Abstract

Understanding the mechanisms of oxygen anion electrochemical reactions within crystals has long perplexed electrochemical scientists and hindered the structural design and composition optimization of Li-ion cathode materials. Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIP) are transforming the landscape by enabling high-accuracy atomistic modeling on a large scale in materials science and chemistry. The diversity and comprehensiveness of the dataset are fundamental to building a high-accuracy MLIP. Here, we constructed a Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0–1.04) dataset that includes over 15,000 chemical non-equilibrium and chemical equilibrium structures. Using this dataset, we trained an MLIP model (multistate equilibrium potential, named MSEP) with test accuracies of 0.008 eV/atom and 0.153 eV/Å for energy and force, respectively. Through MSEP-MD simulations, we identify a kinetically viable O-redox mechanism in which the formation of transient interlayer O22−, O2− or O3− intermediates drives out-of-plane Mn and Ni migration, resulting in O2 molecules forming within the bulk structure. O3− intermediates have a certain ability to capture O2, which may help alleviate the formation of lattice O2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The electrochemical reaction of oxygen anions plays a key role in enhancing the energy density of traditional Li-ion battery materials. Most experimental studies have focused on particle surfaces, with an emphasis on transient observations. However, capturing the occurrence, dynamic evolution, and oxygen gas precipitation processes of anion reactions within the particle interiors remains a significant challenge. As a result, understanding the mechanisms of oxygen anion electrochemical reactions within crystals has long perplexed electrochemical scientists and hindered the structural design and composition optimization of Li-ion cathode materials. During these electrochemical reactions, variations in electrode potential cause electrode materials to deviate from chemical equilibrium structures, resulting in the formation of numerous chemical non-equilibrium structures. The evolution of these chemical non-equilibrium structures significantly influences the performance, cycle life, and safety of batteries. Therefore, deeply understanding and accurately predicting the behavior of these chemical non-equilibrium structures is crucial for elucidating the mechanisms of oxygen anion electrochemical reactions in crystals. Unfortunately, simulating long-term electrochemical reaction processes and large lattice structures is a computationally prohibitive task for first-principles molecular dynamics simulations.

The recently proposed machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIP), which combine the accuracy of first-principles calculations with the efficiency of molecular mechanics force fields, provide an effective approach for studying the mechanisms of oxygen anion electrochemical reactions within crystals. Among the various MLIPs that have been proposed, including neural network potential (NNP)1, Gaussian approximation potential (GAP)2, moment tensor potential (MTP)3, gradient-domain machine learning (GDML)4, deep potential for molecular dynamics (DeepMD)5, and MACE6, those based on neural networks (NN) stand out. They are particularly advantageous for describing a wide range of chemical systems without requiring additional specialization, making them the best candidates for developing MLIP for Li-ion cathode materials.

Traditionally, the training datasets used to construct MLIP for Li-ion cathode materials have primarily comprised chemical equilibrium structure datasets, such as those from the Materials Project7, AFLOW8, open quantum mechanical database (OQMD)9, and NOMAD10 and so on. While chemical equilibrium structures are essential for understanding the stable configurations of atomic systems, they represent only a fraction of the chemical phenomena that materials can exhibit. The dynamics of chemical reactions, phase transitions, and other critical processes often involve chemical non-equilibrium states, characterized by transient atomic configurations and energy landscapes that differ significantly from chemical equilibrium states. Incorporating chemical non-equilibrium data into machine learning models can greatly enhance our understanding of atomic interactions and improve the predictive accuracy of these models. Therefore, an integrated approach that combines both chemical equilibrium and chemical non-equilibrium data is crucial for developing robust and generalizable MLIP models, ultimately leading to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of Li-ion cathode materials' behavior under diverse conditions.

In this work, we focused on the typical Li-rich cathode material Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 used as a representative system involving electrochemical reactions. We constructed a dataset of battery reaction structures that includes a large number of chemical equilibrium and non-equilibrium structures obtained through two sampling methods: ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) and Metadynamics (MetaD) coupled with AIMD (MetaD and AIMD). Based on these datasets, we trained two MLIP—multistate equilibrium potential (MSEP). Our results show that the model based on the MetaD and AIMD sampling method has test accuracies of 0.008 eV/atom and 0.153 eV/Å for energy and force, respectively, which are higher than the accuracies of 0.016 eV/atom and 0.236 eV/Å obtained by the model based on the AIMD sampling method. Furthermore, the model based on the MetaD and AIMD sampling method demonstrates accuracy in simulating the properties of battery materials that is comparable to the accuracy based on DFT. This indicates that the method is highly reliable for predicting material behavior and performance.

We have used long-time-scale MSEP-MD to identify kinetically viable atomic-scale rearrangements during the first cycle of charge and discharge. We uncovered a kinetically viable O-redox mechanism in which the formation of transient interlayer O22−, O2−, or O3− intermediates drives out-of-plane Mn and Ni migration, resulting in O2 molecules forming within the bulk structure. Additionally, we conducted MSEP-MD simulations on nanoscale Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0 and 0.98) containing grain boundary defects, revealing that O2 molecules primarily formed at the grain boundaries and surfaces initially, and bulk O2 molecules are confined within nanometer-sized (Mn, Ni)-deficient voids.

Results

Chemical non-equilibrium and chemical equilibrium structures dataset

The performance of cathode materials plays a crucial role in determining a battery’s energy density, cycle life, and safety, making it a key factor in enhancing overall battery performance. During charge and discharge cycles, cathode materials undergo electrochemical reactions involving Li-ion de/insertion and electronic transfer. However, these processes also lead to side reactions and structural transformations. As a result, transient structures may form, such as uneven Li-ion distribution or intermediate and transition states related to side reactions. These dynamic, nonequilibrium states significantly affect lithium-ion diffusion, material stability, and overall battery performance, all of which are critical for improving efficiency and extending battery lifespan. Therefore, when designing and optimizing cathode materials, it is essential to consider not only the equilibrium chemical structure but also the behavior and impact of chemical nonequilibrium during cycling.

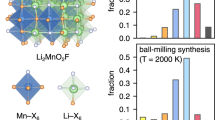

The Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 cathode material has garnered significant research interest as a promising candidate for Li-ion batteries due to its high specific capacity and low cost. However, it is susceptible to considerable oxygen loss and transition metal (TM) migration during charge and discharge cycles, leading to a substantial presence of chemical nonequilibrium structures. This instability may impact the structural integrity of the material, resulting in notable voltage and capacity degradation11,12. We conducted a statistical analysis of both chemical equilibrium and nonequilibrium structures for the Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, 1.04) dataset, generated using AIMD simulations, as illustrated in Fig.1a, b. The results indicate that the data set is distributed over a wide space, with the number of chemical nonequilibrium structures exceeding that of chemical equilibrium structures by more than five times during the electrochemical reaction process (detailed data can be found in Tables S1 and S2). Figure S3 and Table S3 present the statistical count of [OLinTMm] configurations in the cathode material datasets for Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 and Li0.84Mn0.6Ni0.2O2. Notably, the amount of [OLinTMm] (n + m = 6) coordination configurations in the Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 dataset is 5.3 times greater than in the Li0.84Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 dataset. The top five most abundant [OLinTMm] configurations in the Li0.84Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 dataset are all chemical non-equilibrium structures with n + m < 6. Therefore, chemical non-equilibrium structures play a crucial role in the study of battery reaction mechanisms.

a The number of [OLixMnyNi1–x–y] (x and y are atomic ratios) configurations on Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, and 1.04) dataset. b The chemical equilibrium structures and chemical non-equilibrium structures of Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, 1.04) dataset. c The partial chemical equilibrium structures of Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, and 1.04) dataset. d The partial chemical non-equilibrium structures of Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, and 1.04) dataset.

Constructing high-accuracy MLIP is a promising approach to explore battery reaction mechanisms, with the diversity and comprehensiveness of the dataset being crucial for accuracy. Typically, the training set is derived from crystal-derived structures and their MD trajectories. However, MD simulations are constrained by the Boltzmann statistics, which over-represent low-energy regions and can sample only a few distinct configurations separated by low thermal barriers. As a result, a large pool of reference structures is manually selected, which demands expertise, as well as several iterative refinements of MLIP13,14. The MetaD addresses the Boltzmann distribution by accumulating bias potentials along the collective variables (CVs), enabling the sampling of different configurations in high-energy regions. In addition, MetaD is controlled by a few hyperparameters and can start with simple initial structures, requiring less expertise than the conventional MD-based sampling15.

By comparing structural changes in the datasets for Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 and Li0.84Mn0.6Ni0.2O2, we find that the dataset constructed using the combined MetaD and AIMD sampling method exhibits a wider range of variations in cell parameters, as illustrated in Figs. 2a, b and S4. Detailed data can be found in Figs. S5 and S6. This broader configuration space indicates that incorporating MetaD allows the system to capture more phase transitions and structural changes, particularly during the complex chemical reactions involved in the charge and discharge processes of battery materials, compared to using AIMD alone.

a, b The distribution of lattice edge length c and lattice axial angle γ for the Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 datasets. c The model predictions of force on the test dataset compared to DFT calculations. d The model predictions of energy on the test dataset compared to DFT calculations. e The comparison of the MSEP calculated diffusion coefficient and DFT calculated diffusion coefficient on the Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2. f The comparison of MSEP calculated g(r) and DFT calculated g(r) on the Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2.

Furthermore, a comparison of O–O bond lengths highlight the differences in structural sampling between these two methods (detailed data can be found in Figs. S7 and S8). By analyzing the distribution of O–O bond lengths, it can be observed that the combined MetaD and AIMD sampling method not only captures the bond length variations already exhibited in AIMD sampling but also explores more extreme O–O bond length variations. These changes reflect significant adjustments in the relative positions of oxygen atoms under different charge and discharge states. The distribution of O–O bond lengths in MetaD-enhanced sampling show a broader range compared to AIMD, further validating that MetaD can provide a more extensive configuration space, aiding in capturing complex battery reaction mechanisms.

Generation and validation of MSEP

The MSEP potential was obtained by fitting DFT (details can be found in the Methods section) energies and forces of a database containing about 15,512 supercell models (configurations) of Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, and 1.04) by using the DeePMD-kit open-source package16. Among these, the chemical equilibrium structure data included in both the training set and the test set constitute 15% of the total dataset. Additionally, 10% of the data from each of the chemical equilibrium and chemical non-equilibrium structure datasets are randomly selected to form the test set.

Initially, the training set consisted of about 14,312 configurations, which included atomic configurations generated from AIMD trajectories to enhance the description of specific properties, as well as configurations from MetaD simulations17. The database was subsequently expanded through an active learning iterative process with atomic configurations from MSEP-MD trajectories, whose energy was poorly described by earlier versions of the potential. In the final database of about 15,512 configurations, we covered a wide range of thermodynamic conditions, i.e., different temperatures up to 1100 K and diverse lattice parameter distributions (a ≈ 14 Å to 15 Å, b ≈ 7.4 Å to 8.7 Å, c ≈ 14.1 Å to 15.2 Å, α ≈ 89.5° to 94°, β ≈ 85° to 92° and γ ≈ 119.8° to 112°). Details of the configurations in the database under different conditions are reported in Table S5, while information on the MSEP scheme is given in the Methods section. Each configuration corresponds to the DFT energy and forces of Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, and 1.04).

To evaluate the accuracy of the MSEP models based on AIMD sampling and MetaD and AIMD sampling methods, we used a test set containing 1000 structures of Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 randomly divided from a training set of 14312 structures, where the data generated by the MetaD method accounted for 18.2%. As shown in Fig. S9, the root mean square error (RMSE) for the energies of all models is below 0.02 eV/atom, and the RMSE for the forces is around 0.2 eV/Å. To further validate the generalization and optimize the performance of the models, five rounds of active learning were conducted for different MSEP models based on AIMD sampling and MetaD and AIMD sampling methods. In each round, four models for each sampling method were trained, and these four MSEP models were used for MD simulations at 300 K with a time step of 0.02 fs for 2 ps to sample structures. The four models were then used to predict the sampled structures, and 240 structures with model prediction deviations between 0.1 eV/Å and 0.3 eV/Å were randomly selected for DFT single-point energy calculations. These structures were added to the training set for the next round of MSEP model training. As shown in Fig. S10, starting from the third round, the MSEP models based on the MetaD and AIMD sampling methods achieved an energy MAE below 0.02 eV/atom and a force MAE below 0.24 eV/Å, outperforming the MSEP models based on AIMD sampling. However, it was observed that the MAE for forces oscillated around 0.2 eV/Å for the MSEP models developed using both sampling methods. We further divided the samples of Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 with different delithiation ratios (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, and 1.04) into separate test sets to evaluate the generalization ability and cross-validation performance of the MSEP model. As shown in Fig. S11, the test results demonstrate that the MAE for energy and force remain consistently stable around 0.01 eV/atom and 0.2 eV/Å, respectively, across varying compositions. To understand the cause of this oscillation, we performed a statistical analysis of the test set, as shown in Fig. S12. The results indicate that specific atoms may be subjected to complex interactions, leading to significant inaccuracies in force predictions for some atoms, however, 85.7% of the total oxygen atoms exhibited an MAE in force below 0.1 eV/Å, while the average force error for oxygen atoms remained consistently around 0.1 eV/Å across all categories.

The distributions of MSEP errors on energies and forces are given in Fig. 2c, d. The energy MAE between the DFT calculated values and those predicted by the MSEP potential with AIMD sampling methods is 0.016 eV/atom for the test set, and the MAE on forces is 0.236 eV/Å for the test set. In contrast, for the MSEP potential based on the combined MetaD and AIMD sampling methods, the energy MAE is significantly lower at 0.008 eV/atom, with a force MAE of 0.153 eV/Å for the test set. For multi-component systems like ours, the RMSE of the energy obtained using DeePMD ranges from about 0.01–0.02 eV/atom, and the RMSE of the force from about 0.04–0.25 0.04 eV/Å18,19,20,21.

The MSEP potential has been validated through diffusion coefficient D and radial distribution function (g(r)) calculations of the Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 as described in Figs. 2e, f and S13–S15, the diffusion coefficient is obtained by utilizing the Arrhenius relation, while the activation energy Ea is a by-product of the fitting process. All the MSEP-MD simulations were performed with the LAMMPS code22, NVT simulations were conducted at temperatures of 1000 K, 1143 K, 1333 K, and 1600 K with the Nosé–Hoover thermostat23,24,25. Through MSEP-MD simulations, we can effectively predict the structural and dynamical properties of materials, with the diffusion coefficient D of Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 being consistent with results from DFT calculations. This indicates that the MSEP potential has high accuracy in capturing complex interactions. The simulated radial distribution function also matches the DFT results closely, demonstrating the model’s reliability in describing local structural features. Figure S16 shows the consistency between the MSEP calculated voltage curve and experimental first-cycle charging voltage curve, X-ray diffraction (XRD) calculated values, and experimental values, further validating the accuracy of the MSEP potential.

Kinetics of oxygen anion in crystal structural transformation

Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 is a typical TM oxide-based material that achieves higher energy and power density compared to traditional lithium layered oxides (LiTMO2) due to additional reversible redox of lattice oxygen26,27. To understand the first-cycle behavior of Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 in the oxygen-redox regime, we simulated the charging process of Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 beyond the conventional TM redox limit by removing lithium ions, resulting in a composition of Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2. When relaxed using DFT, this delithiated structure appears stable with respect to structural rearrangement, with no observed Mn and Ni rearrangement or oxygen dimerization (Fig. 3b). This absence of structural rearrangements is an artifact of this DFT relaxation approach, which yields a structure trapped in a local minimum. This DFT-relaxed delithiated structure, however, is unstable with respect to structural rearrangement over experimental timescales28,29.

a The change in total energy with Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 from 1200 ps MSEP-MD simulations at 300 K, with indicated positions showing structures that were extracted for further analysis. The shaded region shows the range of the fluctuations of total energy, and the orange line indicates the energy averaged with a 1 ps time window. b Optimized DFT equilibrium geometry of the structures extracted from I–IV. c The change in the total energy for DFT geometry relaxations of structures I–IV plotted as a function of the MSEP-MD simulation time.

To identify kinetically accessible structural rearrangements, we performed room-temperature MSEP-based molecular dynamics simulation by heating metastable Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 to 300 K and running the simulation at that temperature for 1200 ps. Using MSEP-MD provides an unbiased search for structural rearrangements that selects for kinetically viable rearrangement pathways. For structures obtained from this MSEP-MD trajectory that displayed oxygen dimerization or TM ion migration, we performed full relaxations using higher-accuracy DFT calculations to evaluate whether these rearrangements are thermodynamically favored. For Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0.22, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, and 0.84), the relevant results are provided in Fig. S18–S23 and Tables S8 and S9. The study indicates that prior to Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2, MSEP-MD simulations did not observe TM ion migration or oxygen dimerization formation.

Applying this procedure to delithiated Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 (Fig. 3a), our studies reveal that O ions in O–(Mn, Ni)2 sites are preferentially oxidized, leading to the formation of interlayer O2−, O22−, and O3− species in adjacent TM layers (Fig. 3b, structure II). Once these O atoms form O2−, O22−, and O3− species, their bonding interactions with neighboring TM ions decrease (Figs. S27–S29). This reduction in bonding drives the migration of Ni and Mn into the interlayer space, occurring through hops to first or second-neighbor sites. Over longer timescales (~1000 ps), three Mn ions and two Ni ions migrate into the interlayer space, resulting in the formation of more O₂ molecules and O2−, O22−, and O3− species (structure III-IV). The oxygen stability of Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 was characterized by in situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) tests, where the irreversible O2 evolution under high-voltage conditions during the initial charging process was monitored and quantified (Fig. S16c).

This process is kinetically viable and contributes to the overall thermodynamic stabilization of the system, with structure IV being approximately 9 eV per cell more stable than the initial structure I (Fig. 3c). O–O dimerization requires an interlayer distance between O atoms of <1.5 Å. This is achieved by a rippling of the TM layers that gives a local contraction of the space between them, even while the average interlayer spacing and c lattice parameter are not substantially changed (Table S7 and Figs. S25 and S26).

To understand the first-cycle behavior of Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2under oxygen redox states, we simulated the discharge process of Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 again. By applying the principle of energy minimization, lithium ions were progressively added, and the kinetic simulation conditions were kept consistent with the charging process. For example, Fig. 4a, c, and d show the optimized DFT equilibrium geometry and MSEP-MD simulation results for Li0.36Mn0.6Ni0.2O2. From Fig. 4b, d–j and Tables S14 and S15, it can be seen that O3− first transforms into lattice O and O2− or O22−, most of the formed O2− and O22− returned to the lattice, but a small amount of O2− and O22− could not return, especially those formed in the TM layers. This indicates that O3− has a certain ability to capture O2, which may help alleviate the formation of lattice O2.

a The change in total energy with Li0.36Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 from 1200 ps MSEP-MD simulations at 300 K, with indicated positions showing structures that were extracted for further analysis. The shaded region shows the range of the fluctuations of total energy, and the orange line indicates the energy averaged with a 1 ps time window. b Optimized DFT equilibrium geometry of the Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 structures extracted from the initial and after 1200 ps MSEP-MD simulation. c The change in the total energy for DFT geometry relaxations of Li0.36Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 structures I–IV plotted as a function of the MSEP-MD simulation time. d Optimized DFT equilibrium geometry of the Li0.36Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 structures extracted from I (initial) and IV (after 1200 ps MSEP-MD simulation). e–h Optimized DFT equilibrium geometry of the Li0.49Mn0.6Ni0.2O2, Li0.71Mn0.6Ni0.2O2, Li0.93Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 and Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 structures extracted from after 1200 ps MSEP-MD simulation. i The bond length of O2− or O22− species of LixMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0.22, 0.36, 0.49, 0.71, 0.98, and 1.2). j, The bond length of O3− species of LixMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0.22, 0.36, 0.49, 0.71, 0.98, and 1.2).

In addition, based on the crystal structure after the first cycle, we performed a charge process simulation for the second cycle. As shown in Fig. S17, the voltage curve calculated by DFT based on the rearranged structure following MSEP-MD simulation exhibited excellent consistency with the experimental charging curve. Since some O2−, O22−, and O3− species do not fully revert to lattice oxygen after the first cycle, some electrochemically active sites are permanently deactivated, leading to capacity fading. The irreversible oxygen redox behavior also alters the local charge distribution around the TM centers, thereby increasing the potential required for subsequent charging reactions and even eliminating the characteristic voltage plateau, ultimately resulting in voltage decay.

TM migration and structural degradation in Li-rich cathodes have previously been attributed to lattice strain between Li2MnO3 and LiTMO2 domains30. Our results suggest that there is a driving force for both TM migration into the Li layer and structural degradation, regardless of the presence of nanodomains. Structural degradation is initiated by oxidized framework O atoms and proceeds if the TM layers can separate to allow the formation of interlayer O2− or O22−. Consequently, preventing the formation of interlayer O2− or O22− is probably an effective strategy for improving the kinetic stability of the TM layers against rearrangement. This might be achieved by increasing the spacing between layers with ‘pillaring’ cations or by including large interlayer ions, such as for Na-ion cathodes31.

Nanoscale mechanisms of oxygen redox at grain boundaries

Defect structures are a crucial factor influencing the electrochemical performance of electrode materials in lithium batteries. Different types of defects can exert different influences on the electrochemical performance of electrode materials32,33. In contrast to point defects, the distribution of planar defects such as grain boundaries, stacking faults, and coherent twin boundaries is less homogeneous and depends largely on the variation in their thermodynamic state34,35. Therefore, there are only a limited number of studies that explore the phenomenon and mechanism of planar defects, as well as effective approaches to control them in electrode materials36,37.

In lithium-rich cathode materials, grain boundary defects are the predominant defect type in this system38,39. Therefore, to accurately represent the bulk structure, we utilized Atomsk software40 to construct a nanoscale-featured model with planar defects, which is a Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 structure containing 45,000 atoms (Fig. 5a). This model is several orders of magnitude larger than what can be achieved with pure DFT methods. We performed room-temperature Molecular Simulation via MSEP-MD by heating metastable Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 to 300 K and maintaining that temperature for 3000 fs. This simulation predicts local phase segregation behavior, leading to the formation of regions rich in (Mn, Ni)Ox and nanoscale voids containing O2 molecule, O22−, O2− or O3− ions (Figs. 5 and S30–S32 and Tables S10 and S13). Approximately 5% of the O atoms in the system form O2 molecules. O₂ molecules formed at grain boundaries are likely to escape immediately, as this pathway represents the lowest energy state. For the grain boundaries of Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2, stacking fault and edge dislocation of Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2, the relevant results are provided in Figs. S33–S37 and Tables S10–S13. Studies indicate that at grain boundaries of Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2, the formation of O2 molecules is almost negligible, while a small amount of (O22−, O2−, O3−) is formed. Conversely, at stacking faults and edge dislocations of Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2, the formation of O2 molecules, O22−, O2−, and O3− occurs.

a, b The analysis of O distribution in Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 with MSEP-MD simulation at different times. A 2D representation of the void network, showing the O atoms in the O2 molecule, O22−, O2− or O3− ions only. c The analysis of the O coordination environments in Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2. d A 2D representation of the void network, showing the O3− ions only.

Discussion

In conclusion, the cathode reaction process involves numerous chemical non-equilibrium structures. By combining MetaD and AIMD sampling methods, we constructed a Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, and 1.04) dataset that includes over 15,000 chemical non-equilibrium and chemical equilibrium structures. Based on this dataset, we trained an MSEP model with test accuracies of 0.008 eV/atom and 0.153 eV/Å for energy and force, respectively. The MSEP model allows for the simulation of electrochemical reactions in real-structure electrode materials, facilitating detailed atomic-level investigations of Li-rich O redox cathodes. We identify a kinetically viable O-redox mechanism in which the formation of transient interlayer O22−, O2−, or O3− intermediates drives out-of-plane Mn and Ni migration, resulting in O2 molecules forming within the bulk structure. O3− intermediates have a certain ability to capture O2, which may help alleviate the formation of lattice O2. Additionally, we conducted MSEP-MD simulations on nanoscale Li1.2–xMn0.6N0.2O2 (x = 0 and 0.98) containing grain boundary defects, revealing that O2 molecules primarily formed at the grain boundaries initially, and bulk O2 molecules are confined within nanometer-sized (Mn, Ni)-deficient voids.

Methods

First-principles computation

The MSEP potential was obtained by fitting DFT energies and forces of a database containing about 15512 supercell models (configurations) of Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 with varying delithiation levels by using the DeePMD-kit open-source package16. All DFT calculations were performed with the projector augmented wave (PAW) method41,42 in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)43. To obtain more accurate oxidation DFT energies, the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof form (PBE) exchange-correlation function with Hubbard U correction for TM (Mn = 3.9 eV, Ni = 6.2 eV)44 was applied. The convergence criteria are 10-5 eV for total energy and 0.001 eV/Å for force. To construct initial Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 configurations for first-principles calculations, the special quasi-random structures (SQS) module based on a Monte Carlo algorithm in the ATAT software package was employed45,46 For Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2, a 5 × 4 × 2 supercell based on the primitive unit cell of the rock-salt structure was employed, containing 180 atoms. Based on the above parameters, the calculated primitive cell structure parameters and voltage curve are in agreement with experimental measurements (Figs. S1 and S2).

Neural network architecture

In constructing the MSEP potential, we employed two-body embedding descriptors47 with a distance cutoff of 8 Å. The embedding network has 3 hidden layers with 25, 50, and 100 neurons for the two-body descriptors. Finally, the network for the fitting of energy and forces consists of 3 hidden layers with 240, 240, and 240 neurons. In the embedding and fitting network, we have used the hyperbolic tangent as an activation function. We have also exploited the residual neurons48. The hyperparameters which control the learning process16 are reported in Table S4.

AIMD simulation

AIMD simulations were performed using non-spin-polarized, an electronic energy convergence cut-off of 10−6 eV, a Γ-centered 1 × 1 × 1 k-point mesh, and a time step of 3 fs. The PBE functionals by GGA were adopted as in the “First-principles computation” section. The supercell model consists of Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 bulk-phase with 1 × 1 × 1 conventional unit cells (180 atoms) and delithiated structures Li0.84Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 (164 atoms), Li0.71Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 (158 atoms), Li0.62Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 (154 atoms), Li0.49Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 (148 atoms), Li0.36Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 (142 atoms), Li0.22Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 (136 atoms) and Li0.16Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 (133 atoms). To obtain the initial dataset, AIMD simulations were performed at temperatures of 250 K, 300 K, 350 K, 500 K, 700 K, 900 K, and 1100 K following static relaxation of the initial structures. The simulations utilized an NVT ensemble with a Nosé–Hoover thermostat for 30 ps. We sampled one structure every 100 fs from 10,000 frames and performed single-point energy calculations for each.

MSEP-MD simulations

To further enhance the accuracy of MSEP potential, we employed the committee voting mechanism of dpgen49, utilizing an active learning process involving four independent MSEP potentials. Specifically, LAMMPS22 simulations were conducted using four distinct training models to randomly select structures with force prediction errors in the range of 0.1 eV/Å to 0.3 eV/Å. These identified structures underwent DFT calculations (calculation parameters can be found in the “First-principles computation” section) to acquire precise data, which were subsequently incorporated into the training set for MSEP potential retraining. The above process was carried out for 5 rounds, with 240 new structures added in each round. Finally, all the data was used to train the final model.

MLIP-MD simulations were performed in the NVT ensemble based on the MSEP potential. For all MLIP-MD simulations, the temperature was maintained at 300 K using the Nosé–Hoover thermostat23,24. Each simulation ran for 1000 MD steps (2 ps) with a time step of 0.002 ps. Snapshot configurations were taken every 0.02 ps, yielding 100 snapshots for each phase of the materials. Finally, we exploited the Ovito50 tool for the visualization and the generation of all atomic snapshots of this manuscript.

MetaD simulations

For all MetaD simulations of Li1.2–xMn0.6Ni0.2O2 (x = 0, 0.36, 0.49, 0.58, 0.71, 0.84, 0.98, and 1.04), we utilized the meta-structure prediction algorithm module of the crystal structure prediction software USPEX17. The Gaussian height was constrained to 16,000, and the Gaussian width to 0.7. The minimum lattice constant was set at 5, and the maximum at 15. Each generation of structures was produced by combining genetic algorithms (40%), random generation (20%), lattice deformation (20%), and atomic movement (20%) to generate the next generation of structures, each generation explores 5 structures, simulating for 5 generations, and stops when the structures no longer change, yielding approximately 13 initial unit cells for each material. Our test results indicate that the non-equilibrium structures generated within the distribution ranges of the aforementioned MetaD parameter values for the lattice edge lengths (a, b, c) and lattice axial angles (α, β, γ) exhibit a high degree of robustness and reproducibility. The detailed data can be found in Figs. S38–S41 as supplementary information.

The structures generated by the MetaD simulations were subsequently subjected to AIMD simulations. These simulations employed an NVT ensemble, regulated by a Nosé–Hoover thermostat, for a duration of 30 ps. We sampled one structure every 900 fs from the total of 10,000 frames, performing single-point energy calculations for each sampled structure. All resultant data were then incorporated into the training dataset.

Material synthesis

The material was synthesized via a sol-gel method. The required amounts of lithium acetate (4% excess), manganese acetate, and nickel acetate were dissolved in deionized water. Citric acid was mixed with deionized water in a separate beaker to act as a complexing agent (the molar ratio of citric acid to metal ions was 1:1). The metal ion solution was then added dropwise to the citric acid solution. After stirring for 1 h, the solution was heated in an oil bath at 80 °C for 12 h until a gel phase was formed. The obtained gel was placed in an oven and evaporated at 120 °C for 12 h to get a dried gel. The dried gel was ground into powder and sintered at 450 °C for 6 h and then at 900 °C for 12 h to obtain the target products.

Electrochemical measurements and physicochemical characterizations

The cathode electrode was prepared by mixing the active material with Super C65 and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) at a weight ratio of 8:1:1 in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). The electrolyte solution was 1 M LiPF6 in a 1:1 mixture of ethylene carbonate (EC) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC), and lithium metal foil was used as the anode. Glass fiber (Whatman) was used as the separator. Coin cells were assembled in a dry Ar-filled glovebox and cycled on a LAND CT-3002A workstation at 25 °C. The in-situ cell for DEMS testing was assembled in the Ar-filled glovebox. The loading density of the cathode was approximately 6 mg cm-2. High-purity argon was used as the carrier gas during cycling. The crystal structures of materials were examined by powder XRD (Bruker D8 Advance) using Cu Kα radiation at a scanning speed of 2° min−1. The XRD Rietveld refinement was implemented by the GSAS-2 program.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

LAMMPS and DeePMD are free and open source codes available at https://lammps.sandia.gov and http://www.deepmd.org, respectively.

References

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Bartók, A. P., Payne, M. C., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. Gaussian approximation potentials: the accuracy of quantum mechanics, without the electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136403 (2010).

Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: a class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. Multiscale Model. Simul. 14, 1153–1173 (2016).

Chmiela, S. et al. Machine learning of accurate energy-conserving molecular force fields. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603015 (2017).

Zhang, L., Han, J., Wang, H., Car, R. & E, W. Deep potential molecular dynamics: a scalable model with the accuracy of quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 143001 (2018).

Batatia, I., Kov'acs, D. a. P. e., Simm, G. N. C., Ortner, C. & Csányi, G. MACE: higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. In 36th Conference on NeurIPS. Vol. 830, 11423–11436 (2022).

Jain, A. et al. The Materials Project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Curtarolo, S. et al. AFLOWLIB.ORG: a distributed materials properties repository from high-throughput ab initio calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 58, 227–235 (2012).

Kirklin, S. et al. The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD): assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. npj Comput. Mater. 1, 15010 (2015).

Draxl, C. & Scheffler, M. The NOMAD laboratory: from data sharing to artificial intelligence. J. Phys. Mater. 2, 036001 (2019).

Liu, S. N. et al. Ti-doped Co-free Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 cathode materials with enhanced electrochemical performance for lithium-ion batteries. Inorganics 12, 88 (2024).

Puheng, Y. et al. Self-standing Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2/graphene membrane as a binder-free cathode for Li-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 8, 39769–39776 (2018).

Rowe, P., Deringer, V. L., Gasparotto, P., Csányi, G. & Michaelides, A. An accurate and transferable machine learning potential for carbon. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 034702 (2020).

Botu, V., Batra, R., Chapman, J. & Ramprasad, R. Machine learning force fields: construction, validation, and outlook. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 511–522 (2017).

Yoo, D., Jung, J., Jeong, W. & Han, S. Metadynamics sampling in atomic environment space for collecting training data for machine learning potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 131 (2021).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Han, J. & E, W. DeePMD-kit: a deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Niu, H., Niu, S. & Oganov, A. R. Simple and accurate model of fracture toughness of solids. J. Appl. Phys. 125, 065105 (2019).

Zhang, R. et al. Theoretical study on ion diffusion mechanism in W-doped K3SbS4 as solid-state electrolyte for K-ion batteries. Inorg. Chem. 63, 6743–6751 (2024).

Wang, F. et al. Atomic-scale simulations in multi-component alloys and compounds: a review on advances in interatomic potential. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 165, 49–65 (2023).

Ryltsev, R. E. & Chtchelkatchev, N. M. Deep machine learning potentials for multicomponent metallic melts: development, predictability and compositional transferability. J. Mol. Liq. 349, 118181 (2022).

Gubaev, K. et al. Finite-temperature interplay of structural stability, chemical complexity, and elastic properties of bcc multicomponent alloys from ab initio trained machine-learning potentials. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 073801 (2021).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Nosé, S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 511–519 (1984).

Hoover, W. G. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A 31, 1695–1697 (1985).

Lin, A. M., Shi, J., Wei, S. H. & Sun, Y. Y. Comparative study of nudged elastic band and molecular dynamics methods for diffusion kinetics in solid-state electrolytes. Chin. Phys. B 33, 086601 (2024).

Ding, X. et al. An ultra-long-life Lithium-rich Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 cathode by three-in-one surface modification for Lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 7778–7782 (2020).

Cui, Q., Li, Y., Li, Y., Qiu, W. & Liu, J. Structural design principle of rocksalt oxides for Li-excess cathode materials. ACS Nano. 18, 2302–2311 (2024).

Eum, D. et al. Coupling structural evolution and oxygen-redox electrochemistry in layered transition metal oxides. Nat. Mater. 21, 664–672 (2022).

McColl, K., Coles, S. W., Zarabadi-Poor, P., Morgan, B. J. & Islam, M. S. Phase segregation and nanoconfined fluid O2 in a lithium-rich oxide cathode. Nat. Mater. 23, 826–833 (2024).

Liu, T. et al. Origin of structural degradation in Li-rich layered oxide cathode. Nature 606, 305–312 (2022).

House, R. A. et al. The role of O2 in O-redox cathodes for Li-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 6, 781–789 (2021).

Wang, R. et al. Twin boundary defect engineering improves lithium-ion diffusion for fast-charging spinel cathode materials. Nat. Commun. 12, 3085 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Revealing the degradation pathways of layered Li-rich oxide cathodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 1821–1830 (2024).

Singer, A. et al. Nucleation of dislocations and their dynamics in layered oxide cathode materials during battery charging. Nat. Energy 3, 641–647 (2018).

Eum, D. et al. Electrochemomechanical failure in layered oxide cathodes caused by rotational stacking faults. Nat. Mater. 23, 1093–1099 (2024).

Gong, Y. et al. In situ atomic-scale observation of electrochemical delithiation induced structure evolution of LiCoO2 cathode in a working all-solid-state battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4274–4277 (2017).

Sharifi-Asl, S. et al. Revealing grain-boundary-induced degradation mechanisms in Li-rich cathode materials. Nano Lett. 20, 1208–1217 (2020).

Sharifi-Asl, S. et al. Revealing grain boundary induced degradation mechanisms in Li-rich cathode materials. Nano Lett. 20, 1208–1217 (2020).

Nie, A. et al. Twin boundary assisted lithium ion transport. Nano Lett. 15, 610–615 (2015).

Hirel, P. Atomsk: a tool for manipulating and converting atomic data files. Comput. Phys. Commun. 197, 212–219 (2015).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Wang, L., Maxisch, T. & Ceder, G. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA+U framework. Phys. Rev. B 73, 195107 (2006).

Zhou, K. et al. Tailoring the redox-active transition metal content to enhance cycling stability in cation-disordered rock-salt oxides. Energy Storage Mater. 43, 275–283 (2021).

van de Walle, A. et al. Efficient stochastic generation of special quasirandom structures. Calphad 42, 13–18 (2013).

Lu, D. et al. 86 PFLOPS deep potential molecular dynamics simulation of 100 million atoms with ab initio accuracy. Comput. Phys. Commun. 259, 107624 (2021).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. IEEE CVPR 7780459, 770–778 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. DP-GEN: a concurrent learning platform for the generation of reliable deep learning based potential energy models. Comput. Phys. Commun. 253, 107206 (2020).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the open visualization tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB3807200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China, NSFC (22133005, 22403103), the Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M723276 and GZB20230793), Sponsored by the Shanghai Sailing Program (23YF1454900), and the Shanghai Post-doctoral Excellence Program (2022660).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.R. designed and completed the entire project. N.R. wrote the manuscript. C.L. assisted in analyzing data. Q.C. designed the experiments. J.L. and D.X. supervised, discussed, and revised the manuscript. J.L. and N.R. provided funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ran, N., Li, C., Cui, Q. et al. Dynamic oxygen-redox evolution of cathode reactions based on the multistate equilibrium potential model. npj Comput Mater 11, 208 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01714-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01714-2