Abstract

Chemical short-range order (SRO) affects the distribution of elements throughout the solid-solution phase of metallic alloys, thereby modifying the background against which microstructural evolution occurs. Investigating such chemistry–microstructure relationships requires atomistic models that act at the appropriate length scales while capturing the intricacies of chemical bonds leading to SRO. Here, we consider various approaches for the construction of training data sets for machine learning potentials (MLPs) for CrCoNi and evaluate their performance in capturing SRO and its effects on materials quantities of relevance for mechanical properties, such as stacking-fault energy and phase stability. It is demonstrated that energy accuracy on test sets often does not correlate with accuracy in capturing material properties, which is fundamental in enabling large-scale atomistic simulations of metallic alloys with high physical fidelity. Based on this analysis, we systematically derive design principles for the rational construction of MLPs that capture SRO in the crystal and liquid phases of alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In high-entropy alloys (HEAs)1,2,3, multiple metallic elements are combined in nearly equal concentrations. This often leads to the stabilization of crystalline phases in which elements are distributed throughout the alloy in a nearly random fashion—namely, solid solution phases. This class of alloys has attracted substantial interest due to their mechanical properties. For example, extraordinary fracture resistance was observed in CrCoNi4,5 as the result of an unusual synergy of deformation mechanisms involving stacking-fault formation and phase transitions, as well as the conventional gliding of dislocations.

It has been established that chemical short-range order (SRO)—i.e., the tendency of solid solutions to not be completely random—affects various chemistry–microstructure relationships that influence mechanical properties. For example, SRO has been shown to affect dislocation mobility6,7,8, grain boundaries9,10,11, stacking-fault energy12,13,14,15, and phase stability16. Consequently, significant experimental efforts have been made to characterize SRO and its effects on materials properties11,13,14,17,18,19,20,21,22. Connecting computational results to such experiments requires high-fidelity physical models capable of capturing the intricate nature of chemical bonds leading to SRO, while also accounting for the complexity of chemical motifs in HEAs23,24,25.

In a previous work (ref. 23), we have demonstrated that small-scale atomistic simulations, i.e., sizes typical of density-functional theory (DFT) calculations, are inadequate to properly capture SRO, leading to errors of up to 25% in the prediction of Warren–Cowley parameters. In the same work, an approach for training machine learning interatomic potentials (MLPs) was demonstrated to capture SRO while simultaneously leading to an improvement in energy accuracy when compared to the state-of-the-art. Yet, fundamentally, such an approach consisted of a set of heuristics on the construction of the MLP, i.e., a reasonable and practical approach for the construction of training sets without rigorous justification. Here, we build on these results and systematically derive the design principles for the rational construction of MLPs that capture SRO.

While much of the work on MLPs for HEAs has focused on their energy accuracy over test data sets7,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38, here we focus instead on their performance in reproducing SRO and its effects on materials quantities of relevance for mechanical properties. We systematically augment an initially simple MLP training set while tracking the associated effects on the SRO of the crystal and liquid phases, stacking-fault energy, and phase stability. It is demonstrated that energy accuracy on test data sets often does not correlate with accuracy in capturing such material properties, which are fundamental in enabling large-scale atomistic simulations of HEAs with high physical fidelity.

Results

Training strategy to manage chemical complexity

In order to develop the design principles for capturing SRO, we focus on the face-centered cubic (fcc) solid-solution phase of the paradigmatic CrCoNi alloy4,5,6,12,13,14,21,39,40,41,42. The MLP model chosen is the Moment Tensor Potential (MTP)26 with a radial cutoff of 5 Å, which corresponds to a distance between the 3rd and 4th coordination shell of CrCoNi. In the absence of any other criteria to guide our initial choice of ML model, we have chosen to employ MTP due to its superior performance in energy and force errors for single-element systems compared to other MLP models (as demonstrated by an independent assessment in ref. 43). An a posteriori analysis described in Supplementary Section 1 shows that MTP also has superior performance for various material properties of the CrCoNi alloy when compared to a few other ML models.

In ref. 23, we demonstrated that the first coordination shell in CrCoNi can be chemically decorated in 36,333 unique configurations (i.e., chemical motifs). The relative energy of these chemical motifs affects the frequency with which they are observed in the alloy—which is the fundamental origin of SRO—making this an important property to be reproduced by MLPs in order to capture SRO. Yet, while the first coordination shell is the dominating term in atomic interactions, many-body contributions from higher coordination shells are not negligible and must be accounted in the development of MLPs26,27,28,44,45,46. Extending the counting of unique chemical motifs to the second and third coordination shells results in ~2.5 × 107 and 6.8 × 1018 unique motifs, respectively. Comparing these numbers with the 651 independent parameters of the MLP model with the highest capacity employed here makes it clear that the chemical complexity of this magnitude leads to a landscape with many nearly degenerate minima for the MLP fitting. Here, this chemical complexity is considered by employing an ensemble training approach23,33,35: multiple potentials are fitted under identical training conditions. Variations in performance among the resulting potentials due to the nearly degenerate minima landscape are explicitly evaluated against materials properties related to SRO, including the role of the model capacity (i.e., number of independent parameters).

In the following sections, we gradually build towards a final training set by systematically augmenting an initially simple training set while evaluating the effect of the modifications on associated material properties. In order to focus on the role of chemical complexity, we employ a standard approach for accounting for thermal vibrations and thermal expansion in all potentials (described in the “Methods” section). Throughout this process, the performance is also compared to a benchmark training set referred to as “TS-0”, which was first introduced in ref. 23 as “training set without chemical sampling”. This training set was built by adapting the popular approach introduced in ref. 36 for bcc NbMoTaW to CrCoNi, which includes perfect and distorted ground state structures, slab structures, and molecular dynamics structures spanning single-element, binary, and ternary element systems. While the approach in ref. 36 was not developed with the intent of capturing SRO; it is one of the most comprehensive and popular approaches for constructing training sets for HEAs7,37, which warranted its choice as a benchmark data set.

Chemical SRO in the crystal phase

Quantification of SRO in the crystalline phase can be performed by evaluating the Warren–Cowley (WC) parameters:

where i and j refer to any of the three chemical elements in the alloy, ci is the average concentration of i-type atoms, and p(i∣j) is the conditional probability of finding a i-type atom in the first coordination shell of an j-type atom. The effectiveness of MLPs in capturing SRO will be quantified by comparing WC parameters against those obtained through DFT Monte Carlo simulations. In Fig. 1a, we show that a popular interatomic potential6 (embedded-atom model, or EAM) for CrCoNi is not capable of reproducing WC parameters. Similarly, TS-0 also falls short of reproducing DFT results within the statistical accuracy, despite resulting in a considerable improvement in comparison with EAM.

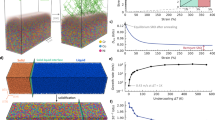

a Comparison of predicted WC parameters (Eq. (1)) against DFT Monte Carlo (literature values from refs. 12,42). The EAM potential is from ref. 6, while the training sets for potentials TS-0, TS-1, and TS-2 are summarized in Table 1. Error bars are the standard error of the mean from an ensemble of 20 independent potentials. b Illustration of the intermediary configurations extracted from DFT Monte Carlo to train TS-2. c Relative error with respect to DFT (Eq. (2)) as a function of the MLP model capacity. Error bars are the 95% confidence interval from an ensemble of 20 independent potentials.

We turn now to the construction of our initial training set, named TS-1. This training set is composed of chemically random and equiatomic fcc supercells with 108 atoms, adding up to 54,540 atoms (as summarized in Table 1). Despite its simplicity, it is clear from Fig. 1a that TS-1 outperforms TS-0 for all WC parameters, which can only be attributed to the more extensive sampling of the chemical space performed in TS-1 when compared to TS-0. Despite this encouraging result, note once again that the chemical space is enormous compared to the number of independent parameters in the MLP model. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that sampling the chemical space with an approach that is better than random will lead to improved performance. We propose to accomplish this by substituting the chemically random configurations of TS-1 with intermediary configurations from DFT Monte Carlo simulations, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. We name this training set TS-2. The configurations along the Monte Carlo trajectory exhibit an increasing amount of SRO with small energetic differences among them, all associated with changes in local chemical motifs. They function as a guide for the MLP, nudging it to capture the most relevant regions of the chemical space (i.e., regions that show up frequently due to SRO, as shown in refs. 23,47), as well as the trajectory to arrive at SRO from an initially random solid solution. It can be seen in Fig. 1a that TS-2 is able to reproduce all WC parameters predicted by DFT within the statistical accuracy.

The performance of each MLP in Fig. 1a can be summarized by evaluating the relative error with respect to DFT:

This relative error is shown in Fig. 1c for all three training sets as a function of the MLP model capacity (i.e., number of independent parameters), where it can be seen that the observations above regarding the superior performance of TS-2 relative to TS-0 and TS-1 hold for any model capacity. More importantly, note how TS-2 has significantly more stable behavior against random weight initialization for training, which is shown in Fig. 1c by an ensemble standard deviation of 3% at levmax = 20 compared to 29% for TS-0 and 13% for TS-1. Given the simplicity and similarity of the training sets for TS-1 and TS-2, this smaller variation within the ensemble can only be attributed to the extensive chemical sampling and the targeted sampling of motifs of relevance for SRO.

Liquid stability and SRO

The liquid phase is also afflicted by the considerable chemical complexity observed in the crystal phase. The concept of SRO becomes even more complex in the liquid because chemical and structural SRO are both present. This can be observed in the partial radial distribution functions (pRDFs) obtained from DFT molecular dynamics simulations at 2684 K, shown in Fig. 2a: the Cr–Cr and Cr–Co peaks are notably lower than other peaks, indicating that these chemical pairs are energetically unfavorable (i.e., chemical SRO). An entanglement between chemical and structural SRO leads to the variations of the first coordination shells in Fig. 2a.

a Partial radial distribution function (pRDF) of the liquid phase at 2684 K from DFT. b Comparison of pRDF using TS-3 (colored lines) against DFT values (black lines). c Relative error with respect to DFT (Eq. (3)) in the prediction of structural and chemical SRO in the liquid as a function of MLP model capacity. d Fraction of potentials in the ensemble with a stable liquid phase. Blue bars are for TS-0 and pink bars are for TS-3. e Distribution of nearest-neighbor distance for each atom in TS-0 and TS-3. Inset shows the breakdown of nearest-neighbor distance in TS-3 by phase. The success of TS-3 in reproducing a stable liquid phase is attributed to the inclusion of crystal configurations with atom pairs at much closer distances than TS-0.

The effects observed in Fig. 2a are addressed by augmenting TS-2 with configurations obtained from DFT molecular dynamics simulations of the liquid phase at 1800 K. The resulting training set—named TS-3 and summarized in Table 1—is able to capture the chemical and structural SRO of the pRDFs, as shown in Fig. 2b: the first coordination shell peak heights are in agreement within ± 4.9%, while the major discrepancy in the first coordination shell peak location being −0.12 Å for Cr–Cr pairs.

The performance in capturing chemical and structural SRO in the liquid can be summarized by evaluating the relative error in the absolute differences between the pRDFs with respect to DFT, similarly to what was done for the WC parameters in Eq. (2):

where gij(r) is the pRDF between chemical elements i and j, and \({r}_{\max }=3.5\) Å is the extension of the first coordination shell (i.e., total RDF minimum between first and second peaks), which was chosen to evaluate only the short-range part of chemical and structural ordering. Using this approach one can see in Fig. 2c that TS-3 has better performance than TS-0, which is unexpected because TS-0 is trained with configurations extracted from the same simulation employed to collect the pRDF statistics in Fig. 2b (i.e., at 2684 K) while TS-3 configurations were collected at 1800 K. Notice that one is unable to detect this performance difference in reproducing materials properties by evaluating only the energy root-mean-square error: TS-0 and TS-3 result in 5.3 and 5.6 meV/atom, respectively, at 1800 K, and 7.6 and 6.6 meV/atom at 2684 K.

Another important consequence of chemical complexity is the fact that a large fraction of the ensemble of MLPs obtained with TS-0 were unstable in the liquid phase, i.e., simulations of the liquid phase with these potentials quickly encountered configurations with unphysically large values for forces and energies that led the simulation to fail. Notice that this behavior is observed despite the inclusion of liquid configurations in the training set of TS-0 potentials. The fraction of potentials in the ensemble with unstable liquid phase is shown in Fig. 2d as a function of the model capacity. Note how for levmax = 12 and 14, only one out of the five potentials trained is stable. In the same figure, it can be seen that TS-3 never results in such instabilities.

We were able to track down the source of TS-3 success in stabilizing the liquid to the inclusion of crystal configurations with atomic pair distances much closer together than those observed in TS-0, as can be seen in the histogram of Fig. 2e (see Supplementary Section 2 for a detailed breakdown of this analysis). This observation is explained by further considering the role of chemical complexity as follows. Despite its disordered structure, the liquid has well-defined structural SRO48,49 (e.g., the three coordination shells clearly visible in Fig. 2b), leading to a similar degree of chemical complexity as the crystalline phase23. Yet, differently from the crystalline phase, atoms in the liquid are frequently diffusing around, which requires going through activated transition states with higher potential energy due to the close proximity of atoms50,51. Such transition states are considered “rare events” in the course of a simulation, such as the ones used to extract configurations for TS-0 and TS-3, because they occur only every many timesteps for each atom. It is suspected that the inclusion of crystal configuration with close pair distances (Fig. 2e) in TS-3 induces the learning of the energetics of such transition states in between chemical motifs, rendering the liquid phase stable.

Stacking-fault energy and phase stability

Mechanical properties of fcc alloys are closely linked to the (111) stacking-fault energy (γsf) and the relative stability of the fcc phase with respect to the hexagonal close-packed (hcp) phase52,53,54 (ΔE = Efcc−Ehcp). For example, engineering of phase metastability with ΔE enables transformation-induced plasticity55, while lowering γsf is associated with a change in plasticity mechanism from dislocation slip to twinning. Notably, the exceptional damage tolerance4 of CrCoNi is the result of an unusual synergy between the deformation mechanisms described above.

Figure 3 shows that TS-0 is not capable of reproducing γsf or ΔE. Our strategy for capturing these two quantities with MLPs is centered around the well-established correlation between them: a fcc-to-hcp transition can be accomplished by the successive introduction of stacking faults on every other (111) plane. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that training with configurations of one of these structures (i.e., stacking faults or hcp) is enough to learn the other. We chose to employ hcp configurations instead of stacking faults because they are straightforward to simulate. Two training sets were created to compare the performance of MLPs trained with and without hcp configurations. The first training set (TS-4) includes only fcc configurations and is similar to TS-2 in all aspects except for its total size, which is reduced by 32.7% with respect to TS-2 (as shown in Table 1). This reduction is performed with the goal of accommodating an equivalent amount of hcp configurations in the second training set (TS-5), thereby achieving parity between fcc and hcp configurations while maintaining a moderate training set total size. With TS-4 and TS-5 we seek to establish the importance of hcp configurations in capturing γsf and ΔE; the liquid phase was intentionally left out of both training sets (i.e., TS-4 and TS-5) to avoid interference with this test.

Comparison of γsf and ΔE against DFT results for a random solid solutions and b solid solutions in thermal equilibrium (i.e., with appropriate SRO as obtained through Monte Carlo simulations). The blue arrow indicates the improvements in both quantities by augmenting TS-4 with hcp configurations. Error bars are the standard error of the mean from independent Monte Carlo simulations. Figures at the bottom indicate the density distribution of γsf due to chemical fluctuations and SRO.

Figure 3a compares γsf and ΔE against DFT for a random solid solution at 500 K, where it can be seen that the introduction of the hcp phase is fundamental in capturing the correct value of γsf and ΔE. Yet, SRO in CrCoNi leads to an increase in γsf12; thus, we also compare γsf and ΔE for a solid solution in thermal equilibrium at 500 K in Fig. 3b. While the agreement in Fig. 3b might seem obvious in light of Fig. 3a, we warn that such anticipation is not warranted. Figure 3b is a much more stringent test than simply capturing the energetics of stacking faults and crystalline phases, which MLPs are well-known to be capable of capturing56,57,58,59,60. Instead, Fig. 3b demonstrates that TS-5 is capable of capturing the correct SRO and its effects on materials properties (i.e., γsf and ΔE). This is because independent Monte Carlo simulations for thermal equilibration were performed in each case (DFT, TS-4, and TS-5), leading to independent predictions of SRO configurations, which were then employed to evaluate γsf and ΔE.

Final training set

A final training set (TS-f) is constructed (see Table 1) to incorporate all elements leading to good performance on capturing SRO and its effects on the crystal phase, liquid phase, stacking faults, and phase stability. Its performance across the various material properties is evaluated through the following metric:

where \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{fcc}}}^{{\rm{SRO}}}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{hcp}}}^{{\rm{SRO}}}\) are the relative WC errors (Eq. (2)) for the fcc and hcp phases, \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{liquid}}}^{{\rm{pRDF}}}\) is shown in Eq. (3), and εenergy is the energy root-mean-square error over a test set with a wide range of configurations, including random solid phases, thermally equilibrated solid solutions, and liquid phases (see the “Methods” section for a full description). The combined error metric εMLP is defined as the product of individual errors to fairly propagate relative uncertainties across different material properties while avoiding dependence on arbitrary normalization. The εMLP error as a function of the computational cost for different model capacities is shown in Fig. 4 along with the Pareto front. The large variation in εMLP performance within an ensemble with the same model capacity (i.e., number of independent parameters) is noteworthy (note the log-scale in the y-axis). For example, the best performing MLP with levmax = 14 has εMLP comparable to the second best out of the five MLPs in the ensemble with levmax = 20, despite the latter being ≈3.6 times more computationally expensive. Moreover, note how the potential with the lowest εenergy is often not the best performing potential for materials properties: εenergy only predicts the best performance in two out of the eight ensembles in Fig. 4.

The best performing potential for a fixed computational cost falls on the Pareto front. Blue rectangles mark ensembles of identically trained potentials for different model capacities (i.e., \({{\rm{lev}}}_{\max }\)). Potentials with the lowest root-mean-square energy error (εenergy) within each ensemble are marked in green. The four ensembles on the left have levmax = 6, 8, 10, and 12. A breakdown of the MLP performance across individual error metrics is provided in Supplementary Section 3.

Material properties with size-converged SRO

Equipped with TS-f we now turn to demonstrate the effect of SRO on properties and scales that cannot be achieved in the absence of the MLP introduced here. We start by reproducing the observation, made in ref. 23, that DFT-sized calculations are not converged with respect to size and produce relative errors up to 40% in SRO because the SRO characteristic length scale can be as large as 25–30 Å. This can be seen in Fig. 5a, where the relative error of WC parameters with respect to a large calculation with 10,976 atoms is shown as a function of system size. Systems with as many as 2000 atoms (or, equivalently, linear dimensions of 28 Å) are required for size convergence, while DFT calculations for SRO investigations in the literature use one order of magnitude less atoms12,42. We further demonstrate here that similar size convergence is necessary for predicting material properties strongly influenced by SRO. As illustrated in Fig. 5c and d, DFT-size simulations yield significant errors of 10.7 mJ/m2 in stacking fault energy (γSF) and 2.84 meV/atom in phase stability (ΔE) under thermal equilibrium (i.e., with appropriate SRO as obtained through Monte Carlo simulations).

a Relative error of WC parameters with system size (εsize), measured similarly to Eq. (2) but against the largest size prediction. Simulations with <2000 atoms are not converged with respect to system size. b Temperature dependence of WC parameters (Eq. (1)). c Temperature dependence of stacking-fault energy (γsf) for a random solid solution and a solid solution in thermal equilibrium (i.e., with appropriate SRO as obtained through Monte Carlo simulations). The “DFT-size” data point was evaluated with TS-f, but using a system with only 180 atoms, which is the typical size of DFT calculations (as indicated in Fig. 5a). d Temperature dependence of the fcc-hcp phase stability. See text for a full discussion of the effect of SRO and the phase transition at low temperatures leading to the kink at 600 K for solid solutions in thermal equilibrium.

The temperature dependence of the WC parameters was evaluated with calculations converged with respect to system size. Figure 5b shows that in general the WC parameters decrease in magnitude as the temperature increases, but this behavior is not monotonous for αCoCo, where an increase in magnitude with temperature is observed above 900 K. This is yet another evidence of the incompleteness of WC parameters in quantifying SRO: in ref. 23 we demonstrate that an appropriate and complete SRO metric shows smooth monotonic decrease in SRO with temperature.

The stacking-fault energy (γsf) dependence on temperature is also not trivial, as shown in Fig. 5c. Short-range order increases γsf at all temperatures with respect to a random solid solution, which is aligned with previous results12. This observation can be rationalized by the fact that stacking-fault creation in a thermally equilibrated solid solution requires the disruption of chemical motifs with lower energy than those encountered in a random solid solution. Yet, while the temperature effect on random solid solutions is a simple linear increase in γsf (due to thermal expansion), a solid solution in thermal equilibrium (i.e., with appropriate SRO as obtained through Monte Carlo simulations) presents a complicated interplay between SRO and temperature. At low temperatures, the contribution from SRO dominates and γsf decreases almost linearly with temperature, but as temperature increases above around 800 K, γsf displays a linear increase with temperature almost in parallel with the random solid solution. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the complex temperature dependence of γsf, despite its central role in rationalizing many of the mechanical properties of CrCoNi and other fcc HEAs.

The fcc-hcp relative phase stability (ΔE) is also evaluated with TS-f, as shown in Fig. 5d. In general, the presence of SRO further stabilizes the hcp phase at all temperatures, i.e., increases ΔE with respect to the random solid solution. Yet, the absolute value of ΔE decreases with increasing temperature, in agreement with previous first-principles calculations and thermodynamic models61,62, indicating that the fcc phase becomes the stable phase near the melting temperature16. At low temperatures, ΔE has a kink near 600 K for solid solutions in thermal equilibrium that is not present in random solid solutions, which is consistent with previous findings32,33,63 indicating a potential phase transition to an ordered phase at low temperatures.

Finally, the melting temperature of TS-f was evaluated using phase-coexistence molecular dynamics simulations. The agreement with experimental results is excellent, as shown in Table 2, and a marked improvement over existing interatomic potentials6.

Discussion

The most important design principle supported by the results presented here is that chemical complexity should be sampled extensively and biased towards chemical motifs of relevance for SRO. As shown in Fig. 1c, this is the most effective strategy to reduce the impact of the nearly-degenerate landscape of minima on MLP fitting, on which all other principles rely to perform well in capturing materials properties. A promising venue to amplify the benefits of this design principle will be its combination with compressed lower-dimensional descriptors of chemical information64,65,66,67,68, which were developed to alleviate the dramatic increase in MLP capacity required to accommodate an increasing number of chemical species. Since this design principle addresses chemical complexity, it is fully compatible with existing methods that optimize structural sampling and thermal fluctuations69,70.

Quantitative experimental characterization of SRO has not yet been achieved14,22,71,72,73, and the feasibility of employing SRO as a design feature for materials properties remains uncertain. In light of these observations, it is justifiable to question the relevance of SRO in the field of HEAs. One argument for its relevance is the potential ubiquity of SRO in various material properties and phenomena, as highlighted in ref. 63 by historical results in metallurgy and a review of the fundamental principles of clustering in simpler alloys. The results presented here introduce another argument for the relevance of SRO: the importance of chemical complexity in the development of high-fidelity atomistic physical models for solid solutions, as exemplified by the following design principles: the liquid phase is only rendered stable (Fig. 2) after careful consideration of its structural and chemical SRO and the inclusion of solid configurations with close atomic pair distances, which ought to also affect the solidification process (Table 2) and as-cast state of these alloys. Similarly, the stacking-fault energy and phase stability (Fig. 3) are only captured within DFT accuracy after accounting for chemical SRO equally in both fcc and hcp phases.

The results obtained here highlight the importance of modeling SRO at the appropriate length scales. The observation that DFT-sized calculations do not converge with respect to SRO (i.e., Fig. 5a) was first made in ref. 23. Yet, here we note that size convergence with respect to SRO is also important for properties such as stacking-fault energy (Fig. 5c) and fcc-hcp relative phase stability (Fig. 5d). Large-scale simulations dramatically reduce the uncertainty in the estimation of γsf—which has its origins in the chemical complexity (Fig. 3)—and reveal in Fig. 5c that γsf is negative at all temperatures. This observation supports the argument proposed in ref. 74 that positive stacking-fault free energy is the likely explanation for finite partial-dislocation separations observed experimentally.

In conclusion, our work introduces a series of design principles for the construction of training data sets that optimize MLP performance in capturing SRO and its effects on important materials properties, such as phase stability and defect energies. The effectiveness of each design principle is confirmed by comparing the performance of MLPs trained with and without the proposed approaches in reproducing associated material properties. A final training set that includes all proposed principles is produced, and its performance across various materials properties is evaluated and summarized in a single metric (Eq. (4)), thereby enabling large-scale atomistic simulations of CrCoNi and other HEAs with high physical fidelity75. These design principles are readily generalizable to other material systems of different chemistries and structures, including ordered compounds76,77,78,79 and systems with defects75. The primary remaining challenge is the high computational cost of dataset generation, which we aim to mitigate in future work.

Methods

Density-functional theory calculations

All DFT calculations were performed with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof80 exchange-correlation functional and projector-augmented wave81 pseudopotentials as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP82,83,84,85,86) version 6.2.1. The pseudopotentials employed (version potpaw.PBE.54) were such that the valence electrons of Cr, Co, and Ni were 3p63d54s1, 3d84s1, and 3d84s2, respectively. All DFT calculations were spin-polarized (collinear) with an initial magnetic moment configuration of 0.6μB, 2.0μB, and 1.0μB for Cr, Co, and Ni, respectively (μB is the Bohr magneton).

Separate convergence tests were performed for the energy cutoff of the plane-wave basis set, Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid density, and width value for Methfessel–Paxton smearing. The energy cutoff was varied from 180 to 520 eV at intervals of 10 eV, the k-point grid varied from 3 × 3 × 3 to 14 × 14 × 14, and the smearing width was varied from 0.03 to 0.2 eV. Convergence tests were performed iteratively until the per-atom energy was within 3 meV/atom of the best set of parameters employed, except for the smearing width convergence, where the criterion was a per-atom entropic energy contribution below 1 meV/atom. The converged set of parameters was: energy cutoff of 430 eV for all elemental systems, k-point grid of 6 × 6 × 6 for a fcc unit cell, and second-order Methfessel–Paxton smearing with a width value of 0.1 eV. The energy threshold for self-consistency and the force threshold for structure relaxation were 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV/Å, respectively.

The k-point grid for structures other than simple unit cells were scaled proportionally, e.g., k-point grid was 3 × 3 × 3 for a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell. For slab structures the k-point grid was 8 × 2 × 1, where the surface normal is along \(\hat{{\bf{z}}}\). A single Γ k-point was employed for Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations, but the configurations included in the training set of MLPs had their energy and forces recalculated with the optimal k-point density obtained during convergence tests.

Molecular dynamics simulations in the canonical ensemble employed a Langevin thermostat coupled with a Parinello–Rahman barostat with a friction coefficient γ = 10 p s−1 for all atom species and lattice degree-of-freedom. All structure manipulations, visualizations, and analyses of simulations were carried out with the Python interface of Ovito87 and the Python Materials Genomics (Pymatgen)88 library. Automation of calculations was performed with the Fireworks software89.

MLP model training

The MLP model chosen for all potentials discussed here is the Moment Tensor Potential26. The Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb-Shanno algorithm90 was employed to optimize the cα parameters, which map the invariant basis polynomials Bα(u) to the DFT energies and forces. The cutoff radius hyper-parameter was rcut = 5 Å and a Chebyshev radial basis of size 8 Å was employed for all models, while \({{\rm{lev}}}_{\max }\) was varied from 6 to 20 to investigate the effects of model capacity. The energy and force data weights were set to 1 and 0.01, respectively. Training was carried out for a maximum of 10,000 iterations with a tolerance of 10−5 for the relative error with respect to the 50th previous iteration. All MLP simulations were performed with the large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS91).

Training and test sets

In this section, we describe the data sets summarized in Table 1.

Training set TS-0 was introduced in ref. 23, where it was named “training set without chemical sampling”. The full description of TS-0 can be found in Section 3A of the supplementary material of ref. 23, here we provide a brief summary of its content. The atomic configurations in TS-0 include: single-element ground states and distorted structures, surface slabs with different orientations, and molecular dynamics simulations at different temperatures (including above the melting temperature), random binary systems with various compositions, and special quasi-random structures (SQS92,93) of ternary ab initio molecular dynamics simulations at different temperatures (including above the melting temperature).

Training set TS-1 is composed of chemically random and equiatomic fcc 3 × 3 × 3 cubic supercells with 108 atoms and orthogonal axes, aligned with \(\left\langle 100\right\rangle\) directions. A total of 505 such supercells were employed, adding up to 54,540 atoms in the data set. The effects of thermal expansion and thermal noise were accounted for by employing a strategy developed in our previous work23,94, as described next. Starting from the 0 K lattice constant (3.526 Å), each supercell was isotropically expanded to account for thermal expansion effects by assuming a linear thermal expansion coefficient of 1.56 × 10−5 K−1, which corresponds to 3% total expansion at the average melting temperature \(\left\langle {T}_{{\rm{m}}}\right\rangle =({T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{{\rm{Cr}}}+{T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{{\rm{Co}}}+{T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{{\rm{Ni}}})/3=1917\,{\rm{K}}\). Half of the supercells were isotropically expanded to their corresponding lattice parameters at 300 K, and the other half to \(0.9\left\langle {T}_{{\rm{m}}}\right\rangle\). Thermal noise was accounted for by randomly displacing each atom. The displacements were sampled from a uniform distribution within a sphere as follows. The maximum possible displacement of each atom is αdnn/2, where dnn/2 is half of the nearest neighbor distance and α controls the thermal-noise magnitude for the corresponding supercell. For 75% of the supercells α was evenly sampled in the interval [0.01, 0.30) to replicate low-temperature thermal vibrations, while the remaining 25% supercells had α ∈ [0.30, 0.55) to account for thermal vibrations near the melting temperature.

Training set TS-2 creation followed the exact same strategy as TS-1, except for employing chemical configurations extracted from Monte Carlo simulations instead of the chemically random configurations of TS-1. The Monte Carlo95 simulations started from chemically random structures with 0 K lattice parameter (3.526 Å) and ran for a total of 5000 atom-swap attempts at a temperature of 500 K. Five independent simulations were performed and 101 configurations evenly spaced in intervals of 50 steps were extracted from each for the creation of TS-2.

Training set TS-3 augments TS-2 by including configurations obtained from a molecular dynamics simulation of the liquid phase of CrCoNi at 1800 K and zero external pressure. The simulation was set up by randomly adding 72 atoms to a cubic box with an average volume per atom of 14.83 Å3 and a restriction on the minimum interatomic distance of 2.11 Å to avoid the overlapping of atoms. The simulation ran for 80 ps with a timestep of 3 fs; after 3 ps of equilibration a total of 752 snapshots were extracted at intervals of 75 fs. Note that TS-3 was introduced in ref. 23, where it was named “training set with chemical sampling”.

Training set TS-4 was created identically to TS-2, except that the fcc supercells now contain 144 atoms with the 500 K lattice constant (3.545 Å), and have orthogonal axes aligned with the [110], \([1\bar{1}2]\), and \([1\bar{1}\bar{1}]\) directions. Configurations were extracted in intervals of 100 steps for each of the five independent Monte Carlo simulations, adding up to 255 supercells or 36,720 atoms.

Training set TS-5 augments TS-4 with hcp supercells with chemical configurations extracted along five independent Monte Carlo simulations in intervals of 100 steps. The axis rotation performed in TS-4 relative to TS-2 permits us to collect the same number of supercells (255) and atoms (36,720) for the hcp phase as the fcc phase in TS-4. The Monte Carlo simulations started from chemically random structures with a = 2.507 Å (\(c=\sqrt{8/3}a\)) and ran for a total of 5000 atom-swap attempts at a temperature of 500 K. The hcp supercells undergo the same treatment as TS-1 to account for thermal vibrations and thermal expansion.

Training set TS-f was obtaining by augmenting TS-5 with atomic configurations from the liquid phase extracted from the same molecular dynamics simulation performed for TS-3, except that a total of 1020 configurations were extracted such that TS-f is balanced with respect to the number of liquid configurations (73,440) and crystal configurations (73,440, evenly split between the fcc and hcp phases).

The test set employed to compute ϵenergy (Eq. (4) and Fig. 4) was introduced in ref. 23. Its full description can be found in Section 3C of the Supplementary material of ref. 23, here we provide a brief summary of its content. This test set includes configurations and thermodynamic conditions not employed in any of the training sets above. For clarity, we divide the set into three groups. The “random solid solution” configurations included only chemically random CrCoNi supercells with various degrees of thermal noise and thermal expansion. The “thermally equilibrated solid solution” configurations included chemical ordering extracted along DFT Monte Carlo simulations at 750 and 1200 K with thermal noise and thermal expansion. Finally, the “liquid” snapshots were extracted from ab initio molecular dynamics simulations at 2684 K.

MLP Monte Carlo simulations

The MLP and EAM Monte Carlo simulations95 for Fig. 1 were identical to the DFT Monte Carlo simulations: they started from chemically random configurations and ran at 500 K for a total of 5000 steps for a supercell with 108 atoms and a lattice parameter of 3.526 Å. The Warren–Cowley parameters (Eq. (1)) are computed by averaging over the final 100 steps of each simulation. A total of 18 independent Monte Carlo simulations were performed for each of the 20 MLPs in the ensemble of each \({{\rm{lev}}}_{\max }\) to evaluate the standard error of the mean and confidence intervals shown in Fig. 1.

The MLP Monte Carlo simulations for Fig. 3 started from random chemical configurations, ran for a total of 55 steps per atom, and employed the same lattice parameters as the DFT Monte Carlo simulations for TS-4. A total of 108 independent Monte Carlo simulations were performed.

The MLP stacking-fault energy in Fig. 3 is evaluated using supercells with 180 atoms and the same lattice parameter as employed in the DFT evaluation of γsf. Figure 3a employed 108 chemically random configurations, while Fig. 3b employed only the last configuration extracted from 108 independent Monte Carlo simulations. In both cases, only a single intrinsic stacking fault is introduced in each of the 108 supercells.

The MLP Monte Carlo simulations for Fig. 5 started from random chemical configurations, ran for a total of 30 steps per atom, and employed lattice parameters that account for the thermal expansion at the associated simulation temperature. All data in Fig. 5 employed levmax = 20. The size-convergence in Fig. 5a was performed for n × n × n fcc supercells from n = 3 (108 atoms) to n = 14 (10,976 atoms). The temperature dependence of SRO states in Fig. 5b was assessed using 40 independent Monte Carlo simulations with 4000 atoms (orthogonal axis aligned with \(\left\langle 100\right\rangle\) directions) for 300–1700 K in 100 K intervals. The temperature dependence of material properties in Fig. 5c and d was evaluated with 10 independent Monte Carlo simulations with 8316 atoms for each temperature and each phase (i.e., fcc and hcp), with orthogonal axes aligned with the [110], \([1\bar{1}2]\), and \([1\bar{1}\bar{1}]\) directions for the fcc phase.

MLP liquid molecular dynamics

The MLP molecular dynamics simulations for Fig. 2a–c started from the last snapshot of the DFT simulation employed in TS-0 (at 2684 K with 72 atoms). A Nosé–Hoover thermostat and barostat were used to maintain the temperature at 2684 K and zero hydrostatic pressure for 25,000 steps with a step size of 3 fs. The element-wise partial radial distribution functions were evaluated with the configurations from the last 20,000 steps.

The liquid phase stability (Fig. 2d) was evaluated with simulations of 4000 atoms. The simulation box was a cube with edge length of 39 Å inside which the atoms were randomly distributed such that no pair of atoms was closer than 1.7 Å to avoid overlap. After relaxing the structure for 100 steps, the system was maintained at 2684 K for 20,000 steps of size 2.5 fs using a Nosé–Hoover thermostat and barostat. An MLP model is marked as having a stable liquid phase if no critical failure is encountered during this simulation.

Stacking-fault energy and fcc-hcp phase stability

The (111) stacking-fault energy (γsf) was computed as follows. The periodic boundary conditions along the \([1\bar{1}\bar{1}]\) direction are removed from supercells of the fcc phase with orthogonal axes aligned with the [110], \([1\bar{1}2]\), and \([1\bar{1}\bar{1}]\) directions. This structure is then relaxed by minimizing the potential energy at fixed volume while keeping atoms in the top and bottom close-packed planes fixed. An intrinsic stacking fault is then introduced between two \((1\bar{1}\bar{1})\) planes, which is followed by another identical structural relaxation. The γsf is evaluated by computing the energy of the relaxed structures before and after the introduction of the stacking fault and dividing the difference by the supercell cross-sectional area along \([1\bar{1}\bar{1}]\).

The DFT stacking-fault energy in Fig. 3 is evaluated using supercells with 144 atoms from the five independent Monte Carlo simulations performed for TS-4. The stacking-fault energy is evaluated for all six \((1\bar{1}\bar{1})\) planes in the final configuration of each Monte Carlo simulation.

The MLP stacking-fault energy in Fig. 3 is evaluated using supercells with 180 atoms and the same lattice parameter as employed in the DFT evaluation of γsf. Figure 3a employed 108 chemically random configurations, while Fig. 3b employed only the last configuration extracted from 108 independent Monte Carlo simulations. In both cases, only a single intrinsic stacking fault is introduced in each of the 108 supercells.

The temperature dependence of γsf for TS-f with levmax = 20 in Fig. 5c is performed using a size-converged system of 8316 atoms with 18 \((1\bar{1}\bar{1})\) planes. The stacking-fault energy is evaluated for each \((1\bar{1}\bar{1})\) plane in the final configuration of 10 independent Monte Carlo simulations.

The difference in energy per atom between the fcc and hcp phases (ΔE = Efcc−Ehcp) is evaluated by first performing a structural relaxation (i.e., energy minimization) at fixed volume before evaluating the energies. The comparison with DFT in Fig. 3 is performed with a total of 108 supercells of 180 atoms. Meanwhile, the temperature dependence of ΔE for TS-f with levmax = 20 in Fig. 5d is evaluated using a size-converged system of 8316 atoms from 10 independent Monte Carlo simulations.

Melting temperature calculation

The melting temperature in Table 2 was computed using the phase-coexistence method96 as follows. The initial crystal–liquid interface structure had 196,608 atoms, with 25% of atoms in a 16 × 16 × 16 fcc slab with orthogonal axis aligned with the \([1\bar{1}2]\), \([1\bar{1}\bar{1}]\), and [110] directions at the center of the simulation box. The remaining 75% of atoms are randomly placed (i.e., liquid phase) within the empty space above and below the fcc slab, sharing the same x−y plane with [110] normal. The initial simulation dimensions are such that both the equilibrium fcc lattice constant and average liquid density at the corresponding temperature are employed, resulting in a box size of 70.8, 100.1, and 337.1 Å. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all directions.

This crystal–liquid system is equilibrated by first relaxing the liquid atoms' coordinates for 100 steps while keeping the solid atoms fixed. This is followed by 2 ps of equilibration of the crystal slab with a Nosé–Hoover thermostat at 0.95 × the target temperature, and a subsequent 2 ps equilibration of the liquid region at the target temperature. Finally, the liquid region is equilibrated for 2 ps at the target temperature with a Nosé–Hoover barostat to maintain zero pressure along the direction perpendicular to the crystal–liquid interface.

The phase-coexistence simulation is carried out for 300 ps with a timestep of 2 fs. A Nosé–Hoover thermostat and barostat were used to control the temperature and maintain zero pressure along the direction perpendicular to the crystal–liquid interface (the directions parallel to the interface are kept constant). To avoid drifting of the center-of-mass, the total linear momentum is zeroed every 2 ps, and the temperature is calculated by excluding the center-of-mass velocity. The phase-coexistence simulation is performed at various temperatures uniformly distributed along a 100 K window around the estimated melting temperature with 10 K increments. For each temperature, the interface velocity is measured by estimating the rate at which liquid atoms transform into solid atoms according to the polyhedral template matching87,97 approach with a root-mean-square deviation cutoff of 0.15. After an initial 20 ps of equilibration, the total number of atoms in the liquid phase is collected every 2 ps. The melting temperature is estimated as the temperature at which the crystal–liquid interface velocity is zero.

Data availability

All potentials, data sets, and codes to replicate each figure of this paper can be downloaded from ref. 98.

Code availability

Any custom code that is not currently available in the repository list can be subsequently added upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Yeh, J.-W. et al. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6, 299–303 (2004).

Cantor, B., Chang, I., Knight, P. & Vincent, A. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 375, 213–218 (2004).

George, E. P., Raabe, D. & Ritchie, R. O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 515–534 (2019).

Liu, D. et al. Exceptional fracture toughness of CrCoNi-based medium- and high-entropy alloys at 20 kelvin. Science 378, 978–983 (2022).

Gludovatz, B. et al. Exceptional damage-tolerance of a medium-entropy alloy CrCoNi at cryogenic temperatures. Nat. Commun. 7, 10602 (2016).

Li, Q. J., Sheng, H. & Ma, E. Strengthening in multi-principal element alloys with local-chemical-order roughened dislocation pathways. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–11 (2019).

Yin, S. et al. Atomistic simulations of dislocation mobility in refractory high-entropy alloys and the effect of chemical short-range order. Nat. Commun. 12, 4873 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. Short-range ordering alters the dislocation nucleation and propagation in refractory high-entropy alloys. Mater. Today 65, 14–25 (2023).

McCarthy, M. J. et al. Emergence of near-boundary segregation zones in face-centered cubic multiprincipal element alloys. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 113601 (2021).

Aksoy, D. et al. Chemical order transitions within extended interfacial segregation zones in NbMoTaW. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 235302 (2022).

Cao, P. Maximum strength and dislocation patterning in multi-principal element alloys. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq7433 (2022).

Ding, J., Yu, Q., Asta, M. & Ritchie, R. O. Tunable stacking fault energies by tailoring local chemical order in CrCoNi medium-entropy alloys. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 8919–8924 (2018).

Zhang, R. et al. Short-range order and its impact on the CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Nature 581, 283–287 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Evolution of short-range order and its effects on the plastic deformation behavior of single crystals of the equiatomic Cr–Co–Ni medium-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 243, 118537 (2023).

Zhao, S., Stocks, G. M. & Zhang, Y. Stacking fault energies of face-centered cubic concentrated solid solution alloys. Acta Mater. 134, 334–345 (2017).

Niu, C., LaRosa, C. R., Miao, J., Mills, M. J. & Ghazisaeidi, M. Magnetically-driven phase transformation strengthening in high entropy alloys. Nat. Commun. 9, 1363 (2018).

Xu, M., Wei, S., Tasan, C. C. & LeBeau, J. M. Determination of local short-range order in TiVNbHf(Al). Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 181901 (2023).

Schönfeld, B. et al. Local order in Cr–Fe–Co–Ni: experiment and electronic structure calculations. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014206 (2019).

Inoue, K., Yoshida, S. & Tsuji, N. Direct observation of local chemical ordering in a few nanometer range in CoCrNi medium-entropy alloy by atom probe tomography and its impact on mechanical properties. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 085007 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Direct observation of chemical short-range order in a medium-entropy alloy. Nature 592, 712–716 (2021).

Zhou, L. et al. Atomic-scale evidence of chemical short-range order in CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 224, 117490 (2022).

Coury, F. G., Miller, C., Field, R. & Kaufman, M. On the origin of diffuse intensities in fcc electron diffraction patterns. Nature 622, 742–747 (2023).

Sheriff, K., Cao, Y., Smidt, T. & Freitas, R. Quantifying chemical short-range order in metallic alloys. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2322962121 (2024).

Sheriff, K., Cao, Y. & Freitas, R. Chemical-motif characterization of short-range order with e(3)-equivariant graph neural networks. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 215 (2024).

Sheriff, K., Cao, Y. & Freitas, R. Section 12—capturing chemical complexity in high-entropy materials. Roadmap for the Development of Machine Learning-based Interatomic Potentials. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 33, 023301 (2025).

Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: a class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. Multiscale Model. Simul. 14, 1153–1173 (2016).

Thompson, A., Swiler, L., Trott, C., Foiles, S. & Tucker, G. Spectral neighbor analysis method for automated generation of quantum-accurate interatomic potentials. J. Comput. Phys. 285, 316–330 (2015).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Bartók, A. P., Payne, M. C., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. Gaussian approximation potentials: the accuracy of quantum mechanics, without the electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136403 (2010).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Musaelian, A. et al. Learning local equivariant representations for large-scale atomistic dynamics. Nat. Commun. 14, 579 (2023).

Du, J.-P. et al. Chemical domain structure and its formation kinetics in CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 240, 118314 (2022).

Ghosh, S., Sotskov, V., Shapeev, A. V., Neugebauer, J. & Körmann, F. Short-range order and phase stability of CrCoNi explored with machine learning potentials. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 113804 (2022).

Kostiuchenko, T., Körmann, F., Neugebauer, J. & Shapeev, A. Impact of lattice relaxations on phase transitions in a high-entropy alloy studied by machine-learning potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 1–7 (2019).

Kostiuchenko, T., Ruban, A. V., Neugebauer, J., Shapeev, A. & Körmann, F. Short-range order in face-centered cubic VCoNi alloys. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 113802 (2020).

Li, X.-G., Chen, C., Zheng, H., Zuo, Y. & Ong, S. P. Complex strengthening mechanisms in the NbMoTaW multi-principal element alloy. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 70 (2020).

Zheng, H. et al. Multi-scale investigation of short-range order and dislocation glide in MoNbTi and TaNbTi multi-principal element alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 89 (2023).

Yu, P., Du, J.-P., Shinzato, S., Meng, F.-S. & Ogata, S. Theory of history-dependent multi-layer generalized stacking fault energy—a modeling of the micro-substructure evolution kinetics in chemically ordered medium-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 224, 117504 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Effect of local chemical order on the irradiation-induced defect evolution in CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218673120 (2023).

Walsh, F., Asta, M. & Ritchie, R. O. Magnetically driven short-range order can explain anomalous measurements in CrCoNi. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2020540118 (2021).

Zhang, F. X. et al. Local structure and short-range order in a nicocr solid solution alloy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 205501 (2017).

Tamm, A., Aabloo, A., Klintenberg, M., Stocks, M. & Caro, A. Atomic-scale properties of Ni-based FCC ternary, and quaternary alloys. Acta Mater. 99, 307–312 (2015).

Zuo, Y. et al. Performance and cost assessment of machine learning interatomic potentials. J. Phys. Chem. A 124, 731–745 (2020).

Behler, J. Neural network potential-energy surfaces in chemistry: a tool for large-scale simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 17930–17955 (2011).

Bartók, A. P., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. On representing chemical environments. Phys. Rev. B 87, 184115 (2013).

Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion for accurate and transferable interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014104 (2019).

McCarthy, M. J., Startt, J., Dingreville, R., Thompson, A. P. & Wood, M. A. Atomic representations of local and global chemistry in complex alloys. arXiv:2303.04311 (2023).

Di Cicco, A., Trapananti, A., Faggioni, S. & Filipponi, A. Is there icosahedral ordering in liquid and undercooled metals? Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 135505 (2003).

Jónsson, H. & Andersen, H. C. Icosahedral ordering in the Lennard–Jones liquid and glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2295 (1988).

Freitas, R. & Reed, E. J. Uncovering the effects of interface-induced ordering of liquid on crystal growth using machine learning. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–10 (2020).

Schoenholz, S. S., Cubuk, E. D., Sussman, D. M., Kaxiras, E. & Liu, A. J. A structural approach to relaxation in glassy liquids. Nat. Phys. 12, 469–471 (2016).

Zhang, Z. et al. Dislocation mechanisms and 3D twin architectures generate exceptional strength–ductility–toughness combination in CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Nat. Commun. 8, 14390 (2017).

Miao, J. et al. The evolution of the deformation substructure in a Ni–Co–Cr equiatomic solid solution alloy. Acta Mater. 132, 35–48 (2017).

Laplanche, G. et al. Reasons for the superior mechanical properties of medium-entropy crconi compared to high-entropy crmnfeconi. Acta Mater. 128, 292–303 (2017).

Li, Z., Pradeep, K. G., Deng, Y., Raabe, D. & Tasan, C. C. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength–ductility trade-off. Nature 534, 227–230 (2016).

Freitas, R. & Cao, Y. Machine-learning potentials for crystal defects. MRS Commun. 12, 510–520 (2022).

Pun, G. P. P., Yamakov, V., Hickman, J., Glaessgen, E. H. & Mishin, Y. Development of a general-purpose machine-learning interatomic potential for aluminum by the physically informed neural network method. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 113807 (2020).

Fujii, S. & Seko, A. Structure and lattice thermal conductivity of grain boundaries in silicon by using machine learning potential and molecular dynamics. Comput. Mater. Sci. 204, 111137 (2022).

Bartók, A. P., Kermode, J., Bernstein, N. & Csányi, G. Machine learning a general-purpose interatomic potential for silicon. Phys. Rev. X 8, 041048 (2018).

Goryaeva, A. M. et al. Efficient and transferable machine learning potentials for the simulation of crystal defects in bcc Fe and W. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 103803 (2021).

Saunders, N. & Miodownik, A. P. Calphad (Calculation of Phase Diagrams): a Comprehensive Guide (Elsevier, 1998).

Liu, Z.-K. First-principles calculations and Calphad modeling of thermodynamics. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 30, 517–534 (2009).

Walsh, F., Abu-Odeh, A. & Asta, M. Reconsidering short-range order in complex concentrated alloys. MRS Bull. 48, 753–761 (2023).

Nigam, J., Pozdnyakov, S. N., Huguenin-Dumittan, K. K. & Ceriotti, M. Completeness of atomic structure representations. APL Mach. Learn. 2, 016110 (2024).

Darby, J. P., Kermode, J. R. & Csányi, G. Compressing local atomic neighbourhood descriptors. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 166 (2022).

Willatt, M. J., Musil, F. & Ceriotti, M. Feature optimization for atomistic machine learning yields a data-driven construction of the periodic table of the elements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 29661–29668 (2018).

Lopanitsyna, N., Fraux, G., Springer, M. A., De, S. & Ceriotti, M. Modeling high-entropy transition metal alloys with alchemical compression. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 045802 (2023).

Qi, J., Ko, T. W., Wood, B. C., Pham, T. A. & Ong, S. P. Robust training of machine learning interatomic potentials with dimensionality reduction and stratified sampling. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 43 (2024).

Schwalbe-Koda, D., Tan, A. R. & Gómez-Bombarelli, R. Differentiable sampling of molecular geometries with uncertainty-based adversarial attacks. Nat. Commun. 12, 5104 (2021).

Deng, B. et al. Systematic softening in universal machine learning interatomic potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 1–9 (2025).

Walsh, F., Zhang, M., Ritchie, R. O., Minor, A. M. & Asta, M. Extra electron reflections in concentrated alloys do not necessitate short-range order. Nat. Mater. 22, 926–929 (2023).

Joress, H. et al. Why is EXAFS for complex concentrated alloys so hard? Challenges and opportunities for measuring ordering with x-ray absorption spectroscopy. Matter 6, 3673–3781 (2023).

Walsh, F., Zhang, M., Ritchie, R. O., Asta, M. & Minor, A. M. Multiple origins of extra electron diffractions in fcc metals. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn9673 (2024).

Baruffi, C., Ghazisaeidi, M., Rodney, D. & Curtin, W. Equilibrium versus non-equilibrium stacking fault widths in NiCoCr. Scr. Mater. 235, 115536 (2023).

Islam, M., Sheriff, K., Cao, Y. & Freitas, R. Nonequilibrium chemical short-range order in metallic alloys. arXiv:2409.15474 (2024).

Neumann, M. et al. Orb: a fast, scalable neural network potential. arXiv:2410.22570 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Mattersim: a deep learning atomistic model across elements, temperatures and pressures. arXiv:2405.04967 (2024).

Tang, H. et al. High accuracy neural network interatomic potential for niti shape memory alloy. Acta Mater. 238, 118217 (2022).

Thorn, A., Gochitashvili, D., Kharabadze, S. & Kolmogorov, A. N. Machine learning search for stable binary Sn alloys with Na, Ca, Cu, Pd, and Ag. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 22415–22436 (2023).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO—the open visualization tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2009).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python materials genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source Python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Jain, A. et al. Fireworks: a dynamic workflow system designed for high-throughput applications. Concurr. Comput.: Pract. Exp. 27, 5037–5059 (2015).

Fletcher, R. Practical Methods of Optimization (John Wiley & Sons, 2000).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Zunger, A., Wei, S.-H., Ferreira, L. G. & Bernard, J. E. Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 353–356 (1990).

Walle, A. V. D. et al. Efficient stochastic generation of special quasirandom structures. Calphad: Comput. Coupling Phase Diagr. Thermochem. 42, 13–18 (2013).

Chung, H. W., Freitas, R., Cheon, G. & Reed, E. J. Data-centric framework for crystal structure identification in atomistic simulations using machine learning. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 043801 (2022).

Metropolis, N., Rosenbluth, A. W., Rosenbluth, M. N., Teller, A. H. & Teller, E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 21, 1087–1092 (2004).

Morris, J. R., Wang, C., Ho, K. & Chan, C. T. Melting line of aluminum from simulations of coexisting phases. Phys. Rev. B 49, 3109 (1994).

Larsen, P. M., Schmidt, S. & Schiøtz, J. Robust structural identification via polyhedral template matching. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 24, 055007 (2016).

Cao, Y., Sheriff, K. & Freitas, R. MLP-cSRO v1.0.0. Github, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16740259 (2025).

Wu, Z., Bei, H., Pharr, G. M. & George, E. P. Temperature dependence of the mechanical properties of equiatomic solid solution alloys with face-centered cubic crystal structures. Acta Mater. 81, 428–441 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the MathWorks Ignition Fund, MathWorks Engineering Fellowship Fund, and the Portuguese Foundation for International Cooperation in Science, Technology and Higher Education in the MIT—Portugal Program. We were also supported by the Research Support Committee Funds from the School of Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This work used the Expanse supercomputer at the San Diego Supercomputer Center through allocation MAT210005 from the Advanced Cyber Infrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) program, which is supported by National Science Foundation grants #2138259, #2138286, #2138307, #2137603, and #2138296, and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which was supported by National Science Foundation grant number #1548562.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C., K.S., and R.F. conceived the project. Y.C. performed all simulations. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. Y.C. and R.F. prepared the manuscript, which was reviewed and edited by all authors. Project administration, supervision, and funding acquisition were performed by R.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Y., Sheriff, K. & Freitas, R. Capturing short-range order in high-entropy alloys with machine learning potentials. npj Comput Mater 11, 268 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01722-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01722-2

This article is cited by

-

Nonequilibrium chemical short-range order in metallic alloys

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Effect of Processing Conditions on Short-Range Order and Mechanical Properties of the NbMoTaW Multi-Principal Element Alloy

High Entropy Alloys & Materials (2025)