Abstract

The interlayer twist angle endows a new degree of freedom to manipulate the spatially separated interlayer excitons in van der Waals (vdWs) heterostructures. Herein, we find that the band-edge Γ-Γ interlayer excitation directly forms interlayer exciton in InSe/Sb heterostructure, different from that of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) heterostructures in two-step processes by intralayer excitation and transfer. By tuning the interlayer coupling and breathing vibrational modes associated with the Γ-Γ photoexcitation, the interlayer twist can significantly adjust the excitation peak position and lifetime of recombination. The interlayer excitation peak in InSe/Sb heterostructure can shift ~400 meV, and the interlayer exciton lifetime varies in hundreds of nanoseconds as a periodic function of the twist angle (0°–60°). This work enriches the understanding of interlayer exciton formation and facilitates the artificial excitonic engineering of vdWs heterostructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For 2D semiconductors, the absence of dangling bonds, short of electron and hole migration paths and superior mobility at atomic layer thickness are very beneficial to provide the long-lived photogenerated carriers compared with traditional bulk materials1,2. The long-lived photogenerated electrons and holes are critical for a broad range of applications in optoelectronics, photovoltaics, photocatalysis, sensors and biomedicine3,4. Moreover, the rational design and synthesis of 2D heterojunctions is an important strategy to further improve the lifetime of photogenerated carriers. The rapidly separating photogenerated electron holes into different sublayers have a chance to form interlayer exciton5,6,7. The long-lived interlayer excitons possess great potential to pave the way in realistically exploring Bose-Einstein condensation8, temperature superfluidity9 and light-induced exciton spin Hall effect10 new physical phenomena. Therefore, in-depth understanding and regulation of interlayer excitons in 2D heterojunctions plays an essential role in various of application of 2D semiconductor devices.

Inspired by stacking two graphene at a specific angle to present some unexpected properties, such as superconductor or insulator11,12, the interlayer twist endows a new degree of freedom to flexibly engineer the electronic structures and interlayer excitons13. To date, artificially twisted 2D semiconductor heterostructures are mainly focused on transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), which can indirectly form interlayer excitons in two steps, namely, photoexcitation forming intralayer exciton and then the photogenerated electron or hole transfer into the opposite sublayers7,14,15,16,17,18,19. It is extremely complex to the formation dynamics and corresponding regulation of the interlayer excitons induced by two-step processes20. Since the interlayer photoexcitation probability is two orders of magnitude smaller than that of intralayer excitation in TMDs 2D heterostructures21,22,23, the formation of interlayer exciton is mainly explored from indirect photoluminescence rather than direct photoabsorption7. Simultaneously, although the time scale of transfer process from intralayer to interlayer exciton can be detected by using femtosecond pump-probe spectroscopy and phase-locked electromagnetic pulses24, a comprehensive understanding of photogenerated carriers transfer is still very difficult due to the complex momentum-space indirect intervalley transfer, such as Q-Γ, Q-K, K-Γ excitons17,25,26. It is also unclear whether intralayer photogenerated carriers are transferred into interlayer in the form of free or bound carriers27,28. Therefore, to practical applications of interlayer exciton on specific devices, it is still necessary to increase the understanding of the interlayer exciton formation and regulation.

In this work, we systematically investigate the formation and regulation of interlayer exciton based on first-principles and nonadiabatic molecular dynamics (NAMD) simulations. The interlayer exciton can be directly formed by interlayer photoexcitation in 2D indium selenide/antimonene (InSe/Sb) heterostructure. The interface atoms of Sb and InSe sublayers contribute the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) of heterostructure at Γ point, respectively, which forms an interlayer Γ-Γ transition channel due to the strong interlayer coupling and short spatial distance. By uniformly taking seven twist angles in the 0°–60° range, the interlayer twist can directly affect the interlayer interaction and change the electronic structure of band edge. Then, the interlayer exciton’s lifetime and peak position can be regulated on a large scale.

Results and discussion

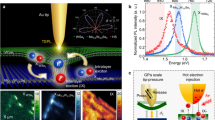

The interlayer exciton in TMDs heterostructures is formed in indirect two-step processes; that is, the intralayer exciton is firstly formed in one sublayer, and then the photogenerated electrons transfer into the other sublayer as shown in Fig. 1a ① and ② processes. The process has been confirmed by many experimental and theoretical studies7,14,24,26,28. In fact, the formation mode can be clearly illustrated from the geometry and electronic structure of the TMDs. Taking MoS2 as an example (see Fig. 1b), monolayer MoS2 is a sandwich structure with the middle Mo atom layer surrounded by two outer S atomic layers. The intermediate Mo atom layer mainly contributes to valence and conduct band edges. Hence, after forming type II TMDs heterostructures, the direct interlayer photoexcitation at band edges (see Fig. 1a, the ③ process) will be difficult due to the large spatial distance between the two Mo atomic layers. Therefore, interlayer exciton in TMDs heterostructures can only be formed in intralayer excitation and interlayer transfer mechanism.

a The schematic diagram of intralayer and interlayer excitons in 2D heterostructures and the indirect (1 and 2) and direct (3) formation processes for interlayer excitons. b, c Projection-resolved band structures for 3 × 3 supercell of MoS2 and InSe monolayers. The illustration is a side view of MoS2 and InSe monolayers. d The diagrammatic process of directly forming interlayer excitons in InSe/Sb heterostructure. e the diagram of twist angle for InSe/Sb heterostructure. f, g Projection-resolved band structures for 3 × 3 supercell of InSe and Sb monolayers. The gray region at valence and conduct band edge of sublayers may form a direct interlayer photoexcitation channel after constructing InSe/Sb heterostructure. Fermi level is set to 0 eV.

To improve the probability of interlayer photoexcitation at band edges, the band edge components should be mainly composed of interface atoms. This can reduce the photoexcitation spatial distance of carriers. InSe, possessing high electron mobility (103–104 cm2V−1s−1), on/off ratio (~108), quantum Hall effect, and anomalous optical response29,30, has attracted widespread attention in electronic and photoelectric applications. More fortunately, the pz orbital of surface Se atoms mainly contribute to its band edge states (see Fig. 1c). This can reduce the spatial distance of photoexcitation channel after forming a vertical heterojunction with the other 2D semiconductor.

2D Sb semiconductor, a group-VA material, has been successfully prepared by various methods, such as liquid or mechanical exfoliation31,32,33, vdW epitaxy growth34. As a potential 2D photoelectric material, it not only has good photoresponse property33,35, but also possesses high environmental stability36. More interesting, Sb is suitable for constructing heterojunction with InSe to explore interlayer excitation (see Fig. 1d). First of all, the VBM of Sb is located at the Γ point (see Fig. 1g), which is in agreement with the CBM of InSe. Secondly, 2D Sb is a buckled honeycomb structure, and each Sb atom is bonded to three neighboring Sb atoms. Then, the nonbonding lone pair electrons are left at the surface, which can increase the interlayer coupling after forming a vertical heterojunction. And lastly, the lattice constants of Sb (4.12 Å) and InSe (4.07 Å) are very well matched with each other. Then, by adjusting the twist angles (see Fig. 1e), the interlayer interaction can be periodically regulated, and the superlattice pattern can appear simultaneously. Therefore, the InSe/Sb heterojunction will be a suitable system to explore the direct formation of interlayer excitons and the interlayer twist regulation of interlayer excitons.

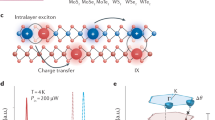

We define a highly symmetrical structure as the 0° twist angle structure as shown in Figure S1. The Sb and Se atoms at the interface of heterostructure are staggered arrangement forming strong interlayer coupling. Since 2D InSe and Sb are hexagonal lattice, after twisting 60° for one sublayer, the heterostructure can form a new highly symmetrical structure. Therefore, we evenly take seven twist angles from 0° to 60° (that is, 0.0°, 10.9°, 19.1°, 30.0°, 40.9°, 49.1° and 60.0°, see Fig. S1–S8) to investigate the formation and regulation of interlayer exciton in InSe/Sb heterostructure. According to the previously widely studied twist stacking preparation strategy for 2D materials, such as graphene, hexagonal boron nitride, TMDs, the InSe/Sb heterostructures with different twist angles have the opportunity to be prepared by using the stamping dry-transfer method19,37,38.

As expected, InSe/Sb heterostructure is a type II heterojunction (see Fig. 2a). The VBM and CBM are located at Γ point, which are contributed by Sb and InSe sublayers, respectively. The band gap of InSe/Sb heterostructure can be significantly adjusted from 0.63 to 0.91 eV by the different twist angles (see Fig. 2a–g). As presented in Fig. 2h, the highly symmetrical structures possess stronger binding energy (around −45 meV per atom) than asymmetric structures (around −35 meV per atom). It’s worth noting that even for asymmetric structures, the interlayer interactions are much stronger than typical 2D vdW interaction, such as bilayer MoS2 or graphene/MoS2 heterojunctions (around −20 meV per atom). The strong interlayer interaction of InSe/Sb heterostructure will facilitate direct interlayer photoexcitation.

a–g Projection-resolved band structures for the InSe/Sb heterostructures with different interlayer twist angles. The red and blue dots represent as the contributions of Sb and InSe sublayers, respectively. The inserted value is the band gap. Fermi level is set to 0 eV. h the average binding energy per atom of InSe/Sb heterostructures with different interlayer twist angle and other corresponding heterostructures. i Photoabsorption of the isolated InSe and Sb layers, and InSe/Sb heterostructures with different twist angles. The absorption spectrum in light green area refers to the interlayer photoexcitation. j The square of the transition dipole moment between valence and conduct band edges for the isolated InSe and Sb monolayers, and InSe/Sb heterostructures with different twist angles.

As exhibited in Fig. 2i, the photoexcitation threshold of the InSe/Sb heterostructures (around 0.6–1.0 eV) is obviously smaller than that of isolated 2D InSe and Sb layers (larger than 1.5 eV). That is, the intralayer photoexcitation cannot contribute to the first photoabsorption peak of InSe/Sb heterostructures. Simultaneously, the electronic band gap of these heterostructures is also in the range from ~0.6 to ~1.0 eV. Therefore, the first photoabsorption peak should derive from the direct interlayer photoexcitation at band edges of heterostructures. Specifically, for the interlayer photoexcitation at around Γ point, the square of the transition dipole moments (P2: see Fig. 2j) reaches up to ~300–500 Debye2, which has similar transition strength with the intralayer photoexcitation of isolated 2D InSe and Sb layers. Therefore, the direct interlayer bright photoexcitation can occur in InSe/Sb heterostructures. Note that, for InSe/Sb heterostructure with 0.0°, 10.9°, 30.0°, 49.1° and 60.0° twist angles, the first photoexcitation is bright excitation from VBM to CBM. For InSe/Sb heterostructure with 19.1° and 40.9° twist angles, the first bright excitation arises from the transition channel from VBM-4 to CBM, and VBM-3 to CBM, respectively. Therefore, the bandgap value is smaller than the first peak position for InSe/Sb heterostructure with 19.1° and 40.9° twist angles. For the calculation of transition dipole moment, we use the sum of transition between the first four valence bands and one conduction band for InSe/Sb heterostructure with 19.1° and 40.9° twist angles,

The interlayer twist can shift the peak position up to ~400 meV. In previous researches, the shifted range of the first photoluminescence peak is ~60 meV in twisted MoSe2/WS2 heterostructure,)16, ~90 meV in MoS2/WSe2 heterostructure39 and ~100 meV in WS2 bilayer38. Interesting, for InSe/Sb heterostructure, MoSe2/WS2 heterostructure and WS2 bilayer, although their shifted range of the first peak varies widely, the trend is consistent with each other. That is, for the highly symmetrical interlayer stacking heterostructure with twist angle near 0° or 60°, the energy of peak is small, while for the low symmetrical interlayer stacking heterostructures, the energy of peak is gradually increasing. the highly symmetrical interlayer stacking mode increases interlayer interaction and promotes the wavefunction coupling of band edge electronic states. This can be further confirmed by the transition probability between band edges (seeing Fig. 2j). For highly symmetrical interlayer stacking heterostructures (0° and 60°), the Γ-Γ interlayer photoexcitation possesses a larger transition probability (P2: å 500 Debye2) compared with that of other heterostructures (P2: 300–400 Debye2).

As presented in Fig. 3a, after forming heterojunction, the InSe and Sb sublayer all contribute electrons to the interface central region, which is different common phenomenon of charge transfer from one sublayer to the other40,41. Then, the stacked charge wavefunction distribution in the interface region can provide a buffer to increase the wavefunction overlap of interlayer transition channel, thereby in turn enhancing the transition probability of direct interlayer excitation.

a The charge density difference of InSe/Sb heterostructure with 0° twist angle. The yellow and cyan regions refer to distribution of positive and negative charges, respectively. b–g The top view of the sectional distribution of charge density difference in the interface central area for InSe/Sb heterostructure with other twist angle. The unit of the color scale is the e bohr−3.

The interlayer twist obviously changes the distribution of charge density difference. As shown in Fig. 3 and S9–S15, for the highly symmetrical interlayer stacking heterostructures with 0° and 60° twist angles, there accumulates more charges at interface central region compared with that of the low symmetrical modes. This further indicates that the interlayer excitation of the highly symmetrical stacked structures has a greater transition probability, consistent with the result of the transition dipole moment in Fig. 2j. Since the lattice parameter of InSe and Sb sublayer is similar to each other, for the low symmetrical modes, these heterostructures form a superlattice pattern (see Fig. 3). According to the different superlattice patterns of sectional charge distribution, the various interlayer twist angles indeed bring about different regulatory effects for electronic structure and interlayer photoexcitation properties.

Compared with the free electron-hole pair, one can obtain a more accurate photo-absorption spectrum by solving a Bethe-Salpeter equation (BSE) to include the electron-hole many-body interaction. Generally, the optical bandgaps are smaller than electronic bandgaps due to the excitonic effect. Since solving a BSE fully from first principles is incredibly expansive for such twisted heterostructures, we employ the time-dependent Hartree-Fock (TDHF) method to consider the exciton effect roughly. Since the changing trends of the electronic structure of InSe/Sb heterostructures with 0.0° to 30.0° twist angles are similar to that of 60° to 30.0° twist angles, we take InSe/Sb heterostructures with 0.0°, 10.9°, 19.1° and 30.0° twist angles as example to explore the effect of electron-hole many-body interaction. As shown in Fig. S16, the first photo-absorption peak position is generally smaller (around 0.3 eV) than that of the Random-Phase-Approximation (RPA) calculation with the free electron-hole pair. Therefore, the exciton effect is obvious for these 2D materials. Simultaneously, the first photo-absorption peak of these InSe/Sb heterostructures comes from the direct interlayer transition based on the inter-bands transition dipole moment. It is worth noting that the effect of the twisting angles on the photo-absorption range is still consistent with that of the RAP calculation. This should be derived from the fact that their exciton effects are similar to each other for the same heterostructures with different twisting angles.

After interlayer photoexcitation, the photogenerated electron and hole are localized in InSe and Sb sublayer, respectively. The lifetime of photogenerated carriers plays an essential role in various applications, such as optoelectronics, photovoltaics, and sensors. We perform the NAMD simulation by initiating the photogenerated electron at the conduction band edge of heterojunction (see Fig. 4b–h). After the photogenerated electron recombines with the hole located in the valance band edge, the time interval is defined as the lifetime of photogenerated carriers.

a The averaged photogenerated electron and hole nonradiative recombination dynamics in InSe/Sb heterojunctions with different twist angles. b–h Time-dependent evolution of the band edges and its adjacent electronic states of InSe/Sb heterojunctions with different twist angles. The blue and red lines denote the conduct and valence band edges, respectively. Fermi level is set to 0 eV. The temperature is set to 300 K. The insert values are the averaged photogenerated electron and hole nonradiative recombination lifetime.

For the InSe/Sb heterojunctions with different twist angles, we find that only less than 6% of photogenerated carriers recombine in 5 ns simulating time (see Fig. 4a). Although the precise lifetime is hard to obtain based on the current simulation period, we can estimate the timescale by fitting an exponential function: P(t) = exp(−t/τ). As presented in Fig. 4b–h, for different twist angle structures, the lifetime of photogenerated carriers is as high as 96.2 to 1181.9 ns. That is, the interlayer exciton can be adjusted over a wide range by interlayer twist.

Generally, the photogenerated carrier hopping probability between two electronic states inversely depends on the square of nonadiabatic coupling (NAC) based on Fermi’s golden rule. As exhibited in Fig. 5a, the largest value of NAC is less than 2.5 meV for all InSe/Sb heterojunctions with different twist angles. Such a small NAC value ensures the long-lived photogenerated carrier lifetimes. Moreover, compared with the highly symmetrical structures, the low symmetrical structures generally have a smaller NAC coefficient. To facilitate comparison, we present the averaged absolute value of NAC between the adjacent 10 band edge states in Fig. 5b–h. The InSe/Sb heterojunction with 60° (40°) twist angle possesses the largest (smallest) NAC coefficient between VBM and CBM electronic states, which is in agreement with the longest (shortest) lifetime of InSe/Sb heterojunctions. That is, the interlayer twist has a strong regulatory effect on the photogenerated carrier lifetime. Simultaneously, the average NAC between other neighboring states is larger than that of VBM and CBM. This also facilitates the other photogenerated carriers transferring into the VBM and CBM band edge states, forming the Γ-Γ interlayer exciton.

a The Time-dependent evolution of absolute value of NAC between VBM and CBM for InSe/Sb heterojunctions with different twist angles. b–h The averaged absolute value of NAC between the adjacent 10 band edge states for InSe/Sb heterojunctions with different twist angles. The temperature is set to 300 K. The inset value is the averaged absolute value of NAC between VBM and CBM. i Fourier transforms of the autocorrelation functions for the fluctuations of time evolution of bandgap between VBM and CBM of InSe/Sb heterojunctions with different twist angles. j Pure-dephasing functions between VBM and CBM of InSe/Sb heterojunctions with different twist angles.

The NAC element is dependent on the energy gap difference of hopping channel (\({\varepsilon }_{k}-{\varepsilon }_{j}\)), the electron-phonon coupling (\(\langle {\phi }_{j}|{\nabla }_{R}H|{\phi }_{k}\rangle\)) and nuclear velocity (ṘI) describing as follows:

Where H is the Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian, \({\phi }_{k}\), \({\phi }_{j}\), \({\varepsilon }_{j}\), \({\varepsilon }_{k}\) are the wave-functions and corresponding eigenvalues for j and k electronic states, respectively, and ṘI is velocity of the nuclei. For InSe/Sb heterojunctions with different twist angles, since the elements and the temperature are the same with each other, the difference in NAC should derive from the energy gap difference and electron-phonon coupling term.

As discussed above, the band gap of InSe/Sb heterojunctions can be gradually adjusted from 0.63 to 0.91 eV with the change of twist angle. That is, the small energy gap difference will increase the carrier hopping probability, which is consistent with the trend of photo-generated carrier lifetime with the change of twist angle.

For the electron-phonon coupling term, its strength can be reflected by the energy fluctuation of involved electronic states. As shown in Fig. 4b–h, the fluctuation of VBM with the time evolution is stronger than that of CBM. Hence, the vibration of Sb sublayer will play a more critical role in lifetime. To visualize the phonon modes dominating the fluctuation, the Fourier transforms (FT) of the autocorrelation functions are calculated to the time-dependent evolution of the band edges energy difference (Fig. 5i). For all InSe/Sb heterojunctions, the vibrational peaks are mainly concentrated around 50 and 200 cm−1, attributed to the interlayer breathing mode, A1g mode of InSe42 and Sb34 sublayer, respectively. Clearly, the phonon spectral density changes from high to low as the different twist angle structures from high to low symmetric stacking mode. This is also consistent with the trend of photogenerated carrier lifetime.

Moreover, the pure-dephasing time between initial and final electronic states, similar to Huang-Rhys factor and Frank-Condon factor, is also associated with the lifetime of nonradiative recombination. The fast loss of quantum coherence can suppress the hopping rate. As presented in Fig. 5j, for all InSe/Sb heterojunctions, the range of pure dephasing time is from 10 to 27 fs by Gaussian fitting, exp(−0.5(t/τ)). This is obviously smaller than that of MoS2/WS2 heterojunctions with different twist angles from 37 to 58 fs18. Hence, the small pure dephasing time also contributes to the long lifetime of photogenerated carriers for InSe/Sb heterojunctions.

For 2D materials, the excitonic effect is of significance due to the enhanced Coulomb interactions. Unfortunately, for InSe/Sb heterojunctions with various twist angles, it is not yet feasible because of excessive computational expense associated with NAMD involving thousands of electronic structure calculations. Although the single-particle picture cannot accurately obtain the lifetime of photogenerated electron and hole recombination, the change trends of lifetime should be reliable as the twist angle changes. In previous researches, Zhu et al. have studied the effect of twist angle on the photogenerated electron and hole recombination in MoS2/WS2 heterostructure and WS2 bilayer17 based on single-particle picture. They found that the larger bandgaps or smaller nonadiabatic couplings make the slower electron and hole recombination in twisted than high-symmetry structures. The trend of their results is consistent with the experiments19,38. Moreover, according to the similar electron-hole many-body interaction for InSe/Sb heterostructures with different twist angles in the above TDHF simulation, the exciton effect should have a similar effect on the photogenerated carrier lifetime of InSe/Sb heterostructures with different twist angles. Here, we mainly focus on the role of twist angle in regulating the interlayer exciton photo-absorption range and carrier lifetime. Although the single-particle picture cannot accurately obtain the lifetime of photogenerated electron and hole recombination, the change trends of lifetime should be reliable as the twist angle changes.

In addition to the InSe/Sb heterostructure, expanding to other 2D materials and exploring more possibilities for forming direct interlayer excitons would provide more candidate materials for the subsequent in-depth research and application. Given our study for InSe and Sb, we further consider similar materials of the same family, such as XY (X is In, Ga; Y is S, Se, Te) and other single-element 2D semiconductors, black phosphorus (P), arsenene (As), and bismuthine (Bi). As shown in Fig. S17, XY material’s band edge components mainly comprise interface chalcogen atomic layers. Simultaneously, as exhibited in Figs. S18 and S19, the conduction band edge of XY is composed of the pz orbital of chalcogen atomic layers. And the valence band edge of single-element 2D semiconductors is composed of px and pz orbitals; While the valence band edge of P is made up of pz. According to the band edge aligned with vacuum energy level (see Fig. S20), in addition to InSe/Sb heterostructure, it is possible to form 16 heterojunctions with type II band edge alignment, that is, InS/As, InS/P, InS/Sb, InSe/As, InSe/P, InTe/Bi, InTe/As, InTe/Sb, GaS/Bi, GaS/As, GaS/Sb, GaSe/Bi, GaSe/As, GaSe/Sb, GaTe/Bi, and GaTe/Sb heterojunctions. Therefore, they are potential heterojunctions with direct interlayer photoexcitation.

Combining fist-principles and nonadiabatic molecular dynamics simulations, we find that the InSe/Sb heterojunction can form interlayer excitons in one-step interlayer photoexcitation, and the photo-response range and lifetime can be significantly modulated by interlayer twist. The interlayer twist can periodically regulate the interlayer coupling. Then, the band edge states, contributed by interface atoms, can be directly affected by different twist angles. This induces the large range of regulation for the interlayer excitation peak and photogenerated carrier lifetime. This study enriches the understanding and engineering the interlayer exciton in artificial 2D vdW heterostructure materials.

Methods

Density functional theory calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) was conducted within the projected-augmented wave (PAW) potentials43 in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)44,45. The electron exchange and correlation functionals were described by Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof generalized gradient approximation (PBE-GGA)46. The energy cutoff was set to 500 eV. A Γ-centered 4 × 4 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid was adopted for the heterostructure with different twist angle. vdW interactions were described by Grimme et al. (DFT-D3)47. Dipole correction was considered to cancel the errors of total energy, atomic force and electrostatic potential caused by periodic boundary condition48.

Non-adiabatic molecular dynamics simulation

The dynamics of photogenerated carriers were obtained by the ab initio NAMD within time-domain DFT using Hefei-NAMD code49. For the optimized heterostructures, we heated to 300 K for 2 ps based on the repeated velocity rescaling approach, and obtaining a 10 ps microcanonical trajectory with a time step of 1 fs by ab initio molecular dynamics (ABMD)50. By selecting 100 different initial geometries from the first 2 ps, we sampled 2 × 104 trajectories for the next 8 ps. The decoherence induced surface hopping method was employed to provide a probability for hopping between interacting states51.

Exciton effect

For optical properties, the energy-dependent dielectric functions were used to investigate the optical absorption of isolate InSe, Sb layer, and InSe/Sb heterostructure with different twist angle52,53. Moreover, we employed the time-dependent Hartree-Fock (TDHF) method to consider the exciton effect roughly. The TDHF calculation by solving the Casida equation, is very similar to Bethe-Salpeter equation (BSE) but differs in the way the screening of the Coulomb potential is approximated. The TDHF method employs the exchange-correlation kernel fxc, but BSE needs the W(ω → 0) from a preceding GW calculation.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The DFT calculations were performed using the VASP code, which is a licensed software package. The detailed information related to the VASP code is available at http://wwww.vasp.at. The dynamics of photogenerated carriers were performed using Hefei-NAMD code. The detailed information related to the Hefei-NAMD code is available at http://staff.ustc.edu.cn/~zhaojin/code/.

References

Su, T., Shao, Q., Qin, Z., Guo, Z. & Wu, Z. Role of interfaces in two-dimensional photocatalyst for water splitting. ACS Catal. 8, 2253–2276 (2018).

Liu, Y., Duan, X., Huang, Y. & Duan, X. Two-dimensional transistors beyond graphene and Tmdcs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 6388–6409 (2018).

Frisenda, R. et al. Recent progress in the assembly of nanodevices and van der Waals heterostructures by deterministic placement of 2d materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 53–68 (2018).

Zhang, H., Cheng, H. M. & Ye, P. 2d nanomaterials: beyond graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 6009–6012 (2018).

Pham, P. V. et al. 2d heterostructures for ubiquitous electronics and optoelectronics: principles, opportunities, and challenges. Chem. Rev. 122, 6514–6613 (2022).

Khelifa, R. et al. Coupling interlayer excitons to whispering gallery modes in van der Waals heterostructures. Nano Lett. 20, 6155–6161 (2020).

Miller, B. et al. Long-lived direct and indirect interlayer excitons in van der Waals heterostructures. Nano Lett. 17, 5229–5237 (2017).

Eisenstein, J. P. & MacDonald, A. H. Bose–Einstein condensation of excitons in bilayer electron systems. Nature 32, 691–694 (2004).

Fogler, M. M., Butov, L. V. & Novoselov, K. S. High-temperature superfluidity with indirect excitons in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 5, 4555 (2014).

Li, Y. M. et al. Light-induced exciton spin hall effect in van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 166804 (2015).

Liu, Y., Huang, Y. & Duan, X. Van Der Waals integration before and beyond two-dimensional materials. Nature 567, 323–333 (2019).

Xie, B., Peng, R., Zhang, S. & Liu, J. Alternating twisted multilayer graphene: generic partition rules, double flat bands, and orbital magnetoelectric effect. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 110 (2022).

Jin, C. et al. Observation of moire excitons in Wse2/Ws2 heterostructure superlattices. Nature 567, 76–80 (2019).

Kunstmann, J. et al. Momentum-space indirect interlayer excitons in transition-metal dichalcogenide van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Phys. 14, 801–805 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Evidence of high-temperature exciton condensation in two-dimensional atomic double layers. Nature 574, 76–80 (2019).

Alexeev, E. M. et al. Resonantly hybridized excitons in moire superlattices in van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 567, 81–86 (2019).

Zhu, Y., Prezhdo, O. V., Long, R. & Fang, W.-H. Twist angle-dependent intervalley charge carrier transfer and recombination in Bilayer Ws2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 22826–22835 (2023).

Zhu, Y., Fang, W.-H., Rubio, A., Long, R. & Prezhdo, O. V. The twist angle has weak influence on charge separation and strong influence on recombination in the Mos2/Ws2 bilayer: ab initio quantum dynamics. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 8324–8333 (2022).

Choi, J. et al. Twist angle-dependent interlayer exciton lifetimes in van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 047401 (2021).

Huang, D., Choi, J., Shih, C.-K. & Li, X. Excitons in semiconductor moiré superlattices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 227–238 (2022).

Yu, H., Wang, Y., Tong, Q., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Anomalous light cones and valley optical selection rules of interlayer excitons in twisted heterobilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 187002 (2015).

Barré, E. et al. Optical absorption of interlayer excitons in transition-metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. Science 376, 406–410 (2022).

Policht, V. R. et al. Time-domain observation of interlayer exciton formation and thermalization in a mose2/Wse2 heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 14, 7273 (2023).

Hong, X. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer in atomically thin Mos(2)/Ws(2) heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 682–686 (2014).

Yuan, L. et al. Twist-angle-dependent interlayer exciton diffusion in Ws2-Wse2 heterobilayers. Nat. Mater. 19, 617–623 (2020).

Zheng, Q. et al. Phonon-assisted ultrafast charge transfer at van der Waals heterostructure interface. Nano Lett. 17, 6435–6442 (2017).

Merkl, P. et al. Ultrafast transition between exciton phases in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 18, 691–696 (2019).

Chen, H. et al. Ultrafast formation of interlayer hot excitons in atomically thin Mos2/Ws2 heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 7, 12512 (2016).

Feng, W., Zheng, W., Cao, W. & Hu, P. Back gated multilayer inse transistors with enhanced carrier mobilities via the suppression of carrier scattering from a dielectric interface. Adv. Mater. 26, 6587–6593 (2014).

Bandurin, D. A. et al. High electron mobility, quantum hall effect and anomalous optical response in atomically thin inse. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 223–227 (2017).

Ares, P. et al. Mechanical isolation of highly stable antimonene under ambient conditions. Adv. Mater. 28, 6332–6336 (2016).

Gibaja, C. et al. Few-layer antimonene by liquid-phase exfoliation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14345–14349 (2016).

Tao, W. et al. Antimonene quantum dots: synthesis and application as near-infrared photothermal agents for effective cancer therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 11896–11900 (2017).

Ji, J. et al. Two-dimensional antimonene single crystals grown by van der Waals epitaxy. Nat. Commun. 7, 13352 (2016).

Xue, T. et al. Ultrasensitive detection of mirna with an antimonene-based surface plasmon resonance sensor. Nat. Commun. 10, 28 (2019).

Ares, P., Palacios, J. J., Abellan, G., Gomez-Herrero, J. & Zamora, F. Recent progress on antimonene: a new bidimensional material. Adv. Mater. 30, 1703771 (2017).

Zhang, K. et al. Spectroscopic signatures of interlayer coupling in Janus Mosse/Mos2 heterostructures. ACS Nano 15, 14394–14403 (2021).

Yan, W. et al. Probing angle-dependent interlayer coupling in twisted bilayer Ws2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 30684–30688 (2019).

Kim, J. et al. Anomalous optical excitations from arrays of whirlpooled lattice distortions in moiré superlattices. Nat. Mater. 21, 890–895 (2022).

Niu, X., Li, Y., Shu, H., Yao, X. & Wang, J. Efficient carrier separation in graphitic zinc oxide and blue phosphorus van der Waals heterostructure. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 3648–3653 (2017).

Niu, X., Bai, X., Zhou, Z. & Wang, J. Rational design and characterization of direct Z-scheme photocatalyst for overall water splitting from excited state dynamics simulations. ACS Catal. 10, 1976–1983 (2020).

Ahmad, W. et al. Strong interlayer transition in few‐layer Inse/Pdse2 van der Waals heterostructure for near‐infrared photodetection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2104143 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical Gga-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Bengtsson, L. Dipole correction for surface supercell calculations. Phys. Rev. B 59, 12301–12304 (1998).

Zheng, Q. et al. Ab initio nonadiabatic molecular dynamics investigations on the excited carriers in condensed matter systems. WIRES Comput. Mol. Sci. 9, e1411 (2019).

Niu, X. et al. Highly efficient photogenerated electron transfer at a black phosphorus/indium selenide heterostructure interface from ultrafast. Dyn. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 1864–1870 (2019).

Jaeger, H. M., Fischer, S. & Prezhdo, O. V. Decoherence-induced surface hopping. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 22A545 (2012).

Lalitha, S. et al. Electronic structure, structural and optical properties of thermally evaporated CdTe thin films. Phys. B 387, 227–238 (2007).

Gajdoš, M., Hummer, K., Kresse, G., Furthmüller, J. & Bechstedt, F. Linear optical properties in the projector-augmented wave methodology. Phys. Rev. B 73, 045112 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2022M711691), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22473060, 12104130), Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi province (Grant No. 20210302123336), Six talent peaks project in Jiangsu Province (Grant No. XCL-104), the open research fund of Key Laboratory of Quantum Materials and Devices (Southeast University), Ministry of Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.N. and A.S. conceived the project. A.S., R.G. and Z.N. carried out DFT and NAMD calculations. W.Z., X.Z., and S.W. carried out twist model constructing and DFT calculations. A.S., X.N., J.L. and B.W. co-wrote the paper with all authors contributing to the discussion and preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, A., Guan, R., Lv, J. et al. The interlayer twist effectively regulates interlayer excitons in InSe/Sb van der Waals heterostructure. npj Comput Mater 10, 190 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01384-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01384-6