Abstract

Understanding the optical properties of color centers in silicon carbide is essential for their use in quantum technologies, such as single-photon emission and spin-based qubits. In this work, first-principles calculations were employed using the r2SCAN density functional to investigate the electronic and vibrational properties of neutral divacancy configurations in 4H-SiC. Our approach addresses the dynamical Jahn–Teller effect in the excited states of axial divacancies. By explicitly solving the multimode dynamical Jahn–Teller problem, we compute emission and absorption lineshapes for axial divacancy configurations, providing insights into the complex interplay between electronic and vibrational degrees of freedom. The results show strong alignment with experimental data, underscoring the predictive power of the methodologies. Our calculations predict spontaneous symmetry breaking due to the pseudo Jahn–Teller effect in the excited state of the kh divacancy, accompanied by the lowest electron–phonon coupling among the four configurations and distinct polarizability. These unique properties facilitate its selective excitation, setting it apart from other divacancy configurations, and highlight its potential utility in quantum technology applications. These findings underscore the critical role of electron–phonon interactions and optical properties in spin defects with pronounced Jahn–Teller effects, offering valuable insights for the design and integration of quantum emitters for quantum technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Silicon carbide (SiC) is a wide band gap material with great potential for high-power and high-frequency electronic devices1 and quantum technologies (QT). Deep-level defects in the SiC crystal structure can significantly affect carrier mobility and lifetime, negatively impacting the performance of power devices2,3,4. While not all deep-level defects are optically active, some can introduce discrete energy levels deep within the band gap that can be optically addressed. At sufficiently low densities, such color centers can serve as sources of non-classical light5. Furthermore, some states reveal a paramagnetic spin structure with long coherence times even at room temperature (RT), and may therefore be optically accessible for spin initialization and readout protocols6. These properties position solid-state color centers as promising candidates for single-photon emitters (SPEs) and spin qubits. When integrated with advanced material processing and fabrication capabilities, color centers in SiC emerge as a robust platform for future solid-state quantum technologies7,8.

SiC hosts a variety of defects with QT-compatible properties9,10,11. Key intrinsic defects such as the silicon vacancy (VSi), divacancy (VSiVC), and carbon antisite-vacancy pair (CSiVC) are introduced by irradiation and annealing and are proven to be photostable SPEs at RT12,13,14. CSiVC emits in the visible spectrum (640–680 nm), VSi in the near-infrared (858–916 nm)12,13, whereas the divacancy exhibits zero-phonon line (ZPL) energies closer to the telecommunications band at 1040–1140 nm14,15. A deterministic single-photon emission in the infrared, such as that from the divacancy, is essential for fiber optic technology, enabling low-loss, secure long-distance quantum communication and cryptography. Furthermore, the divacancy’s electron spins show outstanding longevity, with coherence times exceeding those of nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond, with VSiVC exhibiting T2 > 5 s16. Thus, the divacancy stands out as a versatile candidate for QT applications, functioning as both an SPE and a spin qubit.

Although color centers in crystals offer numerous advantages as SPEs and qubits, including RT operation, photostability, and scalability, the solid-state matrix also presents several challenges. These include both inhomogeneous and homogeneous optical broadening effects. Inhomogeneous broadening can be mitigated by improving the material quality. However, homogeneous broadening, which results from interactions with the continuum of vibrational degrees of freedom in solids, is more challenging to control. Such electron–phonon interactions not only lead to the emergence of phonon sidebands that reduce the number of photons emitted at the ZPL but also contribute to its temperature broadening, thereby diminishing the photon indistinguishability properties of the emitter. Furthermore, spin–phonon coupling plays a crucial role in determining the coherence properties of spin systems, as well as in driving the mechanisms that lead to intersystem crossing, which are essential for spin initialization and optical-spin contrast in optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) experiments. The theoretical description of the vibrational structure and electron–phonon coupling mechanisms of deep-level defects poses significant challenges, as defects exhibit characteristics of both atomic and solid-state physics, necessitating advanced methodologies that extend beyond conventional ab initio calculations17,18.

Advancements in understanding crystal defects as potential quantum systems have stimulated a renewed focus on the Jahn–Teller (JT) effect in color centers19,20,21,22,23,24,25. This effect emerges when degenerate or near-degenerate electronic states interact with symmetry-breaking vibrational modes. This coupling intricately mixes the electronic and vibrational degrees of freedom, giving rise to complex dynamics that influence the system’s electronic and optical properties26,27,28. Specifically, the JT interaction induces unique vibronic states, distinct from their adiabatic counterparts, manifesting as characteristic features in the absorption and emission spectra. These effects underscore the pivotal role of electron–phonon coupling in shaping the optical signatures of these systems. The description of JT systems typically employs a phenomenological model, approximating the numerous JT active modes with a single effective degenerate mode19,20,22,27. However, accurately capturing optical signatures often necessitates solving the multi-mode JT problem, as recently demonstrated in modeling optical spectra for the negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy18 and nickel-vacancy29 centers in diamond.

In this work, first-principles calculations were performed utilizing the recently developed r2SCAN density functional30 to investigate the electronic and vibrational properties of the four distinct configurations of the neutral divacancy in the 4H polytype of SiC. Previous theoretical works31,32 modeled emission lineshapes for different divacancy configurations but did not explicitly solve the multimode dynamic JT (DJT) problem present in the excited state of axial divacancies or calculate absorption lineshapes. This work addresses these gaps by providing calculated emission and absorption lineshapes for all four divacancy configurations and explicitly treating the multimode DJT problem for axial divacancies, which exhibit a pronounced DJT effect. The dynamical coupling between electronic and vibrational degrees of freedom can create distinct vibronic states, resulting in specific emission or absorption spectra features. Herein, we demonstrate that this must be considered to correctly capture the optical properties of the divacancy in 4H-SiC and discuss the implications of these findings for other systems.

Results

Electronic structure

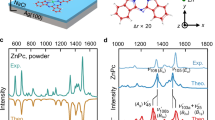

Divacancies in the neutral charge state were studied by performing calculations within the spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) framework and using the r2SCAN meta-GGA functional30. In the 4H-SiC polytype, each atomic site can take on either a hexagonal (h) or pseudo-cubic (k) configuration. Thus, four distinct defect configurations must be considered for a binary complex, such as the silicon–carbon divacancy that can take on different symmetries and exhibit different electro-optical properties (see Fig. 1).

Ball and stick representation of vacancy pairs depicted as hollow spheres. The carbon and silicon atoms are represented by brown and blue spheres, respectively. Four nonequivalent configurations (hh, kk, hk, kh) of divacancy defects are shown. The planes labeled h and k indicate the symmetry of lattice sites.

The electronic structure of neutral divacancies in 4H-SiC can be described using three molecular orbitals derived from the carbon dangling bonds, as depicted in Fig. 2c, d. Axial divacancies, hh-VV0 and kk-VV0, which exhibit C3v point-group symmetry (see Fig. 2a, b), consist of an orbital of the a1 irreducible representation and a doublet of orbitals with e-symmetry (see Fig. 2c). DFT calculations reveal an additional orbital doublet of e-symmetry within the band gap close to the conduction band edge, originating from silicon dangling bonds; these orbitals, however, remain optically inactive under standard excitation conditions. The ground state is a spin-triplet with A2 orbital symmetry, designated as 3A2 for axial divacancies, and is characterized by the orbital configuration \({a}_{1}^{2}{e}^{2}\). This state maintains a single-determinant wave function \(| {a}_{1}{\bar{a}}_{1}{e}_{x}{e}_{y}|\) for the spin projection ms = 1. The transition of a spin-down electron from the a1 an e orbital located on carbon, leads to the excited spin-triplet state 3E which is characterized by a degenerate orbital configuration a1e3. For ms = 1, this electron configuration manifests as two single-determinant wave functions \(| {a}_{1}{e}_{x}{e}_{y}{\bar{e}}_{y}|\) and \(| {a}_{1}{\bar{e}}_{x}{e}_{x}{e}_{y}|\). The symmetry dictates that the dipole moment for the transition 3A2 ↔ 3E in 4H-SiC is polarized within the c-plane.

a Ball and stick representation of the kk-VV0 defect in 4H-SiC. b Top-down view of kk-VV0 along the c-axis showcasing the C3v symmetry of the defect. c Schematic representation of single-particle defect levels in the band gap of 4H-SiC showing the occupancy of these levels in the ground 3A2 state and excited 3E state of kk-VV0. d Isosurfaces of the real part of the single-particle orbitals associated with the defect levels \({\overline{a}}_{1}\), \({\overline{e}}_{x}\), and \({\overline{e}}_{y}\). The color (blue/red) represents the sign (±) of the orbital.

In contrast to axial divacancies, hk and kh divacancies exhibit reduced C1h point group symmetry in the ground state, impacting their electronic and optical properties. The hk divacancy displays three lowest-lying levels within the band gap, ordered from lowest to highest energy respectively as \({a}^{{\prime} }(1)\), a″, and \({a}^{{\prime} }(2)\), where \({a}^{{\prime} }\) and a″ denote irreducible representations of the C1h point group. DFT calculations predict that the ground state of the kh divacancy has orbital symmetries denoted as \({a}^{{\prime} }(1)\), \({a}^{{\prime} }(2)\), and a″ while the excited state of this divacancy has a reduced C1 symmetry with its orbitals all having a-symmetry. Illustrations of single-particle levels for each basal configuration are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. Using group-theoretical analysis based on the C1h point group, different polarization of the ZPL can be expected for hk and kh divacancies. In the hk divacancy, the optical transition occurs between the \({a}^{{\prime} }(1)\) and a″ levels, involving a change in parity from \({a}^{{\prime} }\) to a″. Consequently, the transition dipole moment (TDM) must transform according to the a″ irreducible representation. This symmetry implies that the polarization of the emitted or absorbed light will be oriented perpendicular to the mirror plane σh, resulting in a dipole moment polarized within the c-plane (similar to hh-VV0 and kk-VV0). For the kh divacancy, however, the optical transition occurs between the \({a}^{{\prime} }(1)\) and \({a}^{{\prime} }(2)\) levels. Since there is no change in parity, the polarization of the emitted or absorbed light is within the symmetry reflection plane of the defect, with most of its projection perpendicular to the c-plane (theoretical transition dipole matrix elements are provided in Supplementary Table 1). This analysis is consistent with previously reported experimental and theoretical findings33,34,35.

The calculated ZPL energies and zero-field splitting (ZFS) parameters for all divacancy configurations are compared with the experimental results and presented in Table 1. The results obtained using the r2SCAN functional are in excellent agreement with experimental data36 (see Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3 for a comparison of results obtained using the SCAN37 functional and other theoretical works). From the mean absolute errors, SCAN and r2SCAN functionals enhance the accuracy compared to other calculations and come closest to the experimental values while requiring only a fraction of the computational cost needed for hybrid functionals.

JT effect

The excited state 3E of the axial hh and kk divacancies is a degenerate orbital doublet with orbital configurations \({a}_{1}{e}_{x}^{1}{e}_{y}^{2}\) and \({a}_{1}{e}_{x}^{2}{e}_{y}^{1}\). This degeneracy results in an intricate non-adiabatic coupling between electronic E states and e-symmetry degenerate vibrational modes forming an E ⊗ (e ⊕ e ⋯ ) JT system. Since the coupling is not too strong, it leads to a DJT effect with dynamical distortions along symmetry-breaking directions, generating a distinct array of vibronic states and giving rise to specific features within optical spectra. The electronic structure of this DJT system is analogous to that of the negatively charged NV center in diamond, where the interplay between electronic and vibrational states due to the DJT effect has been well-studied18,19,20,38.

To analyze the adiabatic potential energy surface (APES) of the excited triplet state 3E, an effective single-degenerate-mode model for quadratic E ⊗ e vibronic coupling is used to measure the effective parameters describing a two-dimensional representation of a multi-dimensional potential energy surface28. The expression for the APES in the space of polar mass-weighted displacement coordinates Qx and Qy (where Qx and Qy describe a pair of effective coordinates that parametrize a collective ionic motion along the e-symmetry direction) takes the form

where \(\rho =\sqrt{({Q}_{x}^{2}+{Q}_{y}^{2})}\), \(\phi =\arctan ({Q}_{y}/{Q}_{x})\), κ is the elastic force constant, F is the linear vibronic constant, and G is the quadratic vibronic constant. The values of the three vibronic constants, mass-weighted displacements, and details of first-principles calculation of the APES are provided in Supplementary Note 4. The lower branch of the 3E APES takes a “tricorn sombrero” shape with three minima and three saddle points (see Fig. 3a). The three minima have a JT stabilization energy EJT of 69 meV for hh-VV0 and 64 meV for kk-VV0. These three minima are separated by energy barriers δJT of 23 meV for hh-VV0 and 19 meV for kk-VV0. These results are in good agreement with other theoretical studies, where the use of the hybrid HSE06 functional yielded JT stabilization energy and barrier values for the hh-VV0 defect of 74 meV and 18 meV, respectively39. Figure 3b shows the APES contour plot and the path used to calculate the potential energy curve (see Fig. 3c) and parametrize the JT relaxation. For the analysis of the multi-mode vibronic states of axial divacancy, including the quadratic JT effect would significantly increase the complexity of an already intricate problem. Therefore, we use linear JT theory to analyze the impact of the JT effect on vibronic dynamics and its influence on the optical properties of axial divacancies.

a APES of the lower branch of the 3E state, which takes a “tricorn sombrero” shape with three minima and three saddle points. Qx, Qy configuration coordinates represent the collective motion of effective e-symmetry modes. EJT is the JT stabilization energy, which is the difference in energy between the high-symmetry and distorted configurations. The three minima are separated by three barriers with the energy of δJT. b Contour plot of the APES. c Computed potential energy curve along the path defined in (b). The potential energy curve is fitted by Eq. (1) (see text).

For basal divacancies, the excited states exhibit non-degenerate energy levels that are closely spaced. ΔSCF calculations indicate that in the ground-state geometry, the energy separation between these excited states is 62 meV for the hk divacancy and 100 meV for the kh divacancy. This small distance suggests the potential presence of a pseudo-JT (PJT) effect, where symmetry-breaking vibrational modes of a″ symmetry couple to electronic states that are close in energy. In static adiabatic calculations, the PJT effect modifies the harmonic potential. For weak coupling, this manifests as changes in the effective frequency of PJT-active modes, while stronger coupling can lead to the appearance of double minima and symmetry breaking28. Our results reveal that the kh divacancy in the excited state undergoes symmetry breaking, providing additional stabilization energy of 15 meV. In contrast, no such symmetry breaking is observed for the hk divacancy, indicating weaker PJT coupling. A comprehensive analysis of the PJT effect necessitates the explicit determination of electron–phonon coupling parameters (〈ψi∣∂ψi/∂Qk〉) directly from the wave functions. In the case of pure degeneracy, these parameters can be inferred from the shape of the APES. However, such an analysis is beyond the scope of the present study. As a result, for the examination of the optical properties of basal divacancies, we neglect the non-adiabatic nature of the PJT effect and instead rely on the Huang–Rhys (HR) theory40. This approximation could be justified for the emission process18, where the final state can be effectively treated as adiabatic. Nonetheless, a more detailed investigation is necessary to rigorously address the absorption spectra, which is left for future work.

Vibrational properties

Vibrational structures of the ground and excited states and the subsequent relaxation profiles were calculated to obtain electron–phonon coupling densities for all four divacancy configurations. The embedding methodology of refs. 17,18 was employed to simulate these parameters in supercells containing nearly 30,000 atomic sites, approaching the dilute limit.

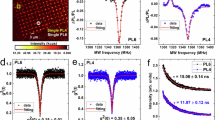

The calculated spectral densities of electron–phonon coupling for the emission (3E → 3A2) and absorption (3A2 → 3E) processes for the axial divacancies are presented in Fig. 4. The coupling to JT inactive (a1-symmetry) modes is represented by \({S}_{{a}_{1}}(\hslash \omega )={\sum }_{k}{S}_{k}\delta (\hslash \omega -\hslash {\omega }_{k})\) (see Fig. 4a, b), where Sk is the HR factor17,18,40 for vibrational mode k, quantifying the average number of a1-symmetry phonons emitted during an optical transition. The linear JT coupling spectral density for e-symmetry modes is given by \({K}^{2}(\hslash \omega )={\sum }_{k}{K}_{k}^{2}\delta (\hslash \omega -\hslash {\omega }_{k})\) (see Fig. 4c, d), where Kk is the dimensionless vibronic coupling constant18,29,41 quantifying the coupling between the e-symmetry vibrational doublet k and components of the degenerate electronic state E. The total HR factor Stot = ∑kSk and the total JT coupling \({K}_{{\rm{tot}}}^{2}={\sum }_{k}{K}_{k}^{2}\) are included in Fig. 4.

a Spectral densities \({S}_{{a}_{1}}(\hslash \omega )\) associated with a1-symmetry phonons of the 3E → 3A2 and b3A2 → 3E transitions. c Spectral densities of JT linear coupling K2(ℏω) associated with e-symmetry phonons of the 3E → 3A2 and d3A2 → 3E transitions. The spectral densities are for hh and kk divacancies. The total HR factor Stot and the total JT coupling \({K}_{{\rm{tot}}}^{2}\) are included in the panels. Results are for the (23 × 23 × 7) supercell with 29,622 atomic sites.

The parameters Sk and \({K}_{k}^{2}\) describe alterations in the APES and are directly related to relaxation energies. The relaxation energy along the symmetry-preserving direction following the vertical transition A → E is given by \(\Delta {E}_{{a}_{1}}={\sum }_{k}\hslash {\omega }_{k}{S}_{k}\). In contrast, the linear theory defines the JT stabilization energy as \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{JT}}}={\sum }_{k}\hslash {\omega }_{k}{K}_{k}^{2}\). Our computations yield \(\Delta {E}_{{a}_{1}}=74.2\) meV for hh-VV0 and 76.1 meV for kk-VV0. This suggests that the contribution to the electron–phonon coupling from JT-active modes (EJT = 69 meV for hh and 64 meV for kk) is comparable to that from symmetry-preserving modes.

During the 3E → 3A2 optical transition, the total HR factor of a1-symmetry modes is found to be equal for hh and kk divacancies, although the hh divacancy has a higher total JT coupling (K2 = 1.36) than the kk divacancy (K2 = 1.16). The main difference in the vibrational structures between emission and absorption processes lies in the contribution from e-symmetry phonons. The JT linear coupling K2(ℏω) for the absorption process is overall shifted to higher energy levels compared to the emission process, particularly for phonon energies above 100 meV. In the case of the 3A2 → 3E optical transition, the total calculated JT coupling of e-symmetry phonons is 1.52 (hh-VV0) and 1.30 (kk-VV0), respectively, which is several times stronger than that for the NV− center in diamond18. This warrants the use of multimode DJT theory to model the absorption lineshapes for the axial divacancies. During the emission process, degeneracy resides in the initial state, and therefore, HR theory can be utilized to calculate the emission lineshapes18. For a complete comparison, the DJT theory was still applied to calculate the spectral densities of JT linear coupling and subsequent luminescence lineshapes for axial divacancies.

The calculated spectral densities of electron–phonon coupling for both emission and absorption processes for basal divacancies are presented in Fig. 5. Each panel includes the total HR factor40, Stot = ∑kSk. Our findings indicate that the total electron–phonon coupling is noticeably stronger for hk divacancies (2.83 for emission and 3.11 for absorption) compared to kh divacancies (2.47 and 2.83, respectively), with the main difference lying in the spectral region around 35 meV.

a Spectral function S(ℏω) of the \({3\atop}{A}^{{\prime} }{\to}{3\atop}{A}^{{\prime} }\) and b\({3\atop}{A}^{{\prime} }{\to}{3\atop}{A}^{{\prime} }\) optical transitions for hk divacancy. c Spectral function S(ℏω) of the 3A → 3A and d3A″ → 3A″ optical transitions for kh divacancy. Results are for the (23 × 23 × 7) supercell with 29,622 atomic sites.

By comparing the spectral functions between the emission and absorption processes, a noticeable difference can be observed, which arises from changes in the vibrational structures of the ground and excited states. For axial divacancies, the main distinction lies in the vibrational structure of JT-active modes (see Fig. 4c, d), where a significant shift of electron–phonon coupling to higher vibrational frequencies is observed during absorption. A similar, but less pronounced, effect is observed for basal divacancies (Fig. 5). The electron–phonon coupling was calculated using the equal mode approximation, which assumes identical vibrational structures in both states. Although this assumption is not entirely accurate, for low-temperature spectra, a good approximation is to use the vibrational structure of the final state in the transition18. However, this change in vibrational structure indicates a quadratic electron–phonon coupling on top of the DJT effect, which we do not account for in the following analysis. This could have important implications for modeling temperature effects and temperature broadening of the ZPL in future works.

Optical spectra of emission

The 3E → 3A2 optical transition lineshapes calculated using HR theory and multimode DJT theory (in the case of axial divacancies) are presented in Fig. 6 and compared with the experimental lineshapes (in gray)31,42. The emission lineshapes calculated using both theories are in very good agreement with the experiment and capture all the spectral features. The similarity of the lineshapes obtained by both theories agrees with the findings of ref. 18, where it was shown that for an 3E → 3A2 optical transition and K2 ≈1, the HR theory provides a quantitatively similar description to the rigorous DJT theory. The main difference between the emission lineshapes calculated using HR and DJT theories lies in the intensity redistribution. The DJT approach yields a higher ZPL intensity and, subsequently, a higher Debye–Waller factor (DWF), defined as the ratio of the ZPL to the entire lineshape (see Table 2), with a sideband that is less extended compared to that predicted by HR theory.

Blue lines are luminescence lineshapes calculated using HR theory, while the orange lines are lineshapes calculated using DJT theory. The gray area represents experimental data from refs. 31,42. The small peak marked with a star ′\(*\)′ in the experimental curve for hk-VV0 is the ZPL of hh-VV0 and should be disregarded in the comparison between theory and experiment. The intensities of the experimental lineshapes have been scaled to match the peaks of the computed lineshapes. Results reported here are computed at the r2SCAN level of theory and extrapolated to the dilute limit, approximated by a (23 × 23 × 7) supercell with 29,622 atomic sites.

The hh, kk, and hk divacancies exhibit similar emission lineshape profiles and DWFs. In contrast, the kh divacancy shows significantly different characteristics when compared to the other divacancies. The computed mass-weighted displacements ΔQ (amu0.5 Å) between the equilibrium structures of the ground state and the excited state are as follows: 0.823 (hh), 0.802 (kk), 0.798 (hk), and 0.762 (kh). Moreover, the total electron–phonon coupling factors are 3.21 (hh), 3.01 (kk), 2.83 (hk), and 2.47 (kh). The noticeably lower mass-weighted displacement and total electron–phonon coupling for the kh divacancy lead to its more prominent DWF. These distinctions underscore the unique vibrational characteristics of the kh configuration along with different polarization properties, setting it apart from the hh, kk, and hk configurations.

Optical spectra of absorption

The absorption lineshapes for the 3A2 → 3E optical transition, calculated using both HR and multimode DJT theories for axial divacancies, are displayed in Fig. 7. Additionally, the absorption lineshapes for the \({3\atop}{A}^{{\prime} }{\to }{3\atop}{A}^{{\prime} }\) transition in the hk divacancy and the 3A″ → 3A″ transition in the kh divacancy, calculated with HR theory, are presented in the same figure.

Blue lines are absorption lineshapes calculated using HR theory, while the orange lines are absorption lineshapes calculated using DJT theory. Results reported here are computed at the r2SCAN level of theory and extrapolated to the dilute limit, approximated by a (23 × 23 × 7) supercell with 29 622 atomic sites.

Comparing the HR and DJT calculations, the DJT theory predicts a higher ZPL intensity along with more extended sidebands than HR theory, a difference that becomes particularly significant beyond 250 meV above the ZPL. Across all absorption spectra, sharp peaks near 75 meV arise from quasi-localized phonon modes. In the kh divacancy, an additional prominent peak at 38 meV, resulting from delocalized bulk-like vibrations, exhibits a more pronounced intensity and a sideband that decays faster than in other divacancies. The total electron–phonon coupling factors are calculated to be 3.54 (hh), 3.37 (kk), 3.11 (hk), and 2.83 (kh). The DWFs computed using HR theory are 2.53% (hh), 3.02% (kk), 4.02% (hk), and 5.39% (kh). For the DJT model, the calculated DWFs for the hh and kk divacancies are slightly higher, at 3.42% and 3.72%, respectively.

Discussion

In summary, first-principles calculations were employed to examine the optical properties of neutral divacancies in the 4H-SiC polytype, with particular attention to the DJT effect present in the excited state of axial configurations. The approach used herein enables accurate predictions of emission and absorption spectra in the dilute limit using the force constant embedding methodology, filling gaps left by previous works that did not explicitly address the DJT effect or calculate absorption lineshapes for all configurations. Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that the r2SCAN functional provides accurate predictions of the electronic, vibrational and vibronic properties at a fraction of the computational cost compared to hybrid functionals like HSE06, as reflected in the strong agreement between calculated and experimental ZPL, ZFS, DWF values and lineshapes.

The spectral features of axial divacancies have been modeled while explicitly accounting for the DJT effect using novel multimode methodology 29. During the 3E → 3A2 optical transition for axial divacancies, where degeneracy is present in the initial state, the lineshapes calculated using HR theory closely match those obtained with the more rigorous multimode DJT approach. In contrast, for the 3A2 → 3E optical transition to the degenerate excited state, multimode DJT treatment becomes essential to accurately capture the complex optical features that are characteristic of systems with strong JT interactions, such as the emission lineshape in the negatively charged nickel-vacancy center in diamond. Furthermore, the DWFs derived from multimode DJT theory predict a higher ZPL intensity and an extended high-energy tail beyond what is predicted by standard HR theory. This asymetry between emission and absorption lineshapes, resulting from the DJT effect, underscores the critical role of this effect in accurately describing optical transitions involving degenerate states.

Interestingly, our results predict spontaneous symmetry breaking in the excited state of the kh divacancy due to the PJT effect. Compared to other configurations, the kh-VV0 exhibits the lowest mass-weighted displacement and total electron–phonon coupling, the highest DWF, and unique polarization characteristics, making it selectively excitable in applications involving an ensemble of divacancies. These unique vibrational and optical properties of the kh configuration set it apart from hh, kk, and hk configurations.

The methodologies discussed herein not only advance understanding of the neutral divacancy’s optical properties in 4H-SiC, but also illustrate a broader framework for applying multimode DJT theory to other defects with strong vibronic coupling. By addressing both emission and absorption phenomena with multimode DJT theory, the present study paves the way for exploring electron–phonon interactions and optical properties in other spin defects with pronounced JT effect, informing future designs for quantum emitters, sensors and related applications in quantum technologies.

Methods

Electronic structure calculations

Calculations have been performed within the spin-polarized DFT framework. Projector-augmented wave (PAW) approach was used with a plane-wave energy cutoff of 600 eV to describe the interaction of electrons with atomic cores. All calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) with the meta-GGA class r2SCAN functional30,43. This functional was chosen due to its accuracy in describing the APES for covalent materials like diamond, SiC, and Si compared to both GGA and hybrid functionals44. Furthermore, when calculating optical excitation energies, r2SCAN yields results with accuracy that is close to the much more computationally expensive hybrid or beyond-RPA methods29,44,45,46.

Divacancy defects were modeled using the supercell approach47. All neutral divacancy (VSi \({{\rm{V}}}_{\,\text{C}\,}^{0}\) or VV0) centers were created by removing one Si and one C atom from a (6 × 6 × 2) supercell with 576 atomic sites. Brillouin zone sampling was done using a single k-point (at Γ). The stopping criterion for the electronic self-consistent loop and ionic relaxation were set to 10−8 eV and 10−4 eV Å−1, respectively.

Zero-field splitting and optical excitation energy calculations

The methodology of Ivady et al. implemented in the VASP code was used to calculate the ZFS parameters48. The ZPL energies were calculated utilizing the Δ-self consistent field or ΔSCF approximation, the accuracy of which has been demonstrated in various instances when applied to defects in solids22,31,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. The excited states are obtained by constraining the occupancies of the Kohn–Sham single-particle levels by promoting one electron from the highest occupied level in the spin-minority channel to the next higher energy level in the same spin channel. In the case of hh and kk divacancies, the excited triplet state 3E has an electronic configuration a1e3 and is an E ⊗ (e ⊕ e ⋯ ) JT system. To address computational issues stemming from the JT distortion in the excited state, caused by the degeneracy between the \({a}_{1}{e}_{x}^{1}{e}_{y}^{2}\) and \({a}_{1}{e}_{x}^{2}{e}_{y}^{1}\) configurations, the charge density was approximated by maintaining an electronic configuration of \({a}_{1}{e}_{x}^{1.5}{e}_{y}^{1.5}\). This practical approach helps limit the excited state density to an average between the two degenerate configurations while preserving the C3v symmetry.

Vibronic states and JT Hamiltonian

In this section, we focus exclusively on the vibronic states of axial divacancies exhibiting C3v symmetry. For a non-degenerate electronic state, the vibronic state is expressed within the adiabatic approximation as

where \({\chi }_{l}^{{a}_{1}}({{\bf{Q}}}_{{a}_{1}})\) and \({\chi }_{k}^{e}({{\bf{Q}}}_{e})\) represent the harmonic components of the vibrational wave function, corresponding to symmetry-preserving (a1) and symmetry-breaking (e) vibrational modes, respectively. These components are derived from standard adiabatic phonon analysis, where l and k label the respective harmonic excitations. The symmetry-adapted normal coordinates Q collectively encapsulate the vibrational degrees of freedom. The electronic wave function, denoted by \(\left\vert A\right\rangle\), depends solely on the electronic degrees of freedom within the static adiabatic approximation, remaining decoupled from vibrational dynamics in this formalism.

For an E ⊗ (e ⊕ e ⊕ ⋯ ) system, the vibronic Hamiltonian describing the linear JT interaction between an orbital doublet and e-symmetry vibrational modes can be expressed as \(\hat{{\mathcal{H}}}={\hat{{\mathcal{H}}}}_{0}+{\hat{{\mathcal{H}}}}_{{\rm{JT}}}\). In the basis of electronic states \(\left\vert {E}_{x}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {E}_{y}\right\rangle\), the zero-order Hamiltonian describes vibrational motion within a harmonic potential and is given by

The linear JT coupling term is28,56

where ωk are the angular frequencies of vibrations, derived as eigenvalues of the zero-order Hamiltonian [Eq. (3)], and Kk are the dimensionless vibronic coupling constants41. The index k = 1, …, N encompasses all pairs of degenerate e-symmetry vibrations, which transform according to the Cartesian xy representation, analogous to the transformation properties of the electronic states. The solutions of the vibronic Hamiltonian are

where the coefficients \({\chi }_{m}^{e;\gamma }({{\bf{Q}}}_{e})\) are ionic prefactors determined by solving the JT problem, and the quantum number m labels the vibronic excitations of the system.

The complete wave function, including the symmetry-preserving modes, within the degenerate electronic manifold corresponding to the JT-active state, is given as18,29\(\left| {\Psi }_{nm}\right\rangle ={\chi }_{n}^{a}({{\bf{Q}}}_{a})\left| {\Phi }_{j;m}\right\rangle ,\) where n labels the harmonic states associated with the symmetry-preserving modes.

The solution to the DJT problem involves three essential steps:

-

1.

Calculation of the zero-order vibrational structure. This step requires solving the zero-order Hamiltonian [Eq. (3)]. To suppress the JT interactions, the electronic configuration \({a}_{1}{e}_{x}^{1.5}{e}_{y}^{1.5}\) is used, following the methodology outlined in refs. 18,29. This configuration effectively models an ensemble of two degenerate electronic states with equal probability, ensuring that the C3v symmetry is preserved. By maintaining this symmetry, the vibrational modes can be systematically classified according to the irreducible representations of the C3v point group.

-

2.

Estimation of the vibronic coupling parameters. The vibronic coupling constants, Kk, are extracted by analyzing the geometry change ΔQJT associated with the transition from the high-symmetry to the low-symmetry atomic configuration, as detailed in Supplementary Note 4. These constants are calculated by projecting ΔQJT onto a pair k of e-symmetry normal modes, according to the expression18

$${K}_{k}^{2}=\frac{{\omega }_{k}\Delta {Q}_{k}^{2}}{2\hslash },$$(6)where \(\Delta {Q}_{k}^{2}=\Delta {Q}_{kx}^{2}+\Delta {Q}_{ky}^{2}\) represents the squared projection of the k-doublet normal coordinates along the relaxation path ΔQJT. For embedded supercells, recovering ΔQJT in the dilute limit is achieved through force-based methods, as described in refs. 18,29.

-

3.

Diagonalizing the vibronic Hamiltonian. The diagonalization of the Hamiltonian \({\mathcal{H}}={{\mathcal{H}}}_{0}+{{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{JT}}}\), which includes many vibrational modes, poses significant computational challenges due to the large matrix dimensions. To manage this complexity, we adopt an approach based on a reduced set of effective modes18,29. In this method, the spectral density of the JT coupling is defined as \({K}^{2}(\hslash \omega )={\sum }_{k}{K}_{k}^{2}\delta (\hslash \omega -\hslash {\omega }_{k})\). This density is then approximated by a density stemming from a smaller number of effective modes \({K}_{{\rm{eff}}}^{2}(\hslash \omega )=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{n = 1}^{{N}_{{\rm{eff}}}}{\bar{K}}_{n}^{2}{g}_{\sigma }(\hslash {\bar{\omega }}_{n}-\hslash \omega )\), where gσ is a Gaussian function with width σ. The approximation uses Neff effective vibrations, each characterized by a frequency \({\bar{\omega }}_{n}\) and an associated vibronic coupling strength \({\bar{K}}_{n}^{2}\). The parameters \({\bar{K}}_{n}^{2}\), \({\bar{\omega }}_{n}\), and σ are optimized to ensure that \({K}_{{\rm{eff}}}^{2}(\hslash \omega )\) accurately reproduces K2(ℏω). This reduction significantly lowers the computational burden, as the number of effective modes is much smaller than the total number of modes, Neff ≪ N.

To validate the reliability of the spectral functions derived from this approximation, we systematically monitor their convergence with respect to the number of effective modes. Details on the convergence analysis are provided in Supplementary Note 6.

Phonon calculations

Phonon modes of divacancies were calculated using the finite displacement method with configurations generated using the PHONOPY software package57. Displacements of ±0.01 Å from equilibrium geometries were used. Extrapolation of phonon modes to the dilute limit was done with a (23 × 23 × 7) supercell with 29,622 atomic sites using the force constant matrix embedding methodology presented in refs. 17,18. To achieve a smooth representation of the electron–phonon spectral function, delta functions were approximated with Gaussian functions of variable widths (σ), decreasing linearly from 3.5 meV at zero frequency to 1.5 meV at the highest phonon energy.

Calculation of optical lineshapes

In the zero-temperature limit (T = 0 K) of the Franck–Condon approximation, the normalized lineshape L(ℏω) for absorption and luminescence is given by18

where C is a normalization constant, A(ℏω) is the spectral function describing the phonon sideband, and κ takes the value of 3 for emission and 1 for absorption. For transitions involving a single degenerate orbital doublet, the spectral function is expressed as a convolution18:

where \({A}_{{a}_{1}}\) and Ae are the spectral functions corresponding to symmetry-preserving (a1) and symmetry-breaking (e) vibrational modes, respectively. The a1 spectral function is given by

where the minus sign applies to emission, the plus sign to absorption, i and f refer to the initial and final electronic states, and \({\varepsilon }_{fn}^{{a}_{1}}\) is the energy eigenvalue of the nth vibrational level in state f.

The spectral function for JT active e vibrational modes is

for emission, whereby the initial state is degenerate, and

for absorption, whereby the degeneracy is in the final state. Here, the x and y superscripts refer to ionic prefactors in Eq. (5), and \({\varepsilon }_{fm}^{e}\) represents the energy of the mth vibronic quantum level in the electronic state f.

The spectral function for symmetry-preserving a1 modes [Eq. (9)] was computed using the HR theory and the method of generating functions. This approach involves calculating partial HR factors Sk and the spectral density of electron–phonon coupling, which is defined as S(ℏω) = ∑kSkδ(ℏω − ℏωk). The spectral function \({A}_{{a}_{1}}\) is then derived from this spectral density using a time-domain generating function formalism. The methodology for calculating Sk and \({A}_{{a}_{1}}\) is well established and described in detail in refs. 17,18,58.

For the degenerate e-symmetry modes [Eqs. (10) and (11)], the spectral function was obtained by explicitly solving the vibronic problem in the form of Eq. (5) and evaluating the overlaps between the vibrational wave functions described by Eqs. (2) and (5). The delta functions in Eqs. (10) and (11) were replaced with Gaussian functions of width 3.5 meV to account for finite broadening. For benchmarking purposes, we also computed the spectral function for emission pertaining to JT active e modes using the HR theory with Eq. (9), instead of Eq. (10). In this approach, the contribution of e modes is approximated by treating the minimum of APES for e degrees of freedom in the initial state as the minimum of harmonic potential. This approximation enables the estimation of HR parameters. Although this method is not rigorous, it offers a reasonable approximation within zero-temperature theory for an initial state that is JT active, provided the total vibronic coupling strength, \({K}_{{\rm{tot}}}^{2}\), lies within the range of about 0.5–118.

Data availability

The data supporting the study's findings are available at https://bitbucket.org/puntukas/div-4h-sic.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

She, X., Huang, A. Q., Lucia, O. & Ozpineci, B. Review of silicon carbide power devices and their applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 64, 8193–8205 (2017).

Kimoto, T. & Cooper, J. A. Fundamentals of Silicon Carbide Technology: Growth, Characterization, Devices And Applications (John Wiley & Sons, 2014).

Klein, P. et al. Lifetime-limiting defects in n- 4H-SiC epilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 052110 (2006).

Ghezellou, M. et al. The role of boron related defects in limiting charge carrier lifetime in 4H-SiC epitaxial layers. APL Mater. 11, 031107 (2023).

Aharonovich, I., Englund, D. & Toth, M. Solid-state single-photon emitters. Nat. Photonics 10, 631–641 (2016).

Castelletto, S. & Boretti, A. Silicon carbide color centers for quantum applications. J. Phys. 2, 022001 (2020).

Weber, J. R. et al. Quantum computing with defects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8513–8518 (2010).

Awschalom, D. D., Hanson, R., Wrachtrup, J. & Zhou, B. B. Quantum technologies with optically interfaced solid-state spins. Nat. Photonics 12, 516–527 (2018).

Zhang, G., Cheng, Y., Chou, J.-P. & Gali, A. Material platforms for defect qubits and single-photon emitters. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 031308 (2020).

Son, N. T. et al. Developing silicon carbide for quantum spintronics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 190501 (2020).

Bathen, M. E. & Vines, L. Manipulating single-photon emission from point defects in diamond and silicon carbide. Adv. Quantum Technol. 4, 2100003 (2021).

Widmann, M. et al. Coherent control of single spins in silicon carbide at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 14, 164–168 (2015).

Castelletto, S. et al. A silicon carbide room-temperature single-photon source. Nat. Mater. 13, 151–156 (2014).

Christle, D. J. et al. Isolated electron spins in silicon carbide with millisecond coherence times. Nat. Mater. 14, 160–163 (2015).

Christle, D. J. et al. Isolated spin qubits in SiC with a high-fidelity infrared spin-to-photon interface. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021046 (2017).

Anderson, C. P. et al. Five-second coherence of a single spin with single-shot readout in silicon carbide. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm5912 (2022).

Alkauskas, A., Buckley, B. B., Awschalom, D. D. & Van de Walle, C. G. First-principles theory of the luminescence lineshape for the triplet transition in diamond NV centres. N. J. Phys. 16, 073026 (2014).

Razinkovas, L., Doherty, M. W., Manson, N. B., Van de Walle, C. G. & Alkauskas, A. Vibrational and vibronic structure of isolated point defects: the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 104, 045303 (2021).

Abtew, T. A. et al. Dynamic Jahn-Teller effect in the NV− center in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 146403 (2011).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. Ab initio calculation of spin-orbit coupling for an NV center in diamond exhibiting dynamic Jahn-Teller effect. Phys. Rev. B 96, 081115(R) (2017).

Zhang, J., Wang, C.-Z., Zhu, Z., Liu, Q. H. & Ho, K.-M. Multimode Jahn-Teller effect in bulk systems: A case of the NV0 center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 97, 165204 (2018).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. Ab initio magneto-optical spectrum of group-IV vacancy color centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021063 (2018).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. The (eg ⊗ eu) ⊗ eg product Jahn–Teller effect in the neutral group-IV vacancy quantum bits in diamond. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 18 (2019).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. Magneto-optical spectra of the split nickel-vacancy defect in diamond. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043052 (2021).

Carbery, W. P., Farfan, C. A., Ulbricht, R. & Turner, D. B. The phonon-modulated Jahn–Teller distortion of the nitrogen vacancy center in diamond. Nat. Commun. 15, 8646 (2024).

Ham, F. S. Dynamical Jahn–Teller effect in paramagnetic resonance spectra: orbital reduction factors and partial quenching of spin-orbit interaction. Phys. Rev. 138, A1727 (1965).

Longuet-Higgins, H. C., Öpik, U., Pryce, M. H. L. & Sack, R. Studies of the Jahn-Teller effect. II. the dynamical problem. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 244, 1–16 (1958).

Bersuker, I. The Jahn-Teller Effect (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Silkinis, R. et al. Optical lineshapes for orbital singlet to doublet transitions in a dynamical Jahn-Teller system: the NiV− center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 110, 075303 (2024).

Furness, J. W., Kaplan, A. D., Ning, J., Perdew, J. P. & Sun, J. Accurate and numerically efficient r2SCAN meta-generalized gradient approximation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 8208–8215 (2020).

Jin, Y. et al. Photoluminescence spectra of point defects in semiconductors: validation of first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 084603 (2021).

Csóré, A., Ivanov, I. G., Son, N. & Gali, A. Fluorescence spectrum and charge state control of divacancy qubits via illumination at elevated temperatures in 4 h silicon carbide. Phys. Rev. B 105, 165108 (2022).

Davidsson, J. Theoretical polarization of zero phonon lines in point defects. J. Phys. 32, 385502 (2020).

Stenlund, W., Davidsson, J., Armiento, R., Ivády, V. & Abrikosov, I. A. Adaq-sym: automated symmetry analysis of defect orbitals. Comput. Phys. Commun. 308, 109468 (2025).

Shafizadeh, D. et al. Selection rules in the excitation of the divacancy and the nitrogen-vacancy pair in 4H-and 6H-SiC. Phys. Rev. B 109, 235203 (2024).

Falk, A. L. et al. Polytype control of spin qubits in silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 4, 1819 (2013).

Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. P. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036402 (2015).

Fu, K.-M. et al. Observation of the dynamic Jahn-teller effect in the excited states of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 256404 (2009).

Bian, G., Thiering, G. & Gali, Á. Theory of optical spin-polarization of axial divacancy and nitrogen-vacancy defects in 4H-SiC. Phys. Rev. Research 7, 013320 (2025).

Huang, K. & Rhys, A. Theory of light absorption and non-radiative transitions in F-centres. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 204, 406–423 (1950).

O’Brien, C. M. Mary & Evangelou, S. N. The calculation of absorption band shapes in dynamic Jahn–Teller systems by the use of the Lanczos algorithm. J. Phys. C 13, 611–623 (1980).

Shang, Z. et al. Microwave-assisted spectroscopy of vacancy-related spin centers in hexagonal SiC. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 034059 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Maciaszek, M., Žalandauskas, V., Silkinis, R., Alkauskas, A. & Razinkovas, L. The application of the SCAN density functional to color centers in diamond. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 084708 (2023).

Ivanov, A. V., Schmerwitz, Y. L. A., Levi, G. & Jónsson, H. Electronic excitations of the charged nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond obtained using time-independent variational density functional calculations. SciPost Phys. 15, 009 (2023).

Maciaszek, M. & Razinkovas, L. Blue quantum emitter in hexagonal boron nitride and a carbon chain tetramer: a first-principles study. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 18979–18985 (2024).

Freysoldt, C. et al. First-principles calculations for point defects in solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 253 (2014).

Ivády, V., Simon, T., Maze, J. R., Abrikosov, I. & Gali, A. Pressure and temperature dependence of the zero-field splitting in the ground state of NV centers in diamond: a first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 90, 235205 (2014).

Jones, R. O. & Gunnarsson, O. The density functional formalism, its applications and prospects. Rev. Mod. Phys. 61, 689 (1989).

Hellman, A., Razaznejad, B. & Lundqvist, B. I. Potential-energy surfaces for excited states in extended systems. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 4593–4602 (2004).

Kowalczyk, T., Yost, S. R. & Voorhis, T. V. Assessment of the δSCF density functional theory approach for electronic excitations in organic dyes. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 054128 (2011).

Gali, A., Janzén, E., Deák, P., Kresse, G. & Kaxiras, E. Theory of spin-conserving excitation of the N- V- center in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 186404 (2009).

Davidsson, J. et al. First principles predictions of magneto-optical data for semiconductor point defect identification: the case of divacancy defects in 4H–SiC. N. J. Phys. 20, 023035 (2018).

Mackoit-Sinkevičienė, M., Maciaszek, M., Van de Walle, C. G. & Alkauskas, A. Carbon dimer defect as a source of the 4.1 eV luminescence in hexagonal boron nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 212101 (2019).

Hashemi, A. et al. Photoluminescence line shapes for color centers in silicon carbide from density functional theory calculations. Phys. Rev. B 103, 125203 (2021).

Ham, F. S. Effect of linear Jahn-Teller coupling on paramagnetic resonance in a E 2 state. Phys. Rev. 166, 307–321 (1968).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Silkinis, R. et al. Optical lineshapes of the C center in silicon from ab initio calculations: Interplay of localized modes and bulk phonons. Phys. Rev. B 111, 125136 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Financial support was kindly provided by the Research Council of Norway and the University of Oslo through the frontier research project QuTe (No. 325573, FriPro ToppForsk-program).The work of MEB was supported by an ETH Zürich Postdoctoral Fellowship. Computational resources were provided by supercomputer GALAX of the Center for Physical Sciences and Technology, Lithuania, and the High Performance Computing Center “HPC Saulėtekis” in the Faculty of Physics, Vilnius University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.R., L.V., and M.E.B. designed the research. V.Ž., R.S., and L.R. wrote the codes and performed the electron–phonon coupling calculations. V.Ž. performed the ZPL, ZFS, APES, and DWF calculations. M.E.B. and L.R. supervised the calculations. V.Ž. and L.R. analyzed the data. V.Ž., M.E.B., and L.R. wrote the paper with support and editing from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Žalandauskas, V., Silkinis, R., Vines, L. et al. Theory of the divacancy in 4H-SiC: impact of Jahn-Teller effect on optical properties. npj Comput Mater 11, 155 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01609-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01609-2