Abstract

Pressure-induced phase transformations in materials are of interest in a range of fields, including geophysics, planetary sciences, and shock physics. In addition, the high-pressure phases can exhibit desirable properties, eliciting interest in materials science. Despite its importance, the process of finding new high-pressure phases, either experimentally or computationally, is time-consuming and often driven by intuition. In this study, we use graph neural networks trained on density functional theory (DFT) equation of state data of 2258 materials and 7255 phases to identify potential phase transitions. The model is used to explore possible phase transitions in 7677 pairs of phases and promising cases are confirmed or denied via DFT calculations. Importantly, the new data is added to the training set, the model is refined, and a new cycle of discovery is started. Within 13 iterations, we discovered 28 new high-pressure stable phases (never synthesized through high-pressure routes nor reported in high-pressure computational works) and rediscovered 18 pressure-induced phase transitions. The results provide new insight and classification of pressure-induced phase transitions in terms of the ambient properties of the phases involved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the behavior of materials at elevated pressure is of interest in several fields. In planetary science, it is paramount to know the formation, structure, and evolution of planets and planetary collisions. For example, at least 5 high-pressure polymorphs of silica (one of the most abundant materials on Earth) were observed experimentally upon compression to 271 GPa1,2,3,4,5,6,7. In addition, three more high-pressure phases have been predicted theoretically at a pressure range between 600 and 1200 GPa8. In the field of materials science and chemistry, high-pressure phases with properties not achievable otherwise hold great significance. Diamond is the prototypical example, obtainable from graphite via high pressure and temperature9, the structure remains intact while quenched to ambient conditions. This high-pressure synthesis approach has been increasingly adopted10,11, especially in the pursuit of superhard materials. Several phases with Vickers hardness greater than 40 GPa, like cubic-BN12,13, cubic-Cx(BN)1-x14,15, orthorhombic γ-B2816,17, have been made via high-pressure processing. These ultrahard materials have the potential to replace diamond in machining and cutting applications. Moreover, in the field of superconductors, pressure has been proven to increase the critical transition temperature of superconducting18,19,20.

Experimentally, high-pressure experiments are mostly conducted in a diamond anvil cell coupled with diffraction techniques like X-ray diffraction. Although this method is well established, it is time-consuming and not widely available, given that the fine changes in diffraction patterns can only be resolved by synchrotron X-rays. Electronic structure calculations, such as density functional theory (DFT), on the other hand can predict equations of state (EOS) and pressure-induced phase transitions from first principles, complementing experiments. Several high-pressure phases were predicted by DFT and later confirmed by experiments. For example, covalent solids formed by carbon and nitrogen were predicted to have hardness rivaling diamond in 198921,22. It was not until 2024 that two structures, tI14-C3N4 and tI24-CN2 (in Pearson notation), were synthesized successfully through high pressure23. Similarly, being one of the most abundant minerals in earth’s lower mantle, MgO has been predicted by several DFT studies24,25,26,27,28 to undergo a B1 to B2 transformation at pressure higher than 300 GPa with the earliest work published in 198424, this was later confirmed by McWilliams et al. in 201229.

Searching for new high-pressure phases is a daunting task. For example, 17,483 compositions in the Materials Project (MP)30 have more than one crystal structure (a phase is the combination of composition and crystal structure), but the high-pressure EOS is known for only 199 structures. For a given composition, the zero-pressure ground state phase and a higher energy phase make up a pair of phases that can potentially transform. A brute force exploration of all 40,921 pairs of phases in the MP is clearly out of the question. Even with the state-of-the-art tool in high-pressure crystallography prediction, Universal Structure Predictor: Evolutionary Xtallography31,32,33, target composition, pressure, and temperature are still needed to be known at the outset. A promising approach to tackle this challenge is to use machine learning (ML) to help identify possible phases. In the related field of superhard materials, Chen et al. utilized a random forest model to find three structures in B-C-O systems with hardness greater than 40 GPa34. In addition, when predictive ML is coupled with active learning, the model performance can be improved over iterations. Farache et al. utilized active learning with molecular dynamics data to find the complex concentrated alloys that have high melting temperatures35. Similarly, Xue et al. found the composition of a NiTi-type shape memory alloy that has the highest transformation temperature in a 1,652,417-candidate material space by one active learning iteration36. Numerous similar studies across various material classes further demonstrate the effectiveness of the approach of using ML in materials discovery. The discussion can be found in several works and review papers37,38,39,40.

We designed an active learning scheme to accelerate the discovery of high-pressure phases using graph neural networks (GNN) trained on high-pressure DFT data to explore all possible pairs of phases; promising candidates are selected for further exploration with DFT. The new data generated along this process is appended to the training data and used to improve the model before a new set of predictions and tests are carried out. We performed 13 iterations and identified 28 new high-pressure phases and rediscovered 18 phases. Furthermore, analyzing this vast amount of data provides a new insight into the mechanism of pressure-induced phase transformations.

Results

General description of the active learning scheme

Our active learning scheme, see Fig. 1, seeks to discover new high-pressure stable phases in every single- and two-element material available in the MP30. This includes 2,880 materials systems (characterized by their composition) and 10,557 phases. To effectively explore the possible pressure-induced phase transformations and discover new high-pressure phases, we trained a GNN model to predict the enthalpy as a function of pressure for a wide range of materials using DFT data. In our dataset, a data entry includes: (i) the zero-pressure structure, (ii) the target pressure, and (iii) the enthalpy difference to zero-pressure structure (∆H(P)). Initially, this model was trained with the data from three sources: 177 EOS up to high pressures from our in-house CellRelaxDFT tool available on nanoHUB41, 199 EOS from the MP, and 6879 materials in the MP with zero-pressure bulk modulus. (The bulk modulus data were generated using the Birch–Murnaghan EOS42 with the retrieved bulk modulus and an assumed first derivative of bulk modulus of four. See the “Methods” section for more details.) The numbers of data points are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. S1.

The concept of the graph neural network architecture in this figure is adapted from MEGNet43, Chemistry of Materials, 2019, with permission from the authors. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

The data were then used to train the GNN model, implemented using the MEGNet framework43, which takes the zero-pressure structure as input and predicts EOS data, as discussed below. Once trained, this computationally inexpensive ML model is applied to all the pairs of phases of each system to identify possible phase transitions. As mentioned above, we explore all pairs of phases with the constraint that one be the lowest energy phase at zero pressure. We then scanned pressures from 0 to 500 GPa in steps of 5 GPa and searched for a change in low-enthalpy phase. Out of all the pairs of phases identified by the GNN, we select those with the highest confidence, using an ensemble approach, for DFT confirmation. The EOS of the selected phases are then characterized using DFT, and the existence of a phase transformation is confirmed or denied. The new data are added to the training set, and a new iteration is started by re-training the model.

To simplify data management, we leverage nanoHUB’s44 infrastructure for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR)45 workflows and data. The DFT relaxations of each structure to a desired target pressure are implemented as a Sim2L46, denoted as CellRelaxDFT41 and published for open online simulations. If a phase transition was predicted by DFT based on the enthalpies, we further investigate the dynamical stability by DFT phonon calculations at both transformation pressure and zero pressure. Calculations of mechanical properties were also performed for new high-pressure phases that were found to be dynamically stable at zero pressure.

Performance and improvements of the model

Since the zero-pressure enthalpy of all phases is available from DFT calculations at the MP, the ML model is trained to predict the change in enthalpy as a function of pressure. The enthalpy of all phases is then obtained as: \(H(P)={E}_{{\rm{M}}{\rm{P}}}+\Delta {H}_{{\rm{G}}{\rm{N}}{\rm{N}}}({\rm{P}})\), where EMP is the energy above hull available in the MP (computed with generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with projector augmented waves (PAWs)). This approach enables us to maximize the use of the available DFT results for 2880 materials and 10,557 phases. For the first 4 generations, we trained the model for three target properties, ΔH, ΔE, and PV (pressure times volume). The intention was to validate whether the predicted ΔE + PV matched the predicted ΔH, which was found to be in good agreement. To assess model uncertainty and prevent overfitting from a single model, starting in generation 2, five separate models were trained, and the predictions were aggregated from the results of the five models. These five models are identical in terms of structure and training data, the only difference is the randomized initial weights. To assess the model accuracy, we performed a fivefold cross-validation on the training data after our final generation. The mean absolute error (MAE) values for each test set from the fivefold cross-validation are similar to the MAE we obtained from our models (see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material), which indicates minimal overfitting. Supplemental Material contains the full cross-validation methodology and results, along with MAE values (Table S1) and parity plots (Fig. S2).

The generation 2 model has an overall MAE of 0.012 (eV/atom) averaged from five models. The following two generations also resulted in similar accuracy. However, despite this promising result from generations 1 to 4, the model did not guarantee the condition ΔH(P = 0) = 0. When this non-zero enthalpy is added back to EMP, it can alter the relative zero-pressure stability between different phases, affecting the identification of phase transformations. Examples are provided in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material, which show a false negative prediction and a false positive prediction made by the generation 4 model. To address this challenge, we modified the model starting in generation 5. Instead of training models to predict ΔH directly, they were trained to predict ΔH/P, and these values were converted back to ΔH when the model was used. This strategy ensures the predicted ΔH is always zero at zero pressure. (See Fig. S3 for how generation 5 corrects the two false prediction examples of generation 4.) After adopting this new approach, the model accuracy in the prediction of ΔH decreased slightly, especially for high-pressure values. This can be understood since the errors in ΔH/P will be magnified for large pressures. But importantly, a tradeoff of accuracy in exchange for the correct low-pressure phase stability was beneficial in the identification of possible phase changes.

Another improvement to the model was made starting generation 10. For generations 1–9, the CellRelaxDFT data that were used for training were all computed with ultrasoft pseudopotential (USPP)47 and Grimme-D2 van der Waals correction48. In a separate investigation on the accuracy of DFT at high-pressure calculations, we found that the combination of PAW49 with no van der Waals correction provides the most accurate high-pressure EOS and phase transformation predictions among different DFT approximation combinations50. To incorporate the more accurate PAW data without abandoning the USPP + D2 data, which has more data points, we introduced an additional state variable in the graph to account for the differences in pseudopotentials. This approach, known as multimodal learning51, is common for integrating multi-fidelity data52,53,54,55. After CellRelaxDFT PAW data were incorporated, the ΔH MAEs of the MP data and CellRelaxDFT USPP data remained numerically similar (Fig. 2a, b), proving the new modification did not affect the accuracy of the existing data. In terms of MAE of ΔH/P, the MAEs of the newly added CellRelaxDFT PAW data have lower ΔH/P MAE than USPP, benefiting from the large number of data points of the MP data. Surprisingly, ΔH/P MAEs of the MP data and CellRelaxDFT USPP data decrease slightly after generation 10 (Fig. 2c).

a, b Parity plots of enthalpy difference (ΔH) for all training data from generations 5 and 10. Numbers are averaged from predictions from five sub-models, and error bars are plotted by the standard deviation of the five predictions. Data points are colored by their sources; Materials Project (MP) equation of state and MP bulk modulus datasets are combined and labeled as MP. The mean absolute error (MAE) of the entire dataset and separate datasets are listed at the top of the individual plots. c Mean absolute error of enthalpy difference divided by pressure (ΔH/P) for generations 5–13. *The MAE of projector augmented wave (PAW) data drastically increased in generation 12 because we incorporated equation of state data in the training set that were computed with Hubbard U correction (DFT + U). After identifying that the results were inconsistent, we removed the DFT + U data from the training data.

Discoveries of new high-pressure stable phases

After 13 active learning generations, we found 28 new pressure-induced phase transformations and rediscovered 18 ones, the latter are cases that were not part of the training set but had previously been reported in the literature. Table S2 lists all 28 new phase transformations identified and verified by DFT. Figure 3 shows the number of potential phase transitions verified by DFT calculations as a function of optimization iteration. Green bars represent the pairs of phases that were confirmed by the electronic structure calculations. In generations 1–4, we selected 41 potential phase transformations for validation, and 13 were confirmed. Eight of these 13 pairs represent new transformations, not previously reported in the literature; the remaining five pairs are noted as rediscoveries in Fig. 3. For generations 5–13, where we follow the selection criteria described in the “Methods” section, a total of 39 pairs of phases were selected for DFT verification and 20 phase transformations (green in Fig. 3) were confirmed. This yields a ~51% success rate. It should be noted that there are 7 pairs of materials that were not confirmed nor denied during the sequential discovery effort since DFT calculations failed to converge with our default parameters and time allocation (gray data and data with gray diagonal lines in Fig. 3). We further ran these pairs in high-performance computing facilities at Purdue University; one pair resulted in a phase transformation, four pairs resulted in no phase transformation, and there are still two others that have proven hard to converge. In addition, 13 transformations that are predicted by the final model, though not chosen for DFT validation, match records in our literature database, UnderPressure56 (see “Methods” section for more details of UnderPressure). These 13 transformations are also considered as rediscoveries, bringing the total number of rediscovered transformations to 18 when combined with the 5 transformations from generations 1 to 4.

For generations 5–13, one pair was picked in each 50-GPa transformation pressure interval, but not every bin has predicted transformations. Therefore, the total number of pairs that were picked varies slightly across generations. For generation 4, we did not select any pairs to validate since we noticed that graph neural networks (GNN) can have wrong ground state phase prediction. The pairs with gray diagonal lines are pairs that were not able to converge in the CellRelaxDFT tool because of the 24 hours wall time limitation that is set in the tool. These pairs were run outside of the CellRelaxDFT tool after generation 13 and were not included in any of the training data. Two pairs that we could not converge even with the expensive computational resource used are marked gray on the plot.

To assess the dynamical stability of the 28 new high-pressure phases, we conducted phonon calculations of the low- and high-pressure phases both at zero pressure and at the transformation pressure. The results of phonon stability are summarized in Table S2. Out of the 28 new high-pressure phases, 10 of them are predicted to be dynamically stable both at zero pressure and at the transformation pressure. This indicates that these phases are potentially quenchable and can be metastable at ambient conditions. These cases are more interesting for experimental confirmation and are presented in Table 2. Another four phases are dynamically stable at transformation pressure but not at zero pressure. The remaining 14 phases that were not found to be dynamically stable at the transformation pressure were further relaxed without symmetry constraints. We found a monoclinic phase for Cr2O3 with P21/c symmetry (space group number 14) that is dynamically stable at the transition pressure not reported in the MP. A more comprehensive search was done using the Optimade tool57,58,59 and the P21/c Cr2O3 phase has not been reported in any of the supported databases. The structure file of this phase is provided in the Supplemental Material. The elastic constants and associated moduli of the 10 phases that are dynamically stable at zero pressure were calculated and included in Table S3. The transformations of these 10 pairs span a wide range of pressure, with the highest being 432.9 GPa of Ni3Sn that transforms from a hexagonal phase to an orthorhombic phase.

Discussion

We hypothesized that the large amount of data collected during this study could help to understand the possible driving force underlying pressure-induced phase transformations and even classify them. We find it useful to think about the ground state phase and potential high-pressure phase in energy-volume space. A phase transition occurs if the EOS of two phases intersect. We envisioned two possible classes of transformations, illustrated in Fig. 4. In the first case, the high-pressure phase is denser (i.e., lower zero-pressure volume per formula unit, V0) than the zero-pressure phase. This is the case for SnC and BaTe, see Fig. 4a, b, note that the differences in bulk modulus for these two examples are minimal (<10 GPa). The second class of transformation is driven by the high-pressure phase being more compressible (i.e., lower bulk modulus) than the zero-pressure phase. A prototypical example is Ti3O4, Fig. 4c, that undergoes a transformation between a I4/mmm phase and a Cmmm phase with a bulk modulus smaller by ~34 GPa.

a SnC, b BaTe, and c Ti3O4. The zero-pressure stable phases are colored blue, and the high-pressure stable phases are colored orange. Differences between the two phases in terms of zero-pressure volume (∆V0), zero-pressure bulk modulus (∆B), and zero-pressure energy (∆E0) are listed in the plots. The vertical lines and horizontal lines indicate V0 and E0, respectively. The Materials Project (MP) material IDs of the phases are provided in the labels of the curves. a, b show phase transformation because the high-pressure phase is denser, and c shows phase transformation because the high-pressure phase is softer.

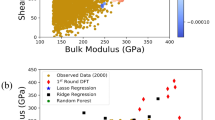

To analyze our hypothesis, all the transformations we have collected are plotted on a ∆V0 and ∆B space (zero-pressure volume difference and bulk modulus difference) in Fig. 5. As expected, the first quadrant (∆V0 > 0 and ∆B > 0) contains essentially no cases and all known phase transformations exhibit some combination of the high-pressure phase being either denser or softer than the ambient one. We note that most cases lie in the second quadrant, indicating that transformations to a denser phase are quite common. Transformations to softer materials (fourth quadrant) are also common but slightly less likely than transformations to a denser phase. In our dataset, 104 transformations are in the second quadrant, while 28 transformations are in the fourth quadrant. These results can indicate that transformation to denser materials happens more frequently in nature but can also indicate that transitions through lower bulk modulus are less explored by researchers. We also note that there are a few cases of both denser and softer (third quadrant) high-pressure phases, as this is an unlikely combination of properties. Shaded forbidden areas in the second and fourth quadrants indicate the need to compensate with higher density for a higher bulk modulus or with compliance for a lighter phase.

The percentage of data points in each quadrant relative to the entire dataset is indicated in the plot. Red stars represent newly discovered transformations; yellow stars indicate rediscoveries. Black crosses indicate literature data collected in the UnderPressure database56. Circles colored on a blue–neon green scale correspond to predictions from the final machine learning model that were not selected for density functional theory (DFT) validation, where the color reflects the standard deviation in the model ensemble predictions.

In conclusion, through the integration of GNN, DFT, and active learning, we successfully discovered 28 new pressure-induced phase transformations and rediscover 18 phase transformations. Out of the 28 new discoveries, 14 high-pressure phases are dynamically stable at the transformation pressure (10 phases are dynamically stable at both the transformation pressure and zero pressure, and the other 4 phases are dynamically stable only at the transformation pressure), and a new dynamically stable structure not recorded in the MP30 is found. This proves that our active learning scheme can serve as a good indicator in finding possible phase transformations, which is contrary to a brute-force approach or searching by intuition. Furthermore, we utilized the data we generated to provide a simple explanation for the cause of pressure-induced phase transformations. We found that for a transformation to occur, the high-pressure phase must be much softer or much denser than the zero-pressure stable phase. Important byproducts of this study are two FAIR tools/repositories for high-pressure research. More than 200 EOS are available in CellRelaxDFT, and new EOS can be generated easily. Additionally, the UnderPressure database documents 123 pressure-induced phase transformations. The presence of high-pressure phases is of particular interest to the discovery of high-temperature superconductors, and we believe the presented databases could be useful for exploring such applications. Future work should benchmark the use of ML interatomic potentials, such as the universal force fields from Chen and Ong60 and Qi et al.61. If these models can accurately reproduce the EOS across a wide range of pressures and compositions, they could greatly increase the efficiency of the high-throughput calculations.

Methods

CellRelaxDFT simulations

Enthalpies at high pressure of different structures are calculated by DFT implemented by a Sim2L46 on nanoHUB44, CellRelaxDFT41. CellRelaxDFT uses Quantum Espresso62 to relax a structure to a given pressure. The tool takes a set of user-defined inputs, which includes the MP material ID for the structure of interest, target pressure, DFT level of theory, and calculation accuracy control. Using these inputs, the tool generates the Quantum Espresso input files for structural relaxation and submits the simulation to the high-performance computers at Purdue University. Once the simulation is successfully complete, the tool post-processes the Quantum Espresso output files and displays the results including relaxed structure, output pressure, output energy, etc. to the user. A Sim2L Results Database (ResultDB63) stores the inputs and outputs of all complete simulations immediately and can be easily queried by any other user. During the relaxation process, the structure is initially hydrostatically compressed by an amount approximated according to the target pressure and the bulk modulus of the material. Then, several ionic relaxations and self-consistent field electronic calculations are performed until the values of the stress tensor meet the target pressure, and other convergent criteria (energy and force) specified by the user are also satisfied. As for the level of theory, the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) solid version64 of GGA was used for the exchange correlation functional. Two pseudopotentials are used for this study, USPP47 and PAW49. For the first 9 iterations, we used USPP with Grimme-D2 van der Waals correction48. For the number of k-points, we used 0.10 Å−1 spacing to sample the reciprocal space for a material that is metallic at zero-pressure, and 0.22 Å−1 for non-metallic materials. This will ensure that the number of k-points is adjusted according to the unit cell size. In all, 100 Rydberg was used for the kinetic energy cutoff for the basis set. The details of the DFT simulations, including the convergence tests and the evaluation of pseudopotentials and van der Waals corrections, are documented in another work50. A more detailed description of each input and output for the CellRelaxDFT tool is provided in the Sim2L41.

Dataset

The initial training dataset contains data from three sources: CellRelaxDFT, MP EOS, and MP bulk modulus. The initial CellRelaxDFT data had EOS for 177 phases. For each phase, 12 different target pressures from 0 GPa to 500 GPa were calculated, namely −1, 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 GPa. We also included DFT relaxations at different pressures available for another 199 materials in MP, these data are annotated as MP EOS data. In addition, a subset of structures in the MP database has bulk modulus data available. For each phase, we assume the pressure derivative of bulk modulus (B’) to be 4, which is typical for most materials, and manually calculate the energies at five different volumes (1.02 V0, 1.01 V0, 0.99 V0, 0.98 V0, and 0.95 V0) using Birch–Murnaghan EOS (Eq. 1)42.

where V0 and E0 are the volume and energy of material at zero pressure, B is the bulk modulus, and B’ is the first derivative of bulk modulus with respect to pressure. Data from the three sources were combined to form the initial training set.

GNN model construction

The GNN models are designed to predict the enthalpy difference relative to the zero-pressure structure and implemented using the MEGNet framework43. Crystal structures were retrieved from the MP and converted to graphs using the provided functions in the MEGNet package. Two state attributes, pressure and pseudopotential (added after generation 10), were defined. The number of features (attributes) for bonds and nodes was set to 100 each, consistent with the default values in the MEGNet documentation. The cutoff distance for the graph was set to 6 Å to capture many-body interactions. Because of the scarcity of data, no splitting was applied, and all available data were used for training.

Prediction and decision-making process

We used the GNN models to predict the EOS of the 10,557 phases and identified phase transitions in all 7677 pairs of phases where one is the zero-pressure ground state. We only further considered consensus phase changes, predicted by all five models, and recorded the average and the standard deviation of the transformation pressures. A subset of these transformations was selected for DFT characterization. The predicted transformations were first binned by average transformation pressure in intervals of 50 GPa, then one material was picked in each bin by a set of criteria (listed below). This set of criteria was not followed in generations 1–4, as we were exploring different ways of selecting materials.

-

1.

Exclude transformations where the low-pressure phase has energy above the hull value larger than 0.5 eV. This criterion filters out the energetically unfavorable phases at ambient conditions.

-

2.

If the structure has more than 30 atoms in the unit cell, it is excluded to avoid potential expensive simulations in CellRelaxDFT.

-

3.

The remaining transformations were first ranked by the standard deviation of the predicted transformation pressure, which means that we are most confident in these transformation predictions.

-

4.

If the standard deviation is the same for the highest-ranking transformations, then they are further ranked by the energy above hull difference between the two phases. Transformation is more likely to happen if the energy difference is small.

-

5.

Once the list is filtered and ranked, we start from the highest-ranked material and search if this transformation has been reported in the literature or match our pressure-induced phase transformation data in our nanoHUB database, UnderPressure56 (see the following section for the description of UnderPressure). If the transformation has been studied, either experimental or computational, we skip the transformation. If the transformation has not yet been studied, it is then selected to be validated with DFT.

After materials were chosen in each bin, DFT simulations were conducted using CellRelaxDFT to validate the transformation. For every structure, we ran 12 relaxations at different pressures (−1, 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 GPa). The Birch-Murnaghan EOS was fit using results from these simulations, and the EOS of different phases were compared to find the presence of a transformation and the corresponding transformation pressure. Importantly, the DFT simulation results were always appended to the training dataset for the next active learning loop.

UnderPressure, pressure-induced phase transformation database

As a supplement to the active learning loop, another FAIR nanoHUB Sim2L, UnderPressure56, was built to document the pressure-induced structural transformations. We found that despite the massive number of works in high-pressure structural transformations, such as the comprehensive summary by McMahon and Nelmes for elemental metals65, there is no open-access repository or database that documents the discovered transformations. This makes literature review and data mining for researchers very challenging. Our intention with UnderPressure is to provide a database infrastructure that allows researchers to input data and easily query data from others. The tool records the basic information of the transformation, including the two zero-pressure crystal structures, the transformation pressure, and the transformation temperature. It also documents the research method, detailing the experiment or simulation, and includes the digital object identifier if the data is from a published work. Approximately 120 transformations from the literature have been collected and used to check the accuracy of the model and the novelty of the predicted transformations. We acknowledge that these 120 data points represent only a small portion of all known transformations, but we lack the time and manpower to gather and input all the transformations. Therefore, we encourage researchers to use UnderPressure as a platform to document their findings so that these FAIR data can be easily utilized for any subsequent use.

Phonon and elastic constant calculations of the new phases

For the transformations validated with DFT simulations, we conducted further computations to characterize the dynamic stability and mechanical properties of the high-pressure phases. These DFT simulations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) using the GGA with the PBE exchange-correlation functional66,67,68 via PAW pseudopotentials49. To evaluate the dynamical stability for each high-pressure phase, we computed the phonon dispersion at pressures of 0 GPa and the corresponding transformation pressure using the finite-displacement method as implemented in the PHONOPY code69,70. The mechanical properties were also derived from the elastic tensor. Using the python package elastic-vasp71,72,73, we generated strained states and computed the corresponding stress tensor with DFT to ultimately fit the elastic tensor and derive various mechanical properties for each phase.

References

Tsuchida, Y. & Yagi, T. A new, post-stishovite high-pressure polymorph of silica. Nature 340, 217–220 (1989).

Kingma, K. J., Cohen, R. E., Hemley, R. J. & Mao, H. Transformation of stishovite to a denser phase at lower-mantle pressures. Nature 374, 243–245 (1995).

Dubrovinsky, L. S. et al. Experimental and theoretical identification of a new high-pressure phase of silica. Nature 388, 362–365 (1997).

Andrault, D., Fiquet, G., Guyot, F. & Hanfland, M. Pressure-induced Landau-type transition in stishovite. Science 282, 720–724 (1998).

Ono, S., Hirose, K., Murakami, M. & Isshiki, M. Post-stishovite phase boundary in SiO2 determined by in situ X-ray observations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 197, 187–192 (2002).

Murakami, M., Hirose, K., Ono, S. & Ohishi, Y. Stability of CaCl2-type and α-PbO2-type SiO2 at high pressure and temperature determined by in-situ X-ray measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL016722 (2003).

Dubrovinsky, L. S. et al. A class of new high-pressure silica polymorphs. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 143–144, 231–240 (2004).

Liu, C. et al. Mixed coordination silica at megabar pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 035701 (2021).

Bundy, F. P., Hall, H. T., Strong, H. M. & Wentorfjun, R. H. Man-made diamonds. Nature 176, 51–55 (1955).

Badding, J. V. High-pressure synthesis, characterization, and tuning of solid state materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 28, 631–658 (1998).

Walsh, J. P. S. & Freedman, D. E. High-pressure synthesis: a new frontier in the search for next-generation intermetallic compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 1315–1323 (2018).

Wentorf, R. H. Jr. Cubic form of boron nitride. J. Chem. Phys. 26, 956 (1957).

Bundy, F. P. & Wentorf, R. H. Jr. Direct transformation of hexagonal boron nitride to denser forms. J. Chem. Phys. 38, 1144–1149 (1963).

Knittle, E., Kaner, R. B., Jeanloz, R. & Cohen, M. L. High-pressure synthesis, characterization, and equation of state of cubic C-BN solid solutions. Phys. Rev. B 51, 12149–12156 (1995).

Solozhenko, V. L. Synthesis of novel superhard phases in the B-C-N system. High. Press. Res. 22, 519–524 (2002).

Solozhenko, V. L., Kurakevych, O. O. & Oganov, A. R. On the hardness of a new boron phase, orthorhombic γ-B28. J. Superhard Mater. 30, 428–429 (2008).

Oganov, A. R. et al. Ionic high-pressure form of elemental boron. Nature 457, 863–867 (2009).

Chu, C. W. et al. Superconductivity above 150 K in HgBa2Ca2Cu3O8+δ at high pressures. Nature 365, 323–325 (1993).

Drozdov, A. P., Eremets, M. I., Troyan, I. A., Ksenofontov, V. & Shylin, S. I. Conventional superconductivity at 203 kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system. Nature 525, 73–76 (2015).

Drozdov, A. P. et al. Superconductivity at 250 K in lanthanum hydride under high pressures. Nature 569, 528–531 (2019).

Liu, A. Y. & Cohen, M. L. Prediction of new low compressibility solids. Science 245, 841–842 (1989).

Dong, H., Oganov, A. R., Zhu, Q. & Qian, G.-R. The phase diagram and hardness of carbon nitrides. Sci. Rep. 5, 9870 (2015).

Laniel, D. et al. Synthesis of ultra-incompressible and recoverable carbon nitrides featuring CN4 tetrahedra. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308030 (2024).

Chang, K. J. & Cohen, M. L. High-pressure behavior of MgO: structural and electronic properties. Phys. Rev. B 30, 4774–4781 (1984).

Bukowinski, M. S. T. First principles equations of state of MgO and CaO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 12, 536–539 (1985).

Mehl, M. J., Cohen, R. E. & Krakauer, H. Linearized augmented plane wave electronic structure calculations for MgO and CaO. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 93, 8009–8022 (1988).

Karki, B. B. et al. Structure and elasticity of MgO at high pressure. Am. Mineral. 82, 51–60 (1997).

Strachan, A., Çağin, T. & Goddard, W. A. Phase diagram of MgO from density-functional theory and molecular-dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. B 60, 15084–15093 (1999).

McWilliams, R. S. et al. Phase transformations and metallization of magnesium oxide at high pressure and temperature. Science 338, 1330–1333 (2012).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Oganov, A. R. & Glass, C. W. Crystal structure prediction using ab initio evolutionary techniques: principles and applications. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 244704 (2006).

Oganov, A. R., Ma, Y., Lyakhov, A. O., Valle, M. & Gatti, C. Evolutionary crystal structure prediction as a method for the discovery of minerals and materials. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 71, 271–298 (2010).

Oganov, A. R., Lyakhov, A. O. & Valle, M. How evolutionary crystal structure prediction works—and why. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 227–237 (2011).

Chen, W.-C., Schmidt, J. N., Yan, D., Vohra, Y. K. & Chen, C.-C. Machine learning and evolutionary prediction of superhard B-C-N compounds. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 1–8 (2021).

Farache, D. E., Verduzco, J. C., McClure, Z. D., Desai, S. & Strachan, A. Active learning and molecular dynamics simulations to find high melting temperature alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 209, 111386 (2022).

Xue, D. et al. An informatics approach to transformation temperatures of NiTi-based shape memory alloys. Acta Mater. 125, 532–541 (2017).

Ramprasad, R., Batra, R., Pilania, G., Mannodi-Kanakkithodi, A. & Kim, C. Machine learning in materials informatics: recent applications and prospects. npj Comput. Mater. 3, 1–13 (2017).

Gubernatis, J. E. & Lookman, T. Machine learning in materials design and discovery: examples from the present and suggestions for the future. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 120301 (2018).

Lookman, T., Balachandran, P. V., Xue, D. & Yuan, R. Active learning in materials science with emphasis on adaptive sampling using uncertainties for targeted design. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 1–17 (2019).

Verduzco, J. C., Marinero, E. E. & Strachan, A. An active learning approach for the design of doped LLZO ceramic garnets for battery applications. Integrating Mater. Manuf. Innov. 10, 299–310 (2021).

Appleton, R. J. et al. Cell relax DFT. https://doi.org/10.21981/PAX3-9Y79 (2022).

Birch, F. Finite elastic strain of cubic crystals. Phys. Rev. 71, 809–824 (1947).

Chen, C., Ye, W., Zuo, Y., Zheng, C. & Ong, S. P. Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chem. Mater. 31, 3564–3572 (2019).

Klimeck, G., McLennan, M., Brophy, S. P., Adams, G. B. III & Lundstrom, M. S. nanoHUB.org: advancing education and research in nanotechnology. Comput. Sci. Eng. 10, 17–23 (2008).

Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018 (2016).

Hunt, M., Clark, S., Mejia, D., Desai, S. & Strachan, A. Sim2Ls: FAIR simulation workflows and data. PLoS ONE 17, e0264492 (2022).

Vanderbilt, D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B 41, 7892–7895 (1990).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Chen, C.-C. et al. How accurate is density functional theory at high pressures?. Comput. Mater. Sci. 247, 113458 (2025).

Ngiam, J. et al. Multimodal deep learning. In Proc. 28th International Conference on Machine Learning 689–696 (Omnipress, 2011).

Kuenneth, C. et al. Polymer informatics with multi-task learning. Patterns 2, 100238 (2021).

Kuenneth, C., Schertzer, W. & Ramprasad, R. Copolymer informatics with multitask deep neural networks. Macromolecules 54, 5957–5961 (2021).

Chen, C., Zuo, Y., Ye, W., Li, X. & Ong, S. P. Learning properties of ordered and disordered materials from multi-fidelity data. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 46–53 (2021).

Appleton, R. J. et al. Multi-task multi-fidelity learning of properties for energetic materials. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 50, e202400248 (2024).

Strachan, A., Chen, C.-C., Appleton, R. J. & Mishra, S. UnderPressure, pressure-induced phase transformations database. https://doi.org/10.21981/ZM8G-1966 (2023).

Andersen, C. W. et al. OPTIMADE, an API for exchanging materials data. Sci. Data 8, 217 (2021).

Andersen, C. et al. The OPTIMADE specification. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12518306 (2024).

Evans, M. L. et al. Developments and applications of the OPTIMADE API for materials discovery, design, and data exchange. Digital Discov. 3, 1509–1533 (2024).

Chen, C. & Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 718–728 (2022).

Qi, J., Ko, T. W., Wood, B. C., Pham, T. A. & Ong, S. P. Robust training of machine learning interatomic potentials with dimensionality reduction and stratified sampling. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 1–11 (2024).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

nanoHUB ResultDB. https://nanohub.org/results (n.d.).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

McMahon, M. I. & Nelmes, R. J. High-pressure structures and phase transformations in elemental metals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 35, 943–963 (2006).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tadano, T. & Tanaka, I. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 35, 353001 (2023).

Togo, A. First-principles phonon calculations with Phonopy and Phono3py. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, 012001 (2023).

Kumar, P. & Adlakha, I. Effect of interstitial hydrogen on elastic behavior of metals: an ab-initio study. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 145, 011003 (2022).

Mishra, P., Kumar, P., Neelakantan, L. & Adlakha, I. First-principles prediction of electrochemical polarization and mechanical behavior in Mg based intermetallics. Comput. Mater. Sci. 214, 111667 (2022).

prnvrvs, prnvrvs/elastic_vasp. https://github.com/prnvrvs/elastic_vasp (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support from the U.S. National Science Foundation FAIROS program (award 2226418) and the computational resources from nanoHUB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-C.C., R.J.A., and A.S.: conceptualization and design of the study. C.-C.C., R.J.A., K.N., and S.M.: construction of the nanoHUB high-pressure DFT tool, CellRelaxDFT. C.-C.C. and R.J.A.: model development, investigation, data analysis, DFT calculations, and writing—original draft. A.S: supervision and writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the review and editing as well as discussions of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, CC., Appleton, R.J., Mishra, S. et al. Discovery of new high-pressure phases – integrating high-throughput DFT simulations, graph neural networks, and active learning. npj Comput Mater 11, 191 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01682-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01682-7