Abstract

To advance the development of high-strength polycrystalline metallic materials towards achieving carbon neutrality, it is essential to design materials in which the atomic level control of general grain boundaries (GGBs), which govern the material properties, is achieved. However, owing to the complex and diverse structures of GGBs, there have been no reports on interatomic potentials capable of reproducing them. This accuracy is essential for conducting molecular dynamics analyses to derive material design guidelines. In this study, we constructed a machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) with density functional theory (DFT) accuracy to model the energy, atomic structure, and dynamics of arbitrary grain boundaries (GBs), including GGBs, in α-Fe. Specifically, we employed a training dataset comprising diverse atomic structures generated based on crystal space groups. The GGB accuracy was evaluated by directly comparing with DFT calculations performed on cells cut near GBs from nano-polycrystals, and extrapolation grades of the local atomic environment based on active learning methods for the entire nano-polycrystal. Furthermore, we analyzed the GB energy and atomic structure in α-Fe polycrystals through large-scale molecular dynamics analysis using the constructed MLIP. The average GB energy of α-Fe polycrystals calculated by the constructed MLIP is 1.57 J/m2, exhibiting good agreement with experimental predictions. Our findings demonstrate the methodology for constructing an MLIP capable of representing GGBs with high accuracy, thereby paving the way for materials design based on computational materials science for polycrystalline materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increasing demand for the development of high-strength metallic materials to achieve carbon neutrality. For example, within the field of steel materials, increasing the strength of steel used for automotive steel plates can reduce CO2 emissions by lightening the vehicle body. Thus, development of high-strength steels is being pursued intensively1,2,3,4,5,6. Most metallic materials are polycrystalline, and therefore, contain grain boundaries (GBs). GBs have a significant influence on manufacturability and material properties, either directly or indirectly, through the formation of microstructures. However, enhancing material strength increases susceptibility to GB embrittlement, a phenomenon characterized by the degradation of material properties and manufacturability. This occurs due to cracking at GBs caused by the GB segregation of certain alloying elements or impurity atoms7,8,9,10. Therefore, the suppression of hydrogen embrittlement5,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, liquid metal embrittlement (LME)19,20,21,22,23,24, and red hot embrittlement25,26,27,28,29, all of which entail cracking at GBs, is a significant issue in the development of high-strength steels. Consequently, there is a critical need to design materials capable of suppressing the degradation of material properties and manufacturability associated with GB cracking.

Recent reports indicate that controlling the GB segregation of alloying and impurity elements can mitigate hydrogen embrittlement and LME in high-strength steels5,11,21,30,31. Therefore, obtaining material design guidelines to suppress GB cracking necessitates a quantitative understanding of the extent of GB segregation of diverse solute elements. This understanding should account for their content, heat treatment process, and GB character.

To acquire such knowledge, GB segregation using highly symmetric GBs that can be treated by density functional theory (DFT), i.e., GBs with small Σ values, has been intensively studied32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. These studies have clarified that the amount of GB segregation of solute elements is strongly affected by the local atomic structure of each site constituting the GB. Specifically, factors such as Voronoi (or occupied) volume32, coordination number, and interatomic distance play crucial roles34,37. However, such GB cracking primarily occurs at so-called general GBs (GGBs), which constitute most GBs in polycrystals and lack specific symmetry. Recent studies have revealed that predicting GB segregation in polycrystalline materials can be difficult to predict using highly symmetric GBs, which are amenable to analysis using DFT. This difficulty arises because of the diverse array of local atomic structures present within these boundaries42. Consequently, studying only highly symmetric GBs that can be analyzed using DFT is insufficient to obtain the knowledge necessary to control GB segregation.

Therefore, numerous studies have recently investigated GB segregation in GGBs using nano-polycrystalline models and interatomic potentials, such as embedded atom method (EAM) and modified EAM (MEAM) potentials43,44,45,46,47,48,49. However, interatomic potentials such as EAM and MEAM are rarely fitted to GBs. Consequently, they cannot accurately replicate the intricate local atomic structures found at stable GBs that affect GB segregation and the energies and dynamics of each atom that determine them. For example, the GB segregation energy of transition metal alloying elements in Fe varies approximately in proportion to the Voronoi volume of the segregation site. Moreover, the GB segregation energy exerts an exponential influence on the extent of GB segregation. Therefore, even a small change in Voronoi volume results in a significant difference in segregation levels. Furthermore, in α-Fe, interatomic potentials such as EAM and MEAM have been shown to significantly underestimate the GB energy of symmetric tilt GBs in pure Fe relative to DFT values50. Therefore, the local atomic structures at stable GBs that affect GB segregation and the kinetics near GBs that determine them also differ significantly from DFT.

In recent years, highly accurate machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have been constructed51,52, which have also been applied to the study of GBs. For example, Yokoi et al. have demonstrated that the GB energy of Al and its temperature dependence can be calculated with DFT accuracy using a neural network interatomic potential (NNIP)53. Various MLIPs for α-Fe have also been constructed54,55,56,57,58,59,60 since the development of the Gaussian approximate potential (GAP)61 in 2018. For example, Mori et al. have created an NNIP for α-Fe that reproduces the stability of dislocation structures with an accuracy comparable to that of DFT62. In particular, a NNIP for Fe–H explicitly includes symmetric tilt GBs with small Σ values in the training data and provides accuracy comparable to that of DFT for the GB energy of symmetric tilt GBs63.

However, there are no reports on interatomic potentials capable of reproducing the local atomic structure and GB energies of GGBs in metallic materials, as well as the dynamics near GBs that determine them, with DFT accuracy. These aspects are essential for the design of future metallic materials. MLIP is recognized to be inaccurate in extrapolated regions64, and its accuracy for GGBs with more complex and diverse atomic structures warrants thorough testing. This holds even if symmetric tilt GBs are included in the training data. However, GGBs are characterized by five degrees of freedom and comprise diverse and complex atomic structures65. Therefore, performing DFT calculations exhaustively on all GGBs, explicitly incorporating them as training data to construct interatomic potentials, and evaluating the accuracy of these potentials with respect to GGBs are challenging.

In this study, rather than explicitly incorporating GGBs into the training dataset, we employed a training dataset generated through a method recently proposed by Poul et al.66. This method mechanically generates various atomic structures based on crystal space groups. The moment tensor potential (MTP) was selected as the MLIP because of its excellent balance between computational cost and accuracy67,68. The accuracy of the MLIP for GGBs was verified through direct comparison with DFT calculations for cells cut out in the vicinity of GBs using randomly oriented nano-polycrystals. These nano-polycrystals provided a comprehensive sampling of the atomic environment within GGBs in polycrystals. Additionally, the accuracy was evaluated through extrapolation grades based on active learning methods for the entire nano-polycrystal. These verifications demonstrated that the constructed MLIP can calculate the atomic structure, energy, and dynamics of arbitrary GBs, including GGBs, with a level of accuracy comparable to that of DFT. As an application of the MLIP, the average GB energy of α-Fe polycrystals, which is an important yet challenging property to measure, was calculated. Finally, the properties of GGBs in α-Fe polycrystals were analyzed at the atomic level and their relationship with GB segregation discussed. Consequently, we clarified that the MLIP constructed in this study is valuable for quantitatively predicting GB segregation at GGBs.

Methods

Details of calculations using DFT and interatomic potentials

Spin-polarized electronic structure calculations and structural optimization were performed, using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) with the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method69,70 within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) framework, utilizing Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) parametrization71. A pseudopotential was employed where the 4s and 3d electrons were considered as valence electrons. This approach is consistent with the one used in the previous MLIP study63. These calculations were employed to build the training dataset and verify the accuracy of the interatomic potentials. The cutoff energy for the plane-wave basis set was set to 520 eV. The k-point mesh for each atomic structure was set to an accuracy equivalent to 18 × 18 × 18 for the α-Fe conventional unit cell using Monkhorst-Pack k-mesh72. The k-point mesh and cutoff energy were finer and higher, respectively, compared to those in the previous study63. The Methfessel–Paxton smearing method73 with a width of 0.1 eV was employed. The atomic positions were relaxed until reaching energy and force convergence values of 10−6 eV and 10−2 eV/Å, respectively. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) based on the Parrinello–Rahman dynamics with the Langevin thermostat74,75 was performed to generate training datasets, as described in “Training datasets” section, and verify the accuracy of the interatomic potentials. Both NVT and NPT conditions were used with a time step of 2 fs.

All calculations using interatomic potentials were conducted using LAMMPS76, while OVITO77 was used for visualizing the atomic structure. Additionally, calculations involving the quasi-harmonic approximation were performed using PHONOPY78.

Training datasets

Table 1 lists the training datasets, which comprise two types. The first dataset, referred to as the domain expertize (DE) dataset hereafter, considers the basic properties and lattice defects of α-Fe and was manually created. The second dataset, referred to as the RANDSPG dataset hereafter, is based on atomic structures mechanically generated by the RANDSPG algorithm79, mainly for reproducing GGBs66.

For the RANDSPG dataset, the method used to construct the Mg training dataset66 was modified and applied to α-Fe. The MTP constructed using this training dataset has been demonstrated to accurately reproduce physical properties and lattice defect energies, such as symmetric tilt GBs for low Σ values, for Mg. Notably, this is achieved even though the corresponding atomic structures are not explicitly included in the training dataset. Specifically, we first used the RANDSPG algorithm79 to create the basic structure for constructing the training dataset. The main input parameters for generating the atomic structure are the maximum number of atoms, crystal space group to be considered, and allowable atomic volume per atom. Building on the study on Mg66, 2482 basic structures (hereafter referred to as RANDSPGs) were generated. These structures were created with a maximum of 10 atoms, encompassing all crystal space groups, and allowing a tolerance of ±10% of the equilibrium lattice constant for the atomic volume per atom. These basic structures were then subjected to stepwise structural relaxation: (1) volume-only relaxation (VOLMIN), (2) cell shape-only relaxation with constant volume (CELLMIN), and (3) atomic position relaxation (INTMIN). Each of these structures was then used as a candidate training dataset. In addition, the atomic structure of INTMIN was disturbed by (1) random triaxial strain (TRIAX, up to 80%), (2) a combination of random shear strains (SHEAR, up to 80%), and (3) random displacements of atoms combined with a small random strain tensor (RATTLE, 0.5 Å mean displacement and up to 5% strain). These modified structures were also included as candidates for the training dataset. DFT calculations were performed on these structures to construct the training dataset. However, owing to the high-spin degrees of freedom of Fe, many atomic structures with nonmagnetic, low-spin, and spin-flip magnetic states were obtained. Consequently, we supposed that including these structures in the training data would hinder the attainment of an MTP capable of reproducing ferromagnetic α-Fe with high accuracy. Therefore, for the training dataset, we exclusively included structures possessing magnetic moments with the same direction and values exceeding 1.5 μB. This value corresponds to the magnitude of stable magnetic moments in which the body-centered cubic (bcc), face-centered cubic (fcc), hexagonal close-packed (hcp), and simple cubic structures of Fe do not transition to the nonmagnetic state. The number of atomic structures and atomic environments in the final RANDSPG dataset was comparable to those included in the training dataset for Mg in previous studies66, comprising 17460 structures and 117146 atomic environments.

A DE dataset was added to increase the accuracy of the physical properties of α-Fe and lattice defects such as self-interstitial atoms (SIAs). This also serves to compensate for the compressed structure, which renders the magnetic moment unstable and is preferentially excluded in the selection process of the RANDSPG dataset described above. Specifically, AIMD was conducted on 3 × 3 × 3 supercells of α-Fe at 300, 600, 1000, 1400, 2000, and 3000 K under the NPT ensemble. AIMD was also performed at 300, 600, 1000, 1400, 2000, and 3000 K under the NVT ensemble for 3 × 3 × 3 supercells of α-Fe, with lattice constants varying within ±2.5% from the equilibrium lattice constant. In addition, AIMD simulations were conducted at 300, 600, 1000, 1400, 2000, and 3000 K under the NPT ensemble for a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell of α-Fe containing a single vacancy. These AIMD runs were run for 500 steps, and the atomic structures were extracted from these AIMDs every five steps and included in the training dataset. Snapshots of the structural relaxation process of the structure containing an SIA were also added to the training dataset.

Finally, the two datasets were combined to create a training dataset for building interatomic potentials consisting of 19950 structures and 267188 atomic environments. In particular, the RANDSPG dataset contains a relatively large number of structures but consists of at most 10 atoms. Considering that, for single-element systems, the computational cost of DFT is proportional to the cube of the number of atoms, it is noteworthy that the computational cost of constructing these training datasets is very small. Specifically, the computational cost of obtaining the RANDSPG dataset is comparable to that of performing 500-step AIMD simulations at 300, 600, and 1000 K using the 3 × 3 × 3 supercells of α-Fe in the DE dataset.

Construction of MTP

In this study, the MLIP was constructed using the MTP formalism67,68. The MTP can represent various atomic environments through angle-dependent many-body interactions, expressed as tensor products of atomic displacements. Moreover, it has no transcendental functions and relies solely on polynomial arithmetic operations, thereby significantly reducing the computational cost. Owing to these advantages, in certain systems, MTP can achieve accuracy levels comparable to those of GAP, which is considered one of the most accurate MLIPs, in less than a tenth of the computation time80. A template of level 22 potentials was employed to construct the MTP. Supplementary Table 1 shows the calculation accuracy for each level of the MTP with respect to the physical properties and lattice defect formation energies. The template of level 22 potentials was selected as the one with the highest calculation accuracy among those for which learning had converged correctly. The maximum cutoff radius was set to 6.5 Å, consistent with the NNIP for Fe–H63, and training was conducted using the MLIP-3 package80. The MTP constructed in this study can be accessed via the URL provided in the “Data availability” section.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, the RMSEs of energy for the training and validation datasets were 14.11 and 14.79 meV/atom, respectively. The RMSE of atomic force was 71.88 meV/Å for the training dataset and 75.42 meV/Å for the validation dataset. The RMSE of energy was approximately fourfold larger than that of the previously reported NNIP of Fe–H63. However, this discrepancy can be attributed to the diverse range of atomic structures present in the RANDSPG dataset, a trend also observed in the construction of the MTP for Mg66. Indeed, as shown in Table 1, the RMSE for the DE dataset is comparable to the NNIP of Fe–H. Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2 demonstrate that the constructed MTP reproduced the lattice parameter, elastic modulus, and phonon dispersion of α-Fe, along with the defect energies for SIAs and vacancy defects with the same accuracy as that of the NNIP. In addition, the two-dimensional energy profiles of screw dislocation core positions62 and generalized stacking fault energy surfaces81, crucial for analyzing plastic deformation and crack propagation behavior, were also reproduced with very good accuracy. These results demonstrate that the fitting process was performed correctly and suggest excellent transferability of the MTP, as discussed in “Results and discussion” section.

Method for evaluating the accuracy of interatomic potentials for GGBs

In this study, we evaluated the accuracy of the constructed MTP for GGBs using GBs in nano-polycrystals with random orientations obtained by Voronoi tessellation82 and relaxation through molecular dynamics calculations. Detailed analysis of the GB structure of nano-polycrystals obtained through this method suggests that the GB structure is similar to that of general polycrystals with grain sizes larger than micrometer dimensions83. The time evolution of the average grain size of nano-polycrystals prepared by this method via annealing exhibits similar growth behavior as polycrystals with grain sizes larger than micrometer dimensions, growing at a rate proportional to the square root of time84. Given grain growth behavior is strongly influenced by the nature of GBs85, these results suggest that the GBs of nano-polycrystals created with Voronoi tessellation are similar to those found in common polycrystals. Furthermore, Wagih et al. demonstrated that the histogram of GB segregation energies, calculated for nano-polycrystals generated via Voronoi tessellation, exhibits little change for a 15 nm cubic polycrystalline model consisting of eight grains, even as the number of nano-polycrystalline grains and their model size increase46. They demonstrated that nano-polycrystals created through Voronoi tessellation could effectively represent the diverse local atomic environments found in real polycrystals with actual grain sizes in the micrometer range, since the GB segregation energy at each site depends on the local atomic environment of the host metal around the solute atoms42. The energy and force of each atom of the host metal are determined by the local atomic environment as well as GB segregation. Therefore, if the constructed MTP can accurately reproduce the local atomic environment in nano-polycrystals created through Voronoi tessellation, it should be capable of reproducing the local atomic environments of GBs, or GGBs, in polycrystals.

We evaluated the accuracy of the MTP for GGBs in two ways of using nanocrystalline polycrystals created via Voronoi tessellation. The first method involved directly comparing energies and atomic forces by conducting DFT calculations on numerous DFT-calculable regions selected from the GBs within the nano-polycrystals, obtained by molecular dynamics relaxation using the constructed MTP. However, while this method provides direct verification, the computational cost makes it impractical to evaluate the accuracy of the entire nano-polycrystal. As a second method to address this limitation, all local atomic environments constituting the nano-polycrystal were evaluated. This involved calculating extrapolation grades that can numerically determine whether the constructed MTP is in an interpolated region where high accuracy can be expected or an extrapolated region where accuracy is reduced80. Validation of the transferability of the constructed potentials, based on the evaluation of extrapolation grades, has also been employed in previous studies66. While not a direct accuracy assessment, this method is relatively computationally inexpensive because it relies on pre-constructed MTPs, enabling evaluation for all atomic environments within the nano-polycrystal.

The initial structure of the nano-polycrystals was generated using Atomsk82 with Voronoi tessellation to create polycrystals with random orientations. The structural relaxation of the nano-polycrystals was based on the method outlined by Van Swygenhoven et al.83. This involved initially relaxing the cell size and atomic positions using the conjugate gradient method, followed by annealing for 0.2 ns at 300 K in the NPT ensemble. Subsequently, the system was cooled from 300 to 0.1 K before performing another relaxation step to adjust the cell size and atomic positions using the conjugate gradient method. The annealing time was set as the time for sufficient convergence of the obtained GB energy. Eight grains were included in the nano-polycrystals, following the methodology outlined by Wagih et al. in their study of GB segregation of Mg in Al using EAM46. The initial dimensions of the nano-polycrystals were set to 28.3 × 28.3 × 28.3 nm3. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, the local atomic environment in nano-polycrystals created under these conditions is largely independent of the random seeding of the initial structure creation and the expansion of the model size. Specifically, the atomic environment near the GBs remains unaffected by the grain size extension and random seeding of initial structure creation once the model size exceeds 22.6 nm or an average grain size of 9.0 nm. Verification of an increasing the number of grains while maintaining this average grain size was challenging due to computational cost constraints. Nevertheless, the minimal impact of random seeding, i.e., the orientation of the grains, on the local atomic environment of the GB suggests that increasing the number of grains from eight has little effect on the atomic environment near the GBs.

Evaluating the accuracy of interatomic potentials for GGBs through direct comparison with DFT

The method of comparison using DFT calculations is illustrated in Fig. 1. For this analysis, we used a nano-polycrystal with initial cell dimensions of 28.3 × 28.3 × 28.3 nm3, hereafter denoted as (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal. Specifically, we utilized two structures: one with a dimension of (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal during annealing at 0.1 ns and subsequent relaxation, as described in the previous section. From all the GBs in each nano-polycrystal, 64 regions with dimensions of 15.0 × 15.0 × 15.0 Å3 (~250 atoms) were cut out as calculation cells. Given polycrystals typically contain GB triple junctions, we also cut out 33 regions measuring 15.0 × 15.0 × 15.0 Å3 from the GB triple junctions in each nano-polycrystal as calculation cells. Periodic boundary conditions were applied to the cells, and if the distance between atoms was less than 2.0 Å, one of the atoms was removed from the cell boundary. This threshold was chosen to prevent atoms from being too close to each other when creating the initial GB structure, based on previous studies of Fe GBs using the EAM43,44,45. As depicted in Fig. 1c, the boundary of the calculation cell, influenced by the periodic boundary conditions, exhibits a structure like a general GB. Consequently, the energy of the system differs from that which would be observed if this region existed within the nano-polycrystal. Nevertheless, achieving sufficient accuracy for these calculation cells suggests the potential to accurately compute the energies of atoms proximal to GBs and GB triple junctions. Energy comparisons were performed as per atom energies for the extracted calculation cells. The atomic forces at the boundaries of the calculation cell also differ from those in the nano-polycrystal. However, the atomic forces near the center of the calculation cell, which is sufficiently far from the cell boundaries, are consistent with those observed in the nano-polycrystal. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 5, the atomic forces acting on atoms within 4.0 Å of the center of the calculation cell are maintained within a 10% error margin. Therefore, for the comparison of the atomic forces near the general GB, we compared the results of the DFT and interatomic potential calculations for atoms within 4.0 Å of the center of the calculation cell and in the one-atomic layer region (2.46 Å) from the GB center. For atoms near the GB triple junctions, DFT and MTP calculations were compared for atoms within 4.0 Å of the calculation cell center and 2.46 Å from the nearest and second nearest GBs, respectively. The GB center is defined as a Voronoi polyhedron when the initial structure is created by Voronoi tessellation. Remarkably, during annealing at 300 K and subsequent relaxation via the conjugate gradient method, the relative positions of the GBs exhibited minimal movement, despite changes in the cell size. For comparison, we also evaluated the NNIP for Fe–H63 using the same methodology. This MLIP utilizes symmetric tilt GBs of α-Fe as the training data. Additionally, a deep potential (DP) for Fe-H, developed using the same dataset, is also proposed60. This DP offers improved computational speed by using GPUs. However, we chose this NNIP owing to its superior computational accuracy for the GB energy of symmetric tilt GBs60. Currently, no other MLIPs exist that use symmetric tilt GBs of α-Fe as training data. It is difficult to make a fair comparison between the MTP and the NNIP because the configuration of the interatomic potentials and the training data are both different. Nevertheless, a comparison with the NNIP, which is currently considered to have the best accuracy for α-Fe GBs, is worthwhile to demonstrate the usefulness of the obtained MTP. Similarly, the MEAM86 and EAM87 were evaluated for accuracy using this method. These two interatomic potentials are identical to those used for comparison in previous studies50. The nano-polycrystals obtained using the MTP were consistently used in the comparison of the interatomic potentials other than the MTP with the DFT. This approach allows a comparison with DFT using the same atomic structure. The purpose here is to validate the accuracy against DFT, and as shown in “Average GB energy of α-Fe polycrystals using the constructed MTP” section, the MTP used here is the most reasonable choice because it provides the closest results to DFT. The use of structures relaxed with each interatomic potential would introduce differences in atomic structures and atoms, making direct comparisons difficult. Additionally, performing DFT calculations for cut-out cells from each structure relaxed with each interatomic potential would demand significant computational resources. For further discussion on the validity of consistently using nano-polycrystals obtained with the MTP, please refer to Supplementary Note 5.

a Two base structures for comparison: (28.3 nm)3 polycrystalline structure annealed at 300 K for 0.1 ns and structure relaxed using the conjugate gradient method after annealing. b Magnified view of the vicinity of the general grain boundary (GGB) of the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal after relaxation. c Cross-section of a periodic boundary cell for density functional theory (DFT) extracted from the vicinity of the GGB. The colors in these figures represent the energy of each atom, and the energy reference is the energy of Fe atoms in the perfect crystal. A total of 64 regions near the GGB and 33 regions near the grain boundary (GB) triple junction were cut out of the calculation cell for the DFT calculation. Atomic forces for atoms within 4.0 Å of the center of the calculation cell and in the one-atomic layer region (2.46 Å) from the GB center or GB triple junction center were compared.

To provide a relative interpretation of the accuracy evaluated for GGBs, the GB energies, and atomic forces acting on atoms within 2.46 Å of the GB center during annealing were also compared through DFT calculations for eight <110> and <100> symmetric tilt GBs with Σ values ranging from 3 to 11, which can be treated by DFT calculations. In addition, we investigated whether the stable GB structure obtained by DFT relaxation can be reproduced by the interatomic potentials. For both DFT and interatomic potential calculations of GB energies, several initial structures were created with one grain rigidly shifted parallel to the GB, and the cell sizes and atomic configurations were subsequently relaxed. In these interatomic potential calculations, OpenKIM88 was employed. AIMD was conducted at 300, 600, and 1000 K in the NVT ensemble for eight stable structures of symmetric tilt GBs derived from DFT. The AIMDs were run for 500 steps with a time step of 2 fs. For the atomic structures during annealing after 100 steps, when the system had reached the target temperature, the atomic forces acting on atoms in the region within 2.46 Å of the GB center were calculated using interatomic potentials and compared with those obtained from DFT calculations.

Evaluating the accuracy of the MTP for GGBs through extrapolation grades based on active learning methods

To evaluate the accuracy of the MTP for GGBs through exploitation grade calculations, the structures of the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal at 0.1 ns and after relaxation were used, alongside direct comparisons with DFT calculations. For all atoms constituting these two structures, the extrapolation grade of the local atomic environment for the active learning method recently implemented in MLIP-3 was evaluated80. In the extrapolation grade calculations, extrapolation grades were evaluated for nano-polycrystals annealed at 600 and 1000 K for 0.1 ns in addition to those at 300 K. For details on extrapolation grades, see ref. 80. Briefly, an atom with an extrapolation grade between 0 and 1 falls into the “interpolation region” for the constructed interatomic potentials, which guarantees high calculation accuracy. Extrapolation grades between 1 and 2 indicate the “accurate extrapolation” region, while those between 2 and 10 fall into the “reliable extrapolation” region. Structures containing atoms in this last range are additionally labeled by DFT calculations during the active learning process to indicate insufficient learning of their atomic environment. If the extrapolation grade of an atom exceeds 10, it is considered to be in the “dangerous extrapolation” region and the learning process is terminated80. Thus, an extrapolation grade of 2 or less for all atoms in the annealed and relaxed nano-polycrystals indicates that the obtained interatomic potentials are sufficiently learned for the entire polycrystal. Therefore, even if active learning was performed, no additional training would be necessary, and high accuracy is expected.

Analysis of GB energy and atomic structure in α-Fe polycrystals

The determination of the GB energy of GGBs in polycrystalline metallic materials remains a significant area of research. To date, these energies have been determined through experimentation89. Therefore, as an application of the MTP constructed in this study, we calculated the average GB energy of α-Fe polycrystals using the nano-polycrystals described in “Method for evaluating the accuracy of interatomic potentials for GGBs” section. We then compared this energy to those of GGBs calculated based on experimental data. As a comparison, the average GB energies of α-Fe polycrystals were calculated using the NNIP, MEAM, and EAM as well. Additionally, we analyzed the properties of GGBs in α-Fe polycrystals obtained using the MTP at the atomic level and discussed their relationship with GB segregation.

The area of the GB required for calculating GB energies was determined by correcting the area of the Voronoi polyhedron, which was utilized to generate the initial structure of the nano-polycrystal, for the change in cell size before and after relaxation. Notably, during annealing at 300 K and subsequent relaxation through the conjugate gradient method, the relative positions of the GBs exhibit minimal movement, despite changes in the cell size. However, the average GB energy may strongly depend on the number of grains (or the effect of GB character) and the size of the grains. Therefore, fixing the number of grains at eight, we calculated the average GB energy for nano-polycrystals with cell sizes ranging from 5.66 × 5.66 × 5.66 nm3 (20 times the lattice constant of Fe for a side length) to 28.3 × 28.3 × 28.3 nm3 (100 times the lattice constant of Fe for a side length). This allowed us to investigate the dependence of the average GB energy on the grain size. For each cell size, the dependence on GB character was further evaluated. This was achieved by calculating the average GB energy of nano-polycrystals for three cases, in which only the random seed was varied when creating the initial nano-polycrystal structure by Voronoi tessellation.

Results and discussion

Accuracy of the MTP for symmetric tilt GBs

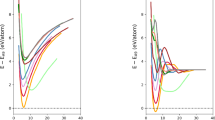

To provide a relative interpretation of the accuracy for GGBs, we first present the accuracy for symmetric tilt GBs, where the GB energy is well-defined and a direct comparison with the DFT calculations is possible for both energy and atomic forces. Figure 2 depicts the GB energies of the symmetric tilt GBs, obtained through relaxation using both DFT calculations and interatomic potentials. On average, the difference between the GB energies of the eight symmetric tilt GBs calculated with the constructed MTP and those calculated with DFT is 0.037 J/m2. This result indicates that the MTP reproduces the DFT values with high accuracy. In particular, the MTP exhibits a level of high accuracy comparable to that of the NNIP, which explicitly incorporates training data from Σ3(112), Σ3(111), Σ5(210), and Σ5(310). Conversely, the GB energies calculated using the MEAM and EAM greatly underestimate those calculated using DFT.

Figure 3 presents the atomic forces near the GB center (within the one-atomic layer region from the GB center) for eight symmetric tilt GBs. The calculations were performed using both DFT and interatomic potential calculations, with GBs annealed at 300, 600, and 1000 K using AIMD under the NVT ensemble. Figure 3a displays the collective atomic forces acting on atoms within the eight symmetric tilt GBs. In contrast, Fig. 3b and c showcase the atomic forces at the symmetric tilt GBs calculated using MTP and NNIP, respectively, for each of the eight GBs. Notably, the annealing structures of Σ3(112), Σ3(111), Σ5(210), and Σ5(310) are explicitly included in the training data for the NNIP. The MTP demonstrates higher accuracy compared to the NNIP, EAM, and MEAM across both GBs and all annealing temperatures. For example, the RMSE of the atomic force for the eight symmetric tilt GBs at 300 K is 82.4 meV/Å. Notably, upon focusing on the accuracy for each GB, MTP reproduces the DFT for the GBs that are explicitly included in the NNIP training dataset with the same high accuracy as that of the NNIP. Additionally, for GBs absent in the NNIP training dataset, the MTP consistently exhibits higher accuracy than the NNIP. In particular, NNIP displays a particularly large error for structures annealing in Σ9(114) and Σ11(113), which are not included in the training dataset. Supplementary Fig. 6 shows the finite temperature GB energies for Σ3(111) and Σ9(114) calculated within the harmonic approximation using the MTP and NNIP. The MTP reproduces the DFT results for both GB energies, while the NNIP significantly underestimates the GB energy of Σ9(114). This result clearly shows that even though the stable structure of GBs and their GB energies can be calculated with good accuracy, the error in the dynamics and stability of GBs at high temperatures may be substantial.

Forces calculated using density functional theory (DFT) and interatomic potentials, on atoms near the grain boundary (GB) center of symmetric tilt GBs during annealing at 300, 600, and 1000 K in ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) under NVT ensemble. a Collective atomic forces on the atoms in eight symmetric tilt GBs. Atomic forces at symmetric tilt GBs calculated using the (b) moment tensor potential (MTP) and (c) neural network interatomic potential (NNIP) for each of the eight GBs.

In summary, the MTP constructed in this study can accurately calculate both the GB energy of symmetric tilt GBs and their atomic forces during annealing, without explicitly including them in the training data. This suggests that the constructed MTP exhibits excellent accuracy for GGB stable structures, as well as their associated energies and dynamics across a wide temperature range. However, the reason why the MTP shows better accuracy than the NNIP is unclear due to the different interatomic potential configurations and training data; this warrants further investigation in future work.

Accuracy of the MTP for GGBs

Figure 4a and b depict the energies and atomic forces near the GGB and GB triple junctions, respectively. These calculations employed cut-out calculation cells from a (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal annealed at 300 K for 0.1 ns via MTP, using DFT and interatomic potentials. Considering that the energy basis varies depending on the interatomic potentials, the energy was compared by measuring the change from the energy of an atom of α-Fe in the bulk of the nano-polycrystal calculated (corresponding to the energy of a single Fe atom in a perfect crystal with a lattice constant of 2.830 Å) with each interatomic potential. Each energy plot represents the average energy of Fe atoms in the extracted cells. Here, 2.830 Å represents the equilibrium lattice constant of α-Fe in DFT, MTP, and NNIP. Notably, the periodic boundary conditions result in a GB-like defect structure near the boundary of the calculation cell, which differs from that observed in the nano-polycrystal. The RMSEs of the energy and the atomic force for the general GB in the constructed MTP are 2.17 meV/atom and 81.05 meV/Å, respectively. The RMSE of the atomic force on the general GB is comparable to that observed during annealing at 300 K for symmetric tilt GBs, for which the GB energy can be accurately calculated. This indicates that MTP exhibits high calculation accuracy for GGBs. The RMSEs of the energy and atomic force for the constructed MTP for GB triple junctions are 2.21 meV/atom and 86.76 meV/Å, respectively, which are also comparable to those for GGBs. In particular, the force and energy RMSEs for both the general GB and GB triple junctions were approximately half those obtained using NNIP. These results clearly demonstrate that the constructed MTP accurately reproduces the dynamics near the general GBs and GB triple junctions of nano-polycrystals at 300 K.

Energies and atomic forces near the (a) general grain boundary (GGB) and (b) grain boundary (GB) triple junctions, calculated using cut-out calculation cells from a (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal annealed at 300 K for 0.1 ns using moment tensor potential (MTP), through density functional theory (DFT) and interatomic potentials. The calculation cells were cut out one by one from the 64 GBs and 33 GB triple junctions in the nano-polycrystal.

Figure 5a and b depict the energies and atomic forces near the GGB and GB triple junctions, respectively. These calculations utilized cut-out calculation cells from a (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal annealed at 300 K and relaxed via the conjugate gradient method using MTP, through DFT and interatomic potentials. The RMSEs of the energy and atomic force for the constructed MTP for a GGB are 2.44 meV/atom and 80.34 meV/Å, respectively. Given these are the forces acting on the atoms in the nano-polycrystal after relaxation, the atomic forces tend to approach zero. The RMSEs of the energy of the GB triple junctions and atomic force in the constructed MTP were determined to be 2.44 meV/atom and 81.54 meV/Å, respectively. These results indicate that nano-polycrystals can be relaxed using MTP with good accuracy, and stable structures and their energies can be obtained with DFT accuracy.

Energies and atomic forces near the (a) general grain boundary (GGB) and (b) grain boundary (GB) triple junctions, calculated using cut-out calculation cells from a (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal fully relaxed using the moment tensor potential (MTP), through density functional theory (DFT) and interatomic potentials. The calculation cells were cut out one by one from the 64 GBs and 33 GB triple junctions in the nano-polycrystal.

Owing to the cost of DFT calculations, these described calculations are limited to a portion of the nano-polycrystal. Therefore, to investigate the accuracy across the entire nano-polycrystal, encompassing all local atomic environments in a typical polycrystal, we constructed histograms of extrapolation grades for all atoms in the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal during annealing at 300, 600, and 1000 K and after relaxation using MTP (Fig. 6). Most extrapolation grades for approximately two million sites for all structures were determined to be less than one. This indicates that most local atomic structures in the polycrystals fall within the interpolation region, thereby guaranteeing high calculation accuracy in the constructed MTP80. While there were a few atoms with high-extrapolation grades, the maximum extrapolation grade observed was 1.72, which falls within the “accurate extrapolation” region. Thus, even with the application of active learning methods based on the local atomic environment to these nano-polycrystals, the constructed MTPs remain unchanged. Consequently, in comparison with both direct DFT calculations and extrapolation grade evaluations, the constructed MTPs demonstrate superior DFT accuracy for the stable structures of GGBs and GB triple junctions, as well as their energies and dynamics. It has been noted that nano-polycrystals generated using Voronoi tessellation may deviate from actual polycrystals in terms of deformation behavior90. Nevertheless, these nano-polycrystals may still be sufficient in terms of covering the local atomic environment of polycrystals in accuracy verification.

Average GB energy of α-Fe polycrystals using the constructed MTP

Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between average GB energy and model size in nano-polycrystals. We first discuss the results obtained from the MTP. As the model size increases, the average GB energy converges towards a constant value. For example, the difference in average GB energies between the (22.6 nm)3 and (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals is merely 0.03 J/m2. The average GB energy for the three (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals is 1.57 J/m2 with a standard error of 0.03 J/m2. This result indicates that despite the presence of ~60 GBs, the deviation of the average GB energy among polycrystalline models in relation to the GB character is relatively small. The average GB energy of the (5.66 nm)3 polycrystal is also relatively small. This is attributed to the presence of extremely small grains, which promote grain growth even at 300 K, thereby leading to a decrease in the actual GB area. On the other hand, in the calculation of the average GB energy, the area of the GB was evaluated based on the area of the Voronoi polyhedron when the initial structure was created.

The general grain boundary (GB) energy of α-Fe estimated from the experimental results of W is also shown for comparison89.

The calculated average GB energies of nano-polycrystals were compared to those of GGBs based on experimental data. For bcc metals, Li et al. investigated the scaling factor among different defect structures of the same metal and among the same defect structures across different metals89. Subsequently, they estimated the energy of the GGB of α-Fe at 0 K, using experimental values of the GB energy of the GGB of W measured at high temperatures. The results revealed that the GGB energy of α-Fe is 1.63 J/m2. This value is in good agreement with the average GB energy of 1.57 J/m2 observed for the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal (Fig. 7).

Focusing next on the results using from the NNIP, the average GB energy of nano-polycrystals calculated from the NNIP is similar to that calculated from the MTP, indicating that the NNIP can also estimate the GB energy of GGBs with reasonable accuracy. However, the RMSE of the NNIP for the atomic forces near the GGB was approximately twice as large as that of the MTP. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, the NNIP significantly underestimates the GB energy at finite temperatures for symmetric tilt GBs with a large RMSE of atomic forces, even though it provides results close to those of the DFT for the stable GB energy at 0 K. In addition, extrapolation grade evaluations suggest that the MTP also shows excellent computational accuracy for nano-polycrystals at 600 K and 1000 K. These findings suggest that the MTP is more suitable for the analysis of GGBs at finite temperatures, but further investigation is needed. The EAM and MEAM significantly underestimate the average GB energy. This indicates that the choice of interatomic potential markedly influences the simulations of grain growth driven by GB energy. In addition, the underestimation of GB energy in the EAM and MEAM is related to the Voronoi volume at sites near the GB (“GB energy and atomic structure in α-Fe polycrystals” section), which also plays a significant role in GB segregation.

GB energy and atomic structure in α-Fe polycrystals

The findings presented in “Average GB energy of α-Fe polycrystals using the constructed MTP” section reveal that the constructed MTP can describe α-Fe polycrystals with high accuracy. The local atomic environment in the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals relaxed using the constructed MTP may be similar to that in polycrystals with grain sizes in the micrometer range, a common feature in steel materials. Moreover, the average GB energy closely approximates that of polycrystals. Therefore, we supposed that a detailed investigation of the nano-polycrystals relaxed through the MTP would be particularly interesting. In particular, as mentioned in the Introduction (“Introduction” section), GB segregation is an important control target in material design. Consequently, we conducted a thorough investigation on the Voronoi volume and coordination number, both dominant factors for GB segregation, for nano-polycrystals relaxed through MTP.

Figure 8a and b illustrate the Voronoi volume and coordination number of each atom, respectively, in a (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal with an average GB energy of 1.58 J/m2. Additionally, Fig. 8c and d show the Voronoi volume and coordination number, respectively, as a function of distance from the GB center. These results pertain to one (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal; however, the results for the other two (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals are almost identical. Notably, the coordination number is defined as the number of planes obtained through Voronoi tessellation in each atomic region. Hence, the next nearest neighbor equivalent to the bcc structure is also counted as a coordination number. The Voronoi volume begins to increase in standard deviation from the GB center at ~8.0 Å. The mean Voronoi volume at the GB center measures 12.0 Å3, marking a 6.0% increase compared to the bulk volume. The coordination number increases in standard deviation from the GB center to ~7.0 Å; however, the mean value remains relatively unchanged and is 14.2 at the GB center. Thus, when considering the local atomic environment in terms of Voronoi volume and coordination number, the deviation from the bulk is observed at ~8.0 Å from the GB center.

a Voronoi volume and (b) coordination number of each atom in a (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal with an average grain boundary (GB) energy of 1.58 J/m2. c Voronoi volume and (d) coordination number as a function of distance from the GB center. e Histograms of Voronoi volumes for all sites within 7.35 Å (three atomic layers) of the GB center and for each atomic layer from the GB center in the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal. f Voronoi volume as a function of distance from the GB center for the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals relaxed using the moment tensor potential (MTP), neural network interatomic potential (NNIP), embedded atom method (EAM), or modified EAM (MEAM).

Figure 8e presents histograms of Voronoi volumes for all sites within 7.35 Å (three atomic layers) of the GB center and for each atomic layer from the GB center in the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal. In the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystal, the Voronoi volume ranges from −13.3% to 20.8% at GBs. In particular, the Voronoi volume changes significantly in one atomic layer from the GB center. Within 7.35 Å or three atomic layers, from the GB center, 66.3% of the sites exhibit looser sites (sites with Voronoi volumes larger than that of the bulk), while 33.7% display tighter sites (sites with Voronoi volumes smaller than that of the bulk).

Considering these results, we explore GB segregation in α-Fe polycrystals. For example, for transition metal elements, the solute element occupancy at each site increases exponentially with Voronoi volume from the bulk91, indicating that the major segregation sites exist within one atomic layer from the GB center for both large and small solute elements. In particular, for substitutional solute elements, the proportion of tighter sites is approximately half that of looser sites, indicating that segregation sites for substitutional solute elements with smaller atomic sizes are more limited than those with larger atomic sizes. Figure 8f displays the Voronoi volume as a function of distance from the GB center for the (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals relaxed through the EAM, MEAM, and NNIP, respectively. For example, the ratio of the Voronoi volume at the GB center to that of the bulk is 3.3% and 2.9% for the MEAM and EAM, respectively, which is approximately half of the 6.0% observed for the MTP. In contrast, the results obtained from the NNIP closely agree with those obtained from the MTP. This result indicates that, for example, when considering the GB segregation of a solute with a large atomic volume, the calculation of GB segregation energy using MEAM- or EAM-relaxed nano-polycrystals underestimates the energy by approximately half, which varies approximately linearly with the Voronoi volume91. Furthermore, the amount of GB segregation, which exhibits an exponential dependence on the GB segregation energy92, would be significantly underestimated.

Figure 9a and b present histograms of the misorientation angle and GB energy, respectively, for three (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals obtained by MTP relaxation. Additionally, Fig. 9c illustrates the relationship between GB energy and misorientation angle for each of the three (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals. The area of each GB is the same as that used for calculating the average GB energy, employing the Voronoi polyhedron used to create the initial nano-polycrystalline structure. Each atom was assigned to the nearest GB, and the energy of each GB was calculated. GBs with areas larger than 1000 Å2 were evaluated. The average GB energies of the polycrystals, obtained by averaging the energies for each GB across the three cases, were 1.57, 1.53, and 1.60 J/m2. These values closely align with the average GB energies of 1.58, 1.53, and 1.59 J/m2, calculated by dividing the excess energy of the entire polycrystal by the GB area shown in Fig. 7. The histograms obtained for the three cases displayed a mode value of 1.65–1.70 J/m2, which is higher than the average value for polycrystalline materials, as discussed at the end of this section. The maximum GB energy was 1.79 J/m2, representing a 13.3% increase over the average GB energy value.

Histograms of (a) misorientation angle and (b) grain boundary (GB) energy for three (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals obtained by moment tensor potential (MTP) relaxation. c Relationship between GB energy and misorientation angle for each of the three (28.3 nm)3 polycrystals. d Probability density of the Voronoi volume in the one-atomic layer region near the GB center for these three GBs, along with the polycrystal in Case 1 for comparison. The probability density of the Σ3(111) symmetric tilt GB (1.58 J/m2) is also shown. Note that the probability density in Σ3(111) is scaled down to 1/10 for comparison. e Probability densities of these Voronoi volumes are shown as the difference from the probability density of the Voronoi volume in the one-atomic layer region near the GB center for the polycrystals in Case 1. f Atomic structures and energies of the atoms of the GBs with lowest energy (GBL), corresponding to the mode (GBM), and with highest energy (GBH). Here, the energy reference is the energy of the bulk Fe atom. The energies of these GBs are also shown.

Next, the atomic structure of a representative GB among the large-angle GBs in Case 1 was analyzed in detail. The GB with the lowest GB energy (1.26 J/m2) (GBL), the one corresponding to the mode (1.67 J/m2) (GBM), and that with the highest energy (1.78 J/m2) (GBH) are discussed here. Figure 9d displays the probability density of the Voronoi volume in the one-atomic layer region near the GB center for these three GBs, alongside the polycrystal in Case 1 for comparison. The probability density of the Σ3(111) symmetric tilt GB (1.58 J/m2), which is the most used GB in DFT studies, is also shown. The probability density in Σ3(111) is scaled down to 1/10 for comparison. In Fig. 9e, the probability densities of these Voronoi volumes are shown as the difference from the probability density of the Voronoi volume in the one-atomic layer region near the GB center for the polycrystals in Case 1. The probability density of the Voronoi volume for GBM is close to that of the entire polycrystal. In contrast, in the GBH, the probability density of Voronoi volumes exceeding 12.2 Å3 is increased relative to that of the entire polycrystal. Finally, in the GBL, the probability density of Voronoi volumes close to the bulk Voronoi volume is increased relative to the whole polycrystal. Given the correlation between GB energy and the probability density of Voronoi volumes near the GB50, this indicates that the GB energies of these three GBs have been correctly evaluated. In Σ3(111), there are sites with three different Voronoi volumes, all falling within the range observed in polycrystals. The ratio of sites with these volumes in Σ3(111) closely resembles that observed in the polycrystal. This result indicates that when considering solute atoms for which the Voronoi volume is the dominant factor in GB segregation, the analysis using Σ3(111) GBs is effective for qualitatively understanding the GB segregation. However, because there are only three sites with different Voronoi volumes, it is not sufficient to accurately predict GB segregation in polycrystalline materials.

Figure 9f depicts the atomic structures and energies of the atoms of the GBL, GBM, and GBH. In the GBM and GBH, the regions where the atomic energies are higher than those of the bulk are linearly distributed, and the difference between the two GBs is unclear. In contrast, in the GBL, the atoms in the GB center form periodic facets. The atoms in the faceted region have atomic energies relatively close to those of the bulk, even though the atoms are located near the center of the GB. The atomic structure of this region forms an atomic structure similar to a well-consistent (111)-terminated twist GB. Thus, even in polycrystalline materials with random orientations, instances occur where locally well-matched GBs are formed, resulting in a decrease in the GB energy. This result is one of the reasons why the histogram shown in Fig. 9b for misorientation angles of 15° or more does not exhibit a normal distribution but instead displays a large spread from the mode to the low-energy side.

The results presented in this section, which were obtained through relaxation at near-room temperature (300 K) using a high-precision MTP, are expected to be similar to those of real α-Fe polycrystals with random orientations. As described earlier, the MTP constructed in this study proves valuable for analyzing GBs in polycrystals at the atomic level and predicting GB segregation with high accuracy.

Application of findings from this study

The MTP constructed in this study reproduces the energies and acting atomic forces on arbitrary GGB and GB triple junctions in α-Fe with high accuracy both during annealing and after relaxation. Therefore, it finds applicability in numerous studies, including grain growth of polycrystals93 and investigation of GB energy and mobility94. This MTP is highly effective in improving the accuracy of recently developed methods for analyzing GBs with DFT accuracy. Specifically, Tamura et al.95 developed a method to predict the local energy of each Fe atom in α-Fe nano-polycrystals by combining first-principles local energy analysis and machine learning models. This method can predict the local energy of Fe atoms in any given atomic structure. However, in that study, the analysis was performed on a relaxed nano-polycrystal using an EAM. By conducting relaxation of nano-polycrystals with the MTP constructed in this study and applying the prediction method to these systems, it is possible to predict local energies for nano-polycrystals that are closer to reality. A method has also been proposed to calculate the GB segregation energy using machine learning from the local atomic environment of segregation sites48,96,97. As discussed in “GB energy and atomic structure in α-Fe polycrystals” section, the GB structure of the host metal significantly influences the predicted GB segregation energy and the amount of GB segregation. The MTP constructed in this study can serve as a highly accurate GB model for this purpose. Alternatively, by extending the MTP to binary systems based on the constructed MTP and applying a method for predicting GB segregation using nano-polycrystals, the MTP should accurately predict the segregation of solute elements at GBs without the need for experiments. Recently, Poul et al. proposed an extension of the method for constructing MTPs using the RandSPG algorithm to binary systems98. The MTP obtained through this method may enable a highly accurate prediction of GB segregation at general GBs.

The MTP constructed in this study provides a strong foundation for simulating the deformation and fracture of α-Fe polycrystals. As demonstrated in the Supplementary Note 6, the constructed MTP reproduces the two-dimensional energy profiles of the screw dislocation core position and the Peierls potential with DFT accuracy. These are necessary for accurate reproduction of plastic deformation. In addition, the generalized stacking energy curves under no strain and tensile strain, which are essential for accurately describing the crack propagation, also demonstrate accuracy comparable to that of DFT. Nevertheless, additional training data may be required to analyze nanoscale deformation behavior with high accuracy, as demonstrated by the deformation behavior analysis using MLIPs in ceramics99. While the applicability to the simulation of deformation and fracture of α-Fe polycrystals falls beyond the scope of this study and is not addressed herein, it will be investigated in detail in the future.

In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of constructing an interatomic potential that reproduces all GBs, including GGBs, with high accuracy. This is achieved by augmenting the basic training dataset, which reproduces the bulk properties, with the RANDSPG dataset proposed by Poul et al.66, and subsequently constructing an MTP. Given the successful construction of a generic MTP for Mg by Poul et al. using a RANDSPG dataset, the present results suggest the possibility of constructing MLIPs for GBs of other metals besides Fe with excellent accuracy. Remarkably, the RANDSPG dataset comprises only 10 atoms at maximum, resulting in exceptionally low computational cost for acquiring a training dataset. Specifically, the calculation cost required to construct the RANDSPG dataset is comparable to that of performing AIMD at 300, 600, and 1000 K using a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell of α-Fe. In essence, a diverse range of GBs can be effectively incorporated at a computational cost equivalent to collecting a small fraction of the training dataset typically utilized to reproduce the bulk properties of metallic materials. For instance, in the case of the NNIP for Fe-H, over 50 AIMD simulations, each consisting of several hundred steps, were performed on atomic structures that included vacancies, surfaces, dislocations, and generalized stacking faults, in addition to the four symmetric tilt GBs, to obtain a pure Fe training dataset63. The computational cost to obtain the RANDSPG dataset used in this study is comparable to that required to run the AIMD at 300, 600, and 1000 K for Σ5(310) symmetric tilt GBs, which was used to obtain the training dataset for the NNIP of Fe-H. This fact indicates that the computational cost to obtain the RANDSPG dataset is relatively low. Therefore, while snapshots obtained from AIMD for basic crystal structures such as bcc, fcc, and hcp are generally used as a starting point for MLIP construction100, it is also beneficial to employ the RANDSPG dataset as one of the basic initial datasets for MLIP construction.

Recently, an on-the-fly learning method was proposed, which successfully constructed MLIPs that reproduce nano-polycrystalline diamond with high accuracy101. In this method, MLIPs constructed with training data obtained using AIMD were used in the initial stage to identify additional structures for training. The acquisition of additional training data requires DFT calculations on calculation cells consisting of ~100 atoms cut from nano-polycrystals, which can be computationally expensive. Given the low computational cost of acquiring the RANDSPG dataset, as described above, starting the search from an MLIP constructed using the RANDSPG data set may enable a less computationally expensive and more efficient MLIP construction. Thus, at the very least, when the analysis includes GBs, it can serve as a strong starting point for any MLIP construction, such as those based on concurrent100 or active68 learning. Consequently, the findings of this study will significantly advance material design, benefiting not only steel materials but also any polycrystalline metallic materials through the proposed method of constructing interatomic potentials.

Data availability

The potential is available on the Github page https://github.com/KazumaIto0810/MTP.

References

Horvath, C.D. Chapter 2 - Advanced steels for lightweight automotive structures, In: P.K. Mallick (Ed.), Materials, Design and Manufacturing for Lightweight Vehicles (Second Edition), pp. 39–95, (Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, 2021).

Suh, D.-W. & Kim, S.-J. Medium Mn transformation-induced plasticity steels: Recent progress and challenges. Scr. Mater. 126, 63–67 (2017).

Plaut, R. L., Herrera, C., Escriba, D. M., Rios, P. R. & Padilha, A. F. A short review on wrought austenitic stainless steels at high temperatures: Processing, microstructure, properties and performance. Mater. Res. 10, 453–460 (2007).

Edmonds, D. V., He, K., Rizzo, F. C., De Cooman, B. C., Matlock, D. K. & Speer, J. G. Quenching and partitioning martensite—a novel steel heat treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 438-440, 25–34 (2006).

Yoo, J., Jo, M. C., Jo, M. C., Kim, S., Kim, S.-H., Oh, J., Sohn, S. S. & Lee, S. Effects of solid solution and grain-boundary segregation of Mo on hydrogen embrittlement in 32MnB5 hot-stamping steels. Acta Mater. 207, 116661 (2021).

Soleimani, M., Kalhor, A. & Mirzadeh, H. Transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) in advanced steels: a review. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 795, 140023 (2020).

Takayama, S., Ogura, T., Fu, S.-C. & McMahon, C. J. The calculation of transition temperature changes in steels due to temper embrittlement. Metall. Trans. A 11, 1513 (1980).

Hardie, D. & Liu, S. E. The effect of stress concentration on hydrogen embrittlement of a low alloy steel. Corros. Sci. 38, 721–733 (1996).

Hirth, J. P. Effects of hydrogen on the properties of iron and steel. Metall. Trans. A 11, 861–890 (1980).

Tsay, L. W., Chi, M. Y., Wu, Y. F., Wu, J. K. & Lin, D. Y. Hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility and permeability of two ultra-high strength steels. Corros. Sci. 48, 1926–1938 (2006).

Mohrbacher, H. & Senuma, T. Alloy optimization for reducing delayed fracture sensitivity of 2000 MPa press hardening steel. Metals 10, 853–871 (2020).

Jo, M. C., Yoo, J., Kim, S., Kim, S., Oh, J., Bian, J., Sohn, S. S. & Lee, S. Effects of Nb and Mo alloying on resistance to hydrogen embrittlement in 1.9 GPa-grade hot-stamping steels. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 789, 139656 (2020).

Liu, Y., Chen, Y., Yang, C. & Han, X. Study on hydrogen embrittlement and reversibility of hot-stamped aluminized 22MnB5 steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 848, 143411 (2022).

Okayasu, M. & Fujiwara, T. Hydrogen embrittlement characteristics of hot-stamped 22MnB5 steel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 19657–19669 (2021).

Zhang, S., Li, J., Peng, Z., Liu, S., Huang, F. & Liu, J. Synergistic effects of Ta and Mo on the hydrogen embrittlement resistance in ultra-high strength hot stamping steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 872, 144956 (2023).

Kim, H.-J., Jeon, S.-H., Yang, W.-S., Yoo, B.-G., Chung, Y.-D., Ha, H.-Y. & Chung, H.-Y. Effects of titanium content on hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of hot-stamped boron steels. J. Alloy. Compd. 735, 2067–2080 (2018).

Okada, K., Shibata, A., Sasaki, T., Matsumiya, H., Hono, K. & Tsuji, N. Improvement of resistance against hydrogen embrittlement by controlling carbon segregation at prior austenite grain boundary in 3Mn-0.2C martensitic steels. Scr. Mater. 224, 115043 (2023).

Zhang, S., Wan, J., Zhao, Q., Liu, J., Huang, F., Huang, Y. & Li, X. Dual role of nanosized NbC precipitates in hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of lath martensitic steel. Corros. Sci. 164, 108345 (2020).

Scheiber, D., Prabitz, K., Romaner, L. & Ecker, W. The influence of alloying on Zn liquid metal embrittlement in steels. Acta Mater. 195, 750–760 (2020).

Razmpoosh, M. H., DiGiovanni, C., Zhou, Y. N. & Biro, E. Pathway to understand liquid metal embrittlement (LME) in Fe-Zn couple: From fundamentals toward application. Prog. Mater. Sci. 121, 100798 (2021).

Ahmadian, A., Scheiber, D., Zhou, X., Gault, B., Romaner, L., Kamachali, R. D., Ecker, W., Dehm, G. & Liebscher, C. H. Interstitial segregation has the potential to mitigate liquid metal embrittlement in iron. Adv. Mater. 35, e2211796 (2023).

Ikeda, Y., Yuan, R., Chakraborty, A., Ghassemi-Armaki, H., Zuo, J. M. & Maaß, R. Early stages of liquid-metal embrittlement in an advanced high-strength steel. Mater. Today Adv. 13, 100196 (2022).

Razmpoosh, M. H., Macwan, A., Biro, E., Chen, D. L., Peng, Y., Goodwin, F. & Zhou, Y. Liquid metal embrittlement in laser beam welding of Zn-coated 22MnB5 steel. Mater. Des. 155, 375–383 (2018).

Ito, K., Tanaka, Y., Mitsunobu, T., Kohtake, T., Tsutsui, K. & Sawada, H. First-principles computational tensile test of γ-Fe grain boundaries considering the effect of magnetism: electronic origin of grain boundary embrittlement due to Zn segregation. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 053604 (2022).

Melford, D. A. The influence of residual and trace elements on hot shortness and high temperature embrittlement. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 295, 89–103 (1980).

Born, K. Surface defects in the hot working of steel from residual copper and tin. Stahl und Eisen 73, 1268–1277 (1953).

Nicholson, A. & Murray, J. Surface hot shortness in low carbon steel. J. Iron Steel Inst. 203, 1007–1018 (1965).

Yin, L. & Sridhar, S. Effects of residual elements arsenic, antimony, and tin on surface hot shortness. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 42, 1031–1043 (2011).

Ito, K., Mitsunobu, T., Ishiguro, Y., Kohigashi, Y. & Tsutsui, K. Analysis of grain boundary embrittlement by Cu and Sn in paramagnetic γ-Fe by first-principles computational tensile test. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 093603 (2022).

Ito, K., Tanaka, Y., Tsutsui, K. & Sawada, H. Effect of Mo addition on hydrogen segregation at α-Fe grain boundaries: A first-principles investigation of the mechanism by which Mo addition improves hydrogen embrittlement resistance in high-strength steels. Comput. Mater. Sci. 218, 111951 (2023).

Razmpoosh, M. H., Langelier, B., Marzbanrad, E., Zurob, H. S., Zhou, N. & Biro, E. Atomic-scale investigation of liquid-metal-embrittlement crack-path: revealing mechanism and role of grain boundary chemistry. Acta Mater. 204, 116519 (2021).

Jin, H., Elfimov, I. & Militzer, M. Study of the interaction of solutes with Σ5 (013) tilt grain boundaries in iron using density-functional theory. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 093506 (2014).

Yamaguchi, M. First-principles study on the grain boundary embrittlement of metals by solute segregation: Part I. Iron (Fe)-solute (B, C, P, and S) systems. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 42, 319–329 (2011).

Ito, K., Sawada, H., Tanaka, S., Ogata, S. & Kohyama, M. Electronic origin of grain boundary segregation of Al, Si, P, and S in bcc-Fe: combined analysis of ab initio local energy and crystal orbital Hamilton population. Model. Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 29, 015001 (2020).

Wachowicz, E. & Kiejna, A. Effect of impurities on structural, cohesive and magnetic properties of grain boundaries in α-Fe. Model. Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 19, 025001 (2011).

Xu, Z., Tanaka, S. & Kohyama, M. Grain-boundary segregation of 3d-transition metal solutes in bcc Fe: Ab initio local-energy and d-electron behavior analysis. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 31, 115001 (2019).

Bhattacharya, S. K., Kohyama, M., Tanaka, S. & Shiihara, Y. Si segregation at Fe grain boundaries analyzed by ab initio local energy and local stress. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 26, 355005 (2014).

Čák, M., Šob, M. & Hafner, J. First-principles study of magnetism at grain boundaries in iron and nickel. Phys. Rev. B 78, 054418 (2008).

Kohyama, M., Tanaka, S. & Shiihara, Y. Ab initio local-energy and local-stress calculations for materials science and engineering. Mater. Trans. 62, 1–15 (2021).

Ito, K. Significant effect of magnetism on grain boundary segregation in γ-Fe: A systematic comparison of grain boundary segregation in nonmagnetic and paramagnetic γ-Fe by first-principles calculations. Mater. Today Commun. 38, 107849 (2024).

Ito, K., Sawada, H. & Ogata, S. First-principles study on the grain boundary embrittlement of bcc-Fe by Mn segregation. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 013609 (2019).

Wagih, M. & Schuh, C. A. Viewpoint: Can symmetric tilt grain boundaries represent polycrystals? Scr. Mater. 237, 115716 (2023).

Ito, K., Tanaka, Y., Tsutsui, K. & Sawada, H. Analysis of grain-boundary segregation of hydrogen in bcc-Fe polycrystals via a nano-polycrystalline grain-boundary model. Comput. Mater. Sci. 225, 112196 (2023).

Ito, K., Tanaka, Y. & Sawada, H. Application of grain boundary segregation prediction using a nano-polycrystalline grain boundary model to transition metal solute elements: prediction of grain boundary segregation of Mn and Cr in bcc-Fe polycrystals. Mater. Trans. 63, 269–277 (2022).

Ito, K., Sawada, H. & Ogata, S. Theoretical prediction of grain boundary segregation using nano-polycrystalline grain boundary model. Mater. Trans. 62, 575–581 (2021).

Wagih, M. & Schuh, C. A. Spectrum of grain boundary segregation energies in a polycrystal. Acta Mater. 181, 228–237 (2019).

Huber, L., Hadian, R., Grabowski, B. & Neugebauer, J. A machine learning approach to model solute grain boundary segregation. NPJ Comput. Mater. 4, 64 (2018).

Wagih, M. & Schuh, C. A. Learning grain-boundary segregation: from first principles to polycrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 046102 (2022).

Tuchinda, N. & Schuh, C. A. The vibrational entropy spectra of grain boundary segregation in polycrystals. Acta Mater. 245, 118630 (2023).

Scheiber, D., Pippan, R., Puschnig, P. & Romaner, L. Ab initio calculations of grain boundaries in bcc metals. Model. Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 24, 035013 (2016).

Behler, J. Four generations of high-dimensional neural network potentials. Chem. Rev. 121, 10037–10072 (2021).

Unke, O. T., Chmiela, S., Sauceda, H. E., Gastegger, M., Poltavsky, I., Schütt, K. T., Tkatchenko, A. & Müller, K.-R. Machine learning force fields. Chem. Rev. 121, 10142–10186 (2021).

Yokoi, T., Matsuura, M., Oshima, Y. & Matsunaga, K. Grain-boundary thermodynamics with artificial-neural-network potential: Its ability to predict the atomic structures, energetics, and lattice vibrational properties for Al. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 053803 (2023).

Zhang, L., Csányi, G., van der Giessen, E. & Maresca, F. Atomistic fracture in bcc iron revealed by active learning of Gaussian approximation potential. NPJ Comput. Mater. 9, 217 (2023).

Novikov, I., Grabowski, B., Körmann, F. & Shapeev, A. Magnetic Moment Tensor Potentials for collinear spin-polarized materials reproduce different magnetic states of bcc Fe. NPJ Comput. Mater. 8, 13 (2022).

Kwon, H., Shiga, M., Kimizuka, H. & Oda, T. Accurate description of hydrogen diffusivity in bcc metals using machine-learning moment tensor potentials and path-integral methods. Acta Mater. 247, 118739 (2023).

Wang, Y., Liu, J., Li, J., Mei, J., Li, Z., Lai, W. & Xue, F. Machine-learning interatomic potential for radiation damage effects in bcc-iron. Comput. Mater. Sci. 202, 110960 (2022).

Wang, F., Yang, Z., Li, F., Shao, J.-L. & Xu, L.-C. Strategic sampling with stochastic surface walking for machine learning force fields in iron’s bcc–hcp phase transitions. RSC Adv. 13, 31728–31737 (2023).

Zhang, L., Csányi, G., van der Giessen, E. & Maresca, F. Efficiency, accuracy, and transferability of machine learning potentials: Application to dislocations and cracks in iron. Acta Mater. 270, 119788 (2024).

Zhang, S., Meng, F., Fu, R. & Ogata, S. Highly efficient and transferable interatomic potentials for α-iron and α-iron/hydrogen binary systems using deep neural networks. Comput. Mater. Sci. 235, 112843 (2024).

Dragoni, D., Daff, T. D., Csányi, G. & Marzari, N. Achieving DFT accuracy with a machine-learning interatomic potential: Thermomechanics and defects in bcc ferromagnetic iron. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 013808 (2018).

Mori, H. & Ozaki, T. Neural network atomic potential to investigate the dislocation dynamics in bcc iron. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 040601 (2020).

Meng, F.-S., Du, J.-P., Shinzato, S., Mori, H., Yu, P., Matsubara, K., Ishikawa, N. & Ogata, S. General-purpose neural network interatomic potential for the 𝛼-iron and hydrogen binary system: toward atomic-scale understanding of hydrogen embrittlement. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 113606 (2021).

Szlachta, W. J., Bartók, A. P. & Csányi, G. Accuracy and transferability of Gaussian approximation potential models for tungsten. Phys. Rev. B 90, 104108 (2014).

Lejček, P., Šob, M. & Paidar, V. Interfacial segregation and grain boundary embrittlement: an overview and critical assessment of experimental data and calculated results. Prog. Mater. Sci. 87, 83–139 (2017).

Poul, M., Huber, L., Bitzek, E. & Neugebauer, J. Systematic atomic structure datasets for machine learning potentials: application to defects in magnesium. Phys. Rev. B 107, 104103 (2023).

Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: a class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. Multiscale Modeling Simul. 14, 1153–1173 (2016).

Novikov, I. S., Gubaev, K., Podryabinkin, E. V. & Shapeev, A. V. The MLIP package: moment tensor potentials with MPI and active learning. Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 2, 025002 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Crystal structure and pair potentials: a molecular-dynamics study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 1196–1199 (1980).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the open visualization tool. Model. Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2009).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Avery, P. & Zurek, E. RandSpg: an open-source program for generating atomistic crystal structures with specific spacegroups. Comput. Phys. Commun. 213, 208–216 (2017).

Podryabinkin, E., Garifullin, K., Shapeev, A. & Novikov, I. MLIP-3: active learning on atomic environments with moment tensor potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 084112 (2023).

Möller, J. J., Mrovec, M., Bleskov, I., Neugebauer, J., Hammerschmidt, T., Drautz, R., Elsässer, C., Hickel, T. & Bitzek, E. ${110}$ planar faults in strained bcc metals: origins and implications of a commonly observed artifact of classical potentials. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 093606 (2018).