Abstract

Second-principles method is an efficient way to build atomistic models and is widely used to simulate various properties of perovskite ferroelectric materials. However, the state-of-the-art approach to constructing training set for second-principles model still highly relies on researcher’s experience and a universal approach remains elusive. In this work, we combine machine learning and second principles method to achieve automatic generation of second-principles model. The original training set is derived from phonons and is then updated based on the uncertainties predicted by machine learning with data generated via molecular dynamics simulations. This approach allows us to obtain a machine learning assisted second-principles model for BaTiO3, which has a much-improved accuracy compared to the model in our previous work [Physical Review B, 108 134117 (2023)]. Furthermore, we investigate thermal transport properties of BaTiO3 with the new second-principles model, and find a weak wave-like contribution to the thermal conductivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ferroelectrics are a class of materials characterized by their temperature-dependent spontaneous polarization that can be reversed by external electric field. These materials have been widely studied ever since it was found in 1920s and has been used as non-volatile memory devices, sensors, actuators, solid refrigeration and so on1,2,3,4,5,6. Since spontaneous polarization only emerge when the temperature is below Curie temperature, the properties of ferroelectric materials are sensitive to temperature, which brings great challenge to theoretical studies. Although first principles calculations based on density functional theory7 can be used to investigate temperature effect in ferroelectric materials via ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD)8, the expensive computational cost limits the simulation to hundreds of atoms and prevents the study of ferroelectric materials at larger time and length scale. Meanwhile, the empirical force fields-based simulations are efficient but usually have low accuracy, making them inadequate for situations that require precise predictions of material properties. To balancing the high computational cost of first-principles calculation and low precision of empirical force fields, several first-principles based multiscale simulation approaches have been proposed, such as first-principles based phase field simulation9, effective Hamiltonian method10,11, bond valence model parameterized with DFT12, machine learning force fields (MLFF)13,14 and second-principles method15. Among them, second-principles method has been regarded as a successful model and has been built for NdNiO216, BaTiO3 (BTO)17, CaTiO318, PbTiO3, SrTiO319, PbTiO3/SrTiO3 superlattice20,21, and PbZrO318. These models have subsequently been used to study phase transition, negative capacitance, polar skyrmions, and energy storge.

The second-principles method was first proposed by J. Íñiguez et. al in 201315, which describes potential energy by a Taylor polynomial expansion with respect to the reference structure. All the energy terms are written in the form of polynomials, and the homogenous strain and displacements of atoms are treated as degree of freedom. The parameters for harmonic terms are directly calculated at first-principles level, which means that all the harmonic interactions are exact. For the parameters of anharmonic terms, the second principles method uses a training set calculated from first principles to fit those parameters. The quality of training set dictates the upper limits of model and how to build a ‘good enough’ training set is an essential task. Up to date, building the training set for second-principles model still requires elaborate design and highly relay on researcher’s experience, which limit the broader application of the second-principles method. Therefore, it is highly demanded to explore a reliable, automatic, and efficient strategy for the training set construction to facilitate the development of second-principles models.

With the rapid development in artificial intelligence, machine learning has gradually become a powerful technique in the field of multiscale simulation. One of the most successful multiscale simulation approaches is the MLFF. Since the advent of BPNN in 200714, numerous MLFF have been proposed, such as DeepMD22, SchNet23, DTNN24, GAP25, NNP26, MTP27 and so on. The machine learning model needs to be trained on a dataset, and is similar to second principles method to some extent. Due to the powerful fitting capabilities, machine learning models can precisely reproduce potential energy surface. In addition, recent developments in MLFF demonstrates the efficiency and reliability of on-the-fly active learning methods for training the forces fields28,29,30,31,32,33, and the training procedure can be carried out automatic. Numerous ‘on the fly’ techniques have been integrated with machine learning potentials, leading to a series of achievements. For instance, DPGEN proposed by Zhang et al. can automatically generate uniformly accurate atomic models automatically, while minimizing human effort34. Vandermause et al. introduced an adaptive Bayesian inference method for automating the training of MLFF, and implemented it in the software FLARE32. Yu et al. updated their training set for NEP based on principal component analysis on MD results35. However, the computational inefficiency and growing demand for larger-scale simulations still leave room for atomistic models. In this context, combining machine learning with atomistic models have recently attracted considerable attention. In particular, efforts have been made to integrate the on-the-fly machine learning method with the effective Hamiltonian approach33,36,37, providing a universal and automatic scheme for constructing effective Hamiltonian models. Given this success and the advantage of second-principles method over the effective Hamiltonian in incorporating the full atomistic degrees of freedom38, integrating the on-the-fly machine learning into the second-principles also appears to be a very promising avenue for further exploration.

Therefore, in this work, we developed a machine learning based automatic process for building second-principles model, and demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach in the prototypical ferroelectric perovskite BaTiO3. In this approach, Bayesian inference was introduced into iteratively update and refine the training set, leading to continuous improvement of the model. Compared to the original second-principles model, the final model achieves significantly higher accuracy and reproduces phonon dispersion that aligns much more closely with first-principles calculations. The thermal transport properties of BaTiO3 were also investigated using the improved second-principles model.

Results

Machine-learning assisted second-principles model

This work applied the on-the-fly machine learning scheme to BaTiO3. We started from the training set proposed in our previous work in ref. 17, and rebuilt a second principles model with 96 anharmonic energy terms. In the subsequent sections, we will refer to this model as Model_0. The total energies of the training set from DFT calculations and second principles model are shown in the insert of Fig. 1a. Next, we performed a 1000 steps MD simulation on 2 × 2 × 2 supercell starting from rhombohedral, orthorhombic and tetragonal phases at 15 K. The Bayesian error of these structures is given in Fig. 1a. The error of rhombohedral phase is larger than that of orthorhombic and tetragonal phases indicates that our original model behaves worse at energy area far from reference structure than that close to reference structure. This result is obvious, as can be seen in Fig. 2 of ref. 17, the original model has significant inaccuracies in predicting the R3m phase. All the structures corresponding to the local maximum error are selected and calculated with DFT before adding to the training set. After two iterations, we obtained Model One and Model Two. Figures 1b and S1 presents the Bayesian errors of these two models starting from rhombohedral, orthorhombic, and tetragonal phase, respectively. The maximum Bayesian errors quickly reduce from 0.285 to 0.02 demonstrating the high efficiency of this method. These results indicate that Model Two is accurate enough to predict properties of BaTiO3 under 15 K. However, after employing higher temperatures during MD simulations, the Bayesian errors exhibited a significant increase. The Bayesian error of Model Two under different temperature is shown in Fig. 1c, the maximum of Bayesian error increases with temperature. Thus, Model Two is unreliable at higher temperature, and it’s necessary to update temperature during our on-the-fly machine learning scheme. Thus, we raise the temperature during MD simulations, and expand training set based on Bayesian error. The maximum Bayesian error resulting from model iterations is illustrated in Fig. 1d. The maximum Bayesian error for all the temperatures can rapidly decrease to less than 0.1, and demonstrate the efficiency of this method. The maximum Bayesian error at the end of on-the-fly machine learning procedure is 0.019, and we totally run 36,000 MD steps. The size of training set is expanded from 741 to 2085. Comparing to the MLFF which typically require thousands of structures for training set32,39,40, this on-the-fly machine learning assisted second-principles model can significantly reduce computational cost. The energies predicted with our model before and after on-the-fly machine learning procedure are shown in Fig. 2a. Comparing to the model reported in ref. 17, our new model considered many structures with higher energies in the training set. Furthermore, we compared stress components predicted with our model and DFT calculations, as shown in Fig. 2b–d. All the points in Fig. 2 are close to the straight-line x = y indicating that the accuracy of our model is excellent.

a Bayesian error obtained during MD simulations starting from rhombohedral, orthorhombic and tetragonal phase at 15 K. The insert is the energy comparison between DFT and second-principles model at the beginning of our machine learning scheme. b Bayesian error obtained from MD simulations starting from rhombohedral phase. c Bayesian error of Model Two under different temperature. d The maximum Bayesian error resulting from model iterations.

Structural and vibrational properties

The calculated ground states properties from DFT and our model together with their comparison to experiment are summarized in Table 1. The energy of reference structure (cubic phase) is selected to be zero. The structure and spontaneous polarization from our model agree well with DFT calculations and experiment data measured at 15 K41. Next, we investigated all the metastable phases captured by DFT calculations. All these metastable phases corresponding to the local minimum of potential energy surface and can be used to validate the accuracy of our model. As shown in Fig. 3a, the local minimum energies from our model are almost the same as DFT calculations. Furthermore, we compared these energies with our previous model. The energies differences between DFT and second-principles models of all metastable phases are listed in Table 2. Comparing to the previous model, the differences are reduced to values ranging from 40 to 2.9% across distinct phases, which indicates that our new model has great improvements in predicting all the metastable phases. The lattice distortions obtained from DFT calculations and our model are given in Fig. 3b. The consistency between DFT calculations and our model indicates that our model accurately reproduces the same structures as those derived from DFT calculations.

Our model is then used to calculate the interatomic force constants (IFCs) and dynamical matrices according to the finite displacement method. The phonon dispersion of the rhombohedral phase based on original model is given in Fig. 4a. Although the original model is consistent well with DFT at low frequency branches, it failed to predicted high frequency branches properly. This result is evident since the original model did not consider structures with high energies while building the training set. After updating the model using on-the-fly machine learning techniques, it can predict phonon dispersion precisely, as shown in Fig. 4b. Even at high frequency regions, the phonon dispersion predicted by our model are consistent with those obtained from DFT calculations. In addition, since second-principles directly employs the DFPT results of the cubic phase as second order parameters, our model can accurately predicted phonon dispersion of cubic phase. This makes our model superior to existing MLFF based on GAP proposed in ref. 36, which has a large discrepancy on phonon dispersion with DFT results. It should be noticed that DP model can describe phonon dispersion more accurately than GAP18,39, but the phonon dispersion for BaTiO3 based on DP model hasn’t been reported yet. Furthermore, the phonon dispersion for tetragonal and orthorhombic phases are also consistent with DFT results, as shown in Fig. S2.

a Phonon dispersion for rhombohedral phase from DFT and second-principles model proposed in ref. 17. b Phonon dispersion for rhombohedral phase from DFT and machine learning assisted second-principles model. The solid lines are DFT results while dash lines are second-principles model results.

Thermal transport properties

The accuracy of phonon dispersion can also influence the properties associated with phonons. Since phonons are the main carrier of heat in the crystal, we now move to study thermal transport properties of BaTiO3 using the second principles model we have built. The thermal transport properties are obtained by solving the phonon Boltzmann transport equation using the Phono3py software package42,43. The lattice thermal conductivity \(\kappa\) at given temperature T is given by ref. 44:

Where \({k}_{B},{N},\,\Omega ,\,{f}_{0},\,{v}_{\lambda }^{\alpha },\,{\tau }_{\lambda }\) are the Boltzmann constant, number of k points, volume of unit cell, Bose-Einstein statistics, group velocity and phonon lifetime. The phonon lifetime and group velocity are obtained with IFCs, which are calculated based on supercell-based finite displacement difference method. Conventionally, IFCs are obtained through thousands of computation tasks using first-principles calculations, which is rather time consuming. Replacing first-principles calculations with second principles method can reduce time cost from months to hours45,46. The group velocity with non-analytical correction from second principles method and first principles calculations are shown in Fig. 5a. The results from second principles method consistent with first principles calculations indicates that the second principles model is accurate enough to study thermal transport properties of BaTiO3. The specific heat is given in Fig. 5b, it increases with temperature ranging from 43.03 to 121.93 J/K/mol.

a Group velocity from first-principles calculations and second-principles model. b Specific heat from second-principles model. c Temperature dependence of particle-like, wave-like and total lattice thermal conductivity. d Mean free path dependence of cumulative thermal conductivity at room temperature.

The recent studies show that both particle-like and wave-like thermal conductivity can coexist in perovskites47,48. However, as one of the most typical perovskite, wave-like thermal conductivity has never been reported before. The extent to which wave-like thermal conductivity contributes to heat transfer in BaTiO3, and whether it plays a critical role, remains unclear. Thus, we consider both particle-like and wave-like thermal conductivity in this work49. The thermal conductivity for rhombohedral BaTiO3 as a function of temperature is shown in Fig. 5c. Due to the effect from wave-like thermal conductivity, the lattice thermal conductivity departure from the standard \({\kappa }_{L}\propto {T}^{-1}\) law and has a \({\kappa }_{L}\propto {T}^{-0.933}\) dependence. The wave-like thermal conductivity increases with temperature, however, particle-like thermal conductivity still dominants. The mean free path dependence cumulative \({\kappa }_{L}\) at room temperature is given in Fig. 5d. It can be seen clearly that 90% of thermal conductivity are contribute by phonons with mean free paths shorter than 40 nm. This indicates that to accurately measure the thermal conductivity of BaTiO3 experimentally, the size of domains as well as thickness of sample should be larger than 40 nm50.

Structural phase transitions

Finally, we investigated the temperature-dependent phase transition of BaTO3. The polarization as a function of temperature from our previous model and machine learning assisted model are shown in Fig. 6a. When the temperature is lower than 170 K, the polarization is along [111] direction, which corresponding to rhombohedral phase. A sudden decrease in Py at 170 K indicates a phase transition from rhombohedral to orthorhombic. Subsequently, the phase transition from orthorhombic to tetragonal occurs at 190 K, followed by phase transition from tetragonal to cubic at 230 K. Comparing to our previous model in ref. 17, this machine learning assisted second principles model also reproduced phase transition sequence of BaTiO3. However, the phase transition temperature is still underestimated, which is the same as the previous model. This underestimation in phase transition temperature has been attributed to high-order terms in the effective Hamiltonian method51. But in this work, we also introduced high-order terms during the fitting procedure instead of the bounding procedure and the phase transition temperature is still underestimated. A recent study found that the improvement of phase transition temperature originates from the anharmonic intersite interactions37, however, our second principles model also included anharmonic interactions between neighbor cells. Thus, the experience of effective Hamiltonian method in adjusting phase transition temperature can’t be applied to the second-principles model. Moreover, since this model includes more configurations and is more accurate than the previous model, we can conclude that the accuracy of the second principles model is not the reason for the underestimation of phase transition temperature. Thus, the underestimation can be attributed to the parameters used in first-principles calculations. Furthermore, we built a second-principles model with LDA as the electron exchange-correlation potential, the comparison on energies from DFT and the second-principles model are given in Fig. S3. The polarization as a function of temperature is shown in Fig. 6b. Although our simulation stopped at 500 K, we can still find that the phase transition temperature is much higher than that from Perdew-Burke-Enzerh parametrization for solids (PBEsol), which indicates that modifying the exchange-correlation functional has a significant influence to the phase transition temperature. The double well energy at zero temperature from LDA-based second-principles model and the PBEsol-based second-principles model are given in Fig. 7. The potential well from LDA is much deeper than that of PBEsol, and leads to a higher phase transition temperature. This work is only a preliminary exploration on how DFT parameters can influence the phase transition temperature and further efforts based on different exchange-correlation functional, pseudopotential, cut-off energy, and even software packages are suggested.

a Polarization as a function of temperature from the second-principles model with PBEsol. R, O, T, C represent the temperature range for rhombohedral, orthorhombic, tetragonal and cubic phases separately. b Polarization changes with temperature from the second-principles model with LDA. The phase transition from rhombohedral to orthorhombic and orthorhombic to tetragonal occurs at 440 K and 490 K. We did not observe phase transition from tetragonal to cubic since the simulation stopped at 500 K.

Discussion

In summary, we proposed an on-the-fly machine learning scheme to generate a second-principles model. The MD simulations are carried out to obtain the forces, energies, and stresses for numerous structures. The Bayesian errors for these structures are calculated and used as a criterion for determining whether to perform first principles calculations. The training set for second principles keeps updating during MD simulations. By progressively increasing the temperature in MD simulations, the applicability of the model gradually enhanced. Such machine learning scheme offers an efficient way to build second second-principles model and finally we obtained an accurate second-principles model for BaTiO3. The energies, structure and phonon dispersion for ground state is significantly improved comparing to the previous model, which validated the effectiveness of this method. In addition, the high accuracy of this model, combined with its rapid computational speed, allow us to study thermal transport properties of BaTiO3. A weak wave-like contribution to the thermal conductivity is found. After investigate phase transition characters of BaTiO3, we found that due to the difference in the depth of the potential well, the exchange-correlation functional can significantly influence phase transition temperatures than other characters in the second principles model. Finally, since the scheme proposed in this work is universal, we believe that this has the potential to become a universal working paradigm for the second-principles model of perovskite. Further efforts are suggested to apply this method on BaTiO3 with other DFT parameters or other materials.

Methods

First-principles calculations

All the first-principles calculations are carried out using the ABINIT package52,53. We employed the generalized gradient approximation with the revised PBEsol54 and optimized norm-conserving pseudopotentials from the PseudoDojo server55,56. The energy cutoff is selected to be 40 Ha. The following valence electrons for Ba(5s25p66s2), Ti(3s23p63d24s2), and O(2s22p4) are used. The Brillouin zone is sampled with an 8 × 8 × 8 k-point grid for a unit cell and a 4 × 4 × 4 k-point grid for a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell. The phonon dispersions from DFT are calculated using ANADDB57,58 or PHONOPY program59,60.

Second-principles calculations

The second-principles method is an approach to construct an effective atomic potential based on first-principles calculations. It’s built based on individual atomic displacements, and Taylor expansion of the Born-Oppenheimer energy around the reference structure (e.g., cubic phase of BaTiO3 in this work). The total energy can be expressed as15:

where \({E}_{p}\left\{{u}_{i}\right\}\) is the energy from atomic displacement, \({E}_{s}\left\{\eta \right\}\) is the elastic energy and \({E}_{s-p}\left\{{u}_{i},\eta \right\}\) is the coupling between atomic displacement and strain. Furthermore, the acoustic sum rule is meet by writing energy in terms of atomic displacements difference. The first term \({E}_{p}\) can be written as:

Since the reference structure is a stationary point of potential energy surface, there is no first order terms. \({K}_{i\alpha j\beta k\gamma \ldots }^{\left(n\right)}\) is the parameter tensor for the n-th derivatives of the potential energy. The second term \({E}_{s}\) is elastic energy, and can be written as:

where N is the number of unit cells, \({C}^{(m)}\) is the bare elastic tensor of order m. The last term is the coupling between phonons and strain, it can be written as:

Where \({\hat{\Lambda }}^{\left(m,n\right)}\) is the coupling tensor of order m in strain and n in the atomic displacements. In Eqs. (2–5), the absence of first-order terms is due to the chosen reference structure being a stationary point on the potential energy surface, and energy terms related to atomic displacements appear in the form of displacement differences to meet wth the acoustic sum rule.

In this work, the Taylor expansion is truncated at the sixth order and the cutoff for short-range interaction is \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}{a}_{0}\) = 2.89 Å, where a0 is the lattice parameter of the cubic reference structure. All the harmonic parameters were directly calculated from DFT, and the most relevant 96 terms were selected and their coefficients were fitted from the energy, forces and stresses of the configurations in a first-principles training set. Conventionally, the fitting procedures are carried out using the least square algorithm with the software MULTIBINIT, which is released within the ABINIT package. In this work, however, we employed Bayesian linear regression31 to determine the parameters of the anharmonic terms.

Bayesian linear regression and Bayesian error

The feasibility of the Bayesian linear regression approach relies on the linear dependence of the model energy (as well as forces and stress) on the anharmonic coefficients, as illustrated by the following linear equation:

where \({E}^{{harmonic}}\) is the energy contribution from the harmonic part of the model, which depends on the coefficients directly derived from first principles calculations and is therefore fixed during the fitting procedure. \({N}_{{term}}\) is the number of anharmonic terms in the second principles model, which is selected to be 96 in this work. \({\omega }_{\zeta }\) is the parameter for the \(\zeta\)-th anharmonic term, and \({\tau }_{\zeta }\) is the energy term dependent on the parameter \({\omega }_{\zeta }\). It should be noticed that the anharmonic part in Eq. (5) is linearly dependent on the parameters19, which guarantee the application of the Bayesian linear regression algorithm. These linear equations can be written into a matrix form:

Here \({y}_{a}\) is a \({m}_{\alpha }\)-dimensional column vector containing the energy, forces, and stresses for \(a\)-th structure, where \({m}_{\alpha }=1+3{N}_{a}+6\), \({N}_{a}\) is the number of atoms in structure \(a\). The column vector \({\boldsymbol{\omega }}\) is comprised of \({\omega }_{\zeta }\), and \({{\boldsymbol{\phi }}}_{a}\) is a \({m}_{\alpha }\times {N}_{{term}}\) matrix. The energies, forces and stresses for all the structures in the training set \({\boldsymbol{Y}}\) can be built by aggregating all the \({{\boldsymbol{y}}}_{a}\) vectors. Similarly, the collection of all matrices \({{\boldsymbol{\phi }}}_{a}\) results in \({\mathbf{\Phi }}\), and we can have:

In this form, the fitting procedure is to adjust \({\boldsymbol{\omega }}\) to fit \({\mathbf{\Phi }}{\boldsymbol{\omega }}\) against \({\boldsymbol{Y}}\). In the conventional schemes, the parameters \({\boldsymbol{\omega }}\) are optimized to minimize goal functions, which takes the form of the least square approach17. While in this work, we introduce the Bayesian linear-regression method31 to optimize \({\boldsymbol{\omega }}\). We assumed that \({{\boldsymbol{y}}}_{a}\) deviates from the \({{\boldsymbol{\phi }}}_{a}{\boldsymbol{\omega }}\) with a distribution described by a Gaussian function with a covariance matrix of \({\sigma }_{v}^{2}{\boldsymbol{I}}\), and prior probability to find the vector is also described by a Gaussian distribution with a mean vector at zero and a covariance matrix of \({\sigma }_{w}^{2}{\boldsymbol{I}}\):

Based on these two assumptions and the Bayesian theorem61, the posterior distribution of the parameter can be written as:

Where \(\bar{{\boldsymbol{\omega }}}\) is the center of the distribution, and \({\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}\) is the variance. \({\sigma }_{w}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{v}^{2}\) are the hyperparameters, and they are determined by evidence approximation31,61. Given the observation of the training set, the posterior distribution of the energy, forces, and stress of a new structure is also shown to be a Gaussian distribution:

The uncertainty of the prediction on the new structure can be measured by the covariance matrix:

Following ref. 37, the diagonal elements of the second term is used as the Bayesian error. If the Bayesian error is large, the prediction on the new structure is unreliable, and the first principles calculations need to be carried out to update the training set. Comparing to the conventional scheme, evaluation of the uncertainty allows us locate the structure needs to be calculated with first principles, and make our scheme much more efficient.

On the fly machine learning scheme

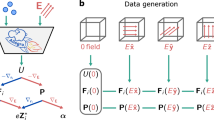

In our scheme, the first principles calculation, parameters optimization are carried out on the fly during the MD simulations, and the whole procedure is automated. The flowchart of our scheme is shown in Fig. 8 and outlined below:

-

(1)

The second principles model is generated with the initial training set.

-

(2)

MD simulations are carried out starting from rhombohedral, orthorhombic, and tetragonal phase at given temperature for 1000 steps. The Bayesian errors for these 3000 structures are calculated.

-

(3)

If the local maximum Bayesian error is larger than 0.1, execute the first principles calculations and update the training set. Generate a new second principles model and go back to step 2. If all the Bayesian error is smaller than 0.1, the current second principles model is regarded as reliable at the current temperature, and go back to step 2 with a higher temperature.

-

(4)

When the temperature is higher than 300 K, the procedure is completed and a on the fly machine learning generated second principles model is obtained.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is available at: https://github.com/Tinrry/thermal_conductivity.

References

A century of ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 19, 129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-0611-1 (2020).

Valasek, J. Piezo-electric and allied phenomena in Rochelle salt. Phys. Rev. 17, 475–481 (1921).

Xu, T. et al. Ultrahigh-density polar vortex lattice in square-shaped moiré bilayers of lead chalcogenides. Nano Lett. 24, 14736–14742 (2024).

Martin, L. W. & Rappe, A. M. Thin-film ferroelectric materials and their applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16087 (2016).

Mischenko, A. S., Zhang, Q., Scott, J. F., Whatmore, R. W. & Mathur, N. D. Giant electrocaloric effect in thin-film PbZr0.95Ti0.05O3. Science 311, 1270–1271 (2006).

Bag, S. P., Hou, X., Zhang, J., Wu, S. & Wang, J. Negative/positive electrocaloric effect in single-layer Pb(ZrₓTi1−x)O₃ thin films for solid-state cooling device. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1769–1775, https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2020.2976163 (2020).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Raffaele, R. Ab initio simulation of the properties of ferroelectric materials. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 11, R69 (2003).

Zhu, Y. et al. Linear-superelastic Ti-Nb nanocomposite alloys with ultralow modulus via high-throughput phase-field design and machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 205 (2021).

Zhong, W., Vanderbilt, D. & Rabe, K. M. Phase-transitions in BaTiO3 from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1861 (1994).

Zhong, W., Vanderbilt, D. & Rabe, K. M. First-principles theory of ferroelectric phase transitions for perovskites: the case of BaTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 52, 6301–6312 (1995).

Qi, Y., Liu, S., Grinberg, I. & Rappe, A. M. Atomistic description for temperature-driven phase transitions in BaTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 94, 134308 (2016).

Deringer, V. L., Caro, M. A. & Csányi, G. Machine learning interatomic potentials as emerging tools for materials science. Adv. Mater. 31, 1902765 (2019).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Wojdeł, J. C., Hermet, P., Ljungberg, M. P., Ghosez, P. & Íñiguez, J. First-principles model potentials for lattice-dynamical studies: general methodology and example of application to ferroic perovskite oxides. J. Phys. 25, 305401 (2013).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., He, X., Wang, J. & Ghosez, P. Rare-earth control of phase transitions in infinite-layer nickelates. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad108 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Structural phase transitions and dielectric properties of BaTiO3 from a second-principles method. Phys. Rev. B 108, 134117 (2023).

Zhang, H., Chao, C.-H., Bastogne, L., Sasani, A. & Ghosez, P. Tuning the energy landscape of CaTiO3 into that of antiferroelectric PbZrO3. Phys. Rev. B 108, L140304 (2023).

Escorihuela-Sayalero, C., Wojdeł, J. C. & Íñiguez, J. Efficient systematic scheme to construct second-principles lattice dynamical models. Phys. Rev. B 95, 094115 (2017).

Pereira Gonçalves, M. A., Escorihuela-Sayalero, C., Garca-Fernández, P., Junquera, J. & Íñiguez, J. Theoretical guidelines to create and tune electric skyrmion bubbles. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau7023 (2019).

Zubko, P. et al. Negative capacitance in multidomain ferroelectric superlattices. Nature 534, 524–528 (2016).

Wang, H., Zhang, L. & Han, J. DeePMD-kit: a deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Schütt, K. et al. SchNet: a continuous-filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. In Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 992–1002 (Curran Associates Inc., 2017).

Schütt, K. T., Arbabzadah, F., Chmiela, S., Müller, K. R. & Tkatchenko, A. Quantum-chemical insights from deep tensor neural networks. Nat. Commun. 8, 13890 (2017).

Bartók, A. P., Payne, M. C., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. Gaussian approximation potentials: the accuracy of quantum mechanics, without the electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136403 (2010).

Behler, J. Representing potential energy surfaces by high-dimensional neural network potentials. J. Phys. 26, 183001 (2014).

Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: a class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. Multiscale Model. Simul. 14, 1153–1173 (2016).

Cheng, B. Latent Ewald summation for machine learning of long-range interactions. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 80 (2025).

Zhang, L. et al. A deep potential model with long-range electrostatic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 124107 (2022).

Jinnouchi, R., Lahnsteiner, J., Karsai, F., Kresse, G. & Bokdam, M. Phase transitions of hybrid perovskites simulated by machine-learning force fields trained on the fly with Bayesian inference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 225701 (2019).

Jinnouchi, R., Karsai, F. & Kresse, G. On-the-fly machine learning force field generation: application to melting points. Phys. Rev. B 100, 014105 (2019).

Vandermause, J. et al. On-the-fly active learning of interpretable Bayesian force fields for atomistic rare events. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 20 (2020).

Dai, M., Zhang, Y., Fortunato, N., Chen, P. & Zhang, H. Active learning-based automated construction of Hamiltonian for structural phase transitions: a case study on BaTiO3. J. Phys. 37, 055901 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. A concurrent learning platform for the generation of reliable deep learning based potential energy models. Comput. Phys. Commun. 253, 107206 (2020).

Yu, M., Zhao, Z., Guo, W. & Zhang, Z. Fracture toughness of two-dimensional materials dominated by edge energy anisotropy. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 186, 105579 (2024).

Gigli, L. et al. Thermodynamics and dielectric response of BaTiO3 by data-driven modeling. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 209 (2022).

Ma, X. et al. Active learning of effective Hamiltonian for super-large-scale atomic structures. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 70 (2025).

Tinte, S., Íñiguez, J., Rabe, K. M. & Vanderbilt, D. Quantitative analysis of the first-principles effective Hamiltonian approach to ferroelectric perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 67, 064106 (2003).

He, R. et al. Structural phase transitions in SrTiO3 from deep potential molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 105, 064104 (2022).

He, R. et al. Ultrafast switching dynamics of the ferroelectric order in stacking-engineered ferroelectrics. Acta Mater. 262, 119416 (2024).

Kwei, G. H., Lawson, A. C., Billinge, S. J. L. & Cheong, S. W. Structures of the ferroelectric phases of barium titanate. J. Phys. Chem. C 97, 2368–2377 (1993).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Togo, A., Chaput, L. & Tanaka, I. Distributions of phonon lifetimes in Brillouin zones. Phys. Rev. B 91, 094306 (2015).

Ren, Q., Li, Y., Lun, Y., Tang, G. & Hong, J. First-principles study of the lattice thermal conductivity of the nitride perovskite LaWN3. Phys. Rev. B 107, 125206 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Quantification of switchable thermal conductivity of ferroelectric materials through second-principles calculation. Mater. Today Phys. 41, 101347 (2024).

Seijas-Bellido, J. A., Aramberri, H., Íñiguez, J. & Rurali, R. Electric control of the heat flux through electrophononic effects. Phys. Rev. B 97, 184306 (2018).

Wu, Y. et al. Ultralow lattice thermal transport and considerable wave-like phonon tunneling in chalcogenide perovskite BaZrS3. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 11465–11473 (2023).

Tong, Z. et al. Predicting the lattice thermal conductivity in nitride perovskite LaWN3 from ab initio lattice dynamics. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205934 (2023).

Simoncelli, M., Marzari, N. & Mauri, F. Wigner formulation of thermal transport in solids. Phys. Rev. X 12, 041011 (2022).

Liu, C., Chen, Y. & Dames, C. Electric-field-controlled thermal switch in ferroelectric materials using first-principles calculations and domain-wall engineering. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 044002 (2019).

Mayer, F. et al. Improved description of the potential energy surface in BaTiO3 by anharmonic phonon coupling. Phys. Rev. B 106, 064108 (2022).

Torrent, M., Jollet, F., Bottin, F., Zérah, G. & Gonze, X. Implementation of the projector augmented-wave method in the ABINIT code: application to the study of iron under pressure. Comput. Mater. Sci. 42, 337–351 (2008).

Gonze, X. A brief introduction to the ABINIT software package. Z. Krist. 220, 558–562 (2005).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Hamann, D. R. Optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085117 (2013).

van Setten, M. J. et al. The PseudoDojo: training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Comput. Phys. Commun. 226, 39–54 (2018).

Gonze, X. First-principles responses of solids to atomic displacements and homogeneous electric fields: implementation of a conjugate-gradient algorithm. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10337–10354 (1997).

Gonze, X. & Lee, C. Dynamical matrices, Born effective charges, dielectric permittivity tensors, and interatomic force constants from density-functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10355–10368 (1997).

Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tadano, T. & Tanaka, I. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys. 35, 353001 (2023).

Togo, A. First-principles phonon calculations with phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, 012001 (2022).

Bishop, C. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Springer, 2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12302208 and 12432007) and the National Program on Key Basic Research Project (Grant No. 2022YFB3807601).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. and X.G. supervised this project. J.T.Z. and H.H.Z. carried out the calculation. J.T.Z., H.Z.Z., and B.X. analysis the result and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Zhang, H., Zheng, H. et al. On-the-fly machine learning-assisted high accuracy second-principles model for BaTiO3. npj Comput Mater 11, 299 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01787-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01787-z