Abstract

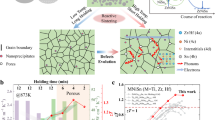

Thermoelectric materials can be potentially applied to waste heat recovery and solid-state cooling because they allow a direct energy conversion between heat and electricity and vice versa. The accelerated materials design based on machine learning has enabled the systematic discovery of promising materials. Herein we proposed a successful strategy to discover and design a series of promising half-Heusler thermoelectric materials through the iterative combination of unsupervised machine learning with the labeled known half-Heusler thermoelectric materials. Subsequently, optimized zT values of ~0.5 at 925 K for p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb0.97Sn0.03 and ~0.3 at 778 K for n-type Sc0.65Y0.3Ti0.05NiSb were experimentally achieved on the same parent ScNiSb.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thermoelectric (TE) conversion technology is able to alleviate global energy and environmental crisis by directly converting heat energy to electricity1,2. Ideal TE materials are then anticipated and pursued, which should possess a high dimensionless figure of merit zT = σS2T/κ, where σ, S, κ, and T are the electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, thermal conductivity, and absolute temperature, respectively, as well as abundant and environmentally friendly constituent elements, good mechanical properties, and thermal stability3,4. Half-Heusler alloys with a general formula XYZ (X and Y are transition metals, Z is the main group element), crystallized in the MgAgAs-type structure5,6,7 (space group: \(F\bar 43{{{\mathrm{m}}}}\)), were selected and extensively investigated as the promising candidates for potential TE applications8,9.

Although there are more than five hundred different half-Heusler compounds in the Materials Project database10 (https://materialsproject.org/), very limited components have been exploited, including the maturely studied n-type (Ti, Zr, Hf)NiSn11,12 and p-type (Ti, Zr, Hf)CoSb13,14, and recently developed (Nb, Ta)CoSn15, (V, Nb, Ta)FeSb16,17, and ZrCoBi18, etc. all of which have obtained state-of-the-art zT values higher than 1. Especially, record-high zT values > ~1.5 were recently achieved for ZrCoBi0.65Sb0.15Sn0.2018 and Ta0.74V0.1Ti0.16FeSb17 due to the converged band structure and reduced lattice thermal conductivity. In that way, we are dedicated to discovering some other prospective half-Heuslers within the database for further investigation.

Currently, Machine learning (ML)19,20 and high throughput calculations21,22 have gradually replaced the traditional trial-and-error approaches with the advantages of high efficiency and low cost. Among them, ML is a powerful tool for the exploration of the desired materials by employing algorithms to construct a statistical model based on the complicated patterns found in high dimensional spaces23,24,25,26, such as guiding the chemical synthesis27, assisting the multi-dimensional characterization28, analyzing the crystal structure29, and regulating the phase transition30 and defects31, etc. Supervised learning32 is the most widespread form of ML in materials science, which needs sufficient amount of relevant data, along with the known target properties and has been applied in the TE materials development and prediction of the Seebeck coefficient33 (S), power factor34 (PF = S2σ), lattice thermal conductivity35 (κL), and zT values36. However, much attention must be paid to obtain beforehand a big training TE database with the expected labels for building a supervised classification or a regression model.

Unsupervised machine learning37,38, which does not require well-labeled training data, can discover hidden patterns in the unlabeled dataset based on the input feature values. It can be utilized for clustering, association, and dimensionality reduction, in which clustering techniques can group the similar data related by different variables into the same clusters and draw a boundary between different clusters, identifying candidates similar to expected examples19. Therefore, it can directly screen the expected TE materials from the Materials Project by linking the descriptors related to the TE domain knowledge. We can regard the compounds that are in the same cluster with the experimentally reported half-Heusler TE materials as potential TE materials. Unsupervised clustering includes three categories, prototype-based clustering, density-based clustering, and hierarchical clustering, each of which contains different algorithms. Some instructive results have been achieved in materials science, e.g., discoveringfast Li-conductors with conductivities of 10−4–10−1 S cm−139,.

In this work, we focused on developing advanced half-Heusler TE materials by combing an iterative unsupervised machine learning based on four types of characteristics describing TE performance. A series of potential half-Heuslers were discovered, including ANiZ (A = Y, Lu, Er, Sc, Tb, Tm, Ho, Dy, Pr, Sm, Z = Sb, Bi), MFeTe (M = Zr, Ti), and NCoTe (N = Sc). Although stoichiometric ANiZ (A = Y, Lu, Er, Sc, Tm, Ho, Dy, Z = Sb) has ever been repoted as TE materials40,41,42, no further attention was paid due to the very low zTs for them. We herein placed these alloys into the test set and revisited ScNiSb based on our screening results. Peak zT values of ~0.5 at 925 K in p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb0.97Sn0.03 and ~ 0.3 at 778 K in n-type Sc0.65Y0.3Ti0.05NiSb were experimentally achieved.

Results and discussion

Dataset and descriptors

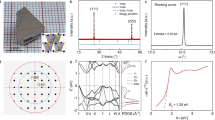

We recognized 456 half-Heusler compounds from the total database in the Materials Project using the Application Programming Interface (API)43,44, among which 20 experimentally reported TE materials, such as ZrNiSn11, ZrCoSb13, VFeSb16, and NbFeSb45, etc., were labeled in Supplementary Table 1, including the unstable 18-electron (The energy above hull (Ehull) is greater than 0, marked by *), 19-electron (marked by+), and stable 18-electron (Ehull is equal to 0, without marks) compounds. Four types of characteristics describing TE performance that provided by the Materials Project were employed as features to classify the compounds. (i) Basic information10 includes formation energy, final energy, energy above the hull, lattice constant, volume, and density. (ii) Crystal structural information (Fig. 1a)46,47 was represented by the 2theta of the top ten strong peaks that in the 2theta range of 10°–90° and the corresponding crystal plane spacing, which were extracted from the calculated X-ray diffraction patterns, as shown in Fig. 1b (We used TiNiSn as an example.). (iii) Band structure and density of states information that are very important for prediction of the TE properties were collected as follows with two spin states (spin up and spin down) considered (Fig. 1c and e, MnCoSb)10. For the materials with one spin state, we assumed that the energy of the two spin states is equal to each other (Fig. 1d and f, TiNiSn). The mean, standard deviation, maximum, and minimum energy values of five energy bands respectively above and below the Fermi level for both spin states in Fig. 1c and d were thus calculated. The energies at high symmetry point (Γ, X, W, K, L, U) and midpoint of adjacent high symmetry points (Γ-X-W-K-Γ-L-U-W-L-K | U-X) in the first Brillouin zone path of ten energy bands for each spin state were also defined as the features (see the intersections between the energy bands and the grey solid lines, as well as blue the dotted lines in Fig. 1c and d). Similarly, the mean, standard deviation, maximum, and minimum values of the total density of states for two spin states were respectively calculated. Figure 1e and Fig. 1f describe that the density of states of 21 energy points equally spaced in the energy range of ±3 eV above and below Fermi level were determined. Finally, the band gap (Eg), Fermi level (EF), and the density of states at EF were calculated. (iv) The elasticity properties48, including bulk modulus, shear modulus, and Poisson’s ratio, were also considered. The missing value was indicated by zero. Therefore, we generated 484 features for 456 compounds.

a Crystal structure and b calculated X-Ray diffraction patterns of TiNiSn (materials_id: mp-924130 in the Materials Project)). c, d Band structure and e, f density of states for two spin states material (e.g., MnCoSb (materials_id: mp-5381)) and one spin state material (e.g., TiNiSn (materials_id: mp-22377 in the Materials Project)), respectively.

Iterative unsupervised machine learning process

Figure 2 depicts the iterative process of unsupervised learning. We performed clustering to group half-Heuslers using seven different algorithms (K-means, Gaussian Mixture, Spectral clustering, DBSCAN, Mean Shift, AGNES, and Birch, each of which was briefly introduced in the Supplementary Note 1) from three unsupervised clustering categories (Prototype-based clustering, Density-based Clustering, and Hierarchical clustering). The results for each clustering were presented in Supplementary Table 1–9 and the detailed discussion about the choice of algorithms can be found in the Supplementary Note 2. For the first clustering in Fig. 2a, K-means, DBSCAN and AGNES were selected because they have a higher assessment score and a better clustering behavior. K-means grouped 456 materials into four clusters, each of which contains 244, 36, 20, and 156 samples. The known half-Heusler TE materials were distributed in the first and the fourth clusters as shown in Fig. 3 (First clustering), which means the samples in these two clusters (totally 400 samples in blue circles for K-mean in Fig. 2a) have the similar features with the known TE materials and were able to be considered as the potential half-Heuslers for the TE application. The other 56 samples in white circles were then excluded as non-TE materials for K-mean in Fig. 2a. DBSCAN allocated all the samples into six different clusters. The number of TE samples is 414, of non-TE samples is 42 because the first and the second clusters contain the known half-Heusler materials as described in Fig. 3 (First clustering). When the AGNES algorithm was applied, five clusters were obtained as shown in Fig. 2a. Figure 3 (First clustering) shows that the known half-Heusler TE materials were all distributed in the third cluster, resulting in 241 potential TE materials and 215 non-TE materials. Filter out the non-TE materials as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a and delete the samples repeatedly appear at least twice (58 samples in the purple region) in three clustering methods. The initial data were reduced to 398. The same clustering process was executed again on the 398 dataset. K-means, DBSCAN, Birch were selected for the second clustering and the results were presented in Fig. 2b and Fig. 3 (Second clustering). The data were minimized to 251 through deleting the non-TE samples (147 samples in the purple region of Supplementary Fig. 1b) after the second clustering (this process is identical to the first clustering).

The group results of a the first, b the second, c the third, and d the fourth clustering. The clusters that contain the known thermoelectric materials are represented by the blue circles and defined as the TE cluster. Accordingly, the white circles are the Non-TE clusters without the reported thermoelectric materials. The blue circles with a red star in c includes reported unstable materials, with red plus and no labels in d includes reported 19-electron and stable 18-electron materials.

When we continued to group the 251 samples, K-means, DBSCAN, and AGNES were preferred as shown in Fig. 2c. We found that the number of non-TE materials is 11, 6, and 0 when using K-means, DBSCAN, and AGNES, respectively as shown in the white circles of Fig. 2c, indicating that our models considered most of the 251 compounds are promising TE materials. Specifically, these algorithms tended to group the published unstable compounds, stable 19-electron compounds and 18-electron compounds into different sets (Third clustering in Fig. 3), which means these algorithms can successfully detect the specific character for three kinds of materials by our features. For example, the third clustering in Fig. 3 showed that the K-mean algorithm inclined to assemble the most unstable compounds (marked by *) into the second cluster, stable 19-electron compounds (marked by+) into the fourth cluster and the stable 18-electron compounds (without marks) into the first cluster. We hope to find that the stable materials can be experimentally synthesized, so we then marked the clusters contain the unstable compounds by the red star in Fig. 2c according to the results in Fig. 3 (Third clustering). We screened the samples in these clusters and omitted the unstable samples that repeatedly appear at least twice in three clustering methods (111 samples in the purple region of Supplementary Fig. 1c), the number of data was further reduced to 140.

DBSCAN and Birch were selected for the fourth clustering as shown in Fig. 2d and Fig. 3 (Fourth clustering). Most of the unstable compounds, even includes the labeled reported unstable 18-electron materials, have been eliminated during the process of the third iteration, so just the labeled stable 18-electron and 19-electron compounds were considered in the fourth clustering as demonstrated in the fourth clustering of Fig. 3. We would like to explore the 18-electron half-Heusler TE materials (without marks in Fig. 2d) since they have been explored as most potential TE materials due to their high TE performance associated with their semiconducting nature. In order to obtain the materials that are more likely to be promising TE compounds, we selected the intersection of the samples in the 18-electron TE clusters (the unlabeled blue circles in Fig. 2d) between the two algorithms. Finally, 61 materials (the purple region of Supplementary Fig. 1d) were determined.

Potential TE materials and the experimental validation

Figure 4 presents the scatter plot of Ehull versus Eg (Fig. 4a) and bulk modulus and Poisson’s ratio versus shear modulus (Fig. 4b) for the final determined TE materials. Figure 4a shows that the Eg of the majority potential TE materials distributed in the range of 0.2–1.2 eV, in accordance with the theory that the best TE materials are identified to be narrow band gap semiconductors. The prediction of Eg by first-principles calculations may be less accurate in the Materials Project, but the range of 0.2–1.2 eV is still reasonable despite the true Eg fluctuates near this range. The minority of materials with Ehull > 0 are predicted as depicted in Fig. 4a since some calculated unstable materials have indeed been experimentally synthesized (e.g., HfCoSb in Fig. 3). Figure 4b indicates the shear modulus, bulk modulus and Poisson’s ratio are in the range of 32–87 GPa, 58–175 GPa, and 0.04–0.39, respectively, which represents the mechanical properties distribution of the 61 promising TE materials. We subsequently applied two searching criteria on the screened 61 half-Heusler materials based on the band structure and thermodynamic stability theory for further investigation: (1) Ehull < 0.1 eV, (2) 0.2 < Eg < 1.2 eV. Considering the real application, the materials contain radioactive elements (e.g., Th) and platinum series noble elements (e.g., Rh, Ru) were excluded. As a result, 20 promising TE materials were obtained among the 436 unlabeled samples as shown in Supplementary Table 10, including three systems: ANiZ (A = Y, Lu, Er, Sc, Tb, Tm, Ho, Dy, Pr, Sm, Z = Sb, Bi), MFeTe (M = Zr, Ti), and NCoTe (N = Sc). Although MFeTe (M = Zr, Ti) and NCoTe (N = Sc) are not included in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), they have the potential to be exploited in the further. Besides, if the calculated bandgaps and bandstructures can be more accurate in the future, they will be expected as more deliberated descriptors for the exploration of the half-Heusler thermoelectric materials.

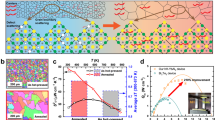

We alloyed ScNiSb with different content of YNiSb (Supplementary Fig. 2) and obtained the best zT when alloying 30 at. % YNiSb. Then we optimized the TE performance of Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb by p-type doping with 2–6 at. % Sn on the Sb site as well as n-type doping with 3–8 at. % Ti on the Sc site. ScNiSb, Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb1−xSnx (x = 0.02, 0.03, and 0.04) and Sc0.7−yY0.3TiyNiSb (y = 0.03, 0.05, and 0.08) samples were prepared by levitation melting, ball-milling and spark plasma sintering (SPS) method. All the main diffraction peaks can be well indexed to a MgAgAs-type crystal structure with a space group of \(F\bar 43{{{\mathrm{m}}}}\) (see Supplementary Fig. 3). The temperature dependence of σ and S of all the compounds are respectively shown in Fig. 5a and b. The σ of ScNiSb monotonically increases with temperature over the entire temperature range of 300 K to 975 K, showing semiconducting behavior. With the x increases in Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb1−xSnx or y increases in Sc0.7−yY0.3TiyNiSb, the σ increases, and all the doped samples reduces as temperature increases which is a remarkable feature of heavily doped degenerate semiconductors. The room-temperature optimal σ of p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb1−xSnx is 3.1 × 105 S m−1 at x = 0.03, which is higher than that of n-type Sc0.7−yY0.3TiyNiSb (1.6 × 105 S m−1) at y = 0.05. The S of Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb1−xSnx is positive, of Sc0.7−yY0.3TiyNiSb is negative, indicating holes and electrons as the majority carrier type for two types of semiconductors, respectively. The S of ScNiSb increases below 475 K then decreases until 975 K, which results from the relatively narrow Eg of ~0.32 eV (obtained from the Materials Project) for ScNiSb. For the samples alloyed by YNiSb and doped with 2–6 at. % Sn or 3–7 at. % Ti, the bipolar diffusion was gradually suppressed due to the larger Eg of YNiSb (0.35 eV, which is from the Materials Project) and the optimized carrier concentration. The change in the σ and S finally results in a considerable improved PF for p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb0.97Sn0.03 (~27.5 × 10−4 W m−1 K−2 at 671 K) and n-type Sc0.65Y0.3T0.05NiSb (~16.2 W m−1 K−2 at 773 K) compared to that of ScNiSb (~ 12.5 W m−1 K−2 at 567 K) (see Fig. 5c), which is very helpful for the improvement of the zT value. To further clarify the transport properties, we conducted temperature-dependent Hall measurements and presented the Hall carrier concentration (nH) in Fig. 5d. The room- temperature nH increases from ∼9.58 × 1019 cm−3 to ∼4.74 × 1020 cm−3 for the p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb1−xSnx samples, and from ∼4.84 × 1020 cm−3 to ∼1.03 × 1021 cm−3 for the n-type Sc0.7−yY0.3TiyNiSb samples. This indicates that Sn or Ti is efficient dopant for supplying a high concentration of holes or electrons to ScNiSb. The nH nearly maintains constant with the increased temperature for the optimized compounds that is consistent with the behavior of inhibited bipolar diffusion in the plot of S versus temperature. We also calculated the Hall mobility (µH) and presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. The room-temperature µH decreases from 56 cm2V−1s−1 to 27 cm2V−1s−1 and from 39 cm2V−1s−1 to 8 cm2 V−1 s−1 for the p-type and n-type samples, respectively when the fraction of Sn or Ti increases.

The band structure and iso-energy surfaces for ScNiSb were shown in Fig. 6. Figure 6a shows that the indirect Eg is ~0.11 eV, slightly lower than that extracted from the Materials Project database (0.32 eV). The conduction band minimum locates at the X point (Fig. 6a) and yields a band degeneracy of three (Fig. 6b) for n-type ScNiSb. The valence band maximum locates at the Г point (Fig. 6a) with a carrier pocket degeneracy of one (Fig. 6c), where three valence bands effectively converge (Fig. 6a) and thus leading to a valley degeneracy of three for p-type ScNiSb. Hence, p-type and n-type ScNiSb-based compounds could demonstrate a comparable electrical thermoelectric performance.

The κ and κL of all the samples demonstrate a noticeable reduction compared with that of ScNiSb as shown respectively in Fig. 7a and b. The room-temperature κ of the undoped ScNiSb is ~10.3 W m−1 K−1, of p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb0.98Sn0.02 is ~4.2 W m−1 K−1, and of n-type Sc0.67Y0.3T0.03NiSb is ~4.5 W m−1 K−1. The room-temperature κL in Fig. 7b decreases from ~10.2 W m−1 K−1 for the ScNiSb to ~3.1 W m−1 K−1 for the p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb0.96Sn0.04, which is the lowest κL among all samples in this work, and to ~4.2 W m−1 K−1 for the n-type Sc0.67Y0.3T0.03NiSb. The ~60% reduction of the lattice thermal conductivity is attributed to the point defects scattering mostly caused by the distortion when the Sc site was replaced by Y atoms and less contribution because Sb (or Sc) site was doped by Sn (or Ti). The temperature-dependent dimensionless figure of merit zT for p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb1−xSnx (x = 0.02, 0.03, and 0.04) and n-type Sc0.7−yY0.3TiyNiSb (y = 0.03, 0.05, and 0.08) are shown respectively in Fig. 7c and d. A greatly improved zT occurs in all solution compounds compared with the pristine ScNiSb due to the combination of the improved electrical performance and the reduced thermal properties. Peak zTs of 0.5 at 925 K for p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb0.97Sn0.03 and 0.3 at 778 K for n-type Sc0.65Y0.3Ti0.05NiSb were achieved, suggesting the promising application of ScNiSb-based half-Heuslers. Other strategies are needed for the further enhanced TE properties.

In summary, we have proposed an iterative unsupervised machine learning strategy to discover and design a series of promising half-Heusler thermoelectric materials. Enhanced zT values of 0.5 at 925 K for p-type Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb0.97Sn0.03 and 0.3 at 778 K for n-type Sc0.65Y0.3Ti0.05NiSb were obtained by alloying Y at the Sc site and doping Sn/Ti at the Sb/Sc site. Hence, it is an alternative way to explore TE materials using the unsupervised machine learning with the reported target materials and thereby will accelerate the optimization of high-performance TE materials among the inorganic materials.

Methods

Workflow

Figure 8 shows the workflow diagram of this study. 456 different half-Heusler compounds and their corresponding descriptors, i.e., structure information, band structure, the density of states and elasticity properties were successfully extracted from the Materials Project. We respectively chose three algorithms from three unsupervised learning categories to group half-Heusler compounds into different clusters and determined which clusters include the known expected half-Heusler TE materials. Filtering out the compounds in the clusters with or without the expected materials and deleting or maintaining the samples repeatedly appear at least twice in three clustering methods. Finally, 61 compounds were determined. We applied two searching criteria on the screened 61 half-Heusler materials and resulted in 18-electron entries of 20 for TE application.

Unsupervised learning

Scikit-learn49 is an open-source machine learning library using the python programming language. In this work, prototype-based clustering, density-based clustering, and hierarchical clustering were implemented by sklearn.cluster for the exploration of promising half-Heusler TE materials. The predictive performance is assessed by the silhouette score (sc(i)) and calinski harabasz score (ch), which were implemented by sklearn.metrics. The clustering result is positively correlated with sc(i) and ch. The silhouette score and calinski harabasz score are respectively characterized as follows50:

here ai is the average distance between sample i and all other objects in the same cluster, bi is the mean distance from i to all points in C (where C ≠ Ci), n is the number of clusters, k is the cluster index, Tr(Bk) and Tr(Wk) are the trace of the between-cluster dispersion matrix and the within-cluster dispersion matrix.

Synthesis

The ingots with nominal compositions ScNiSb, Sc0.7Y0.3NiSb1−xSnx (x = 0.02, 0.03, and 0.04) and Sc0.7−yY0.3TiyNiSb (x = 0.03, 0.05, and 0.08) were prepared by levitation melting of elements Sc (chunks, 99.9%), Y (chunks, 99.5%), Ti (sheets, 99.995%), Ni (rods, 99.98%), Sb (chunks, 99.999%), and Sn (chunks, 99.8%) under an argon-protected atmosphere. A small amount of extra Sb was added to compensate for the weight loss of Sb due to its high vapor pressure. The ingots were remelted fourth to ensure homogeneity. Mechanical milling was carried out for 4 h by a high-energy ball mill (SPEX 8000 M). The powder was loaded into a graphite die with an inner diameter of 12.7 mm and condensed at 1173 K for 10 min with an axial pressure of 50 MPa by spark plasma sintering (SPS).

Characterization

The crystal structures were examined by XRD (Rigaku D/max 2500 PC). The Seebeck coefficient (S) and electrical conductivity (σ) were simultaneously obtained on a commercial (ZEM-3, Advance-Riko) system in a helium atmosphere. The thermal conductivity was calculated based on κ = DCpρ using the thermal diffusivity D (LFA 457, Netzsch), specific heat Cp (DSC 404 C, Netzsch), and mass density ρ (Archimedes’ kit). The temperature-dependent Hall coefficients (RH) were measured using the van der Pauw technique under a reversible magnetic field of 1.5 T. The nH and μH were calculated using nH = 1/(eRH) and μH = σRH, respectively.

Calculations method

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out using the Projector-Augmented Wave (PAW) method as implemented in the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP). The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) was used to solve the Kohn Sham equations. The plane-wave energy cutoff and energy convergence criterion were set as 500 and 10−5 eV, respectively. A 25 × 25 × 25 gamma-center k mesh was used to sample the Brillouin zone for high k-dense computation. The Fermi surfaces were visualized using XCrySDen51.

Data availability

Source data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Coda availability

Code is available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Q. et al. Deep defect level engineering: a strategy of optimizing the carrier concentration for high thermoelectric performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 933–940 (2018).

Liu, W. et al. New trends, strategies and opportunities in thermoelectric materials: a perspective. Mater. Today Phys. 1, 50–60 (2017).

Chen, S. & Ren, Z. Recent progress of half-Heusler for moderate temperature thermoelectric applications. Mater. Today 16, 387–395 (2013).

Shi, X., Chen, L. & Uher, C. Recent advances in high-performance bulk thermoelectric materials. Int. Mater. Rev. 61, 379–415 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Phase boundary mapping in ZrNiSn half-Heusler for enhanced thermoelectric performance. Research 2020, 4630948 (2020).

Wang, R. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of n-type TiCoSb half-Heusler by Ta doping and Hf alloying. Rare Met. 40, 40–47 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance in Ti(Fe, Co, Ni)Sb pseudo-ternary half-Heusler alloys. J. Materiomics 7, 756–765 (2021).

Xia, K., Hu, C., Fu, C., Zhao, X. & Zhu, T. Half-Heusler thermoelectric materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 140503 (2021).

Fu, C. et al. Realizing high figure of merit in heavy-band p-type half-Heusler thermoelectric materials. Nat. Commun. 6, 8144 (2015).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Kim, K. et al. Direct observation of inherent atomic-scale defect disorders responsible for high-performance Ti1−xHfxNiSn1−ySby half-Heusler thermoelectric alloys. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702091 (2017).

Yu, C. et al. High-performance half-Heusler thermoelectric materials Hf1−xZrxNiSn1−ySby prepared by levitation melting and spark plasma sintering. Acta Mater. 57, 2757–2764 (2009).

Hu, C., Xia, K., Chen, X., Zhao, X. & Zhu, T. Transport mechanisms and property optimization of p-type (Zr, Hf)CoSb half-Heusler thermoelectric materials. Mater. Today Phys. 7, 69–76 (2018).

He, R. et al. Improved thermoelectric performance of n-type half-Heusler MCo1−xNixSb (M = Hf, Zr). Mater. Today Phys. 1, 24–30 (2017).

Yan, R., Xie, W., Balke, B., Chen, G. & Weidenkaff, A. Realizing p-type NbCoSn half-Heusler compounds with enhanced thermoelectric performance via Sc substitution. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 21, 122–130 (2020).

El, A. et al. Effects of spark plasma sintering on enhancing the thermoelectric performance of Hf–Ti doped VFeSb half-Heusler alloys. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 150, 109848 (2021).

Zhu, H. et al. Discovery of TaFeSb-based half-Heuslers with high thermoelectric performance. Nat. Commun. 10, 270 (2019).

Zhu, H. et al. Discovery of ZrCoBi based half Heuslers with high thermoelectric conversion efficiency. Nat. Commun. 9, 2497 (2018).

Schmidt, J., Marques, M. R. G., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. L. Recent advances and applications of machine learning in solid-state materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 83 (2019).

Yu, J. et al. Machine learning-guided design and development of metallic structural materials. J. Mater. Inf. 1, 9 (2021).

Xi, L. et al. Discovery of high-performance thermoelectric chalcogenides through reliable High-Throughput material screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10785–10793 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. Evaluation of half-Heusler compounds as thermoelectric materials based on the calculated electrical transport properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 18, 2880–2888 (2008).

Yu, J., Wang, C., Chen, Y., Wang, C. & Liu, X. Accelerated design of L12-strengthened Co-base superalloys based on machine learning of experimental data. Mater. Des. 195, 108996 (2020).

Yu, J. et al. A two-stage predicting model for γ′ solvus temperature of L12-strengthened Co-base superalloys based on machine learning. Intermetallics 110, 106466 (2019).

Zhang, D. & Tsai, J. J. P. Machine learning and software engineering. Softw. Qual. J. 11, 87–119 (2003).

Flach, P. A. On the state of the art in machine learning: a personal review. Artif. Intell. 131, 199–222 (2001).

Zhu, T. et al. Charting lattice thermal conductivity for inorganic crystals and discovering rare earth chalcogenides for thermoelectrics. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3559–3566 (2021).

Kolb, B., Luo, X., Zhou, X., Jiang, B. & Guo, H. High-dimensional atomistic neural network potentials for molecule-surface interactions: HCl scattering from Au(111). J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 666–672 (2017).

Isayev, O. et al. Universal fragment descriptors for predicting properties of inorganic crystals. Nat. Commun. 8, 15679 (2017).

Zong, H., Luo, Y., Ding, X., Lookman, T. & Ackland, G. J. Hcp → ω phase transition mechanisms in shocked zirconium: A machine learning based atomic simulation study. Acta Mater. 162, 126–135 (2019).

Li, W., Field, K. G. & Morgan, D. Automated defect analysis in electron microscopic images. npj Comput. Mater. 4, 36 (2018).

Im, J. et al. Identifying Pb-free perovskites for solar cells by machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 37 (2019).

Furmanchuk, A. et al. Prediction of seebeck coefficient for compounds without restriction to fixed stoichiometry: A machine learning approach. J. Comput. Chem. 39, 191–201 (2018).

Sheng, Y. et al. Active learning for the power factor prediction in diamond-like thermoelectric materials. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 171 (2020).

Chen, L., Tran, H., Batra, R., Kim, C. & Ramprasad, R. Machine learning models for the lattice thermal conductivity prediction of inorganic materials. Comp. Mater. Sci. 170, 109155 (2019).

Carrete, J., Mingo, N., Wang, S. & Curtarolo, S. Nanograined half-Heusler semiconductors as advanced thermoelectrics: an Ab Initio High-Throughput statistical study. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 7427–7432 (2014).

Wei, J. et al. Machine learning in materials science. InfoMat 1, 338–358 (2019).

Bastanlar, Y. & Ozuysal, M. Introduction to machine learning. Methods Mol. Biol. 1107, 105–128 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Unsupervised discovery of solid-state lithium ion conductors. Nat. Commun. 10, 5260 (2019).

Ciesielski, K. et al. Thermoelectric performance of the half-Heusler phases RNiSb (R = Sc, Dy, Er, Tm, Lu): high mobility ratio between majority and minority charge carriers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 054046 (2020).

Xiao, K., Zhu, T., Yu, C., Yang, S. & Zhao, X. The effect of Ti doping on the thermoelectric properties of YNiSb half-Heusler alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 29, 187–190 (2011).

Synoradzki, K. et al. Thermal and electronic transport properties of the Half-Heusler phase ScNiSb. Materials 12, 1723 (2019).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Comp. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Ong, S. P. et al. The Materials Application Programming Interface (API): a simple, flexible and efficient API for materials data based on Representational State Transfer (REST) principles. Comp. Mater. Sci. 97, 209–215 (2015).

Pedersen, S. V. et al. Novel synthesis and processing effects on the figure of merit for NbCoSn, NbFeSb, and ZrNiSn based half-Heusler thermoelectrics. J. Solid State Chem. 285, 121203 (2020).

Mathew, K. et al. High-throughput computational X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Sci. Data 5, 180151 (2018).

Zheng, C. et al. Automated generation and ensemble-learned matching of X-ray absorption spectra. npj Comput. Mater. 4, 12 (2018).

Jong, D. M. et al. Charting the complete elastic properties of inorganic crystalline compounds. Sci. Data 2, 150009 (2015).

Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G. E., Gramfort, A., Michel, V. & Thirion, B. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Wang, J., Zhang, W., Hua, T. & Wei, T.-C. Unsupervised learning of topological phase transitions using the Calinski-Harabaz index. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 013074 (2021).

Kokalj, A. XCrySDen - a new program for displaying crystalline structures and electron densities. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 17, 176–179 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2020YFB0704503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51871081, 51971081, and 51971082), the Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of Guangdong Province of China (2020B1515020023), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KQTD20200820113045081), and Key Project of Shenzhen Fundamental Research Projects (JCYJ20200109113418655).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z., X.L., and F.C. supervised the project. Q.Z., X.L., F.C., X.J., and Y.D. conceived the idea. X.J. and Y.D. performed the machine learning studies. X.J., Y.D., and X.B. performed the experiment. H.Y. carried out the DFT simulations. All the authors discuss the calculation and experiment results. X.J., J.M., Q.Z., and X.L. wrote the paper. X.J. and Y.D. contributed equally to this work. All listed authors agree to all manuscript contents, the author list and its order and the author contribution statements.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, X., Deng, Y., Bao, X. et al. Unsupervised machine learning for discovery of promising half-Heusler thermoelectric materials. npj Comput Mater 8, 34 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00723-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00723-9

This article is cited by

-

Hierarchy-boosted funnel learning for identifying semiconductors with ultralow lattice thermal conductivity

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

An Interpretable Machine Learning Workflow for Evaluating and Analyzing the Performance of Thermoelectric Materials

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2025)

-

Machine learning strategies for small sample size in materials science

Science China Materials (2025)

-

Classification of battery compounds using structure-free Mendeleev encodings

Journal of Cheminformatics (2024)

-

Dealing with the big data challenges in AI for thermoelectric materials

Science China Materials (2024)