Abstract

Lightweight refractory high-entropy alloys (LW-RHEAs) hold significant potential in the fields of aviation, aerospace, and nuclear energy due to their low density, high strength, high hardness, and corrosion resistance. However, the enormous composition space has severely hindered the development of novel LW-RHEAs with excellent comprehensive performance. In this paper, an machine learning (ML)-based alloy design strategy combined with a multi-objective optimization method was proposed and applied for a rational design of Al-Nb-Ti-V-Zr-Cr-Mo-Hf LW-RHEAs. The quantitative relation of “composition-structure-property” was first established by ML modeling. Then, feature analysis reveals that Cr content greater than 12 at.% is a key criterion for alloys with high corrosion resistance. The phase structure, density, melting point, hardness and corrosion resistance of the alloys were screened layer by layer, and finally, three LW-RHEAs with superb hard and corrosion resistance were successfully designed. Key experimental validation indicates that three target alloys have densities around 6.5 g/cm3, and all alloys are disordered bcc_A2 single-phase with the highest hardness of 593 HV and the largest pitting potential of 2.5 VSCE, which far exceeds all the literature reports. The successful demonstration in this paper clearly demonstrates that the present design strategy driven by the ML technique should be generally applicable to other RHEA systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-entropy alloys (HEAs), which typically consist of 5 or more principal elements with atomic percentages of each at 5–35 at.%, were first proposed by Yeh et al.1 in 2004. HEAs have garnered significant attention for their simple solid solution structure and excellent mechanical properties, as well as their resistance to corrosion and oxidation. Among different types of HEAs, refractory high-entropy alloys (RHEAs) based on refractory transition elements (like V, Cr, Zr, Nb, Mo, Hf, Ta, W, and Re) were recently developed for higher hardness, higher strength, better corrosion and high-temperature resistance2,3. In 2010, the first RHEAs, WNbMoTa and WNbMoTaV were fabricated by Senkov et al.4 and exhibited superior high-temperature mechanical properties than Ni-based superalloys. However, heavy refractory elements (like Ta, W, and Mo) in common RHEAs significantly increase their densities4 (e.g., the density of WNbMoTa and WNbMoTaV are 12.36 g/cm3 and 9.94 g/cm3), which severely limit the application of RHEAs in various fields.

The concept of lightweight refractory high-entropy alloys (LW-RHEAs) breaks the bottleneck stage of conventional RHEAs by incorporating low-density elements (such as Ti, Al, V, and Zr) to replace high-density elements5,6,7, for instance, AlNbTiZr8, Al0.2CrNbTiV9, Ti2VNbMoZr10, etc. These LW-RHEAs typically have densities below 8 g/cm3 while retaining the excellent properties of traditional RHEAs11. For instance, the dual-phase AlNb0.5TiV2Zr0.5 LW-RHEA with Laves precipitation, prepared by Jiang et al.7, exhibits a low density of 5.43 g/cm3 and a high hardness of 622 HV. Chen et al.12 fabricated an AlTiVMoNb alloy coating on a Ti-6Al-4V substrate using laser cladding, achieving a super hardness of 888.5 HV0.2, which is 2.52 times that of the substrate. Moreover, Li et al.13 prepared a TiCrVNb0.5Al0.5 LW-RHEA by vacuum arc melting and carried out electrochemical corrosion experiments. In 3.5 wt%. NaCl solution, the TiCrVNb0.5Al0.5 alloy showed a corrosion current density (icorr) of 8.91 × 10-8 A·cm-2, a corrosion potential (Ecorr) of –0.45 VSCE, and a pitting potential (Epit) of 1.95 VSCE, indicating better corrosion resistance than conventional alloys, bulk metallic glasses, and other HEAs reported in the literature. The unique lattice distortion and sluggish diffusion effects of LW-RHEAs contribute to their high hardness and excellent corrosion resistance14,15,16,17,18, highlighting their broad application prospects and research value.

However, developing novel LW-RHEAs with excellent comprehensive properties is still challenging due to the strong trade-off between hardness and corrosion resistance. Traditional RHEAs tend to form simple bcc solid solutions, but the inclusion of lightweight and compound-forming elements such as Al and Zr introduces intermetallic phases that create more complex microstructures, significantly impacting the properties of LW-RHEAs. Wang et al.14 found that the Laves phase formed in the TiZrHfNbFex alloy greatly enhances the hardness but reduces the corrosion resistance. In corrosive solution, the main corrosion pattern of multi-phase alloys is pitting corrosion appearing in phase boundaries19,20,21. Li et al.21 tested the corrosion resistance of TiZr0.5NbCr0.5V in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution and found that localized corrosion initiates mainly at the boundaries of the bcc_A2 and Cr2Zr Laves phase. Therefore, achieving excellent corrosion resistance requires careful control of phase structure and composition.

In the expanding chemical space where the “structure-property” relationship is increasingly blurred, machine learning (ML) methods have proven effective at capturing patterns that may elude human analysis, thereby facilitating the search for optimal materials22,23,24. Huang et al.25 have developed two ML models to predict the phase structure and hardness of CrMoNbTi RHEAs. Moreover, when considering the different property requirements of LW-RHEAs, alloy design becomes a multi-objective optimization problem that must balance the constraints between density, hardness, corrosion resistance, and phase structure. Strategies such as the sequential filter strategy and Pareto optimization are useful for multi-objective design26,27,28. By converting multi-objective problems into single-objective ones (Ashby’s method), the quality index (Q = UTS + YS×lgEL), which considers both strength and ductility, has been widely used for designing lightweight aluminum alloys29,30,31,32. Despite the use of advanced algorithms, the limited experimental data for the newly developed LW-RHEAs poses a great challenge for alloy design. Therefore, developing an effective strategy is crucial for efficiently designing high-performance LW-RHEAs. Exhausting literature analysis revealed that LW-RHEAs with bcc_A2 single-phase show potential for high hardness33,34,35,36 and high corrosion resistance13,37. For example, the bcc_A2 single-phase TiCrVNb0.5Al0.5 alloy with Epit of 1.95 VSCE13 exhibits better pitting resistance than the multi-phase TiZr0.5NbCr0.5V alloy with Epit of 1.4 VSCE21. What’s more, the bcc_A2 phase is less brittle than the bcc_B2 phase. Therefore, focusing on the bcc_A2 single-phase region can streamline the composition screening process for high hardness and corrosion resistance.

Thus, to break through the trade-off relation between hardness and corrosion resistance, an advanced ML-driven alloy design strategy combined with feature engineering techniques, multi-objective optimization method, and key experiments was developed in the present work (Fig. 1). The major items of the present work are: (i) constructing the “composition-structure-property” quantitative relation of Al-Nb-Ti-V-Zr-Cr-Mo-Hf LW-RHEAs based on the collected high-quality database and ML modeling, (ii) identifying key feature of corrosion resistance with limited data using the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method, (iii) selecting target alloys by layer-by-layer filtration of phase structure, hardness, corrosion resistance, density, and melting point, (iv) validating the accuracy of established ML model by comparing the predicted phase and properties of designed alloys with the experimental data, and (v) exploring the key parameters affecting the hardness and corrosion resistance of designed as-cast LW-RHEAs.

Results

Construction of phase classification model

As mentioned, bcc_A2 single-phase LW-RHEAs are the most promising alloy for high corrosion resistance and high hardness. Therefore, the ML approach was applied for the accurate and efficient design of phase structures in complex composition ranges. At first, the phase structure dataset of arc melting Al-Nb-Ti-V-Zr-Cr-Mo-Hf LW-RHEAs, which includes 92 pieces of data from 28 publications, was established in the present work and displayed in the supplementary documents (Table S1). The dataset contains information on alloy composition, empirical parameters, and phase structure. As shown in Fig. 2 and Table S2, most (83%) of the LW-RHEAs have the disordered bcc_A2 phase as the matrix phase, and only some (17%) of the alloys are the ordered bcc_B2 phase. For the subsequent model training, the alloy phase structure was categorized into five classes (bcc_A2, bcc_A2 + IM, bcc_A2+bcc_B2, bcc_B2, and bcc_B2 + IM) based on the type of matrix phase and the presence of intermetallic phases.

Different machine learning algorithms have their own merits, and finding the best combination of algorithms and feature variables is the key to achieving accurate predictions of phase structure. In this work, the alloy composition information was transferred to thermodynamic parameters (ΔHmix, ΔSmix, Tm, and Ω), atomic size parameters (δr and γ), and electronic parameters (VEC, e/a, ΔχPauling, and ΔχAllen) as the input features for phase model construction. The calculation formulas for each parameter can be found in Tables S4 and S5. Figure 2b shows Pearson’s correlation coefficients, all 10 features are suitable for model construction with no apparent linear relationship between any two features. Six different ML classification models were trained and evaluated, including Random Forest (RF), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), polynomial kernel Support Vector Machine Classification (SVC.poly), radial basis function kernel Support Vector Machine Classification (SVC.rbf), and Logistic Regression (LR) model.

The original dataset was split into a training set and a testing set with different split ratios (the testing set is taken from 10% to 60% of the original dataset). Under different ratios, 100 times of data splitting and model training were carried out, and the value of mean and standard deviation of the prediction accuracies were calculated, which were used as the metrics for evaluating the model accuracy and generalization ability, respectively. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, b, With the increasing size of the testing set, the accuracy decreases but the stability of prediction results improves (lower standard deviation value). The result with a 0.2 split ratio was selected as the basis for model selection since the testing set still maintained a high prediction accuracy and the standard deviation was reduced to a low value. Among six different ML models, the SVC.rbf model exhibits the maximum accuracy and lowest standard deviation for both the training and testing sets. Thus, SVC.rbf was chosen as the base model to predict the phase structure of unexplored alloys in the virtual space.

a Average value and (b) standard deviation of testingset prediction accuracy for six different ML algorithms with different split ratios after 100 times modeling. c The average prediction accuracy of each possible SVC.rbf model containing a subset of preselected features. Each point represents the result of 1000 modeling. d Prediction accuracy of final SVC.rbf model for different phases.

In order to reduce the computation time and improve model robustness, a hybrid method combining a correlation analysis and a feature selection was used to remove the irrelevant and redundant features. The correlation coefficient map depicted in Fig. 2b has demonstrated that there is no strong linear correlation (larger than 0.95) between any two of the features. Subsequently, one or more features were picked up as the feature set from the thermodynamic, atomic size, and electronic parameters, respectively. Key feature combinations for phase structures were screened by considering all possible feature subsets and identifying which subset gave rise to the highest accuracy. The mean prediction accuracy of testing set in the SVC.rbf model after 1000 times modeling is plotted in Fig. 3c. From a starting set of knowledge-based features, the initial increase in accuracy indicates an improvement of the model and the later decrease is due to possible over-fitting caused by redundant feature information. As shown in Fig. 3c, the best performance of the model is given by a five-tuple feature set with the highest accuracy of 85.93%. Therefore, the best five features (Ω, δr, γ, ΔχPauling, and ΔχAllen) were selected for model simplicity, accuracy, and generalizability.

Combining the selected five key features as input variables with 80% origin data as training set, the final SVC.rbf phase prediction model was constructed after randomized hyperparameter optimization with tenfold cross-validation. The model performance was plotted in Fig. 3d, the average accuracy for the training set and testing set are 98.63% and 94.74%, respectively, showing excellent prediction ability. A variety of empirical criteria have been developed for alloy phase structure designing. Yang and Zhang38 proposed Ω ≥ 1.1 and δr ≤ 6.6% as a criterion for forming the solid phase. Yurchenko et al.11 inferred that the Laves phase is formed in the alloy when δr > 5.0% and ΔχAllen > 7.0%. Zhu et al.39 proposed a criterion that the two-phase region of (bcc+Laves) exists when δr > 5.295% and ΔχAllen > 7.058%. For a comprehensive comparison, each empirical rule was used to distinguish the alloy phase structure in our dataset. As shown in Table 1, the accuracy of the empirical criteria is low, because most empirical criteria are derived from the experimental data of classic HEAs, and they are not suitable for novel LW-HEAs. Conversely, the constructed ML model in this work provides accurate predictions for all types of phase structures simultaneously.

Construction of hardness prediction model

Besides the phase structure model, the prediction model for mechanical property (hardness) will also be constructed to design high-performance LW-RHEAs. At first, a hardness dataset of bcc_A2 single phase Al-Nb-Ti-V-Zr-Cr-Mo-Hf alloys was established, including 22 pieces of experiment data from literature9,10,40,41,42,43,44,45. The range of hardness values is between 200 and 550 with the highest hardness of 549 HV obtained from Al0.8CrNbTiV alloy9. A similar selection strategy for the phase model was also used to construct the best performance hardness model. The origin dataset was split into an 80% training set and a 20% testing set. Six well-known machine learning regression models including RF, KNN, MLP, Ridge regression, SVR.rbf, and SVR.poly were employed to construct the relation between the input features and hardness, and each regression model will be repeated 100 times. Figure 4a plotts the predicted mean absolute error (MAE) results of all models, and the MLP was selected as the base model with its lowest MAE value. As shown in Fig. 4b, the ΔHmix, Ω, δr, VEC, and ΔχPauling were identified as the best five features for hardness prediction. After hyperparameter optimization, the performance of the final hardness model is shown in Fig. 4c. The predicted hardness is in good agreement with the experimental results (average MAE value is lower than 13 HV). The determination coefficient (R2) of training and testing sets are as high as 0.95 and 0.92 respectively.

a Average prediction MAE value of testing set for six different ML algorithms after 100 times modeling. b The average prediction error of each MLP model contains a feature subset. c Performance of the trained MLP model on both the training set and the testing sets. d SHAP analysis result of ML hardness model.

The SHAP algorithm was used to visually parse the model. As shown in Fig. 4d, feature importance and the impact of each feature on model prediction were assessed by calculating the SHAP value. The abscissa denotes the SHAP value, and the vertical axis represents different features, each dot stands for a sample. A positive/negative SHAP value of a feature means the feature improves/weakens the hardness. The color of each point represents the size of the feature value, as the color gets closer to pink the feature value is larger. For a single feature, the wider horizontal coverage means a greater influence of the feature on the prediction result, i.e., the feature is more important. From Fig. 4d, VEC and ΔHmix were identified as the two most important features that affect the hardness of the alloy. High VEC values and low ΔHmix values are desirable for high-hardness alloys.

Key feature analysis for corrosion property

Due to the scarcity and fragmentation of experimental data on the corrosion properties of the Al-Nb-Ti-V-Zr-Cr-Mo-Hf alloys, it is not an advisable choice to construct an ML model directly for corrosion prediction. In the present work, a key feature of corrosion resistance was extracted from limited data to accomplish the design of bcc_A2 single-phase super-hard and super-corrosion resistant Al-Nb-Ti-V-Zr-Cr-Mo-Hf LW-RHEAs. Figure 5a plotts the composition and corrosion current density (icorr) of 17 different LW-RHEAs with bcc_A2 matrix phase. To further investigate the effect of alloy composition on corrosion resistance, an ML model was established with the experimental dataset, and the performance was shown in Fig. 5b. The importance of each feature can be evaluated by calculating its SHAP value. Features with positive SHAP values positively impact the prediction, while those with negative values have a negative impact. As shown in Fig. 5c, the contents of Mo and Cr elements have greater impact on the corrosion resistance of the alloy. It is worth noting that SHAP values are lower when the content of Cr elements is higher (the red point), which indicates that more Cr will reduce the corrosion current density, improving the corrosion resistance. But the Mo element has the reverse effect. According to Fig. 5a, LW-RHEAs with low icorr mainly contain a high content of Cr element. Thus, as a recognized anti-corrosion element, the Cr content greater than 12 at.% was considered as a criterion for a high corrosion resistance alloy, which will be used in the composition design of super-corrosion resistant LW-RHEAs in the following steps.

Composition design: step-by-step selection

Based on the composition range of bcc_A2 LW-RHEAs in the hardness dataset (analyzed in Table S3), the composition searching space of AlaNbbTicVdZreCrfMogHfh alloy was defined as: 0 ≤ a ≤ 20, 8 ≤ b ≤ 28, 20 ≤ c ≤ 34, 0 ≤ d ≤ 22, 0 ≤ e ≤ 16, 0 ≤ f ≤ 20, 0 ≤ g ≤ 24, and 0 ≤ h ≤ 10 at.% with a step of 2 at.%, which includes 949307 virtual alloys. All the composition information in the prediction dataset was converted into empirical feature variables. Then the trained phase structure model and hardness model were applied to predict the phase structure and hardness of 949,307 virtual alloys for the following multi-objective optimization design. As illustrated in Fig. 6, a sequential filter strategy was applied to meet the demand for bcc_A2 single-phase superb hard and corrosion-resistant alloys. Combining the results of corrosion resistance and hardness analysis (Fig. 5 and Table S3) as well as the model prediction results, the alloy properties were screened sequentially with the following conditions:

-

(1)

Target alloy must be bcc_A2 single-phase.

-

(2)

The hardness of the target alloy should be better than 80% of experimental data, i.e., larger than 480 HV.

-

(3)

The alloy should contain more than 12 at.% Cr to ensure excellent corrosion resistance.

-

(4)

As a lightweight refractory alloy, the theoretical density, ρ, should be less than 6.5 g/cm3 (80% of experimental data), and the calculated melting point, Tm, should be greater than 2100 K.

Due to the trade-off relation between hardness and corrosion resistance, it is hard to improve two properties simultaneously46. To facilitate the exploration of key affective factors, three target alloys with high, medium, and low hardness were designed after a series of screenings, which corresponds to high hardness (A1), outstanding comprehensive performance (A2), and excellent corrosion resistance (A3) alloys, respectively (plotted in Fig. 6). The detailed alloy compositions are Al20Nb28Ti20V4Cr20Mo8, Al14Nb22Ti30V2Cr20Mo12, and Al8Nb22Ti34V4Cr20Mo12. Since Hf is a high-density element (13.31 g/cm3) that significantly increases alloy density, three target alloys are all free of Hf. Meanwhile, the atomic size of Zr is the largest among the Al-Nb-Ti-V-Zr-Cr-Mo-Hf system, and Zr element has a larger negative enthalpy of mixing with Al and Cr atom (i.e., –44 and –12 kJ/mol). Consequently, the Zr element is not easily dissolved into the matrix and tends to precipitate in the form of intermetallic10,34,43. The Zr-based intermetallic may not only increase the brittleness but also deteriorate the corrosion resistance of the alloy15,34,47,48. Thus, none of the three target alloys contain Zr element.

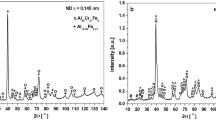

Microstructure characterization

Target alloy specimens were prepared by arc melting. Figure 7a shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the A1, A2, and A3 alloys. It can be seen that the corresponding crystal planes at 40°, 58°, 73°, and 87° are (110), (200), (211), and (220), respectively, which is consistent with the typical diffraction peaks of bcc_A2 structure13,49,50,51. Hence, it can be determined that all three target alloys are disordered bcc_A2 solid solution single phase. Figure 7c, d shows the backscattered electron images of the as-cast target alloys taken by electron probe micro-analyzer (EPMA) technique. All the as-cast target alloys exhibit a single-phase dendritic structure. A large number of dendrites were formed in the alloy, and secondary dendrites grew from both sides of the primary dendrites. Moreover, no signs of second phases are found, which is consistent with the results of XRD patterns. Therefore, the constructed prediction model of phase structures has 100% accuracy.

Table 2 lists the measured concentrations in the dendritic and inter-dendritic regions of the alloys. From the results in Table 2 and Fig. 7, it can be found that the high melting point elements (Nb and Mo) segregated in the lighter dendrites, whereas Al, Ti, and Cr elements were enriched in the darker inter-dendritic region. For the trace amounts element, the V content of inter-dendrite is slightly higher than that of dendrite in A1 alloy. But in A2 and A3 alloys, the V content in dendrite is rather higher. The EPMA results revealed that the average chemical composition of the as-cast alloys is close to the nominal value.

Property validation: hardness and corrosion test for LW-RHEAs

The theoretical density for disordered bcc solid solution could be calculated using the pure element density and mixtures rule. The values of the experimentally measured density ρexp and the calculated density ρmix of target alloys are listed in Table 3. The measured densities of A1, A2, and A3 target alloys are around 6.5 g/cm3, which meets the density requirement for LW-RHEAs11 (less than 8 g/cm3). There is no obvious difference between the measured and theoretical density, and the measured values are only slightly higher than the calculated values.

Microhardness of designed alloys is also tested and listed in Table 3. The hardness of the A1, A2, and A3 target alloys are 593.8 HV, 518.5 HV, and 507.4 HV, respectively. Compared to the predicted values of the hardness model, the prediction errors are all less than 5%, which further verifies the accuracy of the hardness model for LW-RHEAs. What’s more, the specific hardness (SH = Hardnessexp/ρexp) of the alloy was further calculated. Figure 8 demonstrates the hardness and SH of the target alloys, compared with the other bcc_A2 phase Al-Nb-Ti-V-Zr-Cr-Mo-Hf alloys. All the hardness of target alloys designed through the multi-objective screening is higher than 500 HV, which is superior to 95% of the reported alloy properties in literature. Moreover, for the A1 alloy, it has the lowest density (6.42 g/cm3) and highest hardness (nearly 600 HV) with SH up to 92.5 HV cm3/g. Compared to the hardest alloy in the experimental dataset, the alloy was significantly improved with 50 HV.

Dynamic potential polarization curves of A1–A3 target alloys in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at room temperature was plotted in Fig. 9a. Moreover, corrosion parameters (icorr, Ecorr, Epit, and ΔE) of A1, A2, and A3 LW-RHEAs were obtained through the Tafel linear extrapolation method, and they were shown in Table 4. It can be found that alloys formed a stable and wide passive zone (ΔE = Epit–Ecorr) larger than 2.5 V in NaCl solution. The passive film performance of target alloys is good and stable in comparison to most traditional alloys with a passive zone below 2 V21,52,53,54. All the alloys exhibit low icorr of 1.727 × 10–7, 7.442 × 10–8, and 9.097 × 10-8 A/cm2, respectively, which means that the LW-RHEAs have a low corrosion rate when the corrosion occurs. The general corrosion rate (rcorr) of alloys can also be calculated by using icorr values. As Table 4 reported, the corrosion rates of A1, A2, and A3 alloys are 1.021 × 10–3, 4.449 × 10–4, and 5.441 × 10–4 mm/y, respectively. Compared to other traditional HEAs with rcorr of 5 × 10–3 ~ 5 × 10–1 mm/y55,56,57,58, designed alloys have better corrosion resistance with a smaller corrosion rate. For comparison, the corrosion parameters of some reported HEAs53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60, LW-RHEAs13,15,21,61, BMGs62,63,64, and some traditional alloys13 in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution is shown in Fig. 9b. The smaller icorr value and the higher Epit of an alloy, the better the corrosion resistance is. It can be seen that the designed LW-RHEAs are located in the lower-right region and have lower current density and the highest pitting potential. The Epit of the alloys are all larger than 2 VSCE, especially for the A3 alloy, which has the largest Epit of 2.565 VSCE with excellent corrosion resistance.

Meanwhile, we examined and analyzed the surface morphology of the samples after the polarization test in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution and the results of A3 alloy with excellent pitting resistance are plotted in Fig. 10. It can be observed that typical pitting corrosion has occurred with wide and open pits on the surface of the alloy. From the backscattered image, it can be inferred that pitting corrosion preferentially forms in the darker inter-dendritic region due to the elemental segregation. During the corrosion process, the pits gradually expand so that the corrosive fluid can penetrate the interior of the alloy, and a clear dendritic structure is retained in the corroded area. Similar corrosion surface morphology was also observed in alloys A1 and A2, which can be seen in Figs. S1 and S2. Moreover, the elements area scanning result showed that the oxygen content on the alloy surface was 16 wt.% and uniformly distributed on the uncorroded surface. Oxides such as Al2O3, TiO2, Cr2O3, Nb2O5, etc. are formed on the surface of the alloy. These dense corrosion-resistant oxidized layers effectively enhance the corrosion resistance of the alloy.

Discussion

To further elucidate the relation between input features and output features, SHAP was introduced to explain the hardness model, which is a novel unified approach for interpreting model predictions. As illustrated in Fig. 4d, VEC and ΔHmix were recommended as the two most important features for alloy hardness. Higher VEC values and lower ΔHmix values are associated with higher SHAP values, indicating that these conditions favor high alloy hardness. Compared to the available literature data, all three designed alloys exhibit a combination of low ΔHmix and high VEC values, which makes them have superior experimental hardness (shown in Fig. S3). Meanwhile, for the target alloys, ΔHmix increased from –13.67 kJ/mol to –8.24 kJ/mol, while VEC values showed minimal change (Fig. 11a). Consistent with the SHAP analysis result, ΔHmix plays a decisive role in the hardness of alloys with similar VEC values, and alloy hardness increases as ΔHmix decreases. Alloy A1 has a maximum hardness of 593.8 HV. For further study, the variation of alloy properties with composition is also plotted in Fig. 11b, where Al and Ti elements show the most pronounced changes. With the Al contents of 8 at.%, 14 at.%, and 20 at.% for A3, A2, A1, respectively, the hardness of target alloys is increasing from 507.4 HV (A3) to 593.8 HV (A1). Similar trends were also observed in other studies7,44,65. Stepanov et al.66 and Yurchenko et al.35 studied the hardness of AlxNbTiVZr and AlxCrNbTiVZr alloys, finding that increasing Al content from 0 to 1.5 resulted in a hardness increase from 460 HV to 630 HV for AlxNbTiVZr and from 520 HV to 670 HV for AlxCrNbTiVZr. As shown in Table S5, the Al element has a larger negative enthalpy of mixing with other elements in the AlNbTiVCrMo system, which leads to a smaller ΔHmix value. Since Al had a much larger atomic radius in comparison with other constitutive elements. The lattice distortion becomes more significant, and the hardness is increased with the solid solution strengthening effect enhanced by adding Al element9.

Surprisingly, there is a strong trade-off relation between the hardness and the corrosion resistance of the alloy. The Epit of the alloy increases as the hardness decreases, which corresponds to a transition from the high hardness region to the high corrosion resistance region (as seen in Fig. 11). As excellent anti-corrosion elements, the 20 at.% Cr content guarantees a low icorr and excellent resistance to general corrosion for the three target alloys. The oxide film formed on the surface of the alloy, such as Al2O3, TiO2, Cr2O3, etc., plays an important role in resisting the attack of chloride ions. From A1 to A3 alloys, the reduction of Al content and the addition of high valence elements (Ti, Cr, and Mo) led to an increase in the VEC values of the alloys, which significantly enhanced their corrosion resistance. Especially, Ti4+ (i.e., TiO2 film) mainly improves its passivation and anti-pitting ability13. As a result, A3 alloys with the highest Ti content (34 at.%) exhibit the highest Epit of 2.565 VSCE. Moreover, the presence of Nb element is beneficial to promote the oxidation of Ti and inhibits the dissolution of Al67,68. Due to element segregation, the Nb content in the inter-dendrite region is lower than in the dendrite region, which may be the main reason for the formation of microscopic inhomogeneous corrosion (pitting occurs in the inter-dendritic region). In general, compared to conventional alloys and other HEAs, all three target alloys showed superior pitting resistance.

In conclusion, an ML-based alloy design strategy combined with a multi-objective optimization method was proposed and applied for a rational design of superb hard and superb corrosion-resistant LW-RHEAs in this work. The experimental results show that all three designed alloys are bcc_A2 single-phase with hardness and corrosion resistance properties far exceeding the literature data. The experimental measurements are in high agreement with the predicted results. Further analysis reveals that alloy hardness decreases with the decrease of Al content while pitting resistance improves with the increase of Ti content. The successfully designed LW-RHEAs with superb hardness and superb corrosion resistance should be the greatest candidate materials for the aerospace, marine, and chemical industries. Meanwhile, the successful demonstration in this paper indicates that the present design strategy driven by the ML technique should be generally applicable to other RHEA systems.

Methods

Feature construction and model evaluation

To build up the “composition-phase-property” quantitative relation of LW-RHEAs, thermodynamic parameters (ΔHmix, ΔSmix, Tm, and Ω), atomic size parameters (δr and γ), and electronic parameters (VEC, e/a, ΔχPauling, and ΔχAllen) was calculated by using the equations in Table S4, where ci denotes the content of each element in the alloy. These empirical parameters were also widely used in the phase structure and property prediction of HEAs systems such as FeCoCrNi, FeCoCrAlNiTi, WNbMoTaV, and TiZrHfNbTa69,70,71. The essential parameters of Al, Nb, Ti, V, Zr, Cr, Mo, and Hf elements for empirical calculations were listed in Table S5, including the enthalpy of mixing, melting point, atomic radius, valence electrons, electronegativity, density, and molar mass.

All the ML models and algorithms were achieved in Python by using the scikit-learn open source. To avoid unequal learning in the model caused by the different magnitude orders of feature variables, all input and output features were standardized. In the process of data feature screening and ML model selection, the training results and the prediction performance of different models vary greatly. To find the best combination of features and models, the model performance needs to be quantitatively evaluated.

For classification models, the prediction accuracy (Accuracy) metric was applied,

where TP, TN, FP, and FN represent the number of samples that were classified as True Positive, True Negative, False Positive, and False Negative.

For regression models, two metrics methods were utilized to evaluate the quality of ML models, i.e., the MAE and the determination coefficient (R2). The MAE measures the relative magnitude of deviation, while the R2 can be used to characterize the fitness level of the model (i.e., when R2 value is close to 1, the model has good performance). They are respectively defined as,

where y’ is the prediction value of the ith data, while yi is the corresponding actual value. Moreover, n is the size of the dataset.

Experimental method

The LRHEAs ingots with designed composition were prepared by vacuum arc melting in a high-purity argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation. All the samples were produced with high-purity raw element powders (>99.9 wt.%) and remelted at least 5 times to ensure a homogeneous distribution of elements.

The phase structure of as-cast target alloys was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Advance D8) using Cu Kα radiation with an accelerating voltage of 40 KV and a current of 40 mA. The diffraction angle (2θ) was in the range of 20°–100°, and the scanning rate was 2°/min. The microstructure and composition were analyzed by an electron probe micro-analyzer (EPMA, JXA-8530F).

Density was measured using the Archimedes method at room temperature with water as the immersion medium. The hardness was measured on polished surfaces with a 500 g load and a holding time of 15 s using a Vickers microhardness tester, and 5 points of each specimen were tested to evaluate the average hardness. The electrochemical properties of target alloys at room temperature were studied using the Princeton Versa STAT 4 electrochemical workstation. Potentiodynamic polarization measurements were carried out in a typical three-electrode cell setup with the built-in platinum plate as the auxiliary electrode, saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode, and the 10 × 10 × 3 mm LW-RHEAs sample as the working electrode. Polarization curve testing was performed at 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution with a scanning rate of 1 mV/s from an initial potential of –1.0 VSCE till the current density reached 0.01 A/cm3. The surface morphology of the target alloys after corrosion was observed by scanning electron microscope.

Empirical formula

The theoretical density for disordered bcc solid solution could be calculated using the pure element density and mixtures rule,

where ci, Ai, and ρi are the atom fraction, atomic weight, and density of the ith element in the alloy, respectively.

The general corrosion rate (rcorr) of alloys can be calculated by using icorr values, which can be obtained according to the following equations,

where ρ is the density of the alloy, EW is the alloy equivalent weight, which is given by:

where ni, fi, and Wi are the valence, atom fraction, and atomic weight of the ith element of the alloy, respectively.

Data availability

All data used in this study were list in Supplementary information.

Code availability

All codes used in this study will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

References

Yeh, J. W. et al. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: novel alloy design concepts and outcome. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6, 299–303 (2004).

Waseem, O. A. & Ryu, H. J. Powder metallurgy processing of a WxTaTiVCr high-entropy alloy and Its derivative alloys for fusion material applications. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–14 (2017).

Juan, C. et al. Enhanced mechanical properties of HfMoTaTiZr and HfMoNbTaTiZr refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 62, 76–83 (2015).

Senkov, O. N., Wilks, G. B., Miracle, D. B., Chuang, C. P. & Liaw, P. K. Refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 18, 1758–1765 (2010).

Jiang, W. et al. A lightweight Al0.8Nb0.5Ti2V2Zr0.5 refractory high entropy alloy with high specific yield strength. Mater. Lett. 328, 133144 (2022).

Giles, S. A., Sengupta, D., Broderick, S. R. & Rajan, K. Machine-learning-based intelligent framework for discovering refractory high-entropy alloys with improved high-temperature yield strength. NPJ Comput. Mater. 8, 235 (2022).

Jiang, W. et al. Effect of Al on microstructure and mechanical properties of lightweight AlxNb0.5TiV2Zr0.5 refractory high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 865, 144628 (2023).

Jayaraj, J., Thirathipviwat, P., Han, J. & Gebert, A. Microstructure, mechanical and thermal oxidation behavior of AlNbTiZr high entropy alloy. Intermetallics 100, 9–19 (2018).

Lou, L. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of lightweight AlxCrNbTiV(x=0.2, 0.5, 0.8) refractory high entropy alloys. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 104, 105784 (2022).

Li, T., Miao, J., Lu, Y., Wang, T. & Li, T. Effect of Zr on the as-cast microstructure and mechanical properties of lightweight Ti2VNbMoZrx refractory high-entropy alloys. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 103, 105762 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Light-weight refractory high-entropy alloys: a comprehensive review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 151, 41–65 (2023).

Chen, L., Wang, Y., Hao, X., Zhang, X. & Liu, H. Lightweight refractory high entropy alloy coating by laser cladding on Ti–6Al–4V surface. Vacuum 183, 109823 (2021).

Li, M., Chen, Q., Cui, X., Peng, X. & Huang, G. Evaluation of corrosion resistance of the single-phase light refractory high entropy alloy TiCrVNb0.5Al0.5 in chloride environment. J. Alloys Compd. 857, 158278 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Novel Ti-Zr-Hf-Nb-Fe refractory high-entropy alloys for potential biomedical applications. J. Alloys Compd. 906, 164383 (2022).

Tanji, A., Fan, X., Sakidja, R., Liaw, P. K. & Hermawan, H. Niobium addition improves the corrosion resistance of TiHfZrNbx high-entropy alloys in Hanks’ solution. Electrochim. Acta 424, 140651 (2022).

Qiu, Y. et al. A lightweight single-phase AlTiVCr compositionally complex alloy. Acta Mater. 123, 115–124 (2017).

Xiao, B. et al. Achieving thermally stable nanoparticles in chemically complex alloys via controllable sluggish lattice diffusion. Nat. Commun. 13, 4870 (2022).

Zhong, J., Chen, L. & Zhang, L. Automation of diffusion database development in multicomponent alloys from large number of experimental composition profiles. NPJ Comput. Mater. 7, 35 (2021).

Niu, Z., Wang, Y., Geng, C., Xu, J. & Wang, Y. Microstructural evolution, mechanical and corrosion behaviors of as-annealed CoCrFeNiMo (x = 0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1) high entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 820, 153273 (2020).

Chen, B., Li, X., Chen, W., Shang, L. & Jia, L. Microstructural evolution, mechanical and wear properties, and corrosion resistance of as-cast CrFeNbTiMox refractory high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 155, 107829 (2023).

Li, J., Yang, X., Zhu, R. & Zhang, Y. Corrosion and serration behaviors of TiZr0.5NbCr0.5VxMoy high entropy alloys in aqueous environments. Metals 4, 597–608 (2014).

Lu, Z., Chen, Z. W. & Singh, C. V. Neural network-assisted development of high-entropy alloy catalysts: decoupling ligand and coordination effects. Matter 3, 1318–1333 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Phase prediction in high entropy alloys with a rational selection of materials descriptors and machine learning models. Acta Mater. 185, 528–539 (2020).

Gao, J. et al. A machine learning accelerated distributed task management system (Malac-Distmas) and its application in high-throughput CALPHAD computation aiming at efficient alloy design. Adv. Powder Mater. 1, 100005 (2022).

Huang, X., Jin, C., Zhang, C., Zhang, H. & Fu, H. Machine learning assisted modelling and design of solid solution hardened high entropy alloys. Mater. Des. 211, 110177 (2021).

Gao, J. et al. Accelerated discovery of high-performance Al-Si-Mg-Sc casting alloys by integrating active learning with high-throughput CALPHAD calculations. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 24, 2196242 (2023).

Li, Z., Zhong, J., Jiang, X., Wang, Z. & Zhang, L. Accelerating LPBF process optimisation for NiTi shape memory alloys with enhanced and controllable properties through machine learning and multi-objective methods. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 19, e2364221 (2024).

Fu, H. et al. Breaking hardness and electrical conductivity trade-off in Cu-Ti alloys through machine learning and Pareto front. Mater. Res. Lett. 12, 580–589 (2024).

Yi, W., Gao, J. & Zhang, L. A CALPHAD thermodynamic model for multicomponent alloys under pressure and its application in pressurized solidified Al–Si–Mg alloys. Adv. Powder Mater. 3, 100182 (2024).

Gao, T., Gao, J., Zhang, J., Song, B. & Zhang, L. Development of an accurate “composition-process-properties” dataset for SLMed Al-Si-(Mg) alloys and its application in alloy design. J. Mater. Inform. 3, 6 (2023).

Yi, W., Liu, G., Gao, J. & Zhang, L. Boosting for concept design of casting aluminum alloys driven by combining computational thermodynamics and machine learning techniques. J. Mater. Inform. 1, 2 (2021).

Yi, W., Liu, G., Lu, Z., Gao, J. & Zhang, L. Efficient alloy design of Sr-modified A356 alloys driven by computational thermodynamics and machine learning. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 112, 277–290 (2022).

Senkov, O. N., Senkova, S. V., Miracle, D. B. & Woodward, C. Mechanical properties of low-density, refractory multi-principal element alloys of the Cr–Nb–Ti–V–Zr system. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 565, 51–62 (2013).

Zhi, Q. et al. Effect of Zr content on microstructure and mechanical properties of lightweight Al2NbTi3V2Zrx high entropy alloy. Micron 144, 103031 (2021).

Yurchenko, N. Y. U., Stepanov, N. D., Shaysultanov, D. G., Tikhonovsky, M. A. & Salishchev, G. A. Effect of Al content on structure and mechanical properties of the AlxCrNbTiVZr (x=0; 0.25; 0.5; 1) high-entropy alloys. Mater. Charact. 121, 125–134 (2016).

Yu, T. et al. Mo20Nb20Co20Cr20(Ti8Al8Si4) refractory high-entropy alloy coatings fabricated by electron beam cladding: Microstructure and wear resistance. Intermetallics 149, 107669 (2022).

Jayaraj, J., Thinaharan, C., Ningshen, S., Mallika, C. & Kamachi Mudali, U. Corrosion behavior and surface film characterization of TaNbHfZrTi high entropy alloy in aggressive nitric acid medium. Intermetallics 89, 123–132 (2017).

Yang, X. & Zhang, Y. Prediction of high-entropy stabilized solid-solution in multi-component alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 132, 233–238 (2012).

Zhu, M. et al. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of a novel CrNbTiZrAlx (0.25 ≤ x ≤ 1.25) eutectic refractory high-entropy alloy. Mater. Lett. 272, 127869 (2020).

Qiao, D. et al. The mechanical and oxidation properties of novel B2-ordered Ti2ZrHf0.5VNb0.5Alx refractory high-entropy alloys. Mater. Charact. 178, 111287 (2021).

Huang, T. et al. Effect of Ti content on microstructure and properties of TixZrVNb refractory high-entropy alloys. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 27, 1318–1325 (2020).

Zhang, X. K. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Tix(AlCrVNb)100-x light weight multi-principal element alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 831, 154742 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Effects of Zr content on the microstructure and performance of TiMoNbZrx high-entropy alloys. Metals 11, 1315 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Effect of Al addition on structural evolution and mechanical properties of the AlxHfNbTiZr high-entropy alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 16, 242–249 (2018).

Qiao, D. et al. A novel series of refractory high-entropy alloys Ti2ZrHf0.5VNbx with high specific yield strength and good ductility. Acta Metall. Sin. Engl. Lett. 32, 925–931 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Microstructure evolution and properties of NiTiCrNbTax refractory high-entropy alloy coatings with variable Ta content. J. Alloys Compd. 891, 161756 (2022).

Yurchenko, N. Y. U. et al. Effect of Cr and Zr on phase stability of refractory Al-Cr-Nb-Ti-V-Zr high-entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 757, 403–414 (2018).

Tan, X. R. et al. Effects of milling on the corrosion behavior of Al2NbTi3V2Zr high-entropy alloy system in 10% nitric acid solution. Mater. Corros. 68, 1080–1089 (2017).

Lee, K. et al. Development of precipitation-strengthened Al0.8NbTiVM (M = Co, Ni) light-weight refractory high-entropy alloys. Materials 14, 2085 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. A single-phase V0.5Nb0.5ZrTi refractory high-entropy alloy with outstanding tensile properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 792, 139774 (2020).

Stepanov, N. D., Yurchenko, N. Y. U., Panina, E. S., Tikhonovsky, M. A. & Zherebtsov, S. V. Precipitation-strengthened refractory Al0.5CrNbTi2V0.5 high entropy alloy. Mater. Lett. 188, 162–164 (2017).

Zhao, Q. et al. Corrosion and passive behavior of AlxCrFeNi3−x (x = 0.6, 0.8, 1.0) eutectic high entropy alloys in chloride environment. Corros. Sci. 208, 110666 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. Corrosion of AlxCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys: Al-content and potential scan-rate dependent pitting behavior. Corros. Sci. 119, 33–45 (2017).

Shi, Y. et al. Homogenization of AlxCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys with improved corrosion resistance. Corros. Sci. 133, 120–131 (2018).

Raza, A., Abdulahad, S., Kang, B., Ryu, H. J. & Hong, S. H. Corrosion resistance of weight reduced AlxCrFeMoV high entropy alloys. Appl. Surf. Sci. 485, 368–374 (2019).

Lu, C., Lu, Y., Lai, Z., Yen, H. & Lee, Y. Comparative corrosion behavior of Fe50Mn30Co10Cr10 dual-phase high-entropy alloy and CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy in 3.5wt% NaCl solution. J. Alloys Compd. 842, 155824 (2020).

Han, Z. et al. The corrosion behavior of ultra-fine grained CoNiFeCrMn high-entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 816, 152583 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Yuan, T. & Li, R. Corrosion performance of selective laser-melted equimolar CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy vs its cast counterpart in 3.5wt% NaCl. J. Alloys Compd. 864, 158105 (2021).

Parakh, A., Vaidya, M., Kumar, N., Chetty, R. & Murty, B. S. Effect of crystal structure and grain size on corrosion properties of AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 863, 158056 (2021).

Chou, Y. L., Yeh, J. W. & Shih, H. C. The effect of molybdenum on the corrosion behaviour of the high-entropy alloys Co1.5CrFeNi1.5Ti0.5Mox in aqueous environments. Corros. Sci. 52, 2571–2581 (2010).

Huang, Y., Wang, Z., Xu, Z., Zang, X. & Chen, X. Microstructure and properties of TiNbZrMo high entropy alloy coating. Mater. Lett. 285, 129004 (2021).

Ma, X. H., Zhang, L., Yang, X. H., Li, Q. & Huang, Y. D. Effect of Ni addition on corrosion resistance of FePC bulk glassy alloy. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 50, 433–437 (2015).

Hua, N. et al. Effects of crystallization on mechanical behavior and corrosion performance of a ductile Zr68Al8Ni8Cu16 bulk metallic glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 529, 119782 (2020).

Gu, J., Shao, Y., Shi, L., Si, J. & Yao, K. Novel corrosion behaviours of the annealing and cryogenic thermal cycling treated Ti-based metallic glasses. Intermetallics 110, 106467 (2019).

Liao, Y. C. et al. Effect of Al concentration on the microstructural and mechanical properties of lightweight Ti60Alx(VCrNb)40-x medium-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 135, 107213 (2021).

Stepanov, N. D., Yurchenko, N. Y. U., Shaysultanov, D. G., Salishchev, G. A. & Tikhonovsky, M. A. Effect of Al on structure and mechanical properties of AlxNbTiVZr (x=0, 0.5, 1, 1.5) high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 1184–1193 (2015).

Dai, J. et al. The effect of Nb and Si on the hot corrosion behaviors of TiAl coatings on a Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Corros. Sci. 168, 108578 (2020).

Yang, Y. J. et al. Effect of Nb content on corrosion behavior of Ti-based bulk metallic glass composites in different solutions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 471, 108–117 (2019).

Pritam, M., Amitava, C., Amitava Basu, M. & Manojit, G. Phase prediction in high entropy alloys by various machine learning modules using thermodynamic and configurational parameters. Met. Mater. Int. 29, 38–52 (2023).

Klimenko, D., Stepanov, N., Li, J., Fang, Q. & Zherebtsov, S. Machine learning-based strength prediction for refractory high-entropy alloys of the Al-Cr-Nb-Ti-V-Zr system. Materials 14, 7213 (2021).

Zhu, W. et al. Phase formation prediction of high-entropy alloys: a deep learning study. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 18, 800–809 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province for Distinguished Young Scholars, China [Grant No. 2021JJ10062], the Science and Technology Program of Guangxi province, China [Grant No. AB21220028], the Youth Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 52401047, Grant No. 52401004], the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, China [Grant No. 2023M741244], and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University, China [Grant No. 2023ZZTS0711] are acknowledged. The Project supported by State Key Laboratory of Powder Metallurgy, Central South University, Changsha, China is also acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Zhang L; Dataset, Gao T and Yang S; Machine Learning, Gao T and Gao J; Experiment Analysis, Gao T and Gao J; Manuscript, Gao T; Review & Editing, Zhang L and Gao J; Supervision, Zhang L

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41524_2024_1457_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary material of Data-driven design of novel lightweight refractory high-entropy alloys with superb hardness and corrosion resistance

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, T., Gao, J., Yang, S. et al. Data-driven design of novel lightweight refractory high-entropy alloys with superb hardness and corrosion resistance. npj Comput Mater 10, 256 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01457-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01457-6

This article is cited by

-

Accurate and uncertainty-aware multi-task prediction of HEA properties using prior-guided deep Gaussian processes

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

Unveiling the impact of Al and Cr alloying on structure and HER performance of CoCuZnMnNiFe high-entropy alloy nanoparticles

Journal of Materials Science (2025)

-

On the work hardening behavior of machining WNbMoTaZrx (x = 0.5 and 1.0) refractory high entropy alloys

Journal of Materials Science (2025)

-

Enhanced Mechanical and Corrosion-Resistant Properties of Medium-Entropy Alloys via Micro-oxygen Solid Solution Strengthening

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A (2025)