Abstract

The bulk photovoltaic (BPV) effect, which generates steady photocurrents and above-bandgap photovoltages in non-centrosymmetric materials when exposed to light, holds great potential for advancing optoelectronic and photovoltaic technologies. However, its influence on the reconfiguration of ferroelectric domain structure remains underexplored. In this study, we developed a phase-field model to understand the BPV effect in ferroelectric oxides. Our model reveals that variations in BPV currents across domains create opposing charges at domain walls, enhancing the electric field within domains to ~1000 kV/cm. The strong electric fields can reorient the ferroelectric polarization and enable ultrafast domain wall movements and nonvolatile domain switching on the picosecond scale. Applying anisotropic strain can further strengthen this effect, enabling more precise control of domain switching. Our findings advance the fundamental understanding of BPV effect in ferroelectrics, paving the ways for developing opto-ferroelectric memory technologies and high-efficiency photovoltaic applications via precise domain engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ferroelectric materials, known for their reversible spontaneous polarization under an external electric field, are foundational to a wide array of advanced technological applications1, including non-volatile high-density data storage2, piezoelectric transducers3,4, electro-optic devices5,6,7, and optoelectronics8,9,10,11. Their unique properties are intrinsically tied to their domain structures—regions of uniform polarization separated by domain walls. Effective manipulation of these domains is crucial for harnessing the full potential of ferroelectric technologies12. Additionally, tailoring the properties of domain walls enables the development of nanoscale domain-wall logic component13.

Optical control of ferroelectric domains has recently emerged as a transformative approach, offering a non-contact method that bypasses the limitations of traditional electrode-based techniques. Light influences ferroelectric materials through various mechanisms, including photoexcitation14,15,16,17,18, nonlinear optical effects19,20,21,22,23, and thermal effects24,25,26. While thermal effects, including thermal depolarization24 and strain25,26, can switch domains, their slow response times make them unsuitable for high-speed applications. Terahertz fields generated from ultrashort pulses can drive soft phonon modes coupled to polarization21,22,23, providing a faster alternative, though effective polarization switching with these fields has not yet been achieved experimentally19,20. In contrast, photoexcitation-induced phenomena, driven by rapid electronic processes, provide efficient control over ferroelectric domains. Upon above-bandgap illumination, ferroelectric materials undergo optical transitions17,18, generating electron-hole pairs that temporarily render the material metallic and destabilize its polarization. This charge redistribution stabilizes imprinted polarization states after the light is turned off27,28,29. Photon-induced charge imbalance at the surface can promote polarization switching, driven by different diffusion lengths of photogenerated electrons and holes30. The resulting photo-induced electric field can drive domain wall motion even on a nanosecond timescale31. Reports also indicate that optical illumination can facilitate the movement of charged domain walls32,33,34,35, a process still under investigation for its dependence on light polarization32.

The optical transitions which occur in non-centrosymmetric materials such as ferroelectrics hold great potential for ferroelectric domain engineering through the bulk photovoltaic (BPV) effect10,11,14,15,16, characterized by its strong sensitivity to light polarization. This effect generates polarization-dependent photocurrents and high open-circuit voltages, enabling precise domain manipulation at ultrafast timescales. Techniques such as tip-enhanced photovoltaic effects36 and the use of narrow bandgap ferroelectrics37 show promise in manipulating domain structures using the BPV effect. However, further studies are needed to fully understand this process. Theoretical investigations are essential for deepening our understanding of BPV characteristics and maximizing its potential in ferroelectric materials. The BPV effect in ferroelectrics is primarily driven by the shift current mechanism, which can be accurately predicted by first-principles calculations38,39 that focus on the microscopic origins of the effect. In contrast, existing macroscopic transport models primarily address current dynamics40 and impurity removal41 in ferroelectrics with uniform polarization, lacking detailed insights into the complex domain structures and their interactions. Therefore, there is a pressing need for the development of mesoscopic models that can bridge this gap, providing a comprehensive understanding of macroscopic BPV characteristics and the dynamic behaviors of domain configurations. Developing such mesoscale models will further advance our understanding and ability to manipulate ferroelectric materials for next-generation technologies.

In this study, we developed a dynamical phase-field model (DPFM) to investigate the influence of the bulk photovoltaic effect on ultrafast domain switching in ferroelectric thin films when exposed to light. Our model uniquely incorporates a carrier generation term in the current continuity equation to depict BPV-induced instantaneous charge carrier generation and separation. Our approach not only replicates the short-circuit current and open-circuit voltage characteristics of single-domain ferroelectrics, but also offers profound insights into domain-wall BPV effects in multi-domain systems, aligning with experimental data from ref. 42. It is revealed that opposite charge carriers are formed at adjacent domain walls, leading to the tilting of electric potential profiles under the influence of intense ultrashort laser pulses. Remarkably, the model predicts a light-induced transformation of domain configurations, resulting in a nonvolatile switching between neutral and charged domain walls on a picosecond timescale. Additionally, we demonstrate that tuning the relative width between alternating domains significantly enhances the efficiency of domain manipulation. This research establishes a foundation for ultrafast, nonvolatile polarization reversal and deterministic domain control, paving the way for the development of advanced optically driven ferroic-based devices.

Results

Model

To describe the BPV effect and the associated carrier dynamics in ferroelectrics under above-bandgap excitation, we employ the theory of shift current15,16 as the primary mechanism for optical transitions. Figure 1a conceptualizes the basic understanding of the shift current bulk photovoltaic effect. It arises from the asymmetric motion of photoexcited carriers, driven by differences in the spatial characters of conduction and valence bands. These spatial characters, reflecting the symmetry and distribution of the electronic wavefunctions within the unit cell (Bloch states), lead to directional anisotropy during the optical transition process, particularly in materials that lack inversion symmetry. Details of the shift current mechanism are derived from time-dependent perturbation theory43,44 and can be calculated by first-principles calculations (see refs. 38,39). Figure 1a schematically illustrates the conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) for (wide bandgap) ferroelectric semiconductors at spatial grid points from x0 to x4. When a ferroelectric semiconductor in the region between x1 and x3 (marked by an orange box) is illuminated, it experiences a transition process based on two mechanisms: one general to all semiconductors and the other specific to the non-centrosymmetric nature of ferroelectrics. For general semiconductors, an electron (represented by a blue solid circle) in the valence band absorbs a photon, transits to the conduction band, and leaves behind a hole (red empty circle) in the valence band. In addition, in ferroelectrics, the transition also involves an average displacement of coherent carriers during their lifetimes, known as a shift vector15,38,39. The resulting shift current of electrons and holes, represented by green dashed arrows in opposite directions in Fig. 1a, indicates photo-induced carrier separation during the transition process. The combined electron and hole shift currents contribute to the BPV current density (JBPV) flowing through the ferroelectric material. In bulk ferroelectrics, particularly at the spatial grid point x2, the material behaves as a steady current flow, with the number of electrons and holes remaining unchanged despite the BPV shift. This carrier generation process is similar to that in general semiconductors. However, near the outer dark region, electrons/holes are created/annihilated at the left boundary, while holes/electrons are created/annihilated at the right boundary. This induces an additional carrier generation term due to the spatial inhomogeneity of the BPV current. Accordingly, the generation rate of electrons and holes (Gn and Gp) during the BPV transition can be formulated in Eqs. (1−2).

where Gph represents the generation rate of electron-hole pairs in a general semiconductor upon photoexcitation (see details in Methods). JBPV denotes the BPV current density flowing through a ferroelectric. The divergence terms in Eqs. (1−2) account for the generation rate of electrons and holes due to the spatial inhomogeneity of the JBPV, and their signs can be determined from Fig. 1a. It is noteworthy that the contributions of JBPV inhomogeneity to the electron and hole generations are absent in previous phenomenological models40,41.

a Schematics of the optical transition process accompanying a BPV current, driven by a shift current mechanism under above-band gap illumination (highlighted within the orange box). The rate of electron-hole pair generation (illustrated by blue solid circles and red empty circles, respectively) in the bulk region follows a photoexcitation process common to all semiconductors, and accounts for an additional contribution arising from the spatial inhomogeneity of the BPV current observed at the boundary of the illuminated region. The dashed empty circles represent the annihilation of electron or hole. b Schematics of dynamical phase-field model in ferroelectrics integrating BPV effect, demonstrating the coupled dynamics of the structural domains and charge carrier generation via the shift current mechanism. The local ferroelectric orientation and the incident light polarization both affect the separation of carriers and the voltage drop across the ferroelectric domain, which may further influence the initial domain structure.

The shift current is a zero-frequency component of the second-order nonlinear optical response that occurs in non-centrosymmetric materials, characterized by its quadratic dependence on the oscillating electric field (Eph) of the incident light44,45. The BPV current density (JBPV) due to shift current is given by Eq. (3).

where σijk is a third-rank shift current tensor that depends on both the material properties and the wavelength of the incident light. This tensor produces a nonzero shift current exclusively in non-centrosymmetric crystals. Its components can be determined experimentally42,46,47,48 through light polarization-dependent photocurrent measurements relative to the principal axis of crystallographic anisotropy or calculated numerically using first-principles methods38,39. To compare with experimental measurements42, we rewrite Eq. (3) in terms of light intensity Iph using the relation Iph = cε0|Eph | 2/2 for an electromagnetic wave, where c and ε0 are the speed of light in a vacuum and the vacuum permittivity, respectively.

in which βijk and \({\hat{e}}_{\text{i}}\) are the BPV tensor and the unit vector of electromagnetic field, respectively.

Thus far, we have introduced the mechanism in which carriers are excited under above-bandgap illumination through the shift current BPV effect. It is crucial to examine how these excited carriers and the associated BPV phenomena influence the ferroelectric domain structure. To explore this, we employ a dynamical phase-field model (DPFM)18,31,49 proposed by Yang et al. Unlike traditional ferroelectric phase-field models that consider quasi-static structural behavior with a fixed free carrier distribution, this dynamic model includes the evolution of free charge carriers and incorporates inertial and damping terms to account for transient behaviors in both polarization and displacement equations. Thus, integrating BPV carrier generation into the dynamical phase-field model (BPV-DPFM) enables us to study the ultrafast dynamics and the interplay of multiple degrees of freedom within ferroelectrics in response to optical stimuli. Figure 1b shows the governing equations in the BPV-DPFM model. The variables to be solved include the ferroelectric polarization P, the mechanical displacement u, the electron and hole concentrations n and p, and the electric potential V. The evolutions of the system’s structural dynamics, including P and u, are governed by the polarization dynamics equation and the elastodynamics equation18,31,49. These two equations are coupled through the spontaneous strain \({\varepsilon }_{\text{ij}}^{0}\) and the elastic energy Felastic. The drift-diffusion-Poisson equation, which couples the current continuity equation and the electrostatics incorporating the remanent polarization, is utilized to investigate the charge carrier dynamics and the evolution of electric potential. It should be noted that in this manuscript, we approximate the electromagnetic effect as quasi-static. While this approach simplifies the analysis, it inherently overlooks phenomena such as the self-induction of BPV currents. A brief discussion of the potential implications of this approximation is provided in the Supplementary Information. The structural dynamics and the drift-diffusion-Poisson equation are coupled through the electrostatic energy (Felec) and the polarization within the domain structure. Particularly, the orientation of local polarization influences the formulation of BPV current density and the associated carrier generation within the laboratory coordinate system, governed by a transformed BPV tensor (\({\beta}_{\rm{ijk}}^{\prime\prime}\)). The upper right panel of Fig. 1b illustrates the transformation of a (001)-oriented tetragonal ferroelectric crystal, involving two rotations defined by the Euler angles θ and φ. These transformations ensure that the BPV tensor accurately reflects the symmetry properties and local polarization orientation in the laboratory frame. Detailed formulations of the coupled equations and procedures for rotating the third-rank BPV tensor are provided in the Methods section.

Multi-domain ferroelectrics with domain wall (DW) BPV effect

To validate our proposed model, we first performed simulations to accurately replicate the BPV behavior observed in conventional macroscopic experiments42,48. We began by considering a BaTiO3 (BTO) single crystal consisting of a single tetragonal domain with homogeneous semiconducting properties under uniform light illumination. The results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The influence of the contact potential at the metal-semiconductor interface was excluded from the exploration of intrinsic BPV characteristics. As expected, this setup consistently yields a zero diffusion current within the simulation domain. When the metal contacts were shorted, the drift current was also zero. The short-circuit current integrated at the electrodes was solely attributed to the BPV current, which is directly proportional to the light intensity and depends on the light polarization angle, as described by Eq. (4). The open-circuit voltage was determined by driving a drift current that completely counteracted the BPV current. Our simulation results indicated that at low light intensities, the voltage required to achieve a net zero current through the electrodes was primarily governed by the intrinsic dark conductivity. As the light intensity increased, photoconductivity became dominant, causing the voltage to reach a saturation value. This saturation voltage was determined by the ratio of the BPV tensor coefficients to the optical transition efficiency. Detailed simulation results are provided in Supplementary Note 1 and Fig. 1.

Next, we investigate the behavior of multi-domain BTO crystals. Experimental observations suggested that the domain wall bulk photovoltaic (DW-BPV) effect could significantly affect the overall BPV behavior compared to the contribution from bulk domain (bulk-BPV effect). This phenomenon cannot be explained by conventional group theory predictions. Therefore, we employ phase-field modeling to explore the BPV behavior at domain wall and to provide insight into the underlying mechanisms.

Figure 2a illustrates the experimental setup used for BPV measurements and our simulation scheme. The configuration includes a multi-domain BTO crystal consisting of alternating a+ domains (with P//+y) and c+ domains (with P//+z), as highlighted in green and red, respectively. The violet light (405 nm) propagates along the negative x-axis, positioning the electromagnetic field (Eph) within the y-z plane and allowing it to be rotated relative to the x-axis. We define the angle θph as zero degrees when Eph is parallel to the z-axis. Electrodes are attached to the (011) surface, establishing connections to ground and bias (V0), in agreement with previous experiments42. The BPV current density JBPV in a+/c+ domain structure exhibits selective tensor activations as defined by Eq. (4). When Eph aligns along z-axis, β33 predominates in c+ domains and β31 in a+ domains. Conversely, Eph alignment along y-axis results in β31 activation in c+ domains and β33 in a+ domains. Both configurations contribute to the current flowing through the electrodes. However, previous experimental results indicated that the contribution from β15 is insignificant42, and the current cannot be measured in this geometry. Therefore, it is ignored in this study. Here, we employ the matrix notation for the BPV tensor βijk in tetragonal crystals, which includes only β31, β33 and β15. Detailed transformation procedures are provided in the Methods section. In our simulation, we first stabilize a+/c+ domain structure of BTO under short-circuit conditions without light illumination. Once the domain structure is in equilibrium, we proceed to study its equilibrium BPV characteristics by solving the drift-diffusion-Poisson equations for n, p, and V. First, we do not allow the domain structure to evolve, and use the relaxation phase-field model (BPV-PFM) to study the stationary BPV effect. Ohmic contact boundary conditions are applied to the electrodes to determine short-circuit current density (JSC) as a function of θph and Iph (see Methods for details). Given that the simulation is periodic along the [0\(\bar{1}\)1] direction, we reduce the simulation geometry and visualize the results in the plane spanned by [011] and [0\(\bar{1}\)1], as shown in the lower panel in Fig. 2a. We used two parameters to define the multi-domain structure: the number of domain walls (NDWs) and the domain wall spacing (dDWs). For NDWs = 2 and dDWs = 30 nm, the simulation size is 60 nm.

a Simulation setup to emulate the experimental BPV measurement. The light polarization Eph, local ferroelectric polarization P, and BPV tensor β are defined with respect to the xyz axes. Voltage (V0) is applied on the bottom electrode while the top electrode is grounded. The lower panel illustrates an alternating a+/c+ domain with a number of domain walls (NDWs) of 2, a domain wall spacing (dDWs) of 30 nm, and a simulation size of 60 nm. The simulation geometry was rotated 45 degrees along the x-axis for easy representation. The size of the domain wall is ~1 nm. b The short-circuit current density (JSC) as a function of light polarization angle (θph) with fixed light intensity Iph = 5.6 W/cm2, BPV tensor component β31 = − 93 nA/W, β33 = − 55 nA/W for different NDWs (2–16) and at a fixed simulation size of 60 nm. Results for a single a+ domain, a single c+ domain, and their average (black dashed line) are also included for comparison. c Schematics of a continuous transition of polarization along the [011] direction across the 90-degree domain wall separating a+ and c+ domains. d Simulated JSC as a function of light polarization angle (θph) with fixed light intensity Iph = 5.6 W/cm2 for an alternating a+/c+ domain, with a volume ratio of domain walls to bulk domains equals to 1:300. Green curve corresponds to the case of a constant BPV tensor (βijk) with values of β31 = − 93 nA/W and β33 = − 55 nA/W, while the red curve corresponds to the case where the BPV tensor is modified at the domain walls with the values of β31 = + 7300 nA/W and β33 = + 13870 nA/W. The reference experimental data (blue dots) are sourced from Noguchi, Y. et al., J. Appl. Phys. 129, 084101 (2021).

Figure 2b shows the simulation results of the polarization angle dependence of equilibrium JSC in multi-domain BTO, using our BPV-PFM model with a simulation size of 60 nm. The NDWs varies from 2, 4, 8, to 16. For comparison, results for single a+ and c+ domains are also included. It is seen that JSC values range between Iphβ31/\(\sqrt{2}\) and Iphβ33/\(\sqrt{2}\) due to the 45-degree rotation of the electrodes compared to the single domain simulation (see Supplementary Note 1 and Fig. 1a). Based on the theoretical predictions for bulk-BPV effect, the overall JSC for BTO of alternating a/c domain structure should be the volume fraction-weighted average of JSC from each domain. This average is represented by the angular-independent dashed line (black) in Fig. 2b. However, our simulation results reveal an angular dependence of JSC, exhibiting a 45-degree phase shift compared to the single-domain case and a negative offset of JSC relative to the weighted average (the black dashed line). This effect is further enhanced with increasing NDWs, implying the DW-BPV effect. It is further revealed that this unexpected JSC is possibly due to the polarization alignment along the [011] direction at the domain walls. This alignment occurs because of the diffuse interface nature of the phase-field method, in which the polarizations rotate continuously from [010] direction to [001] direction across the domain walls, as shown in Fig. 2c. Notably, this structural transition behavior is consistent with atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) results50,51, suggesting that lattice distortions at the domain walls could be a potential origin for the DW-BPV effect.

Compared to the experimental observations42 by Noguchi et al., our BPV-PFM model produces a similar phase shift behavior in angular dependence of JSC. However, an opposite offset in JSC is obtained. After ruling out other potential factors, such as the impact of the built-in electric field in a multi-domain ferroelectrics (refer to Supplementary Fig. 2), we believe that the BPV tensor at the domain walls may deviate from that in the bulk domains42. To incorporate this effect, an activation function g related to the local gradient energy (fgrad) is defined to track the positions of domain walls:

where \({f}_{\text{grad}}^{\,\max }\) represents the maximum fgrad within the simulation domain, occurring at the domain wall. Accordingly, g is equal to one in bulk domains and zero at domain walls. Then we define,

In this manner, the BPV tensor component βijk becomes a function of the local gradient energy, which varies across different spatial locations and over time. Figure 2d shows the angular dependence of equilibrium JSC in multi-domain BTO, simulated by using a constant βijk (green curve) and a gradient energy-dependent βijk(fgrad) (red curve), compared with the reference data (blue dots)42. Here we used a simulation size of 600 nm, NDWs = 2, and a domain wall width of 1 nm. These parameters were selected to match the experimental results42. It is worth highlighting that we successfully reproduced the experimental results of DW-BPV effect by adjusting the βijk tensor at domain walls. This modification involves change of the sign of the tensor and enhancement of its magnitude by two orders of magnitude compared to that in the bulk domain. The optimal value for the BPV tensor is \({\beta }_{31}^{\text{bulk}}\) = −93 nA/W, \({\beta }_{33}^{\text{bulk}}\) = −55 nA/W, \({\beta }_{31}^{\text{DW}}\) = +7300 nA/W, and \({\beta }_{33}^{\text{DW}}\) = +13870 nA/W, respectively. Thus, our BPV-PFM model effectively integrates the presence of BPV current under illumination. This model enables real-time evaluation of the BPV current by transforming the BPV tensor based on the local polarization orientation in response to any arbitrary electromagnetic field. By incorporating the effect of polarization rotations across the domain walls, our model sheds light on the domain wall bulk photovoltaic effect in multi-domain ferroelectrics. Moreover, the anomalous enhancement of the BPV tensor at domain walls, as revealed by our BPV-PFM model, unveils intriguing physics at these interfaces, offering valuable insights for related studies.

Impacts of BPV current inhomogeneity across domain walls

We now utilize our BPV-PFM model to study the potential of optical modulation of ferroelectric domains via the BPV effect. We realize that the large open-circuit voltage (VOC) exceeding the bandgap is inefficient in modulating the ferroelectric domains. This inefficiency is due to several factors. First, the open-circuit electric field (EOC) cannot be further enhanced by increasing light power once it reaches its saturation, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1d. Second, the maximum EOC that can be achieved is typically in the range of ~102 kV/cm for BTO single crystal52, which is significantly lower than its coercive field. Supplementary Fig. 3 further corroborates this argument, demonstrating that the application of VOC results in negligible modulation in alternating a/c domains. Consequently, our subsequent investigations will focus on the influence of the short-circuit current (JSC). Unlike VOC, JSC increases linearly with Iph based on Eq. (4) without encountering limitations, which offers precise current generation capabilities before sample damage occurs. To investigate the influence of JBPV with a realistic modulation strength, we outline the maximum operational optical intensity for different optical methods and purposes. In conventional macroscopic BPV measurements, uniform illumination via a continuous-wave (CW) laser is adopted to ensure complete coverage across the current collection path, which can typically achieve a laser intensity of ~10 W/cm2. A focal optical lens can be used to further boost Iph by six orders of magnitude if needed. Additionally, optical intensities up to ~1011 W/cm2 with minimal thermal effects can be achieved using femtosecond (fs) pulsed lasers, which are commonly used as optical pumps in ultrafast dynamic experiments. Furthermore, laser ablation utilizing ultrashort laser pulses at intensities greater than 1013 W/cm2 is a common practice in industry. In Supplementary Fig. 4, we realized that using an Iph by CW laser is insufficient to modulate ferroelectric domains based on our BPV-PFM model. This suggests that the BPV effect may not be the main driving force for the experimental observations of reversible optical control in BTO bulk crystals via low-intensity laser illumination32,33.

The influence of JSC becomes prominent in the a/c domain BTO when Iph exceeds 1012 W/cm2, which is typically achievable through ultrafast pulsed laser illumination, as shown in Fig. 3a–f. To delve deeper into the scenario, we first analyzed the general photoexcitation characteristics, excluding the BPV effect. In Fig. 3a, one dimension (1D) concentration profiles of electrons (blue) and holes (red) along the simulation geometry at quasi-equilibrium are presented (see Methods). The background concentration reaches ~1019 cm−3, a level considered high for above-bandgap illumination due to its exceptionally high intensity (1012 W/cm2). A significant separation of electrons and holes occurs due to the presence of built-in electric fields in the multi-domain ferroelectrics, as illustrated by the dark electric potential profile (Vdark, gray line) in Fig. 3d. This separation screens the polarization bound charges at DWs, resulting in the smearing of electric potential profile, as indicated by the Vph (green) in Fig. 3d. The transient redistribution of carriers can perturb the ferroelectric domain structure, resulting in minor polarization oscillations (also refer to Supplementary Fig. 5). While these effects are generally modest in uncharged domain walls, their significance increases in specific configurations. For example, Yang and Chen have further demonstrated that, in the case of charged domain walls, these interactions are significantly amplified due to the high bound charge density at these walls18. This amplification induces transient structural oscillations and gives rise to pronounced effects, such as tensile strain of up to ~1%, persisting for approximately 100 ps, and domain wall displacements of up to 1 nm in configurations like 90° domains with tilted domain walls. Nevertheless, despite these transient effects, prior simulations suggest that the overall domain configuration remains largely stable following ultrafast excitation-induced polarization processes18.

a Charge carrier concentration C (blue line for electrons and red line for holes) generated from photoexcitation (Cph) with a light intensity of 1012 W/cm2 and a wavelength of 405 nm in multi-domain BaTiO3 (BTO). b Schematics of the accumulation of electrons and holes at 90-degree a/c domain walls due to the spatial inhomogeneity of the BPV current in BTO. The orange arrows represent the local BPV current direction in the bulk domain, while the pink arrows indicate the BPV current direction when considering the modification of the BPV tensor at the domain walls as mentioned in Fig. 2. Additional changes in carrier concentration (ΔC) due to the BPV effect (ΔCBPV−ph), and the comparison of electric potential profiles under dark state (Vdark), general photoexcitation (Vph), and the consideration of BPV effect for Case 1 (c, d) using a constant BPV tensor (VBPV, βijk), and for Case 2 (e, f) in which BPV tensor is modified at the domain walls (VBPV, βijk(fgrad)). The tilting of the electric potential profiles near domain walls is highlighted by the orange and purple arrows in (d, f),respectively. g Schematics of the accumulation of electrons and holes at domain walls due to the spatial inhomogeneity of the BPV current in a/c-domain PbTiO3 (PTO) under illumination with a light intensity of 1012 W/cm2 and a wavelength of 200 nm. The BPV tensor are β31 = +1.5 × 107 nA/W and β33 = − 3.7 × 107 nA/W. h Carrier concentration (C) due to the BPV effect (CBPV), and i the comparison of electric potential profiles under dark state (Vdark), general photoexcitation (Vph), and the consideration of BPV effect using a constant BPV tensor (VBPV, βijk). The arrows in (i) indicate the electric field within the a- and c-domains when the BPV effect is present, which further affects the ferroelectric domain structures. The electric potential is adjusted by subtracting the equilibrium potential to render clear visualization (see Methods).

We turn to consider the influence of JSC under two scenarios: one using a constant BPV tensor βijk and the other using a gradient energy dependent BPV tensor βijk(fgrad). Figure 3b schematically illustrates the JSC distribution for an alternating a+/c+ domain of BTO at a light polarization angle of 90 degrees. When the constant βijk tensor is employed, carrier generation due to current inhomogeneity can be understood through the bulk-BPV effect, depicted by the orange arrows indicating the direction and relative magnitude of the BPV current. Here, the impact of β31 dominates over that of β33, resulting in electron accumulation at the left DW and hole accumulation at the right DW. Relative changes in carrier concentration, which are calculated by the difference between the BPV and general photoexcitation contributions, are shown in Fig. 3c. The segregation of opposite charges at the neighboring domain walls causes a “tilting” of the electric potential profile (VBPV, βijk (orange) in Fig. 3d), i.e., the electric potential shifts downward at the left DW and upward at the right DW, creating opposing electric fields in adjacent domains. In contrast, when a gradient energy dependent BPV tensor βijk(fgrad) is utilized, the JSC direction is depicted by pink arrows at the DWs in Fig. 3b. Due to significantly enhanced BPV currents compared to that of the bulk domain, for both left and right DWs, electrons and holes accumulate on one side the DWs, and deplete on the other side (Fig. 3e), resulting in a pronounced modification of the electric potential labeled as VBPV, βijk(fgrad) (pink) in Fig. 3f. However, despite the enhanced BPV current at the DWs, the shape of the VBPV, βijk(fgrad) resembles Vdark, indicating further stabilization of the initial a/c domain structures. It is noteworthy that a “tilting” still occurs in the VBPV, βijk(fgrad), which is caused by the bulk-BPV effect and underscores the significant impact of the bulk-BPV effect on the electrostatic conditions in the alternating a/c domains of BTO.

Before delving into the structural dynamics induced by the BPV excitation by using the BPV-DPFM model, we made two critical decisions. First, we will employ a constant BPV tensor instead of a gradient energy-dependent one for the study. This is because local charge separation near domain walls itself is insufficient to induce domain structure switching based on our analysis, as depicted in Fig. 3f. Instead, the uneven current caused by the bulk-BPV effect plays a pivotal role in generating an electric field within the domain that can potentially switch ferroelectric polarization. Furthermore, while existing studies predominantly focused on multi-domain structures with 90-degree neutral DWs in bulk ferroelectric materials, we acknowledge that ferroelectrics of tetragonal symmetry may exhibit diverse polarization configurations, such as a+/c− domains separated by 90-degree charged DWs, and c+/c− domains separated by 180-degree neutral DWs. These variations, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6, underscore the need for further exploration of corresponding BPV effects, currently unattainable from experimental data. Depending on forthcoming experimental observations, adjustments may be needed in the methodology for generating the gradient energy dependent BPV tensor.

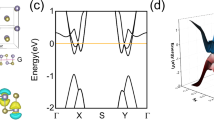

For the second decision, it became evident that leveraging the ultrafast structural response of PbTiO3 (PTO) to optical stimuli was essential18,23,53. While carrier relaxation times are prolonged in ferroelectric oxides, substantial simulation costs are incurred when the structural dynamics response is sluggish, particularly evident in the case of BTO ferroelectrics, where dynamics occur on the nanosecond timescale31,49. In contrast, recent experimental findings and numerical simulations suggested that PTO can interact with femtosecond optical excitation, exhibiting polarization and charge dynamics from picosecond to nanosecond timescales18,23,53. Consequently, in the following sections we will use PTO to exploit its rapid structural response to optical stimuli. Figure 3g displays the JSC distribution for an alternating a+/c+ domain in PTO at a light polarization angle of 0 degrees. We utilize a constant BPV tensor with values of β31 = +1.5 × 107 nA/W and β33 = − 3.7 × 107 nA/W, derived from the first-principles calculations of shift current for PTO38 at a shorter wavelength (200 nm), to further enhance the BPV effect. In this scenario, both β33 and β31 contribute positively to the intense formation of opposite charges on the neighboring domain walls due to their opposite signs, as indicated by the simulation results of equilibrium concentrations in Fig. 3h. These opposite charges at the domain walls create opposing electric fields in adjacent domains up to ±1500 kV/cm, as shown in the electric potential profiles in Fig. 3i. This field exceeds the coercive field for typical ferroelectrics, suggesting that the system can possibly create charged DW configurations. However, as we will demonstrate in the subsequent sections with ultrafast simulation results, the transient behavior of ferroelectrics presents even more intriguing phenomena.

Ultrafast domain wall motion

Figure 4 presents the simulation results of ferroelectric domain evolution in PTO under ultrafast pulse illumination using our BPV-DPFM model. Here, we studied the structural dynamics by solving Eqs. (8−9) in the DPFM, which were not considered in previous sections. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, the ultrashort gaussian pulse has a light intensity of 1012 W/cm2, which is centered at 2 ps with a half-width at full maximum (HWFM) of 1 ps. The right panel of Fig. 4a reiterates the generation of opposite charge carriers at DWs and the resulting electric field (EBPV) at a light polarization angle of 0 degrees, as previously discussed in Fig. 3g–i. Figure 4b shows the spatiotemporal evolutions of polarization orientation angle (θ) (defined in Fig. 1b), hole concentration (p) and net free charge density (ρf) along [011] direction of the simulation geometry. We visualize the polarization orientation using a cyclic rainbow colormap, as depicted in the inset of the left panel in Fig. 4b. In this representation, the initial polarization appears as red in the c+ domain, green in the a+ domain, and yellow at the DWs. During the ultrafast optical pulse illumination, which reaches its peak at 2 ps (indicated by the white dashed line), the concentration of electron-hole pairs (with only p shown) rapidly increases within the first 1 ps (center panel of Fig. 4b). This rapid increase slows down as the empty states in the conduction and valence bands are occupied, as described by the Fermi-Dirac distribution. Subsequently, the carrier dynamics are governed by the recombination mechanism over the next 100 ps. These observations (photoexcitation for general semiconductor) are consistent with the results obtained using the DPFM18 proposed by Yang et al. When examining the spatiotemporal evolution of the free charge density (ρf), we observed a transient state when opposite charge carriers segregate at domain walls near the peak of optical pulse at 2 ps, reaching a maximum ρf of ±3 × 108 C/m3 (right panel of Fig. 4b). This value is at least one order of magnitude higher than the typically screened charge carrier concentration at charged domain walls (~107 C/m3). However, these screened charges dissipate rapidly after the optical pulse is off. This is because the domain configuration remains in the alternating a+/c+ pattern, which favors neutral domain walls with lower charge carrier density (right panel of Fig. 4b).

a Schematic illustration of a periodic a/c domain in PbTiO3 (PTO) exposed to an ultrashort gaussian pulse centered at 2 ps, with a HWFM of 1 ps and peak optical intensities of 1012 W/cm². The right panel outlines the generation of opposite carriers at DWs and the resulting electric field (EBPV) at a light polarization angle of 0 degrees, as described in Fig. 3g-i. b The spatiotemporal evolutions of polarization orientation angle θ (defined in Fig. 1b), hole concentration p and net free charge ρf. The 2D images represent the 1D profiles extracted from the simulation geometry along [011] direction at different times, with a time interval of 0.2 ps. The dashed white lines indicate the center of the gaussian pulse, set at 2 ps. c The temporal evolutions of polarization orientation change Δθ at the center of the a- and c- domain. The insets illustrate the rotation of polarization induced by the EBPV, comparing between the a- and c- domains. The initial polarization is depicted in blue, while the polarization after maximum rotation is shown in purple.

Although the a+/c+ domain pattern remains unchanged, we observed notable domain wall movement in response to the ultrafast pulse illumination. This is characterized by the expansion in the a+ domains (green region in the left panel of Fig. 4b) and contraction in the c+ domains (red region) at ~5 ps. This phenomenon can be understood as the system attempts to minimize the electrostatic energy, because the angle between the polarization vector in a+ domain and EBPV is 135 degrees, which possesses higher electrostatic energy compared to that in the c+ domain (in which the angle is 45 degrees). Consequently, the system increases the a+ domain region via DW movement to reduce the electrostatic energy. Remarkably, this DW motion persists up to 5 ps, when the impact of BPV carrier generation already diminishes and the effect of the EBPV weakens due to dissipation in ρf. The domain wall starts to revert to its original position at 10 ps, accompanied by a ripple pattern oscillation in the polarization orientation that lasts for approximately 100 ps. Figure 4c illustrates the temporal evolution of the changes of polarization orientation (Δθ) compared to its initial orientation in the center of the a+ and c+ domains. It is revealed that the polarizations in both domains tilted clockwise, with the a+ domain showing a relatively larger Δθ up to 20 degrees due to the significant torque exerted by the electric field. Each domain exhibited oscillatory behavior around its polarization easy axis with a periodicity of approximately 1 ps, driven by the inertial term in the structural dynamics equation. It is noteworthy that in our BPV-DPFM model, domain wall motion is observed, a phenomenon that is absent in previous DPFM which did not include the BPV effect18. For comparison, the corresponding ultrafast polarization dynamics due to conventional photoexcitation can be found in Supplementary Fig. 5. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating the BPV effect in the DPFM to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the domain dynamics and to potentially achieve rapid domain modulation.

Deterministic manipulation of FE domain configurations

After demonstrating the reversible domain wall motions by an ultrafast single pulse illumination, we further investigated the potential to realize deterministic control of non-volatile domain switching. Intuitively, increasing the peak intensity of the optical pulse should enhance the electric field acting on the polarization vectors. Using the same simulation conditions in a periodic a/c domain of PTO as shown in Fig. 4, we examined the spatiotemporal evolutions of the polarization orientation angle θ and net free charge density ρf (Fig. 5a–c) for peak optical intensities of (a) 2.00 × 1012 W/cm2, (b) 2.15 × 1012 W/cm2, and (c) 2.25 × 1012 W/cm2. Our results indicated that these optical excitations induce nonvolatile changes of the domain configurations from the initial a+/c+ state to (a) a+/c−, (b) a−/c−, and (c) a−/c+, as denoted by the arrows representing polarization directions in the spatiotemporal maps. The underlying mechanisms are summarized in the schematics on the top of Fig. 5a–c.

The spatiotemporal evolution of the polarization orientation angle (lower left panel) and net free charge density ρf (lower right panel) in a periodic a/c domain of PbTiO3 (PTO) in response to an ultrashort gaussian pulse centered at 2 ps, with a HWFM of 1 ps, a light polarization angle of 0 degrees, and peak optical intensities Iph of (a) 2.00 × 1012 W/cm2, (b) 2.15 × 1012 W/cm2, and (c) 2.25 × 1012 W/cm2. The dashed white lines indicate the center of the gaussian pulses, and the arrows indicate the polarization direction and switching from the initial a+/c+ domain configuration to (a) a+/c−, (b) a−/c−, and (c) a−/c + , respectively. The top panels in (a–c) schematically demonstrate the switching mechanism, i.e., the polarization rotation in a clockwise direction and a gradual increase in the maximum polarization rotation (Pmax) in the a+ domain with increasing Iph. d A phase diagram of domain configuration as a function of Iph and strain εzz = −εyy. Different domain configurations are represented by distinct symbols and colors. The inset highlights the enhancement of the electric field EBPV associated with the reduction in domain wall width under anisotropic strain. e Schematics of the accumulation of electrons and holes at domain walls and associated electric field EBPV in a charged domain wall configuration with a light polarization angle of 0 degrees. f The spatiotemporal evolution of the polarization orientation angle (left panel) and ρf (right panel) in a periodic a/c domain of PTO subjected to an anisotropic strain of εzz = −εyy = 0.007. The reversible transition is realized by two sequentially applied ultrashort Gaussian pulses, each with a HWFM of 1 ps. The first pulse is centered at 2 ps with an intensity Iph of 1.3 × 1012 W/cm2, and the second pulse is centered at 52 ps with an intensity Iph of 7.0 × 1012 W/cm2.

As shown in the inset of Fig. 4c, the impact of EBPV on the a+ domain is larger than that of the c+ domain. Here, we focus on the polarization evolutions within the a+ domain. The initial polarization vectors in the a+ domains (green arrows in Fig. 5a–c) gain momentum due to the electrostatic energy of −P·EBPV. This interaction exerts a torque on the polarization, causing it to rotate clockwise (indicated by solid black arrows) to align with EBPV (dashed black arrows). However, due to the large gain in angular momentum, the polarization overshoots due to its inertia and reaches a maximum polarization rotation Pmax (pink arrows). This effect leads to a gradual increase of the Pmax within the a+ domain with increasing optical intensity, as demonstrated in Fig. 5a–c. In scenario (a), where Pmax is located between EBPV and a−, the polarization oscillates and dampens between Pmax and a+, and eventually stabilizes at a+ and c−. During the time interval from 4 ps to 15 ps, the alternating a/c domain structure creates four charged domain walls, which then stabilize into two charged domain walls after domain merging completes, neutralizing the opposite charges of the redundant domain walls (Fig. 5a). This confirms that transition from neutral to charged domain walls is feasible through ultrafast single pulse illumination. In scenario (b), where Pmax extends beyond EBPV and over a−, the domain configuration transforms from a+/c+ to a−/c−, both of which possessing neutral domain walls. The charged domain wall state persists only for 30 ps (Fig. 5b). This is attributed to the larger ferroelectric orientation crossing over to another ferroelectric axis (a−). The polarization oscillates and dampens between a−/c−, eventually stabilizing at these two easy axes. In scenario (c), increasing the optical peak intensity results in a direct transformation from a+ to a− domains, achieving a 180-degree reversal within the original a-domain (Fig. 5c). This scenario avoids the long-term evolution of ferroelectric polarization, with the entire process completing within 10 ps. It is noteworthy that the domain manipulation as described above is feasible for a variety of combinations of light polarization angles and BPV tensor coefficients, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 7. Figure 5d presents a phase diagram summarizing the conditions required for precise control of domain reconfigurations using ultrafast pulse illumination. In addition to the effect of the optical peak intensity (Iph), the anisotropic strain (εzz = −εyy), which reduces the size of a-domains, can also be harnessed to enhance the efficiency of domain manipulation. The equilibrium domain under this anisotropic strain is summarized in Supplementary Fig. 8. This enhancement can be understood from two perspectives. First, the thermodynamic environment under anisotropic strain does not favor the existence of a-domains, reducing their volumetric ratio and making the polarization within these domains easier to switch. Second, and more significantly, the reduction in domain wall spacing enhances the electric field within the a+ domain (highlighted in the black dashed box of the inset in Fig. 5d), providing greater angular momentum to drive the structural dynamics. This dual mechanism underscores the increased effectiveness of domain manipulation under the combined influence of ultrafast pulse illumination and anisotropic strain.

To verify the feasibility of non-volatile control in domain configurations, it is crucial to demonstrate the ability to switch between distinct states. Our findings indicate that switching between a+/c+ and a−/c− configurations can be readily achieved due to their periodic head-to-tail domain structures (see Supplementary Fig. 9). This toggling effectively reverses the net polarization direction, alternating between left and right (Fig. 5b), and consequently, inverts the macroscopic BPV current. This insight holds significant implications for device applications. Conversely, transforming charged domain wall structures back to the original neutral domain configuration proved unfeasible. The BPV effect within charged domain wall structures generates carriers of the same sign along the domain wall, stabilizing the charged configuration. Supplementary Fig. 10 corroborates that this stabilization tendency is independent of the light polarization angle and the BPV tensor coefficients’ sign or relative magnitude. However, we discovered that domain manipulation within charged domain wall configurations becomes possible when the a/c domain in PbTiO3 (PTO) is subjected to anisotropic strain.

Figure 5e illustrates the accumulation of electrons and holes at domain walls and the associated electric field in a charged domain wall configuration with a light polarization angle of 0 degrees. Although the initial charged domain wall configuration remains preferred, the enhanced electric field EBPV within the a+ domain can rotate the polarization over EBPV to Pmax. This dynamic facilitates the transition from the initial a+/c− domain configuration to a+/c+. Our simulations demonstrate this concept in a periodic a+/c+ domain of PTO subjected to an anisotropic strain of εzz = −εyy = 0.007. Two ultrashort gaussian pulses were sequentially applied: the first centered at 2 ps with an intensity of 1.3 × 1012 W/cm2, and the second at 52 ps with an intensity of 7.0 × 1012 W/cm2. As shown in the polarization orientation angle map in Fig. 5f, we successfully demonstrate the transition from an initial a+/c+ domain configuration to a+/c− and back to the initial a+/c+ state. The corresponding free charge density (ρf) transits from neutral DWs to charged DWs, and then back to neutral DWs. This setup exemplifies the non-volatile and reversible manipulation of the system using an all-optical approach, underscoring the potential for ultrafast optical control in ferroelectric devices.

Discussion

In this work, we develop a comprehensive model to explore the bulk photovoltaic (BPV) effect and its influence on the structural and electronic evolution of ferroelectrics under above-bandgap illumination. Our model successfully reproduces the anomalous BPV effect at domain walls in ferroelectrics with alternating domains, highlighting a significant enhancement of the BPV tensor associated with structural transitions at these walls. This observation aligns with previous studies demonstrating that domain walls are particularly susceptible to such effects due to their unique electronic and structural properties42,48,50,51.

We have demonstrated the ultrafast modulation capabilities, enabling not only the reversible movement of domain walls but also deterministic control over domain configurations and domain-wall charge states through ultrafast pulsed laser illumination. These optical modulation effects are confirmed in conventional wide-bandgap ferroelectrics with robust domains. However, we anticipate even greater efficiency in ferroelectric semiconductors37 that are activated by visible light, particularly in systems where quasi-steady states of ferroelectric polarizations are separated by relatively low energy barriers. Notably, our results suggest that light-induced structural phase transitions, accompanied by polarization switching, may occur in systems near the morphotropic phase boundary, potentially resulting in more pronounced changes in material properties25,26.

Since we approximate the electric response as quasi-static even in the ultrafast regime, the current simulation inherently neglects electrodynamic effects. In Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 11, we demonstrate that the transient variation in BPV current leads to electromagnetic self-induction, generating an electric field that opposes the BPV current direction. This induced field reaches a magnitude of up to 2000 kV/cm during the ultrafast pulse. Under the experimental configuration shown in Fig. 4, the induced electric field stabilizes the c-domain while destabilizing the a-domain during the pulse duration. Notably, this induced electric field has a comparable impact on polarization dynamics during the pulse. Despite this, we suggest that the quasi-static approximation serves as a reasonable starting point for investigating polarization dynamics in response to the BPV effect, particularly for ferroelectrics that cannot respond instantaneously to ultrafast pulses. Further discussion on this topic is available in the Supplementary Information.

Understanding the influence of defects is crucial for interpreting simulations of the bulk photovoltaic (BPV) effect, as real ferroelectric materials are rarely free of structural imperfections54,55,56,57,58,59. Defects, such as oxygen vacancies, generate localized electric fields and strains, trap carriers, and modulate charge transport, thereby playing a critical role in shaping polarization dynamics. These defect-driven inhomogeneities not only enhance local BPV generation efficiency60,61 but also induce spatial variations in polarization response, leading to non-uniform charge separation and domain evolution. Furthermore, defects can alter carrier dynamics by acting as recombination centers and attenuating intense BPV-generated fields, while localized strain and charge distributions can pin domain walls57, affecting polarization stability and switching behavior. While the simulations presented here did not consider the effects of defects, which allows us to focus on the intrinsic BPV mechanisms, extending these models to include defect dynamics would enable a more comprehensive understanding of their roles. Incorporating defect-related phenomena54,55,56,57 in future studies will provide deeper insights into the interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic factors, offering a pathway to more accurate modeling of ferroelectric systems and enhanced design strategies for practical applications.

Our model not only offers valuable insights into the behavior of ferroelectrics under optical stimuli but also paves the way for groundbreaking advancements in ultrafast ferroelectric technologies. These applications range from all-optical logic circuits and ferroelectric memory devices to domain-wall-based nanoelectronics, all benefiting from the improved control and efficiency driven by light-induced phenomena. These findings present exciting opportunities for enhancing next-generation electronic devices and provide a strong foundation for further exploration into light-induced ferroelectric phenomena.

Methods

Dynamical phase-field calculation

The DPFM18,31,49 is implemented using the COMSOL Multiphysics software. The model includes four sets of field variables that vary over space x = (x, y, z) and time t, including the ferroelectric polarization P = (Px, Py, Pz), the mechanical displacement u = (u, v, w), the free electron and hole concentrations n and p, and the electric potential V. The Cartesian coordinates x correspond to the pseudocubic crystallographic axes of the perovskite ferroelectrics. As summarized in Fig. 1b, the spatiotemporal dynamics of the ferroelectric system upon ultrafast optical excitation can be described by the coupled structural dynamics equations and drift-diffusion-Poisson equations. The former is constructed using the polarization dynamics equation (Eq. 8) and the elastodynamics equation (Eq. 9), i.e.,

in which μ and γ represent the effective mass and damping coefficients associated with the polarization, while ρ and β are the volumetric mass density and the stiffness damping coefficient. σ represents the stress field calculated from the Hooke’s law, i.e., \({\sigma }_{{\rm{ij}}}={C}_{{\rm{ijkl}}}{e}_{{\rm{kl}}}={C}_{{\rm{ijkl}}}({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{kl}}}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{kl}}}^{0})\). Here \({C}_{{\rm{ijkl}}}\) is the elastic stiffness tensor, and \({e}_{{\rm{kl}}}\) is the elastic strain. Based on the micro-elasticity theory, \({e}_{{\rm{kl}}}\) can be calculated from the difference between the total strain (\({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{kl}}}\)) and the eigenstrain (\({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{kl}}}^{0}\)), where \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{kl}}}=[\nabla {\bf{u}}+{(\nabla {\bf{u}})}^{{\rm{T}}}]/2\) and \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{ij}}}^{0}={Q}_{{\rm{ijkl}}}{P}_{{\rm{k}}}{P}_{{\rm{l}}}\). \({Q}_{{\rm{ijkl}}}\) is the electrostrictive coefficient tensor which correlates \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{kl}}}^{0}\) with the polarization (\({P}_{{\rm{i}}}\)). F in Eq. (8) denotes the total free energy of ferroelectric domains according to the Landau–Ginzburg–Devonshire (LGD) theory. It is expressed as the sum of the Landau bulk free energy FLandau, gradient energy Fgrad, electrostatic energy Felec, and elastic energy Felastic.

where the integrand represents the volume integral of the corresponding free energy densities. The symbol Ω denotes the simulation domain in three-dimensional (3D) space. The formulations for each energy density are as follows.

where ai, aij, aijk, and aijkl are the Landau energy coefficients under a stress-free condition. G is the gradient energy coefficients. ε0 and κij are the vacuum permittivity and relative dielectric permittivity, respectively. E is the electric field given by E = − ∇V, which is obtained after solving the drift-diffusion-Poisson equations for the ferroelectric domain structure P(x, t),

where ρf represents the free-charge density, defined as \({\rho }_{\text{f}}=q\left(p-n+{N}_{\text{D}}^{+}-{N}_{\text{A}}^{-}\right)\), where q is the elementary charge, and \({N}_{\text{D}}^{+}\) and \({N}_{\text{A}}^{-}\) denote the ionized donor and acceptor concentrations, respectively. Jn and Jp represent the electron and hole current densities, respectively, which consist of both drift and diffusion contributions:

in which μn and μp are the electron and hole mobilities, respectively. The conduction band edge EC and the valence band edge EV are given by EC = −q(χ + V) and EV = −q(χ + Eg + V), where χ and Eg are the electron affinity and the energy gap, respectively. kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature, which is set to be 298 K in our simulation. The functions g(n/NC) and g(p/NV) represent the degeneracy factors for electrons and holes, respectively. These functions approach 1 in the nondegenerate limit but can increase to ~15 in response to intense pulse illumination. A detailed formulation of the g function, along with its properties and implementation, is provided in Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Table 3. Here, NC denotes the effective density of states in the conduction band for electrons, while NV denotes the effective density of states in the valence band for holes. The generation rates Gn and Gp in Eqs. (15) and (16) arise from the BPV effect and can be expressed as,

where JBPV(x, t) is the shift current bulk photovoltaic current density for a ferroelectric domain structure. The generation rate of electron-hole pairs (Gph) under photoexcitation, assuming a two-parabolic-band model for a general semiconductor, is given by refs. 17,18

where the light intensity Iph is a constant value when simulating the macroscopic BPV characteristic but can become time-dependent in the ultrafast simulation by multiplying it with a gaussian pulse profile \({e}^{-4\mathrm{ln}2{(\frac{t-{t}_{0}}{d})}^{2}}\), where t0 and d represent the center and the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the pulse, respectively. ωph is the angular frequency of the light. c and ℏ are the speed of light in a vacuum and the reduced Planck constant. me, \({m}_{\text{e}}^{* }\) and \({m}_{\text{h}}^{* }\) are the electron mass, the effective mass of electrons, and the effective mass of holes. fF is a Fermi-Dirac function, expressed as fF(x) = [exp(x/kBT)+1]−1. The quasi-Fermi levels Efn and Efp, which describe the carrier concentrations away from equilibrium, are related to the effective density of states by:

in which \({F}_{1/2}^{-1}\left(x\right)\) is the inverse Fermi-Dirac integral of order 1/2. The recombination rate R in Eqs. (15) and (16) is governed by the Shockley-Read-Hall model (see Supplementary Note 1), which accounts for steady-state recombination through states located at the mid-gap. For simplicity, we assume that the defect level is aligned with the intrinsic Fermi level for recombination.

where τn and τp are the electron and hole lifetimes, respectively. ni is the intrinsic carrier concentration.

In the finite-element simulation of the BPV effect for bulk ferroelectrics, we employed a 3D thin-beam ferroelectric model with dimensions of 0.2 × 0.2 × 60 nm3 to optimize computational efficiency. The orientation of the geometry was aligned with the periodicity of the physical problem, taking into account the domain wall direction and electrode placement. Specifically, the long axis of the geometry was aligned along the [001] axis for single-domain studies, and along the [011] axis for multi-domain studies. To ensure accurate local current continuity in the drift-diffusion-Poisson system, the mesh size was set to be less than 0.2 nm, given a ferroelectric domain wall width of approximately 1 nm, and using Lagrange quadratic shape functions. To simulate the bulk behavior of the ferroelectrics, we applied periodic boundary conditions for the ferroelectric polarization P at each pair of boundaries. For mechanical displacement, modified periodic boundary conditions were implemented to account for the applied strain, for instance, u(x = L) = u(x = 0) + ΔL, where the strain εxx = ΔL / L. In simulating the equilibrium BPV characteristics as functions of the applied bias V0, the light intensity Iph, and the light polarization angle θ using a stationary solver, we imposed a modified ohmic contact boundary condition on electrodes 1 and 2, while maintaining periodic boundary conditions on other pairs. Specifically, Dirichlet boundary conditions were applied on the electrodes with V1 = Veq and V2 = Veq + V0, and with n1 = n2 = neq,illuminated and p1 = p2 = peq,illuminated. Here, Veq is the vacuum potential referenced to the Fermi level in the equilibrium configuration. The values of neq,illuminated and peq,illuminated, which is related to the photoexcitation characteristic for general semiconductors, were obtained from a separate time-dependent initial value problem starting from their intrinsic carrier concentrations, in response to various optical intensities with no-flux boundary conditions for n and p on all boundaries (BPV terms were not included here). The current density flowing through the electrodes was defined as \(\hat{{\bf{n}}}\)·Jtotal, where \(\hat{{\bf{n}}}\) is the surface normal for the top electrode and Jtotal is expressed as Jtotal = Jn + Jp + JBPV. To simulate quasi-equilibrium carriers and electrical profiles under intense steady illumination of ferroelectrics, a time-dependent initial value problem was initiated from their intrinsic carrier concentrations. This simulation responded to BPV optical excitation with no-flux boundary conditions for n and p applied to all boundaries. A simulation time of 1 ps was utilized to achieve a quasi-equilibrium state. For the simulation of domain modification under ultrafast pulse illumination, we applied periodic boundary conditions for n, p, and V at each pair of boundaries. The initial multi-domain structures for studying the equilibrium BPV response and associated ultrafast domain dynamics are stabilized by solving a conventional ferroelectric phase-field model. This involves using the structural dynamics equation with parameters μ, ρ, and β set to zero, and the Poisson equation with the free charge density ρf set to zero. A fixed time step of 1 fs was adopted in the time-dependent studies upon ultrafast optical excitation.

Bulk photovoltaic tensor and its rotational transformation

The bulk photovoltaic tensor, which relates the BPV current density to the light polarization, is characterized by a third-rank tensor:

where the symbol ∣ separates the tensor elements corresponding to different layers of the first index. The BPV effect is a second-order nonlinear optical process. Due to the permutation symmetry in the interaction between the light polarization and the crystal structure in non-centrosymmetric materials, the tensor components satisfy the relation βijk = βikj. For simplicity, we express this tensor in matrix notation using the transformation βijk = βim, where the indices are mapped as follows: jk→m, with 11 → 1; 22 → 2; 33 → 3; 23, 32 → 4; 13, 31 → 5; 12, 21 → 6.

In materials with tetragonal symmetry (point group 4 mm), such as ferroelectric BaTiO3 and PbTiO3, only the components β33, β31, and β15 are non-zero. Thus, the reduced BPV tensor can be expressed in terms of tensor notation and matrix notation as follows:

where the off-diagonal components require a division by 2 to account for the symmetry and avoid duplication from the transformation between tensor and matrix form.

The BPV tensor, as defined here, pertains to a crystal where the polarization points upward, with the pseudo-cubic axis of a (001)-oriented ferroelectric aligned with the laboratory coordinates. When the polarization aligns with other easy axes, a conversion of the BPV tensor from its crystallographic representation to laboratory coordinates is necessary to accurately calculate the BPV current density corresponding to a specific light polarization in the laboratory frame. In the context of tetragonal symmetry, the alignment scenarios are as follows:

-

1.

When the polarization is aligned upward, it is parallel to the c-axis (crystallographic), the z-axis (pseudo-cubic), and the z-axis (laboratory). No transformation of the BPV tensor is required.

-

2.

When the polarization deviates from the upward direction, it remains parallel to the c-axis (crystallographic) but is not parallel to the z-axis (laboratory), while the pseudo-cubic axes remains aligned with the laboratory axes. A conversion of the BPV tensor is necessary.

The transformation can be grasped by expressing the local polarization in spherical coordinates (r, θ, φ). An atan2 function is then utilized to ensure a correct and unambiguous determination of the angles θ and φ.

Subsequently, two rotational transformations are applied using the Euler angles obtained. First, a rotation around the y-axis by an angle θ is performed (a rotational matrix of Yθ was used)), followed by a rotation around the z-axis by an angle φ (a rotational matrix of Zφ was used) to derive the new BPV tensor (\({\beta}_{\rm{ijk}}^{\prime\prime}\)) in the laboratory coordinate system. The subsequential rotation of the third-rank tensor is expressed as62,63:

A similar procedure can be extended to ferroelectrics possessing rhombohedral, orthorhombic, or monoclinic crystal systems. This transformation guarantees that the BPV tensor precisely represents the symmetry characteristics and local polarization orientation within the laboratory frame. Code to generate the full expression of BPV current density components for any ferroelectric orientation and light polarization is available in the Supplementary Note 4.

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Codes supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Scott, J. F. Applications of modern ferroelectrics. Science 315, 954–959 (2007).

Scott, J. F. & Paz de Araujo, C. A. Ferroelectric memories. Science 246, 1400–1405 (1989).

Zhang, S. et al. Advantages and challenges of relaxor-PbTiO3 ferroelectric crystals for electroacoustic transducers – a review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 68, 1–66 (2015).

Song, X.-J. et al. The first demonstration of strain-controlled periodic ferroelectric domains with superior piezoelectric response in molecular materials. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211584 (2023).

Tikhomirov, O. & Lee, C. G. Electro-optic control of optical beams by rearrangement of the ferroelectric domain structure. Solid State Commun. 148, 350–352 (2008).

Hu, X., Zhang, Y. & Zhu, S. Nonlinear beam shaping in domain engineered ferroelectric crystals. Adv. Mater. 32, 1903775 (2020).

Liu, Y., Ren, G., Cao, T., Mishra, R. & Ravichandran, J. Modeling temperature, frequency, and strain effects on the linear electro-optic coefficients of ferroelectric oxides. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 163101 (2022).

Uchino, K. Ferroelectric devices (Marcel Dekker, 2000).

Jin Hu, W., Wang, Z., Yu, W. & Wu, T. Optically controlled electroresistance and electrically controlled photovoltage in ferroelectric tunnel junctions. Nat. Commun. 7, 10808 (2016).

Choi, T., Lee, S., Choi, Y. J., Kiryukhin, V. & Cheong, S.-W. Switchable ferroelectric diode and photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Science 324, 63–66 (2009).

Guo, R. et al. Non-volatile memory based on the ferroelectric photovoltaic effect. Nat. Commun. 4, 1990 (2013).

Li, D. & Bonnell, D. A. Controlled patterning of ferroelectric domains: fundamental concepts and applications. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 38, 351–368 (2008).

Wang, J. et al. Ferroelectric domain-wall logic units. Nat. Commun. 13, 3255 (2022).

Lopez-Varo, P. et al. Physical aspects of ferroelectric semiconductors for photovoltaic solar energy conversion. Phys. Rep. 653, 1–40 (2016).

Tan, L. Z. et al. Shift current bulk photovoltaic effect in polar materials—hybrid and oxide perovskites and beyond. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 16026 (2016).

Dai, Z. & Rappe, A. M. Recent progress in the theory of bulk photovoltaic effect. Chem. Phys. Rev. 4, 011303 (2023).

Shi, Y. & Chen, L.-Q. Spinodal electronic phase separation during insulator-metal transitions. Phys. Rev. B 102, 195101 (2020).

Yang, T. & Chen, L.-Q. Dynamical phase-field model of coupled electronic and structural processes. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 130 (2022).

Takahashi, K., Kida, N. & Tonouchi, M. Terahertz radiation by an ultrafast spontaneous polarization modulation of multiferroic BiFeO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 117402 (2006).

Daranciang, D. et al. Ultrafast photovoltaic response in ferroelectric nanolayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 087601 (2012).

Kimel, A. V., Kalashnikova, A. M., Pogrebna, A. & Zvezdin, A. K. Fundamentals and perspectives of ultrafast photoferroic recording. Phys. Rep. 852, 1–46 (2020).

Grübel, S. et al. Ultrafast x-ray diffraction of a ferroelectric soft mode driven by broadband terahertz pulses. arXiv:1602.05435 (2016).

Li, Q. et al. Subterahertz collective dynamics of polar vortices. Nature 592, 376–380 (2021).

Manz, S. et al. Reversible optical switching of antiferromagnetism in TbMnO3. Nat. Photon. 10, 653–656 (2016).

Liou, Y. D. et al. Extremely fast optical and nonvolatile control of mixed-phase multiferroic BiFeO3 via instantaneous strain perturbation. Adv. Mater. 33, 2007264 (2021).

Liou, Y. D. et al. Deterministic optical control of room temperature multiferroicity in BiFeO3 thin films. Nat. Mater. 18, 580–587 (2019).

Li, T. et al. Optical control of polarization in ferroelectric heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 9, 3344 (2018).

Kundys, D. et al. Optically rewritable memory in a graphene-ferroelectric-photovoltaic heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 064034 (2020).

Long, X., Tan, H., Sánchez, F., Fina, I. & Fontcuberta, J. Non-volatile optical switch of resistance in photoferroelectric tunnel junctions. Nat. Commun. 12, 382 (2021).

Yan, S. et al. Large-scale optical manipulation of ferroelectric domains in PMN-PT crystals. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2201092 (2022).

Akamatsu, H. et al. Light-activated gigahertz ferroelectric domain dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 096101 (2018).

Rubio-Marcos, F., Del Campo, A., Marchet, P. & Fernández, J. F. Ferroelectric domain wall motion induced by polarized light. Nat. Commun. 6, 6594 (2015).

Rubio-Marcos, F. et al. Reversible optical control of macroscopic polarization in ferroelectrics. Nat. Photon. 12, 29–32 (2018).

Xue, F. et al. Optoelectronic ferroelectric domain-wall memories made from a single van der waals ferroelectric. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2004206 (2020).

Ordoñez-Pimentel, J. et al. Light-driven motion of charged domain walls in isolated ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 106, 224110 (2022).

Yang, M. M. & Alexe, M. Light-induced reversible control of ferroelectric polarization in BiFeO3. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704908 (2018).

Vats, G., Bai, Y., Zhang, D., Juuti, J. & Seidel, J. Optical control of ferroelectric domains: nanoscale insight into macroscopic observations. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1800858 (2019).

Young, S. M. & Rappe, A. M. First principles calculation of the shift current photovoltaic effect in ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 116601 (2012).

Young, S. M., Zheng, F. & Rappe, A. M. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in bismuth ferrite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 236601 (2012).

Laman, N., Bieler, M. & van Driel, H. M. Ultrafast shift and injection currents observed in wurtzite semiconductors via emitted terahertz radiation. J. Appl. Phys. 98, 103507 (2005).

Sturman, B., Kösters, M., Haertle, D., Becher, C. & Buse, K. Optical cleaning owing to the bulk photovoltaic effect. Phys. Rev. B 80, 245319 (2009).

Noguchi, Y., Inoue, R. & Matsuo, H. Domain-wall photovoltaic effect in Fe-doped BaTiO3 single crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 084101 (2021).

Nastos, F. & Sipe, J. E. Optical rectification and shift currents in GaAs and GaP response: below and above the band gap. Phys. Rev. B 74, 035201 (2006).

Sipe, J. E. & Shkrebtii, A. I. Second-order optical response in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 61, 5337–5352 (2000).

von Baltz, R. & Kraut, W. Theory of the bulk photovoltaic effect in pure crystals. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5590–5596 (1981).

Koch, W. T. H., Munser, R., Ruppel, W. & Würfel, P. Bulk photovoltaic effect in BaTiO3. Solid State Commun. 17, 847–850 (1975).

Fridkin, V. M. Bulk photovoltaic effect in noncentrosymmetric crystals. Crystallogr. Rep. 46, 654–658 (2001).

Inoue, R. et al. Giant photovoltaic effect of ferroelectric domain walls in perovskite single crystals. Sci. Rep. 5, 14741 (2015).

Yang, T., Wang, B., Hu, J.-M. & Chen, L.-Q. Domain dynamics under ultrafast electric-field pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 107601 (2020).

Peng, W. et al. Constructing polymorphic nanodomains in BaTiO3 films via epitaxial symmetry engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1910569 (2020).

Li, M. et al. Atomic-environment-dependent thickness of ferroelastic domain walls near dislocations. Acta Mater. 188, 635–640 (2020).

Jo, J. Y., Kim, Y. S., Noh, T. W., Yoon, J.-G. & Song, T. K. Coercive fields in ultrathin BaTiO3 capacitors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 232909 (2006).

Chen, N.-K. et al. Optical subpicosecond nonvolatile switching and electron-phonon coupling in ferroelectric materials. Phys. Rev. B 102, 184115 (2020).

Kumar, R., Zhang, S. & Ganesh, P. Modeling kinetic effects of charged vacancies on electromechanical responses of ferroelectrics: Rayleighian approach. Phys. Rev. Res 7, 013059 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Li, J. & Fang, D. Oxygen-vacancy-induced memory effect and large recoverable strain in a barium titanate single crystal. Phys. Rev. B 82, 064103 (2010).

Cao, Y., Shen, J., Randall, C. & Chen, L.-Q. Effect of ferroelectric polarization on ionic transport and resistance degradation in BaTiO3 by phase-field approach. J. Am. CerAm. Soc. 97, 3568–3575 (2014).

Fedeli, P., Kamlah, M. & Frangi, A. Phase-field modeling of domain evolution in ferroelectric materials in the presence of defects. Smart Mater. Struct. 28, 035021 (2019).

Lee, J. et al. Role of oxygen vacancies in ferroelectric or resistive switching hafnium oxide. Nano Converg. 10, 55 (2023).

Henning, X. et al. Oxygen vacancy effects on polarization switching of ferroelectric Bi2FeCrO6 thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 054416 (2024).

Mai, H. et al. Defect engineering for creating and enhancing bulk photovoltaic effect in centrosymmetric materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 13182–13191 (2021).

Noguchi, Y., Taniguchi, Y., Inoue, R. & Miyayama, M. Successive redox-mediated visible-light ferrophotovoltaics. Nat. Commun. 11, 966 (2020).

Wu, J. et al. Unconventional piezoelectric coefficients in perovskite piezoelectric ceramics. J. Materiomics 7, 254–263 (2021).

Bhatnagar, A., Roy Chaudhuri, A., Heon Kim, Y., Hesse, D. & Alexe, M. Role of domain walls in the abnormal photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Nat. Commun. 4, 2835 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Y.C. acknowledges the support of the National Science Foundation via grant CMMI-2132105.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D.L. developed the BPV model, conducted the phase-field simulation, and wrote the manuscript. K.Z. established the initial ferroelectric model. Y.C. conceived the idea, supervised the project, analyzed data, and co-wrote the paper. All authors (Y.D.L., K.Z., and Y.C.) participated in discussing the results, and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions