Abstract

The development of new materials exhibiting large anomalous Hall effect (AHE) is essential for realizing highly efficient spintronic devices. However, this development has been a time-consuming process due to the combinatorial explosion for multielement systems and limited experimental throughput. In this study, we identify new materials exhibiting large AHE in heavy-metal-substituted Fe-based alloys using a high-throughput materials exploration method that combines deposition of composition-spread films using combinatorial sputtering, photoresist-free facile multiple-device fabrication using laser patterning, simultaneous AHE measurement of multiple devices using a customized multichannel probe, and prediction of candidate materials using machine learning. Based on experimental AHE data on Fe-based binary system alloyed with various single heavy metals, we perform machine learning analysis to predict the Fe-based ternary system containing two heavy metals for larger AHE. We experimentally confirm larger AHE in the predicted Fe–Ir–Pt system. Using scaling analysis, we reveal that the enhancement of AHE originates from the extrinsic contribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The anomalous Hall effect (AHE)1, which generates voltage orthogonal to the applied electrical current and magnetization in magnetic thin films, underpins the development of various sensing devices such as magnetic sensors2,3,4, read-head sensors for hard-disk drives5, gas sensors6,7, and biosensors8. In order to realize these highly sensitive devices, the development of new materials exhibiting large AHE has always been essential. However, because of the infinite material combinations for multielement systems, referred to as combinatorial explosion, it remains challenging to identify new materials from huge material search spaces that have not yet been explored.

One of the simple methods to enhance AHE is the substitution of ferromagnetic materials with heavy metals that possess large spin–orbit coupling9,10,11,12,13,14 because the AHE is a transport phenomenon that is related to SOC1. The substitution of small amounts of a single heavy metal enhances the AHE14. For example, Ir substitution (12 at.%) of Fe3Co increased the anomalous Hall resistivity (\({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\)) by 9 times at room temperature14. However, the observed \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) value (2.91 µΩ cm) was below the one that would allow for practical use. It is expected that a multielement system containing multiple heavy metals would have the potential to further enhance the AHE15,16. However, due to the combinatorial explosion for multielement systems, systematic studies on the AHE enhanced by the substitution by various multiple heavy metals from 4d (i.e., Nb, Mo, Ru, Rh, Pd, and Ag) and 5d (i.e., Ta, W, Ir, Pt, and Au) elements have not been reported even for the basic room temperature ferromagnetic elements such as Fe, Co, and Ni. Thus, heavy-metal-substituted ferromagnetic alloy systems have remained an unexplored material search space.

Recently, high-throughput first-principles calculations and machine learning methods have been proposed for screening materials showing large AHE17,18,19,20,21,22. These computational methods have successfully proposed new candidates showing large intrinsic AHE from a large number of multielement systems in a short time. However, it is not always possible to experimentally realize the predicted materials even if they have thermodynamic stability (e.g., low formation energy and small hull distance) and phonon stability at 0 K within the calculation, because the actual synthesis is performed at finite temperatures23. In addition, it needs to be verified experimentally whether the predicted materials exhibit large AHE as calculated for the practical application. This motivates us to search for new materials for large AHE experimentally, combining experiments and machine learning techniques. To date, a combination of material synthesis and machine learning for automatic and autonomous determination of the next search parameters has been adapted for optimizing the fabrication conditions to obtain desired properties, which helps to reduce the number of experimental iterations24,25,26.

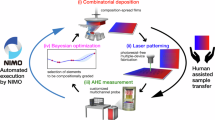

Regarding the experimental methods for the AHE (Fig. 1a), conventional methods have typically consisted of (i) individual deposition of a uniform thin film with a single composition, (ii) device fabrication using multi-step lithography processes with photoresists, (iii) AHE measurement with a wire-bonding process, and data analysis and determination of the next deposition condition by a human. In our experimental environment, each process takes (i) ≈1 h, (ii) ≈5.5 h, and (iii) ≈0.5 h; thus, the AHE experiment for only one composition takes ≈7 h in total. Such a conventional trial-and-error-type one-by-one manual approach with low experimental throughput would be inefficient to explore the vast unexplored material spaces and still time-consuming for high-throughput materials exploration, even when combined with machine learning. Therefore, it is inevitable to improve the throughput of the AHE experiments. In terms of the sample preparation, combinatorial deposition techniques are effective for high-throughput sample fabrication27,28,29,30. The combinatorial deposition can produce a continuous composition gradient on a single substrate with all possible compositional combinations in one experiment by co-deposition31,32,33,34 or multilayer deposition of wedged-shaped layers35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. Until now, an integration of combinatorial depositions and machine learning has been demonstrated for various types of materials46,47,48,49,50,51,52, but not for materials for the AHE.

a Conventional trial-and-error-type one-by-one manual approach consisting of (i) individual deposition of a uniform thin film with a single composition, (ii) device fabrication using multi-step lithography processes with photoresists, and (iii) AHE measurement using a wire-bonding method. b High-throughput materials exploration system consisting of (i’) deposition of composition-spread films using a combinatorial sputtering system, (ii’) photoresist-free facile multiple-device fabrication using a laser patterning system, and (iii’) simultaneous AHE measurement of multiple devices using a customized multichannel probe developed in this study.

Not only the deposition method but also high-throughput AHE measurements are required for efficient materials exploration for large AHE. The AHE in magnetic thin films is often measured using a physical property measurement system (PPMS; Quantum Design) as it requires a superconducting magnet to apply a strong perpendicular magnetic field over 2 T for saturating the magnetization to the film normal direction13,14,16,44. This method needs a wire-bonding process, which requires making wire connections between the devices and terminals of a sample puck either by a wire bonder or manual wiring for each measurement ((iii) in Fig. 1a). The number of devices that could be measured at one time is limited to a few due to the small number of terminals of the commercial sample puck for PPMS, which can be the significant instrumental bottleneck for high-throughput materials exploration. Therefore, a measurement system enabling simultaneous AHE measurement of many devices is needed. Previously, combinatorial measurements of transport properties such as the Hall effect and resistivity have been reported using pin probe arrays from other research groups53,54,55,56. A similar strategy using pin probe arrays can be applied for the simultaneous measurement of the AHE specialized for the PPMS system.

In this study, we demonstrate a high-throughput materials exploration system for large AHE that combines combinatorial deposition and measurement with machine learning. Using this system, we identify new materials exhibiting large AHE in heavy-metal-substituted Fe-based alloys. First, we collect a large number of experimental data on AHE in Fe-based binary system alloyed with various single heavy metals and study the composition dependence of AHE systematically. A machine learning model is then constructed based on the experimental data set of AHE in the Fe-based binary system to predict new materials that exhibit larger AHE in the Fe-based ternary system containing two heavy metals. Finally, based on the prediction, we fabricate an Fe–Ir–Pt ternary system and experimentally confirm the larger AHE compared to that observed in the binary system. We also reveal the origin of the enhancement of AHE in the Fe–Ir–Pt ternary system using a scaling law between longitudinal and anomalous Hall resistivities.

Results

High-throughput materials exploration system for the anomalous Hall effect (AHE)

The high-throughput materials exploration system for the AHE developed in this study (Fig. 1b) consists of (i’) deposition of composition-spread films using combinatorial sputtering, (ii’) photoresist-free facile multiple-device fabrication using laser patterning, and (iii’) simultaneous AHE measurement of multiple devices using a customized multichannel probe. The details of each experimental step are described in the Methods section. Briefly, composition-spread thin films, whose composition varies continuously in one direction within a single substrate, are deposited using a combinatorial sputtering system equipped with a linear moving mask and substrate rotation system ((i’) in Fig. 1b). Next, the composition-spread film is patterned into 13 Hall bar devices using a laser patterning system ((ii’) in Fig. 1b). The device pattern consists of 28 terminals including 13 pairs of terminals perpendicular to the composition gradient for the Hall voltage measurement that are connected with one pair of terminals for a common electrical current path along the composition gradient. The Hall bar devices are fabricated by drawing a single stroke of the outline of the device pattern with the laser. The film area drawn by the focused laser is removed by laser ablation, and the Hall bar devices are separated from the surrounding film area. This laser patterning process does not require any photoresists, which allows direct and facile multiple-device fabrication. Then, the AHE of the fabricated 13 devices is measured simultaneously using a customized multichannel probe that was developed in this study ((iii’) in Fig. 1b). The multichannel probe consists of a non-magnetic sample holder and a pin block with an array of 28 pogo-pins (spring-loaded pins) that are aligned in correspondence with the terminals of the devices. The sample is set in the sample holder, and the pin block is pressed onto the sample. The pin block and sample holder were fixed with screws so that the pogo-pins are in contact with the surface of the film. Thus, the time-consuming wire-bonding process is not necessary for this measurement system. The probe is subsequently installed in the PPMS, and the Hall voltages are measured using an external current source and a voltmeter while sweeping an external perpendicular magnetic field. The terminals for the 13 devices are connected to the voltmeter via a data acquisition system, which permits the interchange of the voltage pairs, enabling the measurement of the Hall voltages of the 13 devices sequentially while switching voltage measurement channels. Therefore, the AHE of all 13 devices can be measured simultaneously with only one round-trip of the magnetic-field sweep. Note that the AHE measurement using the customized multichannel probe was not adaptable at low temperatures due to the tolerance of the pogo-pins. The AHE experiment for 13 devices in one composition-spread film takes only ≈3 h, including ≈1.3 h for the deposition of composition-spread films, ≈1.5 h for the device fabrication by laser patterning, and ≈0.2 h for the simultaneous AHE measurement. Thus, using this high-throughput materials exploration system, the time required for the AHE experiment per one composition is equivalent to only ≈0.23 h, which is about 30 times higher throughput than the conventional method (≈7 h per one composition).

AHE in Fe–X binary system

To validate our high-throughput materials exploration system, we apply this system to identify new materials exhibiting large AHE in heavy-metal-substituted Fe-based alloys. We systematically investigate the effect of substitution by heavy metals on the AHE. First, we fabricated Fe-based binary system alloyed with various single heavy metals and measured the AHE to collect a large number of experimental data, which will be used for machine learning analysis described in the next section. Fe1–xXx composition-spread films (x ≤ 30%) were fabricated on MgO(100) substrates at room temperature by combinatorial sputtering deposition with X being various 4d and 5d heavy metals of 11 elements in total (Fig. 2a). The films were grown epitaxially on the MgO(100) substrates, confirmed by x-ray diffraction (XRD) (Fig. S1). Note that because the partial thicknesses in the one-unit layer are comparable to the lattice constants of Fe and the substituting heavy metals, the alloying of Fe and X element was achieved without heating process such as substrate heating during deposition and post-annealing, as evident by the observation of diffraction peaks from binary alloy phase in the XRD results (Fig. S1). The AHE of the films was measured using the multichannel probe after fabricating the devices by laser patterning. The total number of fabricated devices was 143 [= (13 devices for one film) × (11 substituting elements)]. The AHE experiment for one sample took ≈3 h. Thus, the AHE experiment for 11 films was completed in a total of only ≈33 h. The 135 devices out of 143 showed proper Hall signals, yielding a successful rate of device fabrication of 94.4% for this set of experiments. The failure of the remaining 8 devices to show proper signals would be due to the laser patterning process, such as electrical shunting by imperfect ablation.

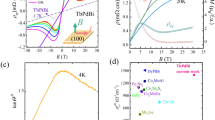

a Schematic illustration of Fe1–xXx composition-spread film (x ≤ 30 at.%) with various single heavy metals X. Composition dependence of anomalous Hall resistivity (\({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\)) for b X = Nb, Mo, Ru, Rh, Pd, and Ag (4 d heavy metals) and c X = Ta, W, Ir, Pt, and Au (5 d heavy metals) measured at 300 K.

The composition dependences of X on the AHE in Fe1–xXx composition-spread films for 4 d (Nb, Mo, Ru, Rh, Pd, and Ag) and 5 d (Ta, W, Ir, Pt, and Au) heavy metals measured at 300 K are shown in Fig. 2b, c, respectively. The \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) tended to increase after the substitution by heavy metals up to x ≈ 10% for all elements. The largest \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) of 5.25 µΩ cm was obtained for X = Ta for x = 12.6% (Fe87.4Ta12.6). For x ≥ ≈ 13%, a rapid decrease in \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) was observed for the alloying with Nb, Mo, Ru, Ta, W, and Ir, whereas the alloying with Rh, Pd, Ag, Pt, and Au did not show a large decrease or showed even an increase in \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) as further substituting. In other words, for x ≤ 30%, a rapid decrease in \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) tended to be observed for the alloying with VB (Nb and Ta) and VIB (Mo and W) elements, whereas the decrease tended not to be observed for the alloying with VIIIB (Rh, Pd, and Pt except for Ru and Ir; the same group as Fe) and IB (Ag and Au) elements in the periodic table. The rapid decrease in \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) would be attributed to loss of magnetization57 and/or change in the electronic structures through the phase transformation from ferromagnetic body-centered cubic (bcc) to non-magnetic face-centered cubic (fcc) at room temperature for the substituting elements such as Ir, and to amorphous phase for the substituting elements such as Ta (Fig. S1). As an overall tendency, alloying with 5d heavy metals (Ta, W, Ir, and Pt) tends to increase \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) than 4d elements.

Machine learning screening for Fe–Y–Z ternary system

In the Fe–X binary alloy system, several materials exhibiting large \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) have been discovered. This finding suggests that expanding the search space to a ternary alloy system (Fe–Y–Z, where Y and Z are heavy elements) may identify new materials with larger \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\). Now, assuming that Y and Z are selected from the 5 d heavy elements (Ta, W, Ir, Pt, and Au) that exhibited relatively large \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) as shown in Fig. 2b, c, with composition increments of 1 at.% and the Fe composition being 50 at.% or higher, this results in a search space containing 13,260 candidate materials. However, synthesizing and measuring all 13,260 patterns comprehensively would be extremely challenging.

Therefore, machine learning was employed to screen these ternary alloys. Here, a Gaussian process regression model was adopted. The training data consists of the experimental data of the AHE in Fe–X binary system as shown in Fig. 2b, c. The output is \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\), while the inputs (descriptors) are Magpie descriptors58. It is noted that the machine learning model in this study did not consider structural information. Details on the construction of the machine learning model are provided in the Methods section and the Supplementary Material. Figure 3 shows the accuracy of the Gaussian process regression model. The mean square error (MSE) was 0.0916926. Using this machine learning model to screen ternary alloys, \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) of the 13,260 candidate materials were predicted. As a result, Fe70Ir5Pt25 was expected as a material with the largest \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\). The other candidate materials below the second largest are listed in the Supplementary Material. However, since machine learning predictions are not always accurate, experimental validation is necessary.

AHE in Fe–Ir–Pt ternary system

To confirm whether the Fe–Ir–Pt ternary system predicted by the machine learning shows larger \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) experimentally, we fabricated FeyIrzPt1–y–z composition-spread films (Fig. 4a) and measured the AHE in the same manner as for the Fe–X binary system. Since machine learning models do not always predict the optimal composition with pinpoint accuracy, it is important to allow for flexibility and conduct experiments across a reasonably wide compositional range. The Fe composition (y) was fixed at a value between 50% and 90% in increments of 5% for each composition-spread film, and a composition gradient of Ir and Pt was formed in the remaining compositions from 50% to 10%, respectively. For this experiment, 8 films were fabricated in total, and 103 devices out of 104 showed proper Hall signals, yielding a successful rate of device fabrication of 99.0%.

a Schematic illustration of FeyIrzPt1–y–z composition-spread film. b Two-dimensional contour plot for \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) in FeyIrzPt1–y–z composition-spread films measured at 300 K. c Composition dependence of \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) in Fe80IrzPt20–z composition-spread film. The dotted horizontal line indicates the largest \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) value observed in the Fe–X binary system (5.25 µΩ cm for Fe87.4Ta12.6).

The two-dimensional contour plot for \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) in FeyIrzPt1–y–z composition-spread films measured at 300 K is shown in Fig. 4b. A larger \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) value than the maximum observed in the Fe–X binary system (5.25 µΩ cm) was successfully confirmed for some of the compositions. A maximum \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) value in the Fe–Ir–Pt ternary system was around 6.5 µΩ cm. Especially for y = 60% and 65%, it was clearly observed that the substitution of Fe–Pt alloys with a small amount of Ir (up to z ≈ 5% for these y values) tends to increase the \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\), exceeding the maximum value observed in the Fe–X binary system, which would agree with the machine analysis results.

For an easy view, the composition dependence of \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) in Fe80IrzPt20–z composition-spread film is shown in Fig. 4c. As increasing z, the \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) value first increased, showed larger values beyond 5.25 µΩ cm for z = 6.4%–16.9% exhibiting a maximum for z = 11.7%, and rapidly decreased after further Ir substitution. It is noted that a rapid decrease in \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) upon further Ir substitution was more visible for y = 50%–65% as shown in Fig. 4b. The rapid decrease in \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) would be attributed to the phase transformation of Fe–Ir–Pt ternary alloy from bcc to fcc by a large amount of Ir, as confirmed by XRD (Fig. S2), which could correspond to ferromagnetic and non-magnetic phases, respectively. Consequently, new materials exhibiting large AHE were successfully identified using the high-throughput system combining the combinatorial experiments and machine learning.

It is noted that the predicted \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) values for Fe80IrzPt20–z by machine learning were larger than the experimental values (see Fig. S3). However, the tendency of Ir composition dependence on \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) showing a maximum at around 10% was qualitatively consistent with the experimental results. Thus, because of the qualitative agreement, machine learning prediction can be used for materials exploration, as demonstrated in this study. The machine learning predictions are not always accurate, which underscores the importance of experimental validation.

Discussion

To understand the origin of the enhancement of AHE in Fe80IrzPt20–z, we employ a scaling analysis of the AHE results. By analyzing the temperature dependence of\(\,{\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) and longitudinal resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xx}}\)) using a scaling law, the mechanism behind the AHE can be separated out into extrinsic and intrinsic contributions quantitatively. We use a scaling equation called Tian-Ye-Jin (TYJ) scaling59; \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}=a{\rho }_{{xx}0}+b{\rho }_{{xx}}^{2}\), where \({\rho }_{{xx}0}\) is the residual resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xx}}\) at 10 K in this study), a corresponds to the extrinsic contribution by skew scattering, and b corresponds to the intrinsic contribution. It is noted that the TYJ scaling ignores the other contributions, such as phonon-induced skew scattering59. Because the TYJ scaling model was derived from the experimental data on Fe thin films59, it is reasonable to analyze our AHE results on Fe-based system alloyed with heavy metals in order to reveal the origin of AHE. The AHE and magnetoresistance (MR) for 6 devices in the Fe80IrzPt20–z composition-spread film were measured at 10–300 K. Here, we used PPMS with a conventional wire-bonding method to measure the temperature dependence of AHE because the AHE measurement using the customized multichannel probe was not adaptable at low temperatures due to the tolerance of the pogo-pins. The AHE curves and the obtained values for\(\,{\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}\) are shown in Fig. 5a–c, respectively. The temperature-dependent\(\,{\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\,\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}\) data in the \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) vs. \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{2}\) plots for each composition (Fig. 5d) were fitted using the TYJ scaling model. From Fig. 5e, the extrinsic parameter a increased as increasing the Ir composition, showing a maximum of 0.079 for z = 11.7%, and subsequently decreased. On the other hand, the intrinsic parameter b tended to decrease from 945 to 77 S/cm as the Ir increased. By using the obtained parameters, the \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) values were reproduced and decomposed into the extrinsic (\(a{\rho }_{{xx}0}\)) and intrinsic (\(b{\rho }_{{xx}}^{2}\)) terms. For example, the reproduced \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) value for z = 11.7% at 300 K was 6.53 µΩ cm, consisting of \(a{\rho }_{{xx}0}\) = 4.72 µΩ cm and \(b{\rho }_{{xx}}^{2}\) = 1.81 µΩ cm. Finally, the extrinsic contribution ratio, which is the ratio of \(a{\rho }_{{xx}0}\) to the reproduced total \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\), was calculated as \(a{\rho }_{{xx}0}/{\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\), as shown in Fig. 5f. If the ratio is larger than 50%, it means that the AHE is dominated by the extrinsic contribution. At 300 K, the extrinsic contribution ratio increased from 24% to 60% as increasing Ir from 1.1% to 6.4%, exhibiting a maximum of 72% for z = 11.7%, and decreased to 31% towards the highest z. From Fig. 5b, the largest \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) was observed for z = 11.7%, where the extrinsic contribution ratio showed a maximum. Therefore, based on the scaling analysis, the enhancement of \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) in the Fe80IrzPt20–z composition-spread film can be attributed to the strong extrinsic contribution.

a Magnetic-field-dependent Hall resistivity (\({\rho }_{{yx}}\)) curves at 300 K. Composition dependence of b \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) and c longitudinal resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xx}}\)) from 10 to 300 K. d \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) vs. \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{2}\) plots. The data were analyzed using the scaling relation \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}=a{\rho }_{{xx}0}+b{\rho }_{{xx}}^{2}\), where \({\rho }_{{xx}0}\) is the residual resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xx}}\) at 10 K in this study), a corresponds to the extrinsic contribution by skew scattering, and b corresponds to the intrinsic contribution, which is indicated by black solid lines. e Fitting parameters a and b obtained from the fitting analysis. f Extrinsic contribution ratio calculated as \(a{\rho }_{{xx}0}/{\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\).

The AHE may be further enhanced by tailoring the extrinsic contribution by the use of more than two substituting heavy metals and/or more than one ferromagnetic base element in an expanded material search space. It should be noted that the concentration of substituting heavy metals should not be so high that the material loses its ferromagnetism. It would also be important to understand the microscopic mechanism of the enhancement of AHE in the heavy-metal-substituted ferromagnetic systems using rigorous physical models such as phase shift model60, which may provide insight into obtaining larger AHE in the future.

The demonstration of our high-throughput materials exploration system for the AHE that combines the combinatorial deposition and measurement with machine learning and the experimental realization of new materials exhibiting large AHE are strongly expected to contribute to data-driven materials search in the future. This system also has the potential to be more efficient by introducing robotics into the experimental loop, eliminating manual operations such as sample transfer between equipment, or introducing automatic determination of next conditions, which will lead to a fully automatic and autonomous materials search system61,62,63.

Methods

Combinatorial deposition

Composition-spread thin films were fabricated using a combinatorial magnetron sputtering system (CMS-A6250X2, Comet Inc.) ((i’) in Fig. 1b). Single-crystal MgO(100) substrates with a size of 10 × 10 mm2 (Furuuchi Chemical Corp.) were cleaned by acetone, ethanol, and deionized water with ultrasonication. The substrates were installed in the chamber and further cleaned by in situ Ar-ion milling. For Fe1–xXx binary system with x ≤ 30% (Fig. 2a), a uniform layer of Fe was first deposited on the substrates. Then, a wedge-shaped Fe layer was deposited on the uniform Fe layer with a composition gradient width of 6 mm using a linear moving mask. Subsequently, the substrates were rotated by 180°, and a wedge-shaped layer of single heavy metals (X = Nb, Mo, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ag, Ta, W, Ir, Pt, and Au) was deposited on the wedge-shaped Fe layer with the same thickness and composition gradient width. The partial thickness of the uniform Fe layer and the wedge-shaped Fe and X layers was designed so that the maximum substituting concentration of X element (x) can be 30 at.% at the X-richest region. For FeyIrzPt1–y–z ternary system (Fig. 3a), a uniform layer of Fe was first deposited on the substrates. A wedge-shaped layer of Ir was deposited on the uniform Fe layer with a composition gradient width of 6 mm using the linear moving mask. After the substrate rotation by 180°, a wedge-shaped Pt layer was deposited on the wedge-shaped Ir layer with the same thickness and composition gradient width. The partial thickness of the uniform Fe layer and the wedge-shaped Ir and Pt layers was designed so that the Fe composition (y) varied from 50% to 90% in increments of 5%, corresponding to a composition gradient of Ir and Pt in the remaining compositions from 50% to 10%, respectively. The total thickness for the one-unit layer was fixed to 0.5 nm. The deposition process was repeated 60 times to obtain 30-nm-thick films. The deposition was performed with a substrate temperature of room temperature and Ar process gas pressure of 0.6 Pa. After the deposition, the films were capped with Al or Ta (2 nm) to prevent oxidation.

Device fabrication

The composition-spread film was patterned into 13 Hall bar devices using a laser patterning system (VL-C30-RGBV, Sigmakoki Co., Ltd.) ((ii’) in Fig. 1b). This laser patterning does not require any photoresists that are commonly used in almost all other lithographic processes. The film was placed on an XYZθ-stage. The Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet (YAG) laser with a wavelength of 532 nm was focused on the films with a spot size of 10 × 10 µm2 using an objective lens with ×20 magnification. The device pattern, as shown in (ii’) in Fig. 1b, was prepared by computer-aided design. The device pattern consists of 28 terminals including 13 pairs of terminals perpendicular to the composition gradient for the Hall voltage measurement, that are connected with one pair of terminals for a common electrical current path along the composition gradient. The Hall bar devices were fabricated by drawing a single stroke of the outline of the device pattern with the laser while moving the stage. The film area drawn by the focused laser was removed by laser ablation, and the Hall bar devices were separated from the surrounding film area. The size of the electrical contact pads was designed to be 0.9 mm × 1 mm. The Hall bar width after the laser patterning was approximately 10 µm for the voltage detection, where the compositional variation within one bar was estimated to be less than ≈ +/–0.04%.

Simultaneous AHE measurement

A customized multichannel probe was developed for the simultaneous AHE measurement ((iii’) in Fig. 1b). The customized multichannel probe consists of a non-magnetic sample holder made of aluminum and a pin block made of polyether ether ketone (PEEK) with a pogo-pin array. These are attached to the end of a rod of a multi-functional probe that is suitable for measurements in the PPMS chamber. The sample holder has a drop carved with a size of 10.2 mm (horizontal) × 10.2 mm (vertical) × 2.3 mm (depth) in order to accommodate a 10 mm (horizontal) × 10 mm (vertical) × 0.5 mm (thickness) substrate. The pin block contains 28 non-magnetic pogo-pins (spring-loaded pins) with a round tip of φ = 0.21 mm (NMPH-0.30, TESPRO Co., Ltd.) at a pitch of approximately 1 mm to match the locations of the 28 electrical contact pads of the laser-patterned devices. First, a laser-patterned sample was set in the carved drop of the sample holder. For the 10 mm × 10 mm square sample, the carved drop has a 0.2 mm allowance per side. Even if the sample was placed off-center within the carved drop, because the size of the laser-patterned electrical contact pad is 0.9 × 1 mm, each pogo-pin can always contact the inside of each electrical contact pad. The pin block was then pressed onto the sample, and the pin block and sample holder were fixed with four screws so that the pogo-pins are in contact with the surface of the film. Force is applied to the tip of the pogo-pin (plunger) by contacting the surface of a 0.5-mm-thick substrate placed in a 2.3-mm-deep carved drop, compressing the spring inside the pogo-pin by approximately 1.8 mm, thereby achieving a good contact between the surface of the electrical contact pad and the tip of the pogo-pin by an optimal load. After that, the multi-functional probe was inserted into the PPMS chamber (PPMS Versalab, Quantum Design). An electrical conductor came out of each pogo-pin on the opposite side of the pin block from the one in contact with the electrical contact pad, and was routed through the inside of the rod of the multi-functional probe and came out of the PPMS chamber. The AHE was measured using an external current source and voltmeter. The 2 wires corresponding to a pair of a common current channel were connected to a current source (Keithley 2401). The 26 wires corresponding to 13 pairs of a voltage channel were connected to a voltmeter (Keithley 7701) via a DAQ system (Keithley DAQ6510). The Hall voltage was measured with a constant electrical current of 0.2 mA while the perpendicular magnetic field was swept using the PPMS. By interchanging the voltage pairs using the DAQ system, the Hall voltages of the 13 devices can be measured sequentially. Thus, with only one round-trip magnetic-field sweep, the AHE of all 13 devices can be measured simultaneously. The AHE measurement results were visualized using a LabVIEW program in real time. The AHE measurement using the customized multichannel probe was not adaptable at low temperatures due to the tolerance of the pogo-pins. The \({\rho }_{{yx}}\) was obtained using \({\rho }_{{yx}}={R}_{{yx}}\cdot t\), where \({R}_{{yx}}\) is the Hall resistance and t is the film thickness (30 nm in this study). The anomalous term of the Hall resistivity (\({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\)) was obtained using \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}=\left({\rho }_{{yx}}^{+}-{\rho }_{{yx}}^{-}\right)/2\), where \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{+\left(-\right)}\) is the value obtained by extrapolating the data of the H-dependent \({\rho }_{{yx}}\) curves in the saturation region from positive (negative) to zero field. The comparison between the AHE curves obtained using our customized multichannel probe and the conventional wire-bonding method is shown in Fig. S4. The AHE curves obtained using our customized multichannel probe exactly matched the curves obtained using the conventional wire-bonding method. This clearly shows that our developed measurement method is accurate and reliable. It is also noted that comparing the \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\) values at 300 K obtained using the wire-bonding method in Fig. 5b with the ones obtained using the multichannel probe in Fig. 4c, the values were the same between the corresponding compositions. This also clearly confirms that the AHE can be evaluated properly using our customized multichannel probe developed in this study.

Machine learning

Gaussian process regression was performed using gausspr function from the kernelab package in R software. The output (objective variable) is \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\), while the input (explanatory variables) are Magpie descriptors. The radial basis kernel function (rbfdot) was used as the kernel function (kernel). The hyperparameter (sigma) was determined heuristically (sigest) to 0.00064556 with the kpar parameter set to automatic. The initial noise variance (var) and tolerance of the termination criterion (tol) were set to 0.001. As a result, the mean square error (MSE) was 0.0916926. More details are shown in the Supplemental Material.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The crystal structures of the composition-spread films were characterized using XRD (SmartLab, Rigaku) with a Cu-Kα radiation. The X-ray was collimated using a 0.5 mm incident slit. The irradiation position of X-ray was varied using an XY-stage. A flat imaging plate was used to collect two-dimensional (2D) XRD images. The one-dimensional (1D) XRD patterns were obtained from the 2D XRD images using an instrument software (SmartLab Studio II, 2DP; Rigaku).

Temperature-dependent AHE measurement

The temperature dependence of AHE from 10 to 300 K was evaluated using the Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS DynaCool; Quantum Design). Here, we used PPMS with a conventional wire-bonding method to measure the temperature dependence of AHE because the AHE measurement using the customized multichannel probe was not adaptable at low temperatures due to the tolerance of the pogo-pins. The Hall voltage was measured by sweeping an external perpendicular magnetic field (H) up to 3 T with a constant current of 100 µA. The \({\rho }_{{yx}}\) was obtained using \({\rho }_{{yx}}={R}_{{yx}}\cdot t\), where \({R}_{{yx}}\) is the Hall resistance and t is the film thickness (30 nm in this study). The anomalous term of the Hall resistivity (\({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}\)) was obtained using \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{A}=\left({\rho }_{{yx}}^{+}-{\rho }_{{yx}}^{-}\right)/2\), where \({\rho }_{{yx}}^{+\left(-\right)}\) is the value obtained by extrapolating the data of the H-dependent \({\rho }_{{yx}}\) curves in the saturation region from positive (negative) to zero field. To evaluate the longitudinal resistivity at the saturated magnetization state (\({\rho }_{{xx}}\)), the magnetoresistance (MR) was also measured from 10 to 300 K by sweeping H up to 3 T with a constant current of 100 µA. The \({\rho }_{{xx}}\) was obtained using \({\rho }_{{xx}}=\left({\rho }_{{xx}}^{+}+{\rho }_{{xx}}^{-}\right)/2\), where \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{+\left(-\right)}\) is the value obtained by extrapolating the data of the H-dependent \({\rho }_{{xx}}\) curves in the saturation magnetization state from positive (negative) to zero field.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes used to generate the data of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Nagaosa, N., Sinova, J., Onoda, S., MacDonald, A. H. & Ong, N. P. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1539–1592 (2010).

Peng, W. L., Zhang, J. Y., Luo, L. S., Feng, G. N. & Yu, G. H. The ultrasensitive anomalous Hall effect induced by interfacial oxygen atoms redistribution. J. Appl. Phys. 125, 093906 (2019).

Wang, K., Zhang, Y. & Xiao, G. Anomalous Hall sensors with high sensitivity and stability based on interlayer exchange-coupled magnetic thin films. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 064009 (2020).

Shiogai, J., Fujiwara, K., Nojima, T. & Tsukazaki, A. Three-dimensional sensing of the magnetic-field vector by a compact planar-type Hall device. Commun. Mater. 2, 102 (2021).

Nakatani, T. et al. Perspective on nanoscale magnetic sensors using giant anomalous Hall effect in topological magnetic materials for read head application in magnetic recording. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 070501 (2024).

Gerber, A., Kopnov, G. & Karpovski, M. Hall effect spintronics for gas detection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 143505 (2017).

Liang, J. Y. et al. Realization of an H2/CO dual-gas sensor using CoPd magnetic structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 182401 (2018).

Ramesh, A. K., Chou, Y. T., Lu, M. T., Singh, P. & Tseng, Y. C. Biological sensing using anomalous Hall effect devices. Nanotechnology 33, 335502 (2022).

Dorleijn, J. W. F. & Miedema, A. R. On the sign of the anomalous Hall effect in ferromagnetic alloys. Phys. Lett. 55A, 118 (1975).

Seemann, K. M. et al. Spin-orbit strength driven crossover between intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms of the anomalous Hall effect in the epitaxial L10-ordered ferromagnets FePd and FePt. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 076402 (2010).

Zhu, J. P., Ma, L., Zhou, S. M., Miao, J. & Jiang, Y. Tb doping induced enhancement of anomalous Hall effect in NiFe films. Chin. Phys. B 24, 017101 (2015).

Fujiwara, K., Satake, Y., Shiogai, J. & Tsukazaki, A. Doping-induced enhancement of anomalous Hall coefficient in Fe-Sn nanocrystalline films for highly sensitive Hall sensors. APL Mater. 7, 111103 (2019).

Jamaluddin, S., Roy, R., Das, A., Kanungo, S. & Nayak, A. K. Extrinsic to intrinsic mechanism crossover of anomalous Hall effect in the Ir-doped MnPtSn Heusler system. Phys. Rev. B 106, 184424 (2022).

Toyama, R., Zhou, W. & Sakuraba, Y. Extrinsic contribution to the anomalous Hall effect and Nernst effect in Fe3Co single-crystal thin films by Ir doping. Phys. Rev. B 109, 054415 (2024).

He, P. et al. Chemical composition tuning of the anomalous Hall effect in isoelectronic L10FePd1–xPtx alloy films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 066402 (2012).

Ma, L. et al. Anomalous Hall effect in magnetic disordered alloys: effects of spin orbital coupling. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 243912 (2013).

Samathrakis, I., Long, T., Zhang, Z., Singh, H. K. & Zhang, H. Enhanced anomalous Nernst effects in ferromagnetic materials driven by Weyl nodes. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 55, 074003 (2022).

Ji, Y., Zhang, W., Zhang, H. & Zhang, W. Spin Hall conductivity and anomalous Hall conductivity in full Heusler compounds. New J. Phys. 24, 053027 (2022).

Železný, J., Yahagi, Y., Ollivella, C. G., Zhang, Y. & Sun, Y. High-throughput study of the anomalous Hall effect. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 151 (2023).

Tanzim, M. F. et al. Giant anomalous Hall and Nernst conductivities in magnetic all-d metal Heusler alloys. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214967 (2023).

Xing, G., Masuda, K., Tadano, T. & Miura, Y. Chemical-substitution-driven giant anomalous Hall and Nernst effects in magnetic cubic Heusler compounds. Acta Mater. 270, 119856 (2024).

Nguyen, Q. A. T., Ho, T. H., Kim, S. G., Kumar, A. & Bui, V. Q. Orbital-engineered anomalous Hall conductivity in stable full Heusler compounds: a pathway to optimized spintronics. J. Mater. Chem. C 12, 15082–15091 (2024).

Sanvito, S. et al. Accelerated discovery of new magnets in the Heusler alloy family. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602241 (2017).

Wakabayashi, Y. K. et al. Machine-learning-assisted thin-film growth: Bayesian optimization in molecular beam epitaxy of SrRuO3 thin films. APL Mater. 7, 101114 (2019).

Ohkubo, I. et al. Realization of closed-loop optimization of epitaxial titanium nitride thin-film growth via machine learning. Mater. Today Phys. 16, 100296 (2021).

Lambard, G., Sasaki, T. T., Sodeyama, K., Ohkubo, T. & Hono, K. Optimization of direct extrusion process for Nd-Fe-B magnets using active learning assisted by machine learning and Bayesian optimization. Scr. Mater. 209, 114341 (2022).

Koinuma, H. & Takeuchi, I. Combinatorial solid-state chemistry of inorganic materials. Nat. Mater. 3, 429 (2004).

Zhao, J. C. Combinatorial approaches as effective tools in the study of phase diagrams and composition–structure–property relationships. Prog. Mater. Sci. 51, 557–631 (2006).

Green, M. L., Takeuchi, I. & Hattrick-Simpers, J. R. Applications of high throughput (combinatorial) methodologies to electronic, magnetic, optical, and energy-related materials. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 231101 (2013).

Li, Z., Ludwig, A., Savan, A., Springer, H. & Raabe, D. Combinatorial metallurgical synthesis and processing of high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. 33, 3156–3169 (2018).

Chevrier, V. & Dahn, J. R. Production and visualization of quaternary combinatorial thin films. Meas. Sci. Technol. 17, 1399–1404 (2006).

Uchida, K. I. et al. Combinatorial investigation of spin-orbit materials using spin Peltier effect. Sci. Rep. 8, 16067 (2018).

Hong, Y. et al. A high throughput study of both compositionally graded and homogeneous Fe–Pt thin films. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 18, 1245–1255 (2022).

Padhy, S. P. et al. Rapid multi-property assessment of compositionally modulated Fe-Co-Ni thin film material libraries. Results Mater. 14, 100283 (2022).

Chang, H., Takeuchi, I. & Xiang, X. A low-loss composition region identified from a thin-film composition spread of (Ba1–x–ySrxCay)TiO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 1165–1167 (1999).

Tsui, F. & Ryan, P. A. Combinatorial molecular beam epitaxy synthesis and characterization of magnetic alloys. Appl. Surf. Sci. 189, 333–338 (2002).

Ludwig, A., Zarnetta, R., Hamann, S., Savan, A. & Thienhaus, S. Development of multifunctional thin films using high-throughput experimentation methods. Int. J. Mater. Res. 99, 1144 (2008).

He, L., Collins, B. A., Tsui, F. & Chu, Y. S. Epitaxial growth of CoxMnySiz (111) thin films in the compositional range around the Heusler alloy Co2MnSi. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 29, 03C124 (2011).

Masuda, H. et al. Large spin-Hall effect in non-equilibrium binary copper alloys beyond the solubility limit. Commun. Mater. 1, 75 (2020).

Modak, R. et al. Combinatorial tuning of electronic structure and thermoelectric properties in Co2MnAl1–xSix Weyl semimetals. APL Mater. 9, 031105 (2021).

Modak, R. et al. Sm-Co-based amorphous alloy films for zero-field operation of transverse thermoelectric generation. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 23, 767–782 (2022).

Toyama, R. et al. Origin of negative anisotropic magnetoresistance effect in Fe0.75Co0.25 single-crystal thin films upon Ir addition. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 084401 (2023).

Toyama, R. et al. Combinatorial optimization for high spin polarization in Heusler alloy composition-spread thin films by anisotropic magnetoresistance effect. APL Mater. 11, 101127 (2023).

Toyama, R. et al. Large anomalous Nernst conductivity of L10-ordered CoPt in CoPt composition-spread thin films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 57, 405001 (2024).

Barwal, V. et al. Large magnetoresistance and high spin-transfer torque efficiency of Co2MnxFe1-xGe (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) Heusler alloy thin films obtained by high-throughput compositional optimization using combinatorially sputtered composition-gradient film. APL Mater. 12, 111114 (2024).

Ren, F. et al. Accelerated discovery of metallic glasses through iteration of machine learning and high-throughput experiments. Sci. Adv. 4, eaaq1566 (2018).

Iwasaki, Y. et al. Machine-learning guided discovery of a new thermoelectric material. Sci. Rep. 9, 2751 (2019).

Ludwig, A. Discovery of new materials using combinatorial synthesis and high-throughput characterization of thin-film materials libraries combined with computational methods. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 70 (2019).

Iwasaki, Y. et al. Identification of advanced spin-driven thermoelectric materials via interpretable machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 103 (2019).

Matsubara, M., Suzumura, A., Ohba, N. & Asahi, R. Identifying superionic conductors by materials informatics and high-throughput synthesis. Commun. Mater. 1, 5 (2020).

Iwasaki, Y., Sawada, R., Saitoh, E. & Ishida, M. Machine learning autonomous identification of magnetic alloys beyond the Slater-Pauling limit. Commun. Mater. 2, 31 (2021).

Fébba, D. M. et al. Autonomous sputter synthesis of thin film nitrides with composition controlled by Bayesian optimization of optical plasma emission. APL Mater. 11, 071119 (2023).

Minami, H. et al. Rapid synthesis and characterization of (Ca1-xBax)3Co4O9 thin films using combinatorial methods. Appl. Surf. Sci. 197–198, 442–447 (2002).

Hewitt, K. C., Casey, P. A., Sanderson, R. J., White, M. A. & Sun, R. High-throughput resistivity apparatus for thin-film combinatorial libraries. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76, 093906 (2005).

Clayhold, J. A. et al. Combinatorial measurements of Hall effect and resistivity in oxide films. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79, 033908 (2008).

Jin, K. et al. Combinatorial search of superconductivity in Fe-B composition spreads. APL Mater. 1, 042101 (2013).

Zeng, C. et al. Linear magnetization dependence of the intrinsic anomalous Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 037204 (2006).

Ward, L., Agrawal, A., Choudhary, A. & Wolverton, C. A general-purpose machine learning framework for predicting properties of inorganic materials. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 16028 (2016).

Tian, Y., Ye, L. & Jin, X. Proper scaling of the anomalous Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 087206 (2009).

Johansson, A. et al. Validity of the relativistic phase shift model for the extrinsic spin Hall effect in dilute metal alloys. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26, 274207 (2014).

Burger, B. et al. A mobile robotic chemist. Nature 583, 237–241 (2020).

Shimizu, R., Kobayashi, S., Watanabe, Y., Ando, Y. & Hitosugi, T. Autonomous materials synthesis by machine learning and robotics. APL Mater. 8, 111110 (2020).

Macleod, B. P. et al. Self-driving laboratory for accelerated discovery of thin-film materials. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz8867 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank T. Hiroto from NIMS for the technical support with the XRD measurement. The authors thank M. K. Manikketh from NIMS for his help with making the contour plot. This work was supported by JST CREST (Grant No. JPMJCR21O1), JST ERATO “Magnetic Thermal Management Materials Project” (Grant No. JPMJER2201), MEXT Program: Data Creation and Utilization-Type Material Research and Development Project (Digital Transformation Initiative Center for Magnetic Materials; Grant No. JPMXP1122715503), and JSPS KAKENHI Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (Grant Nos. JP21H01608 and JP24K00932).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.T., Y.I., and Y.S. conceived the original idea and designed the experiment. R.T. carried out the experiment and analysis. Y.I. performed the machine learning analysis. R.T., P.D.K., H.S., T.N., and Y.S. developed the customized multichannel probe and measurement system for the AHE. R.T. wrote the original manuscript with the input from Y.I. All the authors discussed the results, commented on the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Toyama, R., Iwasaki, Y., Kulkarni, P.D. et al. High-throughput materials exploration system for the anomalous Hall effect using combinatorial experiments and machine learning. npj Comput Mater 11, 269 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01757-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01757-5

This article is cited by

-

Modelling and estimation of chemical reaction yields from high-throughput experiments

Communications Chemistry (2026)

-

Autonomous closed-loop exploration of composition-spread films for the anomalous Hall effect

npj Computational Materials (2025)