Abstract

Abnormal grain growth (AGG) in polycrystalline microstructures, characterized by the rapid and disproportionate enlargement of a few “abnormal” grains relative to their surroundings, can lead to dramatic, often deleterious changes in the mechanical properties of materials, such as strength and toughness. Thus, the prediction and control of AGG is key to realizing robust mesoscale materials design. Unfortunately, it is challenging to predict these rare events far in advance of their onset because, at early stages, there is little to distinguish incipient abnormal grains from “normal” grains. To overcome this difficulty, we propose two machine learning approaches for predicting whether a grain will become abnormal in the future. These methods analyze grain properties derived from the spatio-temporal evolution of grain characteristics, grain-grain interactions, and a network-based analysis of these relationships. The first, PAL (Predicting Abnormality with LSTM), analyzes grain features using a long short-term memory (LSTM) network, and the second, PAGL (Predicting Abnormality with GCRN and LSTM), supplements the LSTM with a graph-based convolutional recurrent network (GCRN). We validated these methods on three distinct material scenarios with differing grain properties, observing that PAL and PAGL achieve high sensitivity and precision and, critically, that they are able to predict future abnormality long before it occurs. Finally, we consider the application of the deep learning models developed here to the prediction of rare events in different contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Abnormal grain growth (AGG) is a ubiquitous phenomenon in both bulk and thin-film polycrystals in which a minority of “abnormal” grains enlarges rapidly relative to the surrounding “normal” grains. After some time, the associated bimodal grain size distribution differs from the skewed, mono-modal distribution observed in normal grain growth (NGG)1. AGG is a rare event2 and may be caused by various factors, including local variations in the energies and/or mobilities of grain boundaries, the presence of impurities (e.g., Ca in Al2O3)3, and phase-like boundary (i.e., complexion) transitions4,5,6, which can endow certain grains with a growth advantage. In many cases, the resulting heterogeneous microstructures exhibit a degradation of mechanical properties, such as hardness7, while, in other instances, AGG may be beneficial in mitigating fracture8 or in optimizing the magnetic properties of some steels9. Based on these considerations, it would clearly be desirable to be able to predict which grains in a microstructure will eventually become abnormal and to make this prediction substantially in advance of abnormality. This capability would also reveal key microstructural features that are salient precursors of AGG.

Unfortunately it is difficult to collect sufficient experimental AGG data for use in predictive models. First, the processes that confer a growth advantage on certain grains (e.g. the nucleation of boundary complexions) are spatio-temporally random. Indeed, in a microstructural simulation with pinning particles, Holm et al. estimated that approximately 1 in 22, 000 grains grows abnormally large10. Second, the rapid growth of an abnormal grain can obscure the precursors of its transition to abnormality, making the transition process difficult to observe. Finally, despite recent advances in in-situ observations of coarsening dynamics, particularly in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies of metallic thin films11, it remains challenging to obtain enough grain growth data to draw statistically significant conclusions about microstructural kinetics. In some cases (e.g., bright-field TEM images), delineating grain boundaries in microstructural images is itself difficult owing to complex diffraction contrasts, and so considerable effort is required to automate boundary detection12 and find abnormal grains.

While experimental data may be difficult to acquire in quantity, summary observations about real systems can still inform generic predictive models. For example, Rios et al. identified deterministic and probabilistic factors that contribute to the development of AGG from uniform grain size distributions2. At about the same time, Bae et al. reported that AGG in alumina is an extrinsic result initiated by impurities (e.g., silica) leading to the formation of intergranular glass films and the sudden appearance of abnormal grains, with experimental evidence showing an inverse relationship between silica concentration and average grain sizes13. Omori et al. reported a crystal growth method that employs only a cyclic heat treatment to obtain grains larger than a millimeter14. Finally, and more recently, inspired by the use of extreme-value statistics to quantify rare events in allied disciplines, Lawrence et al.15 described a set of practical maps and metrics that are useful in quantifying microstructural features that are associated with AGG.

Given the difficulties in obtaining time-series data of evolving microstructures from in-situ microscopy, it is useful to ask whether one can predict AGG from synthetic microstructures that can be readily generated from generic grain growth models. Such coarse-grained descriptions are inherently simplified because they do not, for example, directly model atomic-level processes, but they do, nevertheless, provide useful insights into the physics underlying AGG. For example, simulations based on phase-field methods produce accurate triple-junction angles16 as well as kinetic and topological features17 of coarsening structures. In addition, a model based on cellular automata was found to have topological features that closely fit those of succinonitrile polycrystals18. Other simulative approaches to grain growth include a level-set finite element method19 and the Monte Carlo Potts model (MCP)20. Finally, motivated by observations of complexion-transition-induced AGG in Eu-doped MgAl2O4, these models have recently been generalized to include such transitions21 and, given their utility in linking boundary transitions and subsequent grain growth, we employ them here.

Recently, deep learning techniques have been applied to model the effect of normal grain growth in two dimensions. Notably, Yan et al. built PRIMME, a physics-regularized interpretable machine learning model that predicts the future shape and position of grains in a microstructure as they coarsen under normal, isotropic grain growth. PRIMME produced predictions that resembled outcomes from MCP and phase-field simulations22. Melville et al. improved on PRIMME with APRIMME, using an anisotropic refinement to better predict coarsened appearances relative to MCP23. Yang et al. proposed a recurrent neural network that extrapolates a coarsening microstructure into the future, demonstrating similarity to phase-field simulations24.

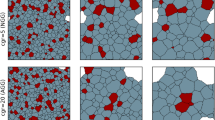

Based on these findings, it is clear that both microstructural simulation and deep learning are able to reproduce many generic characteristics of normal grain growth. Our aim here is different. We seek to predict whether a selected grain will later become abnormal in an evolving microstructure. The challenge associated with making this prediction can be seen in Fig. 1, which illustrates the growth of a selected grain relative to a time sequence of snapshots from a simulated microstructure. Our approach is to employ local microstructural characteristics from a few early time steps in the three dimensional (3D) simulation, as they relate to a selected grain (such as the red grain in Fig. 1), to predict whether the grain will later become abnormally large.

Cross-sections of the simulation are shown every 10M MCS (Monte Carlo steps). The highlighted (red) grain becomes abnormally large (i.e., having a grain volume that is greater than 10 times the initial average grain volume) just after 67M MCS. Our methods predicted that this grain would become abnormal using only the data from 11M to 15M MCS (bracket at left), which is long before abnormality occurs.

To address this problem, we have developed and evaluated the performance of two deep learning models that will be shown to be capable of predicting future abnormality in specific grains. The first method is based on a long short-term memory (LSTM) network, called PAL (Predicting Abnormality with LSTM), and the second method is an enhanced version of PAL with a graph-based convolutional recurrent neural (GCRN) network in addition to the LSTM, called PAGL (Predicting Abnormality with GCRN and LSTM). PAGL represents the microstructure as an evolving graph that is updated at a fixed frequency over the course of a simulation. As input, both PAL and PAGL accept a grain of interest and five consecutive time steps from an MCP simulation, and they produce a prediction as to whether the grain will become abnormal in the future. The microstructural data used here are generated with the aforementioned modified MCP with stochastic complexion transitions occurring at individual grain boundaries and attendant changes in boundary mobility that have been shown to produce AGG21,25.

In our analysis, we quantify how sensitively and precisely these methods can predict whether a grain will become abnormal in the future. As we are unaware of any comparable benchmarks, we compare the performance of PAL and PAGL with each other. We also assess how far in advance these methods can predict abnormality before it occurs in the simulation, and examine the importance of each microstructural feature in making these predictions effectively. The capabilities described here point to novel applications in computed diagnostics that anticipate AGG in the future, providing an early warning for materials processing and life-cycle evaluation protocols. In the Discussion section, we explore the extension of the methods described here to other rare event predictions.

Results

We begin with a short summary of the simulations, representations and models used herein to describe AGG before highlighting the prediction of grain abnormality. Additional details may be found in the Methods section.

Simulations, representations, and models

Simulations

PAL and PAGL are trained on snapshots of 3D MCP simulations of spatially periodic 150 × 150 × 150 voxel microstructures generated using a modified Q-state Potts model. We refer to it as a “modified” MCP simulation because grain boundary phase (complexion) transitions26 are modeled as stochastic events that enhance grain-boundary mobility. Specifically, the simulation assumes that complexions nucleate at random grain boundaries at a specified, temperature-dependent rate and then spread to adjacent boundaries by a double-adjacency mechanism, as proposed by Frazier et al.25 and subsequently by Marvel et al.21. The resulting mobility increases lead, in some cases, to AGG. Consistent with existing convention21, we define a grain as abnormal if its volume (i.e., the total number of voxels per grain) is greater than or equal to ten times the mean grain volume associated with the initial microstructure. We note that the criterion for establishing abnormality is, of course, to some extent arbitrary, and that the time scale of the simulation is an important consideration in quantifying abnormality. In practice, we have found that the aforementioned criterion permits us to differentiate abnormal grains from normal grains over a significant portion of the simulation time. (See the Methods section for additional details about the simulation methodology.)

Since grain curvature partly dictates average grain velocity, we wished to evaluate the effect of varying curvatures on our capacity to predict future abnormality. We created randomized initial microstructures that fall into three “scenarios” with distinct degrees of curvature. These initial microstructures were created with a Voronoi tessellations27 based on N = 5247 generators located at random points \(P=\left\{{\overrightarrow{x}}_{1},{\overrightarrow{x}}_{2},\cdots \,,{\overrightarrow{x}}_{N}\right\}\). Each generator was associated with weights \({w}_{1}=\left\{{w}_{11},{w}_{21},\cdots \,,{w}_{N1}\right\}\) and \({w}_{2}=\left\{{w}_{12},{w}_{22},\cdots \,,{w}_{N2}\right\}\), and the tessellation is dictated by the distance function

The associated initial microstructural scenarios are: the “unweighted” Voronoi tessellation (wi1 = 1; wi2 = 0), the “additively-weighted” tessellation (wi1 = 1, wi2 = {1, 2}), and the “multiplicatively-weighted” tessellation (wi1 = {1, 2}, wi2 = 0)27. For each scenario, pairs of values in curly braces indicate a choice of two values to be selected randomly.

These scenarios mimic different nucleation and growth conditions. An unweighted tessellation results from site-saturation nucleation conditions with a constant rate of grain growth28 to impingement, and an additively-weighted tessellation can describe nucleation at a constant rate with an associated constant rate of grain growth29. As seen in Fig. 2a, these distinct scenarios result in different values of the normalized integral mean curvature, Ms = M/V1/3, where V is a grain volume. Since Ms is dictated in part by dihedral angles and lengths associated with grain triple-lines that do not contribute to the driving force for grain growth, following existing conventions30, we omit these triple-lines from the calculation and refer to it as the modified normalized curvature, \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\). Having three initial scenarios permits a more general evaluation of PAL and PAGL performance. To compute non-equilibrium average quantities for each scenario, 50 independent initial configurations were randomly generated and each configuration evolved for 100 × 106 or 100M MCS (million Monte Carlo steps).

a A series of snapshots illustrating the grains in an evolving microstructure starting from a multiplicatively weighted Voronoi tessellation. Distinct grains are labeled with a unique color. Note that some grains eventually become abnormally large. b Contour plots of the modified normalized curvature, \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\), versus the logarithm of the relative grain volume \({V}^{{\prime} }=V/\bar{V}\). Each plot is computed from the snapshot above it. c Whisker plots of \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\) versus the number of grain neighbors, D. Each plot is computed for the snapshot above it in row a. The grey vertical line denotes D = 14.

For the purposes of illustration, consider a microstructure that evolves via coarsening from a multiplicatively-weighted initial tessellation. Figure 2a shows a time sequence of snapshots over 100M MCS. The corresponding dependence of \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\) on the relative grain volume \({V}^{{\prime} }=V/\bar{V}\), where \(\bar{V}\) is the average initial volume of a grain, is shown in Fig. 2b for all grains comprising the microstructure at a given time. The values for \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\) were obtained using the so-called “Innie/Outie” method developed by Patterson31 and outlined in the Method section. It should be noted that, at late times, the contours representing these data shift to larger values of \({V}^{{\prime} }\) and become more diffuse, indicating that the average grain size has increased markedly and that there is wide variation in modified normalized curvature. Figure 2c shows the dependence of \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\) on the number of grain neighbors, D. As is evident from the figure, grains with \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }=0\) correspond to D ≈ 14 neighbors, in agreement with previous studies21.

Finally, it is useful to illustrate how the three scenarios differ in their initial states and how these differences influence subsequent microstructural evolution. Figure 3a highlights the dramatic log-scale differences between the relative volumes of grains in initial and final microstructures, across all scenarios. Subtler variations in grain volume, due to different initial scenarios, are visible at early times but are much less pronounced at late times. In Fig. 3b one can see the substantial evolution of the median modified normalized curvature, which is 0.44 in the initial state, towards much larger positive values in the final state. The multiplicatively-weighted scenarios exhibited a greater variance in curvatures relative to the other scenarios, in both initial and final states. These results demonstrate that there are distinctive differences between both initial and evolved microstructures that are introduced by the three weighting scenarios. For completeness, a summary of the characteristics of the abnormal grains produced during the simulations for the three initial scenarios is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a The distribution of the logarithm of relative grain volume, \({V}^{{\prime} }\), in initial and final states of the simulation. The dotted red vertical line indicates the logarithm of the threshold for a grain to be considered abnormal, indicating the clear differences between initial and final states. The distribution of the logarithm of \({V}^{{\prime} }\) for the microstructures under normal grain growth without complexion transitions showed at 0M MCS (dark grey), 100M MCS (medium grey), 200M MCS (light grey) are plotted in dashed-dotted lines. b The distribution of modified normalized curvature, \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\), in initial and final states of the simulation, illustrating the substantial change in aggregate grain curvature during the simulation. In both plots, data for initial (solid lines) and final (dashed lines) time steps are plotted for the unweighted Voronoi (blue), additively-weighted Voronoi (orange) and multiplicatively-weighted Voronoi (green) scenarios.

Representations

PAL and PAGL are trained on feature vectors that describe individual grains and their neighborhoods. These features include the relative grain volume, \({V}^{{\prime} }\), the average volume of neighboring grains, VN, the number of grain neighbors, D, the modified normalized curvature, \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\), the integral grain velocity, v, and the maximum and minimum boundary velocities, vmax and vmin. It is perhaps worth noting here that size-advantage (\({V}^{{\prime} }\)) alone cannot be used as a reliable future predictor of AGG, as has been demonstrated by earlier studies32. Since our approach is focused on the evolution of grain features over time, all features are collected at regular intervals, namely once every 1M MCS. Intervals of five such time steps are called the “dynamic features” of a given grain.

Given that the characteristics of grains change over the course of the simulation, and that grains become abnormal at very different times, it is advantageous to collect the dynamic features of each grain using two binning strategies. In “chronological binning”, dynamic features across multiple simulations are grouped in the same 5M MCS intervals of simulation time. Training PAL and PAGL on grains from the same chronological bin allows us to compare how features from specific periods in the simulation contribute to predicting future abnormality. We hypothesize that features collected early in the simulation (e.g., prior to 15M MCS), where most grains remain normal, will train very different classifiers than will features collected at much later times (e.g., between 80M MCS-85M MCS) where most surviving grains are abnormal. In “asynchronous binning”, for all grains that become abnormal, we begin collecting features from the time step tab, when abnormality occurs for a given grain. Stepping backwards in 5 M MCS intervals until the beginning of the simulation, the bins from − 1 M to − 5 M MCS before tab, from − 6 M to − 10 M MCS before tab, and so on, describe cohorts of grain features that have similar amounts of time before they become abnormal. We refer to the interval between tab and the beginning of the simulation as the “pre-abnormality interval”. We hypothesize that by binning grains with a similar amount of time before abnormality, our models will train on features that are characteristic of different stages in the evolution towards abnormality, and enable us to probe how far in advance we can predict abnormality. We emphasize here that in constructing asynchronous bins it is critical to balance the contents of these bins with an equal number of normal and abnormal grains, as discussed in the Methods section. In this way the models can learn to distinguish among various grain growth trajectories at different times, detect precursors to abnormality and classify the evolving grains appropriately.

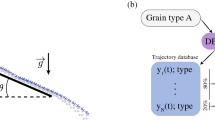

PAL uses only the dynamic features as the microstructure evolves, while PAGL adds graph-based adjacency information for each time step. The adjacency information used by PAGL represents a microstructure as an evolving graph that is updated every 1M MCS. In this scheme, each grain is represented as a graph node (or vertex), and grain-grain adjacency is described with edges between nodes. The graph for the full microstructure is updated once every 1M MCS in conjunction with grain feature updates. To produce a feature for each grain xi on a given time step, the set of all grains that share a boundary with xi is identified, and their pairwise adjacencies are stored in a “local graph”. These local graphs can then be viewed as grain-specific “topological features” that exist at every time step and can therefore be organized via chronological or asynchronous binning. Figure 4 illustrates a local graph for a 2D microstructure with 7 grains as an example.

Grains are represented as nodes and grain boundaries are edges in the graph in the right panel. The d different physical features (d = 7 herein) of each grain are stored in a feature vector for each node and combined in a feature matrix X. Adjacency relationships between grains are stored in an adjacency matrix A, yielding a graph representation G = (X, A).

Deep learning models

PAL uses the dynamic features of individual grains without topological features to predict abnormality. The LSTM model employed by PAL is a special class of recurrent neural networks designed to prevent rapid gradient vanishing. This architecture has demonstrated stability and effectiveness in capturing long-range dependencies across a variety of general-purpose sequence modeling tasks33,34. A fully-connected LSTM (FC-LSTM)35 is regarded as a multivariate version of LSTM where the feature input \({X}_{tj}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) at tth timestep and jth grain, cell output \({h}_{t}\in {[-1,1]}^{{d}_{h}}\) and states \({c}_{t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{h}}\) are all vectors, and dh denotes the hidden dimension. The FC-LSTM formulation is expressed as

where \(i,f,o\in {[0,1]}^{{d}_{h}}\) are the input, forget, and output gates in LSTM architecture, ⊙ denotes the element-wise product, σ denotes the sigmoid function. The weights \({W}_{.}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{h}\times d}\), \({W}_{.}^{{\prime} }\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{h}\times {d}_{h}}\), \({w}_{.}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{h}}\), and biases \({b}_{i},{b}_{f},{b}_{c},{b}_{o}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{h}}\) are learned in the training. The fully-connected layer with the learnable weights W. and \({W}_{.}^{{\prime} }\) linearly project the components of feature vector xt and hidden vector ht onto a high-dimensional space, which is beneficial for feature learning.

We also considered a graph convolutional recurrent network, shown schematically in Fig. 5, by including both dynamic features and the topology of time-dependent grain interactions to predict abnormality.

a Voxel grains are represented by multiple time-varying microstructures as an example. Each grain is assigned a unique color and a number. b Microstructures are transferred to graph representations that describe adjacency relations between grains and the dynamic features (rectangles at right). c Graphs are input into three graph-based convolutional network (GCN) layers to learn the local topology from one-hop, two-hop, and three-hop neighbors, and update the individual node (grain) features. d The long short-term memory (LSTM) module with multiple cells learns the topological and featured variation of different time steps. e Finally, the learned node (grain) representations in the graph are fed into an multilayer perceptron (MLP classifier) with a sigmoid function to predict the probability of becoming abnormal. f The framework outputs the prediction that a grain will become abnormal or not. (Predicting Abnormality with LSTM) (PAL) is a simplification of this diagram: It does not build dynamic graphs in (b) and it passes dynamic features directly to the LSTM module (d) to learn grain representations that are fed into an MLP classifier to predict abnormality.

PAGL incorporates both dynamic and the topological features and the associated architecture comprises three types of layers: graph convolutional layers, an LSTM layer, and a multilayer perceptron (MLP) layer. A Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) aggregates the topological information and embeds node-level features into a low dimensional space36. In this context, the low-dimensional embedding captures not only the dynamic features of the grains but also their adjacency. In the architecture employed here, the graph convolutional layer \({\mathcal{G}}\) recursively learns a node representation by transforming and aggregating the neighboring feature vectors. Mathematically, the propagation update of a node representation at the tth time step (tth dynamic graph) can be calculated by graph convolution \({\mathcal{G}}\) as follows:

where N(t, i) denotes the set of neighboring indices of node i, \({h}_{ti}^{l}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{l}}\) is the hidden representation of node i at time t in the lth graph convolution layer, dl is the number of output channels at layer l, and relu is the activation function. The first graph convolution starts from the feature matrix by setting \({h}_{ti}^{0}={X}_{ti}\). We define that \({W}^{l}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{l+1\times }{d}_{l}}\) are the learnable parameters, and eij are the connectivity features associated with the edge from node i to node j at time t. Note that, for the unweighted graph, eij is set to 1 when there is a connection (e.g. grain adjacency) between node i and node j, and is otherwise 0. We add self-loops into the adjacency matrix and normalize the edge weights by eij = eij/∑j∈N(t, i)eij based on the aggregation mechanism. In graph convolution \({\mathcal{G}}\), we use multiple layers to learn the multi-hop neighboring information for each node.

Finally, we use graph convolution \({\mathcal{G}}\) to learn the feature matrix Xtj at the current timestep, and hidden output ht−1 from the previous timestep. Next, we feed the feature learned from \({\mathcal{G}}\) into an LSTM model to update the current hidden representation \(\widetilde{{h}_{t}}\). The GCN formulation based on learning both the current feature matrix and previous hidden output in the jth grain is expressed as

where the parameters have the same definitions and dimensions as in the FC-LSTM formulation, except that weights \({W}_{.}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{h}\times {d}_{L}}\) and \(\widetilde{{h}_{t}}\) is the learned hidden state for the grain j and time step t. This formulation first learns the local graph of interactions between grains and next the evolving graph-based variation between time steps, which significantly affects the prediction of abnormal grains. After learning the dynamic graphs by graph convolutional recurrent networks, we fed the learned hidden state of the final timestep in a specific interval into a multi-layer perception (MLP) classifier with a sigmoid function to predict the abnormality. Additional details regarding the simulations, initial microstructures, grain features, and training methodology are provided in the Methods and Supplementary Materials sections.

Predicting future abnormality with PAL and PAGL

We first evaluated PAL performance in predicting future grain abnormality using 50 independent simulations for each microstructural scenario. For this purpose, sensitivity and precision scores were extracted from the evolving confusion matrix resulting from the analysis. Chronological bins were generated to divide the dynamic grain feature data from all simulations of each scenario into distinct 5M MCS intervals and PAL was then trained on each bin. Training and testing followed a five-fold cross-validation protocol. As seen in Fig. 6a, the sensitivity score of PAL increased from 0.06 to 1.00 for chronological bins arranged in advancing order. These findings indicate that features gathered from later in the simulation are better predictors of future abnormality. Precision scores computed for the same intervals remained steadily above 0.82 for all time steps, indicating that the ratio of the number of incorrectly predicted abnormal grains to the number of true abnormal grains was consistently small. Specificity is never measured because of the very large number of normal grains (e.g. true negatives).

Sensitivity (solid lines) and precision scores (dashed lines) for the (a) PAL (Predicting Abnormality with LSTM) and (b) PAGL (Predicting Abnormality with GCRN and LSTM) methods when predicting that grains in a given chronological bin will become abnormal. The results are shown here for unweighted Voronoi (blue), additively-weighted Voronoi (orange) and multiplicatively-weighted (green) initial conditions. For clarity, every other number of the abscissa indicates the final bin time step.

PAGL performance was evaluated in the same way, compiling sensitivity and precision scores while training it on advancing chronological bins. Figure 6b illustrates that the sensitivity scores for PAGL also increased from 0.09 to 1.00 over bins arranged in chronological order, with values superior to that of PAL for some scenarios prior to 40 M MCS. These results confirm the added value of the topological data for making predictions about future abnormality in early periods of a simulation, when differences between grains that will become abnormal and those that will always be normal are not obvious. Note that precision scores remained steadily above 0.86 after 20M MCS for all scenarios.

Predicting abnormality before it occurs

To determine how far in advance PAL and PAGL can predict the occurrence of grain abnormality, for each initial scenario, we trained them on a range of asynchronous bins from 1M to 65M MCS prior to abnormality (Fig. 7). The limitation to 65M MCS prior to abnormality arises from the fact that, for almost every grain that eventually becomes abnormal, the beginning of the simulation is at most 65M MCS before the time when it becomes abnormal. Thus, the absence of data before 65M MCS prior to abnormality (see Fig. 7a and b), reflects that there are insufficient grains that are older than 65M MCS when they become abnormal to train the model.

Sensitivity (solid lines) and precision scores (dashed lines) versus time to abnormality for the PAL (Predicting Abnormality with LSTM) (a) and PAGL (Predicting Abnormality with GCRN and LSTM) (b) methods, when predicting that grains in a given asynchronous bin will become abnormal. The results are shown here for unweighted (blue), additively-weighted (orange) and multiplicatively-weighted (green) initial conditions. In addition, the time dependence of the number of abnormal grain is displayed (pink symbols) for unweighted (plus sign), additively-weighted (filled circle) and multiplicatively-weighted (filled triangle) initial conditions. For clarity, every other number in the horizontal axis indicates the final time step of the bin.

The results of this training are summarized in Fig. 7. It is evident that PAL exhibited sensitivity scores above 0.81 in bins up to 65M MCS prior to grain abnormality, gradually rising to 100% closer to the abnormality time. For comparison, PAGL exhibited sensitivity scores above 0.83 in bins up to 65M MCS, and both methods evinced relatively high precision scores (0.76) over time for all initial scenarios. These findings demonstrate that PAL and PAGL sensitively and precisely predict future abnormality well before its occurrence.

We can now assess the predictive capability of these methods. Since grains become abnormal at different times, it is useful to quantify this capability in terms of the percentage of a grain’s pre-abnormality interval, from 0 to flife = (t/tab) × 100, where t is pre-abnormal time predicted by our methods and tab is the time when abnormality occurs. Figure 8 show the number of abnormal grains predicted at the earliest points in their lifespan, fpred, as a function of flife for the three initial scenarios. Also shown is the cumulative fraction of abnormal grains predicted, fcum, as a function of fpred. As is evident from the figures, these methods rather strikingly correctly predict future abnormality for 86% of grains that become abnormal within 20% of their lifetime before abnormality. In short, PAL and PAGL are able to correctly predict that a grain will become abnormal at relatively early stages in its evolution.

The number of abnormal grains predicted at the earliest point in their lifespan (fpred), is shown with blue bars. The bars are positioned on the pre-abnormality interval of all grains, flife. The horizontal axis is essentially a timeline of grain lifespan before abnormality, from 0 (simulation start) to when the grain becomes abnormal, 100. Relative to this timeline, the earliest prediction of abnormality for more than 80% of grains occurs before 20% of the pre-abnormality interval has passed, in all scenarios. This is apparent in the cumulative fraction of predicted abnormal grains, shown with a red line (fcum). These results are similar for both PAL (a–c), from left to right along the top row) and PAGL (d–f, from left to right along the bottom row), over all scenarios.

Quantifying feature importance

Given the ability to predict future abnormality, the trained models were examined to determine which dynamic features were most salient for prediction. To address this question, the Integrated Gradients (IG) method37 was employed to quantify the importance of every dynamic feature (see Methods section for details). Since PAL was trained independently on different chronological bins, one can determine which features are important at different times.

Figure 9 illustrates the computed time-dependent importance scores for the three scenarios. It was observed that modified normalized curvature, \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\), was an important feature for predicting future abnormality at all times during the simulation. On the other hand, minimum grain velocity, vmin, was important only after 50M MCS, suggesting that most boundaries associated with abnormal grains have high mobilities after this period. It is also evident that the number of grain neighbors, D, was of some importance at early times, while the grain neighbor volume, VN, was relatively unimportant over the entire simulation.

The results are averaged over all (a) unweighted, (b) additively-weighted, and (c) multiplicatively-weighted Voronoi scenarios. These importance scores are normalized across all three scenarios. The dynamic features are the relative grain volume (\({V}^{{\prime} }\)), the grain neighbor volume (VN), the number of grain neighbors (D), the modified normalized curvature (\({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\)), the integral grain velocity (v) and the maximum and minimum boundary velocities (vmax, vmin).

PAL was also independently trained on different asynchronous bins, enabling the use of the Integrated Gradients method to estimate the importance of the dynamic features at different time intervals in advance of future abnormality. Figure 10 summarizes the findings for each scenario. The modified normalized curvature, minimum velocity, number of neighbors, and integral velocity are all important for predicting future abnormality when abnormality occurs in 20M MCS or less. When considering grains that will become abnormal more than 20M MCS in the future, the importance scores of relative grain volume, integral velocity, and modified normalized curvature rapidly diminished, while the number of neighbors and minimum grain velocity remained important well past 50M MCS before abnormality.

The results are averaged over all (a) unweighted, (b) additively-weighted, and (c) multiplicatively-weighted Voronoi scenarios. The dynamic features are the relative grain volume (\({V}^{{\prime} }\)), the grain neighbor volume (VN), the number of grain neighbors (D), the modified normalized curvature (\({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\)), the integral grain velocity (v) and the maximum and minimum boundary velocities (vmax, vmin).

Connection with network analysis

It is natural to ask whether quantities developed for network analysis, which are sensitive to heterogeneity in graph structures, are effectively learned using PAGL. For example, since incipient abnormal grains tend to be surrounded by many normal neighbors, quantities that reflect this microstructural asymmetry may, in principle, be learned. Thus, candidate quantities that reflect abnormality in this context would include the degree difference, δ38, which highlights the difference between highly connected and nearby sparsely connected grains, and the local assortativity, \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\)39,40, a measure of the tendency for adjacent grains to exhibit similar amounts of connectivity.

Figure 11a shows the probability density function (pdf), \(P\left(\delta \right)\) for the degree distribution, for an ensemble of grains in a microstructure undergoing complexion transitions at both early (5 M MCS) and late times (40 M MCS). From this plot the presence of grains surrounded by a large number of neighbors is evident at 40M MCS by the extended tail in \(P\left(\delta \right)\), indicating that, since 5M MCS, some enlarged grains are adjacent to many small grains. A related effect is visible in the cumulative distribution of local assortativity, \({P}_{cum}\left({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\right)\), shown in Fig. 11b at 5M and at 40M MCS. The long negative tail for \({\alpha }^{{\prime} } < 0\) in the 40M MCS curve indicates a significant increase in disassortativity since 5M MCS, confirming the emergence of grains with large numbers of neighbors becoming adjacent to other grains with with very few.

a \(P\left(\delta \right)\) as a function of degree difference, δ, for a microstructure undergoing complexion transitions for times t = 5M MCS (green solid curve) and 40M MCS (violet dashed curve). The latter exhibits a long tail that is indicative of a microstructural asymmetry. b \({P}_{cum}\left({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\right)\) as a function of local assortativity, α′, for a microstructure undergoing complexion transitions for times t = 5M MCS (green solid curve) and 40M MCS) (violet dashed curve). c Var\(\left(\delta \right)\)/Var\(\left(\delta \right)\left(t=0\right)\) as a function of time, t, for a microstructure evolving without complexion transitions (violet dashed curve) and another evolving with such transitions (green solid curve). Note the pronounced peak in the latter curve.

From these considerations, it is sensible to identify certain moments of \(P\left(\delta \right)\), such as the variance (Var \(\left(\delta \right)\)) or the kurtosis (\(\kappa \left(\delta \right)\)), as useful indicators of a transition from normal to abnormal grain growth. For simplicity, we focus here on the variance of the distribution. Figure 11c shows the variance Var \(\left(\delta \right)\) relative to its initial value, Var \(\left(\delta \right)\left(t=0\right)\), as a function of time, t, for a microstructure evolving without complexion transitions and one evolving with complexion transitions. In the latter case, the variance shows a pronounced peak relative to that of the former case, indicating that a transition to AGG has occurred. Note that the decrease in the variance at late times occurs in the latter case as the system comprises many relatively large grains, and so the disparity in vertex degree decreases.

Finally, one can ask whether local assortativity and degree difference in particular are properties that are being learned as part of our existing dynamic features. To test this proposition, local assortativity and degree difference were added as new features considered by PAL. Applying the aforementioned Integrated Gradients (IG) method, as illustrated in Fig. 12, it was found that they were not especially relevant for accurate prediction. Thus, one may infer that δ and \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\), or similar indicators of microstructural heterogeneity, are being learned as part of the existing dynamic features already.

The results are averaged over all (a) unweighted, (b) additively-weighted, and (c) multiplicatively-weighted Voronoi scenarios. Two additional network-based features are the degree difference (δ) colored in dark green and the local assortativity (\({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\)) colored in light green. The previous dynamic features colored in grey are the relative grain volume (\({V}^{{\prime} }\)), the grain neighbor volume (VN), the number of grain neighbors (D), the modified normalized curvature (\({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\)), the integral grain velocity (v) and the maximum and minimum boundary velocities (vmax, vmin).

Discussion

We have measured the performance of two novel techniques that are able to predict if a grain in a simulated polycrystal will later grow abnormally large. To evaluate their generality, PAL and PAGL were tested on three distinct material scenarios, each represented by 50 independently generated 3D microstructures. Across all three scenarios, we observed that an average of 86% of the grains that eventually become abnormal could be predicted as such within the first 20% of their lifetime before abnormality. This advanced prediction was possible using data from up to to 65 M MCS before abnormality occurs, where sensitivity scores were above 0.81. Given these findings, and the fact that similar prediction performances were observed on all three scenarios, it is clear that it is possible to predict future abnormality in simulated grains can be predicted.

In making these predictions, one important question was whether future abnormality was a property that could be better learned from dynamic features that evolve in time with a coarsening microstructure, or, alternatively, from features evolving with a grain’s individual progress towards abnormality. When testing the former case, when PAL and PAGL were trained on chronological bins, they exhibited widely variable sensitivity in predicting future abnormality. For the latter case, using asynchronous bins, PAL and PAGL maintained sensitivity scores consistently above 0.83. This result suggests that incipient abnormal grains pass through recognizable stages as they advance towards abnormality, even if contemporaneous grains are at different stages. This independence might be enabled by a neighborhood of normal grains acting as a buffer.

An integrated gradients analysis of PAL on asynchronous bins indicated that modified normalized curvature, minimum velocity, number of neighbors, and integral velocity are all very important for predicting future abnormality when abnormality occurs in 20M MCS or less, but they diminish in importance when abnormality will occur farther in the future. On the other hand, a large number of neighbors and a high minimum grain velocity were continuously important long in advance of abnormality. These observations further support the idea that an incipient abnormal grain maintains a buffer of normal grains over parts of its lifespan.

Incorporating topological information yielded additional insights. For example, when trained on chronological bins, PAGL, which was trained with topological data, exhibited higher sensitivity and precision scores somewhat earlier than PAL, which lacked topological data. On asynchronous bins, the sensitivity and precision scores of PAL and PAGL were similar. These findings suggest that the topological data supports higher sensitivity and precision. In contrast, as asynchronous bins are populated with grains that may occur at different times in a simulation, the contribution of contemporized topological data is not readily apparent. These findings add nuance to the general idea that topological data about the organization of grains would strictly benefit the performance of any classifier, given the relevance of grain adjacency to the spatial organization of the microstructure. Thus, it appears that topological trends in the neighborhoods of incipient abnormal grains are tied not only to the future abnormality of the grains but also to the macroscopic state of the microstructure. Finally, an extended importance analysis of feature importance using PAGL suggested that measures of network homophily, such as local assortativity and degree difference, may be learned as part of model training.

The features comprising the feature vectors identified in the Representations section were selected based on physical considerations. For example, traditional descriptions of grain growth have asserted that over-damped grain velocity, as embodied in v, is proportional to integrated grain curvature, as represented here by \({M}_{s}^{{\prime} }\), although recent work suggests that this relationship may not strictly hold in practice. Moreover, the velocity features vmax and vmin reflect the growth advantage assumed to be associated with high-mobility boundaries that delimit abnormal grains.

While one cannot use the results outlined above to say unambiguously how abnormal growth occurs, one can make some general inferences regarding the physics of likely AGG scenarios. One picture that emerges is that of relatively independent, incipient abnormal grains surrounded in a sea of “normal” grains. These future abnormal grains acquire, in this case by random, cooperative complexion transitions that alter the grain-boundary mobility on some high-curvature boundaries, high-velocity boundaries that endow them with a growth advantage. Over time, this growth advantage leads to large, abnormal grains surrounded by many smaller normal grains and the eventual impingement of the abnormal grains.

From these considerations, it is of interest to determine whether other mechanisms leading to AGG, including the presence of impurities and grain-boundary energy disparities, might also be important features. More specifically, the cooperative nature of the complexion transitions employed in our studies seems to be a critical factor in the nucleation and subsequent growth of abnormal grains. It is unclear whether, for example, the presence of randomly-distributed impurities will be as effective in promoting AGG given their somewhat localized impact on grain growth. The role of these other mechanisms in promoting AGG will be the subject of future studies.

Given the success of deep learning models in predicting AGG as highlighted above, it is also of interest to determine whether such models may be used to anticipate other rare events. In the materials science realm, for example, activated processes such as the nucleation of a stable phase in a metastable background may occur relatively infrequently, especially at small undercoolings, while, in the biomedical realm, the occurrence of a virulent pathogen may require multiple mutations41. Some progress has been made in rare event prediction recently by training neural networks on short-time trajectory data on simplified stochastic dynamical systems, such as sudden stratospheric warming42, and by combining importance sampling strategies with deep neural networks to enhance rare event sampling in atomic-level simulations43. More generally, other recent work focusing on the estimation of rare event probabilities associated with the properties random geometric graphs that model processes of importance in, for example, wireless network technology has shown that one can obtain these probabilities via Monte Carlo simulation44. We have demonstrated here that one can use a dynamic graph-based representation to identify precursors of random events that enable early prediction. Our analysis of AGG is based on training networks using long-time trajectories of coarse-grained systems having a large number of degrees of freedom and assessing the relative importance of key features. As such, we believe that it can serve as a template for forecasting rare events in other contexts that are amenable to a network description.

Methods

Monte Carlo simulations of the Potts model

Monte Carlo simulations of a 3D modified Q-state Potts model were used to generate the microstructures analyzed here. In this model, voxels represent a spatially coarse-grained part of a system comprising a very large number of particles. Interfacial phase (complexion) transitions26 occur as correlated stochastic events that increase grain-boundary mobilities and thereby promote abnormal grain growth (AGG) in some circumstances21,25. The corresponding Hamiltonian for this system is given by

where i and j label the voxels, Si is the spin value for voxel i, J > 0 is a constant energy parameter, the angle brackets denote nearest-neighbor voxel pairs and δ is the Kronecker delta. Unlike neighboring grains are therefore associated with an energy penalty. The time evolution of this model follows a modified Metropolis rule20,25 at a fixed, artificial inverse temperature β. The rate of complexion transitions is dictated by an effective temperature relative to the activation energy for this transition21. In our simulations, the (inverse) temperature, β, is set to 0.5, and the mobility is set to 0.01 for “slow" boundaries and 1.0 for “fast" boundaries. Finally, as is customary, time is measured in Monte Carlo steps (MCS). During one MCS, each voxel attempts to flip once on average.

The simulations were initialized with either unweighted, additively-weighted or multiplicatively-weighted Voronoi tessellations on an underlying lattice with corresponding distance functions given by Eq. (1). In the unweighted case, all generators i had a multiplicative weight wi1 = 1 and an additive weight wi2 = 0. In the additively-weighted case, all generators i had a multiplicative weight wi1 = 1 and an additive weight of 1 or 2, selected randomly. Finally, in the multiplicatively-weighted case, all generators had an additive weight wi2 = 0 and a multiplicative weight of 1 or 2, selected randomly, to create curved boundaries. Moreover, in creating these tessellations, it is sometimes necessary to reject generators and re-classify small grains (e.g., in cases where two generators are assigned to the same voxel and when grains comprise less than 5 voxels). Since initial microstructures were randomly generated, they occasionally exhibited abnormally large grains by random chance. When this occurred, the microstructure was discarded and replacement was generated, guaranteeing that any abnormal grains observed in our simulations were created via grain growth and not randomized initial conditions. The numbers and values of weights used for additively-weighted and multiplicatively-weighted Voronoi tesselations were selected to maximize simplicity and reproducibility in experimental design while maintaining visual similarity to polycrystals.

Computing features from 3D Monte Carlo Potts simulations

Grains were analyzed voxel by voxel at various time steps to determine changes in volume, number of neighbors and grain boundary areas. In particular, grain volume was calculated by counting all voxels with the same grain identity and grain boundary curvature was measured using the “Innie/Outie method”31 of Patterson in which the voxelated mean curvature of a single grain boundary between grains a and b is calculated as

where O and I are the number of “outies” and “innies”, respectively. A negative mean curvature indicates that a grain boundary has a convex morphology relative to the grain center, thus leading to grain growth assuming curvature-driven grain boundary migration45. The associated integral mean curvature of a grain containing j grain boundaries is then

Finally, the grain boundary “velocity” is calculated in terms of the volume of voxels transitioning from a to b, Va→b, (or vice versa, Vb→a) in a time interval Δt as

Thus, the velocity is given in units of voxels/MCS.

Since an abnormal grain tends to abut other normal grains with dissimilar degrees in the abnormal grain growth, the graph assortativity is calculated to capture this tendency and quantify similarities or differences between neighboring vertices. The graph assortativity is then decomposed into local components following the definition proposed by Piraveenan et al.39 to characterize assortativity at the node level. The local assortativity of grain v reflecting the heterogeneity in neighboring degrees is defined as

where j is the excess degree of grain v, \({\bar{k}}_{v}\) denotes the average excess degrees of the neighbors of grain v, μq denotes the average excess degree in the graph, M is the number of edges in the graph, and σq denotes the standard deviation of the excess degree distribution in the graph. Note that the excess degree is formally equal to the degree minus 1. We further follow the standard proposed by Farzam et al.38 to define the degree difference, δ, between neighboring vertices forming an edge as

where deg(v) is the degree of v, N(v) is the set of neighbors of v, and u is one of the nearest neighbors. From this perspective, one can regard the degree difference as the basic unit of assortativity characterizing structural heterogeneity in the mixing patterns of graphs.

The global average excess degree μq in Equation (9) proposed by Piraveenan et al.39 is crucial in determining whether a node is assortative or disassortative, indicating that a node would be simply considered assortative if its average neighboring excess degree is larger than the global one; otherwise, it is disassortative. To address this limitation, we choose an alternative method proposed by Thedchanamoorthy et al.46 to calculate the local assortativity without pivoting on μq. In our experiment, the local assortativity is defined as

where r is the graph assortativity, N is the number of node, and \(\bar{\delta }\) is the scaled degree difference divided by the sum. The sum of the local assortativity can match the graph assortativity.

Model training and evaluation protocols

We use chronological binning and asynchronous binning to construct training and testing sets for PAL and PAGL. In chronological binning, since grains that become abnormal are rare, there is a risk of constructing an imbalanced data set. An average of 66 grains become abnormal for every 5181 persistently normal grains in each simulation. This balance does not change for chronological bins formed from features derived from different intervals in the simulation, because we are predicting between grains that become abnormal and those that never do. By performing 50 simulations of each scenario, we generated an average of 3322 grains that eventually became abnormal in three scenarios, giving us a sizable dataset of abnormal grains. In asynchronous binning, when an incipient abnormal grain is added to a bin, a normal grain of the same age in simulation time is added as well. Since there are hundreds of normal grains for every abnormal grain, this pairing can be done without duplication, and it leads to datasets that are perfectly half normal and half incipient abnormal.

We used Pytorch47 to build our proposed methods and trained them on a Nvidia Tesla A100 GPU with 40GB memory. In the LSTM model, we set the number of layers to 2 and the hidden size dh to 64. In the GCRN model, we chose three GCN layers to learn the 2-hop neighboring information, set the hidden size dl of GCN to 128, and kept the same setting of the recurrent part as the LSTM model. These two models were followed by an MLP classifier with three fully-connected layers, a dropout layer with a 0.5 dropout rate, and a sigmoid function. In the training, all the learnable weights in LSTM and GCRN models were updated through the Adam optimizer. We set the learning rate to 0.001, batch size to 32, and the number of epochs to 500. Meanwhile, we used the binary cross entropy as the loss function for classification.

To examine the classification performance and generalizability, we built multiple independent simulations and performed the 5-fold cross validation to split the training, validation, and testing data based on the simulations instead of grains for each initial scenario. In the evaluation, we calculated the number of abnormal grains (P) and normal grains (N) in the data and, from the confusion matrix, summarized the true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) cases in the binary classification performance. The average \(\,\text{accuracy}=\frac{\text{TP+TN}}{\text{P+N}\,}\), \(\,\text{sensitivity}=\frac{\text{TP}}{\text{TP+FN}\,}\), and \(\,\text{precision}=\frac{\text{TP}}{\text{TP+FP}\,}\) scores under the 5-fold cross validation were reported.

Feature importance calculation

We use the Integrated Gradients (IG) method37 to evaluate the feature importance over the time steps and dynamic graphs for predicting abnormal grains. We defined a baseline feature matrix \(\bar{X}\) required by the calculation of IG. Specifically, to find the kth feature importance, the value of kth feature in baseline \(\bar{X}\) is set to zero while other features are kept the same as the input feature X. This setting quantifies the individual contribution of the kth feature to the abnormal prediction.

Mathematically, the IG of kth feature in ith grain over tth time step is determined by aggregating the gradients along the straight line that connects the baseline to the actual feature,

where f is the trained model and m denotes the total number of steps in the integral Riemann approximation. Note that the result of IG for each feature in each grain is a scalar value and the IG matrix keeps the same dimension as the input feature X. We summarize the feature’s importance by averaging the IG matrix along all grains, that is \(\frac{1}{N}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{N}IG({X}_{ti}^{k})\) where N is the number of grains. A large positive/negative IG value suggests that the prediction output will increase/decrease significantly when the value of the feature increases from the baseline. Consequently, a larger absolute IG value of the specific feature indicates a higher importance.

Data availability

The authors will make available, upon request, the data used in the applications described in this work. It is understood that the data provided will not be for commercial use.

Code availability

The authors will make available, upon request, the code used in the applications described in this work. It is understood that the code will not be for commercial use.

References

Hillert, M. On the theory of normal and abnormal grain growth. Acta Metall. 13, 227–238 (1965).

Rios, P. Abnormal grain growth development from uniform grain size distributions. Acta Mater. 45, 1785–1789 (1997).

Handwerker, C. A., Morris, P. A. & Coble, R. L. Effects of chemical inhomogeneities on grain growth and microstructure in Al2O3. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 72, 130–136 (1989).

Cantwell, P. R. et al. Grain boundary complexions. Acta Mater. 62, 1–48 (2014).

Rickman, J. M., Chan, H. M., Harmer, M. P. & Luo, J. Grain boundary layering transitions in a model bicrystal. Surf. Sci. 618, 88–93 (2013).

Bedu-Amissah, K., Rickman, J. M. & Chan, H. M. Grain-boundary diffusion of Cr in pure and Y-doped alumina. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 90, 1551–1555 (2007).

Hanaor, D. A., Xu, W., Ferry, M. & Sorrell, C. C. Abnormal grain growth of rutile TiO2 induced by ZrSiO4. J. Cryst. Growth 359, 83–91 (2012).

Padture, N. P. & Lawn, B. R. Toughness properties of a silicon carbide with an in-situ induced heterogeneous grain structure. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 77, 2518–2522 (1994).

May, J. & Turnbull, D. Secondary recrystallization in silicon iron. Trans. Metall. Soc. AIME 212, 769–781 (1958).

Holm, E. A., Hoffmann, T. D., Rollett, A. D. & Roberts, C. G. Particle-assisted abnormal grain growth. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 89, 012005 (2015).

Barmak, K., Rickman, J. M. & Patrick, M. J. Advances in experimental studies of grain growth in thin films. JOM 1–15 (2024).

Patrick, M. J. et al. Automated grain boundary detection for bright-field transmission electron microscopy images via U-Net. Microsc. Microanal. 29, 1968–1979 (2023).

Bae, I.-J. & Baik, S. Abnormal grain growth of alumina. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 80, 1149–1156 (1997).

Omori, T. et al. Abnormal grain growth induced by cyclic heat treatment. Science 341, 1500–1502 (2013).

Lawrence, A., Rickman, J., Harmer, M. & Rollett, A. Parsing abnormal grain growth. Acta Mater. 103, 681–687 (2016).

Moelans, N. New phase-field model for polycrystalline systems with anisotropic grain boundary properties. Mater. Des. 217, 110592 (2022).

Krill III, C. E. & Chen, L.-Q. Computer simulation of 3-D grain growth using a phase-field model. Acta Mater. 50, 3057–3073 (2002).

Raghavan, S. & Sahay, S. S. Modeling the grain growth kinetics by cellular automaton. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 445-446, 203–209 (2007).

Fausty, J., Bozzolo, N., Muñoz, D. P. & Bernacki, M. A novel level-set finite element formulation for grain growth with heterogeneous grain boundary energies. Mater. Des. 160, 578–590 (2018).

Anderson, M., Srolovitz, D., Grest, G. & Sahni, P. Computer simulation of grain growth - I. Kinetics. Acta Metall. 32, 783–791 (1984).

Marvel, C. et al. Relating the kinetics of grain-boundary complexion transitions and abnormal grain growth: a monte carlo time-temperature-transformation approach. Acta Mater. 239, 118262 (2022).

Yan, W. et al. A novel physics-regularized interpretable machine learning model for grain growth. Mater. Des. 222, 111032 (2022).

Melville, J. et al. Anisotropic physics-regularized interpretable machine learning of microstructure evolution. Computational Mater. Sci. 238, 112941 (2024).

Yang, K. et al. Self-supervised learning and prediction of microstructure evolution with convolutional recurrent neural networks. Patterns 2, 100243 (2021).

Frazier, W. E., Rohrer, G. S. & Rollett, A. D. Abnormal grain growth in the potts model incorporating grain boundary complexion transitions that increase the mobility of individual boundaries. Acta Mater. 96, 390–398 (2015).

Cantwell, P. R. et al. Grain boundary complexion transitions. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 50, 465–492 (2020).

Okabe, A., Boots, B., Sugihara, K. & Chiu, S.Spatial Tessellations: Concepts and Applications of Voronoi Diagrams (Wiley, New York, 2000).

Rickman, J., Tong, W. & Barmak, K. Impact of heterogeneous boundary nucleation on transformation kinetics and microstructure. Acta Mater. 45, 1153–1166 (1997).

Avrami, M. Kinetics of phase change. I. General theory. J. Chem. Phys. 7, 1103–1112 (1939).

Cardona, C. G., Tikare, V., Patterson, B. R. & Olevsky, E. On sintering stress in complex powder compacts. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 95, 2372–2382 (2012).

Patterson, B. et al. Integral mean curvature analysis of 3D grain growth: Linearity of dv/dt and grain volume. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 580, 012020 (2019).

Grest, G. S., Anderson, M. P., Srolovitz, D. J. & Rollett, A. D. Abnormal grain growth in three dimensions. Scr. Metall. 24, 661–665 (1990).

Srivastava, N., Mansimov, E. & Salakhudinov, R. Unsupervised learning of video representations using lstms. In Proc. 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning, 843–852 (2015).

Sutskever, I., Vinyals, O. & Le, Q. V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 27, 3104–3112 (2014).

Seo, Y., Defferrard, M., Vandergheynst, P. & Bresson, X. Structured sequence modeling with graph convolutional recurrent networks. In Proc. 25th International Conference on Neural Information Processing, 362–373 (Springer, 2018).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In Proc. 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (2017).

Sundararajan, M., Taly, A. & Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In Proc. 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, 3319–3328 (2017).

Farzam, A., Samal, A. & Jost, J. Degree difference: a simple measure to characterize structural heterogeneity in complex networks. Sci. Rep. 10, 21348 (2020).

Piraveenan, M., Prokopenko, M. & Zomaya, A. Y. Classifying complex networks using unbiased local assortativity. In ALIFE, 329–336 (2010).

Newman, M. Assortative mixing in networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 208701 (2002).

Sohail, M. S., Louie, R. H., McKay, M. R. & Barton, J. P. MPL resolves genetic linkage in fitness inference from complex evolutionary histories. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 472–479 (2021).

Strahan, J., Finkel, J., Dinner, A. R. & Weare, J. Predicting rare events using neural networks and short-trajectory data. J. Computational Phys. 488, 112152 (2023).

Hua, X., Ahmad, R., Blanchet, J. & Cai, W. Accelerated sampling of rare events using a neural network bias potential. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.06936 (2024).

Hirsch, C., Moka, S. B., Taimre, T. & Kroese, D. P. Rare events in random geometric graphs. Methodol. Comp. Appl. 24, 1367–1383 (2022).

Zhong, X., Kelly, M. N., Miller, H. M., Dillon, S. J. & Rohrer, G. S. Grain boundary curvatures in polycrystalline SrTiO3: Dependence on grain size, topology, and crystallography. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 102, 7003–7014 (2019).

Thedchanamoorthy, G., Piraveenan, M., Kasthuriratna, D. & Senanayake, U. Node assortativity in complex networks: An alternative approach. Procedia Computer Sci. 29, 2449–2461 (2014).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 32, 8024–8035 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) DMREF grant DMS-2118197 and the Army Research Office (ARO) grant W911NF-19-2-0093. M.P.H., J.S., C.J.M., and B.Y.C, also acknowledge the support of the Army Research Laboratory under Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-22-2-0032 titled Lightweight High Entropy Alloy Design (LHEAD) Project, as well as support from the Lehigh University Presidential Nano-Human Interfaces (NHI) Initiative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. performed the conceptualization, implemented the methodology, conducted the experiments, and edited the manuscript. B.Z. performed the conceptualization, implemented the methodology, edited the manuscipt, and built the software to visualize the simulations. J.S. edited the manuscript. M.P.H. and C.J.M. performed the conceptualization, provided the experimental simulations, and edited the manuscipt. J.R. analyzed the data and edited the manuscript. L.H. designed the methodology and edited the manuscipt. B.Y.C. performed the conceptualization, implemented the methodology, and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, H., Zalatan, B., Stanescu, J. et al. Learning to predict rare events: the case of abnormal grain growth. npj Comput Mater 11, 82 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01530-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01530-8