Abstract

The quantification of interphase properties between metals and their corresponding hydrides is crucial for modeling the thermodynamics and kinetics of the hydrogenation processes in solid-state hydrogen storage materials. In particular, interphase boundary energies assume a pivotal role in determining the kinetics of nucleation, growth, and coarsening of hydrides, alongside accompanying morphological evolution during hydrogenation. The total interphase energy arises from both chemical bonding and mechanical strains in these solid-state systems. Since these contributions are usually coupled, it is challenging to distinguish via conventional computational approaches. Here, a comprehensive atomistic modeling methodology is developed to decouple chemical and mechanical energy contributions using first-principles calculations, of which feasibility is demonstrated by quantifying chemical and elastic strain energies of key interfaces within the FeTi metal-hydride system. Derived materials parameters are then employed for mesoscopic micromechanical analysis, predicting crystallographic orientations in line with experimental observations. The multiscale approach outlined verifies the importance of the chemo-mechanical interplay in the morphological evolution of growing hydride phases, and can be generalized to investigate other systems. In addition, it can streamline the design of atomistic models for the quantitative evaluation of interphase properties between dissimilar phases and allow for efficient predictions of their preferred phase boundary orientations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Green hydrogen is a renewable energy carrier that has the potential to play a major role in the transition to a sustainable energy economy, as its combustion only releases water as a by-product1,2. In addition, hydrogen has been highlighted as a critical component for decarbonizing high-emission sectors such as transportation, industrial heating, chemical synthesis, steelmaking, and so forth3. Therefore, the advanced and reliable approaches for storing and delivering hydrogen are significantly important to enable hydrogen-based technologies and industrial processes.

Metal hydrides as solid-state hydrogen storage materials have several advantages over other classes of storage media owing to their high volumetric capacity and great hydrogen retainment characteristics allowing for nearly loss-free hydrogen storage during dormancy4,5. In addition, metal hydrides are often considered as safer storage solutions for applications where safety is a concern since their (de)hydrogenation cycles can operate under mild conditions as compared to the compressed gas-based storage that requires extremely high pressures6,7.

The (de)hydrogenation of metal hydrides is a coupled and complex process, involving surface reaction, hydrogen diffusion, and nucleation-and-growth during the phase transformation between metal and hydride phases. In this context, computational modeling and simulation approaches have been extensively utilized for unraveling the complicated operating mechanisms and determining the key driving and/or limiting factors for the storage mechanisms. To account for the multiscale nature of the relevant chemical, physical, and material processes, it is important to integrate the computational methods that can handle relevant effects at different lengths and time scales. Examples include combining parameters from atomic-scale simulations (e.g., first-principles calculations) and thermodynamic modeling (e.g., CALPHAD) or mesoscopic kinetic modeling (e.g., phase-field modeling). Within this framework, the accuracy of predictions by the larger scale simulations is highly sensitive to how accurately the atomistic parameters characterize the physical and chemical features of the associated properties.

It is important to note that the overall kinetics and reversibility of the (de)hydrogenation are often dictated by thermodynamic phase stability and phase transformation kinetics associated with the formation of hydrides. Modeling of the hydride phase formation requires not only the bulk properties of individual phases but also the interfacial properties between the associated phases8,9. For example, the interfacial energy is an important quantity to assess the energy barrier for the nucleation of a hydride phase10, which determines the nucleation rate. The interfacial energy at the interphase boundary mainly originates from two primary factors: chemical and elastic strain contributions. The chemical component originates from the variation of local atomic bonds across the interface, while the elastic strain arises from the lattice mismatch between the two adjoining phases. Therefore, the chemical contribution is considered as a short-range interaction, while the elastic strain contribution as a long-range counterpart. In addition, these two energetic factors often exhibit different characteristics (e.g., orientational anisotropy) for the metal/hydride interfaces. However, it is not straightforward to deconvolute the chemical and elastic contributions to the interfacial properties due to the lack of a well-established approach to accurately quantify chemo-mechanical properties of the interfaces expressed during hydride formation.

Intending to fill this gap, this work establishes a general modeling framework for utilizing Density Functional Theory (DFT) to analyze and quantify these interphase properties. We apply our approach to the FeTi-H system, which is one of the candidate materials for low-temperature solid-state stationary hydrogen storage11. It is worth noting that previous extensive studies have mostly been focused on processing and/or alloying of FeTi for improving hydrogen storage performance12,13. The relevant computational efforts have centered on atomic-level DFT calculations of bulk properties or reaction barriers to hydrogenation14,15,16,17,18, as well as hydrogen interactions with the surface oxide layers in terms of initial activation19. At the macroscopic level, the hydrogenation of FeTi was studied via computational thermodynamics, focusing on the stability of the associated bulk phases under external conditions20.

Nevertheless, the properties of the interphase boundaries have not been thoroughly explored thus far, despite their significant role as driving factors that must be fully understood for improving the thermodynamics and kinetics of (de)hydrogenation cycles of the FeTi-based storage materials. This study provides a comprehensive analysis and quantification of the interphase boundaries emerging from the formation of the β-FeTiH hydride in the α-FeTi matrix. At first, we derive a thermodynamic expression for computing the chemical contribution to the interface energies and demonstrate that using appropriate atomic models, the equation becomes independent of surface energies - a previously presumed requirement for quantification. Eliminating the reliance on obtaining surface energies translates to fewer required atomic model structures and DFT computational runs, which consequently streamlines the process while alleviating computational demands.

Subsequently, we apply our approach to study the properties of the interphase boundaries arising from the formation of the β-FeTiH hydride within the α-FeTi alloy. Our thermodynamic model is employed to quantify the pertinent chemical component, while the micromechanics are assessed by means of Khachaturyan-Shatalov (KS) microelasticity theory. The findings are then discussed regarding the interplay between chemical and mechanical contributions with respect to the stability and alignments of the interphase boundaries, which are compared, and in agreement, with experimental observations from the literature.

Methods

DFT settings and convergence

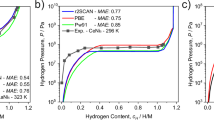

DFT calculations of the bulk and slab models were carried out with the Vienna ab-initio simulation package (VASP) version 6.2.121,22,23,24. For the description of the exchange and correlation effects, the Perdew and Wang (PW91)25,26 functional within the generalized gradient approximation was employed. Several exchange-correlation fuctionals were evaluated with respect to their accuracy in predicting experimental data. PW91 was chosen for this study as it could reproduce experimentally measured structural and elastic properties of the phases, and more importantly, it reproduces the hydrogenation reaction enthalpy, which is the only experimental information available that involves the metal, the hydride, and the hydrogen molecule. The complete results of these tests are described in the Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Figs. 1–5, and Supplementary Tables 1–5. We applied the projector-augmented wave method27 implemented in VASP and included all plane-waves within a kinetic energy cut-off of 500 eV for the calculations, yielding convergence of interface energies within less than 1 mJ/m2. By selecting the corresponding pseudopotentials, only the outer electrons in the 3p, 4s, and 3d orbitals were explicitly treated for Fe and Ti.

All structures were fully relaxed with respect to ionic positions until the residual atomic forces were less than 10−3 eV ⋅ Å−1, while electronic iterations converged with an energy tolerance of at least 10−8 eV. A Monkhorst-Pack scheme with a k-point spacing of 0.2 Å−1 was used for all calculations. This provides results converged within less than 1 meV/atom and results in only 1 k-point in the direction perpendicular to the slabs.

Moreover, since the phases analyzed in the present work do not present net magnetization at room temperature and hydrogenation conditions, no spin-polarization was attributed for all calculations in this work. The effect of including spin-polarization was tested for the calculations of bulk properties but showed negligible variations compared to those of non-spin-polarized calculations.

A convergence test was performed for all surface slabs as described by Fiorentini and Methfessel28 to select a minimum number of layers that produce variations in surface energy as low as 0.05 J/m2 with respect to well-converged surfaces of at least 15 layer thickness.

Bulk phase properties

In this work, the settings employed in the DFT calculations were benchmarked against bulk phase properties and the reaction energy

where \({E}_{{\rm{FeTi}}}^{{\rm{bulk}}}\) and \({E}_{{\rm{FeTiH}}}^{{\rm{bulk}}}\) denote the bulk total energies of the α (FeTi) and β (FeTiH) phases, respectively, and \({E}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) is the total energy of a single hydrogen molecule placed in a cell with 12.5 Å of vacuum space. Benchmarking is crucial to ensure the reliability of the calculated elastic constants necessary for the subsequent micromechanical analysis, as well as for other properties of the metal-hydride coupling, including the chemical contribution to the interphase boundary energies, elaborated in this study. It is noteworthy, however, that our approach enables the determination of this chemical energy contribution without the explicit need for bulk calculations, as demonstrated in Section “Surface and interface energies”.

The initial structures of the phases α (FeTi) and β (FeTiH) were obtained from the ’Materials Project’29, and then optimized with respect to ion position, cell shape, and volume, using different exchange-correlation functionals (see Supplementary Note 1 for functionals other than PW91). The total energy as a function of volume was fitted to the Birch-Murnaghan equation of states to obtain the values of the bulk modulus, its derivative, the equilibrium volume, and the lattice parameters of each phase. As shown in Figs. 3 and 8, which will be addressed more comprehensively in subsequent sections, the configuration of metal atoms within the β phase closely resembles that of the α phase, albeit with a minor distortion attributed to the presence of hydrogen within the interstitial sites. Furthermore, elastic constants were calculated employing the stress-strain relationship approach30,31. For each phase, the elastic tensor was acquired by analyzing its response in total energy when distortion steps are applied to the lattice parameters in all directions, i.e., compressive, tensile, and shear strain, as implemented in VASP.

From a thermodynamic perspective, the hydrogenation reaction is driven by the gradient of hydrogen chemical potential (μH) between the phases α and β. Hence, the existence of a stable interface only occurs under equilibrium conditions:

The hydrogen chemical potential, however, depends on the surrounding external conditions. Accordingly, this study formulates all energies that describe this equilibrium with respect to the grand potential Ω(V, T, μ). Neglecting the vibrational contributions to the free energy of the system (see Supplementary Note 2 for a discussion of this assumption), one can define the bulk potentials of the phases α and β as

and

respectively.

Although alloy hydrogenation generally occurs under paraequilibrium20,32, due to the structural similarity of metal and interstitial hydride phases, and because of the pronounced chemical disparity between metals and hydrogen atoms, it can be assumed that the variation of the chemical potential of the metallic species in interstitial metal-hydride systems is negligible, i.e.,

In such an equilibrium condition, the corresponding chemical potentials μFeTi and μFeTiH are not independent, but satisfy

The reaction potential of the β phase formation is then obtained based on the reaction \(\alpha -{\rm{FeTi}}+\frac{1}{2}{H}_{2}\to \beta\)-FeTiH as illustrated in Fig. 1via

emphasizing mathematically that the hydride phase becomes more stable when the hydrogen chemical potential increases and vice versa.

A direct calculation of the chemical potential of hydrogen with atomistic simulations is computationally costly. However, one can compute the ground-state energy \({E}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) as a reference, and then obtain the variation of the chemical potential Δμ from thermodynamic assessments of its Gibbs energy and/or well-established thermochemical tables:

In this work, both the ideal gas model (refer to Supplementary Note 3 for details) and the model from J.-M. Joubert33 (more accurate for high pressures) were employed for obtaining the chemical potential difference (\(\Delta {\mu }_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\)) and its relation to other thermodynamic quantities, such as temperature and pressure. Inserting Equation (10) into Equation (9) links the reaction potential ΔΩr to the DFT-calculated hydrogenation energy \(\Delta {E}_{r}^{{\rm{DFT}}}\) (see Equation (1)):

In the following, we apply the same concept to derive surface and interface energies and link them to the total energies calculated with DFT.

Surface and interface energies

From a thermodynamic perspective34,35,36, the surface energy γs of a phase ϕ is defined as the energy needed to create the surface (\(\Delta {\Omega }_{s}^{\phi }\)) per unit of area (A):

where the factor of \(\frac{1}{2}\) accounts for the presence of two identical surfaces in the surface slab model, and Nϕ is the number of bulk units of ϕ in that model. Similarly to the bulk, the grand potential can be written as Ω = E − ∑jNjμj in thermodynamic equilibrium, with E being the DFT energy, j running over all elements and Nj being the number of atoms of element j in the structure. Inserting this into Equation (12) gives

Thus, the surface energy can be approximated directly from the DFT energies for stoichiometric surface models, where \({N}_{j}^{{\rm{slab}}}={N}_{\phi }{N}_{j}^{\phi }\) for all elements j. However, the surface stoichiometry may also change for a given surface orientation due to different possible terminations and reconstructions. If there is excess (or deficiency) of a species compared to the bulk phase, the surface energy becomes dependent on the chemical potential of that species, i.e., chemistry-dependent. In that case, it is most convenient to reference the chemical potential against the DFT ground state energy Ej similar to Equation (10):

This allows to extrapolate the surface energy calculated with DFT

to experimental conditions at any given chemical potential37:

One approach for modeling interfaces involves creating a slab model that comprises two phases, each featuring distinct surfaces on either side of the slab, with an interface located in the middle (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 5 for reference). Following the same concept as for the calculation of the surface energies, the energy balance in Equation (12) is adapted for this type of model to express the energy of a single interface γi as

for an interface slab consisting of two phases ϕ1 and ϕ2 and having two surfaces with energies \({\gamma }_{{s}^{* }}^{{\phi }_{1}}\) and \({\gamma }_{{s}^{* }}^{{\phi }_{2}}\), respectively. Note that due to the common unit cell of the interface slab, the two phases must be strained to commensurate into the common section area Ai. Therefore, the reference states need to be strained accordingly, which is why these energies are marked with an asterisk (*).

Strained slab of phase ϕ1 (a), and Strained slab of phase ϕ2 (b) commensurate to form an interface slab (c). The vacuum-exposed strained surfaces of phases ϕ1 and ϕ2 are represented in blue and magenta, respectively, while the interface ϕ1/ϕ2 is represented in green. Dashed lines represent the periodic boundaries of the simulation cell.

Computation of interface energies in this scenario is resource-intensive because it requires the individual calculation of strained bulk systems and surface models. However, considering the locality of atomic-scale properties, the interface energy should not depend on the explicit surface structure model chosen for the interface model. Hence, there is some freedom in selecting the reference surface models. As follows, Equation (17) can be drastically simplified by choosing reference surface models that satisfy the relation:

This conceives a concept where both surface slabs (with grand potentials \({\Omega }_{{{\rm{slab}}}^{* }}^{{\phi }_{1}}\) and \({\Omega }_{{{\rm{slab}}}^{* }}^{{\phi }_{2}}\)) are cleaved in half, and these halved portions are united, forming an interface (see Fig. 2). Combining Equations (12) and (17) with this concept leads to

Note that, as before, there can be an excess or depletion of any species in the model, which becomes evident when incorporating the dependence on the chemical potential. For the α/β interfaces studied in this work, Equation (19) becomes:

Since we have the freedom to choose the amount of atoms in our reference models by increasing the number of layers or adding atoms on the surface, effectively generating a reconstruction, we pick the models of the strained surface slabs α and β with the same number of Fe and Ti atoms as that of the α/β interface model \(({N}_{{\rm{Fe/Ti}}}^{\alpha /\beta }={N}_{{\rm{Fe/Ti}}}^{\alpha }={N}_{{\rm{Fe/Ti}}}^{\beta})\) and double the number of hydrogen atoms in the surface slab β compared to that of the interface slab α/β \((2{N}_{{\rm{H}}}^{\alpha /\beta }={N}_{{\rm{H}}}^{\beta})\), thus simplifying Equation to:

In summary, the resulting Equation (21) demonstrates the feasibility of calculating the interface energy solely based on the DFT total energies of the α and β strained surface slabs and the α/β interface slab with the proper choice of the models. As an additional validation, the same conclusion is obtained by the derivation of the interface energy from a hydrogenation perspective (shown in Supplementary Note 4). It should be noted that this approach to generating interface structures fixes the stoichiometry of the interface model. In many cases, such as the hydrogenation of interstitial metal hydrides or the computation of intrinsic domain wall energies in ferroelectric materials38, this approximation is well justified, as the interfaces are coherent or semicoherent and only result from the incorporation of another element into the existing lattice39. Point defects, however, change the energies of the bulk phases and interfaces depending on the chemical potential of the defect. Modeling these defects is significantly more demanding, as they require much larger unit cells. Therefore, this work focuses on interface models with constrained stoichiometry.

Interphase boundary orientation

The hydride phase formation gives rise to large perturbations of local volume due to significant density change upon transformation, leading to a large lattice mismatch between metal (α) and hydride (β) phases. Therefore, the micromechanical responses play a pivotal role in determining the phase stability and the transformation kinetics. More specifically, the associated interfacial coherency strain energy strongly affects the morphology of the growing hydrides, as well as their growth kinetics of the hydride phase10. To efficiently assess the orientation of a low-energy interphase boundary between the hydride and matrix phases, the interfacial coherency strain energy density function, \(B(\overrightarrow{n})\), from Khachaturyan-Shatalov microelasticity theory (KS)40 can be used:

with,

and,

where \(\overrightarrow{n}\) is the unit vector that characterizes the interface normal in a three-dimensional Cartesian space. The term εij represents the stress-free transformation strain (SFTS), which relates the uniform lattice distortion strain necessary for the parent phase to transform into a given variant of the product phase when no stress response is considered. The term Cijkl is the elastic stiffness tensor, which is considered homogeneous (i.e., identical elastic moduli) between the product and the parent phase in KS theory. In addition, the theory also considers the size of the matrix to be infinite (i.e., stress-free state macroscopically), and a platelet-shape of the product phase (i.e., planar interface).

By finding the vectors \({\overrightarrow{n}}_{0}\) that minimize the function \(B(\overrightarrow{n})\), we can identify the elastically preferable phase boundary orientations as a result of the elastic properties of phases (i.e, metal and hydride) and their crystallographic orientation relationship. This represents the habit plane normal of the forming hydride phase.

Results and discussion

Bulk properties

The equilibrium volume, the lattice parameters, and the bulk moduli of the phases α and β were calculated with DFT and compared to the experimental measurements from Thompson and Buchenau41,42,43 in Table 1. The calculated reaction energy of the β phase was found to be − 24.94kJ/mol.H2, in excellent agreement with the reaction enthalpy for the formation of β hydrides during FeTi hydrogen absorption, ranging from − 22.8 to − 27.4kJ/mol.H211.

The calculated elastic constants of the cubic α-FeTi phase are compared to theoretical and experimental data from the literature as listed in Table 2. The values obtained in this work agree well with those of the literature, especially for constants related to the shear modulus (c12 and c44).

Measured data on elastic properties of β-FeTiH hydride have been scarce until now due to the fact that FeTi hydrogenation is accompanied by the formation of cracks, which hinders the fabrication of bulk, crack-free hydrogenated material, usually obtained as a powder. Therefore, there is a lack of mechanical testing data on FeTi hydrides in the literature. However, as the formation enthalpy of the β-phase and the elastic properties of the α-phase are well described by the DFT settings employed in this work, a good level of accuracy may also be expected for the calculated properties of the bulk β-FeTiH hydride (see Table 6).

Surface and interface modeling

In order to construct an atomistic model for the α/β interface, one must know the orientation relationship between the phases. From a geometric analysis of the crystal structure of the hydrides of the FeTi alloy, Westlake44 suggested that the formation of the β phase from the matrix of the α phase would occur through the shared planes \({(110)_{\alpha}\Vert(100)_{\beta}},\,(1\bar10)_{\alpha}{\Vert}(010)_{\beta}\) and (001)α∥(001)β. This simple geometric relationship was adapted and is represented by an atomistic model in Fig. 3.

a Indication of the orientation of the β hydride in relation to six α phase unit-cells from the viewpoint of their (001)α∥(001)β common plane (note that the representation of the β-phase unit cell as a yellow square is deformed to fit the α-matrix); (b) A single unit-cell of a α-phase with indications of the interface plane (110)α in green and the (001)α plane in yellow; (c) A single unit-cell of the β-phase and the indication of the interface plane (100)β in green and a common plane (001)β in yellow. Gray: Fe atoms; white: Ti atoms; cyan: H atoms.

The orientation relationship shown in Fig. 3 was used as a basis for the construction of the surface and interface slabs analyzed in this work. For the α-FeTi phase, symmetric slabs were built for the orientations (110)α (structurally identical to \(\left.({1\bar10})_{\alpha}\right),\) and (001)α, while for the β-FeTiH phase (010)β, (001)β, and (100)β slabs were created. Depending on the phase and orientation of the slab, different terminations are possible, as illustrated in Fig. 4. In the following, these terminations will be referenced with superscripts attached to the orientation. For example, \({(100)}_{\beta }^{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) refers to the hydrogen terminated (100) surface of the β-FeTiH phase.

For the construction of interface slabs, the α and β surface slabs were cleaved along their common plane and stacked together. A vacuum space of at least 15 Å was added to separate the interface slabs from their periodic image. The amount of vacuum and the distance between the surface and the interface were chosen with respect to the convergence test performed for the calculation of the surface energy, i.e., with a minimum number of atomic layers to ensure sufficient bulk material that mitigates the interaction effects between their surfaces and the interface. Despite the metallic and charge-neutral nature of the systems studied, more vacuum space was tested to ensure that 15 Å was sufficient to mitigate any residual influence of electric fields across the vacuum region. Figure 5a–c shows the \({(110)}_{\alpha }^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\parallel {(100)}_{\beta }^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\) interface slab atomic model (Fig. 5c), and their associated strained \(\scriptstyle{(110)}_{{\alpha }^{* }}^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\) (Fig. 5a), and \(\scriptstyle{(100)}_{{\beta }^{* }}^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\) (Fig. 5b) surface slabs, as an example. See Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Figs. 10–16 for illustrations of all the orientations.

a strained \({(110)}_{{\alpha }^{* }}^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\) slab, (b) strained \({(100)}_{{\beta }^{* }}^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\) slab, and (c) \({(110)}_{\alpha }^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\parallel {(100)}_{\beta }^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\) interface slab. The interface \({(110)}_{\alpha }^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\parallel {(100)}_{\beta }^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\), strained surface \({(110)}_{\alpha }^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\), and strained surface \({(100)}_{\beta }^{{\rm{FeTi}}}\) regions are represented in green, blue, and magenta. Gray: Fe atoms; white: Ti atoms; cyan: H atoms.

Due to the difference in the lattice parameters of the α and β phases, the area and geometry of their slab sections also differ among them. Figure 6 exemplify it for the case of the slab sections of (110)α, (100)β, and (110)α∥(100)β. As mentioned in Section “Surface and interface energies”, this disparity creates a mismatch and the unit cell of the interface slab model must be chosen so that the α and β slabs are commensurate. Different approaches for commensurate two phases are reported in the literature, the most common being the so-called (1 × 1) model, where only the unit cell of one phase is used and the second is scaled to meet the two lattices composing the interface35,45. However, because the calculated bulk moduli of the α and β phases are very similar (see Table 1), and the hydrogenation process is reversible (the β phase nucleates in the α phase during absorption and vice versa during desorption), the averaged lattice parameters of the slabs α and β were chosen as the lattice parameters of the interface slabs. The use of the α phase lattice parameters was tested, though did not significantly change the resulting interface energy of the (110)α∥(100)β interface (Δγi ≈ 1%, i.e., 0.7 mJ m–2).

Surface energies

As stated in Section “Surface and interface modeling” and illustrated in Fig. 4, for a given orientation, the slabs present different types of termination. Unlike the (110)α surface, which presents only one kind of termination, the (001)α surface may present two different terminations: \({(010)}_{\alpha }^{{{\rm{Fe}}}_{2}}\) and \({(010)}_{\alpha }^{{{\rm{Ti}}}_{2}}\). If one constructs (001)α and (010)β slabs with the same termination on both surfaces, the slab would deviate from the Fe0.5Ti0.5 equimolar stoichiometry, and the surface energy becomes dependent on the chemical potential of Fe or Ti. The metallic elements in FeTi tend to reduce the energy of the system by a large amount via ordering in the body-centered cubic (bcc) lattice, and their variation of the chemical potential is expected to be acutely sensitive to small variations of the metallic composition. This variation is difficult to determine from an atomistic perspective and, similarly, extrapolations from thermodynamic assessments to low temperatures may be quantitatively inaccurate if only high-temperature data are used to assess thermodynamic model parameters20,46.

Therefore, when calculating non-stoichiometric slab surface energies, one has to choose elements that act as a viable reference state for the chemical potential. To ensure consistency, the total energy per atom of bcc-Fe and H2 were chosen as the reference state chemical potential for all the non-stoichiometric slabs analyzed (see Equation (16)). The surface energies in the ground state were calculated using Equation (16) with Δμj = 0, and the results are shown in Table 3.

As discussed by Z. Łodziana47, the (110)α lattice plane has the densest atom packing and is expected to present the lowest surface energy among the surfaces of the phase α. This relation was observed, and although the calculation of surface energies is highly sensitive to the DFT exchange-correlation functional used48,49, the results of this work are qualitatively and quantitatively consistent with those of Z. Łodziana.

As described in section “Surface and interface energies” (as well as in Supplementary Note 3), the variation in the chemical potential was referenced on the total energy of the H2 molecule in the ground state, allowing the investigation of the pressure dependence. Consequently, Equation (10) was combined with the ideal gas model (\({\mu }_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}^{id}\)), see Supplementary Equation (4), and Joubert’s model (\({\mu }_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}^{{\rm{Joubert}}}\))33 for the H2 gas. Given our focus on understanding the hydrogen effect on the stability of the surfaces, an extended analysis of the influence of the metallic chemical potential on the surface energies of (001)α and (001)β is presented in the Supplementary Note 3. The effects of H2 partial pressure on the surface stability for each surface energy calculated as a function of hydrogen gas pressure are shown in Fig. 7.

Calculated (a) (110)α and (100)β (b) (\(1{\bar{1}}0\))α and (010)β and (c) (001)α and (001)β surface energies over pressure at 298.15 K. Note that each panel corresponds to surfaces parallel to the given interface orientation: (110)α∥(100)β, \((1\bar10)_{\alpha}\Vert(010)_{\beta}\) and (001)α∥(001)β, respectively. The bottom and top horizontal axes show the relationship between hydrogen H2 gas pressure and hydrogen chemical potential. For surfaces dependent on the hydrogen chemical potential, the Joubert Gibbs energy model for H2 gas (\({\mu }_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}^{{\rm{Joubert}}}\))33 was used. Superimposed red dotted lines represent the coincident surface energy when calculated using the ideal model for the gas H2 (\({\mu }_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}^{id}\)).

From Fig. 7, one can observe that among the surfaces studied, and within the hydrogen partial pressure conditions for FeTi hydrogenation (between 1 × 104 Pa and 1 × 107 Pa, as shown as the shaded region in Fig. 7)20, the surfaces terminated with hydrogen are energetically significantly more favorable. Among them, the \({(001)}_{\beta }^{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) surface shows the highest stability. As a result, the shift in ideal properties of the H2 gas33, occurring only above 2 × 108 Pa, does not influence the order of the stability rank of surface energies. This quantitatively confirms that the hydrogenation of FeTi is also possible from the perspective of surface thermodynamics.

Moreover, under high-pressure conditions, the \({(100)}_{\beta }^{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) surface energy approaches zero. On a purely theoretical basis, a negative value for the surface energy means that the formation of such a surface would be a spontaneous thermodynamic process; however, for such pressure levels, the H2 gas itself is expected to undergo a continuous phase transformation into a solid state2,33. Furthermore, at room temperature and partial hydrogen pressures above 1 × 106 Pa, the β phase is expected to absorb hydrogen and transform into either β2 or γ phase20.

Interface energies

When the β phase is formed from the hydrogenation of the α phase, the metallic structure undergoes a volume expansion of around 1.25 Å3 per metallic atom, which represents an increase of ~11 % in volume. This variation is mainly related to the elongation along the aβ (i.e., x axis represented in Fig. 3c). Among the interfaces examined in this study, the (110)α(100)β is consequently the least affected by this expansion and culminates in forming a highly coherent interface.

For the (110)α∥ (100)β interface, i.e., \([\bar110]_{\alpha}\Vert[010]_\beta\), and [001]α∥ [001]β, the α region is stretched in the former direction and compressed in the latter, while the β region is compressed and stretched in the opposite way (see Fig. 6). The \((\bar110)_{\alpha}\Vert(010)_{\beta}\) interface, i.e., [001]α∥ [001]β, and [110]α ∥[100]β, alternates compression and stretching along the interface plane directions, with a higher level of compression and stretching occurring along the [100]β (or [110]α) direction (see Fig. 3). On the contrary, for (001)α ∥(001)β, i.e., [110]α ∥[100]β, and \([\bar110]_{\alpha}\Vert[010]_{\beta}\), the α region is stretched and the β region is compressed along both directions. Table 4 summarizes quantitatively these lattice mismatches.

When these misfits are present, the formation of coherent interfaces increases the free energy of the system due to elastic strain fields that arise50.

Due to these features, the energy needed to form a coherent interface is composed of two contributions:

-

The chemical energy that arises due to a less stable atomic bonding state occurring at the interface.

-

The elastic energy resulting from the strain necessary to achieve a commensurate crystal lattice.

This degree of coherency was also inferred when it was analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) by Schober51. The author observed the formation of coherent and semicoherent lenticular plates of the β phase, which were expressed oriented along the [001]α direction. The dominant interface was observed to appear parallel to the (110)α plane.

Table 5 lists the calculated chemical contributions to the interface energies of the three different orientations (110)α∥(100)β, \((1\bar10)_{\alpha}\Vert(010)_{\beta}\), and (001)α∥(001)β, created based on surface slabs with different terminations.

However, the value of the interface energy was observed to be consistent and not affected by the surface termination of the precursor slabs. The difference between the interfacial energies for a given orientation with different terminations is found to be within the convergence limit of DFT, ~10 mJ m−2 (refer to Supplementary Note 2). This validates the approach introduced in Section “Surface and interface energies”, since the interface energies should be independent of surface processes, which in practice occur far away from the interface. The non-reliance on surface energies simplifies interface modeling by allowing the choice of termination and/or reconstruction by convenience. The approach presented here demonstrates that it is not necessary to compute surface energies to quantify the chemical contribution to the interface energy, a presumed prerequisite52,53. Moreover, by avoiding dependence on the bulk and surface energy references, this way of modeling should also improve the cancelation of errors intrinsic to the DFT total energy calculations.

It is worth noting that, as explained in Section “Surface and interface energies”, the values of \({E}_{{\rm{slab}}* }^{\alpha }\) and \({E}_{{\rm{slab}}* }^{\beta }\) required for Equation (21) are calculated using strained α and β slabs having the same numbers of FeTi pairs as the interface slab. Thus, the total energy of each precursor slab contains the elastic energy associated with the strain necessary to create the coherent interface. The calculated interface energy (γi) is therefore a representation of the chemical contribution to the interphase boundary energy. The values obtained in the interval between 57.3 mJ m−2 and 100.4 mJ m−2 are consistent with the estimated value for coherent interfaces that usually falls in the range between 50 mJ m−2 8,54and 200 mJ m−2 50.

Micromechanical analysis

As a baseline case, we first consider fully coherent interfaces between the β hydride phase and the α parent phase for the micromechanical analysis in comparison with the chemical contribution counterpart we analyzed for the same types of interface in the previous sections. We then examine the possible coherency loss and its consequence to the phase boundary energy and orientations.

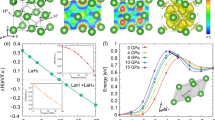

For convenient consideration of the lattice correspondence, the orthogonal lattice vectors and the corresponding lattice parameters of the α phase were redefined within our micromechanical analysis. Specifically, the crystallographic orientation of the α phase was adapted in a way that it satisfies the orientation relationship with the β phase discussed above (see Fig. 3a and the corresponding caption for clarification). The lattice parameters of the α phase were then newly defined on the Cartesian coordinate system for the β phase. Within this crystallographic framework, the crystal structure of the α phase can be regarded as a tetragonal structure (see Fig. 8a), while the β phase counterpart is an orthorhombic structure (see Fig. 8b). As illustrated in Fig. 8a, b, the unit cells of both phases include four common metallic atoms, emphasizing the specific volumetric expansion resulting from hydrogenation. Therefore, we considered the formation of the β hydride in the α phase as a tetragonal-to-orthorhombic phase transformation involving large volume expansion, which is clearly described in Fig. 8c. From the lattice correspondence shown in the figure, the deformation gradient tensor for the α-to-β transformation is obtained as

where \({\delta }^{a}=\frac{{a}_{\beta }-{a}_{\alpha }}{{a}_{\alpha }}\), \({\delta }^{b}=\frac{{b}_{\beta }-{b}_{\alpha }}{{b}_{\alpha }}\), \({\delta }^{c}=\frac{{c}_{\beta }-{c}_{\alpha }}{{c}_{\alpha }}\), with aα, bα, cα and aβ, bβ, cβ being the lattice parameters of the α, and β phases, respectively. Based on the finite strain formalism, the SFTS is then computed by:

where I is the identity matrix and \({[{F}_{ij}]}^{\intercal}\) is the transpose of Fij.

By considering equivalent symmetrical operations for the tetragonal α phase (aα = bα) to the orthorhombic β phase transformation, two distinct structural variants can be identified, resulting in the two corresponding SFTS tensors (Fij−I, and Fij−II), that are related by a 90∘ rotation around the c lattice vector (i.e., z axis shown in Fig. 8c). Using the lattice parameters from our first-principles calculations, the computed SFTSs are given as the following:

and,

To account for the homogeneous modulus assumption in the KS theory, i.e., the elastic moduli of the parent and product phases are assumed the same, a simple average of the elastic moduli of the α and β phases was used to construct the homogeneous elastic stiffness tensor (Cijkl) used in Equations (22)–(24).

Note that we used the lattice parameters and elastic moduli of the two phases defined on the same Cartesian coordinate system (i.e., x − y − z for the β phase in Fig. 8c) for consistency within the micromechanical analysis, which are tabulated in Table 6. We also emphasize that all the reference values were derived from our first-principles calculations.

Figure 9a shows the plot of the computed \(B(\overrightarrow{n})\) using the anisotropic elastic stiffness tensor and the SFTS we derived above.

Spherical plots of \(B(\overrightarrow{n})\) for a flat and coherent interface (a) general three-dimensional view with gradient colors representing the values in GPa (note that some level of transparency is applied to the \(B(\overrightarrow{n})\) surface in order to highlight the minimum values). Black arrows represent two instances of directions that minimize the interfacial coherency strain energy density, \(\overrightarrow{{n}_{0}}\). b Polar plot of \(B(\overrightarrow{n})\) projected on the (001)β plane with \(\overrightarrow{{n}_{0}}\) represented with blue arrows. c Same as (a) but viewed from the [010]β direction (red arrows) and zoomed on the minimum points.

The direction that minimizes \(B(\overrightarrow{n})\) (Equation (22)), represented by the unit vectors \({\overrightarrow{n}}_{0}\), corresponds to the preferred phase boundary (i.e., habit plane) normal for the formation of the product phase. The preferred phase boundary normal \({\overrightarrow{n}}_{0}\) was identified by numerical minimization as indicated in Fig. 9 (with arbitrary magnitude). The identified unit vector \({\overrightarrow{n}}_{0}\) is given by \(\left[\pm 0.942,0.000,\pm 0.335\right]\) in Cartesian coordinate system, leading to \(B({\overrightarrow{n}}_{0})=0.093\,{\rm{GPa}}\) as the minimum interfacial coherency strain energy density. Within the lattice plane system of the β phase (see Fig. 8), the corresponding habit plane is close to the {301}β family of crystal planes, which is approximately equivalent to the {120}α plane in the original lattice plane system for the cubic α phase (see Fig. 3b for reference).

From the chemical contribution point of view, the most energetically stable interface is (001)α∥(001)β as indicated in Table 5. By transforming this interface notation to the coordinate system for the micromechanical analysis (see Fig. 8 for clarity), the corresponding plane is normal to the z axis, which carries the highest strain energy density, as shown in Fig. 9a. The discrepancy between the chemically and the mechanically stable interface orientations may indicate how the phase boundary evolves as the hydride grows. Note that the relative impact of the chemical contribution scales with the total interface area, while the mechanical contribution counterpart scales with the volume of the particle. Therefore, at the early stage of hydride phase formation in a matrix metal phase, the chemical contribution to the interface energy is dominant, of which anisotropy determines the morphological behavior of the forming phase (i.e., (001)β is preferred). On the other hand, as the hydride phase grows, the strain energy contribution commensurate with interfacial mismatch between the adjoining crystal lattice increases and becomes more dominant (i.e., {301}β is preferred).

So far, we only considered fully coherent interfaces. However, as the hydride phase grows more, the accumulation of the coherency strain energy may significantly lower the phase stability due to large volume expansion. Therefore, the phase boundaries tend to lose the interfacial coherency by creating an array of misfit dislocations to accommodate the large volume expansion, which partially releases the coherency strain energy. In particular, the coherency loss is expected to occur when the energy to form the dislocations becomes lower than the energy penalty to maintain interfacial coherency, which determines the critical condition for transitioning from coherent to semi-coherent (or incoherent) interfaces40,50,54. We provide an estimate analysis of a critical particle size before plastic relaxation in the Supplementary Note 6.

With regard to the directional tendency of the misfit dislocation array, the formation of the array along the x and y directions are less probable than along the z direction since (001)β interface boundary incorporates the most chemically stable atomic configuration, which may have a propensity for maintaining its intrinsic defect-free atomic configuration. In addition, since the Burgers vector (\(\overrightarrow{b}\)) along the z axis is shorter than those along the x and y axes (refer to Table 6), the formation of misfit (edge) dislocation along the z axis is expected to be energetically more stable, considering that the dislocation energy is proportional to the magnitude of \(\overrightarrow{b}\)55. Therefore, we may assume that the loss of coherency occurs preferentially along the [001] direction.

Following this assumption, we examined the effect of the coherency loss along the [001] direction on the phase boundary orientation. For this purpose, a strain component \({\varepsilon }_{33}^{def}\) was introduced to account for modification of the SFTS due to the formation of misfit dislocations that perturb the lattice coherency along the z axis. The value of \({\varepsilon }_{33}^{def}\) may vary from 0 to \(-{\varepsilon }_{33}^{coh}\) (=−δc), corresponding to a transition from a perfectly coherent to a perfectly incoherent interface (i.e., complete loss of coherency) along the [001]β axis, respectively56, while maintaining the lattice coherency along other direction (i.e., mixed interfacial coherency). As an extreme case, we considered the complete loss of coherency along [001], leading to \({F}_{33-I}={\varepsilon }_{33}^{coh}+{\varepsilon }_{33}^{def}={\delta }^{c}-{\delta }^{c}=0\)56,57.

Figure 10 compares the full coherency and the mixed coherency scenarios for the cross-section of the function \(B(\overrightarrow{n})\) along the (001)β plane in polar coordinates. For the mixed coherency case (i.e., complete loss of coherency only along [001]), the family of planes that minimize \(B(\overrightarrow{n})\) becomes {100}, while for the fully coherent case, the identified habit plane is inclined by an angle of 19.5∘ with respect to the planes {100}. Note that the {100} planes correspond to the (110)α∥(100)β interface plane shown in Fig. 3. Interestingly, as also observed by Heo et al.56, the calculated value of \(B({\overrightarrow{n}}_{0})\) for the mixed coherency case (0.0966 GPa) remains almost the same as that of the fully coherent counterpart (0.0931 GPa). This indicates that the phase boundary orientation varies due to coherency loss, while the corresponding strain energy contribution being almost unchanged.

Importantly, our findings discussed above provide insight into possible phase boundary orientation variation during the hydride phase formation and growth from {001}α∥{100}β (chemically stable) to {120}α∥{301}β (mechanically stable with full coherency) to {110}α∥{100}β (mechanically stable with mixed coherency). This is evidenced by an experimentally characterized β hydride shape formed in FeTi reported in the literature (e.g., micrograph shown in Schober’s work39,51). Figure 11 shows an adapted micrograph presented in Fig. 2 from Schober51. As observed in the experimental micrograph (see Fig. 11), lenticular plate-like particles of μm size are formed with interphase boundaries parallel to the planes (110)α. It is interesting to note that the tips of the hydrides form closing sharp shapes with different boundary orientations inclined by ≈20∘ with respect to the (110)α planes, which is close to our predicted phase boundary orientation with full coherency.

As discussed above, for μm-sized large precipitates, it is reasonable to expect that the elastic contribution to the interphase boundary energy is the primary driving factor influencing the morphology of the precipitates. Therefore, the phase boundary orientation is most likely to be aligned along the mechanically stable direction. Based on our analysis of the two extreme cases that may occur along the [001] direction (i.e., fully coherent and fully incoherent (or complete loss of coherency) cases), we suggest that the habit plane orientations predicted by our micromechanical analysis for the two cases may bound the range of phase boundary orientations within the tip-region, which explains the dominant interphase boundary orientations observed by Schober51.

However, we also caution that, as discussed by Heo et al.56, there could be many distinct combinations of interfacial defects along different crystallographic orientations, leading to stabilization of the same habit plane. Thus, the creation of misfit dislocation along the z axis may be only one of many possible defect combinations that stabilize the {100} phase boundaries.

It is also important to mention that due to the instability of β-FeTiH hydride under low hydrogen pressures and the influence of the electron beam, an electron microscopy study of the hydride interface and morphology is extremely challenging, leading to scarce electron microscopy images (e.g., TEM micrographs) of hydrides in the literature. To our knowledge, the only comparable micrographs are those provided by Schober (Fig. 11). In addition, the FeTi intermetallic is often alloyed with essential elements that improve activation or adjust the hydrogenation condition to specific temperature and pressure. Most available experimental studies focus primarily on these materials, which further complicates a direct comparison between our modeling results and the existing experimental data in the literature. One of the few examples is a recent study58 presenting larger-scale micrographs of hydride in FeTi containing vanadium and cerium. The authors found the eutectoid-like lamellar growth of two-phase metal/hydride microstructure nucleated from a cerium precipitate surface. Compositional fluctuations and solute diffusion operate this formation mechanism, and the metal-hydride habit plane could not be clearly identified. Due to the significant influence of the precipitates on the hydride morphology examined in that work, their characterized interface features are not directly comparable with our atomistic and mesoscopic approaches. However, their analysis demonstrated the same preferred metal-hydride orientation relationship and found an increased dislocation density at the interfaces, highlighting the role of strain energy coherency loss in determining interfacial features at larger scales.

In conclusion, we established a comprehensive multiscale modeling framework that combines atomistic and mesoscopic modeling approaches for investigating the chemo-mechanical properties of interphase boundaries in this study.

A simplified approach based on first-principles calculations was proposed to deconvolute chemical and mechanical contributions to the total interphase boundary energy. It was shown that an appropriate choice of reference structures does not only decouple the chemical interface energy from the associated strain energy but also reduces the number of required first-principles calculations. The feasibility of the method was demonstrated by its successful application to quantitatively assess the chemical interface energies of several orientations in the FeTi metal-hydride system. In addition, the thermodynamic stability analysis of surfaces based on first-principles calculations demonstrated the wide range of surface energies of different potential surface terminations in the FeTi-H system depending on the hydrogen partial pressure. Yet, our approach quantifies chemical contributions to the interface energies that do not depend on the surface termination, but only on the local structure of the interface.

The lattice parameters and elastic moduli derived from first-principles calculations then informed the micromechanical modeling approach based on KS microelasticity theory for predicting the mechanical contribution to the interface energy. This approach allowed to compute mechanically stable phase boundary orientations for the possible interfacial coherency states. Remarkably, the analyzed phase boundary orientations are consistent with the experimental observations of hydride morphology reported in the literature.

As a final remark, we emphasize that delving deeper into the phase-boundary formation mechanism of hydrides and the decoupling of chemo-mechanical energy allows for integrating thermodynamics and micromechanics into kinetic models in a physically consistent way. The integrated kinetic models will enable direct and controlled simulations of the metal hydrogenation process operated by coupled chemo-mechanical mechanisms. For instance, the derived parameters and established mechanistic understanding in this work can serve as a critical step toward the development of a quantitative phase-field model59,60,61,62,63,64,65 for directly simulating the hydrogenation of FeTi and the associated hydride microstructure evolution.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Marbán, G. & Valdés-Solís, T. Towards the hydrogen economy? Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 32, 1625–1637 (2007).

Züttel, A. Materials for hydrogen storage. Mater. Today 6, 24–33 (2003).

Okano, K., Maruta, A. & Sasaki, K. Future Technological Directions 117–119 (Springer Japan, Tokyo, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56042-5_6.

Hirscher, M. Handbook of Hydrogen Storage: New Materials for Future Energy Storage, Vol. 41 (Wiley, 2016).

Buchner, H. Energiespeicherung in Metallhydriden (Springer, 1982).

Broom, D. P. Hydrogen Storage Materials: The Characterization of Their Storage Properties. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

Sasaki, K. et al. Hydrogen Energy Engineering: A Japanese Perspective. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56042-5 (2016).

Costa e Silva, A. Importance of interfacial energy in precipitation modeling using computational thermodynamics techniques. In TMS 2015 144th Annual Meeting & Exhibition 1409–1416 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Ury, N. et al. Kawin: an open source Kampmann-wagner numerical (KWN) phase precipitation and coarsening model. SSRN Electron. J. 255, 118988 (2022).

Heo, T. W., Colas, K. B., Motta, A. T. & Chen, L. Q. A phase-field model for hydride formation in polycrystalline metals: application to δ-hydride in zirconium alloys. Acta Mater. 181, 262–277 (2019).

Dematteis, E. M., Berti, N., Cuevas, F., Latroche, M. & Baricco, M. Substitutional effects in TiFe for hydrogen storage: a comprehensive review. Mater. Adv. 2, 2524–2560 (2021).

Dreistadt, D. M. et al. An effective activation method for industrially produced tifemn powder for hydrogen storage. J. Alloy. Compd. 919, 165847 (2022).

Shang, Y. et al. Ultra-lightweight compositionally complex alloys with large ambient-temperature hydrogen storage capacity. Mater. Today 67, 113–126 (2023).

Kinaci, A. & Aydinol, M. K. Ab initio investigation of FeTi–H system. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 32, 2466–2474 (2007).

Izanlou, A. & Aydinol, M. K. An ab initio study of dissociative adsorption of H2 on FeTi surfaces. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35, 1681–1692 (2010).

Bakulin, A. V., Kulkov, S. S., Kulkova, S. E., Hocker, S. & Schmauder, S. Influence of substitutional impurities on hydrogen diffusion in B2-TiFe alloy. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 39, 12213–12220 (2014).

Jung, J. Y., Lee, Y.-S., Suh, J.-Y., Huh, J.-Y. & Cho, Y. W. Tailoring the equilibrium hydrogen pressure of TiFe via vanadium substitution. J. Alloy. Compd. 854, 157263 (2021).

Kim, H. et al. A new perspective on the initial hydrogenation of TiFe0.9M0.1 (M = V, Cr, Fe, Co, Ni) alloys gained from surface oxide analyses and nucleation energetics. Appl. Surf. Sci. 610, 155443 (2023).

Santhosh, A. et al. Influence of near-surface oxide layers on TiFe hydrogenation: mechanistic insights and implications for hydrogen storage applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 18776–18789 (2023).

Alvares, E. et al. Modeling the thermodynamics of the FeTi hydrogenation under para-equilibrium: an ab-initio and experimental study. Calphad 77, 102426 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671–6687 (1992).

Burke, K., Perdew, J. P. & Wang, Y. Derivation of a generalized gradient approximation: the PW91 density functional. in Electronic Density Functional Theory: Recent Progress and New Directions 81–111 (Springer US, 1998).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Fiorentini, V. & Methfessel, M. Extracting convergent surface energies from slab calculations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 8, 6525–6529 (1996).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the materials project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Le Page, Y. & Saxe, P. Symmetry-general least-squares extraction of elastic data for strained materials from ab initio calculations of stress. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 65, 1–14 (2002).

De Jong, M. et al. Charting the complete elastic properties of inorganic crystalline compounds. Sci. Data 2, 1–13 (2015).

Flanagan, T. B. & Oates, W. A. Some thermodynamic aspects of metal hydrogen systems. J. Alloy. Compd. 404-406, 16–23 (2005).

Joubert, J. M. A Calphad-type equation of state for hydrogen gas and its application to the assessment of Rh-H system. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35, 2104–2111 (2010).

Heifets, E., Ho, J. & Merinov, B. Density functional simulation of the BaZrO3 (011) surface structure. Phys. Rev. B 75, 155431 (2007).

Martin, L., Vallverdu, G., Martinez, H., Le Cras, F. & Baraille, I. First principles calculations of solid-solid interfaces: an application to conversion materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 22063–22071 (2012).

Bottin, Fmc & Finocchi, F. SrTiO3 substrates capped with a GaAs monolayer: an ab initio study. Phys. Rev. B 76, 165427 (2007).

Reuter, K. & Scheffler, M. Composition, structure, and stability of RuO2(110) as a function of oxygen pressure. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 65, 1–11 (2002).

Zhang, X. et al. First-principles calculations of domain wall energies of prototypical ferroelectric perovskites. Acta Mater. 242, 118351 (2023).

Schober, T. & Schaefer, W. Transmission electron microscopy neutron diffraction studies of FeTi-H(D). J. Less Common Met. 74, 23–31 (1980).

Khachaturian, A. G. Theory of structural transformations in solids https://www.osti.gov/biblio/5821133 (1983).

Thompson, P., Reidinger, F., Reilly, J. J., Corliss, L. M. & Hastings, J. M. Neutron diffraction study of α-iron titanium deuteride. J. Phys. F Met. Phys. 10, 57–59 (1980).

Thompson, P. et al. Neutron diffraction study of β iron titanium deuteride. J. Phys. F Met. Phys. 8, 75–80 (1978).

Buchenau, U., Schober, H. R., Welter, J. M., Arnold, G. & Wagner, R. Lattice dynamics of Fe0.5Ti0.5. Phys. Rev. B 27, 955–962 (1983).

Westlake, D. G. Application of a geometric model to the hydrides of FeTi. J. Mater. Sci. 19, 316–326 (1984).

Liu, L. M., Wang, S. Q. & Ye, H. Q. First-principles study of metal/nitride polar interfaces: Ti/TiN. Surf. Interface Anal. 35, 835–841 (2003).

Santhy, K. & Hari Kumar, K. C. Thermodynamic modelling of magnetic laves phase in Fe-Ti system using first principle method. Intermetallics 128, 106978 (2021).

Łodziana, Z. Surface properties of LaNi5 and TiFe-future opportunities of theoretical research in hydrides. Front. Energy Res. 9, 1–9 (2021).

Da Silva, J. L., Stampfl, C. & Scheffler, M. Converged properties of clean metal surfaces by all-electron first-principles calculations. Surf. Sci. 600, 703–715 (2006).

Liu, W., Li, J. C., Zheng, W. T. & Jiang, Q. NiAl (110) Cr (110) interface: a density functional theory study. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 73, 1–7 (2006).

Porter, D. A., Easterling, K. E. & Sherif, M. Y. Phase Transformations in Metals and Alloys 3rd edn (CRC Press, 2009).

Schober, T. The iron-titanium—hydrogen system: a transmission electron microscope (TEM) study. Scr. Metall. 13, 107–112 (1979).

Scheiber, D. et al. Morphology of fe2al5 particles and the interface to wc coating in the context of hot-dip galvanizing: an ab initio study. J. Alloy. Compd. 824, 153854 (2020).

Leitner, S. et al. Analysis of shape, orientation and interface properties of Mo2C precipitates in Fe using ab-initio and finite element method calculations. Acta Mater. 204, 116478 (2021).

Shi, R., Ma, N. & Wang, Y. Predicting equilibrium shape of precipitates as function of coherency state. Acta Mater. 60, 4172–4184 (2012).

Hull, D. & Bacon, D. J. Introduction to Dislocations 5th edn, Ch. 4 (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2011).

Heo, T. W., Tang, M., Chen, L. Q. & Wood, B. C. Defects, entropy, and the stabilization of alternative phase boundary orientations in battery electrode particles. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1501759 (2016).

Cogswell, D. A. & Bazant, M. Z. Coherency strain and the kinetics of phase separation in LiFePO 4 nanoparticles. ACS Nano 6, 2215–2225 (2012).

Lee, S.-Y. et al. Orientation relationship between TiFeH and TiFe phases in AB-type Ti-Fe-V-Ce hydrogen storage alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 983, 173943 (2024).

Chen, L.-Q. Phase-field models for microstructure evolution. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 32, 113–140 (2002).

Boettinger, W. J., Warren, J. A., Beckermann, C. & Karma, A. Phase-field simulation of solidification. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 32, 163–194 (2002).

Gránásy, L. et al. Phase field theory of crystal nucleation and polycrystalline growth: a review. J. Mater. Res. 21, 309–319 (2006).

Emmerich, H. Advances of and by phase-field modelling in condensed-matter physics. Adv. Phys. 57, 1–87 (2008).

Moelans, N., Blanpain, B. & Wollants, P. An introduction to phase-field modeling of microstructure evolution. Calphad 32, 268–294 (2008).

Steinbach, I. Phase-field models in materials science. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 17, 073001 (2009).

Wang, Y. & Li, J. Phase field modeling of defects and deformation. Acta Mater. 58, 1212–1235 (2010).

Benyelloul, K. et al. The effect of hydrogen on the mechanical properties of FeTi for hydrogen storage applications. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 39, 12667–12675 (2014).

sheng NONG, Z., chuan ZHU, J., ling YU, H. & hong LAI, Z. First principles calculation of intermetallic compounds in feticonivcrmncual system high entropy alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 22, 1437–1444 (2012).

Zhu, L.-F. et al. Ab initio based study of finite-temperature structural, elastic and thermodynamic properties of feti. Intermetallics 45, 11–17 (2014).

Liebertz, J., Stähr, S. & Haussühl, S. Growth and properties of single crystals of FeTi. Krist. Tech. 15, 1257–1260 (1980).

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible by the NZMat4H2Sto project, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). Kai Sellschopp was partly funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—506703280. Part of this study was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. The work by LLNL was supported by the Hydrogen Storage Materials Advanced Research Consortium (HyMARC) of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ebert Alvares: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Software, Data curation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Kai Sellschopp: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Bo Wang: Validation, Writing—review & editing. ShinYoung Kang: Validation, Writing—review & editing. Thomas Klassen: Resources. Brandon C. Wood: Resources, Funding acquisition. Tae Wook Heo: Supervision, Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing. Paul Jerabek: Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing, Project Administration. Claudio Pistidda: Resources, Writing—review & editing, Project Administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alvares, E., Sellschopp, K., Wang, B. et al. Multiscale modeling of metal-hydride interphases—quantification of decoupled chemo-mechanical energies. npj Comput Mater 10, 249 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01424-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01424-1