Abstract

Chalcogenide phase-change materials (PCMs) are showing versatile possibilities in cutting-edge applications, including non-volatile memory, neuromorphic computing, and nano-photonics. However, for embedded phase-change memory applications, conventional PCMs suffer from insufficient thermal stability because of their relatively low crystallization temperatures (Tx). Although doping with additional alloying elements could improve the amorphous stability, it also increases the tendency towards compositional partitioning and phase separation. Recently, a two-dimensional (2D) layered compound CrGeTe3 (CrGT) was developed as a PCM, showing a high Tx ~ 276 °C with an inverse change in resistive-switching character upon phase transition. Here, we report a high-throughput materials screening for 2D layered phase-change chalcogenides. We aim to clarify whether the high Tx and the inverse electrical resistance contrast are intrinsic features of 2D PCMs. In total, twenty-five 2D chalcogenides with CrGT trilayer structures have been identified from a large database. We then focused on selected layered tellurides by performing thorough ab initio simulations and experimental investigations and confirming that their amorphous phase indeed has a much higher Tx than conventional PCMs. We attribute this enhanced amorphous stability to the structurally complex nuclei required to render crystallization possible. Overall, we regard InGeTe3 as a balanced 2D PCM with both high thermal stability and large electrical contrast for embedded memory applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chalcogenide phase-change material (PCM) is one of the leading candidates for non-volatile memory1,2,3, neuromorphic computing4,5,6, reconfigurable nanophotonics7,8,9,10 as well as spaceborne applications11,12,13. The key working principle is to utilize the large changes in electric or optical properties upon phase transition between amorphous and crystalline PCM to encode digital information1. The flagship PCMs can be found in the Ge–Sb–Te ternary diagram with three major materials families, namely, the pseudo-binary (GeTe)m(Sb2Te3)n alloys14,15,16,17 (GST), Sb–Te binary alloys18,19,20,21 and Sb22,23,24,25,26. The crystallization temperature Tx of these materials is below 190 °C27,28,29, forming three-dimensional (3D) crystalline structures with octahedral bonding patterns. Additional impurity atoms, such as C, N, Ag, and In, are typically incorporated to improve the thermal stability of the amorphous phase of these PCMs29,30,31,32,33. In particular, it is necessary to do so for embedded memories34, which operate at elevated temperatures (above 260 °C35). Notably, by alloying PCMs with certain transition metal elements, e.g., Sc36,37,38,39,40, Y41,42,43, or Ta44, both the amorphous stability at low temperatures and the crystallization speed at elevated temperatures can be improved simultaneously. Despite that embedded PCM products based on heavy alloying of C or Ge into stoichiometric Ge–Sb–Te alloys were recently released45,46, new PCMs with intrinsically high Tx are being constantly pursued, as non-stoichiometric impurities may also increase the possibility of phase separation upon extensive cycling.

Recently, a two-dimensional (2D) layered van der Waals (vdW) material, CrGeTe3 (“CrGT” in the following), was developed as a promising PCM47,48,49,50,51,52. Crystalline CrGT is an intrinsic ferromagnetic semiconductor53,54,55, which is comprised of trilayer slabs connected by vdW forces. Regarding the amorphous phase, this stoichiometric alloy has a relatively high Tx ~ 276 °C in the absence of excess impurities. In nanoscale electronic devices, CrGT can be reversibly switched between its crystalline and amorphous phase using short voltage pulses, and the resistance contrast window remains robust over nearly a million cycles48. In stark contrast with conventional PCMs, CrGT shows an inverse resistance contrast upon phase transition, with the amorphous phase being the low-resistance state and the crystalline phase being the high-resistance state47. This inversed resistance contrast stems from the difference in spin configurations between the two phases, i.e., crystalline CrGT shows a sizable band gap, but the band gap is closed in amorphous CrGT, and the highly disordered structure also induces a spin glass behavior52. It remains elusive whether the high Tx and inverse resistance contrast are special characteristics of CrGT, or are general features of 2D PCMs. In this work, we perform thorough materials screening over materials databases to address this question and find promising candidates for embedded memory applications.

Results and discussion

Materials screening for 2D layered PCMs

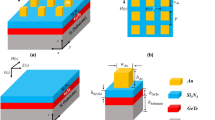

Figure 1a shows the trilayer atomic slab of crystalline CrGT: in the center, two Cr atoms are bonded with six Te atoms, forming edge-shared Cr[Te6] octahedral motifs, and in the outer two layers, two Ge atoms form intergrown Ge[GeTe3] tetrahedral motifs through the homopolar Ge–Ge bonds, as highlighted by the semi-transparent red and blue polyhedra. As optimized by spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional56 and semi-empirical van der Waals corrections57 (see more details in the Methods section), the Cr–Te, Ge–Te, and Ge–Ge bonds are calculated as 2.76, 2.62, and 2.43 Å, respectively. The size of vdW gaps between these trilayer slabs is 3.38 Å, and the interatomic distance between two Te atoms across the gap is 4.02 Å, indicating a clear 2D feature. However, amorphous CrGT forms a randomly bonded 3D disordered network, indicating a dimensional transition of the chemical bonding pattern during crystallization58,59,60. Given the structural complexity of the trilayer structure, forming a sizable seed of such layered structures for nucleation can be difficult.

a The trilayer slab of CrGT with Cr-centered octahedrons and Ge-centered tetrahedrons being highlighted. The Cr, Ge, and Te atoms are rendered with red, blue, and green spheres, respectively. b The high-throughput materials screening scheme employed in this work. c–e The three typical crystal structures that are comprised of trilayer slabs in different stacking order.

Previous studies focused on searching and designing 3D alloys61,62,63,64 that are similar to GST, but screening for 2D alloys with complex bonding patterns as CrGT could, in principle, help identify PCMs with high nucleation barriers. We carried out a series of screening steps over the inorganic crystal structure database (ICSD release 2023.2), which contains 291,382 inorganic structures65. On the ICSD website, we set the chemical ratio as 1:1:3 and searched compounds containing chalcogens (S, Se, or Te). In total, 568 structural files were downloaded from ICSD for further analyses using the atomic simulation environment (ASE) package66. By restricting chalcogens as the major element, we reduced the number to 397 ABCh3 compounds. Next, we used the rank determination algorithm (RDA) method67 to single out 101 layer-structured materials and then to make a comparison with the CrGT trilayer according to the space group of \(P\overline{3}m1\). After removing the duplicated structures that are chemically identical but exhibit minor differences in lattice parameters, we identified 25 layered chalcogenides, including CrGT, as listed in Table 1.

For all these layered ABCh3 alloys, the A site is occupied by a metallic element, either by a transition metal, including Sc, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn, Pd and Cd, or by a main group metal, including Mg, Al, In, Sn, and Bi. However, the B site is instead taken by a semiconducting element, namely, P for sulfides and selenides, and Si or Ge for tellurides. Despite the similar atomic arrangement within each trilayer atomic slab, the identified layered ABCh3 compounds can be grouped into three families according to the stacking order of these slabs. As shown in Fig. 1c, CrGT forms a hexagonal unit cell with three atomic slabs being stacked in the ABC sequence (containing 30 atoms). Eleven other alloys, e.g., SnPS3, CdPSe3, InGeTe3, etc., form this structure. Their primitive cell is rhombohedral (r−), and the lattice vectors are highlighted in Fig. 1c (containing 10 atoms). For AlSiTe3 and InSiTe3, the hexagonal (h−) primitive cell contains only one trilayer slab (containing 10 atoms), and the stacking sequence can be viewed as AA (Fig. 1d). The third materials class also has only one trilayer slab in the primitive cell, but the overall structure forms a monoclinic (m−) phase with β being ~108°, resulting in a stacking sequence of AA* (containing 20 atoms). Most AA* compounds are sulfides with two exceptional cases, i.e., CrPSe3 and NiPSe3. It is also noted that CdPS3 and SnPS3 can form both ABC (lower in energy) and AA* stacking. The DFT-optimized lattice parameters of these layered ABCh3 alloys are included in Table 1.

As shown in Fig. S1, the calculated formation energy of these alloys ranges from −808 to −155 meV/atom. The lighter the constituting elements, the higher the formation energy (absolute value). Spin-polarized DFT calculations show that when the A site is taken by V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Ni, or Co, the system becomes magnetic. As listed in Table 1, 3 Cr-based alloys are ferromagnetic (FM), 8 alloys are antiferromagnetic (AFM), and 14 alloys are non-magnetic (NM). Almost all NM alloys show a sizable band gap, except for PdPS3, which is a metal. The band structure of all 25 alloys in their primitive cell are plotted in Fig. 2 (tellurides) and Fig. S2 (sulfides and selenides). For magnetic alloys, both spin-up (red) and spin-down (blue) channels are plotted. Although Sc is also a 3d transition metal, it forms strong chemical bonds with Te atoms, leaving no unpaired d electrons. Hence, ScSiTe3 is non-magnetic (Fig. 2c). It is also interesting to note that BiSiTe3 is calculated to be a direct gap semiconductor (0.68 eV at Z point), see Fig. 2d. The rest of the semiconducting alloys are indirect gap semiconductors with a gap size ranging from 0.06 to 2.75 eV (see Table 1). Note that these calculations were done at PBE level.

a rhombohedral CrGeTe3, b rhombohedral CrSiTe3, c rhombohedral ScSiTe3, d rhombohedral BiSiTe3, e rhombohedral InGeTe3, f hexagonal InSiTe3, and g hexagonal AlSiTe3. The bands are plotted in black for non-magnetic compounds, and the bands are plotted in red (spin up) and blue (spin down) for magnetic compounds.

For phase-change memory applications, thin films with a thickness from tens to hundreds of nm are typically needed, and the crystallization process must be rapid, occurring in hundreds of ns or less in nanoscale devices. All the identified sulfides and selenides contain the very light element phosphorus (P), making the phase transition, particularly crystallization, difficult to achieve. Also, given the highly reactive nature of P, it is exceedingly challenging to grow thin films that contain high concentrations of this element. Hence, we focus on the identified tellurides in the following, namely, CrSiTe3, InGeTe3, AlSiTe3, ScSiTe3, InSiTe3, and BiSiTe3, and evaluate whether they are also suitable candidates for phase-change memory applications like CrGT.

AIMD simulations of amorphous ABTe3

We carried out DFT-based ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations to generate melt-quenched amorphous (a−) models of telluride alloys (see more details in the Methods section). For instance, 36 Cr, 36 Si, and 108 Te atoms were included in a cubic box in a random fashion, and the model was heated at 1200 K for 30 ps to remove possible crystalline order. Then the model was gradually quenched down to 300 K at a cooling rate of 12.5 K/ps to obtain a-CrSiTe3. The amorphous model was further annealed at 300 K over 30 ps for structural data collection. The volume of the cubic cell was adjusted to remove internal stress, resulting in a lattice edge of 17.04 Å. The obtained atomic structure of a-CrSiTe3 is shown in Fig. 3a. The same process was performed for the remaining five alloys, and the corresponding amorphous structures are shown in Fig. 3a. The obtained lattice edges are 17.60, 18.00, 17.96, 17.86, and 17.77 Å for a-ScSiTe3, a-BiSiTe3, a-InGeTe3, a-InSiTe3, and a-AlSiTe3, respectively. As shown in Fig. S3, all six amorphous models show a low stress value below 3 kbar at 300 K. The structural details of a-CrGT can be found in our previous work52.

a The amorphous models generated by the melt-quench simulation scheme for the tellurides CrSiTe3, ScSiTe3, BiSiTe3, InGeTe3, InSiTe3, and AlSiTe3. The representing colors for different atoms are marked in the figure. b The radial distribution function (RDF), c angular distribution function (ADF), and d coordination number distribution for the respective compounds. The data are collected from the annealing trajectories at 300 K for 30 ps.

Figure 3b shows the radial distribution function (RDF) curves of the six amorphous models. Their first primary peak is found between 2.62 and 3.08 Å, indicating the typical length of chemical bonds. The splitting of this primary peak, observed in a-ScSiTe3, a-BiSiTe3, and a-InSiTe3, stems from the relatively large difference in bond length between Sc–Te/Bi–Te/In–Te and Si–Te bonds. A secondary peak observed around 4.2 Å and a third one around 6.2 Å indicate that the amorphous models have a certain medium-range order. To carry out further local arrangement analysis, we set the cutoffs for interatomic distance to be smaller than 3.5 Å, and determined the element-specific cutoffs following the chemical bonding analysis scheme developed for amorphous PCMs68,69,70 (see more details in Fig. S4). The angular distribution function (ADF) and the distribution of coordination numbers (CN) of the six amorphous models are shown in Fig. 3c, d. For a-CrSiTe3 and a-ScSiTe3, the distribution profiles of ADF and CN are overall similar. Both Cr and Sc atoms show a major ADF peak at ~90° and are mostly 5- and 6-fold coordinated with Te atoms. However, for Si atoms, the ADF peak is found at ~109.5°, and the vast majority of Si atoms are 4-fold coordinated with Te atoms. The local structural pattern in a-BiSiTe3 is similar to the above two amorphous models, except that Bi atoms have fewer neighboring atoms. As regards InGeTe3, Ge atoms form mostly octahedral bonds with Te atoms (Fig. S5) with a major ADF peak at ~94°.

By calculating the bond order parameter71 \(q=1-3/8{\sum }_{x > y}(1/3+\cos {\theta }_{{xmy}})\), where \({\theta }_{{xmy}}\) represents the bond angle of the center atom m with its two neighboring atoms x and y, we confirm that the vast majority of Cr/Sc/Bi form defective octahedral motifs, whereas Si atoms form tetrahedral motifs in these amorphous models (Fig. S6). Regarding a-InGeTe3 and a-InSiTe3, In atoms form both tetrahedral and defective octahedral motifs, but the vast majority of Ge (Si) atoms form defective octahedral (tetrahedral) motifs, respectively. However, for a-AlSiTe3, both Al and Si atoms form tetrahedral bonds with Te atoms, showing major ADF peaks at ~109.5°. The structural dissimilarity of Al atoms in the amorphous and crystalline phases should lead to a higher barrier for nucleation, as compared to other ABTe3 alloys. In addition, the shorter but stronger Al–Te and Si–Te bonds may make atomic diffusions more difficult, leading to a sluggish growth process. Therefore, we regard AlSiTe3 to have the highest Tx among the identified tellurides.

Prior to the electronic structure analysis, all the amorphous models were quenched down from 300 K to 0 K in 24 ps and were further relaxed at 0 K. Figure 4 shows the calculated density of states (DOS) for both crystalline and amorphous phases. Similar to CrGT, the crystalline phase of CrSiTe3 is a FM semiconductor with a small band gap 0.47 eV, but its amorphous phase is a magnetic metal, as shown in Fig. 4a. Hence, CrSiTe3 should undergo a metal-to-semiconductor transition upon crystallization, which should result in an increase in electrical resistance, consistent with CrGT. However, the other five amorphous models are all non-magnetic semiconductors, showing a narrow band gap of 0.33, 0.31, 0.32, 0.28, and 0.47 eV for a-ScSiTe3, a-BiSiTe3, a-InGeTe3, a-InSiTe3, and a-AlSiTe3, respectively. Some mid-gap states are observed in a-InSiTe3. It is noted that the PBE functional typically underestimates the size of band gaps. Nevertheless, our DFT calculations predict the presence of a band gap in both the crystalline and the amorphous phase of these five alloys, indicating that their crystallization is not accompanied by a metal-to-semiconductor transition. Given the similar narrow-gap features in both phases but the highly disordered nature of the amorphous phase (due to which the carrier mobility could be largely reduced), these five alloys should undergo a conventional change in electrical resistance upon the phase transition.

Experimental verification

To verify our predictions, we carried out experimental investigations on some of these alloys. We selected CrSiTe3 and InGeTe3 to clarify the trend in resistance contrast, as these two alloys differ from CrGeTe3 by only one element, but they showed a major difference in the DOS profile. Then we also synthesized AlSiTe3 thin film to evaluate the enhancement in the amorphous stability, as this alloy showed the biggest change in local geometry between the amorphous and crystalline phases. Hence, this amorphous alloy should have the best thermal stability.

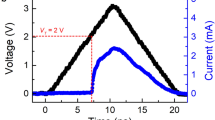

We deposited CrSiTe3 thin films of ~200 nm onto SiO2/Si substrates via magnetron co-sputtering. We heated the as-deposited thin film to 350 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min and removed the heating source so that the temperature gradually dropped back to room temperature in about 20 min. Figure 5a displays the recorded sheet resistance during this heating and cooling loop, and a clear drop in sheet resistance occurred at ~300 °C. We repeated the heating experiments on two additional thin films with the target temperature being set as 290 °C and 310 °C and performed X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments on these three thin film samples. No obvious peak could be found for the thin film annealed at 290 °C, corresponding to the amorphous feature. For the other two samples, clear diffraction peaks at (003), (006), and (0012) are observed, confirming that CrSiTe3 thin films were crystallized. Hence, CrSiTe3 undergoes a crystallization process that is accompanied by an increase in sheet resistance from 9.4 × 104 to 3.6 × 105 Ω/γ Although the crystallization temperature of CrSiTe3 is higher than that of CrGT, the former alloy shows a smaller resistance contrast window than the latter. We carried the Hall effect measurements using a physical property measurement system (PPMS) setup and obtained a carrier concentration of 1.9 × 1020 cm−3 and a carrier mobility of 0.028 cm2 V−1 s−1 in the as-deposited a-CrSiTe3 thin film. Upon crystallization, the carrier concentration was reduced to 2.2 × 1019 cm−3, but the carrier mobility remained nearly unchanged at 0.027 cm2 V−1 s−1. Hence, this observation of reversed resistance contrast in CrSiTe3 is consistent with our DOS analysis.

Then we measured electrical resistance and performed structural characterization measurements on InGeTe3 and AlSiTe3 thin films, as shown in Fig. 5b, c. For InGeTe3, crystallization took place at ~260 °C, and the change in resistance follows the conventional pathway. Note that the contrast window upon amorphous to crystalline phase transition is over 5 orders of magnitude, much larger than that of CrGT, CrSiTe3, and GST alloys. The measured carrier concentration and mobility of the crystallized InGeTe3 thin film were 1.9 × 1018 cm−3 and 76 cm2 V−1 s−1, respectively, but it is not feasible to conduct the same measurement for the amorphous thin film, as its high resistance (~1010 Ω/γ) exceeded the measurement range of the PPMS setup. Given the highly resistive nature of amorphous InGeTe3, it is unlikely to have a high mobility value of the order ~102 cm2 V−1 s−1, comparable to its crystalline counterpart. Hence, the change in carrier mobility should be regarded as a major contributor to the large resistance window over 5 orders of magnitude. Although the DOS calculation showed a narrower band gap in amorphous InGeTe3 than its crystalline counterpart, we are unable to draw a conclusion on the difference in carrier concentration, owing to the intrinsic limitation of DFT in determining gap size, in particular, for highly disordered systems. Therefore, we attribute the large resistance window in InGeTe3 thin film to the potential changes in both carrier concentration and mobility upon crystallization. As regards AlSiTe3, no sign of crystallization can be observed upon heating up to 450 °C, above which the thin films would evaporate. The high thermal stability of AlSiTe3 can be attributed to the structural dissimilarity between its amorphous and crystalline phases. More specifically, almost all the Al atoms need to change from tetrahedral to octahedral coordination to form crystalline seeds, but Al atoms tend to form strong chemical bonds that are difficult to break.

To confirm that both the CrSiTe3 and InGeTe3 thin films indeed crystallized into the 2D layered structure, we performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) experiments. Figure 6 shows the high-resolution (HR-) TEM images of crystal grains viewed along the [100] and [001] direction for both alloys. Along the [100] direction, clear layered features were observed with the lattice spacing corresponding to three trilayer slabs measured as 20.7 / 21.3 Å and the size of vdW gaps as 3.4/3.3 Å for r-CrSiTe3 and r-InGeTe3, respectively. These results are in good agreement with our DFT results, i.e., 20.66/21.24 Å and 3.42/3.29 Å for r-CrSiTe3 and r-InGeTe3, respectively.

Comparisons between 2D PCM and 3D PCM

Before closing, we make a comparison between the newly identified 2D PCMs and conventional 3D PCMs. As sketched in Fig. 7, conventional 3D PCMs, such as GST alloys, undergo a structural transition from amorphous to cubic rocksalt phase (one sublattice is taken by Te atoms, and the other one is occupied by Ge, Sb, and atomic vacancies in a random fashion)14,15,16,17 at low annealing temperatures ~150 °C or upon rapid electrical programming in nanoscale devices72. Further thermal annealing drives a structural transition from the 3D-like cubic phase into the 2D-like trigonal phase at Tc-t ~ 250 °C and above, but this transition consists of a slow and continuous vacancy-ordering process within the crystalline phase73,74,75,76,77. Hence, nucleation into the intermediate cubic phase is the key to the practical use of GST alloys, where the formation of cubic seeds only requires octahedral bonds. However, forming a sizable seed of 2D ABCh3 PCMs is rather difficult since it requires the arrangement of both tetrahedral and octahedral bonds in the trilayer structure pattern. Such complex seeds present a higher nucleation barrier, leading to higher Tx. Taking the In–Ge–Te system as an example, the 1:1:2 composition is known to form a rocksalt structure78,79,80, but even with additional doping, at 200 °C its amorphous state cannot survive over a few hours in devices78. For the 1:1:3 composition, the intrinsic Tx is already high, reaching ~260 °C, and its amorphous stability can be further enhanced via a small fraction of elemental substitution of In by Al, as Al atoms form much stronger chemical bonds with Te atoms. Such a substitution scheme, which keeps the overall composition ratio 1:1:3, could be better than non-stoichiometric doping in avoiding phase separation.

In summary, a high-throughput materials screening strategy was executed for 2D layered phase-change materials. In total, 25 ABCh3 compounds with the same trilayer structure as CrGT were identified from the ICSD, and six tellurides, namely, InGeTe3, CrSiTe3, InSiTe3, AlSiTe3, BiSiTe3, and ScSiTe3, were selected for thorough investigation using ab initio simulations. By performing structural and electrical measurements, we verified our DFT predictions that InGeTe3 displays a conventional reduction in electrical resistance by 5 orders of magnitude upon crystallization, while CrSiTe3 is characterized by an inverse resistance contrast due to the spin-polarized nature of Cr atoms. Both thin film alloys showed good amorphous stability, with a high crystallization temperature ~260 °C for InGeTe3 and ~300 °C in CrSiTe3. Such behavior is attributed to the high nucleation barrier caused by the required formation of complex crystalline seeds. The nucleation barrier is further enlarged in AlSiTe3 due to the high level of structural dissimilarity between the Al-centered motifs in its amorphous and crystalline phases; no sign of crystallization is observed upon heating up to 450 °C. Hence, we project Al-substituted InGeTe3 to be a promising candidate for embedded memories due to its high thermal stability and large resistance contrast window. To gain a further atomistic understanding of the crystallization kinetics of ABCh3 alloys, machine-learning interatomic potentials should be developed. Such method has largely reduced the computational costs of phase transition simulations in conventional PCMs81,82,83,84,85,86,87, and has even enabled device-scale atomistic simulations of Ge–Sb–Te alloys84. Overall, our work opens up a new avenue towards the design and exploitation of low-dimensional materials for phase-change applications.

Methods

Materials screening and first principal calculations

ASE package66 is used for composition and structure (by Rank Determination Algorithm method67) analysis for materials screening. The VASP code88 was employed for DFT calculations, including structural relaxation and self-consistent calculations for both crystalline and amorphous models. The projector augmented wave (PAW) method89 and the PBE functional56 were used with an energy cutoff of 450 eV. The k-point mesh for rhombohedral, monoclinic, hexagonal, and amorphous models were 5 × 5 × 5, 6 × 3 × 5, 5 × 5 × 5, and gamma-only, respectively. To generate amorphous models, AIMD simulations using the CP2K package90 were employed. The Goedecker pseudopotentials91, and the PBE functional were employed. The Kohn–Sham orbitals were expanded in a Gaussian-type basis set with double-/triple-ζ polarization quality, whereas the charge density was expanded in plane waves, with a cutoff of 300 Ry. The AIMD calculations were performed using the second-generation Car–Parrinello scheme92 in the canonical (NVT) ensemble with a time step of 2 fs. The spin polarization was achieved using α and β orbitals without any spin restriction during the AIMD simulation. The semi-empirical DFT-D3 van der Waals corrections57 were included in all the calculations. The chemical bonding analyses were performed using LOBSTER93. The atomic structures were visualized using OVITO94.

Experimental characterization

Thin films of CrGeTe3, CrSiTe3, InGeTe3, and AlSiTe3 were deposited using the radio frequency (RF) magnetron co-sputtering technique onto a SiO2/Si substrate at room temperature with the thin film thickness of 200 nm. The thin film deposition was performed employing Cr (99.95% pure), Ge (99.9999% pure), Te (99.99% pure), Si (99.999% pure), In (99.995% pure), and Al (99.999% pure) targets in high-vacuum ∼2 × 10−5 Pa with the deposition rate of 6.8 nm min−1. Electrical measurements were performed using a Keithley 2636B source meter and an Instec mK200 hot stage instrument. The electrical characterization of CrSiTe3, InGeTe3, and AlSiTe3 thin films was carried out using a two-probe method utilizing the tungsten electrode. The heating rate of 10 °C/min was employed to investigate the temperature dependence of thin film resistance under an Ar atmosphere. The Hall effect measurement was conducted at room temperature using a physical property measurement system (PPMS) instrument (Quantum Design DynaCool, M91). The XRD measurements were carried out using the Cu Kα X-ray source (Bruker D8 ADVANCE). The TEM experiments were performed using Talos-F200X operated at 200 kV.

Data availability

Data supporting this work will be available at https://caid.xjtu.edu.cn/info/1003/1108.htm upon journal publication.

Code availability

The VASP and CP2K software packages are commercially available at https://www.vasp.at and open-source at https://www.cp2k.org, respectively. The Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) is an open-source Python module available at https://wiki.fysik.dtu.dk/ase/. The code that implements the materials screening is available from the corresponding author, Prof. Wei Zhang (email: wzhang0@mail.xjtu.edu.cn), upon reasonable request.

References

Wuttig, M. & Yamada, N. Phase-change materials for rewriteable data storage. Nat. Mater. 6, 824–832 (2007).

Zhang, W., Mazzarello, R., Wuttig, M. & Ma, E. Designing crystallization in phase-change materials for universal memory and neuro-inspired computing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 150–168 (2019).

Fong, S. W., Neumann, C. M. & Wong, H.-S. P. Phase-change memory—towards a storage-class memory. IEEE Trans. Electron. Dev. 64, 4374–4385 (2017).

Sebastian, A., Le Gallo, M., Khaddam-Aljameh, R. & Eleftheriou, E. Memory devices and applications for in-memory computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 529–544 (2020).

Youngblood, N., Ríos Ocampo, C. A., Pernice, W. H. P. & Bhaskaran, H. Integrated optical memristors. Nat. Photon 17, 561–572 (2023).

Xu, M. et al. Recent advances on neuromorphic devices based on chalcogenide phase‐change materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2003419 (2020).

Shastri, B. J. et al. Photonics for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing. Nat. Photon 15, 102–114 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Non-volatile tunable optics by design: from chalcogenide phase-change materials to device structures. Mater. Today 68, 334–355 (2023).

Gu, T., Kim, H. J., Rivero-Baleine, C. & Hu, J. Reconfigurable metasurfaces towards commercial success. Nat. Photon 17, 48–58 (2023).

Zhou, W., Shen, X., Yang, X., Wang, J. & Zhang, W. Fabrication and integration of photonic devices for phase-change memory and neuromorphic computing. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 6, 022001 (2024).

Kim, H. J. et al. Versatile spaceborne photonics with chalcogenide phase-change materials. npj Microgravity 10, 20 (2024).

Gerardin, S. & Paccagnella, A. Present and future non-volatile memories for space. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 57, 3016–3039 (2010).

Konstantinou, K., Lee, T. H., Mocanu, F. C. & Elliott, S. R. Origin of radiation tolerance in amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5 phase-change random-access memory material. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 5353–5358 (2018).

Yamada, N. et al. High speed overwritable phase change optical disk material. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. Part 1 26, 61–66 (1987).

Sun, Z., Zhou, J. & Ahuja, R. Structure of phase change materials for data storage. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 055507 (2006).

Siegrist, T. et al. Disorder-induced localization in crystalline phase-change materials. Nat. Mater. 10, 202–208 (2011).

Zhang, B. et al. Element-resolved atomic structure imaging of rocksalt Ge2Sb2Te5 phase-change material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 191902 (2016).

Iwasaki, H. et al. Completely erasable phase-change optical disc. II. Application of Ag-In-Sb-Te mixed-phase system for rewritable compact disc compatible with CD-velocity and double CD-velocity. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. Part 1 32, 5241–5247 (1993).

Ahmed, S. et al. Change in structure of amorphous Sb-Te phase-change materials as a function of stoichiometry. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 15, 2100064 (2021).

Wang, X.-D. et al. Multiscale simulations of growth-dominated Sb2Te phase-change material for non-volatile photonic applications. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 136 (2023).

Zheng, Y. et al. A complicated route from disorder to order in antimony-tellurium binary phase change materials. Adv. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202301021 (2023).

Salinga, M. et al. Monatomic phase change memory. Nat. Mater. 17, 681–685 (2018).

Zhang, W. & Ma, E. Single-element glass to record data. Nat. Mater. 17, 654–655 (2018).

Cheng, Z. et al. Antimony thin films demonstrate programmable optical nonlinearity. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd7097 (2021).

Chen, B. et al. Suppressing structural relaxation in nanoscale antimony to enable ultralow-drift phase-change memory applications. Adv. Sci. 10, 2301043 (2023).

Shen, X. et al. Surface effects on the crystallization kinetics of amorphous antimony. Nanoscale 15, 15259–15267 (2023).

Cheng, H.-Y. et al. Material engineering of GexSbyTez and GaxSby phase change materials for high performance phase change memory. ECS Meet. Abstr. MA2012-02, 2807–2807 (2012).

Sun, L. et al. Ab initio molecular dynamics and materials design for embedded phase-change memory. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 29 (2021).

van Pieterson, L., Lankhorst, M. H. R., van Schijndel, M., Kuiper, A. E. T. & Roosen, J. H. J. Phase-change recording materials with a growth-dominated crystallization mechanism: a materials overview. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 083520 (2005).

Song, Z. et al. 12-state multi-level cell storage implemented in a 128 Mb phase change memory chip. Nanoscale 13, 10455–10461 (2021).

Matsunaga, T. et al. From local structure to nanosecond recrystallization dynamics in AgInSbTe phase-change materials. Nat. Mater. 10, 129–134 (2011).

Yang, Z. et al. Designing conductive-bridge phase-change memory to enable ultralow programming power. Adv. Sci. 9, e2103478 (2022).

Wang, J.-J. et al. Tailoring the oxygen concentration in Ge-Sb-O alloys to enable femtojoule-level phase-change memory operations. Mater. Fut. 1, 045302 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Enhancing performances of phase change memory for embedded applications. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 13, 1800558 (2019).

Redaelli, A., Petroni, E. & Annunziata, R. Material and process engineering challenges in Ge-rich GST for embedded PCM. Mater. Sci. Semicon. Proc. 137, 106184 (2022).

Rao, F. et al. Reducing the stochasticity of crystal nucleation to enable subnanosecond memory writing. Science 358, 1423–1427 (2017).

Zewdie, G. M. et al. Chemical design principles for cache-type Sc-Sb-Te phase-change memory materials. Chem. Mater. 31, 4008–4015 (2019).

Qiao, C. et al. Local structure origin of ultrafast crystallization driven by high-fidelity octahedral clusters in amorphous Sc0.2Sb2Te3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 071901 (2019).

Hu, S., Liu, B., Li, Z., Zhou, J. & Sun, Z. Identifying optimal dopants for Sb2Te3 phase-change material by high-throughput ab initio calculations with experiments. Comput. Mater. Sci. 165, 51–58 (2019).

Wang, X.-P. et al. Time-dependent density-functional theory molecular-dynamics study on amorphization of Sc-Sb-Te alloy under optical excitation. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 1–5 (2020).

Li, Z., Si, C., Zhou, J., Xu, H. & Sun, Z. Yttrium-doped Sb(2)Te(3): a promising material for phase-change memory. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 26126–26134 (2016).

Hu, S., Xiao, J., Zhou, J., Elliott, S. R. & Sun, Z. Synergy effect of co-doping Sc and Y in Sb2Te3 for phase-change memory. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 6672–6679 (2020).

Liu, B. et al. Multi-level phase-change memory with ultralow power consumption and resistance drift. Sci. Bull. 66, 2217 (2021).

Xue, Y. et al. Phase change memory based on Ta–Sb–Te alloy –Towards a universal memory. Mater. Today Phys. 15, 100266 (2020).

Song, Z. T. et al. In 2018 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). 27.25.21–27.25.24 (IEEE).

Arnaud, F. et al. In 2018 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). 18.14.11–18.14.14 (IEEE).

Hatayama, S. et al. Inverse resistance change Cr(2)Ge(2)Te(6)-based PCRAM enabling ultralow-energy amorphization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 2725–2734 (2018).

Hatayama, S., Song, Y.-H. & Sutou, Y. Low resistance-drift characteristics in Cr2Ge2Te6-based phase change memory devices with a high-resistance crystalline phase. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 133, 105961 (2021).

Hatayama, S. et al. Cr-triggered local structural change in Cr2Ge2Te6 phase change material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 43320–43329 (2019).

Shuang, Y. et al. Evolution of the local structure surrounding nitrogen atoms upon the amorphous to crystalline phase transition in nitrogen-doped Cr2Ge2Te6 phase-change material. Appl. Surf. Sci. 556, 149760 (2021).

Hatayama, S., Yamamoto, T., Mori, S., Song, Y.-H. & Sutou, Y. Understanding the origin of low-energy operation characteristics for Cr2Ge2Te6 phase-change material: enhancement of thermal efficiency in the high-scaled memory device. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 44604–44613 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Spin glass behavior in amorphous Cr2Ge2Te6 phase-change alloy. Adv. Sci. 10, 2302444 (2023).

Carteaux, V., Brunet, D., Ouvrard, G. & Andre, G. Crystallographic, magnetic and electronic structures of a new layered ferromagnetic compound Cr2Ge2Te6. J. Phys. 7, 69–87 (1995).

Gong, C. et al. Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature 546, 265–269 (2017).

Xing, S., Zhou, J., Zhang, X., Elliott, S. & Sun, Z. Theory, properties and engineering of 2D magnetic materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 132, 101036 (2023).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Saito, Y. et al. Dimensional transformation of chemical bonding during crystallization in a layered chalcogenide material. Sci. Rep. 11, 4782 (2021).

Hatayama, S., Sutou, Y., Ando, D. & Koike, J. Crystallization mechanism and kinetics of Cr2Ge2Te6 phase change material. MRS Commun. 8, 1167–1172 (2018).

Xu, M. et al. Understanding CrGeTe3: an abnormal phase change material with inverse resistance and density contrast. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 9025–9030 (2019).

Liu, Y. T. et al. High‐throughput screening for phase‐change memory materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2006221 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Materials screening for disorder-controlled chalcogenide crystals for phase-change memory applications. Adv. Mater. 33, e2006221 (2021).

Raty, J. Y. et al. A quantum-mechanical map for bonding and properties in solids. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806280 (2019).

Xu, M. et al. Tailoring mid‐gap states of chalcogenide glass by pressure‐induced hypervalent bonding towards the design of electrical switching materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2304926 (2023).

Zagorac, D., Muller, H., Ruehl, S., Zagorac, J. & Rehme, S. Recent developments in the inorganic crystal structure database: theoretical crystal structure data and related features. J. Appl. Cryst. 52, 918–925 (2019).

Hjorth Larsen, A. et al. The atomic simulation environment—a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys. 29, 273002 (2017).

Larsen, P. M., Pandey, M., Strange, M. & Jacobsen, K. W. Definition of a scoring parameter to identify low-dimensional materials components. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 034003 (2019).

Deringer, V. L. et al. Bonding nature of local structural motifs in amorphous GeTe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10817–10820 (2014).

Mocanu, F. C., Konstantinou, K., Mavračić, J. & Elliott, S. R. On the chemical bonding of amorphous Sb2Te3. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 15, 2000485 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Chemical understanding of resistance drift suppression in Ge–Sn–Te phase-change memory materials. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 71–77 (2020).

Caravati, S., Bernasconi, M., Kühne, T. D., Krack, M. & Parrinello, M. Coexistence of tetrahedral- and octahedral-like sites in amorphous phase change materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 171906 (2007).

Park, J.-B. et al. Phase-change behavior of stoichiometric Ge2Sb2Te5 in phase-change random access memory. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154, H139 (2007).

Zhang, W. et al. Role of vacancies in metal-insulator transitions of crystalline phase-change materials. Nat. Mater. 11, 952–956 (2012).

Zhang, W., Wuttig, M. & Mazzarello, R. Effects of stoichiometry on the transport properties of crystalline phase-change materials. Sci. Rep. 5, 13496 (2015).

Bragaglia, V. et al. Metal-insulator transition driven by vacancy ordering in GeSbTe phase change materials. Sci. Rep. 6, 23843 (2016).

Wang, J.-J., Xu, Y.-Z., Mazzarello, R., Wuttig, M. & Zhang, W. A review on disorder-driven metal-insulator transition in crystalline vacancy-rich GeSbTe phase-change materials. Materials 10, 862 (2017).

Jiang, T.-T. et al. In situ characterization of vacancy ordering in Ge-Sb-Te phase-change memory alloys. Fundam. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2022.1009.1010 (2022).

Morikawa, T. et al. In 2007 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting. 307–310.

Wang, X., Shen, X., Sun, S. & Zhang, W. Tailoring the structural and optical properties of germanium telluride phase-change materials by indium incorporation. Nanomaterials 11, 3029 (2021).

Spreafico, E., Caravati, S. & Bernasconi, M. First-principles study of liquid and amorphous InGeTe2. Phys. Rev. B 83, 144205 (2011).

Sosso, G. C., Miceli, G., Caravati, S., Behler, J. & Bernasconi, M. Neural network interatomic potential for the phase change material GeTe. Phys. Rev. B 85, 174103 (2012).

Abou El Kheir, O., Bonati, L., Parrinello, M. & Bernasconi, M. Unraveling the crystallization kinetics of the Ge2Sb2Te5 phase change compound with a machine-learned interatomic potential. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 33 (2024).

Konstantinou, K., Mocanu, F. C., Lee, T. H. & Elliott, S. R. Revealing the intrinsic nature of the mid-gap defects in amorphous Ge(2)Sb(2)Te(5). Nat. Commun. 10, 3065 (2019).

Zhou, Y., Zhang, W., Ma, E. & Deringer, V. L. Device-scale atomistic modelling of phase-change memory materials. Nat. Electron. 6, 746–754 (2023).

Mo, P. et al. Accurate and efficient molecular dynamics based on machine learning and non von Neumann architecture. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 107 (2022).

Mocanu, F. C. et al. Modeling the phase-change memory material, Ge(2)Sb(2)Te(5), with a machine-learned interatomic potential. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 8998–9006 (2018).

Wang, G., Sun, Y., Zhou, J. & Sun, Z. PotentialMind: graph convolutional machine learning potential for Sb–Te binary compounds of multiple stoichiometries. J. Phys. Chem. C 127, 24724–24733 (2023).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Hutter, J., Iannuzzi, M., Schiffmann, F. & VandeVondele, J. cp2k: atomistic simulations of condensed matter systems. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 4, 15–25 (2013).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1703–1710 (1996).

Kuhne, T. D., Krack, M., Mohamed, F. R. & Parrinello, M. Efficient and accurate Car-Parrinello-like approach to Born-Oppenheimer molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 066401 (2007).

Nelson, R. et al. LOBSTER: local orbital projections, atomic charges, and chemical-bonding analysis from projector-augmented-wave-based density-functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 41, 1931–1940 (2020).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO—the Open Visualization Tool. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFB4404500). J.-J.W. thanks the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62204201). W.Z. thanks the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62374131). We acknowledge the HPC platform of Xi’an Jiaotong University and Computing Center in Xi’an for providing computational resources. The authors acknowledge XJTU for hosting their work at CAID. The International Joint Laboratory for Micro/Nano Manufacturing and Measurement Technologies of XJTU is acknowledged. R.M. gratefully acknowledges funding from the PRIN 2020 project “Neuromorphic devices based on chalcogenide heterostructures” funded by the Italian Ministry for University and Research (MUR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. and X.W. contributed equally to this work. W.Z. conceptualized this work. The materials screening and modeling were performed by S.S. and X.W. The ab initio simulations were done by S.S. with contributions from Y.J. The experiments were conducted by X.W. under the guidance of J.-J.W. The paper was written by S.S., X.W., and W.Z. with the help of other authors. E.M., R.M., Y.L., S.K., S.Z., and J.Z. contributed to the discussion of the data. All authors contributed to the discussions and analyses of the data and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, S., Wang, X., Jiang, Y. et al. High-throughput screening to identify two-dimensional layered phase-change chalcogenides for embedded memory applications. npj Comput Mater 10, 189 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01387-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01387-3