMBC cells and innate immune cells were incubated with 10 µM EdU overnight. The following day the spheroids were dispersed into a single cell suspension using the cell dissociating agent-Accutase. EdU incorporation in the single cell suspension was detected using EdU cell proliferation kit (Thermo) following manufacturer’s protocol. Images of the cells were recorded on an IX-83 confocal microscope (Olympus) using FITC filter. EdU positive cells were detected as bright green, fluorescent cells while BMBC cells were detected as RFP positive red fluorescent MDA-MB-231Br cells. Dual EdU and RFP positive cells were counted against total RFP positive BMBC cells to calculate percentage EdU positive BMBC cells in the case of MDA-MB-231Br BMBC cells. DAPI was used as a nuclear stain.

Immunocytochemistry and microscopy

Immunocytochemistry of co-culture or monoculture spheroid derived cells were performed as previously52. Briefly, spheroids were harvested, washed once with PBS and incubated with Accutase to dissociate the spheroids into single cell suspension. After dissociation, cells were fixed and permeabilized with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and 0.5% Triton X-100 respectively, followed by blocking with 5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were incubated with primary antibody p-Erk1/2 (p44/p42) (1:200) or Ki67 (1:200) or Vimentin (1:50) overnight at 4 °C. On the next day, cells were washed once with PBS and incubated with fluorophore tagged secondary antibody (1:1000) and DAPI (1:1000) for 45 min at room temperature. The cells were washed to remove unbound antibodies and finally kept submerged in PBS. The images were recorded on an IX-83 confocal microscope using the appropriate filter as necessary. The area of the whole spheroids was measured using ROI function of the cell Sense software to demarcate the outline of the whole spheroid followed by determination of cross-sectional area. The intensity of colored images was measured similarly using ROI function of the cell Sense software to demarcate the outline of the cells and determine mean color intensity value. For quantifying the protrusive structures, number of protrusions per spheroid was counted manually from whole spheroid images.

For visualization of macrophages in co-culture spheroids, macrophages were pre-stained with cell permeant Cell Tracker Green CMFDA or Cell Tracker Red CMTPX dye following manufacturer’s protocol as required.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblot of monoculture and co-culture spheroids were performed following standard protocols. Briefly, mono culture or co-culture spheroids were harvested, washed once with PBS and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors for 1 h at 4 °C. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 rcf for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. The protein concentration of the cell lysate was determined using BCA kit following manufacturers’ instructions. 5 µg of BMBC monoculture cell lysate and 5 µg of monocytes monoculture cell lysate were mixed together for a total of 10 µg cell lysate and was used as mix samples for the immunoblot. 10 µg of cell lysate was resolved in polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the membrane was incubated with primary antibody p-Erk 1/2 (1:2000) or total Erk1/2 (1:2000) or Actin (1:2000) for overnight at 4 °C with gentle rocking. The membrane was washed three times with TBST for 5 min each and then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000) for 1 h at room temperature. Post incubation, the membrane was washed three times with TBST. The membrane was incubated with Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate developing solutions and placed in a BioRad ChemiDoc imager to visualize the bands. The densitometric analysis of the immunoblot bands was performed on ImageJ software, and the values were plotted using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

ROS quenching analysis

MDA-MB-231Br cells or THP1 monocytes were either pre-treated with N-acetyl cysteine (NAC, 10 mM) for 2 h or left untreated. After pretreatment, cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in fresh NAC free complete media. NAC pretreated or untreated MDA-MB-231Br cells and monocytes were mixed in different combinations to prepare co-culture spheroids. The number of protrusive structures per spheroid were counted and plotted to determine the effect of ROS quenching by NAC. ROS levels were detected using DCFDA dye (10 µM). Briefly, NAC pretreated or untreated MDA-MB-231Br cells were incubated with DCFDA dye in serum free media for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation cells were washed with PBS and green fluorescence of DCFDA dye in the cells was visualized on a confocal microscope.

qRT-PCR

Transcriptional status of selective target genes was determined by quantitative real time PCR (primer sequences in Supplementary Table 2). Total RNA from monoculture spheroids of BMBC cells, co-culture spheroids and monocultures of innate immune cells were isolated using GeneJet mini RNA isolation kit. RNA was quantified on a Cytation5 multi spectrophotometer and cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of RNA using cDNA synthesis kit on a BioRad thermal cycler. Equal amount of total RNA from BMBC monoculture spheroids and monocultures of innate immune cells were mixed to synthesize cDNA and eventually to be used as template for mixed control. The fold change in transcript levels was determined by 2-ΔΔCt method by comparing the transcript levels of co-culture spheroids to transcript levels of mixed control.

Phagocytosis assay

Monocytes were cultured alone or as co-culture spheroids with MDA-MB-231Br or F2-7 BMBC cells at 1:1 ratio in a pHEMA coated 96 well plates. Post incubation the contents from each well were transferred to individual wells of a fresh flat bottom 96 well plates (coated with Fibronectin 20 µg/ml to enhance cell adherence) and incubated further in a cell culture incubator for 2 h to allow the immune cells to adhere. 1 µl of blue fluorescent latex beads (2 µm size) were added to each well and incubated further for 2 h under same conditions for the immune cells to phagocytose the beads. Post incubation the unbound beads were washed off with sterile PBS and the plates were imaged on an Olympus IX83 confocal microscope. The blue fluorescent beads overlapping with the immune cells were counted over the total number of immune cells per microscopic field of view and presented as percentage of phagocytotic immune cells. In vitro differentiated macrophages from THP1 monocytes were processed similarly for phagocytosis assay. Briefly, THP1 cells were differentiated with PMA and polarized using specific cytokines as mentioned above. Following polarization, 1 µl of blue fluorescent latex beads (2 µm size) were added and incubated further for 2 h under same conditions for the immune cells to phagocytose the beads. Post incubation the unbound beads were washed off with sterile PBS and the plates were imaged on an Olympus IX83 confocal microscope. The blue fluorescent beads overlapping with the immune cells were counted over the total number of immune cells per microscopic field of view and presented as percentage of phagocytotic immune cells. The data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test was used to compare the means between two samples. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to compare means of multiple samples. P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The results were presented as mean + /- SD. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Data availability

All data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Darlix, A. et al. Impact of breast cancer molecular subtypes on the incidence, kinetics and prognosis of central nervous system metastases in a large multicentre real-life cohort. Br. J. Cancer 121, 991–1000 (2019).

Raghavendra, A. S. & Ibrahim, N. K. Breast cancer brain metastasis: a comprehensive review. JCO Oncol. Pract. 20, 1348–1359 (2024).

Leone, J. P. & Leone, B. A. Breast cancer brain metastases: the last frontier. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 4, 33 (2015).

Baghban, R. et al. Tumor microenvironment complexity and therapeutic implications at a glance. Cell Commun. Sig. 18, 59 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages: an accomplice in solid tumor progression. J. Biomed. Sci. 26, 78 (2019).

Lin, Y., Xu, J. & Lan, H. Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor metastasis: biological roles and clinical therapeutic applications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12, 76 (2019).

Karimi, E. et al. Single-cell spatial immune landscapes of primary and metastatic brain tumours. Nature 614, 555–563 (2023).

Griguolo, G. et al. A comprehensive profiling of the immune microenvironment of breast cancer brain metastases. Neuro Oncol. 24, 2146–2158 (2022).

Friebel, E. et al. Single-cell mapping of human brain cancer reveals tumor-specific instruction of tissue-invading leukocytes. Cell 181, 1626–1642.e20 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Role of tumor microenvironment in cancer progression and therapeutic strategy. Cancer Med. 12, 11149–11165 (2023).

Bied, M. et al. Roles of macrophages in tumor development: a spatiotemporal perspective. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 20, 983–992 (2023).

Huang, Y., Hong, W. & Wei, X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15, 1088205 (2022).

Braicu, C. et al. A comprehensive review on MAPK: a promising therapeutic target in cancer. Cancers 11, 1618 (2019).

Pan, Y. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immunity. Front. Immunol. 11, 583084 (2020).

Labani-Motlagh, A., Ashja-Mahdavi, M. & Loskog, A. The tumor microenvironment: a milieu hindering and obstructing antitumor immune responses. Front. Immunol. 11, 940 (2020).

Shah, N. et al. Investigational chemotherapy and novel pharmacokinetic mechanisms for the treatment of breast cancer brain metastases. Pharmacol. Res. 132, 47–68 (2018).

Bailleux, C., Eberst, L. & Bachelot, T. Treatment strategies for breast cancer brain metastases. Br. J. Cancer 124, 142–155 (2021).

Salemme, V. et al. The role of tumor microenvironment in drug resistance: emerging technologies to unravel breast cancer heterogeneity. Front. Oncol. 13, 1170264 (2023).

Weaver, B. A. How Taxol/paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 2677–2681 (2014).

Anderson, N. M. & Simon, M. C. The tumor microenvironment. Curr. Biol. 30, R921–R925 (2020).

De Visser, K. E. & Joyce, J. A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 41, 374–403 (2023).

Lu, C. et al. The role of innate immune cells in the tumor microenvironment and research progress in anti-tumor therapy. Front. Immunol. 13, 1039260 (2023).

Madsen, N. H. et al. Monocyte Infiltration and Differentiation in 3D Multicellular Spheroid Cancer Models. Pathogens 10, 969 (2021).

Ascheid, D. et al. A vascularized breast cancer spheroid platform for the ranked evaluation of tumor microenvironment-targeted drugs by light sheet fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Commun. 15, 3599 (2024).

Dhandapani, H. et al. In vitro 3D spheroid model preserves tumor microenvironment of hot and cold breast cancer subtypes. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 12, 2300164 (2023).

Smalley, I. et al. Single-cell characterization of the immune microenvironment of melanoma brain and leptomeningeal metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 4109–4125 (2021).

Gonzalez, H. et al. Cellular architecture of human brain metastases. Cell 185, 729–745.e20 (2022).

Schreurs, L. D. et al. The immune landscape in brain metastasis. Neuro Oncol. 27, 50–62 (2024).

Noy, R. & Jeffrey Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity 41, 49–61 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Progress of tumor-associated macrophages in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of tumor. Front. Oncol. 12, 911410 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Interaction with tumor‑associated macrophages promotes PRL‑3‑induced invasion of colorectal cancer cells via MAPK pathway‑induced EMT and NF‑κB signaling‑induced angiogenesis. Oncol. Rep. 41, 2790–2802 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Unveiling the contribution of tumor-associated macrophages in driving epithelial-mesenchymal transition: a review of mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1404687 (2024).

Teng, Y. et al. Targeting reactive oxygen species and fat acid oxidation for the modulation of tumor-associated macrophages: a narrative review. Front. Immunol. 14, 1224443 (2023).

Weinberg, F., Ramnath, N. & Nagrath, D. Reactive oxygen species in the tumor microenvironment: an overview. Cancers 11, 1191 (2019).

Hao, M. et al. The interaction between macrophages and triple-negative breast cancer cells induces ROS-mediated interleukin 1α expression to enhance tumorigenesis and metastasis. Adv. Sci. 10, e2302857 (2023).

Acosta-Casique, A. et al. ERK activation modulates invasiveness and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) production in triple negative breast cancer cell lines. Cell. Signal. 101, 110487 (2023).

Kidwell, C. U. et al. Transferred mitochondria accumulate reactive oxygen species, promoting proliferation. eLife 12, e85494 (2023).

Fares, J. et al. Emerging principles of brain immunology and immune checkpoint blockade in brain metastases. Brain 144, 1046–1066 (2021).

Niesel, K. et al. The immune suppressive microenvironment affects efficacy of radio-immunotherapy in brain metastasis. EMBO Mol. Med. 13, e13412 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. A brain-enriched lncRNA shields cancer cells from immune-mediated killing for metastatic colonization in the brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2200230119 (2022).

Patel, L., Kolundzic, N. & Abedalthagafi, M. Progress in personalized immunotherapy for patients with brain metastasis. npj Precision Oncol. 9, 31 (2025).

Zhu, L. et al. Metastatic breast cancers have reduced immune cell recruitment but harbor increased macrophages relative to their matched primary tumors. J. ImmunoTherapy Cancer 7, 265 (2019).

Lu, W.-C. et al. Genomic landscape of the immune microenvironments of brain metastases in breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 18, 327 (2020).

Rippaus, N. et al. Metastatic site-specific polarization of macrophages in intracranial breast cancer metastases. Oncotarget 7, 41473–41487 (2106).

Chen, Q. et al. Systemic treatments for breast cancer brain metastasis. Front. Oncol. 12, 1086821 (2023).

Xiao, M. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages: critical players in drug resistance of breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 12, 799428 (2021).

Du, J. et al. Multifunctional Liposomes Enable Active Targeting and Twinfilin 1 Silencing to Reverse Paclitaxel Resistance in Brain Metastatic Breast Cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 23396–23409 (2021).

Luo, Z. et al. All-stage targeted therapy for the brain metastasis from triple-negative breast cancer. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 13, 359–371 (2023).

Kumthekar, P. et al. ANG1005, a Brain-Penetrating Peptide–Drug Conjugate, Shows Activity in Patients with Breast Cancer with Leptomeningeal Carcinomatosis and Recurrent Brain Metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 2789–2799 (2020).

Gurung, S. K., Shevde, L. A. & Rao, S. S. Laminin I mediates resistance to lapatinib in HER2-positive brain metastatic breast cancer cells in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 720, 150142 (2024).

Kondapaneni, R. V. et al. Protocol for generating dormant human brain metastatic breast cancer spheroids in vitro. STAR Protoc. 5, 102962 (2024).

Kondapaneni, R. V., Shevde, L. A. & Rao, S. S. A Biomimetic Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Models Mass Dormancy in Brain Metastatic Breast Cancer Spheroids. Adv. Biol. 7, 2200114 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation of Alabama (to S.R.). We thank Dr. Matthew Jenny (Biological Sciences) for the use of the Nanodrop system, Dr. Yonghyun Kim (Chemical and Biological Engineering) for the use of thermal cycler and ChemiDoc imager, and Dr. M.N.V. Ravi Kumar (Translational Science and Medicine) for the use of RT-PCR equipment at the University of Alabama.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. and S.R. conceived and designed all experiments. S.G. and K.B. performed experiments and data collection. S.G. analyzed the data, prepared figures, and wrote the original draft. S.R. provided resources. S.G. and S.R. edited and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gurung, S.K., Berger, K. & Rao, S.S. Cancer cell-monocyte co-culture spheroids recapitulate pro-tumorigenic, immunosuppressive, and drug-resistant microenvironments in brain metastatic breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 11, 136 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00855-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00855-3