Abstract

The discovery and optimization of high-energy materials (HEMs) face challenges due to the computational expense and slow iteration of traditional methods. Neural network potentials (NNPs) have emerged as an efficient alternative to first-principles simulations. This study presents EMFF-2025, a general NNP model for C, H, N, and O-based HEMs, leveraging transfer learning with minimal data from DFT calculations. The model achieves DFT-level accuracy, predicting the structure, mechanical properties, and decomposition characteristics of 20 HEMs. Integrating EMFF-2025 with PCA and correlation heatmaps, we map the chemical space and structural evolution of these HEMs across temperatures. Surprisingly, EMFF-2025 uncovers that most HEMs follow similar high-temperature decomposition mechanisms, challenging the conventional view of material-specific behavior. EMFF-2025 offers a versatile computational framework for accelerating HEM design and optimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mechanical stability and energy release mechanisms of high-energy materials (HEMs) composed of C, H, N, and O elements have been a long-standing focus of global research1,2,3. These HEMs are widely used in aerospace propulsion, explosive engineering, and emerging energy storage systems due to their high energy density, rapid reactivity, and controllable energy release characteristics1,3,4,5. In particular, their structural design and performance tuning play a critical role in ensuring safety and enhancing application performance in areas such as high-energy fuels, green propellants, and energetic polymers3,6,7. Traditional experimental methods are time-consuming and costly, often relying on trial-and-error and expensive equipment8,9. Analyzing large amounts of experimental data to uncover potential patterns also demands significant time and resources, making it difficult to reveal underlying physicochemical laws10. HEMs exhibit complex intrinsic mechanisms, with reactions and properties influenced by various factors, especially under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions, where experimental validation is challenging11,12. Studying the low-temperature stability and high-temperature energy release mechanisms of HEMs requires not only experimental methods but also advanced computational and simulation techniques13.

Computational methods based on molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which model atomic motion using Newtonian physics, enable material reaction simulations at the atomic scale, significantly improving the efficiency of material performance prediction and reducing costs14,15,16. However, classical force fields struggle to accurately describe bond formation and breaking processes and typically require reparameterization for specific systems17,18. While quantum mechanical methods provide precise computational results, their computational cost makes large-scale dynamic simulations impractical19,20. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a fast, accurate, and generalizable reactive force field (ReaxFF) model capable of precisely describing the key intrinsic physicochemical processes of HEMs and supporting multiscale simulations from atomic to macroscopic level. In this context, the ReaxFF model has undergone extensive development over the past two decades and has been widely applied to the study of decomposition and combustion processes of HEMs21,22,23,24,25,26. ReaxFF utilizes bond-order-dependent polarization charges to model both reactive and non-reactive atomic interactions25,27, and parameterizes interatomic interactions through complex functional forms. However, despite its success in numerous applications, ReaxFF still struggles to achieve the accuracy of density functional theory (DFT) in describing reaction potential energy surfaces (PES), particularly when applied to new molecular systems. Even the most advanced versions of ReaxFF may exhibit well-documented deficiencies28, often leading to significant deviations18,29.

In recent years, machine learning (ML) potential models have been demonstrated to overcome the long-standing trade-off between computational accuracy and efficiency in physics-based models13,30, and have been applied to computational materials discovery18,30,31. In particular, graph neural network (GNN)-based approaches, such as ViSNet32,33 and Equiformer34, have effectively enhanced the accuracy and extrapolation capabilities of models by incorporating physical symmetries such as translation, rotation, and periodicity, providing a promising alternative to traditional neural network potentials (NNP) in certain systems. However, the advantages of GNN models are more evident in specific types of material systems, particularly in capturing local structural information and handling high-dimensional data34,35. Among the various ML models developed, Deep Potential (DP scheme) method36,37, based on NNP framework, has shown exceptional capabilities in modeling isolated molecules36, multi-body clusters38,39, and solid materials40,41. While GNN architectures show great potential in small molecule and crystalline material systems42,43, the DP framework remains a more scalable and robust choice for addressing complex reactive chemical processes and large-scale system simulations. The DP scheme provides atomic-scale descriptions of complex reactions, offering suitability for investigating extreme physicochemical processes44,45, oxidative combustion46, and explosion phenomena47,48. As such, it is considered a promising candidate for the development of a general-purpose NNP. Currently, several ML models have been developed to investigate the reaction chemistry of C, H, N, and O systems in both condensed-phase and gas-phase (vacuum) environments49,50,51. For example, Zhang et al.50 developed a general ML interatomic potential (ANI-nr) for the condensed-phase reactions of organic compounds containing C, H, N, and O elements, which shows excellent agreement with experimental results and previous studies using traditional quantum chemical methods in various condensed-phase chemical reactions. Yoo et al.51 developed a neural network reaction force field (NNRF) for the CHNO system, successfully predicting dissociation curves, monomer formation energies, and forces. This method demonstrated good consistency with experimental results in the high-temperature decomposition study of 1,3,5-trinitroperhydro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) as a representative example, particularly in terms of product distribution and activation energy. The NNRF method can be extended to other HEMs and used to study complex reactions with DFT-level accuracy. However, existing studies primarily focus on accurately capturing chemical reaction mechanisms or PES landscapes, while their applicability to HEMs remains limited, particularly in terms of the comprehensive prediction of both mechanical properties and chemical reactivity. While the training and calibration methods for reaction chemistry are relatively straightforward, automating the exploration of reactive chemical space during sampling is highly challenging, as it requires the simultaneous exploration of molecular species changes and structural variations associated with non-equilibrium thermodynamic processes. Therefore, a general NNP model for large-scale condensed-phase reaction chemistry specific to C, H, N, and O elements-based HEMs would provide a critical balance in predicting both low-temperature mechanical and high-temperature chemical properties. Our recent research demonstrates that NNPs can serve as a critical bridge, integrating electronic structure calculations, first-principles simulations, and multiscale modeling48,52,53. This approach describes mechanical, chemical, and thermal processes in various systems with DFT-level precision while being more efficient than traditional force fields and DFT calculations52,53,54,55, sometimes providing semi-quantitative property predictions52,54,55.

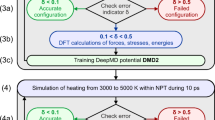

Most ML projects rely on supervised learning56, which plays a key role in computation-driven material development15,30,36. However, the need for large datasets and high computational costs limits its practicality57. To address this, we explore more efficient modeling approaches that maintain accuracy while reducing time and cost. Transfer learning and pre-trained models have gained attention as effective strategies for optimizing ML models58,59. Transfer learning leverages existing data, reducing the need for extensive training, accelerating learning, and improving performance58. For example, Wang et al.59 constructed a training database based on DFT calculation and trained a machine-learning interatomic potential using the Deep Potential generator (DP-GEN) framework60, successfully reproducing DFT results. Despite the absence of explicit surface configurations in the training process, the potential accurately predicts Au (111) surface reconstruction and Au segregation in Ag-Au nanoalloys, demonstrating its remarkable generalization capability. In our previous work52, we developed an NNP model (named DP-CHNO-2024 model) for the three components of RDX, 1,3,5,7-Tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocane (HMX), and 2,4,6,8,10,12-hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20), which is capable of describing their mechanical and thermal decomposition properties. However, its transferability to other HEMs remained uncertain. In this work, we propose a pioneering, scalable, and widely applicable general NNP framework, with the development strategy outlined in Fig. 1. The NNP model, obtained through a pre-trained NNP model and transfer learning scheme, enables MD simulations of condensed-phase HEMs to achieve chemical accuracy.

Top is the pre-trained model (DP-CHNO-2024) taken from our previous work52. The bottom highlights the training strategy of EMFF-2025 model.

Based on the pre-trained DP-CHNO-2024 model and transfer learning strategy, we have developed a general-purpose NNP (EMFF-2025 model), specifically designed for predicting the mechanical properties at low temperatures and chemical behavior at high temperatures of condensed-phase HEMs containing C, H, N, and O elements. The model combines high accuracy with high efficiency, and it can be built by incorporating a small amount of new training data from structures not included in the existing database through the DP-GEN process. We aim to achieve effective construction and characterization of the complex chemical space of HEMs using the EMFF-2025 model, with a particular focus on its ability to maintain physical consistency, predictive accuracy, and extrapolation capability in structurally complex and compositionally diverse systems. This serves to provide reliable support for understanding the thermal stability and reaction mechanisms of HEMs. In this work, we have validated the atomic energy and force predictions of the EMFF-2025 model through comparison with DFT calculations and further applied the model to predict the crystal structures, mechanical properties, and thermal decomposition behaviors of 20 HEMs. The results have been rigorously benchmarked against experimental data. Additionally, we have introduced principal component analysis (PCA) and correlation heatmap analysis to explore the intrinsic relationships and formation mechanisms of structural motifs in the chemical space of HEMs. This approach provides a comprehensive assessment of the structural stability and reactive characteristics of HEMs, showcasing the broad applicability of this model in studying the physicochemical space and thermal decomposition behaviors of HEMs.

Results

Validation of EMFF-2025 model

Figure 2 presents a systematic evaluation of the performance of the EMFF-2025 model in predicting energies and forces, based on the training dataset with a batch size of 200. As shown in Fig. 2(a), the energy and force predictions for 20 HEMs are closely aligned along the diagonal, indicating excellent fitting accuracy. Furthermore, Fig. 2(b) and S3 show that the mean absolute error (MAE) for energy is predominantly within ± 0.1 eV/atom, and the MAE for force is mainly within ± 2 eV/Å. These results suggest that the EMFF-2025 model is capable of making strong predictions across a wide temperature range. In contrast, when predictions are made using our pre-trained model52 for these HEMs, significant deviations in the energy and force distributions are observed (see Figs. S1, S4, and S5), for HEMs such as BTF, TAGN, NG, TEX, BTTN, NC, TNB, and HNS. While reasonably accurate predictions of energy and forces are made for HEMs like RDX, HMX, and CL-20, the overall generalization ability of the pre-trained model is limited, and it cannot be directly applied to other HEM systems. Additionally, the previously developed general-purpose large-atom model, DPA-2 (based on the DP scheme)61, was used to predict the energy and forces of the 20 HEMs. As shown in Fig. S6, while accurate force predictions are made for most systems, energy predictions are poorly performed, especially at high temperatures. This further indicates that the applicability of DPA-2 to HEM systems is limited.

Energy (eV/atom) and forces (eV/Å) predictions (a), distribution of energy and forces in the training set (b), and MAE of energy and forces for single components (c). In c, the dashed lines in the figure represent the MAE of energy and force predictions by the EMFF-2025 model for 20 HEMs compared to DFT results, corresponding to 0.03 eV/atom and 0.54 eV/Å, respectively.

Figures 2c and S2 show the energy and force predictions of the EMFF-2025 model for individual HEMs. For energy, the MAE between predicted values and DFT calculations is below 65.2 meV/atom, with the maximum observed in the case of TKX-50. For atomic forces, the MAE is below 0.684 eV/Å, with the maximum observed in the case of TATB. Notably, due to transfer learning from a pre-trained model52, the EMFF-2025 predicts energies of 0.0113, 0.0422, and 0.0237 eV/atom, and forces of 0.306, 0.588, and 0.510 eV/Å for RDX, HMX, and CL-20 crystals, respectively. This accuracy is consistent across all components, demonstrating that the EMFF-2025 model can precisely describe atomic-scale decomposition reactions in both finite and extended systems of energetic materials while maintaining DFT-level precision. To comprehensively evaluate the performance of EMFF-2025 under diverse conditions, we not only compared it with a pre-trained model and the general-purpose DPA-2 model, but also analyzed its prediction errors under varying temperature conditions (Figs. S7–S9). The results show that EMFF-2025 consistently maintains high accuracy in predicting both energies and forces. Although prediction errors gradually increase with temperature, the model still performs well under high-temperature conditions. These findings indicate that EMFF-2025 effectively captures the temperature dependence of energy and force predictions, enabling reliable modeling of HEM behavior in extreme environments. Furthermore, to assess the cross-framework transferability of the constructed training dataset, we applied it to the latest GNN framework, DeePMD-GNN43. The results demonstrate that the dataset can be seamlessly integrated into this framework while maintaining excellent predictive performance (shown in Fig. S10). This not only reflects the high quality and consistency of the dataset but also confirms its broad applicability and robust adaptability across different model architectures.

Generalization capability of EMFF-2025 model

The generalization capability of the EMFF-2025 model is crucial for its practical application and is assessed through stability and extrapolation performance. Stability refers to the ability of the model to learn sufficient features from the data, ensuring that as more data is added, predictions remain consistent within the data range and do not diverge. Extrapolation performance, on the other hand, measures the prediction accuracy beyond the training data. These characteristics directly influence the robustness of the EMFF-2025 model in practical simulations. Figure 3 provides an in-depth evaluation of the stability and extrapolation performance of the EMFF-2025 model during the training process by comparing the MAE between the predicted energies and forces and the results of DFT calculations. In the stability and extrapolation tests of this section, different HEMs were introduced into the model according to the training sequence to assess the generalization ability of the model during the process of expanding the structural space. It is important to note that this study primarily focuses on evaluating the generalization capability of the NNP as the training set is expanded, while the cross-domain transferability between different structural categories remains an issue that warrants further investigation.

In the stability test (a), the training data of each HEM is sequentially added following the x-axis order, corresponding to the training iteration sequence (Table 2). In each case, a new HEM is introduced via the DPGEN processes, and an NNP is trained. Each column shows the MAE of NNP predictions for energy and forces relative to DFT results, averaged over the existing training set. In the extrapolation test (b), the current model predicts the training set of next HEM, and the corresponding MAE is calculated.

The EMFF-2025 model was initially developed based on the pre-trained models for RDX, HMX, and CL-20. Figure 3a presents the results of the stability test for the development of the EMFF-2025 model. In the stability test, the evolution of MAE predicted by NNP models is illustrated as new data is added. For example, the MAE of the NNP model is 0.057 eV/atom, considering training data from the cases of RDX, CL-20, HMX, and TNT, which is marked as the column of TNT. Regarding energy predictions, the MAE values for the model predictions of HEMs within the training set are consistently below 0.2 eV/atom compared to DFT calculations. In particular, the errors for RDX, HMX, and CL-20 are low (<0.082 eV/atom), while the addition of DNBF exhibits the highest error (0.156 eV/atom). As the type of HEMs increases, the energy errors fluctuate within a certain range without any noticeable divergence, indicating that the NNP model is robust enough to cover all the features in 20 HEMs. Following the trend of MAEs, a larger training dataset provides a better prediction performance. Besides, the good performance in stability tests may also indicate that the decomposition products of various HEMs share similarities to some extent. For force predictions, the MAE errors for most HEMs are below 0.5 eV/Å. Among all 20 HEMs, RDX exhibits the lowest error (0.251 eV/Å), while DNBF (0.545 eV/Å), HNS (0.51 eV/Å), and CL-20 (0.51 eV/Å) have relatively higher errors. These results demonstrate that the EMFF-2025 model performs well in terms of stability in both energy and force predictions. The error range does not show any significant divergence when adding more training data from different HEMs, effectively capturing the microscopic decomposition characteristics of HEMs at the DFT level.

In Fig. 3b, we evaluate the extrapolation capability of the EMFF-2025 model by assessing the predicted MAE for the next HEM which is not included in the training set using the current iterative model. Initially, the MAE values for predicting the energy and force of TNT (the first HEM not included in the initial training set) compared to DFT calculations were 1.08 eV/atom and 0.97 eV/Å, respectively. Such large discrepancy questions the performance of the pre-trained model on various HEMs. After including the TNT case in the training set, the extrapolation performance significantly improves, with reduced MAE values of energy and force for ADN as 0.632 eV/atom and 0.587 eV/Å, respectively. Further adding of ADN into the training set leads to an additional reduction in the MAE values for FOX-7, reaching 0.333 eV/atom (energy) and 0.553 eV/Å (force). Ultimately, the EMFF-2025 model yields an MAE of energy as 0.132 eV/atom for the 20th HEM (e.g., HNS), which fulfills the expectation for a general NNP. In summary, the EMFF-2025 model exhibits good stability and extrapolation performance, reliably predicting the energy and forces of various HEMs. This capability enables precise simulations of the structure, mechanical properties, and thermal decomposition behavior of condensed phase systems. In addition, Fig. S11 presents the energy and force MAE curves on the fixed validation set, showing a gradual improvement in model performance as iterations progress. This indicates that with the addition of more training data, the EMFF-2025 model exhibits stable improvements in predictive accuracy. Tables S2 and S3 also display the performance comparison of different iterative models (with the 0th iteration as the pretrained model and the 45th iteration as the final model) on the validation set, clearly demonstrating the continuous improvement in model performance due to the transfer learning loop. Through transfer learning, the EMFF-2025 model is able to continuously optimize its predictive capability, thereby enhancing its extrapolation ability to new and unseen samples.

Cell parameters prediction

Crystallographic parameters were predicted using DFT, EMFF-2025, and ReaxFF methods in Fig. 4 and Table S4. In Fig. 4, the crystal volumes obtained from DFT calculations closely match the experimental values62, with absolute deviations of less than 6%. The EMFF-2025 model generally shows good agreement with both experimental and DFT results. The predicted crystal volumes deviate by no more than 16% from experimental data and by less than 14% from DFT calculations. The largest deviation from experimental data is observed for BTF (16%), followed by ADN (15%) and TAGN (14%). Compared to DFT calculations, TKX-50 shows the highest deviation (14%), while BTF, ADN, and TAGN also exhibit deviations of 10%. In contrast, ReaxFF exhibits significantly larger deviations, ranging from 9% to 29% compared to experimental data and from 5 to 26% compared to DFT results. The largest discrepancies are observed for TAGN, with deviations of 29% and 26% relative to experimental and DFT values, respectively. Therefore, the EMFF-2025 model provides more accurate crystal volume predictions than the ReaxFF model for most HEMs, particularly for NC, TEX, DNBF, DTTO, and HMX, where its deviations are consistently smaller than those of ReaxFF.

a Predicted volumes (Å3) of HEM crystals. The absolute error between the predicted and experimental volumes is shown in (b) and expressed as a relative percentage. Experimental values are taken from the CCDC database62, DFT calculations were performed at the PBE/DZVP-MOLOPT level using CP2K82, and ReaxFF parameters were taken from Liu et al.27. The suffix “DFT” and “Exp.” refer to the volumes obtained from DFT calculations and experimental measurements, respectively.

Table S4 presents the detailed crystallographic parameters of all HEM crystals predicted using experimental data, DFT, EMFF-2025, and ReaxFF methods. The results indicate that the EMFF-2025 model predicts the three lattice parameters (a, b, and c) with average absolute deviations within 6% and 8% relative to experimental and DFT results, respectively. The performance outperforms the ReaxFF model, which exhibits deviations within 12%. However, for the crystallographic parameters of BTF, the EMFF-2025 model shows slightly larger errors than ReaxFF, with deviations of 5% (EMFF-2025) vs. 4% (ReaxFF) for the lattice parameters and 16% (EMFF-2025) vs. 14% (ReaxFF) for the crystal volume. Despite this exception, the EMFF-2025 model demonstrates superior performance for the majority of HEMs, achieving DFT-level accuracy in reproducing crystallographic structural parameters.

Equation of State (EOS) prediction

The capability of the EMFF-2025 model to reproduce the microscopic mechanical behavior of common HEMs is validated. The Equation of State (EOS) for all HEMs was obtained using DFT, EMFF-2025, and ReaxFF methods, and the mechanical behavior was extrapolated under compression (0.80–0.92) and tension (1.08–1.20). Figure 5 presents the EOS for representative ionic, chain, cyclic, and cage-like HEMs.

EOS curves for representative HEM crystals with various structural types: ionic (ADN and TAGN), chain (FOX-7 and NG), cyclic (RDX and DTTO), and cage (CL-20 and TEX). “EMFF-2025” refers to the EMFF-2025 model developed in this study. “DFT” calculations are computed at the PBE/DZVP-MOLOPT level using CP2K82. The ReaxFF is taken from the work of Liu et al.27. The shaded area indicates the structures included in the training set.

In Fig. 5, EMFF-2025 model closely replicates DFT results, effectively identifying energy minima and performing well even for structures outside the training set. In contrast, ReaxFF, while predicting stable points reasonably well, shows significant deviations under tensile and compressive conditions, overestimating potential energy during compression (5–10 Å3/atom). This overestimation may create artificial high-energy regions, affecting explosion and impact studies. Additional results in Fig. S12 further highlight the superior EOS prediction of the EMFF-2025 model, closely aligning with DFT. Note that only tensile and compressive data of RDX, HMX, and CL-20 are considered in the pre-trained model. It is unexpected that the EMFF-2025 model inherits good prediction performance from the pre-trained model in describing mechanical behavior under varying stress conditions.

Thermal decomposition simulation

Another goal of the EMFF-2025 model is to support molecular simulations of the thermal decomposition of HEMs. MD simulations using the EMFF-2025 model and ReaxFF were conducted from 300 to 3000 K to extract major decomposition products. Figure 6 shows the types and quantities of key products for eight representative HEMs, including ionic (ADN, TAGN), chain (FOX-7, NG), cyclic (RDX, DTTO), and cage (CL-20, TEX) structures. The simulation results for all 20 HEMs are presented in Fig. S13.

In Fig. 6, the main thermal decomposition products of ionic structures ADN (NH4N3O4) include H2O (37.4%), N2 (30.1%), and NO2 (9.7%), closely matching ReaxFF results with slight differences in N2, NO2, and NO quantities. These findings align with thermogravimetry-differential thermal analysis-mass spectrometry-infrared spectroscopy (TG-DTA-MS-IR) experimental data from Izato et al.63, which identified H2O, N2, NO2, NO, N2O, and HNO2 as key gases. Similarly, TAGN (CN6H9NO3), another ionic structure, decomposes into CO2 (40.1%), H2O (30.0%), N2 (12.8%), and H2 (4.3%), with ReaxFF predictions at a similar level. Experimental studies report a decomposition temperature of ~580.28 K for TAGN64,65, while our model predicts 780.6 K, considering a much higher heating rate. Notably, ReaxFF simulations show premature structural breakdown (<500 K) in these salts, highlighting the reliability of the EMFF-2025 model in predicting thermal decomposition behavior.

For chain HEMs, FOX-7, and NG serve as representatives. FOX-7 decomposes mainly into N2 (32.8%), H2O (27.6%), and CO2 (22.8%). The key difference from ReaxFF results lies in CO2 content, as ReaxFF predicts an excessive presence of the structurally unreasonable C2O3, whereas the EMFF-2025 model aligns with AIMD simulations by Liu et al.66, which identified H2O, CO2, and N2 as the primary products, with CO2 content close to or slightly lower than N2. The EMFF-2025 model predictions match experimental findings reporting H2O, N2, CO2, NO, NO2, NH3, H2, and CHNO67,68. For NG, the EMFF-2025 model predicts CO2 (37.1%), H2O (28.9%), N2 (14.5%), and NO (6.3%), consistent with FTIR and T-jump/Raman spectroscopy results by Hiyoshi et al.69 and Roos et al.70. While the ReaxFF model predicts similar product types, it underestimates CO2 and H2O due to the formation of intermediates like HNO2, HNO, HNO3, and C2H2O2.

For the cyclic HEM RDX, the EMFF-2025 model predicts major decomposition products as N2 (32.7%), H2O (29.8%), CO2 (19.7%), CHNO (4.3%), and H2 (3.2%), closely matching experimental results by Ornellas et al.71 (N2: 37%, H2O: 31%, CO2: 18%) and findings by Khichar et al.72 and Gongwer et al.73, which identified H2O, N2, CO2, CHNO, NO2, and NO. For DTTO, a cyclic HEM without H atoms, the EMFF-2025 model predicts N2 (46.8%), N2O (18.9%), CO2 (16.8%), and NO (8.8%), while ReaxFF method converts more N2O to N2, leading to an underestimation of N2O formation. These results align with DFT-MD simulations by Ye et al.74, which observed DTTO decomposing into two N2O molecules and iso-DTTO forming a dimer before releasing N2. This consistency highlights the reliability of the EMFF-2025 model in precisely predicting cyclic HEM decomposition.

In the thermal decomposition of CL-20, the EMFF-2025 model predicts major products as N2 (43.3%), CO2 (30.5%), H2O (14.4%), and CHO2 (3.7%), matching well with Naik et al.75 confirmed the presence of N2, CO2, N2O, and NO among the decomposition products using thermal decomposition GC/MS studies. Additionally, Isayev et al.76 noted significant differences in their AIMD simulations of CL-20 compared to ReaxFF simulations, particularly in the concentrations and reaction rates of H2O, CO, and CO2, which is also confirmed in our work. For TEX, the EMFF-2025 model predicts CO2 (48.7%), H2O (17.1%), N2 (11.5%), CHO2 (7.8%), and CHNO (6.7%), consistent with AIMD simulations by Dong et al.77 and in-situ infrared spectroscopy results by Zuo et al.78. In contrast, the ReaxFF model underestimates CO2 for both CL-20 and TEX, likely due to the presence of long-chain C–N heterocycles (C2–C15) in ReaxFF simulations, which hinder full decomposition of TEX.

From above analysis, the EMFF-2025 model demonstrates strong consistency with DFT results in describing structural, mechanical, and decomposition properties and also provides semi-quantitative predictions that align with experimental observations. This approach bridges the gap between computational efficiency and accuracy by overcoming the limitations of experimental data and reducing the computational complexity typical of traditional electronic structure methods. It effectively narrows the gap between the efficiency of classical force fields and the accuracy of DFT methods, establishing a more practical and reliable framework for simulating HEM behavior.

Chemical space and correlation heatmaps of HEMs

Building upon the validation of the EMFF-2025 model, the intrinsic relationship between the 20 HEMs was explored based on their sampled chemical space. PCA was applied using the Sklearn library, reducing the high-dimensional data of components with C, H, N, and O elements to a low-dimensional visualization. This transformation reflects the inherent similarities within the original dataset. The atomic local environment descriptor was generated using the smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP) method, with a cutoff radius of 5.0 Å, Gaussian width σ = 0.5 Å, maximum radial basis function order nmax = 8, and maximum angular momentum quantum number lmax = 8. These parameters were adapted from previous literature79,80. The classification of HEMs was based on the features of their atomic environments. Figure 7 shows the PCA results during training process, where each point represents a configuration from the training set, colored by the 20 HEMs. Data density is indicated by the point color, and 600 configurations are randomly selected from each HEM dataset for plotting.

The results in Fig. 7 show that PCA visualization effectively classifies substances in chemical space and reveals the formation of HEMs chemical space. As shown in Fig. 7, distinct clustering tendencies are exhibited by RDX, HMX, and CL-20 in low-dimensional space, which can be attributed to the consistency of their thermal decomposition processes52,81. In contrast, HEMs with significant structural differences, such as TNT, ADN, and FOX-7, display distinct spatial distribution patterns when introduced into the pre-trained model, thus outlining the fundamental chemical space of HEMs. The first six representative HEMs (RDX, HMX, CL-20, TNT, ADN, and FOX-7) largely define the boundaries of the chemical space. As more HEMs are included, their distributions in the SOAP feature space remain primarily within the principal component regions established by the initial set, indicating a high degree of structural similarity and considerable overlap between clusters. Consequently, the overall chemical space does not expand significantly. The PCA results illustrate that the constructed chemical space and its clustering patterns effectively capture the decomposition behaviors and relationships of different HEMs at various temperatures. This confirms the accuracy of the EMFF-2025 model in characterizing the thermal decomposition features of HEMs, ensuring its reliability and ability to generalize for known and structurally similar HEMs.

Figures S15, S16, and S17 present the PCA results for 20 HEMs at 300 K, 1500 K, and 3000 K, representing the unreactive, initial decomposition, and full decomposition stages, respectively. At 300 K, HEMs remain solid, with obvious separation in chemical space due to differences in crystal structures, making their chemical space hard to characterize. At 1500 K, HEMs enter the initial decomposition stage, partially decomposing into intermediate and small molecular gas products, leading to the preliminary formation of chemical space, with a reduction in the separation of the substances spatial distributions. At 3000 K, HEMs fully decompose and enter the oxidation stage, where their spatial distributions show a high degree of similarity, and chemical space rapidly forms. However, higher structural feature similarity may cause similar aggregation trends for different HEMs, making it challenging to distinguish specific distribution patterns of their decomposition products. To better characterize the chemical space, further classification analysis was performed, as shown in Fig. 8. In addition, Fig. S14 presents PCA visualizations of the spatial distributions of C, H, N, and O elements for 20 HEMs during the training of the EMFF-2025 model. The results indicate that these key elements are evenly and comprehensively distributed throughout the chemical space of HEMs, ensuring sufficient sampling and coverage. This elemental-level diversity strengthens the reliability and generalizability of the training dataset, providing a robust foundation for the predictive capabilities of EMFF-2025 model.

Based on structural and functional group differences, HEMs can be categorized into four types in chemical space: C–N cyclic (RDX, HMX, CL-20, NTO, and DTTO), phenyl rings (TNT, DNBF, HNS, TNB, and TATB), chain-like (NG, BTTN, PETN, and FOX-7), and ionic (TAGN, TKX-50, and ADN) structures. PCA analysis reveals distinct clustering patterns of these compounds in high-dimensional space.

In Figs. 8 and S15–S17, for C-N cyclic HEMs, RDX, HMX, and CL-20 exhibit strong clustering in both low-temperature solid phase and high-temperature decomposition products. This can be attributed to the fact that these HEMs decompose into common species, with 80% of their decomposition products being H2O, CO2, and N2, indicating highly similar decomposition pathways52,81. Moreover, DTTO and NTO show a similar distribution of chemical space density centers to the moderate-temperature regions of RDX, HMX, and CL-20 (Figs. S16, S17), suggesting that these C–N cyclic HEMs share similar decomposition mechanisms during thermal decomposition. For phenyl ring-based HEMs, their density centers at low temperatures are closely positioned, and there is significant overlap in the chemical space, indicating high similarity in both structure and decomposition behavior. In chain-like HEMs, PETN, NG, and BTTN contain multiple NO2 groups (≥3), resulting in more distinct clustering features, with their density centers concentrated in similar regions of chemical space. In contrast, FOX-7, having fewer NO2 groups, shifts its density center to the moderate-temperature region of chain-like HEMs (Figs. S16, S17), indicating that its decomposition products tend to converge at higher temperatures. For ionic HEMs, TAGN, and TKX-50 cluster with overlapping density centers, while ADN, without C elements, has a distinct separation in the low-temperature region (Fig. S15), but overlaps with the other two HEMs at high temperatures, as their main decomposition products are H2O and N2.

PCA analysis reveals significant overlap in clustering patterns of four types of HEMs in high-dimensional space: C–N ring (e.g., RDX, HMX, CL-20), phenyl rings (e.g., TNT, HNS, TNB, TATB, DNBF), chain-like (e.g., NG, PETN), and ionic (e.g., TAGN, TKX-50) structures. To further quantify intrinsic correlations of these HEMs, correlation heatmaps were generated using Euclidean distances in high-dimensional chemical space in Fig. 9.

Heatmaps of the 20 HEMs in the training set at 300 K (a) and 3000 K (b), based on Euclidean distance and normalized to characterize structural similarities. The values in the cells represent the similarity between compounds, with colors indicating the correlation values. High values (blue) indicate strong similarity, while low values (red) indicate weak similarity.

Figure 9 shows the correlation heatmaps for 20 HEMs at 300 and 3000 K. The correlation values, normalized using Euclidean distance from −1.00 to 1.00, assess structural similarity. Figure 9a, b illustrate the molecular structure similarity at 300 K and 3000 K, respectively. Heatmaps for all temperatures (300–3000 K) and for 1500 K (initial decomposition stage) are shown in Figs. S18, S19. The average structural similarity at 300 K is −0.04, while it increases to 0.12 at 3000 K. This unexpected phenomenon points out a fundamental fact regarding HEM decomposition; decomposition products exhibit a higher structural similarity despite their initial crystal structures. To reveal the physical insights, all 20 HEMs are classified into three categories based on the correlation distribution in Table 1.

-

(i)

High similarity under both low- and high-temperature conditions (group 1 in Table 1). In group 1, HEMs display a high degree of consistency in both initial structures at low temperatures and decomposition products at high temperatures. For instance, RDX and HMX maintain a high similarity value (0.98) from 300 to 3000 K. This high similarity is mainly due to both HEMs containing a C–N ring and NO2 groups and having similar crystal densities (1.89 g/cm3 vs. 1.96 g/cm3). Their major decomposition products, including N2 (32.7% vs. 33.1%), H2O (29.8% vs. 29.9%), and CO2 (19.7% vs. 20.9%), also show high consistency in both distribution and proportions, inferring similar decomposition pathways (Figs. 6, S13). Despite their initially complex molecular structures, the decomposition processes can be effectively described using a limited number of molecular fragments, providing a concise and efficient approach to understanding intricate decomposition mechanisms. This observation is consistent with the fragmentation treatment of HEMs proposed in our recently developed EM-HyChem model81, a reaction kinetics framework based on hybrid chemical methods. Similarly, NG and PETN are chain-like HEMs containing CH2O and NO2 groups, with similarity values of 1.00 and 0.98 at low and high temperatures, respectively. TNT, DNBF, TNB, and HNS share similar structures based on phenyl rings and NO2 groups, with average similarity values of 0.86 and 0.95 at low and high temperatures, respectively. This indicates that these structurally similar HEMs exhibit comparable decomposition pathways during thermal decomposition, and their decomposition mechanisms can also be described by similar fragmentation patterns.

-

(ii)

Low similarity at low temperature, and high similarity at high temperature (group 2 in Table 1). These HEMs have significant differences in molecular structure but produce similar decomposition products at high temperatures. For example, ADN and TAGN, both ionic HEMs, show an increase in their average similarity value from −0.11 at low temperatures to 0.79 at high temperatures, with a red-to-blue shift from 300 to 3000 K. This change is mainly due to their differing initial structures: ADN contains an NH4+ group and lacks C elements, while TAGN consists of NH3OH+ and NO3−. At high temperatures, their primary decomposition products, H2O (37.4% vs. 43.1%) and N2 (30.1% vs. 40.8%), show similar distribution patterns, indicating similar decomposition pathways. Additionally, it has been observed that RDX and HMX, which have similar structures, exhibit significant differences at low temperatures compared to FOX-7, NG, PETN, DTTO, and NTO. However, at high temperatures, the similarity in their decomposition products increases significantly, ranging from −0.25 to 0.90 and from −0.17 to 0.81, respectively. This suggests that, despite large structural differences at low temperatures, the chemical behavior of some HEMs tends to align at high temperatures, with their high-temperature decomposition reactions likely following similar fragmentation pathways.

-

(iii)

High similarity at low temperature, and low similarity at high temperature (group 3 in Table 1). These HEMs exhibit an anomalous behavior, possessing similar molecular structures and functional groups as crystals. However, their high-temperature decomposition products show significant variation in composition and proportion. For example, the average similarity value of TATB and BTF decreases from 0.84 to 0.24 as the temperature rises, with the correlation heatmap shifting from blue to red between 300 and 3000 K. This change is mainly due to both compounds containing phenyl rings and NO2 groups in their initial structures, but during thermal decomposition, TATB produces CO2 (31.2%), H2O (25.1%), and N2 (19.0%), while BTF, lacking H elements, primarily produces CO2 (44.2%), N2 (38.5%), and NO (8.5%). Meanwhile, CL-20 and TEX exhibit a similar chemical environment to NC and BTTN at low temperatures due to the presence of the same CH2N and NO2 groups. However, due to differences in their structures and reaction pathways, their high-temperature decomposition products differ significantly, with their similarity values decreasing from 0.92 to 0.31 and from 0.84 to −0.01, respectively. This indicates that, despite having similar initial structures at low temperatures, the high-temperature decomposition mechanisms and product similarities of these HEMs are significantly influenced by differences in their structural units, making it difficult to determine their decomposition mechanisms through similar fragmentation patterns. Furthermore, the structural similarities of different types of HEMs were compared, providing a basis for the exploration of the impact of different structural units on the decomposition mechanisms and product distribution of HEMs, detailed results can be found in Fig. S20.

Through PCA clustering and correlation analysis based on the EMFF-2025 model, this work elucidates the chemical space characteristics and interrelations of HEMs composed of C, H, N, and O elements. EMFF-2025 model effectively extracts key descriptors of HEMs, providing a theoretical foundation for molecular design from first-principles calculations. It improves the description of complex chemical systems and serves as a key tool for exploring chemical space and molecular interactions. Additionally, EMFF-2025 fills the research gap on HEM correlations and provides a foundation for studying HEM structure-property relationships. Moving forward, integrating the EMFF-2025 model with the EM-HyChem reaction kinetics methodology will further refine microstructural decomposition kinetic modeling and ultimately support molecular engineering design and safety assessment of HEMs.

Discussion

This work successfully develops a precise and efficient EMFF-2025 model for HEMs with C, H, N, and O elements. Based on our previous pre-trained model (DP-CHNO-2024), this innovative approach combines a deep learning framework with the transfer learning method. By incorporating a small amount of new training data, the generalization ability and predictive accuracy of the model are significantly enhanced while reducing computational costs. The performance of the EMFF-2025 model was evaluated using a DFT database, showing that prediction errors for atomic energies and forces across a wide temperature range (300–4000 K) were below 65.2 meV/atom and 0.684 eV/Å, respectively. For mechanical properties, the predictions of the model for cell parameters and equations of state were highly consistent with DFT results and outperformed the ReaxFF force field. In thermal decomposition, MD simulations for 20 HEMs showed that the EMFF-2025 model accurately predicted the distribution of major decomposition products under heating conditions, aligning well with experimental data. The model also effectively reveals the clustering trends and structural similarities of HEMs identified by PCA analysis. These results confirm the capability of the EMFF-2025 model to precisely describe atomic-scale crystal structures, mechanical behavior, and decomposition mechanisms in both finite and extended systems. Crucially, the EMFF-2025 model effectively captures the chemical space of HEMs, identifying key atomic interactions and reaction pathways during thermal decomposition. By providing a detailed representation of chemical space, this model enhances our understanding of HEM reactivity under various conditions, enabling predictive insights into their behavior in diverse environments. This pioneering work lays the foundation for accelerating the development and application of HEMs, supporting future modeling efforts to explore their complex microstructures and macroscopic properties with high accuracy.

Methods

Data set preparation

A total of 20 HEMs with C, H, N, and O elements are considered in the EMFF-2025 model. In Fig. 1, these HEMs were categorized based on their configurations into cyclic-like structures (RDX, HMX, TNT, DNBF, BTF, TATB, DTTO, NTO, TNB, HNS, and NC), cage-like structures (CL-20 and TEX), ionic structures (ADN, TKX-50, and TAGN), and chain-like structures (FOX-7, NG, PETN, and BTTN), with detailed abbreviations listed in Table S1. Since dataset quality and size directly impact NNP model performance, we ensured comprehensive PES coverage to meet training and testing requirements. Two strategies, i.e., AIMD calculations and transfer learning strategies were employed to generate the dataset for these HEMs.

The foundational DFT dataset is derived from our previous work52, where AIMD simulations were performed on RDX, HMX, and CL-20 over a temperature range of 300–4000 K using the CP2K package82 at the PBE-D3/DZVP-MOLOPT level. Each HEM was simulated at temperatures of 300, 1000, 2000, 3000, and 4000 K, with a simulation time of 2 ps per temperature. This resulted in the collection of 5000 energy and force data snapshots for each HEM, totaling 15,000 structures. Additionally, through the DP-GEN process, 12,000 data points were obtained for RDX, HMX, and CL-20. The AIMD simulations and DP-GEN processes in this foundational DFT dataset span the 300–4000 K temperature range and include sampling data with scaling factors ranging from 0.92 to 1.08. For specific computational details, more information was given in our previous works52,53,83,84,85.

Besides the foundational DFT dataset, the DP-GEN process60 from the DeePMD-kit package86 was used to generate new configurations during the transfer learning process (Fig. 1). In the transfer learning process, four NNPs were obtained by training with different initialization seeds, and each iteration involves 500,000 training steps. One of these NNPs was used to perform four MD simulations over the temperature range of 300 to 4000 K. The other three NNPs were used to evaluate the MD trajectories and obtain deviations in atomic forces, serving as bounds for identifying new configurations. For the number of sample configurations for each HEM material, a dynamic sampling strategy based on model error feedback was employed. Specifically, the transferability of the current iterative model to the next material was first evaluated. If higher errors or biases were observed in the validation set, or if the errors were concentrated in certain temperature ranges, the sampling density in those regions was increased. At the same time, all configuration samples were taken within the predefined temperature range (300–4000 K) at fixed intervals (i.e., 300, 1000, 2000, 3000, and 4000 K) to ensure uniform coverage of the training data and enhance the interpretability of the PES for the thermal decomposition process of HEMs. Configurations on the MD trajectories were recorded at time intervals of Δt = 0.02 ps. During the training process, 25% of the configurations were randomly selected as the test set. The validation set was randomly selected with ten configurations from each species, used to calculate the training loss for each training batch. To ensure an unbiased performance evaluation, the stopping criterion for the transfer learning process is based on the test set. The energy threshold is set at 0.5 eV/atom, and the force threshold is set at 1 eV/Å.

The explored configurations are classified into three categories based on atomic force error indicators: “accurate”, “candidate”, and “failed”. Accurate configurations matched well with the DFT results, while failed configurations had significant errors. Configurations between these extremes were labeled as candidates. In this work, the lower (εlo) and upper (εup) bounds of the force deviation were set at 0.05 eV/Å and 0.15 eV/Å, respectively. These screening bounds are derived from the test results of Zhang et al.60. Configurations with a relative force deviation of less than 0.05 eV/Å were marked as “accurate”, while those within the 0.05–0.15 eV/Å range were marked as “candidates” and included in the training set. The maximum model deviation in per frame was used to identify configurations requiring DFT calculations. The force error is defined as87.

where \({D}_{{f}_{{\rm{i}}}}\) is the absolute model deviation of the force on atom i, fi is the Norm of the force.

The DP-GEN process completed 45 iterations, generating 6900 configurations. Instead of costly DFT calculations for all structures, it used error indicators to identify and refine uncertain configurations, reducing computational costs while maintaining accuracy. Unlike traditional methods relying on large DFT datasets, DP-GEN employs an iterative transfer learning approach, selectively optimizing training data. NVT simulations across 300–4000 K ensured comprehensive sampling of key atomic interactions, effectively capturing the PES of HEMs.

Training of EMFF-2025 model

Figure 1 shows the training process of the EMFF-2025 model developed using the DP scheme. Similar to our previous works52,55,83,84, the NNP model training process used physical parameters as atomic coordinates (R), energy (E), and force (F) as inputs for deep neural network training. The DP model represents the total potential energy (E) of the system as the sum of atomic energies (Ei). Here, each atomic energy (Ei) is parameterized using the NNP model, defined as,

where, ri is the local environment of atom i relative to its neighboring atoms within the cutoff radius in Cartesian coordinates, αi is the chemical species of atom i, and ωαi denotes the optimized set of NNP parameters during the training process. Each subnetwork of Ei consists of an embedded neural network and a fitting neural network. Both networks use the ResNet architecture. The embedding network is sized (25, 50, and 100), with an embedding matrix size of 12. The fitting network is sized (240, 240, and 240). The atomic cutoff radius is set to 6.0 Å, and the descriptor decays smoothly from 0.5 to 6.0 Å. The initial learning rate is set to 0.001 with a decay rate of 0.98, decaying every 4000 steps. The training process iteratively adjusts the model parameters to minimize the loss function (L), which measures the difference between the neural network prediction and the reference data. The loss function is defined as the sum of the squared differences of the NNP predictions,

where, pe and pf represent the weights of the energy and force terms, respectively. During model training, the loss function weights were set as pe = 0.02 and pf = 1000, in accordance with official recommendations from the DeePMD framework87,88 (https://github.com/deepmodeling/dpgen/wiki) and prior studies on similar systems36,59,60,86,89,90,91. N represents the number of atoms in the structure. The DP scheme trains the model by computing gradients of the loss function using backpropagation. The final NNP model is trained for 4.0 × 106 iterations, with the learning rate following an exponential decay. The entire computational process used an NVIDIA V100 GPU with 8 CPU cores.

Validation and testing workflow

The crystal cell parameters and EOS tests for all investigated HEMs were evaluated using DFT, EMFF-2025, and ReaxFF methods. The initial configurations for all crystalline structures were obtained from the CCDC database62. However, BTTN, which is a liquid at room temperature, was constructed using Packmol92 with an initial density of 1.119 g cm−3 and was further refined through geometry and cell optimization to obtain a reasonable configuration. In the DFT calculations, core electrons were treated with the Goedecker-Teter-Hutter Gaussian-type pseudopotential using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation methods93,94. Dispersion interactions were accounted for using Grimme’s DFT-D3 method95, with energy cutoffs set to 60 Ry for wave functions and 400 Ry for electron density. Polarized orbitals were included alongside double-ζ Gaussian basis functions (DZVP-MOLOPT). SCF self-consistent field calculations were converged to an accuracy of 1.0 × 10−6. Additionally, the ReaxFF model was adapted from Liu et al.27 as a reference. Both NNP and ReaxFF methods were implemented in the LAMMPS package96, with the vmax parameter set to allow maximum cell size changes of 0.001 Å per relaxation step. Convergence criteria for minimization were set at 1.0 × 10−7 for energy and 1.0 × 10−15 for forces.

To assess the performance of the EMFF-2025 model in the thermal decomposition of HEMs, MD simulations were conducted using the LAMMPS package96. Initially, due to varying molecular weights, HEMs were extended via supercell operations to ensure that each thermal decomposition case contained more than 32 HEM molecules (>1500 atoms). The MD simulations of these HEMs were divided into relaxation and thermal decomposition steps. Both steps were executed using the NVT ensemble with a time step of 0.2 fs, and temperature control was maintained using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat97. Motion equations were integrated using the Velocity Verlet method, with periodic boundary conditions applied. The relaxation simulation was performed at 10 ps, maintaining a temperature of 300 K. During the thermal decomposition simulations of HEMs, temperatures ranged from 300 to 3000 K under heating conditions of 27 K/ps, using the final snapshots from the relaxation process as the initial state for the decomposition simulations. To ensure statistical significance of the results, all simulations were independently performed three times with different random seeds under the same conditions, and the simulation time was set to 100 ps. Finally, chemical species were analyzed from MD trajectories using ReacNetGenerator98, and quantities of all products were averaged across the three simulations to mitigate numerical errors.

Data availability

The EMFF-2025 model is available in the GitHub repository: https://github.com/MingjieWen/General-NNP-model-for-C-H-N-O-Energetic-Materials. It is also available in the Gitee repository: https://gitee.com/wen-mingjie18/General-NNP-model-for-C-H-N-O-Energetic-Materials111.

Code availability

The code for training the EMFF-2025 model, including the figures and detailed instructions, is available at: https://github.com/MingjieWen/General-NNP-model-for-C-H-N-O-Energetic-Materials.

References

Agrawal, J. P. High energy materials: propellants, explosives and pyrotechnics (John Wiley & Sons, 2010).

Wang, Y. et al. Accelerating the discovery of insensitive high-energy-density materials by a materials genome approach. Nat. Commun. 9, 2444 (2018).

Klapötke, T. M. Chemistry of high-energy materials (Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2022).

Zhang, W. et al. A promising high-energy-density material. Nat. Commun. 8, 181 (2017).

Badgujar, D. M., Talawar, M. B., Asthana, S. N. & Mahulikar, P. P. Advances in science and technology of modern energetic materials: an overview. J. Hazard Mater. 151, 289–305 (2008).

Agrawal, J. P. & Dodke, V. S. Some novel high energy materials for improved performance. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 647, 1856–1882 (2021).

Tsyshevsky, R., Pagoria, P., Smirnov, A. S. & Kuklja, M. M. Comprehensive end-to-end design of novel high energy density materials: II. Computational modeling and predictions. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 23865–23874 (2017).

Qian, X., Yoon, B.-J., Arróyave, R., Qian, X. & Dougherty, E. R. Knowledge-driven learning, optimization, and experimental design under uncertainty for materials discovery. Patterns 4, 100863 (2023).

Dehghannasiri, R. et al. Optimal experimental design for materials discovery. Comp. Mater. Sci. 129, 311–322 (2017).

Kokol, P. Data-Mining and Knowledge Discovery, Introduction to. Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science (ed Meyers R. A.) (Springer, 2009).

Muravyev, N. V., Fershtat, L. & Zhang, Q. Synthesis, design and development of energetic materials: Quo Vadis? Chem. Eng. J. 486, 150410 (2024).

Meng, L., Song, Q., Yao, C., Zhang, L. & Pang, S. Chemical reaction mechanisms and models of energetic materials: a perspective. EMF 6, 129–144 (2024).

Pilania, G. Machine learning in materials science: from explainable predictions to autonomous design. Comput. Mater. Sci. 193, 110360 (2021).

Louie, S. G., Chan, Y.-H., da Jornada, F. H., Li, Z. & Qiu, D. Y. Discovering and understanding materials through computation. Nat. Mater. 20, 728–735 (2021).

Pyzer-Knapp, E. O. et al. Accelerating materials discovery using artificial intelligence, high performance computing and robotics. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 84 (2022).

Prašnikar, E., Ljubič, M., Perdih, A. & Borišek, J. Machine learning heralding a new development phase in molecular dynamics simulations. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 102 (2024).

Chmiela, S. et al. Accurate global machine learning force fields for molecules with hundreds of atoms. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf0873 (2023).

Unke, O. T. et al. Machine learning force fields. Chem. Rev. 121, 10142–10186 (2021).

Mo, P. et al. Accurate and efficient molecular dynamics based on machine learning and non von Neumann architecture. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 107 (2022).

Andersson, D. A. & Beeler, B. W. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations of NaCl, UCl3 and NaCl-UCl3 molten salts. J. Nucl. Mater. 568, 153836 (2022).

Mao, Q. et al. Classical and reactive molecular dynamics: principles and applications in combustion and energy systems. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 97, 101084 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Thermal decomposition mechanism of 2,2′,4,4′,6,6′-Hexanitrostilbene by ReaxFF reactive molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 19309–19318 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. Effects of temperature and wax binder on thermal conductivity of RDX: a molecular dynamics study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 179, 109698 (2020).

Han, S., van Duin, A. C. T., Goddard, W. A. III & Strachan, A. Thermal decomposition of condensed-phase nitromethane from molecular dynamics from ReaxFF reactive dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 6534–6540 (2011).

Senftle, T. P. et al. The ReaxFF reactive force-field: development, applications and future directions. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 1–14 (2016).

van Duin, A. C. T., Dasgupta, S., Lorant, F. & Goddard, W. A. ReaxFF: a reactive force field for hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 9396–9409 (2001).

Liu, L., Liu, Y., Zybin, S. V., Sun, H. & Goddard, W. A. III ReaxFF-lg: correction of the ReaxFF reactive force field for London dispersion, with applications to the equations of state for energetic materials. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 11016–11022 (2011).

Islam, M. M. & Strachan, A. Reactive molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the shock response of liquid nitromethane. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 2613–2626 (2019).

Bertels, L. W., Newcomb, L. B., Alaghemandi, M., Green, J. R. & Head-Gordon, M. Benchmarking the performance of the ReaxFF reactive force field on hydrogen combustion systems. J. Phys. Chem. A 124, 5631–5645 (2020).

Gao, C. et al. Innovative materials science via machine learning. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2108044 (2022).

Chmiela, S. et al. Machine learning of accurate energy-conserving molecular force fields. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603015 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhancing geometric representations for molecules with equivariant vector-scalar interactive message passing. Nat. Commun. 15, 313. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43720-2 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhancing geometric representations for molecules with equivariant vector-scalar interactive message passing. Nat. Commun. 15, 313 (2024).

Liao, Y.-L. & Smidt, T. Equiformer: equivariant graph attention transformer for 3d atomistic graphs. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.11990 (2022).

Gao, Z. et al. ISNet: decomposed dynamic spatio-temporal neural network for ionospheric scintillation forecasts. Space Weather 23, e2024SW004239 (2025).

Wen, T., Zhang, L., Wang, H., E, W. & Srolovitz, D. J. Deep potentials for materials science. Mater. Futures 1, 022601 (2022).

Zhang, L., Han, J., Wang, H., Car, R. & E, W. Deep potential molecular dynamics: a scalable model with the accuracy of quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 143001 (2018).

Balyakin, I., Rempel, S., Ryltsev, R. & Rempel, A. Deep machine learning interatomic potential for liquid silica. Phys. Rev. E 102, 052125 (2020).

Achar, S. K., Zhang, L. & Johnson, J. K. Efficiently trained deep learning potential for graphane. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 14874–14882 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. A deep learning interatomic potential developed for atomistic simulation of carbon materials. Carbon 186, 1–8 (2022).

Yang, W. et al. Exploring the effects of ionic defects on the stability of CsPbI3 with a deep learning potential. ChemPhysChem 23, e202100841 (2022).

Reiser, P. et al. Graph neural networks for materials science and chemistry. Commun. Mater. 3, 93 (2022).

Zeng, J., Giese, T. J., Zhang, D., Wang, H. & York, D. M. DeePMD-GNN: a DeePMD-kit plugin for external graph neural network potentials. J. Chem. Inf. Model 65, 3154–3160 (2025).

Li, Z. & Scandolo, S. Deep-learning interatomic potential for iron at extreme conditions. Phys. Rev. B 109, 184108 (2024).

Sanchez-Burgos, I., Muniz, M. C., Espinosa, J. R. & Panagiotopoulos, A. Z. A deep potential model for liquid–vapor equilibrium and cavitation rates of water. J. Chem. Phys. 158, 184504 (2023).

Zeng, J., Cao, L., Xu, M., Zhu, T. & Zhang, J. Z. H. Complex reaction processes in combustion unraveled by neural network-based molecular dynamics simulation. Nat. Commun. 11, 5713 (2020).

Zhang, J., Guo, W. & Yao, Y. Deep potential molecular dynamics study of Chapman-Jouguet detonation events of energetic materials. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 7141–7148 (2023).

Chu, Q., Fu, X., Zhen, X., Liu, J. & Chen, D. Molecular simulations of HTPB/Al/AP/RDX propellants combustion. Chin. J. Explos. Propellants 47, 254–261 (2024).

Hamilton, B. W., Yoo, P., Sakano, M. N., Islam, M. M. & Strachan, A. High-pressure and temperature neural network reactive force field for energetic materials. J. Chem. Phys. 158, 144117 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Exploring the frontiers of condensed-phase chemistry with a general reactive machine learning potential. Nat. Chem. 16, 727–734 (2024).

Yoo, P. et al. Neural network reactive force field for C, H, N, and O systems. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 9 (2021).

Wen, M., Chang, X., Xu, Y., Chen, D. & Chu, Q. Determining the mechanical and decomposition properties of high energetic materials (α-RDX, β-HMX, and ε-CL-20) using a neural network potential. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26, 9984–9997 (2024).

Chu, Q., Chang, X., Ma, K., Fu, X. & Chen, D. Revealing the thermal decomposition mechanism of RDX crystals by a neural network potential. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 25885–25894 (2022).

Chang, X., Wu, Y., Chu, Q., Zhang, G. & Chen, D. Ab initio driven exploration on the thermal properties of Al-Li alloy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 14954–14964 (2024).

Chang, X., Chu, Q. & Chen, D. Monitoring the melting behavior of boron nanoparticles using a neural network potential. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 12841–12853 (2023).

Jiang, T., Gradus, J. L. & Rosellini, A. J. Supervised machine learning: a brief primer. Behav. Ther. 51, 675–687 (2020).

Zhou, L., Pan, S., Wang, J. & Vasilakos, A. V. Machine learning on big data: opportunities and challenges. Neurocomputing 237, 350–361 (2017).

Zhang, D. et al. Pretraining of attention-based deep learning potential model for molecular simulation. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 94 (2024).

Wang, Y., Zhang, L., Xu, B., Wang, X. & Wang, H. A generalizable machine learning potential of Ag–Au nanoalloys and its application to surface reconstruction, segregation and diffusion. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 30, 025003 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. DP-GEN: a concurrent learning platform for the generation of reliable deep learning based potential energy models. Comput. Phys. Commun. 253, 107206 (2020).

Zhang, D. et al. DPA-2: a large atomic model as a multi-task learner. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 293 (2024).

Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/).

Izato, Y. -i, Koshi, M., Miyake, A. & Habu, H. Kinetics analysis of thermal decomposition of ammonium dinitramide (ADN). J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 127, 255–264 (2017).

Kubota, N., Hirata, N. & Sakamoto, S. Combustion mechanism of TAGN. Symp. Int. Combust. 21, 1925–1931 (1988).

Naidu, S. R., Prabhakaran, K. V., Bhide, N. M. & Kurian, E. M. Thermal and spectroscopic studies on the decomposition of some aminoguanidine nitrates. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 61, 861–871 (2000).

Liu, Y., Li, F. & Sun, H. Thermal decomposition of FOX-7 studied by ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. Theor. Chem. Acc. 133, 1567 (2014).

Jiang, L. et al. Study of the thermal decomposition mechanism of FOX-7 by molecular dynamics simulation and online photoionization mass spectrometry. RSC Adv. 10, 21147–21157 (2020).

Booth, R. S. & Butler, L. J. Thermal decomposition pathways for 1,1-diamino-2,2-dinitroethene (FOX-7). J. Chem. Phys. 141, 134315 (2014).

Hiyoshi, R. I. & Brill, T. B. Thermal decomposition of energetic materials 83. Comparison of the pyrolysis of energetic materials in air versus argon. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 27, 23–30 (2002).

Roos, B. D. & Brill, T. B. Thermal decomposition of energetic materials 82. Correlations of gaseous products with the composition of aliphatic nitrate esters. Combust. Flame 128, 181–190 (2002).

Ornellas, D. L. Calorimetric determination of the heat and products of detonation of an Unusual CHNOFS Explosive. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 14, 122–123 (1989).

Khichar, M., Patidar, L. & Thynell, S. Comparative analysis of vaporization and thermal decomposition of cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine (RDX). J. Propuls. Power 35, 1098–1107 (2019).

Gongwer, P. E. & Brill, T. B. Thermal decomposition of energetic materials 73: the identity and temperature dependence of “minor” products from flash-heated RDX. Combust. Flame 115, 417–423 (1998).

Ye, C. et al. Initial decomposition reaction of di-tetrazine-tetroxide (DTTO) from quantum molecular dynamics: implications for a promising energetic material. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 1972–1978 (2015).

Naik, N. H., Gore, G. M., Gandhe, B. R. & Sikder, A. K. Studies on thermal decomposition mechanism of CL-20 by pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS). J. Hazard Mater. 159, 630–635 (2008).

Isayev, O., Gorb, L., Qasim, M. & Leszczynski, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics study on the initial chemical events in nitramines: thermal decomposition of CL-20. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 11005–11013 (2008).

Xiang, D. & Zhu, W. Thermal decomposition of isolated and crystal 4,10-dinitro-2,6,8,12-tetraoxa-4,10-diazaisowurtzitane according to ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. RSC Adv. 7, 8347–8356 (2017).

Zuo, Y. et al. Characteristics of thermal decomposition of TEX. Chin. J. Energ. Mater. 14, 385–387 (2006).

Bartók, A. P., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. On representing chemical environments. Phys. Rev. B 87, 184115 (2013).

De, S., Bartók, A. P., Csányi, G. & Ceriotti, M. Comparing molecules and solids across structural and alchemical space. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 13754–13769 (2016).

Chen, X. et al. EM-HyChem: bridging molecular simulations and chemical reaction neural network-enabled approach to modelling energetic material chemistry. Combust. Flame 275, 114065 (2025).

Hutter, J., Iannuzzi, M., Schiffmann, F. & VandeVondele, J. CP2K: atomistic simulations of condensed matter systems. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 4, 15–25 (2014).

Chu, Q., Wen, M., Fu, X., Eslami, A. & Chen, D. Reaction network of ammonium perchlorate (AP) decomposition: the missing piece from atomic simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 127, 12976–12982 (2023).

Chu, Q., Luo, K. H. & Chen, D. Exploring complex reaction networks using neural network-based molecular dynamics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 4052–4057 (2022).

Wen, M. et al. Predicting the catalytic mechanisms of CuO/PbO on energetic materials using machine learning interatomic potentials. Chem. Eng. Sci. 309, 121494 (2025).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Han, J. & E, W. DeePMD-kit: a deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Zeng, J. et al. DeePMD-kit v2: a software package for deep potential models. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 054801 (2023).

Liang, W., Zeng, J., York, D. M., Zhang, L. & Wang, H. Learning DeePMD-Kit: a guide to building deep potential models. in A Practical Guide to Recent Advances in Multiscale Modeling and Simulation of Biomolecules (eds Wang, Y. & Zhou, R.) (AIP Publishing LLC, 2025).

Jiang, J., Yu, Y., Mei, Z., Yi, Z.-X. & Ju, X.-H. Thermal decomposition and shock response mechanism of DNTF: deep potential molecular dynamics simulations. Energy 313, 133799 (2024).

Zhang, J., Guo, W. & Yao, Y. Deep potential molecular dynamics study of Chapman–Jouguet detonation events of energetic materials. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 7141–7148 (2023).

Zhang, L., Han, J., Wang, H., Saidi, W. & Car, R. End-to-end symmetry preserving inter-atomic potential energy model for finite and extended systems. In Proc 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing System. 31, 4436–4446 (Curran Associates Inc., 2018).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1703 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Evans, D. J. & Holian, B. L. The Nose-Hoover thermostat. J. Chem. Phys. 83, 4069–4074 (1985).

Zeng, J. et al. ReacNetGenerator: an automatic reaction network generator for reactive molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 683–691 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 52106130) and the State Key Laboratory of Explosion Science and Safety Protection (Grants QNKT23-15).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W. and J.H. developed the neural network potential and wrote the main manuscript text. W.L. and X.C. performed data curation and formal analysis. Q.C. contributed to methodology design, visualization, and funding acquisition. D.C. supervised the project and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, M., Han, J., Li, W. et al. EMFF-2025: a general neural network potential for energetic materials with C, H, N, and O elements. npj Comput Mater 11, 333 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01809-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01809-w

This article is cited by

-

Sol–gel-derived hydroxyapatite/Co3O4 hybrid nanostructures as advanced electrodes for energy storage

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2026)