Abstract

Discovery of novel materials is slow but necessary for societal progress. Here, we demonstrate a closed-loop machine learning (ML) approach to rapidly explore a large materials search space, accelerating the intentional discovery of superconducting compounds. By experimentally validating the results of the ML-generated superconductivity predictions and feeding those data back into the ML model to refine, we demonstrate that success rates for superconductor discovery can be more than doubled. Through four closed-loop cycles, we report discovery of a superconductor in the Zr-In-Ni system, re-discovery of five superconductors unknown in the training datasets, and identification of two additional phase diagrams of interest for new superconducting materials. Our work demonstrates the critical role experimental feedback provides in ML-driven discovery, and provides a blueprint for how to accelerate materials progress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of novel materials drives industrial innovation1,2,3, although the pace of discovery tends to be slow due to the infrequency of “Eureka!” moments4,5. These moments are typically tangential to the original target of the experimental work: “accidental discoveries”. Here we demonstrate the acceleration of intentional materials discovery—targeting material properties of interest while generalizing the search to a large materials space with machine learning (ML) methods combined with experiment in a feedback loop. We demonstrate a closed-loop joint ML-experimental discovery process targeting unreported superconducting materials, which have industrial applications ranging from quantum computing to sensors to power delivery6,7,8,9. By closing the loop, i.e., by experimentally testing the results of the ML-generated superconductivity predictions and feeding data back into the ML model to refine, we demonstrate that success rates for superconductor discovery can be more than doubled10. In four closed-loop cycles, we discovered an unreported superconductor in the Zr-In-Ni system, re-discovered five superconductors unknown in the training datasets, and identified two additional phase diagrams of interest for superconducting materials. Our work demonstrates the critical role experimental feedback provides in ML-driven discovery, and provides definite evidence that such technologies can accelerate discovery even in the absence of knowledge of the underlying physics.

Statistical approaches have long aimed to better understand and predict superconductivity11, most recently through the use of black-box ML methods12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Although resulting in numerous predictions, these studies have not yielded previously unreported families of superconductors, likely not only because of difficulties in extrapolating beyond known families, but also because the predicted materials have chemical attributes that make them unlikely to be superconducting—whether it is highly localized chemical bonding, e.g., those containing polyatomic anions, or an extreme metastability that precludes synthesizability. Further, existing works have treated materials and databases of material properties as fixed snapshots rather than evolving systems, which limits the ability of ML models to learn over sparse data.

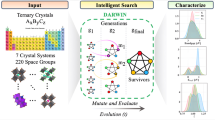

Here we report on combining ML techniques with materials science and physics expertise to “close the loop” of materials discovery (Fig. 1). We demonstrate how to make ML models generalize across diverse materials spaces, to identify superconductors that are dissimilar to ones in the training corpus. By alternating between ML property prediction and experimental verification, we are able to systematically improve the fidelity of ML property prediction in regimes sparsely represented by existing materials databases. Crucially, this adds both negative data (materials incorrectly predicted to be superconductors) and positive data (materials correctly predicted) to ML training, enabling the ML model’s overall representation of the space of materials to be iteratively refined. The result is a ML model for predicting superconductivity that doubles the rate of successful predictions10, demonstrating the acceleration of materials discovery by combining human and machine insight.

Starting from curated experimental data of known superconductors (1), compositional information is first transformed into a representation suitable for learning using the RooSt27 framework (2). After initial training of the ML model (3), we provide new compositions not known to the ML model from other sources, and obtain predictions of superconducting behavior (4). The synthesizability of these predictions is assessed using a combination of computational thermodynamic data and expert insight (5). Materials downselection (6) occurs with human input based on multiple criteria to maximize the impact experimental work has on model improvement and related factors. Chosen materials are then synthesized and structural and physical properties measured (7). Results are then fed back into the learning process, in addition to generating discoveries. Further details on the closed loop process are in “Closed-loop discovery process” in Methods. RooSt images used with permission, CC-BY-4.0 license27.

Our process uses active learning19 to iteratively select data points to be added to a training set. In particular, we select materials that are both predicted to be high transition temperature (Tc) superconductors and are sufficiently distinct from known superconductors. We also leverage human domain expertise to further refine selections. When the predictive model incorrectly predicts non-superconductors as superconductors, this valuable negative data helps refine the model’s prediction surface.

A key attribute of our work is that the training data used in the ML models is not static, but evolves as the closed-loop process proceeds. A ML model that is employing a closed loop framework, actively sampling regions of previously unexplored spaces of materials, and continually acquiring new data cannot have a concise picture of convergence, and it is changed with every loop. Thus instead of a traditional convergence metric (e.g., looking for a flattening of loss versus number of training epochs for a convolutional neural network), we leverage goal-based metrics—when the model successfully predicts superconductors not in the training set or the human in the loop assesses that model outputs are sufficiently distinct and chemically plausible from prior predictions. This helps avoid model overfitting by terminating the process earlier than a traditional metric, while maximizing the usefulness of the new experimental data to further refine the model.

Utilizing this iterative “closed-loop” approach, we rediscover five known superconductors outside of the ML model’s training set, Table 1. These materials come from a wide variety of families: iron pnictides, doped 2D ternary transition metal nitride halides, and intermetallics, Table 2. We then further report the discovery of a previously unreported superconductor in the Zr-In-Ni phase diagram, and identified two other phase diagrams of interest (Zr-In-Cu and Zr-Fe-Sn).

Results and discussion

Model generation

For the initial prediction step of the closed-loop approach, we trained an ML model to predict the superconducting transition temperature, Tc, of candidate materials. Our primary source of training data, SuperCon20, contains compositions of known superconductors. Only the materials’ compositions were used to train the ML model for predicting Tc since SuperCon did not contain additional structural information. Materials Project (MP)21 and Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD)22, some of the largest public sets of computational materials data, supplied candidate compositions to be screened for superconductivity. These two databases do not contain any Tc data. These three datasets are visualized in Fig. 2 using a joint representation. Crucially, the amount of data for which we have superconducting information is much smaller than our other sources of data and is not uniformly sampled across the joint space.

Histograms of the concentration of materials from a Uniform Manifold and Projection (UMAP)60 embedding of OQMD (without superconductivity information), MP (without superconductivity information), and SuperCon (superconductivity information), based on Magpie30 descriptors for the datasets. The embedding is learned from concatenation of Magpie descriptors obtained from all three datasets; the same axis limits are used across each subplot. These maps show the sparseness of knowledge of data about superconductivity compared to that of all known and predicted compounds in these open databases. Tc is not part of the Magpie descriptors and, therefore, did not influence the representation. The five black symbols indicate rediscovered superconductors (Table 1), and the red symbol our superconductor, near “ZrNiIn4''. The inset on the right highlights the local region in which “ZrNiIn4” is found, which is sparse and far from the known and rediscovered superconductors.

It is well-known23 that when ML methods make predictions on data outside of their training data distribution, accuracy often suffers; this is often called the out-of-distribution generalization problem. In cheminformatics24, it is common to assess whether a dataset is within the distribution of a training dataset by seeing how far, in some representative metric space, its points are from the training dataset: as the difference between the distribution of new data and the training data increases, the likelihood that a model will accurately predict their properties decreases. To improve assessment of generalization, out-of-distribution data may be simulated by creating validation sets that split based on non-random criteria like Murcko scaffold25 or cluster identity, the latter being the leave-one-cluster-out cross-validation (LOCO-CV) strategy26.

In “Model Validation” in Methods, we apply LOCO-CV in a simulated superconductor-identification problem. We show that, although a strong ML model is capable of fitting the training set well and generalizing to out-of-distribution test data, it fails to make accurate predictions of superconducting status on out-of-distribution data. Because existing superconductor datasets are not sufficient to enable accurate identification of unreported superconductors, this motivates the need for multiple iterations of model training, candidate selection, candidate synthesis, and model retraining.

We rely on a recent ML model for chemical property prediction, Representation learning from Stoichiometry (RooSt)27 (see “Computational Methods and Uncertainty” in Methods and the SI), to predict a material’s superconductivity using only its stoichiometry (i.e., ignoring the material’s crystal structure). Although not as immediately powerful as approaches incorporating structural information16,28,29, it enables greater predictive sensitivity because materials compositions can be tested without knowledge of the structure.

Superconductivity-specific considerations

After training an ensemble of RooSt models using the SuperCon database, we apply them to our set of potential superconductors (i.e., MP and OQMD). We filter for materials likely to be high-Tc superconductors, and then selected materials are synthesized and characterized, enabling the ML model to be retrained in further loop iterations.

A risk of searching for superconductors from a static list of candidates is that while a material in MP or OQMD may not have the exact composition as a superconductor, it may have a composition extremely close in terms of stoichiometry, such as MgB2 vs. Mg33B67. Thus, every time we produce a new list of candidates, we identify each candidate’s minimal Euclidean distance, in Magpie-space30, to any point in our training data, and we remove candidates too close to SuperCon.

It is not practical to experimentally verify all ML predictions. The costs associated with fabricating and characterizing a new material are high; hence we are only able to experimentally analyze a small subset of the ML predictions.

The MP and OQMD databases both contain calculated stability information not used by the ML model. Of 190 predicted superconductors in a given prediction round, only 39 compounds were calculated to be stable (Eoverhull = 0.00 eV/atom) but 83 were nearly stable (Eoverhull < 0.05 eV/atom). Stable materials and those with prior experimental reports were prioritized to increase the likelihood that targeted compounds could be successfully synthesized. Prioritizing these materials ensured that failures to observe superconductivity were indicative of the behavior of the targeted compound rather than a failure to synthesize that compound.

Insulating materials like β-ZrNCl and the cuprates superconduct with high Tcs because they can be doped into a metallic state31. One long-running challenge for machine-learning approaches to predicting high-Tc superconductivity is that large bandgap insulators incapable of superconductivity tend to be given overweighted classification scores, likely due to the high Tcs of the cuprates16. Therefore, metals and easily doped materials were favored for testing. Similarly, for some predicted metals, we investigated nearby compounds with similar structures that were known in literature but were not found in MP or OQMD (e.g., Zr3Fe4Sn4 and Hf3Fe4Sn432,33) and isostructural compounds with promising band structures (e.g.,: ZrNi2In).

Since the Tcs of compounds are very sensitive to alloy disorder and lattice parameter, we explored several compositions near each prediction34. We also considered the ease and safety of synthesizing the target materials (e.g., by excluding extremely high-pressure syntheses). Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to ensure that the target material was successfully synthesized and temperature-dependent AC magnetic susceptibility was used to screen for superconductivity. Superconductors are perfectly diamagnetic below their Tc with minimal applied field.

Material candidate experimental verification

To illustrate the sensitivity of experimentally-measured Tcs to processing conditions, we made and tested samples with A3B stoichiometry (Fig. 3a), including many known superconductors from the A15 family35. Similar compositional sensitivity is common in other systems beyond A15 compounds. For example, as x varies between 0 and 0.35, La2−xSrxCuO4 can vary from not superconducting to having a Tc up to 36 K15. Our experiments show that high-throughput synthesis and characterization techniques can reliably and quickly screen systems for superconductivity. Optimization of many superconducting phases requires much lower-throughput techniques for preparing phase-pure and fully-superconducting samples.

a Evaluation of our high-throughput synthesis of compounds with A3B stoichiometry (including A15 compounds) demonstrates the effects of processing on the measured Tc and our ability to positively identify superconductors quickly. For the superconductor in the Zr-In-Ni phase diagram, samples of various compositions were tested (b and c). The size of the datapoints in (c) is the fraction of the superconducting phase present as estimated from the magnitude of the transition in magnetization between 5 and 10 K (orange region). This transition was distinct from the indium-related transition (green). The compositions of samples with the strongest superconducting signals cluster near the composition “ZrNiIn4''. The metastability of the superconducting phase precluded isolation as a single phase.

Using this closed-loop method and high-throughput synthesis, we re-discovered five known superconductors that were not represented in the ML training dataset. A list of these is found in Table 1. Alongside these successful predictions, the ML model also returned compositions that experts could readily identify as not superconducting candidates. Therefore, it was important to compare the successful prediction rates of the combined human expert-machine approach and the machine-only approach. If one considers all predictions (including those not identified as promising by the human in the loop), the rate of discovery is 5/190(2.6%), comparable to expert-driven success rates of (3%)10. When materials that experts quickly identified as not realistic superconductors were excluded (the human-machine combined approach), the successful prediction rate rose to 5/65(7.5%), more than double that of previous expert-driven approaches10. This is particularly remarkable given the chemical diversity in the predicted candidates.

We were then able to use this ML model to discover unreported superconductors. Specifically, we find a superconducting phase in the Zr-In-Ni system, with a Tc of ~9 K (Fig. 3b, c and Extended Data) and approximate composition ZrNiIn4. No other known elements, binaries or ternaries in the Zr-In-Ni system would explain a superconducting transition temperature this high and the elements and binaries have been extensively investigated12,35,36,37. Unfortunately, the phase responsible for superconductivity is extremely metastable, and we have not yet found a synthesis route to obtain it in single phase form (see SI).

Conclusions

We have presented the first ever “closed-loop" ML-based directed discovery of a superconductor with experimental verification (within the Zr-Ni-In system), identified two additional systems of interest (Zr-Cu-In and Zr-Fe-Sn), and rediscovered five others not represented in our ML training set.

Past revolutionary discoveries tended to happen by serendipity, finding something in material families outside of what was known at the time. Our approach, relying only on stoichiometry and a measure of “distance” from what is currently known, is more likely to find unreported materials of interest and a sense of where unexplored but promising materials lie compared to ML-guided approaches that proceed within only a given family of materials.

This approach improves performance with experience, in that with every closing of the loop, the ML model undergoes feedback and refinement, enabling efficient exploration of materials space. These improvements ultimately will reduce the cost of materials development and discovery. The success of this approach has been demonstrated by discoveries and rediscoveries coming from vastly different families, illustrating the potential of this tool for the discovery of materials with targeted properties. This methodology can be expanded to target more than one desired property, and applied to domains beyond superconductors as long as a mechanism for new data acquisition based on ML-based predictions can be leveraged.

Further, we engaged in only a small number of total prediction/experimental measurement iterations; to maximize the superconducting transition temperatures of superconductors discovered over further iterations, we can use acquisition functions developed for Bayesian Optimization38,39. Our approach retains a human-in-the-loop for synthesizing and characterizing materials, but further automation is possible, involving, e.g., ML systems selecting experiments to be conducted, or robot-powered self-driving laboratories40,41,42. Thus we demonstrate a viable approach of these methods to accelerate materials discovery.

Methods

Data

Our initial data source containing the superconducting transition temperature, Tc of many known compounds is the SuperCon database20, published by the Japanese National Institute for Materials Science. More details and analyses about SuperCon are available in the SI.

In this work, we use the version of SuperCon released by Stanev et al.12, available online. This contains 16,414 material compositions and associated critical temperature measurements. However, some of these compositions are invalid (e.g., Y2C2Br0.5!1.5) and were removed prior to analysis. Our final training dataset has 16,304 valid compositions. In the Extended Data and the SI, we give additional detail about our training dataset. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the distribution of Tc values in our training data—note that the distribution is weighted toward low-Tc compositions.

We use MP21 and OQMD22 as the set of candidates to screen with ML for superconducting potential. MP and OQMD are some of the largest public sets of computational materials data. Their records contain full crystallographic information for material structures, along with some associated electronic and mechanical properties (but not, importantly, Tc). We scraped MP for material records present in it as of October 2020 using the MPRester class from the pymatgen43 package, obtaining 89,341 unique compositions. We later downloaded the entire OQMD v1.4 database, obtaining 252,978 unique compositions. The Extended Data contains a table of MP and OQMD material IDs used in this study.

Computational methods and uncertainty

RooSt27 is a graph neural network44 that relates material composition to properties by applying a message-passing scheme45 to a weighted graph representation of the composition’s stoichiometry, producing a real-valued embedding vector. To make a prediction, this embedding is then passed through a feedforward network.

In this work, we make use of the publicly-available implementation of RooSt, which is implemented in PyTorch46. Furthermore, we use the default hyperparameters recommended by the RooSt authors, including basing the initial species representation vectors on the matscholar embedding47. Since we seek materials likely to be high-Tc superconductors, and we expect RooSt’s classification model to poorly generalize on out of distribution data, we filter for materials predicted to be in the highest Tc tertile (Tc ≥ 20 K) with a classification score of at least 0.66 (see SI).

RooSt models incorporate two sources of uncertainty in their Tc predictions: We account for aleatoric uncertainty (randomness of input data) by letting a model estimate a mean and standard deviation for each label’s logit48, and we incorporate epistemic uncertainty (error in the model’s result, itself) by averaging over an ensemble of independently trained RooSt models49.

Problem formulation

We formulate our prediction problem as an uncertainty-aware classification task. As shown in Supplementary Information, the distribution of Tc values in SuperCon is skewed, with a large number of materials having Tcs close to 0 K. Although we could have used a regression approach and had models estimate Tc directly, the skewed and heavy-tailed Tc distribution instead prompted us to discretize Tc into three categories, based roughly on tertiles: materials with a measured Tc less than 2 K, materials with a Tc between 2 K and 20 K, and materials with a Tc above 20 K. This is similar to earlier work by Stanev et al.12, who use a two-stage prediction approach where they first classify whether a material has a Tc of greater than 10 K. Depending on the specifics of the target property, our closed-loop discovery process can be used with other ML prediction formulations as well.

In this work, we characterize the similarity between material compositions using both the RooSt latent embedding (for predicting material properties) and via Euclidean distance applied to a material composition’s Magpie30 representation, for determining if superconductor candidates are not sufficiently different than known superconductors to be considered a discovery. The choice of metric is not critical, as it is imposed simply to help broaden the range of materials space explored. Other works have considered alternative mechanisms for material similarity, just as using representations based on element fractions50 or the earth mover’s distance51. Our discovery process does not rely on use of a specific similarity measure and can adopt other measures as desired.

Model validation

SuperCon provides data as a validation experiment for our model—can RooSt successfully predict the Tc tertile of unknown materials? We evaluate this question in two settings; the first under a standard uniform cross-validation (Uniform-CV) split of SuperCon, and the second with the LOCO-CV strategy26. In this approach, we apply K-means clustering to the Magpie30 representation of SuperCon and then train K RooSt models, iteratively holding out each cluster as a test set. Since the clustering will put materials that are similar to each other in the same cluster, LOCO-CV is a better proxy for assessing how well our model will perform when used to identify superconductor candidates in MP.

In this study, we set K = 3 for the clustering and summarize cluster characteristics in Table 3 and Fig. 4. Note that even this simple clustering procedure has produced inter-cluster heterogeneity—e.g., Cluster 0 is significantly smaller than the other clusters, and Cluster 1 has the bulk of the 20 ≤ Tc superconductors.

Statistics of Tc across clusters used in the LOCO-CV study, obtained from Stanev et al.12’s version of SuperCon.

In Figs. 5 and 6, we show the results of our study. In the Uniform-CV setting, our model does well—it shows little evidence of overfitting and performs well for all three Tc categories. However, in LOCO-CV, performance degrades significantly and is also much more variable, based on what cluster is being used as the test set. Our result here echoes12, who show that models trained only on iron-based superconductors fail to accurately predict properties of cuprates, and vice versa.

Training and test set accuracies for uniform cross-validation (Uniform-CV) vs. LOCO-CV, averaged over each fold and cluster. Bars show 95% confidence intervals for the standard error of the mean estimate. The model severely overfits in the LOCO-CV case, and its test set accuracy is much more cluster-dependent and variable.

These results indicate that we should not expect an ML model trained only on SuperCon to consistently identify superconductors in out-of-distribution data, and, as points in SuperCon are more similar to each other than points in MP and OQMD (Fig. 2), the LOCO-CV results here are optimistic compared to our actual problem of interest. This motivates our need for multiple iterations of model training, candidate selection, candidate synthesis, and model retraining.

Closed-loop discovery process

The initial loop iteration used Stanev et al.’s version of SuperCon12 as training data (“Data”). After the Tc-prediction model was trained, candidates were selected from MP21 based on predicted scores (“Computational Methods and Uncertainty”). The second loop iteration used SuperCon, as well as additional measurements from the first loop, as training data, and it again used MP as the set of possible candidates. The third and fourth loops again used prior iterations’ measurements as supplementary training data, but they also combined OQMD22 to MP to obtain the set of possible candidates. The number of materials synthesized and characterized per loop iteration varied across loops, based on domain expert intuition and feasibility of synthesis. This process is summarized in Table 4.

Experiment

To synthesize compounds in a medium-throughput manner, arc melting and solid state techniques were used. The standard sample size was 500–700 mg. A list of precursors used in this project is found in Supplementary Table 1 in the SI and details of the synthetic procedures are found in the SI. Additional heat treatments were performed on an as-needed basis when isolating superconducting phases.

Powder XRD patterns were collected at room temperature on the as-melted samples using a Bruker D8 Focus powder diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (λk,α,1 = 1.540596 Å, λk,α,2 = 1.544493 Å), Soller slits, and a LynxEye detector to verify the presence of the target phase. We measured from 2θ = 5∘–60∘ with a step size of 0.018563∘ over 4 min as an initial screen. When gathering XRD patterns of samples in preparation for Rietveld refinement, 4 h measurements were performed from 2θ = 5∘–120∘ with a step size of 0.01715∘.

AC-susceptibility measurements were conducted using either a Quantum Design Magnetic Properties Measurement (MPMS) System (HDC = 10 Oe, HAC = 1 − 3 Oe, 900 Hz) or a Quantum Design Physical Properties Measurement System (HDC = 10 Oe, HAC = 3 Oe, 1 kHz), measuring T ≥ 2 K. Since prior density function theory (DFT) calculations52 suggested that CaAg2Ge2 would superconduct near T = 1.5 K, we used the 3He option with the MPMS to measure from 0.4 K to 1.7 K for that sample in addition to our standard measurement above 2 K.

Data availability

The data used to train the models used in the work were acquired from publicly available sources, and those acquired experimentally according to the procedures explained in the paper. The values acquired experimentally as part of this work are available at https://doi.org/10.34863/w3xm-w506.

References

National Research Council, Frontiers in Crystalline Matter. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press https://doi.org/10.17226/12640 (2009).

de Pablo, J. J. et al. New frontiers for the materials genome initiative. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 41 (2019).

Baird, S. G., Diep, T. Q. & Sparks, T. D. Discover: a materials discovery screening tool for high performance, unique chemical compositions. Digit. Discov. 1, 226–240 (2022).

National Science and Technology Council, Materials Genome Initiative Strategic Plan: a Report by the Subcommittee on the Materials Genome Initiative Committee on Technology of the National Science and Technology Council. https://www.mgi.gov/sites/default/files/documents/MGI-2021-Strategic-Plan.pdf (2021).

Mandrus, D. Gifts from the superconducting curiosity shop. Front. Phys. 6, 347–349 (2011).

Zhao, H. et al. Cascade of correlated electron states in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Nature 599, 216–221 (2021).

Li, Y., Xu, X., Lee, M.-H., Chu, M.-W. & Chien, C. L. Observation of half-quantum flux in the unconventional superconductor beta-Bi2Pd. Science 366, 238–241 (2019).

Mather, J. C. Super photon counters. Nature 401, 654–655 (1999).

Grant, P. Rehearsals for prime time. Nature 411, 532–533 (2001).

Hosono, H. et al. Exploration of new superconductors and functional materials, and fabrication of superconducting tapes and wires of iron pnictides. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 16(3) https://doi.org/10.1088/1468-6996/16/3/033503 (2015).

Hirsch, J. Correlations between normal-state properties and superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B. 55, 9007–9024 (1997).

Stanev, V. et al. Machine learning modeling of superconducting critical temperature. npj Comput. Mater. 4, 29 (2018).

Zeng, S. et al. Atom table convolutional neural networks for an accurate prediction of compounds properties. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 84 (2019).

Konno, T. et al. Deep learning model for finding new superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 103, 014509 (2021).

Roter, B. & Dordevic, S. V. Predicting new superconductors and their critical temperatures using machine learning. Phys. C: Supercond. 575, 1353689 (2020).

Quinn, M. R. & McQueen, T. M. Identifying new classes of high temperature superconductors with convolutional neural networks. Front. Electron. Mater. 2, 1–12 (2022).

Hoffmann, N., Cerqueira, T. F. T., Schmidt, J. & Marques, M. A. L. Superconductivity in antiperovskites. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 150 (2022).

Seegmiller, C.C, Baird, S.G, Sayeed, H.M, Sparks, T.D. Discovering chemically novel, high-temperature superconductors https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2023-8t8kt-v3 (2023).

Lookman, T., Balachandran, P. V., Xue, D. & Yuan, R. Active learning in materials science with emphasis on adaptive sampling using uncertainties for targeted design. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 21 (2019).

SuperCon (2008). https://supercon.nims.go.jp/ Accessed 2021

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the materials project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Saal, J. E., Kirklin, S., Aykol, M., Meredig, B. & Wolverton, C. Materials design and discovery with high-throughput density functional theory: the open quantum materials database (oqmd). JOM 65, 1501–1509 (2013).

Gulrajani, I, Lopez-Paz, D. In search of lost domain generalization. In: International Conference on Learning Representations https://openreview.net/forum?id=lQdXeXDoWtI (2021).

Liu, R. & Wallqvist, A. Molecular similarity-based domain applicability metric efficiently identifies out-of-domain compounds. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59, 181–189 (2019).

Bemis, G. W. & Murcko, M. A. The properties of known drugs. 1. molecular frameworks. J. Med. Chem. 39, 2887–2893 (1996).

Meredig, B. et al. Can machine learning identify the next high-temperature superconductor? examining extrapolation performance for materials discovery. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 3, 819–825 (2018).

Goodall, R. E. A. & Lee, A. A. Predicting materials properties without crystal structure: deep representation learning from stoichiometry. Nat. Comm. 11, 6280 (2020).

Xie, T. & Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 145301 (2018).

Park, C. W. & Wolverton, C. Developing an improved crystal graph convolutional neural network framework for accelerated materials discovery. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 063801 (2020).

Ward, L., Agrawal, A., Choudhary, A. & Wolverton, C. A general-purpose machine learning framework for predicting properties of inorganic materials. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 16028 (2016).

Fournier, P. T’ and infinite-layer electron-doped cuprates. Phys. C: Supercond. 514, 314–338 (2015).

Calta, N. P. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Hf3Fe4Sn4 and Hf9Fe4−xSn10+x: two stannide intermetallics with low-dimensional iron sublattices. J. Solid State Chem. 236, 130–137 (2016).

Savidan, J. C., Joubert, J. M. & Toffolon-Masclet, C. An experimental study of the Fe-Sn-Zr ternary system at 900∘C. Intermetallics 18, 2224–2228 (2010).

Matthias, B. T., Geballe, T. H., Willens, R. H., Corenzwit, E. & Hull Jr, G. W. Superconductivity of Nb3Ge. Phys. Rev. 139, 1501–1503 (1965).

Matthias, B. T., Geballe, T. H. & Compton, V. B. Superconductivity. Superconductivity 35, 1–22 (1963).

Shaw, R. W., Mapother, D. E. & Hopkins, D. C. Critical fields of superconducting tin, indium, and tantalum. Phys. Rev. 120, 88–91 (1960).

Berger, L.I, Roberts, B.W. Properties of Superconductors. In: CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 102nd edn, (eds. Rumble, J) Ch. 12 (CRC Press (Taylor and Francis), Boca Raton, FL) (2021).

Attia, P. M. et al. Closed-loop optimization of fast-charging protocols for batteries with machine learning. Nature 578, 397–402 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Apley, D. W. & Chen, W. Bayesian optimization for materials design with mixed quantitative and qualitative variables. Sci. Rep. 10, 4924 (2020).

Coley, C. W., Eyke, N. S. & Jensen, K. F. Autonomous discovery in the chemical sciences part 1: progress. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22858–22893 (2020).

Stach, E. et al. Autonomous experimentation systems for materials development: a community perspective. Matter 4, 2702–2726 (2021).

MacLeod, B. P. et al. Self-driving laboratory for accelerated discovery of thin-film materials. Sci. Adv. 6, 8867 (2020).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python materials genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Wu, Z. et al. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 32, 4–24 (2021).

Gilmer, J., Schoenholz, S.S., Riley, P.F., Vinyals, O., Dahl, G.E. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. In: Proc. 34th International Conference on Machine Learning - Volume 70. ICML’17, pp. 1263–1272. JMLR.org, Sydney, Australia https://doi.org/10.5555/3305381.3305512 (2017).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In: (eds. Wallach, H.M., Larochelle, H., Beygelzimer, A., d’Alché-Buc, F., Fox, E.B., Garnett, R.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, December 8-14, 2019, Vancouver, BC, Canada, pp. 8024–8035 https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2019/file/bdbca288fee7f92f2bfa9f7012727740-Paper.pdf (2019).

Tshitoyan, V. et al. Unsupervised word embeddings capture latent knowledge from materials science literature. Nature 571, 95–98 (2019).

Nix, D.A., Weigend, A.S. Estimating the mean and variance of the target probability distribution. In: Proc. 1994 IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks (ICNN’94), vol. 1, pp. 55–601 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICNN.1994.374138 (1994).

Lakshminarayanan, B., Pritzel, A., Blundell, C. Simple and scalable predictive uncertainty estimation using deep ensembles. In: Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. NIPS’17, pp. 6405–6416. Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA (2017)

Jha, D. et al. Elemnet: deep learning the chemistry of materials from only elemental composition. Sci. Rep. 8, 17593 (2018).

Hargreaves, C. J., Dyer, M. S., Gaultois, M. W., Kurlin, V. A. & Rosseinsky, M. J. The earth mover’s distance as a metric for the space of inorganic compositions. Chem. Mater. 32, 10610–10620 (2020).

Sinaga, G.S., Utimula, K., Nakano, K., Hongo, K., Maezono, R. First principles calculations of superconducting critical temperature of ThCr2Si2-Type Structure. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1911.10716 (2019).

Todorov, I. et al. Topotactic redox chemistry of NaFeAs in water and air and superconducting behavior with stoichiometry change. Chem. Mater. 22, 3916–3925 (2010).

Hagino, T. et al. Superconductivity in spinel-type compounds CuRh2S4 and CuRh2Se4. Phys. Rev. B 51, 12673–12684 (1995).

Hiramatsu, H. et al. Water-induced superconductivity in SrFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 80, 2–5 (2009).

Pamuk, B., Mauri, F. & Calandra, M. High- Tc superconductivity in weakly electron-doped HfNCl. Phys. Rev. B 96, 1–7 (2017).

Si, J. et al. Unconventional superconductivity induced by suppressing an Iron-Selenium-Based Mott Insulator CsFe4−xSe4. Phys. Rev. X 10, 41008 (2020).

Ying, J., Lei, H., Petrovic, C., Xiao, Y. & Struzhkin, V. V. Interplay of magnetism and superconductivity in the compressed Fe-ladder compound BaFe2Se3. Phys. Rev. B 95, 1–5 (2017).

Yamauchi, T., Hirata, Y., Ueda, Y. & Ohgushi, K. Pressure-Induced Mott Transition Followed by a 24-K Superconducting Phase in BaFe2S3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 1–5 (2015).

McInnes, L., Healy, J., Melville, J. UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.03426 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge internal financial support from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory’s Independent Research & Development (IR&D) Program for funding this work. The MPMS3 system used for magnetic characterization was funded by the National Science Foundation, Division of Materials Research, Major Research Instrumentation Program, under Award #1828490. T.M.M. acknowledges support of the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.D.S., I.M., C.D.P., E.G., K.M., and T.M.M. contributed to the conception of the work. E.A.P., B.W., T.M.M., E.G., and I.M. contributed to the setup and design of experiments. E.A.P., E.H., I.M., and B.W. synthesized samples. A.N created the ML model with some contributions from M.J.P., C.D.P., and C.R.R. J.D., N.Q.L., C.C., and C.D.P. contributed to preparation of the datasets and integrating them with the workflow. E.A.P., A.N., C.D.S., K.M. and T.M.M. heavily contributed to the writing and revising of the manuscript. E.H., E.A.P., E.G., C.C., T.M.M. and B.W. collected and analyzed experimental data. E.A.P., C.D.P., A.N., T.M.M., and G.B. introduced new ways of visualizing the data. C.D.S., C.R.R., and A.L. provided guidance on research direction and communication of results. C.R.R. advised the team on appropriate ML techniques for property prediction and A.L. advised the team on material structure-property relationships. C.D.S. was involved in all aspects of this project, providing overall leadership and helping to troubleshoot technical challenges.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pogue, E.A., New, A., McElroy, K. et al. Closed-loop superconducting materials discovery. npj Comput Mater 9, 181 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-023-01131-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-023-01131-3

This article is cited by

-

Learning design-score manifold to guide diffusion models for offline optimization

npj Artificial Intelligence (2026)

-

A general approach for determining applicability domain of machine learning models

npj Computational Materials (2025)