Abstract

The ability to rapidly evaluate materials properties through atomistic simulation approaches is the foundation of many new artificial intelligence-based approaches to materials identification and design. This depends on the availability of accurate descriptions of atomic bonding and an efficient means for determining materials properties. We present an efficient, robust platform for calculating materials properties from a wide-range of atomic bonding descriptions, i.e., APEX, the Alloy Property Explorer. APEX enables the rapid evolution of interatomic potential development and optimization, which is of particular importance in fine-tuning new classes of general AI-based foundation models for applications in materials science and engineering. APEX is an open-source, extendable, cloud-native platform for material property calculations using a range of atomistic simulation methodologies that effectively manages diverse computational resources and is built upon user-friendly features including automatic results visualization, a web-based platform and a NoSQL database client. It is designed for expert and non-specialist users, lowering the barrier to entry for interdisciplinary research within an “AI for Materials” framework. We describe the foundation and use of APEX, as well as provide two examples of its application to properties of titanium and 179 metals and alloys for a wide-range of bonding descriptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) techniques have advanced rapidly in the past decade, paralleling the growth of high-performance computing, cloud infrastructure, and data storage hardware. These developments have spurred the widespread application of AI methods in scientific discovery, giving rise to the interdisciplinary field ‘AI for Science’1. As a sub-domain in this field, ‘AI for Materials’ (AI4M) has become an essential component in materials science research and development that enhances our understanding of composition-structure-property relationships and facilitates the design of materials with targeted properties2,3,4. Data acquisition and analysis are fundamental steps in materials science, like in other scientific disciplines. However, unlike conventional computer science fields, where large datasets are readily available5, data related to composition-structure-property relationships are often sparse6,7. This scarcity poses a challenge to the progress of AI4M. Consequently, there is a pressing need for efficient and robust approaches in materials science that enable the generation of extensive and comprehensive datasets.

Experimental measurements and testing of materials properties across a broad expanse of composition space is both time-consuming and costly, with results sometimes varying substantially among different methods8. Quantum mechanics (QM)-based methods, such as density functional theory (DFT), generally provide accurate material properties and can generate vast datasets complementary to experimental databases. This strategy has led to the establishment of several well-known databases, including Materials Project (MP)9, AFLOW10, Open Quantum Materials Database11 (OQMD), …Despite their accuracy, QM methods are computationally demanding and impractical for calculating materials properties determined on large length and/or timescales, including defect properties/interactions12, thermal transport properties13, and atomic and ionic diffusivity14. Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations offer a more efficient alternative, but their accuracy is often limited by the inadequate reliability of empirical interatomic potentials15. Over the past two decades, machine learning (ML) methods have been employed to develop interatomic potentials, yielding ML potentials (MLPs) that have successfully achieved accurate descriptions of various materials properties15,16.

By leveraging pre-training approaches (based on large, multi-element databases, e.g., MP), several research groups developed pretrained or foundation models for atomistic simulations2,17,18,19,20,21. These foundation models can attain DFT-level accuracy through a fine-tuning process on considerably smaller training datasets and fewer training steps compared to training from scratch. This approach appears to be a promising alternative for generating massive materials property datasets. However, several challenges remain, including (i) validating and guiding the fine-tuning process of foundation models for specific materials properties and (ii) efficiently applying those large atomic foundation models to generate extensive materials property datasets in a high-throughput manner for further application like AI-aided inverse materials design22,23. These challenges call for more practical, automated, and robust tools for rapid property exploration through different simulation methods.

In the past decade, the integration of various tools and libraries has greatly advanced the field of atomistic simulations. Such tools include, for example, first-principle calculators such as VASP24, Quantum Espresso25, Abinit26, ABACUS27, and CP2K28, and atomistic simulators such as LAMMPS29, GROMACS30, NAMD31, and CHARMM32. A comprehensive simulation ecosystem also exists to support model development and post-analysis tools, e.g., Pymatgen33, Atomsk34, Atomman35, and VASPKIT36. There are several integrated simulation and development environment packages, such as ASE37, Pyiron38, JARVIS39, pylada40 and iprPy41, that offer extensive application programming interfaces (APIs) that allow for the customization of property simulation routines. Despite their versatility, these packages often require users to have a certain level of coding proficiency and a deep understanding of their APIs to effectively manage property test scripts and configure local computational resources. LAVA42 aims to simplify this process by providing a collection of Python scripts that wrap around common property calculation routines, making them more accessible to newcomers. However, the rigid coding structure and limited task control capabilities of LAVA make it less suitable for large-scale property and configuration space exploration. Current tools often encounter performance and scalability challenges when managing large-scale simulations and workflows, primarily due to hardware constraints and heavily reliance on local deployment and configuration. They often lack an intuitive process monitoring scheme, which is essential for efficient simulation management. A well-encapsulated, ready-to-use property simulation tool that incorporates adaptive and advanced features for high-throughput production scenarios could address many of these gaps. Features including distributed computing management, intuitive process controls, and robust task monitoring would enhance user experience and workflow efficiency.

Here, we introduce APEX (Alloy Property EXplorer), an open-source Python framework designed to generate automatic materials property calculation workflows using either MD or QM methods that initially focusses on issues of special interest for metallic alloys. Figure 1 shows a schematic of APEX that integrates job preparation, submission, computation, on-the-fly process monitoring, and post-processing into seamless cloud-native workflows. It adopts containers to decouple computing and scheduling, ensuring that software packages operate in isolated (container) environments, which consequently enhances scalability, load balancing and portability for modern computing infrastructures (e.g. cloud server and high-performance computers, HPCs). APEX incorporates user-friendly features, including results visualization, a web-based platform and a NoSQL database client for automatic data storage. While APEX currently focusses on a set of property calculators, it is easily adaptable to include other property calculations and accommodate additional DFT/MD packages. For the rapid-evolving field of AI4M, APEX has the potential to serve as a robust and efficient framework that enables the evaluation of different MLPs as well as empirical interatomic potentials for further fine-tuning, an “engine” for establishing a leaderboard covering different materials (defect) properties, calculating materials properties in a standardized and high-throughput manner, and generating massive datasets for AI model training. APEX reduces the learning barrier by incorporating user-friendly features and containerization that foster collaboration across interdisciplinary AI4M.

Results

APEX structure

Figure 2a shows the layered architecture of APEX. The top layer represents the user interface (UI), which supports both web-based apps and terminal commands, to enable users to submit computing jobs (as per their preferences). This UI is built using the graphical user interface (GUI) supported by the Bohrium platform41. In addition to a UI, the major components of APEX reside in the light yellow layer, comprising the “workflow”, “database client”, and “visualizer” modules. APEX workflows are orchestrated using Dflow43, a Python-based framework specifically designed for constructing scientific computing workflows. Between Dflow and APEX, there are two essential components (dark yellow): (1) models - including large atomic models (LAM), MLPs, classical potentials/empirical force fields (FF), and DFT and (2) engines - consisting of different “OP” (operations) tailored for each specific model. Dflow provides a suite of elements for defining fundamental operational units and a collection of methods for assembling these units into comprehensive workflows. A fundamental layer of Dflow is the cloud-native Argo workflow engine41, which utilizes Docker41 containers to separate computing from scheduling logic. Kubernetes41 orchestrates the management of these containers, ensuring that the workflows are easily monitored, reproducible, and resilient. This containerization optimizes workflow flexibility and facilitates the effective harnessing of diverse computational resources (including distributed, heterogeneous infrastructures such as cloud services and high-performance computing (HPC) clusters).

a APEX is built on the Dflow constructor43, providing support for both terminal and web-based user interfaces, and enable interaction with personal computers (PCs), high-performance computers (HPCs) and cloud resources. “Emp. FF” represents empirical force fields (classical potentials) and “engine” consists of different “OP” (operations) tailored for each specific model. b APEX accommodates both first-principles (FP) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, including the use of machine learning potentials (MLPs) and empirical interatomic potentials such as modified embedded atom method (MEAM) potentials. Various property calculations by FP or MD are executed concurrently and in parallel, utilizing either CPU, GPU-based machines or cloud resources.

The tree diagram in Fig. 2b outlines the methodology by which APEX organizes multiple property exploration tasks. The process begins with the provision of JSON files that define global settings and computational parameters. APEX currently interfaces with LAMMPS29 for MD simulations and VASP24 and ABACUS27 for DFT calculations. A single work path is responsible for either MD or DFT calculations for one material instance. Before computation, all necessary files, such as interatomic potentials for LAMMPS or INCAR and POTCAR files for VASP, must be specified. Each local working directory contains multiple subdirectories, with different starting atomistic structural configurations. These configurations can be concurrently tested by leveraging uniform global settings. In the terminal UI, an array of property calculation tasks, as designated by the parameter file, are automatically generated and executed in parallel for each configuration. This concurrent processing approach facilitates high-throughput and efficient evaluation of materials properties.

Figure 3 presents the APEX workflow procedure. The initiation of the workflow is triggered by providing input JSON files and local working directories. APEX then employs these inputs to automatically select the appropriate workflow from three predefined job types: “relaxation”, “property”, and “joint”. The “relaxation” workflow is designated for structural optimization and proceeds sequentially through three operations (OPs). The RelaxationMake OP receives one or multiple initial structural configurations, using them to set up task-specific directories containing all necessary files for calculation. This OP is followed by the Run OP, which distributes tasks into numerous operations for parallel and concurrent execution using a designated computational package for either DFT or MD calculations. After structural optimization of the various configurations is completed, the RelaxationPost OP performs the required post-processing and produces the optimized ground-state results for the respective structures. The “property” workflow is tailored for the calculation of specific material properties, building upon the optimized structures obtained from the “relaxation” workflow. Similarly, the PropertyMake OP first prepares the necessary calculation files, including structure configurations and input parameters for DFT or MD simulations for specific type of property calculations. Then, each property calculation is submitted, executed, and post-processed via Run and PropertyPost OPs, respectively. Multiple types of property sub-workflows are executed concurrently and separately, which allows for independent result retrieval for property calculations that finished/converged first without waiting for the completion of the remaining time-consuming jobs (especially for DFT calculations). Overall, the “joint” workflow combines the “relaxation” and “property” into a cohesive, end-to-end process, streamlining the path from structural optimization to property calculations.

Seven types of alloy property are supported so far: equation of state (EOS), elastic property (Elastic), surface formation energy (Surface), interstitial formation energy (Interstitial), vacancy formation energy (Vacancy), generalized stacking fault energy (Gamma) and phonon spectra (Phonon). The example screenshot (right image) is for a completed “property” workflow for phonon spectra, equation of state (EOS) and nine other properties sub-workflows (hidden nodes) using LAMMPS29 from the Argo user interface.

Upon successful completion of each workflow, the resulting data are automatically transferred from the external repository to the local working directory. The data are systematically archived within each working directory in a JSON file format. APEX also has the capability to deposit these results directly into key-value NoSQL databases (e.g., MongoDB41 and DynamoDB41) through built-in database clients. The screenshot example on the right of Fig. 3 displays an example of a completed “property” workflow as visualized in the Argo UI. Each node within the UI represents an individual OP, offering users the ability to monitor the current status on the fly and locate errors, as well as review the input, output values, and files associated with each OP. In addition to automatic workflow execution, all OPs within APEX can be executed individually and locally in a stepwise manner via the do_step function of APEX. This function is particularly useful for testing and debugging, allowing for granular control and inspection of each step.

One advantage of APEX compared to conventional workflows is its independence of local computing environment, achieved through containerization. This greatly facilitates consistency across different computing platforms, eliminating the “it works on my machine” syndrome. APEX adopts reusable docker images to manage executable software packages with neither troublesome re-compiling of simulation tools nor preparation of dependencies each time they run in a new computing environment. Users can customize calculator images or use public image formats from DockerHub41, reducing the barrier for utilizing different compute resources and dependencies. Since each OP is deployed individually within isolated containers, users can easily switch or customize their running environment for Run OPs (e.g. calculator version) without affecting other OPs.

Features and extendability of APEX

Effective and user-friendly visualization of results is essential for rapid analysis of generated data from individual material property calculations. APEX offers a solution of an integrated data reporting dashboard, as depicted in Fig. 4a. This front-end aggregates all property calculation results and facilitates visualization with graphs. The dashboard functionality is developed using the open-source Dash41 framework in Python that enables straightforward web-based data application creation. The Graphical User Interface (GUI) has three functional areas:

-

1.

Selection Area: Positioned at the top of the GUI, this area contains user-interactive controls that enable selection of data dimensions for display through radio buttons and dropdown menus for initial configuration type and the property type specification respectively.

-

2.

Plot Area: Located in the center of the GUI, this section displays the corresponding result plots, dynamically generated using the Plotly module in Dash, that can be zoomed in/out and saved in PNG format. Users may combine results from multiple completed jobs and archived working directories in a single plot for cross-comparision.

-

3.

Data Tables: Situated at the bottom of the plot region, the data tables present the original results derived from post-processing. These tables are designed for user convenience (including clipboard buttons in the top-left corners for data copying) to facilitate original data acquiring for creation of customized plots or further data analysis.

The cloud-native APEX is designed to flexibly accommodate various computing scenarios. By adopting the DispatcherExecutor plugin within Dflow, APEX employs the virtual node to call DPDispatcher41 to submit jobs to local/remote HPC clusters or the cloud computation platform, which supports multiple schedulers (e.g., Slurm, PBS and LSF) and cloud services (e.g., Bohrium and Fujitsu41) to accommodate accessible computing resources. Figure 4b shows the UI of the APEX APP for submitting an APEX workflow with the assistance of the Bohrium cloud server41; the APEX Bohrium APP is a pure web-based solution independent of local environment configuration and package installation, providing multi-platform compatibility even for mobile devices. Users may submit automated APEX workflows in Bohrium through a browser on any device with internet access.

APEX is extendable to new types of properties and simulation tools implemented in an object-oriented manner. Application programming interfaces are designed for the abstract class of property and calculator by defining a set of method signatures to be implemented by specific functional class. The abstract property class regulates different methods to build structures and approaches to collect and analyze results after tasks are completed. APEX pre-defines methods to prepare relaxation/property calculation tasks, including specifying input files for different simulation tools and some static functions for conversion between common structural formats (e.g. “POSCAR” in VASP to “conf.lmp” in LAMMPS). This abstract method offers the convenience of extending and customizing new types of property calculations or simulation tools in APEX.

APEX application example I: properties of titanium

To demonstrate the capability and efficiency of APEX in evaluating the performance of various interatomic potentials and generating large datasets, we benchmark six titanium interatomic potentials across a set of basic material properties. These six potentials comprise two typical empirical potentials: an embedded atom method (EAM) and modified EAM (MEAM) potentials44,45, two MLPs: a deep potential (DP) and rapid artificial neural network (RANN) potential12,46, as well as two recent large pre-trained foundation models: DPA-1-OC2M and MACE-MP-018,47; in the following, we refer to these as EAM, MEAM, DP, RANN, DPA-1, and MACE-MP-0, respectively. The results presented here are derived directly from the APEX workflow and all plots are direct screenshots from the APEX results visualization dashboard. The equation of states (EOS) and elastic properties of perfect HCP, FCC, and BCC titanium crystals were explored via MD, while defect properties and phonon spectra were explored only for HCP structure; for each MD calculation, corresponding potential files, global configuration and indication JSON file are prepared within individual working directories. The initial atomic configurations of HCP, FCC, and BCC were provided in sub-directories before starting the workflows. We also use APEX to determine properties using a DFT calculator (VASP) to serve as a benchmark (the DFT calculation settings are listed in Methods). Generally, in the Ti case, all of the above properties can be calculated (for a particular interatomic potential) in APEX with LAMMPS within ~ 20 minutes (excluding RANN and MACE, which require longer time due to the absence of GPU acceleration support) with all tasks running in parallel on 60 Nvidia T4 GPU cards and a 16-core CPU.

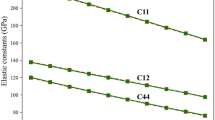

The zero temperature results for the structure and elastic properties of these three structures are shown in Table 1 and in the radar (polar) plots in Fig. 5a–c; the results are consistent with previous literature12,44,45,46. Note that BCC titanium is unstable with the RANN and DPA-1 potentials; BCC relaxes to FCC at zero temperature using RANN (see Table 1 and Figs. 5, where the BCC and FCC data are identical), while BCC relaxes to a tetragonal structure using DPA-1. The EAM potential does not accurately capture the BCC elastic properties (as compared with the other potentials and DFT results). The DP and MEAM exhibit overall good agreement with DFT for the elastic properties of the three titanium structures. The two pre-trained foundation models are less accurate.

Figure 5d–f display the EOSs of HCP, FCC and BCC titanium (APEX explored the 0.7-1.3 equilibrium volume range); here, structure optimizations were conducted at fixed volume. Since the DP was trained based on DFT energy data12,15, the EOS curve for DP closely approximate that of DFT. The EOS curves should be smooth with respect to volume change, as observed in the DFT, DP, EAM, RANN, DPA-1 and MACE-MP-0 for all three structures, while the MEAM potential exhibits some irregularity at low density (associated with cut-offs in the potential).

Table 1 also presents defect formation energies in HCP titanium; i.e., four surfaces, eight self-interstitials, and one vacancy. We emphasize that APEX conducts full optimizations for all defect interstitial structures in HCP. Additional detail for the interstitials may be found in Fig. 8 in the Methods Section; we note that some interstitials relax into other interstitial configurations, as seen in Table 1 (this is potential-dependent - this suggests that users should verify if structural changes occur during relaxation). For example, almost all BC type self-interstitials in the table (except DPA-1) are unstable and relax to the lowest energy configuration, such as BO or BS. The MLPs (DP and RANN) generally yield results superior to that of the EAM and MEAM potentials for defect properties; most of the MLP results exhibiting errors within 10% of the DFT results. The classical potentials and pre-trained models demonstrate significant discrepancies compared to DFT results. One notable exception is that the vacancy formation energy in HCP is overestimated by 17% using DP, while the EAM, MEAM, and RANN Ev values are 30% lower, 6% higher and 9% higher than the DFT prediction, respectively. In general, the pre-trained models tend to provide unreasonable estimates of point defect formation energy in this (titanium) case.

Figure 5g–k display five generalized stacking fault energy (GSFE) curves (γ-lines) for various slip systems in HCP titanium: basal \(\{0001\}[0\bar{1}10]\), prism \(\{10\bar{1}0\}[\bar{2}110]/3\), pyramidal I narrow \(\{10\bar{1}1\}[\bar{2}110]/3\), pyramidal I wide \(\{10\bar{1}1\}[\bar{2}113]/3\), and pyramidal II \(\{11\bar{2}2\}[\bar{2}113]/3\) planes12. As commonly done in GSFE calculations, atomic relaxation in APEX is restricted to the direction perpendicular to the slip plane. APEX supports the concurrent calculations of different slip planes using various interatomic potentials/DFT, with all results collected and visualized for easy comparison. The results for DFT, DP, and MEAM obtained by APEX are in good agreement with results reported in previous studies12. Overall, MEAM, DP and RANN qualitatively reproduce the general profile of γ-lines more accurately than the others. However, the MEAM potential fails to accurately predict the stable stacking fault energy, resulting in a significantly lower value than the DFT result for the basal plane. Conversely, the two MLPs, DP and RANN, outperform classical EAM and MEAM potentials in yielding accurate stable and unstable stacking fault energies. The two pre-trained foundation models substantially underestimate the GSFE and produce unsmooth prediction results on some planes (Basal and Pyramidal I narrow planes).

The phonon spectra of HCP Ti are shown in Fig. 5l along the k-point path: Γ → K → M → Γ → Δ. DFT calculations are conducted in APEX using the finite displacement method48 with a 3 × 3 × 2 HCP supercell, in agreement with previous calculations49. In the interatomic potential MD calculations, APEX was instructed to use a 6 × 6 × 6 supercell (to avoid size effects). The phonon spectra obtained by RANN, DPA-1 and MACE-MP-0 exhibit nonphysical imaginary frequencies across a broad range of k-space (not shown in Fig. 5l). The results depicted in the figure suggest that all potentials (excluding RANN, DPA-1, and MACE-MP-0) can qualitatively reproduce the general form of the phonon spectra. In the low-frequency region, DP is more accurate than other methods, while no potential yields accurate results in the high-frequency region (as compared with the DFT results).

a–c Elastic constants (Cij) and isotropic moduli (Poisson ratio nuV and bulk BV, shear GV, Young’s EV moduli - see Methods) of HCP, FCC, and BCC titanium. d–f Equations of state of HCP, FCC, and BCC titanium. (Note that different potentials employ different data in their training sets leading to some discrepancies as compared with DFT here.) g–k Generalized stacking fault energies for different slip systems in HCP titanium. l Phonon spectra of HCP titanium.

APEX application example II: high-throughput screening of elastic constants

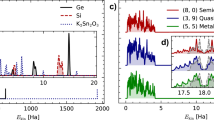

Here, we demonstrate the high-throughput calculation and task management capabilities of APEX using another example of simultaneous evaluation of the elastic constants of a set of alloy structures. These results are compared with ab initio calculations performed using ABACUS27. We adopt two pre-trained foundation models, DPA-1 and MACE-MP-0, to explore the elastic properties of a total of 179 stable crystal structures, including 39 single-element, 76 binary, and 64 ternary alloy compounds. All initial structures are from the Materials Project database.

Figure 6 illustrates the complete workflow used to compute the elastic constants using DPA-1 for 179 initial structures. The left side of Fig. 6 outlines the relaxation workflow. The 179 LAMMPS energy minimization tasks are divided into 45 task groups, each containing 4 sequential tasks. These tasks are distributed across 45 NVIDIA P100 nodes and executed in parallel. In this example, the relaxation workflow takes ~ 11 min to complete. Following the relaxations, the workflow transitions to the elastic property calculation phase, shown on the right side of Fig. 6. There are 179 elastic sub-workflows (each in an independent container), each of which involves the relaxation of 24 strained structures to calculate the elastic constants. These 24 strained structure relaxations are divided into 6 parallel tasks, distributed to 50 NVIDIA P100 nodes. The elastic constants are automatically retrieved to the local workspace upon the completion of each sub-workflow. The entire joint workflow (for all 179 structures), including both relaxation and elastic property calculations, requires ~ 44 minutes and no manual intervention.

The performance of both foundation models is evaluated by comparing the predicted elastic constants: C11, C12, C13, C22, C23, C33, C44, C55, C66. The accuracy of these, compared with first-principle references, is quantified by two metrics. The first is the standardized root mean square error

where ci and Ci represent the ith elastic constant predicted by the foundation model and DFT, respectively. σRMS is the deviation of the prediction from DFT, normalized the average elastic constants (to mitigate bias from variations in the magnitudes of the elastic constants across materials). The second metric is the Pearson correlation coefficient r, which assesses the similarity in the overall profile of the predicted elastic constants comparing to DFT predictions:

where \(\bar{c}\) and \(\bar{C}\) are the average values of the foundation model and DFT predictions.

Figure 7 presents scatter plots and density distribution curves for both evaluation metrics across 179 materials. In the scatter plot, the horizontal-axis is − σRMS, implying that data points further to the right correspond to lower error (thus better predictive performance). The vertical-axis is the correlation coefficient r, where higher values signify a stronger positive correlation between the predicted results and DFT data. The scatter plot reveals a clear overall relationship between the two factors: data points closer to the upper right corner represent systems where predictions closely align with DFT results. From the respective density curves, it appears that the MACE-MP-0 model outperforms DPA-1, achieving a lower average σRMS. However, DPA-1 shows a slightly larger density of high correlation scores r compared to MACE-MP-0.

Discussion

This study introduces APEX, a user-friendly Python framework for the automated, high-throughput evaluation of alloy properties using atomistic simulation methods, including DFT and MD. To demonstrate its capabilities, we conducted two representative case studies. In the first case, we evaluated a range of interatomic potentials for titanium. The results indicate that the neural network-based potentials generally outperform empirical ones, particularly in calculating defect properties such as surface energy, point defect energy, and generalized stacking fault energy. However, the ML foundation models – pre-trained to describe a wide-range of elements (and interactions between them) – performed notably worse in predicting material properties as compared with specialized (classical or ML-based) potentials. The second case involved high-throughput screening of elastic constants for 179 alloy structures. This analysis showed notable variability in the predictive capability of two foundation models across different alloy systems, underscoring the necessity of downstream fine-tuning to enhance their utility in specific materials applications.

These examples underscore the efficiency and robustness of APEX in automating key aspects of atomistic simulations, including DFT/MD job preparation, scalable task submission, post-processing, and visualization. Furthermore, the framework’s ability to handle large workloads on modern computing platforms highlights its potential as a critical tool for advancing high-throughput materials property exploration. APEX can thus be applied in high-throughput MD calculations and material property datasets generation leveraging ML models2,17,18,19 (provided that the DFT/MD calculators have an interface to these models). APEX has the potential for rapid evaluation and fine-tuning of ML models for properties of interest. For example, if the goal is to fine-tune a foundation model for studying dislocation properties, APEX can assist in testing the γ-lines properties within a few seconds. Then, the regions along the γ-line regions where the foundation model is insufficient (compared to DFT) can be identified and the corresponding DFT results are incorporated into new training datasets (e.g., in the format of energies, forces, and/or virial tensor).

The APEX package is open-source, to encourage widespread use and further development for researchers worldwide. The manual and hands-on examples in the Supplementary Information lower learning barriers for researchers in computational materials science, as well as introducing a new pathway for materials science education. The web-based Bohrium APP lowers the barrier for APEX adoption for atomistic simulations (with well-designed defaults) for all material scientists without the need to learn terminal commands. The containerization techniques incorporated in APEX embrace the state-of-the-art cloud resources, further facilitating interdisciplinary collaboration within AI4M.

APEX is extendable and continuously evolving; soon to be released developments will support an even wider set of additional defect and finite-temperature properties, as well as integration with additional DFT and MD software packages. The automated, robust, extendable, cloud-native framework allows APEX to continue to grow into a universal platform featuring diverse workflows for material property calculations. It has the potential to serve as a leaderboard engine for comparing various models for a wide-range of material properties (including defects), as well as an engine for fine-tuning the next generation interatomic potentials based upon foundation models. Although the pre-built property calculation routines in APEX today are most appropriate for (3D) crystalline, metallic alloys, the current APEX platform is, in principle, material-agnostic. APEX is designed to be readily extendable to properties of interest for other classes of crystalline materials, such as two-dimensional materials, ceramics, or organic molecular crystals. These extensions can be achieved by customizing Python functions that inherit from predefined abstract classes (e.g., Property, Calculator), enabling the integration of new property routines and calculation engines. As APEX expands in size and functionality, managing its complexity and scalability may become a challenge. One effective strategy could be to decouple extendable functions into standalone plugins that users can selectively install. This modular approach would simplify maintenance and allow users to adapt APEX for their specific needs. Additionally, it is also worth considering branching out from APEX into specialized sub-platforms tailored for different classes of materials. This approach could enhance both user experience and system robustness by providing features optimized for each material category. APEX facilitates collaborative efforts of a broad open-source community that supports its growth into a universal platform capable of addressing a wide range of material systems and property predictions to enhance applicability across the materials community.

Methods

Material property calculations in APEX

APEX currently supports the calculation of seven classes of materials properties: equation of state (EOS) and cohesive energy, elastic constants and moduli, surface formation energy, interstitial formation energy, vacancy formation energy, generalized stacking fault energies (γ-line), and phonon spectra.

Equilibrium state

Before calculating material properties, determining the equilibrium state of a given structure is essential for subsequent property calculations. In the “relaxation” workflow, APEX first relaxes the periodic structure using a conjugate gradient approach and records the total energy, atomic forces, box size, atom coordinates, stress and virial tensors for each frame. The information is stored in JSON format for easy access in the property workflow.

EOS and cohesive energy curve

The EOS/cohesive energy are critical functions characterizing the relationship between pressure, volume, and energy of materials under varying conditions. These calculations provide insights into fundamental mechanical properties. These calculations play a useful analysis of the performance and smoothness of interatomic potential energy surfaces.

In APEX, this function is implemented by conducting volume-fixed optimizations on a series of structures generated by uniformly scaling cell volume or lattice parameters. Users can specify the scaling range and testing increment. Upon completion of all (independent) tasks, the results are automatically extracted and stored.

Elastic properties

Elastic constants and moduli characterize material response to stress/strain within the elastic regime. This information is a major determinate for a wide range of materials performance properties for different applications.

The calculation of elastic constants involves a linear least-squares fit between stress and strain for a set of small deformations of the crystal lattice50, as described by the (tensor) Hooke’s law:

where σij and ϵkl are the stress and strain tensors. Cijkl and Sijkl are the fourth-rank elastic stiffness and compliance tensor which (based on simple symmetry considerations) can be written in the classic two-index Voigt notation as 6 × 6 Cij and Sij matrices. For many engineering applications, it is convenient to summarize the elastic constants in terms of isotropic elastic bulk (B) and shear (G) modulus as a function of the elastic constants:

where subscripts v, r and vrh represent Voigt51, Reuss52 and Voigt-Reuss-Hill53 approximation schemes, respectively. Additionally, the isotropic Young’s modulus (E) and Poisson ratio (ν) are derived from B and G as

In APEX, elastic property calculations are performed using simulations with a set of slightly deformed structures derived from the equilibrium state through six distortion matrices. The deformation magnitude can be adjusted via user input. DFT/MD optimizations with fixed-box constraints are performed on these structures to obtain the respective stress tensors. In the post-processing stage, the (Voigt notation) elastic constants and elastic moduli within one of the pre-defined approximation (Voigt, Reuss, or Voigt-Reuss-Hill) schemes are calculated and recorded in the final results. The structure creation and elastic constants fitting are facilitated by an elasticity module in Pymatgen33.

Surface formation energy

Surface energy is an important input for various material properties and phenomenons, such as wetting, adhesion, friction, catalytic activity and crack propagation.

In APEX, surface structures are generated using the surface module in Pymatgen33, which searches for all non-equivalent slabs with a maximum Miller index up to prescribed input values. The resulting slabs are then enlarged into supercells of user-specified dimensions. Vacuum layers (of user-specified size) are added along the direction perpendicular to the surface to create free surfaces.

APEX calculates the energy for all slabs and the relaxed surface energy σ can be obtained by:

where Etotal is the total energy of the relaxed slab structure containing N atoms, A is the surface area, and ε is the energy per atom for the equilibrium bulk structure.

Point defect formation energy

Points defects, including interstitials and vacancies, affect a wide range of materials properties and are central to many transport phenomena. An interstitial is formed by inserting additional atom(s) into the perfect lattice; a vacancy represents the removal of an atom from the crystal lattice.

APEX uses the pymatgen-analysis-defects package within Pymatgen to construct initial defect configurations. By inserting an atom into the perfect supercell lattice, APEX generates an interstitial supercell. This process is based on the Voronoi tessellation diagram, which automatically determines a series of reasonable sites to circumvent convergence issues. For FCC, BCC and HCP structures, APEX automatically produces several types of conventional initial interstitial configurations for comparative stability studies, as listed in Fig. 8. APEX creates vacancies by removing one periodically equivalent site.

The point defect formation energy Epoint is calculated as:

where Etotal is the total energy of the relaxed N atom structure with a point defect and ε denotes the energy per atom in the perfect, equilibrium lattice. It is important to note that some unstable initial interstitial configurations may relax to other metastable or stable structures after full optimization. Users should verify the fully-optimized structure to determine whether the initial and final interstitial structure differ.

Generalized stacking fault energy line (γ-line)

The generalized stacking fault energy (GSFE) curve, also known as the γ-line54, measures energy as a function of crystal translation across a specified plane in a particular direction. This curve provides insights into the energy barriers that must be overcome for dislocation slip. The saddle point in the GSFE curve may be associated with the critical resolved shear stress required to move dislocations55. Such information is critical for understanding dislocation mobility, which in turn affects the yield strength and ductility of materials.

In the first stage of the γ-line calculation, an initial slab structure with a specific Miller index is built using the slab generator of the surface module in Pymatgen33. This slab, a primitive cell containing the fewest atoms, is first expanded into a supercell by replicating along the x, y, and z periodic directions. Vacuum layers are then added to both sides of the slab along the z-axis. The plane of interest is located in the middle of the slab and is parallel to the slab surface. Atoms above this plane are uniformly shifted along a predetermined crystallographic direction across the x − y plane, while the atoms below remain stationary. This process generates a series of displaced structures for further energy calculations.

Users can tailor this process by setting parameters including the slab Miller index, slip direction, vacuum spacing, total slip distance, and the increments for each step. Additionally, users can impose specific constraints on atomic positions to calculate either relaxed or unrelaxed stacking fault energies. The location of the slip plane can also be customized to accommodate multiple potential slip planes that may exist in certain slab configurations12.

In the post processing, the GSFE energy EGSFE curve is obtained by:

where \(\bar{d}\) is the shear distance, \({E}_{{\rm{total}}}(N,\bar{d})\) is the total energy of the corresponding slab structure with N atoms and plane area A, and ε denotes the energy per atom in the equilibrium bulk lattice.

Phonon spectra

Phonon spectra describe the relationship between the phonon frequency (or energy) and their wave vector within a crystalline material. This spectra aid in understanding various physical properties of materials, such as thermal and electrical conductivity, elastic properties, and specific heat56.

APEX implements phonon calculations based on Phonopy57 for DFT calculations in VASP and ABACUS. By default, APEX employs the linear response method based on density perturbation functional theory58 to calculate the phonon spectra in DFT. Users can also switch to the direct finite displacement method48 through calculation settings. Additionally, PhononLAMMPS59 is adopted for the interface between LAMMPS and Phonopy to compute phonon harmonic force constants via MD simulations. For a specific input configuration, the SeeK-path package60 is used after a crystal symmetry search61, and APEX automatically adopts the suggested band path for phonon computation unless otherwise specified by the user. In the post-process stage, the output from Phonopy is collected and converted to the JSON format for convenience.

DFT calculation settings for the titanium case study

The DFT calculations are preformed using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof62 generalized gradient approximation exchange-correlation functional with a plane-wave cutoff energy of 650 eV. The projector-augmented-wave method63 is employed to treat core and valence electrons. K-point sampling is implemented using the Monkhorst-Pack scheme64, with a grid spacing of 0.1 Å−1. The convergence criteria for electronic minimization are set to be 10−3 meV between steps, while the residual force convergence criterion for ionic relaxation is set to 0.01 eV/Å.

Data availability

The data generated in this work is available at https://github.com/ZLI-afk/static/tree/main/docs/apex_Ti_test/data, including various property calculation results for the titanium case using six interatomic potentials and DFT.

Code availability

The APEX package is open-source and may be accessed at https://github.com/deepmodeling/APEX.

References

Wang, H. et al. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature 620, 47 (2023).

Merchant, A. et al. Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature 624, 80 (2023).

Vu, T.-S. et al. Towards understanding structure–property relations in materials with interpretable deep learning. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 215 (2023).

Raabe, D., Mianroodi, J. R. & Neugebauer, J. Accelerating the design of compositionally complex materials via physics-informed artificial intelligence. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 873 (2023).

Deng, J. et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database, in 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition pp. 248–255 (IEEE, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848.

Gorsse, S., Nguyen, M., Senkov, O. & Miracle, D. Database on the mechanical properties of high entropy alloys and complex concentrated alloys. Data Brief. 21, 2664 (2018).

Xu, P., Ji, X., Li, M. & Lu, W. Small data machine learning in materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 42 (2023).

Wu, C.-T. et al. Machine learning recommends affordable new ti alloy with bone-like modulus. Mater. Today 34, 41 (2020).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Curtarolo, S. et al. Aflow: An automatic framework for high-throughput materials discovery. Comput. Mater. Sci. 58, 218 (2012).

Saal, J. E., Kirklin, S., Meredig, B. & Wolverton, C. Materials Design and Discovery with High-Throughput Density Functional Theory: The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD). JOM 65, 1501 (2013).

Wen, T. et al. Specialising neural network potentials for accurate properties and application to the mechanical response of titanium. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 206 (2021).

Xie, Y. et al. Uncertainty-aware molecular dynamics from Bayesian active learning for phase transformations and thermal transport in SiC. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 36 (2023).

Qi, J. et al. Bridging the gap between simulated and experimental ionic conductivities in lithium superionic conductors. Mater. Today Phys. 21, 100463 (2021).

Wen, T., Zhang, L., Wang, H., E, W. & Srolovitz, D. J. Deep potentials for materials science. Mater. Futures 1, 022601 (2022).

Zuo, Y. et al. Performance and cost assessment of machine learning interatomic potentials. J. Phys. Chem. A 124, 731 (2020).

Chen, C. & Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 718 (2022).

Batatia, I. et al. A foundation model for atomistic materials chemistry https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.00096 (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. DPA-2: a large atomic model as a multi-task learner. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 293 (2024).

Deng, B. et al. CHGNet as a pretrained universal neural network potential for charge-informed atomistic modelling. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 1031 (2023).

Takamoto, S., Okanohara, D., Li, Q.-J. & Li, J. Towards universal neural network interatomic potential. J. Materiomics 9, 447 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Generative learning facilitated discovery of high-entropy ceramic dielectrics for capacitive energy storage. Nat. Commun. 15, 4940 (2024).

Weiss, T. et al. Guided diffusion for inverse molecular design. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 873 (2023).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Gonze, X. et al. The Abinit project: Impact, environment and recent developments. Computer Phys. Commun. 248, 107042 (2020).

Chen, M., Guo, G.-C. & He, L. Systematically improvable optimized atomic basis sets for ab initio calculations. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, 445501 (2010).

Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package - Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Computer Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Berendsen, H., Spoel, D. V. D. & Drunen, R. V. GROMACS: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Computer Phys. Commun. 91, 43 (1995).

Phillips, J. C. et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 044130 (2020).

Brooks, B. R. et al. CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 1545 (2009).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): A robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Computational Mater. Sci. 68, 314 (2013).

Hirel, P. Atomsk: A tool for manipulating and converting atomic data files. Computer Phys. Commun. 197, 212 (2015).

Hale, L. M., Trautt, Z. T. & Becker, C. A. Evaluating variability with atomistic simulations: the effect of potential and calculation methodology on the modeling of lattice and elastic constants. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 26, 055003 (2018).

Wang, V., Xu, N., Liu, J.-C., Tang, G. & Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: A user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Computer Phys. Commun. 267, 108033 (2021).

Larsen, A. H. et al. The atomic simulation environment-a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Janssen, J. et al. pyiron: An integrated development environment for computational materials science. Comput. Mater. Sci. 163, 24 (2019).

Choudhary, K. et al. The joint automated repository for various integrated simulations (JARVIS) for data-driven materials design. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 173 (2020).

Goyal, A., Gorai, P., Peng, H., Lany, S. & Stevanović, V. A computational framework for automation of point defect calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 130, 1 (2017).

Bohrium platform: https://bohrium.dp.tech/en-US; Dflow: https://github.com/deepmodeling/dflow; Argo: https://argoproj.github.io; Docker: https://www.docker.com; Kubernetes: https://kubernetes.io; MongoDB: https://www.mongodb.com; DynamoDB: https://aws.amazon.com/dynamodb; Dash: https://dash.plotly.com; DPDispatcher: https://github.com/deepmodeling/dpdispatcher; Fujitsu platform: https://www.fujitsu.com/global; Dockerhub: https://hub.docker.com; APEX Web APP: https://bohrium.dp.tech/apps/apex/; iprPy: https://github.com/lmhale99/iprPy (all accessed on April 26, 2024)

Dang, K., Chen, J., Rodgers, B. & Fensin, S. LAVA 1.0: A general-purpose python toolkit for calculation of material properties with LAMMPS and VASP. Computer Phys. Commun. 286, 108667 (2023).

X., Liu et al. Dflow, a python framework for constructing cloud-native ai-for-science workflows https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.18392 (2024)

Ackland, G. J. Theoretical study of titanium surfaces and defects with a new many-body potential. Philos. Mag. A 66, 917 (1992).

Hennig, R. G., Lenosky, T. J., Trinkle, D. R., Rudin, S. P. & Wilkins, J. W. Classical potential describes martensitic phase transformations between the α, β, and ω titanium phases. Phys. Rev. B 78, 054121 (2008).

Nitol, M. S., Dickel, D. E. & Barrett, C. D. Machine learning models for predictive materials science from fundamental physics: An application to titanium and zirconium. Acta Materialia 224, 117347 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. Pretraining of attention-based deep learning potential model for molecular simulation. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 94 (2024).

Kresse, G., Furthmüller, J. & Hafner, J. Ab initio Force Constant Approach to Phonon Dispersion Relations of Diamond and Graphite. EPL (Europhys. Lett.) 32, 729 (1995).

Souvatzis, P., Eriksson, O. & Katsnelson, M. I. Anomalous Thermal Expansion in α-Titanium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 015901 (2007).

Page, Y. L. & Saxe, P. Symmetry-general least-squares extraction of elastic data for strained materials from ab initio calculations of stress. Phys. Rev. B 65, 104104 (2002).

Voigt, W. Lehrbuch der kristallphysik, bb teubner, leipzig, 1928; b) a. reuss. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 9, 49 (1929).

Reuss, A. Calculation of the flow limits of mixed crystals on the basis of the plasticity of monocrystals. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 9, 49 (1929).

Hill, R. The Elastic Behaviour of a Crystalline Aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. A 65, 349 (1952).

Christian, J. W. & Vítek, V. Dislocations and stacking faults. Rep. Prog. Phys. 33, 307 (1970).

Peierls, R. The size of a dislocation. Proc. Phys. Soc. 52, 34 (1940).

Grimvall, G., Magyari-Köpe, B., Ozoliņš, V. & Persson, K. A. Lattice instabilities in metallic elements. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 945 (2012).

Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tadano, T. & Tanaka, I. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 35, 353001 (2023).

Gonze, X. & Lee, C. Dynamical matrices, Born effective charges, dielectric permittivity tensors, and interatomic force constants from density-functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10355 (1997).

Carreras, A., phonoLAMMPS: A python interface for LAMMPS phonon calculations using phonopy (2021).

Hinuma, Y., Pizzi, G., Kumagai, Y., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. Band structure diagram paths based on crystallography. Computational Mater. Sci. 128, 140 (2017).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. Spglib: a software library for crystal symmetry search https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.01590 (2018).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

Acknowledgements

This work (Z.L., A.S.L.S.P., X.G., B.Y., D.J.S.) is supported by the Research Grants Council, Hong Kong SAR through the General Research Fund (17210723, 17200424). T.W. acknowledges the support of The University of Hong Kong via seed fund (2201100392). The work of Han Wang is supported by the National Key R& D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1004300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12122103). The Authors would like to thank for startup funding from Materials Innovation Institute for Life Sciences and Energy (MILES), HKU-SIRI in Shenzhen for support of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., T.W., and X.L. developed the APEX package. Z.L., T.W., Y.Z., X.L., C.Z., and H.W. performed the research and analyzed the data. T.W., Y.Z., H.W., L.Z., D.J.S. conceived and supervised the project. Z.L., T.W., Y.Z., and D.J.S. drafted the manuscript, and all authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Wen, T., Zhang, Y. et al. APEX: an automated cloud-native material property explorer. npj Comput Mater 11, 88 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01580-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01580-y

This article is cited by

-

An automated framework for exploring and learning potential-energy surfaces

Nature Communications (2025)